Aurangzeb

| Abul Muzaffar Muhy-ud-Din Muhammad Aurangzeb Alamgir | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Reign | 31 July 1658 – 3 March 1707 (48 years, 215 days) | ||||

| Coronation | 15 June 1659 at Red Fort, Delhi | ||||

| Predecessor | Shah Jahan | ||||

| Successor | Bahadur Shah I | ||||

| Born | 4 November 1618 Dahod, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Died | 3 March 1707 (aged 88) Ahmednagar, India | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouses | Nawab Raj Bai Begum Dilras Bano Begam Hira Bai Zainabadi Mahal Aurangabadi Mahal Udaipuri Mahal | ||||

| Issue | Zeb-un-Nissa Zinat-un-Nissa Muhammad Azam Shah Mehr-un-Nissa Muhammad Akbar Sultan Muhammad Bahadur Shah I Badr-un-Nissa Zabdat-un-Nissa Muhammad Kam Baksh | ||||

| |||||

| House | Timurid | ||||

| Dynasty | Timurid | ||||

| Father | Shah Jahan | ||||

| Mother | Mumtaz Mahal | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

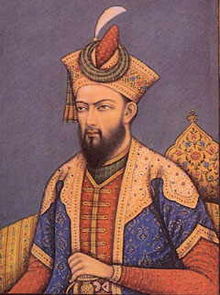

Abul Muzaffar Muhy-ud-Din Muhammad Aurangzeb Alamgir(Urdu: ابلمظفر- محىالدين - محمد اورنگزيب- عالمگیر),(Hindi: अबुल मुज़फ्फर मुहिउद्दीन मुहम्मद औरंगज़ेब आलमगीर) (4 November 1618 [O.S. 25 October] – 3 March 1707 [O.S. 20 February]), more commonly known as Aurangzeb (Hindi: औरंगज़ेब)[1] or by his chosen imperial title Alamgir (Hindi: आलमगीर) ("Conquerer of the World", Urdu: عالمگیر), was the sixth Mughal Emperor of India, whose reign lasted from 1658 until his death in 1707.[2][3]

Badshah Aurangzeb, having ruled most of the Indian subcontinent for nearly half a century, was the second longest reigning Mughal emperor after Akbar. In this period he tried hard to get a larger area, notably in southern India, under Mughal rule than ever before.[4] But after his death in 1707, the Mughal Empire gradually began to shrink. Major reasons include a weak chain of "Later Mughals", an inadequate focus on maintaining central administration leading to governors forming their own empires, a gradual depletion of the fortunes amassed by his predecessors and the growth of secessionist sentiments amongst the other communities of the empire like the Marathas.

Aurangzeb cherished the ambition of converting India into a land of Islam. For this, he encouraged forced religious conversions and destroyed thousands of Hindu temples during his reign.[5][6][7]

Rise to throne

Early life

Aurangzeb was born the third son and sixth child of Prince Khurram (later the fifth Mughal emperor Shah Jahan) and Mumtaz Mahal (Arjumand Bāno Begam) in Dahod on the way to Ujjain.[8] After an unsuccessful rebellion by his father, Aurangzeb and his brother Dara Shikoh were submitted as hostages in June,1626 under Nur Jahan at his grandfather Jahangir's court in Lahore.[8] After Shah Jahan was officially declared the Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh returned to live with their parents in Agra on 26 February 1628.[8] As Aurangzeb grew up his daily allowance was fixed to Rs.500, while he spent his allowance in religious education and the study of history, he accused his brothers of alcoholism and womanizing.[8]

On May 28, 1633 when Aurnagzeb was 15 years of age he narrowly escaped death in an elephant fight and successfully defended himself from a stampede. While his other brothers fled from the arena, Aurnagzeb's valor was well appreciated by his father the mughal Emperor Shah Jahan who gave him the title Bahadur (Hero) and had him weighed in Gold and presented him gifts worth Rs 2 lakhs. This heroic deed was celebrated in Persian and Urdu verses.[8]

If the (elephant) fight had ended fatally for me it would not have been a matter of shame. Death drops the curtain even on Emperors; it is no dishonor. The shame lay in what my brothers did![8]

— Aurangzeb to Shah Jahan taunting Dara Shikoh's cowardice , Ahkam-i-Alamgiri - Hamidullah Khan

He visited Kashmir with Shah Jahan and was presented with the parganah of Lukh-bhawan in September,1634.[8] On 13 December 1634 he was given his first command of 10000 horse, with an additional 4000 troopers.[8] He was allowed to use the Red tent, an imperial prerogative, indeed Shah Jahan had big plans for him particularly in the Mughal military.[8]

Education

Sadullah Khan (later wazir to Shah Jahan), Mir Muhammad Hashim of Gilan and Muhammad Saleh Kamboh were a few of his childhood teachers.[8] Aurangzeb had a keen mind and quickly learnt what he read. He mastered the Quran and the hadith and readily quoted from them.[8] He spoke and wrote Arabic and Persian like a scholar.[8] He also learnt Chagtai Turki when he served in Kandahar.[8]

He wrote Arabic with a vigorous naskh hand and used to copy the Quran in it.[8] Two richly bound and illuminated manuscripts of his exist in Mecca and Medina, with another copy preserved in Nizamuddeen Aoliya.[8]

Aurangzeb was a prolific writer of letters and commented on petitions in his own hand.[8] He frequently quoted Islamic verses but had no special taste for poetry.[8]

Following Sufism

Aurangzeb was a strict follower of Sufism and used to carry out his personal expenses by stitching caps which are still worn by Muslims while conducting their prayers, and by writing The Holy Quran.

Aurangzeb was a Sufi and followed the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi method of Sufism. He was a disciple of Khwaja Muhammad Masoom, the third son and successor of the founder of Mujaddidi order Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi. His letters to Shayk and the replies from him show that he was highly devoted to him and followed him in every matter of his life and rule.[11] Though the Shaykh was not involved in politics, Aurangzeb established Islamic law inspired and instructed by him.

Soon after coronation, he wrote to Shaykh that due to the duties of the empire, he was unable to attend his shaykh's company, therefore he should send one of his noble sons to the capital for spiritual and Islamic guidance to Aurangzeb. The shaykh sent his son, Khwaja Saif ad-Din Sirhindi (5th son) who was a scholar and Sufi shaykh by himself and only 27 years old. He not only guided Aurangzeb to observe the Islamic law properly, he was also the source of most of the Islamic rules Aurangzeb implemented in the empire. One of those is the ban on musical instruments throughout the country, which was initially suggested by Khwaja Saif ad-Din in accordance with the Sharia law.

Many other famous Sufis also revered Aurangzeb, including the highly venerated Sufi and famous poet of Punjab Sultan Bahu (ca 1628 - 1691), who wrote a book with spiritual secrets specially for him. The book was written in Persian and titled "Aurang-i-Shāhī", to resemble the name of the emperor. The author has praised the emperor with titles such as The Just King.[12]

Bundela War, 1635

To contain the Bundela rebellion led by the renegade Jhujhar Singh, the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan planned a campaign to strike the rebellious territory known as Bundelkhand and its capitol Orchha from 3 sides: Syed Khan-i-Jahan with 10,500 men from Badaun, Abdullah Khan Bahadur Firuz Jang with 6000 men from the north and Khan-i-Dauran with 6000 men from the south-west.[8] The three generals were of equal rank and hence to ensure unity and co-operation amongst them, Aurangzeb, then a 16 year old commander of 10,000, escorted by 1000 archers and 1000 horses, was made the (nominal) commander-in-chief.[8] He was to stay in the rear, away from the fighting and take the advice of his generals. However, since the paramount command was vested in him no general could act without his permission.[8]

If the campaign was meant to be Aurangzeb's baptism of fire, we must say the baptism was performed at a great distance from the fire![8]

— Dow's account of the war

The campaign was known for its spectacular usage of Artillery according to Mughal accounts more than 120 Cannons and the were combined Mughal armies of 32,000 men captured the Bundela capital during the "Battle of Orchha", on October 4, 1635. Aurangzeb then raised the Mughal flag on the highest terrace of the Jahangir Mahal and installed Devi Singh as the new administrator, while Jhujhar Singh had escaped.[8] After a flurry of events, the Gonds killed Jhujhar and his son in their sleep and sent their heads to the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in December 1635.[8] Aurangzeb then went to Dhamuni where Shah Jahan paid him a visit.[8] There, he ordered the demolition of Bir Singh Dev's temple and had a Mosque constructed.[8] Aurangzeb returned from Dhamuni to wait for his father at Orchha and together they travelled through the country.[8]

Mughal Viceroy

On the way to Sironj they reached Daulatabad where Aurangzeb on July 14, 1636 took formal leave of the emperor to take up his new post as the Viceroy of the Deccan.[8][13] At this time, he began building a new city near the former capital of Khirki which he named Aurangabad after himself. In 1637, he married Rabia Durrani. During this period the Deccan was relatively peaceful. In the Mughal court, however, Shah Jahan began to show greater favour to his eldest son Dara Shikoh.

In 1644, Aurangzeb's sister Jahanara was accidentally burned when the chemicals in her perfume got close to a lamp while in Agra. This event precipitated a family crisis with political consequences. Aurangzeb suffered his father's displeasure when he returned to Agra three weeks after the event, instead of immediately. Shah Jahan had been nursing Jahanara back to health in that time and thousands of vassals had arrived in Agra to pay their respects to the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan and his injured daughter the Mughal princess Jahanara.[8] Shah Jahan was outraged to see Aurangzeb enter the interior palace compound in military attire and immediately dismissed him from his position of Viceroy of the Deccan, Aurnagzeb was also no longer allowed to use Red tents (an imperial prerogative, which Shah Jahan handed over to Dara Shikoh) or associate himself with the official military standard of the Mughal Emperor.[8]

In 1645, he was barred from the court for seven months and mentioned his grief to fellow Mughal commanders. Thereafter, Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan appointed him governor of Gujarat where he served well and was rewarded for bringing stability. In 1647, the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan made him governor of Balkh and Badakhshan (in modern Afghanistan and Tajikistan), replacing Aurangzeb's ineffective brother Murad Baksh. These areas were, at the time, under attack from various tribal oriented forces and Aurangzeb's tough military skills proved useful to deter their threats.

He was appointed governor of Multan and Sindh where he gained fame, and began a protracted military struggle against the Safavid army in an effort to capture the city of Kandahar. He however failed, and fell again into disfavor.

In 1652, Aurangzeb was re-appointed governor of the Deccan. In a bold effort to extend the Mughal Empire, Aurangzeb gathered an army of 40,000 and attacked the Qutbshahis Golconda in the year 1657, and Bijapur in the year 1658. Although Aurangzeb almost came close to achieving total victory both times, the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan ordered the Mughals to withdraw, most probably due to the woes of Dara Shikoh who then interceded and arranged for a peaceful end to the war and gained the support and favor of the Qutbshahis of Golconda and the Adil Shahi of Bijapur.

War of succession

Shah Jahan fell ill in 1657. With this news, the struggle for the succession began. Aurangzeb's eldest brother, Dara Shikoh, was the heir apparent, but the succession proved far from certain when Shah Jahan's second son Shah Shuja declared himself emperor in Bengal. Imperial armies sent by Dara and Shah Jahan soon restrained this effort, and Shuja retreated.

Soon after, Shuja's youngest brother Murad Baksh, with secret promises of support from Aurangzeb, declared himself emperor in Gujarat. Aurangzeb, ostensibly in support of Murad, marched north from Aurangabad, gathering support from nobles and generals. Following a series of victories, Aurangzeb declared that Dara had illegally usurped the throne. Shah Jahan, determined that Dara would succeed him, handed over control of the empire to Dara. A Rajput named Raja Jaswant Singh, fought Aurangzeb at Dharmatpur near Ujjain. Aurangzeb eventually defeated Raja Jaswant Singh and concentrated his forces on his elder brother Dara Shikoh. A series of bloody battles followed, with troops loyal to Aurangzeb defeating Dara Shikoh's armies during the Battle of Samugarh. In a few months, Aurangzeb's forces surrounded Agra. Fearing for his life, Dara Shikoh departed for Delhi, leaving Shah Jahan behind. The old emperor surrendered the Agra Fort to Aurangzeb's nobles, but Aurangzeb refused any meeting with his father, and declared that Dara was no longer a Muslim.

In a sudden reversal, Aurangzeb arrested his brother Murad, whose former supporters defected to Aurangzeb in return for rich gifts.[14] Meanwhile, Dara gathered his forces, and moved to the Punjab. The army sent against Shuja was trapped in the east, its generals Jai Singh and Diler Khan, submitted to Aurangzeb, but allowed Dara's son Suleman to escape. Aurangzeb offered Shuja the governorship of Bengal. This move had the effect of isolating Dara and causing more troops to defect to Aurangzeb. Shuja, however, uncertain of Aurangzeb's sincerity, continued to battle his brother, but his forces suffered a series of defeats at Aurangzeb's hands. Shuja fled to Arakan (in present-day Burma), where he was executed after leading a failed coup.[15] Murad was finally executed, ostensibly for the murder of his former divan Ali Naqi, in 1661.[16]

With Shuja and Murad disposed of, and with his father Shah Jahan immured in Agra, Aurangzeb pursued Dara, chasing him across the north-western bounds of the empire. After a series of battles, defeats and retreats, Dara was betrayed by one of his generals, who arrested and bound him. In 1659, Aurangzeb arranged his formal coronation in Delhi. He had Dara openly marched in chains back to Delhi where he had him executed on arrival on the 30th of August, 1659. Having secured his position, Aurangzeb kept an already weak Shah Jahan under house arrest at the Agra Fort. Shah Jahan died in 1666.

Aurangzeb's reign

Establishment of Islamic law

Soon after his ascension, Aurangzeb abandoned the liberal religious viewpoints of his predecessors.[17] Though Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan's approach to faith was more syncretic than the empire's founder, Aurangzeb's position is not so obvious though his conservative interpretation of Islam and belief in the Sharia (Islamic law) is well documented. Despite claims of sweeping edicts and policies, contradictory accounts exist.[18] Specifically, his compilation of the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, a digest of Muslim law, was either intended for personal use, never enforced, or only poorly done. While some assert the lack of broad adoption was due to an inherent flaw,[19] others insist they were only intended for his observance.[20] While it is possible the war of succession and a continued incursions combined with Shah Jahan's spending made cultural expenditure impossible,[21] Aurangzeb's orthodoxy is also used to explain his infamous "burial" of music. The scene describing the "death of music"(and all other forms of performance) is paradoxically dramatic.

Niccolao Manucci's Storia do Mogor and Khafi Khan's Muntakhab al-Lubab are the only documents which describe the aforementioned event. In Storia do Mogor, Manucci describes the ramifications of Aurangzeb's 1668 decree.[22] Here, Aurangzeb's instructions for the muhtasib seem particularly damning:

In Hindustan both Moguls and Hindus are very fond of listening to songs and instrumental music. He therefore ordered the same official to stop music. If in any house or elsewhere he heard the sound of singing and instruments, he should forthwith hasten there and arrest as many as he could, breaking the instruments. Thus was caused a great destruction of musical instruments. Finding themselves in this difficulty, their large earnings likely to cease, without there being any other mode of seeking a livelihood, the musicians took counsel together and tried to appease the king in the following way: About one thousand of them assembled on a Friday when Aurangzeb was going to the mosque. They came out with over twenty highly-ornamented biers, as is the custom of the country, crying aloud with great grief and many signs of feeling, as if they were escorting to the grave some distinguished defunct. From afar Aurangzeb saw this multitude and heard their great weeping and lamentation, and, wondering, sent to know the cause of so much sorrow. The musicians redoubled their outcry and their tears, fancying the king would take compassion upon them. Lamenting,they replied with sobs that the king's orders had killed Music, therefore they were bearing her to the grave. Report was made to the king, who quite calmly remarked that they should pray for the soul of Music, and see that she was thoroughly well buried. In spite of this, the nobles did not cease to listen to songs in secret. This strictness was enforced in the principal cities.[23][24]

This implies he not only placed a prohibition on music, but actively sought and crushed any resistance. Without music, and implicitly dance, many Hindu-inspired practices[25] would have been impossible. Lavish celebrations of the Emperor's birthday, commonplace since the time of Akbar, would certainly be forbidden under such conditions.

Another instance of Aurangzeb's notoriety, was his policy of temple destruction. Aurangzeb did not just build an isolated mosque on a destroyed temple, he ordered all temples destroyed, among them the Kashi Vishwanath temple, one of the most sacred places of Hinduism, and had mosques built on a number of cleared temple sites. Other Hindu sacred places within his reach equally suffered destruction, with mosques built on them. A few examples: Krishna's birth temple in Mathura; the rebuilt Somnath temple on the coast of Gujarat; the Vishnu [ Images ] temple replaced with the Alamgir mosque now overlooking Benares; and the Treta-ka-Thakur temple in Ayodhya. The number of temples destroyed by Aurangzeb is counted in four, if not five figures. Aurangzeb did not stop at destroying temples, their users were also wiped out; even his own brother Dara Shikoh was executed for taking an interest in Hindu religion; Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur was beheaded because he objected to Aurangzeb's forced conversions.

Francois Bernier, traveled and chronicled Mughal India during the war of succession, notes both Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb's distaste for Christians. This led to the demolition of Christian settlements near the British/European Factories and enslavement of Christian converts by Shah Jahan. Furthermore, Aurangzeb stopped all aid to Christian Missionaries (Frankish Padres) initiated by Akbar and Jahangir.[26][page needed]

Aurangzeb's views on the Jizya (poll tax)

From Aurangzeb's Fatwa:[27]

[Jizyah] refers to what is taken from the Dhimmis, according to [what is stated in] al-Nihayah. It is obligatory upon [1] the free, [2] adult members of [those] who are generally fought, [3] who are fully in possession of their mental faculties, and [4] gainfully employed, even if [their] profession is not noble, as is [stated in] al-Sarajiyyah. There are two types of (jizyah). [The first is] the jizyah that is imposed by treaty or consent, such that it is established in accordance with mutual agreement, according to (what is stated in) al-Kafi. (The amount) does not go above or below (the stipulated) amount, as is stated in al-Nahr al-Fa'iq. (The second type) is the jizyah that the leader imposes when he conquers the unbelievers (kuffar), and (whose amount) he imposes upon the populace in accordance with the amount of property [they own], as in al-Kafi. This is an amount that is pre-established, regardless of whether they agree or disagree, consent to it or not.

The wealthy (are obligated to pay) each year forty-eight dirhams (of a specified weight), payable per month at the rate of 4 dirhams. The next, middle group (wast al-hal) [must pay] twenty-four dirhams, payable per month at the rate of 2 dirhams. The employed poor are obligated to pay twelve dirhams, in each month paying only one dirham, as stipulated in Fath al-Qadir, al-Hidayah, and al-Kafi. (The scholars) address the meaning of "gainfully employed", and the correct meaning is that it refers to one who has the capacity to work, even if his profession is not noble. The scholars also address the meaning of wealthy, poor, and the middle group. Al-Shaykh al-Imam Abu Ja'far, may Allah the most high have mercy on him, considered the custom of each region decisive as to whom the people considered in their land to be poor, of the middle group, or rich. This is as such, and it is the most correct view, as stated in al-Muhit. Al-Karakhi says that the poor person is one who owns two hundred dirhams or less, while the middle group owns more than two hundred and up to ten thousand dirhams, and the wealthy (are those) who own more than ten thousand dirhams...The support for this, according to al-Karakhi is provided by the fatawa of Qadi Khan (died 592/1196). It is necessary that in the case of the employed person, he must have good health for most of the year, as is stated in al-Hidayah. It is mentioned in al-Idah that if a dhimmi is ill for the entire year such that he cannot work and he is well off, he is not obligated to pay the jizyah, and likewise if he is sick for half of the year or more. If he quits his work while having the capacity (to work) he (is still liable) as one gainfully employed, as is [stated in] al-Nihayah. No jizyah is imposed upon their women, children, ill persons or the blind, or likewise on the paraplegic, the very old, or on the unemployed poor, as is stated in al-Hidayah.

Expansion of the Mughal Empire

From the start of his reign up until his death, Aurangzeb engaged in almost constant warfare. He built up a massive army, and began a program of military expansion along all the boundaries of his empire. Aurangzeb pushed north-west into the Punjab and what is now Afghanistan; he also drove south, conquering three Muslim kingdoms: Nizamss of Ahmednagar, Adilshahis of Bijapur and Qutbshahis of Golconda these new territories were administered by the Mughal Nawabs loyal to the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb.

Only one remaining ruler Abul Hasan Qutb Shah the Qutbshahi ruler of Golconda refused to surrender, he and his servicemen fortified themselves at Golconda, and fiercely protected the Kollur Mine (then, the worlds only diamond mine). In the year 1687 the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb led his grand Mughal army against the Deccan Qutbshahi fortress of Golconda the only diamond producing city in the world at that time. The Qutbshahi's had constructed massive fortifications throughout successive generations on a granite hill over 400ft high with an enormous 8mile wall enclosing the city. The main gates of Golconda had the ability to repulse any War elephant attack. In fact of the 18 most famous diamonds in the world 13 came from the Golconda Kollur Mine ruled by the then Qutbshahi dynasty the city was also home to the most famous diamond cutters. For the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb the conquest of Qutbshahi ruled Golconda was crucial to the legitimacy of his reign throughout the realm. Although the Qutbshahi's maintained impregnable efforts defending their walls, at night the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and his infantry usually assembled and erected complex scaffolding that allowed them to scale the high walls. During the eight month siege the Mughals faced many hardships and finally the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and his managed to penetrate the walls by capturing a gate prompting the Qutbshahi's of Golconda and the ruler Abul Hasan Qutb Shah to surrender peacefully and hand over the Nur-Ul-Ain Diamond, Great Stone Diamond, Kara Diamond, Darya-e-Nur, The Hope Diamond, the Wittelsbach Diamond and the The Regent Diamond making the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb the richest monarch in the world.[28]

This combination of military expansion and religious intolerance had deeper consequences. Though he succeeded in expanding Mughal control, it was at an enormous cost in lives and treasure. And, as the empire expanded in size, Aurangzeb's chain of command grew weaker. The Sikhs of the Punjab grew both in strength and numbers, and launched rebellions. The Marathas waged a war with Aurangzeb which lasted for 27 years. Even Aurangzeb's own armies grew restive — particularly the fierce Rajputs, who were his main source of strength. Aurangzeb gave a wide berth to the Rajputs, who were mostly Hindu. While they fought for Aurangzeb during his life, on his death they immediately revolted against his successors.

With much of his attention on military matters, Aurangzeb's political power waned, and his provincial Nawabs grew in authority.

Foreign Relations

Aurangzeb sent some of the finest ornate gifts such as carpets, lamps, tiles and others to the Islamic shrines at Mecca and Medina.[29] Subhan Quli, Balkh's Uzbek ruler was the first to recognize him in 1658 and requested for a general alliance. Aurangzeb warmly received the embassy of Shah Abbas II of Persia in 1660 and returned them with gifts.

In the year 1688 the desperate Ottoman Sultan Suleiman II urgently requested for assistance against the rapidly advancing Austrians, however the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and his forces were heavily engaged in the Deccan Wars to commit any formal assistance to their Ottoman allies.

In 1686 English East India Company which had unsuccessfully tried to obtain a firman, an imperial directive that would grant England regular trading privileges throughout the Mughal empire, initiated so-called Child's War with the empire which ended in disaster for the English. In 1690 the company sent envoys to Aurangzeb's camp to plead for a pardon. The company's envoys had to prostrate themselves before the emperor, pay a large indemnity, and promise better behavior in the future.

In September 1695, English pirate Henry Every perpetrated one of the most profitable pirate raids in history with his capture of a Grand Mughal convoy near Surat. The Indian ships had been returning home from their annual pilgrimage to Mecca when the pirates struck, capturing the Ganj-i-Sawai, reportedly the greatest ship in the Muslim fleet, and its escorts in the process. When news of the piracy reached the mainland, a livid Aurangzeb nearly ordered an armed attack against the English city of Bombay, though he finally agreed to compromise after the East India Company promised to pay financial reparations, estimated at £600,000 by the Mughal authorities.[30] Meanwhile, Aurangzeb shut down four of the East India Company's factories, imprisoned the workers and captains (who were nearly lynched by a rioting mob), and threatened to put an end to all English trading in India until Every was captured.[30] The Privy Council and East India Company offered a massive bounty for Every's apprehension, leading to the first worldwide manhunt in recorded history.[31] However, Every successfully eluded capture.

Revenue administration

Emperor Aurangzeb's exchequer raised a record £100 million in annual revenue through various sources like taxes, customs and land revenue, et al. from 24 provinces.[32] A pound sterling was exchanged at 10 rupees then.

| No. | Province | Land Revenue (1697) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | Total | £38,624,680 | |

| 1 | Bijapur | £5,000,000 | |

| 2 | Golconda | £5,000,000 | |

| 3 | Bengal | £4,000,000 | |

| 4 | Gujarat | £2,339,500 | |

| 5 | Lahore | £2,330,500 | |

| 6 | Agra | £2,220,355 | |

| 7 | Ajmere | £2,190,000 | |

| 8 | Ujjain | £2,000,000 | |

| 9 | Deccan | £1,620,475 | |

| 10 | Berar | £1,580,750 | |

| 11 | Delhi | £1,255,000 | |

| 12 | Behar | £1,215,000 | |

| 13 | Khandesh | £1,110,500 | |

| 14 | Rajmahal | £1,005,000 | |

| 15 | Malwa | £990,625 | |

| 16 | Allahabad | £773,800 | |

| 17 | Nande (Nandair) | £720,000 | |

| 18 | Baglana | £688,500 | |

| 19 | Thatta (Sindh) | £600,200 | |

| 20 | Orissa | £570,750 | |

| 21 | Multan | £502,500 | |

| 22 | Kashmir | £350,500 | |

| 23 | Kabul | £320,725 | |

| 24 | Bakar (Sukkur, Sindh) | £240,000 |

Religious Policy : Intolerance towards Hindus & Sikhs

Aurangzeb was known for being intolerant towards 'infidel' Hindus and Sikhs.[5] During his reign, tens of thousands of temples were desecrated: their facades and interiors were defaced and their murtis (divine images) looted.[6] In many cases, temples were destroyed entirely; in numerous instances mosques were built on their foundations, sometimes using the same stones. Among the temples Aurangzeb destroyed were three that are most sacred to Hindus, in Varanasi (Kashi Vishwanath Temple), Mathura (Kesava Deo Temple) & Gujarat (Somnath temple). In all these cases, he had large mosques built on the sites.[6][33]

He re-imposed heavy jizya and land tax on Hindus and encouraged forcible conversion of Hindus to Islam.[5][34]From the standpoint of Aurangzeb's Hindu subjects, the real impact of his policies may have started to have been felt in 1668-69. Hindu religious fairs were outlawed in 1668, and an edict of the following year prohibited construction of Hindu temples as well as the repair of old ones.[34][7] Also in 1669, Aurangzeb discontinued the practice, which had been originated by Akbar, of appearing before his subjects and conferring darshan on them, or letting them receive his blessings as one might, in Hinduism, take the darshan of a deity and so receive its blessings. Though the duty (internal customs fees) paid on goods was 2.5%, double the amount was levied on Hindu merchants from 1665 onwards. In 1679, Aurangzeb went so far as to reimpose, contrary to the advice of many of his court nobles and theologians, the jiziya or graduated property tax on non-Muslims, and according to one historical source, elephants were deployed to crush the resistance in the area surrounding the Red Fort of Hindus who refused to submit to jiziya collectors.[34] The historian John F. Richards opines, quite candidly, that "Aurangzeb's ultimate aim was conversion of non-Muslims to Islam. Whenever possible the emperor gave out robes of honor, cash gifts, and promotions to converts. It quickly became known that conversion was a sure way to the emperor's favor.[34][5]

Forced conversions & Assassination of the Sikh Guru

Aurangzeb cherished the ambition of converting India into a land of Islam.[5] This philosophy was also pleaded by Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (1569–1624), leader of the Naqashbandi School, to counter the liberal policies of Akbar's reign.[35]

The Emperor's experiment was carried out in Kashmir. The viceroy of Kashmir, Iftikar Khan (1671–1675) carried out the policy vigorously and set about converting non-Muslims by force.[35]

A group of Kashmiri Pandits (Kashmiri Hindu Brahmins), approached Guru Tegh Bahadur and asked for help. They, on the advice of the Guru, told the Mughal authorities that they would willingly embrace Islam if Guru Tegh Bahadur, did the same.[7][36]

Orders of the arrest of the Guru were issued by Aurangzeb, who was in the present-day North West Frontier Province of Pakistan subduing Pushtun rebellion. The Guru was arrested at a place called Malikhpur near Anandpur after he had departed from Anandpur for Delhi. Before departing he nominated his son, Gobind Rai (Guru Gobind Singh) as the next Sikh Guru.[36]

He was arrested, along with some of his followers, Bhai Dayala, Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das by Nur Muhammad Khan of the Rupnagar police post at the village Malikhpur Rangharan, in Ghanaula Parganah, and sent to Sirhind the following day. The Faujdar (Governor) of Sirhind, Dilawar Khan, ordered him to be detained in Bassi Pathana and reported the news to Delhi. His arrest was made in July 1675 and he was kept in custody for over three months. He was then cast in an iron cage and taken to Delhi in November 1675.[36]

The Guru was put in chains and ordered to be tortured until he would accept Islam.[36] When he could not be persuaded to abandon his faith to save himself from persecution, he was asked to perform some miracles to prove his divinity. On his refusal, Guru Tegh Bahadur was beheaded in public at Chandni Chowk on 11 November 1675.[36][35] Guru Ji is also known as "Hind Di Chadar" i.e. "the shield of India", suggesting that to save Hinduism, Guru Ji gave his life. He's honoured and remembered as the man who championed the rights for all religious freedom.[7]

Coins Gallery

-

Half rupee

-

Rupee coin showing full name

-

Rupee with square area

-

A copper dam of Aurangazeb

Aurangzeb felt that verses from the Quran should not be stamped on coins, as done in former times, because they were constantly touched by the hands and feets of people.[8] His coins had the name of the mint city and the year of issue on one face, and, the following couplet on other

King Aurangzeb Alamgir

Stamped coins , in the world , like the bright full moon.[8]— Mir Abdul Baqi Suhbai

Rebellions

Since Aurangzeb's reign is marked by numerous rebellions in the distant provinces of the Mughal Empire, many historians believe that Mughal Nawabs were incapable of bridging the gap between the rulers and the people; therefore many new identities emerged along with it armed rebellion.

- In 1669, the Jat peasants of Bharatpur around Mathura revolted and created Bharatpur state, fomenting a fierce rebellion around the Mughal capital.

- In 1670, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, assassinated the Adil Shahi commander Afzal Khan and later, nearly killed the Mughal Viceroy Shaista Khan, while waging war against Aurangzeb. Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and his forces ravaged the Deccan, Janjira and Surat and tried to gain control of vast territories. However by 1689 Auranzeb's armies had captured Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj's, son Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj alive and executed him.[37]

- In 1672, the Satnami, a sect concentrated in an area near Delhi, under the leadership of Bhirbhan and some Satnami, took over the administration of Narnaul, but they were eventually crushed upon Aurangzeb's personal intervention with very few escaping alive.[38][39]

- In 1671, the Battle of Saraighat was fought in the easternmost regions of the Mughal Empire against the Ahom Kingdom. The Mughals led by Mir Jumla II and Shaista Khan were forced to retreat after the respected Mughal Admiral Munnawar Khan was killed in action.

Deccan Wars (Marathas)

(See- Maratha Empire)

In the time of Shah Jahan, the Deccan had been controlled by three Muslim kingdoms: Ahmednagar (Nizam Shahi), Bijapur (Adilshahi) and Golconda (Qutbshahi). Following a series of battles, Ahmednagar was effectively divided, with large portions of the kingdom ceded to the Mughals and the balance to Bijapur. One of Ahmednagar's generals, a Hindu Maratha named Shahaji Raje, joined the Bijapur court. Shahaji Raje sent his wife Jijabai and young son Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj to Pune to manage his Jagir.[40]

In 1657, while Aurangzeb attacked Golconda and Bijapur, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, using guerrilla tactics, took control of three Adilshahi forts formerly under his father's command. With these victories, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj assumed de facto leadership of many independent Maratha clans. The Marathas harried the flanks of the warring Adilshahis and Mughals, gaining weapons, forts, and territory.[41] Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj's small and ill-equipped army survived an all out Adilshahi attack, and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj personally killed the Adilshahi general, Afzal Khan.[42] With this event, the Marathas transformed into a powerful military force, capturing more and more Adilshahi and Mughal territories.[43]

Just before Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj's coronation in 1659, Aurangzeb sent his trusted general and maternal uncle Shaista Khan, the Wali in Golconda to recover forts lost to the Maratha rebels. Shaista Khan drove into Maratha territory and took up residence in Pune. But in a daring raid on the governor's palace in Pune during a midnight wedding celebration, the Marathas killed Shaista Khan's son and maimed Shaista Khan by cutting off the fingers of his hand. Shaista Khan, however, survived and was re-appointed the administrator of Bengal going on to become a key commander in the war against the Ahoms. It is believed that Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj presented the head of Afzal Khan and the fingers of Shaista Khan to his mother Jijabai, symbolizing his swift victory over the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb.

However, Aurangzeb ignored the rise of the Marathas for the next few years as he was occupied with other religious and political matters including the rise of Sikhism. Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj captured forts belonging to both Mughals and Bijapur. At last The Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb ordered the armament of the Daulatabad Fort with two bombards [44](the Daulatabad Fort was later utilized as a future Mughal bastion during the Deccan Wars). The Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb also sent his powerful general Raja Jai Singh of Amber, a Hindu Rajput, to attack the Marathas. Jai Singh won the fort of Purandar after fierce battle in which the Maratha commander Murarbaji fell. Foreseeing defeat, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj agreed for a truce and a meeting with Aurangjeb at Delhi. Jai Singh also promised the Maratha hero his safety, placing him under the care of his own son, the future Raja Ram Singh I. However, circumstances at the Mughal court were beyond the control of the Raja, and when Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and his son Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj went to Agra to meet Aurangzeb, they were placed under house arrest, from which they managed to effect a daring escape.[45]

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj returned to the Deccan, and was given the title Chhatrapati of the Maratha Empire in 1674.[46] While Aurangzeb continued to send troops against him, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj expanded Maratha control throughout the Deccan until his death in 1680. Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was succeeded by his son Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj. Militarily and politically, Mughal efforts to control the Deccan continued to fail.

When Maharaja Jaswant Singh of Jodhpur died in 1679, a conflict ensued over who would be the next Raja. Aurangzeb's choice of a nephew of the former Maharaja was not accepted by other members of Jaswant Singh's family and they rebelled, albeit in vain. Thereat, Aurangzeb seized control of Jodhpur. He also moved on Udaipur, which was the only other state of Rajputana to support the rebellion. There was never a clear resolution to this conflict, although it is noted that the other Rajputs, including the celebrated Kachhwaha Rajput clan of Raja Jai Singh, the Bhattis, and the Rathores, remained loyal. On the other hand, Aurangzeb's third Aurangzeb's son Akbar left the Mughal court along with a few Muslim Mansabdar supporters and joined Muslim rebels in the Deccan. Aurangzeb in response moved his court to Aurangabad and took over command of the Deccan campaign. The rebels were defeated and Akbar fled south to the shelter of the Maratha chhatrapati Chhatrapati Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj Maharaj, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj's successor. More battles ensued, and Akbar fled to Persia and never returned.[47]

In 1689 Aurangzeb's forces captured Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj, his successor chhatrapati Rajaram and his, Maratha forces fought individual battles against the forces of the Mughal Empire, and territory changed hands repeatedly during years of interminable warfare. As there was no central authority among the Marathas, Aurangzeb was forced to contest every inch of territory, at great cost in lives and money. Even as Aurangzeb drove west, deep into Maratha territory — notably conquering Satara — the Marathas expanded their attacks further into Mughal lands - Malwa, Hyderabad and Jinji in TamilNadu. Aurangzeb waged continuous war in the Deccan for more than two decades with no resolution.[48] He thus lost about a fifth of his army fighting rebellions led by the Marathas in Deccan India. He came down thousands of miles to the Deccan to conquer the Maratha confederacy and eventually died at the age of 90, during his final campaign against the Maratha confederacy.[49]

Ahom Campaign

Aurangzeb after ascending on the throne of Delhi ordered Mir Jumla II to invade Cooch Behar and Assam and re-establish Mughal prestige in eastern India. After having occupied Koch Behar had also declared its independence. Mir Jumla II entered Assam in the beginning of 1662. He easily repulsed the feeble resistance offered by the Assamese at the garrisons between Manaha and Guwahati. He occupied one garrison after another, and Pandu, Guwahati, and Kajali fell into the hands of the Mughals practically unopposed.

The easy success of Mir Jumla II was due to dissatisfaction in the Assam camp. The leading commanders and the officers were the exclusive monopolies of the Tai-Ahom. But. King Jayadhwaj Singha (Sutamla, 1648–1663) had appointed a Kayastha as viceroy of lower Assam and commander-in-chief of the Ahom army despatch against Mir Jumla II leading to resentment among the ranks. This officer was Manthir Bharali Barua of Bejdoloi family. He was also appointed Parbatia Phukan. This appointment caused bitter resentment among the hereditary Ahom nobles and commanders and the resistance which they offered to the invaders was neither worthy of the efficient military organisation of the Ahoms nor of the reputation which they acquired by repeated success in their enterprises against foreigners, and Mir Jumla II’s march into Assam was an uninterrupted series of triumph and victories though the real secret of his success, namely, defection in Ahom camp, which has not been touched upon by any historian of the expedition.

The Ahoms, however, recovered their senses when the hostile force reached the neighbourhood of Kaliabor. They concentrated their defence at Simalugarh and Samdhara. In February 1662, Mir Jumla II laid siege to Simalugarh and after severe hand-to-hand fight, the Ahoms abandoned the fort and took to flight. The Ahom forces at Samdhara on the opposite bank, being unnerved by the fall of Simalugarh, left their charge without any opposition worth the name. After this brilliant success, Mir Jumla II entered the Ahom capital Garhgaon on 17 March 1662. The Ahom king Jayadhwaj took shelter in the eastern hills abandoning his capital and all his treasures. Immense spoils fell into the hands of the Mughal Empire – 82 elephants, about 3 lakhs of coins in gold and silver, 675 big guns, about 4750 maunds of gunpowder in boxes, 7828 shields, 1000 odd ships, and 173 stores of rice.

But, Mir Jumla II conquered only the soil of Ahom capital and neither the king nor the country. The rainy season was fast approaching and so Mir Jumla II halted there and made necessary arrangements for holding the conquered land. Communications with the imperial fleet at Lakhau as well as with Dacca were arranged. But the torrential rain and violence of the rivers caused immense hardship to the Mughals and the communication with the Mughal fleet and Lakhau and with Dacca became completely disrupted.

The Ahoms took the fullest advantage of the unspeakable hardship of the Mughals. With the progress of monsoon, the Ahoms easily recovered all the country east of Lakhau. Only Garhgaon and Mathurapur remained in the possession of Mughals. The Ahoms were not slow to take advantages of the miserable plight of the Mughals. The Ahom king came out of his refuge and ordered his commanders to expel the invaders from his kingdom. A serious epidemic broke out in the Mughal camp at Mathurapur, which took away the lives of hundreds of Mughal soldiers. There was no suitable diet or comfort in the Mughal camp. At last life became unbearable at Mathurapur and hence the Mughals abandoned it.[9]

By the end of September the worst was over. The rains decreased, and flood went down, roads reappeared and communications became easier. The contact with the Mughal fleet at Lakhau was restored which cheered the long suffering Mughal garrison. The Mughal army under Mir Jumla II joined the fleet at Devalgaon. The Ahom king Jayadhwaj Singha took refuge in hill again. But in December, Mir Jumla II fell seriously ill and the soldiers refused to advance any further. Meanwhile the Ahom king became extremely anxious for peace. At last a treaty was concluded at Ghilajharighat in January 1663, according to which the Ahoms ceded western Assam to the Mughals, promised a war indemnity of three lakhs of rupees and ninety elephants. Besides, the king had to deliver his only child and daughter Ramani Gabharu, as well as his niece, the daughter of the Tipam Raja to the harem of the Mughal emperor. Thus, according to the treaty Jayadhwaj Singha transferred Kamrup to the possession of the Mughals and promised to pay a heavy war indemnity.[10][11]

The question of prompt payment of war indemnity of elephants and cash became a source of friction between the Ahoms and the Mughals. The first instalment was paid by Jayadhwaj promptly. But as soon as Mir Jumla II withdrew from Assam the Ahoms began to default. Jayadhwaj Singha’s successor Chakradhwaj Singha (Supangmung, 1663–1670) was against any payment at all on principle. He shouted out from his throne: - "Death is preferable to a life of subordination to foreigners". In 1665 the king summoned an assembly of his ministers and nobles and ordered them to adopt measures for expelling the Mughals from western Assam, adding—"My ancestors were never subordinate to any other people; and I for myself cannot remain under the vassalage of any foreign power. I am a descendant of the Heavenly king and how can I pay tribute to the wretched foreigners."[12][13]

A large portion of the war indemnity still remained undelivered for which the Ahom king had to receive threatening letters from Syed Firoz Khan, the new Fauzadar at Guwahati.[14][15][16][17] On receiving Firoz Khan’s letter the Ahom king made up his mind to fight.[18] On Thursday, Bhadra 3, 1589 saka near aboutAugust 20, 1667 the Ahom army started from the capital and sailed down the Brahmaputra in two divisions. They encamped at Kaliabor, the Vice Regal headquarters, from where they conducted their war operations against the Mughals. Syed Firoz Khan, the imperial governor of Guwahati and his army were not prepared for such an eventuality, with the result that the Ahoms gained a series of victories over the enemy. The Ahom army on the south bank was successful in their fighting. Their chief objective was the capture of Itakhuli which is a small hill on the south bank of the Brahmaputra at Guwahati. In 2 November 1667, Itakhuli and the contiguous garrison of Guwahati fell into the hands of the Ahoms. Enemy was chased down to the mouth of the Manaha river, the old boundary between Assam and Mughal India. The Ahom also succeeded in bringing back the Assamese subjects who had previously been taken as captives by the Mughals during the expedition of Mir Jumla II.[19][20] Thus within the short span of two months the Ahoms succeeded their lost possession and along with it their lost prestige and glory, this was due to the determination and courage of Ahom king Chakradhwaj Singha. On receiving the news of victory the king cried out-"It is now that I can eat my morsel of food with ease and pleasure". The success of the Ahoms in recovering possession of Guwahati and lower Assam forms a momentous chapter in the history of their conflicts with the Mughals. Thus Auranzeb and his Mughal army had to face lot of trouble due to the Ahom power of Assam in the east and from the Maratha power in the west.

Sikhs

Early in Aurangzeb's reign, various insurgent groups of Sikhs engaged Mughal troops in increasingly bloody battles. The ninth Sikh Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, like his predecessors was opposed to conversion of the local population as he considered it un-Islamic. Approached by Brahmans from Kashmir to help them retain their faith and avoid conversion, the Guru took on the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. In his message to Aurangzeb, he said that he is not a Hindu but he will fight for the rights of all to practice their religion with freedom. This posturing of Guru Tegh Bahadur did not go well with the emperor who perceived the rising popularity of the Guru as a threat to his sovereignty. In 1670, the emperor executed Guru Tegh Bahadur,[36][35] which infuriated the Sikhs. In response, his son and successor, the tenth Guru of Sikhism Guru Gobind Singh further militarized his followers.

The Khalsa, the Sikh Army, are the first in history to abolish the Muslim states and Mughal Empire in the whole province in one stroke. The Singhs [Lions], led by Banda Singh Bahadur took over many Muslim and Mughal lands, establishing a Sikh Empire. Other existing Muslim Emperors proclaimed a jihad or a holy war against the Banda and the Khalsa. However many Muslim army’s and their Emperors fled in dismay and despair after Wazir Khan's head was stuck up on a spear and lifted high up by a Sikh who took his seat at Sirhind, Muslim troops on beholding the head took alarm.

In an attempt to dislodge the Sikhs, Aurangzeb vowed that the Guru and his Sikhs would be allowed to leave Anandpur safely. Aurangzeb is said to have validated this promise in writing. However Aurangzeb deliberately failed to keep his promise and when the remaining few Sikhs were leaving the fort under the cover of darkness, the Mughals were alerted and enagaged them in battle once again; where two of the younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh [Zoravar Singh and Fateh Singh] of 9 and 7 yrs respectively were bricked up alive within a wall by Wazir Khan in Sirhand (Punjab). The other two elder sons [Ajit Singh and Jujhar Singh] as well as many other Singhs fought with giant Mughal force, the events of which Guru Gobind Singh wrote a letter to Aurangzeb, called a Zafarnamah "Epistle of Victory". The Emperor died shortly after on March 3, 1707. Eventually the Guru was attacked and wounded by one of Aurangzeb's soldier, when he was sleeping, Jamshed Khan who was beheaded by the Guru, at the same time. The Guru would later die because the inflicted wounds.

The Pashtun rebellion

The Pashtun tribesmen of the Empire were considered the bedrock of the Mughal Army. They were the Empire's from the threat bulwark in the North-West as well as the main fighting force against the Sikhs and Marathas. The Pashtun revolt in 1672 under the leadership of the warrior poet Khushal Khan Khattak[50] was triggered when soldiers under the orders of the Mughal Governor Amir Khan allegedly attempted to molest women of the Safi tribe in modern day Kunar. The Safi tribes retaliated against the soldiers. This attack provoked a reprisal, which triggered a general revolt of most of tribes. Attempting to reassert his authority, Amir Khan led a large Mughal Army to the Khyber Pass, where the army was surrounded by tribesmen and routed, with only four men, including the Governor, managing to escape.

After that the revolt spread, with the Mughals suffering a near total collapse of their authority in the Pashtun belt. The closure of the important Attock-Kabul trade route along the Grand Trunk road was particularly disastrous. By 1674, the situation had deteriorated to a point where Aurangzeb camped at Attock to personally take charge. Switching to diplomacy and bribery along with force of arms, the Mughals eventually split the rebels and partially suppressed the revolt, although they never managed to wield effective authority outside the main trade route. The anarchy that became endemic on the Empire's North-Western frontier as a consequence ensured that Nadir Shah's invading forces, half a century later, faced little resistance on the road to Delhi.

Legacy

By the year 1689, almost all of Southern India was a part of the Mughal Empire and after the conquest of Golconda the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb may have been the most richest and powerful man alive, Mughal victories in the south expanded the Mughal Empire to 1.25million square miles, ruling over 150million subjects, nearly 1/4th of the worlds population. But this supremacy was short-lived.[51]

Aurangzeb's vast imperial campaigns against rebellion-affected areas of the Mughal Empire, caused his opponents to exaggerate the "importance" of their rebellions. The results of his vast campaigns were made worse by the incompetence of his regional Nawabs.[52]

Muslim views regarding Aurangzeb vary, most Muslim historians believe that the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb was the last powerful ruler of an empire inevitably on the verge of decline. The major rebellions organized by the Sikhs and the Marathas were long embedded and had deep roots in the remote regions of the Mughal Empire.

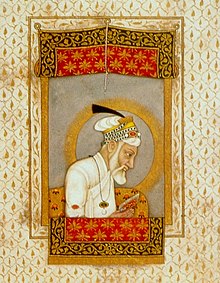

Unlike his predecessors, Aurangzeb considered the royal treasury to be held in trust for the citizens of his empire. He made caps and copied the Quran to earn money for his use. He did not use the royal treasury for personal expenses or extravagant building projects excepting perhaps the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, which, for 313 years remained the world's largest mosque and still remains to this day the 5th largest mosque in the world. He also added a small marble mosque known as the Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) to the Red Fort complex in Delhi. His constant warfare especially with the Marathas, however, drove his empire to the brink of bankruptcy just as much as the wasteful personal spending and opulence of his predecessors.

Stanley Wolpert writes in his New History of India that:

the conquest of the Deccan, to which, Aurangzeb devoted the last 26 years of his life, was in many ways a Pyrrhic victory, costing an estimated hundred thousand lives a year during its last decade of futile chess game warfare...The expense in gold and rupees can hardly be accurately estimated. [Aurangzeb]'s moving capital alone- a city of tents 30 miles in circumference, some 250 bazaars, with a 1⁄2 million camp followers, 50,000 camels and 30,000 elephants, all of whom had to be fed, stripped peninsular India of any and all of its surplus grain and wealth... Not only famine but bubonic plague arose...Even Aurangzeb, had ceased to understand the purpose of it all by the time he was nearing 90... "I came alone and I go as a stranger. I do not know who I am, nor what I have been doing," the dying old man confessed to his son in February 1707.[53]

He died in Ahmednagar on Friday, 20 February 1707 at the age of 88, having outlived many of his children. His modest open-air grave in Khuldabad expresses his deep devotion to his Islamic beliefs. The tomb lies within the courtyard of the shrine of the Sufi saint Shaikh Burham-u'd-din Gharib (died 1331), who was a disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi.[54]

After Aurangzeb's death, his son Bahadur Shah I took the throne. The Mughal Empire, both due to Aurangzeb's over-extension and Bahadur Shah's weak military and leadership qualities, entered a period of terminal decline. Immediately after Bahadur Shah occupied the throne, the Maratha Empire — which Aurangzeb had held at bay, inflicting high human and monetary costs — consolidated and launched effective invasions of Mughal territory, seizing power from the weak emperor. Within a century of Aurangzeb's death, the Mughal Emperor had little power beyond the walls of Delhi.

See also

References

- ^ (Urdu: اورنگزیب, (sometiens spelled Aurangzeb), full official title: Al-Sultan al-Azam wal Khaqan al-Mukarram Hazrat Abul Muzaffar Muhy-ud-Din Muhammad Aurangzeb Bahadur Alamgir I, Badshah Ghazi, Shahanshah-e-Sultanat-ul-Hindiya Wal Mughaliya

- ^ The World Book Encyclopedia Volume:A1 (1989) pg 894-895

- ^ Mughal Rule in India - By Stephen Meredyth Edwardes, Herbert Leonard Offley Garrett

- ^ Gascoigne, Bamber (1971). The Great Mughals. New York:Harper & Row. pp. 233

- ^ a b c d e [1]Intolerant ruler: Aurangzeb (bbc.co.uk)

- ^ a b c [2]Destruction of Hindu Temples by Aurangzeb

- ^ a b c d [3]Guru Tegh Bahadur (BBC.CO.UK)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Maasir-i-Alamgiri A history of Emporer Aurangzeb Alamgir - Sir Jadunath Sarkar. First published 1947.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ "300 Year Old Quran Inscribed By Aurangzeb To Be Auctioned".

- ^ "Emirates owner to sell Quran inscribed by Aurangzeb".

- ^ Maktubat (collected letters) of Khwaja Muhammad Masoom

- ^ http://www.scribd.com/doc/55837292

- ^ Khafi Khan, Muntakhab ul-Lubab, p.129

- ^ The Cambridge History of India (1922), vol. IV, p. 215.

- ^ The Cambridge History of India (1922), vol. IV, p. 481.

- ^ The Cambridge History of India (1922), vol. IV, p. 228.

- ^ John Keay,India: A History(2001) p.336

- ^ Katherine Butler Brown, Did Aurangzeb Ban Music? (2007), p.91

- ^ Hanafi law was sought to be codified under Aurangzeb but the work of several hundred jurists, called Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, seems too inclined to favour the Mughal elite to be useful for today's egalitarian society

- ^ Katherine Butler Brown, Did Aurangzeb Ban Music?(2007), p.114

- ^ Taymiya R. Zaman Inscribing Empire: Sovereignty and Subjectivity in Mughal Memoirs(2007) p. 153

- ^ It should be noted; this date is never specified by Manucci. However, events surrounding the statement, the chronology of which are not under dispute, are used to extrapolate a general timeframe.

- ^ Niccolao Manucci, Storia do Mogor (1907), vol. 11 p.8

- ^ Pdf of Storia do Mogor vol. ii

- ^ Pdf which Details: Balcony Appearances and Other Such Hindu Inspired Mughal Activities

- ^ Francois Bernier; Travels Through the Mogul Empire ISBN 978-1931641227

- ^ Al-Fatawa al-Alamgiriyyah : Al-Fatawa al-Hindiyyah fi Madhhab al-Imam al-A'zam Abi Hanifah al-Nu'man (Beirut: Dar al-Ma'rifah, 1973), 2:244-245.- Translated by Anver Emon of the Department of History, UCLA.

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OyyZw7_MZAM&feature=related

- ^ "Hajj: An Indian Experience in History- Dr Ausaf Sayeed".

- ^ a b Burgess, Douglas R. (2009). "Piracy in the Public Sphere: The Henry Every Trials and the Battle for Meaning in Seventeenth‐Century Print Culture". Journal of British Studies. 48 (4). The University of Chicago Press: 887–913. doi:10.1086/603599.

- ^ Burgess, Douglas R. (2009). The Pirates' Pact: The Secret Alliances Between History's Most Notorious Buccaneers and Colonial America. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 144. ISBN 9780071474764.

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]Aurangzeb: Temples destruction

- ^ a b c d [6]AURANGZEB: RELIGIOUS POLICIES

- ^ a b c d [7]Converted Kashmir

- ^ a b c d e f [8]Guru Tegh Bahadur

- ^ An atlas and survey of South Asian history By Karl J. Schmidt

- ^ Mughal rule in India By Stephen Meredyth Edwardes, Herbert Leonard Offley Garrett

- ^ Students' Britannica India By Dale Hoiberg, Indu Ramchandani

- ^ Kincaid, Dennis (1937). The Grand Rebel. London:Collins Press. pp. 50,51.

- ^ Kincaid 1937:72-78

- ^ Kincaid 1937:121-125

- ^ Kincaid 1937:130-138

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7FbxrM5rWB8

- ^ Kincaid 1937:197

- ^ Kincaid 1937:283

- ^ Gascoine 1971:228-229

- ^ Gascoine 1971:239-246

- ^ The Story of the World - By S. Wise Bauer, Sarah Park, James

- ^ "Biography: Khushal Khan Khattak" Afghan-Web

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P-Ygz9VbiE0

- ^ The truth about Aurangzeb

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley (2003). New History of India (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195166779.

- ^ http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e239?_hi=1&_pos=1

Additional references

- Essays on Islam and Indian History, Richard M. Eaton. Reprint. New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2002 (ISBN 0-19-566265-2). -- Eaton's essay "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States", which attempts to comprehend Aurangzeb's motivation in destroying temples, has generated much recent debate

- The Peacock Throne, Waldemar Hansen (Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1972). -- a very British accounting of Aurangzeb's , but filled with excellent references and source material

- A Short History of Pakistan, Dr. Ishtiaque Hussain Qureshi, University of Karachi Press.

- Delhi, Khushwant Singh, Penguin USA, Open Market Ed edition, 5 February 2000. (ISBN 0-14-012619-8)

- Muḥammad Bakhtāvar Khān. Mir'at al-'Alam: History of Emperor Awangzeb Alamgir. Trans. Sajida Alvi. Lahore: Idārah-ʾi Taḥqīqāt-i Pākistan, 1979.

- 'The Pearson Guide to the Central Police Forces' By Thorpe Edgar

External links

- Read the complete history on Aurangzeb & other Mughal Emperors after several research

- Aurangzeb, as he was according to Mughal Records

- Quran hand-written by the emperor- BBC

- Article on Aurganzeb from MANAS group page, UCLA

- Aurangzeb- BBC

- The Tragedy of Aureng-zebe Text of John Dryden's drama, based loosely on Aurangzeb and the Mughal court, 1675

- Legends on Indian Coins

- Coins of Aurangzeb

- [9]