Spirited Away

| Spirited Away | |

|---|---|

| File:Spirited Away poster.JPG International film poster | |

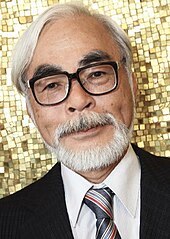

| Directed by | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Screenplay by | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Story by | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Produced by | Toshio Suzuki |

| Starring | Rumi Hiiragi Miyu Irino Mari Natsuki Bunta Sugawara |

| Cinematography | Atsushi Okui |

| Edited by | Takeshi Seyama |

| Music by | Joe Hisaishi |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Japan: Toho International: Walt Disney Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 125 minutes |

| Country | Template:Film Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | ¥1.9 billion (US$19 million)[1] |

| Box office | ¥27,492,509,500 ($274,925,095) |

Spirited Away (千と千尋の神隠し, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, lit. "The Spiriting Away of Sen and Chihiro") is a 2001 Japanese animated fantasy-adventure film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki and produced by Studio Ghibli. The film tells the story of Chihiro Ogino, a sullen ten-year-old girl who, while moving to a new neighborhood, becomes trapped in an alternate reality that is inhabited by spirits and monsters.[2] After her parents are transformed into pigs by the witch Yubaba, Chihiro takes a job working in Yubaba's bathhouse to find a way to free herself and her parents and escape back to the human world.

Miyazaki wrote the script after he decided the film would be based on his friend's ten-year-old daughter, who came to visit his house each summer. At the time, Miyazaki was developing two personal projects, but they were rejected. Production of Spirited Away began in 2000. During production, Miyazaki based the film's settings at a museum in Koganei, Tokyo. However, Miyazaki realized the film would be over three hours and decided to cut out several parts of the story for its July 27, 2001 release. Pixar director John Lasseter, a fan of Miyazaki, was approached by Walt Disney Pictures to supervise an English-language translation for the film's North American release. Lasseter hired Kirk Wise as director and Donald W. Ernst as producer of the adaptation.

When released, Spirited Away became the most successful film in Japanese history, grossing over $274 million worldwide, and receiving critical acclaim. The film overtook Titanic (at the time the top grossing film worldwide) in the Japanese box office to become the highest-grossing film in Japanese history.[3] It won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards, the Golden Bear at the 2002 Berlin International Film Festival (tied with Bloody Sunday) and is among the top ten in the BFI list of the 50 films you should see by the age of 14.

Plot

Chihiro Ogino, a 10-year-old girl, moves with her parents to a new town when they become lost and find what appears to be an abandoned amusement park. Chihiro's father insists on exploring it, and she and her mother reluctantly accompany him. Chihiro's parents sample the food at an unattended stall. After Chihiro wanders off and finds a grand bathhouse, a boy approaches and warns her to leave before nightfall. When Chihiro runs back to her parents, she finds they have been transformed into pigs,[4] and the park starts to swarm with spirits.

She eventually learns from Haku, the boy she had met earlier, that her family has become trapped in the spirit world. He also reveals that he had known her since she was a child. Haku brings Chihiro to the bathhouse where he tells her to see Kamaji, a six-armed man who works the boiler room, to ask for a job. Rejecting Chihiro's request, Kamaji entrusts her to Lin,[5] a bathhouse worker. Lin takes her to see Yubaba, the witch who runs the bathhouse. Chihiro's request is rejected again, but Yubaba allows her to work on the condition that her name is changed to Sen (千), the first character of Chihiro's name. Having been told from Haku that Yubaba controls her servants by taking their names, Chihiro is warned that if she forgets her real name, she will be trapped in the world forever.

While working as Lin's assistant, Sen allows a mysterious masked spirit to enter. Later, a "stink spirit" enters the bathhouse. Sen eventually cleans the stink spirit, revealing himself to be a spirit of a polluted river. In return for restoring his health, the river spirit bestows upon Sen an emetic dumpling.

Sen eventually realizes Haku is actually a dragon. While still a dragon, Haku is seriously injured by shikigami in the form of paper birds. Yubaba decides that the injured Haku is no longer of any use to her and leaves her servants to kill Haku. Sen attempts to protect Haku, however, at which point, the shikigami are revealed to be controlled by the spirit of Zeniba, Yubaba's twin sister. Zeniba informs Sen that Haku stole her gold seal on Yubaba's orders and demands that the gold seal be returned. In the process, Zeniba transforms Boh, Yubaba's large baby son, into a mouse and Yubaba's bird into an insect. Yubaba's other servants are transformed to look like Boh. Haku and Sen manage to escape from Zeniba and fall into the boiler room again, where Sen feeds Haku part of the dumpling. Haku coughs up the gold seal and a black slug, which Sen crushes with her foot. Kamaji gives Sen train tickets to visit Zeniba so that she can beg her to lift the curse on the seal. Boh, in his mouse form, and the bird accompany her.

Meanwhile, the masked spirit that Sen allowed into the bathhouse reveals himself as a monster called "No Face (Kaonashi)." No Face, who swallows one of the servants, a frog, in order to speak, offers gold to the staff in exchange for large quantities of food. As No Face continues to eat, it grows in size. Its insatiable appetite causes it to swallow several other employees and it ultimately reaches immense proportions. Later, Sen feeds No Face the remainder of the dumpling, causing him to regurgitate everything and everyone it has eaten. Restored to his prior inoffensive form, No Face also accompanies Sen to Zeniba's house.

Haku regains consciousness and learns that Sen has gone to see Zeniba. Yubaba, enraged by both the damage caused by No Face and Sen's departure, orders Sen's parents to be killed. Haku appears and warns Yubaba that something precious to her has been replaced, and she realizes that Boh has disappeared. Telling her that Boh is with Zeniba, Haku proposes should he return Boh, Yubaba will allow Sen and her parents to return the human world. Yubaba agrees on the condition that Sen pass one final test.

Sen, Boh, and No Face arrive at Zeniba's house and find Zeniba to be friendly. Zeniba says Sen's love broke the seal's spell, and the slug Sen killed was the curse Yubaba had used to enslave Haku. Haku appears in his dragon form to pick up Sen and Boh, while No Face remains with Zeniba. Realizing that Sen once fell into the Kohaku River as a child, she guesses Haku is the spirit of the river who saved her, freeing Haku from Yubaba's spell.

Haku returns Boh to Yubaba, and Sen, now called Chihiro, is offered a final test to guess her parents from a group of pigs. She correctly answers that none of them are her parents. Haku leads her towards the entrance of the park and promises they will see each other again. Haku also tells Chihiro to not look back until she goes through the tunnel. Chihiro reunites with her parents, who do not recall their experiences, and the family departs from the park. It is implied that a period of time has passed and it is unclear whether or not time passed at the same rate.

Cast

- Rumi Hiiragi as Chihiro Ogino (荻野 千尋, Ogino Chihiro): An average fourteen-year-old girl. While in the process of moving with her family, Chihiro and her mother and father accidentally find a way into the spirit world where her parents had been transformed into pigs. In order for Chihiro and her parents' safe return to the human world, she becomes more brave and confident in herself. She is aided by the River Spirit Haku throughout the film and works at bath house um . The two eventually develop an innocent-romance. In the English version, Chihiro is voiced by Daveigh Chase.

- Mari Natsuki as Yubaba (湯婆婆, Yubaaba, lit. "bathhouse witch"): An elderly witch with an inhumanly large head and nose, who supervises the bathhouse. Yubaba has an over-bearing and authoritarian personality, but does show a soft side toward her giant baby, Boh. Yubaba lives in opulent quarters and is only interested in taking care of guests for money. Natsuki also voices Zeniba (銭婆, Zeniiba), Yubaba's twin sister. Although identical in appearance, their personalities are almost polar opposites. In the English version, Zeniba and Yubaba are voiced by Suzanne Pleshette.

- Miyu Irino as Haku/Spirit of the Kohaku River (ハク/饒速水琥珀主(ニギハヤミコハクヌシ), Haku/Nigihayami Kohakunushi, lit. "god of the swift amber river"):[6] A dragon in the guise of a human who helps Chihiro after her parents are transformed into cows. Haku works as Yubaba's direct subordinate, often running errands and performing various missions for her. He has the ability to fly in his true form, which is a dragon. It is somewhat implied Haku has feelings for Chihiro throughout the film, as he shows his loving care to protect her in numeral scenes. In the English version, Haku is voiced by Jason Marsden.

- Yumi Tamai as Lin (リン, Rin): A worker at the bathhouse who becomes Chihiro's caretaker. Lin is a transformed spirit of a Sable (weasel).[5] In the English version, Lin is voiced by Susan Egan.

- Bunta Sugawara as Kamajii (釜爺, lit. "boiler geezer"): An old, six-armed man who operates the boiler room of the bathhouse. His extra arms can apparently extend indefinitely to allow him access to the upper cabinets from his original position. A number of Susuwatari (ススワタリ, lit. "travelling soot", soot sprites) work for him by carrying coal into his furnace. In the English version, Kamajii is voiced by David Ogden Stiers.

- Yasuko Sawaguchi as Yuko Ogino (荻野 悠子, Ogino Yūko): Chihiro's mother. In the English version, Yuko is voiced by Lauren Holly.

- Takashi Naito as Akio Ogino (荻野 明夫, Ogino Akio): Chihiro's father. In the English version, Akio is voiced by Michael Chiklis.

- Takehiko Ono as Aniyaku: The assistant manager of the bathhouse. In the English version, Aogaeru is voiced by John Ratzenberger.

- Ryunosuke Kamiki as Boh (坊, Bō): Yubaba's son and Zeniba's nephew. Although he has the appearance of a young baby, he is twice Yubaba's size. He is also very strong and can be dangerous. Yubaba goes out of her way to give him whatever he wants. In the English version, Boh is voiced by Tara Strong.

- Akio Nakamura as No-Face (カオナシ, Kaonashi, lit. "faceless"): An odd spirit who takes an interest in Chihiro Ogino. At first, he appears to be a strange, demure, cloaked, masked wraith who seems mute other than his breathing and urging grunts. Seen as polite, calm, and quiet at first, No-Face is a lonely being who seems to sustain itself on the emotions of those he encounters, particularly their emotional reception to his gifts. In the English version, No-Face is voiced by Bob Bergen. Bergen also provided the voice for Bandai-gaeru, a frog worker who was swallowed by No-Face. Bandai-gaeru is voiced by Yo Oizumi in Japanese.

Themes and archetypes

The major themes of Spirited Away center on the protagonist Chihiro and her liminal journey through the realm of the bathhouse of spirits. A child forced into the fantastic world, Chihiro becomes completely separated from everything she has known and must find her way back to reality. Chihiro's experience in the alternate world, frequently compared to Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, represents her passage from childhood to adulthood.[7] The archetypal entrance into another world clearly demarcates Chihiro's status as one in-between. In her transition between child and adult, Chihiro stands outside these societal boundaries, a situation mirrored by the supernatural setting outside reality. The use of the word kamikakushi (literally "hidden by gods") within the Japanese title, and its associated folklore, reinforce this liminal passage: "Kamikakushi is a verdict of 'social death' in this world, and coming back to this world from Kamikakushi meant 'social resurrection.'"[8] Yubaba had many similarities to The Coachman from Pinocchio, in the sense that she transformed humans into pigs in a similar way that the boys from Pleasure Island were transformed into donkeys. Upon gaining employment at the bathhouse, Yubaba's seizure of Chihiro's true name, a common theme in folklore, symbolically kills the child Chihiro.[7] Having lost her childhood identity, Chihiro cannot return to reality by the way she came and can only move forward into adulthood. The following trials and obstacles Chihiro must overcome become the challenges and lessons common in rites-of-passage and the monomyth format. In her attempt to regain her self, her "continuity with her past," Chihiro must create a new identity.[7]

Beneath the surface coming of age theme, Spirited Away contains critical commentary on modern Japanese society concerning generational conflicts, the struggle with dissolving traditional culture and customs within a global society, and environmental pollution.[9] Chihiro, as a representation of the liminal shōjo, "may be seen as a metaphor for the Japanese society which, over the last decade, seems to be increasingly in limbo, drifting uneasily away from the values and ideological framework of the immediate postwar era."[10] Just as Chihiro seeks her past identity, Japan, in its anxiety over the economic downturn occurring during the release of Spirited Away in 2001, sought to reconnect to past values.[7] In interview, Miyazaki has commented on this nostalgic element for an old Japan.[11] Initially, Chihiro travels past the abandoned fairground, a symbol for Japan's burst "bubble economy", and her parents' credit-card-fuelled gluttony and transformation into pigs, to reach the fantasy world replete with Japanese culture and fable in the amalgam of the bathhouse.

However, the "bathhouse of the spirits has its own ambivalence, and its own darkness.... Miyazaki is not so simple-minded as to locate a perfect vision in the past or the spiritual."[12] Many of the employees are rude and discriminating to Chihiro, and the corruption of avarice has incorporated itself into the "bricolage" of the bathhouse[10] and as a place of "excess and greed" as depicted in the initial appearance of the No-Face.[13] In stark contrast to the "archetypal approaches to cultural recovery such as recognition, proper identification, spiritual cleansing and sacrifice," embodied in Chihiro's journey and transformation, the constant background presence of the ambiguity of the bathhouse reminds the audience reality is not so simple: "the bathhouse's simultaneous incorporation of the carnivalesque and the chaotic suggests the threats to the collectivity are not simply outside ones."[10] The environmental asides concerning the trash deforming the River God and Haku's plight over the loss of his river to apartment complexes further indicate the sources of pollution within the bathhouse, a place of ritual purity, come from within the Japanese society.

Production

| I created a heroine who is an ordinary girl, someone with whom the audience can sympathize. It's not a story in which the characters grow up, but a story in which they draw on something already inside them, brought out by the particular circumstances. I want my young friends to live like that, and I think they, too, have such a wish. |

| — Hayao Miyazaki[14] |

Every summer, Hayao Miyazaki spent his vacation at a mountain cabin with his family and five girls who were friends of the family. The idea for Spirited Away came about when he desired to make a film for these friends. Miyazaki had previously directed films like My Neighbor Totoro and Kiki's Delivery Service, which were for small children and teenagers, but he had not created a film for ten-year-old girls. For inspiration, he read shōjo manga magazines like Nakayoshi and Ribon the girls had left at the cabin, but felt they only offered subjects on "crushes" and romance. When looking at his young friends, Miyazaki felt this was not what they "held dear in their hearts." Instead, he decided to make the film about a girl heroine whom they could look up to.[14]

Miyazaki had wanted to make a new film for a long time. He had previously written two project proposals, but they had both been rejected. The first one was based on the Japanese book Kirino Mukouno Fushigina Machi, and the second one was about a teenage heroine. Miyazaki's third proposal, which ended up becoming Sen and Chihiro Spirited Away, was more successful. All three stories revolved around a bathhouse that was based on a bathhouse in Miyazaki's hometown. Miyazaki thought the bathhouse was a mysterious place, and there was a small door next to one of the bathtubs in the bathhouse. Miyazaki was always curious to what was behind it, and he made up several stories about it; one of which was the inspiration for the bathhouse in Spirited Away.[14]

Production of the film commenced in 2000 on a ¥1.9 billion (US$19 million) budget. As with Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki and his staff had experimented with the process of computer animation. Equipping themselves with more computers and programs like Softimage, the Studio Ghibli staff began to learn the software, but kept the technology at a level to enhance the story, not to "steal the show." Each character were largely animated by hand, with Miyazaki working alongside his animators to see they were getting it just right.[15] The biggest difficulty in making the film was to cut down its length. When production started, Miyazaki realized it would be more than three hours long if he made it according to his plot. He had to cut many scenes from the story, and tried to reduce the "eye-candy" in the film because he wanted it to be simple. Miyazaki did not want to make the hero a "pretty girl." At the beginning, he was frustrated at how she looked "dull" and thought, "She isn't cute. Isn't there something we can do?" As the film neared the end, however, he was relieved to feel "she will be a charming woman."[14]

Miyazaki based some of the buildings in the spirit world on the buildings in the Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum in Koganei, Tokyo, Japan. He often visited the museum for inspiration while working on the film. Miyazaki had always been interested in the Pseudo-Western style buildings from the Meiji period that were available there. The museum made Miyazaki feel nostalgic, "especially when I stand here alone in the evening, near closing time, and the sun is setting – tears well up in my eyes."[14] Another major inspiration was the Notoyaryokan, a Ryokan located in Yamagata Prefecture, notorious for its exquisite architecture and ornamental features.[16]

English adaptation

Pixar Animation Studios dubbed the English adaptation of Spirited Away, under the supervision of John Lasseter. Lasseter is a "huge" Miyazaki fan, and he and his staff often sit down and watch some of Miyazaki's work when they encounter story problems. The first viewing of Spirited Away in the United States was in Pixar's screening room. After seeing the film, Lasseter was "ecstatic." Upon hearing his reaction to the film, people at Disney asked Lasseter if he would be interested in trying to bring Spirited Away to an American audience. Lasseter said he had a busy schedule, but agreed to executive produce the English adaptation. Soon, several others began to join the project: Beauty and the Beast co-director Kirk Wise and Aladdin producer Donald W. Ernst soon joined Lasseter as director and producer of Spirited Away respectively.[17]

The cast of the film consisted of Daveigh Chase, Susan Egan, David Ogden Stiers and John Ratzenberger (considered by Lasseter as his "good luck charm"). With the cast and talent in place, word began to spread around the Internet. But at first, news was light. Pixar had already begun to push their upcoming fall films, but the only trace Spirited Away was coming was in a small scrolling section of their film page on Disney.com. The promotions were also quite trying, as Disney had sidelined their homepage for Spirited Away and hidden it in the confines of Buena Vista's many 'labyrinths'. While homepages for films like Signs were clearly displayed, it was only through some people's curiosity the Spirited Away homepage could be found.[17]

Release

Critical reception

Ever since its original 2001 release, Spirited Away has received overwhelmingly positive reviews. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 4 out of 4 stars and praised the film and Miyazaki's direction. Ebert also said that Spirited Away was one of "the year's best films."[18] Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times positively reviewed the film and praised the animation sequences. Mitchell also drew a favorable comparison to Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass and also said that his movies are about "moodiness as mood" and the characters "heightens the [film's] tension."[2] Derek Elley of Variety said that Spirited Away "can be enjoyed by sprigs and adults alike" and praised the animation and music.[1] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times praised the voice acting and said the film is the "product of a fierce and fearless imagination whose creations are unlike any[thing a person has] seen before". Turan also praised Miyazaki's direction.[19] Orlando Sentinel's critic Jay Boyar also praised Miyazaki's direction and said the film is "the perfect choice for a child who has moved into a new home."[20]

97% of the 155 reviewers selected by Rotten Tomatoes as of January 2012 have given the film positive reviews, certifying it "Fresh" with an average rating of 8.5/10, and ranks as the thirteenth-best animated film on the site.[21][22] In 2005, it was ranked as the twelfth-best animated film of all time by IGN.[23] The film is also ranked #9 of the highest-rated movies of all time on Metacritic; being the highest rated traditionally animated film on the site. The film ranked #10 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[24]

Box office

Spirited Away opened theatrically in Japan on July 27, 2001 by Japanese film distributor Toho, grossing US$229,607,878 to become the highest-grossing film in Japanese history.[25] It was the first film to have earned $200 million at the worldwide box office before opening in the United States.[26]

The film was dubbed into English by Walt Disney Pictures, under the supervision of Pixar's John Lasseter. The dubbed version premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 7, 2002[27] and was subsequently released in North America on September 20, 2002. The film grossed $449,839 in its opening weekend and had made slightly over $10 million by September 2003.[28] The film went on to gross US$274,925,095 worldwide.[29]

Home media

The film was released in North America by Disney's Buena Vista Distribution arm on DVD and VHS formats on April 15, 2003 where the attention brought by the Oscar win made the title a strong seller.[30] Spirited Away is often marketed, sold and associated with other Miyazaki films such as Castle in the Sky, Kiki's Delivery Service and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

The North American English-dubbed version was released on DVD in the UK on March 29, 2004. In 2005, it was re-released by Optimum Releasing with a more accurate subtitle track and additional bonus features.[citation needed]

The back of the Region 1 DVD from Disney and the Region 4 DVD from Madman states that the aspect ratio is the original ratio of 2.00:1. This is incorrect; the ratio is actually 1.85:1 but has been windowboxed to 2.00:1 to compensate for the overscan on most television sets. There is much dispute over the validity of this practice, as many displays are capable of showing the entire picture, and as a result the DVD picture has a noticeable border around it.

The Asian releases of the DVD, including Japan and Hong Kong, have a noticeably accentuated amount of red in their picture transfer. This is another case of compensating for home theatre displays, this time supposedly for LCD television which, it was claimed, had a diminished red colour in its display. Releases in other DVD regions such as the U.S., Europe and Australia use a picture transfer where this "red tint" has been significantly reduced.

Soundtrack

The closing song, "Always With Me" (いつも何度でも, Itsumo Nandodemo, literally, "Always, No Matter How Many Times") was written and performed by Youmi Kimura, a composer and lyre-player from Osaka. The lyrics were written by Kimura's friend Wakako Kaku. The song was intended to be used for Rin the Chimney Painter (煙突描きのリン, Entotsu-kaki no Rin), a different Miyazaki film which was never released. In the special features of the DVD, Hayao Miyazaki explains how the song in fact inspired him to create Spirited Away.

The film score was composed and conducted by Joe Hisaishi, and performed by the New Japan Philharmonic. His "Day of the River" (あの日の川, Ano hi no Kawa) piece received the 56th Mainichi Film Competition Award for Best Music, the Tokyo International Anime Fair 2001 Best Music Award in the Theater Movie category, and the 16th Japan Gold Disk Award for Animation Album of the Year. Later, Hisaishi added lyrics to "Day of the River" and named the new version "The Name of Life" (いのちの名前, "Inochi no Namae") which was performed by Ayaka Hirahara.

Besides the original soundtrack, there is also an image album, which contains ten tracks.

| Track | Composer | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | One Summer's Day (あの夏へ, Ano Natsu e) | Joe Hisaishi (久石譲) | 3:09 |

| 2 | A Road to Somewhere (とおり道, Toori Michi) | 2:07 | |

| 3 | The Empty Restaurant (誰もいない料理店, Dare mo Inai Ryōriten) | 3:15 | |

| 4 | Nighttime Coming (夜来る, Yoru Kuru) | 2:00 | |

| 5 | The Dragon Boy (竜の少年, Ryū no Shōnen) | 2:12 | |

| 6 | Sootballs (ボイラー虫, Boirā Mushi) | 2:33 | |

| 7 | Procession of the Spirits (神さま達, Kamisama-tachi) | 3:00 | |

| 8 | Yubaba (湯婆婆) | 3:30 | |

| 9 | Bathhouse Morning (湯屋の朝, Yuya no Asa) | 2:02 | |

| 10 | Day of the River (あの日の川, Ano Hi no Kawa) | 3:13 | |

| 11 | It's Hard Work (仕事はつらいぜ, Shigoto wa Tsuraize) | 2:26 | |

| 12 | The Stink Spirit (おクサレ神, Okusaregami) | 4:01 | |

| 13 | Sen's Courage (千の勇気, Sen no Yūki) | 2:45 | |

| 14 | The Bottomless Pit (底なし穴, Sokonashi Ana) | 1:18 | |

| 15 | Kaonashi (No Face) (カオナシ, Kaonashi) | 3:47 | |

| 16 | The Sixth Station (6番目の駅, Roku Banme no Eki) | 3:38 | |

| 17 | Yubaba's Panic (湯婆婆狂乱, Yubaba Kyōran) | 1:38 | |

| 18 | The House at Swamp Bottom (沼の底の家, Numa no Soko no Ie) | 1:29 | |

| 19 | Reprise (ふたたび, Futatabi) | 4:53 | |

| 20 | The Return (帰る日, Kaeru Hi) | 3:20 | |

| 21 | Always With Me (いつも何度でも, Itsumo Nando demo) | Youmi Kimura (木村弓) | 3:35 |

- Image album track listing

- Ano Hi no Kawa e (あの日の川へ, lit. To that Days' River) – Umi (3:54)

- Yoru ga Kuru (夜が来る, lit. Night is Coming) – Joe Hisaishi (4:25)

- Kamigami-sama (神々さま, lit. Gods) – Shizuru Otaka (3:55)

- Yuya (油屋, lit. Bathhouse) – Tsunehiko Kamijō (3:56)

- Fushigi no Kuni no Jyūnin (不思議の国の住人, lit. The People in Wonderland) – Joe Hisaishi (3:20)

- Samishii samishii (さみしいさみしい, lit. Lonely lonely) – Monsieur Kamayatsu (3:41)

- Solitude (ソリチュード, Sorichūdo) – Rieko Suzuki and Hiroshi Kondo (3:49)

- Umi (海, lit. The Sea) – Joe Hisaishi (3:22)

- Shiroi Ryū (白い竜, lit. White Dragon) – Rikki (3:33)

- Chihiro no Waltz (千尋のワルツ, Chihiro no Warutsu, Chihiro's Waltz) – Joe Hisaishi (3:20)

References

- ^ a b Elley, Derek (February 18, 2002). "Sprited Away Review". Variety. Reed Business Information. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Elvis (September 20, 2002). "Movie Review - Spirited Away". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ Johnson, G. Allen. "Spirited away top grossing film in Japan". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ^ Clements, Jonathan (2006). The Anime Encyclopedia. California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-933330-10-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hayao Miyazaki (2008). The Art of Miyazaki's Spirited Away. Studio Ghibli Library. Viz Media. p. 120. ISBN 1569317771.

- ^ Haku is described as 'approximately 12', Hayao Miyazaki (2008). The Art of Miyazaki's Spirited Away. Studio Ghibli Library. Viz Media. p. 84. ISBN 1569317771.

- ^ a b c d Satoshi, Ando. "Regaining Continuity with the Past: Spirited Away and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland." Bookbird 46.1: 23–29. Project MUSE. 11 Feb. 2009 [1].

- ^ Reider, Noriko T. "Spirited Away: Film of the Fantastic and Evolving Japanese Folk Symbols." Film Criticism 29.3: 4–27. Academic OneFile. Gale. 11 Feb. 2009 [2].

- ^ Napier, Susan J. "Matter Out of Place: Carnival, Containment and Cultural Recovery in Miyazaki's Spirited Away." Journal of Japanese Studies 32.2: 287–310. Project MUSE. 11 Feb. 2009 [3].

- ^ a b c Napier, Susan J. "Matter Out of Place: Carnival, Containment and Cultural Recovery in Miyazaki's Spirited Away." Journal of Japanese Studies 32.2: 287–310. Project MUSE. 11 Feb. 2009 [4].

- ^ Mes, Tom (2002-01-07). "Hayao Miyazaki Interview". Midnight Eye. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ Thrupkaew, Noy. "Animation Sensation: Why Japan's Magical Spirited Away Plays Well Anywhere." American Prospect 13.19: 32–33. Academic OneFile. Gale. 11 Feb. 2009 [5].

- ^ Harris, Timothy. "Seized by the Gods." Quadrant 47.9: 64–67. Academic OneFile. Gale. 11 Feb. 2009 [6].

- ^ a b c d e Miyazaki on Spirited Away // Interviews //. Nausicaa.net (2001-07-11). Retrieved on 2011-05-25.

- ^ The Making of Hayao Miyazaki's "Spirited Away" – Part 1. Jimhillmedia.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-25.

- ^ http://www.tenkai-japan.com/2010/05/29/notoya-in-ginzan-onsen-stop-businees-for-renovation/

- ^ a b The Making of Hayao Miyazaki's "Spirited Away" – Part 3. Jimhillmedia.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-25.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 20, 2002). "Spirited Away". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (September 20, 2002). "Under the Spell of 'Spirited Away'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ Boyar, Jay (October 11, 2002). "`Spirited Away' -- A Magic Carpet Ride". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ "Best Animated Films – Spirited Away". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "Spirited Away Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ "The Top 25 Animated Movies of All-Time". IGN Entertainment. News Corporation. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". Empire.

{{cite web}}: Text "10. Spirited Away" ignored (help) - ^ "Spirited Away - International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ Johnson, G. Allen (February 3, 2005). "Asian films are grossing millions. Here, they're either remade, held hostage or released with little fanfare". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Ball, Ryan (9 September 2001). "Spirited Away Premieres At Toronto Int'l Film Fest". Animation Magazine. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Spirited Away Box Office and Rental History". Archived from the original on 2006-01-16. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ "Spirited Away (2002)". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com accessdate = December 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Missing pipe in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Reid, Calvin (April 28, 2003). "'Spirited Away' Sells like Magic". Publisher's Weekly.

External links

{{{inline}}}

- Official website

- Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi at IMDb

- Spirited Away at the TCM Movie Database

- Spirited Away at AllMovie

- Template:Bcdb title

- Spirited Away (anime) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- Spirited Away at Box Office Mojo

- Spirited Away at Metacritic

- Spirited Away at Rotten Tomatoes

- Spirited Away at the Japanese Movie Database Template:Ja icon

- Animerica review

- 2001 films

- Japanese films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Hayao Miyazaki

- Animated features released by GKIDS

- Studio Ghibli

- Animated features released by Toho

- Anime films

- Anime of 2001

- Anime with original screenplays

- Annie Award winners

- Best Animated Feature Academy Award winners

- Children's fantasy films

- Coming-of-age films

- Fantasy adventure films

- Fantasy anime and manga

- Japanese mythology in anime and manga

- Golden Bear winners

- Animated features released by Studio Ghibli

- Films distributed by Disney