Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

October 26

Evolution of horse - back strength/suitability for riding

Why has the horse evolved to be able to carry the weight of a human on its back? Why do they even tolerate riding?--2.97.23.83 (talk) 08:02, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- It would be more accurate to say that horses have been bred for the purpose of humans riding them, and so have been artificially, not naturally selected. Furthermore, this development did not take place in a geological timescale, but over the span of only a few thousand years. Before maybe 1500 BC, horses were used mainly to draw chariots, because they weren't big enough to ride. The situation is similar to modern cattle providing huge quantities of milk, far more than wild cattle. This is not due to evolution, but due to human/artificial selection. - Lindert (talk) 10:09, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- Are you sure about the size part? The Hagerman horse is about the size of an Arabian horse, and it dates from 3.5 million years ago. --140.180.252.244 (talk) 10:50, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- Do you have a source on horses not being large enough to ride before their domestication? Our article on evolution of the horse seems to indicate otherwise. Undomesticated horses like the Przewalski's horse appear large enough to support a human rider. A8875 (talk) 10:51, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- I'm not saying that no horses existed that were big enough, just the horses that were used by humans early on were small, and then bred larger. Maybe large horses did not live in the area (ancient near east) where they were first domesticated. - Lindert (talk) 11:13, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- I recons it was purely coincidental at first, and then there developed an evolutionary correlation. Plasmic Physics (talk) 11:03, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- We have an article, Domestication of the horse. With reference to the points raised above, it seems that (according to our article) "recent genetic studies indicate that Przewalski's horse is not an ancestor to modern domesticated horses". Also, one of the first domestications seems to have been by "theBotai culture... who seem to have adopted horseback riding in order to hunt the abundant wild horses of northern Kazakhstan between 3500-3000 BCE" although it's not certain that they didn't just hunt them. Finally, "Horse bones from these contexts (recovered from the middens of various European bronze age sites) exhibited an increase in variability, thought to reflect the survival under human care of both larger and smaller individuals than appeared in the wild; and a decrease in average size, thought to reflect penning and restriction in diet." Alansplodge (talk) 15:17, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- It's worth noting in terms of the behavior that in some respects humans just lucked out. Zebras, for example, have never been domesticated to the same degree as the horse, despite a lot of trying. There seems to be something fundamentally incompatible with their natural makeup to easy domestication, as there is for a lot of animals. --Mr.98 (talk) 22:14, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- For some pictures of domesticated zebras, see Zebra taxi cab in Brixton Road!;-) Alansplodge (talk) 16:57, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

Chemical castration for woman

Are there any chemical castration procedures for female sex offenders? A8875 (talk) 09:36, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- Androgens may contribute to aggression in women (data are conflicting), and one could speculate about whether they would be effective, but I'm not aware of any such procedures. Estrogens do not clearly contribute to aggressive behavior, so I would not expect an analogous procedure for female hormones. Of interest (not all directly related): PMID 22415579, PMID 20951723, PMID 19747510 -- Scray (talk) 10:41, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- This page has some interesting information: "Even though sexual victimization by either males or females is a traumatizing experience, female offenders are overall not as dangerous as males, and combine the act with fewer aggravating circumstances such as weapon possession, kidnapping, or violence. Perhaps because of this, more cases of female sex offending go unreported." It also states that less than 4% of sex crimes in the U.S. are committed by females, and notes that sex crimes by females tend to be less likely to be repetitive or compulsive than males. It does not directly answer the question on whether chemical castration is possible, nor does it answer whether it is desirable, but it does make the case that sexual crimes committed by females are distinct from those committed by males, and thus may indicate that a different response to them is necessary. Just some related ideas. Doing some searching, I can't find any reliable sources on "chemical castration of women", but several rather unreliable discussions found through searching google with that phrase seem to indicate there is a sense that either it is never done, or even that it isn't possible to do so. --Jayron32 13:26, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- Female sexual criminals are not your typical sexual predator or compulsive rapist. There are much more a women having consensual sex with men below the age of consent (so, it's not legally consensual) or women being dragged into some sexual slavery scheme by partners. OsmanRF34 (talk) 16:58, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- Is this your impression, or do you have references to support your "answer"? -- Scray (talk) 17:13, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- It's a small sample, but the criminal statistics for Sweden in 2011 kind of supports that. Of 18 women sentenced for sex crimes 1 committed rape, and out of 1380 men sentenced for sex crimes 151 committed rape and 16 aggravated rape (statutory rape not included in rape or aggravated rape) (sourceBRÅ, Brottsförebyggande rådet). That's 6 % of female sex offenders and 12 % of male sentenced for rape. I'm sure there are similar statistics for other countries.Sjö (talk) 15:41, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- I think it's too small a sample. A quick mental calculation gives huge error bars on the rate of female rapists -- that "6%" is actually something like "0%-14%". --Carnildo (talk) 02:16, 30 October 2012 (UTC)

- It's a small sample, but the criminal statistics for Sweden in 2011 kind of supports that. Of 18 women sentenced for sex crimes 1 committed rape, and out of 1380 men sentenced for sex crimes 151 committed rape and 16 aggravated rape (statutory rape not included in rape or aggravated rape) (sourceBRÅ, Brottsförebyggande rådet). That's 6 % of female sex offenders and 12 % of male sentenced for rape. I'm sure there are similar statistics for other countries.Sjö (talk) 15:41, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Is this your impression, or do you have references to support your "answer"? -- Scray (talk) 17:13, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

There are drugs that suppress sex hormones in women as well as men. Examples are gonadotropin releasing hormone analogs such as leuprolide and histrelin. They are used to suppress sex hormones for many purposes, but not to treat female sex offenders for many reasons. As mentioned above: there are very few of them, and nearly all have engaged in consensual sex with adolescents or have been willing participants in abuse of younger children under the direction of a male; an even smaller percentage repeatedly offend. Most importantly there is no evidence that hormones play a role in compulsive sexualized behavior that testosterone seems to in men. alteripse (talk) 19:56, 31 October 2012 (UTC)

Privacy

Can you read my I.P. address?Cinquefoil (talk) 11:35, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- No, I can't. Because you have a registered account, your ip address is private from most other users. A few selected people with checkuser privileges can choose to see your ip address, but they wouldn't be likely to bother unless you were disrupting the project in some way.-FisherQueen (talk · contribs)11:37, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- It's actually more than "they won't bother": Checkusers use of the Checkuser tool is carefully monitored and logged, and checkusers that misuse it can be stripped of it. So, unless you have actually done something to attract the attention of the Checkusers, no one will see your IP address. Checkusers have to have a justifiable reason to use the tool, and if they don't, there's some 'splainin' to do. --Jayron32 13:15, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- There are a lot of ways to "social engineer" it. Like, if I have a site that will tell me the IP addresses of people who look at a picture (or an invisible "web bug") and I send it to Special:Emailuser/Cinquefoil, then if you open it, I know what your IP is (and stuff about your browser too, probably) Or I could post similar links to some kind of text answers to two questions you ask, see if there's an IP address in common. The whole web is run by amateur spies on the brink of turning pro, I think. Wnt (talk) 21:06, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- It's actually more than "they won't bother": Checkusers use of the Checkuser tool is carefully monitored and logged, and checkusers that misuse it can be stripped of it. So, unless you have actually done something to attract the attention of the Checkusers, no one will see your IP address. Checkusers have to have a justifiable reason to use the tool, and if they don't, there's some 'splainin' to do. --Jayron32 13:15, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

The surface of Saturn

This question was prompted by [1] - stories which get it wrong; the vortex is 150 F hotter, not 150 F! Still, according to the article, Saturn gets extremely hot, 11,700 C shining-like-the-sunhot, if you go down far enough.

- How much is known about the temperature profile and cloud composition of Saturn's atmosphere? In particular, is it like Jupiter's atmosphere, where there is a "sweet spot" with Earthlike temperatures and pressures if you go to the right depth? (Note Saturn also has Earth gravity, making it a rather good opportunity for a sci-fi vacation, I think. If only you can figure out how to breathe and how not to fall, that is.)

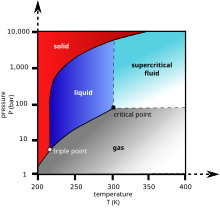

- What does our article mean when it says that Saturn has a "liquid layer of helium-saturated molecular hydrogen that gradually transitions into gas with increasing altitude" (around 1000 km). I'm aware of the critical point where gas and liquid are the same, but I thought either you were above the critical point and there was no difference, or you were below it and there were two very distinct phases.

- Saturn is made up mostly of liquid hydrogen that is less dense than water. So why don't all the other heavier elements sink and leave no trace in the atmosphere? Or is the liquid hydrogen mixed in with a fairly large amount of such impurities?

- Is there anything that might be found floating on the "surface", if it exists, or which could distinguish a "cartography" of different physical areas?

- 1000 km might show up on Earth, but relative to Saturn, it's a very thin skin, practically two-dimensional. Do these things like the Great Springtime Storm exist as very wide but not deep features, like hurricanes on Earth, or do they whip up vortices (or something) in the liquid? hydrogen layer?

Some previous discussion, not very satisfying, at[2]. Wnt (talk) 21:31, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- It's unlikely that there is such a "sweet spot", the temperature would probably be below freezing even at greater than 100 kPa atmospheric pressure.

- I hope that you're aware that gravity is a function of height, and not a constant. So, it does not make sense to describe Saturn's gravity without making a reference to a height.

- I don't understand what you don't understand, concerning the critical point. A trasition through the critical point occurs with increasing depth just as you say.

- Because of this transition, there is no surface, so nothing can be floating on a surface. Plasmic Physics (talk) 13:09, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- It doesn't matter much if it's a few times atmospheric pressure - can you be more specific?

- The article says that for temperatures between 270 K and 330 K, the pressure is 1-2 MPa. That's more than ten times atmospheric pressure, and it happens to be the exact zone where hydrogen transitions from a gas to a supercritical gas-liquid state. Helium transitions ways before that even. Plasmic Physics (talk) 02:30, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Gravity in the article is in reference to the 1 bar level; anywhere in the atmosphere should be very similar.

- Critical point (thermodynamics) does indeed show dotted lines at the critical temperature and pressure. I suppose it is the critical pressure that is exceeded in this case at 1000 km? But that transition isn't "gradual" - it's just an imaginary line between "gas" and "supercritical fluid", I suppose? But that should not be visible, and it makes no special sense to call it liquid hydrogen beneath it, right? Wnt (talk) 01:44, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- A supercritical state can only be achieved when both the critical pressure and temperature have been exceeded. It should really be called supercritical helium/hydrogen. The transition from gas to a supercritical state is not gradual but sharp and well-defined, because of the pressure and temperature boundries. It is the transition of observational properties that is gradual. Plasmic Physics (talk) 02:17, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Indeed, I see now that hydrogen has a critical point of 1.29 MPa, about 12 atm. Where this gets curious is that hydrogen has density 70 kg/m3 as a liquid, 30 kg/m3 at the critical point [3], whereas air near STP has density a little above 1 kg/m3 -if ordinary air respects the ideal gas law, then it should only be around 12 kg/m3 at this point. Now heating hydrogen should reduce its density, but will a supercritical fluid respect the ideal gas law? From the article I'm getting the impression that small differences in conditions alter its density considerably, so I'm thinking no. I almost wonder if there's a point where ordinary air (let alone heated hydrogen) might be buoyant within the supercritical hydrogen fluid? But I haven't really thought this through. Also, what's the solubility of water in supercritical hydrogen? I have this weird notion of jellyfish, with an inner food reservoir of stored oxygen gas, floating in the sea of supercritical hydrogen? Wnt (talk) 06:59, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Of course "ordinary air" is buoyant. Even so, it doesn't separate out from the supercritical fluid-gas, it mixes yielding ratios proportional to the depth. On earth, the different atmospheric gases (nitrogen, carbon dioxide, oxtgen, argon, etc.) have differing bouyancies. Brownian motion ensures that they don't separate out into layers, I think it is called a Maxwell-Boltzman distribution, we have a page on it. Plasmic Physics (talk) 07:58, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Well, if it's true - and I don't know it is - it would be very surprising to me to find some special set of temperature/pressure conditions where oxygen is lighter than hydrogen, and more so to find them in reality. The point is that a jellyfish, even a single celled ancestor that can remain suspended due to its small size, would be readily able to separate oxygen from the supercritical sea in which it lives, and store it in little vacuoles where it would no longer mix. I'd read about the notion of "gasbag" organisms on Jupiter before, but had the impression that authors were only thinking of hot hydrogen balloons, designs that life has never created and would seem hard pressed to evolve. Wnt (talk) 13:55, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Of course "ordinary air" is buoyant. Even so, it doesn't separate out from the supercritical fluid-gas, it mixes yielding ratios proportional to the depth. On earth, the different atmospheric gases (nitrogen, carbon dioxide, oxtgen, argon, etc.) have differing bouyancies. Brownian motion ensures that they don't separate out into layers, I think it is called a Maxwell-Boltzman distribution, we have a page on it. Plasmic Physics (talk) 07:58, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- If Saturn is anything like Jupiter, then complex life is going to have a tough time in the atmosphere of Saturn. Jupiter generates biotoxic levels of high-frequency EM radiation like UV and X-ray, caused by perpetual lighting, so bright you can read a book by them. Plasmic Physics(talk) 01:12, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- Sounds like photosynthesis is easier there than I was picturing. :) Really, I think life can resist such mutagenesis if it needs to. Deinococcus radiodurans and all that. Wnt (talk) 01:31, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- If Saturn is anything like Jupiter, then complex life is going to have a tough time in the atmosphere of Saturn. Jupiter generates biotoxic levels of high-frequency EM radiation like UV and X-ray, caused by perpetual lighting, so bright you can read a book by them. Plasmic Physics(talk) 01:12, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- Just remember that any trip to a gas giant will be an one way trip unless you have engines made of Unobtainium. The gravity well is huge[4] and the exponential mass ratio due to the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation does not make it easier to reach escape velocity.Gr8xoz (talk) 13:32, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- I'm a great fan of using nuclear isomers as a power storage, with induced gamma emission. ;) Wnt (talk) 01:44, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- What are you implying, if it's not gioing to be easy for a rocket to do the job, then you're supposing an inferior jet-engine can? Plasmic Physics (talk) 02:35, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- I was only suggesting a compact energy storage - how you turn that into thrust is another matter. Ion drive perhaps (after you've flown as high as possible) - I don't have any inspired suggestion there. Wnt (talk) 04:06, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- What are you implying, if it's not gioing to be easy for a rocket to do the job, then you're supposing an inferior jet-engine can? Plasmic Physics (talk) 02:35, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- In that case, I suggest inventing a slipspace-drive, and tunneling through spacetime. Plasmic Physics (talk) 06:33, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Talking about superciticality, did you know that Venus has an invisible, global ocean of supercritical carbon dioxide? You should be able to notice it as a perpetual fog in the distance. In closer, you should be able to notice a shimmering motion like a mirage, but more ordered, indicating a hydrodynamic flow.Plasmic Physics (talk) 08:22, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- This ocean is at least an average of 2.5 km deep, that is the supercritical/gas limit. That makes me wonder how fast the terminal velocity changes in that 2.5 km, does the density change noticably? Plasmic Physics (talk) 01:50, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- I added a question about the crux of this (and the part about buoyancy of oxygen above) at Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science#Does the ideal gas law apply to supercritical fluids? Wnt (talk) 04:32, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

Why don't my coffee grounds grow mold?

Does it depend on the roast? I use a very dark roast. I can forget about coffee grounds for a week or more and yet no mold grows on them! The other time I was taking over an apartment from someone else and I accidentally drank very old coffee. (I wondered why it was cold-- it was a machine that "stored" the brew in a holding tank, which I didn't know of-- I thought I was drinking fresh brew). It tasted fine. 71.207.151.227 (talk) 22:39, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- Well, the (almost) boiling temperature at which the coffee is made would sterilise it. If it's kept well sealed from the air after that, it should restrict growths of many kinds. HiLo48 (talk) 23:01, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- Coffee grounds are largely fiber and alkaloid toxins. Any sugar, fat and protein has been denatured or roasted out of them, Funguses aren't miracle workers--they require actual food. μηδείς (talk) 23:16, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- I don't really see why denatured protein wouldn't be a perfectly adequate food source for a fungus. Presumably they need to hydrolyze the protein components to get any nutritional value out of them anyway; If anything wouldn't you expect unfolded protein to be more accessible to proteases and various digestive enzymes? (+)H3N-Protein\Chemist-CO2(-) 00:12, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- A lack of moisture is a limiting factor. Mold can grow on coffee. Here are Guidelines for the Prevention of Mould Formation in Coffee.Smallman12q (talk) 01:17, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, wet, used coffee grounds left in the coffee filter in a coffee maker grew an impressive colony of mold, while I was on vacation. StuRat(talk) 02:28, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

how bright is the white dwarf

I don't know the luminosity of the white dwarf will be but I know white dwarf is a comparable size of earth. Is white dwarf going to be 100 times dimmer than solar luminosity, I can't find it anywhere on the internet. But formation and evolution of the solar system said white dwarf will start at 100 times brighter than get dimmer. I also confuse on do white dwarf shrink right away to earth sized diameter, or it will start to be a comparable size with low-mass stars than when white dwarf stars gets older it gets smaller, in other words fresh new white dwarf will be bigger, and full-wedge white dwarf will be smaller. How long will white dwarf last before becoming a black dwarf? 7 billion years? 10 billion years? or White dwarf will start at UV end of stellar spectrum and gradually skew to IR end of stellar spectrum and gradually works toward black dwarf.--69.226.43.174 (talk) 23:42, 26 October 2012 (UTC)

- White dwarf would be about 100*100=10,000 dimmer than the Sun if it had the same temperature and were the size of the Earth. However the majority of known white dwarfs are hotter than the Sun and therefore more luminous than 1/10,000. You can read more in the white dwarf article. Ruslik_Zero 12:11, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

Our article said this surface temperature range corresponds to a luminosity from over 100 times the Sun's to under 1/10,000 that of the Sun's I don't get how white dwarf can be at first 100 times brighter than sun, I know white dwarf will have to star from UV end of the spectrum and gradually work way to IR end of spectrum. Does white dwarf have to be immediately the size of Earth, or it will be bigger at the start and then gradually become smaller.--69.226.43.174 (talk) 20:41, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Well the brightness is the fourth power of the temperature. So if a whitedwarf is 5 times hotter than the sun, it would be 5x5x5x5 times as bright or 625 times. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 21:56, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

October 27

Survive on alcohol

Can you survive longer if you have nothing else to drink except alcohol? Comploose (talk) 11:58, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Survive longer than what? What kind of alcohol? It's possible that, say, in the absence of a water source, you would survive much longer drinking beer than drinking nothing, for example (beer is a source of water and calories and is not as dehydrating as most people believe). But if you're asking whether substituting all of your water with ethanol is going to make you live longer, the contrary is certainly the case. --Mr.98 (talk) 12:34, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Penny, behind the bar: "What can I get ya?"

- Sheldon: "Alcohol."

- Penny: "Can you be more ... specific?"

- Sheldon: :"Ethyl alcohol."

- --Trovatore (talk) 23:00, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- A very logical answer, considering how much less desirable methyl alcohol is as a beverage. :-) StuRat (talk) 23:15, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, if you have just alcoholic beverages (vodka, wine, whiskey) at hand, would you survive longer drinking some of it or not drinking anything.Comploose (talk) 12:49, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- I think there must bee some limit between bear and 100 % alcohol above wich it is beter to drink nothing, but i do not know what that limit is.Gr8xoz (talk) 13:04, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Before sanitation, people drank beer in Northern Europe and diluted wine in Southern Europe instead of water, which carried diseases. You can survive on those as your beverage indefinitely. Anything much stronger than beer will dehydrate you. μηδείς (talk) 19:41, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Although (in England) they often used to drink small beer which had a very low alcohol content. "Some workers (including sailors) who engaged in heavy physical labour drank more than 10 Imperial pints (5.7 litres) of small beer during a workday to maintain their hydration level. This was usually provided free as part of their working conditions, it being recognised that maintaining hydration was essential for optimal performance."Alansplodge (talk) 18:00, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- This is often said, but the supposed mechanism is that it makes you urinate more. I seriously doubt that happens if you're close to the level of water you need to survive. If your choices are, drink nothing, or drink wine, I'd be very surprised if the answer isn't "drink wine". --Trovatore(talk) 23:03, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Before sanitation, people drank beer in Northern Europe and diluted wine in Southern Europe instead of water, which carried diseases. You can survive on those as your beverage indefinitely. Anything much stronger than beer will dehydrate you. μηδείς (talk) 19:41, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- In addition to the concentration of alcohol in the alcoholic beverage, the quantity would also matter. Even with beer, guzzling too much could lead to vomiting and other medical problems which would shorten your life. Sipping it, on the other hand, should sustain your life indefinitely (until you die of malnutrition after many years, at least). I wonder what form of malnutrition would eventually get you. Perhaps rabbit death, due to a lack of fat (although that article says that carbs prevent it, and beer has carbs) ? Also note that some alcoholics do, indeed, have a diet of exclusively alcoholic beverages. StuRat (talk) 23:18, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- I don't question your own experience, Stu, but in decades of consuming beer and wine, I don't recall it ever causing me to vomit. Edison(talk) 01:21, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- I notice people's tendency to vomit varies greatly. I vomit easily, so have never suffered a hangover, and the later effects of food poisoning are minimized. Sure, it's unpleasant, but better to get the poison out of you than leave it in. StuRat (talk) 01:44, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Oh dear! See Lightweight ;-) Alansplodge (talk) 18:05, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- I like to think that my body is smarter than I am. When I try to ingest poison, it gets rid of it in the most expeditious manner possible. StuRat (talk) 18:10, 31 October 2012 (UTC)

Global remaining Iron and aluminum ore resources

In wind power critical reader comments to articles about wind power in a Swedish magazine I have seen statements that we only have about 10 tones of iron left per person to mine.

Is that really realistic? How about aluminum?

Obviously there are a lot more iron and aluminum in the accessible part of the earths crust since 5% and 8% of the crust is iron and aluminum respectively.

Therefore the real question is how much remaining resources do we have that can be refined to metal to a cost less than let say twice the current production cost?

As I understand it is there much biased information circulating when it comes to estimates of available natural resources. Is there any reliable estimates? Gr8xoz (talk) 12:57, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Sounds like invented stuff. Comploose (talk) 13:02, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- USGS figures for 2012

- Iron - "World resources are estimated to exceed 230 billion tons of iron contained within greater than 800 billion tons of crude ore."[5]

- Aluminum - not sure [6] but you might find further details at the USGS' site. Or try the BGS' World mineral statistics Sean.hoyland - talk 13:24, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Thank for your answer!

- I are confused about their definition of resource:

- "Resource.—A concentration of naturally occurring solid, liquid, or gaseous material in or on the Earth’s crust in such form and amount that economic extraction of a commodity from the concentration is currently or potentially feasible."

- What do they mean by "potentially feasible"? At what estimated cost?

- 230 billion tons is about 33 tone per person, while more than 10 tone per person it is not that much actually, given estimated population increase to 10e9 to 12e9 persons during the next 100 years and increased GNP per capita. Gr8xoz (talk) 16:05, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- I think the Solwara 1 project to mine seafloor for massive sulphide deposits is a good example of where "potentially feasible" is transitioning to "currently feasible" because of the economics and the technology available. Sean.hoyland - talk 16:17, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Another example that springs to mind to illustrate the difference between potentially and currently feasible is the hugeImouraren uranium deposits. Although the resource was discovered almost 50 years ago, and mining it has been potentially feasible for a long time, the mine won't be operational until next year for all sorts of reasons. Sean.hoyland - talk 16:35, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Thank you for the link about the Solwara 1 project, it was very interesting, as usual the assesments of the enviromental impact differ very much. It will be interesting to follow.

- The limit between "potentially feasible" and not "potentially feasible" is still very fuzzy to me, even the iron core of the earth would be "potentially feasible" if you extrapolate capabilities far enough in to the future and are into science fiction. Gr8xoz (talk) 22:44, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Even given the low estimate of 10 tones of iron per person, I don't see that as a problem. With recycling, that much should last for centuries, by which time we will be able to mine less accessible sources. StuRat (talk) 00:07, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Aluminum reserves depend on if you only count Bauxite, or if you count all aluminum ores (aluminum makes up 8.3% of the Earth's crust by weight). --Carnildo (talk) 02:24, 30 October 2012 (UTC)

- I know that, see my first post, the question is how much of these 8 % that can be extracted at less than twice the current production cost?Gr8xoz (talk) 17:04, 30 October 2012 (UTC)

- That really depends on if there's a breakthrough in processing techniques or not. Anything that makes electricity cheaper, or that increases the variety of usable ores, will increase the amount that can be extracted. Known bauxite reserves are good for at least another century, so it's not a factor that can be ignored. --Carnildo (talk) 01:49, 31 October 2012 (UTC)

- I know that, see my first post, the question is how much of these 8 % that can be extracted at less than twice the current production cost?Gr8xoz (talk) 17:04, 30 October 2012 (UTC)

Make radioactive material decay faster

Why do you have to wait until radioactive material decays? Isn't any way of just making it decay? Comploose (talk) 13:02, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

No idea about these things at all but is your question related to this article (http://www.businessinsider.com/eu-builds-giant-laser-2012-10)? I came across it earlier and it was referring to a powerful laser that could theoretically destroy nuclear waste. A google search for 'speed up radioactive decay' leads you to a number of science articles talking about this subject. ny156uk (talk) 13:52, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- No there are no known way of speeding up spontaneous radioactive decay. But some radioactive isotopes can be transformed in to stable isotopes by very strong radiation of different types. Gr8xoz (talk) 15:41, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- See Radioactive_decay#Changing_decay_rates for a summary of what is known. As Gr8xoz says, there is no known method of significantly changing decay rates, even in theory, that is both simple and safe and does not involve large amounts of external radiation or enormous power consumption.Gandalf61 (talk) 16:08, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- I still wonder if Förster resonance energy transfer could work on induced gamma emission, though one person's opinion before was "probably not".[7] Wnt (talk) 19:02, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- It took me awhile to find a good link for discussing the lasers-blasting-nuclear-waste issue. Apparently with a high energy laser can transmute isotopes — so you'd try to transmute long-lived iodine-129 into short-lived iodine-128, which then most of the time becomes stable xenon-128. So I guess that's something, if it really works and scales up.--Mr.98 (talk) 19:34, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- I remember reading something about 10 years ago that indicated a discrepancy had been found in the decay rate of a certain heavy isotope under varying physical conditions. Does this strike a bell with anyone? μηδείς (talk) 19:37, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- There are several references from 1996 to present about an observed effect of physical and/or chemical conditions in the section that Gandalf61 mentioned. Not sure if that is close to the timeframe and/or idea you are remembering. DMacks (talk) 19:43, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, thanks, I think it was the phenomenon in the fourth paragraph, since I remember it somehow being related to the sun. Apparently it may just be error.μηδείς (talk) 19:48, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- There is a way to decrease a half-life - it involves alloying the radioisotope, and cooling it to extremely low temperatures. I don't remember the constituents of the alloy. Plasmic Physics (talk) 23:54, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- All of the responses so far seem to deal with changing the spontaneous reaction rate. I don't interpret the Q as being limited to that. Why not jam it into a nuclear reactor, and subject it it to whatever dose of whatever type of radiation is needed to convert it into something else, and so on, until you arrive at something stable ? Sure, it's probably not practical, but it is possible. StuRat (talk) 00:01, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- That's the laser idea, more or less. I suspect the problem is that most of the time you will end up with more radioactive material, not less. It's not so much that you'll arrive at something stable by just adding neutrons to it, but you might go from an element with a half-life of a million years to one with a half-life of a few minutes, which then maybe decays into something stable. (So you're actually making it more radioactive, but briefly so.) My intuition though is that in any real-world materials you'll have no net change in long-term radioactivity, since the isotopes will be quite a soup of possibilities. Not to mention the fact that you're probably creating more waste by running the reactor than you're eliminating... presumably this is what the laser scheme is seeking to get around. I'm kind of dubious of it working in practice, but I'm not a nuclear physicist. --Mr.98 (talk) 16:15, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Battery with unexpectedly high open circuit voltage

Someone I know was working on a device, removed the lead-acid battery and measured its open circuit voltage and got 7.0 V. But it's a nominally 6V battery so it would be 3 cells and each lead-acid cell has a voltage of 2.1 volts so how did the battery give a voltage so much higher than 2.1*3=6.3V? (The battery was apparently defective but they didn't have the equipment to measure its voltage under load, they just replaced it and the device worked so they deduce the battery was bad.) Are there any chemical processes that would occur in a battery that is worn out that would cause a higher open circuit voltage? RJFJR(talk) 14:11, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- For a lead acid battery of the sort used in portable electronic equipment, computer UPS units and other "indoor" applications, the full charge voltage is considered to be 2.35 V per cell (at 25 deg C), not 2.1 V. corresponding to 7.05 V for a nominal 6 V battery. When discharging into a load, a fully charged lead acid battery's voltage rapidly falls to quite close to 2 V per cell and then holds close to that voltage for a comparitively long time, before dropping rapidly as reaches the point of full discharge. Hence the common usage of the terms "6 V", "12 V" etc for 3 and 6 cell batteries.

- However, when measuring the voltage of a battery removed from service which may well be nowhere near full charge, you should consider the accuracy of the meter used. A cheap analogue multimeter for instance, may have an accuracy of +,- 3% of full scale. If the range selected to measure is a 10 V full scale range, then the possible meter error in measuring exactly 6 V is 10 x 0.03 = 0.3 V error. So, if you have a reading of 7.0 V, it could actually be as low as 6.7 V without the meter being faulty. Cheap digital multimeters are generally accurate to 1% of full scale or better, with an additional error of plus or minus 1 digit. Seehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lead_acid_gel_battery

- Keit120.145.36.13 (talk) 15:31, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

The 'cats that look like Hitler' effect?

Along a similar line to black-dog bias, is it true that animal shelters often find it difficult to adopt out cats which facially resemble Adolf Hitler? There was one particular cat in the news last year where this was claimed to be the case. The existence of the http://www.catsthatlooklikehitler.com website would appear to demonstrate that this effect (or at least that people do really notice that some cats look like Hitler) does exist in some form or other...--Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 14:58, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Surely it looks more like Charlie Chaplin. Wnt (talk) 15:26, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- (e/c)If that was claimed to be the case, why are you asking us? However, all those cats have owners who are presumably perfectly happy with them. Cats look no more like Hitler than they look like Charlie Chaplin.--Shantavira|feed me 15:32, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- I ask because I was wondering if the 'cat thing' had ever been studied to the same extent as the 'dog thing', or if it was only ever really an isolated case that was reported as a widely-known 'fact' in the news... --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 15:38, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- We have one of those. We call her charlie because we think she looks like Charlie Chaplin. Dauto (talk) 18:03, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Just in response to Shantavira's 'Cats look no more like Hitler than they look like Charlie Chaplin' point... How's aboutthis one then? --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 18:45, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- ROFL - it really does! There must be some deep lesson about caricature and facial expressions here. Wnt (talk) 19:04, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- who wouldn't adopt a cat that looks like Hitler? I would, and I think it would appeal to both Nazi and antiNazi both.Gzuckier (talk) 01:53, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- You might name it Lorenzo. —Tamfang (talk) 23:19, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

Is theistic evolution inherently teleological?

67.163.109.173 (talk) 15:50, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- No. Comploose (talk) 16:07, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Please explain why. Thanks in advance. 67.163.109.173 (talk) 16:16, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

Sorry, a clarification. Specifically, is theistic evolution in the context of an Abrahamic religion that clings to a belief that man (i.e., H. sapiens) is created in (that religion's) God's image, inherently teleological? 67.163.109.173 (talk) 16:31, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Essentially, yes. Christians believe that God created the universe for a purpose, and theistic evolutionists believe that evlution plays a role in achieving that purpose, so yes, it's inherently teleological. It follows from the nature of the Abrahamic God, who is a person, has a will, and has goals. Dominus Vobisdu (talk) 16:37, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Shouldn't this be on the Humanities desk? Theistic evolution, Teleology - these are things scientists generally look up on Wikipedia. It seems like there should be some range of possibilities about how specific the purpose might be, but no doubt there is some philosophy that has actually put a name to that? Wnt (talk) 18:53, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- If you believe that God is "guiding" evolution (which is usually what is meant by theistic evolution), then yes, it is inherently teleological (there is a goal or end-point). You could, I guess, claim that God just flips a coin and evolves at random... but that's not what anybody ever means by theistic evolution. If you had a polytheistic religion and polytheistic evolution, I guess I could imagine something that was a little less guided... but again, I don't really see that ever being referred to as theistic evolution. --Mr.98 (talk) 19:36, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Well, theoretically you can picture a God who says "hey, I want a universe full of really cool stuff, but I want the critters to make up their own minds ... when they hit on something cool I'll know it when I see it". (Not saying that's how it is, but I'm not sure the answer is obvious) Wnt (talk) 19:58, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- But that's not what "theistic evolution" means — every time it is used, it is assumed that God wants humans to eventually show up. That's teleological. You can certainly have a worldview that says there is a God out there somewhere not paying any attention to anything and just saying, "oh, cool, humans" when they evolve without any intervention, but that's not theistic evolution, that's just natural selection with an inattentive deity. ;-) --Mr.98 (talk) 16:11, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- As a Christian agnostic, in as much as I believe God and evolution have any relationship, this is what I believe. There's a metaphysical end towards which events can be said to be driving, but the material world is only subject to its own rules - God doesn't 'prod evolution along' in any sense. By 'theistic evolution', I understand a position in which God does do that, and so physical processes are viewed as teleological. AlexTiefling(talk) 20:47, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Not an answer, and you might get someone to express this with sources and more clarity on the Humanities desk: There are phenomena such ascarcinisation which hint that Nature, by some means, favors certain recognizable designs, and that evolution does not proceed entirely toward random ends. As the natural laws which favor these shapes in the end are part of an overall structure of logic, it would seem that if this structure is up to God (i.e. that what logically can be deduced from a given set of premises is chosen by God) then those end designs are chosen by God. I note that many people do not think of God as having this sort of power - the power to decide that two and two are three, without otherwise changing or contradicting the rules of mathematics - but it would seem to me that this would be one of the most characteristic powers that define divinity apart from mortal or technological ability. Wnt(talk) 23:42, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Nature does favor certain things - it's called natural selection... Arc de Ciel (talk) 00:13, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- What's the difference between a) a H. sapiens-shaped God making a universe with laws of physics and initial conditions such that, when left alone for about 13-some billion years without being prodded, little beings that resemble it naturally follow, and b) a H. sapiens-shaped God making a universe with laws of physics and initial conditions not necessarily such that about 13-some billion years later little beings shaped like it naturally follow, but prods along "randomness" such that it happens? Just the point (pre-big-bang or post) at which one considers the act of setting up the dominoes, no?67.163.109.173 (talk) 02:22, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- First of all, the word randomness is a bad word to use. Survival of the fittest is far from random.

- If that god is all-knowing then there would be no difference.

- The bible would have to be rewritten of course, something along the lines of: "And in the beginning, God created Heaven and Earth, he created some bacteria, called them Adam and Steve, and waited several billion years for them to evolve in a shape similar to his own".They (talk) 03:27, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Actually, this is a fallacy: an author doesn't live in time dimension of the universe he creates. (George Lucas didn't live during the time of the Galactic Republic) So science can't tell you how long God took to devise the universe, nor in what order he developed the composite elements. Wnt(talk) 04:03, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Are you saying we are all fictional characters and that reality as perceived by most humans is actually a simulated reality?

I like the Matrix too, but I am pretty sure its fiction.

I like the Matrix too, but I am pretty sure its fiction. - God did not write the bible. Humans wrote it. Some people claim that the people who wrote the bible had divine inspiration, which is weird because it contains many factual errors (e.g. the story about streaked rods and Jacob's goats and the idea that the moon emits light) and major portions of it are plagiarized from earlier works. Different parts of the bible were written by different people, over a period of hundreds of years. SeeOld_Testament#Composition. They (talk) 04:13, 28 October 2012 (UTC) p.s. You may enjoy this video.

- My purpose here isn't to argue for Biblical infallibility, but to emphasize that science cannot disprove certain high-order speculations on the nature and origin of the world, specifically whether it is an authored work. Being "pretty sure" The Matrix is fiction is based on what experimental evidence? It is fairly clear that the films indeed are themselves based on religious, specifically Christian ideas. Wnt (talk) 14:01, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- I am sorry, I cannot debate about topics like "What experimental evidence does They have that suggests that reality as experienced by most humans is in fact real and not some kind of simulated reality like in The Matrix" without being stoned. And no, I don't mean that in the Biblical sense, I am referring to recreational drugs. They (talk) 19:45, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- My purpose here isn't to argue for Biblical infallibility, but to emphasize that science cannot disprove certain high-order speculations on the nature and origin of the world, specifically whether it is an authored work. Being "pretty sure" The Matrix is fiction is based on what experimental evidence? It is fairly clear that the films indeed are themselves based on religious, specifically Christian ideas. Wnt (talk) 14:01, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Are you saying we are all fictional characters and that reality as perceived by most humans is actually a simulated reality?

- As far as I understand the theory of evolution (not theistic), the randomness is not what is successful, but the randomness is in genetic mutation, which happens, and then if a given mutation just happens to be better suited to the habitat in which the organism exists, and the organism reproduces with more success than other organisms without the random mutation, that random mutation is said to be selected.67.163.109.173 (talk) 04:01, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- That is correct AFAIK. They (talk) 05:02, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Indeed. Having some mutations is still essential though, since if you didn't have any the organism would never be able to adapt to a changing environment. It's been suggested that if DNA repair were more efficient, this would be selected against for this reason.

- Just to throw in another factor: as far as we know, our universe contains randomness at the quantum level. I think a reasonable argument could be made (if you have infinite control at the time of the Big Bang but no intervention afterwards) that there are no initial conditions that could guarantee an outcome as specific as the evolution of Homo sapiens. You could have a particular probability of everything working out in a certain way, but it wouldn't be 100%. Arc de Ciel (talk) 08:00, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Note that, in accordance with the modern theory and observance of evolution, progressive adaption and evolution is not only dependent on random mutation of ancestral genes, though that is the most common path. It has been shown that co-existent and infective organisms can insert advantageous and disadvantagoes genes into the host DNA. Occaisonally, DNA fragments of something eaten (particularly in single cell organisms or organisms comprising a clump of similar cells, get swallowed up by the cell machinery and incorporated into the cell DNA to be then passed on to daughter cells if it is passive or confers and advantage. It has been shown (described in Scientific American last year as I recall) that this can occur even in humans thought it must occur very infrequently and has obviously in humans no evolutionary significance (only changes in eggs or sperm can be passed on). In some cases, an infective agent multiplies within the cell and gets passed down to daughter cells. Mitochondia, which are essentially compplete parasite organism whithin each cell, confer a very considerable energy advantage to the host. Wickwack 58.169.248.13 (talk) 13:35, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Actually, this is a fallacy: an author doesn't live in time dimension of the universe he creates. (George Lucas didn't live during the time of the Galactic Republic) So science can't tell you how long God took to devise the universe, nor in what order he developed the composite elements. Wnt(talk) 04:03, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- (Outdenting.) One nice little way to sum up naturalistic evolution is to say that there is random variation but with selective retention. You need both for naturalistic evolution — there has to be a pool of variation that isn't guided, there has to be mechanisms in place to get rid of the non-useful variations. There is "randomness" to it, but it's only half of the equation. In my experience Creationists focus on the "random" and forget about the "selection", hence getting themselves in knot about tornados in junk yards, which is randomness without selection. --Mr.98 (talk) 16:11, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Mythbusting Mary Poppins

I know that the movie was meant to be a modern-day fairytale and not intended to be realistic at all, but all the same, there are a couple things in it that I think might make for a good Mythbusters episode. So here goes...

1. Umbrella paraglider

I know it's not possible to take off and fly up without a source of power, but is it possible for a fairly slim woman like Julie Andrews to use an ordinary (non-magical) umbrella to glide down by jumping from a height or by sprinting into a strong headwind? If so, given that a typical umbrella has an area of about 16 sq. ft., what would be the stall speed if running into the wind, and what would be the terminal velocity if jumping from a height? Also, if said fairly slim woman with non-magical umbrella was trapped in a burning building, would it be possible for her to escape using this method and survive? (Note that I do not specify that she survive unhurt.) And last but not least, is it true that a woman by name of Mrs. Graham had fallen from a balloon but survived the fall due to her open umbrella and/or inflated skirt acting as a parachute?

- I don't see how any normal umbrella could be strong enough to stay concave side down. Read aboutthis fatal attempt from a seventh floor. Also, Mythbustersapparently already busted this myth.[11] Clarityfiend (talk) 21:11, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- So, the bottom line is, it will NOT help survive jumping from a height, as the terminal velocity would still be too high. Thanks!24.23.196.85 (talk) 21:22, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- But then again, what about taking off by sprinting into a strong headwind? (I actually managed to do this, when I was a boy of 14.)24.23.196.85 (talk) 21:25, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Yes I have experienced this as well, with a very strong umbrella and opening it whilst running.--Gilderien Chat|List of good deeds 21:37, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- You actually lifted off like I did? 24.23.196.85 (talk) 22:14, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Details from my own attempt: Wind strength was 4 on the Beaufort scale, gusting to 5; I don't remember my own weight, but I couldn't have been very heavy because I was only 14 and slim; I was running as fast as I could, which could have been as fast as 20 mph (I was a fast runner, but a bad starter, and still am); the umbrella's angle of attack at liftoff was about 5 degrees; and the total air time was about 2 seconds, at an altitude of about 1 to 1.5 feet, covering about 10 yards. 24.23.196.85 (talk) 22:24, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, although not that far. Admittedly it was in the lake district, so there was a "lip" adjacent to the track I was on, causing a very strong upwards current of air.--Gilderien Chat|List of good deeds 00:46, 31 October 2012 (UTC)

- Details from my own attempt: Wind strength was 4 on the Beaufort scale, gusting to 5; I don't remember my own weight, but I couldn't have been very heavy because I was only 14 and slim; I was running as fast as I could, which could have been as fast as 20 mph (I was a fast runner, but a bad starter, and still am); the umbrella's angle of attack at liftoff was about 5 degrees; and the total air time was about 2 seconds, at an altitude of about 1 to 1.5 feet, covering about 10 yards. 24.23.196.85 (talk) 22:24, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- There are giant fans pointing upwards which allow a person without an umbrella to hover over them, so, it stands to reason that they could also do so using a properly reinforced umbrella. Of course, her dress would fly up, but we can just consider that a bonus. :-) StuRat (talk) 00:21, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Even more exciting with a proper fox frame and a sufficiently powerful vortex generator I see no reason Nanny may not make it beyond the atmosphere. But perhaps a space fountain would be a better idea. It could be set up to work through the chimneys, and could draw her up by a suitable rare earth magnet in her carpet bag. Rich Farmbrough, 01:16, 28 October 2012 (UTC).

- Great ideas, everyone! (Well, except she wouldn't be able to pass through a chimney, as it's only 13" by 9".) :-D 24.23.196.85 (talk) 01:55, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- You may be interested in the story of Sarah Ann Henley. --TammyMoet (talk) 10:08, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Wow, what an amazing survival story! BTW, a typical woman's skirt would have a surface area of about 20 square feet -- still not enough to survive a landing on a hard surface, but enough to give a fighting chance of surviving a soft-surface impact (as was the case here). 24.23.196.85 (talk) 02:07, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- Do you base your calculation on a typical crinoline skirt of the era, or a typical modern skirt? Just curious. Some crinolines took a huge amount of material. --TammyMoet (talk) 09:36, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- BTW, does anyone have any details on Mrs. Margaret Graham the balloonist, and how exactly she survived a 100-foot fall from her balloon? I've read that she survived because her dress flew up and acted like a parachute (similar to what happened with Sarah Ann Henley), but I can't verify this info and Wikipedia has no article about her at all. 24.23.196.85 (talk) 02:30, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- Wow, what an amazing survival story! BTW, a typical woman's skirt would have a surface area of about 20 square feet -- still not enough to survive a landing on a hard surface, but enough to give a fighting chance of surviving a soft-surface impact (as was the case here). 24.23.196.85 (talk) 02:07, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- For glinding with an umbrella, read Erich Kästner's The Flying Classroom, which shows it doesn't work. Of course, this is a work of fiction, but it's worth to read anyway. – b_jonas 22:36, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

2. "Posts, everyone!"

When Admiral Boom fires his cannon, would the resulting seismic wave smash the neighbors' crockery and other fragile items, and if so, within what radius? More to the point, is it possible for this to happen without the airborne shockwave also blowing out all the windows?

24.23.196.85 (talk) 20:54, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- A sound wave could do this, provided it was at the resonant frequency of those items it broke. However, this is extremely unlikely, as that would require a lot of energy at a very high frequency, and that's not something a cannon is likely to create. StuRat (talk) 00:17, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

24.23.196.85 (talk) 20:54, 27 October 2012 (UTC)

- If crockery is sufficiently finely balanced any shock wave could cause it to rattle or fall to the floor. Rich Farmbrough, 01:09, 28 October 2012 (UTC).

- I remember reading that a 19th century British coastal artillery battery (possibly Coalhouse Fort in Essex) used to send a soldier round to the neighbouring houses before practice firing, to tell them to open their windows in case they were broken by the blast. I've just had a look for a reference, but could only find this account (last page) of coastal artillery in action at Weymouthin 1940; “A suspect vessel disregarded recognition signals and so No.1 gun of the fort was ordered to fire a shell across its bows. This gun misfired and so No. 1 gun of the Breakwater fort was so ordered. The shell ricocheted off the water in front of the vessel, passed between it’s masts and headed on for Lulworth! The vessel failed to stop, arriving safely in Weymouth Harbour to disgorge French troops who had fled Dunkirk. The blast from the gun shattered all the windows in the Sapper’s barracks on the Breakwater.” I believe the gun in question was a BL 6 inch Mk VII naval gun, rather larger than the signal cannon in the film. Alansplodge (talk) 01:21, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Thanks for the input, everyone! So I gather that the effect would most likely be the opposite -- the windows would shatter, but the crockery would probably remain intact unless precariously balanced? 24.23.196.85 (talk) 01:57, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Most often, yes. StuRat (talk) 02:00, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Collars for control knobs

Control knobs that go on spindles with (or indeed without) a flat sometimes have a steel collar around the part of the knob that slips on to the spindle. (I worked on a machine that put these on a component for central heating thermostats many years ago, which was interesting in its own right for several reasons.) So two questions, what are these collars called, and where can they be obtained? Rich Farmbrough, 18:08, 27 October 2012 (UTC).

- In the electronics industry, there are two kinds of knob (apart from knobs that do not have a metal insert and are force fitted): ones with metal inserts that provide a strong base to put a threaded hole into for a retaining grub-screw, and one s with metal inserts that are longitudinal split, with a peripheral thread thread cut. A nut screwed on this thread progressively compresses the split insert onto the control shaft. The actual knob, cast in plastic, in both types conceals the metal parts. In both cases the metal insert is usually brass and is called a collet - however, when an electronic engineer calls for acollet knob, he usually has the second type in mind. If he wants a grub-screw knob, he'll usually say he wants a grub-screw. The more widely known use of the word collet is in machines and machine tooling. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collet. You may like to google collet knobs. Perhaps you had this sort of thing in mind.

- However, there is a another common type that has a plated or passivated spring steel collar or ring that surrounds a molded split part of the knob to clamp it onto the shaft. This type is more common in Asian-made equipment. In this case the metal part should be called a compression ring or compression spring.

- You can obtain control knobs from suppliers specialising in electronic parts. RS Components and Element 14 both have a good range and have stores in many countries. Keit 121.221.226.4 (talk) 02:20, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Ah thank you! The word I was searching for was collet but what I actually meant was compression spring. And I have the knob (which is a friction fit, rather than force fit) I just want to reinforce it with a compression spring - if possible. Rich Farmbrough, 03:05, 29 October 2012 (UTC).

- Ah thank you! The word I was searching for was collet but what I actually meant was compression spring. And I have the knob (which is a friction fit, rather than force fit) I just want to reinforce it with a compression spring - if possible. Rich Farmbrough, 03:05, 29 October 2012 (UTC).

October 28

Generator

What is the minimal optimal usage for a 30 amp generator to maximize efficiency of fuel? Equidistant from running generator with nothing hooked up and using all 30 amps to run lights in the daytime.68.83.98.40 (talk) 03:03, 28 October 2012 (UTC) Or how many amps does the gen produce just idling?68.83.98.40 (talk) 03:05, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- If there's nothing hooked up to the generator (as in, open circuit), then it will produce no amps at all.24.23.196.85 (talk) 03:11, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Yes, that is one extreme in my example. The other extreme is getting "no real use" while producing all 30 amps .68.83.98.40 (talk) 03:16, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- If you're asking about the point at which the generator will have the highest efficiency, then it depends on the resistance of the circuit, as well as on the characteristics of the diesel that runs the unit. Generally, the higher the circuit's resistance (given the exact same engine and generator unit), the higher the power setting that you'll have to use in order to get the maximum efficiency. Just my non-expert opinion. 24.23.196.85 (talk) 03:25, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Thanks, anyone know a typical amp output for a 30 amp generator while idling (20 hp?)68.83.98.40 (talk) 03:29, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- The internal losses in a generator can be modelled as L = k0 + k1I + k2I2 where k0, k1, and k2 are constants particular to the actual generator and I is the output current. Typically, maximum conversion efficiency is attained at around 65% to 80% of full output. Efficiency at no load is obviously zero as 24.23.196.85 already stated, as the amps output is zero but the engine is running and consuming fuel. Fuel consumption at high idle depends on the engine type (recent model, old model, degree of turbo charging) but will be somewhere around 5% of the full load value for generators capable of 30 A per phase at 415 V. Conversly, if the engine is running at high idle, there cannot be any significant electrical output as if there was, the engine would have to slow down or advance the throttle. The correct term for the condition of a genset running without any load ishigh idle as the engine has to be turning at full RPM to get the correct voltage and be ready for any load being instantly switched on. If the engine is run at low speed idle, like a car engine idling, it is called low idle. Keit 124.182.151.138 (talk) 06:05, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Nanotchnology and solar cells

How nanosolar cells work ? — Preceding unsigned comment added by41.209.224.61 (talk) 05:21, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Nanosolar is the name of a company, see Nanosolar#Technology. They (talk) 05:40, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

what is the development that nanotechnology provides to solar cell? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 41.209.224.61 (talk • contribs)

- Did you click on the link I wrote above? Molecular self-assembly is kind of awesome. They (talk) 09:29, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

i want another resource — Preceding unsigned comment added by41.209.224.61 (talk) 10:43, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Well, I don't think we can help you. They (talk) 10:53, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- why? ...the answer should be from Wikipedia pages — Preceding unsigned comment added by 41.209.224.61 (talk) 11:07, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- And it is:

| “ | These details involve a semiconductor ink that it claims will enable it to produce solar cells with a basic printing process, rather than using slow and expensive high-vacuum based thin-film deposition processes. The ink is deposited on a flexible substrate (the “paper”), and then nanocomponents in the ink align themselves properly via molecular self-assembly. | ” |

| — Wikipedia editor(s) | ||

- For additional resources dealing with the company, see Nanosolar#References. StuRat (talk) 06:22, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

why is it so hard to find the longitudinal diameter of the hydrogen molecule?

This is different from the VDW radius or the bond length. I need to calculate the mean free path of hydrogen molecules, not hydrogen gas, and google only turns up the VDW radius of the hydrogen atom or the bond length of the hydrogen molecule, which is annoying. 71.207.151.227(talk) 07:41, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Please clarify what you want. Pure hydrogen gas consists of a mixture of monatomic hydrogen (H) and diatomic hydrogen (H2). The proportions of H and H2 are a function of temperature - at room temperature it is virtually all H2, and the proprtion that is H2 decreeases as temperature increases, reaching a 50:50 mix at about 4400 K. You can calculate the proportions by solving the modified arrhenious equations for t → very large, or by using dissociation theory. You can get the constants required in either case from standard tables or from the NIST website.

- Since colliding molecules can have any orientaion, you don't need the longitudinal diameter, unless you introduce a steric factor as well - it will then be equivalent to the collision diameter given in most tables.

- Since hydrogen gas is a mix of H and H2, at high temperatures if you need acuracy you need to calculate for 3 types of collisions: H and H, H and H2, and H2 and H2, at the appropriate concentrations. Wickwack 58.169.248.13 (talk) 12:02, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- If you know the VDW radius and the bond-length, a diatomic is obviously linear, so the "VDW length" is radius+bond+radius. But depending what you're shooting at it, the scattering cross-section used to calculate the mean free path in an experiment might be some other function rather than simple geometric size (especially one that would need kinetic averaging among various orientations). DMacks (talk) 16:49, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Elements, other than Hydrogen and Uranium, for nuclear fusion and fission

It is well-known that hydrogen present in Sun helps in nuclear fusion inside it. Uranium-235 is generally used for nuclear fission on earth by scientists for energy generation. Are there other elements which can be used for nuclear fission and fusion ? Sunny Singh (DAV) (talk) 08:16, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- See Nuclear fuel cycle, Nuclear power, Fusion power and perhaps Nuclear reprocessing which describes possibilities of main interest in a resonable amount of detail (albeit not in a simple format). The most common proposed alternative to uranium as the fuel source is Thorium-232, note however this for use in a breeder reactor to produce uranium-233 and later 235. You can also design a breeder reactor to use uranium-238. Plutonium-239 may be used together with uranium although this has likely been produced from uranium either intentionally (perhaps for weapons) or as a byproduct as a nuclear reactor. There is also some interest in using the minor actinides byproducts as fuel, our article mentions americium as one currently being tested. When it comes to fusion, deuterium (hydrogen-2) or hydrogen-1 is generally used in most proposals although you may also need boron or lithium as part of the cycle. Nil Einne (talk) 09:23, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Here's something interesting: the US has so much neptunium, that they don't know what to do with it all, so they've decided to bury it. Plasmic Physics (talk) 09:45, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- In principle, most nuclei can be used in fusion, and just that happens in stars. See stellar nucleosynthesis. Similarly, most heavy nuclei can be split. There is a natural maximum of (per nucleon) nuclear binding energy at around Fe56, so "normal" processes will rarely produce heavier elements from lighter ones, and vice versa. There are some fusion- and fission reactions that are more suitable for technological energy generation, and these usually involve very light and very heavy nuclei. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 10:29, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Helium-3 is a good material to use for nuclear fusion. 24.23.196.85 (talk) 02:00, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- In principle, most nuclei can be used in fusion, and just that happens in stars. See stellar nucleosynthesis. Similarly, most heavy nuclei can be split. There is a natural maximum of (per nucleon) nuclear binding energy at around Fe56, so "normal" processes will rarely produce heavier elements from lighter ones, and vice versa. There are some fusion- and fission reactions that are more suitable for technological energy generation, and these usually involve very light and very heavy nuclei. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 10:29, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Follow up question,

In fission energy emitted by heavy atoms (other than uranium) emit same amount of energy as emitted by uranium, yes or no and why. Does the same case happen with hydrogen in fusion ? Sunny Singh (DAV) (talk) 12:26, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- No, the amount of energy released is basically different for each nuclear reaction. See the link on nuclear binding energy above - the energy you get from splitting or fusion is the difference in the sum of binding energy before and after the reaction for all involved nucleons. But for most processes, the nuclear binding energy is orders of magnitude greater than for chemical reactions. So any nuclear fuel is relatively very energy-dense. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 14:33, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- For fusion reactions not taking place inside of a star, fusing elements heavier than hydrogen is very difficult. The reason for this is that the forces required to overcome the electromagnetic repulsion of the nuclei to be fused become pretty prohibitive — and hey, even fusing hydrogen is hard, outside of a star. Even hydrogen bombs don't fuse anything larger than tritium and deuterium. (They use lithium in their fuel, but only because it turns into tritium after being hit with neutrons.) --Mr.98 (talk) 16:04, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

Does the ideal gas law apply to supercritical fluids?

Really basic and important physics here, yet I don't know the answer and our articles don't seem to give it: does the ideal gas law apply to some, all, or no supercritical fluids? What are the boundaries of the region where it applies?

Looking this up in our archive, I found[12] and[13] which expressed doubt it applied; Google delivered[14] which, unless I misinterpret, says it applies to all supercritical fluids. But I have a hard time picturing a supercritical fluid can keep to that law under up to infinite pressure! [15] is a fringy-looking publication which says the critical point is really the boundary of four phases, one of which is a "delta phase" with multiple molecules in association; I think that is saying there is a boundary within supercritical fluids between those which follow ideal gas law and those that don't. In short: please, somebody who really knows their physics should figure this out, and update those two articles accordingly. Thanks. Wnt (talk) 15:42, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- At the critical point, the specific heat becomes infinite. The specific heat contour lines bend near the CP because of this. Therefore the ideal gas laws cannot apply without significant correction near the critical point. What is happening is most easily seen if you plot specific heat contours on a graph of temperature versus internal energy, along with the saturation (boundary) lines. I haven't figured out how to post diagrams in Ref Desk. If you can tell me the secret of how to do it, I'll give you a diagram or two that will make things clear. As a matter of personal policy, I don't edit WP articles directly, as certain admins have spent a fair amount of effort trying to block/exclude me, and I have no wish to a) waste my time, and b) upset folk. Wickwack124.182.136.192 (talk) 16:09, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- Well, if you have that kind of trouble, it's probably desirable in general to avoid the tedious scope and copyright issues, etc. (even though they shouldn't apply in this case for your own diagram) of uploading files here or even at Wikimedia Commons - just find any old spot online off the List of photo sharing websites to upload a file and post a link to it here. Wnt (talk) 16:19, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- On a quick check, I cannot see how to upload to Wikipedia Commons, and think you have to be registered. I post to Ref Desk only using dynamic IP, without a registered username, due to admin actions as mentioned before. I've never used photo sharing sites - I will investigate later today after I get some paying work done if nobody else helps you. Or you might like to do your own plot. It's easily done using the data for several substances listed on the NIST website. Wickwack 120.145.174.229 (talk) 00:56, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- Well, if you have that kind of trouble, it's probably desirable in general to avoid the tedious scope and copyright issues, etc. (even though they shouldn't apply in this case for your own diagram) of uploading files here or even at Wikimedia Commons - just find any old spot online off the List of photo sharing websites to upload a file and post a link to it here. Wnt (talk) 16:19, 28 October 2012 (UTC)

- In reference to the heat capacity near the critical point, I see we have an article critical exponent, though it is anything but obvious what it all means. [16] seems like an interesting source on the asymptote. All kinds of interesting phenomena, like the hysteresis in density according to temperature (how would life use that? I can barely speculate...) - but to the uninitiated, it gives up its meaning somewhat grudgingly. They give a modified ideal gas law, P = ρRT/(1-bρ) - aρ2, where a is an attraction force constant and b is a repulsion force constant, but I don't know what these are for hydrogen nor why they matter more in one area of the phase diagram (and which?) than another. (They give some gnarlier equations after that...) A clearer answer on where the ideal gas law applies would still help me. Wnt (talk) 04:02, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- The ideal gas law deviates from real gases at higher pressures, and supercritical fluids are generally under very pressures. Ideal gas law#Deviations from real gases. If you lower the pressure below the critical pressure, you don't have a supercritical fluid. You have an ordinary gas. So, for the range of temperatures and pressures where the ideal gas law is a valid approximation of real behavior, there aren't supercritical fluids. There are the Van der Waals equations, which are also approximations, but are better approximations than the Ideal Gas Law itself. --Jayron32 04:13, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- It would be useful if the pressure-density curves for some gas (hydrogen would be nice) at a lot of different temperatures posted were someplace handy. Trying the Van der Waals equation for grins, assuming we have a comfy 300 K hydrogen ocean at the pressure of the critical point (12.8 atm = 1300 kPa) on Saturn at I think what the article describes as the bottom of the atmosphere, then from here we see a=0.2476 L2bar/mol2, b=0.02661 L/mol for hydrogen; oxygen is 1.378 L2bar/mol2, 0.03183 L/mol. So for 1 mole of hydrogen:

- (12.8 atm + 1 mol^2*0.2476 L2bar/mol2/V2)(V-(1 mol)(0.02661 L/mol))=(1 mol)(0.08205746 L atm /K mol)(300 K) === (12.8 atm + 0.2444 L2atm/V2)(V-0.02661 L)=24.62 L atm === this cubic seems to work out at V=1.95 for 1 mole of hydrogen.

- (12.8 atm + 1 mol^2*1.378 L2bar/mol2/V2)(V-(1 mol)(0.3183 L/mol))=(1 mol)(0.08205746 L atm/K mol)(300 K) === (12.8 atm + 1.36 L2atm/V2)(V-0.03183 L)=24.62 L atm === this cubic seems to work out at V=1.9 for 1 mole of oxygen.

- Now the outcome here, for these equations, is that there's only a small difference between the hydrogen and the oxygen, i.e. the hydrogen is still about as buoyant (more so, I think) than it is under less compressed conditions - there's no "bubble of gaseous oxygen rising in a sea of liquid hydrogen" implied by these a and b numbers. But I have no idea if the equation applies at all, or if the supercritical hydrogen is far more densely packed - this was just a reality check for what it works out to say. Wnt (talk) 05:55, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

- It would be useful if the pressure-density curves for some gas (hydrogen would be nice) at a lot of different temperatures posted were someplace handy. Trying the Van der Waals equation for grins, assuming we have a comfy 300 K hydrogen ocean at the pressure of the critical point (12.8 atm = 1300 kPa) on Saturn at I think what the article describes as the bottom of the atmosphere, then from here we see a=0.2476 L2bar/mol2, b=0.02661 L/mol for hydrogen; oxygen is 1.378 L2bar/mol2, 0.03183 L/mol. So for 1 mole of hydrogen: