History of feminism

| This article is currently undergoing a major edit by the Guild of Copy Editors. As a courtesy, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. The copy editor who added this notice is listed in the page history. This page was last revised at 08:20, 8 May 2013 (UTC) (11 years ago) by Czar (talk · contribs) (). Please remove {{GOCEinuse}} from this page as this page has not been edited for at least 24 hours. If you have any questions or concerns, please direct them to the Guild of Copy Editors' talk page. Thank you for your patience. |

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (May 2013) |

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of feminism is the chronological narrative of the movements and ideologies aimed at defining, establishing, and defending equal political, economic, and social rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes and goals depending on time, culture, and country, most Western feminist historians assert that all movements that work to obtain women's rights should be considered feminist movements, even when they did not (or do not) apply the term to themselves.[1][page needed][2][page needed][3][4][5][6][7] Other historians limit the term to the modern feminist movement and its progeny, and instead use the label "protofeminist" to describe earlier movements.[8][example needed]

Modern Western feminist history is split into three time periods, or "waves", each with slightly different aims based on prior progress.[9][10] First-wave feminism of the 19th and early 20th centuries focused on overturning legal inequalities, particularly women's suffrage. Second-wave feminism (1960s–1980s) broadened debate to include cultural inequalities, gender norms, and the role of women in society. Third-wave feminism (1990s–2000s) refers to diverse strains of feminist activity, seen as both a continuation of the second wave and a response to its perceived failures.[11]

Introduction

"What our Paris Correspondent describes as a 'Feminist' group ... in the French Chamber of Deputies"

Daily News (UK)[12]

The terms "feminism" or "feminist" first appeared in France and The Netherlands in 1872 (as les féministes),[13] Great Britain in the 1890s, and the United States in 1910.[14][15] The Oxford English Dictionary lists 1894 for the first appearance of "feminist" and 1895 for "feminism".[16] The British Daily News introduced "feminist" to the English language in a report from France.[12][when?] Before this time, the term more commonly used was "Woman's Rights",[citation needed] hence Queen Victoria's description of this "mad, wicked folly of 'Woman's Rights'".[17][unreliable source?]

Early feminism

This article may need to summarize its corresponding main article in better quality. |

People and activists who discussed or advanced women's equality prior to the existence of the feminist movement are sometimes labeled protofeminist.[8] Some scholars, however, criticize this term's usage.[6][18][why?] Some argue that it diminishes the importance of earlier contributions,[19] while others argue that feminism does not have a single, linear history as implied by terms such as protofeminist or postfeminist.[12]

French writer Christine de Pizan (1364 – c. 1430), the author of The Book of the City of Ladies and Epître au Dieu d'Amour (Epistle to the God of Love) is cited by Simone de Beauvoir as the first woman to denounce misogyny and write about the relation of the sexes.[20] Other early feminist writers include Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa and Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi, who worked in the 16th century,[21] and the 17th-century writers Hannah Woolley in England,[22] Juana Inés de la Cruz in Mexico,[23] Marie Le Jars de Gournay, Anne Bradstreet, and François Poullain de la Barre.[21]

One of the most important 17th-century feminist writers in the English language was Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne.[24][25][26][why?]

18th century: the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was characterized by secular intellectual reasoning and a flowering of philosophical writing. Many Enlightenment philosophers defended the rights of women, including Jeremy Bentham (1781), Marquis de Condorcet (1790), and, perhaps most notably, Mary Wollstonecraft (1792).[27]

Jeremy Bentham

The English utilitarian and classical liberal philosopher Jeremy Bentham said that it was the placing of women in a legally inferior position that made him choose the career of a reformist at the age of eleven. Bentham spoke for complete equality between sexes including the rights to vote and to participate in government. He opposed the asymmetrical sexual moral standards between men and women.[28]

In his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1781), Bentham strongly condemned many countries' common practice to deny women's rights due to allegedly inferior minds.[29] Bentham gave many examples of able female regents.

Marquis de Condorcet

Nicolas de Condorcet was a mathematician, classical liberal politician, leading French revolutionary, republican, and Voltairean anti-clericalist. He was also a fierce defender of human rights, including the equality of women and the abolition of slavery, unusual for the 1780s. He advocated for women's suffrage in the new government in 1790 with De l'admission des femmes au droit de cité (For the Admission to the Rights of Citizenship For Women) and an article for Journal de la Société de 1789.[30]

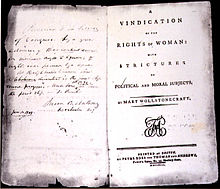

Wollstonecraft and A Vindication

Perhaps the most cited feminist writer of the time was Mary Wollstonecraft, often characterized as the first feminist philosopher. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) is one of the first works that can unambiguously be called feminist, although by modern standards her comparison of women to the nobility, the elite of society (coddled, fragile, and in danger of intellectual and moral sloth) may at first seem dated as a feminist argument. Wollstonecraft identified the education and upbringing of women as creating their limited expectations based on a self-image dictated by the male gaze.[citation needed] Despite her perceived inconsistencies[note 1] reflective of problems that had no easy answers, this book remains a foundation stone of feminist thought.[3]

Wollstonecraft believed that both genders contributed to inequality. She took women's considerable power over men for granted, and determined that both would require education to ensure the necessary changes in social attitudes. Given her humble origins and scant education, her personal achievements speak to her own determination. Wollstonecraft attracted the mockery of Samuel Johnson, who described her and her ilk as "Amazons of the pen". Based on his relationship with Hester Thrale,[32] he complained of women's encroachment onto a male territory of writing, and not their intelligence or education. For many commentators, Wollstonecraft represents the first codification of "equality" feminism, or a refusal of the feminine,[clarification needed] as a child of the Enlightenment.[33][34]

Other important writers

Other important writers of the time included Catherine Macaulay, who argued in 1790 that the apparent weakness of women was caused by their miseducation.[35] Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht wrote in Sweden.[clarification needed] The Natuurkundig Genootschap der Dames (Women's Society for Natural Knowledge), considered the first scientific society for women, met regularly between 1785 and 1881 in Middelburg, southern Holland, and dissolved in 1887.[36][37] Journals for female scientists became popular during this period.[38]

19th century

The feminine ideal

19th-century feminists reacted to cultural inequities including the pernicious widespread acceptance of the Victorian image of women's "proper" role and "sphere".[39][clarification needed] This "feminine ideal" was typified in Victorian conduct books such as Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management and Sarah Stickney Ellis's books.[40] The Angel in the House (1854) and El ångel del hogar, bestsellers by Coventry Patmore and Maria del Pilar Sinués de Marco, came to symbolize the Victorian feminine ideal.[41]

Feminism in fiction

As Jane Austen addressed women's restricted lives in the early part of the century,[42] Charlotte Brontë, Anne Brontë, Elizabeth Gaskell, and George Eliot depicted women's misery and frustration.[43] In her autobiographical novel Ruth Hall (1854),[44] American journalist Fanny Fern describes her own struggle to support her children as a newspaper columnist after her husband's untimely death.[45] Louisa May Alcott penned a strongly feminist novel,[46] A Long Fatal Love Chase (1866), about a young woman's attempts to flee her bigamist husband and become independent.[47]

Male authors also recognized injustices against women. The novels of George Meredith, George Gissing,[48] and Thomas Hardy,[49] and the plays of Henrik Ibsen[50] outlined the contemporary plight of women. Meredith's Diana of the Crossways (1885) is an account of Caroline Norton's life.[51] One critic later called Ibsen's plays "feministic propaganda".[12]

Marion Reid and Caroline Norton

At the outset of the 19th century, the dissenting feminist voices were of little social influence.[citation needed] There was little sign of change in the political or social order, nor any evidence of a recognizable women's movement. Collective concerns began to coalesce by the end of the century, paralleling the emergence of a stiffer social model and code of conduct that Marion Reid (and later John Stuart Mill) would refer to as a "womanliness"[3] that admitted to "self-extinction".[clarification needed] While the increased emphasis on feminine virtue partly stirred the call for a woman's movement, the tensions that this role duality caused for women plagued many early-19th-century feminists with doubt and worry, and fueled opposing views.[52]

In Scotland, Reid published her influential A plea for women in 1843,[53] which proposed a transatlantic Western agenda for women's rights, including voting rights for women.[54]

Caroline Norton advocated for changes in British law. She discovered a lack of legal rights for women upon entering an abusive marriage.[55] The publicity generated from her appeal to Queen Victoria[56] and related activism helped change English laws to recognize and accommodate married women and child custody issues.[55]

Florence Nightingale and Frances Power Cobbe

While many women including Norton were wary of organized movements,[57] their actions and words often motivated and inspired such movements.[citation needed] Among these was Florence Nightingale, whose conviction that women had all the potential of men but none of the opportunities[58] impelled her storied nursing career.[59] At the time, her feminine virtues were emphasized over her ingenuity, an example of the bias against acknowledging female accomplishment in the mid-1800s.[59]

Due to varying ideologies, feminists were not always supportive of each other's efforts. Harriet Martineau and others dismissed Wollstonecraft's[60] contributions as dangerous, and deplored Norton's[60] candidness, but seized on the abolitionism campaign she[who?] had witnessed in the United States[61] as one that should logically be applied to women. Her Society in America[62] was pivotal: it caught the imagination of women who urged her to take up their cause.[citation needed]

Anna Doyle Wheeler was influenced by Saint Simonian socialists while working in France. She advocated for suffrage and attracted the attention of Benjamin Disraeli, the Conservative leader, as a dangerous radical on a par with Jeremy Bentham.[citation needed] She would later inspire early socialist and feminist advocate William Thompson,[63] who wrote the first work published in English to advocate full equality of rights for women, the 1825 "Appeal of One Half of the Human Race".[64]

Feminists of previous centuries charged women's exclusion from education as the central cause for their domestic relegation and denial of social advancement, and women's 19th-century education was no better.[citation needed] Frances Power Cobbe, among others, called for education reform, an issue that gained attention alongside marital and property rights, and domestic violence.

Female journalists like Martineau and Cobbe in Britain, and Margaret Fuller in America, were achieving journalistic employment, which placed them in a position to influence other women. Cobbe would refer to "Woman's Rights" not just in the abstract, but as an identifiable cause.[citation needed]

Ladies of Langham Place

Barbara Leigh Smith and her friends met regularly during the 1850s in London's Langham Place to discuss the united women's voice necessary for achieving reform. These "Ladies of Langham Place" included Bessie Rayner Parkes and Anna Jameson. They focused on education, employment, and marital law. One of their causes became the Married Women's Property Committee of 1855.[citation needed] They collected thousands of signatures for legislative reform petitions, some of which were successful. Smith had also attended the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in America.[55][65]

Smith and Parkes, together and apart, wrote many articles on education and employment opportunities. In the same year as Norton, Smith summarized the legal framework for injustice in her 1854 A Brief Summary of the Laws of England concerning Women.[66] She was able to reach large numbers of women via her role in the English Women's Journal. The response to this journal led to their creation of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women (SPEW). Smith's Married Women's Property committee collected 26,000 signatures to change the law[clarification needed] for all women, including those unmarried.[55][65]

Harriet Taylor published her Enfranchisement in 1851, and wrote about the inequities of family law. In 1853, she married John Stuart Mill, and provided him with much of the subject material for The Subjection of Women. Taylor's relatively low profile after her marriage has been a subject of speculation.[citation needed]

Emily Davies also encountered the Langham group, and with Elizabeth Garrett created SPEW branches outside of London.

Educational reform

The interrelated barriers to education and employment formed the backbone of 19th-century feminist reform efforts, for instance, as described by Harriet Martineau in her 1859 Edinburgh Journal article, "Female Industry".[clarification needed] These barriers did not change in conjunction with the economy. Martineau, however, remained a moderate, for practical reasons, and unlike Cobbe, did not support the emerging call for the vote.[citation needed]

The education reform efforts of women like Davies and the Langham group slowly made inroads. Queen's College (1848) and Bedford College (1849) in London began to offer some education to women from 1848. By 1862, Davies established a committee to persuade the universities to allow women to sit for the recently established Local Examinations,[clarification needed] and achieved partial success in 1865. She published The Higher Education of Women a year later. Davies and Leigh Smith founded the first higher educational institution for women and enrolled five students. The school later became Girton College, Cambridge in 1869, Newnham College, Cambridge in 1871, and Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford in 1879. Bedford began to award degrees the previous year. Despite these measurable advances, few could take advantage of them and life for female students was still difficult.[clarification needed]

In the 1883 Ilbert Bill controversy, a British India bill that proposed Indian judicial jurisdiction to try British criminals, Bengali women in support of the bill responded by claiming that they were more educated than the English women opposed to the bill, and noted that more Indian women had degrees than British women at the time.[67][clarification needed]

As part of the continuing dialogue between British and American feminists, Elizabeth Blackwell, one of the first American women to graduate in medicine (1849), lectured in Britain with Langham support. They[who?] also supported Elizabeth Garrett's attempts to receive a British medical education despite virulent opposition. She eventually took her degree in France. Garrett's very successful 1870 campaign to run for London School Board office is another example of a how a small band of very determined women were beginning to reach positions of influence at the local government level.[citation needed]

Women's campaigns

Campaigns gave women opportunities to test their new political skills and to conjoin disparate social reform groups. Their successes include the campaign for the Married Women's Property Act (passed in 1882) and the campaign to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts of 1864, 1866, and 1869, which united women's groups and utilitarian liberals like John Stuart Mill.[68]

Generally, women were outraged by the inherent inequity and misogyny of the legislation.[citation needed] For the first time, women in large numbers took up the rights of prostitutes. Prominent critics included Blackwell, Nightingale, Martineau, and Elizabeth Wolstenholme. Elizabeth Garrett, unlike her sister, Millicent, did not support the campaign, though she later admitted that the campaign had done well.[citation needed]

Josephine Butler, already experienced in prostitution issues, a charismatic leader, and a seasoned campaigner, emerged as the natural leader[69] of what became the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts in 1869.[70][71] Her work demonstrated the potential power of an organized lobby group. The association successfully argued that the Acts not only demeaned prostitutes, but all women and men by promoting a blatant sexual double standard. Butler's activities resulted in the radicalization of many moderate women. The Acts were repealed in 1886.[citation needed]

On a smaller scale, Annie Besant campaigned for the rights of matchgirls (female factory workers) and against the appalling conditions under which they worked. Her work became a method for raising public concern over social issues.[citation needed]

First-wave feminism

The 19th- and early 20th-century Anglosphere feminist activity that sought to win women's suffrage, female education rights, better working conditions, and abolition of gender double standards is known as first-wave feminism. The term "first-wave" was coined retrospectively when the term second-wave feminism was used to describe a newer feminist movement that fought social and cultural inequalities beyond basic political inequalities.[citation needed]

In America, feminist movement leaders campaigned for the national abolition of slavery and Temperance before championing women's rights. American first-wave feminism involved a wide range of women, some belonging to conservative Christian groups (such as Frances Willard and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union), others resembling the diversity and radicalism of much of second-wave feminism (such as Stanton, Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and the National Woman Suffrage Association, of which Stanton was president). First-wave feminism in the United States is considered to have ended with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1919), which granted women the right to vote in the United States.

The antislavery campaign of the 1830s served as both a cause ideologically compatible with feminism and a blueprint for later feminist political organizing. Attempts to exclude women only strengthened their convictions.[citation needed] Sarah and Angelina Grimké moved rapidly from the emancipation of slaves to the emancipation of women. The most influential feminist writer of the time was the colourful journalist Margaret Fuller, whose Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published in 1845. Her dispatches from Europe for the New York Tribune helped create to synchronize the women's rights movement.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott met in 1840 while en route to London where they were shunned as women by the male leadership of the first World's Anti-Slavery Convention. In 1848, Mott and Stanton held a woman's rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, where a declaration of independence for women was drafted. Lucy Stone helped to organize the first National Women's Rights Convention in 1850, a much larger event at which Sojourner Truth, Abby Kelley Foster, and others spoke sparked Susan B. Anthony to take up the cause of women's rights. Barbara Leigh Smith met with Mott in 1858,[72] strengthening the link between the transatlantic feminist movements.

Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage saw the Church as a major obstacle to women's rights,[73] and welcomed the emerging literature on matriarchy. Both Gage and Stanton produced works on this topic, and collaborated on The Woman's Bible. Stanton wrote "The Matriarchate or Mother-Age"[74] and Gage wrote Woman, Church and State, neatly inverting Johann Jakob Bachofen's thesis and adding a unique epistemological perspective, the critique of objectivity and the perception of the subjective.[74][jargon]

Stanton once observed regarding assumptions of female inferiority, "The worst feature of these assumptions is that women themselves believe them".[75] However this attempt to replace androcentric (male-centered) theological[clarification needed] tradition with a gynocentric (female-centered) view made little headway in a women's movement dominated by religious elements; thus she and Gage were largely ignored by subsequent generations.[76][77]

By 1913, Feminism (originally capitalized) was a household term in the United States.[78] Major issues in the 1910s and 1920s included suffrage, economics and employment, sexualities and families, war and peace, and a Constitutional amendment for equality. Both equality and difference were seen as routes to women's empowerment.[clarification needed] Organizations at the time included the National Woman's Party, suffrage advocacy groups such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association and the National League of Women Voters, career associations such as the American Association of University Women, the National Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs, and the National Women's Trade Union League, war and peace groups such as the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and the International Council of Women, alcohol-focused groups like the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform, and race- and gender-centered organizations like the National Association of Colored Women. Leaders and theoreticians included Jane Addams, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Alice Paul, Carrie Chapman Catt, Margaret Sanger, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman.[79]

Suffrage

The women's right to vote, with its legislative representation, represented a paradigm shift where women would no longer be treated as second-class citizens without a voice. The women's suffrage campaign is the most deeply embedded campaign of the past 250 years.[80][dubious – discuss]

At first, suffrage was treated as a lower priority. The French Revolution accelerated this,[clarification needed] with the assertions of Condorcet and de Gouges, and the women who led the 1789 march on Versailles. In 1793, the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women was founded, and originally included suffrage on its agenda before it was suppressed at the end of the year. As a gesture, this showed that issue was now part of the European political agenda.[citation needed]

German women were involved in the Vormärz, a prelude to the 1848 revolution. In Italy, Clara Maffei, Cristina Trivulzio Belgiojoso, and Ester Martini Currica were politically active[clarification needed] in the events leading up to 1848. In Britain, interest in suffrage emerged from the writings of Wheeler and Thompson in the 1820s, and from Reid, Taylor, and Anne Knight in the 1840s.[citation needed]

The suffragettes

The Langham Place ladies set up a suffrage committee at an 1866 meeting at Elizabeth Garrett's home, renamed the London Society for Women's Suffrage in 1867.[citation needed] Soon similar committees had spread across the country, raising petitions, and working closely with John Stuart Mill. When denied outlets by establishment periodicals, feminists started their own, such as Lydia Becker's Women's Suffrage Journal in 1870.

Other publications included Richard Pankhurst's Englishwoman's Review (1866).[clarification needed] Tactical disputes were the biggest problem,[clarification needed] and the groups' memberships fluctuated.[clarification needed] Women considered whether men (like Mill) should be involved. As it went, Mill withdrew as the movement became more aggressive with each disappointment.[clarification needed] The political pressure ensured debate, but year after year the movement was defeated in Parliament.

Despite this, the women accrued political experience, which translated into slow progress at the local government level. But after years of frustration, many women became increasingly radicalized. Some refused to pay taxes, and the Pankhurst family emerged as the dominant movement influence, having also founded the Women's Franchise League in 1889, which sought local election suffrage for women.[citation needed]

International suffrage

Template:Details3 The Isle of Man was the first free standing jurisdiction to grant women the vote (1881), followed by New Zealand in 1893, where Kate Sheppard[81] had pioneered reform. Some Australian states had also granted women the vote. This included Victoria for a brief period (1863–5), South Australia (1894), and Western Australia (1899). Australian women received the vote at the Federal level in 1902, Finland in 1906, and Norway initially in 1907 (completed in 1913).[citation needed]

Early 20th century

The early 20th century, the Edwardian era, saw a loosening of Victorian rigidity and complacency: women had more employment opportunities and were more active,[clarification needed] leading to a relaxing of clothing restrictions.[citation needed]

Books, articles, speeches, pictures, and papers from the period show a diverse range of themes other than political reform and suffrage discussed publicly.[citation needed] In the Netherlands, for instance, the main feminist issues were educational rights, rights to medical care,[82] improved working conditions, peace, and dismantled gender double standards.[83][84][85][86][87][88] Feminists identified as such with little fanfare.[citation needed]

The charismatic and controversial[clarification needed] Pankhursts formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. As Emmline Pankhurst put it, they viewed votes for women no longer as "a right, but as a desperate necessity".[This quote needs a citation] At the state level, Australia and the United States had already granted suffrage to some women. American feminists such as Susan B Anthony (1902) visited Britain.[clarification needed] While WSPU was the best-known suffrage group,[citation needed] it was only one of many, such as the Women's Freedom League and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett.[clarification needed] WSPU was largely a family affair,[clarification needed] although externally financed. Christabel Pankhurst became the dominant figure and gathered friends such as Annie Kenney, Flora Drummond, Teresa Billington, Ethel Smythe, Grace Roe, and Norah Dacre Fox (later known as Norah Elam) around her. Veterans such as Elizabeth Garrett also joined.

In 1906, the Daily Mail first labeled these women "suffragettes" as a form of ridicule, but the term was quickly embraced[by whom?] in Britain to describe the more militant form of suffragism visible in public marches, distinctive green, purple, and white emblems, and the Artists' Suffrage League's dramatic graphics. Even underwear in WPSU colors appeared in stores.[citation needed] They feminists learned to exploit photography and the media, and left a vivid visual record including images such as the 1914 photograph of Emmeline.[citation needed] As the movement gained momentum, deep divisions separated the former leaders from the radicals. The splits were usually ideological or tactical.[citation needed] Even Christabel's sister, Sylvia, was expelled.[citation needed]

The protests slowly became more violent, and included heckling, banging on doors, smashing shop windows, and arson. Emily Davison, a WSPU member, unexpectedly ran onto the track during the 1913 Epsom Derby and died under the King's horse. These tactics produced mixed results of sympathy and alienation.[citation needed] As many protesters were imprisoned and went on hunger-strike, the British government was left with an embarrassing situation. From these political actions, the suffragists successfully created publicity around their institutional discrimination and sexism.

Feminist science fiction

At the beginning of the 20th century, feminist science fiction emerged as a sub-genre of science fiction that deals with women's roles in society. Female writers of the utopian literature movement at the time of first-wave feminism often addressed sexism. Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Herland (1915) did so.[clarification needed] Sultana's dream (1905) by Bengali Muslim feminist Roquia Sakhawat Hussain depicts a gender-reversed purdah in a futuristic world.

During the 1920s, writers such as Clare Winger Harris and Gertrude Barrows Bennett published science fiction stories written from female perspectives and occasionally dealt with gender- and sexuality-based topics while popular 1920s and 30s pulp science fiction exaggerated masculinity alongside sexist portrayals of women.[89] By the 1960s, science fiction combined sensationalism with political and technological critiques of society. With the advent of feminism, women's roles were questioned in this "subversive, mind expanding genre".[90]

Feminist science fiction poses questions about social issues such as how society constructs gender roles, how reproduction defines gender, and how the political power of men and women are unequal.[citation needed] Some of the most notable feminist science fiction works have illustrated these themes using utopias to explore societies where gender differences or gender power imbalances do not exist, and dystopias to explore worlds where gender inequalities are intensified, asserting a need for feminist work to continue.[91]

Mid-20th century

Women entered the labor market during the First World War in unprecedented numbers, often in new sectors, and discovered the value of their work. The war also left large numbers of women bereaved and with a net loss of household income. The scores of men killed and wounded shifted the demographic composition. War also split the feminist groups, with many women opposed to the war and others involved in the white feather campaign.[citation needed]

Feminist scholars like Francoise Thebaud and Nancy Cott note a conservative reaction to World War I in some countries, citing a reinforcement of traditional imagery and literature that promotes motherhood. The appearance of these traits in wartime has been called the "nationalization of women".[citation needed]

In the years between the wars, feminists fought discrimination and establishment opposition.[clarification needed] In Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, Woolf describes the extent of the backlash and her frustration at the waste of so much talent.[who?] By now, the word "feminism" was in use, but with a negative connotation from mass media, which discouraged women from self-identifying as such.[citation needed] In 1938, Woolf wrote of the term in Three Guineas, "an old word ... that has much harm in its day and is now obsolete".[This quote needs a citation] When Rebecca West, another prominent writer, had been attacked as "a feminist", Woolf defended her. West has perhaps best been remembered[citation needed] for her comment, "I myself have never been able to find out precisely what feminism is: I only know that people call me a feminist whenever I express sentiments that differentiate me from a doormat, or a prostitute."[92] Woolf's writing also examined gender constructs and portrayed lesbian sexuality positively.

In the 1920s, the nontraditional styles and attitudes of flappers were popular among American and British women.[93]

Electoral reform

The United Kingdom's Representation of the People Act 1918[94][dead link] gave near-universal suffrage to men, and suffrage to women over 30. The Representation of the People Act 1928 extended equal suffrage to both men and women. It also shifted the socioeconomic makeup of the electorate towards the working class, favoring the Labour Party, who were more sympathetic to women's issues.[citation needed] The following election and gave Labour the most seats in the house to date. The electoral reforms also allowed women to run for Parliament. Christabel Pankhurst narrowly failed to win a seat in 1918, but in 1919 and 1920, both Lady Astor and Margaret Wintringham won seats for the Conservatives and Liberals respectively by succeeding their husband's seats. Labour swept to power in 1924. Constance Markievicz (Sinn Féin) was the first woman elected in Ireland in 1918, but as an Irish nationalist, refused to take her seat. Astor's proposal to form a women's party in 1929 was unsuccessful, which some historians[who?] feel was a missed opportunity, as there were only 12 women in Parliament by 1940. Women gained considerable electoral experience over the next few years as a series of minority governments ensured almost annual elections. Close affiliation with Labour also proved to be a problem for the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC), which had little support in the Conservative party. However, their persistence with Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin was rewarded with the passage of the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928.[citation needed]

European women received the vote in Denmark and Iceland in 1915 (full in 1919), the USSR in 1917, Austria, Germany and Canada in 1918, many countries including the Netherlands in 1919, and Turkey and South Africa in 1930. French women did not receive the vote until 1945. Liechtenstein was one of the last countries, in 1984.[95]

The women's movement and social reform

The political change did not immediately change social circumstances. With the economic recession, women were the most vulnerable sector of the workforce. Some women who held jobs prior to the war were obliged to forfeit them to returning soldiers, and others were excessed. With limited franchise, the UK National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) pivoted into a new organization, the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC),[96] which still advocated for equality in franchise, but extended its scope to examine equality in social and economic areas. Legislative reform was sought for discriminatory laws (e.g., family law and prostitution) and over the differences between equality and equity, the accommodations that would allow women to overcome barriers to fulfillment (known in later years as the "equality vs. difference conundrum").[97] Eleanor Rathbone, who became a British Member of Parliament in 1929, succeeded Millicent Garrett as president of NUSEC in 1919. She expressed the critical need for consideration of difference in gender relationships as "what women need to fulfill the potentialities of their own natures".[This quote needs a citation] The 1924 Labour government's social reforms created a formal split, as a splinter group of strict egalitarians formed the Open Door Council in May 1926.[98] This eventually became an international movement, and continued until 1965.[citation needed] Other important social legislation of this period included the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 (which opened professions to women), and the Matrimonial Causes Act 1923. In 1932, NUSEC separated advocacy from education, and continued the former activities as the National Council for Equal Citizenship and the latter as the Townswomen's Guild. The council continued until the end of the Second World War.[citation needed]

In 1921, Margaret Mackworth (Lady Rhondda) founded the Six Point Group,[99] which included Rebecca West. As a political lobby group it aimed at political, occupational, moral, social, economic and legal equality. Thus it was ideologically allied with the Open Door Council, rather than National Council. It also lobbied at an international level, such as the League of Nations, and continued its work till 1983. In retrospect both ideological groups were influential in advancing women's rights in their own way. Despite women being admitted to the House of Commons from 1918, Mackworth, a Viscountess in her own right, spent a lifetime fighting to take her seat in the House of Lords against bitter opposition, a battle which only achieved its goal in the year of her death (1958). This revealed the weaknesses of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act. Mackworth also founded Time and Tide which became the group's journal, and to which West, Virginia Woolf, Rose Macaulay and many others contributed. A number of other women's periodicals also appeared in the 1920s, including Woman and Home, and Good Housekeeping, but whose content reflect very different aspirations. In 1925 Rebecca West wrote in Time and Tide something that reflected not only the movement's need to redefine itself post suffrage, but a continual need for re-examination of goals. "When those of our army whose voices are inclined to coolly tell us that the day of sex-antagonism is over and henceforth we have only to advance hand in hand with the male, I do not believe it."[citation needed]

Reproductive rights

As feminism sought to redefine itself, new issues rose to the surface, one of which was reproductive rights. Even discussing the issue could be hazardous. Annie Besant had been tried in 1877 for publishing Charles Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy, a work on family planning, under the Obscene Publications Act 1857.[100][101] Knowlton had previously been convicted in the United States. She and her colleague Charles Bradlaugh were convicted but acquitted on appeal, the subsequent publicity resulting in a decline in the birth rate.[102][103] Not discouraged in the slightest, Besant followed this with The Law of Population.[104]

Similarly in America, Margaret Sanger was prosecuted for her Family Limitation under the Comstock Act 1873, in 1914, and fled to Britain where she met with Marie Stopes until it was safe for her to return. Sanger continued to risk prosecution, and her work was prosecuted in Britain. Stopes was never prosecuted but was regularly denounced for her work in promoting birth control. In 1917 Sanger started the Birth Control Review.[105] In 1926, Sanger gave a lecture on birth control to the women's auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan in Silver Lake, New Jersey, which she referred to as a "weird experience".[106] Even more controversial was the establishment of the Abortion Law Reform Association in 1936. The penalty for abortion had been reduced from execution to life imprisonment by the Offences against the Person Act 1861, although some exceptions were allowed in the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929.[107][108] Following the prosecution of Dr. Aleck Bourne in 1938, the 1939 Birkett Committee made recommendations for reform, that like many other women's issues, were set aside at the outbreak of the Second World War.[109]

In The Netherlands Aletta H. Jacobs, first Dutch female doctor, and Wilhelmina Drucker were frontwomen in discussing and taking action on the theme reproductive rights. Jacobs started to import pessaria from Germany and gave them out for free to poor women in her praxis.

1940s

In most front line countries, women volunteered or were conscripted for various duties in support of the war effort. In Britain women were drafted and assigned to industrial jobs or to non-combat military service. The British services enrolled 460,000 women. The largest service ATS had a maximum of 213,000 women enrolled, many of whom served in combat roles in anti-aircraft gun emplacements.[110][111] In many countries, such as Germany and the Soviet Union, women volunteered or were conscripted for various duties in support of the war effort. In Germany, women volunteered in the BDM, assisting the Luftwaffe as anti-aircraft gunners, or as guerrilla fighters in Werwolf units behind Allied lines.[112] In the Soviet Union about 820,000 women served in the military as medics, radio operators, or truck drivers, snipers, combat pilots, and junior commanding officers.[113]

The Second World War was involved double duty for many American women—they retained their domestic chores and often added a paid job, especially one related to a war industry. Much more so than in the previous war, large numbers of women were hired for unskilled or semi-skilled jobs in munitions, and barriers against married women taking jobs were eased.The popular icon Rosie the Riveter became a symbol for a generation of American working women. Some 300,000 women served in U.S. military uniform (WAC, WAVES, etc.). With so many young men gone, sports organizers tried to set up pro women's teams, such as the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League; it closed after the war. Indeed most munitions plants closed, and civilian plants replaced the new women with returning veterans, who had priority.[114]

Second-wave feminism

"Second-wave feminism" identifies a period of feminist activity from the early 1960s through the late 1980s. Second-wave feminism has existed continuously since then, and continues to coexist with what some people call "Third Wave Feminism". Second-wave feminism saw cultural and political inequalities as inextricably linked. The movement encouraged women to understand aspects of their personal lives as deeply politicized, and reflective of a sexist structure of power. If first-wavers focused on absolute rights such as suffrage, second-wavers largely concentrated on other issues of equality, such as the end to discrimination.[115]

Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, and the rise of Women's Liberation

In 1963 Betty Friedan published her exposé The Feminine Mystique, giving a voice to the discontent and disorientation many women felt in being shunted into homemaking positions after graduating from college. In the book, Friedan explored the roots of the change in women's roles from essential workforce during World War II to homebound housewife and mother after the war, and assessed the forces that drove this change in perception of women's roles.[citation needed]

Over the following decade, the phrase and concept "Women's Liberation" began to be discussed.[citation needed]

While people sometimes use the expression "Women's Liberation" to refer to feminism throughout history,[116] the term came into use relatively recently. "Liberation" has been associated with women's aspirations since 1895,[117] and appears in the context of "women's liberation" in The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir in 1949, which appeared in English translation in 1953. The phrase "women's liberation" was first used in 1964,[118] and appeared in print in 1966,[119] although the French equivalent, "libération des femmes", occurred as far back as 1911.[120] "Women's liberation" was in use at the 1967 American Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) convention, which held a panel discussion on it. By 1968, although the term "Women's Liberation Front" appeared in "Ramparts", it was starting to refer to the whole women's movement.[121] In Chicago, women disillusioned with the New Left were meeting separately in 1967, and publishing Voice of the Women's Liberation Movement by March 1968. When the Miss America Pageant took place in September 1967, the media referred to the demonstrations as Women's Liberation, and the Chicago Women's Liberation Union was formed in 1969.[122] Similar groups with similar titles appeared in many parts of the United States. Bra-burning (actually a fiction[123]) became associated with the movement, and the media coined other terms such as "libber". "Women's Liberation", compared to various rival terms for the new feminism which co-existed for a while, captured the popular imagination and has persisted, although As of 2013[update] the older term "Women's Movement" occurs just as frequently.[124]

1960s' feminism — and its theory and activism — was informed and fueled by the social, cultural, and political climate of that decade. This was a time when there was an increasing entry of women into higher education, the establishment of academic women's studies courses and departments[125] and feminist thinking in many other related fields such as politics, sociology, history and literature,[18] and a time when there was increasing questioning of accepted standards and authority.[126]

It also became increasingly evident, almost from the beginning, that the Women's Liberation movement consisted of multiple "feminisms" — due to the diverse origins from which groups had coalesced and intersected, and the complexity and contentiousness of the issues involved. Starting in the 1980s, one of the most vocal critics of the whole movement has been bell hooks,[127] who comments on lack of voice by the most oppressed women, glossing over of race and class as inequalities, and failure to address the issues that divided women.[citation needed]

Feminist writing

Following the changes in women's consciousness provoked by Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique, in the 1970s new feminist activists took on more political and sexual issues in their writings.[citation needed]

Feminist writing in the early 1970s ranges from Gloria Steinem (Ms. magazine 1970), to Kate Millett's Sexual Politics.[128] Millett's uses her bleak survey of male writers and their attitudes and biases to demonstrates her thesis that sex is politics, and politics is power imbalance in relationships. Her pessimism is reflected in her description of "the desert we inhabit". From the same period come Shulamith Firestone's The Dialectic of Sex, Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch, Sheila Rowbotham's Women's Liberation and the New Politics and Juliet Mitchell's Woman's Estate, the following year. Firestone based her concept of revolution on Marxism, referred to the "sex war", and interestingly, in view of the debates over patriarchy, claimed that male domination dated to "back beyond recorded history to the animal kingdom itself". Co-founder of Redstockings,[129] Firestone, considered a radical, put "feminism" back in the vocabulary.[130]

Greer, Rowbotham and Mitchell represent an English perspective on the growing revolution, but as Mitchell argues, this should be seen as an international phenomenon, but taking on different manifestations relating to local culture. British women too, drew on left political backgrounds, and organized small local discussion groups. Much of this took Bartplace through the London Women's Liberation Workshop and its publications Shrew and the LWLW Newsletter.[131] Although there were marches, the focus was on what Kathie Sarachild of Redstockings had called consciousness-raising.[118][130] One of the functions of this was, as Mitchell describes it was that women would "find what they thought was an individual dilemma is social predicament". Women found that their own personal experiences were information that they could trust in formulating political analyses.

Meanwhile in the U.S., women's frustrations crystallized around the failure to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment during the 1970s. Against this background appeared Susan Brownmiller's Against Our Will in 1975, introducing a more explicit agenda directed against male violence, specifically male sexual violence in a treatise on rape. Perhaps her most memorable phrase was "pornography is the theory and rape the practice", creating a nexus that would cause deep fault lines to develop,[132] largely around the concepts of objectification[133] and commodification. Brownmiller's other major contribution is In our Time (2000), a history of women's liberation. Less well known is Femininity (1984) a gentler deconstruction of a concept that has had an uneasy relationship with feminism.[134]

Feminist views on pornography

One of the first women to develop the further implications of pornography was Susan Griffin in Pornography and Silence (1981). Moving beyond Brownmiller and Griffin's positions are Catharine MacKinnon, and Andrea Dworkin with whom she collaborated. Their influence in debates and activism on pornography and prostitution has been striking, in particular at the Supreme Court of Canada.[135] MacKinnon, who is a lawyer, has stated: "To be about to be raped is to be gender female in the process of going about life as usual."[136] Sexual harassment, she says "doesn't mean that they all want to fuck us, they just want to hurt us, dominate us, and control us, and that is fucking us."[137] Some see radical feminism as the only movement that truly expresses the pain of being a woman in an unequal society, and that portrays that reality through the experiences of the battered and violated, which they claim to be the norm.[138] To critics, including some feminists, civil libertarians and jurists, this position is uncomfortable and alienating.[3][139][140]

A useful evolution of this approach has been to transform the research and perspective on rape from an individual experience to a social problem.[141]

Third-wave feminism

The Third-wave of feminism began in the early 1990s. The movement arose as responses to what young women thought of as perceived failures of the second-wave. It was also a response to the backlash against initiatives and movements created by the second-wave. Third-wave feminism seeks to challenge or avoid what it deems the second wave's "essentialist" definitions of femininity, which (according to them) over-emphasized the experiences of upper middle class white women. A post-structuralist interpretation of gender and sexuality is central to much of the third wave's ideology. Third wave feminists often focus on "micropolitics", and challenged the second wave's paradigm as to what is, or is not, good for females.[115][142][143][144]

The history of Third Wave feminism predates this and begins in the mid-1980s. Feminist leaders rooted in the second wave like Gloria Anzaldúa, bell hooks, Chela Sandoval, Cherríe Moraga, Audre Lorde, Luisa Accati, Maxine Hong Kingston, and many other feminists of color, called for a new subjectivity in feminist voice. They sought to negotiate prominent space within feminist thought for consideration of race related subjectivities. This focus on the intersection between race and gender remained prominent through the Hill-Thomas hearings, but began to shift with the Freedom Ride 1992. This drive to register voters in poor minority communities was surrounded with rhetoric that focused on rallying young feminists. For many, the rallying of the young is the emphasis that has stuck within third wave feminism.[115][142]

Sexual politics

Queer sexuality

One challenge within second wave feminism was the increasing visibility of lesbianism within and without feminism. Lesbians felt sidelined by both gay liberation and women's liberation, where they were referred to as the "Lavender Menace", provoking The Woman-Identified Woman from the Radicalesbians in 1970. Jill Johnston's Lesbian Nation: The Feminist Solution followed in 1973. Many lesbians felt that they should be central to the movement, representing a fundamental threat to male supremacy. In its extreme form this was expressed as the only appropriate choice for a woman. One of the more colourful lesbian feminist writers of this period was Rita Mae Brown. Eventually the lesbian movement was welcomed into the mainstream women's movement. The threat to male assumptions they represented turned out to be real in that their presence in the woman's movement became a target of the male backlash.[citation needed]

Reproductive rights

One of the main fields of interest to these feminists was in gaining the right to contraception and birth control, which were almost universally restricted until the 1960s. With the development of the first birth control pill feminists hoped to make it as available as soon as possible. Many hoped that this would free women from the perceived burden of mothering children they did not want; they felt that control of reproduction was necessary for full economic independence from men. Access to abortion was also widely demanded, but this was much more difficult to secure because of the deep societal divisions that existed over the issue. To this day, abortion remains controversial in many parts of the world.[citation needed]

Many feminists also fought to change perceptions of female sexual behaviour. Since it was often considered more acceptable for men to have multiple sexual partners, many feminists encouraged women into "sexual liberation" and having sex for pleasure with multiple partners. (See: Sexual revolution)

These developments in sexual behavior have not gone without criticism by some feminists.[citation needed] They see the sexual revolution primarily as a tool used by men to gain easy access to sex without the obligations entailed by marriage and traditional social norms.[citation needed] They see the relaxation of social attitudes towards sex in general, and the increased availability of pornography without stigma, as leading towards greater sexual objectification of women by men.[citation needed]

Global feminism

Immediately after the war a new global dimension was added by the formation of the United Nations. In 1946 the UN established a Commission on the Status of Women.[145][146] Originally as the Section on the Status of Women, Human Rights Division, Department of Social Affairs, and now part of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). In 1948 the UN issued its Universal Declaration of Human Rights[147] which protects "the equal rights of men and women", and addressed both the equality and equity issues. Since 1975 the UN has held a series of world conferences on women's issues, starting with the World Conference of the International Women's Year in Mexico City, heralding the United Nations Decade for Women (1975–85). These have brought women together from all over the world and provided considerable opportunities for advancing women's rights, but also illustrated the deep divisions in attempting to apply principles universally,[148] in successive conferences in Copenhagen (1980) and Nairobi (1985). However by 1985 some convergence was appearing. These divisions amongst feminisms included; First World vs. Third World, the relationship between gender oppression and oppression based on class, race and nationality, defining core common elements of feminism vs. specific political elements, defining feminism, homosexuality, female circumcision, birth and population control, the gulf between researchers and the grass roots, and the extent to which political issues were women's issues. Emerging from Nairobi was a realisation that feminism is not monolithic but "constitutes the political expression of the concerns and interests of women from different regions, classes, nationalities, and ethnic backgrounds. There is and must be a diversity of feminisms, responsive to the different needs and concerns of women, and defined by them for themselves. This diversity builds on a common opposition to gender oppression and hierarchy which, however, is only the first step in articulating and acting upon a political agenda."[149] The fourth conference was held in Beijing in 1995.[150] At this conference a the Beijing Platform for Action was signed. This included a commitment to achieve "gender equality and the empowerment of women".[151] The most important strategy to achieve this was considered to be "gender mainstreaming" which incorporates both equity and equality, that is that both women and men should "experience equal conditions for realising their full human rights, and have the opportunity to contribute and benefit from national, political, economic, social and cultural development".[152]

Later development

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2013) |

A few since 2008 believe that we are or may be in a fourth wave of feminism.[153][154][155][156][157]

National histories of feminism

France

In the 18th century, the French Revolution focussed people's attention everywhere on the cry for "égalité", and hence by extension, but in a more limited way, inequity in the treatment of women. In 1791, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen elicited an immediate response from the writer Olympe de Gouges who amended it as the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, arguing that if women were accountable to the law they must also be given equal responsibility under the law. She also addressed marriage as a social contract between equals and attacked women's reliance on beauty and charm as a form of slavery.[158]

During the 19th century, conservative postrevolutionary France was not a favourable climate for feminist ideas, as expressed in the counter-revolutionary writings on the role of women by Joseph de Maistre and Viscount Louis de Bonald. Advancement would have to wait for the revolution of 24 February 1848, and the proclamation of the Second Republic which introduced male suffrage, and hopes that similar benefits would apply to women. Although the Utopian Charles Fourier is considered a feminist writer of this period, his influence was minimal at the time.[159]

In France, with the fall of the conservative Louis-Philippe in 1848, feminist hopes were raised, as in 1790. Several newspapers and organizations appeared. Eugénie Niboyet (1800–1883) founded La Voix des Femmes (The Women's Voice), as the first feminist daily newspaper in France 'a socialist and political journal, the organ of the interests of all women'. Niboyet was a Protestant who had adopted Saint-Simonianism, and La Voix attracted other women from that movement, including the seamstress Jeanne Deroin and the primary schoolteacher Pauline Roland. Unsuccessful attempts were also made to recruit George Sand. The enthusiasm was short lived; feminism which was allied with socialism was seen as a threat as it had been under the previous revolution, Deroin and Roland were both arrested, tried and imprisoned in 1849. With the emergence of a new, more conservative government in 1852, feminism would have to wait until the Third French Republic.

The Groupe Français d'Etudes Féministes were women intellectuals at the beginning of the 20th century who translated part of Bachofen's cannon into French,[160] and campaigned for the reform of family law. In 1905 they founded L'entente which published articles on women's history, and became the focus for the intellectual avant garde advocating higher education for women and entry into the male-dominated professions.[161] Meanwhile socialist feminists, the Parti Socialiste Féminin, adopted a Marxist version of matriarchy. But like the Groupe Français, they saw the struggle as being for a new age of equality, not a return to some kind of prehistorical matriarchy.[162][163] French feminism of the late 20th century is mainly associated with the psychoanalytical Feminist theory, notably with the thinking of Luce Irigaray, Julia Kristeva and Hélène Cixous.[164]

Germany

The organized German women's movement is widely attributed to writer and feminist Louise Otto-Peters (1819-1895).

Iran

The Iranian women's movement, involves Iranian women's social movement for women's rights. The movement first emerged, some time after Iranian Constitutional Revolution, in 1910, the year in which the first Women Journal was published by women. The movement lasted until 1933 in which the last women's association was dissolved by the Reza Shah's government. It heightened again after the Iranian Revolution (1979). The most important feminist figures in this time are Bibi Khanoom Astarabadi, Touba Azmoudeh, Sediqeh Dowlatabadi, Mohtaram Eskandari, Roshank No'doost, Afaq Parsa, Fakhr ozma Arghoun, Shahnaz Azad, Noor-ol-Hoda Mangeneh (1902-?), Zandokht Shirazi, Maryam Amid (Mariam Mozayen-ol Sadat).[165][166]

After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the status of women quickly deteriorated. With passage of time, many of the rights that women had gained under Shah, were systematically abolished, through legislation, elimination of women from work, and of course forced Hejab.[167]

In 1992, Shahla Sherkat founded Zanan (Women) magazine, which focused on the concerns of Iranian women and tested the political waters with its edgy coverage of reform politics, domestic abuse, and sex. It is the most important Iranian women's journal published after the Iranian revolution, systematically criticizing the Islamic legal code. It argues that gender equality is Islamic and that religious literature has been misread and misappropriated by misogynists. Mehangiz Kar, Shahla Lahiji, and Shahla Sherkat, the editor of Zanan, lead the debate on women's rights and demanded reforms.[168] On August 27, 2006, a new women's rights campaign was launched in Iran. The One Million Signatures campaign aims to end legal discrimination against women in Iranian laws by collecting a million signatures. The supporters of this campaign include many Iranian women's rights activists and also international activists as well as many Nobel laureates.[169] The most important after revolution feminist figures are Mehrangiz Kar, Azam Taleghani, Shahla Sherkat, Parvin Ardalan, Noushin Ahmadi khorasani, Shadi Sadr.

Egypt

In 1899, Qasim Amin, considered the "father" of Arab feminism, wrote The Liberation of Women, which argued for legal and social reforms for women.[170] Hoda Shaarawi founded the Egyptian Feminist Union in 1923, and became its president and a symbol of the Arab women's rights movement. Arab feminism was closely connected with Arab nationalism.[171] In 1956, President Nasser initiated as part of his government "state feminism", which outlawed discrimination based on gender and granted women's suffrage. Despite these reforms, "state feminism" blocked political activism by feminist leaders and brought an end to the first-wave feminist movement in Egypt.[172] During Sadat's presidency, his wife, Jehan Sadat, publicly advocated for further women's rights, though Egyptian policy and society began to move away from women's equality with the new Islamist movement and growing conservatism. However, writers such as Al Ghazali Harb, for example, argued that women's full equality is an important part of Islam.[173] This position formed a new feminist movement, Islamic feminism, which is still active today.[174]

India

With the rise of feminism across the world, a new generation of Indian feminists has emerged. Women have developed themselves according to the situations and have become advanced in various fields.[clarification needed] They have become independent in respect of their reproductive rights.[175] Contemporary Indian feminists are fighting for and against: individual autonomy, rights, freedom, independence, tolerance, cooperation, nonviolence and diversity, domestic violence, gender, stereotypes, sexuality, discrimination, sexism, non-objectification, freedom from patriarchy, the right to an abortion, reproductive rights, control of the female body, the right to a divorce, equal pay, maternity leave, breast feeding, prostitution, and education. Medha Patkar, Madhu Kishwar, and Brinda Karat are feminist social workers and politicians who advocate women's rights in post-independent India.[175] Writers such as Amrita Pritam, Sarojini Sahoo and Kusum Ansal advocate feminist ideas in Indian languages. Rajeshwari Sunder Rajan, Leela Kasturi, Sharmila Rege, and Vidyut Bhagat are Indian feminist essayists and critics writing in English.

China

Feminism in China begun in the late Qing period, as Chinese society re-evaluated traditional and Confucian values such as foot binding and gender segregation, and began to reject traditional gender ideas as hindering progress towards modernization.[176] During the 1898 Hundred Days' Reform, reformers called for women's education and equality, and the end of foot binding. Female reformers formed the first Chinese women's society—the Society for the Diffusion of Knowledge among Chinese Women (Nüxuehuao).[177] After the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, women's liberation became a goal of the May Fourth Movement and the New Culture Movement.[178] Later, the Chinese Communist Revolution adopted women's liberation as one of its aims and promoted women's equality, especially regarding women's participation in the workforce. After the revolution and progress in integrating women into the workforce, the Chinese Communist Party claimed to have successfully achieved women's liberation, and women's inequality was no longer seen as a problem.[179]

Second and third-wave feminism in China was characterized by a re-examination of women's roles during the reform movements of the early 20th century and the way in which feminism was adopted by those various movements in order to achieve their goals. Later and current feminists have questioned whether gender equality has actually been fully achieved, and discuss current gender problems, such as the large gender disparity in the population.[179]

Japan

Japanese feminism as an organized political movement dates back to the early years of the 20th century, when Kato Shidzue pushed for birth-control availability as part of a broad spectrum of progressive reforms. Shidzue went on to serve in the National Diet following the defeat of Japan in World War II and the promulgation of the Peace Constitution by US forces.[180] Other figures such as Hayashi Fumiko and Ariyoshi Sawako illustrate the broad socialist ideologies of Japanese feminism, that seeks to accomplish broad goals rather than celebrate the individual achievements of powerful women.[180][181]

Norway

Feminism in Norway has its political origins in the movement for women's suffrage. Women's issues were first articulated in the public sphere by Camilla Collett (1813–1895), widely considered the first Norwegian feminist. Originating from a literary family, she wrote a novel and several articles on the difficulties facing women of her time, and in particular forced marriages. Amalie Skram (1846–1905) also gave voice to a woman's point of view with her naturalist writing.[182]

The Norwegian Association for Women's Rights was founded in 1884 by Gina Krog and Hagbart Berner. The organization raised issues related to women's rights to education and economic self-determination, and above all, universal suffrage. Women's right to vote was passed by law, June 11, 1913, by the Norwegian Parliament. Norway was the second country in Europe after Finland to have full suffrage for women.[182]

Poland

The development of feminism in Poland and Polish territories[183] has traditionally been divided into seven successive "waves".[184]

The 1920s saw the emergence of radical feminism in Poland. Its representatives, Irena Krzywicka and Maria Morozowicz-Szczepkowska, advocated women's independence from men. Krzywicka and Tadeusz Żeleński both promoted planned parenthood, sexual education, rights to divorce and abortion, and equality of sexes. Krzywicka published a series of articles in Wiadomości Literackie in which she protested against interference by the Roman Catholic Church in the intimate lives of Poles.[184]

After the Second World War, the Polish Communist state (established in 1948) forcefully promoted women's emancipation at home and at work. However, during Communist rule (until 1989), feminism in general, and second-wave feminism in particular, were practically absent. Although feminist texts were produced in the 1950s and afterwards, they were usually controlled and generated by the Communist state.[185] After the fall of Communism, the Polish government, dominated by ‘pro-Catholic’ political parties, introduced a de facto legal ban on abortions. Since then some feminists have adopted argumentative strategies borrowed from the American ‘Pro-Choice’ movement of the 1980s.[184]

Ukrainian protests

FEMEN is a Ukrainian feminist protest group based in Kiev, founded in 2008 by Anna Hutsol. The organization became internationally known for controversial[186] topless protests against sex tourists, religious institutions, international marriage agencies, sexism and other social, national and international topics.[187][188][189][190][191][192][193][194][195][196][197][198][199][200]

History of selected feminist issues

The history of feminist theory

Nancy Cott draws a distinction between modern feminism and its antecedents, particularly the struggle for suffrage. In the United States she places the turning point in the decades before and after women obtained the vote in 1920 (1910–30). She argues that the prior woman movement was primarily about woman as a universal entity, whereas over this 20-year period it transformed itself into one primarily concerned with social differentiation, attentive to individuality and diversity. New issues dealt more with woman's condition as a social construct, gender identity, and relationships within and between genders. Politically this represented a shift from an ideological alignment comfortable with the right, to one more radically associated with the left.[201]

In the immediate postwar period, Simone de Beauvoir stood in opposition to an image of "the woman in the home". De Beauvoir provided an existentialist dimension to feminism with the publication of Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex) in 1949.[202] While more philosopher and novelist than activist, she did sign one of the Mouvement de Libération des Femmes manifestos. The resurgence of feminist activism in the late 1960s was accompanied by an emerging literature of what might be considered female associated issues, such as concerns for the earth and spirituality, and environmental activism.[203] This in turn created an atmosphere conducive to reigniting the study of and debate on matricentricity, as a rejection of determinism, such as Adrienne Rich[204] and Marilyn French[205] while for socialist feminists like Evelyn Reed,[206] patriarchy held the properties of capitalism.

Elaine Showalter describes the development of Feminist theory as having a number of phases. The first she calls "feminist critique" – where the feminist reader examines the ideologies behind literary phenomena. The second Showalter calls "Gynocritics" – where the "woman is producer of textual meaning" including "the psychodynamics of female creativity; linguistics and the problem of a female language; the trajectory of the individual or collective female literary career [and] literary history". The last phase she calls "gender theory" – where the "ideological inscription and the literary effects of the sex/gender system" are explored."[207] This model has been criticized by Toril Moi who sees it as an essentialist and deterministic model for female subjectivity. She also criticized it for not taking account of the situation for women outside the west.[208]

Sociology of the family debate

Ann Taylor Allen[6] describes the striking gulf between the collective male pessimism and fin-du-siècle angst of male intellectuals such as Ferdinand Tönnies, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel, at the beginning of the 20th century,[209] compared to the optimism of their female counterparts, whose contributions have largely been ignored by social historians of the era.[210] Feminists were well aware of Weber's "iron cage", it is just that they saw it as a starting point, not a finishing point.[citation needed]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the sociology of the family was one of the more prominent concerns of feminist theorists, who have been incorrectly typified as accepting the historical fact of primal matriarchy, whereas their interest was more in an empowering symbolism in interpreting the social issues they confronted. They used Bachofen and the rejection of an inevitable patriarchy to address family law reform and sexual morality. Feminists were sceptical about the objectivity of those who wrote about objective culture, as expressed in their perceived androcentricity. Jeanne Oddo-Deflou, leader of Groupe Français d'Etudes Féministes, went so far as to state that male rejection of Bachofen by male intellectuals was good enough reasons for females to embrace him. She rejected the emotion-rationalism dichotomy association with matriarchy and patriarchy, and with Stanton, asserted that rationality was as much an attribute of any mother-age civilisation as of patriarchy, and that it was mainly patriarchal behavior that was logically irrational.[211]

In English academic circles, the challenge to patriarchy started to permeate a variety of disciplines. Jane Ellen Harrison, a classicist, working from Friedrich Nietzsche's Bachofen inspired interpretation view of Greek culture[212] argued that it was a shift in Pantheons that influenced the loss of matrilineal Greek culture with its more "primitive" pantheistic deities to a patriarchate both on Olympus and on Earth.[213] Many other feminist theorists incorporated matriarchal approaches. These include the American Charlotte Perkins Gilman and British Frances Swiney. Gilman developed the idea of matriarchate as imaginative, pointing out how the trivial male role of fertilisation was responsible for "arresting the development of half the world"[214] and depicts how rationality and emotionality can co-exist harmoniously in her utopian novel Herland.[215]

Swiney used Bachofen's work and his successors, such as Mona Caird, in addressing the social concerns of suffragettes, including sexually transmitted disease, infant mortality and prostitution, and founded a group, the League of Isis that produced a number of empowering works. These women's work in turn would be popularized by the reform minded periodicals of the time (such as The Suffragette, The Vote, The Malthusian, Westminster Review).[216]

More controversial, was the way these views were used to uphold or challenge the standards of sexual morality,[217][218] which were very asymmetrical. Generally British writers upheld the standards but expected them to apply to men equally, while in the Netherlands and Germany they were challenged.[citation needed]

While the majority of feminists supported enforcement of paternal responsibility, the minority used the more radical matriliny argument that support of mothers and children was a state responsibility, and that women should not be humiliated by pursuing fathers. In Holland this was the Vrije Vrouwen (Free Women), through their journal Evolutie, edited by Wilhelmine Drucker in the 1890s.[219] In Germany Ruth Bré (Elisabeth Bouness) founded the Bund für Mutterschutz (League for the Protection of Mothers) in 1905, and took this further advocating a matriarchal society of single mothers, while the league attracted many prominent reformers, female and male, including Helene Stöcker, Lily Braun and Henriette Fürth, they did not support her radicalism, believing that the genders should not be separated in a more evolved social model.[220]

However all groups supported equality of rights. The inspiration for these views came largely from Ellen Key in Sweden who believed that matrilineality was closest to nature.[221][222] The Bund für Mutterschutz advanced the "New Ethic" of women controlling their own sexual and reproductive needs,[219] as a creative and life providing force. For instance Fürth believed that motherhood transcended marriage.[223] Disproportionate to their numerical size, these sexual radicals set a new agenda for the discussion of morality in the west.[224] Understandably, many saw these new ideas as alarming, and threatening.[citation needed]

The moderate majority is represented by groups such as the Bund Deutscher Frauenvereine (League of German Women's Organizations) led by Marianne Weber (who was married to Max Weber), and who warned against belief in "lost paradise".[225] Weber repudiated Bachofen in her ‘’Wife and Mother in Legal History’’ along socialist interpretations, distinguishing between matrilineality and the status of women. Interestingly she argued for marriage to protect the status of children, without doubting the need for this in the first place.[226] However she also rejected the inevitability of the status quo, portrayed further evolution to equality, reform of family law, and although describing monogamy as an ideal, went so far to suggest it was not for everyone, and that non-monogamous relationships were not immoral, views she shared with her husband.[citation needed]

In France, Madeleine Pelletier was equally sceptical about historical patriarchy, but more so some of her colleagues flowery symbolism which she suspected was actually confining. In a foreshadowing of Betty Friedan she pithily summed up the hiatus between male worship of the goddess and emancipation "Future societies may build temples to motherhood, but only to lock women into them."[227] She also held, what for those times were radical views on the need for women to control their reproductive rights.[citation needed]

In striking contrast to Freudian theory is his contemporary feminist Catherine Gasquoine Hartley, whose The Truth about Woman[228] appeared in the same year as Totem and Taboo, based on the same material. To Hartley (also known as Mrs Walter Gallichan), Atkinson's readings were biased, and that it could easily have been the actions of women opposing patriarchy that brought about matriarchy, if only short lived. But to her patriarchy was equally unstable, and she saw the latter day women's movement as one restoring social justice. "It is the day of experiments... We are questioning where before we have accepted, and are seeking out new ways in which mankind will go... will go because it must".[229]

However, despite all of these disagreements, there were common elements, an acceptance of some form of nonpatrilineal kinship in the past, the evolution of family kinship structures, and a belief in the evanescent nature of the status quo. Common to both male and female socialist writers were challenges to traditional views of family, this includes Gilman, Braun, Fürth and Alice Melvin.[230]