Pokémon

| Pokémon | |

|---|---|

Logo of Pokémon for its international releases; Pokémon is short for the original Japanese title of Pocket Monsters | |

| Created by | Satoshi Tajiri Ken Sugimori |

| Original work | Pocket Monsters Red and Green (1996) |

| Owner | Nintendo Creatures Game Freak |

| Print publications | |

| Short stories | Pokémon Junior |

| Comics | Various Pokémon manga |

| Films and television | |

| Film(s) | See list of Pokémon films |

| Short film(s) | Various Pikachu shorts |

| Animated series | Pokémon (anime) (1997–present) Pokémon Chronicles (2006) |

| Television special(s) | Mewtwo Returns (2000) The Legend of Thunder (2001) The Mastermind of Mirage Pokémon (2006) |

| Television film(s) | Pokémon Origins (2013) |

| Theatrical presentations | |

| Musical(s) | Pokémon Live! (2000) |

| Games | |

| Traditional | Pokémon Trading Card Game Pokémon Trading Figure Game |

| Video game(s) | Pokémon video game series Super Smash Bros. |

| Audio | |

| Soundtrack(s) | Pokémon 2.B.A. Master (1999) See also list of Pokémon theme songs |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Theme park | Poképark |

| Official website | |

Pokémon (Japanese: ポケモン, Hepburn: Pokemon, English: /ˈpoʊkɪˌmɒn, -ki-, -keɪ-/),[1][2][3] also known as Pocket Monsters (ポケットモンスター) in Japan, is a media franchise managed by The Pokémon Company, a Japanese consortium between Nintendo, Game Freak, and Creatures.[4] The franchise copyright is shared by all three companies, but Nintendo is the sole owner of the trademark.[5] The franchise was created by Satoshi Tajiri in 1995,[6] and is centered on fictional creatures called "Pokémon", which humans, known as Pokémon Trainers, catch and train to battle each other for sport. The English slogan for the franchise is "Gotta Catch 'Em All".[7][8] Works within the franchise are set in the Pokémon universe.

The franchise began as Pokémon Red and Green (released outside of Japan as Pokémon Red and Blue), a pair of video games for the original Game Boy that were developed by Game Freak and published by Nintendo in February 1996. Pokémon has since gone on to become the highest-grossing media franchise of all time,[9][10][11] with $90 billion in total franchise revenue.[12][13] The original video game series is the second best-selling video game franchise (behind Nintendo's Mario franchise)[14] with more than 300 million copies sold[15] and over 800 million mobile downloads,[16] and it spawned a hit anime television series that has become the most successful video game adaptation[17] with over 20 seasons and 1,000 episodes in 124 countries.[15] In addition, the Pokémon franchise includes the world's top-selling toy brand,[18] the top-selling trading card game[19] with over 25.7 billion cards sold,[15] an anime film series, a live-action film, books, manga comics, music, and merchandise. The franchise is also represented in other Nintendo media, such as the Super Smash Bros. series.

In November 2005, 4Kids Entertainment, which had managed the non-game related licensing of Pokémon, announced that it had agreed not to renew the Pokémon representation agreement. The Pokémon Company International oversees all Pokémon licensing outside Asia.[20] The franchise celebrated its tenth anniversary in 2006.[21] In 2016, The Pokémon Company celebrated Pokémon's 20th anniversary by airing an ad during Super Bowl 50 in January, issuing re-releases of Pokémon Red and Blue and the 1998 Game Boy game Pokémon Yellow as downloads for the Nintendo 3DS in February, and redesigning the way the games are played.[22][23] The mobile augmented reality game Pokémon Go was released in July.[24] The latest games in the main series, Pokémon: Let's Go, Pikachu! and Let's Go, Eevee!, were released worldwide on the Nintendo Switch on November 16, 2018. The first live action film in the franchise Pokémon: Detective Pikachu, based on Detective Pikachu, began production in January 2018[25] and is set to release in 2019.[9]

Name

The name Pokémon is the romanized contraction of the Japanese brand Pocket Monsters (ポケットモンスター, Poketto Monsutā).[26] The term "Pokémon", in addition to referring to the Pokémon franchise itself, also collectively refers to the 809 fictional species that have made appearances in Pokémon media as of the release of the seventh generation titles Pokémon: Let's Go, Pikachu! and Let's Go, Eevee! "Pokémon" is identical in the singular and plural, as is each individual species name; it is grammatically correct to say "one Pokémon" and "many Pokémon", as well as "one Pikachu" and "many Pikachu".[27]

Concept

Pokémon executive director Satoshi Tajiri first thought of Pokémon, albeit with a different concept and name, around 1989, when the Game Boy was released. The concept of the Pokémon universe, in both the video games and the general fictional world of Pokémon, stems from the hobby of insect collecting, a popular pastime which Tajiri enjoyed as a child.[28] Players are designated as Pokémon Trainers and have three general goals: to complete the regional Pokédex by collecting all of the available Pokémon species found in the fictional region where a game takes place, to complete the national Pokédex by transferring Pokémon from other regions, and to train a team of powerful Pokémon from those they have caught to compete against teams owned by other Trainers so they may eventually win the Pokémon League and become the regional Champion. These themes of collecting, training, and battling are present in almost every version of the Pokémon franchise, including the video games, the anime and manga series, and the Pokémon Trading Card Game.

In most incarnations of the Pokémon universe, a Trainer who encounters a wild Pokémon is able to capture that Pokémon by throwing a specially designed, mass-producible spherical tool called a Poké Ball at it. If the Pokémon is unable to escape the confines of the Poké Ball, it is considered to be under the ownership of that Trainer. Afterwards, it will obey whatever commands it receives from its new Trainer, unless the Trainer demonstrates such a lack of experience that the Pokémon would rather act on its own accord. Trainers can send out any of their Pokémon to wage non-lethal battles against other Pokémon; if the opposing Pokémon is wild, the Trainer can capture that Pokémon with a Poké Ball, increasing their collection of creatures. In Pokémon Go, and in Pokémon: Let's Go, Pikachu! and Let's Go, Eevee!, wild Pokémon encountered by players can be caught in Poké Balls, but generally cannot be battled. Pokémon already owned by other Trainers cannot be captured, except under special circumstances in certain side games. If a Pokémon fully defeats an opponent in battle so that the opponent is knocked out ("faints"), the winning Pokémon gains experience points and may level up. Beginning with Pokémon X and Y, experience points are also gained from catching Pokémon in Poké Balls. When leveling up, the Pokémon's battling aptitude statistics ("stats", such as "Attack" and "Speed") increase. At certain levels, the Pokémon may also learn new moves, which are techniques used in battle. In addition, many species of Pokémon can undergo a form of metamorphosis and transform into a similar but stronger species of Pokémon, a process called evolution; this process occurs spontaneously under differing circumstances, and is itself a central theme of the series. Some species of Pokémon may undergo a maximum of two evolutionary transformations, while others may undergo only one, and others may not evolve at all. For example, the Pokémon Pichu may evolve into Pikachu, which in turn may evolve into Raichu, following which no further evolutions may occur. Pokémon X and Y introduced the concept of "Mega Evolution", by which certain fully evolved Pokémon may temporarily undergo a third evolution into a stronger form for the purpose of battling; this evolution reverses following the end of the battle.

In the main series, each game's single-player mode requires the Trainer to raise a team of Pokémon to defeat many non-player character (NPC) Trainers and their Pokémon. Each game lays out a somewhat linear path through a specific region of the Pokémon world for the Trainer to journey through, completing events and battling opponents along the way (including foiling the plans of an 'evil' team of Pokémon Trainers who serve as antagonists to the player). Excluding Pokémon Sun and Moon and Pokémon Ultra Sun and Ultra Moon, the games feature eight powerful Trainers, referred to as Gym Leaders, that the Trainer must defeat in order to progress. As a reward, the Trainer receives a Gym Badge, and once all eight badges are collected, the Trainer is eligible to challenge the region's Pokémon League, where four talented trainers (referred to collectively as the "Elite Four") challenge the Trainer to four Pokémon battles in succession. If the trainer can overcome this gauntlet, they must challenge the Regional Champion, the master Trainer who had previously defeated the Elite Four. Any Trainer who wins this last battle becomes the new champion.

Video games

Generations

All of the licensed Pokémon properties overseen by The Pokémon Company International are divided roughly by generation. These generations are roughly chronological divisions by release; every several years, when a sequel to the 1996 role-playing video games Pokémon Red and Green is released that features new Pokémon, characters, and gameplay concepts, that sequel is considered the start of a new generation of the franchise. The main Pokémon video games and their spin-offs, the anime, manga, and trading card game are all updated with the new Pokémon properties each time a new generation begins.[citation needed] Some Pokémon from the newer games appear in anime episodes or films months, or even years, before the game they were programmed for came out. The first generation began in Japan with Pokémon Red and Green on the Game Boy. The franchise began the seventh generation on November 18, 2016 with Pokémon Sun and Moon on the Nintendo 3DS.[30] The most recent games in the main series, Pokémon: Let's Go, Pikachu! and Let's Go, Eevee!, were released on the Nintendo Switch on November 16, 2018. Pokémon Sword and Shield will begin the eighth generation on the Nintendo Switch and are scheduled to be released in late 2019.[31][32][33]

In other media

Anime series

Pokémon, also known as Pokémon the Series, is an anime television series based on the Pokémon video game series. It was originally broadcast on TV Tokyo in 1997. As of 2018[update] it has produced and aired over 1,000 episodes, divided into 6 series in Japan and 21 seasons internationally.

The anime follows the quest of the main character, Ash Ketchum (known as Satoshi in Japan), a Pokémon Master in training, as he and a small group of friends travel around the world of Pokémon along with their Pokémon partners.[34]

Various children's books, collectively known as Pokémon Junior, are also based on the anime.[35]

Films

In addition to the TV series, as of January 2019[update], 22 animated Pokémon films have been directed by Kunihiko Yuyama and Tetsuo Yajima, and distributed in Japan by Toho since 1998. The pair of films, Pokémon the Movie: Black—Victini and Reshiram and White—Victini and Zekrom are considered together as one film. Collectibles, such as promotional trading cards, have been available with some of the films.

Live-action film

A live-action Pokémon film directed by Rob Letterman, produced by Legendary Entertainment,[36] and distributed in Japan by Toho and internationally by Warner Bros.[37] began filming in January 2018.[25] On August 24, the film's official title was announced as Pokémon: Detective Pikachu.[38] It is set for release on May 10, 2019.[9]

Soundtracks

Pokémon CDs have been released in North America, some of them in conjunction with the theatrical releases of the first three and the 20th Pokémon films. These releases were commonplace until late 2001. On March 27, 2007, a tenth anniversary CD was released containing 18 tracks from the English dub; this was the first English-language release in over five years. Soundtracks of the Pokémon feature films have been released in Japan each year in conjunction with the theatrical releases. In 2017, a soundtrack album featuring music from the North American versions of the 17th through 20th movies was released.

| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| June 29, 1999[39] | Pokémon 2.B.A. Master |

| November 9, 1999[40] | Pokémon: The First Movie |

| February 8, 2000 | Pokémon World |

| May 9, 2000 | Pokémon: The First Movie Original Motion Picture Score |

| July 18, 2000 | Pokémon: The Movie 2000 |

| Unknown1 | Pokémon: The Movie 2000 Original Motion Picture Score |

| January 23, 2001 | Totally Pokémon |

| April 3, 2001 | Pokémon 3: The Ultimate Soundtrack |

| October 9, 2001 | Pokémon Christmas Bash |

| March 27, 2007 | Pokémon X: Ten Years of Pokémon |

| November 12, 2013 | Pokémon X & Pokémon Y: Super Music Collection |

| December 10, 2013 | Pokémon FireRed & Pokémon LeafGreen: Super Music Collection |

| January 14, 2014 | Pokémon HeartGold & Pokémon SoulSilver: Super Music Collection |

| February 11, 2014 | Pokémon Ruby & Pokémon Sapphire: Super Music Collection |

| March 11, 2014 | Pokémon Diamond & Pokémon Pearl: Super Music Collection |

| April 8, 2014 | Pokémon Black & Pokémon White: Super Music Collection |

| May 13, 2014 | Pokémon Black 2 & Pokémon White 2: Super Music Collection |

| December 21, 2014 | Pokémon Omega Ruby & Pokémon Alpha Sapphire: Super Music Collection |

| April 27, 2016 | Pokémon Red and Green Super Music Collection |

| November 30, 2016 | Pokémon Sun & Pokémon Moon: Super Music Collection |

| December 23, 2017 | Pokémon Movie Music Collection2 |

^ The exact date of release is unknown.

^ Featuring music from Pokémon the Movie: Diancie and the Cocoon of Destruction, Pokémon the Movie: Hoopa and the Clash of Ages, Pokémon the Movie: Volcanion and the Mechanical Marvel, and Pokémon the Movie: I Choose You!

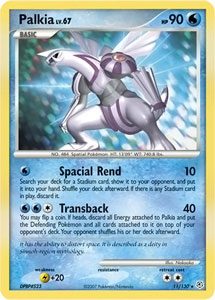

Pokémon Trading Card Game

The Pokémon Trading Card Game (TCG) is a collectible card game with a goal similar to a Pokémon battle in the video game series. Players use Pokémon cards, with individual strengths and weaknesses, in an attempt to defeat their opponent by "knocking out" their Pokémon cards.[41] The game was published in North America by Wizards of the Coast in 1999.[42] With the release of the Game Boy Advance video games Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire, The Pokémon Company took back the card game from Wizards of the Coast and started publishing the cards themselves.[42] The Expedition expansion introduced the Pokémon-e Trading Card Game, where the cards (for the most part) were compatible with the Nintendo e-Reader. Nintendo discontinued its production of e-Reader compatible cards with the release of FireRed and LeafGreen. In 1998, Nintendo released a Game Boy Color version of the trading card game in Japan; Pokémon Trading Card Game was subsequently released to the US and Europe in 2000. The game included digital versions cards from the original set of cards and the first two expansions (Jungle and Fossil), as well as several cards exclusive to the game. A sequel was released in Japan in 2001.[43]

Manga

There are various Pokémon manga series, four of which were released in English by Viz Media, and seven of them released in English by Chuang Yi. The manga series vary from game-based series to being based on the anime and the Trading Card Game. Original stories have also been published. As there are several series created by different authors, most Pokémon manga series differ greatly from each other and other media, such as the anime.[citation needed] Pokémon Pocket Monsters and Pokémon Adventures are the two manga in production since the first generation.

- Manga released in English

- The Electric Tale of Pikachu (Dengeki Pikachu), a shōnen manga created by Toshihiro Ono. It was divided into four tankōbon, each given a separate title in the North American and English Singapore versions: The Electric Tale of Pikachu, Pikachu Shocks Back, Electric Pikachu Boogaloo, and Surf's Up, Pikachu. The series is based loosely on the anime.

- Pokémon Adventures (Pocket Monsters SPECIAL in Japan) by Hidenori Kusaka (story), Mato (art formerly), and Satoshi Yamamoto (art currently), the most popular Pokémon manga based on the video games. The story series around the Pokémon Trainers who called "Pokédex holders".

- Magical Pokémon Journey (Pocket Monsters PiPiPi ★ Adventures), a shōjo manga

- Pikachu Meets the Press (newspaper style comics, not released by Chuang Yi)

- Ash & Pikachu (Satoshi to Pikachu)

- Pokémon Gold & Silver

- Pokémon Ruby-Sapphire and Pokémon Pocket Monsters

- Pokémon: Jirachi Wish Maker

- Pokémon: Destiny Deoxys

- Pokémon: Lucario and the Mystery of Mew (the third movie-to-comic adaptation)

- Pokémon Ranger and the Temple of the Sea[44] (the fourth movie-to-comic adaption)

- Pokémon Diamond and Pearl Adventure!

- Pokémon Adventures: Diamond and Pearl / Platinum[45]

- Pokémon: The Rise of Darkrai[46] (the fifth movie-to-comic adaption)

- Pokémon: Giratina and the Sky Warrior[47] (the sixth movie-to-comic adaption)

- Pokémon: Arceus and the Jewel of Life[48] (the seventh movie-to-comic adaption)

- Pokémon: Zoroark: Master of Illusions[49] (the eighth movie-to-comic adaption)

- Pokémon The Movie: White: Victini and Zekrom[50] (the ninth movie-to-comic adaption)

- Pokémon Black and White[51][52][53][54][55][56][57]

- Manga not released in English

- Pokémon Pocket Monsters by Kosaku Anakubo, the first Pokémon manga. Chiefly a gag manga, it stars a Pokémon Trainer named Red, his rude Clefairy, and Pikachu.

- Pokémon Card ni Natta Wake (How I Became a Pokémon Card) by Kagemaru Himeno, an artist for the Trading Card Game. There are six volumes and each includes a special promotional card. The stories tell the tales of the art behind some of Himeno's cards.

- Pokémon Get aa ze! by Miho Asada

- Pocket Monsters Chamo-Chamo ★ Pretty ♪ by Yumi Tsukirino, who also made Magical Pokémon Journey.

- Pokémon Card Master

- Pocket Monsters Emerald Chōsen!! Battle Frontier by Ihara Shigekatsu

- Pocket Monsters Zensho by Satomi Nakamura

Monopoly

A Pokémon-styled Monopoly board game was released in August 2014.[58]

Criticism and controversy

Morality and religious beliefs

Pokémon has been criticized by some fundamentalist Christians over perceived occult and violent themes and the concept of "Pokémon evolution", which they feel goes against the Biblical creation account in Genesis.[59] Sat2000, a satellite television station based in Vatican City, has countered that the Pokémon Trading Card Game and video games are "full of inventive imagination" and have no "harmful moral side effects".[60][61] In the United Kingdom, the "Christian Power Cards" game was introduced in 1999 by David Tate who stated, "Some people aren't happy with Pokémon and want an alternative, others just want Christian games." The game was similar to the Pokémon Trading Card Game but used Biblical figures.[62]

In 1999, Nintendo stopped manufacturing the Japanese version of the "Koga's Ninja Trick" trading card because it depicted a manji, a traditionally Buddhist symbol with no negative connotations. The Jewish civil rights group Anti-Defamation League complained because the symbol is the reverse of a swastika, a Nazi symbol. The cards were intended for sale in Japan only, but the popularity of Pokémon led to import into the United States with approval from Nintendo. The Anti-Defamation League understood that the issue symbol was not intended to offend and acknowledged the sensitivity that Nintendo showed by removing the product.[63]

In 1999, two nine-year-old boys from Merrick, New York sued Nintendo because they claimed the Pokémon Trading Card Game caused their problematic gambling.[64]

In 2001, Saudi Arabia banned Pokémon games and the trading cards, alleging that the franchise promoted Zionism by displaying the Star of David in the trading cards (a six-pointed star is featured in the card game) as well as other religious symbols such as crosses they associated with Christianity and triangles they associated with Freemasonry; the games also involved gambling, which is in violation of Muslim doctrine.[65][66]

Pokémon has also been accused of promoting materialism.[67]

Animal cruelty

In 2012, PETA criticized the concept of Pokémon as supporting cruelty to animals. PETA compared the game's concept, of capturing animals and forcing them to fight, to cockfights, dog fighting rings and circuses, events frequently criticized for cruelty to animals. PETA released a game spoofing Pokémon where the Pokémon battle their trainers to win their freedom.[68] PETA reaffirmed their objections in 2016 with the release of Pokémon Go, promoting the hashtag #GottaFreeThemAll.[69]

Health

On December 16, 1997, more than 635 Japanese children were admitted to hospitals with epileptic seizures.[70] It was determined the seizures were caused by watching an episode of Pokémon "Dennō Senshi Porygon", (most commonly translated "Electric Soldier Porygon", season 1, episode 38); as a result, this episode has not been aired since. In this particular episode, there were bright explosions with rapidly alternating blue and red color patterns.[71] It was determined in subsequent research that these strobing light effects cause some individuals to have epileptic seizures, even if the person had no previous history of epilepsy.[72] This incident is a common focus of Pokémon-related parodies in other media, and was lampooned by The Simpsons episode "Thirty Minutes over Tokyo"[73] and the South Park episode "Chinpokomon",[74] among others.

Monster in My Pocket

In March 2000, Morrison Entertainment Group, a toy developer based at Manhattan Beach, California, sued Nintendo over claims that Pokémon infringed on its own Monster in My Pocket characters. A judge ruled there was no infringement and Morrison appealed the ruling. On February 4, 2003, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed the decision by the District Court to dismiss the suit.[75]

Pokémon Go

Within its first two days of release, Pokémon Go raised safety concerns among players. Multiple people also suffered minor injuries from falling while playing the game due to being distracted.[76]

Multiple police departments in various countries have issued warnings, some tongue-in-cheek, regarding inattentive driving, trespassing, and being targeted by criminals due to being unaware of one's surroundings.[77][78] People have suffered various injuries from accidents related to the game,[79][80][81][82] and Bosnian players have been warned to stay out of minefields left over from the 1990s Bosnian War.[83] On July 20, 2016, it was reported that an 18-year-old boy in Chiquimula, Guatemala was shot and killed while playing the game in the late evening hours.[84] This was the first reported death in connection with the app. The boy's 17-year-old cousin, who was accompanying the victim, was shot in the foot. Police speculated that the shooters used the game's GPS capability to find the two.[85]

Cultural influence

Pokémon, being a globally popular franchise, has left a significant mark on today's popular culture. The Pokémon characters have become pop culture icons; examples include two different Pikachu balloons in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, Pokémon-themed airplanes operated by All Nippon Airways, merchandise items, and a traveling theme park that was in Nagoya, Japan in 2005 and in Taipei in 2006. Pokémon also appeared on the cover of the U.S. magazine Time in 1999.[86] The Comedy Central show Drawn Together has a character named Ling-Ling who is a parody of Pikachu.[87] Several other shows such as The Simpsons,[88] South Park[89] and Robot Chicken[90] have made references and spoofs of Pokémon, among other series. Pokémon was featured on VH1's I Love the '90s: Part Deux. A live action show based on the anime called Pokémon Live! toured the United States in late 2000.[91] Jim Butcher cites Pokémon as one of the inspirations for the Codex Alera series of novels.[92]

In November 2001, Nintendo opened a store called the Pokémon Center in New York, in Rockefeller Center,[93] modeled after the two other Pokémon Center stores in Tokyo and Osaka and named after a staple of the video game series. Pokémon Centers are fictional buildings where Trainers take their injured Pokémon to be healed after combat.[94] The store sold Pokémon merchandise on a total of two floors, with items ranging from collectible shirts to stuffed Pokémon plushies.[95] The store also featured a Pokémon Distributing Machine in which players would place their game to receive an egg of a Pokémon that was being given out at that time. The store also had tables that were open for players of the Pokémon Trading Card Game to duel each other or an employee. The store was closed and replaced by the Nintendo World Store on May 14, 2005.[96] Four Pokémon Center kiosks were put in malls in the Seattle area.[97] The Pokémon Center online store was relaunched on August 6, 2014.[98]

Professor of Education Joseph Tobin theorizes that the success of the franchise was due to the long list of names that could be learned by children and repeated in their peer groups. Its rich fictional universe provides opportunities for discussion and demonstration of knowledge in front of their peers. The names of the creatures were linked to its characteristics, which converged with the children's belief that names have symbolic power. Children can pick their favourite Pokémon and affirm their individuality while at the same time affirming their conformance to the values of the group, and they can distinguish themselves from others by asserting what they liked and what they did not like from every chapter. Pokémon gained popularity because it provides a sense of identity to a wide variety of children, and lost it quickly when many of those children found that the identity groups were too big and searched for identities that would distinguish them into smaller groups.[99]

Pokémon's history has been marked at times by rivalry with the Digimon media franchise that debuted at a similar time. Described as "the other 'mon'" by IGN's Juan Castro, Digimon has not enjoyed Pokémon's level of international popularity or success, but has maintained a dedicated fanbase.[100] IGN's Lucas M. Thomas stated that Pokémon is Digimon's "constant competition and comparison", attributing the former's relative success to the simplicity of its evolution mechanic as opposed to Digivolution.[101] The two have been noted for conceptual and stylistic similarities by sources such as GameZone.[102] A debate among fans exists over which of the two franchises came first.[103] In actuality, the first Pokémon media, Pokémon Red and Green, were released initially on February 27, 1996;[104] whereas the Digimon virtual pet was released on June 26, 1997.

Fan community

While Pokémon's target demographic is children, early purchasers of Pokémon Omega Ruby and Alpha Sapphire were in their 20s.[105] Many fans are adults who originally played the games as children had later returned to the series.[106]

Bulbapedia, a wiki-based encyclopedia[107] associated with longtime fan site Bulbagarden,[108][109] is the "Internet's most detailed Pokémon database project".[110] Bulbapedia received a mobile makeover with the release of BulbaGo, the app for Bulbapedia. The app's developer, Jonathan Zarra, also created the location based chat app GoChat for Pokémon Go.

A significant community around the Pokémon video games' metagame has existed for a long time, analyzing the best ways to use each Pokémon to their full potential in competitive battles. The most prolific competitive community is Smogon University, which has created a widely accepted tier-based battle system.[111] Smogon is affiliated with an online Pokémon game called Pokémon Showdown, in which players create a team and battle against other players around the world using the competitive tiers created by Smogon.[112]

In early 2014, an anonymous video streamer on Twitch launched Twitch Plays Pokémon, an experiment trying to crowdsource playing subsequent Pokémon games, starting with Pokémon Red.[113][114]

A challenge called the Nuzlocke Challenge was created in order for older players of the series to enjoy Pokémon again—but with a twist. The player is only allowed to capture the first Pokémon encountered in each area. If they do not succeed in capturing that Pokémon, there are no second chances. When a Pokémon faints, it is considered "dead" and must be released or stored in the PC permanently.[115] If the player faints, the game is considered over, and the player must restart.[116] The original idea consisted of 2 to 3 rules that the community has built upon. There are many fan made Pokémon games that contain a game mode similar to the Nuzlocke Challenge, such as Pokémon Uranium.[117]

See also

- List of Pokémon chapters

- List of Pokémon episodes

- List of Pokémon video games

- Pokémon episodes removed from rotation

References

- ^ "The ABC Book, A Pronunciation Guide". NLS Other Writings. NLS/BPH. January 7, 2013. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sora Ltd. (March 9, 2008). Super Smash Bros. Brawl (Wii). Nintendo.

(Announcer's dialog after the character Pokémon Trainer is selected (voice acted))

- ^ "Pokemon". Dictionary.com. IAC. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ "Company History". ポケットモンスターオフィシャルサイト. The Pokémon Company. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Legal Information". The Pokémon Company. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ "Pokémon". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. November 12, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Grubb, Jeff (September 16, 2013). "Nintendo releases 'Gotta Catch 'Em All' remix music video for Pokémon". VentureBeat. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Cannon, William (September 16, 2013). "'Pokemon X Y' News: Nintendo Brings Back 'Gotta Catch 'Em All' Catchphrase In New Remix Music Video; Watch Here [VIDEO]". Latin Times. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c "The 53 Most Anticipated Movies of 2019". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. June 29, 2018. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ Hutchins, Robert (June 26, 2018). "'Anime will only get stronger,' as Pokémon beats Marvel as highest grossing franchise". Licensing.biz. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ Burwick, Kevin (June 24, 2018). "Pokemon Rules Them All as Highest-Grossing Franchise Ever". MovieWeb. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ "6 Major Studio Blockbusters That Could Rule the Box Office This Year". The New York Observer. January 31, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ "VIDEO: A Pokemon Fan Theory Suggests Ash is Actually... in a Coma?". Comic Book Resources. January 26, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ Boyes, Emma (January 10, 2007). "UK paper names top game franchises". GameSpot. GameSpot UK. Archived from the original on January 12, 2007. Retrieved February 26, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Business Summary". The Pokémon Company. March 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Harris, Iain (May 30, 2018). "Pokemon Go captures 800 million downloads". Pocket Gamer. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Bailey, Kat (November 17, 2016). "Why the Pokemon Anime is the Most Successful Adaptation of a Videogame Ever". USgamer. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ "Hot Properties: Pokémon". Toy World Magazine: 68. January 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ "The Top 150 Global Licensors". License Global. April 1, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Carless, Simon (December 23, 2005). "Pokemon USA Moves Licensing In-House". Gamasutra. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (September 27, 2006). "Pokemon 10-Year Retrospective". IGN. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ^ Snyder, Benjamin (January 14, 2016). "Pokémon Announced a Super Bowl Ad to Celebrate its 20th Anniversary". Fortune. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ Makuch, Eddie (February 26, 2016). "Original Pokemon Virtual Console Re-Releases Support Pokemon Bank". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Jason (July 6, 2016). "Pokémon Go launches in US on iOS and Android". VentureBeat. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Williams, Caleb (October 13, 2017). "Live-Action 'Pokemon' Movie 'Detective Pikachu' Starts Filming This January in the UK". Omega Underground. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ Swider, Matt (March 22, 2007). "The Pokemon Series Pokedex". Gaming Target. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ John Kaufeld; Jeremy Smith (June 13, 2006). Trading Card Games For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-470-04407-0. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Ultimate Game Freak". Time. November 22, 1999. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ MacDonald, Mark; Brokaw, Brian; Arnold; J. Douglas; Elies, Mark (1999). Pokémon Trainer's Guide. Sandwich Islands Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 0-439-15404-9.

- ^ Loo, Egan (February 26, 2016). "Pokémon Sun & Moon Unveiled for 3DS in Holiday 2016". Anime News Network. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ Vincent, Brittany; Vincent, Brittany (February 27, 2019). "'Pokemon Sword and Shield' Announced For Nintendo Switch". Variety. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Farokhmanesh, Megan (May 29, 2018). "Another Pokémon game is still coming in 2019". The Verge. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ DeFreitas, Casey (May 29, 2018). "Core Pokemon RPG Coming to Nintendo Switch 2019". IGN. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pokemon Anime". Psypokes. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ "Pokemon Junior Chapter Book Series". WebData Technology Corporation. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Jr, Mike (November 30, 2016). "Rob Letterman To Direct Pokemon Film 'Detective Pikachu' For Legendary". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ McNary, Dave (July 25, 2018). "Ryan Reynolds' 'Detective Pikachu' Moves From Universal to Warner Bros". Variety. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ Hood, Cooper (August 24, 2018). "Detective Pikachu Movie Title & Logo Officially Revealed". Screen Rant. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ "Pokémon 2.B.A. Master Soundtrack CD Album". CD Universe. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- ^ "Pokémon: The First Movie Soundtrack CD Album". Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- ^ "Pokémon Trading Card Game [Strategy]". Archived from the original on May 22, 2007. Pokemon-tcg.com. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ a b Huebner, Chuck (March 12, 2003). "RE: Pokémon Ruby & Sapphire TCG Releases". Wizards.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Pokemon Card GB2 Release Information for Game Boy Color". GameFAQs. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Pokemon: Ranger and the Temple of the Sea. Viz Media. 2008. ISBN 1421522888.

- ^ Pokémon Adventures: Diamond and Pearl / Platinum, Vol. 2. Viz Media. 2011. ISBN 1421538172.

- ^ Pokémon: The Rise of Darkrai. Viz Media. 2008. ISBN 1421522896.

- ^ Pokemon: Giratina and the Sky Warrior!. Viz Media. 2009. ISBN 1421527014.

- ^ Pokémon: Arceus and the Jewel of Life. Viz Media. 2011. ISBN 1421538024.

- ^ Pokémon: Zoroark: Master of Illusions. Viz Media. 2011. ISBN 1421542218.

- ^ Pokémon the Movie: White: Victini and Zekrom. Viz Media. 2012. ISBN 1421549549.

- ^ Pokémon Black and White, Vol. 1 (9781421540900): Hidenori Kusaka, Satoshi Yamamoto. Viz Media. 2011. ISBN 1421540908.

- ^ Pokémon Black and White, Vol. 2 (9781421540917): Hidenori Kusaka, Satoshi Yamamoto. Viz Media. 2011. ISBN 1421540916.

- ^ Pokémon Black and White, Vol. 3 (9781421540924): Hidenori Kusaka, Satoshi Yamamoto. Viz Media. 2011. ISBN 1421540924.

- ^ Pokémon Black and White, Vol. 4 (9781421541143): Hidenori Kusaka, Satoshi Yamamoto. Viz Media. 2011. ISBN 1421541149.

- ^ Pokémon Black and White, Vol. 5 (9781421542805): Hidenori Kusaka, Satoshi Yamamoto. Viz Media. 2012. ISBN 1421542803.

- ^ Pokémon Black and White, Vol. 6 (9781421542812): Hidenori Kusaka, Satoshi Yamamoto. Viz Media. 2012. ISBN 1421542811.

- ^ Pokémon Black and White, Vol. 7 (9781421542829): Hidenori Kusaka, Satoshi Yamamoto. Viz Media. 2012. ISBN 142154282X.

- ^ USAopoly. "MONOPOLY®: Pokémon Kanto Edition™". USAopoly.

- ^ "Pokémon: The Movie (1999)". ChildCare Action Project. 1999. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (December 9, 1997). "Pokemon Gets Religion". People. Archived from the original on May 20, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Barrett, Devlin. "POKEMON EARNS PAPAL BLESSING". New York Post. Archived from the original on August 18, 2000. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Pokémon trumped by pocket saints". BBC. June 27, 2000. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Jim (December 3, 1999). "'Swastika' Pokemon card dropped". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011 – via HighBeam.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Crowley, Kieran (October 1999). "Lawsuit Slams Pokemon As Bad Bet for Addicted Kids". New York Post. Archived from the original on October 22, 2000.

- ^ "Saudi bans Pokemon". CNN. March 26, 2001. Archived from the original on January 18, 2008.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia bans Pokemon". BBC News. March 26, 2001. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ Ramlow, Todd R. (2000). "Pokemon, or rather, Pocket Money". Popmatters.

- ^ "PETA wages war on Pokemon for virtual animal cruelty". CNET. October 8, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "#GottaFreeEmAll: Pokémon Go criticised by PETA for 'animal cruelty' parallels". Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ Ferlazzo, Edoardo; Zifkin, Benjamin G.; Andermann, Eva; Andermann, Frederick (2005). "REVIEW ARTICLE: Cortical triggers in generalized reflex seizures and epilepsies" (PDF). Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Pokemon on the Brain". University of Washington. March 11, 2000. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Color Changes in TV Cartoons Cause Seizures". ScienceDaily. June 1, 1999. Archived from the original on November 8, 2004.

- ^ "Thirty Minutes Over Tokyo". The Simpsons Archive. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "South Park Goes Global: Reading Japan in Pokemon". University of Auckland. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "4Licensing Corporation Legal Proceedings". EDGAR Online. March 31, 2003. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Nakashinma, Ryan (July 8, 2016). "Players in hunt for Pokemon Go monsters feel real-world pain". Miami Herald. Los Angeles. Associated Press. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ Irby, Kate (July 11, 2016). "Police: Pokemon Go leading to increase in local crime". The Idaho Statesman. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Mehta, Diana; Cameron, Peter (July 14, 2016). "OPP warn Pokémon Go players of 'potential risk and harm' while searching for monsters". CBC.ca. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ "Mom says teenage daughter hit by car in Tarentum after playing 'Pokemon Go'". WPXI. July 13, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Mason, Greg (July 14, 2016). "Auburn police: Driver crashes into tree while playing 'Pokemon Go'". Auburnpub.com. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Hernandez, David (July 13, 2016). "'Pokemon Go' players fall off 90-foot ocean bluff". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Stortstrom, Mary (July 14, 2016). "Police: Don't fall 'catching them all'". The Journal. Martinsburg, West Virginia. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

A 12-year-old Jefferson County boy suffered a broken femur bone Tuesday night while playing the Pokemon game just off Shipley School Road. A Harpers Ferry first-responder said Wednesday morning the boy was running in the dark and fell off a five-foot-high storm sewer and suffered the leg injury.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pokemon Go: Bosnia players warned of minefields". BBC. July 19, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ Moore, Charlie; Couzens, Gerard (July 21, 2016). "Pokemon Go sees its first death: Teenager, 18, is killed and his cousin injured while playing game in Guatemal". Daily Mail. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (July 20, 2016). "Teenager shot and killed while searching for creatures in Pokemon Go". The Independent. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ "TIME Magazine Cover: Pokeman - Nov. 22, 1999". TIME.com. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ "Pokemon Sightings and Rip-offs". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ Jennifer Sherman (May 3, 2017). "Lisa, Homer Catch 'Peekemon' in The Simpsons' Pokémon Go Parody". Anime News Network. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Andy Patrizio (December 17, 2003). "South Park: The Complete Third Season". IGN. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Steve Greene (July 21, 2017). "'Robot Chicken' Trailer: Season 9 is Here to Make Fun of Everything That Comic-Con Loves". IndieWire. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ "Pokémon Live!". Pokémon World. Nintendo. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Butcher, Jim (April 6, 2010). "Jim Butcher chats about Pokemon, responsibility, and Changes". fantasyliterature.com. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Steiner, Ina (November 18, 2001). "Pokemon Center Opens in NYC". EcommerceBytes.com. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Raichu 526. "PokeZam.com – Pokemon Center NY – PokeZam". PokeZam. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fun for Kids". Big Apple Visitors Center. 2010. Archived from the original on January 2, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Pokemon Center NY". ManhattanLivingMag.com. 2009. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Pokémon Center vending machine locations in Seattle". Pokémon Center Support. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Sarkar, Samit (July 2, 2014). "Pokémon Center online store opening Aug. 6 in US, soft launch today". Polygon. Vox Media.

- ^ Joseph Jay Tobin (2004). Pikachu's global adventure: the rise and fall of Pokémon. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3287-6.

- ^ Castro, Juan (May 20, 2005). "E3 2005: Digimon World 4". IGN. Archived from the original on May 20, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (August 21, 2009). "Cheers & Tears: DS Fighting Games". IGN. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ Bedigian, Louis (July 12, 2002). "Digimon World 3 Review". GameZone. Archived from the original on January 27, 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ DeVries, Jack (November 22, 2006). "Digimon World DS Review". IGN. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Related Games". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Pokémon's Audience Is Growing Older". Siliconera. December 1, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ^ "Pokémon's Audience Is Growing Older". Siliconera. December 1, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Neiburger, Eli (July 1, 2007). "Games... in the Library?". School Library Journal. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

Players can refer (or contribute) to Bulbapedia, a wiki-style encyclopedia of the Pokémon universe, to learn about the attributes, strengths, and weaknesses of over 500 different characters; the literacy required for success extends beyond the game itself.

- ^ O'Neil, Mathieu (2009). Cyberchiefs: autonomy and authority in online tribes (1. publ. ed.). London: Pluto Press. p. 148. ISBN 0745327974.

Bulbapedia is a MediaWiki installation run by Pokémon fansite Bulbagarden.net for the purpose of creating a Pokémon-focused encyclopedia. This project is overseen by the Bulbapedia editorial board, and Bulbagarden's executive staff. Bulbapedia also incorporates the Bulbanews wiki, a news organization run by Bulbagarden as a means of publishing Pokémon news quickly and effectively. Bulbapedia is a founding member of Encyclopaediae Pokémonis, a multilingual, open-content Pokémon encyclopedia project.

- ^ Khaw, Cassandra (October 19, 2013). "More Starter Pokemon, Less Starting Pokemon: We Can Make Pokémon X & Y's Wonder Trade Better!". USgamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McKinley Noble. "Major Pokemon game to be announced May 10". GamePro. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011.

According to Pokemon Japan and Bulbapedia, the Internet's most detailed Pokemon database project...

- ^ Magdaleno, Alex (February 20, 2014). "Inside the Secret World of Competitive Pokémon". Mashable.

- ^ Hernandez, Patricia (May 2, 2015). "The Most Popular Pokémon Used By Top Players, In One Image". Kotaku. Univision Communications. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Cunningham, Andrew (February 18, 2014). "The bizarre, mind-numbing, mesmerizing beauty of "Twitch Plays Pokémon"". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Farokhmanesh, Megan (March 25, 2014). "Twitch Plays Pokemon will continue as long as it has an active following". Polygon. Vox Media, Inc. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ "What is the Nuzlocke Challenge?". Nuzlocke.com. 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ Martinez, Phillip (May 14, 2015). "Pokémon Nuzlocke Challenge: 20 Years Of Playing Pokémon And This Is The Most Stressful Experience Ever". iDigitalTimes. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Buzzi, Matthew (December 26, 2014). "Check Out Pokemon Uranium, A Downloadable Fan Project About Angry Nuclear-Type Pokemon in an Original World". Gamenguide. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- Tobin, Joseph, ed. (February 2004). Pikachu's Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3287-6.