Alternative cancer treatments: Difference between revisions

Bon courage (talk | contribs) |

→Terminology: The difference between complementary and alternative therapies |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

'''Alternative cancer treatments''' are [[Alternative medicine|alternative or complementary treatments]] for cancer that have not been approved by the government agencies responsible for the [[regulation of therapeutic goods]]. They include diet and exercise, chemicals, herbs, devices, and manual procedures. The treatments are not supported by [[evidence-based medicine|evidence]], either because no proper testing has been conducted, or because testing did not demonstrate [[statistically significant]] efficacy. Concerns have been raised about the safety of some of them. Some treatments that have been proposed in the past have been found in clinical trials to be useless or unsafe. Some of these obsolete or disproven treatments continue to be promoted, sold, and used. |

'''Alternative cancer treatments''' are [[Alternative medicine|alternative or complementary treatments]] for cancer that have not been approved by the government agencies responsible for the [[regulation of therapeutic goods]]. They include diet and exercise, chemicals, herbs, devices, and manual procedures. The treatments are not supported by [[evidence-based medicine|evidence]], either because no proper testing has been conducted, or because testing did not demonstrate [[statistically significant]] efficacy. Concerns have been raised about the safety of some of them. Some treatments that have been proposed in the past have been found in clinical trials to be useless or unsafe. Some of these obsolete or disproven treatments continue to be promoted, sold, and used. |

||

A distinction is typically made between complementary treatments which do not disrupt conventional medical treatment, and alternative treatments which may replace conventional treatment. |

|||

Alternative cancer treatments are typically contrasted with [[experimental cancer treatment]]s – which are treatments for which experimental testing is underway – and with complementary treatments, which are non-invasive practices used alongside other treatment. All approved [[chemotherapeutic]] cancer treatments were considered experimental cancer treatments before their safety and efficacy testing was completed. |

Alternative cancer treatments are typically contrasted with [[experimental cancer treatment]]s – which are treatments for which experimental testing is underway – and with complementary treatments, which are non-invasive practices used alongside other treatment. All approved [[chemotherapeutic]] cancer treatments were considered experimental cancer treatments before their safety and efficacy testing was completed. |

||

| Line 19: | Line 20: | ||

Complementary treatments are used in conjunction with proven mainstream treatments. They tend to be pleasant for the patient, not involve substances with any pharmacological effects, inexpensive, and intended to treat side effects rather than to kill cancer cells.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wesa KM, Cassileth BR |title=Is there a role for complementary therapy in the management of leukemia? |journal=Expert Rev Anticancer Ther |volume=9 |issue=9 |pages=1241–9 |date=September 2009 |pmid=19761428 |pmc=2792198 |doi=10.1586/era.09.100 }}</ref> [[Medical massage]] and [[self-hypnosis]] to treat pain are examples of complementary treatments. |

Complementary treatments are used in conjunction with proven mainstream treatments. They tend to be pleasant for the patient, not involve substances with any pharmacological effects, inexpensive, and intended to treat side effects rather than to kill cancer cells.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wesa KM, Cassileth BR |title=Is there a role for complementary therapy in the management of leukemia? |journal=Expert Rev Anticancer Ther |volume=9 |issue=9 |pages=1241–9 |date=September 2009 |pmid=19761428 |pmc=2792198 |doi=10.1586/era.09.100 }}</ref> [[Medical massage]] and [[self-hypnosis]] to treat pain are examples of complementary treatments. |

||

Alternative treatments, by contrast, are used in place of mainstream treatments. The most popular alternative cancer therapies include restrictive [[diets]], [[mind-body intervention]]s, [[bioelectromagnetic]]s, [[nutritional supplement]]s, and [[herbology|herbs]].<ref name=Cassileth1996/> The popularity and prevalence of different treatments varies widely by region.<ref name=Cassileth2001>{{cite journal |author=Cassileth BR, Schraub S, Robinson E, Vickers A |title=Alternative medicine use worldwide: the International Union Against Cancer survey |journal=Cancer |volume=91 |issue=7 |pages=1390–3 |date=April 2001 |pmid=11283941 |doi=10.1002/1097-0142(20010401)91:7<1390::AID-CNCR1143>3.0.CO;2-C}}</ref> |

Alternative treatments, by contrast, are used in place of mainstream treatments. The most popular alternative cancer therapies include restrictive [[diets]], [[mind-body intervention]]s, [[bioelectromagnetic]]s, [[nutritional supplement]]s, and [[herbology|herbs]].<ref name=Cassileth1996/> The popularity and prevalence of different treatments varies widely by region.<ref name=Cassileth2001>{{cite journal |author=Cassileth BR, Schraub S, Robinson E, Vickers A |title=Alternative medicine use worldwide: the International Union Against Cancer survey |journal=Cancer |volume=91 |issue=7 |pages=1390–3 |date=April 2001 |pmid=11283941 |doi=10.1002/1097-0142(20010401)91:7<1390::AID-CNCR1143>3.0.CO;2-C}}</ref> Although the conventional physicians should always be kept aware of any complementary treatments used, many are supportive or at least tolerant of their use, and may actually recommend them.<ref>[http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancers-in-general/treatment/complementary-alternative/about/the-difference-between-complementary-and-alternative-therapies "The difference between complementary and alternative therapies"], [[Cancer Research UK]], accessed 20 November, 2014</ref> |

||

== Extent of their usage == |

== Extent of their usage == |

||

Revision as of 16:03, 20 November 2014

Alternative cancer treatments are alternative or complementary treatments for cancer that have not been approved by the government agencies responsible for the regulation of therapeutic goods. They include diet and exercise, chemicals, herbs, devices, and manual procedures. The treatments are not supported by evidence, either because no proper testing has been conducted, or because testing did not demonstrate statistically significant efficacy. Concerns have been raised about the safety of some of them. Some treatments that have been proposed in the past have been found in clinical trials to be useless or unsafe. Some of these obsolete or disproven treatments continue to be promoted, sold, and used.

A distinction is typically made between complementary treatments which do not disrupt conventional medical treatment, and alternative treatments which may replace conventional treatment. Alternative cancer treatments are typically contrasted with experimental cancer treatments – which are treatments for which experimental testing is underway – and with complementary treatments, which are non-invasive practices used alongside other treatment. All approved chemotherapeutic cancer treatments were considered experimental cancer treatments before their safety and efficacy testing was completed.

Since the 1940s, medical science has developed chemotherapy, radiation therapy, adjuvant therapy and the newer targeted therapies, as well as refined surgical techniques for removing cancer. Before the development of these modern, evidence-based treatments, 90% of cancer patients died within five years.[2] With modern mainstream treatments, only 34% of cancer patients die within five years.[3] However, while mainstream forms of cancer treatment generally prolong life or permanently cure cancer, most treatments also have side effects ranging from unpleasant to fatal, such as pain, blood clots, fatigue, and infection.[4] These side effects and the lack of a guarantee that treatment will be successful create appeal for alternative treatments for cancer, which purport to cause fewer side effects or to increase survival rates.

Alternative cancer treatments have typically not undergone properly conducted, well-designed clinical trials, or the results have not been published due to publication bias (a refusal to publish results of a treatment outside that journal's focus area, guidelines or approach). Among those that have been published, the methodology is often poor. A 2006 systematic review of 214 articles covering 198 clinical trials of alternative cancer treatments concluded that almost none conducted dose-ranging studies, which are necessary to ensure that the patients are being given a useful amount of the treatment.[5] These kinds of treatments appear and vanish frequently, and have throughout history.[6]

Terminology

Complementary and alternative cancer treatments are often grouped together, in part because of the adoption of the phrase "complementary and alternative medicine" by the United States Congress.[7] However, according to Barrie R. Cassileth, in cancer treatment the distinction between complementary and alternative therapies is "crucial".[6]

Complementary treatments are used in conjunction with proven mainstream treatments. They tend to be pleasant for the patient, not involve substances with any pharmacological effects, inexpensive, and intended to treat side effects rather than to kill cancer cells.[8] Medical massage and self-hypnosis to treat pain are examples of complementary treatments.

Alternative treatments, by contrast, are used in place of mainstream treatments. The most popular alternative cancer therapies include restrictive diets, mind-body interventions, bioelectromagnetics, nutritional supplements, and herbs.[6] The popularity and prevalence of different treatments varies widely by region.[9] Although the conventional physicians should always be kept aware of any complementary treatments used, many are supportive or at least tolerant of their use, and may actually recommend them.[10]

Extent of their usage

Survey data about how many cancer patients use alternative or complimentary therapies vary from nation to nation as well from region to region. A 2000 study published by the European Journal of Cancer evaluated a sample of 1023 women from a British cancer registry suffering from breast cancer and found that 22.4% had consulted with a practitioner of complementary therapies in the previous twelve months. The study concluded that the patients had spent many thousands of pounds on such measures and that use "of practitioners of complementary therapies following diagnosis is a significant and possibly growing phenomenon".[11]

In terms of Australia, one study reported that 46% of children suffering from cancer have utilized at least one non-traditional therapy. As well, 40% of those of any age receiving palliative care had tried at least one such therapy. Some of the most popular alternative cancer treatments were found to be dietary therapies, antioxidants, high dose vitamins, and herbal therapies.[12]

Usage of unconventional cancer treatments in the United States have been influenced by the U.S. federal government's National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), initially known as the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM), which was established in 1992 as a National Institutes of Health (NIH) adjunct by the U.S. Congress. Over thirty American medical schools have offered general courses on alternative medicine. That includes the Georgetown, Columbia, and Harvard university systems among others.[6]

People who choose alternative treatments

People who choose alternative treatments tend to believe that evidence-based medicine is extremely invasive or ineffective, while still believing that their own health could be improved.[13] They are loyal to their alternative healthcare providers and believe that "treatment should concentrate on the whole person".[13]

Cancer patients who choose complementary or alternative treatments in addition to conventional treatments believe themselves less likely to die than patients who choose only conventional treatments.[14] They feel a greater sense of control over their destinies, and report less anxiety and depression.[14] They are more likely to engage in benefit finding, which is the psychological process of adapting to a traumatic situation and deciding that the trauma was valuable, usually because of perceived personal and spiritual growth during the crisis.[15]

However, patients who use alternative treatments have a poorer survival time, even after controlling for type and stage of disease.[16] The reason that patients using alternative treatments die sooner may be because patients who accurately perceive that they are likely to survive do not attempt unproven remedies, and patients who accurately perceive that they are unlikely to survive are attracted to unproven remedies.[16] Among patients who believe their condition to be untreatable by evidence-based medicine, "desperation drives them into the hands of anyone with a promise and a smile."[17] Con artists have long exploited fear, ignorance, and desperation to strip dying people of their money, comfort, and dignity.

About half the practitioners who dispense complementary or alternative treatments are physicians, although they tend to be generalists rather than oncologists. As many as 60% of American physicians have referred their patients to a complementary or alternative practitioner for some purpose.[6]

Ineffective treatments

This section contains a list of therapies that have been recommended to treat or prevent cancer in humans but which lack good scientific and medical evidence of effectiveness. In many cases, there is good scientific evidence that the alleged treatments do not work. Unlike accepted cancer treatments, unproven and disproven treatments are generally ignored or avoided by the medical community, and are often pseudoscientific.[18]

Edzard Ernst has stated:

- "... any alternative cancer cure is bogus by definition. There will never be an alternative cancer cure. Why? Because if something looked halfway promising, then mainstream oncology would scrutinize it, and if there is anything to it, it would become mainstream almost automatically and very quickly. All curative "alternative cancer cures" are based on false claims, are bogus, and, I would say, even criminal."[19]

Despite this, many of these therapies have continued to be promoted as effective, particularly by practitioners of alternative medicine. Scientists consider this practice quackery,[20][21] and some of those engaged in it have been investigated and prosecuted by public health regulators such as the US Federal Trade Commission,[22] the Mexican Secretariat of Health[23] and the Canadian Competition Bureau.[24] In the United Kingdom, the Cancer Act makes the unauthorised advertising of cancer treatments a criminal offense.[25][26]

Alternative health systems

- Aromatherapy – the use of fragrant substances, such as essential oils, in the belief that smelling them will positively affect health. There is some evidence that aromatherapy improves general well-being, however it has also been promoted for its ability to fight diseases, including cancer. The American Cancer Society state, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that aromatherapy is effective in preventing or treating cancer".[27]

- Ayurvedic medicine – a 5,000 year-old system of traditional medicine which originated on the Indian subcontinent. According to Cancer Research UK, "there is no scientific evidence to prove that Ayurvedic medicine can treat or cure cancer or any other disease".[28]

- German New Medicine – a popular medical system devised by Ryke Geerd Hamer (1935 – ), in which all disease is seen as deriving from emotional shock, and mainstream medicine is regarded as a conspiracy promulgated by Jews. There is no evidence to support its claims, and no biological reason why it should work.[29]

- Herbalism – a whole-body approach to promoting health, in which substances are derived from entire plants so as not to disturb what herbalists believe is the delicate chemistry of the plant as a whole.[30] According to Cancer Research UK, "there is currently no strong evidence from studies in people that herbal remedies can treat, prevent or cure cancer".[30]

- Holistic medicine – a general term for an approach to medicine which encompasses mental and spiritual aspects, and which is manifested in sundry complementary and alternative methods. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that these complementary and alternative methods, when used without mainstream or conventional medicine, are effective in treating cancer or any other disease".[31]

- Homeopathy – a pseudoscientific system of medicine based on ultra-diluted substances. Some proponents promote homeopathy as a cancer cure; however, according to the American Cancer Society, "there is no reliable evidence showing that homeopathic remedies can treat cancer in humans".[32]

- Native American healing – shamanistic forms of medicine traditionally practiced by some indigenous American peoples and which have been claimed as being capable of curing human diseases, including cancer.[33] The American Cancer Society say that while its supportive, community aspects might improve general well-being, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that Native American healing can cure cancer or any other disease".[33]

- Naturopathy – a system of alternative medicine based on a belief in energy forces in the body, and an avoidance of conventional medicine; it is promoted as a treatment for cancer and other ailments. According to the American Cancer Society, "scientific evidence does not support claims that naturopathic medicine can cure cancer or any other disease".[34]

Diet-based

- Alkaline diet – a restrictive diet of non-acid foods, based on the claim this will affect the pH of the body generally, so reducing the risk of heart disease and cancer. According to the Canadian Cancer Society, "there is no evidence to support any of these claims."[35]

- Breuss diet – a diet based on vegetable juice and tea devised by Rudolf Breuss (1899–1990), who claimed it could cure cancer. Physicians have said that, in common with other "cancer diets", there is no evidence of effectiveness and some risk of harm.[36]

- Budwig protocol (or Budwig diet) – an anti-cancer diet developed in the 1950s by Johanna Budwig (1908–2003). The diet is rich in flaxseed oil mixed with cottage cheese, and emphasizes meals high in fruits, vegetables, and fiber; it avoids sugar, animal fats, salad oil, meats, butter, and especially margarine. Cancer Research UK say, "there is no reliable evidence to show that the Budwig diet [...] helps people with cancer".[37]

- Fasting – not eating or drinking for a period – a practice which has been claimed by some alternative medicine practitioners to help fight cancer, perhaps by "starving" tumors. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that fasting is effective for preventing or treating cancer in humans".[38]

- Hallelujah diet – a restrictive "biblical" diet based on raw food, claimed by its inventor to have cured his cancer. Stephen Barrett has written on Quackwatch: "Although low-fat, high-fiber diets can be healthful, the Hallelujah Diet is unbalanced and can lead to serious deficiencies."[39]

- Kousmine diet – a restrictive diet devised by Catherine Kousmine (1904–1992) which emphasized fruit, vegetables, grains, pulses and the use of vitamin supplements. There is no evidence that the diet is an effective cancer treatment.[40]

- Macrobiotic diet – a restrictive diet based around grains and unrefined foods, and promoted by some as a preventative and cure for cancer.[41] Cancer Research UK states "we don't support the use of macrobiotic diets for people with cancer".[42]

- Moerman Therapy – a highly restrictive diet devised by Cornelis Moerman (1893–1988). Its effectiveness is supported by anecdote only – there is no evidence of its worth as a cancer treatment.[43]

- Superfood – a marketing term applied to certain foods with supposed health-giving properties. Cancer Research UK note that superfoods are often promoted as having an ability to prevent or cure diseases, including cancer; they caution, "you shouldn't rely on so-called 'superfoods' to reduce the risk of cancer. They cannot substitute for a generally healthy and balanced diet".[44]

Electromagnetic and energy-based

- Bioresonance therapy – diagnosis and therapy delivered by attaching an electrical device to the patient, on the basis that cancer cells emit certain electromagnetic oscillations. The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center says that such claims are not supported by any evidence and note that the US Food and Drug Administration has prosecuted many sellers of such devices.[45]

- Electrohomeopathy (or Mattei cancer cure) – a treatment devised by Count Cesare Mattei (1809–1896), who proposed that different "colors" of electricity could be used to treat cancer. Popular in the late nineteenth century, electrohomeopathy has been described as "utter idiocy".[46]

- Electro Physiological Feedback Xrroid – an electronic device promoted as being capable of diagnosing and treating cancer and a host of other ailments. However, according to Quackwatch: "The Quantum Xrroid device is claimed to balance 'bio-energetic' forces that the scientific community does not recognize as real. It mainly reflects skin resistance (how easily low-voltage electric currents from the device pass through the skin), which is not related to the body's health."[47]

- Light therapy – the use of light to treat medical conditions. According to the American Cancer Society, alternative approaches – such as chromotherapy or the use of light boxes – have not been shown to be effective for cancer treatment.[48]

- Magnetic therapy – the practice of placing magnets on and around the body in order to treat illness. Although this has been promoted as a treatment for cancer and other diseases, the American Cancer Society say, "available scientific evidence does not support these claims".[49]

- Orgone – a type of life force proposed to exist by William Reich (1897–1957) which he claimed could be harnessed to cure diseases, including cancer, perhaps by sitting inside an "orgone accumulator" – a cupboard-like box with metal and organic linings. Quackwatch comments that scientists investigating Reich's ideas have been "unable to find the slightest evidence in Reich's data or elsewhere that such a thing as orgone exists".[50]

- Polarity therapy – a type of energy medicine based on the idea that the positive or negative charge of a person's electromagnetic field affects their health. Although it is promoted as effective for curing a number of human ailments, including cancer, the American Cancer Society says "available scientific evidence does not support claims that polarity therapy is effective in treating cancer or any other disease".[51]

- Rife Frequency Generator – an electronic device purported to cure cancer by transmitting radio waves. Cancer Research UK state, "there is no evidence to show that the Rife machine does what its supporters say it does".[52]

- Therapeutic Touch (or TT) – contrary to its name, a technique that does not usually involve touching; rather, a practitioner holds their hands close to a patient to affect the "energy" in their body. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support any claims that TT can cure cancer or other diseases".[53]

- Zoetron therapy – therapy based around a large electromagnetic device that emitted a weak field which, it was claimed, could kill cancer cells. Patients were charged US$15,000 up-front for treatment in Mexican clinics. In 2005 criminal charges were brought against the owners of the company making the device for their claims of its worth.[24] Quackwatch says: "there is no scientific evidence or reason to believe that exposure to weak magnetic fields will kill any cells".[23]

Hybrid

- Clark's "Cure for All Cancers" – an alternative medicine regime promoted by Hulda Regehr Clark (1928–2009), who (before her death from cancer) claimed it could cure all human diseases, including all cancers. The regime was based on the belief that disease was caused by "parasites", and included herbal remedies, chelation therapy, and the use of electronic devices. Quackwatch describes her notions as "absurd".[54]

- Contreras therapy – treatment offered at the Oasis of Hope Hospital in Tijuana, Mexico which includes a number of ineffective treatments including the use of amgydalin and metabolic therapy. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center lists "Contreras Therapy" alongside others which "show no evidence of efficacy".[55]

- Gerson therapy – a predominantly diet regime, generally based on: limiting salt, protein and other foods; ingesting large quantities of fruits and vegetables through juicing; augmenting the intake of potassium and iodine; and the use of coffee enemas. According to Cancer Research UK, "available scientific evidence does not support any claims that Gerson therapy can treat cancer [...] Gerson therapy can be very harmful to your health."[56]

- Gonzales protocol – a treatment regime devised by Nicholas Gonzalez based on Gerson therapy. According to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the treatment is a type of metabolic therapy that shows "no evidence of efficacy".[57]

- Hoxsey therapy – a treatment consisting of a caustic herbal paste for external cancers or a herbal mixture for "internal" cancers, combined with laxatives, douches, vitamin supplements and dietary changes. A review by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center found no evidence that the Hoxsey Therapy was effective as a treatment for cancer.[58]

- Issels treatment – a regime recommended to be used alongside conventional treatment. It requires removal of metal fillings from the patient's mouth, and adherence to a restrictive diet. Cancer Research UK state: "There is no scientific or medical evidence to back up the claims made by the Issels website".[59]

- Kelley treatment – a treatment regime devised by William Donald Kelley (1925–2005) based on Gerson therapy, with additional features including prayer and osteopathic manipulation. Famously, Steve McQueen used it for three months before his death. According to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Kelley treatment is a type of metabolic therapy that shows "no evidence of efficacy".[57]

- Live blood analysis – in alternative medicine, the practice of examining blood samples under a high-powered microscope, claiming this can detect and predict cancer and other illnesses, so leading to a prescription of dietary supplements that are supposed to function as treatment. The practice has been dismissed as quackery by the medical profession.[60]

- Livingston-Wheeler Therapy – a therapeutic regime that included a restricted diet, various drugs, therapy and the use of enemas. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that Livingston-Wheeler therapy was effective in treating cancer or any other disease".[61]

- Lorraine Day's 10-step program – a regime devised by Lorraine Day based on a restrictive diet and behavioral changes, such as giving up work and ceasing to watch television. Stephen Barrett wrote on Quackwatch, "In my opinion, her advice is untrustworthy and is particularly dangerous to people with cancer".[62]

- Metabolic therapies – an umbrella term for diet- and enema-based "detoxification" regimes, such as the Gerson therapy, promoted to cure cancer and other disease. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center states: "Retrospective reviews of the Gerson, Kelley, and Contreras therapies show no evidence of efficacy."[57]

Plant- and fungus-based

- Actaea racemosa (or black cohosh) – a flowering plant from which dietary supplements are made that are promoted for their health-giving properties. According to Cancer Research UK, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that black cohosh is effective in treating or preventing cancer".[63]

- Aloe – a genus of flowering succulent plants native to Africa. According to Cancer Research UK, a potentially deadly product called T-UP is made of concentrated aloe, and promoted as a cancer cure. They say "there is currently no evidence that aloe products can help to prevent or treat cancer in humans".[64]

- Amygdalin (sometimes going by the trade name Laetrile) – a glycoside, has been promoted as a cancer cure. However, it has been found to be ineffective and toxic; its promotion has been described as "the slickest, most sophisticated, and certainly the most remunerative cancer quack promotion in medical history."[65]

- Andrographis paniculata – a herb used in Ayurvedic medicine, and promoted as a dietary supplement for cancer prevention and cure. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center has stated that there is no evidence that it helps prevent or cure cancer.[66]

- Aveloz (also called firestick plant, pencil tree or Euphorbia tirucalli) – a succulent shrub native to parts of Africa and South America. Its sap is promoted as a cancer treatment, however, according to the American Cancer Society, studies suggest that "aveloz sap may actually suppress the immune system, promote tumor growth, and lead to the development of certain types of cancer".[67]

- Bach flower remedies – preparations devised by Edward Bach (1886–1936) in which tiny amounts of plant material are diluted in a mixture of water and brandy. According to Cancer Research UK, flower remedies are sometimes promoted as being capable of boosting the immune system, but "there is no scientific evidence to prove that flower remedies can control, cure or prevent any type of disease, including cancer".[68]

- Cannabis – used as a recreational and medicinal drug. Chemicals derived from cannabis have been extensively studied for potential anti-cancer effect and while there has been much laboratory work, claims that cannabis can "cure" cancer are – according to Cancer Research UK – "highly misleading".[69] The US National Cancer Institute has concluded, "At this time, there is not enough evidence to recommend that patients inhale or ingest Cannabis as a treatment for cancer-related symptoms or side effects of cancer therapy."[70]

- Cansema (also called black salve) – a type of paste or poultice often promoted as a cancer cure, especially for skin cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, there is no evidence that these are effective in treating cancer, and they can be harmful, causing burns and disfigurement.[71]

- Capsicum – the name given to a group of plants in the nightshade family, well known for producing hot chilli peppers such as the cayenne pepper and the jalapeño. A number of capsicum-based products, including teas and capsules, are promoted for their health benefits, including as a claimed cancer treatment. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific research does not support claims for the effectiveness of capsicum or whole pepper supplements in preventing or curing cancer at this time".[72]

- Carctol – a herbal dietary supplement made from ayurvedic herbs. It has been aggressively marketed in the United Kingdom as a cancer treatment, but there is no evidence of its effectiveness.[73]

- Cassava – a woody shrub native to South America, the root of which is a carbohydrate-rich foodstuff. Cassava root has been promoted as treatment for cancer. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "there is no convincing scientific evidence that cassava or tapioca is effective in preventing or treating cancer".[74]

- Castor oil – an oil made from the seeds of the castor oil plant. The claim has been made that applying it to the skin can help cure cancer. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that castor oil on the skin cures cancer or any other disease."[75]

- Chaparral (or Larrea tridentata) – a plant used to make a herbal remedy which is sold as cancer treatment. Cancer Research UK state that: "We don't recommend that you take chaparral to treat or prevent any type of cancer."[76]

- Chlorella – a type of algae promoted for its health-giving properties, including a claimed ability to treat cancer. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific studies do not support its effectiveness for preventing or treating cancer or any other disease in humans".[77]

- Echinacea – a group of herbaceous flowering plants in the daisy family, marketed as a herbal supplement that can help combat cancer. According to Cancer Research UK, "there is no scientific evidence to show that echinacea can help treat, prevent or cure cancer in any way."[78]

- Ellagic acid – a natural phenol found in some foods, especially berries, and which has been marketed as having the ability to prevent and treat a number of human maladies, including cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, such claims are not proven.[79]

- Essiac – a blended herbal tea devised in the early 20th century and promoted as a cancer cure. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration include Essiac in a list of "Fake Cancer 'Cures' Consumers Should Avoid".[80]

- Ginger – a root of plants of the Zingiber family, and a popular spice in many types of cuisine. Ginger has been promoted as a cancer treatment for its supposed ability to halt tumor growth; however, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support this".[81]

- Ginseng – a species of perennial plant, the root of which is promoted for its therapeutic value, including a claimed ability to help fight cancer. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that ginseng is effective in preventing or treating cancer in humans".[82]

- Glyconutrients – are types of sugar extracted from plants; they are mostly marketed in a product with the brand name "Ambrotose" by Mannatech, Inc. According to the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center these products have been "promoted aggressively to cancer patients" on the basis they can help cellular health and boost the immune system, but that "strong scientific evidence to support these claims is lacking".[83]

- Goldenseal (or Hydrastis canadensis) – a herb from the buttercup family promoted for treating many conditions, including cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, "evidence does not support claims that goldenseal is effective in treating cancer or other diseases. Goldenseal can have toxic side effects, and high doses can cause death."[84]

- Gotu kola – a swamp plant native to parts of Asia and Africa. Supplements made from it are promoted as cancer treatment; however according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims of its effectiveness for treating cancer or any other disease in humans".[85]

- Grapes – fruit, popularized for supposed anti-cancer effect by Johanna Brandt (1876–1964) who championed a "grape diet", and promoted more recently in the form of grape seed extract (GSE). According to the American Cancer Society, "there is very little reliable scientific evidence available at this time that drinking red wine, eating grapes, or following the grape diet can prevent or treat cancer in people".[86]

- 'Inonotus obliquus' – commonly known as chaga mushroom. Chaga has been used as a folk remedy in Russia and Siberia since the 16th century.[87] According to the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, "no clinical trials have been conducted to assess chaga's safety and efficacy for disease prevention or for the treatment of cancer, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes". They caution that the mushroom extract can interact with other drugs.[88]

- Juice Plus – a branded line of dietary supplements containing concentrated fruit and vegetable juice extract. In October 2009, Barrie R. Cassileth, Chair and Chief of Integrative Medicine at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, cautioned that while Juice Plus is being "aggressively promoted to cancer patients based on claims of antioxidant effects", the supplement should not be taken by patients because it can interfere with chemotherapy, nor should it be considered a substitute for fruits and vegetables.[89]

- Juicing (or Juice Therapy) – the practice of consuming juice made from raw fruit and vegetables. This has been claimed to bring many benefits such as slowing aging or curing cancer; however, according to the American Cancer Society, "there is no convincing scientific evidence that extracted juices are healthier than whole foods".[90]

- Kombucha – a fermented tea that has been promoted as a "cure all" for many conditions. According to the American Cancer Society: "Available scientific evidence does not support claims that Kombucha tea promotes good health, prevents any ailments, or [...] works to treat cancer or any other disease. Serious side effects and occasional deaths have been linked with drinking Kombucha tea."[91]

- Mangosteen – a fruit native to Southeast Asia which is promoted as a "superfruit" and in products such as XanGo Juice for treating a variety of human ailments. According to the American Cancer Society, "there is no reliable evidence that mangosteen juice, puree, or bark is effective as a treatment for cancer in humans".[92]

- Mistletoe (or Iscador) – a plant used in Anthroposophical medicine, proposed as a cancer cure by Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), who believed it needed to be harvested when planetary alignment most influenced its potency. According to the American Cancer Society, "available evidence from well-designed clinical trials does not support claims that mistletoe can improve length or quality of life".[93]

- Modified citrus pectin – a substance chemically extracted from citrus fruits and marketed in dietary supplement form as a treatment for prostate cancer and melanoma. According to Cancer Research UK, it has "not been shown to have any activity in fighting cancer in people".[94]

- Moxibustion – the practice, used in conjunction with acupuncture or acupressure, of burning dried-up mugwort near the patient. The American Cancer Society comments, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that moxibustion is effective in preventing or treating cancer or any other disease".[95]

- Mushrooms – promoted on the internet as useful for cancer treatment. According to Cancer Research UK, "there is currently no evidence that any type of mushroom or mushroom extract can prevent or cure cancer".[96]

- Nerium oleander (or oleander) – one of the most poisonous of commonly grown garden plants, is the basis of an extract which is promoted to treat cancer and other ailments. According to the American Cancer Society, "even a small amount of oleander can cause death", and "the effectiveness of oleander has not been proven".[97]

- Noni juice – juice derived from the fruit of the Morinda citrifolia tree indigenous to Southeast Asia, Australasia, and the Caribbean. Noni juice has been promoted as a cure for cancer. However, The American Cancer Society say "there is no reliable clinical evidence that noni juice is effective in preventing or treating cancer or any other disease in humans".[98]

- Pau d'arco – a large South American rainforest tree whose bark (sometimes brewed into "lapacho" tea) is promoted as a treatment for many ailments, including cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, "available evidence from well-designed, controlled studies does not support this substance as an effective treatment for cancer in humans".[99]

- Rauvolfia serpentina (or snakeroot) – a plant used as the basis of a herbal remedy that some believe may treat cancer. According to the American Cancer Society: "Available scientific evidence does not support claims that Indian snakeroot is effective in treating cancer [...] It also has many dangerous side effects and is likely to increase the risk of cancer."[100]

- Red clover (Trifolium pratense) – a European species of clover, promoted as a treatment for a variety of health conditions, including cancers. According to the American Cancer Society, "available clinical evidence does not show that red clover is effective in treating or preventing cancer, menopausal symptoms, or any other medical conditions."[101]

- Saw palmetto (or Serenoa repens) – a type of palm tree found growing in the southeastern United States. Its extract has been promoted as a prostate cancer medicine; however, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific studies do not support claims that saw palmetto can prevent or treat prostate cancer in humans".[102]

- Seasilver – an expensive dietary supplement made mostly from plant extracts and promoted by two US companies. Extravagant claims for its curative powers led to the prosecution and fining of the companies' owners.[22] According to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, "no studies have shown the efficacy of this costly product".[103]

- Soursop (or Graviola) – widely promoted on the internet as a cancer cure. According to the US Federal Trade Commission soursop extract is among those products for which there is "no credible scientific evidence" of an ability to "prevent, cure, or treat cancer of any kind".[104]

- Ukrain – the trademarked name of a drug (sometimes called "celandine") made from Chelidonium majus, a plant in the poppy family. The drug is promoted for its health giving powers and its ability to treat cancer; however according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that celandine is effective in treating cancer in humans".[105]

- Uncaria tomentosa (or cat's claw) – a woody vine found in the tropical jungles of South and Central America, which is promoted as a remedy for cancer and other disease. The American Cancer Society state: "Available scientific evidence also does not support cat's claw's effectiveness in preventing or treating cancer or any other disease. Cat's claw is linked to some serious side effects, although the extent of those effects is not known".[106]

- Venus flytrap – a carnivorous plant, the extract of which is promoted as a treatment for a variety of human ailments including skin cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that extract from the Venus flytrap plant is effective in treating skin cancer or any other type of cancer".[107]

- Walnuts – large, hard edible seeds of any tree of the genus Juglans. Black walnut has been promoted as a cancer cure on the basis it kills a "parasite" responsible for the disease. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that hulls from black walnuts remove parasites from the intestinal tract or that they are effective in treating cancer or any other disease".[108]

- Wheatgrass – a food made from grains of wheat. According to the American Cancer Society, although some wheatgrass champions claim it can "shrink" cancer tumors, "available scientific evidence does not support the idea that wheatgrass or the wheatgrass diet can cure or prevent disease".[109]

- Wild yam (or Chinese yam) – types of yam, the roots of which are made into creams and dietary supplements that are promoted for a variety of medicinal purposes, including cancer prevention. The American Cancer Society says of these products, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that they are safe or effective."[110]

Physical procedures

- Applied kinesiology – the practice of diagnosing and treating illness by touching and observing patients to detect meaningful signs in the muscles. Claims have been made that in a session, "spontaneous remission" of cancer can be observed. However according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support the claim that applied kinesiology can diagnose or treat cancer or other illness".[111]

- Chiropractic – the practice of manipulating the spine to treat many human ailments. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that chiropractic treatment cures cancer or any other life-threatening illness".[112]

- Craniosacral therapy (or CST) – a treatment devised by John Upledger in the 1970s. A CST practitioner will massage a patient's scalp in the belief that the precise positioning of their cranial bones can have a profound impact on their health. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that craniosacral therapy helps in treating cancer or any other disease".[113]

- Colon cleansing – the practice of cleansing the colon using laxatives and enemas to "detoxify" the body. Coffee enemas in particular are promoted as a cancer therapy. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that colon therapy is effective in treating cancer or any other disease".[114]

- Cupping – a procedure in which cups are used to create areas of suction on the body. Although widely used as an alternative cancer treatment the American Cancer Society say "available scientific evidence does not support claims that cupping has any health benefits".[115]

- Dance therapy –the use of dance or physical movement to improve physical or mental well-being. The American Cancer Society states, "Few scientific studies have been done to evaluate the effects of dance therapy on health, prevention, and recovery from illness. Clinical reports suggest dance therapy may be effective in improving self-esteem and reducing stress. As a form of exercise, dance therapy can be useful for both physical and emotional aspects of quality of life."[116] A Cochrane review found too few studies to draw any conclusions about what effects dance therapy has on psychological or physical outcomes in cancer patients.[117]

- Ear candling – an alternative medical technique in which lighted candles are placed in the ears for supposed therapeutic effect. The practice has been promoted with extravagant claims it can "purify the blood" or "cure" cancer, but Health Canada has found it has no health benefit; it does however carry a serious risk of injury.[118]

- Psychic surgery – a sleight-of-hand confidence trick in which the practitioner pretends to remove a lump of tissue (typically raw animal entrails bought from a butcher) from a person. No change occurs, so no effect is possible.[citation needed]

- Reiki – a procedure in which the practitioner might look at, blow on, tap and touch a patient in an attempt to affect the "energy" in their body. Although there is some evidence that reiki sessions are relaxing and so might improve general well-being, Cancer Research UK say that "there is no scientific evidence to prove that Reiki can prevent, treat or cure cancer or any other disease".[119]

- Shiatsu – a type of alternative medicine consisting of finger and palm pressure, stretches, and other massage techniques. According to Cancer Research UK, "there is no scientific evidence to prove that shiatsu can cure or prevent any type of disease, including cancer."[120]

Spiritual and mental healing

- Cancer guided imagery – the practice of attempting to treat cancer in oneself by imagining it away. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that imagery can influence the development or progress of cancer".[121]

- Faith healing – the attempt to cure disease by spiritual means, often by prayer or participation in religious ritual. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that faith healing can actually cure physical ailments".[122]

- Hypnosis – the induction of a deeply relaxed and yet alert mental state. Some practitioners have claimed hypnosis might help boost the immune system. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support the idea that hypnosis can influence the development or progression of cancer.".[123]

- Meditation (also Transcendental Meditation and Mindfulness) – mind-body practices in which patients attempt master their own mental processes. According to the American Cancer Society while meditation "may help to improve the quality of life for people with cancer", "available scientific evidence does not suggest that meditation is effective in treating cancer or any other disease."[124]

- Anti-cancer psychotherapy – a technique[125] claiming that a "cancer personality" caused cancer, which could be cured through talk therapy, e.g., that of the Simonton Cancer Center,[126] Bernie Siegel's "Exceptional Cancer Patients" (ECaP) or Deepak Chopra[16]

- Qigong – the practice of maintaining a meditative state while making gentle and fluid bodily movements, in an attempt to balance internal life energy. A systematic review of the effect of qigong exercises on cancer treatment concluded "the effectiveness of qigong in cancer care is not yet supported by the evidence from rigorous clinical trials."[127]

Synthetic chemicals and other substances

- 714-X – sometimes called "trimethylbicyclonitramineoheptane chloride", is a mixture of chemicals marketed commercially as a cure for many human ailments, including cancer. There is however no scientific evidence for any anti-cancer effect from 714-X.[128]

- Antineoplaston therapy – a form of chemotherapy promoted by the Burzynski clinic in Texas, United States. The American Cancer Society has found no evidence that antineoplastons have any beneficial effects in cancer, and it has recommended that people do not spend money on antineoplaston treatments.[129]

- Apitherapy – the use of products derived from bees, such as honey and bee venom, as a therapy. Apitherapy has been promoted for its anti-cancer effects; however according to the American Cancer Society, "there have been no clinical studies in humans showing that bee venom or other honeybee products are effective in preventing or treating cancer."[130]

- Cancell (also called Protocel, Sheridan's Formula, Jim's Juice, Crocinic Acid, JS–114, JS–101, 126–F, and Entelev) – a formula that has been promoted as a treatment for a wide range of diseases, including cancer. The American Cancer Society and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center recommend against the use of CanCell, as there is no evidence that it is effective in treating any disease, and its proposed method of action is not consistent with modern science.[131][132]

- Cell therapy – the practice of injecting cellular material from animals in an attempt to prevent or treat cancer. Although the use of human-to-human cell therapy has some established medical uses, the injection of animal material is, according to the American Cancer Society, not backed by any evidence of effectiveness, and "may in fact be lethal".[133]

- Caesium chloride – a toxic salt, promoted as a cancer cure (sometimes as "high pH therapy"), on the basis that it targets cancer cells. However, according to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, there is no evidence to support these claims, while serious adverse reactions have been reported.[134]

- Chelation therapy – removal of metals from the body by administering chelating agents. Chelation therapy is a legitimate therapy for heavy metal poisoning, but it has also been promoted as an alternative treatment for diseases including cancer. The American Cancer Society says: "Available scientific evidence does not support claims that it is effective for treating other conditions such as cancer. Chelation therapy can be toxic and has the potential to cause kidney damage, irregular heartbeat, and even death."[135]

- Cytokine therapy (or Klehr's autologous tumor therapy) – a so-called immunotherapy with a therapeutic substrate made of cytokines from the cancer patients' blood.[136][137] The inventor of this method is Nikolaus Walther Klehr, a dermatologist, who practiced it in his private clinics in Salzburg and Munich.[138] The patients were mainly from Slovenia, Poland and other Eastern European countries. Klehr is reported as claiming that his treatment leads to extended lifespan.[139] According to German Cancer Aid, the mechanism of action is unclear and the method's clinical effectiveness unproven.[140]

- Colloidal silver – liquid containing a suspension of silver particles, marketed as a treatment for cancer and other ailments. Quackwatch states that colloidal silver dietary supplements have not been found safe or effective for the treatment of any condition.[141]

- Coral calcium – a dietary supplement supposedly made from crushed coral and promoted with claims it could treat a number of diseases including cancer. A consumer advisory issued by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine stated "Consumers should be aware that claims that coral calcium can treat or cure cancer, multiple sclerosis, lupus, heart disease, or high blood pressure are not supported by existing scientific evidence".[142]

- Di Bella Therapy – a cocktail of vitamins, drugs and hormones devised by Luigi di Bella (1912–2003) and promoted as a cancer treatment. According to the American Cancer Society: "Available scientific evidence does not support claims that Di Bella therapy is effective in treating cancer. It can cause serious and harmful side effects. ... [These] may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, increased blood sugar levels, low blood pressure, sleepiness, and neurological symptoms."[143]

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (or DMSO) – an organosulfur compound that has been promoted as a treatment for cancer since the 1960s. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not suggest that DMSO is effective in treating cancer in humans".[144]

- Hydrazine sulfate – a chemical compound promoted (sometimes as "rocket fuel treatment") for its supposed ability to treat cancer. According to Cancer Research UK, although there is some evidence Hydrazine sulfate might help some people with cancer gain weight, "there is no evidence that it helps to treat cancer".[145]

- Insulin potentiation therapy – the practice of injecting insulin, usually alongside conventional cancer drugs, in the belief that this improves the overall effect of the treatment. Quackwatch state: "Insulin Potentiation Therapy (IPT) is one of several unproven, dangerous treatments that is promoted by a small group of practitioners without trustworthy evidence that it works." [146]

- Krebiozen (also known as Carcalon, creatine, substance X, or drug X) – a mineral oil-based liquid sold as an alternative cancer treatment. According to the American Cancer Society: "Available scientific evidence does not support claims that Krebiozen is effective in treating cancer or any other disease. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), creatine has been linked to several dangerous side effects."[147]

- Lipoic acid – an antioxidant available as a dietary supplement and claimed by proponents to be capable of slowing cancer progression. According to the American Cancer Society, "there is no reliable scientific evidence at this time that lipoic acid prevents the development or spread of cancer".[148]

- Miracle Mineral Supplement (or MMS) – a toxic solution of 28% sodium chlorite in distilled water, is promoted for treating cancer and other ailments. Quackwatch states, "the product, when used as directed, produces an industrial bleach that can cause serious harm to health".[149]

- Orthomolecular medicine (or Megavitamin therapy) – the use of high doses of vitamins, claimed by proponents to help cure cancer. The view of the medical community is that there is no evidence that these therapies are effective for treating any disease.[150]

- Oxygen therapy – in alternative medicine, the practice of injecting hydrogen peroxide, oxygenating blood, or administering oxygen under pressure to the rectum, vagina, or other bodily opening. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that putting oxygen-releasing chemicals into a person's body is effective in treating cancer", and some of these treatments can be dangerous.[151]

- Quercetin – a plant pigment used in dietary supplements that have been promoted for their ability to prevent and treat cancer; however, according to the American Cancer society, "there is no reliable clinical evidence that quercetin can prevent or treat cancer in humans".[152]

- Revici's Guided Chemotherapy – a practice in which a chemical mixture (usually including lipid alcohol and various metals) is given by mouth or injection, supposedly to cure cancer. The practice was devised by Emanuel Revici (1896–1997) and differs from modern chemotherapy despite being named with the same term. According to the American Cancer Society: "Available scientific evidence does not support claims that Revici's guided chemotherapy is effective in treating cancer or any other disease. It may also cause potentially serious side effects."[153]

- Shark cartilage – a dietary supplement made from ground shark skeleton, and promoted as a cancer treatment perhaps because of the mistaken notion that sharks do not get cancer. The Mayo Clinic conducted research and were "unable to demonstrate any suggestion of efficacy for this shark cartilage product in patients with advanced cancer".[154]

- Sodium bicarbonate (or baking soda) – the chemical compound with the formula NaHCO3, sometimes promoted as cure for cancer by alternative medical practitioners such as Tullio Simoncini. According to the American Cancer Society: "evidence also does not support the idea that sodium bicarbonate works as a treatment for any form of cancer or that it cures yeast or fungal infections. There is substantial evidence, however, that these claims are false."[155]

- Urine therapy (or urotherapy) – the practice of attempting to treat cancer – or other illnesses – by drinking, injecting or taking an enema of one's own urine, or by making and taking some derivative substance from it. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that urine or urea given in any form is helpful for cancer patients".[156]

- Vitacor – a type of vitamin supplement devised by Matthias Rath and heavily promoted on the internet, alongside other products from Rath's company under the "Cellular Health" brand, as a claimed treatment for cancer and other human disease; these claims have led to Rath's prosecution.[157] According to Cancer Research UK, "there is no scientific evidence at all to back up the claims that these products work".[158]

Areas of research

- Medical cannabis (especially for "Appetite Stimulation" and "Analgesia")[159]

- Selenium (Selenomethionine and Se-methylselenocysteine)[160][161]

- Nanobees

- Deoxycholic acid

- Dichloroacetic acid

- Curcumin

- Milk thistle

- Proton therapy

- HuaChanSu, traditional Chinese medicine extracted from the skin of the Bufo toad[162][163]

Due to the poor quality of most studies of complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of cancer pain, it is not possible to recommend them for the management of cancer pain. There is weak evidence for a modest benefit from hypnosis, supportive psychotherapy and cognitive therapy; studies of massage therapy produced mixed results and none found pain relief after 4 weeks; Reiki, and touch therapy results were inconclusive; acupuncture, the most studied such treatment, has demonstrated no benefit as an adjunct analgesic in cancer pain; the evidence for music therapy is equivocal; and some herbal interventions such as PC-SPES, mistletoe, and saw palmetto are known to be toxic to some cancer patients. The most promising evidence, though still weak, is for mind-body interventions such as biofeedback and relaxation techniques.[164]

Examples of complementary therapy

As stated in the scientific literature, the measures listed below are defined as 'complementary' because they are applied in conjunction with mainstream anti-cancer measures such as chemotherapy, in contrast to the ineffective therapies viewed as 'alternative' since they are offered as substitutes for mainstream measures.[6]

- Acupuncture may help with nausea but does not treat the disease.[166]

- Psychotherapy may reduce anxiety and improve quality of life as well as allow for improving patient moods.[16]

- Massage therapy may temporarily reduce pain.[164]

- In animals, some cannabinoids may stimulate appetite and reduce symptoms such as pain and nausea related to therapy, which helps reduce weight loss.[159] There is no evidence of similar effect for people.[167]

- Hypnosis and meditation may improve the quality of life of cancer patients.[168]

- Music therapy eases cancer-related symptoms by helping with mood disturbances.[16]

Alternative theories of cancer

Some alternative cancer treatments are based on unproven or disproven theories of how cancer begins or is sustained in the body. Some common concepts are:

- Mind-body connection: This idea says that cancer forms because of, or can be controlled through, the person's mental and emotional state. Treatments based on this idea are mind–body interventions. Proponents say that cancer forms because the person is unhappy or stressed, or that a positive attitude can cure cancer after it has formed. A typical claim is that stress, anger, fear, or sadness depresses the immune system, whereas that love, forgiveness, confidence, and happiness cause the immune system to improve, and that this improved immune system will destroy the cancer. This belief that generally boosting the immune system's activity will kill the cancer cells is not supported by any scientific research.[169] In fact, many cancers require the support of an active immune system (especially through inflammation) to establish the tumor microenvironment necessary for a tumor to grow.[170]

- Toxin theory of cancer: In this idea, the body's metabolic processes are overwhelmed by normal, everyday byproducts. These byproducts, called "toxins", are said to build up in the cells and cause cancer and other diseases through a process sometimes called autointoxication or autotoxemia. Treatments following this approach are usually aimed at detoxification or body cleansing, such as enemas.

- Low activity by the immune system: This claim asserts that if only the body's immune system were strong enough, it would kill the "invading" or "foreign" cancer. Unfortunately, most cancer cells retain normal cell characteristics, making them appear to the immune system to be a normal part of the body. Cancerous tumors also actively induce immune tolerance, which prevents the immune system from attacking them.[169]

Regulatory action

Government agencies around the world routinely investigate purported alternative cancer treatments in an effort to protect their citizens from fraud and abuse.

In 2008, the United States Federal Trade Commission acted against companies that made unsupported claims that their products, some of which included highly toxic chemicals, could cure cancer.[171] Targets included Omega Supply, Native Essence Herb Company, Daniel Chapter One, Gemtronics, Inc., Herbs for Cancer, Nu-Gen Nutrition, Inc., Westberry Enterprises, Inc., Jim Clark's All Natural Cancer Therapy, Bioque Technologies, Inc., Cleansing Time Pro, and Premium-essiac-tea-4less.

See also

- Diet and cancer

- Clinical trial

- Placebo effect

- Pseudoscience

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

References

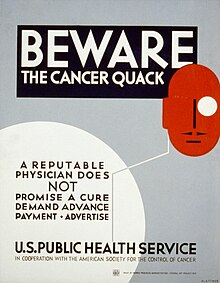

- ^ "Beware the cancer quack A reputable physician does not promise a cure, demand advance payment, advertise". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Schattner, Elaine (5 October 2010). "Who's a Survivor?". Slate Magazine.

- ^ "Cancer of All Sites - SEER Stat Fact Sheets". Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McMillen, Matt. "8 Common Surgery Complications". WebMD Feature. WebMD. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Vickers AJ, Kuo J, Cassileth BR (January 2006). "Unconventional anticancer agents: a systematic review of clinical trials". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (1): 136–40. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8406. PMC 1472241. PMID 16382123.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Cassileth BR (1996). "Alternative and Complementary Cancer Treatments". The Oncologist. 1 (3): 173–179. PMID 10387984.

- ^ "Overview of CAM in the United States: Recent History, Current Status, And Prospects for the Future". White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy. March 2002.

- ^ Wesa KM, Cassileth BR (September 2009). "Is there a role for complementary therapy in the management of leukemia?". Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 9 (9): 1241–9. doi:10.1586/era.09.100. PMC 2792198. PMID 19761428.

- ^ Cassileth BR, Schraub S, Robinson E, Vickers A (April 2001). "Alternative medicine use worldwide: the International Union Against Cancer survey". Cancer. 91 (7): 1390–3. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20010401)91:7<1390::AID-CNCR1143>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 11283941.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The difference between complementary and alternative therapies", Cancer Research UK, accessed 20 November, 2014

- ^ http://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(00)00099-X/abstract?cc=y?cc=y

- ^ https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2000/172/3/australian-oncologists-self-reported-knowledge-and-attitudes-about-non

- ^ a b Furnham A, Forey J (May 1994). "The attitudes, behaviors and beliefs of patients of conventional vs. complementary (alternative) medicine". J Clin Psychol. 50 (3): 458–69. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(199405)50:3<458::AID-JCLP2270500318>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 8071452.

- ^ a b Helyer LK, Chin S, Chui BK; et al. (2006). "The use of complementary and alternative medicines among patients with locally advanced breast cancer--a descriptive study". BMC Cancer. 6: 39. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-6-39. PMC 1475605. PMID 16504038.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Garland SN, Valentine D, Desai K; et al. (November 2013). "Complementary and alternative medicine use and benefit finding among cancer patients". J Altern Complement Med. 19 (11): 876–81. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0964. PMID 23777242.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Vickers, A. (2004). "Alternative Cancer Cures: 'Unproven' or 'Disproven'?". CA. 54 (2): 110–8. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.110. PMID 15061600.

- ^ Olson, James Stuart (2002). Bathsheba's breast: women, cancer & history. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 146. ISBN 0-8018-6936-6.

- ^ Green S (1997). "Pseudoscience in Alternative Medicine: Chelation Therapy, Antineoplastons, The Gerson Diet and Coffee Enemas". Skeptical Inquirer. 21 (5): 39.

- ^ Miller, Gabriel (2 September 2014), Asking the Experts: Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Cancer, Medscape, retrieved 7 September 2014

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Cassileth BR, Yarett IR (August 2012). "Cancer quackery: the persistent popularity of useless, irrational 'alternative' treatments". Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.). 26 (8): 754–8. PMID 22957409.

- ^ Lerner IJ (February 1984). "The whys of cancer quackery". Cancer. 53 (3 Suppl): 815–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3+<815::aid-cncr2820531334>3.0.co;2-u. PMID 6362828.

- ^ a b "Court orders Seasilver defendants to pay $120 million". Nutraceuticals World. 11 (6): 14. 2008.

- ^ a b Stephen Barrett, M.D. (1 March 2004). "Zoetron Therapy (Cell Specific Cancer Therapy)". Quackwatch. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Zoetron Cell Specific Cancer Therapy". BBB Business Review. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Harley Street practitioner claimed he could cure cancer and HIV with lifestyle changes and herbs, court hears". Daily Telegraph. 11 December 2013.

- ^ Cancer Act 1939 section 4, 7 May 2014

- ^ "Aromatherapy". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Ayurvedic medicine". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Cassileth, BR; Yarett, IR (2012). "Cancer quackery: The persistent popularity of useless, irrational 'alternative' treatments". Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.). 26 (8): 754–8. PMID 22957409.

- ^ a b "Herbal medicine". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Holistic Medicine". American Cancer Society. January 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Homeopathy". American Cancer Society. 12 February 2013. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Native American healing". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ "Naturopathic Medicine". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "An alkaline diet and cancer". Canadian Cancer Society. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Hübner, J; Marienfeld, S; Abbenhardt, C; Ulrich, CM; Löser, C (2012). "How useful are diets against cancer?". Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 137 (47): 2417–22. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1327276. PMID 23152069.

- ^ "What is the Budwig diet?". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Fasting". American Cancer Society. February 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Stephen Barrett, M.D. (29 May 2003). "Rev. George M. Malkmus and his Hallelujah Diet". Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Jean-Marie Abgrall (1 January 2000). Healing Or Stealing?: Medical Charlatans in the New Age. Algora Publishing. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-1-892941-28-2.

- ^ Esko, Edward; Kushi, Michio (1991). The macrobiotic approach to cancer: towards preventing and controlling cancer with diet and lifestyle. Wayne, N.J: Avery Pub. Group. ISBN 0-89529-486-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Macrobiotic diet". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Stephen Barrett, M.D. (11 December 2001). "The Moerman Diet". Quackwatch. Retrieved May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "'Superfoods' and cancer". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "BioResonance Therapy". Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. 29 May 2012. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Kempf, EJ (1906). "European Medicine: A Résumé of Medical Progress During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries". Journal of the Medical Library Association. 4 (1): 238. PMC 1692368. PMID 18340885.

The electrohomeopathic system is an invention of Count Mattei who prates of 'red,' 'blue,' and 'green' electricity, a theory that, in spite of its utter idiocy, has attracted a considerable following and earned a large fortune for its chief promoter.

- ^ Barrett, Stephen (July 2009). "Some Notes on the Quantum Xrroid (QXCI) and William C. Nelson". Quackwatch. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Light Therapy". American Cancer Society. 14 April 2011. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Magnetic Therapy". American Cancer Society. December 2012. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Stephen Barrett, M.D. (15 February 2002). "Some Notes on Wilhelm Reich, M.D". Quackwatch. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Polarity Therapy". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ "Rife machines and cancer". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Therapeutic Touch". American Cancer Society. April 2011. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Stephen Barrett, M.D. (23 October 2009). "The Bizarre Claims of Hulda Clark". Quackwatch.

- ^ "Metabolic Therapies". Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. 14 February 2013. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "What Gerson therapy is". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c "Metabolic Therapies". Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. 14 February 2013. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Hoxsey Therapy". Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. 29 October 2012. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Issels Treatment". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Mendick, Robert (30 March 2014). "Duped by the 'blood analyst' who says he can cure cancer". Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Livingston-Wheeler Therapy". American Cancer Society. 1 November 2008. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Stay Away from Dr. Lorraine Day". Quackwatch. 16 March 2013. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Black Cohosh". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Aloe". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Lerner, I. J. (1981). "Laetrile: A Lesson in Cancer Quackery". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 31 (2): 91–5. doi:10.3322/canjclin.31.2.91. PMID 6781723.

- ^ "Andrographis". Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. 13 February 2013. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Aveloz". American Cancer Society.

- ^ "Flower remedies". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Arney, Kat (25 July 2012). "Cannabis, cannabinoids and cancer – the evidence so far". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Cannabis and Cannabinoids". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Cancer Salves". American Cancer Society. March 2011. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Capsicum". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Ernst, Edzard (2009). "Carctol: Profit before Patients?". Breast Care. 4 (1): 31–33. doi:10.1159/000193025. PMC 2942009. PMID 20877681.

- ^ "Cassava". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ "Castor Oil". American Cancer Society. March 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ "Chaparral". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Chlorella". American Cancer Society. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Echinacea". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Ellagic acid". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "187 Fake Cancer "Cures" Consumers Should Avoid". Guidance, Compliance & Regulatory Information. USFDA. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Ginger". American Cancer Society. May 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ "Ginseng". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Glyconutrients". Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center. 11 October 2012. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Goldenseal". American Cancer Society. 28 November 2008. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Gotu Kola". American Cancer Society. 28 November 2011. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Grapes". American Cancer Society. 1 November 2011. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Youn, Myung-Ja; Kim, JK; Park, SY; Kim, Y; Kim, SJ; Lee, JS; Chai, KY; Kim, HJ; Cui, MX; So, HS; Kim, KY; Park, R (2008). "Chaga mushroom (Inonotus obliquus ) induces G0/G1 arrest and apoptosis in human hepatoma HepG2 cells". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (4): 511–7. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.511. PMC 2681140. PMID 18203281.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Chaga Mushroom". Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center. 18 July 2011. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Cassileth, B (2009). "Juice Plus". Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.). 23 (11): 987. PMID 19947351.

- ^ "Juicing". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Kombucha Tea". American Cancer Society. 21 October 2010. Retrieved August 2013.