2022 Yangtse clash

| 2022 Yangtse clash | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sino-Indian border dispute | |||||||||

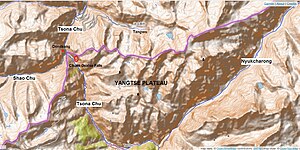

A map of the Yangtse region in Tawang showing the alignment of the LAC (marked with violet) in the vicinity of the Chumi Gyatse Falls. The clash occurred near the border ridge at 4,700 metres (15,400 ft) elevation.[1] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 34 injured (at least 6 serious)[2][3] | 40 injured [2] | ||||||||

The Yangtse clash of 9 December 2022 occurred at night between the troops of the Indian Army and the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) along their mutually contested Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the Yangtse region of Tawang in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. Violent clashes ensued after the two armies confronted each other with nail-studded clubs and other melee weapons near positions on a border ridgeline in close vicinity of the revered Buddhist site of Chumi Gyatse Falls. The border incident marked the most serious clash between the two armies along their undemarcated frontier since the Galwan Valley clash in June 2020, which had led to the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers and an unknown number of dead on the Chinese side.

Independent researchers using satellite imagery found evidence of Chinese troops, numbering about 300 according to reports, from a newly constructed border village moving up towards two Indian outposts at about 4,700 metres (15,400 ft) elevation. This provoked a clash according to the Indian government, which necessitated sending reinforcements from a forward base.[1] Spiked clubs studded with nails and other melee weapons were used in a skirmish causing a large number of injuries on both sides. Six Indian soldiers with severe injuries were flown to Guwahati for medical treatment. The casualties on the Chinese side have not been formally disclosed. The Chinese PLA has claimed that the Indian troops transgressed the border while their troops were performing customary patrol duty on their side of the border. This did not receive corroboration from the researchers.[1]

Yangtse, besides the larger Arunachal Pradesh region, had been the site of several such clashes in the period leading up to the latest incident. It had been recognised as one of the twelve contested border regions by the two countries in 1995. The border region is part of the Tawang district of Arunachal Pradesh, which is an important centre of Tibetan Buddhism, and has been claimed by China as part of its larger claim on Arunachal Pradesh, which it avers to be a part of South Tibet.

Sino-Indian frontier and geography[edit]

The McMahon Line[edit]

The Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the eastern sector of the border is broadly the McMahon Line agreed between British India and Tibet in 1914. Even though China regards the line as "illegal", on the grounds that Tibet was not an independent power, it agrees to abide by it as an LAC.[4] However, the line has never been demarcated on the ground and the inadequate surveying of 1914 leaves several areas uncertain, open to dispute between the two sides.[5][6] China also has an underlying claim to the entire state of Arunachal Pradesh, which it calls "South Tibet", and the claim is especially strong for the Tawang district, which was the birthplace of the 6th Dalai Lama of Tibet. The Tawang area was indeed under some form of suzerainty of Tibet at that time, but it was relinquished by Tibet in signing the agreement for the McMahon Line.[7]

Yangtse plateau and environs[edit]

Yangtse, the region which was the site of the clash, is essentially a plateau that adjoins the LAC. It is part of a larger area called Mago-Chuna in the mountainous and thickly forested part of the Tawang district.[9] Yangtse is bordered to the north by an LAC that is a continuous ridgeline of high mountain peaks that range in elevation from 14,000 feet (4,300 metres) to over 17,000 feet (5,200 metres). The ridgeline, with its crest reaching an elevation of over 17,500 feet (5,300 metres), roughly runs in a southwest-northeast direction to the Tulung La mountain pass, and affords observation over much of the surrounding area, including the roads leading to the all-important Sela pass, which provides India's gateway to the Tawang region.[1][10] The Tsona Chu river meanders through Tsona County in southern Tibet before cutting through the Yangtse ridgeline near the Chumi Gyatse Falls, and entering Tawang.[9][10] As of December 2022, Yangtse is one of the 25 contested border regions between India and China, and is mutually recognised as such by the two countries.[11]

The Chumi Gyatse Falls, at about 250 metres (820 ft) from the LAC, form the most prominent landmark in Yangtse,[12] and mark the juncture between the two prominent ridgelines of the area; namely, the Bum La ridgeline to its southwest, and the Tulung La ridgeline to its northeast.[10] The McMahon line at Yangtse is coterminous with the two foregoing ridgelines.[10] It underwent a material deviation in Yangtse in 1986, when Indian troops, in retaliation to Chinese occupation of the Wangdung pasture,[a] moved in Yangtse and occupied the stretch to the north of the hitherto prevailing line around Chumi Gyatse Falls.[10][13] The McMahon line in this area was thus altered.[10]

The control of the Tulung La ridgeline accrues an advantage of military high ground to the Indian troops in Yangtse. Indians maintain a network of layered defences in the region, with a small detachment of forward troops maintaining a chain of six forward defensive outposts on the ridgeline. Although lightly held, these serve to establish the extent of its frontier with China.[1] Complementing the outposts is an Indian forward base of about battalion strength, emplaced about 1.5 km (0.9 mi) south of the ridge.[1] India also maintains a more significant military presence in valleys adjoining the Yangtse plateau, with precarious steep dirt tracks providing the only access to the higher ground.[1] In contrast, the Chinese hold positions at lower elevations on the plateau, which places its troops at a tactical disadvantage.[1] However, qualitative improvements to military and transport infrastructure on the Chinese side of the border accruing from its investments has greatly enhanced its capacity to mobilize troops.[1]

Background and significance[edit]

The bilateral relations between India and China have for a long time been marred by considerable mistrust and suspicion, with the rancorous border dispute occupying the foreground.[14][15] Whereas India has pushed for the delineation of the LAC, the Chinese have invariably demurred. Despite multiple rounds of negotiations, and an agreement in 2005 requisitioning the enunciation of parameters and principles for delineating and demarcating the LAC, the two sides have not made any tangible headway on the question.[14][16]

While the McMahon line placed the border state of Arunachal Pradesh on the Indian side, China has staked formal claim to the entirety of the region, which it has esteemed as an extension of southern Tibet.[17] The region of Tawang in particular has enticed Chinese interest for its politico-religious symbolism, besides its strategic significance.[18][15]

The region is home to a significant ethnic Monpa population, who practise Tibetan Buddhism,[19] without actually considering themselves ethnic Tibetans;[20] it hosts the Galden Namgey Lhatse Monastery, which is India's largest, and Tibetan Buddhism's most important monastery after Lhasa's Potala Palace.[21][15] It also boasts of the distinction of being the birthplace of Tsangyang Gyatso, the 6th Dalai Lama. The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, had also dwelled in Tawang, after the Chinese annexation of Tibet forced him to go into exile in 1959.[17][15] India had extended its sovereignty over Tawang in February 1951.[20] China believes that its control over Tawang would stiffen its control over the Tibet Autonomous Region, besides providing it with the gateway to the strategic Brahmaputra valley.[17] India dismisses China's claim over Arunachal Pradesh as "non-substantial", and over Tawang as "only ecclesial".[17]

In mid-2020, India accused China of precipitating the 2020–2021 military standoff at several locations along the LAC in Ladakh, giving rise to a series of clashes between the two belligerents. The Galwan Valley clash in June that same year, in particular, engendered the most serious border crisis since 1967, marking the first combat fatalities since 1975, with 20 dead on the Indian side and an unknown number of dead on the Chinese side.[15] In January 2021, a face-off transpired between the two armies at Naku La in Sikkim that caused several non-fatal casualties on both sides.[15]

Yangtse was one of the twelve regions along the LAC that a Joint Working Committee in August 1995 had recognised as disputed border area between India and China.[22] India had established military control over the area in 1986 in the wake of the Sumdorong Chu standoff. The region is home to the Chumi Gyatse Falls. The falls are a series of 108 waterfalls on the border, colloquially described as the Holy Waterfalls. The falls are esteemed as sacred and revered by the ethnic Monpas, who identify its genesis to a showdown between a "Bon Lama" (monk) and Padmasambhava, who is considered by the practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism to be the second Buddha. Indian officials say that the Chinese essay to disseminate erroneous notions about the birthplace of Padmasambhava, tracing it to Tibet, as against his actual birthplace Odisha, to justify their claims to the pastures in Yangtse.[12]

In the wake of the 2020 Galwan clash, Yangtse became a region of renewed Sino-Indian focus and witnessed extensive military activities from the two armies. The Chinese undertook work on developing a Xiaokang (a Chinese term signifying moderate prosperity) border village in Tangwu, Tsona County, near to the LAC in the area, and followed it up with the construction of a sealed road connecting the village to its encampment within a hundred and fifty metres from the Tulung La ridgeline. The Indians, on their part, increased their military presence in the area, besides undertaking to augment its military infrastructure along the border, with a special focus on augmenting surveillance capabilities.[23]

In October 2021, Indian media reported that Yangtse was the site of a brief altercation between the Chinese and Indian troops after a nigh company sized Chinese force was confronted by an Indian patrolling unit, leading to a physical brawl which was eventually defused by the intervention of local military commanders. The incident had coincided with the 13th rounds of talks at corps commander level which were to happen a few days later to find a resolution to the 2020–2021 military standoff.[11] Writing in the wake of the altercation, a correspondent to The Tribune reported that India and China had both deployed an overall strength of about 3,000–3,500 troops to the area, underscoring the strategic importance that the two sides attached to the region.[9]

An inquiry into the border incidents by CNN-News18 found that in the two decades preceding to the clash at Yangtse, border incidents between India and China had been becoming a frequent affair in the region, leading to instances of confrontations of varying severity. These typically recurred twice yearly in the periods preceding and following the onset of winter. It noted that the Chinese had, in recent years, turned to sending a large force of several hundred troops for incursions across the LAC at Yangste with a mix of many types of melee weapons and taser guns.[24]

Clash[edit]

The clash along the LAC in Yangtse sprang from the premeditated initiative of the Chinese PLA, which moved a large body of its ground troops in the time leading up to the incident from its lodgement in the newly constructed border village of Tangwu to along the road leading towards its encampment on the declivity of the Tulung La ridge.[1][25] Once there, the Chinese, numbering about 300 men, and armed with nail-spiked clubs, monkey fists and taser guns, advanced upon two of India's forward outposts spaced about a kilometer apart, and located at an elevation of about 4,700 metres (15,400 ft) along the ridgeline which formed its frontier with India.[1] Independent researchers from the Canberra-based think tank Australian Strategic Policy Institute in their analysis of satellite images of the area produced five days after the incident found evidence of the Chinese advance towards the two Indian outposts in the form of well-trodden paths leading uphill off the road terminus to the ridgeline.[1]

Chinese foray towards the Indian positions in the predawn hours of 9 December 2022 prompted a confrontation with the Indians manning their outpost line on the border ridgeline, and eventually touched off an engagement that saw both sides fight hand-to-hand with an array of melee weapons.[26] Indian reinforcements had arrived from an adjacent forward base within the first half-hour, and the fighting lasted for an hour before troop disengagement defused the situation.[26] Local army commanders of the two sides convened a flag meeting between their border representatives at the Bum La pass in the aftermath of the incident on 11 December 2022 to resolve the dispute.[27][25]

With numerous injuries sustained by both sides in consequence of the fighting, the border incident marked the most serious clash between the Chinese and the Indian armies along their undemarcated frontier since the Galwan Valley clash in June 2020.[1]

Media accounts[edit]

Indian media accounts of the incident state that the allure of the high ground provided the animus for China's bellicose attempt to change the status quo of the Sino-Indian frontier in Yangtse.[29][24][27] The Chinese amassed several hundred troops under darkness and dense fog, and marched to confront a small detachment of Indian troops, who are reported to have numbered about 50, around their vantage high ground positions on the border ridgeline.[25] The Indians, who had been tracking the Chinese movement with thermal imaging devices, instinctively responded by forming a human chain to encumber Chinese advance.[25] Verbal recriminations over the patrolling rights to the area soon followed when the Chinese staked their claim to the area and sought an Indian withdrawal from it to no avail, however, as the Indians held their ground.[27] Matters soon turned to violence, with stone pelting and bodily encounters between them. Amidst this scuffle, a denser Chinese force that had postured behind the first lines and hid from view came forth armed with improvised melee weapons and taser guns.[25] Indian reinforcements that had been hurried up from their command post to augment the embattled frontline troops soon arrived, and a clash ensued with both sides becoming embroiled in vicious hand-to-hand combat. The Chinese force was physically repelled and overwhelmed within a half hour, and eventually retreated back to its encampment on the decline of the ridge. The Print, citing Indian military sources, reported that while the Indians did not possess taser guns, they had "everything and more than what the Chinese had" for fighting.[26]

The clash, which lasted for an hour, caused both sides numerous injuries, with one estimate being 34 injured on the Indian side, and nearly 40 on the Chinese.[2] At least 6 Indian soldiers sustained grievous wounds in combat and were flown to the Guwahati-based Indian army's 151 base hospital for treatment.[3][30] Indian estimates of the strength of the attacking Chinese force vary from a minimum of 200 to a higher count of about 600 troops.[26][31] The border clash embroiled Indian troops from three discrete combat units; namely, the Jammu and Kashmir Rifles, Jat Regiment and Sikh Light Infantry. One of these units was in the process of being relieved, and replaced by another, before the clash intervened, embroiling all three of them.[32]

US News & World Report revealed in 2023 that the US shared real-time satellite intelligence about the Chinese troop deployments, which helped India prepare better for the clash.[33][b]

Delayed Indian admission[edit]

The news of a nocturnal clash having transpired between the troops of the Indian and Chinese armies on 9 December 2022 along the LAC in Yangtse was formally disclosed by Indian officials only in the late evening of 12 December 2022, over three days after the clash had actually occurred.[30] Indian security analysts point out that the Indian government deliberately withheld the news, with some imputing it to its apprehension that a border crisis could garner mainstream media attention, dwarfing interest in its electoral success in the recently concluded 2022 Gujarat Legislative Assembly election; while others imputed it to its predisposition to hush up reports of border clashes with China for fear of being construed politically weak or goaded by public into an overreaction.[30]

Indian officials operating under the injunctions of the government came out with a brief statement on the border incident, after an acquaintance of one of the injured soldiers had broken the news of the clash on Twitter, tagging Rahul Gandhi and other prominent opposition leaders in the tweet that questioned the media's silence over it. The local revelation was followed soon afterwards by an article in The Tribune, which covered the story. Media queries a day before had met with a denial by the Indian government.[30]

Official accounts[edit]

The Indian statement stated that the Chinese troops had "contacted the LAC" in Tawang, prompting a "firm and resolute" response by the Indian troops, resulting in a face-off that caused a few "minor" casualties on both sides, adding that troop disengagement eventually defused the military situation, and that a flag meeting was held in its aftermath.[30]

While addressing the lawmakers in Parliament a day later on the issue, India's defence minister Rajnath Singh stated that the clash broke out after Chinese troops essayed to change the status quo of the disputed border in Yangtse by encroaching on Indian territory, and that this had been confounded by the Indian troops.[15] Without disclosing all the details of the incident, Singh added that the physical brawl did not result in any fatal or grievous injury to any Indian soldier, and that his government had reached out to Chinese officials on the issue through diplomatic channels.[30][15][34]

The PLA's Western Theatre Command spokesman, Colonel Long Shaohua, gave a diverging account of the chain of events that had transpired, saying that its troops had been undertaking normal patrol duties on its side of the LAC, in the Dongzhang area,[c] when Indian troops crossing the border intercepted them. "Our response was professional, standardized and powerful, and we have stabilized the situation on the ground," he said, adding that troop disengagement has since ensued.[15][34]

Commenting on the incident at a daily press briefing, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin stated that "the present situation on the China-India border is peaceful and stable overall," and that the two sides "maintained unobstructed dialogue on the border issue through diplomatic and military channels", while enjoining the Indian government to "earnestly implement the important consensus reached by both leaders, strictly abide by the spirit of the agreements and accords signed by both sides, and together uphold the peace and tranquility of the China-India border region."[35]

Reactions[edit]

Commenting on the incident, U.S. State Department spokesperson Ned Price stated that his government was following the news of the clash, and that it denounced "unilateral attempts to advance territorial claims by incursions, military or civilian, across the border at the established Line of Actual Control", and that it would rather have the two countries use extant bilateral channels to discuss boundary-related disputes.[34]

The Pentagon press secretary, Patrick S. Ryder, stated that "We have seen the PRC (People’s Republic of China) continue to amass forces and build military infrastructure along the so-called LAC, but I would refer you to India in terms of their views," adding that "It does reflect though, and it’s important to point out the growing trend by the PRC to assert itself and to be provocative in areas directed towards US allies and our partners in the Indo Pacific. (...) And we fully support India’s ongoing efforts to de-escalate this situation."[36]

The UN Secretary-General's spokesperson Stéphane Dujarric stated that UN was cognizant of the reports of the clash and sought a de-escalation of the situation at the border.[37]

In India, the chief opposition party, Indian National Congress, said that the defence minister Rajnath Singh made an incomplete statement on the issue before the parliament houses, and accused the ruling BJP of not being forthcoming with the truth. Its members staged a walkout from the upper house Rajya Sabha in response to being denied permission to solicit clarification on Singh's statement. They were accompanied by the parliamentary members from a laundry list of other opposition parties.[37]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Better known as the "Sumdorong Chu standoff", this confrontation was arguably the largest military confrontation between the two sides in between the 1962 Sino-Indian War and the 2020–2021 China–India skirmishes.

- ^ This was under the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement on Geospatial Cooperation (BECA) signed by the two countries in October 2020.

- ^ The Chinese refer to Yangtse as the Dongzhang area (Domtsang in the Tibetan language).

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ruser, Nathan; Grewal, Baani (December 2022), Zooming into the Tawang border skirmishes, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Sec. "The Recent Skirmish"

- ^ a b c Banerjee, Ajay (13 December 2022). "34 Indian, 40 Chinese soldiers injured; Tawang clash was building up since October". The Tribune.

- ^ a b Wallen, Joe; Lateef, Samaan (12 December 2022). "Six Indian soldiers severely injured in border skirmish with Chinese troops". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Liegl, Markus B. (2017). China's Use of Military Force in Foreign Affairs The Dragon Strikes. Taylor & Francis. p. 147. ISBN 9781315529318.

- ^ Eekelen, Willem van (2015). Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China A New Look at Asian Relationships. Brill. p. 128. ISBN 9789004304314.

- ^ Kingsbury, Robert C. (1974). South Asia in Maps. Denoyer-Geppert. p. 26.

- ^ Karunakar, Gupta (1971). "The McMahon Line 1911–45: The British Legacy". The China Quarterly (47). The China Quarterly, Cambridge University Press: 523–527. JSTOR 652324.

- ^ Large Scale International Boundaries (LSIB), Europe and Asia, 2012, EarthWorks, Stanford University, 2012.

- ^ a b c Banerjee, Ajay (31 October 2021). "Key Indian post at 17K ft that China wants to occupy". The Tribune.

- ^ a b c d e f Desai, Nature (21 October 2022). "China isn't done yet in Arunachal Pradesh". The Times of India, TOI+.

- ^ a b "Why Chinese PLA troops target Yangtse, one of 25 contested areas". The Indian Express. 15 December 2022.

- ^ a b Hasnat, Karishma (20 October 2020). "This Arunachal waterfall near LAC is being developed for tourism. But China 'keeping an eye'". The Print.

- ^ Shantanu Dayal (15 December 2022), "Why Yangtse? At LAC, a long saga of military grit", The Hindustan Times, ProQuest 2754518605

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schmall, Emily; Yasir, Sameer (13 December 2022). "Indian and Chinese Soldiers Again Trade Blows at Disputed Border". The New York Times.

- ^ Jetly, Rajshree; D'Souza, Shanthie Mariet, eds. (2013). Perspectives on South Asian Security. World Scientific. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9789814407366.

- ^ a b c d Ragi, Sangit K. (2017). "India-China relations in the 21st century: Conflicts and cooperation". In Sangit K. Ragi; Sunil Sondhi; Vidhan Pathak (eds.). Imagining India as a Global Power Prospects and Challenges. Taylor & Francis. p. 34. ISBN 9781351609159.

- ^ Gupta, Yogesh (15 December 2022). "A troubled China risked Tawang skirmish". Deccan Herald.

- ^ Jeffries, Ian (2010). Political Developments in Contemporary China A Guide. Taylor & Francis. p. 315. ISBN 9781136965203.

- ^ a b Lintner, Bertil (2018). China's India War Collision Course on the Roof of the World. Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780199091638.

- ^ Jokela, Juha (24 February 2016). The Role of the European Union in Asia China and India as Strategic Partners. Taylor & Francis. p. 194. ISBN 9781317017172.

- ^ Joshi, Manoj (2022). Understanding the India-China Border The Enduring Threat of War in High Himalaya. Hurst. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9781787388833.

- ^ Bhalla, Abhishek (13 December 2022). "Alarm bells rang last year in Yangste, place of religious importance". India Today.

- ^ a b Dutta, Amrita Nayak (14 December 2022). "India-China Border Clash: 20 Years On, Why Tawang's Yangtse is Still a Raw Nerve for Neighbour". CNN-News18.

- ^ a b c d e Sagar, Pradip R. (16 December 2022). "The Tawang tangle on India-China border". India Today.

- ^ a b c d Philip, Snehesh Alex (12 December 2022). "Arunachal clash: Over 200 PLA troops came with spiked clubs, taser guns, Indian soldiers hit back". The Print.

- ^ a b c Sharma, Ankur (13 December 2022). "What Triggered The Clashes at LAC? News18 Brings You The Inside Story". CNN-News18.

- ^ Patranobis, Sutirtho (12 January 2016). "India, China discussing new meeting point for military personnel". The Hindustan Times.

- ^ Baruah, Sanjib Kr. (1 January 2023). "China's latest Arunachal provocation has serious implications". The Week.

- ^ a b c d e f Bedi, Rahul (13 December 2022). "Timing of Official Disclosure of India-China Clash at Tawang Raises Questions". The Wire.

- ^ Krishnan, Ananth (13 December 2022). "As India pushes China back on LAC, PLA's growing transgressions risk 'strategic miscalculation'". The Hindu.

- ^ Dhar, Aniruddha (13 December 2022). "Jat regiment, Indian Army's 2 other units took on China troops in Arunachal – 10 points". The Hindustan Times.

- ^ U.S. Intel Helped India Rout China in 2022 Border Clash: Sources, US News & World Repor, 20 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Saaliq, Shiekh (13 December 2022). "Indian, Chinese troops clash at border in fresh faceoff". The Washington Post. Associated Press.

- ^ Adlakha, Hemant (17 December 2022). "The Tawang Clash: The View From China". The Diplomat.

- ^ "'Encourage India, China to Utilise Existing Channels to Discuss Disputed Boundaries,' Says US". The Wire. Press Trust of India. 14 December 2022.

- ^ a b "India-China troops clash in Arunachal: 'PLA wanted to set up observation post on LAC'". The Times of India. 15 December 2022.