Communist Party of New Zealand

Communist Party of New Zealand | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | CPNZ |

| Founded | 26 March 1921 |

| Dissolved | 2 November 1994 |

| Succeeded by | Socialist Unity Party (1966) Organisation for Marxist Unity (1975) Socialist Workers Organization (1994) |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Far-left |

| Colours | Red |

The Communist Party of New Zealand (CPNZ) was a communist party in New Zealand which existed from 1921 to 1994. Although spurred to life by events in Soviet Russia in the aftermath of World War I, the party had roots in pre-existing revolutionary socialist and syndicalist organisations, including in particular the independent Wellington Socialist Party, supporters of the Industrial Workers of the World in the Auckland region, and a network of impossiblist study groups of miners on the west coast of the South Island.

Never high on the list of priorities of the Communist International, the Communist Party of Australia was considered an appendage of the CPNZ until 1928, when it began to function as a fully independent party. Party membership remained small, only briefly topping the 1,000 mark, with its members subjected to government repression and isolated by expulsions from the mainstream labour movement concentrated in the New Zealand Labour Party.

During the period of the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s, the CPNZ sided with the Chinese party headed by Mao Zedong. The party splintered into a multiplicity of tiny political parties after 1966 and no longer exists as an independent group.

History

Background

As the 20th Century dawned, New Zealand was recognised by adherents of International Socialism around the globe as a sort of laboratory test case of social democratic government in practice. One June 1901 pamphlet put to print by J.A. Wayland, proprietor of the mass circulation socialist weekly Appeal to Reason, detailed the ways in which the island nation of 720,000 had already passed extensive legislation for the benefit of wage workers, backed by 200 agents of the "Labour Intelligence Department."[1] While the country was declared "no Utopia," New Zealand nevertheless was said to have "no real want" and "no unemployment problem to solve."[1] Instead trade unions were not merely formally recognised but were pervasive and had managed to mitigate the class struggle through arbitration laws sanctioned by law, with disputes decided by three member courts of arbitration, each including representatives of capital, labour, and the courts as provided in the 1894 Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act.[2]

An extensive system of public works were in existence, governed by the principle of "fair work and fair pay."[3] More than 200 employment bureaus dotted the country, connecting every willing worker with a job.[4] Sweatshops were banned, as was systematic home manufacturing, with mandatory labelling of all products made outside of factories.[4] Wages were generally high and the 48-hour week said to be a local maximum.[5] The presence of "tramps" had been eliminated through town allotments of small homesteads to poor workers, granted through easily affordable perpetual leases.[6] The power of eminent domain had been assumed by the New Zealand parliament in 1896, allowing the state to assume ownership of large estates at their assessed price for division into small farms.[7]

State finance had been accomplished by a tax on land values and the establishment of a progressive income tax.[8] The national government itself owned and operated the railways, telegraph and telephone systems, schools, and postal savings banks throughout the country even before the landmark election of 1891.[9] Workers' compensation insurance to protect against injury was required by law, and low cost life insurance had been provided by the state since 1869. Old age pensions were provided to all New Zealanders 65 years of age or older who had been resident in the country for at least 25 years.[10]

"The New Zealanders are collectivists, although they adhere to the old party names of liberals and tories," the American examiners enthused, with the New Zealand Liberal Party reckoned as equivalent to the Fabian socialists of Great Britain.[10] Richard Seddon (1845–1906), Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1893 until his death in 1906, oversaw implementation of an array of social welfare programs as leader of the Liberal Government

This idyllic vision – which incidentally paid no attention to the treatment of or conditions endured by the indigenous Polynesian population – proved to be short-lived. With the eruption of World War I in 1914, New Zealand sent soldiers to Allied campaigns in Turkey, Palestine, and France and Flanders. Over 120,000 New Zealanders were enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, with about 100,000 men and women eventually serving as soldiers and nurses in Europe, out of a population of 1.14 million.[11] Of these, about 18,000 were killed in battle and another 41,000 felled by wounds or disease – a casualty rate approaching 60%.[11] Conscription was introduced in 1916, with the stream of volunteer enthusiasts exhausted.[12] As casualties continued to mount into 1917, public war-weariness set in, fuelling political discontent.[12] A revolutionary socialist movement began to emerge.

Establishment

There were isolated reflections of international radical tendencies present in New Zealand from shortly after the turn of the 20th century. The New Zealand Socialist Party (NZSP), founded in 1901, included in its ranks a left wing which eschewed political action, arguing that socialism could only be won by the direct efforts of the organised working class acting through their unions.[13]

Others adhered to the theories of Daniel DeLeon, which advocated the use of the ballot box for a revolutionary transformation of society leading to a socialist state governed by revolutionary industrial unions.[14] From 1911 the ideas of syndicalism began to gain a foothold in the Auckland area under the banner of the Industrial Workers of the World, while the anti-political impossibilist ideas of the Socialist Party of Great Britain made their mark upon others.[14] All of these tendencies would contribute adherents to the pioneer New Zealand communist movement.

Particularly worthy of note were a small network of Marxist study circles were formed during the wartime years, concentrated mainly in the small mining communities of the South Island.[15] Wartime violence and the October 1917 Revolution in Russia proved a stimulant to revolutionary ideas, drawing members to these groups, leading to their formal affiliation during the summer Christmas holiday of 1918 as the New Zealand Marxian Association (NZMA).[15] This group electing T. W. Feary as secretary of the organisation and in 1919 dispatched him and two others to North America to gain additional information on the revolutionary movement through the American and Canadian prism.[15]

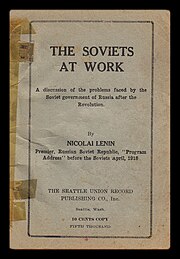

Visiting the Pacific Coast cities of San Francisco and Vancouver, Feary and his co-thinkers obtained copies of a number of influential publications, including Ten Days That Shook the World, a participant's account of the October Revolution by John Reed, and The Soviets at Work, a widely reprinted pamphlet by Lenin.[15] These were successfully smuggled back to New Zealand, with the Lenin tract immediately put into print in yet another new edition.[15]

Adding to the complexity of the fragmented radical movement was the Wellington Socialist Party, formerly a branch of the NZSP which had split with the national organisation in 1913 over the issue of electoral politics. While the main body of the NZSP had gone on to found the New Zealand Labour Party in 1916, the Wellington Socialist Party believed in direct action and use of the general strike for the intended overthrow of capitalism and had forced a split.[16] Suffering attenuation but surviving the war, this Wellington organisation would constitute the main component of the new Communist Party of New Zealand.[16]

By 1921 sentiment had begun to build for the establishment of a communist political party along those lines advocated by the fledgling Communist International. A preparatory conference was called for Easter weekend, 26–27 March 1921, in Wellington.[15] This preliminary gathering was followed with a formal organisational conference held on Saturday, 9 April, at Wellington Socialist Hall – headquarters of the Wellington Socialist Party – at which time the Communist Party of New Zealand (CPNZ) was formally established.[17]

Of the origins of the Communist Party, historian Kerry Taylor writes:

"The foundation of the CPNZ will always remain shrouded in a degree of mystery. No direct record of the event survives — the minutes have long since been lost and no reports appeared in the media at the time.... The precise nature of the discussion and debate is obscure but the delegates had before them the constitution of the Communist Party of Australia and a draft manifesto and constitution drawn up over the previous few months by members of the Wellington Socialist Party."[17]

E. J. Dyer of the capital city was elected as the first secretary of the new organisation.[15]

Early years

In contrast to demographic findings made of the early Communist Party of America, for example, the Communist movement in New Zealand was never dominated by Slavic, Scandinavian, and Jewish emigrants from the former Russian empire, with one academic study showing that a big majority of the movement's participants during the decade of the 1920s were either native New Zealanders by birth or first-generation immigrants from England, Scotland, Ireland, or Wales.[18]

The CPNZ participated in elections for the first time in 1923, with its inaugural candidate drawing an impressive 2,128 votes in a race for election to the Dunedin city council.[15]

Unable to take over the newspaper of the Federation of Labour, the Maoriland Worker, in 1924 the CPNZ established its own official publication, The Communist, published in Auckland.[19] Despite the establishment of this new central organ, the organisation remained highly decentralised in its formative years, with branches operating in virtual isolation and the small movement failing to achieve critical mass.[20] A conference was consequently held during the 1924 Christmas break, attended by delegates of the Communist Party of Australia (Hetty and Hector Ross), at which it was decided to make the CPNZ a subordinate section of the larger Australian party.[20] Harry Quaife from Australia also visited in 1925, and had "some success in putting Auckland communists on a more unified footing."[21]

This situation continued through all of 1925, only ending the year after following a six-month organising tour by Australian activist Norman Jeffrey,[20] a bow-tie wearing former "Wobbly" (IWW member).[21] In April 1926 a new monthly magazine was launched for the New Zealand communist movement, The Workers' Vanguard, published in the isolated inland mining town of Blackball, located on the rainy West Coast side of the South Island.[20] A return to independence of the New Zealand party shortly followed and by the end of 1926 headquarters of the CPNZ were moved from Wellington to Blackball.[20] They would remain there until returned to the North Island and the capital city in 1928.

Total membership of the party remained tiny in this period, with the CPNZ counting fewer than 100 members.[20] Despite its small size, the party nevertheless managed to exert a degree of influence within the national Miners' and Seamen's Unions.[20]

The party did not operate in a vacuum but was rather the object of official scrutiny from the start with the New Zealand Police and New Zealand Army both engaged in the systematic monitoring of radical activists, including those suspected of "using their influence to establish Bolshevism."[22]

Third Period (1928–1935)

Previously considered an insignificant adjunct of the Communist Party of Australia in the eyes of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI), early in 1928 the CPNZ received a cable from Moscow requesting that the party dispatch a delegate to the forthcoming 6th World Congress of the Comintern.[23] Twenty-eight-year-old Wellington activist Dick Griffin, a member of the Seamen's Union, was chosen as the party's first-ever delegate to a Comintern gathering in Moscow.[23] Griffin travelled circuitously to the Soviet Union, with his ocean voyage going first to Australia before heading to Great Britain via the Suez Canal.[23] British authorities were aware of his presence by the time he arrived, detaining him for questioning and seizing documents, but Griffin was allowed to depart in time to reach Moscow prior to 17 July opening of the World Congress.[23]

The 6th Congress of the Comintern is remembered for its launch of the ultra-radical analysis and tactics of the so-called Third Period, which posited the rapid decay of capitalism and the acceleration of the class struggle and coming of potential revolutionary situations. While in many countries this meant directives to immediately shatter joint work with social democratic political and trade union leaders, the Comintern's "Resolution on the Tasks of the Communist Party of New Zealand," brought back to Wellington by Griffin, maintained that New Zealand was still marked by "the steady upward swing of capitalist development, combined with relatively good conditions for the workers," thereby serving to "prevent the possibility of a general revolutionary situation in New Zealand."[24] Instead of consolidating itself for an envisioned revolutionary uprising, the CPNZ was directed to concentrate its attention on continued agitation and propaganda.[24]

Dick Griffin became the first full-time organiser of the CPNZ in May 1929.[25] In August of that same year he assumed the role of General Secretary of the organisation.[25]

It was only in March 1930 that the CPNZ received a communication from ECCI directing it to take on ultra-radical policies in accord the Third Period analysis.[26] The party's previous policies were deemed incorrect and the CPNZ was instructed to attempt to assume leadership of the New Zealand workers movement by working to "expose and destroy all the Labourite, pacifist, social democratic illusions about the possibility of solving social problems...under the existing political and economic regime."[27] This marked the actual beginning of sectarian Third Period tactics in New Zealand.

The CPNZ was beset by rapid membership turnover throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, with general secretary Griffin accused of operating a personal dictatorship, spurring rank-and-file discontent.[28] The CPNZ was also subjected to unrelenting police operations by the national government, including a July 1929 raid which seized the internal records and literature of the Wellington branch and the subsequent successful prosecution of five members of the governing Central Executive Committee for possession and sale of allegedly seditious literature.[28] Party leaders were particularly targeted, with three more members of the Central Executive Committee arrested in 1930, four more in 1931 and 1932, and all seven members in 1933.[29]

The party was further disorganised by the churn of its rank-and-file members in and out of the party, exemplified by the count of Wellington members booming from 51 in March to 80 by May 1931 before plummeting to just 25 in January 1932.[28] Things grew so bad that by October 1932 only one member of the Central Executive Committee had been a member of the party for longer than a year, with some members for as little as two months.[28] The party was impoverished, its coffers drained both by the cost of producing the Red Worker (rival publication to the mainstream trade unionist Maoriland Worker), and by courtroom losses in several libel cases brought against that publication.[28] Party publications were carefully scrutinised, with two issues of the Red Worker and a pamphlet found to be seditious in 1932 and those responsible for their publication jailed for more than a year.[29]

The CPNZ also lost its influence in the country's trade unions during the late 1920s and early 1930s owing to its rigid support for unpopular secondary strikes in solidarity with workers in other countries. This was epitomised by a 1929 call for a miners' strike in sympathy with mine and timber workers in Australia, which annihilated party influence among the miners of the South Island's West Coast and 1931 efforts to blackball a Japanese ship, which led to discord and alienation from the party in the Seamen's Union.[30]

"Freemanisation"

By the middle of 1933, the Communist Party of New Zealand was in crisis, with its entire Central Committee jailed for publication of the pamphlet Karl Marx and the Struggle of the Masses.[31] The New Zealand-born Fred Freeman was returned to the country to assume the position of general secretary following four years in Moscow at the service of the Comintern.[31] More politically astute and organisationally adroit than Griffin, Freeman promoted university graduates Clement Gordon Watson and his future wife, Elsie Farrelly, to positions of party leadership, where they were joined by party veteran Ernie Brooks.[31] This group of four would dominate CPNZ politics through the end of 1935.[31]

The operations of the CPNZ came to resemble those of larger and more efficient communist parties in other countries, with official directives and circulars issued systematically for the first time by the Central Committee to local party committees.[31] Representatives of the Central Committee also began to travel regularly to visit local party organisations.[31] Dues collecting and record-keeping of branches was made more regular and increased attention was paid to the problem of internal security in an effort to stave the crippling series of arrests that had swept the party.[32]

Comintern policy began to change in 1933 following the victory of the Nazi Party in Germany, leading to eventual advocacy of a so-called Popular Front against fascism by 1935. Under the Freeman leadership the CPNZ took the first tentative steps in this direction late in 1933 when the CPNZ approached the National Executive Committee of the New Zealand Labour Party with a proposal for a joint campaign against fascism.[33] No answer was given. Parallel appeals were made to several key trade unions, including the Miners, Seamen, and Dockworkers, with only the Miners providing a response.[34]

The CPNZ responded to the tacit rejection of their appeal by accelerating their efforts to drive a wedge between the rank and file and leadership of each of these organisations, a tactic euphemistically called the "United Front from Below."[35] The distrust and alienation between the Communist Party and the Labour Party leadership carried over through the November 1935 general election, during which the CPNZ made use of the slogan "Neither Reaction nor Labour" in the campaign.[20] The 1935 election ultimately resulted in a massive victory for the Labour Party, bringing it to power for the first time, and a grave failure for the CPNZ in its electoral efforts, with all four of the party's candidates faring so poorly at the polls that they failed to recover their electoral deposits.[36]

Popular Front period and World War II

The Communist Party of New Zealand had shown growth over the years of the Third Period, with the party's delegate to the 7th World Congress of the Comintern in Moscow, Leo Sim (pseudonym: Andrews), reporting there that party membership had increased by 600% from 1928 to 1935.[20] The reality was modest, with the party failing to achieve a membership of 400 — results which only were promising when compared to the nadir of the late 1920s.[37]

Dissatisfaction with Freeman's commanding leadership style grew in 1935 and 1936 and he landed on the wrong side of the Popular Front-driven Comintern decision that the CPNZ should seek formal affiliation with the Labour Party sooner rather than later.[38] Freeman came to be politically isolated, with the Auckland district of the party, backed by Lance Sharkey of the Communist Party of Australia, leading the charge for his removal as an alleged impediment to the new international line.[39] Freeman was removed from the party leadership late in 1936, suspended from the party soon thereafter for failing to accept this decision, and ultimately expelled late in 1937.[40]

In 1938 CPNZ headquarters were moved from the capital city of Wellington to the booming northern port city of Auckland and a new weekly was launched there in July 1939, People's Voice.[20] This headquarter city and official organ would remain constant for the rest of the party's institutional life.

In the summer of 1939 the CPNZ came into conflict with the government in the aftermath of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, to which the party responded with anti-war rhetoric while the governments of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union carved up spheres of influence in Europe. Tensions worsened in 1940, when Great Britain came under attack – a country to which New Zealanders felt a particular national affinity. Although membership in the CPNZ remained legal, People's Voice was suppressed by the government.[41]

The tide turned in June 1941 following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. At that time, in accord with Soviet foreign policy, the CPNZ became vocal supporters of the war effort, which combined with the country's new status of military allies with the Soviet Union paved the way for the New Zealand party's growth in membership and influence.[42] By 1945 party membership reached its all-time high of approximately 2,000, while circulation of People's Voice topped 14,000 copies per week.[42] This level of membership and support would continue through 1946, when new international circumstances would arise leading to the CPNZ's inexorable attrition.[42]

A Communist Party candidate stood in the Auckland West 1940 by-election held after Savage's death, although after the low number of votes received in the 1935 election, no Communist Party candidates stood in the 1938 election or the 1943 election.

Post-war era

The Communist Party stood candidates in general elections from the 1946 election to the 1969 election; particularly in the 1949 election, the 1960 election and the 1963 election; and in 3 by-elections; Brooklyn 1951 by-election, Grey Lynn 1963 by-election, and Otahuhu 1963 by-election. Candidates stood frequently in the Christchurch Central electorate (7 elections) and the Island Bay electorate (8 elections; often Ronald Smith). The highest vote was 534 for Vic Wilcox in the Arch Hill electorate in the 1946 election.[43]

The Communist Party experienced the loss of several prominent members including Sid Scott following Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin at the 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956 and the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution in November 1956.[44] As a result of these events, most of the intellectuals the CPNZ had attracted left the party while some erstwhile supporters founded new journals such as New Zealand Monthly Review, Comment, Socialist Forum and Here & Now.[citation needed]

Sino-Soviet split and factionalism

Next, in the early 1960s, the party experienced more internal strife due to the Sino-Soviet split. The party was divided between supporters of the Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev and those who claimed Khrushchev was a "revisionist" and chose instead to follow China under Mao Zedong. Subsequently, the CPNZ under the leadership of Victor Wilcox became the first official Communist party in the First World to side with Mao. The majority of the party and its newspaper The People's Voice adopted Maoism, while supporters of Khrushchev's Soviet Union (mainly Auckland trade unionists) split off to form the Socialist Unity Party.[44] The Communist Party also maintained warm ties with the Indonesian Communist Party and supported Indonesia during the Indonesian-Malaysian Confrontation (1963–1966). It also condemned the Indonesian mass killings that followed the alleged 30 September coup attempt as a right wing coup.[45]

Later, when Mao died, the Communist Party of New Zealand began to follow the lead of Enver Hoxha's Albania, which they considered to be the last truly Communist country in the world. Members of the CPNZ national leadership who continued to uphold the line of the post-Mao Chinese Communist Party including Wilcox were expelled, and formed the Preparatory Committee for the Formation of the Communist Party of New Zealand (Marxist–Leninist).[46]

Meanwhile, other former members of the CPNZ in Wellington, where the party branch had been expelled en masse in 1970, founded the Wellington Marxist Leninist Organisation, which in 1980 merged with the Northern Communist Organisation to form the Workers' Communist League (WCL).[44]

While the CPNZ never had mass influence or real political power, it pursued a Leninist vanguard party approach that involved trying to influence and penetrate the Labour Party, the New Zealand trade union movement, various single-issue protest groups and public opinion on foreign policy, industrial activity, opposition to New Zealand's involvement in the Vietnam War, Māori rights, the anti-Apartheid movement, feminism, and nuclear disarmament, and anti-colonial activism in the Pacific region; issues in which communists and non-communist left-wing elements found common cause.[47]

Decline and legacy

After the collapse of communist rule in Albania, the Communist Party of New Zealand gradually changed its views, renouncing its former support of Stalinism, Maoism, and Hoxhaism. Instead, under the leadership of its last general secretary, Grant Morgan, it developed a state capitalist analysis of the Stalinist states. The party now believed that the Soviet Union had never been socialist at all, not even in Stalin's time. Opponents of this change departed and established the Communist Party of Aotearoa (a Maoist group) and the Marxist–Leninist Collective (a Hoxhaist group).

The Communist Party of New Zealand eventually merged with the neo-Trotskyist International Socialist Organization on 2 November 1994.[48] The resultant party, known as the Socialist Workers Organization, evolved into the small but highly active Socialist Worker (Aotearoa). However, most of the ISO members split off again and resumed their own organisation. A number of SW members also split from the organisation in 2008 to form Socialist Aotearoa.[49] The SW voted to dissolve itself at its conference in January 2012.

Membership

| Part of a series on |

| Communist parties |

|---|

Year Membership Notes 1926 120 Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284. 1927 105 Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284. 1928 79 Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284. 1929 Decline due to loss of West Coast miners. 1930 62 "All-time low." Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284. 1931 81 Actually a Jan. 1932 count. Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284. 1932 129 Year end figure. Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284. 1933 1934 246 Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284. 1935 280 June count. Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284. 1936 353 Actually a Dec. 1935 count. Per Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284.

Electoral results (1935 and 1946–1969)

The party contested a number of elections with the following results:[43]

| Election | candidates | seats won | votes | percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1935 | 4 | 0 | 600 | 0.07 |

| 1946 | 3 | 0 | 1,181 | 0.11 |

| 1949 | 16 | 0 | 3,499 | 0.33 |

| 1951 | 4 | 0 | 528 | 0.05 |

| 1954 | 8 | 0 | 1,134 | 0.05 |

| 1957 | 5 | 0 | 706 | 0.06 |

| 1960 | 19 | 0 | 2,423 | 0.21 |

| 1963 | 23 | 0 | 3,167 | 0.26 |

| 1966 | 9 | 0 | 1,207 | 0.10 |

| 1969 | 4 | 0 | 418 | 0.03 |

Notable members

- Alexander Galbraith, founding member

- Bill Bland

- Jim Edwards

- Fred Hollows, member in the 1950s and 1960s

- Elsie Locke

- Hedwig Ross, founding member

- Rita Smith

- Hone Tuwhare

- Ron Smith, peace activist

- Fintan Patrick Walsh, founding member and trade unionist

- Vic Wilcox

- Rona Bailey[50]

- Sidney Wilfred Scott, party editor

- Gordon Harold Anderson, trade unionist

Footnotes

- ^ a b New Zealand in a Nutshell. Wayland's Monthly No. 14. Girard, KS: J.A. Wayland, June 1901; pp. 5–6.

- ^ New Zealand in a Nutshell, pp. 7, 21.

- ^ New Zealand in a Nutshell, p. 7.

- ^ a b New Zealand in a Nutshell, pg. 8.

- ^ New Zealand in a Nutshell, p. 9.

- ^ New Zealand in a Nutshell, pp. 10–11.

- ^ New Zealand in a Nutshell, p. 11.

- ^ New Zealand in a Nutshell, pp. 12–13.

- ^ New Zealand in a Nutshell, pp. 15–17, 34.

- ^ a b New Zealand in a Nutshell, p. 19.

- ^ a b "First World War – Overview," History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage, p. 1.

- ^ a b "First World War – Overview," p. 5.

- ^ Kerry Taylor, "'Our Motto, No Compromise': The Ideological Origins and Foundation of the Communist Party of New Zealand," New Zealand Journal of History, vol. 28, no. 2 (October 1994), p. 162.

- ^ a b Taylor, "'Our Motto, No Compromise,'" pp. 162–163.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bert Roth, "New Zealand," in Witold S. Sworakowski (ed.), World Communism: A Handbook, 1918–1965. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1973; p. 337.

- ^ a b Taylor, "'Our Motto, No Compromise,'" p. 168.

- ^ a b Taylor, "'Our Motto, No Compromise,'" pp. 170–171.

- ^ Kerry Taylor, "Kiwi Comrades: The Social Basis of New Zealand Communism, 1921–1948." in Kevin Morgan et al. (eds.), Agents of Revolution: New Biographical Approaches to the History of Communism. Bern: Peter Lang, 2005; p. 281.

- ^ Roth, "New Zealand," pp. 337–338.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Roth, "New Zealand," p. 338.

- ^ a b Bennett 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Taylor, "'Our Motto, No Compromise,'" p. 172.

- ^ a b c d Kerry Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period, 1928–35," in Matthew Worley (ed.), In Search of Revolution: International Communist Parties in the Third Period. London: I.B. Tauris, 2004; p. 270.

- ^ a b "Resolution on the Tasks of the Communist Party of New Zealand," RGASPI fond 495, opis 20, delo 430; quoted in Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 274.

- ^ a b Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 277.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 274.

- ^ Letter from the Political Secretariat of ECCI to CPNZ, 4 March 1930, RGASPI f. 495, op. 20 d. 430; quoted in Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 274.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 278.

- ^ a b Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 279.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 282.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," pg. 288.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," pp. 288–289.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 289.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," pp. 289–290.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 290.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 292.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 284.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," pg. 293.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," pp. 293–294.

- ^ Taylor, "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period," p. 294.

- ^ Roth, "New Zealand," pp. 338–339.

- ^ a b c Roth, "New Zealand," p. 339.

- ^ a b Norton, Clifford (1988). New Zealand Parliamentary Election Results 1946–1987: Occasional Publications No 1, Department of Political Science. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington. ISBN 0-475-11200-8.

- ^ a b c Gustafson 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Lim 2016, pp. 49–53.

- ^ Alexander 2001, p. 198.

- ^ Gustafson 2004, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Rapson, Bevan (2 November 1994). "Communists purge name". The New Zealand Herald. p. 2.

- ^ "Open Letter to Socialist Aotearoa (May 2008)". FightBack. 5 May 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Bailey, Rona". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

Further reading

- Alexander, Robert Jackson (2001). Maoism in the Developed World. Westport: Praeger. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-275-96148-0.

- Bennett, James (2004). Rats and Revolutionaries:The Labour Movement in Australia and New Zealand 1890-1940. Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Press. ISBN 1-877276-49-9.

- Brookes, R.H. (September 1965). "The CPNZ and the Sino-Soviet Split". Political Science. 17 (2): 3–25. doi:10.1177/003231876501700201.

- Gustafson, Barry (2004). "Chapter 2: New Zealand in the Cold War World". In Trapeznik, Alexander; Fox, Aaron (eds.). Lenin's Legacy Down Under: New Zealand's Cold War. University of Otago Press. pp. 17–33. ISBN 1-877276-90-1.

- Hynes, Julie M. (1979). The Communist Party in Otago, 1940-1947 (Thesis). University of Otago.

- "Sketch of Organisation Developments in New Zealand (1966-2013)" (PDF). Marxists International Archive. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Lim, Andrew (June 2016). "A Tale of Two Narratives: The New Zealand Print Media and the Indonesian-Malaysian Confrontation, 1963–1966" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies. 18 (1): 35–55. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Moloney, Pat; Taylor, Kerry, eds. (2002). On the Left: Essays on Socialism in New Zealand. Dunedin: University of Otago Press. ISBN 1877276197. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Nunes, Ray, ed. (1994). The Making of a New Zealand Revolutionary: Reminiscences of Alex Galbraith. Auckland: Workers' Party of New Zealand.

- Powell, Joseph Robert (1949). The History of a Working Class Party, 1918–40 (MA Thesis). Victoria University College.

- Powell, Ian (2004). The Communist Left and the Labour Movement in Christchurch up until the 1935 General Election (MA Thesis). University of Canterbury.

- Roth, Bert (September 1965). "The Communist Vote in New Zealand". Political Science. 17 (2): 26–35. doi:10.1177/003231876501700202.

- Smith, Ron (1994). Working Class Son: My Fight Against Capitalism and War: Memoirs of Ron Smith, a New Zealand Communist. Wellington, New Zealand: Self-published. ISBN 9780473029098.

- Smith, S.W. (1960). Rebel in a Wrong Cause. Auckland: Collins.

- Taylor, Kerry (2005). ""Kiwi Comrades: The Social Basis of New Zealand Communism, 1921–194". In Morgan, Kevin (ed.). Agents of Revolution: New Biographical Approaches to the History of Communism. Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-6891-6.

- Taylor, Kerry (2004). "The Communist Party of New Zealand and the Third Period". In Worley, Matthew (ed.). In Search of Revolution: International Communist Parties and the Third Period. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-407-7. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Taylor, Kerry (Fall 1993). "'Jack' McDonald: A Canadian Revolutionary in New Zealand". Labour/Le Travail. 32 (32): 261–268. doi:10.2307/25143734. JSTOR 25143734. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Taylor, Kerry (October 1994). "'Our Motto, No Compromise': The Ideological Origins and Foundation of the Communist Party of New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of History. 28 (2): 160–177. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Wilson, A.C. (2004). New Zealand and the Soviet Union: A Brittle Relationship. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University Press. ISBN 9780864734761. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

Archival holdings

- "Inventory of the Records of the Communist Party of New Zealand, 1924–1972." Manuscripts and Archives Collection A-9, University of Auckland Library, Auckland. —Finding aid.

- "Communist Party of New Zealand, Otago Branch: description," Collection #MS-0675. Hocken Collections, University of Otago, Dunedin.

- 1921 establishments in New Zealand

- 1994 disestablishments in New Zealand

- Comintern sections

- Communist parties in New Zealand

- Defunct communist parties

- Defunct political parties in New Zealand

- Political parties disestablished in 1994

- Political parties established in 1921

- Hoxhaist parties

- Defunct Maoist parties

- Anti-revisionist organizations