History of Australia (1788–1850)

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

The history of Australia from 1788 to 1850 covers the early British colonial period of Australia's history. This started with the arrival in 1788 of the First Fleet of British ships at Port Jackson on the lands of the Eora, and the establishment of the penal colony of New South Wales as part of the British Empire. It further covers the European scientific exploration of the continent and the establishment of the other Australian colonies that make up the modern states of Australia.

After several years of privation, the penal colony gradually expanded and developed an economy based on farming, fishing, whaling, trade with incoming ships, and construction using convict labour. By 1820, however, British settlement was largely confined to a 100 kilometre radius around Sydney and to the central plain of Van Diemen's land. From 1816 penal transportation to Australia increased rapidly and the number of free settlers grew steadily. Van Diemen's Land became a separate colony in 1825, and free settlements were established at the Swan River Colony in Western Australia (1829), the Province of South Australia (1836), and in the Port Philip District (1836). The grazing of cattle and sheep expanded inland, leading to increasing conflict with Aboriginal people on their traditional lands.

The growing population of free settlers, former convicts and Australian-born currency lads and lasses led to public demands for representative government. Penal transportation to New South Wales ended in 1840 and a semi-elected Legislative Council was established in 1842. In 1850 Britain granted Van Diemen's Land, South Australia and the newly-created colony of Victoria semi-representative Legislative Councils.

British settlement led to a decline in the Aboriginal population and the disruption of their cultures due to introduced diseases, violent conflict and dispossession of their traditional lands. Aboriginal resistance to British encroachment on their land often led to reprisals from settlers including massacres of Aboriginal people. Many Aboriginal people, however, sought an accommodation with the settlers and established viable communities, often on small areas of their traditional lands, where many aspects of their cultures were maintained.

Colonisation

The decision to establish a colony in Australia was made by Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney.[1] This was taken for two reasons: the ending of transportation of criminals to North America following the American Revolution, as well as the need for a base in the Pacific to counter French expansion.[1] Approximately 50,000 convicts are estimated to have been transported to the colonies over 150 years.[1] The First Fleet which established the first colony was an unprecedented project for the Royal Navy, as well as the first forced migration of settlers to a newly established colony.[1]

Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent scientist who had accompanied Lieutenant James Cook on his 1770 voyage, recommended Botany Bay, then known to the local Gweagal people as Kamay, as a suitable site.[2][3] Banks accepted an offer of assistance from the American Loyalist James Matra in July 1783. Matra had visited Botany Bay with Banks in 1770 as a junior officer on the Endeavour commanded by James Cook. Under Banks's guidance, he rapidly produced "A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales" (24 August 1783), with a fully developed set of reasons for a colony composed of American Loyalists, Chinese and South Sea Islanders (but not convicts).[4]

Following an interview with Secretary of State Lord Sydney in March 1784, Matra amended his proposal to include convicts as settlers.[5] Matra's plan can be seen to have “provided the original blueprint for settlement in New South Wales”.[6] A cabinet memorandum December 1784 shows the Government had Matra's plan in mind when considering the creation of a settlement in New South Wales.[6][7] The London Chronicle of 12 October 1786 said: “Mr. Matra, an Officer of the Treasury, who, sailing with Capt. Cook, had an opportunity of visiting Botany Bay, is the Gentleman who suggested the plan to Government of transporting convicts to that island”. The Government also incorporated into the colonisation plan the project for settling Norfolk Island, with its attractions of timber and flax, proposed by Banks's Royal Society colleagues, Sir John Call and Sir George Young.[8]

On 13 May 1787, the First Fleet of 11 ships and about 1,530 people (736 convicts, 17 convicts' children, 211 marines, 27 marines' wives, 14 marines' children and about 300 officers and others) under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip set sail for Botany Bay.[9][10][11] A few days after arrival at Botany Bay the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove, known by the Indigenous name Warrane, on 26 January 1788.[12] This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day. The colony was formally proclaimed by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney. Sydney Cove offered a fresh water supply and a safe harbour, which Philip famously described as:[13]

being with out exception the finest Harbour in the World [...] Here a Thousand Sail of the Line may ride in the most perfect Security.

Phillip named the settlement after the Home Secretary, Thomas Townshend, 1st Baron Sydney (Viscount Sydney from 1789). The only people at the flag raising ceremony and the formal taking of possession of the land in the name of King George III were Phillip and a few dozen marines and officers from the Supply, the rest of the ship's company and the convicts witnessing it from on board ship. The remaining ships of the Fleet were unable to leave Botany Bay until later on 26 January because of a tremendous gale.[14] The new colony was formally proclaimed as the Colony of New South Wales on 7 February.[15]

On 24 January 1788 a French expedition of two ships led by Admiral Jean-François de La Pérouse had arrived off Botany Bay, on the latest leg of a three-year voyage that had taken them from Brest, around Cape Horn, up the coast from Chile to California, north-west to Kamchatka, south-east to Easter Island, north-west to Macao, and on to the Philippines, the Friendly Isles, Hawaii and Norfolk Island.[16] Though amicably received, the French expedition was a troublesome matter for the British, as it showed the interest of France in the new land.

Nevertheless, on 2 February Lieutenant King, at Phillip's request, paid a courtesy call on the French and offered them any assistance they may need.[14] The French made the same offer to the British, as they were much better provisioned than the British and had enough supplies to last three years.[14] Neither of these offers was accepted. On 10 March[14] the French expedition, having taken on water and wood, left Botany Bay, never to be seen again. Phillip and La Pérouse never met.[citation needed] La Pérouse is remembered in a Sydney suburb of that name.[citation needed] Various other French geographical names along the Australian coast also date from this voyage.[citation needed]

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony.[citation needed] Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony.[citation needed] Phillip and several of his officers – most notably Watkin Tench – wrote journals and accounts that tell of immense hardships during the first years of settlement.[citation needed] Often Phillip's officers despaired for the future of New South Wales. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were few and far between. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney – many "professional criminals" with few of the skills required for the establishment of a colony. Many new arrivals were also sick or unfit for work and the conditions of healthy convicts only deteriorated with hard labour and poor sustenance in the settlement. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its "passengers" through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791 however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.[17]

In 1792, two French ships, La Recherche and L'Espérance anchored in a harbour near Tasmania's southernmost point they called Recherche Bay. This was at a time when Britain and France were trying to be the first European powers to discover and colonise Australia. The expedition led by Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux carried scientists and cartographers, gardeners, artists and hydrographers who, variously, planted, identified, mapped, marked, recorded and documented the environment and the people of the new lands that they encountered at the behest of the fledgling Société d'Histoire Naturelle.

White settlement began with a consignment of English convicts, guarded by a detachment of the Royal Marines, a number of whom subsequently stayed in the colony as settlers. Their view of the colony and their place in it was eloquently stated by Captain David Collins: "From the disposition to crimes and the incorrigible character of the major part of the colonists, an odium was, from the first, illiberally thrown upon the settlement; and the word "Botany Bay" became a term of reproach that was indiscriminately cast upon every one who resided in New South Wales. But let the reproach light upon those who have used it as such... if the honour of having deserved well of one's country be attainable by sacrificing good name, domestic comforts, and dearest connections in her service, the officers of this settlement have justly merited that distinction".[18]

Convicts and free settlers

This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2021) |

When the Bellona transport came to anchor in Sydney Cove on 16 January 1793, she brought with her the first immigrant free settlers. They were: Thomas Rose, a farmer from Dorset, his wife and four children; he was allowed a grant of 120 acres; Frederic Meredith, who had formerly been at Sydney with HMS Sirius; Thomas Webb (who had also been formerly at Sydney with the Sirius), his wife, and his nephew, Joseph Webb; Edward Powell, who had formerly been at Sydney with the Juliana transport, and who married a free woman after his arrival. Thomas Webb and Edward Powell each received a grant of 80 acres; and Joseph Webb and Frederic Meredith received 60 acres each.

The conditions they had come out under were that they should be provided with a free passage, be furnished with agricultural tools and implements by the Government, have two years' provisions, and have grants of land free of expense. They were likewise to have the labour of a certain number of convicts, who were also to be provided with two years' rations and one year's clothing from the public stores. The land assigned to them was some miles to the westward of Sydney, at a place named by the settlers, "Liberty Plains" on the Country of the Wangal people. It is now the area covered mainly by the suburbs of Strathfield and Homebush.

One in three convicts transported after 1798 was Irish, about a fifth of whom were transported in connection with the political and agrarian disturbances common in Ireland at the time. While the settlers were reasonably well-equipped, little consideration had been given to the skills required to make the colony self-supporting: few of the first-wave convicts had farming or trade experience (nor the soldiers), and the lack of understanding of Australia's seasonal patterns saw initial attempts at farming fail, leaving only what animals and birds the soldiers were able to shoot. The colony nearly starved, and Phillip was forced to send a ship to Batavia (Jakarta) for supplies. Some relief arrived with the Second Fleet in 1790, but life was extremely hard for the first few years of the colony.

The Second Fleet in 1790 brought to Sydney two men who were to play important roles in the colony's future. One was D'Arcy Wentworth, whose son, William Charles, went on to be an explorer, to found Australia's first newspaper and to become a leader of the movement to abolish convict transportation and establish representative government. The other was John Macarthur, a Scottish army officer and founder of the Australian wool industry, which laid the foundations of Australia's future prosperity. Macarthur was a turbulent element: in 1808 he was one of the leaders of the Rum Rebellion against the governor, William Bligh.

Convicts were usually sentenced to seven or fourteen years' penal servitude, or "for the term of their natural lives". Often these sentences had been commuted from the death sentence, which was technically the punishment for a wide variety of crimes. Upon arrival in a penal colony, convicts would be assigned to various kinds of work. Those with trades were given tasks to fit their skills (stonemasons, for example, were in very high demand) while the unskilled were assigned to work gangs to build roads and do other such tasks. Female convicts were usually assigned as domestic servants to the free settlers, many being forced into prostitution.[19]

Where possible, convicts were assigned to free settlers who would be responsible for feeding and disciplining them; in return for this, the settlers were granted land. This system reduced the workload on the central administration. Those convicts who weren't assigned to settlers were housed at barracks such as the Hyde Park Barracks or the Parramatta Female Factory.

Convict discipline was harsh; convicts who would not work or who disobeyed orders were punished by flogging, being put in stricter confinement (e.g. leg-irons), or being transported to a stricter penal colony. The penal colonies at Port Arthur in Tasmania and Moreton Bay in Queensland, for instance, were stricter than the one at Sydney, and the one at Norfolk Island was strictest of all. Convicts were assigned to work gangs to build roads, buildings, and the like. Female convicts, who made up 20% of the convict population, were usually assigned as domestic help to soldiers. Those convicts who behaved were eventually issued with ticket of leave, which allowed them a certain degree of freedom. Those who saw out their full sentences or were granted a pardon usually remained in Australia as free settlers, and were able to take on convict servants themselves.

In 1789 former convict James Ruse produced the first successful wheat harvest in NSW. He repeated this success in 1790 and, because of the pressing need for food production in the colony, was rewarded by Governor Phillip with the first land grant made in New South Wales. Ruse's 30-acre grant at Rose Hill, near Parramatta, was aptly named 'Experiment Farm'.[20] This was the colony's first successful farming enterprise, and Ruse was soon joined by others. The colony began to grow enough food to support itself, and the standard of living for the residents gradually improved. In 1804 the Castle Hill convict rebellion was led by around 200 escaped, mostly Irish convicts, although it was broken up quickly by the New South Wales Corps. On 26 January 1808, there was a military rebellion against Governor Bligh led by John Macarthur. Following this, Governor Lachlan Macquarie was given a mandate to restore government and discipline in the colony. When he arrived in 1810, he forcibly deported the NSW Corps and brought the 73rd regiment to replace them.

Growth of free settlement

This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2021) |

From about 1815 the colony, under the governorship of Lachlan Macquarie, began to grow rapidly as free settlers arrived and new lands were opened up for farming. Despite the long and arduous sea voyage, settlers were attracted by the prospect of making a new life on virtually free Crown land. From the late 1820s settlement was only authorised in the limits of location, known as the Nineteen Counties.

Many settlers occupied land without authority and beyond these authorised settlement limits: they were known as squatters and became the basis of a powerful landowning class, the Squattocracy. As a result of opposition from the labouring and artisan classes, transportation of convicts to Sydney ended in 1840, although it continued in the smaller colonies of Van Diemen's Land (first settled in 1803, later renamed Tasmania) and Moreton Bay (founded 1824, and later renamed Queensland) for a few years more.

The Swan River Settlement (as Western Australia was originally known), centred on Perth, was founded in 1829. The colony suffered from a long-term shortage of labour, and by 1850 local capitalists had succeeded in persuading London to send convicts. (Transportation did not end until 1868.) New Zealand was part of New South Wales until 1840 when it became a separate colony.

Timeline

This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2021) |

- 13 May 1787 – The 11 ships of the First Fleet leave Portsmouth under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip. Different accounts give varying numbers of passengers but the fleet consisted of at least 1,350 persons of whom 780 were convicts and 570 were free men, women and children and the number included four companies of marines. About 20% of the convicts were women and the oldest convict was 82. About 50% of the convicts had been tried in Middlesex and most of the rest were tried in the county assizes of Devon, Kent and Sussex

- 18 January 1788 – The First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay but the landing party was not impressed with the site, and moved the fleet to Port Jackson, landing in Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788 (now celebrated as Australia Day).

- 1788 – New South Wales, according to Arthur Phillip's amended Commission dated 25 April 1787, includes "all the islands adjacent in the Pacific Ocean" and running westward to the 135th meridian east. These islands included the current islands of New Zealand, which was administered as part of New South Wales.[a]

- April 1789 – an outbreak of smallpox decimates local tribes.

- 1790 – the Second Fleet of convicts arrives in Sydney Cove.

- 1791 – Third Fleet of convicts arrives

- 1793 – January: the first free settlers arrive in NSW.

- 1793 – March–April: visit of the expedition led by Alessandro Malaspina.

- 1824 – May: Founding of Brisbane

- 14 June 1825 – the colony of Van Diemen's Land is established in its own right; its name is officially changed to Tasmania on 1 January 1856. The first settlement was made at Risdon, Tasmania on 11 September 1803 when Lt. John Bowen landed with about 50 settlers, crew, soldiers and convicts. The site proved unsuitable and was abandoned in August 1804. Lt.-Col. David Collins finally established a successful settlement at nipaluna on the Country of the Muwinina people and named it Hobart in February 1804 with a party of about 260 people, including 178 convicts. (Collins had previously attempted a settlement in Victoria.) Convict ships were sent from England directly to the colony from 1812 to 1853 and over the 50 years from 1803 to 1853 around 67,000 convicts were transported to Tasmania. About 14,492 were Irish but many of them had been sentenced in English and Scottish courts. Some were also tried locally in other Australian colonies. The Indefatigable brought the first convicts direct from England on 19 October 1812 and by 1820 there were about 2,500 convicts in the colony. By the end of 1833 the number had increased to 14,900 convicts of whom 1864 were females. About 1,448 held ticket of leave, 6,573 were assigned to settlers and 275 were recorded as "absconded or missing". In 1835 there were over 800 convicts working in chain-gangs at the penal station at Port Arthur which operated from 1830 to 1877. Convicts were transferred to Van Diemen's Land from Sydney and, in later years, from 1841 to 1847, from Melbourne. Between 1826 and 1840, there were at least 19 ship loads of convicts sent from Van Diemen's Land to Norfolk Island and at other times they were sent from Norfolk Island to Van Diemen's Land.

- 1825 – New South Wales's western border is extended to 129° E.

- 21 January 1827 – Western Australia was created when a small British settlement was established at King George's Sound (Albany) by Major Edmund Lockyer in order to provide a deterrent to the French presence in the area. On 18 June 1829 the new Swan River Colony was officially proclaimed, with Captain James Stirling as the first Governor. Except for the settlement at King George's Sound, the colony was never really a part of NSW. King George's Sound was handed over in 1831. In 1849 the colony was proclaimed a British penal settlement and the first convicts arrived in 1850. Rottnest Island, previously known by the Nyungar name Wadjemup, off the coast of Perth, became the colony's convict settlement in 1838 and was used for local colonial offenders. Around 9,720 British convicts were sent directly to the colony aboard 43 ships between 1850 and 1868. The convicts were sought by local settlers because of the shortage of labour needed to develop the region. On 9 January 1868, Australia's last convict ship, the Hougoumont brought its final cargo of 269 convicts. Convicts sent to Western Australia were sentenced to terms of 6, 7, 10, 14 and 15 years and some reports suggest that their literacy rate was around 75% as opposed to 50% for those sent to NSW and Tasmania. About a third of the convicts left the Swan River Colony after serving their time.

Charles Fremantle declares Swan River Colony for Great Britain in 1829; the name was changed to Western Australia in 1832. - 1835 – the Proclamation of Governor Bourke, (10 October 1835) reinforced the doctrine that Australia had been terra nullius when settled by the British in 1788, and that the Crown had obtained beneficial ownership of all the land of New South Wales from that date. The proclamation stated that British subjects could not obtain title over vacant Crown land directly from Aboriginal Australians, effectively quashing the treaty between John Batman and the Aboriginal people of the Port Phillip area.[21][22]

- 28 December 1836 – the British province of South Australia was established. In 1842 it became a crown colony and on 22 July 1861 its area was extended westwards to its present boundary and more area was taken from New South Wales. South Australia was never a British convict colony and between 1836 and 1840 about 13,400 immigrants arrived in the area. Between 1841 and 1850, another 24,900 arrived. Some escaped convicts did settle in the area and no doubt a number of ex-convicts moved there from other colonies. On 4 January 1837 Governor Hindmarsh proclaimed that any offenders convicted in South Australia, and being under sentence of transportation, were to be transported to either New South Wales or Van Diemens Land, by the first opportunity.[23]

- 1841 – New Zealand is separated from New South Wales

- 1846 – The colony of North Australia was proclaimed by Letters Patent on 17 February, which included all of New South Wales north of 26° S. Revoked in December 1846.

European exploration

While the actual date of original exploration in Australia is unknown, there is evidence of exploration by William Dampier in 1699,[24] and the First Fleet arrived in 1788, eighteen years after Lt. James Cook surveyed and mapped the entire east coast aboard HM Bark Endeavour in 1770. In October 1795 George Bass and Matthew Flinders, accompanied by William Martin, sailed the boat Tom Thumb out of Port Jackson to Botany Bay and explored the Georges River, previously known by the Indigenous name Tucoerah, further upstream than had been done previously by the colonists. Their reports on their return led to the settlement of Banks' Town.[25] In March 1796 the same party embarked on a second voyage in a similar small boat, which they also called the Tom Thumb.[26] During this trip they travelled as far down the coast as Lake Illawarra, which they called Tom Thumb Lagoon. They came across and explored Deeban, an estuary occupied by the Tharawal and Eora peoples, and later named Port Hacking. In 1798–99, Bass and Flinders set out in a sloop and circumnavigated Van Diemen's Land, thus proving it to be an island.[27]

Aboriginal guides and assistance in the European exploration of the colony were common and often vital to the success of missions. In 1801–02 Matthew Flinders in The Investigator led the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent.[27] Previously, the famous Eora man Bennelong and a companion had become the first people born in the area of New South Wales to sail for Europe, when, in 1792 they accompanied Governor Phillip to England and were presented to King George III.[27]

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and William Wentworth succeeded in crossing west of Sydney and over the formidable barrier of forested gulleys and sheer cliffs presented by Colomatta, a mountain range on Gundungurra & Dharug Country later named the Blue Mountains, by following the ridges instead of looking for a route through the valleys. At Mount Blaxland they looked out over "enough grass to support the stock of the colony for thirty years", and expansion of the British settlement into the interior could begin.[28]

In 1820, British settlement was largely confined to a 100 kilometre radius around Sydney and to the central plain of Van Diemen's land. The settler population was 26,000 on the mainland and 6,000 in Van Diemen's Land.[29]

In 1824 the Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane, commissioned Hamilton Hume and former Royal Navy Captain William Hovell to lead an expedition to find new grazing land in the south of the colony, and also to find an answer to the mystery of where New South Wales's western rivers flowed. Over 16 weeks in 1824–25, Hume and Hovell journeyed to the bay Naarm on the land of the Kulin nation, later named Port Phillip, and back. They found many important sites including the Murray River (which they named the Hume), many of its tributaries, and good agricultural and grazing lands between Gunning, New South Wales and Corio Bay, Victoria.[30]

Charles Sturt led an expedition along the Macquarie River in 1828 and found the Darling River. A theory had developed that the inland rivers of New South Wales were draining into an inland sea. Leading a second expedition in 1829, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River into a 'broad and noble river', the Murray River, which he named after Sir George Murray, secretary of state for the colonies. His party then followed this river to its junction with the Darling River, facing two threatening encounters with local Aboriginal people along the way. Sturt continued downriver on to Lake Alexandrina, where the Murray meets the sea in South Australia. Suffering greatly, the party had to then row back upstream hundreds of kilometres for the return journey.[31]

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted a series of expeditions from the 1830s to 'fill in the gaps' left by these previous expeditions. He was meticulous in seeking to record the original Aboriginal place names around the colony, for which reason the majority of place names to this day retain their Aboriginal titles.[32]

The Polish scientist/explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps in 1839 and became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak, Tar-Gan-Gil on the Country of the Ngarigo people, and he named it Mount Kosciuszko in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko.[33]

Aboriginal resistance and accommodation

Aboriginal reactions to the arrival of British settlers were varied, but often hostile when the presence of the colonists led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of Aboriginal lands. Exotic diseases carried by the settlers decimated the Aboriginal populations, and the occupation of land and degradation of food resources sometimes led to starvation. By contrast with New Zealand, no valid treaty was signed with any of Aboriginal peoples in Australia. Flood, however, points out that unlike New Zealand, Australia's Indigenous population was divided into hundreds of tribes and language groups, which did not have "chiefs" with whom treaties could be negotiated. Moreover, Aboriginal Australians had no concept of alienating their traditional land in return for political or economic benefits.[34]

According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey, in Australia during the colonial period:

In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralisation.[35][page needed]

Henry Reynolds points out that government officials and ordinary settlers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries frequently used words such as "invasion" and "warfare" to describe their presence and relations with Aboriginal Australians.[36] Reynolds argues that armed resistance by Aboriginal people to white encroachments amounted to guerrilla warfare, beginning in the eighteenth century and continuing into the early twentieth. In the early years of colonisation, David Collins, the senior legal officer in the Sydney settlement, wrote of the local Aboriginal people:

While they entertain the idea of our having dispossessed them of their residences, they must always consider us as enemies; and upon this principle they [have] made a point of attacking the white people whenever opportunity and safety concurred.[37]

In 1847, Western Australian barrister E.W. Landor stated: "We have seized upon the country, and shot down the inhabitants, until the survivors have found it expedient to submit to our rule. We have acted as Julius Caesar did when he took possession of Britain."[38] In most cases, Reynolds argues, Aboriginal people initially resisted British presence. In a letter to the Launceston Advertiser in 1831, a settler wrote:

We are at war with them: they look upon us as enemies – as invaders – as oppressors and persecutors – they resist our invasion. They have never been subdued, therefore they are not rebellious subjects, but an injured nation, defending in their own way, their rightful possessions which have been torn from them by force.[39]

Reynolds quotes numerous writings by settlers who, in the first half of the nineteenth century, described themselves as living in fear due to attacks by Aboriginal people determined to kill them or drive them off their lands. He argues that Aboriginal resistance was, in some cases at least, temporarily effective; the killings of men, sheep and cattle, and burning of white homes and crops, drove some settlers to ruin.

Reynolds argues that continuous Aboriginal resistance for well over a century belies the myth of peaceful settlement in Australia. Settlers in turn often reacted to Aboriginal resistance with great violence, resulting in numerous massacres by whites of Aboriginal men, women and children[40] including the Pinjarra massacre, the Myall Creek massacre, and the Rufus River massacre.

Aboriginal men who resisted British colonisation in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries include Pemulwuy and Yagan. In Tasmania, the "Black War" was fought in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Accommodation and protection

In the first two years of settlement the Aboriginal people of Sydney, after initial curiosity, mostly avoided the newcomers. In November 1790, 18 months after the smallpox epidemic that had devastated the Aboriginal population, Bennelong led the survivors of several clans into Sydney.[41] Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, joined Matthew Flinders in his circumnavigation of Australia from 1801 to 1803, playing an important role as emissary to the various Indigenous peoples they encountered.[42]

In 1815, Governor Macquarie established a Native Institution to provide elementary education to Aboriginal children, settled 15 Aboriginal families on farms in Sydney and made the first freehold land grant to Aboriginal people at Black Town, west of Sydney. In 1816, he initiated an annual Native Feast at Parramatta which attracted Aboriginal people from as far as the Bathurst plains.[43] However, by the 1820s the Native Institution and Aboriginal farms had failed. Aboriginal people continued to live on vacant waterfront land and on the fringes of the Sydney settlement, adapting traditional practices to the new semi-urban environment.[44][45]

Escalating frontier conflict in the 1820s and 1830s saw colonial governments develop a number of policies aimed at protecting Aboriginal people. Protectors of Aborigines were appointed in South Australia and the Port Phillip District in 1839, and in Western Australia in 1840. While the aim was to extend the protection of British law to Aboriginal people, more often the result was an increase in their criminalisation. Protectors were also responsible for the distribution of rations, delivering elementary education to Aboriginal children, instruction in Christianity and training in occupations useful to the colonists. However, by 1857 the protection offices had been closed due to their cost and failure to meets their goals.[46][47]

Colonial governments established a small number of reserves and encouraged Christian missions which afforded some protection from frontier violence. In 1825, the NSW governor granted 10,000 acres for an Aboriginal mission at Lake Macquarie.[48] In the 1830s and early 1840s there were also missions in the Wellington Valley, Port Phillip and Moreton Bay. The settlement for Aboriginal Tasmanians on Flinders Island operated effectively as a mission under George Robinson from 1835 to 1838.[49]

In more densely settled areas, most Aboriginal people who had lost control of their land lived on reserves and missions, or on the fringes of cities and towns. In pastoral districts the British Waste Land Act of 1848 gave traditional landowners limited rights to live, hunt and gather food on Crown land under pastoral leases. Many Aboriginal groups camped on pastoral stations where Aboriginal men were often employed as shepherds and stockmen. These groups were able to retain a connection with their lands and maintain aspects of their traditional culture.[50]

Politics and government

Traditional Aboriginal society had been governed by councils of elders and a collective decision-making process, but the first European-style governments established after 1788 were autocratic and run by appointed governors—although English law was transplanted into the Australian colonies by virtue of the doctrine of reception, thus notions of the rights and processes established by the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689 were brought from Britain by the colonists. Agitation for representative government began soon after the settlement of the colonies.[51][52]

From 1788 until the 1850s, the governance of the colonies, including most policy decision-making, was largely in the hands of the governors, who were directly responsible to the government in London (Home Office until 1794; War Office until 1801; and War and Colonial Office until 1854).[1] The first governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip, was given executive and legislative powers to establish courts, military forces, fight enemies, give out land grants, and regulate the economy.[1][52]

The early colonists adopted the British political culture of the time, which allowed the use of public office for furthering private interests, which led to officers of the New South Wales Corps, which had replaced the original marines in 1791, trying to use their position in order to create monopolies on trade.[1] Such private enterprise was encouraged by the second governor Francis Grose, who had replaced Phillip in 1792, and he started giving out land and convict labourers to the officers.[1] The Corps established a monopoly on the rum trade, and became very powerful within the small colony.[1] After Governor William Bligh tried to break the military monopoly and questioned some of their leases, officers led by George Johnston launched a coup d'état in the Rum Rebellion.[1][52] After a year, he agreed to leave his position, and returned to Britain alongside Johnston, who was found guilty by a court-martial.[1][52] In response to the events, the British government dispanded the Corps, and replaced them with the 73rd Regiment, which led to 'deprivatising' of the officials of the colony.[53] Many of the officers retired, and were later known as the 'faction of 1808' and as an influential and conservative element in the politics of the colony.[1]

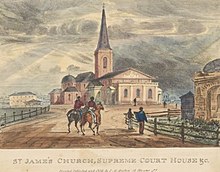

The New South Wales Act 1823 by the Parliament of the United Kingdom established the first legislative body in Australia, the New South Wales Legislative Council, as an appointed body of five to seven members to advise the Governor of New South Wales.[54] However, the new body had limited powers of oversight.[54] The act also established the Supreme Court of New South Wales, which had power over the executive.[55] Before a Governor could propose a law before the council, the Chief Justice had to certify that it was not against English law, creating a form of judicial review.[56] However, there was no separation of powers, with Chief Justice Francis Forbes also serving in the Legislative Council as well as the Governor's Executive Council.[57] The Executive Council had been founded in 1825, and was composed of leading officials in the colony.[58]

The Australian began publishing in 1824, as did The Monitor in 1826, and The Sydney Morning Herald in 1831. Ralph Darling tried to control the press first by proposing to license newspapers and impose a stamp duty on them, and after this was refused by Forbes, by prosecuting their owners for seditious libel.[59]

Van Diemen's Land was established in 1825, but remained under the jurisdiction of the New South Wales Governor, being represented there by a lieutenant-governor.[60] Western Australia was declared to the British Empire by James Stirling, and the Swan River Colony was established there in 1829, with Stirling made governor in 1831.[1] The South Australian Company was established in 1834 as a private venture to establish a new colony in the south coast, being motivated by the social reformist ideas of Jeremy Bentham.[61]

Political divisions

The liberal/conservative divide of British politics was replicated in Australia.[62] This division was also affected by that between 'emancipists' (former convicts) and 'exclusivists' (land-owning free settlers).[63] The conservatives generally saw representative government as a threat, since they were worried about former convicts voting against their masters.[64] The leader of the conservatives was John Macarthur, a wool producer and a leader of the Rum Rebellion.[65] The conservatives believed themselves to be leading and protecting the economic development of the colony.[66]

William Wentworth established the Australian Patriotic Association (Australia's first political party) in 1835 to demand democratic government for New South Wales. He had petitioned the British government for self-determination in 1827.[1] The reformist attorney general, John Plunkett, sought to apply Enlightenment principles to governance in the colony, pursuing the establishment of equality before the law, first by extending jury rights to emancipists, then by extending legal protections to convicts, assigned servants and Aboriginal peoples. Plunkett twice charged the colonist perpetrators of the Myall Creek massacre of Aboriginal people with murder, resulting in a conviction and his landmark Church Act of 1836 disestablished the Church of England and established legal equality between Anglicans, Catholics, Presbyterians and later Methodists.[67]

Representative government

In 1840, the Adelaide City Council and the Sydney City Council were established. Men who possessed 1,000 pounds' worth of property were able to stand for election and wealthy landowners were permitted up to four votes each in elections. Australia's first parliamentary elections were conducted for the New South Wales Legislative Council in 1843, again with voting rights (for males only) tied to property ownership or financial capacity. Voter rights were extended further in New South Wales in 1850 and elections for legislative councils were held in the colonies of Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania.[68]

By the mid-19th century, there was a strong desire for representative and responsible government in the colonies of Australia, later fed by the democratic spirit of the goldfields and the ideas of the great reform movements sweeping Europe, the United States and the British Empire. The end of convict transportation accelerated reform in the 1840s and 1850s. The Australian Colonies Government Act 1850 was a landmark development which granted representative constitutions to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania, implementing a Privy Council committee recommendation to establish in each of the colonies "a Governor, a Council, and an Assembly".[69] The colonies enthusiastically set about writing constitutions, which produced democratically progressive parliaments—although the constitutions generally maintained the role of the colonial upper houses as representative of social and economic "interests" and all established constitutional monarchies with the British monarch as the symbolic head of state.[70]

Economy and trade

The instructions provided to the first five governors of New South Wales show that the initial plans for the colony were limited.[71] The settlement was to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on subsistence agriculture. Trade, shipping and ship building were banned in order to keep the convicts isolated and so as not to interfere with the trade monopoly of the British East India Company. There was no plan for economic development apart from investigating the possibility of producing raw materials for Britain.[72]

After the departure of Phillip, the colony's military officers began acquiring land and importing consumer goods obtained from visiting ships. Former convicts also farmed land granted to them and engaged in trade. Farms spread to the more fertile lands surrounding Paramatta, Windsor and Camden, and by 1803 the colony was self-sufficient in grain. Boat building developed in order to make travel easier and exploit the marine resources of the coastal settlements. Sealing and whaling became important industries.[73]

Because of its nature as a forced settlement, the early colony's economy was heavily dependent on the state.[1] For example, some of the earliest agricultural production was directly run by the government. The Commissariat also played a major role in the economy.[74] In 1800, 72% of the population relied on government rations, but this was reduced to 32% by 1806.[1] While some convicts were assigned to settlers as labourers, they were usually free to find part-time work for supplemental income, and were allowed to own property (in contravention to British law at the time).[1] Some convicts had their skills taken to use by the colonial government, as with for example the architect Francis Greenway, who designed many early public buildings. Approximately 10–15% of the convicts worked on public projects building infrastructure, while most of the rest were assigned to private employers.[75] Land grants were abandoned in 1831 in favour of selling crown lands, which covered all land deemed "unsettled".[76][77]

The colonies relied heavily on imports from England for survival. The official currency of the colonies was the British pound, but the unofficial currency and most readily accepted trade good was rum. The early economy relied on barter for exchange, an issue which Lachlan Macquarie (Governor from 1810 to 1821) tried to fix first by introducing Spanish dollars, and then by establishing the Bank of New South Wales with the authority to issue financial instruments.[78] Barter continued, however, until shipments of sterling in the late 1820s enabled a move to a monetary economy.[79]

Macquarie also played a leading role in the economic development of New South Wales by employing a planner to design the street layout of Sydney and commissioning the construction of roads, wharves, churches, and public buildings. He sent explorers out from Sydney and, in 1815, a road across the Blue Mountains was completed, opening the way for large scale farming and grazing in the lightly-wooded pastures west of the Great Dividing Range.[80][81]

The colonists spent a large part of the early nineteenth century building infrastructure such as railways, bridges and schools, which allowed them to get on with economic development.[82] During this period Australian businesspeople began to prosper. For example, the partnership of Berry and Wollstonecraft made enormous profits by means of land grants, convict labour, and exporting native cedar back to England. John Macarthur, after retiring from the New South Wales Corps, went on to start the wool industry in Australia.[1]

From the 1820s squatters increasingly established unauthorised cattle and sheep runs beyond the official limits of the settled colony. In 1836, a system of annual licences authorising grazing on Crown Land was introduced in an attempt to control the pastoral industry, but booming wool prices and the high cost of land in the settled areas encouraged further squatting. By 1844 wool accounted for half of the colony's exports and by 1850 most of the eastern third of New South Wales was controlled by fewer than 2,000 pastoralists.[83][84]

Religion, education, and culture

Religion

Since time immemorial in Australia, its indigenous people had performed the rites and rituals of the totemic belief system of The Dreaming.[85] The permanent presence of Christianity in Australia however, came with the arrival of the First Fleet of British convict ships at Sydney in 1788. As a British colony, the predominant Christian denomination was the Church of England, but one tenth of all the convicts who came to Australia on the First Fleet were Catholic, and at least half of them were born in Ireland.

A small proportion of British marines were also Catholic. Some of the Irish convicts had been transported to Australia for political crimes or social rebellion in Ireland, so the authorities were suspicious of the minority religion for the first three decades of settlement.[86] It was therefore the crew of the French explorer La Pérouse who conducted the first Catholic ceremony on Australian soil in 1788—the burial of Father Louis Receveur, a Franciscan friar, who died while the ships were at anchor at Botany Bay, while on a mission to explore the Pacific.[87]

In early colonial times, Church of England clergy worked closely with the governors. Richard Johnson, Anglican chaplain to the First Fleet, was charged by the governor, Arthur Phillip, with improving "public morality" in the colony, but he was also heavily involved in health and education.[88] The Reverend Samuel Marsden (1765–1838) had magisterial duties, and so was equated with the authorities by the convicts. He became known as the "flogging parson" for the severity of his punishments.[89]

Catholic convicts were compelled to attend Church of England services and their children and orphans were raised by the authorities as Protestant.[90] The first Catholic priest colonists arrived in Australia as convicts in 1800—James Harold, James Dixon, and Peter O'Neill, who had been convicted for "complicity" in the Irish 1798 Rebellion. Dixon was conditionally emancipated and permitted to celebrate Mass. On 15 May 1803, in vestments made from curtains and with a chalice made of tin, he conducted the first Catholic Mass in New South Wales.[90]

The Irish-led Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 alarmed the British authorities and Dixon's permission to celebrate Mass was revoked. Jeremiah Flynn, an Irish Cistercian, was appointed as Prefect Apostolic of New Holland, and set out from Britain for the colony, uninvited. Watched by authorities, Flynn secretly performed priestly duties before being arrested and deported to London. Reaction to the affair in Britain led to two further priests being allowed to travel to the colony in 1820: John Joseph Therry and Philip Connolly.[86] The foundation stone for the first St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney was laid on 29 October 1821 by Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

The absence of a Catholic mission in Australia before 1818 reflected the legal disabilities of Catholics in Britain and the difficult position of Ireland within the British Empire. The government therefore endorsed the English Benedictines to lead the early Church in the colony.[91] The Church of England lost its legal privileges in the Colony of New South Wales by the Church Act of 1836. Drafted by the reformist attorney-general John Plunkett, the Act established legal equality for Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians and was later extended to Methodists.[67] Catholic missionary William Ullathorne criticised the convict system, publishing a pamphlet, The horrors of transportation briefly unfolded to the people, in Britain in 1837.[92] Laywoman Caroline Chisolm did ecumenical work to alleviate the suffering of female migrants.[citation needed]

Sydney's first Catholic Bishop, John Bede Polding requested a community of nuns be sent to the colony and five Irish Sisters of Charity arrived in 1838 to set about pastoral care of convict women and work in schools and hospitals before going on to found their own schools and hospitals.[93] At Polding's request, the Christian Brothers arrived in Sydney in 1843 to assist in schools. Establishing themselves first at Sevenhill, in South Australia in 1848, the Jesuits were the first religious order of priests to enter and establish houses in South Australia, Victoria, Queensland and the Northern Territory, where they established schools and missions.[citation needed]

Education

Initially, education was informal, primarily occurring in the home.[citation needed] However, the administration of the colony, led by Governor Richard Bourke, had adopted the British liberal creed that education was critical for popular participation in politics.[94] Francis Forbes had founded Sydney College in 1830.[95] At the instigation of the then British Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, and with the patronage of King William IV, Australia's oldest surviving independent school, The King's School, Parramatta, was founded in 1831 as part of an effort to establish grammar schools in the colony.[96] By 1833, there were about ten Catholic schools in the Australian colonies.[86]

Medicine

More than a hundred men who practised medicine are known to have been transported to Australia as convicts in the 80 years between 1788 and 1868. Medical qualifications were not standardised at the time, and many would have been unqualified. Many were not criminals in the true sense, but had been transported to New South Wales as a result of youthful, impetuous statements or actions in the wrong quarters. Three practitioners were recognised for their medical abilities and as founders of several institutions that developed as the settlement evolved from a gaol to a colony. D'Arcy Wentworth was a medical student in London who lived beyond his means and after being acquitted of highway robbery was advised to leave Great Britain and serve as assistant surgeon on a convict ship. He arrived in Sydney in 1790. In 1809 he was appointed Principal Surgeon of the colony. An entrepreneur, he acquired much wealth, including as one of the contractors of the notorious Rum Hospital and as a founder of the Bank of New South Wales. William Redfern had taken part in a mutiny and been sentenced to death, but instead was transported in 1801. To prove his surgical skills, which impressed the Governor, he was examined before three doctors and so became Australia's first medical graduate. He laid the foundations of the colony's public health and has been called the "father of Australian medicine". William Bland joined the Royal Navy as a surgeon's mate in 1809. An impetuous man, he threw a glass of water over the ship's purser and reluctantly participated in a pistol duel with the man, whom he killed. He was sentenced to seven years' transportation, arriving in 1814; he was pardoned a year later. In 1818, however, he was sentenced to 12 months' imprisonment after writing insulting satires criticising Governor Macquarie. He was a democrat, favouring radical democracy and land reform, and worked in support of the poor throughout his subsequent political career.[97][98]

Culture

Australian composers who published musical works in this period include Francis Hartwell Henslowe, Frederick Ellard, Charles Edward Horsley, Isaac Nathan, Stephen Hale Marsh (1805–1888), and Henry Marsh (1824–1885). Some[which?] Australian folksongs date to this period. [citation needed]

Among the first true works of Australian literature produced over this period was the accounts of the settlement of Sydney by Watkin Tench, captain-lieutenant of the marines on the First Fleet to arrive in 1788. In 1819, poet, explorer, journalist and politician William Wentworth published the first book written by an Australian: A Statistical, Historical, and Political Description of the Colony of New South Wales and Its Dependent Settlements in Van Diemen's Land, With a Particular Enumeration of the Advantages Which These Colonies Offer for Emigration and Their Superiority in Many Respects Over Those Possessed by the United States,[99] in which he advocated an elected assembly for New South Wales, trial by jury and settlement of Australia by free emigrants rather than convicts. In 1838 The Guardian: a tale by Anna Maria Bunn was published in Sydney. It was the first Australian novel printed and published in mainland Australia and the first Australian novel written by a woman. It is a Gothic ce.[100]

European traditions of Australian theatre also came with the First Fleet, with the first production being performed in 1789 by convicts: The Recruiting Officer by George Farquhar.[101] The Theatre Royal, Hobart, opened in 1837 and it remains the oldest theatre in Australia.[102] The Melbourne Athenaeum is one of the oldest public institutions in Australia, founded in 1839 and it served as library, school of arts and dance hall (and later became Australia's first cinema, screening The Story of the Kelly Gang, the world's first feature film in 1906).[103] The Queen's Theatre, Adelaide opened with Shakespeare in 1841 and is today the oldest theatre on the mainland.[104]

Representations in literature and film

- Marcus Clarke's 1874 novel, For the Term of his Natural Life, and the 1983 television adaptation of the novel.

- Eleanor Dark's 1947 Timeless Land trilogy, which spans the colonisation from 1788 to 1811. The 1980s television drama, The Timeless Land, was based on this trilogy.

See also

- British colonisation of South Australia

- British colonisation of Tasmania

- European Australian

- Europeans in Oceania

- Historical Records of Australia

- History of Australia

- History of Australia (1851–1900)

- History of New South Wales

- History of Queensland

- History of South Australia

- History of Tasmania

- History of Western Australia

- Journals of the First Fleet

Notes

- ^ For example the UK Act New South Wales Judicature Act 1823 made specific provision for administration of justice of New Zealand by the New South Wales Courts; stating "And be it further enacted that the said supreme courts in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land respectively shall and may inquire of hear and determine all treasons piracies felonies robberies murders conspiracies and other offences of what nature or kind soever committed or that shall be committed upon the sea or in any haven river creek or place where the admiral or admirals have power authority or jurisdiction or committed or that shall be committed in the islands of New Zealand".

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Kemp (2018).

- ^ Gascoigne, John (1998). Science in the service of empire : Joseph Banks, the British state and the uses of science in the age of revolution. Cambridge, UK. p. 187. ISBN 0-521-55069-6. OCLC 39524807. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "National Museum of Australia – Kamay – Botany Bay". www.nma.gov.au. 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Carter, Harold B. (1988). "Banks, Cook and the Century Natural History Tradition". In Delamothe, Tony; Bridge, Carl (eds.). Interpreting Australia: British Perceptions of Australia since 1788. London: Sir Robert Menzies Centre for Australian Studies. pp. 4–23. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Matra to Fox, 2 April 1784. British Library, Add. Ms 47568.

- ^ a b Atkinson, Alan (1 April 1990). "The first plans for governing New South Wales, 1786–87". Australian Historical Studies. 24 (94): 22–40. doi:10.1080/10314619008595830. ISSN 1031-461X. S2CID 143682560.

- ^ ‘Memo. of matters to be brought before Cabinet’, State Library of New South Wales, Dixon 12Library Add. MS Q522

- ^ King, Robert J. (2003). "Norfolk Island: Phantasy and Reality, 1770–1814". The Great Circle. 25 (2): 20–41. ISSN 0156-8698. JSTOR 41563142.

- ^ Frost, Alan (2012). The First Fleet : the real story (2nd ed.). Collingwood, Victoria: Black Inc. ISBN 978-1-86395-561-4. OCLC 758973269. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Horne, Donald (1972). The Australian People: Biography of a Nation. Sydney, NSW: Angus and Robertson. ISBN 978-0-207-12496-9.

- ^ Miles, Rosalind (18 December 2007). Who Cooked the Last Supper?: The Women's History of the World. Crown. ISBN 978-0-307-42267-5. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Peter Hill (2008) p.141-150 [full citation needed]

- ^ Phillip, Arthur. "digitised letter". 19: Letter from Arthur Phillip to the Marquis of Lansdowne, 3 July 1788, ID: SAFE/MLMSS 7241 (Safe 1/234). State Library of NSW.

- ^ a b c d Hill, David (2009). 1788 : the brutal truth of the First Fleet : the biggest single overseas migration the world has ever seen. North Sydney, NSW: Random House Australia. ISBN 978-1-74166-800-1. OCLC 313723118. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ King, Robert J. (1981). "The Territorial Boundaries of New South Wales in 1788". The Great Circle. 3 (2): 70–89. ISSN 0156-8698. JSTOR 41562651.

- ^ King, Robert J. (1 December 1999). "What brought Laperouse to Botany Bay?". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 85 (2): 140. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Fletcher, B H (1967). "Phillip, Arthur (1738–1814)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Collins, David (1798). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales (PDF). Vol. 1 (University of Sydney Reprint ed.). London: T. Caddel Hun and W. Davies. p. 502. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Anne Summers (1975). Damned Whores and God's Police. Ringwood, Victoria. pp. 270–274. ISBN 978-0-14-021832-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "First Farms". Discover Collections. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ Banner, Stuart (2005). "Why Terra Nullius? Anthropology and Property Law in Early Australia". Law and History Review. 23 (1): 95–131. doi:10.1017/S0738248000000067. JSTOR 30042845. S2CID 145484253.

- ^ Thompson, Stephen (2011). "Governor Bourke's 1835 Proclamation of Terra Nullius". Migration Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Proclamation". South Australian Gazette And Colonial Register. South Australia. 3 June 1837. p. 1. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Williams, Glyndwr (1 January 1988). "The English and Aborigines First Contacts". History Today. 38 (1): 33–39. ProQuest 1299026999. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Scott, Ernest (1914). The Life of Captain Matthew Flinders, RN. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. p. 86. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ Flinders, Matthew (1796). Narrative of expeditions along the coast of New South Wales, for the further discovery of its harbours from the year 1795 to 1799. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Bowden, Keith Macrae (1966). "Bass, George (1771–1803)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 1. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Conway, Jill (1966). "Blaxland, Gregory (1778–1853)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 1. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Macintrye (2020). pp. 55, 60, 77

- ^ Hume, Stuart H. (1966). "Hume, Hamilton (1797–1873)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 1. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Gibbney, H J (1967). "Sturt, Charles (1795–1869)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Baker, D W A (1967). "Mitchell, Sir Thomas Livingstone (1792–1855)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Heney, Helen (1967). "Strzelecki, Sir Paul Edmund de (1797–1873)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Flood, Josephine (2019). The Original Australians (2nd ed.). Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin. pp. 22–23, 111–13. ISBN 9781760527075.

- ^ Blainey, Geoffrey (2004). A very short history of the world. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-04202-1. OCLC 223607384. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Reynolds, Henry (1981). The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal resistance to the European invasion of Australia. ISBN 0-86840-892-1.

- ^ Reynolds (1999), p. 165.

- ^ Reynolds (1999), p. 163.

- ^ Reynolds (1999), p. 148.

- ^ Reynolds (1999), Chapter 9: "The Killing Times", pp. 117–133.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). "The early colonial presence, 1788–1822". In The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1. pp. 106, 117–19

- ^ Broome, Richard. (2019). p. 33

- ^ Flood, Josephine (2019). pp. 69–70

- ^ Banivanua Mar, Tracey; Edmonds, Penelope (2013). "Indigenous and settler relations". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I. p. 344-45

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). "The early colonial presence, 1788–1822". In The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1. pp. 117–19

- ^ Broome, Richard (2019). pp. 52–53

- ^ Nettelbeck, Amanda (2012). "'A Halo of Protection': Colonial Protectors and the Principle of Aboriginal Protection through Punishment". Australian Historical Studies. 43 (3): 396–411. doi:10.1080/1031461X.2012.706621. S2CID 143060019.

- ^ Banivanua Mar, Tracey; Edmonds, Penelope (2013). "Indigenous and settler relations". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I. p. 345

- ^ Broome, Richard (2019). pp. 31–32,72

- ^ Banivanua Mar, Tracey; Edmonds, Penelope (2013). "Indigenous and settler relations". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I. p. 355-58, 358–60

- ^ "Democracy timeline". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Milestones in Australian democracy". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Butlin, Noel George. (2010). Forming a Colonial Economy : Australia, 1810–1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-511-55232-8. OCLC 958549195.

- ^ a b Kemp (2018) The New South Wales Act 1823 had broadened participation in the government of the colony when it established an appointed Legislative Council of five to seven members to put the rules and regulations of the colony on a secure legal basis, and provided for a professional administration. Only the Governor, however, could initiate legislation. The authority of the appointed legislature fell well short of the colonists’ aspirations. It had no power over colonial lands, and none over the transportation system nor the treatment of convicts. The magistrates’ powers were defined. The Act was to operate until 1 July 1827 when the arrangements in it would be reviewed. The system, in fact, remained in operation until 1832.

- ^ Kemp (2018) In addition to the nominated Legislative Council, a highly significant innovation in the Act for the government of New South Wales was the establishment of a Supreme Court with the powers of the King’s Bench court in London, which included the power to issue writs to control inferior courts and officials. This gave the court the capacity to control the executive

- ^ Kemp (2018) One of his most important powers, however, was the requirement that, before the Governor put a proposed law before the Council, the Chief Justice should issue a certificate that it was not repugnant to the laws of England, a power that was to prove a significant restraint on, and source of frustration for, Brisbane’s successor, Sir Ralph Darling.

- ^ Kemp (2018) Despite the reforms the colonial ‘constitution’ lacked one of the main principles that was said to underpin the British constitution: the separation of powers. Forbes was not only Chief Justice. He was also a member of the Legislative Council and of the Governor’s Executive Council.

- ^ Kemp (2018) In 1825 its membership was expanded, as permitted under the Act, to seven, including non-official members. John Macarthur became a member, and in the same year the Governor’s instructions were amended to create an executive council consisting of the leading officials of the colony.

- ^ Kemp (2018) When he proposed bills to the Legislative Council to control the press by licensing newspapers and imposing a stamp duty, Chief Justice Forbes refused to certify them as ‘not repugnant to the laws of England’. Darling then adopted an alternative course of action to bring Wentworth and Wardell to heel, prosecuting them in 1828 for seditious libel.

- ^ Kemp (2018) One outcome of Bigge’s reports was the declaration of Van Diemen’s Land as a separate colony. This was formally undertaken by Sir Ralph Darling when he arrived in Australia as Governor to succeed Brisbane in 1825. Darling was to remain Governor of both settlements, being represented in Van Diemen’s Land by a lieutenant-governor.

- ^ Kemp (2018) The South Australian Association, formed by a number of the parliamentary philosophical radicals, secured a South Australian Act in 1834, which divided authority between the Colonial Office and a Board of Colonization Commissioners. The new colony was to be the purest experiment in the world in giving full expression to the ideas of the Benthamites.

- ^ Kemp (2018) The directions of reform and the case for defending conservative interests were influenced by the dominant ideas associated with the Whig, Tory and liberal positions in England.

- ^ Kemp (2018) The politics of New South Wales under Bourke cannot be understood simply as a battle for power between ‘emancipists’ and ‘exclusives’. This was only one of the colony’s lines of political cleavage. Many supporting the claims of emancipists were free emigrants, and the formulation by the emigrants of their claims expressed liberal ideas that had much wider currency than in New South Wales alone.

- ^ Kemp (2018) There was, however, another fear that lay behind the concerns of the conservatives that had more realism to it, and that also boded ill for the convict system: the freed convicts who might acquire the franchise mightexercise their rights, at best, to seek to regulate and control their former masters or, at worst, to wreak revenge upon them.

- ^ Kemp (2018) Macarthur’s remarks expressed his profound political and social conservatism. He was a cultured and civilised leader of the colony’s wealthy conservative elite

- ^ Kemp (2018) Macarthur’s group also saw — accurately — that many of these now ‘free’ citizens had little education, and could make little contribution to government. Not understanding how prosperity was achieved, if politically empowered they might even act in ways that were counter to their own real interests. If they gained political power, the whole economic progress of the colony would be imperilled by foolish and ill-considered schemes. Economic development must come before democracy, in the interests of all. In pursuit of this delaying strategy, the political rhetoric of the conservatives exaggerated the risks and dangers, and highlighted the need for strong action against crime and lawbreakers.

- ^ a b Suttor, T. L. (1967). "Plunkett, John Hubert (1802–1869)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "Australia's major electoral developments Timeline: 1788 – 1899". Australian Electoral Commission. 28 January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Jeffery, Judith (8 April 2014). "Australian Colonies Government Act". SA History Hub. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "The Right to Vote in Australia". Australian Electoral Commission. 28 January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Macintyre, Stuart (2020). A Concise History of Australia (Fifth ed.). Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. pp. 34, 41. ISBN 9781108728485.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). "The early colonial presence, 1788-1822". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I, Indigenous and colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 9781107011533.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). "The early colonial presence, 1788-1822". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I, Indigenous and colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–114. ISBN 9781107011533.

- ^ Kemp (2018) The Government Commissariat (established to support the convict system and the military establishment) continued to be a significant participant in the market, affecting prices and the pattern of production.

- ^ Kemp (2018) Between 10 and 15 per cent of the convicts were engaged in the building of public infrastructure such as roads, bridges, buildings and so on. Most of the remainder were allocated under the assignment system to private employers.

- ^ Kemp (2018) Bourke found the colony’s development had reached a stage where land grants could be abandoned and Crown land alienated only by sale. Land grants were abandoned in 1831.

- ^ Kemp (2018) A feature of imperial land settlement policy was the declaration by the Crown that it retained title to all unsettled lands.

- ^ Kemp (2018) Macquarie could see that the absence of a proper money supply and a recognised currency was a significant inhibitor of enterprise. He made an attempt to equip the colony with a money economy to facilitate economic exchange, using Spanish dollars, and while this was an improvement, it was still an unsatisfactory solution that raised continual questions about the value of the currency. It also suffered from a tendency for the currency to leak abroad. 24 In 1817 Macquarie chartered (illegally) a bank – the Bank of New South Wales (now Westpac) – with purported limited liability and the authority to issue financial instruments.

- ^ Kemp (2018) Australia began to acquire a satisfactory means of exchange to replace barter when, in the later 1820s, substantial shipments of sterling were at last made to the colony. Despite some interference from the Commissariat, which sought to encourage Spanish dollars, by the 1830s the Australian colonies were established on sterling currency

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). A History of New South Wales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–19. ISBN 9780521833844.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). pp. 115-17

- ^ Melleuish, Greg (Autumn 2007). "The History of Liberty in Australia" (PDF). Policy. 23 (1). The Centre for Independent Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Ford, Lisa; Roberts, David Andrew (2013). "Expansion, 1820–1850". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I. pp. 128–135.

- ^ W.P. Driscoll and E.S. Elphick (1982) Birth of A Nation p. 147-48. Rigby, Australia. ISBN 0-85179-697-4

- ^ Ingold, Tim (2000). "Totemism, animism, and the depiction of animals". The perception of the environment: essays on livelihood,dwelling, and skill. London: Routledge. pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b c Dixon, R (2005). "The Catholic Community in Australia". Catholic Australia. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Botany Bay Story". Saint Anne's Catholic Home Schooling Group. Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Cable, K J (1967). "Johnson, Richard (1753–1827)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Yarwood, A T (1967). "Marsden, Samuel (1765–1838)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ a b Cleary, Henry (1907). "Australia". In Knight, Kevin (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Nairn, Bede (1967). "Polding, John Bede (1794–1877)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Suttor, T L (1967). "Ullathorne, William Bernard (1806–1889)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "History & Tradition". St Vincent's Hospital. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Kemp (2018) The British liberals had long recognised that the education of the people was the essential condition for the worthwhile participation of the masses in politics. The colonial liberals, led by Bourke, took the same view.

- ^ Kemp (2018) Francis Forbes had laid the foundation stone for Sydney College (later Sydney Grammar) in 1830, and on its completion chaired its council.

- ^ "Brief history of The King's School". The King's School. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Hull, Gillian (1 July 2001). "From Convicts to Founding Fathers—Three notable Sydney Doctors". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 94 (7): 358–361. doi:10.1177/014107680109400715. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 1281607. PMID 11418713. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Dr William Bland (1789–1868)". Former members of the Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Reece, R H W (2019). "Yagan (1795–1833)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Turcotte, Gerry (1998). "Australian Gothic" (PDF, 12 pages). Faculty of Arts—Papers. University of Wollongong. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- ^ "The plays". The Recruiting Officer & Our Country's Good. November 2000. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Hobart's Theatre Royal – a dream of a theatre..." Theatre Royal. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011.

- ^ "History of the Melbourne Athenaeum". Melbourn Athenaeum. 2009. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011.

- ^ "Queen's Theatre – About the Theatre". History Trust of South Australia. 2010. Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

Bibliography

- Reynolds, Henry (1999). Why Weren't We Told?. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-027842-2.

- Kemp, David (2018). The Land of Dreams: How Australians Won Their Freedom, 1788-1860. Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-87334-4. OCLC 1088319758. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

Further reading

- Clark, C. M. H. (1955), Select Documents in Australian History 1788–1850 (Angus and Robertson). Available at the Internet Archive.[1]