Politics of Ukraine

Politics of Ukraine Державний лад України Derzhavnyy lad Ukrainy | |

|---|---|

Coat of Arms of Ukraine | |

| Polity type | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

| Constitution | Constitution of Ukraine |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | Verkhovna Rada |

| Type | Unicameral |

| Meeting place | Verkhovna Rada Building, Kyiv |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of state | |

| Title | President |

| Currently | Volodymyr Zelensky |

| Appointer | Direct popular vote |

| Head of government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Denys Shmygal |

| Appointer | President |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Government of Ukraine |

| Leader | Prime Minister |

| Appointer | President |

| Headquarters | Cabinet of Ministries |

| Ministries | 19 |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | Judiciary of Ukraine |

| Constitutional Court | |

| Chief judge | Nataliya Shaptala |

| Seat | 14 Zhylianska St., Kyiv |

| Supreme Court | |

| Chief judge | Yaroslav Romanyuk |

|

|---|

|

|

The politics of Ukraine take place in a framework of a semi-presidential representative democratic republic and of a multi-party system. A Cabinet of Ministers exercises executive power (until 1996, jointly with the President). Legislative power is vested in the parliament (Verkhovna Rada - Template:Lang-uk). Taras Kuzio described Ukraine's political system in 2009 as "weak, fractured, highly personal and ideologically vacuous while the judiciary and media fail to hold politicians to account".[1][2][3][need quotation to verify] Kuzio has categorised the Ukrainian state as "over-centralised" - both as a legacy of the Soviet system and caused by a fear of separatism.[4][5] Corruption in Ukraine is rampant, and widely cited - at home and abroad - as a defining characteristic (and decisive handicap) of Ukrainian society, politics and government.[6][7][8][9]

During Soviet rule of the territory of present-day Ukraine (c. 1917-1991), the political system featured a single-party socialist-republic framework characterized by the superior role of the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU), the sole-governing party then permitted by the constitution.

From 2014 changes in the administration on-the-ground in Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk have complicated the de facto political situation associated with those areas.

In 2018 the Economist Intelligence Unit rated Ukraine a "hybrid regime".[10](registration required)[needs update]

Constitution and fundamental freedoms

Shortly after becoming independent in 1991, Ukraine named a parliamentary commission to prepare a new constitution, adopted a multi-party system, and adopted legislative guarantees of civil and political rights for national minorities. A new, democratic constitution was adopted on 28 June 1996, which mandates a pluralistic political system with protection of basic human rights and liberties, and a semi-presidential form of government.

The Constitution was amended in December 2004[11] to ease the resolution of the 2004 presidential election crisis. The consociationalist agreement transformed the form of government in a semi-presidentialism in which the President of Ukraine had to cohabit with a powerful Prime Minister. The Constitutional Amendments took force between January and May 2006.

The Constitutional Court of Ukraine in October 2010 overturned the 2004 amendments, considering them unconstitutional.[12] The present valid Constitution of Ukraine is therefore the 1996 text. On November 18, 2010 The Venice Commission published its report titled The Opinion of the Constitutional Situation in Ukraine in Review of the Judgement of Ukraine's Constitutional Court, in which it stated "It also considers highly unusual that far-reaching constitutional amendments, including the change of the political system of the country - from a parliamentary system to a parliamentary presidential one - are declared unconstitutional by a decision of the Constitutional Court after a period of 6 years. ... As Constitutional Courts are bound by the Constitution and do not stand above it, such decisions raise important questions of democratic legitimacy and the rule of law".[13]

On February 21, 2014 the parliament passed a law that reinstated the December 8, 2004 amendments of the constitution.[14] This was passed under simplified procedure without any decision of the relevant committee and was passed in the first and the second reading in one voting by 386 deputies.[14] The law was approved by 140 MPs of the Party of Regions, 89 MPs of Batkivshchyna, 40 MPs of UDAR, 32 of the Communist Party, and 50 independent lawmakers.[14] According to Radio Free Europe, however, the measure was not signed by the then-President Viktor Yanukovych, who was subsequently removed from office.[15]

Fundamental Freedoms and basic elements of constitutional system

Article 1 of the Constitution defines Ukraine a sovereign, independent, social (welfare) state.

According to the Article 5 of the Constitution, the bearer of sovereignty and the single source of power in Ukraine are people. The people exercise their power directly and through state and local authorities. Nobody can usurp power in Ukraine.

The Article 15 of the Constitution established that public life in Ukraine is based on principles of political, economical and ideological diversity. No ideology could be recognized by the state as mandatory.

Freedom of religion is guaranteed by law, although religious organizations are required to register with local authorities and with the central government. The Article 35 of the Constitution defines that no religion could be recognized by the state as mandatory, while church and religious organizations in Ukraine are separated from state.

Minority rights are respected in accordance with a 1991 law guaranteeing ethnic minorities the right to schools and cultural facilities and the use of national languages in conducting personal business. According to the Ukrainian constitution, Ukrainian is the only official state language. However, in Crimea and some parts of eastern Ukraine—areas with substantial ethnic Russian minorities—use of Russian is widespread in official business.

Freedom of speech and press are guaranteed by law, but authorities sometimes interfere with the news media through different forms of pressure (see Freedom of the press in Ukraine). In particular, the failure of the government to conduct a thorough, credible, and transparent investigation into the 2000 disappearance and murder of independent journalist Georgiy Gongadze has had a negative effect on Ukraine's international image. Over half of Ukrainians polled by the Razumkov Center in early October 2010 (56.6%) believed political censorship existed in Ukraine.[16]

Official labor unions have been grouped under the Federation of Labor Unions. A number of independent unions, which emerged during 1992, among them the Independent Union of Miners of Ukraine, have formed the Consultative Council of Free Labor Unions. While the right to strike is legally guaranteed, strikes based solely on political demands are prohibited.

Executive branch

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Volodymyr Zelensky | Servant of the People | 20 May 2019 |

| Prime Minister | Denys Shmygal | Independent | 4 March 2020 |

The president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term.[17] The President nominates the Prime Minister, who must be confirmed by parliament. The Prime-minister and cabinet are de jure appointed by the Parliament on submission of the President and Prime Minister respectively. Pursuant to Article 114 of the Constitution of Ukraine.

Legislative branch

The Verkhovna Rada (Parliament of Ukraine) has 450 members, elected for a four-year term (five-year between 2006 and 2012 with the 2004 amendments). Prior to 2006, half of the members were elected by proportional representation and the other half by single-seat constituencies. Starting with the March 2006 parliamentary election, all 450 members of the Verkhovna Rada were elected by party-list proportional representation. The Verkhovna Rada initiates legislation, ratifies international agreements, and approves the budget.

The overall trust in legislative powers in Ukraine is very low.[18]

Political parties and elections

Ukrainian parties tend not to have clear-cut ideologies[19] but incline to centre around civilizational and geostrategic orientations (rather than economic and socio-political agendas, as in Western politics),[20] around personalities and business interests.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32] Party membership is lower than 1% of the population eligible to vote (compared to an average of 4.7% in the European Union[33]).[34][35]

Parties currently represented in the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament)

Template:Ukrainian Parliament changes after 2014 election

Former parliamentary parties

Template:Former parliamentarian parties and factions of the Verkhovna Rada

Presidential Election 2014

Originally scheduled to take place on 29 March 2015, the date was changed to 25 May 2014 following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution.[36][37] Petro Poroshenko won the elections with 54.7% of the votes.[38] His closest competitor was Yulia Tymoshenko, who emerged with 12.81% of the votes.[38] The Central Election Commission reported voter turnout at over 60% excluding those regions not under government control, Crimea and a large part of the Donbass.[39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47] Since Poroshenko obtained an absolute majority in the first round, a run-off second ballot was unnecessary.[48] Template:Ukrainian presidential election, 2014

Parliamentary Election 2012

Template:Ukrainian parliamentary election, 2012

Presidential Election 2010

Template:Ukrainian presidential election, 2010

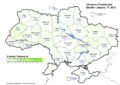

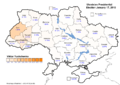

The first round of voting took place on January 17, 2010. Eighteen candidates nominated for election in which incumbent president Viktor Yushchenko was voted out of office having received only 5.45% of the vote. The two highest polling candidates, Viktor Yanukovych (34.32%) and Yulia Tymoshenko (25.05%), will face each other in a final run-off ballot scheduled to take place on February 7, 2010

-

Viktor Yanukovych (First round) - percentage of total national vote (35.33%)

-

Yulia Tymoshenko (First round) - percentage of total national vote (25.05%)

-

Serhiy Tihipko (First round) - percentage of total national vote (13.06%)

-

Arseniy Yatsenyuk (First round) - percentage of total national vote (6.69%)

-

Viktor Yushchenko (First round) - percentage of total national vote (5.46%)

-

Total vote distribution (First round) - percentage of total national vote

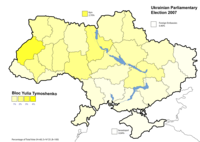

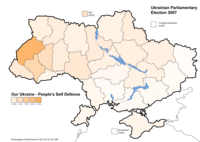

Parliamentary Election 2007

Template:Ukrainian parliamentary election, 2007

Presidential Election 2004

The initial second round of the Presidential Election 2004 (on November 17, 2004) was followed by the Orange Revolution, a series of peaceful protests that resulted in the nullification of the second round. The Supreme Court of Ukraine ordered a repeat of the re-run to be held on December 26, 2004, and asked the law enforcement agencies to investigate cases of election fraud.

Template:Ukrainian presidential election, 2004

Judicial branch

constitutional jurisdiction:

general jurisdiction:

- the Supreme Court of Ukraine;

- high specialized courts: the High Arbitration Court of Ukraine (Template:Lang-ua), the High Administrative Court of Ukraine;

- regional courts of appeal, specialized courts of appeal;

- local district courts.

Laws, acts of the parliament and the Cabinet, presidential edicts, and acts of the Crimean parliament (Autonomous Republic of Crimea) may be nullified by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, when they are found to violate the Constitution of Ukraine. Other normative acts are subject to judicial review. The Supreme Court of Ukraine is the main body in the system of courts of general jurisdiction.

The Constitution of Ukraine provides for trials by jury. This has not yet been implemented in practice. Moreover, some courts provided for by legislation as still in project, as is the case for, e.g., the Court of Appeals of Ukraine. The reform of the judicial branch is presently under way. Important is also the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, granted with the broad rights of control and supervision.

Local government

Administrative divisions of Ukraine are 24 oblasts (regions), with each oblast further divided into rayons (districts). The current administrative divisions remained the same as the local administrations of the Soviet Union. The heads of the oblast and rayon are appointed and dismissed by the President of Ukraine and serve as representatives of the central government in Kyiv. They govern over locally elected assemblies. This system encourages regional elites to compete fiercely for control over the central government and the position of the president.[49]

Autonomous Republic of Crimea

During 1992, a number of pro-Russian political organizations in Crimea advocated secession of Crimea and annexation to Russia. During USSR times Crimea was ceded from Russia to Ukraine in 1954 by First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev to mark the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav. In July 1992, the Crimean and Ukrainian parliaments determined that Crimea would remain under Ukrainian jurisdiction while retaining significant cultural and economic autonomy, thus creating the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

The Crimean peninsula—while under Ukraininan sovereignty, served as site for major military bases of both Ukrainian and Russian forces, and was heavily populated by ethnic Russians.

In early 2014, Ukraine's pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovich, was ousted by Ukraininans over his refusal to ally Ukraine with the European Union, rather than Russia. In response, Russia invaded Crimea in February 2014 and occupied it.

In March 2014,[50] a controversial referendum was held in Crimea with 97% of voters backing joining Russia.[51]

On 18 March 2014, Russia and the new, self-proclaimed Republic of Crimea signed a treaty of accession of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol in the Russian Federation. In response, the UN General Assembly passed non-binding resolution 68/262 declaring the referendum invalid, and officially supporting Ukraine's claim to Crimea. Although Russia administers the peninsula as two federal subjects, Ukraine and the majority of countries do not recognise Russia's annexation.[52][53]

International organization participation

BSEC, CE, CEI, CIS (participating), EAPC, EBRD, ECE, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICRM, IFC, IFRCS, IHO, ILO, IMF, IMO, Inmarsat, Intelsat (nonsignatory user), Interpol, IOC, IOM (observer), ISO, ITU, NAM (observer), NSG, OAS (observer), OPCW, OSCE, PCA, PFP, UN, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNIDO, UNMIBH, UNMIK, UNMOP, UNMOT, UPU, WCO, WFTU, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WToO, WTrO, Zangger Committee

See also

- List of Ukrainian politicians

- Declaration of Independence

- Proclamation of Independence

- Corruption in Ukraine

- Cassette Scandal

- Ukraine without Kuchma

- Orange Revolution

- Russia-Ukraine gas dispute

- Universal of National Unity

- 2007 Ukrainian political crisis

- NATO-Ukrainian relations

- Ukrainian nationalism

Center for Adaptation of Civil Service to the Standards of EU - public institution established by the Decree of Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine to facilitate administrative reform in Ukraine and to enhance the adaptation of the civil service to the standards of the European Union.

External links

- Ukraine: State of Chaos

- Short film: AEGEE's Election Observation Mission

- Kupatadze, Alexander: "Similar Events, Different Outcomes: Accounting for Diverging Corruption Patterns in Post-Revolution Georgia and Ukraine" in the Caucasus Analytical Digest No. 26

References

- ^ Populism in Ukraine in Comparative European Context, Taras Kuzio (24 April 2009)

- ^

Compare:

Kuzio, Taras (2005). "Semi-Authoritarianism in Kuchma's Ukraine". In Hayoz, Nicolas; Lushnycky, Andrej N. (eds.). Ukraine at a Crossroads. Vol. Volume 1 of Interdisciplinary studies on Central and Eastern Europe, ISSN 1661-1349. Bern: Peter Lang. p. 43. ISBN 9783039104680. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

Between elections, therefore, civil society and public activism are low and are often shut out of the decision making process. Delegative democracy thwarts democratic consolidation because it hampers the institutionalisation of democracy

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ The Making of Regions in Post-Socialist Europe: The Impact of Culture, Economic Structure and Institutions, Vol. II:Case Studies from Poland, Hungary, Romania and Ukraine by Melanie Tatur, VS Verlag, 2004, ISBN 978-3-8100-3814-2 (page 111)

- ^

Kuzio, Taras (2005). "Semi-Authoritarianism in Kuchma's Ukraine". In Hayoz, Nicolas; Lushnycky, Andrej N. (eds.). Ukraine at a Crossroads. Vol. Volume 1 of Interdisciplinary studies on Central and Eastern Europe, ISSN 1661-1349. Bern: Peter Lang. p. 43. ISBN 9783039104680. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

The over-centralisation of the state is a legacy of both the Soviet political system and the fear of Ukraine losing its independence through a break-up of the country.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ The Making of Regions in Post-Socialist Europe: The Impact of Culture, Economic Structure and Institutions, Vol. II:Case Studies from Poland, Hungary, Romania and Ukraine by Melanie Tatur, VS Verlag, 2004, ISBN 978-3-8100-3814-2 (page 349)

- ^ Dorell, Oren and Kim Hjelmgaard, "2 years after revolution, corruption plagues war-torn Ukraine,", Feb. 21, 2016, USA Today

- ^ New York Times Editorial Board, "Ukraine’s Unyielding Corruption," (editorial), March 30, 2016, New York Times.

- ^ "Ostrich zoo and vintage cars: The curse of corruption in Ukraine,", Jun 14th 2014, The Economist

- ^ "Fighting corruption in Ukraine: A serious challenge," (press release), Oct. 31, 2012., Transparency International

- ^ The Economist Intelligence Unit (8 January 2019). "Democracy Index 2018: Me Too?". The Economist Intelligence Unit. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Laws of Ukraine. Verkhovna Rada decree No. 2222-IV: About the amendments to the Constitution of Ukraine. Adopted on 2004-12-08. (Ukrainian)

- ^ Update: Return to 1996 Constitution strengthens president, raises legal questions, Kyiv Post (October 1, 2010)

- ^ OPINION ON THE CONSTITUTIONAL SITUATION IN UKRAINE dated December 20, 2010 - Source Venice Commission http://www.venice.coe.int/WebForms/documents/?pdf=CDL-AD(2010)044-e

- ^ a b c Ukrainian parliament reinstates 2004 Constitution, Interfax-Ukraine (21 February 2014)

- ^ Sindelar, Daisy (February 23, 2014). "Was Yanukovych's Ouster Constitutional?". Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty (Rferl.org). Retrieved February 25, 2014.

Yanukovych, however, failed to sign the measure.

- ^ Over half of Ukrainians feel political censorship, Kyiv Post (October 9, 2010)

- ^ "New Ukrainian president will be elected for 5-year term – Constitutional Court". Interfax-Ukraine. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ 84% of Ukrainians do not trust parliament Archived 2010-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Ukraine (December 23, 2009)

- ^ Against All Odds:Aiding Political Parties in Georgia and Ukraine by Max Bader, Vossiuspers UvA, 2010, ISBN 978-90-5629-631-5 (page 82)

- ^ Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle?, openDemocracy.net (January 3, 2011)

- ^ Black Sea Politics:Political Culture and Civil Society in an Unstable Region, I. B. Tauris, 2005, ISBN 978-1-84511-035-2 (page 45)

- ^ State-Building:A Comparative Study of Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, and Russia by Verena Fritz, Central European University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-963-7326-99-8 (page 189)

- ^ Political Parties of Eastern Europe:A Guide to Politics in the Post-Communist Era by Janusz Bugajski, M.E. Sharpe, 2002, ISBN 978-1-56324-676-0 (page 829)

- ^ Ukraine and European Society (Chatham House Papers) by Tor Bukkvoll, Pinter, 1998, ISBN 978-1-85567-465-3 (page 36)

- ^ How Ukraine Became a Market Economy and Democracy by Anders Åslund, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2009, ISBN 978-0-88132-427-3

- ^ The Rebirth of Europe by Elizabeth Pond, Brookings Institution Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-8157-7159-3 (page 146)

- ^ Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe by Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-36912-8 (page 383 and 396)

- ^ The Crisis of Russian Democracy:The Dual State, Factionalism and the Medvedev Succession by Richard Sakwa, Cambridge University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-521-14522-0 (page 110)

- ^ To Balance or Not to Balance:Alignment Theory And the Commonwealth of Independent States by Eric A. Miller, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-4334-0 (page 129)

- ^ Ukraine:Challenges of the Continuing Transition Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, National Intelligence Council (Conference Report August 1999)

- ^ Understanding Ukrainian Politics:Power, Politics, And Institutional Design by Paul D'Anieri, M. E. Sharpe, 2006, ISBN 978-0-7656-1811-5 (page 189)

- ^ Former German Ambassador Studemann views superiority of personality factor as fundamental defect of Ukrainian politics, Kyiv Post (December 21, 2009)

- ^ Research Archived 2012-01-16 at the Wayback Machine, European Union Democracy Observatory

- ^ Ukraine: Comprehensive Partnership for a Real Democracy, Center for International Private Enterprise, 2010

- ^ Poll: Ukrainians unhappy with domestic economic situation, their own lives, Kyiv Post (September 12, 2011)

- ^ "BBC News – Ukrainian president and opposition sign early poll deal". Bbc.co.uk. 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine president announces early elections – Europe". Al Jazeera English.

- ^ a b "Poroshenko wins presidential election with 54.7% of vote - CEC". Radio Ukraine International. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014.

(in Russian) Results election of Ukrainian president, Телеграф (29 May 2014) - ^ Interfax (2014-05-26). "Ukrainian presidential election turnout tops 60 percent - chief election official | Russia Beyond The Headlines". Rbth.com. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ^ "CEC chair: Ukrainian presidential election turnout tops 60 percent". Kyivpost.com. 2014-05-26. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ^ Ukraine elections: Runners and risks, BBC News (22 May 2014)

- ^ Q&A: Ukraine presidential election, BBC News (7 February 2010)

- ^ Ukraine crisis timeline, BBC News

- ^ EU & Ukraine 17 April 2014 FACT SHEET, European External Action Service (17 April 2014)

- ^ Gutterman, Steve. "Putin signs Crimea treaty, will not seize other Ukraine regions". Reuters.com. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ Poroshenko Declares Victory in Ukraine Presidential Election, The Wall Street Journal (25 May 2014)

- ^ Russia will recognise outcome of Ukraine poll, says Vladimir Putin, The Guardian (23 May 2014)

- ^ Ukraine talks set to open without pro-Russian separatists, The Washington Post (14 May 2014)

- ^ "The Politics of Regionalism". Eurasia Review. Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Russian Roulette: The Invasion of Ukraine (Dispatch One)". vicenews.com. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Official results: 97 percent of Crimea voters back joining Russia". cbsnews.com. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Alex Felton; Marie-Louise Gumuchian (27 March 2014). "U.N. General Assembly resolution calls Crimean referendum invalid". cnn.com. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Michel, Casey, [one-year-after-russias-annexation-world-has-forgotten-crimea "The Crime of the Century,"], March 4, 2015, The New Republic