Yorkshire

| Yorkshire | |

|---|---|

| Area and historic county | |

Location of Yorkshire from 1851 | |

| Area | |

| • Coordinates | 54°N 1°W / 54°N 1°W |

| History | |

| • Origin | Kingdom of Jórvík |

| • Succeeded by | Various |

| Status | Historic county |

| Chapman code | YKS |

| Contained within | |

| • Region (most of) | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| • Ceremonial counties (most of) | North Yorkshire • East Riding of Yorkshire • South Yorkshire • West Yorkshire |

| • Ceremonial counties (part of) | Greater Manchester • Lancashire • Cumbria • County Durham |

| Subdivisions | |

| • Type | Ridings (largest & most notable of differing former subdivisions) |

| • Units | 1 North • 2 West • 3 East |

| |

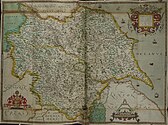

Yorkshire (/ˈjɔːrkʃər, -ʃɪər/ YORK-shər, -sheer) is an area of Northern England which was historically a county.[1] Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity.[2] The county was named after its original county town, the city of York.

The south-west of Yorkshire is densely populated, and includes the cities of Leeds, Sheffield, Bradford, Doncaster and Wakefield. The north and east of the county are more sparsely populated, however the north-east includes the southern part of the Teesside conurbation, and the port city of Kingston upon Hull is located in the south-east. York is located near the centre of the county. Yorkshire has a coastline to the North Sea to the east. The North York Moors occupy the north-east of the county, and the centre contains the Vale of Mowbray in the north and the Vale of York in the south. The west contains part of the Pennines, which form the Yorkshire Dales in the north-west.

The county was historically bordered by County Durham to the north, the North Sea to the east, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, and Cheshire to the south, and Lancashire and Westmorland to the west. It was the largest by area in the United Kingdom.[3] From the Middle Ages the county was subdivided into smaller administrative areas; the city of York was a self-governing county corporate from 1396, and the rest of the county was divided into three ridings – North, East, and West. From 1660 onwards each riding had its own lord-lieutenant, and between 1889 and 1974 the ridings were administrative counties. There was a Sheriff of Yorkshire until 1974. Yorkshire gives its name to four modern ceremonial counties: East Riding of Yorkshire, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, and West Yorkshire, which together cover most of the historic county.[a]

Yorkshire Day is observed annually on 1 August and is a celebration of the general culture of Yorkshire, including its history and dialect.[4] Its name is used by several institutions, for example the Royal Yorkshire Regiment of the British Army,[5] in sport, and in the media. The emblem of Yorkshire is a white rose, which was originally the heraldic badge of the British royal House of York. The county is sometimes referred to as "God's own country".[6] Yorkshire is represented in sport by Yorkshire County Cricket Club and Yorkshire Rugby Football Union.

Definitions

[edit]There are several ways of defining Yorkshire, including the historic county and the group of four modern ceremonial counties. The county boundaries were reasonably stable between 1182, when it ceded western areas to the new county of Lancashire,[7] and 1889 when administrative counties were created, which saw some adjustments to the boundaries with County Durham, Lancashire and Lincolnshire.[8][3] After 1889 there were occasional adjustments to accommodate urban areas which were developing across county boundaries, such as in 1934 when Dore and Totley were transferred from Derbyshire to Yorkshire on being absorbed into the borough of Sheffield.[9]

More significant changes in 1974 saw the historic county divided between several counties. The majority of the area was split between North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire, which all kept the Yorkshire name. A large part of the east of the county went to the new county of Humberside, and an area in the north-east went to the new county of Cleveland. Some more rural areas at the edges of the historic county were transferred to County Durham, Cumbria, Lancashire and Greater Manchester, whilst South Yorkshire also included areas which had been in Nottinghamshire.[10]

Cleveland and Humberside were both abolished in 1996, since when there have been four ceremonial counties with Yorkshire in their names: East Riding of Yorkshire, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire, which together cover most of the historic county.[11]

There is a region called Yorkshire and the Humber which covers a similar area to the combined area of the four Yorkshire ceremonial counties, the exceptions being that the region excludes the parts of North Yorkshire which had been in Cleveland, but includes North East Lincolnshire and North Lincolnshire (which had been in Humberside). Until 2009 some government powers in the region were devolved to the Yorkshire and Humber Assembly; since 2009 the region has been used primarily for presentation of statistics.

Etymology

[edit]Yorkshire is so named as it is the shire (administrative area or county) of the city of York, or York's Shire. The word "York" has an interesting etymology, first it is believed to have originated from the Celtic word "Eburakon", which means "Place of yew trees". This theory is supported by the fact that yew trees were once abundant in the area around York, and that the city was known for its skilled bow makers who used yew wood to make their bows. This became 'Eboracum' to the Romans, 'Eorfowic' to the Angles and then, most famously, 'Jorvik' to the Vikings. Secondly, and much less reliable, is that it may come from the Old English word "Eow", which referred to the yew tree (Taxus Baccata). Yew trees were highly valued in ancient times for their durable wood, which was used for making bows, spears, and other tools. Over time, the word evolved into "York", and it eventually came to refer to the city of York in England.[12][13] Either way, it is an evolved word for the magical 'Yew' tree.

History

[edit]Ancient–500: Hen Ogledd

[edit]Early: Celtic Brigantes and Parisi

[edit]Early inhabitants of what became Yorkshire were Hen Ogledd Brythonic Celts (old north British Celts), who formed separate tribes, the Brigantes (known to be in the north and western areas of now Yorkshire) and the Parisi (present-day East Riding). The Brigantes controlled territory that later became all of Northern England and more territory than most Celtic tribes on the island of Great Britain. Six of the nine Brigantian poleis described by Claudius Ptolemaeus in the Geographia fall within the historic county.[14][15]

The Parisi, who controlled the area that would become the East Riding, might have been related to the Parisii of Lutetia Parisiorum, Gaul (known today as Paris, France).[16] Their capital was at Petuaria, close to the Humber Estuary.

43–400s: Britannia Inferior

[edit]

Although the Roman conquest of Britain began in 43 AD, the Brigantes remained in control of their kingdom as a client state of Rome for an extended period, reigned over by the Brigantian monarchs Cartimandua and her husband Venutius. The capital was between the north and west ridings Isurium Brigantum (near Aldborough) civitas under Roman rule. Initially, this situation suited both the Romans and the Brigantes, who were known as the most militant tribe in Britain.[17]

Queen Cartimandua left Venutius for his armour bearer, Vellocatus, setting off a chain of events that changed control of the region. Cartimandua's good relationship with the Romans enabled her to keep control of the kingdom; however, her former husband staged rebellions against her and her Roman allies.[18] At the second attempt, Venutius seized the kingdom, but the Romans, under general Petillius Cerialis, conquered the Brigantes in 71 AD.[19]

The fortified city of Eboracum (now York) was named as capital of Britannia Inferior and joint capital of all Roman Britain.[20] The emperor Septimius Severus ruled the Roman Empire from Eboracum for the two years before his death.[21]

Another emperor, Constantius Chlorus, died in Eboracum during a visit in 306 AD. Thereafter his son Constantine the Great, who became renowned for his acceptance of Christianity, was proclaimed emperor in the city.[22] In the early 5th century, Roman rule ceased with the withdrawal of the last active Roman troops. By this stage, the Western Empire was in intermittent decline.[21]

500s–1000s: Germanic landings

[edit]500s–800s: Celtic-Anglo kingdoms of Ebrauc, Elmet, Deira and Northumbria

[edit]After the Romans left, small Celtic kingdoms arose in the region, including the kingdoms of Deira to the east (domain of settlements near Malton on Derwent), Ebrauc (domain of York) around the north and Elmet to the west. The latter two were successors of land south-west and north-east of the former Brigantia capital.

Angles (hailing from southern Denmark and northern Germany, probably along with Swedish Geats[23]) consolidated (merging Ebrauc) under Deira, with York as capital. This in turn was grouped with Bernicia, another former Celtic-Brigantes kingdom that was north of the River Tees and had come to be headed by Bamburgh, to form Northumbria.[24][25] Elmet had remained independent from the Germanic Angles until some time in the early 7th century, when King Edwin of Northumbria expelled its last king, Certic, and annexed the region to his Deira region. The Celts never went away, but were assimilated. This explains the existence of many Celtic placenames in Yorkshire today, such as Kingston upon Hull and Pen-y-ghent.[26]

As well as the Angles and Geats, other settlers included Frisians (thought to have founded Fryston and Frizinghall[27]), Danes, Franks and Huns.[28]

At its greatest extent, Northumbria stretched from the Irish Sea to the North Sea and from Edinburgh down to Hallamshire in the south.[29]

800s–900s: Jórvík

[edit]Scandinavian York (also referred to as Jórvík) or Danish/Norwegian York is a term used by historians for the south of Northumbria (modern-day Yorkshire) during the late 9th century and first half of the 10th century, when it was dominated by Norse warrior-kings; in particular, used to refer to York, the city controlled by these kings. Norse monarchy controlled varying amounts of Northumbria from 875 to 954, however the area was invaded and conquered for short periods by England between 927 and 954 before eventually being annexed into England in 954. It was closely associated with the much longer-lived Kingdom of Dublin throughout this period.

An army of Danish Vikings, the Great Heathen Army[30] as its enemies often referred to it, invaded Northumbrian territory in 866 AD. The Danes conquered and assumed what is now York and renamed it Jórvík, making it the capital city of a new Danish kingdom under the same name. The area which this kingdom covered included most of Southern Northumbria, roughly equivalent to the borders of Yorkshire extending further West.[31]

The Danes went on to conquer an even larger area of England that afterwards became known as the Danelaw; but whereas most of the Danelaw was still English land, albeit in submission to Viking overlords, it was in the Kingdom of Jórvík that the only truly Viking territory on mainland Britain was ever established. The Kingdom prospered, taking advantage of the vast trading network of the Viking nations, and established commercial ties with the British Isles, North-West Europe, the Mediterranean and the Middle East.[32]

Founded by the Dane Halfdan Ragnarsson in 875,[33] ruled for the great part by Danish kings, and populated by the families and subsequent descendants of Danish Vikings, the leadership of the kingdom nonetheless passed into Norwegian hands during its twilight years.[33] Eric Bloodaxe, an ex-king of Norway who was the last independent Viking king of Jórvík, is a particularly noted figure in history,[34] and his bloodthirsty approach towards leadership may have been at least partly responsible for convincing the Danish inhabitants of the region to accept English sovereignty so readily in the years that followed.

800s–1000s: Yorkshire

[edit]After around 100 years of its volatile existence, the Kingdom of Jorvik finally came to an end. The Kingdom of Wessex was now in its ascendancy and established its dominance over the North in general, placing Yorkshire again within Northumbria, which retained a certain amount of autonomy as an almost-independent earldom rather than a separate kingdom. The Wessex Kings of England were reputed to have respected the Norse customs in Yorkshire and left law-making in the hands of the local aristocracy.[35]

1000s–1400s: Normans

[edit]1000s–1100s: Harrying of the north

[edit]

In the weeks leading up to the Battle of Hastings in 1066 AD, Harold II of England was distracted by pushing back efforts to reinstate the kingdom of Jorvik and Danelaw. His brother Tostig and Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, having won the Battle of Fulford. The King of England marched north where the two armies met at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Tostig and Hardrada were both killed and their army was defeated decisively.

Harold Godwinson was forced immediately to march his army south, where William the Conqueror was landing. The King was defeated in what is now known as the Battle of Hastings, which led to the Norman conquest of England.

The people of the North rebelled against the Normans in September 1069 AD, enlisting Sweyn II of Denmark. They tried to take back York, but the Normans burnt it before they could.[36] What followed was the Harrying of the North ordered by William. From York to Durham, crops, domestic animals, and farming tools were scorched. Many villages between the towns were burnt and local northerners were indiscriminately murdered.[37] During the winter that followed, families starved to death and thousands of peasants died of cold and hunger. Orderic Vitalis estimated that "more than 100,000" people from the North died from hunger.[38]

In the centuries following, many abbeys and priories were built in Yorkshire. Norman landowners increased their revenues and established new towns such as Barnsley, Doncaster, Hull, Leeds, Scarborough and Sheffield, among others. Of towns founded before the conquest, only Bridlington, Pocklington, and York continued at a prominent level.[39]

In the early 12th century, people of Yorkshire had to contend with the Battle of the Standard at Northallerton with the Scots. Representing the Kingdom of England led by Archbishop Thurstan of York, soldiers from Yorkshire defeated the more numerous Scots.[40]

1300s: Scottish War of Independence and Mass Deaths

[edit]The population of Yorkshire boomed until it was hit by the Great Famine of 1315.[39] It did not help that after the English defeat in the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, the Scottish army rampaged throughout northern England, and Yorkshire was no exception. During The Great Raid of 1322, they raided and pillaged from the suburbs of York, even as far as East Riding and the Humber. Some like Richmond had to bribe the Scots to spare the town. The Black Death then reached Yorkshire by 1349, killing around a third of the population.[39]

1400s–1600s: Royal revolts

[edit]1400s: Wars of the Roses

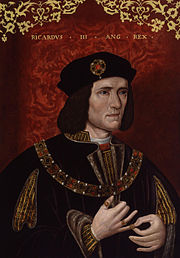

[edit]

When King Richard II was overthrown in 1399, antagonism between the House of York and the House of Lancaster, both branches of the royal House of Plantagenet, began to emerge. Eventually the two houses fought for the throne of England in a series of civil wars, commonly known as the Wars of the Roses. Some of the battles took place in Yorkshire, such as those at Wakefield and Towton, the latter of which is known as the bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil.[42] Richard III was the last Yorkist king.

Henry Tudor, sympathiser to the House of Lancaster, defeated and killed Richard at the Battle of Bosworth Field. He then became King Henry VII and married Elizabeth of York, daughter of Yorkist Edward IV, ending the wars.[43] The two roses of white and red, emblems of the Houses of York and Lancaster respectively, were combined to form the Tudor Rose of England.[b][44] This rivalry between the royal houses of York and Lancaster has passed into popular culture as a rivalry between the counties of Yorkshire and Lancashire, particularly in sport (for example the Roses Match played in County Cricket), although the House of Lancaster was based in York and the House of York in London.

1500: Catholic–Protestant dissolution

[edit]The English Reformation began under Henry VIII and the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536 led to a popular uprising known as Pilgrimage of Grace, started in Yorkshire as a protest. Some Catholics in Yorkshire continued to practise their religion and those caught were executed during the reign of Elizabeth I. One such person was a York woman named Margaret Clitherow who was later canonised.[45]

1600s: Civil war

[edit]

During the English Civil War, which started in 1642, Yorkshire had divided loyalties; Hull (full name Kingston upon Hull) famously shut the gates of the city on the king when he came to enter a few months before fighting began, while the North Riding of Yorkshire in particular was strongly royalist.[46][47] York was the base for Royalists, and from there they captured Leeds and Wakefield only to have them recaptured a few months later. The royalists won the Battle of Adwalton Moor meaning they controlled Yorkshire (with the exception of Hull). From their base in Hull the Parliamentarians ("Roundheads") fought back, re-taking Yorkshire town by town, until they won the Battle of Marston Moor and with it control of all of the North of England.[48]

1500s–1900s: Industry

[edit]1500-1600s: Explorative growth

[edit]In the 16th and 17th centuries Leeds and other wool-industry-centred towns continued to grow, along with Huddersfield, Hull and Sheffield, while coal mining first came into prominence in the West Riding of Yorkshire.[49] The wool textile industry, which had previously been a cottage industry, centred on the old market towns moved to the West Riding where entrepreneurs were building mills that took advantage of water power gained by harnessing the rivers and streams flowing from the Pennines. The developing textile industry helped Wakefield and Halifax grow.[50]

1800s: Victorian revolution

[edit]The 19th century saw Yorkshire's continued growth, with the population growing and the Industrial Revolution continuing with prominent industries in coal, textile and steel (especially in Sheffield, Rotherham and Middlesbrough). However, despite the booming industry, living conditions declined in the industrial towns due to overcrowding. This saw bouts of cholera in both 1832 and 1848.[51] However, advances were made by the end of the century with the introduction of modern sewers and water supplies. Several Yorkshire railway networks were introduced as railways spread across the country to reach remote areas.[52]

Canals and turnpike roads were introduced in the late 18th century. In the following century the spa towns of Harrogate and Scarborough flourished, due to people believing mineral water had curative properties.[53]

When elected county councils were established in 1889, rather than have a single Yorkshire County Council, each of the three ridings was made an administrative county with its own county council, and the eight larger towns and cities of Bradford, Halifax, Huddersfield, Hull, Leeds, Middlesbrough, Sheffield and York were made county boroughs, independent from the county councils.[54]

Twentieth century to present

[edit]During the Second World War, Yorkshire became an important base for RAF Bomber Command and brought the county and its productive industries into the cutting edge of the war, and thus in the targets of Luftwaffe bombers during the Battle of Britain.[55]

From the late 20th century onwards there have been a number of significant reforms of the local government structures covering Yorkshire, notably in 1968, 1974, 1986, 1996 and 2023, discussed in the governance section below. For most administrative purposes the county had been divided since the Middle Ages; the last county-wide administrative role was the Sheriff of Yorkshire. The sheriff had been a powerful position in the Middle Ages but gradually lost most of its functions, and by the twentieth century was a largely ceremonial role. It was abolished as part of the 1974 reforms to local government, which established instead high sheriffs for each modern county.[10]

Geography

[edit]Historically, the northern boundary of Yorkshire was the River Tees, the eastern boundary was the North Sea coast and the southern boundary was the Humber Estuary and Rivers Don and Sheaf. The western boundary meandered along the western slopes of the Pennine Hills to again meet the River Tees.[56]

Geology

[edit]

In Yorkshire there is a very close relationship between the major topographical areas and the geological period in which they were formed.[56] The Pennine chain of hills in the west is of Carboniferous origin. The central vale is Permo-Triassic. The North York Moors in the north-east of the county are Jurassic in age while the Yorkshire Wolds to the south east are Cretaceous chalk uplands.[56]

Rivers

[edit]

Yorkshire is drained by several rivers. In western and central Yorkshire the many rivers flow into the River Ouse which reaches the North Sea via the Humber Estuary.[57] The most northerly of the rivers in the Ouse system is the River Swale, which drains Swaledale before passing through Richmond and meandering across the Vale of Mowbray. Next, draining Wensleydale, is the River Ure, which the Swale joins east of Boroughbridge. Near Great Ouseburn the Ure is joined by the small Ouse Gill Beck, and below the confluence the river is known as the Ouse. The River Nidd rises on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales National Park and flows along Nidderdale before reaching the Vale of York and the Ouse.[57] The River Wharfe, which drains Wharfedale, joins the Ouse upstream of Cawood.[57] The Rivers Aire and Calder are more southerly contributors to the River Ouse and the most southerly Yorkshire tributary is the River Don, which flows northwards to join the main river at Goole. Further north and east the River Derwent rises on the North York Moors, flows south then westwards through the Vale of Pickering then turns south again to drain the eastern part of the Vale of York. It empties into the River Ouse at Barmby on the Marsh.[57]

In the far north of the county the River Tees flows eastwards through Teesdale and empties its waters into the North Sea downstream of Middlesbrough. The smaller River Esk flows from west to east at the northern foot of the North York Moors to reach the sea at Whitby.[57] To the east of the Yorkshire Wolds the River Hull flows southwards to join the Humber Estuary at Kingston upon Hull.

The western Pennines are drained by the River Ribble which flows westwards, eventually reaching the Irish Sea close to Lytham St Annes.[57]

Landscape

[edit]The countryside of Yorkshire has been called "God's Own County" by its inhabitants.[1][58] Yorkshire includes the North York Moors and Yorkshire Dales National Parks, and part of the Peak District National Park. Nidderdale and the Howardian Hills are designated Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty,[59] as is the North Pennines (a part of which lies within the county). Spurn Point, Flamborough Head and the coastal North York Moors are designated Heritage Coast areas,[60] and are noted for their scenic views with rugged cliffs[61] such as the jet cliffs at Whitby,[61] the limestone cliffs at Filey and the chalk cliffs at Flamborough Head.[62][63] Moor House – Upper Teesdale, most of which is part of the former North Riding of Yorkshire, is one of England's largest national nature reserves.[64] At High Force on the border with County Durham, the River Tees plunges 22 metres (72 ft) over the Whin Sill (an intrusion of igneous rock). High Force is not, as is sometimes claimed, the highest waterfall in England (Hardraw Force in Wensleydale, also in Yorkshire, has a 30 metres (98 ft) drop for example). However, High Force is unusual in being on a major river and carries a greater volume of water than any higher waterfall in England.[65]

The highest mountains in Yorkshire all lie in the Pennines on the western side of the county, with millstone grit and limestone forming the underlying geology and producing distinctive layered hills. The county top is the remote Mickle Fell[66] (height 788 metres (2,585 ft) above sea level) in the North Pennines southwest of Teesdale, which is also the highest point in the North Riding. The highest point in the West Riding is Whernside (height 736 metres (2,415 ft)) near to Ingleton in the Yorkshire Dales. Together with nearby Ingleborough (height 723 metres (2,372 ft)) and Pen-y-Ghent (height 694 metres (2,277 ft)), Whernside forms a trio of very prominent and popular summits (the Yorkshire Three Peaks) which can be climbed in a challenging single day's walk. The highest point in the Yorkshire part of the Peak District is Black Hill (height 582 metres (1,909 ft)) on the border with historic Cheshire (which also forms the historic county top of that county). The hill ranges along the eastern side of Yorkshire are lower than those of the west. The highest point of the North York Moors is Urra Moor (height 454 metres (1,490 ft)). The highest point of the Yorkshire Wolds, a range of low chalk downlands east of York, is Bishop Wilton Wold (height 246 metres (807 ft)), which is also the highest point of the East Riding. The view from Sutton Bank at the southeastern edge of the North York Moors near Thirsk encompasses a vast expanse of the Yorkshire lowlands with the Pennines forming a backdrop. It was called the "finest view in England" by local author and veterinary surgeon James Herriot in his 1979 guidebook James Herriot's Yorkshire.[67]

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds runs nature reserves such as the one at Bempton Cliffs with coastal wildlife such as the northern gannet, Atlantic puffin and razorbill.[68] Spurn Point is a narrow 3-mile (4.8 km) long sand spit. It is a national nature reserve owned by the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust and is noted for its cyclical nature whereby the spit is destroyed and re-created approximately once every 250 years.[69] There are seaside resorts in Yorkshire with sandy beaches; Scarborough is Britain's oldest seaside resort dating back to the spa town-era in the 17th century,[70] while Whitby has been voted as the United Kingdom's best beach, with a "postcard-perfect harbour".[71]

Towns and cities

[edit]There are eight officially designated cities in Yorkshire: Bradford, Doncaster, Kingston upon Hull, Leeds, Ripon, Sheffield, Wakefield, and York. City status is formally held by the administrative territory rather than the urban area.

| City | Status conferred | Territory holding status | Population 2021[72] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bradford | 1897[73] | Metropolitan borough | 546,500 |

| Doncaster | 2022[74][75] | Metropolitan borough | 308,100 |

| Kingston upon Hull | 1897[76][77] | Unitary authority | 267,100 |

| Leeds | 1893[78] | Metropolitan borough | 812,000 |

| Ripon | 1865[79] | Civil parish | 16,589 |

| Sheffield | 1893[78] | Metropolitan borough | 556,500 |

| Wakefield | 1888[80][81][82] | Metropolitan borough | 353,300 |

| York | Time immemorial | Unitary authority | 202,800 |

York is considered to have been a city since time immemorial. The other cities were formally awarded city status by the monarch; in the cases of Ripon and Wakefield following the creation of new Church of England dioceses, and in the other cases following significant urban growth.[83] Middlesbrough is the largest built-up area in Yorkshire not to be a city. The largest built-up areas at the 2021 census were as follows:

| Rank | County | Pop. | Rank | County | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Leeds  Sheffield |

1 | Leeds | West | 536,280 | 11 | Rotherham | South | 71,535 |  Bradford  Kingston upon Hull |

| 2 | Sheffield | South | 500,535 | 12 | Harrogate | North | 75,515 | ||

| 3 | Bradford | West | 333,950 | 13 | Barnsley | South | 71,405 | ||

| 4 | Kingston upon Hull | East | 270,810 | 14 | Dewsbury | West | 63,720 | ||

| 5 | Middlesbrough | North | 148,215 | 15 | Scarborough | North | 59,505 | ||

| 6 | York | North | 141,685 | 16 | Keighley | West | 48,750 | ||

| 7 | Huddersfield | West | 141,675 | 17 | Castleford | West | 45,355 | ||

| 8 | Wakefield | West | 97,870 | 18 | Batley | West | 44,500 | ||

| 9 | Halifax | West | 88,115 | 19 | Redcar | North | 37,660 | ||

| 10 | Doncaster | South | 87,455 | 20 | Pudsey | West | 34,850 | ||

Governance

[edit]There is no single Yorkshire-wide administrative body today. The area of the four ceremonial counties is administered by sixteen different local authorities, being nine metropolitan boroughs covering South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire and seven unitary authorities covering East Riding and North Yorkshire (one of which, Stockton-on-Tees, straddles the ceremonial boundary between North Yorkshire and County Durham).[85] Most of the authorities are grouped into combined authorities, each led by a directly elected mayor. The combined authorities for West Yorkshire, South Yorkshire and Tees Valley are already operating. A new York and North Yorkshire Combined Authority was established in February 2024 with its first mayor due to be elected in May 2024, and proposals for establishing a combined authority covering Hull and East Riding are being considered.[86]

Administrative hierarchy covering the four ceremonial counties as at March 2024:

| Combined authority | Status | Districts |

|---|---|---|

| South Yorkshire | Combined authority since 2014, led by mayor since 2018 | Barnsley |

| Doncaster | ||

| Rotherham | ||

| Sheffield | ||

| Tees Valley | Combined authority since 2016, led by mayor since 2017. Straddles ceremonial counties of North Yorkshire and County Durham. | Middlesbrough |

| Redcar and Cleveland | ||

| Stockton-on-Tees (south of River Tees in North Yorkshire, north of river in County Durham) | ||

| Also includes Darlington and Hartlepool from County Durham. | ||

| West Yorkshire | Combined authority since 2014, led by mayor since 2021 | Bradford |

| Calderdale | ||

| Kirklees | ||

| Leeds | ||

| Wakefield | ||

| York and North Yorkshire | Established February 2024, first mayor to be elected May 2024 | North Yorkshire |

| York | ||

| Hull and East Riding | Proposed, not yet operative | East Riding of Yorkshire |

| Kingston upon Hull |

The areas from the historic county that are not covered by the four ceremonial counties are now administered as parts of County Durham, Westmorland and Furness, Lancashire and Greater Manchester.

Administrative history

[edit]

Historically, Yorkshire was divided into three ridings. The term 'riding' is of Viking origin and derives from Threthingr (equivalent to third-ing). The three ridings in Yorkshire were named the East Riding, West Riding, and North Riding.[87] Each riding was divided into smaller areas called wapentakes with more local functions. York was made a county corporate in 1396,[88] as was Hull in 1440, making them independent from the ridings. York's corporate territory was enlarged in 1449 to also include an adjoining rural area known as the Ainsty.[89] Hull's corporate territory covered both the town and adjoining areas, which were sometimes together known as Hullshire.

The Sheriff of Yorkshire was the most senior official position within the county in the Middle Ages. In 1547 a separate post of Lord Lieutenant of Yorkshire was created, taking some of the functions previously held by the sheriff. The single lieutenancy was split in 1660 into separate posts for the East Riding, North Riding and West Riding. For the purposes of lieutenancy, York was deemed part of the West Riding, and Hull was deemed part of the East Riding.[90][91]

Elected county councils were established in 1889 under the Local Government Act 1888, taking over administrative functions previously performed by magistrates at the quarter sessions. The quarter sessions for Yorkshire were held separately for each riding.[92] As such, three county councils were established rather than one for the whole county: East Riding County Council based in Beverley, North Riding County Council based in Northallerton, and West Riding County Council based in Wakefield. Each riding was classed as an administrative county, but provision was made that the entire county of Yorkshire should continue to be one county for the purposes of shrievalty, allowing the Sheriff of Yorkshire to continue to serve the whole county. Certain towns and cities were deemed large enough to provide their own county-level services and so they were made county boroughs, independent from the county councils. There were initially eight county boroughs in Yorkshire, being Bradford, Halifax, Huddersfield, Hull, Leeds, Middlesbrough, Sheffield, and York.[54][93] Other county boroughs were subsequently created at Rotherham (1902), Barnsley (1913), Dewsbury (1913), Wakefield (1915) and Doncaster (1927).

More significant reviews of local government began to be considered following the Local Government Act 1958. The North Eastern General Review was held from 1962 to 1963, and led to the creation of the County Borough of Teesside in 1968, which covered the abolished county borough of Middlesbrough and several neighbours, including Stockton-on-Tees and Billingham, which had been in County Durham.[94] Teesside was deemed part of the North Riding for ceremonial purposes, although as a county borough it was independent from North Riding County Council.

Almost as soon as Teesside had been created work began on a far more significant overhaul of local government, culminating in the Local Government Act 1972, which took effect on 1 April 1974. The county boroughs and the administrative counties of the ridings were abolished, as were the lower tier municipal boroughs, urban districts and rural districts. A new set of counties and districts was put in place instead. Most of Yorkshire was split between North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, Humberside and Cleveland. Some peripheral rural areas were transferred to other counties, notably the Startforth area which went to County Durham, the Sedbergh area which went to Cumbria, the Forest of Bowland area which went to Lancashire, and Saddleworth which went to Greater Manchester.[10] Some of the changes were unpopular, particularly in Humberside.[95][96]

In 1986 the county councils for the metropolitan counties of South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire were abolished, with the metropolitan boroughs in those counties taking over county-level functions.[97] Humberside and Cleveland were both abolished in 1996 with new unitary authorities established to cover those areas. At the same time York was enlarged and also made a unitary authority, independent from North Yorkshire County Council.[95] The current ceremonial county boundaries were adopted at the time of the 1996 reforms, with a new ceremonial county called East Riding of Yorkshire created covering the parts of the abolished Humberside north of the Humber, whilst the parts of Cleveland south of the River Tees were added to North Yorkshire for ceremonial purposes.[11]

From the 1990s there were attempts to establish a regional tier of local government; a Yorkshire and the Humber region was designated in 1994, covering North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire and Humberside. Between 1998 and 2009 there was a Yorkshire and Humber Assembly comprising members of the region's local authorities and other stakeholders. Since 2009 the region has been primarily used for presentation of statistics rather than administration.

In 2014 the first combined authorities started to be established in Yorkshire, with South Yorkshire (which initially branded itself the "Sheffield City Region") and West Yorkshire having Yorkshire's first combined authorities. In 2018, eighteen of the twenty-two local councils in the Yorkshire and Humber region voted to create instead a much larger combined authority, which they proposed calling "One Yorkshire" which would have covered the region except North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire. The plan included provision for a directly elected mayor for the area, and the scheme's supporters estimated that it could create up to 200,000 jobs.[98][99][100] The One Yorkshire proposal was ultimately rejected by the government in 2019, which preferred to continue with rolling out smaller combined authorities for parts of Yorkshire instead.[101]

The districts of North Yorkshire were abolished in 2023, with North Yorkshire County Council taking over their functions to become a unitary authority, and rebranding itself North Yorkshire Council.[102]

Economy

[edit]South and West

[edit]

The City of Leeds is Yorkshire's largest city and the leading centre of trade and commerce. Leeds is also one of the UK's larger financial centres. Leeds's traditional industries were mixed, service-based industries, textile manufacturing and coal mining being examples. Tourism is also significant and a growing sector in the city. In 2015, the value of tourism was in excess of £7 billion.

Bradford, Halifax, Keighley and Huddersfield once were centres of wool milling. Areas such as Bradford, Dewsbury and Keighley have suffered a decline in their economy since.

Sheffield once had heavy industries, such as coal mining and the steel industry. Since the decline of such industries Sheffield has attracted tertiary and administrative businesses including more retail trade, Meadowhall being an example.

Coal mining was extremely active in the south of the county during the 19th century and for most of the 20th century, particularly around Barnsley and Wakefield. As late as the 1970s, the number of miners working in the area was still in six figures.[103] The industry was placed under threat on 6 March 1984 when the National Coal Board announced the closure of 20 pits nationwide (some of them in South Yorkshire). By March 2004, a mere three coalpits remained open in the area.[104] Three years later, the only remaining coal pit in the region was Maltby Colliery near Rotherham.[105] Maltby Colliery closed in 2013.[106]

East Riding and North

[edit]

North Yorkshire has an established tourist industry, supported by the presence of two national parks (Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors), Harrogate, York and Scarborough.

Tourism is a huge part of the economy of York with a value of over £765 million to the city and supporting 24,000 jobs in 2019.[107] Harrogate draws numerous visitors because of its conference facilities. In 2016 such events alone attracted 300,000 visitors to Harrogate.[108]

Kingston upon Hull is Yorkshire's largest port and has a large manufacturing base, its fishing industry has, however, declined somewhat in recent years. Businesses in Hull are Aunt Bessie's, Birds Eye, Seven Seas, Fenner, Rank Organisation, William Jackson Food Group, Reckitt and Sons, KCOM Group and SGS Europe.

Harrogate and Knaresborough both have small legal and financial sectors. Harrogate is a European conference and exhibition destination with both the Great Yorkshire Showground and Harrogate International Centre in the town. Bettys and Taylors of Harrogate is a notable company from Harrogate.

PD Ports owns and operates Teesport, between Middlesbrough and Redcar. The company also operates the Hull Container Terminal at the Port of Hull and owns a short river port in Howdendyke (near Howden).[109]

Other businesses in the two counties are Plaxton (Scarborough), McCains (Scarborough), Ebuyer (Howden) and Skipton Building Society (Skipton).

Education

[edit]Yorkshire has a large base of primary and secondary schools operated by both local authorities and private bodies, and a dozen universities, along with a wide range of colleges and further education facilities. Five universities are based in Leeds, two in Sheffield, two in York, and one each in Bradford, Hull, Middlesbrough and Huddersfield. The largest universities by enrolment are Sheffield Hallam University and the University of Leeds, each with over 31,000 students, followed by Leeds Beckett University, and the most recent to attain university status is the Leeds Arts University. There are also branches of institutions headquartered in other parts of England, such as the Open University and Britain's first for-profit university (since 2012), the University of Law. The tertiary sector is in active cooperation with industry, and a number of spin-off companies have been launched.

Transport

[edit]

The oldest road in Yorkshire, called the Great North Road, is now known as the A1.[110] This trunk road passes through the centre of the county and is the main route from London to Edinburgh.[citation needed] Another important road is the more easterly A19 road which starts in Doncaster and ends just north of Newcastle upon Tyne at Seaton Burn. The M62 motorway crosses the county from east to west from Hull towards Greater Manchester and Merseyside.[111] The M1 carries traffic from London and the south of England to Yorkshire. In 1999, about 8 miles (13 km) was added to make it swing east of Leeds and connect to the A1.[citation needed] The East Coast Main Line rail link between London and Scotland runs roughly parallel with the A1 through Yorkshire and the Trans Pennine rail link runs east to west from Hull to Liverpool via Leeds.[112]

Before the advent of rail transport, the seaports of Hull and Whitby played an important role in transporting goods. Historically canals were used, including the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, which is the longest canal in England. Mainland Europe (the Netherlands and Belgium) can be reached from Hull via regular ferry services from P&O Ferries.[113] Yorkshire also has air transport services from Leeds Bradford Airport. This airport has experienced significant and rapid growth in both terminal size and passenger facilities since 1996, when improvements began, until the present day.[114] From 2005 until 2022, South Yorkshire was served by Doncaster Sheffield Airport in Finningley.[115] Sheffield City Airport opened in 1997 after years of Sheffield having no airport, due to a council decision in the 1960s not to develop one because of the city's good rail links with London and the development of airports in other nearby areas. The newly opened airport never managed to compete with larger airports such as Leeds Bradford Airport and East Midlands Airport and attracted only a few scheduled flights, while the runway was too short to support low cost carriers. The opening of Doncaster Sheffield Airport effectively made the airport redundant and it officially closed in April 2008. The Doncaster Sheffield Airport has since closed and left South Yorkshire without an airport.

Public transport statistics

[edit]The average amount of time people spend on public transport in Yorkshire on a weekday is 77 minutes. 26.6% of public transport users travel for more than two hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transport is 16 minutes, while 24.9% of passengers wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transport is 7 km, while 10% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[116]

Architecture

[edit]Fortifications

[edit]Throughout Yorkshire many castles were built during the Norman-Breton period, particularly after the Harrying of the North. These included Bowes Castle, Pickering Castle, Richmond Castle, Skipton Castle, York Castle and others.[117] Later medieval castles at Helmsley, Middleham and Scarborough were built as a means of defence against the invading Scots.[118] Middleham is notable because Richard III of England spent his childhood there.[118] The remains of these castles, some being English Heritage sites, are popular tourist destinations.[118]

Stately

[edit]

There are stately homes in Yorkshire that carry the name "castle" in a similar way to the non-distinctive use of chateau in French. The most notable examples are Allerton Castle and Castle Howard, both linked to the Howard family.[119] Castle Howard and the Earl of Harewood's residence, Harewood House, are included amongst the nine Treasure Houses of England.[120]

Large estates with significant buildings were constructed at Brodsworth Hall, Temple Newsam, Wentworth Woodhouse (the largest fronted private home in Europe), and Wentworth Castle. There are properties which are conserved and managed by the National Trust, such as Nunnington Hall, Ormesby Hall, the Rievaulx Terrace & Temples and Studley Royal Park.[121]

Industrial

[edit]Buildings built for industry during the Victorian era are found throughout the region; West Yorkshire has various cotton mills, the Leeds Corn Exchange and the Halifax Piece Hall.[122]

Municipal

[edit]

There are various buildings built for local authorities:

- Grade I listed; Leeds Town Hall, Sheffield Town Hall, Wakefield County Hall and York Guildhall

- Grade II* listed; Middlesbrough Town Hall, Leeds Civic Hall, Hull Guildhall, Hull City Hall and Sheffield City Hall.

Religious

[edit]

Religious architecture includes extant cathedrals as well as the ruins of monasteries and abbeys. Many of these prominent buildings suffered from the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII; these include Bolton Abbey, Fountains Abbey, Gisborough Priory, Rievaulx Abbey, St Mary's Abbey and Whitby Abbey among others.[123] Notable religious buildings of historic origin still in use include York Minster, the largest Gothic cathedral in northern Europe,[123] Beverley Minster, Bradford Cathedral, Rotherham Minster and Ripon Cathedral.[123]

Culture

[edit]The culture of the people of Yorkshire is an accumulated product of a number of different civilisations who have influenced its history, including; the Celts (Brigantes and Parisii), Romans, Angles, Norse Vikings, and Normans amongst others.[124] The western part of the historic North Riding had an additional infusion of Breton culture due to the Honour of Richmond being occupied by Alain Le Roux, grandson of Geoffrey I, Duke of Brittany.[125] The people of Yorkshire are immensely proud of their county and local culture, and it is sometimes suggested they identify more strongly with their county than they do with their country.[126] Yorkshire people have their own Yorkshire dialects and accents and are, or rather were, known as Broad Yorkshire or Tykes, with its roots in Old English and Old Norse.[127][128]

The British Library provides a four minute long voice recording made in 1955, by a "female housekeeper", Miss Madge Dibnahon, on its web site and an example of the Yorkshire dialect used at that time, in an unstated location. "Much of her speech remains part of the local dialect to this day", according to the Library.[129][130] Due to the large size of Yorkshire, spoken dialects vary between areas. In fact, the dialect in North Yorkshire and Humberside/East Yorkshire is "quite different [than in West Yorkshire and South Yorkshire] and has a much stronger Scandinavian influence".[131]

One report explains the geographic difference in detail:[131]

This distinction was first recognised formally at the turn of the 19th / 20th centuries, when linguists drew an isophone diagonally across the county from the northwest to the southeast, separating these two broadly distinguishable ways of speaking. It can be extended westwards through Lancashire to the estuary of the River Lune, and is sometimes called the Humber-Lune Line. Strictly speaking, the dialects spoken south and west of this isophone are Midland dialects, whereas the dialects spoken north and east of it are truly Northern. It is possible that the Midland form moved up into the region with people gravitating towards the manufacturing districts of the West Riding during the Industrial Revolution.

Though distinct accents remain, dialect has declined heavily in everyday use. Some have argued the dialect was a fully fledged language in its own right.[132] The county has also produced a set of Yorkshire colloquialisms,[133] which are in use in the county. Among Yorkshire's traditions is the Long Sword dance. The most famous traditional song of Yorkshire is On Ilkla Moor Baht 'at ("On Ilkley Moor without a hat"), it is considered the unofficial anthem of the county.[134]

Literature and art

[edit]

Although the first Professor of English Literature at Leeds University, F. W. Moorman, claimed the first extant work of English literature, Beowulf, was written in Yorkshire,[135] this view does not have common acceptance today. However, when Yorkshire formed the southern part of the kingdom of Northumbria there were several notable poets, scholars and ecclesiastics, including Alcuin, Cædmon and Wilfrid.[136] The most esteemed literary family from the county are the three Brontë sisters, with part of the county around Haworth being nicknamed Brontë Country in their honour.[137] Their novels, written in the mid-19th century, caused a sensation when they were first published, yet were subsequently accepted into the canon of great English literature.[138] Among the most celebrated novels written by the sisters are Anne Brontë's The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre and Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights.[137] Wuthering Heights was almost a source used to depict life in Yorkshire, illustrating the type of people that reside there in its characters, and emphasising the use of the stormy Yorkshire moors. Nowadays, the parsonage which was their former home is now a museum in their honour.[139] Bram Stoker authored Dracula while living in Whitby[140] and it includes several elements of local folklore including the beaching of the Russian ship Dmitri, which became the basis of Demeter in the book.[141]

The novelist tradition in Yorkshire continued into the 20th and 21st centuries, with authors such as J. B. Priestley,[142] Alan Bennett, Stan Barstow, Dame Margaret Drabble, Winifred Holtby (South Riding, The Crowded Street), A. S. Byatt, Barbara Taylor Bradford,[143] Marina Lewycka and Sunjeev Sahota being prominent examples. Taylor Bradford is noted for A Woman of Substance which was one of the top-ten best selling novels in history.[144] Another well-known author was children's writer Arthur Ransome, who penned the Swallows and Amazons series.[143] James Herriot, the best selling author of over 60 million copies of books about his experiences of some 50 years as a veterinarian in Thirsk, North Yorkshire, the town which he refers to as Darrowby in his books[145] (although born in Sunderland), has been admired for his easy reading style and interesting characters.[146]

Poets include Ted Hughes, W. H. Auden, William Empson, Simon Armitage, David Miedzianik and Andrew Marvell.[143][147][148][149][150] Three well known sculptors emerged in the 20th century; contemporaries Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, and Leeds-raised land artist Andy Goldsworthy. Some of their works are available for public viewing at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.[151] There are several art galleries in Yorkshire featuring extensive collections, such as Ferens Art Gallery, Leeds Art Gallery, Millennium Galleries and York Art Gallery.[152][153][154] Some of the better known local painters are William Etty and David Hockney;[155] many works by the latter are housed at Salts Mill 1853 Gallery in Saltaire.[156]

Cuisine

[edit]

The traditional cuisine of Yorkshire, in common with the North of England in general, is known for using rich-tasting ingredients, especially with regard to sweet dishes, which were affordable for the majority of people.[157] There are several dishes which originated in Yorkshire or are heavily associated with it.[157] Yorkshire pudding, a savoury batter dish, is by far the best known of Yorkshire foods, and is eaten throughout England. It is commonly served with roast beef and vegetables to form part of the Sunday roast[157] but is traditionally served as a starter dish filled with onion gravy within Yorkshire.[158] Yorkshire pudding is the base for toad in the hole, a dish containing sausage.[159]

Other foods associated with the county include Yorkshire curd tart, a curd tart recipe with rosewater;[160] parkin, a sweet ginger cake which is different from standard ginger cakes in that it includes oatmeal and treacle;[161] and Wensleydale cheese, a cheese made with milk from Wensleydale and often eaten as an accompaniment to sweet foods.[162] The beverage ginger beer, flavoured with ginger, came from Yorkshire and has existed since the mid-18th century. Liquorice sweet was first created by George Dunhill from Pontefract, who in the 1760s thought to mix the liquorice plant with sugar.[163] Yorkshire and in particular the city of York played a prominent role in the confectionery industry, with chocolate factories owned by companies such as Rowntree's, Terry's and Thorntons inventing many of Britain's most popular sweets.[164][165] Another traditional Yorkshire food is pikelets, which are similar to crumpets but much thinner.[166] The Rhubarb Triangle is a location within Yorkshire which supplies most of the rhubarb to locals.

In recent years curries have become popular in the county, largely due to the immigration and successful integration of Asian families. There are many famous curry empires with their origins in Yorkshire, including the 850-seater Aakash restaurant in Cleckheaton, which has been described as "the world's largest curry house".[167]

Beer and brewing

[edit]Yorkshire has a number of breweries including Black Sheep, Copper Dragon, Cropton Brewery, John Smith's, Samuel Smith Old Brewery, Kelham Island Brewery, Theakstons, Timothy Taylor, Wharfedale Brewery, Harrogate Brewery and Leeds Brewery.[168][169] The beer style most associated with the county is bitter.[170] As elsewhere in the North of England, when served through a handpump, a sparkler is used giving a tighter, more solid head.[171]

Brewing has taken place on a large scale since at least the 12th century, for example at the now derelict Fountains Abbey which at its height produced 60 barrels of strong ale every ten days.[172] Most current Yorkshire breweries date from the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th century.[168]

Music

[edit]

Yorkshire has a heritage of folk music and folk dance including the Long Sword dance.[173] Yorkshire folk song was distinguished by the use of dialect, particularly in the West Riding and exemplified by the song 'On Ilkla Moor Baht 'at', probably written in the late 19th century, using a Kent folk tune (almost certainly borrowed via a Methodist hymnal),[citation needed] seen as an unofficial Yorkshire anthem.[174] Famous folk performers from the county include the Watersons from Hull, who began recording Yorkshire versions of folk songs from 1965;[175] Heather Wood (born 1945) of the Young Tradition; the short-lived electric folk group Mr Fox (1970–72), the Deighton Family; Julie Matthews; Kathryn Roberts; and Kate Rusby.[175] Yorkshire has a flourishing folk music culture, with over forty folk clubs and thirty annual folk music festivals.[176] The 1982 Eurovision Song Contest was held in the Harrogate International Centre. In 2007 the Yorkshire Garland Group was formed to make Yorkshire folk songs accessible online and in schools.[177]

In the field of classical music, Yorkshire has produced some major and minor composers, including Frederick Delius, George Dyson, Philip Wilby, Edward Bairstow, William Baines, Kenneth Leighton, Bernadette Farrell, Eric Fenby, Anne Quigley, Haydn Wood, Arthur Wood, Arnold Cooke, Gavin Bryars, John Casken, and in the area of TV, film and radio music, John Barry and Wally Stott. Opera North is based at the Grand Theatre, Leeds. Leeds is also home to the Leeds International Piano Competition. The Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival takes place annually in November. Huddersfield Choral Society is one of the UK's most celebrated amateur choirs.[178] The National Centre for Early Music is located in York.

The county is home to successful brass bands such as Black Dyke, Brighouse & Rastrick, Carlton Main Frickley, Hammonds Saltaire, and Yorkshire Imperial.

During the 1970s David Bowie, himself of a father from Doncaster in the West Riding of Yorkshire,[179] hired three musicians from Hull: Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Mick Woodmansey; together they recorded Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, an album considered by a magazine article as one of a 100 greatest and most influential of all time.[180] In the following decade, Def Leppard, from Sheffield, achieved worldwide fame, particularly in America. Their 1983 album Pyromania and 1987 album Hysteria are among the most successful albums of all time.[citation needed] Yorkshire had a very strong post-punk scene which went on to achieve widespread acclaim and success, including: the Sisters of Mercy, the Cult, Vardis, Gang of Four, ABC, the Human League, New Model Army, Soft Cell, Chumbawamba, the Wedding Present and the Mission.[181] Pulp from Sheffield had a massive hit in "Common People" during 1995; the song focuses on working-class northern life.[182] In the 21st century, indie rock and post-punk revival bands from the area gained popularity, including the Kaiser Chiefs, the Cribs and the Arctic Monkeys, the last-named holding the record for the fastest-selling debut album in British music history with Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not.[183]

Influenced by the local post punk scene, but also by national and international extreme metal acts such as Celtic Frost, Candlemass, and Morbid Angel, Yorkshire-based bands Paradise Lost and My Dying Bride laid the foundations of what would become the Gothic Metal genre in the early to mid-1990s.[184][185]

Television productions

[edit]Among prominent British television shows filmed in (and based on) Yorkshire are the soap opera Emmerdale and the sitcom Last of the Summer Wine; the latter in particular is noted for holding the record of longest-running comedy series in the world, from 1973 until 2010.[186] Other notable television series set in Yorkshire include Downton Abbey, All Creatures Great and Small, The Beiderbecke Trilogy, Rising Damp, Open All Hours, Band Of Gold, Dalziel and Pascoe, Fat Friends, Heartbeat, The Syndicate, No Angels, Drifters and The Royal. During the first three series of the sitcom The New Statesman, Alan B'Stard represented as MP the fictional constituency of Haltenprice in North Yorkshire.

Yorkshire has remained a popular location for filming in more recent times.[187][188] For example, much of ITV's highly acclaimed Victoria was filmed in the region, at locations such as Harewood House in Leeds and Beverley Minster (the latter being used to depict Westminster Abbey and St James' Palace),[189][190] whilst Channel 5 has programmed numerous Yorkshire-themed documentary series such as Our Yorkshire Farm and The Yorkshire Steam Railway: All Aboard across its schedule.[191][192]

West Yorkshire has particularly benefited from a great deal of production activity.[193][194] For example, portions of the BBC television series Happy Valley and Last Tango in Halifax were filmed in the area, in Huddersfield and other cities; in addition to exteriors, some of the studio filming for Happy Valley was done at North Light Film Studios at Brookes Mill, Huddersfield. Although set in the fictional town of Denton, popular ITV detective series A Touch Of Frost was filmed in Yorkshire, mainly in and around Leeds. The BBC's Jamaica Inn and Remember Me and the ITV series Black Work were also filmed at the studios and in nearby West Yorkshire locations.[195][196][197][198] More recently, many of the exteriors of the BBC series Jericho were filmed at the nearby Rockingstone Quarry, and some interior work was done at North Light Film Studios.[199]

Film productions

[edit]Several noted films are set in Yorkshire, including Kes, This Sporting Life, Room at the Top, Brassed Off, Mischief Night, Rita, Sue and Bob Too, The Damned United, Four Lions, God's Own Country and Calendar Girls. The Full Monty, a comedy film set in Sheffield, won an Academy Award and was voted the second-best British film of all time by Asian News International.[200]

Sport

[edit]Yorkshire has a long tradition in the field of sports, with participation in cricket, football, rugby league and horse racing being the most established sporting ventures.[201][202][203][204]

Cricket

[edit]Yorkshire County Cricket Club represents the historic county in the domestic first class cricket County Championship; with a total of 33 championship titles (including one shared), 13 more than any other county, Yorkshire is the most decorated county cricket club.[203] Some of the most highly regarded figures in the game were born in the county, amongst them:[205]

The four ECB Premier Leagues in the county are: Bradford, North-Yorkshire-&-South-Durham, Yorkshire North and Yorkshire South. The league winners qualify to take part in a yearly Yorkshire Championship, the highest NYSD club based in Yorkshire qualifies if a Durham side wins.[206]

Football

[edit]Association

[edit]

Football clubs founded in Yorkshire include, four of which have been league champions:

Yorkshire is officially recognised by FIFA as the birthplace of club football,[207][208] as Sheffield FC founded in 1857 are certified as the oldest association football club in the world.[209] The world's first inter-club match and local derby was competed in the county, at the world's oldest ground Sandygate Road.[210] The Laws of the Game, used worldwide, were drafted by Ebenezer Cobb Morley from Hull.[211]

Huddersfield were the first club to win three consecutive league titles.[212] Leeds United reached the 2001 UEFA Champions League semi-finals and had a dominance period in the 1970s. Sheffield Wednesday who have had similar spells of dominance, such as the early 1990s. Middlesbrough won the 2004 League Cup and reach the 2006 UEFA Cup Final.[213][214]

Noted players from Yorkshire who have influenced the game include World Cup-winning goalkeeper Gordon Banks and two time European Footballer of the Year award winner Kevin Keegan.[215][216] Prominent managers include Herbert Chapman, Brian Clough, Bill Nicholson, George Raynor and Don Revie.[217]

The Yorkshire football team, controlled by the Yorkshire International Football Association (YIFA), represents Yorkshire in CONIFA matches. The team was founded in 2017, joined CONIFA on 6 January 2018 and plays at various venues throughout Yorkshire.[218][219]

Rugby Union

[edit]Yorkshire has a long history of rugby union in the county with Leeds Tykes (formerly Yorkshire Carnegie) featuring in the Aviva Premiership for eight seasons between 2001 and 2011 when they were relegated to the Championship. From 2020 the teams has reverted to its amateur status and plays in National League 1. Rotherham Titans also played in the top tier of English rugby in 2000–01 and 2003–04.[220]

Many England international players have emerged from Yorkshire including World Cup winners Jason Robinson and Mike Tindall.[221] Other successful players from the region include Rob Andrew, Tim Rodber, Brian Moore, Danny Care, Rory Underwood and Sir Ian McGeechan.

| League | Team | Venue | Capacity | Location, county |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFU Championship | Doncaster Knights | Castle Park | 5,000 (1,650 seats) | Doncaster, South Yorkshire |

| National League 2 North | Huddersfield | Lockwood Park | 1,500 (500 seats) | Huddersfield, West Yorkshire |

| Hull | Ferens Ground | 1,500 (288 seats) | Kingston upon Hull, East Riding | |

| Hull Ionians | Brantingham Park | 1,500 (240 seats) | Brantingham, East Riding | |

| Leeds Tykes | The Sycamores | Bramhope, Leeds, West Yorkshire | ||

| Otley | Cross Green | 5,000 | Otley (Leeds), West Yorkshire | |

| Rotherham Titans | Clifton Lane | 2,500 | Rotherham, South Yorkshire | |

| Sheffield | Abbeydale Park | 3,200 (100 seats) | Sheffield, South Yorkshire | |

| Sheffield Tigers | Dore Moor | Sheffield, South Yorkshire | ||

| Wharfedale | The Avenue | 2,000 | Threshfield, North Yorkshire | |

| Regional 1 North East | Cleckheaton | Moorend | Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire | |

| Doncaster Phoenix | Castle Park | 5,000 (1,650 seats) | Doncaster, South Yorkshire | |

| Driffield | Show Ground | Driffield, East Riding of Yorkshire | ||

| Harrogate | Rudding Lane | Harrogate, North Yorkshire | ||

| Heath | West Vale | West Vale, Halifax, West Yorkshire | ||

| Ilkley | Stacks Field | 2,000 (40 seats) | Ilkley, West Yorkshire | |

| Pontefract | Moor Lane | Pontefract, West Yorkshire | ||

| Sandal | Milnthorpe Green | Sandal Magna (Wakefield), West Yorkshire | ||

| York | Clifton Park | York, North Yorkshire |

Rugby League

[edit]

The Rugby Football League and with it the sport of rugby league was founded in 1895 at the George Hotel, Huddersfield, after a North-South schism within the Rugby Football Union.[222] The top league is the Super League and the most decorated Yorkshire clubs are Huddersfield Giants, Hull FC, Bradford Bulls, Hull Kingston Rovers, Wakefield Trinity, Castleford Tigers and Leeds Rhinos.[223] In total six Yorkshiremen have been inducted into the Rugby Football League Hall of Fame amongst them is Roger Millward, Jonty Parkin and Harold Wagstaff.[224]

Multi-sport events

[edit]In the area of boxing "Prince" Naseem Hamed from Sheffield achieved title success and widespread fame,[225] in what the BBC describes as "one of British boxing's most illustrious careers".[225] Along with Leeds-born Nicola Adams who in 2012 became the first female athlete to win a boxing gold medal at the Olympics.[226]

A number of athletes from or associated with Yorkshire took part in the 2012 Summer Olympics as members of Team GB; the Yorkshire Post stated that Yorkshire's athletes alone secured more gold medals than those of Spain.[227] Notable Yorkshire athletes include Jessica Ennis-Hill and the Brownlee brothers, Jonathan and Alistair. Jessica Ennis-Hill is from Sheffield and won gold at the 2012 Olympics in London and silver at the 2016 Olympics in Rio. Triathletes Alastair and Jonny Brownlee have won two golds and a silver and bronze respectively.

Animal related

[edit]

Yorkshire has nine horseracing courses: in North Yorkshire there are Catterick, Redcar, Ripon, Thirsk and York; in the East Riding of Yorkshire there is Beverley; in West Yorkshire there are Pontefract and Wetherby; while in South Yorkshire there is Doncaster.[228]

England's oldest horse race, which began in 1519, is run each year at Kiplingcotes near Market Weighton.[204] Britain's oldest organised fox hunt is the Bilsdale, founded in 1668.[229][230]

Knurr and Spell

[edit]The sport of Knurr and Spell was unique to the region, being one of the most popular sports in the area during the 18th and 19th centuries, before a decline in the 20th century to virtual obscurity.[231][232][233]

Cycling

[edit]

Yorkshire is considered to be particularly fond of cycling. In 2014 Yorkshire hosted the Grand Départ of the Tour de France. Spectator crowds over the two days were estimated to be of the order of 2.5 million people, making it the highest attended event in the UK.[234] The inaugural Tour de Yorkshire was held from 1–3 May 2015,[235] with start and finishes in Bridlington, Leeds, Scarborough, Selby, Wakefield and York,[236] watched by 1.2 million.[237] Yorkshire hosted the 2019 UCI Road World Championships between 22 and 29 September, which were held in Harrogate.[238] Notable racing cyclists from Yorkshire include Brian Robinson, Lizzie Deignan and Beryl Burton.[239]

Hockey

[edit]Field

[edit]Field Hockey is a popular game in Yorkshire with 58 clubs running 271 organised teams.[240] The largest clubs include City of York HC (16 teams), Doncaster HC, Leeds HC and Sheffield Hallam HC (all 14 teams). The most recent team from Yorkshire to have played in the EH Premier League was Sheffield Hallam who finished in 9th place in 2013–14.[241] England and Great Britain's most capped player of all time Barry Middleton hails from the town of Doncaster.[242] Hockey was formerly organised by the Yorkshire Hockey Association but is now run by Yorkshire & North East Hockey who have run leagues and organised representative teams since September 2021.

| League | Team | Venue | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHL Division 1 North | Leeds | Weetwood Playing Fields | Leeds, West Yorkshire |

| MHL Conference North | Ben Rhydding | Coutances Way | Ilkley, West Yorkshire |

| Doncaster | Town Field Sports Club | Doncaster, South Yorkshire | |

| Sheffield Hallam | Abbeydale Park | Sheffield, South Yorkshire | |

| Wakefield | College Grove | Wakefield, West Yorkshire |

| League | Team | Venue | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHL Division 1 North | Ben Rhydding | Coutances Way | Ilkley, West Yorkshire |

| Wakefield | College Grove | Wakefield, West Yorkshire | |

| WHL Conference Midlands | Doncaster | Town Fields Sports Club | Doncaster, South Yorkshire |

| WHL Conference North | Harrogate | Granby Hockey Centre | Harrogate, North Yorkshire |

| Leeds | Weetwood Playing Fields | Leeds, West Yorkshire |

Other professional sports franchise teams

[edit]Sheffield is home to the Sheffield Sharks who play in the British Basketball League and, from 2021, Leeds Rhinos have featured in the Netball Superleague.

Politics and identity

[edit]Constituencies

[edit]

From 1290, Yorkshire was represented by two members of parliament of the House of Commons of the Parliament of England. After the union with Scotland, two members represented the county in the Parliament of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800 and of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1832. In 1832 the county benefited from the disfranchisement of Grampound by taking an additional two members.[245] Yorkshire was represented at this time as one single, large, county constituency.[245] Like other counties, there were also some parliamentary boroughs within Yorkshire, the oldest of which was the City of York, which had existed since the ancient Montfort's Parliament of 1265. After the Reform Act 1832, Yorkshire's political representation in parliament was drawn from its subdivisions, with members of parliament representing each of the three historic Ridings of Yorkshire; East Riding, North Riding, and West Riding constituencies.[245]

For the 1865 general elections and onwards, the West Riding was further divided into Northern, Eastern and Southern parliamentary constituencies, though these only lasted until the major Redistribution of Seats Act 1885.[246] This act saw more localisation of government in the United Kingdom, with the introduction of 26 new parliamentary constituencies within Yorkshire.

With the Representation of the People Act 1918 there was some reshuffling on a local level for the 1918 general election, revised again during the 1950s.[247]

Distinctive identity

[edit]A number of claims have been made for the distinctiveness of Yorkshire, as a geographical, cultural and political entity, and these have been used to demand increased political autonomy. In the early twentieth century, F. W. Moorman, the first professor of English language at Leeds University, claimed Yorkshire was not settled by Angles or Saxons following the end of Roman rule in Britain, but by a different Germanic tribe, the Geats. As a consequence, he claimed, it is possible the first work of English literature, Beowulf, believed to have been composed by Geats, was written in Yorkshire, and this distinctive ethnic and cultural origin is the root of the unique status of Yorkshire today.[135] One of Moorman's students at Leeds University, Herbert Read, was greatly influenced by Moorman's ideas on Yorkshire identity, and claimed that until recent times Yorkshire was effectively an island, cut off from the rest of England by rivers, fens, moors and mountains. This distancing of Yorkshire from England led Read to question whether Yorkshire people were really English at all.[248] Combined with the suggested ethnic difference from the rest of England, Read quoted Frederic Pearson, who wrote:

There is something characteristic about the very physiognomy of the Yorkshireman. He is much more of a Dane or a Viking than a Saxon. He is usually a big upstanding man, who looks as if he could take care of himself and those who depend upon him in an emergency. This is indeed the character that his neighbours give him; the southerner may think him a little hard: but if ever our country is let down by its inhabitants, we may be sure that it will not be the fault of Yorkshire.[248]

During the premiership of William Pitt the Younger the hypothetical idea of Yorkshire becoming independent was raised in the British parliament in relation to the question whether Ireland should become part of the United Kingdom. This resulted in the publication of an anonymous pamphlet in London in 1799 arguing at length that Yorkshire could never be an independent state as it would always be reliant on the rest of the United Kingdom to provide it with essential resources.[249]

Although in the devolution debates in the House of Commons of the late 1960s, which paved the way for the 1979 referendums on the creation of a Scottish parliament and Welsh assembly, parallel devolution for Yorkshire was suggested, this was opposed by the Scottish National Party Member of Parliament for Hamilton, Winifred Ewing. Ewing argued that it was offensive to Scots to argue that an English region had the same status as an 'ancient nation' such as Scotland.[250]

The relationship between Yorkshire and Scottish devolution was again made in 1975 by Richard Wainwright, MP for Colne Valley, who claimed in a speech in the House of Commons:

The nationalist movement in Scotland is associated with flags, strange costumes, weird music and extravagant ceremonial. When... people go to Yorkshire and find that we have no time for dressing up, waving flags and playing strange instruments—in other words, we are not a lot of Presbyterians in Yorkshire—they should not assume that we do not have the same feelings underneath the skin. Independence in Yorkshire expresses itself in a markedly increasing determination to establish self-reliance.[251]

Following the local government reforms of 1974, Yorkshire lost its overall sheriff and the ridings lost their lieutenants and administrative counties. Although some government officials[252] and King Charles[253] have asserted such reform is not meant to alter the ancient boundaries or cultural loyalties, there are pressure groups such as the Yorkshire Ridings Society who want greater recognition for the historic boundaries.[254]

In 1998 the Campaign for Yorkshire was established to push for the creation of a Yorkshire regional assembly,[255] sometimes dubbed the Yorkshire Parliament.[256] In its defining statement, the Campaign for Yorkshire made reference to the historical notions that Yorkshire had a distinctive identity:

Yorkshire and the Humber has distinctive characteristics which make it an ideal test bed for further reform. It has a strong popular identity. The region follows closely the historic boundaries of the three Ridings, and there is no serious debate about boundaries. It possesses strong existing regional partnerships including universities, voluntary and church associations. All this makes it realistic to regard Yorkshire and the Humber as the standard bearer for representative regional government.[257]

The Campaign for Yorkshire was led by Jane Thomas as Director[258] and Paul Jagger as chairman. Jagger claimed in 1999 that Yorkshire had as much right to a regional parliament or assembly as Scotland and Wales because Yorkshire 'has as clear a sense of identity as Scotland or Wales.'[259] One of those brought into the Campaign for Yorkshire by Jane Thomas was Herbert Read scholar Michael Paraskos, who organised a series of events in 2000 to highlight the distinctiveness of Yorkshire culture. This included a major exhibition of Yorkshire artists.[260] Paraskos also founded a Yorkshire Studies degree course at Hull University.[261] Interviewed by The Guardian newspaper, Paraskos linked the start of this course to the contemporary devolution debates in Yorkshire, Scotland and Wales, claiming:

If Yorkshire is arguing for a parliament, there needs to be a cultural argument as well, otherwise why not have a parliament of the north? There is a rediscovery of political and social culture going on in a very similar way to the early assertions of a Scottish identity.[262]

In March 2013, the Yorkshire Devolution Movement was founded as an active campaign group by Nigel Sollitt, who had administered the social media group by that name since 2011, Gareth Shanks, a member of the social media group, and Stewart Arnold, former Chair of the Campaign for Yorkshire. In September 2013, the executive committee was joined by Richard Honnoraty and Richard Carter (as an advisor), who had also been involved in the Campaign for Yorkshire. The Movement campaigns for a directly elected parliament for the whole of the traditional county of Yorkshire with powers second to no other devolved administration in the UK.[263][264]