Human history

|

The history of the world[1][2][3] is the recorded memory of the experience, around the world, of Homo sapiens. Ancient human history[4] begins with the invention, independently at several sites on Earth, of writing, which created the infrastructure for lasting, accurately transmitted memories and thus for the diffusion and growth of knowledge.[5][6]

Human history is marked both by a gradual accretion of discoveries and inventions, as well as by quantum leaps—paradigm shifts, revolutions—that comprise epochs in the material and spiritual evolution of humankind.

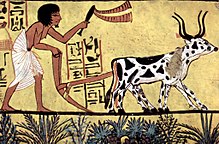

One such epoch was the advent of the Agricultural Revolution.[7][8] Between 8,500 and 7,000 BCE, in the Fertile Crescent, humans began the systematic husbandry of plants and animals — agriculture.[9] This spread to neighboring regions, and also developed independently elsewhere, until most Homo sapiens lived sedentary lives in permanent settlements as farmers.

Not all societies abandoned nomadism, especially those in isolated regions that were poor in domesticable plant species.[10] Those societies, however, that did abandon nomadism adopted settled life in scattered habitations centered about life-sustaining bodies of water — rivers and lakes. These communities coalesced over time into increasingly larger units, in parallel with the evolution of ever more efficient means of transport.

The relative security and increased productivity provided by farming allowed these communities to expand. Surplus food made possible an increasing division of labor, the rise of a leisured upper class, and the development of cities and thus of civilization. The growing complexity of human societies necessitated systems of accounting; and from this evolved, beginning in the Bronze Age, writing.[11] The independent invention of writing at several sites on Earth allows a number of regions to claim to be cradles of civilization.

Civilizations developed perforce on the banks of rivers. One of the first civilizations to arise, between 4,000 and 3,000 BCE, was Sumer, in the Middle East's "land between the rivers"—Mesopotamia.[12] Other civilizations soon developed on the banks of the Nile River in ancient Egypt,[13][14][15] at the Indus River valley,[16][17][18] and along the great rivers of China.

The history of the Old World is commonly divided into:

- Antiquity — in the Ancient Near East,[19][20][21] the Mediterranean basin of Classical Antiquity, Ancient China,[22] and Ancient India, up to about the 6th century;

- the Middle Ages,[23][24] from the 6th through the 15th centuries;

- the Early Modern period,[25] including the European Renaissance, from the 16th century to about 1750; and

- the Modern period, from the Age of Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, beginning about 1750, to the present.

In Europe, the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 CE) is commonly taken as signaling the end of antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages. A thousand years later, in the mid-15th century, Johannes Gutenberg's invention of modern printing,[26] employing movable type, revolutionized communication, helping end the Middle Ages and usher in modern times, the European Renaissance[27][28] and the Scientific Revolution.[29]

By the 18th century, the accumulation of knowledge and technology, especially in Europe, had reached a critical mass that sparked into existence the Industrial Revolution.[30] Over the quarter-millennium since, the growth of knowledge, technology, commerce, and — concomitantly with these — the potential destructiveness of war has accelerated geometrically (exponentially), creating the opportunities and perils that now confront the human communities that together inhabit the planet.[31][32]

Prehistory

Paleolithic

"Paleolithic" means "Old Stone Age." This was the earliest period of the Stone Age. The Lower Paleolithic is the period in human evolution when humans first began using stone tools. The Lower Paleolithic began 2.5 million years ago with the emergence of the genus homo. Homo habilis is the earliest known species in the genus Homo. The Middle Paleolithic originated 300,000 years ago. The period is characterized by Prepared-core techniques for manufacturing stone tools. The term Archaic homo sapiens is typically used to refer to the early hominids of the Middle Paleolithic. Anatomically modern humans also emerged during the Middle Paleolithic.[33][34]

Humans spread from East Africa to Asia some 100,000-50,000 years ago, and further to southern Asia and Australasia by at least 50 millennia ago, northwestwards into Europe and eastwards into Central Asia some 40 millennia ago, and further east to the Americas from ca. 13 millennia ago. The Upper Paleolithic is taken to begin some 40 millennia ago, with the appearance of wider variety of artifacts and a blossoming of symbolic culture.[35] Expansion to North America and Oceania took place at the climax of the most recent Ice Age, when today's temperate regions were extremely inhospitable. By the end of the Ice Age some 12,000 BP, humans had colonised nearly all the ice-free parts of the globe.

Throughout the Paleolithic, humans generally lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers. Hunter-gatherer societies have tended to be very small and egalitarian, though hunter-gatherer societies with abundant resources or advanced food-storage techniques have sometimes developed a sedentary lifestyle, complex social structures such as chiefdoms, and social stratification; and long-distance contacts may be possible, as in the case of Indigenous Australian "highways."

Mesolithic

The "Mesolithic," or "Middle Stone Age" (from the Greek "mesos," "middle," and "lithos," "stone") was a period in the development of human technology between the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods of the Stone Age.[36]

The Mesolithic period began at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, some 10,000 BP, and ended with the introduction of agriculture, the date of which varied by geographic region. In some areas, such as the Near East, agriculture was already underway by the end of the Pleistocene, and there the Mesolithic is short and poorly defined. In areas with limited glacial impact, the term "Epipaleolithic" is sometimes preferred.

Regions that experienced greater environmental effects as the last ice age ended have a much more evident Mesolithic era, lasting millennia.[37] In Northern Europe, societies were able to live well on rich food supplies from the marshlands fostered by the warmer climate. Such conditions produced distinctive human behaviours which are preserved in the material record, such as the Maglemosian and Azilian cultures. These conditions also delayed the coming of the Neolithic until as late as 4000 BCE (6,000 BP) in northern Europe.

Remains from this period are few and far between, often limited to middens. In forested areas, the first signs of deforestation have been found, although this would only begin in earnest during the Neolithic, when more space was needed for agriculture.

The Mesolithic is characterized in most areas by small composite flint tools — microliths and microburins. Fishing tackle, stone adzes and wooden objects, e.g. canoes and bows, have been found at some sites. These technologies first occur in Africa, associated with the Azilian cultures, before spreading to Europe through the Ibero-Maurusian culture of Spain and Portugal, and the Kebaran culture of Palestine. Independent discovery is not always ruled out.

During the Mesolithic as in the preceding Paleolithic period, people lived in small (mostly egalitarian) bands and tribes.

Neolithic

"Neolithic" means "New Stone Age." This was a period of primitive technological and social development, toward the end of the "Stone Age." Beginning in the 10th millennium BCE (12,000 BP), the Neolithic period saw the development of early villages, agriculture, animal domestication and tools.[38][39]

Rise of agriculture

A major change, described by prehistorian Vere Gordon Childe as the "Agricultural Revolution," occurred about the 10th millennium BCE with the adoption of agriculture. The Sumerians first began farming ca. 9500 BCE. By 7000 BCE, agriculture had spread to India; by 6000 BCE, to Egypt; by 5000 BCE, to China. About 2700 BCE, agriculture had come to Mesoamerica.[40]

Although attention has tended to concentrate on the Middle East's Fertile Crescent, archaeology in the Americas, East Asia and Southeast Asia indicates that agricultural systems, using different crops and animals, may in some cases have developed there nearly as early. The development of organised irrigation, and the use of a specialised workforce, by the Sumerians, began about 5500 BCE. Stone was supplanted by bronze and iron in implements of agriculture and warfare. Agricultural settlements had until then been almost completely dependent on stone tools. In Eurasia, copper and bronze tools, decorations and weapons began to be commonplace about 3000 BCE. After bronze, the Eastern Mediterranean region, Middle East and China saw the introduction of iron tools and weapons.

The Americas may not have had metal tools until the Chavín horizon (900 BCE). The Moche did have metal armor, knives and tableware. Even the metal-poor Inca had metal-tipped plows, at least after the conquest of Chimor. However, little archaeological research has so far been done in Peru, and nearly all the khipus (recording devices, in the form of knots, used by the Incas) were burned in the Spanish conquest of Peru. As late as 2004, entire cities were still being unearthed. Some digs suggest that steel may have been produced there before it was developed in Europe.

The cradles of early civilizations were river valleys, such as the Euphrates and Tigris valleys in Mesopotamia, the Nile valley in Egypt, the Indus valley in the Indian subcontinent, and the Yangtze and Yellow River valleys in China. Some nomadic peoples, such as the Indigenous Australians and the Bushmen of southern Africa, did not practice agriculture until relatively recent times.[41][42][43]

Before 1800, many populations did not belong to states. Scientists disagree as to whether the term "tribe"[44] should be applied to the kinds of societies that these people lived in. Many tribal societies, in Europe and elsewhere, transformed into states when they were threatened, or otherwise impinged on, by existing states. Examples are the Marcomanni, Poland and Lithuania. Some "tribes," such as the Kassites and the Manchus, conquered states and were absorbed by them.

Agriculture made possible complex societies — civilizations. States and markets emerged. Technologies enhanced people's ability to control nature and to develop transport and communication.

Rise of religion

It is to the Neolithic that most historians trace the beginnings of complex religion.[45][46][47] Religious belief in this period commonly consisted in the worship of a Mother Goddess, a Sky Father, and of the Sun and Moon as deities. (see also Sun worship). Shrines developed, which over time evolved into temple establishments, complete with a complex hierarchy of priests and priestesses and other functionaries. Typical of the Neolithic was a tendency to worship anthropomorphic deities. The earliest surviving religious scriptures are the Pyramid Texts, produced by the Egyptians (dating back to 3100 B.C.E).

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age forms part of the three-age system. In this system, it follows the Neolithic in some areas of the world. In the 24th century BCE, Akkadian Empire[48][49] In the 22nd century BCE, the First Intermediate Period of Egypt occurred The time between the 21st to 17th centuries BCE around the Nile has been denoted as Middle Kingdom of Egypt. In the 21st century BCE, the Sumerian Renaissance occurs. By the 18th century, the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt begins.

By 1600 BCE, Mycenaean Greece begins to develop.[50][51] Also by 1600 BCE, the beginning of Shang Dynasty in China emerges and there is evidence of a fully developed Chinese writing system. Around 1600 BCE, the beginning of Hittite dominance of the Eastern Mediterranean region is seen. The time between the 16th to 11th centuries around the Nile is call the New Kingdom of Egypt.[52][53] Between 1550 BCE and 1292 BCE, the Amarna period occurs.

Early civilization

The first Agricultural Revolution led to several major changes. It permitted far denser populations, which in time organised into states. There are several definitions for the term, "state." Max Weber and Norbert Elias defined a state as an organization of people that has a monopoly on the legitimate use of force in a particular geographic area.

In Bronze Age Mesopotamia and Iran, there were several city-states. States appeared in Mesopotamia, western Iran, and Indus Valley. Ancient Egypt began as a state without cities, but soon developed them. States appeared in China in the late 3rd and early 2nd millennia BCE.

A state ordinarily needs an army for the legitimate exercise of force. An army needs a bureaucracy to maintain it. The only exception to this appears to have been the Indus Valley civilization, for which there is no evidence of the existence of a military force.

Major wars were waged among states in the Middle East. About 1275 BCE, the Hittites under Muwatalli II and the Egyptians under Ramesses II concluded the treaty of Kadesh, the world's oldest recorded peace treaty.[54]

Empires came into being, with conquered areas ruled by central tribes, as in the Neo-Assyrian Empire (10th century BCE), the Achaemenid Persian Empire (6th century BCE), the Mauryan Empire (4th century BCE), Qin and Han China (3rd century BCE), and the Roman Empire (1st century BCE).

Clashes among empires included those that took place in the 8th century, when the Islamic Caliphate of Arabia (ruling from Spain to Iran) and China's Tang dynasty (ruling from Xinjiang to Dalian) fought for decades for control of Central Asia.

The largest contiguous land empire in history was the 13th-century Mongolian Empire.[55][56] By then, most people in Europe, Asia and North Africa belonged to states. There were states as well in Mexico and western South America. States controlled more and more of the world's territory and population; the last "empty" territories, with the exception of uninhabited Antarctica, would be divided up among states by the Berlin Conference (1884-1885).

City and trade

Agriculture also created, and allowed for the storage of, food surpluses that could support people not directly engaged in food production. The development of agriculture permitted the creation of the first cities. These were centers of trade, manufacture and political power with nearly no agricultural production of their own. Cities established a symbiosis with their surrounding countrysides, absorbing agricultural products and providing, in return, manufactures and varying degrees of military protection.[57][58][59]

The development of cities equated, both etymologically and in fact, with the rise of civilization itself: first Sumerian civilization, in lower Mesopotamia (3500 BCE),[60][61] followed by Egyptian civilization along the Nile (3300 BCE)[62] and Harappan civilization in the Indus Valley (3300 BCE).[63][64] Elaborate cities grew up, with high levels of social and economic complexity. Each of these civilizations was so different from the others that they almost certainly originated independently. It was at this time, and due to the needs of cities, that writing and extensive trade were introduced.

The earliest known form of writing was cuneiform script, created by the Sumerians from ca. 3000 BCE. Cuneiform writing began as a system of pictographs. Over time, the pictorial representations became simplified and more abstract. Cuneiforms were written on clay tablets, on which symbols were drawn with a blunt reed for a stylus. The first alphabets were used in the Middle Bronze Age (2000-1500 BCE). From them evolved the Phoenician alphabet, used for the writing of Phoenician. The Phoenician alphabet is the ancestor of many of the writing systems used today.

In China, proto-urban societies may have developed from 2500 BCE, but the first dynasty to be identified by archeology is the Shang Dynasty.

The 2nd millennium BCE saw the emergence of civilization in Canaan, Crete, mainland Greece, and central Turkey.

In the Americas, civilizations such as the Maya, Zapotec, Moche, and Nazca emerged in Mesoamerica and Peru at the end of the 1st millennium BCE.

The world's first coinage was introduced around 625 BCE in Lydia (western Anatolia, in modern Turkey).[65]

Trade routes appeared in the eastern Mediterranean in the 4th millennium BCE. Long-range trade routes first appeared in the 3rd millennium BCE, when Sumerians in Mesopotamia traded with the Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley. The Silk Road between China and Syria began in the 2nd millennium BCE. Cities in Central Asia and Persia were major crossroads of these trade routes. Silla dynastic tombs have been found in Korea, containing relics such as wine cups produced in Iran.[66] The Phoenician and Greek civilizations founded trade-based empires in the Mediterranean basin in the 1st millennium BCE.

In the late 1st millennium CE and early 2nd millennium CE, the Arabs dominated the trade routes in the Indian Ocean, East Asia, and the Sahara. In the late 1st millennium, Arabs and Jews dominated trade in the Mediterranean. In the early 2nd millennium, Italians took over this role, and Flemish and German cities were at the center of trade routes in northern Europe controlled by the Hanseatic League.[67] In all areas, major cities developed at crossroads along trade routes.

Ancient history

Historiography proper emerges in antiquity — Chinese historiography, in the 6th century BCE with the Classic of History and the Spring and Autumn Annals; and Greek historiography, in the 5th century BCE with Herodotus. Earlier historical records, however, allow the piecing together of at least sketchy histories of the states of the Ancient Near East from as early as the 3rd millennium BCE.

Religion and philosophy

New philosophies[68] and religions[69] arose in both east and west, particularly about the 6th century BCE. Over time, a great variety of religions developed around the world, with some of the earliest major ones being Hinduism,[70] Buddhism,[71] and Jainism in India,[72] and Zoroastrianism[73] in Persia. The Abrahamic religions[74] trace their origin to Judaism, around 1800 BCE.

In the east, three schools of thought were to dominate Chinese thinking until the modern day. These were Taoism,[75] Legalism[76] and Confucianism.[77] The Confucian tradition, which would attain dominance, looked for political morality not to the force of law but to the power and example of tradition. Confucianism would later spread into the Korean peninsula and Goguryeo[78] and toward Japan.

In the west, the Greek philosophical tradition, represented by Socrates,[79] Plato,[80] and Aristotle,[81][82] was diffused throughout Europe and the Middle East in the 4th century BCE by the conquests of Alexander III of Macedon, more commonly known as Alexander the Great.[83][84][85]

Civilizations and regions

By the last centuries BCE, the Mediterranean, the Ganges River and the Yellow River had become seats of empires which future rulers would seek to emulate. In India, the Mauryan Empire[86][87] ruled most of southern Asia, while the Pandyas ruled southern India. In China, the Qin and Han dynasties extended their imperial governance through political unity, improved communications and Emperor Wu's establishment of state monopolies.

In the west, the ancient Greeks established a civilization that is considered by most historians to be the foundational culture of modern western civilization. Some centuries later, in the 3rd century BCE, the Romans began expanding their territory through conquest and colonisation. By the reign of Emperor Augustus (late 1st century BCE), Rome controlled all the lands surrounding the Mediterranean. By the reign of Emperor Trajan (early 2nd century CE), Rome controlled much of the land from England to Mesopotamia.

The great empires depended on military annexation of territory and on the formation of defended settlements to become agricultural centres.[88] The relative peace that the empires brought, encouraged international trade, most notably the massive trade routes in the Mediterranean that had been developed by the time of the Hellenistic Age, and the Silk Road.

The empires faced common problems associated with maintaining huge armies and supporting a central bureaucracy. These costs fell most heavily on the peasantry, while land-owning magnates were increasingly able to evade centralised control and its costs. The pressure of barbarians on the frontiers hastened the process of internal dissolution. China's Han Empire fell into civil war in 220 CE, while its Roman counterpart became increasingly decentralised and divided about the same time.

Throughout the temperate zones of Eurasia, America and North Africa, empires continued to rise and fall.

The gradual break-up of the Roman Empire,[89][90] spanning several centuries after the 2nd century CE, coincided with the spread of Christianity westward from the Middle East. The western Roman Empire fell[91] under the domination of Germanic tribes in the 5th century, and these polities gradually developed into a number of warring states, all associated in one way or another with the Roman Catholic Church. The remaining part of the Roman Empire, in the eastern Mediterranean, would henceforth be the Byzantine Empire.[92] Centuries later, a limited unity would be restored to western Europe through the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire[93] in 962, which comprised a number of states in what is now Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Italy, and France.

In China, dynasties would similarly rise and fall.[94][95] After the fall of the Eastern Han Dynasty[96] and the demise of the Three Kingdoms, Nomadic tribes from the north began to invade in the 4th century CE, eventually conquering areas of Northern China and setting up many small kingdoms. The Sui Dynasty reunified China in 581, and under the succeeding Tang Dynasty (618-907) China entered a second golden age. The Tang Dynasty also splintered, however, and after half a century of turmoil the Northern Song Dynasty reunified China in 982. Yet pressure from nomadic empires to the north became increasingly urgent. North China was lost to the Jurchens in 1141, and the Mongol Empire[97][98] conquered all of China in 1279, as well as almost all of Eurasia's landmass, missing only central and western Europe, and most of Southeast Asia and Japan.

In these times, northern India was ruled by the Guptas. In southern India, three prominent Dravidian kingdoms emerged: Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas. The ensuing stability contributed to heralding in the golden age of Hindu culture in the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

At this time also, in Central America,[99] vast societies also began to be built, the most notable being the Maya and Aztecs of Mesoamerica. As the mother culture of the Olmecs[100] gradually declined, the great Mayan city-states slowly rose in number and prominence, and Maya culture spread throughout Yucatán and surrounding areas. The later empire of the Aztecs was built on neighboring cultures and was influenced by conquered peoples such as the Toltecs.

In South America, the 14th and 15th centuries saw the rise of the Inca. The Inca Empire of Tawantinsuyu, with its capital at Cusco, spanned the entire Andes Mountain Range.[101][102] The Inca were prosperous and advanced, known for an excellent road system and unrivaled masonry.

Islam,[103] which began in 7th century Arabia, was also one of the most remarkable forces in world history, growing from a handful of adherents to become the foundation of a series of empires in the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, India and present-day Indonesia.

In northeastern Africa, Nubia and Ethiopia remained Christian enclaves while the rest of Africa north of the equator converted to Islam. With Islam came new technologies that, for the first time, allowed substantial trade to cross the Sahara. Taxes on this trade brought prosperity to North Africa, and the rise of a series of kingdoms in the Sahel.

This period in the history of the world was marked by slow but steady technological advances, with important developments such as the stirrup and moldboard plow arriving every few centuries. There were, however, in some regions, periods of rapid technological progress. Most important, perhaps, was the Mediterranean area during the Hellenistic period, when hundreds of technologies were invented.[104][105][106] Such periods were followed by periods of technological decay, as during the Roman Empire's decline and fall and the ensuing early medieval period.

The Plague of Justinian[107] was a pandemic that afflicted the Byzantine Empire, including its capital Constantinople, in the years 541–542 AD. It is estimated that the Plague of Justinian killed as many as 100 million people across the world.[108][109] It caused Europe's population to drop by around 50% between 541 and 700.[110] It also may have contributed to the success of the Arab conquests.[111][112]

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages are commonly dated from the fall of the Western Roman Empire (or by some scholars,[who?] before that) in the 5th century to the beginning of the Early Modern Period[113] in the 16th century, marked by the rise of nation-states, the division of Western Christianity in the Reformation,[114] the rise of humanism in the Italian Renaissance,[115] and the beginnings of European overseas expansion which allowed for the Columbian Exchange.[116]

The period corresponds to the Islamic conquests[117] and the Islamic golden age,[118][119] followed by the Mongol invasions in the Middle East and Central Asia. South Asia sees a series of "Middle kingdoms" followed by the establishment of Islamic empires. The Chinese Empire sees the succession of the Sui, Tang, Liao, Yuan and Ming Dynasties.

The Middle Ages[120] witnessed the first sustained urbanization of northern and western Europe. Many modern European states owe their origins to events unfolding in the Middle Ages; present European political boundaries are, in many regards, the result of the military and dynastic achievements during this tumultuous period.[121]

Early Modern period

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

The early modern period[122] is a term used by historians to refer to the period in Western Europe and its first colonies which spans the three centuries between the Middle Ages and the Industrial Revolution. The early modern period is characterized by the rise to importance of science and increasingly rapid technological progress, secularized civic politics and the nation state. Capitalist economies began their rise, beginning in northern Italian republics such as Genoa. The early modern period also saw the rise and dominance of the economic theory of mercantilism. As such, the early modern period represents the decline and eventual disappearance, in much of the European sphere, of feudalism, serfdom and the power of the Catholic Church. The period includes the Protestant Reformation, the disastrous Thirty Years' War, the European colonization of the Americas and the peak of the European witch-hunt phenomenon.

Rise of Europe

Nearly all the agricultural civilizations were heavily constrained by their environments. Productivity remained low, and climatic changes easily instigated boom and bust cycles that brought about civilizations' rise and fall. By about 1500, however, there was a qualitative change in world history. Technological advance and the wealth generated by trade gradually brought about a widening of possibilities.[123][124][125][126][127][128][129][130][131][132][133]

Even before the 16th century, some civilizations had developed advanced societies.[134] In ancient times, the Greeks and Romans had produced societies supported by a developed monetary economy, with financial markets and private-property rights. These institutions created the conditions for continuous capital accumulation, with increased productivity. By some estimates, the per-capita income of Roman Italy, one of the most advanced regions of the Roman Empire, was comparable to the per-capita incomes of the most advanced economies in the 18th century.[135] The most developed regions of classical civilization were more urbanized than any other region of the world until early modern times. This civilization had, however, gradually declined and collapsed; historians still debate the causes.

China had developed an advanced monetary economy by 1,000 CE. China had a free peasantry who were no longer subsistence farmers, and could sell their produce and actively participate in the market. The agriculture was highly productive and China's society was highly urbanized. The country was technologically advanced as it enjoyed a monopoly in piston bellows and printing. (see Joseph Needham). But, after earlier onslaughts by the Jurchens, in 1279 the remnants of the Sung empire were conquered by the Mongols.

Outwardly, Europe's Renaissance, beginning in the 14th century,[136] consisted in the rediscovery of the classical world's scientific contributions, and in the economic and social rise of Europe. But the Renaissance also engendered a culture of inquisitiveness which ultimately led to Humanism,[137] the Scientific Revolution,[138] and finally the great transformation of the Industrial Revolution. The Scientific Revolution in the 17th century, however, had no immediate impact on technology; only in the second half of the 18th century did scientific advances begin to be applied to practical invention.

The advantages that Europe had developed by the mid-18th century were two: an entrepreneurial culture,[139] and the wealth generated by the Atlantic trade (including the African slave trade). By the late 16th century, American silver accounted for one-fifth of Spain's total budget.[140] The profits of the slave trade and of West Indian plantations amounted to 5% of the British economy at the time of the Industrial Revolution.[141] While some historians conclude that, in 1750, labour productivity in the most developed regions of China was still on a par with that of Europe's Atlantic economy (see Wolfgang Keller and Carol Shiue), other historians like Angus Maddison hold that the per-capita productivity of western Europe had by the late Middle Ages surpassed that of all other regions.[142]

A number of explanations are proffered as to why, from the late Middle Ages on, Europe rose to surpass other civilizations, become the home of the Industrial Revolution,[143] and dominate the world. Max Weber argued that it was due to a Protestant work ethic that encouraged Europeans to work harder and longer than others. Another socioeconomic explanation looks to demographics: Europe, with its celibate clergy, colonial emigration, high-mortality urban centers, periodic famines and outbreaks of the Black Death, continual warfare, and late age of marriage had far more restrained population growth, compared to Asian cultures. A relative shortage of labour meant that surpluses could be invested in labour-saving technological advances such as water-wheels and mills, spinners and looms, steam engines and shipping, rather than fueling population growth.

Many have also argued that Europe's institutions were superior,[144][145] that property rights and free-market economics were stronger than elsewhere due to an ideal of freedom peculiar to Europe. In recent years, however, scholars such as Kenneth Pomeranz have challenged this view, although the revisionist approach to world history has also met with criticism for systematically "downplaying" European achievements.[146]

Europe's geography may also have played an important role. The Middle East, India and China are all ringed by mountains but, once past these outer barriers, are relatively flat. By contrast, the Pyrenees, Alps, Apennines, Carpathians and other mountain ranges run through Europe, and the continent is also divided by several seas. This gave Europe some degree of protection from the peril of Central Asian invaders. Before the era of firearms, these nomads were militarily superior to the agricultural states on the periphery of the Eurasian continent and, if they broke out into the plains of northern India or the valleys of China, were all but unstoppable. These invasions were often devastating. The Golden Age of Islam[147] was ended by the Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258. India and China were subject to periodic invasions, and Russia spent a couple of centuries under the Mongol-Tatar Yoke. Central and western Europe, logistically more distant from the Central Asian heartland, proved less vulnerable to these threats.

Geography also contributed to important geopolitical differences. For most of their histories, China, India and the Middle East were each unified under a single dominant power that expanded until it reached the surrounding mountains and deserts. In 1600 the Ottoman Empire[148] controlled almost all the Middle East, the Ming Dynasty ruled China,[149][150] and the Mughal Empire held sway over India. By contrast, Europe was almost always divided into a number of warring states. Pan-European empires, with the major exception of the Roman Empire, tended to collapse soon after they arose.

One source of Europe's success is often said to be the intense competition among rival European states. In other regions, stability was often a higher priority than growth. China's growth as a maritime power was halted by the Ming Dynasty's Hai jin ban on ocean-going commerce. In Europe, due to political disunity, a blanket ban of this kind would have been impossible; had any one state imposed it, that state would quickly have fallen behind its competitors.

Another doubtless important geographic factor in the rise of Europe was the Mediterranean Sea, which, for millennia, had functioned as a maritime superhighway fostering the exchange of goods, people, ideas and inventions.

By contrast to Europe, in tropical lands the still more ubiquitous diseases and parasites, sapping the strength and health of humans, and of their animals and crops, were socially-disorganizing factors that impeded progress. [10]

Age of Discovery

In the fourteenth century, the Renaissance began in Europe. Some modern scholars have questioned whether this flowering of art and Humanism was a benefit to science, but the era did see an important fusion of Arab and European knowledge. One of the most important developments was the caravel, which combined the Arab lateen sail with European square rigging to create the first vessels that could safely sail the Atlantic Ocean. Along with important developments in navigation, this technology allowed Christopher Columbus in 1492 to journey across the Atlantic Ocean and bridge the gap between Afro-Eurasia and the Americas.

This had dramatic effects on both continents. The Europeans brought with them viral diseases that American natives had never encountered, and uncertain numbers of natives died in a series of devastating epidemics. The Europeans also had the technological advantage of horses, steel and guns that helped them overpower the Aztec and Incan empires as well as North American cultures.

Gold and resources from the Americas began to be stripped from the land and people and shipped to Europe, while at the same time large numbers of European colonists began to emigrate to the Americas. To meet the great demand for labor in the new colonies, the mass import of Africans as slaves began. Soon much of the Americas had a large racial underclass of slaves. In West Africa, a series of thriving states developed along the coast, becoming prosperous from the exploitation of suffering interior African peoples.

Europe's maritime expansion unsurprisingly — given that continent's geography — was largely the work of its Atlantic seaboard states: Portugal, Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands. The Portuguese and Spanish Empires were at first the predominant conquerors and source of influence, but soon the more northern English, French and Dutch began to dominate the Atlantic. In a series of wars fought in the 17th and 18th centuries, culminating with the Napoleonic Wars, Britain emerged as the first world power. It accumulated an empire that spanned the globe, controlling, at its peak, approximately one-quarter of the world's land surface, on which the "sun never set".

Meanwhile the voyages of Admiral Zheng He were halted by China's Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), established after the expulsion of the Mongols. A Chinese commercial revolution, sometimes described as "incipient capitalism," was also abortive. The Ming Dynasty would eventually fall to the Manchus, whose Qing Dynasty at first oversaw a period of calm and prosperity but would increasingly fall prey to Western encroachment.

19th Century

Soon after the expansion into the Americas, Europeans had exerted their technological advantage as well over the peoples of Asia. In the early 19th century, Britain gained control of the Indian subcontinent, Egypt and the Malay Peninsula; the French took Indochina; while the Dutch occupied the Dutch East Indies. The British also took over several areas still populated by Neolithic peoples, including Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, and, as in the Americas, large numbers of British colonists began to emigrate there. In the late 19th century, the European powers divided the remaining areas of Africa.

This era in Europe saw the Age of Reason lead to the Scientific Revolution, which changed man's understanding of the world and made possible the Industrial Revolution, a major transformation of the world’s economies. The Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain and used new modes of production — the factory, mass production, and mechanisation — to manufacture a wide array of goods faster and for less labour than previously.

The Age of Reason also led to the beginnings of modern democracy in the late-18th century American and French Revolutions. Democracy would grow to have a profound effect on world events and on quality of life.

During the Industrial Revolution, the world economy was soon based on coal, as new methods of transport, such as railways and steamships, effectively shrank the world. Meanwhile, industrial pollution and environmental damage, present since the discovery of fire and the beginning of civilization, accelerated drastically.

20th century to present

Early 20th century

The 20th century[151][152][153] opened with Europe at an apex of wealth and power, and with much of the world under its direct colonial control or its indirect domination.[154] Much of the rest of the world was influenced by heavily Europeanized nations: the United States and Japan.[155] As the century unfolded, however, the global system dominated by rival powers was subjected to severe strains, and ultimately yielded to a more fluid structure of independent nations organized on Western models.

This transformation was catalyzed by wars of unparalleled scope and devastation. World War I[156] destroyed many of Europe's empires and monarchies, and weakened France and Britain.[157] In its aftermath, powerful ideologies arose. The Russian Revolution[158][159][160] of 1917 created the first communist state, while the 1920s and 1930s saw militaristic fascist dictatorships gain control in Italy, Germany, Spain and elsewhere.[161]

Ongoing national rivalries, exacerbated by the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, helped precipitate World War II.[162][163] The militaristic dictatorships of Europe and Japan pursued an ultimately doomed course of imperialist expansionism. Their defeat opened the way for the advance of communism into Central Europe, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, China, North Vietnam and North Korea.

Following World War II, in 1945, the United Nations was founded in the hope of allaying conflicts among nations and preventing future wars.[164][165] The war had, however, left two nations, the United States[166] and the Soviet Union, with principal power to guide international affairs.[167] Each was suspicious of the other and feared a global spread of the other's political-economic model. This led to the Cold War, a forty-year stand-off between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies. With the development of nuclear weapons[168] and the subsequent arms race, all of humanity were put at risk of nuclear war between the two superpowers.[169] Such war being viewed as impractical, proxy wars were instead waged, at the expense of non-nuclear-armed Third World countries.

Late 20th Cenutry

The Cold War lasted through the ninth decade of the twentieth century, when the Soviet Union's communist system began to collapse, unable to compete economically with the United States and western Europe; the Soviets' Central European "satellites" reasserted their national sovereignty, and in 1991 the Soviet Union itself disintegrated.[170][171][172] The United States for the time being was left as the "sole remaining superpower".[173][174][175]

In the early postwar decades, the African and Asian colonies of the Belgian, British, Dutch, French and other west European empires won their formal independence but faced challenges in the form of neocolonialism, poverty, illiteracy and endemic tropical diseases. Many of the Western and Central European nations gradually formed a political and economic community, the European Union, which subsequently expanded eastward to include former Soviet satellites.[176][177][178][179]

The twentieth century saw exponential progress in science and technology, and increased life expectancy and standard of living for much of humanity. As the developed world shifted from a coal-based to a petroleum-based economy, new transport technologies, along with the dawn of the Information Age,[180] led to increased globalization.[181][182][183] Space exploration reached throughout the solar system. The structure of DNA, the very template of life, was discovered,[184][185][186] and the human genome was sequenced, a major milestone in the understanding of human biology and the treatment of disease.[187][188][189][190][191] Global literacy rates continued to rise, and the percentage of the world's labor pool needed to produce humankind's food supply continued to drop.

The century saw the development of new global threats, such as nuclear proliferation, worldwide epidemics of diseases, global climate change,[192][193] massive deforestation, and the dwindling of global resources.[194] It witnessed, as well, a dawning awareness of ancient hazards that had probably previously caused mass extinctions of lifeforms on the planet, such as near-earth asteroids and comets, supervolcano eruptions, and gamma-ray bursts.

21st century

As the 20th century yielded to the 21st, worldwide demand and competition for resources rose due to growing populations and industrialization, with resulting increased levels of environmental degradation.[195] A matter of particular urgency was the development of more plentiful and safer sources of energy such as solar and other renewable energy varieties, and perhaps expanded use of nuclear energy and of "clean" fossil-fuel technologies.[196][197][198][199]

Older industrial regions competed with rapidly-industrializing economies, including those of China and India, for the world's resources, including petroleum. Smaller polities, too, made their contributions to global competition and strife. The life courses of many states continued to be accompanied by wars, with resulting loss of life, economic devastation, disease, famine and genocide. As of 2008, some 30 ongoing armed conflicts raged in various parts of the world.[200]

Lessons

Ever since the invention of history, people have searched for "lessons" that might be drawn from its study, on the principle that to understand the past is potentially to control the future.[201] Arnold J. Toynbee, in his monumental Study of History, sought regularities in the rise and fall of civilizations.[202] In a more popular vein, Will and Ariel Durant devoted a 1968 book, The Lessons of History, to a discussion of "events and comments that might illuminate present affairs, future possibilities... and the conduct of states."[203]

Discussions of history's lessons often tend to an excessive focus on historic detail or, conversely, on sweeping historiographic generalizations.[204] Yet some conclusions may be profitably drawn from the study of history. Some of these lie embedded in foregoing parts of this article and relate to the physical requisites for the sustenance and development of human communities—to soil, water, climate, geography, and biogenic and mineral resources—as well as to mankind's accumulation of discoveries and inventions, including the Agricultural Revolution, literacy and the Industrial Revolution.

It may be emblematic of history's traditional concerns that what is regarded as the first work of history in Western literature, Herodotus's The Histories written about 440 BCE, tells the story of the Greco-Persian Wars in the 5th century BCE.[205] For much of what has been regarded until recently as human history is indeed the story of gradual, ongoing nation-building and -maintenance via internal struggles for dominance and external struggles to defend one's polity against other polities.[206]

Another notable phenomenon is the recurrence of the concept of "exceptionalism," whereby successive civilizations, imperfectly aware of their predecessors in history's archeological layering, tend to see their own ascendance as an exceptional event in history—perhaps the final event. Yet if history demonstrates anything, it is that history stands still for no community—that there are no final events. This has been expressed nowhere so poetically as in the following 1807 quotation from British author William Playfair, and known as the "Playfair cycle":

:...wealth and power have never been long permanent in any place.

- ...they travel over the face of the earth,

- something like a caravan of merchants.

- On their arrival, every thing is found green and fresh;

- while they remain all is bustle and abundance,

- and, when gone, all is left trampled down, barren, and bare.[207]

See also

History topics

- Medieval demography

- History of science

- History of technology

- Technological singularity

- Historiography

- Development criticism

- Deluge (mythology)

History by period

History by region

- History of Africa

- History of the Americas: History of North America, History of Central America, History of the Caribbean, History of South America

- History of Antarctica

- History of Asia: History of East Asia, History of the Middle East, History of South Asia, History of Southeast Asia

- History of Australia

- History of Europe

- History of New Zealand

- History of the Pacific Islands

Notes

- ^ Williams, H. S. (1904). The historians' history of the world; a comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of all ages. New York: The Outlook Company; [etc.,etc.].

- ^ Blainey, Geoffery (2000). A Short History Of The World. Penguin Books, Victoria. ISBN 0-670-88036-1

- ^ Gombrich, Ernst H. A Little History of the World. Yale. UK and USA, 2005.

- ^ Crawford, O. G. S. (1927). Antiquity. [Gloucester, Eng.]: Antiquity Publications [etc.]. (cf., History education in the United States is primarily the study of the written past. Defining history in such a narrow way has important consequences ...)

- ^ According to David Diringer ("Writing," Encyclopedia Americana, 1986 ed., vol. 29, p. 558), "Writing gives permanence to men's knowledge and enables them to communicate over great distances.... The complex society of a higher civilization would be impossible without the art of writing."

- ^ Webster, H. (1921). World history. Boston: D.C. Heath. Page 27.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter. (2004). First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20566-7

- ^ Cohen, Mark Nathan (1977)The Food Crisis in Prehistory: Overpopulation and the Origins of Agriculture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02016-3.

- ^ Tudge, Colin (1998). Neanderthals, Bandits and Farmers: How Agriculture Really Began. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84258-7.

- ^ a b Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31755-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Schmandt-Besserat, Denise (Jan–Feb 2002). "Signs of Life" (PDF). Archaeology Odyssey: 6–7, 63.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ McNeill, Willam H. (1999) [1967]. "In The Beginning". A World History (4th ed. ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-19-511615-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Baines, John and Jaromir Malek (2000). The Cultural Atlas of Ancient Egypt (revised edition ed.). Facts on File. ISBN 0816040362.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Bard, KA (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. NY, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Books. ISBN 0631193960.

- ^ Allchin, Raymond (ed.) (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. New York: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Chakrabarti, D. K. (2004). Indus Civilization Sites in India: New Discoveries. Mumbai: Marg Publications. ISBN 81-85026-63-7.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hassan (1996). History of Humanity, Volume III, From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century BC. New York/Paris: Routledge/UNESCO. ISBN 0415093066.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ William W. Hallo & William Kelly Simpson, The Ancient Near East: A History, Holt Rinehart and Winston Publishers, 1997

- ^ Jack Sasson, The Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, New York, 1995

- ^ Marc Van de Mieroop, History of the Ancient Near East: Ca. 3000-323 B.C., Blackwell Publishers, 2003

- ^ Ancient Asian World

- ^ Internet Medieval Sourcebook Project

- ^ The Online Reference Book of Medieval Studies

- ^ Rice, Eugene, F., Jr. (1970). The Foundations of Early Modern Europe: 1460-1559. W.W. Norton & Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "What Did Gutenberg Invent?". BBC. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Burckhardt, Jacob (1878), The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans S.G.C Middlemore, republished in 1990 ISBN 0-14-044534-X

- ^ The Cambridge Modern History. Vol 1: The Renaissance (1902)

- ^ Grant, Edward. The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1996.

- ^ More; Charles. Understanding the Industrial Revolution (2000) online edition

- ^ Reuters - The State of the World The story of the 21st century

- ^ Scientific American Magazine (September 2005 Issue) The Climax of Humanity

- ^ Middle and Upper Paleolithic Hunter-Gatherers The Emergence of Modern Humans, The Mesolithic

- ^ Map of Earth during the late Upper Paleolithic By Christopher scotese

- ^ The Upper Paleolithic Revolution

- ^ Mithen, S. J. (2004). After the ice: a global human history, 20,000-5000 BC. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Pielou, E.C., 1991. After the Ice Age : The Return of Life to Glaciated North America. University Of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. ISBN 0-226-66812-6 (paperback 1992)

- ^ Bellwood, Peter. (2004). First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20566-7

- ^ McNamara, John (2005). "Neolithic Period" (html). World Museum of Man. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ^ Marcel Mazoyer, Laurence Roudart, A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2006, ISBN 1583671218

- ^ Oliphant, Margaret (1992). The Atlas of the Ancient World: Charting the Great Civilizations of the Past. London: Ebury. ISBN 0-09-177040-8.

- ^ Brinton, Crane ; et al. (1984). A History of Civilization: Prehistory to 1715 (6th ed. ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-389866-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Chisholm, Jane (1991). Early Civilization. illus. Ian Jackson. London: Usborne. ISBN 1-58086-022-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Basic dynamics of classic tribes

- ^ The Sun God Ra and Ancient Egypt

- ^ The Sun God and the Wind Deity at Kizil by Tianshu Zhu, in Transoxiana Eran ud Aneran, Webfestschrift Marshak 2003.

- ^ Marija Gimbutas. The language of the Goddess. Harpercollins (1989). ISBN 0062503561

- ^ akkadian, angelfire.com

- ^ Wells, H. G. (1921). The outline of history, being a plain history of life and mankind. New York: Macmillan company. Page 137.

- ^ Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-29037-6.

- ^ Mylonas, George E. (1966). Mycenae and the Mycenaean Age. Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-03523-7.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Books.

- ^ Kemp, Barry (1991). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization. Routledge.

- ^ "Ramses/Hattusili Treaty".

- ^ Brent, Peter. The Mongol Empire: Genghis Khan: His Triumph and his Legacy. Book Club Associates, London. 1976.

- ^ Template:Harvard reference

- ^ Stearns, Peter N. (2001-09-24). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Chandler, T. Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1987.

- ^ Modelski, G. World Cities: –3000 to 2000. Washington, DC: FAROS 2000, 2003.

- ^ Ascalone, Enrico. Mesopotamia: Assyrians, Sumerians, Babylonians (Dictionaries of Civilizations; 1). Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007 (paperback, ISBN 0520252667).

- ^ Lloyd, Seton. The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: From the Old Stone Age to the Persian Conquest.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Books. ISBN 0631193960.

- ^ Allchin, Bridget (1997). Origins of a Civilization: The Prehistory and Early Archaeology of South Asia. New York: Viking.

- ^ Allchin, Raymond (ed.) (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ The World's First Coin: The Lydian Lion

- ^ The Hankyeoreh http://www.hani.co.kr/section-021168000/2008/05/021168000200805080709002.html

- ^ Hanseatic Chronology

- ^ Thilly, F. (1914). A history of philosophy. New York: H. Holt and.

- ^ Animated history of World Religions - from the "Religion & Ethics" part of the BBC website, interactive animated view of the spread of world religions (requires Flash plug-in).

- ^ Paper on Hinduism by Swami Vivekananda - Presented at World Parliament of Religion in 1893 (Text + Audio Version)

- ^ Buddhist texts (English translations)

- ^ Jainism - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ BBC Religions:Zoroastrianism

- ^ The Abrahamic Faiths: A Comparison How do Judaism, Christianity, and Islam differ? More from Beliefnet

- ^ Miller, James. Daoism: A Short Introduction (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2003). ISBN 1-85168-315-1

- ^ "Chinese Legalism: Documentary Materials and Ancient Totalitarianism"

- ^ Confucianism and Confucian texts

- ^ ::: 자랑스런 성균관 꽃피우는 유교문화 올바른 인성교육 성균관 예절교실 :::

- ^ "Socrates". 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1911.

- ^ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Plato

- ^ The Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ PDF: A Bibliography of Alexander the Great by Waldemar Heckel

- ^ Alexander III the Great, entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- ^ Trace Alexander's conquests on an animated map

- ^ The Mauryan Empire at All Empires

- ^ The Mauryan Empire from Britannica

- ^ Morgan, L. H. (1877). Ancient society; or, Researches in the lines of human progress from savagery, through barbarism to civilization. New York: H. Holt and Company.

- ^ Detailed history of the Roman Empire

- ^ Edward Gibbon. "General Observations on the Fall of the Roman Empire in the West", from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Brief excerpts of Gibbon's theories.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1906). in J.B. Bury (with an Introduction by W.E.H. Lecky): The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Volumes II, III, and IX). New York: Fred de Fau and Co..

- ^ Bury, John Bagnall (1923). History of the Later Roman Empire. Macmillan & Co., Ltd..

- ^ Bryce, J. B. (1907). The Holy Roman empire. New York: MacMillan.

- ^ Gascoigne, Bamber (2003). The Dynasties of China: A History. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 1-84119-791-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Gernet, Jacques (1982). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24130-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Han Dynasty by Minnesota State University

- ^ Buell, Paul D. (2003), Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0-8108-4571-7

- ^ Howorth, Henry H. History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: Part I: The Mongols Proper and the Kalmuks. New York: Burt Frankin, 1965 (reprint of London edition, 1876).

- ^ "Central America". MSN Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006.

- ^ Olmec Origins in The Southern Pacific Lowlands

- ^ History of the Inca Empire Inca history, society and religion.

- ^ Map and Timeline of Inca events

- ^ Islam, article at Enyclopaedia Britannica Online

- ^ Camp, J. M., & Dinsmoor, W. B. (1984). Ancient Athenian building methods. Excavations of the Athenian Agora, no. 21. [Athens]: American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

- ^ Drachmann, A. G. (1963). The mechanical technology of Greek and Roman antiquity, a study of the literary sources. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

- ^ Oleson, J. P. (1984). Greek and Roman mechanical water-lifting devices: the history of a technology. Phoenix, 16 : Tome supplémentaire. Dordrecht: Reidel.

- ^ Little, Lester K., ed., Plague and the End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541–750, Cambridge, 2006. ISBN 0-521-84639-0.

- ^ The History of the Bubonic Plague

- ^ Scientists Identify Genes Critical to Transmission of Bubonic Plague

- ^ An Empire's Epidemic

- ^ Justinian's Flea

- ^ The Great Arab Conquests

- ^ Rice, Eugene, F., Jr. (1970). The Foundations of Early Modern Europe: 1460-1559. W.W. Norton & Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McManners, J. (2002). The Oxford history of Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Pater, W. (1873). Studies in the history of the renaissance. London: Macmillan and.

- ^ history of Europe:: The Middle Ages – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Fred Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests Chapter 6

- ^ Golden age of Arab and Islamic Culture

- ^ The Islam Project: Overview of Muslim History

- ^ Dictionary of the Middle Ages (1989) Joseph R. Strayer, editor in chief, ISBN 0-684-19073-7

- ^ Rudimentary chronology of civil and ecclesiastical history, art, literature and civilisation, from the earliest period to 1856. (1857). London: John Weale.

- ^ Early Modern, historically speaking, refers to Western European history from 1501 (after the widely accepted end of the Late Middle Ages; the transition period was the 15th century) to either 1750 or circa 1790—1800 by which ever Epoch is favored by a school of scholars defining the period—which in many cases of Periodization, differs as well within a discipline such as Art, Philosophy, or History.

- ^ Grant, A. J. (1913). A history of Europe. London; Longmans, Green and Co.

- ^ Lavisse, E. (1891). General view of the political history of Europe. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

- ^ Postan, M. M., & Miller, E. (1987). The Cambridge economic history of Europe. Vol.2, Trade and industry in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Breasted, J. H., & Robinson, J. H. (1920). History of Europe, ancient and medieval: Earliest man, the Orient, Greece and Rome. Boston: Ginn and.

- ^ Thatcher, O. J., Schwill, F., & Hassall, A. (1909). A general history of Europe, 350-1900. London: Murray.

- ^ Nida, W. L. (1913). The dawn of American history in Europe. New York: Macmillian.

- ^ Robinson, J. H., Breasted, J. H., & Smith, E. P. (1921). A general history of Europe, from the origins of civilization to the present time. Boston: Ginn and company.

- ^ Goodrich, S. G. (1840). The second book of history, combined with geography; containing the modern history of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Illustrated by Engravings and colored maps, and designed as a sequel to "The first book of history. Boston: Hickling, Swan and Brewer.

- ^ Turner, E. R. (1921). Europe since 1870. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

- ^ Weir, A. (1886). The historical basis of modern Europe (1760-1815): an introductory study to the general history of Europe in the nineteenth century. London: S. Sonnenschein, Lowrey.

- ^ Hallam, H. (1837). View of the state of Europe during the middle ages. London: J. Murray.

- ^ Day, C. (1922). A history of commerce. London: Longmans, Green. (expanded version available)

- ^ The Economy of the Early Roman Empire

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana; a library of universal knowledge. (1918). New York: Encyclopedia Americana Corp. Page 539 (cf., The European Renaissance which flourished from the 14th to the 16th century [...])

- ^ Briffault, R. (1919). The making of humanity. London: G. Allen & Unwin ltd. 371 pages (cf. [...] humanism of the Renaissance [...])

- ^ The freethinker. (1881). London: G.W. Foote. Page 394 (cf., [...] scientific revolution began with the Italian Renaissance about 1500 [...])

- ^ Tsang, D. (2006). The entrepreneurial culture: network advantage within Chinese and Irish software firms. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. 195 pages (cf., [...] the concept entrepreneurship can be traced to the 18th century economist Richard Cantillon [...])

- ^ Conquest in the Americas

- ^ Was slavery the engine of economic growth?

- ^ Homepage of Angus Maddison

- ^ Toynbee, A. (1956). The industrial revolution. Boston: Beacon Press.

- ^ Russell, W., & Lady of Massachusetts. (1810). The history of modern Europe, particularly France, England, and Scotland with a view of the progress of society, from the rise of those kingdoms, to the late revolutions on the continent. Hanover, N.H.: Printed by and for Charles and Wm. S. Spear.

- ^ Ogg, F. A., & Sharp, W. R. (1926). Economic development of modern Europe. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ Ricardo Duchesne, "Asia First?", The Journal of the Historical Society, Vol. 6, Issue 1 (March 2006), pp.69-91

- ^ Joel L. Kraemer (1992), Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam, p. 1 & 148, Brill Publishers, ISBN 9004072594.

- ^ Imber, Colin. The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650: The Structure of Power. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 0-333-61386-4.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall, Palais. (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- ^ The 20th Century Research Project

- ^ Slouching Towards Utopia: The Economic History of the Twentieth Century

- ^ TIME Archives The greatest writers of the 20th Century

- ^ Etemad, B. (2007). Possessing the world: taking the measurements of colonisation from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. European expansion and global interaction, v. 6. New York: Berghahn Books.

- ^ Wells, H. G. (1922). The outline of history: being a plain history of life and mankind. New York: The Review of Reviews. Page 1200.

- ^ Herrmann David G (1996). The Arming of Europe and the Making of the First World War.

- ^ A multimedia history of World War I

- ^ Bunyan, James and H. H. Fisher, eds. The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1918: Documents and Materials (Stanford, 1961; first ed. 1934).

- ^ Reed, John. Ten Days that Shook the World. 1919, 1st Edition, published by BONI & Liveright, Inc. for International Publishers. Transcribed and marked by David Walters for John Reed Internet Archive. Penguin Books; 1st edition. June 1, 1980. ISBN 0-14-018293-4. Retrieved May 14, 2005.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon. The History of the Russian Revolution. Translated by Max Eastman, 1932. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 8083994. ISBN 0-913460-83-4. Transcribed for the World Wide Web by John Gowland (Australia), Alphanos Pangas (Greece) and David Walters (United States). Pathfinder Press edition. June 1, 1980. ISBN 0-87348-829-6. Retrieved May 14, 2005.

- ^ Davis, W. S., Anderson, W., & Tyler, M. W. (1918). The roots of the war; a non-technical history of Europe, 1870-1914, A.D. New York: Century.

- ^ World War II Database

- ^ World War II Encyclopedia by the History Channel

- ^ An Insider's Guide to the UN, Linda Fasulo, Yale University Press (November 1, 2003), hardcover, 272 pages, ISBN 0-300-10155-4

- ^ United Nations: The First Fifty Years, Stanley Mesler, Atlantic Monthly Press (March 1, 1997), hardcover, 416 pages, ISBN 0-87113-656-2

- ^ Avery, S. (2004). The globalist papers. Louisville, Ky: [Compari].

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2003), A People's History of the United States (5th ed.), New York, New York: HarperPerennial Modern Classics [2005 reprint], ISBN 0060838655

- ^ Race for the Superbomb, PBS website on the history of the H-bomb

- ^ As irrefutably demonstrated by a number of incidents, most prominently the October 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

- ^ Brown, Archie, et al, eds.: The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Russia and the Soviet Union (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

- ^ Gilbert, Martin: The Routledge Atlas of Russian History (London: Routledge, 2002).

- ^ Goldman, Minton: The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe (Connecticut: Global Studies, Dushkin Publishing Group, Inc., 1986).

- ^ Richard H. Schultz, Wayne A. Downing, Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, W. Bradley Stock, "Special Operations Forces: Roles And Missions In The Aftermath Of The Cold War". 1996. Page 59

- ^ Caraley, D. (2004). American hegemony: preventive war, Iraq, and imposing democracy. New York: Academy of Political Science. Page viii

- ^ After 1970s, the United States superpower status has came into question as that country's economic supremacy began to show signs of slippage. For more see, McCormick, T. J. (1995). America's half-century: United States foreign policy in the Cold War and after. The American moment. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Page 155

- ^ Europe Recast: A History of European Union by Desmond Dinan (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) ISBN 978-0-333-98734-6

- ^ Understanding the European Union 3rd ed by John McCormick (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005) ISBN 978-1-4039-4451-1

- ^ The Institutions of the European Union edited by John Peterson, Michael Shackleton, 2nd edition (Oxford University Press, 2006) ISBN 0198700520

- ^ The European Dream: How Europe's Vision of the Future Is Quietly Eclipsing the American Dream by Jeremy Rifkin (Jeremy P. Tarcher, 2004) ISBN 978-1-58542-345-3

- ^ Lallana, Emmanuel C., and Margaret N. Uy, "The Information Age".

- ^ von Braun, Joachim (2007). Globalization of Food and Agriculture and the Poor. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195695281.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (2005). The World Is Flat. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-29288-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Murray, Warwick E. (2006). Geographies of Globalization. New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0415317991.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Clayton, Julie. (Ed.). 50 Years of DNA, Palgrave MacMillan Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1-40-391479-8

- ^ Watson, James D. The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA (Norton Critical Editions). ISBN 978-0-393-95075-5

- ^ Calladine, Chris R.; Drew, Horace R.; Luisi, Ben F. and Travers, Andrew A. Understanding DNA, Elsevier Academic Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-12155089-9

- ^ The National Human Genome Research Institute

- ^ Ensembl The Ensembl Genome Browser Project

- ^ National Library of Medicine human genome viewer

- ^ UCSC Genome Browser

- ^ Human Genome Project

- ^ Earth Radiation Budget, http://marine.rutgers.edu/mrs/education/class/yuri/erb.html

- ^ Wood, R.W. (1909). Note on the Theory of the Greenhouse, Philosophical Magazine '17', p319–320. For the text of this online, see http://www.wmconnolley.org.uk/sci/wood_rw.1909.html

- ^ Edwards, A. R. (2005). The sustainability revolution: portrait of a paradigm shift. Gabriola, BC: New Society. Page 52

- ^ "Foreword," Energy and Power (A Scientific American Book), pp. vii–viii.

- ^ The Biosphere (A Scientific American Book), passim. Harrison Brown gives a particularly instructive example (p. 118) of a technological bottleneck that was broken in 18th-century England when three generations of the Abraham Darbys succeeded in developing coke as a substitute for depleted supplies of wood that had been the raw material for charcoal used in the manufacture of iron. Brown describes the linking of coal to iron as "second only to agriculture in its importance to man." It resulted in a rapid expansion of the iron industry and led directly to the development of the steam engine, which gave man for the first time a means of concentrating enormous quantities of inanimate energy. This combination of developments in turn gave rise to the Industrial Revolution.

- ^ M. King Hubbert, "The Energy Resources of the Earth," Energy and Power (A Scientific American Book), pp. 31–40.

- ^ Renewable energy (UNEP); Global Trends In Sustainable Energy Investment (UNEP).

- ^ NREL - US National Renewable Energy Laboratory

- ^ "The World at War". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ Robert V. Daniels, "History," Encyclopedia Americana, 1986 ed., vol. 14, p. 227.

- ^ Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study of History, vols. I–XII, Oxford University Press, 1934–61.

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant, The Lessons of History, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1968, prelude.

- ^ Berkeley Eddins and Georg G. Iggers, "History," Encyclopedia Americana, 1986 ed., vol. 14, pp. 243–44.

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, Newly translated and with an Introduction by Aubrey de Sélincourt, Harmondsworth, England, Penguin Books, 1965.

- ^ Robert V. Daniels, "History," Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 14, p. 226.

- ^ William Playfair, 1807: An Inquiry into the Permanent Causes of the Decline and Fall of Powerful and Wealthy Nations, p. 102.

References

- Wells, H. G. (1920). Outline of history; Volume One. New York: MacMillan.

- Spodek, H. (2001). The World's History: combined volume. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Parker, G. (1997). The Times Atlas of World History. London: Times Books.

- The Biosphere (A Scientific American Book), San Francisco, W.H. Freeman and Co., 1970, ISBN 0-7167-0945-7. This seminal book, originally a 1970 Scientific American magazine issue, covered virtually every major concern and concept that has since been debated regarding materials and energy resources, population trends and environmental degradation.

- Energy and Power (A Scientific American Book), San Francisco, W.H. Freeman and Co., 1971, ISBN 0-7167-0938-4.

- Jared Diamond (1996). Guns, Germs, and Steel: the Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-03891-2.

- Fernand Braudel (1996). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20308-9.

- Fernand Braudel (1973). Capitalism and Material Life, 1400-1800. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-010454-6.

- Marshall Hodgson, Rethinking World History: Essays on Europe, Islam, and World History (Cambridge, 1993).

- Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence: China, Europe and the Making of the Modern World Economy (Princeton, 2000).

- Clive Ponting, World History: a New Perspective (London, 2000).

- Ronald Wright, A Short History of Progress, Toronto, Anansi, 2004, ISBN 0-88784-706-4.

- Ankerl, Guy, Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western, Geneva: INUPRESS,2000, ISBN2-88155-004-5.

Further reading

- David Landes, "The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor", New York, W. W. Norton & Company (1999) ISBN 978-0393318883

- David Landes, "Why Europe and the West? Why Not China?," Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20:2, 3, 2006.

- Ricardo Duchesne, "Asia First?", The Journal of the Historical Society, Vol. 6, Issue 1 (March 2006), pp.69-91 (PDF)

- William H. McNeill, The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1963.

- Larry Gonick, The Cartoon History of the Universe, Volume One, Main Street Books, 1997, ISBN 978-0385265201, Volume Two, Main Street Books, 1994, ISBN 978-0385420938, Volume Three, W. W. Norton, 2002, ISBN 978-0393324037.

External links

- Universal Concise History of the World, 1832 Full text, free to read, American book on the history of the world with the intriguing perspective of 1832 America.

- WWW-VL: World History at European University Institute

- Five Epochs of Civilization. This web site is based on concepts in a book, Five Epochs of Civilization, by William McGaughey.

- MacroHistory: Prehistory to the 21st Century. A narrative on trends, successes and failures across the ages in power conflicts, religion, philosophy, and political institutions. Also, monthly commentaries with a historical perspective.

- Western Civilization: From Adam to Atom. Lecture notes from retired history professor, Dr. Raymond Jirran.

- EDUNet's Timemachine. Travel back to 10,000 years.

- The Great Wall

- Mohenjo Daro

- Taj Majal

- The Vatican City (In Spanish)

- Maps of Jerusalem (In Spanish)

- The Dead Sea Scrolls

- Mapping History Project - University of Oregon