Talysh language

| Talysh | |

|---|---|

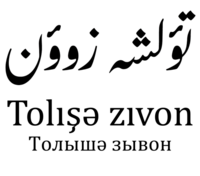

| Tolışə zıvon Tолышә зывон تؤلشه زوؤن | |

Talysh written in Nastaliq script (تؤلشه زوؤن), Latin script (Tolışə zıvon), and Cyrillic script (Tолышә зывон) | |

| Native to | Iran Azerbaijan |

| Region | Western and Southwestern Caspian Sea coastal strip |

| Ethnicity | Talysh |

Native speakers | 229,590[1] |

| Arabic script (Persian alphabet) in Iran Latin script in Azerbaijan Cyrillic script in Russia | |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Academy of Persian Language and Literature[citation needed] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | tly |

| Glottolog | taly1247 |

| ELP | Talysh |

| Linguasphere | 58-AAC-ed |

| |

Talysh is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Talysh (تؤلشه زوؤن, Tolışə Zıvon, Tолышә зывон)[3][4] is a Northwestern Iranian language spoken in the northern regions of the Iranian provinces of Gilan and Ardabil and the southern regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan by around 500,000-800,000 people. Talysh language is closely related to the Tati language. It includes many dialects usually divided into three main clusters: Northern (in Azerbaijan and Iran), Central (Iran) and Southern (Iran). Talysh is partially, but not fully, intelligible with Persian. Talysh is classified as "vulnerable" by UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[5]

History

The origin of the name Talysh is not clear but is likely to be quite old. The name of the people appears in early Arabic sources as Al-Taylasân and in Persian as Tâlišân and Tavâliš, which are plural forms of Tâliš. Northern Talysh (in the Republic of Azerbaijan) was historically known as Tâlish-i Guštâsbi. Talysh has always been mentioned with Gilan or Muqan. Writing in the 1330s AD, Hamdallah Mostowfi calls the language of Gushtaspi (covering the Caspian border region between Gilan to Shirvan) a Pahlavi language connected to the language of Gilan.[6] Although there are no confirmed records, the language called in Iranian linguistics as Azari can be the antecedent of both Talysh and Tati. Miller's (1953) hypothesis that the Âzari of Ardabil, as appears in the quatrains of Shaikh Safi, was a form of Talysh was confirmed by Henning (1954).[7][8] In western literature the people and the language are sometimes referred to as Talishi, Taleshi or Tolashi. Generally speaking, written documents about Taleshi are rare.

The first information about the Talysh language in Russian can be found in Volume X of Strachevsky's "Encyclopedic Dictionary" ("Справочный энциклопедический словарь"), published in St. Petersburg in 1848. The work says:

"The Talysh dialect is one of the six main dialects of Persian. It is used in the Talysh khanate and is probably the homeland of that language. Due to its grammatical and lexicographic forms, this language is noticeably different from other dialects. Except for the addition of the plural suffix "un", it is peculiar and is not derived from any Pahlavi or any other language. This language puts all relative pronouns before the noun, and the pronouns themselves are original in it.[9]

The second information about the Talysh language is provided by Ilya Berezin, a professor at Kazan University, in Russian, but not in Russian, but in French. In 1853, Berezin's book on Persian grammar was published in Kazan. In the same year, his book "Recherches sur les dialectes persans" was published in Kazan. Experts still refer to this work as the first work of Russian Iranians in the field of Iranian dialectology. He used the "Talysh" songs given in A. Khodzko's work. IN Berezin's work consists of two parts - a grammatical essay and songs from A. Khodzko's work. IN Berezin writes that he conducted his research on Iranian dialects on the basis of materials he personally collected and studied, but does not write anywhere with whom, when and in what area he collected them. In the work, Talysh words are distorted. IN Berezin writes about the quartets taken from the work of A. Khodzko:

"Here I present to the reader a new translation of the Talysh, Gilan and Mazandaran songs and accompany them with critical notes; the Talysh texts, if not in Khodzko, were restored by me on the basis of his transcription." However, the author writes that "grammatical rules are not strictly observed in the Talysh language, as the verb's news form is usually confused almost all the time, i.e. instead of the aorist preterit, the future time in the present tense, etc. is used. " Going even further, he writes: "In the Talysh language, the verb is the most difficult, the most confusing and the most dubious part."[10]

Geography

In the north of Iran, there are six cities where Talysh is spoken: Masal, Rezvanshar, Talesh, Fuman, Shaft, and Masuleh (in these cities some people speak Gilaki and Turkish as well). The only towns where Talysh is spoken exclusively are the townships of Masal and Masuleh. In other cities, in addition to Talysh, people speak Gilaki and Azerbaijani. In Azerbaijan there are eight cities where Talysh is spoken[citation needed]: Astara (98%), Lerik (90%), Lenkoran (90%), Masalli (36%).[citation needed][clarification needed]

Talysh has been under the influence of Gilaki, Azeri Turkic, and Persian. In the south (Taleshdula, Masal, Shanderman, and Fumanat) the Talysh and Gilaks live side by side; however, there is less evidence that a Talysh family replaces Gilaki with its own language. In this region, the relation is more of a contribution to each other's language. In the north of Gilan, on the other hand, Azeri Turkic has replaced Talysh in cities like Astara after the migration of Turkic speakers to the region decades ago. However, the people around Lavandvil and its mountainous regions have retained Talysh. Behzad Behzadi, the author of "Azerbaijani Persian Dictionary" remarks that: "The inhabitants of Astara are Talyshis and in fifty years ago (about 1953) that I remember the elders of our family spoke in that language and the great majority of dwellers also conversed in Talyshi. In the surrounding villages, a few were familiar with Turkic".[11] From around Lisar up to Hashtpar, Azeri and Talysh live side by side, with the latter mostly spoken in small villages. To the south of Asalem, the influence of Azeri is negligible and the tendency is towards Persian along with Talysh in cities. In the Azerbaijan republic, Talysh is less under the influence of Azeri and Russian than Talysh in Iran is affected by Persian.[12] Central Talysh has been considered the purest of all Talysh dialects.[8]

Classification and related languages

Talysh belongs to the Northwestern Iranian branch of Indo-European languages. The living language most closely related to Talysh is Tati. The Tati group of dialects is spoken across the Talysh range in the southwest[clarification needed] (Kajal and Shahrud) and south (Tarom).[8] This Tatic family should not be confused with another Tat family which is more related to Persian. Talysh also shares many features and structures with Zazaki, now spoken in Turkey, and the Caspian languages and Semnani of Iran.

Dialects

The division of Talysh into three clusters is based on lexical, phonological and grammatical factors.[13] Northern Talysh distinguishes itself from Central and Southern Talysh not only geographically but culturally and linguistically as well. Speakers of Northern Talysh are found almost exclusively in the Republic of Azerbaijan but can also be found in the neighbouring regions of Iran, in the Province of Gilan. The varieties of Talysh spoken in the Republic of Azerbaijan are best described as speech varieties rather than dialects. Four speech varieties are generally identified on the basis of phonetic and lexical differences. These are labeled according to the four major political districts in the Talysh region: Astara, Lankaran, Lerik, and Masalli. The differences between the varieties are minimal at the phonetic [14] and lexical level.[3] Mamedov (1971) suggests a more useful dialectal distinction is one between the varieties spoken in the mountains and those spoken in the plains. The morphosyntax of Northern Talysh is characterized by a complicated split system which is based on the Northwest Iranian type of accusativity/ergativity dichotomy: it shows accusative features with present-stem-based transitive constructions, whereas past-stem-based constructions tend towards an ergative behavior.[15] In distant regions like Lavandevil and Masuleh, the dialects differ to such a degree that conversations begin to be difficult.[12] In Iran, the northern dialect is in danger of extinction.

| The major dialects of Talysh | ||

|---|---|---|

| Northern (in Azerbaijan Republic and in Iran (Ardabil and Gilan provinces) from Anbaran to Lavandevil) including: | Central (in Iran (Gilan province) from Haviq to Taleshdula/Rezvanshahr district) Including: | Southern (in Iran from Khushabar to Fumanat) including: |

| Astara, Lankaran, Lerik, Masalli, Karaganrud/Khotbesara, Lavandevil | Taleshdula, Asalem, Tularud | Khushabar, Shanderman, Masuleh, Masal, Siahmazgar |

Some Northern dialects' differences

The northern dialect has some salient differences from the central and southern dialects, e.g.:[12]

| Taleshdulaei | Example | Lankarani | Example | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| â | âvaina | u | uvai:na | mirror |

| dâr | du | tree | ||

| a | za | â | zârd | yellow |

| u/o | morjena | â | mârjena | ant |

| x | xetē | h | htē | to sleep |

| j | gij | ž | giž | confused |

Alignment variation

The durative marker "ba" in Taleshdulaei changes to "da" in Lankarani and shifts in between the stem and person suffixes:

- ba-žē-mun → žē-da-mun

Such a diversification exists in each dialect too, as in the case of Masali[16]

Phonology

The following is the Northern Talysh dialect:

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | |

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | h |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ɣ | ||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i ~ ɪ | (ɨ) | u |

| ʏ | |||

| Mid | e | ə | o ~ ɔ |

| Low | a ~ æ | ɑ |

- [ʏ] only occurs in free variation with /u/, whereas /a/ is often palatalized as [æ].

- [ɪ, ɨ, ɔ] are heard as allophones of /i, ə, o/.

- Vowel sounds followed by a nasal consonant, /_nC/, often tend to be nasalized.[17]

Scripts

The vowel system in Talysh is more extended than in standard Persian. The prominent differences are the front vowel ü in central and northern dialects and the central vowel ə.[8] In 1929, a Latin-based alphabet was created for Talysh in the Soviet Union. However, in 1938 it was changed to Cyrillic-based, but it did not gain extensive usage for a variety of reasons. An orthography based on Azeri Latin is used in Azerbaijan,[4] and also in Iranian sources, for example on the IRIB's ParsToday website.[18] The Perso-Arabic script is also used in Iran, although publications in the language are rare and are mostly volumes of poetry.[19] The following tables contain the vowels and consonants used in Talysh. The sounds of the letters on every row, pronounced in each language, may not correspond fully.

Monophthongs

| IPA | 1929–1938 | ISO 9 | Perso-Arabic script | KNAB (199x(2.0)) | Cyrillic | Other Romanization | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ɑː | a | a | آ, ا | a | а | â | âv |

| a ~ æ | a | a̋ | َ, اَ | ǝ | ә | a, ä | asta |

| ə | ә | - | ِ, اِ or َ, اَ | ə | ə | e, a | esa |

| eː | e | e | ِ, اِ | e | е | e | nemek |

| o ~ ɔ | o | o | ا, ُ, و | o | о | o | šalvo |

| u | u | u | او, و | u | у | u | udmi |

| ʏ | u | - | او, و | ü | у | ü | salü, kü, düri, Imrü |

| ɪ ~ i | ъ | y | ای, ی | ı | ы | i | bila |

| iː | i | i | ای, ی | i | и | i, ị | neči, xist |

| Notes: ISO 9 standardization is dated 1995. 2.0 KNAB romanization is based on the Azeri Latin.[20] | |||||||

Diphthongs

| IPA | Perso-Arabic script | Romanization | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ɑːɪ | آی, ای | âi, ây | bâyl, dây |

| au | اَو | aw | dawlat |

| æɪ | اَی | ai, ay | ayvona, ayr |

| ou | اُو | ow, au | kow |

| eɪ | اِی | ey, ei, ay, ai | keybânu |

| æːə | اَ | ah | zuah, soahvona, buah, yuahnd, kuah, kuahj |

| eːə | اِ | eh | âdueh, sueh, danue'eh |

| ɔʏ | اُی | oy | doym, doymlavar |

Consonants

| IPA | 1929–1938 | ISO 9 | Perso-Arabic script | KNAB (199x(2.0)) | Cyrillic | Other Romanization | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | p | p | پ | p | п | p | pitâr |

| b | в | b | ب | b | б | b | bejâr |

| t | t | t | ت, ط | t | т | t | tiž |

| d | d | d | د | d | д | d | debla |

| k | k | k | ک | k | к | k | kel |

| ɡ | g | g | گ | g | г | g | gaf |

| ɣ | ƣ | ġ | غ | ğ | ғ | gh | ghuša |

| q | q | k̂ | ق | q | ҝ | q | qarz |

| tʃ | c, ç | č | چ | ç | ч | ch, č, c | čâki |

| dʒ | j | ĉ | ج | c | ҹ | j, ĵ | jâr |

| f | f | f | ف | f | ф | f | fel |

| v | v | v | و | v | в | v | vaj |

| s | s | s | س, ص, ث | s | с | s | savz |

| z | z | z | ز, ذ, ض, ظ | z | з | z | zeng |

| ʃ | ş | š | ش | ş | ш | sh | šav |

| ʒ | ƶ | ž | ژ | j | ж | zh | ža |

| x | x | h | خ | x | x | kh | xâsta |

| h | h | ḥ | ه, ح | h | һ | h | haka |

| m | m | m | م | m | м | m | muža |

| n | n | n | ن | n | н | n | nân |

| l | l | l | ل | l | л | l | lar |

| lʲ | - | - | - | - | - | - | xâlâ, avâla, dalâ, domlavar, dalaza |

| ɾ | r | r | ر | r | р | r | raz |

| j | y | j | ی | y | ј | y, j | yânza |

| Notes: ISO 9 standardization is dated 1995. 2.0 KNAB romanization is based on the Azeri Latin.[20] | |||||||

Differences from Persian

The general phonological differences of some Talysh dialects with respect to standard Persian are as follows:[12]

| Talysh sound | Talysh example word | Corresponding Persian sound | Persian example word | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| u | duna | â | dâne | seed |

| i | insân | initial e | ensân | human being |

| e | tarâze | u | terâzu | balance (the apparatus) |

| e | xerâk | o | xorâk | food |

| a in compound words | mâng-a-tâv | ∅ | mah-tâb | moonlight |

| v | âv | b | âb | water |

| f | sif | b | sib | apple |

| x | xâsta | h | âheste | slow |

| t | tert | d | tord | brittle |

| j | mija | ž | može | eyelash |

| m | šamba | n | šanbe | Saturday |

| ∅ | mēra | medial h | mohre | bead |

| ∅ | ku | final h | kuh | mountain |

Grammar

Talysh has a subject–object–verb word order. In some situations the case marker, 'i' or 'e' attaches to the accusative noun phrase. There is no definite article, and the indefinite one is "i". The plural is marked by the suffixes "un", "ēn" and also "yēn" for nouns ending with vowels. In contrast to Persian, modifiers are preceded by nouns, for example: "maryami kitav" (Mary's book) and "kava daryâ" (livid sea). Like most other Iranian dialects there are two categories of inflexion, subject and object cases. The "present stem" is used for the imperfect and the "past stem" for the present in the verbal system. That differentiates Talysh from most other Western Iranian dialects. In the present tense, verbal affixes cause a rearranging of the elements of conjugation in some dialects like Tâlešdulâbi, e.g. for expressing the negation of b-a-dašt-im (I sew), "ni" is used in the following form: ni-m-a-dašt (I don't sew)."m" is first person singular marker, "a" denotes duration and "dašt" is the past stem.

Pronouns

Talysh is a null-subject language, so nominal pronouns (e.g. I, he, she) are optional. For first person singular, both "az" and "men" are used. Person suffixes are not added to stems for "men".[12] Examples:

- men xanda. (I read.), az bexun-em (Should I read ...)

- men daxun! (Call me!), az-daxun-em (Should I call ...)

There are three prefixes in Talysh and Tati added to normal forms making possessive pronouns. They are: "če / ča" and "eš / še".

|

|

Verbs

- preverbs: â/o, da, vi/i/ē/â, pē/pi

- Negative Markers: ne, nē, ni

- Subjunctive/Imperative prefix: be

- Durative markers: a, ba, da

The following Person Suffixes are used in different dialects and for different verbs.[12]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -em, -ema, -emē, -ima, -um, -m | -am, -emun(a), -emun(ē), -imuna, -imun |

| 2nd person | -i, -er(a), -eyē, -išaو -š | -a, -erun(a), -eyunē, -iruna, -iyun |

| 3rd person | -e, -eš(a), -eš(ē), -a, -ē, -u | -en, -ešun(a), -ešun(ē), -ina, -un |

Conjugations

The past stem is inflected by removing the infinitive marker (ē), however the present stem and jussive mood are not so simple in many cases and are irregular. For some verbs, present and past stems are identical. The "be" imperative marker is not added situationally.[21] The following tables show the conjugations for first-person singular of "sew" in some dialects of the three dialectical categories:[12]

Stems and imperative mood

| Northern (Lavandavili) | Central (Taleshdulaei) | Southern (Khushabari) | Tati (Kelori) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | dut-ē | dašt-ē | dēšt-ē | dut-an |

| Past stem | dut | dašt | dēšt | dut |

| Present stem | dut | dērz | dērz | duj |

| Imperative | be-dut | be-dērz | be-dērz | be-duj |

Active voice

| Form | Tense | Northern (Lavandavili) |

Central (Taleshdulaei) |

Southern (Khushabari) |

Tati (Kelori) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | - | dut-ē | dašt-ē | dēšt-ē | dut-an |

| Indicative | Present | dute-da-m | ba-dašt-im | dērz-em | duj-em |

| „ | Past | dut-emē | dašt-em | dēšt-em | bedut-em |

| „ | Perfect | dut-amē | dašt-ama | dēšt-ama | dute-mē |

| „ | Past imperfective | dute-aymē | adērz-ima | dērz-ima | duj-isēym |

| „ | Past perfect | dut-am bē | dašt-am-ba | dēšt-am-ba | dut-am-bē |

| „ | Future | pima dut-ē | pima dašt-ē | pima dēšt-ē | xâm dut-an |

| „ | Present progressive | dute da-m | kâr-im dašt-ē | kâra dērz-em | kerâ duj-em |

| „ | Past progressive | dut dab-im | kârb-im dašt-ē | kârb-im dēšt-ē | kerâ duj-isēym |

| Subjunctive | Present | be-dut-em | be-dērz-em | be-dērz-em | be-duj-em |

| „ | Past | dut-am-bu | dašt-am-bâ | dēšt-am-bu | dut-am-bâ |

| Conditional | Past | dut-am ban | ba-dērz-im | be-dērz-im | be-duj-im |

Passive voice

| Form | Tense | Northern (Lavandavili) |

Central (Taleshdulaei) |

Southern Khushabari) |

Tati (Kelori) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | - | dut-ē | dašt-ē | dēšt-ē | dut-an |

| Indicative | Present | duta bē dam | dašta babim | dēšta bum | duta bum |

| „ | Preterite | duta bēm | dašta bima | dēšta bima | bedujisim |

| „ | Imperfective preterite | duta be-am be | dašta abima | dēšta bistēm | duta bisim |

| „ | Perfect | duta beam | dašta baima | dērzistaima | dujisim |

| „ | Pluperfect | duta beam bē | dērzista bim | dērzista bim | dujisa bim |

| „ | Present progressive | duta bē dam | kâra dašta babima | kšra dēšta bum | kerâ duta bum |

| „ | Preterite progressive | duta bēdabim | kâra dašta abima | kâra dēšta bistēymun | kerâ duta bisim |

| Subjunctive | Present | duta bebum | dašta bebum | dēšta bebum | duta bebum |

| „ | Preterite | duta beabum | dašta babâm | dēšta babâm | dujisa biya-bâm |

Nouns and adpositions

There are four "cases" in Talysh, the nominative (unmarked), the genitive, the (definite) accusative and ergative.

The nominative case (characterized by null morpheme on nouns) encodes the subject; the predicate; the indefinite direct object in a nominative clause; definite direct object in an ergative clause; the vowel-final main noun in a noun phrase with another noun modifying it; and, finally, the nominal element in an adpositional phrases with certain adpositions. The examples below are from Pirejko 1976[3]

Nənə

mother

ıştə

REFL

zoə

son

pe-də

love.VN-LOC

'The mother loves her son'

Əv

3SG

rəis-e

boss-PRED

'S/he is a boss'

Az

1SG

vıl

flower

bı-çın-ım

FUT-pick.PRST-FUT

bo

for

tını

2SG.ERG

'I will pick a flower for you'

Əy

3SG.ERG

çımı

1SG.POSS

dəftər

notebook

dıry-əşe

tear.apart.PP-3SG.PFV.TR

'S/he tore apart my notebook'

hovə

sister

şol

scarf

'sister's scarf'

bə

to

şəhr

city

'to the city'

The ergative case, on the other hand, has the following functions: indicating the subject of an ergative phrase; definite direct object (in this function, ergative case takes the form of -ni after vowel-final stems); nominal modifier in a noun phrase; the nominal element in adpositional phrases with most adpositions.

Ağıl-i

child-ERG

sef

apple

şo

?

do-şe

throw.PP-3SG.PFV.ERG

'the child threw the apple'

Im

DEM

kəpot-i

dress-ERG

se-də-m

buy.VN-LOC-1SG

bə

for

həvə-yo

sister-BEN

'I'm buying this dress for (my) sister'

Iştə

REFL

zoə-ni

son-ERG

voğan-də

send.VN-LOC

bə

to

məktəb

school

'S/he is sending his/her son to the school'

jen-i

woman-ERG

dəs

hand

'a hand's woman'

muallimi-i

teacher-ERG

ton-i-ku

side-ERG-ABL

omə-m

come.1SG.PP-PFV.NOM

'I approached the teacher'

The accusative form is often used to express the simple indirect object in addition to the direct object. These "cases" are in origin actually just particles, similar to Persian prepositions like "râ".

| Case | Marker | Example(s) | Persian | | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | - | sepa ve davaxa. | Sag xeyli hâfhâf kard. | | The dog barked much. |

| Accusative | -i | gerd-i âda ba men | Hame râ bede be man. | | Give them all to me! |

| „ | -e | âv-e-m barda | Âb râ bordam. | | I took the water. |

| Ablative | -kâ, -ku (from) | ba-i-kâ-r če bapi | Az u ce mixâhi? | | What do you want from him? |

| „ | -ka, -anda (in) | âstâra-ka tâleši gaf bažēn | Dar Âstârâ Tâleši gab (harf) mizanand. | | They talk Talyshi in Astara. |

| „ | -na (with) | âtaši-na mezâ maka | Bâ âtaš bâzi nakon. | | Don't play with fire! |

| „ | -râ, -ru (for) | me-râ kâr baka te-râ yâd bigē | Barâye man kâr bekon Barâye xodat yâd begir. | | Work for me, learn for yourself. |

| „ | -ken (of) | ha-ken hēsta ča (čečiya) | Az ân, ce bejâ mânde? (Hamân ke hast, cist?) | | What is of which is left? |

| „ | ba (to) | ba em denyâ del mabēnd | Be in donyâ del maband. | | Don't take the world dear to your heart! |

| Ergative | -i | a palang-i do lorzon-i (Aorist) | Ân palang deraxt râ larzând. | | That leopard shook the tree. |

Vocabulary

| English | Zazaki | Kurmanji Kurdish | Central (Taleshdulaei) | Southern (Khushabari / Shandermani) | Tati (Kelori / Geluzani) | Talysh | Persian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| big | gird, pîl | gir, mezin | ? | yâl | yâl | pilla | bozorg, gat, (yal, pil) |

| boy, son | laj / laz / lac | law (boy), kur (son) | zoa, zua | zôa, zue | zu'a, zoa | zâ | Pesar |

| bride | veyve | bûk | vayü | vayu | gēša, veyb | vayu, vēi | arus |

| cat | pisîng, xone (tomcat) | pisîk, kitik | kete, pišik, piš | peču | peču, pešu, piši | pešu | gorbe, piši |

| cry (v) | bermayen | girîn | bamē | beramestē | beramē | beramesan | geristan |

| daughter, girl (little) | kêna/keyna, çêna[22] | keç (girl), dot (daughter) | kina, kela | kilu, kela | kina, kel(l)a | kille, kilik | doxtar |

| day | roc, roz, roj | roj | rüž, ruj | ruz | ruz, roz | ruz | ruz |

| eat (v) | werden | xwarin | hardē | hardē | hardē | hardan | xordan |

| egg | hak | hêk | uva, muqna, uya | âgla | merqona | xâ, merqowna | toxme morq |

| eye | çim | çav | čâš | čaš, čam | čēm | čašm | čašm |

| father | pî, pêr, bawk, babî[23] | bav | dada, piya, biya | dada | ? | pē | pedar |

| fear (v) | tersayen | tirsîn | purnē, târsē | târsinē, tarsestē | tarsē | tarsesan | tarsidan |

| flag | ala[24] | ala | filak | parčam | ? | ? | parčam, derafš |

| food | nan, werd | xwarin | xerâk | xerâk | xerâk | xuruk | xorâk |

| go (v) | şîyen | çûn | šē | šē | šē | šiyan | raftan (šodan) |

| house | keye, çeye[25][26] | xanî | ka | ka | ka | ka | xâne |

| language; tongue | ziwan, zon | ziman | zivon | zun | zavon | zuân | zabân |

| moon | aşme | heyv / hîv | mâng, uvešim | mâng | mang | mung, meng | mâh |

| mother | maye, mare, dayîke, dadî[27] | mak, dayik | mua, mu, nana | nana | ? | mâ, dēdē, nana | mâdar, nane |

| mouth | fek | dev | qav, gav | ga, gav, ga(f) | qar | gar | dahân, kak |

| night | şew | şev | šav | şaw | šav | šav | šab |

| north | zime, vakur[28] | bakur | kubasu | šimâl | ? | ? | šemâl |

| high | berz | bilind, berz[29] | berz | berz | berj | berenj | boland |

| say (v) | vatene | gotin | votē | vâtē | vâtē | vâtan | goftan |

| sister | waye | xwîşk, xwang | huva, hova, ho | xâlâ, xolo | xâ | xâv, xâ | xâhar |

| small | qic, qij, wirdî | biçûk, qicik | ruk, gada | ruk | ruk | velle, xš | kučak |

| sunset | rocawan, rojawan[30] | rojava | šânga | maqrib | ? | ? | maqreb |

| sunshine | tije,[31] zerq | tîroj, tav/hetav | şefhaši | âftâv | ? | ? | âftâb |

| water | aw, awk | av | uv, ôv | âv | âv | âv | âb |

| woman, wife | cinî | jin | žēn | žēn, žen | yen, žen | zanle, zan | zan |

| yesterday | vizêr | duh/diho | zina | zir, izer | zir, zer | zir | diruz, di |

References

- ^ "Talysh". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ کلباسی, ایران [in Persian]. شباهتها و تفاوتهای تالشی، گیلکي و مازندرانی [Similarities and differences between Talysh, Gilaki and Mazandarani]. زبان شناسی [Linguistics] (in Persian). 20 (1): 58–97. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pirejko, L. A., 1976. Talyšsko-russkij slovar (Talyshi-Russian Dictionary), Moscow.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Məmmədov, Novruzəli; Ağayev, Şahrza (1996). Əlifba — Tolışi əlifba. Baku: Maarif.

- ^ "Talysh". UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ مستوفی، حمدالله: «نزهةالقلوب، به كوشش محمد دبیرسیاقی، انتشارات طهوری، ۱۳۳۶. Mostawafi, Hamdallah, 1336 AP / 1957 AD. Nozhat al-Qolub. Edit by Muhammad Dabir Sayyaqi. Tahuri publishers. (in Persian)

- ^ Henning, W. B. 1954. The Ancient Language of Azerbaijan. Transactions of the Philological Society, London. p 157-177. [1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Asatrian, G. and H. Borjian, 2005. Talish: people and language: The state of research. Iran and the Caucasus 9/1, p 43-72

- ^ "НЭБ - Национальная электронная библиотека". Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Грамматика персидского языка, составленная И. Березиным, профессором Казанского университета. - Казань : тип. Ун-та, 1853. - XVI, 480 с.; 23.

- ^ Behzadi, B, 1382 AP / 2003 AD. Farhange Azarbâyjani-Fârsi (Torki), p. 10. Publication: Farhange Moâser Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 964-5545-82-X

In Persian: حقیقت تاریخی این است که آذربایجانی، ایرانی است و به زبان ترکی تکلم میکند. اینکه چگونه این زبان در بین مردم رایج شد، بحثی است که فرصت دیگر میخواهد. شاهد مثال زیر میتواند برای همه این گفتگوها پاسخ شایسته باشد. اهالی آستارا طالش هستند و تا پنجاه سال پیش که نگارنده به خاطر دارد پیران خانواده ما به این زبان تکلم میکردند و اکثریت عظیم اهالی نیز به زبان طالشی صحبت میکردند. در دهات اطراف شاید تعداد انگشتشماری ترکی بلد بودند. - ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Abdoli, A. 1380 AP / 2001 AD. Farhange Tatbiqiye Tâleši-Tâti-Âzari (Comparative dictionary of Talyshi-Tati-Azari), p 31-35, Publication:Tehran, "šerkate Sahâmiye Entešâr" (in Persian).

- ^ Stilo, D. 1981. The Tati Group in the Sociolinguistic Context of Northwestern Iran. Iranian Studies XIV

- ^ Mamedov, N., 1971. Šuvinskij governs talyšskogo yazyka (Talyshi dialect of Shuvi), PhD dissertation, Baku. (in Russian)

- ^ Schulze, W., 2000. Northern Talysh. Publisher: Lincom Europa. ISBN 3-89586-681-4 [2] Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ De Caro, G. Alignment variation in Southern Tāleši (Māsāl area). School of Oriental and African Studies / Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Project. [3] Archived 6 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schulze, Wolfgang (2000). Northern Talysh. Languages of the World/Materials, 380: München: Lincom. p. 9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Əsasə səyfə". Parstoday (in Talysh). Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Paul, Daniel (2011). A Comparative Dialectal Description of Iranian Taleshi. University of Manchester. p. 324.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pedersen, T. T.. Transliteration of Non-Roman Scripts Archived 20 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Talyshi transliteration Archived 24 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Masali, K. 1386 AP / 2007 AD. Sâxte fe'l dar zabâne Tâleši (Guyeše Mâsâl) (Conjugations in Talyshi language (Masali dialect)). "Archived copy" (PDF) (in Persian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Encamên lêgerînê". Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Encamên lêgerînê". Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Encamên lêgerînê". Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Keye kelimesinin anlamı". Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Çeye kelimesinin anlamı". Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Encamên lêgerînê". Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Encamên lêgerînê". Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Encamên lêgerînê". Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Encamên lêgerînê". Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Tîje kelimesinin anlamı". Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Further reading

- Abdoli, A. (2001). Tat and Talysh literature (Iran and Azerbaijan republic) (in Persian). Tehran: Entešâr Publication. ISBN 964-325-100-4. Archived from the original on 2 January 2009. (1380 AP / 2001 AD)

- Asatrian, G; Borjian, Habib (2005). "Talish: people and language: The state of research". Iran and the Caucasus. 9 (1). Brill: 43–72. doi:10.1163/1573384054068169.

- also available at Asatrian, Garnik; Borjian, Habib (2005). Talish and the Talishis: The State of Research. Columbia Academic Commons (Report). doi:10.7916/D8D23960.

- Bazin, M. (1974). "Le Tâlech et les tâlechi: Ethnic et region dans le nord-ouest de l'Iran". Bulletin de l'Association de Geographes Français (in French). 417–418 (417): 161–170. doi:10.3406/bagf.1974.4771.

- Bazin, M. (1979). "Recherche des papports entre diversité dialectale et geographie humaine: l'example du Tâleš". In Schweizer, G. (ed.). Interdisciplinäre Iran-Forschung: Beiträge aus Kulturgeographie, Ethnologie, Soziologie und Neuerer Geschichte (in French). Wiesbaden. pp. 1–15.

- Bazin, M. (1981). "Quelque échantillons des variations dialectales du tâleši". Studia Iranica (in French). 10: 111–124, 269–277.

- Paul, D. (2011). A comparative dialectal description of Iranian Taleshi (PhD Dissertation). University of Manchester.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (1996). "The Taleshi of Asalem". Studia Iranica. 25. New York: 83–113. doi:10.2143/SI.25.1.2003967.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (2000). "Tâlish". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

External links

- Positive Orientation Towards the Vernacular among the Talysh of Sumgayit

- Example of Talyshi Language

- B. Miller. Talysh language and the languages of Azeri (in Russian)

- A. Mamedov, k.f.n. Talishes as carriers of the ancient language of Azerbaijan (in Russian)

- A short note on the history of Talyshi literature (in Persian)