Culture of Israel

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Israel |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Sport |

The culture of Israel is closely associated with Jewish culture and rooted in the Jewish history of the diaspora and Zionist movement. It has also been influenced by Arab culture and the history and traditions of the Arab Israeli population and other ethnic minorities that live in Israel, among them Druze, Circassians, Armenians and others.

Tel Aviv and Jerusalem are considered the main cultural hubs of Israel. The New York Times has described Tel Aviv as the "capital of Mediterranean cool," Lonely Planet ranked it as a top ten city for nightlife, and National Geographic named it one of the top ten beach cities.[1] Similarly, Jerusalem has earned international acclaim; Time magazine included it in its list of the "World’s Greatest Places," and Travel+Leisure ranked it as the third favorite city in ME and Africa among its readers.[2]

With over 200 museums, Israel has the highest number of museums per capita in the world, with millions of visitors annually.[3] Israeli art's development, heavily influenced by 20th century European trends was heavily centered in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Major art museums operate in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa and Herzliya, as well as in many towns and Kibbutzim. The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra plays at venues throughout the country and abroad, and almost every city has its own orchestra, many of the musicians hailing from the former Soviet Union. Folk dancing is popular in Israel, and Israeli modern dance companies, among them the Batsheva Dance Company, are highly acclaimed in the dance world. Habima Theatre, which is considered the national theatre of Israel, was established in 1917. Israeli filmmakers[4] and actors[5] have won awards at international film festivals in recent years.[6] Since the 1980s, Israeli literature has been widely translated, and several Israeli writers have achieved international recognition.[7]

There has been minimal cultural exchange between Israel’s Jewish and Arab populations. Jews from Arab-Muslim Middle East communities brought with them elements from the majority cultures in which they lived. The mixing of Ashkenazi, Sephardi, and Middle Eastern traditions have advanced modern Israeli culture, along with traditions brought by Russian, former Soviet republican, Central European and American immigrants. The Hebrew language revival has also developed Israel’s modern culture. Israel’s culture is based on its cultural diversity, shared language, and common religious and historical Jewish tradition.[8]

History

With a diverse population of immigrants from five continents and more than 100 countries, and significant subcultures like the Mizrahim, Arabs, Russian Jews, Ethiopian Jews, Secular Jews and the Ultra Orthodox, each with its own cultural networks, Israeli culture is extremely varied. It follows cultural trends, and changes across the globe, as well as expressing a unique spirit of its own. In addition, Israel is a family-oriented society with a strong sense of community.[9]

Influences and impact

Ancient Near East civilizations

Ancient Israel, as a civilization of the ancient Near East, was influenced to some degree by other regional cultures. The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet was adapted from the Phoenician alphabet and the square script is a derivative of the Aramaic alphabet. Zoroastrianism of Ancient Iran is believed to had an influence on Jewish eschatology. Jewish mythology contains similarities to Mesopotamian mythologies, such as the Enūma Eliš of Babylon, the Genesis creation narrative, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the Genesis flood narrative.

Judaism, Christianity and Western civilization

Judaism, which originated in Ancient Israel, represents the foundation of much of Western civilization's traits, thanks to its relation to Christianity.[11][12] It impacted the West in a multitude of ways, from its ethics, to its practices to monotheism;[13] all of its benefits largely impacted the world through Christianity.[14] The Hebrew Bible, authored by Jews in the Land of Israel from the 8th to the 2nd century BCE,[15] is a cornerstone of Western civilization.[10] Around 63 BCE, Judea became part of the Roman Empire; around 6 BCE, Jesus was born to a Jewish family in the town of Nazareth, and decades later, was crucified under Pontius Pilate. His followers later believed that he was resurrected, inspiring them to spread the new Christian religion throughout the world. Christianity took hold in the Hellenistic Greco-Roman world, which eventually grew into the entirety of Europe, thanks to Roman expansion. These nations later became the very foundation of today's 'Western world'.[16]

Christianity, the religion of the West and essential religion of the Western World,[10] grew from Judaism,[17][18][19] and began as a Second Temple Judaic sect in the mid-1st century.[20][21] The New Testament, authored by first-century Jews,[22] is one of the bedrock texts of Western civilization as well.[23]

Islamic civilization

Islam was strongly influenced by Judaism in its fundamental religious outlook, structure, jurisprudence and practice.[24] Islam derives its ideas of holy text, the Qur'an, ultimately from Judaism,[25] and contains references to more than fifty people and events also found in the Bible including the creation narrative, Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, the Genesis flood narrative, Abraham, Sodom and Gomorrah, Moses and the Exodus, King David and the Jewish prophets. The New Testament, authored by Jews in Roman Judea, also influenced Islam. Additionally, the Qur'an mentions figures such as Jesus, Mary and John the Baptist. The dietary and legal codes of Islam, the basic design of the mosque, and the communal prayer services of Islam, including their devotional routines, are derived from Judaism.[25]

'Melting pot' approach

With the waves of Jewish aliyah in the 19th and 20th centuries, the existing culture was supplemented by the culture and traditions of the immigrant population. Zionism links the Jewish people to the Land of Israel, the homeland of the Jews between around 1200 BCE and 70 CE (end of the Second Temple era). However, modern Zionism evolved both politically and religiously.[26] Though Zionist groups were first competing with other Jewish political movements, Zionism became an equivalent to political Judaism during and after The Holocaust.

The first Israeli prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, led a trend to blend the many immigrants who, in the first years of the state, had arrived from Europe, North Africa, and Asia, into one 'melting pot' that would not differentiate between the older residents of the country, and the new immigrants. The original purpose was to unify the newer immigrants with the veteran Israelis, for the creation of a common Hebrew culture, and to build a new nation in the country.

Two central tools employed for this purpose were the Israel Defense Forces, and the education system. The Israel Defense Forces, by means of its transformation to a national army, would constitute a common ground among all civilians of the country, wherever they are. The education system, having been unified under Israeli law, enabled different students from different sectors to study together at the same schools. Gradually, Israeli society became more pluralistic, and the 'melting pot' declined over the years.

Some critics[who?] of the 'melting pot' consider it to have been a necessity in the first years of the state, in order to build a mutual society, but now claim that there is no longer a need for it. They instead see a need for Israeli society to enable people to express the differences, and the exclusivity, of every stream and sector. Others, mainly Mizrahi Jews who are more Shomer Masoret and the Holocaust survivors, have criticized the early 'melting pot' process. According to them, they were forced to give up or conceal their Jewish Masoret, and their diaspora heritage and culture, which they brought from their diaspora countries, and to adopt the new secular "Sabra" culture.

Today, cultural diversity is celebrated; many speak several languages, continue to eat the food of their cultural origins, and have mixed outlooks.[27]

Language

While Hebrew is the official language of the State of Israel, over 83 languages are spoken in the country.[28]

As new immigrants arrived, Hebrew language instruction was important. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, who founded the Hebrew Language Committee, coined thousands of new words and concepts based on Biblical, Talmudic and other sources, to cope with the needs and demands of life in the 20th century. Learning Hebrew became a national goal, employing the slogan "Yehudi, daber Ivrit" ("Jew—speak Hebrew"). Special schools for Hebrew language learning, ulpanim, were set up all over the country.[29]

The Hebraizing of family names was common in the pre-state period, and became more widespread in the 1950s. In the early years of the state, a pamphlet was published on how to choose a Hebrew name. The prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, urged anyone who represented the state in a formal capacity to adopt a Hebrew surname.[30]

Education

In 2012, Israel was named the second most educated country in the world, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)'s Education at a Glance report, released in 2012. The report found that 78% of the money invested in education is from public funds, and 45% of the population has a university or college diploma.[31]

Philosophy

Ancient Israel

Ancient Israeli philosophical ideas and approach can be found in the Bible.[34] Psalms contains invitations to admire the wisdom of God through his works; from this, some scholars suggest, Judaism harbors a Philosophical under-current.[35] The exegetical work of Psalm 132 stands between philosophy of language, and linguistic philosophy.[33]

Ecclesiastes is often considered to be the only genuine philosophical work in the Hebrew Bible; its author seeks to understand the place of human beings in the world, and life's meaning.[36] Ecclesiastes and the Book of Job were favorite works of medieval philosophers, who took them as philosophical discussions not dependent on historical revelation.[37] Ecclesiastes has had a deep influence on Western literature. It contains several phrases that have resonated in British and American culture, such as "eat, drink and be merry," "nothing new under the sun," "a time to be born and a time to die," and "vanity of vanities; all is vanity."[32]

In other books such as Proverbs or Sirach and Book of Wisdom of the Jewish apocrypha, there are references and praise to the concept of wisdom, which was to have a primordial significance for Jewish thought.[37]

Roman Judea

Philosophical speculation was not a central part of Rabbinic Judaism, although some have seen the Mishnah as a philosophical work.[38] Rabbi Akiva has also been viewed as a philosophical figure:[39] his statements include 1.) "How favored is man, for he was created after an image "for in an image, Elohim made man" (Gen. ix. 6); 2.) "Everything is foreseen; but freedom [of will] is given to every man"; 3.) "The world is governed by mercy... but the divine decision is made by the preponderance of the good or bad in one's actions". Like Philo,[40] who saw in the Hebrew construction of the infinitive with the finite form of the same verb and in certain particles (adverbs, prepositions, etc.) some deep reference to philosophical and ethical doctrines, Akiva perceived in them indications of many important ceremonial laws, legal statutes, and ethical teachings.[41][42]

A tannaitic tradition mentions that of the four who entered paradise, Akiva was the only one that returned unscathed.[41][43] This serves at least to show how strong in later ages was the recollection of Akiva's philosophical speculation[41] Akiva's anthropology is based upon the principle that man was created בצלם, that is, not in the image of God—which would be בצלם אלהים—but after an image, after a primordial type; or, philosophically speaking, after an Idea—what Philo calls in agreement with Judean theology, "the first heavenly man" (see Adam ḳadmon).

Modern Israel

Modern Israeli philosophy has been influenced by both secular and religious Jewish thought.

Martin Buber best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between the I–Thou relationship and the I–It relationship.[44] In I and Thou, Buber introduced his thesis on human existence; Ich‑Du is a relationship that stresses the mutual, holistic existence of two beings. It is a concrete encounter, because these beings meet one another in their authentic existence, without any qualification or objectification of one another. Even imagination and ideas do not play a role in this relation. In an I–Thou encounter, infinity and universality are made actual (rather than being merely concepts).[45] The Ich-Es ("I‑It") relationship is nearly the opposite of Ich‑Du.[45] Whereas in Ich‑Du the two beings encounter one another, in an Ich‑Es relationship the beings do not actually meet. Instead, the "I" confronts and qualifies an idea, or conceptualization, of the being in its presence and treats that being as an object. All such objects are considered merely mental representations, created and sustained by the individual mind.

Yeshayahu Leibowitz was an Orthodox Jew who held controversial views on the subject of halakha, or Jewish rabbinical law. He wrote that the sole purpose of religious commandments was to obey God, and not to receive any kind of reward in this world, or the world to come. He maintained that the reasons for religious commandments were beyond man's understanding, as well as irrelevant, and any attempt to attribute emotional significance to the performance of mitzvot was misguided, and akin to idolatry. The essence of Leibowitz's religious outlook is that a person's faith is his commitment to obey God, meaning God's commandments, and this has nothing to do with a person's image of God. This is a possibility, because Leibowitz thought that God cannot be described, that God's understanding is not man's understanding, and thus all the questions asked of God are out of place.[46] One result of this approach is that faith, which is a personal commitment to obey God, cannot be challenged by the usual philosophical problem of evil, or by historical events that seemingly contradict a divine presence. If a person stops believing after an awful event, it shows that he only obeyed God because he thought he understood God's plan, or because he expected to see a reward. But “for Leibowitz, religious belief is not an explanation of life, nature or history, or a promise of a future in this world or another, but a demand.”

Joseph Raz is a legal, moral, and political philosopher. Raz's first book, The Concept of a Legal System, was based on his doctoral thesis. A later book, The Morality of Freedom, develops a conception of perfectionist liberalism. Raz has argued for a distinctive understanding of legal commands as exclusionary reasons for action and for the "service conception" of authority, according to which those subject to an authority, "can benefit by its decisions only if they can establish their existence and content in ways which do not depend on raising the very same issues which the authority is there to settle."[47] This, in turn, supports Raz's argument for legal positivism, in particular "the sources thesis," "the idea that an adequate test for the existence and content of law must be based only on social facts, and not on moral arguments.".[47] Raz is acknowledged by his contemporaries as being one of the most important living legal philosophers. He has authored and edited eleven books to date, namely The Concept of a Legal System, Practical Reason and Norms, The Authority of Law, The Morality of Freedom, Authority, Ethics in the Public Domain, Engaging Reason, Value, Respect and Attachment, The Practice of Value, Between Authority and Interpretation, and From Normativity to Responsibility. In moral theory, Raz defends value pluralism and the idea that various values are incommensurable.

Other notable Israeli philosophers include Avishai Margalit, Hugo Bergmann, Yehoshua Bar-Hillel, Pinchas Lapide, Israel Eldad and Judea Pearl.

| Hillel the Elder (c. 110 BCE – 10 CE) |

Akiva ben Joseph (c. 50–135) |

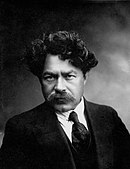

A. D. Gordon (1856–1922) |

Martin Buber (1878–1965) |

Hugo Bergmann (1883–1975) |

Yeshayahu Leibowitz (1903–1994) |

Joseph Raz (1939–2022) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Literature and poetry

Ancient Israel

The earliest known inscription in Hebrew is the Khirbet Qeiyafa Inscription (11th — 10th century BCE),[48] if it can indeed be considered Hebrew at that early a stage. This inscription is by far the most varied, extensive, and historically significant body of literature written in the old Classical Hebrew, and is the canon of the Hebrew Bible. The Bible is not a single, monolithic piece of literature, because each of these three sections, in turn, contains books written at different times by different authors,[49] written from the 8th to the 2nd century BCE. It is the primary source of ancient Israelite mythology, literature, philosophy and poetry. All books of the Bible are not strictly religious in nature; for example, The Song of Songs is a love poem, and, along with The Book of Esther, does not explicitly mention God.[50]

The Ketuvim sector of the Hebrew Bible is a collection of philosophical and artistic literature believed to have been written under the influence of Ruach ha-Kodesh (the Holy Spirit). The Book of Job, for instance, addressing the problem of theodicy – the vindication of the justice of God in the light of humanity's suffering[51] – it is a rich theological work setting out a variety of perspectives.[52] It has been widely and often extravagantly praised for its literary qualities, with Alfred, Lord Tennyson calling it "the greatest poem of ancient and modern times".[53]

Some content reflects historical events in ancient Israel such as the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah, the siege of Jerusalem, the Babylonian captivity and the Maccabean Revolt.

The Dead Sea scrolls are thousands of Jewish, predominantly Hebrew manuscripts, dated from the last three centuries BCE and from the first century CE.[54] The texts have great historical, religious, and linguistic significance, because they include the second-oldest known surviving manuscripts of works later included in the Hebrew Bible canon, along with deuterocanonical and extra-biblical manuscripts, which preserve evidence of the diversity of religious and philosophical thought in late Second Temple Judaism. Archaeologists have long associated the scrolls with the ancient Jewish sect called the Essenes, although some recent interpretations have challenged this connection, and argue that priests in Jerusalem, or Zadokites, or other unknown Jewish groups wrote the scrolls.[55][56]

Roman Judea

Post-Biblical Hebrew writings include early rabbinic works of Midrash and Mishnah. The Mishnah is the first major written redaction of the Jewish oral traditions known as the "Oral Torah". It is also the first major work of Rabbinic literature,[57][58] written in religious centers such as Yavneh, Lod and Bnei Brak, under the Roman occupation of Judea. It contains the oral traditions of the Pharisees from the Second Temple period particularly the period of the Tannaim. Most of the Mishnah is written in Mishnaic Hebrew, while some parts are in Jewish Aramaic.

The Jewish-Christian movement was formed in Judea of the early first-century. The books of the New Testament were all or nearly all written by Jewish Christians—that is, Jewish disciples of Jesus, during the first and early second centuries[59] Luke, who wrote the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts, is frequently thought of as an exception; scholars are divided as to whether Luke was a Gentile or a Hellenistic Jew.[60] The Gospels were written between 68 and 110 CE,[61][62][63][64] Acts between 95 and 110,[65] Epistles between 51 and 110 CE and Revelation in c. 95 CE.[62]

Josephus was a scholar, historian and hagiographer who was born in 37 CE in Jerusalem, Judea. He recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the first century CE and the First Jewish–Roman War, including the Siege of Masada. His most important works were The Jewish War (c. 75), Antiquities of the Jews (c. 94)[66] and Against Apion. The Jewish War recounts the Jewish revolt against Roman occupation (66–70). Antiquities of the Jews recounts the history of the world from a Jewish perspective for an ostensibly Roman audience. These works provide valuable insight into first century Judaism and the background of Early Christianity.[66]

Old Yishuv

Following the expulsion from Spain and Portugal many Jews settled in the Ottoman Empire including Palestine, contributing greatly to the culture of the Jewish community, especially in literature, poetry, philosophy and mysticism. The city of Safed was a center of a widespread spiritual and mystical activity. Joseph Karo, an author and kabbalist, settled in Safed in 1563. In safed he authored Shulchan Aruch, the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Judaism. Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz, a kabbalist and poet, settled in 1535 where he composed the Jewish poem Lecha Dodi. Isaac Luria (1534-1572), born in Jerusalem, was a foremost rabbi and Jewish mystic in the community of Safed. He is considered the father of contemporary Kabbalah,[67] his teachings being referred to as Lurianic Kabbalah. The works of his disciples compiled his oral teachings into writing. Every custom of his was scrutinized, and many were accepted, even against previous practice.[68]

Around 1550, Moses ben Jacob Cordovero founded a Kabbalah academy in Safed. Among his disciples were many of the luminaries of Safed, including Rabbi Eliyahu de Vidas, author of Reshit Chochmah ("Beginning of Wisdom"), and Rabbi Chaim Vital, who later became the official recorder and disseminator of the teachings of Rabbi Isaac Luria. Other kabbalists in the Land of Israel at that time were Isaiah Horowitz, Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, Abraham Azulai, Chaim ibn Attar, Shalom Sharabi, Chaim Yosef David Azulai and Abraham Gershon of Kitov.

Modern Israel

The first works of Hebrew literature in Israel were written by immigrant authors rooted in the world and traditions of European Jewry. Yosef Haim Brenner (1881–1921) and Shmuel Yosef Agnon (1888–1970), are considered by many to be the fathers of modern Hebrew literature.[7] Brenner, torn between hope and despair, struggled with the reality of the Zionist enterprise in the Land of Israel. Agnon, Brenner's contemporary, fused his knowledge of Jewish heritage with the influence of 19th and early 20th century European literature. He produced fiction dealing with the disintegration of traditional ways of life, loss of faith, and the subsequent loss of identity. In 1966, Agnon was co-recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature.[7]

Native-born writers who published their work in the 1940s and 1950s, often called the "War of Independence generation," brought a sabra mentality and culture to their writing. S. Yizhar, Moshe Shamir, Hanoch Bartov and Benjamin Tammuz vacillated between individualism and commitment to society and state. In the early 1960s, A.B. Yehoshua, Amos Oz, and Yaakov Shabtai broke away from ideologies to focus on the world of the individual, experimenting with narrative forms and writing styles such as psychological realism, allegory, and symbolism.

Since the 1980s and early 1990s, Israeli literature has been widely translated, and several Israeli writers have achieved international recognition.[7]

| Josephus (37 – c. 100) |

Joseph Karo (1488–1575) |

Hayim Nahman Bialik (1873–1934) |

Shaul Tchernichovsky (1875–1943) |

Shmuel Yosef Agnon (1888–1970) |

Rachel Bluwstein (1890–1931) |

Leah Goldberg (1911–1970) |

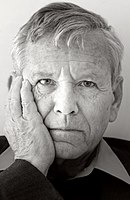

Amos Oz (1939–2018) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Science and technology

Ancient Israel

The early activity in science in ancient Israel can be found in the Hebrew Bible, where some of the books contain descriptions of the physical world. Biblical cosmology provides sporadic glimpses that may be stitched together to form a Biblical impression of the physical universe. There have been comparisons between the Bible, with passages such as from the Genesis creation narrative, and the astronomy of classical antiquity more generally.[69] The Old Testament also contains various cleansing rituals. One suggested ritual, for example, deals with the proper procedure for cleansing a leper (Leviticus 14:1–32). It is a fairly elaborate process, which is to be performed after a leper was already healed of leprosy (Leviticus 14:3), involving spiritual purity (the concepts of tumah and taharah), extensive physical cleansing, and personal hygiene, but also includes sacrificing a bird and lambs, with the addition of using their blood to symbolize that the afflicted has been cleansed. As with other purification ceremonies described in the Torah, cedar wood and the hyssop herb are also burnt during the ritual.

The Torah proscribes Intercropping (Lev. 19:19, Deut 22:9), a practice often associated with sustainable agriculture and organic farming in modern agricultural science.[70][71] The Mosaic code has provisions concerning the conservation of natural resources, such as trees (Deuteronomy 20:19–20) and birds (Deuteronomy 22:6–7).

Modern Israel

Israel is a developed and highly advanced country and ranks fifth among the most innovative countries in the Bloomberg Innovation Index.[73][74] Israel counts 140 scientists and technicians per 10,000 employees, one of the highest ratios in the world,[75] and 8,337 full-time equivalent researchers per million inhabitants.[76] It also has one of the highest per capita rates of filed patents.[77] Israel's high technology industry has benefited from both the country's highly educated and technologically skilled workforce coupled with the strong presence of foreign high-tech firms and sophisticated research centres.[78][76]

During the 1970s and 1980s Israel began developing the infrastructure needed for research and development in space exploration and related sciences. Israel launched its first satellite, Ofeq-1, from the locally built Shavit launch vehicle on September 19, 1988, and has made important contributions in a number of areas in space research, including laser communication, research into embryo development and osteoporosis in space, pollution monitoring, and mapping geology, soil and vegetation in semi-arid environments.[79] Israel is among the few countries capable of launching satellites into orbit and locally designed and manufactured satellites have been produced and launched by Israel Aerospace Industries(IAI), Israel's largest military engineering company, in cooperation with the Israel Space Agency. The AMOS-1 geostationary satellite began operations in 1996 as Israel's first commercial communications satellite. It was built primarily for direct-to-home television broadcasting, TV distribution and VSAT services. Further series of AMOS communications satellites (AMOS 2 – 5i) are operated or in development by the Spacecom Satellite Communications company, which provides satellite telecommunications services to countries in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.[80] Israel also develops, manufactures, and exports a large number of related aerospace products, including rockets and satellites, display systems, aeronautical computers, instrumentation systems, drones and flight simulators. Israel's second largest defense company is Elbit Systems, which makes electro-optical systems for air, sea and ground forces; drones; control and monitoring systems; communications systems and more.[81]

The growth in agricultural production is based on close cooperation of scientists, farmers and agriculture-related industries and has resulted in the development of advanced agricultural technology, water-conserving irrigation methods, anaerobic digestion, greenhouse technology, desert agriculture and salinity research.[82] Israeli companies also supply irrigation, water conservation and greenhouse technologies and know-how to other countries.[83][84][85] The modern technology of drip irrigation was invented in Israel by Simcha Blass and his son Yeshayahu. Their first experimental system was established in 1959 when company called Netafim was established. They developed and patented the first practical surface drip irrigation emitter.[86] This method was very successful and had spread to Australia, North America and South America by the late 1960s.

Israeli companies excel in computer software and hardware development, particularly computer security technologies, semiconductors and communications. Israeli firms include Check Point, a leading firewall firm; Amdocs, which makes business and operations support systems for telecoms; Comverse, a voice-mail company; and Mercury Interactive, which measures software performance.[88] A high concentration of high-tech industries in the coastal plain of Israel has led to the nickname Silicon Wadi (lit: "Silicon Valley").[89] More than 3,850 start-ups have been established in Israel, making it second only to the US in this sector[90] and has the largest number of NASDAQ-listed companies outside North America.[91] Optics, electro-optics, and lasers are significant fields and Israel produces fiber-optics, electro-optic inspection systems for printed circuit boards, thermal imaging night-vision systems, and electro-optics-based robotic manufacturing systems.[92] Research into robotics first began in the late 1970s, has resulted in the production of robots designed to perform a wide variety of computer aided manufacturing tasks, including diamond polishing, welding, packing, and building. Research is also conducted in the application of artificial intelligence to robots.[92]

Israeli scientists contributed many inventions and discoveries in a variety of fields including Joram Lindenstrauss (Johnson–Lindenstrauss lemma); Abraham Fraenkel (Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory); Shimshon Amitsur(Amitsur–Levitzki theorem); Saharon Shelah (Sauer–Shelah lemma); Elon Lindenstrauss (Ergodic theory); Nathan Rosen (Wormhole); Yuval Ne'eman (prediction of Quarks); Yakir Aharonov and David Bohm (Aharonov–Bohm effect); Jacob Bekenstein (formulation of Black holes Entropy); Dan Shechtman (discovery of quasicrystals); Avram Hershko and Aaron Ciechanover (discovery of the role of protein Ubiquitin); Arieh Warshel and Michael Levitt (development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems); Ariel Rubinstein (Rubinstein bargaining model); Moussa B.H. Youdim (Rasagiline); Robert Aumann (Game theory); Michael O. Rabin (Nondeterministic finite automaton); Amir Pnueli (Temporal logic); Judea Pearl (artificial intelligence); Shafi Goldwasser (Interactive proof system); Asher Peres (Quantum information); Adi Shamir (RSA, Differential cryptanalysis, Shamir's Secret Sharing); Yaakov Ziv and Abraham Lempel (Lempel–Ziv–Welch); Notable inventions include ReWalk, Given Imaging, Eshkol-Wachman movement notation, Taliglucerase alfa, USB flash drive, Intel 8088, Projection keyboard, TDMoIP, Mobileye, Waze, Wix.com, Gett, Viber, Uzi, Iron Dome, Arrow missile, Super-iron battery, Epilator.

| Abraham Fraenkel | Michael O. Rabin | Robert Aumann | Daniel Kahneman | Dan Shechtman | Ada Yonath |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Visual arts

From the beginning of the 20th century, visual arts in Israel have shown a creative orientation, influenced both by the West and East, as well as by the land itself, its development, the character of the cities, and stylistic trends emanating from art centers abroad. In painting, sculpture, photography, and other art forms, the country's varied landscape is the protagonist: the hill terraces and ridges produce special dynamics of line and shape; the foothills of the Negev, the prevailing grayish-green vegetation, and the clear luminous light result in distinctive color effects; and the sea and sand affect surfaces. On the whole, local landscapes, concerns, and politics lie at the center of Israeli art, and ensure its uniqueness.

The earliest Israeli art movement was the Bezalel school of the Ottoman and early Mandate period, when artists portrayed both Biblical and Zionist subjects in a style influenced by the European Art Nouveau movement, symbolism, and traditional Persian, Jewish, and Syrian artistry.

During the 1920s, the art scene saw a drastic shift with the growing influence of modern European art, chief among them the influence of the French Ecole de Paris on the Yishuv. Yitzhak Frenkel Frenel was the heralder of this movement and the first to teach in a modern style akin to the manner in France.[93][94] The first abstract painter in Israel,[95] he opened the Histadrut Art Studio in Tel Aviv (1926-1929).[96] Artists that learned under Frenkel such as Moshe Castel, Shimshon Holzman and others would venture to Paris themselves and return, increasing the influence of Paris on the early Israeli art scene.[93] At the same time, the Israeli art scene shifted from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv.[97] The latter, which became the center of Hebrew literature and theatre, was also the new center of modern art in the country (this expressed itself in the opening of Frenkel's art studio in Tel Aviv, as well as modern art exhibitions such as the Ohel's Modern Artists Exhibition).[98]

The city of Safed had a vibrant artists' quarter due to Safed's artistic appeal, drawing painters from all art movements to Safed during the summer up until the late 70s.[99] Today Israeli artists have ventured into Optical Art, digital art, AI art and more. Israel also has a vibrant street art scene; southern Tel Aviv is a hotspot of street Art culture.[100]

Symbols

Jewish various symbols are omnipresent in the culture of Israel. The Jewish diversity of Israel enrich the culture with a variety of traditions, symbols and handicrafts.

The national symbols of Israel are influenced by Jewish symbols and Jewish history to represent the country and its people.

Performance art

Music

Classical music in Israel has been vibrant since the 1930s, when hundreds of music teachers and students, composers, instrumentalists and singers, as well as thousands of music lovers, streamed into the country, driven by the threat of Nazism in Europe. Israel is also home to several world-class classical music ensembles, such as the Israel Philharmonic and the New Israeli Opera. The founding of The Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra (today the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra) in 1936 marked the beginning of Israel's classical music scene. In the early 1980s, the New Israeli Opera began staging productions, reviving public enthusiasm for operatic works. Russian immigration in the 1990s boosted the classical music arena with new talents, and music lovers.

The modern music scene in Israel spans the spectrum of musical genres, and often fuses many musical influences, ranging from Ethiopian, Middle-Eastern soul, rock, jazz, hip-hop, electronic, Arabic, pop and mainstream. Israeli music is versatile, and combines elements of both western and eastern music. It tends to be very eclectic, and contains a wide variety of influences from the Diaspora, as well as more modern cultural importations: Hassidic songs, Asian pop, Arab folk (especially by Yemenite singers), and Israeli hip hop or heavy metal. Also popular are various forms of electronic music, including trance, Hard trance, and Goa trance. Notable artists from Israel in this field are few, but include the psychedelic trance duo Infected Mushroom.

Dance

Traditional folk dances of Israel include the Horah and dances incorporating the Tza’ad Temani. Israeli folk dancing today is choreographed for recreational and performance dance groups.

Modern dance in Israel has won international acclaim. Israeli choreographers, among them Ohad Naharin and Barak Marshall, are considered among the most versatile and original international creators working today. Notable Israeli dance companies include the Batsheva Dance Company, the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company,[101] the Inbal Pinto & Avshalom Pollak Dance Company and the Kamea Dance Company. People come from all over Israel and many other nations for the annual dance festival in Karmiel, held in July. First held in 1988, the Karmiel Dance Festival is the largest celebration of dance in Israel, featuring three or four days and nights of dancing, with 5,000 or more dancers and a quarter of a million spectators in the capital of Galilee.[102][103] Begun as an Israeli folk dance event, the festivities now include performances, workshops, and open dance sessions for a variety of dance forms and nationalities.[104] Choreographer Yonatan Karmon created the Karmiel Dance Festival to continue the tradition of Gurit Kadman's Dalia Festival of Israeli dance, which ended in the 1960s.[105][106]

Famous companies and choreographers from all over the world have come to Israel to perform and give master classes. In July 2010, Mikhail Baryshnikov came to perform in Israel.[107]

Theatre

Roman Judea

During the Roman rule, some theaters were built in Judea, located in places such as Caesarea, Beth Shean and Jerusalem. The theater in Caesarea Maritima was built by Herod the Great and had a seating capacity of about 4000 seats in its final stage.[108] Another theater, in Bet Shean, was built in the end of the 2nd century CE with a capacity of 7000 seats.[109]

Modern Israel

The emergence of Hebrew theatre predated the state by nearly 50 years. The first amateur Hebrew theatre group was active in Ottoman Palestine from 1904 to 1914. The first professional Hebrew theatre, Habimah, was founded in Moscow in 1917, and moved to British Mandatory Palestine in 1931, where it became the country's national theatre.[110] The Ohel Theater was founded in 1925 as a workers' theatre that explored socialist and biblical themes. The first Hebrew plays revolved around pioneering.

After 1948, two major motifs were the Holocaust and the Arab-Israeli conflict. Moshe Shamir's He Walked in the Fields in 1949 was the first produced by a sabra writing about sabras in idiomatic and contemporary Hebrew. In the 1950s, dramatists portrayed the gap between pre-state dreams and disillusionment. Other plays pitted native Israelis against Holocaust survivors.[110] Beginning in the 1960s, Hanoch Levin wrote 56 plays and political satires. During the 1970s, Israeli theatre became more critical, contrasting extreme images of Israeli identity, such as the muscleman and the spiritual Jew. In the 1980s, Joshua Sobol explored Israeli-Jewish identity issues. Today, Israeli theatre is extremely diverse in content and style, and half of all plays are local productions.[110]

Other major theatre companies include the Cameri Theatre, Beit Lessin Theater, Gesher Theater (which performs in Hebrew and Russian), Haifa Theatre and Beersheba Theater.

Founded in 1980, The Acco Festival of Alternative Israeli Theatre is a four-day performing arts festival held annually in early autumn at the city of Acre. the festival became a symbol of coexistence between the city's Jewish and Arab inhabitants.

Cinema

Filmmaking in Israel has undergone major developments since its inception in the 1950s. The first features produced and directed by Israelis, such as "Hill 24 Doesn't Answer" and "They Were Ten", tended, like Israeli literature of the period, to be cast in the heroic mold. Some recent films remain deeply rooted in the Israeli experience, dealing with such subjects as Holocaust survivors and their children (Gila Almagor's "The Summer of Aviya" and its sequel, "Under the Domim Tree") and the travails of new immigrants ("Sh'hur", directed by Hannah Azoulai and Shmuel Hasfari, "Late Marriage" directed by Dover Koshashvili).

Others deal with issues of modern-day Israeli life, such as the Israeli-Arab conflict (Eran Riklis's "The Lemon Tree", Scandar Copti and Yaron Shani's "Ajami") and military service (Joseph Cedar's "Beaufort", Samuel Maoz's "Lebanon", Eytan Fox's "Yossi and Jagger"). Some are set in the context of a universalist, alienated, and hedonistic society (Eytan Fox's "A Siren's Song" and "The Bubble", Ayelet Menahemi and Nirit Yaron's "Tel Aviv Stories").

The Israeli film industry continues to gain worldwide recognition through International awards nominations. For three years consecutively, Israeli films (Beaufort (2008), Waltz with Bashir (2009) and Ajami (2010)) were nominated for Academy Awards. The Spielberg Film Archive at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem is the world's largest repository of film material on Jewish themes as well as on Jewish and Israeli life.[111]

The main international film festivals in Israel are the Jerusalem Film Festival and Haifa Film Festival.

Museums

With over 200 museums, Israel has the highest number of museums per capita in the world, with millions of visitors annually.[3]

Jerusalem's Israel Museum has a special pavilion showcasing the Dead Sea scrolls and a large collection of Jewish religious art, Israeli art, sculptures and Old Masters paintings. Newspapers appear in dozens of languages, and every city and town publishes a local newsletter.

Architecture

The old town of cities in Israel are composed of a variety of architectural styles, which is reflected in the synagogue architecture of Jewish quarters.

After 1850, the Jewish architecture began to open up to European influences, and tried to restore an ancient Biblical architecture. Notably, Mishkenot Sha'ananim was built, with inspiration from Mediterranean architecture. Until the 1920s, most structures are built in eclectic style and later, Modern architecture is further developed, notably in the "White City", known for its International Style.

The rural architecture of communities of kibbutzim and moshavim consist of small, white-walled houses with red roofs, and are a symbol of Israel.[112]

Cuisine

The heterogeneous nature of culture in Israel is also manifested in Israeli cuisine, a diverse combination of local ingredients and dishes, with diasporic dishes from around the world.[113] An Israeli fusion cuisine has developed, with the adoption and continued adaption of elements of various Jewish styles of cuisine including Mizrahi, Sephardic, Yemenite Jewish and Ashkenazi,[114] and many foods traditionally eaten in the Middle East.[115][116] Israeli cuisine is also influenced by geography, giving prominence to foods common in the Mediterranean region such as olives, chickpeas, dairy products, fish, and fresh fruits and vegetables. The main meal is usually lunch rather than dinner. Jewish holidays influence the cuisine, with many traditional foods served at holiday times. Shabbat dinner, eaten on Friday night, is a significant meal in a large proportion of Israeli homes. While not all Jews in Israel keep kosher, the observance of kashrut influences the menu in homes, public institutions and many restaurants.[113]

In 2013, an Israeli cookbook, Seafoodpedia, won "Best in World" in its category at the Gourmand World Cookbook Award in Paris, and Jerusalem: A Cookbook, published by the Israeli-Palestinian team of Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi, won "Best in the World" for Mediterranean Cuisine.[117]

-

Pastries in Jerusalem

-

Hummus, Fava beans and Tahini

-

Israeli wine brands

-

Breads in Mahane Yehuda market

Fashion

Israel has become an international center of fashion and design.[118] Tel Aviv has been called the “next hot destination” for fashion.[119] Israeli designers, such as swimwear company Gottex, show their collections at leading fashion shows, including New York's Bryant Park fashion show.[120] In 2011, Tel Aviv hosted its first Fashion Week since the 1980s, with Italian designer Roberto Cavalli as a guest of honor.[121]

Sports

Physical fitness received a boost in the 19th century from the physical culture campaign of Max Nordau. The Maccabiah Games, an Olympic-style event for Jewish athletes, was inaugurated in the 1930s, and has been held in Israel every four years since then.

In 1964, Israel hosted and won the AFC Asian Cup; in 1970, the Israel national football team managed to qualify to the FIFA World Cup, which is still considered the biggest achievement in Israeli football. Israel was excluded from the 1978 Asian Games due to Arab pressure, and since 1994 all Israeli sporting organizations now compete in Europe.

Football (soccer) and basketball are the most popular sports in Israel. The Israeli Premier League is the country's Premier Soccer League, and Ligat ha'Al is the premier basketball league. Maccabi Haifa, Maccabi Tel Aviv, Hapoel Tel Aviv and Beitar Jerusalem are the largest sports clubs. Maccabi Tel Aviv, Maccabi Haifa, and Hapoel Tel Aviv have competed in the UEFA Champions League, and Hapoel Tel Aviv reached the Quarterfinal in the UEFA Cup. Maccabi Tel Aviv B.C. has won the European Championship in basketball six times. Israeli tennis champion Shahar Pe'er peaked at 11th on the WTA rank list, a national record. Beersheba has become a national chess center; as a result of Soviet immigration, it is home to the largest number of chess grandmasters of any city in the world. The city hosted the World Team Chess Championship in 2005. Israeli chess teams won the silver medal at the 2008 Chess Olympiad and the bronze medal at the 2010 Chess Olympiad.[122] Israeli Grandmaster Boris Gelfand won the Chess World Cup 2009,[123] and played for the World Champion title in the World Chess Championship 2012.[124]

To date, Israel has won seven Olympic medals since its first win in 1992, including a gold medal in windsurfing at the 2004 Summer Olympics. Israel has won over 100 gold medals in the Paralympic Games, and is ranked about 15th in the All-time Paralympic Games medal table. The 1968 Summer Paralympics were hosted by Israel.

Youth movements

Youth movements were an important feature of Israel from its earliest days. In the 1950s, these movements were categorized in three groups: Zionist youth groups promoting social ideals and the importance of agricultural and communal settlement; working youth promoting educational goals and occupational advancement; and recreational groups with a strong emphasis on sports and leisure-time activities.[125]

Outdoor and vacation culture

Hiking in Israel, named tiyul, has been an integral part of Israeli culture, representing the Sabra ethos. First practiced by Zionist pioneers as a way to bond to the Land of Israel, it had become charged with much cultural significance.[126] Activities such as hiking during Jewish holidays (particularly Tu Bishvat) or backpacking on the Israel National trail, are part of israeli nationhood, culture, and history.[127] National parks and nature reserves across Israel register some 6.5 million visits a year. Schools and youth groups are taken on annual hiking trips throughout the country, raising children with an affinity for hiking and other outdoor activities. Consequently, many young Israelis take several months to a year off to travel the world, primarily to hike and experience the outdoors in remote, mountainous areas, such as Nepal, India, China, Chile, and Peru.

Along the 190 kilometres (120 mi) of the Israeli Mediterranean coast, two thirds are accessible to bathing activities. Israel has 100 surf bathing beaches, guarded by professional lifeguards.[128] Matkot is a popular paddle ball game similar to beach tennis, often referred to as the country's national sport.[129]

Wedding customs

All marriages between Jews in Israel are registered with the Chief Rabbinate, and the ceremony follows traditional Jewish practice.[130] Civil ceremonies are not performed in Israel,[131] although a growing number of secular couples circumvent this by traveling to nearby locations, such as Cyprus.[132] While some Jews in Israel have adopted Western styles of dress, traditional clothing and jewelry are sometimes brought out for pre-wedding rituals, including the Night of the Henna, which is a customary practice among Mizrahi Jews.[133]

See also

- Public holidays in Israel

- Heritage tourism

- Birthright Israel

- Israel Radio International

- Jerusalem March

- Kol Yisrael

- List of Israeli musical artists

- List of Israeli visual artists

- List of Hebrew language poets

- List of Hebrew language authors

- List of Israeli actors

- List of Hebrew language playwrights

- Media of Israel

- Religion in Israel

- Science and technology in Israel

- Start-up Nation

References

- ^ Linzen, Yael (25 April 2013). "Absolut bottle dedicated to Tel Aviv". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "The 10 Best Cities in Africa and the Middle East, According to Travel + Leisure Readers". Travel + Leisure. Retrieved 2024-08-20.

- ^ a b "Science & Technology". Consulate General of Israel in Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2007-04-16. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ "Israeli film wins award in Cannes Film Festival". Ynetnews. 25 May 2012. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ "Israeli wins best actress at Venice Film Festival – Israel Hayom". www.israelhayom.com. Archived from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ^ "Another Israeli film awarded in Berlin". Ynetnews. 17 February 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d "FOCUS on ISRAEL (Language)". www.focusmm.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-19. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ "Israel - Art, Music, Dance | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

- ^ "Break Dancing Across the Green Line". 26 April 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-02-21. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ^ a b c Marvin Perry (1 January 2012). Western Civilization: A Brief History, Volume I: To 1789. Cengage Learning. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-111-83720-4. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Harry Meyer Orlinsky (1960). Ancient Israel. Cornell University Press. pp. 144–. ISBN 0-8014-9849-X."It is to the prophetic tradition more than any other source that western civilization owes its noblest concept of the moral and social obligations of the individual human being"

- ^ Role of Judaism in Western culture and civilization Archived 2018-03-09 at the Wayback Machine, "Judaism has played a significant role in the development of Western culture because of its unique relationship with Christianity, the dominant religious force in the West". Judaism at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Andrea C. Paterson (2009). Three Monotheistic Faiths—Judaism, Christianity, Islam: An Analysis and Brief History. AuthorHouse. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-4343-9246-6. Archived from the original on 2020-07-29. Retrieved 2018-03-15."Judaism has influenced western civilization in a multitude of ways"

- ^ Cambridge University Historical Series, An Essay on Western Civilization in Its Economic Aspects, p.40: Hebraism, like Hellenism, has been an all-important factor in the development of Western Civilization; Judaism, as the precursor of Christianity, has indirectly had had much to do with shaping the ideals and morality of western nations since the christian era.

- ^ Max I. Dimont (1 June 2004). Jews, God, and History. Penguin Publisfhing Group. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-1-101-14225-7. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2018."During the subsequent five hundred years, under Persian, Greek and Roman domination, the Jews wrote, revised, admitted and canonized all the books now comprising the Jewish Old Testament"

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey; A Very Short History of the World; Penguin Books, 2004

- ^ Stephen Benko (1984). Pagan Rome and the Early Christians. Indiana University Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-253-34286-7. Archived from the original on 2019-06-27. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- ^ Doris L. Bergen (9 November 2000). Twisted Cross: The German Christian Movement in the Third Reich. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-0-8078-6034-2. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Catherine Cory (13 August 2015). Christian Theological Tradition. Routledge. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-1-317-34958-7. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Robinson 2000, p. 229

- ^ Esler. The Early Christian World. p. 157f.

- ^ Julie Galambush (14 June 2011). The Reluctant Parting: How the New Testament's Jewish Writers Created a Christian Book. HarperCollins. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-06-210475-5. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2018."The fact that Jesus and his followers who wrote the New Testament were first-century Jews, then, produces as many questions as it does answers concerning their experiences, beliefs, and practices"

- ^ BBC, BBC—Religion & Ethics—566, Christianity Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Prager, D; Telushkin, J. Why the Jews?: The Reason for Antisemitism. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983. pp. 110–26.

- ^ a b Dr. Andrea C. Paterson (21 May 2009). Three Monotheistic Faiths – Judaism, Christianity, Islam: An Analysis and Brief History. AuthorHouse. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-1-4520-3049-4. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2018."Judaism also contributed to the religion of Islam for Islam derives its ideas of holy text, the Qur'an, ultimately from Judaism. The dietary and legal codes of Islam are based on those of Judaism. The basic design of the mosque, the Islamic house of worship, comes from that of the early synagogues. The communal prayer services of Islam and their devotional routines resembles those of Judaism."

- ^ "Prof. Dr. Sergey V. Zagraevsky. The past, the present and the future of the Jewish nation / Sergei Zagraevski, Zagrajewski, Zagraewski, Zagraewsky, Sagrajewski, Zagraevskiy, סרגיי זגרייבסקי". www.zagraevsky.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ^ Lisa Owings, Israel, 2013, ABDO Publishing Company.

- ^ "Diverse cultures of Israel on screen.(Entertainment)". 26 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013.

- ^ "Culture in Israel". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 2016-11-29. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- ^ Neuman, Efrat (17 April 2014). "From the Archive—In the Name of Zionism, Change Your Name". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Haaretz (1 February 2012). "Israel Ranked Second Most Educated Country in the World, Study Shows". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ a b Hirsch, E.D. (2002). The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 8. ISBN 0618226478.

- ^ a b Stephen Breck Reid (2001). Psalms and Practice: Worship, Virtue, and Authority. Liturgical Press. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-0-8146-5080-6. Archived from the original on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- ^ "Jewish Philosophy and Philosophies of Judaism". www.myjewishlearning.co. Archived from the original on 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ "Medieval Philosophy and the Classical Tradition: In Islam, Judaism and Christianity" by John Inglis, Page 3

- ^ "Introduction to Philosophy" by Dr. Tom Kerns

- ^ a b "Jewish philosophy—philosophy". Archived from the original on 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ Jacob Neusner, Judaism as Philosophy

- ^ "Beginnings in Jewish Philosophy", By Meyer Levin, Pg 49, Behrman House 1971, ISBN 0-87441-063-0

- ^ Siegfried, Philo, p. 168

- ^ a b c

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "AKIBA BEN JOSEPH". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved Jan 23, 2017.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "AKIBA BEN JOSEPH". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved Jan 23, 2017.

Jewish Encyclopedia bibliography:- Frankel, Darke ha-Mishnah, pp. 111 Archived 2020-08-01 at the Wayback Machine-123;

- J. Brüll, Mebo ha-Mishnah, pp. 116 Archived 2020-08-01 at the Wayback Machine-122;

- Weiss, Dor, ii. 107 Archived 2016-03-11 at the Wayback Machine-118;

- H. Oppenheim, in Bet Talmud, ii. 237-246, 269-274;

- I. Gastfreund, Biographic des R. Akiba, Lemberg, 1871;

- J. S. Bloch, in Mimizraḥ u-Mima'arab, 1894, pp. 47-54;

- Grätz, Gesch. d. Juden, iv. (see index);

- Ewald, Gesch. d. Volkes Israel, vii. Archived 2021-02-21 at the Wayback Machine 367 Archived 2021-02-21 at the Wayback Machine et seq.;

- Derenbourg, Essai, pp. 329 Archived 2021-02-21 at the Wayback Machine-331, 395 Archived 2021-02-21 at the Wayback Machine et seq., 418 Archived 2021-02-21 at the Wayback Machine et seq.;

- Hamburger, R. B. T. ii. 32-43;

- Bacher, Ag. Tan. i. 271 Archived 2017-06-09 at the Wayback Machine-348;

- Jost, Gesch. des Judenthums und Seiner Sekten, ii. 59 et seq.;

- Landau, in Monatsschrift, 1854 Archived 2019-08-06 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 45-51 Archived 2017-01-31 at the Wayback Machine, 81-93 Archived 2017-01-19 at the Wayback Machine, 130-148 Archived 2017-01-31 at the Wayback Machine;

- Dünner, ibid. 1871 Archived 2019-08-06 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 451-454 Archived 2017-01-19 at the Wayback Machine;

- Neubürger, ibid. 1873 Archived 2019-08-06 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 385-397 Archived 2017-01-31 at the Wayback Machine, 433-445 Archived 2021-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, 529-536 Archived 2017-01-19 at the Wayback Machine;

- D. Hoffmann, Zur Einleitung in die Halachischen Midraschim, pp. 5 Archived 2017-06-08 at the Wayback Machine-12;

- Grätz, Gnosticismus, pp. 83 Archived 2020-07-29 at the Wayback Machine-120;

- F. Rosenthal, Vier Apokryph. Bücher . . . R. Akiba's, especially pp. 95-103, 124-131;

- S. Funk, Akiba (Jena Dissertation) Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, 1896;

- M. Poper, Pirḳe R. Akiba, Vienna, 1808;

- M. Lehmann, Akiba, Historische Erzählung, Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1880;

- J. Wittkind, Ḥuṭ ha-Meshulash, Wilna, 1877;

- Braunschweiger, Die Lehrer der Mischnah Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 92-110.

- ^ compare D. Hoffmann, Zur Einleitung, pp. 5–12, and H. Grätz, Gesch. iv. 427)

- ^ Ḥag. 14b; Tosef., Ḥag. ii. 3

- ^ "Buber", Island of freedom, archived from the original on 2019-05-16, retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ a b Kramer, Kenneth; Gawlick, Mechthild (November 2003). Martin Buber's I and thou: practicing living dialogue. Paulist Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8091-4158-6. Archived from the original on 2020-07-29. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ Zev Golan, "God, Man and Nietzsche: A Startling Dialogue between Judaism and Modern Philosophers" (New York: iUniverse, 2008), p. 43

- ^ a b Green, Leslie (1 January 2012). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2017 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ "Most ancient Hebrew biblical inscription deciphered". newmedia-eng.haifa.ac.il. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2016-09-22. University of Haifa press release.

- ^ Riches, John (2000). The Bible: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-19-285343-1.

the biblical texts themselves are the result of a creative dialogue between ancient traditions and different communities through the ages

- ^ "The Book of Esther Doesn't Mention God, Why is It in the Bible?". Discoverymagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-25. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ Lawson 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Seow 2013, p. 87.

- ^ Seow 2013, p. 74.

- ^ "The Digital Library: Introduction". Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library. Archived from the original on 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ^ Ofri, Ilani (13 March 2009). "Scholar: The Essenes, Dead Sea Scroll 'authors,' never existed". Ha'aretz. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Golb, Norman (5 June 2009). "On the Jerusalem Origin of the Dead Sea Scrolls" (PDF). University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ The list of joyful days known as Megillat Taanit is older, but according to the Talmud it is no longer in force.

- ^ "Commentary on Tractate Avot with an Introduction (Shemona perakim)". World Digital Library. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Powell (2009), p. 16

- ^ Strelan, Rick (2013). Luke the Priest: The Authority of the Author of the Third Gospel. Farnham, ENG: Routledege-Ashgate. pp. 102–105.

- ^ Duling 2010, p. 298-299.

- ^ a b Perkins 2012, p. 19ff.

- ^ Charlesworth 2008, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 587.

- ^ a b Harris 1985.

- ^ Eisen, Yosef (2004). Miraculous journey : a complete history of the Jewish people from creation to the present (Rev. ed.). Southfield, Mich.: Targum/Feldheim. p. 213. ISBN 1568713231. Archived from the original on 2021-02-21. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- ^ "The Essence". Archived from the original on 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Kurtz, J. H., and T. D. Simonton. The Bible and Astronomy; An Exposition of the Biblical Cosmology, and Its Relations to Natural Science. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1857.

- ^ Andrews, D.J., A.H. Kassam. 1976. The importance of multiple cropping in increasing world food supplies. pp. 1-10 in R.I. Papendick, A. Sanchez, G.B. Triplett (Eds.), Multiple Cropping. ASA Special Publication 27. American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI.

- ^ Risch, Stephen J.; Hansen, Michael K. (1982). "Plant Growth, Flowering Phenologies, and Yields of Corn, Beans and Squash Grown in Pure Stands and Mixtures in Costa Rica". Journal of Applied Ecology. 19 (3): 901–916. Bibcode:1982JApEc..19..901R. doi:10.2307/2403292. JSTOR 2403292.

- ^ Levi Julian, Hana (3 September 2012). "'40 Years of Black Hole Thermodynamics' in Jerusalem". Arutz Sheva. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ "The Bloomberg Innovation Index". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ David Shamah (4 February 2015). "Bloomberg: Israel Is World's 5th Most Innovative Country, Ahead Of US, UK". No Camels. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ Shteinbuk, Eduard (22 July 2011). "R&D and Innovation as a Growth Engine" (PDF). National Research University – Higher School of Economics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b Getz, Daphne; Tadmor, Zehev (2015). Israel. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 409–429. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ Karr, Steven (24 October 2014). "Imagine a World Without Israel—Part 2". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ "Business Opportunities By Sector". Israeli Embassy. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Israeli Space Research Archived 2016-12-03 at the Wayback Machine by Wendy Elliman, in Jewish Virtual Library Archived 2017-01-16 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 5 December 2009

- ^ "Spacecom Coverage maps". AMOS-Spacecom.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ Coren, Ora (18 September 2009). "The wars that make and break". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Israel: Waterworks for the World?". Bloomberg Businessweek. 29 December 2005. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Agrotechnology Company Directory Archived 2018-01-28 at the Wayback Machine in The Israel Export and International Cooperation Institute Archived 2016-12-09 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-12-02

- ^ Kloosterman, Karin (3 May 2009). "Israeli company offers liquid know-how to India". ISRAEL21c. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Kloosterman, Karin (4 February 2009). "Out of Israel to Africa". ISRAEL21c. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "A Kibbutz-based MNC". www.SFU.ca. Archived from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ King, Ian (9 April 2007). "How Israel saved Intel". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ Kalman, Matthew (2 April 2004). "Venture capital invests in Israeli techs / Recovering from recession, country ranks behind only Boston, Silicon Valley in attracting cash for startups". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Fontenay, Catherine de; Carmel, Erran (June 2002). "Israel's Silicon Wadi: The forces behind cluster formation". Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ Senor and Singer, Start-up Nation: The Story of Israel's Economic Miracle

- ^ Kedem, Assaf (6 February 2005). "NASDAQ Appoints Asaf Homossany as New Director for Israel". NASDAQ OMX Group. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ a b "SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY: Industrial R&D". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ a b "1884 | Encyclopedia of the Founders and Builders of Israel". www.tidhar.tourolib.org. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ "Schule von Paris – Wikipedia – Enzyklopädie". wiki.edu.vn (in German). Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ "יצחק פרנקל: "חיבור ללא עצמים"". המחסן של גדעון עפרת (in Hebrew). 2011-01-01. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ Izen, Shai (5 September 1927). "In the exhibition of the Studio for Art in Tel Aviv". Davar. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ Hecht Museum (2013). After the School Of Paris (in English and Hebrew). Israel. ISBN 9789655350272.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ofrat, Gideon (23 November 1979). "Enough with all the Frenkels!". Haaretz. pp. 28, 29, 30.

- ^ Hecht Museum (2013). After the School Of Paris (in English and Hebrew). Israel. ISBN 9789655350272.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Constantinoiu, Marina (2017-03-26). "Israeli street art: Not just writing on the wall". ISRAEL21c. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ^ "Israeli Dance". Archived from the original on 2010-01-28. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ "Galilee—Culture". Galilee Development Authority. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ "Karmiel Dance Festival". ACTCOM-Active Communication Ltd. Archived from the original on 2007-08-12. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ "Karmiel Dance Festival". Karmiel Dance Festival. Archived from the original on 2007-08-19. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ "In Israel, Still Dancing After All These Years". Forward Association, inc. 2004-04-16. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ "Gurit Kadman". PhantomRanch.net. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ "Mikhail Baryshnikov and Ana Laguna to Perform in Israel". 24 June 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Roman Theatre". www.lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 2018-02-07. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ^ "Bet Shean National Park, Israel Nature and Parks Authority". Archived from the original on 2018-02-07. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ^ a b c "Israeli Theatre: A culmination of foreign and native influences". Archived from the original on 2011-03-10. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ "Israeli Culture: Cinema". Archived from the original on 2013-06-21. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ^ "The Israel Briefing Book: Architecture".

- ^ a b "Characteristics of Israeli Cuisine". Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- ^ Gold, Rozanne (20 July 1994). "A Region's Tastes Commingle in Israel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-09-17. Retrieved 2017-02-15.

- ^ Roden, The Book of Jewish Food, pp 202-207

- ^ Gur,The Book of New Israeli Food

- ^ "Israeli cuisine is having a moment". CBS News. Archived from the original on 2013-03-03. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ^ What’s New in Tel Aviv Archived 2008-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, by David Kaufman, March 2008.

- ^ Promoting Israel in a Downturn[permanent dead link], David Saranga, 17 December 2008

- ^ Fashion Week: Gottex[permanent dead link], 9 September 2008.

- ^ Merle Ginsberg (2011-11-21). "Roberto Cavalli Shows Spring 2012 Collection at First Ever Tel Aviv Fashion Week". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 2011-11-25. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Bartelski, Wojciech. "OlimpBase :: the encyclopaedia of team chess". www.olimpbase.org. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- ^ "World Cup final: Gelfand beats Ponomariov to win the Cup". ChessBase News. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "WCh Tiebreak: Anand draws final game, retains title!". ChessBase News. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Eisenstadt, S. N. (13 May 2018). "Youth, Culture and Social Structure in Israel". The British Journal of Sociology. 2 (2): 105–114. doi:10.2307/587382. ISSN 0007-1315. JSTOR 587382.

- ^ Israeli Backpackers: From Tourism to Rite of Passage. Chaim Noy, Erik Cohen. SUNY Press, 01 Feb 2012

- ^ "Why Do People Hike? Hiking the Israel National Trail". Noga Collins‐Kreiner and Nurit Kliot. 27 February 2017. doi:10.1111/tesg.12245

- ^ Hartmann, Daniel (13 May 2018). "Drowning and Beach-Safety Management (BSM) along the Mediterranean Beaches of Israel: A Long-Term Perspective". Journal of Coastal Research. 22 (6): 1505–1514. JSTOR 30138414.

- ^ Fogelman, Shay (2009-07-12). "Beach Paddle Battle". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2009-08-04. Retrieved 2011-05-17.

- ^ "How Do Jewish Weddings and Marriage Work?". Archived from the original on 2011-10-19. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ^ "Israelis seeking alternatives to traditional wedding ceremonies". 21 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ^ "Israelis turn to secular weddings". 13 February 2005. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Dress Codes: Revealing the Jewish Wardrobe" Archived 2014-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, An exhibition focusing on this collection was presented at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem March 11, 2014-October 18, 2014

Works cited

- Boring, M. Eugene (1 January 2012). An Introduction to the New Testament: History, Literature, Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25592-3.

- Charlesworth, Prof James H. (1 January 2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-2475-6.

- Duling, Dennis C. (22 January 2010). "The Gospel of Matthew". In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to The New Testament. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-1894-4.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1985). Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto, California: Mayfield.

- Lawson, Steven J. (2005). Holman Old Testament Commentary Volume 10 - Job. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8054-9470-9.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2005). Gospel According to St John: Black's New Testament Commentaries. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-8822-9.

- Perkins, Pheme (2012). Reading the New Testament: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4786-1.

- Powell, Mark A. (2009). Introducing the New Testament: A Historical, Literary, and Theological Survey. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-2868-7.

- Robinson, John A. T. (2000) [1976]. Redating the New Testament. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57910-527-3.

- Seow, C. L. (4 July 2013). Job 1 - 21: Interpretation and Commentary. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4895-6.