Serbs

| Total population | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

c. 10 million*

| |||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||

| Other regions | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||

| Serbian | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||

| Predominantly Eastern Orthodoxy (Serbian Orthodox Church)[27] | |||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||

| South Slavs | |||||||||||||||

* The total figure is merely an estimation; sum of all the referenced populations. **Some 265,895 (or 42.88% of Montenegro's total population) declared Serbian language as their mother tongue.[28] | |||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

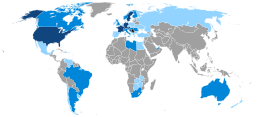

The Serbs (Serbian Cyrillic: Срби, romanized: Srbi, pronounced [sr̩̂bi]) are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history, and language.[29][30][31][32] They primarily live in Serbia, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro as well as in North Macedonia, Slovenia, Germany and Austria. They also constitute a significant diaspora with several communities across Europe, the Americas and Oceania.[33][34]

The Serbs share many cultural traits with the rest of the peoples of Southeast Europe. They are predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christians by religion. The Serbian language (a standardized version of Serbo-Croatian) is official in Serbia, co-official in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and is spoken by the plurality in Montenegro.

Ethnology

The identity of Serbs is rooted in Eastern Orthodoxy and traditions. In the 19th century, the Serbian national identity was manifested,[35] with awareness of history and tradition, medieval heritage, cultural unity, despite living under different empires.[citation needed] Three elements, together with the legacy of the Nemanjić dynasty, were crucial in forging identity and preservation during foreign domination: the Serbian Orthodox Church, the Serbian language, and the Kosovo Myth.[36] When the Principality of Serbia gained independence from the Ottoman Empire, Orthodoxy became crucial in defining the national identity, instead of language which was shared by other South Slavs (Croats and Bosniaks).[37] The tradition of slava, the family saint feast day, is an important ethnic marker of Serb identity,[38] and is usually regarded their most significant and most solemn feast day.[39]

The origin of the ethnonym is unclear. The most prominent theory considers it of Proto-Slavic origin. Hanna Popowska-Taborska argued native Slavic provenance of the ethnonym,[40] claiming that the theory advances a conclusion that the ethnonym has a meaning of a family kinship or alliance, which was also argued by a number of other scholars.[41]

Genetic origins

According to a triple analysis – autosomal, mitochondrial and paternal — of available data from large-scale studies on Balto-Slavs and their proximal populations, the whole genome SNP data situates Serbs with Montenegrins in between two Balkan clusters.[42] Y-DNA results show that haplogroups I2a and R1a together stand for the majority of the makeup, with more than 50 percent.[43][44]

According to several recent studies Serbia's people are among the tallest in the world,[45] with an average male height of 1.82 metres (6 ft 0 in).[46][47]

History

Arrival of the Slavs

Early Slavs, especially Sclaveni and Antae, including the White Serbs, invaded and settled Southeastern Europe in the 6th and 7th century.[48] Up until the late 560s, their activity was raiding, crossing from the Danube, though with limited Slavic settlement mainly through Byzantine foederati colonies.[49] The Danube and Sava frontier was overwhelmed by large-scale Slavic settlement in the late 6th and early 7th century.[50] What is today central Serbia was an important geo-strategical province, through which the Via Militaris crossed.[51] This area was frequently intruded by barbarians in the 5th and 6th centuries.[51] The numerous Slavs mixed with and assimilated the descendants of the indigenous population (Illyrians, Thracians, Dacians, Romans, Celts).[52] White Serbs from White Serbia came to an area near Thessaloniki and then they settled area between Dinaric Alps and Adriatic coast.[53] The region of "Rascia" (Raška) was the center of Serb settlement and Serb tribes also occupied parts of modern-day Herzegovina and Montenegro.[54] Prior to their arrival to the Balkans, early Slavs were predominantly involved in agriculture, which is why they settled in areas which were cultivated even during Roman times.[55]

Middle Ages

The first Serb states, Serbia (780–960) and Duklja (825–1120), were formed chiefly under the Vlastimirović and Vojislavljević dynasties respectively.[56][57] The other Serb-inhabited lands, or principalities, that were mentioned included the "countries" of Paganija, Zahumlje, Travunija.[58][59] With the decline of the Serbian state of Duklja in the late 11th century, Raška separated from it and replaced it as the most powerful Serbian state.[60] Prince Stefan Nemanja (r. 1169–96) conquered the neighbouring territories of Kosovo, Duklja and Zachlumia. The Nemanjić dynasty ruled over Serbia until the 14th century. Nemanja's older son, Stefan Nemanjić, became Serbia's first recognized king, while his younger son, Rastko, founded the Serbian Orthodox Church in the year 1219, and became known as Saint Sava after his death.[61] Parts of modern-day Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and central Serbia would come under the control of Nemanjić.[62]

Over the next 140 years, Serbia expanded its borders, from numerous smaller principalities, reaching to a unified Serbian Empire. Its cultural model remained Byzantine, despite political ambitions directed against the empire. The medieval power and influence of Serbia culminated in the reign of Stefan Dušan, who ruled the state from 1331 until his death in 1355. Ruling as Emperor from 1346, his territory included Macedonia, northern Greece, Montenegro, and almost all of modern Albania.[63] When Dušan died, his son Stephen Uroš V became Emperor.[64]

With Turkish invaders beginning their conquest of the Balkans in the 1350s, a major conflict ensued between them and the Serbs, the first major battle was the Battle of Maritsa (1371),[64] in which the Serbs were defeated.[65] With the death of two important Serb leaders in the battle, and with the death of Stephen Uroš that same year, the Serbian Empire broke up into several small Serbian domains.[64] These states were ruled by feudal lords, with Zeta controlled by the Balšić family, Raška, Kosovo and northern Macedonia held by the Branković family and Lazar Hrebeljanović holding today's Central Serbia and a portion of Kosovo.[65] Hrebeljanović was subsequently accepted as the titular leader of the Serbs because he was married to a member of the Nemanjić dynasty.[64] In 1389, the Serbs faced the Ottomans at the Battle of Kosovo on the plain of Kosovo Polje, near the town of Priština.[65] Both Lazar and Sultan Murad I were killed in the fighting.[65] The battle most likely ended in a stalemate, and afterwards Serbia enjoyed a short period of prosperity under despot Stefan Lazarević and resisted falling to the Turks until 1459.[65]

Early modern period

The Serbs had taken an active part in the wars fought in the Balkans against the Ottoman Empire, and also organized uprisings;[66][67] because of this, they suffered persecution and their territories were devastated – major migrations from Serbia into Habsburg territory ensued.[68] After allied Christian forces had captured Buda from the Ottoman Empire in 1686 during the Great Turkish War, Serbs from Pannonian Plain (present-day Hungary, Slavonia region in present-day Croatia, Bačka and Banat regions in present-day Serbia) joined the troops of the Habsburg monarchy as separate units known as Serbian Militia.[69] Serbs, as volunteers, massively joined the Austrian side.[70]

Many Serbs were recruited during the devshirme system, a form of slavery in the Ottoman Empire, in which boys from Balkan Christian families were forcibly converted to Islam and trained for infantry units of the Ottoman army known as the Janissaries.[71][72][73][74] A number of Serbs who converted to Islam occupied high-ranking positions within the Ottoman Empire, such as Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha and Minister of War field marshal Omar Pasha Latas.

In 1688, the Habsburg army took Belgrade and entered the territory of present-day Central Serbia. Louis William, Margrave of Baden-Baden called Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević to raise arms against the Turks; the Patriarch accepted and returned to the liberated Peć. As Serbia fell under Habsburg control, Leopold I granted Arsenije nobility and the title of duke. In early November, Arsenije III met with Habsburg commander-in-chief, General Enea Silvio Piccolomini in Prizren; after this talk he sent a note to all Serb bishops to come to him and collaborate only with Habsburg forces.

A Great Migration of the Serbs (1690) to Habsburg lands was undertaken by Patriarch Arsenije III.[75] The large community of Serbs concentrated in Banat, southern Hungary and the Military Frontier included merchants and craftsmen in the cities, but mainly refugees that were peasants.[75] Smaller groups of Serbs also migrated to the Russian Empire, where they occupied high positions in the military circles.[76][77][78]

The Serbian Revolution for independence from the Ottoman Empire lasted eleven years, from 1804 until 1815.[79] The revolution comprised two separate uprisings which gained autonomy from the Ottoman Empire that eventually evolved towards full independence (1835–1867).[80][81] During the First Serbian Uprising, led by Duke Karađorđe Petrović, Serbia was independent for almost a decade before the Ottoman army was able to reoccupy the country. Shortly after this, the Second Serbian Uprising began. Led by Miloš Obrenović, it ended in 1815 with a compromise between Serbian revolutionaries and Ottoman authorities.[82] Likewise, Serbia was one of the first nations in the Balkans to abolish feudalism.[83] Serbs are among the first ethnic groups in Europe to form a nation and a clear sense of national identity.[84]

Modern period

In the early 1830s, Serbia gained autonomy and its borders were recognized, with Miloš Obrenović being recognized as its ruler. Serbia is the fourth modern-day European country, after France, Austria and the Netherlands, to have a codified legal system, as of 1844.[85] The last Ottoman troops withdrew from Serbia in 1867, although Serbia's and Montenegro's independence was not recognized internationally until the Congress of Berlin in 1878.[68]

Serbia fought in the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, which forced the Ottomans out of the Balkans and doubled the territory and population of the Kingdom of Serbia. In 1914, a young Bosnian Serb student named Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, which directly contributed to the outbreak of World War I.[86] In the fighting that ensued, Serbia was invaded by Austria-Hungary. Despite being outnumbered, the Serbs defeated the Austro-Hungarians at the Battle of Cer, which marked the first Allied victory over the Central Powers in the war.[87] Further victories at the battles of Kolubara and the Drina meant that Serbia remained unconquered as the war entered its second year. However, an invasion by the forces of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria overwhelmed the Serbs in the winter of 1915, and a subsequent withdrawal by the Serbian Army through Albania took the lives of more than 240,000 Serbs. Serb forces spent the remaining years of the war fighting on the Salonika front in Greece, before liberating Serbia from Austro-Hungarian occupation in November 1918.[88] Serbia suffered the biggest casualty rate in World War I.[89]

Following the victory in WWI, Serbs subsequently formed the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes with other South Slavic peoples. The country was later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and was led from 1921 to 1934 by King Alexander I of the Serbian Karađorđević dynasty.[90] During World War II, Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers in April 1941. The country was subsequently divided into many pieces, with Serbia being directly occupied by the Germans.[91] Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) were targeted for extermination as part of genocide by the Croatian ultra-nationalist, fascist Ustaše.[92][93][94][95] The Ustaše view of national and racial identity, as well as the theory of Serbs as an inferior race, was under the influence of Croatian nationalists and intellectuals from the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.[96][97][98] Jasenovac camp was notorious for the barbaric practices which occurred in it.[93] Sisak and Jastrebarsko concentration camp were specially formed for children.[99][100][101] Serbs in the NDH suffered among the highest casualty rates in Europe during the World War II, while the NDH was one of the most lethal regimes in the 20th century.[102][103][104] Diana Budisavljević, a humanitarian of Austrian descent, carried out rescue operations from Ustaše camps and saved more than 15,000 children, mostly Serbs.[105][106]

More than half a million Serbs were killed in the territory of Yugoslavia during World War II. Serbs in occupied Yugoslavia subsequently formed a resistance movement known as the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland, or the Chetniks. The Chetniks had the official support of the Allies until 1943, when Allied support shifted to the Communist Yugoslav Partisans, a multi-ethnic force, formed in 1941, which also had a large majority of Serbs in its ranks in the first two years of war. Over the entirety of the war, the ethnic composition of the Partisans was 53 percent Serb.[107][108] During the entire course of the WWII in Yugoslavia, 64.1% of all Bosnian Partisans were Serbs.[109] Later, after the fall of Italy in September 1943, other ethnic groups joined Partisans in larger numbers.[91]

At the end of the war, the Partisans, led by Josip Broz Tito, emerged victorious. Yugoslavia subsequently became a Communist state. Tito died in 1980, and his death saw Yugoslavia plunge into economic turmoil.[110] Yugoslavia disintegrated in the early 1990s, and a series of wars resulted in the creation of five new states. The heaviest fighting occurred in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, whose Serb populations rebelled and declared independence. The war in Croatia ended in August 1995, with a Croatian military offensive known as Operation Storm put a stop to the Croatian Serb rebellion and causing as many as 200,000 Serbs to flee the country. The Bosnian War ended that same year, with the Dayton Agreement dividing the country along ethnic lines. In 1998–99, a conflict in Kosovo between the Yugoslav Army and Albanians seeking independence erupted into full-out war, resulting in a 78-day-long NATO bombing campaign which effectively drove Yugoslav security forces from Kosovo.[111] Subsequently, more than 200,000 Serbs and other non-Albanians fled the province.[112] On 5 October 2000, Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosević was overthrown in a bloodless revolt after he refused to admit defeat in the 2000 Yugoslav general election.[113]

Demographics

Modern demographic distribution of ethnic Serbs throughout homeland and native regions, as well as in Serbian ethnic diaspora, represents an outcome of several historical and demographic processes, shaped both by economic migrations and forced displacements during the recent Yugoslav Wars (1991–1999).

Balkans

According to most recent census conducted in Serbia, Croatia and Montenegro, there are nearly 7 million Serbs living in their native homelands, within the geographical borders of former Yugoslavia. In Serbia itself, around 5.5 million people identify themselves as ethnic Serbs, and constitute about 83% of the population. More than a million live in Bosnia and Herzegovina (predominantly in the Republika Srpska), where they are one of the three constituent ethnic groups. Serbs in Croatia, Montenegro and North Macedonia also have recognized collective rights, and number some 186,000, 178,000 and 39,000 people, respectively, while another estimated 96,000 live in the disputed area of Kosovo.[4] Smaller minorities exist in Slovenia, some 36,000 people, respectively.

Outside of the former Yugoslavia, but within their historical and migratory areal, Serbs are officially recognized as national minority in Albania,[114] Romania (18,000), Hungary (7,000), as well as in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Diaspora

There are over 2 million Serbs in diaspora throughout the world; some sources put that figure as high as 4 million.[115] There is a large diaspora in Western Europe, particularly in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Italy, Sweden and United Kingdom. Outside Europe, there are significant Serb communities in the United States, Canada, Australia, South America and Southern Africa. The existence of a large diaspora is mainly a consequence of either economic or political (coercion or expulsions) reasons. There were several waves of Serb emigration:

- The first wave took place since the end of the 19th century and lasted until World War II and was caused by economic reasons; particularly large numbers of Serbs (mainly from peripheral ethnic areas such as Herzegovina, Montenegro, Dalmatia, and Lika) emigrated to the United States.

- The second wave took place after the end of World War II. At this time, members of royalist Chetniks and other political opponents of communist regime fled the country mainly going overseas (United States and Australia) and, to a lesser degree, United Kingdom.

- The third wave, by far the largest, consisted of economic emigration beginning in the 1960s when several Western European countries signed bilateral agreements with Yugoslavia, allowing the recruitment of industrial workers to those countries; this lasted until the end of the 1980s. The major destinations for migrants were West Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, and to a lesser extent France and Sweden. That generation of diaspora is collectively known as gastarbajteri, after German gastarbeiter ("guest-worker"), since most of the emigrants headed for German-speaking countries. These migrations left some parts of Serbia sparsely populated.[116]

- Later emigration took place during the 1990s, and was caused by both political and economic reasons. The Yugoslav wars caused many Serbs from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to leave their countries in the first half of the 1990s. The economic sanctions imposed on Serbia caused an economic collapse with an estimated 300,000 people leaving Serbia during that period, 20% of which had a higher education.[117][118]

Language

Serbs speak Serbian, a member of the South Slavic group of languages, specifically the Southwestern group. Standard Serbian is a standardized variety of Serbo-Croatian, and therefore mutually intelligible with Standard Croatian, Standard Montenegrin, and Standard Bosnian (see Comparison of standard Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian), which are all based on the Shtokavian dialect.[119]

Serbian is an official language in Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina and is a recognized minority language in Montenegro (although spoken by a plurality of population), Croatia, North Macedonia, Romania, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia. Older forms of literary Serbian are Church Slavonic of the Serbian recension, which is still used for ecclesiastical purposes, and Slavonic-Serbian—a mixture of Serbian, Church Slavonic and Russian used from the mid-18th century to the first decades of the 19th century.

Serbian has active digraphia, using both Cyrillic and Latin alphabets.[121] Serbian Cyrillic was devised in 1814 by Serbian linguist Vuk Karadžić, who created the alphabet on phonemic principles.[122] Serbian Latin was created by Ljudevit Gaj and published in 1830. His alphabet mapped completely on Serbian Cyrillic which had been standardized by Vuk Karadžić a few years before.[123]

Loanwords in the Serbian language besides common internationalisms are mostly from Greek,[124] German[125] and Italian,[126] while words of Hungarian origin are present mostly in the north.

The Ottoman conquest began a linguistical contact between Ottoman Turkish and South Slavic; Ottoman Turkish influence grew stronger after the 15th century.[127] Besides Turkish loanwords, also many Arabic (such as alat, "tool", sat, "hour, clock") and Persian (čarape, "socks", šećer, "sugar") words entered via Turkish, called "Orientalisms" (orijentalizmi).[127] Also, many Greek words entered via Turkish.[127] Words for hitherto unknown sciences, businesses, industries, technologies and professions were brought by the Ottoman Empire.[127] Christian villagers brought urban vocabulary from their travels to Islamic culture cities.[128] Many Turkish loanwords are no longer considered loanwords.[129]

There is considerable usage of French words as well, especially in military related terms.[125] One Serbian word that is used in many of the world's languages is "vampire" (vampir).[130][131][132][133]

Culture

Literature, icon painting, music, dance and medieval architecture are the artistic forms for which Serbia is best known. Traditional Serbian visual art (specifically frescoes, and to some extent icons), as well as ecclesiastical architecture, are highly reflective of Byzantine traditions, with some Mediterranean and Western influence.[134]

Many Serbian monuments and works of art have been lost forever due to various wars and peacetime marginalizations.[135]

In modern times (since the 19th century) Serbs also have a noteworthy classical music and works of philosophy.[136] Notable philosophers include Svetozar Marković, Branislav Petronijević, Ksenija Atanasijević, Radomir Konstantinović, Nikola Milošević, Mihailo Marković, Justin Popović and Mihailo Đurić.[137]

Art, music, theatre, and cinema

During the 12th and 13th centuries, many icons, wall paintings and manuscript miniatures came into existence, as many Serbian Orthodox monasteries and churches such as Hilandar, Žiča, Studenica, Sopoćani, Mileševa, Gračanica and Visoki Dečani were built.[138] The architecture of some of these monasteries is world-famous.[61] Prominent architectural styles in the Middle Ages were Raška architectural school, Morava architectural school and Serbo-Byzantin architectural style. During the same period UNESCO protected Stećak monumental medieval tombstones were built. The Independence of Serbia in the 19th century was soon followed with Serbo-Byzantine Revival in architecture.

Baroque and rococo trends in Serbian art emerged in the 18th century and are mostly represented in icon painting and portraits.[139] Most of the Baroque authors were from the territory of Austrian Empire, such as Nikola Nešković, Teodor Kračun, Teodor Ilić Češljar, Zaharije Orfelin and Jakov Orfelin.[140][141] Serbian painting showed the influence of Biedermeier and Neoclassicism as seen in works by Konstantin Danil[142] and Pavel Đurković.[143] Many painters followed the artistic trends set in the 19th century Romanticism, notably Đura Jakšić, Stevan Todorović, Katarina Ivanović and Novak Radonić.[144][145] Since the mid-1800s, Serbia has produced a number of famous painters who are representative of general European artistic trends.[138] One of the most prominent of these was Paja Jovanović, who painted massive canvases on historical themes such as the Migration of the Serbs (1896). Painter Uroš Predić was also prominent in the field of Serbian art, painting the Kosovo Maiden and Happy Brothers. While Jovanović and Predić were both realist painters, artist Nadežda Petrović was an impressionist and fauvist and Sava Šumanović was an accomplished Cubist. Painters Petar Lubarda, Vladimir Veličković and Ljubomir Popović were famous for their surrealism.[146] Marina Abramović is a world-renowned performance artist, writer, and art filmmaker.[147]

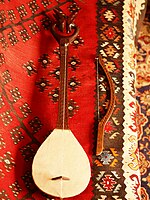

Traditional Serbian music includes various kinds of bagpipes, flutes, horns, trumpets, lutes, psalteries, drums and cymbals.[148] The kolo is the traditional collective folk dance, which has a number of varieties throughout the regions. The first Serbian composers started working in the 14th and 15th century, like Kir Stefan the Serb.[149] Composer and musicologist Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac is considered one of the most important founders of modern Serbian music.[150][151] Other noted classical composers include Kornelije Stanković, Stanislav Binički, Petar Konjović, Miloje Milojević, Stevan Hristić, Josif Marinković, Luigi von Kunits, Ljubica Marić[152] and Vasilije Mokranjac.[153] Well-known musicians include Zdravko Čolić, Arsen Dedić, Predrag Gojković-Cune, Toma Zdravković, Milan Mladenović, Radomir Mihailović Točak, Bora Đorđević, Momčilo Bajagić Bajaga, Đorđe Balašević, Ceca and others.

Serbia has produced many talented filmmakers, the most famous of whom are Slavko Vorkapić, Dušan Makavejev,[154] Živojin Pavlović, Slobodan Šijan, Goran Marković, Goran Paskaljević, Emir Kusturica, Želimir Žilnik, Srđan Dragojević,[155] Srdan Golubović and Mila Turajlić. Žilnik and Stefan Arsenijević won the Golden Bear award at Berlinale, while Mila Turajlić won the main award at IDFA. Kusturica became world-renowned after winning the Palme d'Or twice at the Cannes Film Festival, numerous other prizes, and is a UNICEF National Ambassador for Serbia.[156] Several Americans of Serb origin have been featured prominently in Hollywood. The most notable of these are Academy Award winners Karl Malden,[157][158] Steve Tesich, Peter Bogdanovich, Tony-winning theatre director Darko Tresnjak, Emmy-winning director Marina Zenovich and actors Iván Petrovich, Brad Dexter, Lolita Davidovich, Milla Jovovich and Stana Katic.

Literature

Most literature written by early Serbs was about religious themes. The founders of the Serbian Orthodox Church wrote various gospels, psalters, menologies, hagiographies, along with essays and sermons.[159] At the end of the 12th century, two of the most important pieces of Serbian medieval literature were created– the Miroslav Gospels and the Vukan Gospels, which combined handwritten Biblical texts with painted initials and small pictures.[61] The Crnojević printing house was the first printing house in Southeastern Europe and is considered an important part of Serbian cultural history.[160]

Notable Baroque-influenced authors were Andrija Zmajević, Gavril Stefanović Venclović, Jovan Rajić, Zaharije Orfelin and others. Dositej Obradović was the most prominent figure of the Age of Enlightenment, while the most notable Classicist writer was Jovan Sterija Popović, although his works also contained elements of Romanticism. Modern Serbian literature began with Vuk Karadžić's collections of folk songs in the 19th century, and the writings of Njegoš and Branko Radičević. The first prominent representative of Serbian literature in the 20th century was Jovan Skerlić, who wrote in pre–World War I Belgrade and helped introduce Serbian writers to literary modernism. The most important Serbian writer in the inter-war period was Miloš Crnjanski.[161]

The first Serb authors who appeared after World War II were Mihailo Lalić and Dobrica Ćosić.[162] Other notable post-war Yugoslav authors such as Ivo Andrić and Meša Selimović were assimilated to Serbian culture, and both identified as Serbs.[161] Andrić went on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1961.[162] Danilo Kiš, another popular Serbian writer, was known for writing A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, as well as several acclaimed novels.[163] Amongst contemporary Serbian writers, Milorad Pavić stands out as being the most critically acclaimed, with his novels Dictionary of the Khazars, Landscape Painted with Tea and The Inner Side of the Wind bringing him international recognition. Highly revered in Europe and in South America, Pavić is considered one of the most intriguing writers from the beginning of the 21st century.[164] Charles Simic is a notable contemporary Serbian-American poet, former United States Poet Laureate and a Pulitzer Prize winner.[165] Contemporary writer Zoran Živković authored more than 20 prose books and is best-known for his SF works which have been published in 23 countries.[166][167]

Education and science

Many Serbs have contributed to the field of science and technology. There are more Serbian scientists and scholars working abroad than in the Balkans. At least 7000 Serbs who have a PhD are working abroad.[168]

Serbian American mechanical and electrical engineer Nikola Tesla is regarded as one of the most important inventors in history. He is renowned for his contributions to the discipline of electricity and magnetism in the late 19th and early 20th century. Seven Serbian American engineers and scientists known as Serbo 7[169] took part in construction of the Apollo spaceship.[170] Physicist and physical chemist Mihajlo Pupin is best known for his landmark theory of modern electrical filters as well as for his numerous patents, while Milutin Milanković is best known for his theory of long-term climate change caused by changes in the position of the Earth in comparison to the Sun, now known as Milankovitch cycles.[171] Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic is a Serbian American biomedical engineer focusing on engineering human tissues for regenerative medicine, stem cell research and modeling of disease. She is one of the most highly cited scientists of all times.[172]

Notable Serb mathematicians include Mihailo Petrović, Jovan Karamata and Đuro Kurepa. Mihailo Petrović is known for having contributed significantly to differential equations and phenomenology, as well as inventing one of the first prototypes of an analog computer. Roger Joseph Boscovich was a Ragusan physicist, astronomer, mathematician and polymath of paternal Serbian origin[173][174][175][176] (although there are competing claims for Bošković's nationality) who produced a precursor of atomic theory and made many contributions to astronomy and also discovered the absence of atmosphere on the Moon. Jovan Cvijić founded modern geography in Serbia and made pioneering research on the geography of the Balkan Peninsula, Dinaric race and karst. Josif Pančić made contributions to botany and discovered a number of new floral species including the Serbian spruce.[177] Biologist and physiologist Ivan Đaja performed research in the role of the adrenal glands in thermoregulation, as well as pioneering work in hypothermia.[178][179] Valtazar Bogišić is considered to be a pioneer in the sociology of law and sociological jurisprudence.

Names

There are several different layers of Serbian names. Serbian given names largely originate from Slavic roots: e.g., Vuk, Bojan, Goran, Zoran, Dragan, Milan, Miroslav, Vladimir, Slobodan, Dušan, Milica, Nevena, Vesna, Radmila. Other names are of Christian origin, originating from the Bible (Hebrew, through Greek), such as Lazar, Mihailo, Ivan, Jovan, Ilija, Marija, Ana, Ivana. Along similar lines of non-Slavic Christian names are Greek ones such as: Stefan, Nikola, Aleksandar, Filip, Đorđe, Andrej, Jelena, Katarina, Vasilije, Todor, while those of Latin origin include: Marko, Antonije, Srđan, Marina, Petar, Pavle, Natalija, Igor (through Russian).

Most Serbian surnames are paternal, maternal, occupational or derived from personal traits. It is estimated that over two thirds of all Serbian surnames have the suffix -ić (-ић) ([itɕ]), a Slavic diminutive, originally functioning to create patronymics. Thus the surname Petrović means the "son of Petar" (from a male progenitor, the root is extended with possessive -ov or -ev). Due to limited use of international typewriters and unicode computer encoding, the suffix may be simplified to -ic, historically transcribed with a phonetic ending, -ich or -itch in foreign languages. Other common surname suffixes found among Serbian surnames are -ov, -ev, -in and -ski (without -ić) which is the Slavic possessive case suffix, thus Nikola's son becomes Nikolin, Petar's son Petrov, and Jovan's son Jovanov. Other, less common suffices are -alj/olj/elj, -ija, -ica, -ar/ac/an. The ten most common surnames in Serbia, in order, are Jovanović, Petrović, Nikolić, Marković, Đorđević, Stojanović, Ilić, Stanković, Pavlović and Milošević.[182]

Religion

Right: Church of Saint Sava, one of the largest Orthodox churches in the world, dedicated to the nation's patron saint

Serbs are predominantly Orthodox Christians. The autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church, was established in 1219, as an Archbishopric, and raised to the Patriarchate in 1346.[183] It is led by the Serbian Patriarch, and consists of three archbishoprics, six metropolitanates and thirty-one eparchies, having around 10 million adherents. Followers of the church form the largest religious group in Serbia and Montenegro, and the second-largest in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. The church has an archbishopric in North Macedonia and dioceses in Western Europe, North America, South America[184] and Australia.[185]

The identity of ethnic Serbs was historically largely based on Orthodox Christianity and on the Serbian Church in particular. The conversion of the South Slavs from paganism to Christianity took place before the Great Schism of 1054. During the time of the Great Schism, Serbian rulers including Mihailo Vojislavljević and Stefan Nemanja were Roman Catholics, with the former being a vassal of the Papal States. In 1217, the Serbian ruler Stefan Nemanja II was crowned by Pope Honorius III of the Roman Catholic Church. However in 1219, Nemanja II was crowned once again by the newly independent Serbian Orthodox Church. This shift solidified the Christian Orthodox religion in Serbia.[186]

With the arrival of the Ottoman Empire, some Serbs converted to Islam. This was particularly, but not wholly, the case in Bosnia.[187] Since the second half of the 19th century, a small number of Serbs converted to Protestantism,[188] while historically some Serbs were Roman Catholics (especially in Bay of Kotor[189] and Dalmatia; e.g. Serb-Catholic movement in Dubrovnik).[190] In a personal correspondence with author and critic dr. Milan Šević in 1932, Marko Murat complained that Orthodox Serbs are not acknowledging the Roman Catholic Serb community on the basis of their faith.[191] The remainder of Serbs remain predominantly Serbian Orthodox Christians.

Symbols

Among the most notable national and ethnic symbols are the flag of Serbia and the coat of arms of Serbia. The flag consists of a red-blue-white tricolour, rooted in Pan-Slavism, and has been used since the 19th century. Apart from being the national flag, it is also used officially in Republika Srpska (by Bosnian Serbs) and as the official ethnic Flag of Serbs of Croatia. The coat of arms, which includes both the Serbian eagle and Serbian cross, has also been officially used since the 19th century, its elements dating back to the Middle Ages, showing Byzantine and Christian heritage. These symbols are used by various Serb organisations, political parties and institutions. The Three-finger salute, also called the "Serb salute", is a popular expression for ethnic Serbs and Serbia, originally expressing Serbian Orthodoxy and today simply being a symbol for ethnic Serbs and the Serbian nation, made by extending the thumb, index, and middle fingers of one or both hands.

Traditions and customs

Traditional clothing varies due to diverse geography and climate of the territory inhabited by the Serbs. The traditional footwear, opanci, is worn throughout the Balkans.[192] The most common folk costume of Serbia is that of Šumadija, a region in central Serbia,[193] which includes the national hat, the Šajkača.[194][195] Older villagers still wear their traditional costumes.[193] The traditional dance is the circle dance, called kolo. Zmijanje embroidery is a specific technique of embroidery practised by the women of villages in area Zmijanje on mountain Manjača and as such is a part of the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Pirot carpet is a variety of flat tapestry woven rug traditionally produced in Pirot, a town in southeastern Serbia.

Slava is the family's annual ceremony and veneration of their patron saint, a social event in which the family is together at the house of the patriarch. The tradition is an important ethnic marker of Serb identity.[38] Serbs usually regard the Slava as their most significant and most solemn feast day.[39] Serbs have their own customs regarding Christmas, which includes the sacral tree, the badnjak, a young oak. On Orthodox Easter, Serbs have the tradition of Slavic Egg decorating. Čuvari Hristovog groba is a religious/cultural practice of guarding a representation of Christ's grave on Good Friday in the Church of St. Nicholas by the Serbian Orthodox inhabitants in the town of Vrlika.[196]

Cuisine

Serbian cuisine is largely heterogeneous, with heavy Oriental, Central European and Mediterranean influences.[197] Despite this, it has evolved and achieved its own culinary identity. Food is very important in Serbian social life, particularly during religious holidays such as Christmas, Easter and feast days, i.e., slava.[197] Staples of the Serbian diet include bread, meat, fruits, vegetables, and dairy products. Traditionally, three meals are consumed per day. Breakfast generally consists of eggs, meat and bread. Lunch is considered the main meal, and is normally eaten in the afternoon. Traditionally, Domestic or turkish coffee is prepared after a meal, and is served in small cups.[197] Bread is the basis of all Serbian meals, and it plays an important role in Serbian cuisine and can be found in religious rituals. A traditional Serbian welcome is to offer bread and salt to guests,[198] and also slatko (fruit preserve). Meat is widely consumed, as is fish. Serbian specialties include kajmak (a dairy product similar to clotted cream), proja (cornbread), kačamak (corn-flour porridge), and gibanica (cheese and kajmak pie). Ćevapčići, caseless grilled and seasoned sausages made of minced meat, is the national dish of Serbia.[197]

Šljivovica (Slivovitz) is the national drink of Serbia in domestic production for centuries, and plum is the national fruit. The international name Slivovitz is derived from Serbian.[199] Plum and its products are of great importance to Serbs and part of numerous customs.[200] A Serbian meal usually starts or ends with plum products and Šljivovica is served as an aperitif.[200] A saying goes that the best place to build a house is where a plum tree grows best.[200] Traditionally, Šljivovica (commonly referred to as "rakija") is connected to Serbian culture as a drink used at all important rites of passage (birth, baptism, military service, marriage, death, etc.), and in the Serbian Orthodox patron saint celebration (slava).[200] It is used in numerous folk remedies, and is given certain degree of respect above all other alcoholic drinks. The fertile region of Šumadija in central Serbia is particularly known for its plums and Šljivovica.[201] Serbia is the largest exporter of Slivovitz in the world, and second largest plum producer in the world.[202][203] Winemaking tradition in modern-day Serbia dates back to the Roman times in the 3rd century, while Serbs have been involved in winemaking since the 8th century.[204][205]

Sport

Serbs are known for their sporting achievements, and have produced a number of talented athletes.

The Hungarian citizen Momčilo Tapavica was the first Slav and Serb to win an Olympic medal, in the 1896 Summer Olympics.[206][207]

Over the years Serbia has been home to many internationally successful football players such as Dragan Džajić (officially recognized as "the best Serbian footballer of all times" by Football Association of Serbia; 1968 Ballon d'Or third place), Rajko Mitić, Dragoslav Šekularac and more recent likes of Dragan Stojković, Dejan Stanković, Nemanja Vidić (two-time Premier League Player of the Season and member of FIFPro World XI),[208] Branislav Ivanović (Serbia's most capped player) and Nemanja Matić. Radomir Antić is a notable football coach, best known for his work with the national team, Real Madrid C.F. and FC Barcelona. Serbia has developed a reputation as one of the world's biggest exporters of expat footballers.[209][210]

A total of 22 Serbian players have played in the NBA in the last two decades, including three-time NBA All-Star Predrag "Peja" Stojaković, as well as NBA All-Star and both FIBA and NBA Hall of Fame inductee Vlade Divac.[211] The most notable is Nikola Jokić, the 2020–21–2022 NBA Most Valuable Player Award winner and 2023 NBA finals MVP recipient.[212][213] Serbian players that made a great impact in Europe include four members of the FIBA Hall of Fame from the 1960s and 1970s – Dragan Kićanović, Dražen Dalipagić, Radivoj Korać, and Zoran Slavnić – as well as recent stars such as Dejan Bodiroga (2002 All-Europe Player of the Year), Aleksandar Đorđević (1994 and 1995 Mr. Europa), Miloš Teodosić (2009–10 Euroleague MVP), Nemanja Bjelica (2014–15 Euroleague MVP),[214] and Vasilije Micić (2020–21 Euroleague MVP).[215] The "Serbian coaching school" produced many of the most successful European coaches of all times, such as Željko Obradović (a record nine Euroleague titles), Božidar Maljković (four Euroleague titles), Aleksandar Nikolić (three Euroleague titles), Dušan Ivković (two Euroleague titles), and Svetislav Pešić (one Euroleague title).[216]

One of the most notable Serbian athletes is tennis player Novak Djokovic. He has won an all-time record 24 Grand Slam men's singles titles, and has been year-end World No. 1 on a record eight occasions.[217] Djokovic is regarded by many to be the greatest men's tennis player of all time.[218]

Other notable tennis players include Ana Ivanovic (champion of 2008 French Open) and Jelena Janković, who were both ranked No. 1 in the WTA rankings, while Nenad Zimonjić and Slobodan Živojinović were ranked No. 1 in doubles.[219][220][221]

Notable water polo players are Vladimir Vujasinović, Aleksandar Šapić, Vanja Udovičić, Andrija Prlainović and Filip Filipović.[222]

Other noted Serbian athletes, including Olympic and world champions and medalists, are: swimmer Milorad Čavić, volleyball player Nikola Grbić, handball player Svetlana Kitić,[223] long-jumper Ivana Španović, shooter Jasna Šekarić,[224] sprint canoer Marko Tomićević, judoka Nemanja Majdov[225] and taekwondoist Milica Mandić.[226]

A number of sportspeople of Serb origin represented other nations, such as tennis players Daniel Nestor, Jelena Dokic, Milos Raonic and Kristina Mladenovic, NHL player Milan Lucic, NBA All-star Pete Maravich, wrestler Jim Trifunov, sprint canoer Natasa Dusev-Janics, soccer player Miodrag Belodedici, artistic gymnast Lavinia Miloșovici, racquetball player Rhonda Rajsich and racing driver Bill Vukovich.[227]

Historiography

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Popis 2023 (PDF). Podgorica: Monstat. October 2024.

- ^ Popis 2013 (PDF). Sarajevo: BHAS. June 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "Results" (xlsx). Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in 2021. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ a b Cocozelli, Fred (2016). Ramet, Sabrina (ed.). Ethnic Minorities and Politics in Post-Socialist Southeastern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-1316982778. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Slovenian census". 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2014.

- ^ Државен завод за статистика. "Попис на населението, домаќинствата и становите во Република Македонија, 2002: Дефинитивни податоци" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2010.

- ^ "North Macedonian census" (PDF). 2021.

- ^ "Serbia, Malta interested in strengthening overall relations". srbija.gov.rs. 4 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Innvandring og innvandrere 2006" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Tab11. Populaţia stabilă după etnie şi limba maternă, pe categorii de localităţi". Rezultate Definitive_RPL_2011. Institutul Naţional de Statistică. 2011. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 – 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus – 12. Ethnic data] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Hungarian Central Statistical Office. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "SODB2021 - Obyvatelia - Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "SODB2021 – Obyvatelia – Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Srbi u Nemačkoj – Srbi u Njemačkoj – Zentralrat der Serben in Deutschland". zentralrat-der-serben.de. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Migration und Integration" (in German). Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Srbi u Austriji traže status nacionalne manjine". Blic. 2 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Процењује се да у Француској живи око 200.000 припадника српске дијаспоре, која је настањена у различитим крајевима". 20 May 2022. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2023..

- ^ Mediaspora (2002). "Rezultat istrazivanja o broju Srpskih novinara i medija u svetu". Srpska dijaspora. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016.

- ^ "saez.ch" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bureau, U.S. Census. "American Community Survey 2021". censusreporter.org. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "2016 Census of Population". Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Stefanovic-Banovic, Milesa; Pantovic, Branislav (2013). "'Our' diaspora in Argentina: Historical overview and preliminary research" (PDF). Glasnik Etnografskog Instituta. 61: 119–131. doi:10.2298/GEI1301119S. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

На територији Републике Аргентине данас живи око 30 0002 људи српског и црногорског порекла, већим делом са простора данашње Црне Горе и Хрватске, а мањим делом из Србије и Босне и Херцеговине.

- ^ "Serbs". www.joshuaproject.net. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ The People of Australia – Statistics from the 2011 Census (PDF). Department of Immigration and Border Protection. 2014. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-920996-23-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

Ancestry

- ^ "Srbi u Dubaiju pokrenuli inicijativu za otvaranje konzulata". telegraf.rs. 20 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Afrika i Srbija na vezi". RTS, Radio televizija Srbije, Radio Television of Serbia. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ Marty, Martin E. (1997). Religion, Ethnicity, and Self-Identity: Nations in Turmoil. University Press of New England. ISBN 0-87451-815-6.

[...] the three ethnoreligious groups that have played the roles of the protagonists in the bloody tragedy that has unfolded in the former Yugoslavia: the Christian Orthodox Serbs, the Roman Catholic Croats, and the Muslim Slavs of Bosnia.

- ^ "Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Crnoj Gori 2011. godine" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Cirkovic, Sima M. (15 April 2008). The Serbs. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405142915. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Djilas, Aleksa (1991). The Contested Country: Yugoslav Unity and Communist Revolution, 1919–1953. Harvard University Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780674166981.

- ^ Byford, Jovan (1 January 2008). Denial and Repression of Antisemitism: Post-communist Remembrance of the Serbian Bishop Nikolaj Velimirovi?. Central European University Press. ISBN 9789639776159. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Longinović, Toma (12 August 2011). Vampire Nation: Violence as Cultural Imaginary. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822350392. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Keil, Soeren (December 2017). "The Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Kosovo" (PDF). European Review of International Studies. 4 (2–3). Leiden and Boston: Brill Nijhoff: 39–58. doi:10.3224/eris.v4i2-3.03. ISSN 2196-7415. JSTOR 26593793. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Khakee, Anna; Florquin, Nicolas (1 June 2003). "Kosovo: Difficult Past, Unclear Future" (PDF). Kosovo and the Gun: A Baseline Assessment of Small Arms and Light Weapons in Kosovo. 10. Pristina, United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo and Geneva, Switzerland: Small Arms Survey: 4–6. JSTOR resrep10739.9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

Kosovo—while still formally part of the so-called State Union of Serbia and Montenegro dominated by Serbia—has, since the war, been a United Nations protectorate under the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). [...] However, members of the Kosovo Serb minority of the territory (circa 6–7 per cent in 2000) have, for the most part, not been able to return to their homes. For security reasons, the remaining Kosovo Serb enclaves are, in part, isolated from the rest of Kosovo and protected by the multinational NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR).

- ^ Буквић, Димитрије. "Од златне виљушке до долине јоргована". Politika Online. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ Christopher Catherwood (1 January 2002). Why the Nations Rage: Killing in the Name of God. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0-7425-0090-7.

- ^ a b Ethnologia Balkanica. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 70–. GGKEY:ES2RY3RRUDS. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ a b Celia Jaes Falicov (1991). Family Transitions: Continuity and Change Over the Life Cycle. New York City: Guilford Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-89862-484-7.

- ^ Popowska-Taborska, Hanna (1993). "Ślady etnonimów słowiańskich z elementem obcym w nazewnictwie polskim". Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Linguistica (in Polish). 27: 225–230. doi:10.18778/0208-6077.27.29. hdl:11089/16320. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Popowska-Taborska, Hanna (1999). "Językowe wykładniki opozycji swoi – obcy w procesie tworzenia etnicznej tożsamości". In Jerzy Bartmiński (ed.). Językowy obraz świata (in Polish). Lublin: Wydaw. Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej. pp. 57–63. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Kushniarevich, Alena; et al. (2015). "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0135820. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- ^ Kačar T, Stamenković G, Blagojević J, Krtinić J, Mijović D, Marjanović D (February 2019). "Y chromosome genetic data defined by 23 short tandem repeats in a Serbian population on the Balkan Peninsula". Annals of Human Biology. 46 (1): 77–83. doi:10.1080/03014460.2019.1584242. PMID 30829546. S2CID 73515853.

- ^ Mihajlovic, Milica; Tanasic, Vanja; Markovic, Milica Keckarevic; Kecmanovic, Miljana; Keckarevic, Dusan (1 November 2022). "Distribution of Y-chromosome haplogroups in Serbian population groups originating from historically and geographically significant distinct parts of the Balkan Peninsula". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 61: 102767. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2022.102767. ISSN 1872-4973. PMID 36037736. S2CID 251658864.

- ^ "Average Height by Country 2022". Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ "Body Height and Its Estimation Utilizing Arm Span Measurements in Serbian Adults" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Grasgruber, Pavel; Popović, Stevo; Bokuvka, Dominik; Davidović, Ivan; Hřebíčková, Sylva; Ingrová, Pavlína; Potpara, Predrag; Prce, Stipan; Stračárová, Nikola (2017). "The mountains of giants: An anthropometric survey of male youths in Bosnia and Herzegovina". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (4): 161054. Bibcode:2017RSOS....461054G. doi:10.1098/rsos.161054. PMC 5414258. PMID 28484621.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 26–41.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 29.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 33.

- ^ a b Živković 2002, p. 187.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 38, 41; Ćorović 2001, "Балканска култура у доба сеобе Словена"

- ^ Ćirković, Sima M. (2008). "Srbi među europskim narodima (excerpt)" (PDF). www.mo-vrebac-pavlovac.hr. Golden Marketing-Tehnička Knjiga. pp. 26–27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ Kardaras, Georgios (2018). Byzantium and the Avars, 6th–9th Century AD: Political, Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. BRILL. p. 96. ISBN 978-9-00438-226-8. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Blagojević 1989, p. 19.

- ^ Deliso, Christopher (2008). Culture and Customs of Serbia and Montenegro. ABC-CLIO. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-31334-437-4. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Morozova, Maria (2019). "Language Contact in Social Context: Kinship Terms and Kinship Relations of the Mrkovići in Southern Montenegro". Journal of Language Contact. 12 (2): 307. doi:10.1163/19552629-01202003. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ Komatina 2014, p. 38.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 160,202,225.

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 533.

- ^ a b c Cox 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Vance, Charles; Paik, Yongsun (2006). Managing a Global Workforce: Challenges and Opportunities in International Human Resource Management. M.E. Sharpe. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-76562-016-3. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Cox 2002, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Cox 2002, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c d e Ćirković 2004.

- ^ Rajko L. Veselinović (1966). (1219–1766). Udžbenik za IV razred srpskih pravoslavnih bogoslovija. (Yu 68-1914). Sv. Arh. Sinod Srpske pravoslavne crkve. pp. 70–71.

Устанак Срба у Банату и спалмваъье моштийу св. Саве 1594. — Почетком 1594. године Срби у Банату почели су нападати Турке. Устанак се -нарочито почео ширити после освадаъьа и спашьиваъьа Вршца од стране чете -Петра Маджадца. Устаници осводе неколико утврЬених градова (Охат [...]

- ^ Editions speciales. Naučno delo. 1971. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

Дошло ]е до похреаа Срба у Ба- нату, ко]и су помагали тадаппьи црногоски владика, Херувим и тре- бюьски, Висарион. До покрета и борбе против Ту рака дошло ]е 1596. године и у Цр- иэ] Гори и сус]едним племенима у Харцеговгаш, нарочито под утица- ]ем поменутог владике Висариона. Идупе, 1597. године, [...] Али, а\адика Висарион и во]вода Грдан радили су и дал>е на организован>у борбе, па су придобили и ...

- ^ a b Fotić 2008a, p. 517–519.

- ^ Gavrilović, Slavko (2006), "Isaija Đaković" (PDF), Zbornik Matice Srpske za Istoriju (in Serbian), vol. 74, Novi Sad: Matica Srpska, Department of Social Sciences, Proceedings i History, p. 7, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2011, retrieved 21 December 2011

- ^ Janićijević, Jovan (1996), Kulturna riznica Srbije (in Serbian), IDEA, p. 70, ISBN 9788675470397, archived from the original on 2 January 2016,

Велики или Бечки рат Аустрије против Турске, у којем су Срби, као добровољци, масовно учествовали на аустријској страни

- ^ A ́goston & Masters 2010, p. 383.

- ^ Riley-Smith 2001, p. 251.

- ^ Rodriguez 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Kia 2011, p. 62.

- ^ a b Jelavich 1983, p. 145.

- ^ "Stopama Isakoviča, Karađorđa i komunista – Seobe u Rusiju – Nedeljnik Vreme". www.vreme.com (in Serbian). 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Сеоба Срба у Русију – отишли да их нема". Politika Online. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "[Projekat Rastko] Ljubivoje Cerovic: Srbi u Ukrajini". www.rastko.rs. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Mitev, Plamen (2010). Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe Between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699-1829. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 144. ISBN 978-3643106117. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ MacKenzie, David (1988). "Reviewed work: Knezevina Srbija (1830–1839)., Rados Ljusic". Slavic Review. 47 (2): 362–363. doi:10.2307/2498513. JSTOR 2498513. S2CID 164191946.

- ^ Misha Glenny. "The Balkans Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804–1999". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Royal Family. "200 godina ustanka". Royalfamily.org. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Gordana Stokić (January 2003). "Bibliotekarstvo i menadžment: Moguća paralela" (PDF) (in Serbian). Narodna biblioteka Srbije. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

- ^ Mojović, Dragan (2007). "Velike Srbije nikada nije bilo". NIN: 82, 83.

- ^ Avramović, Sima (2014). "Srpski građanski zakonik (1844) i pravni transplanti – kopija austrijskog uzora ili više od toga?" (PDF). Srpski Građanski Zakonik – 170 Godina. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 542.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, p. 94.

- ^ Miller 2005, pp. 542–543.

- ^ Radivojević, Biljana; Penev, Goran (2014). "Demographic losses of Serbia in the first world war and their long-term consequences". Economic Annals. 59 (203): 29–54. doi:10.2298/EKA1403029R.

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 544.

- ^ a b Miller 2005, p. 545.

- ^ Yeomans 2015, p. 18.

- ^ a b Levy 2009.

- ^ "Ustasa" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Croatia: Serbs". Minority Rights Group International. 19 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Yeomans 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Kallis 2008, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Bartulin 2013, p. 124.

- ^ "SISAK CAMP". Jasenovac Memorial Cite. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Marija Vuselica: Regionen Kroatien in Der Ort des Terrors: Arbeitserziehungslager, Ghettos, Jugendschutzlager, Polizeihaftlager, Sonderlager, Zigeunerlager, Zwangsarbeiterlager, Volume 9 of Der Ort des Terrors, Publisher C.H.Beck, 2009, ISBN 9783406572388 pages 321–323

- ^ Anna Maria Grünfelder: Arbeitseinsatz für die Neuordnung Europas: Zivil- und ZwangsarbeiterInnen aus Jugoslawien in der "Ostmark" 1938/41-1945, Publisher Böhlau Verlag Wien, 2010 ISBN 9783205784531 pages 101–106

- ^ Charny 1999, pp. 18–23.

- ^ Payne 2006, pp. 18–23.

- ^ Dulić 2006.

- ^ Kolanović, Josip, ed. (2003). Dnevnik Diane Budisavljević 1941–1945. Zagreb: Croatian State Archives and Public Institution Jasenovac Memorial Area. pp. 284–85. ISBN 978-9-536-00562-8.

- ^ Lomović, Boško (2014). Die Heldin aus Innsbruck – Diana Obexer Budisavljević. Belgrade: Svet knjige. p. 28. ISBN 978-86-7396-487-4. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Hoare 2011, p. 207.

- ^ Calic 2019, p. 463.

- ^ Marko Attila Hoare. "The Great Serbian threat, ZAVNOBiH and Muslim Bosniak entry into the People's Liberation Movement" (PDF). anubih.ba. Posebna izdanja ANUBiH. p. 123. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Miller 2005, pp. 546–553.

- ^ Miller 2005, pp. 558–562.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (7 May 2000). "New Support to Help Serbs Return to Homes in Kosovo". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, p. 225.

- ^ Djordjević & Zaimi 2019, p. 53-69.

- ^ "Biz – Vesti – Srbi za poslom idu i na kraj sveta". B92. 30 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ ""Европски Љубичевац": Гастарбајтерско село у којем има свега, само нема људи". BBC News на српском (in Serbian (Cyrillic script)). 16 June 2022. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Serbia seeks to fill the '90s brain-drainage gap". EMG.rs. 5 September 2008. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012.

- ^ "Survey S&M 1/2003". Yugoslav Survey. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ Benjamin W. Fortson, IV (7 September 2011). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 431. ISBN 978-1-4443-5968-8. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ Magner, Thomas F. (10 January 2001). "Digraphia in the territories of the Croats and Serbs". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (150). doi:10.1515/ijsl.2001.028. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Dejan Ivković (2013). "Pragmatics meets ideology: Digraphia and non-standard orthographic practices in Serbian online news forums". Journal of Language and Politics. 12 (3). John Benjamins Publishing Company. doi:10.1075/jlp.12.3.02ivk.

- ^ Mojca Ramšak (2008). "Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (1787–1864)". In Donald Haase (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales: G-P. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 531. ISBN 978-0-313-33443-6. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville G. (1 September 2003). The Slavonic Languages. Taylor & Francis. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-203-21320-9. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

... following Vuk's reform of Cyrillic (see above) in the early nineteenth century, Ljudevit Gaj in the 1830s performed the same operation on Latinica,...

- ^ Јасна Влајић-Поповић, „Грецизми у српском језику: осврт на досадашња и поглед на будућа истраживања“ Archived 11 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Јужнословенски филолог, књ. 65 (2009), Београд, стр. 375–403

- ^ a b Лексикон страних речи и израза / Милан Вујаклија, Просвета, Београд (1954) (in Serbian)

- ^ Dejan J. Ivović (2013). "ITALIJANIZMI U GOVORNOM JEZIKU" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d Nomachi 2015, p. 48.

- ^ Nomachi 2015, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Nomachi 2015, p. 49.

- ^ "Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jacob Grimm und Wilhelm Grimm. 16 Bde. (in 32 Teilbänden). Leipzig: S. Hirzel 1854–1960" (in German). Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- ^ "Vampire". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- ^ "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé" (in French). Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- ^ Dauzat, Albert (1938). Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue française (in French). Paris: Librairie Larousse. OCLC 904687.

- ^ Димитрије Оболенски „Византијски комонвелт“, Београд. 1991

- ^ Kadijević, Aleksandar Đ. (2017). "About typology and meaning of the Serbian public architectural monuments (19–20th centuries)". Matica Srpska Journal for Fine Arts. 45.

- ^ Cox 2002, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Žunjić, Slobodan (2010). Istorija srpske filozofije. Belgrade: Plato. ISBN 9788644704829.

- ^ a b Cox 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Milošević, Ana. "OLD ICON PAINTING AND THE RELIGIOUS REVIVAL IN THE 'KINGDOM OF SERBIA' DURING AUSTRIAN RULE 1718–1739". Byzantine Heritage and Serbian Art III Imagining the Past the Reception of the Middle Ages in Serbian Art from the 18 Th to the 21 St Century. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ "Projekat Rastko: Istorija srpske kulture". rastko.rs. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "18. vek". Nedeljnik Vreme. 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Biedermeier Of The 19th Century". galerijamaticesrpske.rs. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "19. vek". Nedeljnik Vreme. 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, Laurence (2010). Serbia. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-84162-326-9. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Romanticism Of The 19th Century". galerijamaticesrpske.rs. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Cox 2002, p. 121.

- ^ "Marina Abramovic in Belgrade: A long-awaited homecoming | DW | 19.09.2019". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Đorđević, Oliver, ed. (2016). Living tradition: guide to roots and folk music in Serbia. Belgrade: World music association of Serbia. pp. 9–15. ISBN 978-86-89607-20-8.

- ^ "[Project Rastko] THE HISTORY OF SERBIAN CULTURE – Roksanda Pejovic: Medieval music". www.rastko.rs. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Projekat Rastko: Istorija srpske kulture". Rastko.rs. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac (1856—1914)". Riznicasrpska.net. 28 September 1914. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Ljubica Marić | Udruženje kompozitora Srbije". composers.rs. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Bills, John William (15 December 2017). "The 10 Best Classical Composers From Serbia". Culture Trip. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Cox 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Richard Taylor, Nancy Wood, Julian Graffy, Dina Iordanova (2019). The BFI Companion to Eastern European and Russian Cinema. Bloomsbury. p. 1936. ISBN 978-1838718497.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Emir Kusturica". UNICEF Serbia. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

- ^ "Карл Малден – дискретни холивудски херој српског порекла". BBC News на српском (in Serbian (Cyrillic script)). 22 March 2022. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Најпоштованији Србин у Холивуду". Politika Online. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Osam vekova srpske književnosti". www2.filg.uj.edu.pl. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Deretić, Jovan (2011). Istorija srpske kulture. Belgrade: Evro-Giunti. pp. 153, 155. ISBN 978-86-505-1849-6.

- ^ a b Miller 2005, pp. 565–567.

- ^ a b Bédé & Edgerton 1980, p. 734.

- ^ Miller 2005, pp. –565–567.

- ^ Sollars & Jennings 2008, p. 604.

- ^ "Serbian roots, American spirit: An interview with Charles Simic". Balkan Insight. 25 May 2011. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Sinhro.rs (11 July 2016). "ZORAN ŽIVKOVIĆ: Zašto da pišem o naučnoj fantastici, kad u njoj živimo » Sinhro.rs". Sinhro.rs. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Preradović, Zoran (14 December 2007). "Srpski pisac sa najviše prevoda". Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Ko su danas najveći srpski naučnici". Nedeljnik. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Serbs of the Apollo Space Program Honored | Serbian Orthodox Church [Official web site]". www.spc.rs. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Vladimir. "The Meaning of Reality". Serbica Americana. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Great Serbian scientists". Consulate General of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008.

- ^ "Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic – Google Scholar Citations". Google Scholar. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "People « National Tourism Organisation of Serbia". serbia.travel. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Jandric, Miroslav (2011). Three Centuries from the Birth of Rudjer Boskovic (1711– 1787) (PDF). pp. 449 (footnote). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "Boris Tadić: Ruđer Bošković je bio Srbin katolik. Nadam se da me Hrvati neće krivo shvatiti – Jutarnji List". jutarnji.hr. 13 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ Georgevich, Dragoslav (1977). Serbian Americans and their communities in Cleveland. p. 73. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Lubarda, Biljana. "Plant species and subspecies discovered by Dr. Josif Pančić 1 – distribution and floristic importance". Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ General Encyclopedia of the Yugoslav Lexicographical Institute, III edition, Vol 2 C-Fob. Jugoslavenski leksikografski zavod "Miroslav Krleža". 1977.

- ^ "Short biography". Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "O poreklu obožavanja i straha od VUKA: Prema predanju on je mitološki predstavnik srpskog naroda". National Geographic (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Loma, Aleksandar (2021). "Srbi i vuci u istraživanjima Veselina Čajkanovića". Književna istorija. 174: 13–44.

- ^ Tanjug. "Srbija, zemlja Milice i Dragana : Društvo : POLITIKA". Politika. Archived from the original on 16 June 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Fotić 2008b, p. 519–520.

- ^ "О НАМА | Православна Црква у Чилеу". www.pravoslavie.cl. 7 September 2016. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ Cvetković 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Grumeza, Ion (2010). The Roots of Balkanization Eastern Europe C.E. 500-1500. United States of America: University Press of America. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-7618-5135-6.

- ^ World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. 2010. ISBN 9780761479031. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Bjelajac, Branko (2002). "Protestantism in Serbia". Religion, State and Society. 30 (3): 169–218. doi:10.1080/0963749022000009225. ISSN 0963-7494. S2CID 144017406. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ "Nisu svi Srbi pravoslavne vere". Politika. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ Christian Promitzer; Klaus-Jürgen Hermanik & Eduard Staudinger (2009). (Hidden) Minorities: Language and Ethnic Identity Between Central Europe and the Balkans. The Lit Verlag in 2009. ISBN 9783643500960. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Bozic, Sofija (1 January 2014). "Umetnost, politika, svakodnevica – tematski okviri prijateljstva Marka Murata i Milana Sevica". Prilozi za književnost, jezik, istoriju i folklor (80): 203–217. doi:10.2298/PKJIF1480203B.

...Ove tvoje poslednje reklo bi se da nisi primio moju gde sam Ti doneo jednu istinitu priču o Zmaju kad ono bijaše u Dubr. o otkrivanju spomenika Dživu Gunduliću. Pitao Zmaj jednog mladog dubrovačkog majstora da mu pokaže gde je srpska crkva. Mladić odgovori: "Koja?" Zmaj: "Srpska". Mladić: "Koja? Ovdi su u nas sve srpske. Koju mislite?" Zmaj: "Pravoslavnu". Mladić: "E! tako recite. Pravoslavna vam je она онамо". I Zmaj je pohvalio našega meštra koji mu je dao dobru lekciju. — Ali sve zaludu, Milane moj! Ovi naši pravoslavci (koji ne vjeruju ništa, ateiste) zbog vere ne priznaju nas. Nismo im pravi. Ne veruju nikome. Ni vama šojkama. Valjda im niste dovoljno pravoslavni!! Jer su oni jako skrupolozni in re fidei et morum. Et morum, Milane moj! E se non ridi — piange piuttosto. Zato nam ide sve ovako manjifiko. Hoćemo mi našu specijalnu kulturu! Sve su drugo švabe kelerabe etcetc!

- ^ Mirjana Prošić-Dvornić (1989). Narodna nošnja Šumadije. Kulturno-Prosvjetni Sabor Hrvatske. p. 62. ISBN 9788680825526. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ a b Dragoljub Zamurović; Ilja Slani; Madge Phillips-Tomašević (2002). Serbia: life and customs. ULUPUDS. p. 194. ISBN 9788682893059. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ Deliso, Christopher (2009). Culture and Customs of Serbia and Montenegro. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-313-34436-7.

- ^ Resić, Sanimir; Plewa, Barbara Törnquist (2002). The Balkans in Focus: Cultural Boundaries in Europe. Lund, Sweden: Nordic Academic Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-91-89116-38-2. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ "Riznica – Čuvari Hristovog groba". www.rts.rs. RTS, Radio televizija Srbije, Radio Television of Serbia. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d Albala 2011, pp. 328–330.

- ^ "Живот између повојнице и поскурица: "Прича о хлебу је прича о нама самима"". BBC News на српском (in Serbian (Cyrillic script)). 9 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Haraksimová, Erna; Rita Mokrá; Dagmar Smrčinová (2006). "slivovica". Anglicko-slovenský a slovensko-anglický slovník. Praha: Ottovo nakladatelství. p. 775. ISBN 80-7360-457-4.

- ^ a b c d Stephen Mennell (2005). Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity, Diversity and Dialogue. Council of Europe. p. 383. ISBN 978-92-871-5744-7. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.

- ^ Grolier Incorporated (2000). The encyclopedia Americana. Grolier. p. 715. ISBN 978-0-7172-0133-4.

- ^ "Preliminary 2011 Data". FAOSTAT. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ "Fruit Industry in Serbia" (PDF). SIEPA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2011.

- ^ Štetić, Marina N. (2020). Vinogradarstvo u srednjovekovnoj Srbiji. Belgrade: University of Belgrade, Faculty of philosophy. p. 25.

- ^ "Od cara Marka Aurelija Proba do kneza Mihaila Obrenovića: Istorija vinogradarstva i vinskog turizma u Srbiji". National Geographic (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Momčilo Tapavica je bio arhitekta i PRVI SLOVEN koji je osvojio olimpijsku medalje, NjEGOVIM ZGRADAMA divio se i kralj Nikola". Večernje novosti (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "10 naših olimpijskih heroja". Nedeljnik. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Hall of Fame nominee: Nemanja Vidic". www.premierleague.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Shivam Kumar (27 January 2010). "Serbia's Endless List of Wonderkids". Sportslens. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ "Srbija šesta na listi najvećih izvoznika fudbalera na svetu – Sport – Dnevni list Danas" (in Serbian). 16 May 2020. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Kings General Manager Vlade Divac Elected Into Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame". Sacramento Kings. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Nikola Jokic wins 2020–21 Kia NBA Most Valuable Player Award". www.nba.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ "Nikola Jokic Named 2023 NBA Finals MVP After Record-Shattering Postseason Leads Nuggets to First Title". 13 June 2023.

- ^ "2014–15 bwin MVP: Nemanja Bjelica, Fenerbahce Ulker Istanbul". Welcome to EUROLEAGUE BASKETBALL. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Efes's Vasilije Micic is voted the EuroLeague's 2020–21 season MVP!". Welcome to EUROLEAGUE BASKETBALL. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Secrets of the Serbian coaching school". Welcome to EUROLEAGUE BASKETBALL. 26 May 2023. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "DJOKOVIC CLINCHES RECORD-EXTENDING EIGHTH YEAR-END NO. 1".

- ^ "Novak Djokovic Put the Men's Tennis GOAT Debate to Rest in 2023". 26 December 2023.

- ^ "Nenad Zimonjic". ATP World Tour. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Jankovic to take number one spot". BBC Sport. 2 August 2008. Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Ana Ivanovic". WTA. 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Vaterpolo Srbija – Serbia Water Polo: Velika imena". www.waterpoloserbia.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Војводине, Јавна медијска установа ЈМУ Радио-телевизија. "Svetlana Kitić najbolja rukometašica sveta svih vremena". ЈМУ Радио-телевизија Војводине. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Neprevaziđena Jasna Šekarić i pet olimpijskih medalja!". Sportklub (in Serbian). 6 August 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Srpski džudista Nemanja Majdov prvak sveta". NOVOSTI. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2020.