Hijab: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Who?}} |

|||

| Line 241: | Line 241: | ||

*{{commons category-inline|hijabs}} |

*{{commons category-inline|hijabs}} |

||

*[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/pop_ups/05/europe_muslim_veils/html/1.stm BBC drawings of different types of Islamic women's clothing] |

*[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/pop_ups/05/europe_muslim_veils/html/1.stm BBC drawings of different types of Islamic women's clothing] |

||

===Orthodox Islam=== |

|||

*[http://al-taqwa.tk/Quran-and-Hadith-on-Hijab.php Qur'an and Hadith on Hijab] |

|||

===Contemporary Muslim opinion=== |

===Contemporary Muslim opinion=== |

||

* [http://islamicweb.com/beliefs/women/albani_niqab.htm Niqab is not required] |

* [http://islamicweb.com/beliefs/women/albani_niqab.htm Niqab is not required] |

||

Revision as of 09:18, 6 March 2014

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Clothing |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

"Hijab" or "ḥijāb" (/hɪˈdʒɑːb/, /hɪˈdʒæb/, /ˈhɪ.dʒæb/ or /hɛˈdʒɑːb/;[1][2][3][4] Arabic: حجاب, pronounced [ħiˈdʒæːb] ~ [ħiˈɡæːb]) is a veil that covers the head and chest, which is particularly worn by a Muslim female beyond the age of puberty in the presence of adult males outside of their immediate family. It can further refer to any head, face, or body covering worn by Muslim women that conforms to a certain standard of modesty. It not only refers to the physical body covering, but also embodies a metaphysical dimension, where al-hijab refers to "the veil which separates man or the world from God.”[5] Hijab can also be used to refer to the seclusion of women from men in the public sphere. Most often, it is worn by Muslim women as a symbol of modesty, privacy and morality. According to the Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World, modesty in the Qur'an concerns both men's and women's gaze, gait, garments, and genitalia."[6] The Quran admonishes Muslim women to dress modestly and cover their breasts and genitals.[7] The Quran has no requirement that women cover their faces with a veil, or cover their bodies with the full-body burqua or chador.[8] The Qur'an does not mandate or mention Hijab.[9][10]

Summary

The term hijab in Arabic literally means “a screen or curtain” and is used in the Qur'an to refer to a partition. The Qur'an tells the male believers (Muslims) to talk to the wives of the Prophet Muhammad behind a curtain. This curtain was the responsibility of the men and not the wives of Prophet Muhammad. Most Islamic legal systems define this type of modest dressing as covering everything except the face and hands in public.[5][11] Guidelines for covering of the entire body except for the hands, the feet and the face, are found in texts of fiqh and hadith that are developed after the Qur'an.[6] Some interpretations, however, say that a veil is not compulsory in front of blind, asexual or gay men.[12][13][14] Αlthough hijab is often seen by westerners as a tool utilized by men to control and silence women, the practice is understood differently in different contexts.[15] Μen have also partaken in the practice of veiling. Fadwa El Guindi, a prominent Islamic scholar, writes, “Confining the study of the veil, just like the study of women, to the domain of gender in lieu of society and culture narrows the scope in a way that limits cultural understanding and theoretical conceptualization” (10). Post September 11, 2001, the hijab has generated much controversy and stereotyping. Many countries have attempted to restrict the wearing of the hijab in public spaces, causing outcry both within and outside of the Muslim community and compelling women to veil as a statement against repression.[16]

In Islamic texts

Qur'an

The Qur'an instructs both Muslim men and women to dress in a modest way:

"Tell the believing men to lower their gaze and be modest" (surah 24:30)

The clearest verse on the requirement of the hijab is surah 24:30–31, asking women to draw their khimār over their bosoms.[17][18]

And say to the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty; that they should not display their beauty and ornaments except what (must ordinarily) appear thereof; that they should draw their khimār over their breasts and not display their beauty except to their husband, their fathers, their husband's fathers, their sons, their husbands' sons, their brothers or their brothers' sons, or their sisters' sons, or their women, or the slaves whom their right hands possess, or male servants free of physical needs, or small children who have no sense of the shame of sex; and that they should not strike their feet in order to draw attention to their hidden ornaments. (Quran 24:31)

In the following verse, the wives of the Prophet women are asked to draw their jilbab over them (when they go out), as a measure to distinguish themselves from others, so that they are not harassed. Surah 33:59 reads:[18]

Those who harass believing men and believing women undeservedly, bear (on themselves) a calumny and a grievous sin. O Prophet! Enjoin your wives, your daughters, and the wives of true believers that they should cast their outer garments over their persons (when abroad): That is most convenient, that they may be distinguished and not be harassed. [...] (Quran 33:58–59)

Alternative views

Some Muslims take a relativist approach to hijab. They believe that the commandment to maintain modesty must be interpreted with regard to the surrounding society. What is considered modest or daring in one society might not be considered so in another. It is important, they say, for believers to wear clothing that communicates modesty and reserve.[19]

Other verses do mention separation of men and women.

Abide still in your homes and make not a dazzling display like that of the former times of ignorance[Quran 33:32–33]

And when ye ask of them [the wives of the Prophet] anything, ask it of them from behind a curtain.[Quran 33:53]

According to at least three authors (Karen Armstrong, Reza Aslan and Leila Ahmed), the stipulations of the hijab were originally meant only for Muhammad's wives, and were intended to maintain their inviolability. This was because Muhammad conducted all religious and civic affairs in the mosque adjacent to his home:

People were constantly coming in and out of this compound at all hours of the day. When delegations from other tribes came to speak with Prophet Muhammad, they would set up their tents for days at a time inside the open courtyard, just a few feet away from the apartments in which Prophet Muhammad's wives slept. And new emigrants who arrived in Yatrib would often stay within the mosque's walls until they could find suitable homes.[20]

According to Ahmed:

By instituting seclusion Prophet Muhammad was creating a distance between his wives and this thronging community on their doorstep.[21]

They argue that the term darabat al-hijab ("taking the veil"), was used synonymously and interchangeably with "becoming Prophet Muhammad's wife", and that during Muhammad's life, no other Muslim woman wore the hijab. Aslan suggests that Muslim women started to wear the hijab to emulate Prophet Muhammad's wives, who are revered as "Mothers of the Believers" in Islam,[20] and states "there was no tradition of veiling until around 627 C.E." in the Muslim community.[20][21]

Hadith

The Arabic word jilbab is translated as "cloak" in the following passage. Contemporary Salafis insist that the jilbab (which is worn over the Kimaar and covers from the head to the toe) worn today is the same garment mentioned in the Qur'an and the hadith; other translators have chosen to use less specific terms:

- Narrated Anas ibn Malik: "I know (about) the Hijab (the order of veiling of women) more than anybody else. Ubay ibn Ka'b used to ask me about it. Allah's Apostle became the bridegroom of Zaynab bint Jahsh whom he married at Medina. After the sun had risen high in the sky, the Prophet invited the people to a meal. Allah's Apostle remained sitting and some people remained sitting with him after the other guests had left. Then Allah's Apostle got up and went away, and I too, followed him till he reached the door of 'Aisha's room. Then he thought that the people must have left the place by then, so he returned and I also returned with him. Behold, the people were still sitting at their places. So he went back again for the second time, and I went along with him too. When we reached the door of 'Aisha's room, he returned and I also returned with him to see that the people had left. Thereupon the Prophet hung a curtain between me and him and the Verse regarding the order for (veiling of women) Hijab was revealed." Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:65:375, Sahih Muslim, 8:3334

- Narrated Umm Salama Hind bint Abi Umayya, Ummul Mu'minin: "When the verse 'That they should cast their outer garments over their persons' was revealed, the women of Ansar came out as if they had crows hanging down over their heads by wearing outer garments." 32:4090. Abū Dawud classed this hadith as authentic.

- Narrated Safiya bint Shaiba: "Aisha used to say: 'When (the Verse): "They should draw their veils (Khumur) over their necks and bosoms (juyyub)," was revealed, (the ladies) cut their waist sheets at the edges and covered their faces with the cut pieces.'" Sahih al-Bukhari, 6:60:282, 32:4091.

Dress code required by hijab

Traditionally, Muslims have recognized many different forms of clothing as satisfying the demands of hijab.[22] Debate focused on how much of the male or female body should be covered. Different scholars adopted different interpretations of the original texts.

Women

The four major Sunni schools of thought (Hanafi, Shafi'i, Maliki and Hanbali) hold that the entire body of the woman, except her face and hands – though a few clerics[who?] say face, hands – must be covered during prayer and in public settings (see Awrah). There are those who allow the feet to be uncovered as well as the hands and face.[23][24]

It is recommended that women wear clothing that is not form fitting to the body: either modest forms of western clothing (long shirts and skirts), or the more traditional jilbāb, a high-necked, loose robe that covers the arms and legs. A khimār or shaylah, a scarf or cowl that covers all but the face, is also worn in many different styles. Some scholars encourage covering the face, while some follow the opinion that it is only not obligatory to cover the face and the hands but mustahab (Highly recommended). Other scholars oppose face covering, particularly in the West, where the woman may draw more attention as a result. These garments are very different in cut from most of the traditional forms of ħijāb, and they are worn worldwide by Muslims.

Detailed scholarly attention has focused on prescribing female dress. Many Muslims believe that basic requirements mean that, in the presence of someone of the opposite sex other than a close family member (those within the prohibited degrees of marriage—see mahram), a woman should cover her body, and walk and dress in a way that does not draw sexual attention to her. Some believers go so far as to specify exactly which areas of the body must be covered. In some cases, this is everything but the eyes, but most require that women cover everything but the face and hands. In nearly all Muslim cultures, young girls are not required to wear a ħijāb. There is not a single agreed age when a woman should begin wearing a ħijāb—but in many Muslim cultures, puberty is the dividing line.

In private, and in the presence of mahrams, rules on dress relax. However, in the presence of the husband, most scholars stress the importance of mutual freedom and pleasure of the husband and wife.[25]

Garments

The burqa (also spelled burka) is the garment that covers women most completely: either only the eyes are visible, or nothing at all. Originating in what is now Pakistan, it is more commonly associated with the Afghan chadri. Typically, a burqa is composed of many yards of light material pleated around a cap that fits over the top of the head, or a scarf over the face (save the eyes). This type of veil is cultural as limited to the people of that part of the world.

It has become tradition that Muslims in general, and Salafis in particular, believe the Qur'an demands women wear the garments known today as jilbāb and khumūr (the khumūr must be worn underneath the jilbāb). However, Qur'an translators and commentators translate the Arabic into English words with a general meaning, such as veils, head-coverings and shawls.[26] Ghamidi argues that verses [Quran 24:30] teach etiquette for male and female interactions, where khumūr is mentioned in reference to the clothing of Arab women in the 7th century, but there is no command to actually wear them in any specific way. Hence he considers head-covering a preferable practice but not a directive of the sharia (law).[27]

Men

Although certain general standards are widely accepted, there has been little interest in narrowly prescribing what constitutes modest dress for Muslim men. Many scholars recommend that men should cover themselves from the navel to the knees.[28] It is also widely accepted that male clothes should not be tight-fitting or "glamorous".[28]

According to some sources, Muslim men should not wear gold jewellery, silk clothing, or adornments that are considered feminine.[29][30]

Sartorial hijab as practiced

In Iran, where wearing the hijab is legally required, women, especially younger ones, have taken to wearing transparent and very loosely worn hijabs.

In Turkey, where the hijab is banned in private and state universities and schools, 11% of women wear it, though 60% wear traditional non-Islamic headscarves, figures of which are often confused with hijab.[31][32][33]

Historical and cultural explanations of the hijab

History

The term hijab is never used in the Qur'an to describe an article of clothing.[34] The only verses in the Qur'an that specifically reference women’s clothing, are those promoting modesty, instructing women to guard their private parts and throw a scarf over their bosoms in the presence of men.[34] The contemporary understanding of the hijab dates back to Hadith when the “verse of the hijab” descended upon the community in 627 CE.[35] Now documented in Sura 33: 53 the verse states, “And when you ask [his wives] for something, ask them from behind a partition. That is purer for your hearts and their hearts”.[36] This verse, however, was not addressed to women in general, but exclusively to Muhammad’s wives. As Muhammad’s influence increased, he entertained more and more visitors in the mosque, which was then his home. Often, these visitors stayed the night only feet away from his wives’ apartments. It is commonly understood that this verse was intentioned to protect his wives from these strangers.[37] During Muhammad’s lifetime no other women in the Ummah (Muslim community) observed the hijab. Instead, the term for donning the veil, darabat al-hijab, was used interchangeably with “becoming Muhammad’s wife”.[38] As stated by Muslim Scholar Reza Aslan, “The veil was neither compulsory nor widely adopted until generations after Muhammad’s death, when a large body of male scriptural and legal scholars began using their religious and political authority to regain the dominance they had lost in society as a result of the Prophet’s egalitarian reforms”.[37] Other scholars point out that the Qur'an does not require women to wear veils; rather, it was a social habit picked up with the expansion of Islam. In fact, since it was impractical for working women to wear veils, "A veiled woman silently announced that her husband was rich enough to keep her idle."[39]

Veiling, however, did not originate with the advent of Islam. Statuettes depicting veiled priestesses precede all three Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, and Islam), dating back as far as 2500 BCE.[40] Some scholars postulate that the customs of veiling and seclusion of women in early Islam were assimilated from the conquered Persian and Byzantine societies and then later on they were viewed as appropriate expressions of Quranic norms and values. Elite women in ancient Mesopotamia and in the Byzantine, Greek, and Persian empires wore the veil as sign of respectability and high status.[41] In ancient Mesopotamia, Assyrian law had explicit laws enforcing which women must veil and which women could not, depending upon a woman’s class, rank, and occupation in society. Veiling was meant to “differentiate between ‘respectable’ women and those who were publicly available”.[41] Women slaves and unchaste women were distinctly forbidden to veil and suffered harsh penalties if they did so. Veiling was, thus, a marker of rank and exclusive lifestyle, subtley illustrating upper-class women’s privilege over women in lower class ranks in the Assyrian community. During the period directly preceding the Muslim conquest in 640 CE, the Sassanians ruled in Mesopotamia. Customs of Persian royalty at the time of the first Persian conquest of Mesopotamia continued to be practiced and became even more elaborate under the Sassanians. In addition to acknowledging the monotheistic religion of Zoroastrianism among the upper classes, such customs included large harems of women and, of most note for this article, veiling.

Strict seclusion and the veiling of matrons were in place in Roman and Byzantine society as well. Between 550-323 B.C.E, prior to Christianity, respectable women in classical Greek society were expected to seclude themselves and wore clothing that concealed them from the eyes of strange men.[42] These customs influenced the later Byzantine empire where proper conduct for girls entailed that they neither be seen nor heard outside their home. Like in Assyrian law, respectable women were expected to veil and low class women were forbidden from partaking in the practice. By the 5th and 6th centuries, societies of the Mediterranean Middle East were dominated by Christian and some Jewish populations. At the inception of Christianity, Jewish women were veiling the head and face. Biblical evidence of veiling can be found in Genesis 24:65, “And Rebekah lifted up her eyes and when she saw Isaac ... she took her veil and covered herself’; in Isaiah 3:23, “In that day the Lord will take away the finery of the anklets ... the headdresses ... and the veils”; and in 1 Corinthians 11:3–7, "Any woman who prays with her head unveiled dishonors her head—it is the same as if her head were shaven. For if a woman will not veil herself, then she should cut off her hair, but if it is disgraceful for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her wear a veil. For a man ought not to cover his head, since he is the image and glory of God; but woman is the glory of man".[43] Others think that the word habarah the word ḥabarah [, which consists of a long skirt, a head cover, and a burqa, a long rectangular cloth of white transparent muslin placed below the eyes, covering the lower nose and the mouth and falling to the chest] itself derives from early Christian and Judaic religious vocabulary.” [43] The Christian church’s attitude towards sex as shameful was focused most intensely on the shamefulness of the female body, which had to be totally concealed. As the prominent scholar, Leila Ahmed states, “Whatever the cultural source or sources, a fierce misogyny was a distinct ingredient of Mediterranean and eventually Christian thought in the centuries immediately preceding the rise of Islam.”[16]

Thus, successive invasions during the Muslim conquest led to some synthesis in the cultural practices of Greek, Persian, and Mesopotamian empires and the Semitic peoples of the regions.[43] Because Islam identified with the monotheistic religions of the conquered empires, the practice was adopted as an appropriate expression of Qur'anic ideals regarding modesty and piety.[44] Veiling gradually spread to upper-class Arab women, and eventually it became widespread among Muslim women in cities throughout the Middle East. It gradually spread among urban populations, becoming more pervasive under Ottoman rule as a mark of rank and exclusive lifestyle.[43] Women in rural areas were much slower to adopt veiling because the garments interfered with their work in the fields.[45]

The mid-twentieth century saw a resurgence of the hijab in Egypt after a long period of decline as a result of the westernization of Egypt under the rule of Gamal Abdel Nasser. The hijab, Veil, often taken to mean suppression of the Islamic woman, began to symbolize a commitment to "the service of the Islamic call [to help] devastated families."[46] The veil became a liberating symbol of being an Islamic woman with a cause for social justice.

Overall, the hijab is meant to highlight the individual’s relationship with Allah. Many scholars [who?] believe that the hijab was a source of separation, in which to allow Muhammad’s wives to find oneness with Allah.

Contemporary context

The mid-1970s marked a period in which college aged Muslim men and women began a movement meant to reunite and rededicate themselves to the Islamic faith.[47][48] This movement was named the Sahwah,[49] or awakening, and was and sparked a period of heightened religiosity that spread across the east that was evident in every aspect of the believers life through the ways in which they chose to dress themselves.[47] The uniform adopted by the young female pioneers of this movement was named al-Islāmī (Islamic dress) and was made up of an “al-jilbāb—an unfitted, long-sleeved, ankle-length gown in austere solid colors and thick opaque fabric—and al-khimār, a head cover resembling a nun's wimple that covers the hair low to the forehead, comes under the chin to conceal the neck, and falls down over the chest and back”.[47] In addition to the basic garments that were mostly universal within the movement, additional measures of modesty could be taken depending on how conservative the followers wished to be. Some women choose to also utilize a face covering (al-niqāb) that leaves only eye slits for sight, as well as both gloves and socks in order to reveal no visible skin.

Soon this movement expanded outside of the youth realm and became a more widespread Muslim practice. Women viewed this way of dress as a way to both publicly announce their religious beliefs as well as a way to simultaneously reject western influences of dress and culture that were prevalent at the time. Despite many criticisms of the practice of hijab being oppressive and detrimental to women’s equality,[48] many Muslim women view the way of dress to be a positive thing. It is seen as a way to avoid harassment and unwanted sexual advances in public and works to desexualize women in the public sphere in order to instead allow them to enjoy equal rights of complete legal, economic, and political status. This modesty was not only demonstrated by their chosen way of dress but also by their serious demeanor which worked to show their dedication to modesty and Islamic beliefs.[47] Despite the pure intentions of the Muslim practice of wearing the hijab, controversy erupted over the practice. Many people, both men and women from backgrounds of both Islamic and non-Islamic faith questioned the hijab and what it stood for in terms of women and their rights. There was questioning of whether in practice the hijab was truly a female choice or if women were being coerced or pressured into wearing it.[47] Many instances, such as a period of forced veiling for women in Iran, brought these issues to the forefront and generated great debate from both scholars and everyday people.

As the awakening movement gained momentum, its goals matured and shifted from promoting modesty and Islamic identity towards more of a political stance in terms of retaining support for Islamic nationalism and to resist western influences. Today the hijab means many different things for different people. For Islamic women who choose to wear the hijab it allows them to retain their modesty, morals and freedom of choice.[48] They choose to cover because they believe it is liberating and allows them to avoid harassment. Many people (both Muslim and non-Muslim) are against the wearing of the hijab and argue that the hijab causes issues with gender relations, works to silence and repress women both physically and metaphorically, and have many other problems with the practice. This difference in opinions has generated a plethora of discussion on the subject, both emotional and academic, which continues today.

Ever since September 11, 2001, the discussion and discourse on the hijab has intensified. Many nations have attempted to put restrictions on the hijab, which has led to a new wave of rebellion by women who instead turn to covering and wearing the hijab in even greater numbers.[48][50] Some of the more notable events that have occurred in the recent past can be read about in the further reading section.

Modern practice

Wearing the hijab in Kazakhstan is not prohibited, but is widely criticized as a foreign custom (the traditional scarf worn by Central Asian married women resemble the bandana, not the hijab), because it was not practiced until the fall of the USSR and the arrival of foreign Islamic missionaries.

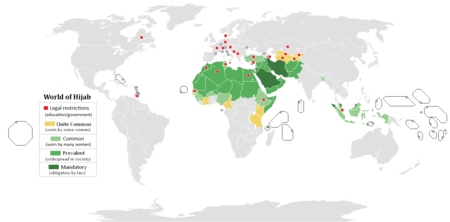

Governmental enforcement and bans

Some governments encourage and even oblige women to wear the hijab, while others have banned it in at least some public settings.

Some Muslims believe hijab covering for women should be compulsory as part of sharia, i.e. Muslim law. Wearing of the hijab was enforced by the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. The Taliban's Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan required women to cover not only their head but their face as well, because "the face of a woman is a source of corruption" for men not related to them.[51] Today, covering face by niqab is compulsory in many sacred places in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Turkey, Tunisia, and Tajikistan are Muslim-majority countries where the law prohibits the wearing of hijab in government buildings, schools, and universities. In Tunisia, women were banned from wearing hijab in state offices in 1981 and in the 1980s and 1990s more restrictions were put in place.[52] In 2008 the Turkish government attempted to lift a ban on Muslim headscarves at universities, but were overturned by the country's Constitutional Court.[53] Though in December 2010, the Turkish government ended the headscarf ban in universities.[54]

Iran is another specific case. Tradition of veiling hair in Iranian culture has ancient pre-Islamic origins,[55] but such widespread custom had been ended forcibly by Reza Shah's regime in 1936, as incompatible with his modernizing ambitions. The police were arresting women who wore the veil and forcibly removing it, and such policy outraged the Shi'a clerics, and ordinary men and women, to whom appearing in public without their cover was tantamount to nakedness. Many women refused to leave the house in fear of being assaulted by Reza Shah's police.[56] Eventually rules of dress code were relaxed, and after Reza Shah's abdication in 1941 the compulsory element in the policy of unveiling was abandoned, though the policy remained intact throughout the Pahlavi era. According to Mir-Hosseini, 'between 1941 and 1979 wearing hejab [hijab] was no longer an offence, but it was a real hindrance to climbing the social ladder, a badge of backwardness and a marker of class. A headscarf, let alone the chador, prejudiced the chances of advancement in work and society not only of working women but also of men, who were increasingly expected to appear with their wives at social functions. After fall of dictatorship shortly after Iranian Revolution of 1979, veiling hair in public become standard again. With the cooling of revolutionary enthusiasm and increasing popular disenchantment with the new government, the rules of hijab have been largely eroded, in many ways only being a technicality among many urban women, who wear headscarves so far back on their heads it barely covers it. More conservative type like kimars and chadors are still widespread in government institutions, mosques, sacred places and conservative areas.

On March 15, 2004, France passed a law banning "symbols or clothes through which students conspicuously display their religious affiliation" in public primary schools, middle schools, and secondary schools. In the Belgian city of Maaseik, Niqāb has been banned since 2006.[57] On July 13, 2010, France's lower house of parliament overwhelmingly approved a bill that would ban wearing the Islamic full veil in public. There were 335 votes for the bill and one against in the 557-seat National Assembly.

Non-governmental enforcement

Non-governmental enforcement of hijab is found in many parts of the Muslim world.

Successful informal coercion of women by sectors of society to wear hijab has been reported in Gaza where Mujama' al-Islami, the predecessor of Hamas, reportedly used "a mixture of consent and coercion" to "'restore' hijab" on urban educated women in Gaza in the late 1970s and 1980s.[58]

Similar behaviour was displayed by Hamas itself during the First Intifada in Palestine. Though a relatively small movement at this time, Hamas exploited the political vacuum left by perceived failures in strategy by the Palestinian factions to call for a 'return' to Islam as a path to success, a campaign that focused on the role of women.[59] Hamas campaigned for the wearing of the hijab alongside other measures, including insisting women stay at home, segregation from men and the promotion of polygamy. In the course of this campaign women who chose not to wear the hijab were verbally and physically harassed, with the result that the hijab was being worn 'just to avoid problems on the streets'.[60]

In Srinagar, India in 2001 an "acid attack on four young Muslim women ... by an unknown militant outfit [was followed by] swift compliance by women of all ages on the issue of wearing the chadar (head-dress) in public."[61][62][63]

Islamists in other countries have been accused of attacking or threatening to attack the faces of women in an effort to intimidate them from wearing makeup or from wearing allegedly immodest dress.[64][65][66]

Hijab by country

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ "Definition of hijab in Oxford Dictionaries (British & World English)". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ "Hijab - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ "hijab noun - definition in British English Dictionary & Thesaurus - Cambridge Dictionary Online". Dictionary.cambridge.org. 2013-04-16. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ "Definition of hijab". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ a b Glasse, Cyril, The New Encyclopedia of Islam, Altamira Press, 2001, p.179-180

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World (2003), p.721, New York: Macmillan Reference USA

- ^ Martin et al. (2003), Encyclopedia of Islam & the Muslim World, Macmillan Reference, ISBN 978-0028656038

- ^ http://middleeast.about.com/od/religionsectarianism/f/me080209.htm

- ^ http://www.irfi.org/articles/articles_351_400/quran_does_not_mandate_hijab.htm

- ^ http://somalilandpress.com/al-azhar-wearing-hijab-islamic-duty-32603

- ^ Fisher, Mary Pat. Living Religions. New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2008.

- ^ "Is it ok to take off the kimar and niqab in front of a blind man?". Islamqa.info. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ Women revealing their adornment to men who lack physical desire retrieved 25 June 2012

- ^ Queer Spiritual Spaces: Sexuality and Sacred Places - Page 89, Kath Browne, Sally Munt, Andrew K. T. Yip - 2010

- ^ "Should the Hijab be banned in schools, public buildings or society in general? –". Debate.org. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ a b Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 35.

- ^ Evidence in the Qur'an for Covering Women's Hair, IslamOnline.

- ^ a b Hameed, Shahul. "Is Hijab a Qur’anic Commandment?," IslamOnline.net. October 9, 2003.

- ^ Syed, Ibrahim B. (2001). "Women in Islam: Hijab".

- ^ a b c Aslan, Reza, No God but God, Random House, (2005), p.65–6

- ^ a b Women and Gender in Islas: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate - Leila Ahmed - Google Boeken. Books.google.com. 1992. ISBN 9780300055832. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ Kausar Khan, "Veiled Feminism: The dating scene looks a little different from behind the veil," Current (Winter 2007): 14-15.

- ^ The Hanbali school of thought also views the face as the awrah, though this view is rejected by Hanafis, Malikis and Shafi'is.

- ^ Hsu, Shiu-Sian. "Modesty." Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an. Ed. Jane McAuliffe. Vol. 3. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, 2003. 403-405. 6 vols.

- ^ Heba G. Kotb M.D., Sexuality in Islam, PhD Thesis, Maimonides University, 2004

- ^ See collection of Qur'an translations, compared verse by verse

- ^ Javed Ahmed Ghamidi, Mizan, Chapter: The Social Law of Islam, Al-Mawrid.

- ^ a b Naik, Zakir Abdul Karim (2006). Answers To Non Muslims' Common Questions About Islam. Islamic Research Foundation. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Saleem, Shehzad (June 1999). "Wearing Silk", Renaissance-Monthly Islamic Journal, 9(6).

- ^ Whitaker, Brian (20 February 2007). "Hijab for men". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (November 7, 2006). "Headscarf issue challenges Turkey". BBC News.

- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (2007-10-02). "Women condemn Turkey constitution". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ Clark-Flory, Tracy (2007-04-23). "Head scarves to topple secular Turkey?". Salon. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ a b Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 55.

- ^ Aslan, Reza (2005). No God for God. Random House. p. 65. ISBN 1-4000-6213-6.

- ^ "Surat Al-'Ahzab". Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Aslan, Reza (2005). No God for God. Random House. p. 66. ISBN 1-4000-6213-6.

- ^ Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 56.

- ^ Bloom (2002), p.46-47

- ^ Kahf, Mohja (2008). From Royal Body the Robe was Removed: The Blessings of the Veil and the Trauma of Forced Unveiling in the Middle East. University of California Press. p. 27.

- ^ a b Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 15.

- ^ Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 28.

- ^ a b c d El Guindi, Fadwa. "Hijab". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 36.

- ^ Esposito, John (1991). Islam: The Straight Path (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 99.

- ^ Leila Ahmed, The Veil's Resurgence from the Middle East to America: A Quiet Revolution,, p.111-112, Yale University Press, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e El Guindi, Fadwa. "Ḥijāb". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Retrieved 11/10/12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Bullock, Katherine (2000). "Challenging Medial Representations of the Veil". The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences. 17 (3): 22–53.

- ^ Elsaie, Adel. "Dr". United States of Islam.

- ^ Winter, Bronwyn (2006). "The Great Hijab Coverup". Off Our Backs; a women's newsjournal. 36 (3): 38–40. JSTOR 20838653.

- ^ M. J. Gohari (2000). The Taliban: Ascent to Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 108-110.

- ^ "Tunisia's Hijab Ban Unconstitutional". 11 October 2007. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ Turkey's AKP discusses hijab ruling JUNE 06, 2008[dead link]

- ^ "Quiet end to Turkey's college headscarf ban". BBC News. December 31, 2010.

- ^ "CLOTHING ii. In the Median and Achaemenid periods" at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ El-Guindi, Fadwa, Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance, Berg, 1999

- ^ Mardell, Mark. Dutch MPs to decide on burqa ban, BBC News, January 16, 2006. Accessed June 6, 2008.

- ^ "Women and the Hijab in the Intifada", Rema Hammami Middle East Report, May–August 1990

- ^ Rubenberg, C., Palestinian Women: Patriarchy and Resistance in the West Bank (USA, 2001) p.230

- ^ Rubenberg, C., Palestinian Women: Patriarchy and Resistance in the West Bank (USA, 2001) p.231

- ^ The Pioneer, August 14, 2001, "Acid test in the face of acid attacks" Sandhya Jain[dead link]

- ^ "Kashmir women face threat of acid attacks from militants, ''Independent'', The (London), Aug 30, 2001 by Peter Popham in Delhi". Findarticles.com. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ "Kashmir women face acid attacks". BBC News. 2001-08-10. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ Molavi, Afshini The Soul of Iran, Norton, (2005), p.152: Following the mandating of the covering of hair by women in the Islamic Republic of Iran, a hijab-less woman `was shopping. A bearded young man approached me. He said he would throw acid on my face if I did not comply with the rules."

- ^ In 2006, a group in Gaza calling itself "Just Swords of Islam" is reported to have claimed it threw acid at the face of a young woman who was dressed "immodestly," and warned other women in Gaza that they must wear hijab. December 2, 2006 Gaza women warned of immodesty

- ^ Iranian journalist Amir Taheri tells of an 18-year-old college student at the American University in Beirut who on the eve of `Ashura in 1985 "was surrounded and attacked by a group of youths -- all members of Hezb-Allah, the Party of Allah. They objected to the `lax way` in which they thought she was dressed, and accused her of `insulting the blood of the martyrs` by not having her hair fully covered. Then one of the youths threw `a burning liquid` on her face." According to Taheri, "scores – some say hundreds – of women ... in Baalbek, in Beirut, in southern Lebanon and in many other Muslim cities from Tunis to Kuala Lumpur," were attacked in a similar manner from 1980 to 1986. Taheri, Amir, Holy Terror : the Inside Story of Islamic Terrorism, Adler & Adler, 1987, p.12

References

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05583-8.

- Aslan, Reza, No God But God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam, Random House, 2005

- Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (2002). Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09422-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - El Guindi, Fadwa (1999). Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance. Oxford: Berg. ISBN 1-85973-929-6.

- Elver, Hilal. The Headscarf Controversy: Secularism and Freedom of Religion (Oxford University Press; 2012); 265 pages; Criticizes policies that serve to exclude pious Muslim women from the public sphere in Turkey, France, Germany, and the United States.

- Esposito, John (2003). The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512558-4.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (February 2014) |

Media related to hijabs at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to hijabs at Wikimedia Commons- BBC drawings of different types of Islamic women's clothing

Orthodox Islam

Contemporary Muslim opinion

- Niqab is not required

- Template:PDFlink

- The great burqa/niqab/hijab debate

- QuranicPath | Hijab & Niqab Not in the Qur'an

- [1] The Myth of the 'Islamic' headscarf by Omar Hussein Ibrahim.

News articles

- Proposed Hijab Ban in Ireland

- Video debate on Lebanese TV about the Hijab Transcript

- NPR article "Dutch Weigh Ban on Traditional Islamic Dress," All Things Considered, January 31, 2006

- CBC Story "Muslim girl ejected from tournament for wearing hijab", Sunday, February 25, 2007

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic female dress |

|---|

| Types |

| Practice and law by country |

| Concepts |

| Other |