Africa: Difference between revisions

+ sg:Afrîka (Sango) |

m →External links: alphabetized Sango (sg:Afrîka) w/in interwiki list |

||

| Line 859: | Line 859: | ||

[[ru:Африка]] |

[[ru:Африка]] |

||

[[se:Afrihkká]] |

[[se:Afrihkká]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[sm:Aferika]] |

[[sm:Aferika]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[sa:अफ्रीका]] |

[[sa:अफ्रीका]] |

||

[[sco:Africae]] |

[[sco:Africae]] |

||

Revision as of 01:44, 23 September 2007

Africa is the world's second-largest and second most-populous continent, after Asia. At about 30,221,532 km² (11,668,545 mi²) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area, and 20.4% of the total land area.[1] With more than 900,000,000 people (as of 2005)[2] in 61 territories, it accounts for about 14% of the world's human population. The continent is surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Suez Canal and the Red Sea to the northeast, the Indian Ocean to the southeast, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. There are 46 countries including Madagascar, and 53 including all the island groups.

Africa, particularly central eastern Africa, is widely regarded within the scientific community to be the origin of humans and the Hominidae tree, as evidenced by the discovery of the earliest hominids, as well as later ones that have been dated to around 7 million years ago – including Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Australopithecus africanus and Homo erectus – with the earliest humans being dated to ca. 200,000 years ago, according to this view.

Africa straddles the equator and encompasses numerous climate areas; it is the only continent to stretch from the northern temperate to southern temperate zones. Because of the lack of natural regular precipitation and irrigation as well as glaciers or mountain aquifer systems, there is no natural moderating effect on the climate except near the coasts.

Etymology

Afri was the name of several peoples who dwelt in North Africa near the provincial capital, Carthage. The Roman suffix "-ca" denotes "country or land".[3]

Other etymologies that have been postulated for the ancient name 'Africa':

- the Latin word aprica, meaning "sunny";

- the Greek word aphrike, meaning "without cold." This was proposed by historian Leo Africanus (1488–1554), who suggested the Greek word phrike (φρίκη, meaning "cold and horror"), combined with the privative prefix "a-", thus indicating a land free of cold and horror.

Geography

Africa is the largest of the three great southward projections from the main mass of the Earth's exposed surface. Separated from Europe by the Mediterranean Sea, it is joined to Asia at its northeast extremity by the Isthmus of Suez (transected by the Suez Canal), 163 km (101 miles) wide.[4] (Geopolitically, Egypt's Sinai Peninsula east of the Suez Canal is often considered part of Africa, as well.[2][3]) From the most northerly point, Ras ben Sakka in Tunisia (37°21' N), to the most southerly point, Cape Agulhas in South Africa (34°51'15" S), is a distance of approximately 8,000 km (5,000 miles);[5] from Cape Verde, 17°33'22" W, the westernmost point, to Ras Hafun in Somalia, 51°27'52" E, the most easterly projection, is a distance of approximately 7,400 km (4,600 miles).[6] The coastline is 26,000 km (16,100 miles) long, and the absence of deep indentations of the shore is illustrated by the fact that Europe, which covers only 10,400,000 km² (4,010,000 square miles) – about a third of the surface of Africa – has a coastline of 32,000 km (19,800 miles).[6]

Africa's largest country is Sudan, and its smallest country is the Seychelles, an archipelago off the east coast.[7] The smallest nation on the continental mainland is The Gambia.

According to the ancient Romans, Africa lay to the west of Egypt, while "Asia" was used to refer to Anatolia and lands to the east. A definite line was drawn between the two continents by the geographer Ptolemy (85–165 AD), indicating Alexandria along the Prime Meridian and making the isthmus of Suez and the Red Sea the boundary between Asia and Africa. As Europeans came to understand the real extent of the continent, the idea of Africa expanded with their knowledge.

Climate, fauna, and flora

The climate of Africa ranges from tropical to subarctic on its highest peaks. Its northern half is primarily desert or arid, while its central and southern areas contain both savanna plains and very dense jungle (rainforest) regions. In between, there is a convergence where vegetation patterns such as sahel, and steppe dominate.

Africa boasts perhaps the world's largest combination of density and "range of freedom" of wild animal populations and diversity, with wild populations of large carnivores (such as lions, hyenas, and cheetahs) and herbivores (such as buffalo, deer, elephants, camels, and giraffes) ranging freely on primarily open non-private plains. It is also home to a variety of jungle creatures (including snakes and primates) and aquatic life (including crocodiles and amphibians).

History

Africa is considered by most paleoanthropologists to be the oldest inhabited territory on earth, with the human species originating from the continent. During the middle of the twentieth century, anthropologists discovered many fossils and evidence of human occupation perhaps as early as 7 million years ago. Fossil remains of several species of early apelike humans thought to have evolved into modern man, such as Australopithecus afarensis (radiometrically dated to approximately 3.9–3.0 million years BC),[8] Paranthropus boisei (2.3–1.4 million BC)[9] and Homo ergaster (600,000–1.9 million BC) have been discovered.[1]

The Ishango bone, dated to about 25,000 years ago, shows tallies in mathematical notation. Throughout humanity's prehistory, Africa (like all other continents) had no nation states, and was instead inhabited by groups of hunter-gatherers such as the Khoi and San.[10][11][12]

At the end of the Ice Ages, estimated to have been around 10,500 BC, the Sahara had become a green fertile valley again, and its African populations returned from the interior and coastal highlands in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, the warming and drying climate meant that by 5000 BC the Sahara region was becoming increasingly drier. The population trekked out of the Sahara region towards the Nile Valley below the Second Cataract where they made permanent or semi-permanent settlements. A major climatic recession occurred, lessening the heavy and persistent rains in Central and Eastern Africa. Since then dry conditions have prevailed in Eastern Africa, especially in Ethiopia in the last 200 years.

The domestication of cattle in Africa precedes agriculture and seems to have existed alongside hunter-gathering cultures. It is speculated that by 6000 BC cattle were already domesticated in North Africa.[13] In the Sahara-Nile complex, people domesticated many animals including the pack ass, and a small screw horned goat which was common from Algeria to Nubia.

Agriculturally, the first cases of domestication of plants for agricultural purposes occurred in the Sahel region circa 5000 BC, when sorghum and African rice began to be cultivated. Around this time, and in the same region, the small guinea fowl became domesticated.

According to the Oxford Atlas of World History, in the year 4000 BC the climate of the Sahara started to become drier at an exceedingly fast pace.[14] This climate change caused lakes and rivers to shrink rather significantly and caused increasing desertification. This, in turn, decreased the amount of land conducive to settlements and helped to cause migrations of farming communities to the more tropical climate of West Africa.[14]

By 3000 BC agriculture arose independently in both the tropical portions of West Africa, where African yams and oil palms were domesticated, and in Ethiopia, where coffee and teff became domesticated. No animals were independently domesticated in these regions, although domestication did spread there from the Sahel and Nile regions.[15] Agricultural crops were also adopted from other regions around this time as pearl millet, cowpea, groundnut, cotton, watermelon and bottle gourds began to be grown agriculturally in both West Africa and the Sahel Region while finger millet, peas, lentil and flax took hold in Ethiopia.[16]

The international phenomenon known as the Beaker culture began to affect western North Africa. Named for the distinctively shaped ceramics found in graves, the Beaker culture is associated with the emergence of a warrior mentality. North African rock art of this period depicts animals but also places a new emphasis on the human figure, equipped with weapons and adornments. People from the Great Lakes Region of Africa settled along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea to become the proto-Canaanites who dominated the lowlands between the Jordan River, the Mediterranean and the Sinai Desert.

By the 1st millennium BC ironworking had been introduced in Northern Africa and quickly began spreading across the Sahara into the northern parts of sub-saharan Africa[17] and by 500 BC metalworking began to become commonplace in West Africa, possibly after being introduced by the Carthaginians. Ironworking was fully established by roughly 500 BC in areas of East and West Africa, though other regions didn't begin ironworking until the early centuries AD. Some copper objects from Egypt, North Africa, Nubia and Ethiopia have been excavated in West Africa dating from around 500 BC, suggesting that trade networks had been established by this time.[14]

Early civilisations and trade

About 3300 BC, the historical record opens in Africa with the rise of literacy in the Pharaonic-ruled civilisation of Ancient Egypt, which continued, with varying levels of influence over other areas, until 343 BC.[18][19] Prominent civilisations at different times include Carthage, the Kingdom of Aksum, the Nubian kingdoms, the empires of the Sahel (Kanem-Bornu, Ghana, Mali, and Songhai), Great Zimbabwe, and the Kongo.[20][21]

After the Sahara had become a desert it did not present an impenetrable barrier for travellers between north and south. Even prior to the introduction of the camel[22] the use of oxen for desert crossing was common, and trade routes followed oases that were strung across the desert. The camel was first brought to Egypt by the Persians after 525 BC, although large herds did not become common enough in North Africa to establish the trans-Saharan trade until the eighth century AD.[23] The Sanhaja Berbers were the first to exploit this.

Pre-colonial Africa possessed perhaps as many as 10,000 different states and polities[24] characterised by different sorts of political organisation and rule. These included small family groups of hunter-gatherers such as the San people of southern Africa; larger, more structured groups such as the family clan groupings of the Bantu-speaking people of central and southern Africa and heavily-structured clan groups in the Horn of Africa, the Sahelian Kingdoms, and autonomous city-states such as the Swahili coastal trading towns of the East African coast, whose trade network extended as far as China.

In 1418, the fifth expedition by Chinese admiral Zheng He reached Africa's east coast. The two later Zheng He voyages, the last in 1432, also sailed to East Africa. The Chinese travelled at least as far as Malindi in Kenya. In 1482, the Portuguese established the first of many trading stations along the coast of Ghana at Elmina. The chief commodities dealt in were slaves, gold, ivory and spices. The European discovery of the Americas in 1492 was followed by a great development of the slave trade, which, before the Portuguese era, had been an overland trade almost exclusively, and never confined to any one continent.[25]

In West Africa, the decline of the Atlantic slave trade in the 1820's caused dramatic economic shifts in local polities. The gradual decline of slave-trading, prompted by a lack of demand for slaves in the New World, increasing anti-slavery legislation in Europe and America, and the British navy's increasing presence off the West African coast, obliged African states to adopt new economies. The largest powers of West Africa: the Asante Confederacy, the Kingdom of Dahomey, and the Oyo Empire, adopted different ways of adapting to the shift. Asante and Dahomey concentrated on the development of "legitimate commerce" in the form of palm oil, cocoa, timber and gold, forming the bedrock of West Africa's modern export trade. The Oyo Empire, unable to adapt, collapsed into civil wars.[26]

Pre-colonial exploration

In the mid-nineteenth century, European explorers became interested in exploring the heart of the continent and opening the area for trade, mining and other commercial exploitation. In addition, there was a desire to convert the inhabitants to Christianity. The central area of Africa was still largely unknown to Europeans at this time. David Livingstone explored the continent between 1852 and his death in 1873; amongst other claims to fame, he was the first European to see the Victoria Falls. A prime goal for explorers was to locate the source of the River Nile. Expeditions by Burton and Speke (1857–1858) and Speke and Grant (1863) located Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria. The latter was eventually proven as the main source of the Nile. With subsequent expeditions by Baker and Stanley, Africa was well explored by the end of the century and this was to lead the way for the colonization which followed.

Colonialism and the "scramble for Africa"

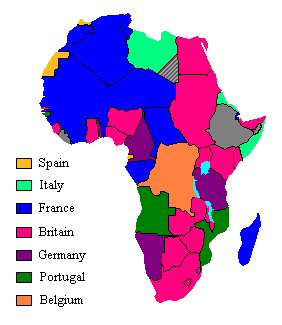

In the late nineteenth century, the European imperial powers engaged in a major territorial scramble and occupied most of the continent, creating many colonial nation states, and leaving only two independent nations: Liberia, an independent state partly settled by African Americans; and Orthodox Christian Ethiopia (known to Europeans as "Abyssinia"). Colonial rule by Europeans would continue until after the conclusion of World War II, when all colonial states gradually obtained formal independence.

Colonialism had a destabilising effect on a number of ethnic groups that is still being felt in African politics. Before European influence, national borders were not much of a concern, with Africans generally following the practice of other areas of the world, such as the Arabian Peninsula, where a group's territory was congruent with its military or trade influence. The European insistence of drawing borders around territories to isolate them from those of other colonial powers often had the effect of separating otherwise contiguous political groups, or forcing traditional enemies to live side by side with no buffer between them. For example, although the Congo River appears to be a natural geographic boundary, there were groups that otherwise shared a language, culture or other similarity living on both sides. The division of the land between Belgium and France along the river isolated these groups from each other. Those who lived in Saharan or Sub-Saharan Africa and traded across the continent for centuries often found themselves crossing borders that existed only on European maps.

In nations that had substantial European populations, for example Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and South Africa, systems of second-class citizenship were often set up in order to give Europeans political power far in excess of their numbers. In the Congo Free State, personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium, the native population was submitted to inhumane treatment, and a near slavery status assorted with forced labor. However, the lines were not always drawn strictly across racial lines. In Liberia, citizens who were descendants of American slaves had a political system for over 100 years that gave ex-slaves and natives to the area roughly equal legislative power despite the fact the ex-slaves were outnumbered ten to one in the general population. The inspiration for this system was the United States Senate, which had balanced the power of free and slave states despite the much-larger population of the former.

Europeans often altered the local balance of power, created ethnic divides where they did not previously exist, and introduced a cultural dichotomy detrimental to the native inhabitants in the areas they controlled. For example, in what are now Rwanda and Burundi, two ethnic groups Hutus and Tutsis had merged into one culture by the time German colonists had taken control of the region in the nineteenth century. No longer divided by ethnicity as intermingling, intermarriage, and merging of cultural practices over the centuries had long since erased visible signs of a culture divide, Belgium instituted a policy of racial categorization upon taking control of the region, as racially based categorization and philosophies were a fixture of the European culture of that time. The term Hutu originally referred to the agricultural-based Bantu-speaking peoples that moved into present day Rwanda and Burundi from the West, and the term Tutsi referred to Northeastern cattle-based peoples that migrated into the region later. The terms described a person's economic class; individuals who owned roughly 10 or more cattle were considered Tutsi, and those with fewer were considered Hutu, regardless of ancestral history. This was not a strict line but a general rule of thumb, and one could move from Hutu to Tutsi and vice versa.

The Belgians introduced a racialized system; European-like features such as fairer skin, ample height, narrow noses were seen as more ideally Hamitic, and belonged to those people closest to Tutsi in ancestry, who were thus given power amongst the colonised peoples. Identity cards were issued based on this philosophy.

Tunisia was the first country in Africa to gain Independence, doing so in 1956. The decades-long struggle for independence from France was led by Habib Bourguiba, founder of the Republic of Tunisia.

Post-colonial Africa

Today, Africa contains 53 independent and sovereign countries, most of which still have the borders drawn during the era of European colonialism.

Since colonialism, African states have frequently been hampered by instability, corruption, violence, and authoritarianism. The vast majority of African nations are republics that operate under some form of the presidential system of rule. However, few of them have been able to sustain democratic governments, and many have instead cycled through a series of coups, producing military dictatorships. A number of Africa's post-colonial political leaders were military generals who were poorly educated and ignorant on matters of governance. Great instability, however, was mainly the result of marginalization of other ethnic groups and graft under these leaders. For political gain, many leaders fanned ethnic conflicts that had been exacerbated, or even created, by colonial rule. In many countries, the military was perceived as being the only group that could effectively maintain order, and it ruled many nations in Africa during the 1970's and early 1980's. During the period from the early 1960's to the late 1980's, Africa had more than 70 coups and 13 presidential assassinations. Border and territorial disputes were also common, with the European-imposed borders of many nations being widely contested through armed conflicts.

Cold War conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union, as well as the policies of the International Monetary Fund, also played a role in instability. When a country became independent for the first time, it was often expected to align with one of the two superpowers. Many countries in Northern Africa received Soviet military aid, while many in Central and Southern Africa were supported by the United States, France or both. The 1970's saw an escalation, as newly independent Angola and Mozambique aligned themselves with the Soviet Union and the West and South Africa sought to contain Soviet influence by funding insurgency movements. Some countries were ruled by communist parties that sought to impose Soviet policies resulting in atrocities such as the Ethiopian famine of 1985–89. [citation needed]

AIDS has also been a prevalent issue in post-colonial Africa. See article AIDS in Africa.

Politics

Template:Africa countries imagemap The African Union (AU) is a federation consisting of all of Africa's states except Morocco. The union was formed, with Addis Ababa as its headquarters, on June 26 2001. In July 2004, the African Union's Pan-African Parliament (PAP) was relocated to Midrand, in South Africa, but the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights remained in Addis Ababa. There is a policy in effect to decentralise the African Federation's institutions so that they are shared by all the states.

The African Union, not to be confused with the AU Commission, is formed by an Act of Union which aims to transform the African Economic Community, a federated commonwealth, into a state, under established international conventions. The African Union has a parliamentary government, known as the African Union Government, consisting of legislative, judicial and executive organs, and led by the African Union President and Head of State, who is also the President of the Pan African Parliament. A person becomes AU President by being elected to the PAP, and subsequently gaining majority support in the PAP.

President Gertrude Ibengwe Mongella is the Head of State and Chief of Government of the African Union, by virtue of the fact that she is the President of the Pan African Parliament. She was elected by Parliament in its inaugural session in March 2004, for a term of five years. The PAP consists of 265 legislators, five from each constituent state of the African Union. Over 21% of the members are female.[citation needed]

The powers and authority of the President of the African Parliament derive from the Union Act, and the Protocol of the Pan African Parliament, as well as the inheritance of presidential authority stipulated by African treaties and by international treaties, including those subordinating the Secretary General of the OAU Secretariat (AU Commission) to the PAP. The government of the AU consists of all-union (federal), regional, state, and municipal authorities, as well as hundreds of institutions, that together manage the day-to-day affairs of the institution.

Failed state policies, inequitable global trade practices, and the effects of global climate change have resulted in many widespread famines, and significant portions of Africa remain with distribution systems unable to disseminate enough food or water for the population to survive. What had before colonialism been the source for 90% of the world's gold has become the poorest continent on earth, its former riches enjoyed by those on other continents. The spread of disease is also rampant, especially the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the associated acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), which has become a deadly pandemic on the continent.

There are clear signs of increased networking among African organisations and states. In the civil war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (former Zaire), rather than rich, non-African countries intervening, neighbouring African countries became involved (see also Second Congo War). Since the conflict began in 1998, the estimated death toll has reached 4 million.[27] Political associations such as the African Union offer hope for greater co-operation and peace between the continent's many countries. Extensive human rights abuses still occur in several parts of Africa, often under the oversight of the state. Most of such violations occur for political reasons, often as a side effect of civil war. Countries where major human rights violations have been reported in recent times include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, and Côte d'Ivoire.

Economy

Although being a continent with plenty of natural resources, Africa remains the world's poorest and most underdeveloped continent, due largely to the effects of the slave trade, corrupt governments, failed central planning, the international trade regime and geopolitics; as well as widespread human rights violations, the negative effects of colonialism, despotism and conflict (ranging from war to civil war to guerrilla to genocide).[28] According to the United Nations' Human Development Report in 2003, the bottom 25 ranked nations (151st to 175th) were all African nations.[29]

Some areas, notably Botswana and South Africa, have experienced economic success. The latter has a wealth of natural resources, being the world's leading producers of both gold and diamonds, and a well-established legal system. South Africa also has access to financial capital, numerous markets, skilled labor, and first world infrastructure in much of the country and the opening of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

Over a quarter of Botswana's budget (also a major diamond producer) goes toward improving the infrastructure of Gaborone, the nation's capital, largest city, and one of the world's fastest growing cities. Other African countries are making comparable progress, such as Ghana, Kenya, Cameroon and Egypt.

Nigeria sits on one of the largest proven oil reserves in the world and has the highest population among nations in Africa, with one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

From 1995 to 2005, economic growth picked up, averaging 5% in 2005. However, some countries experienced much higher growth (10+%) in particular, Angola, Sudan and Equatorial Guinea, all three of which have recently begun extracting their petroleum reserves.

Demographics

The last 40 years have seen a rapid increase in population; hence, this population is relatively young. In some African states half or more of the population is under 25 years old.[30]

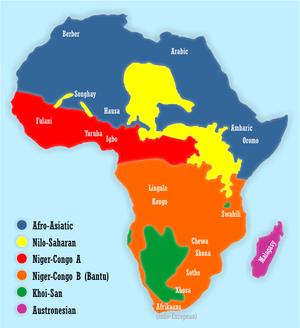

Speakers of Bantu languages (part of the Niger-Congo family) are the majority in southern, central and East Africa proper. But there are also several Nilotic groups in East Africa, and a few remaining indigenous Khoisan ('San' or 'Bushmen') and Pygmy peoples in southern and central Africa, respectively. Bantu-speaking Africans also predominate in Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, and are found in parts of southern Cameroon and southern Somalia. In the Kalahari Desert of Southern Africa, the distinct people known as the Bushmen (also "San", closely related to, but distinct from "Hottentots") have long been present. The San are physically distinct from other Africans and are the indigenous people of southern Africa. Pygmies are the pre-Bantu indigenous peoples of central Africa.

The peoples of North Africa comprise two main groups; Berber and Arabic-speaking peoples in the west, and Egyptians in the east. The Arabs who arrived in the seventh century introduced the Arabic language and Islam to North Africa. The Semitic Phoenicians, the European Greeks, Romans and Vandals settled in North Africa as well. Berbers still make up the majority in Morocco, while they are a significant minority within Algeria. They are also present in Tunisia and Libya. The Tuareg and other often-nomadic peoples are the principal inhabitants of the Saharan interior of North Africa. Nubians are a Nilo-Saharan-speaking group (though many also speak Arabic), who developed an ancient civilisation in northeast Africa.

During the past century or so, small but economically important colonies of Lebanese and Chinese have also developed in the larger coastal cities of West and East Africa, respectively.

Some Ethiopian and Eritrean groups (like the Amhara and Tigrayans, collectively known as "Habesha") speak Semitic languages. The Oromo and Somali peoples speak Cushitic languages, but some Somali clans trace their founding to legendary Arab founders. Sudan and Mauritania are divided between a mostly Arabized north and a native African south (although the "Arabs" of Sudan clearly have a predominantly native African ancestry themselves). Some areas of East Africa, particularly the island of Zanzibar and the Kenyan island of Lamu, received Arab Muslim and Southwest Asian settlers and merchants throughout the Middle Ages and in antiquity.

Beginning in the sixteenth century, Europeans such as the Portuguese and Dutch began to establish trading posts and forts along the coasts of western and southern Africa. Eventually, a large number of Dutch augmented by French Huguenots and Germans settled in what is today South Africa. Their descendants, the Afrikaners and the Coloureds, are the largest European-descended groups in Africa today. In the nineteenth century, a second phase of colonisation brought a large number of French and British settlers to Africa. The Portuguese settled mainly in Angola, but also in Mozambique. The French settled in large numbers in Algeria where they became known collectively as pieds-noirs, and on a smaller scale in other areas of North and West Africa as well as in Madagascar. The British settled chiefly in South Africa as well as the colony of Rhodesia, and in the highlands of what is now Kenya. Germans settled in what is now Tanzania and Namibia, and there is still a population of German-speaking white Namibians. Smaller numbers of European soldiers, businessmen, and officials also established themselves in administrative centers such as Nairobi and Dakar. Decolonisation during the 1960's often resulted in the mass emigration of European-descended settlers out of Africa – especially from Algeria, Angola, Kenya and Rhodesia. However, in South Africa and Namibia, the white minority remained politically dominant after independence from Europe, and a significant population of Europeans remained in these two countries even after democracy was finally instituted at the end of the Cold War. South Africa has also become the preferred destination of white Anglo-Zimbabweans, and of migrants from all over southern Africa.

European colonisation also brought sizeable groups of Asians, particularly people from the Indian subcontinent, to British colonies. Large Indian communities are found in South Africa, and smaller ones are present in Kenya, Tanzania, and some other southern and East African countries. The large Indian community in Uganda was expelled by the dictator Idi Amin in 1972, though many have since returned. The islands in the Indian Ocean are also populated primarily by people of Asian origin, often mixed with Africans and Europeans. The Malagasy people of Madagascar are a Austronesian people, but those along the coast are generally mixed with Bantu, Arab, Indian and European origins. Malay and Indian ancestries are also important components in the group of people known in South Africa as Cape Coloureds (people with origins in two or more races and continents).

Languages

By most estimates, Africa contains well over a thousand languages (some have estimated over two thousand), most of African origin and a few of European origin. Africa is the most polyglot continent in the world; it is not rare to find individuals there who fluently speak not only several African languages, but one or two European ones as well. There are four major language families native to Africa.

- The Afro-Asiatic languages are a language family of about 240 languages and 285 million people widespread throughout East Africa, North Africa, the Sahel, and Southwest Asia.

- The Nilo-Saharan language family consists of more than a hundred languages spoken by 30 million people. Nilo-Saharan languages are mainly spoken in Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, Uganda, and northern Tanzania.

- The Niger-Congo language family covers much of Sub-Saharan Africa and is probably the largest language family in the world in terms of different languages. A substantial number of them are the Bantu languages spoken in much of sub-Saharan Africa.

- The Khoisan languages number about fifty and are spoken in Southern Africa by approximately 120,000 people. Many of the Khoisan languages are endangered. The Khoi and San peoples are considered the original inhabitants of this part of Africa.

Following colonialism, nearly all African countries adopted official languages that originated outside the continent, although several countries nowadays also use various languages of native origin (such as Swahili) as their official language. In numerous countries, English and French (see African French) are used for communication in the public sphere such as government, commerce, education and the media. Arabic, Portuguese, Afrikaans and Malagasy are other examples of originally non-African languages that are used by millions of Africans today, both in the public and private spheres.

Culture

African culture is characterised by a vastly diverse patchwork of social values, ranging from extreme patriarchy to extreme matriarchy, sometimes in tribes existing side by side.

Modern African culture is characterised by conflicted responses to Arab nationalism and European imperialism. Increasingly, beginning in the late 1990's, Africans are reasserting their identity. In North Africa especially the rejection of the label Arab or European has resulted in an upsurge of demands for special protection of indigenous Amazigh languages and culture in Morocco, Egypt, Algeria and Tunisia. The emergence of Pan-Africanism since the fall of apartheid has heightened calls for a renewed sense of African identity. In South Africa, intellectuals from settler communities of European descent increasingly identify as African for cultural rather than geographical or racial reasons. Famously, some have undergone ritual ceremonies to become members of the Zulu or other community.

Much of the traditional African cultures have become impoverished as a result of years of neglect and suppression by colonial and neo-colonial regimes. There is now a resurgence in the attempts to rediscover and revalourise African traditional cultures, under such movements as the African Renaissance led by Thabo Mbeki, Afrocentrism led by an influential group of scholars including Molefi Asante, as well as the increasing recognition of traditional spiritualism through decriminalization of Voudoo and other forms of spirituality. In recent years African traditional culture has become synonymous with rural poverty and subsistence farming.

Urban culture in Africa, now associated with Western values, is a great contrast from traditional African urban culture which was once rich and enviable even by modern Western standards. African cities such as Loango, M'banza Congo, Timbuktu, Thebes, Meroe and others had served as the world's most affluent urban and industrial centers, clean, well-laid out, and full of universities, libraries, and temples.

The main and most enduring cultural fault-line in Africa is the divide between traditional pastoralists and agriculturalists. The divide is not, and never was based on economic competition, but rather on the colonial racial policy that identified pastoralists as constituting a different race from agriculturalists, and enforcing a form of apartheid between the two cultures beginning in the 1880's and lasting until the 1960's. Although European colonial powers were largely industrial, many of the administrators and philosophers, whose writings provided rationale for colonialism, applied quasi-scientific eugenics policies and racist politics on Africans in experiments of misguided social engineering.

Most of the racial recategorisation of Africans to fit European stereotypes was contradictory and incoherent. However, because their legalism and laws that emanated from these policies were backed by police force, the scientific establishment and economic power, Africans reacted by either conforming to the new rules, or rejecting them in favour of Pan-Africanism. All across Africa communities and individuals were measured by colonial eugenics boards and reassigned identities and ethnicities based on pseudoscience. The schools taught that in general Africans who resembled Europeans in some physical or cultural aspect were superior to other Africans and deserved more privileges. This caused animosity, incited by other Europeans – socialists and communists – who identified Africans according to dubious classes also modeled on European concerns.

The easiest way to divide Africans was along economic lines. Pastoralists, agriculturalists, hunter-gatherers and Westernised Africans, all formed distinctly identifiable cultures each of which came to play a different and disfiguring role in Africa's modern politics. The Westernised Africans, specifically Senegalese and Sudanese Nubians from urban centers such as Dakar and Khartoum, were used to serve as the bulk of colonial troops against the rural Africans. Pastoralists were radicalised by the wholesale confiscation of grazing lands in favour of plantations. Agriculturalists came into conflict for land and water with pastoralists after the traditional sharing arrangements had been destroyed by colonial policies.

In addition, a growing body of speculative anthropology and race science made false claims about the superiority and inferiority of Africans with different cultural and economic backgrounds. The vast majority of the scholarship on Africa was extraneous and catered to the demand for exotic and outlandish representations of Africa. The enforcement of the government decrees and policies tended to produce effects that confirmed the prejudices of the European colonialists.

African art and architecture reflect the diversity of African cultures. The oldest existing examples of art from Africa are 75,000 year old beads made from Nassarius shells that were found in Blombos Cave. The Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt was the world's tallest structure for 4,000 years until the completion of Lincoln Cathedral around 1300. The Ethiopian complex of monolithic churches at Lalibela, of which the Church of St. George is representative, is regarded as another marvel of engineering.

Music and dance

The music of Africa is one of its most dynamic art forms. Egypt has long been a cultural focus of the Arab world, while remembrance of the rhythms of sub-Saharan Africa, in particular West Africa, was transmitted through the Atlantic slave trade to modern samba, blues, jazz, reggae, rap, and rock and roll. Modern music of the continent includes the highly complex choral singing of southern Africa and the dance rhythms of soukous, dominated by the music of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Recent developments include the emergence of African hip hop, in particular a form from Senegal blended with traditional mbalax, and Kwaito, a South African variant of house music. Afrikaans music, also found in South Africa, is idiosyncratic being composed mostly of traditional Boer music, while more recent immigrant communities have introduced the music of their homes to the continent.

Indigenous musical and dance traditions of Africa are maintained by oral traditions and they are distinct from the music and dance styles of North Africa and Southern Africa. Arab influences are visible in North African music and dance and in Southern Africa western influences are apparent due to colonisation.

Many African languages are tone languages, in which pitch level determines the meaning. This also finds expression in African musical melodies and rhythms. A variety of musical instruments are used, including drums (most widely used), bells, musical bow, lute, flute, and trumpet.

African dances are important mode of communication and dancers use gestures, masks, costumes, body painting and a number of visual devices. With urbanisation and modernisation, modern African dance and music exhibit influences assimilated from several other cultures.

Legends of Africa

Africa has a wealth of history which is largely unrecorded. Many myths, fables and legends abound.

Sports

53 African countries have football teams in the Confederation of African Football, while Cameroon, Senegal, and Ghana have moved beyond the knockout stage of recent FIFA World Cups. South Africa will host the 2010 World Cup tournament, and will be the first African country to do so.

Cricket is also popular in some African nations, with South Africa and Zimbabwe holding Test status and Kenya also being a significant force in One-Day International cricket. The three countries jointly hosted the 2003 Cricket World Cup.

A number of African nations, especially Ethiopia, Kenya, and Morocco, have fielded world-class long-distance runners such as Abebe Bikila and Cosmas Ndeti.

The South Africa hosted and won the 1995 Rugby World Cup.

Religion

Different Africans profess a wide variety of religious beliefs[31] and it is difficult to conclude accurate statistics about religious demography in Africa as a whole. Estimations from World Book Encyclopedia claim that there are 150 million African Muslims and 130 million African Christians, while Encyclopedia Britannica estimates that approximately 46.5% of all Africans are Christians and another 40.5% are Muslims with roughly 11.8% of Africans following indigenous African religions. A small number of Africans are Hindu or Baha'i, or have beliefs from the Judaic tradition. Examples of African Jews are the Beta Israel, Lemba peoples and the Abayudaya of Eastern Uganda.

The indigenous Sub-Saharan African religions tend to revolve around animism and ancestor worship. A common thread in traditional belief systems was the division of the spiritual world into "helpful" and "harmful". Helpful spirits are usually deemed to include ancestor spirits that help their descendants, and powerful spirits that protect entire communities from natural disaster or attacks from enemies; whereas harmful spirits include the souls of murdered victims who were buried without the proper funeral rites, and spirits used by hostile spirit mediums to cause illness among their enemies. While the effect of these early forms of worship continues to have a profound influence, belief systems have evolved as they interact with other religions.

The formation of the Old Kingdom of Egypt in the third millennium BCE marked the first known complex religious system on the continent. Around the ninth century, Carthage (in present-day Tunisia) was founded by the Phoenicians, and went on to become a major cosmopolitan center where deities from neighboring Egypt, Rome and the Etruscan city-states were worshipped. Today, many Jewish peoples also live in North Africa, particularly in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco.

The founding of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria is traditionally dated to the mid-first century, while the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Church officially date from the fourth century. These are thus some of the first established Christian churches in the world. At first, Christian Orthodoxy made gains in modern-day Sudan and other neighbouring regions. However, after the spread of Islam, growth was slow and restricted to the highlands.

Many Sub-Saharan Africans were converted to Western Christianity during the colonial period. In the last decades of the twentieth century, various sects of Charismatic Christianity rapidly grew. A number of Roman Catholic African bishops were mentioned as possible papal candidates in 2005. African Christians appear to be more socially conservative than their co-religionists in much of the industrialized world, which has quite recently led to tension within denominations such as the Anglican and Methodist Churches.

The African Initiated Churches have experienced significant growth in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Islam entered Africa as Arab Muslims conquered North Africa between 640 and 710, beginning with Egypt. They settled in Mogadishu, Melinde, Mombasa, Kilwa, and Sofala, following the sea trade down the coast of East Africa, and diffusing through the Sahara desert into the interior of Africa -- following in particular the paths of Muslim traders. Muslims were also among the Asian peoples who later settled in British-ruled Africa. During colonial times, Christianity had success in converting those who followed traditional religions but had very little success in converting Muslims, who took advantage of the urbanization and increase in trade to settle in new areas and spread their faith. As a result, Islam in sub-Saharan Africa probably doubled between 1869 and 1914.[32]

Islam continued this tremendous growth into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Today, backed by gulf oil cash, Muslims have increased success in proselytizing, with a growth rate, by some estimates, that is twice as fast as Christianity in Africa.[33]

Territories and regions

The countries in this table are categorised according to the scheme for geographic subregions used by the United Nations, and data included are per sources in cross-referenced articles. Where they differ, provisos are clearly indicated.

|

|

| Name of region[34] and territory, with flag |

Area (km²) |

Population (1 July 2002 est.) |

Population density (per km²) |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Africa: | ||||

| 27,830 | 6,373,002 | 229.0 | Bujumbura | |

| 2,170 | 614,382 | 283.1 | Moroni | |

| 23,000 | 472,810 | 20.6 | Djibouti | |

| 121,320 | 4,465,651 | 36.8 | Asmara | |

| 1,127,127 | 67,673,031 | 60.0 | Addis Ababa | |

| 582,650 | 31,138,735 | 53.4 | Nairobi | |

| 587,040 | 16,473,477 | 28.1 | Antananarivo | |

| 118,480 | 10,701,824 | 90.3 | Lilongwe | |

| 2,040 | 1,200,206 | 588.3 | Port Louis | |

| 374 | 170,879 | 456.9 | Mamoudzou | |

| 801,590 | 19,607,519 | 24.5 | Maputo | |

| 2,512 | 743,981 | 296.2 | Saint-Denis | |

| 26,338 | 7,398,074 | 280.9 | Kigali | |

| 455 | 80,098 | 176.0 | Victoria | |

| 637,657 | 7,753,310 | 12.2 | Mogadishu | |

| 945,087 | 37,187,939 | 39.3 | Dodoma | |

| 236,040 | 24,699,073 | 104.6 | Kampala | |

| 752,614 | 9,959,037 | 13.2 | Lusaka | |

| 390,580 | 11,376,676 | 29.1 | Harare | |

| Middle Africa: | ||||

| 1,246,700 | 10,593,171 | 8.5 | Luanda | |

| 475,440 | 16,184,748 | 34.0 | Yaoundé | |

| 622,984 | 3,642,739 | 5.8 | Bangui | |

| 1,284,000 | 8,997,237 | 7.0 | N'Djamena | |

| 342,000 | 2,958,448 | 8.7 | Brazzaville | |

| 2,345,410 | 55,225,478 | 23.5 | Kinshasa | |

| 28,051 | 498,144 | 17.8 | Malabo | |

| 267,667 | 1,233,353 | 4.6 | Libreville | |

| 1,001 | 170,372 | 170.2 | São Tomé | |

| Northern Africa: | ||||

| 2,381,740 | 32,277,942 | 13.6 | Algiers | |

| 1,001,450 | 70,712,345 | 70.6 | Cairo | |

| 1,759,540 | 5,368,585 | 3.1 | Tripoli | |

| 446,550 | 31,167,783 | 69.8 | Rabat | |

| 2,505,810 | 37,090,298 | 14.8 | Khartoum | |

| 163,610 | 9,815,644 | 60.0 | Tunis | |

| 266,000 | 256,177 | 1.0 | El Aaiún | |

| European dependencies in Northern Africa: | ||||

| 7,492 | 1,694,477 | 226.2 | Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Santa Cruz de Tenerife | |

| 20 | 71,505 | 3,575.2 | — | |

| 797 | 245,000 | 307.4 | Funchal | |

| 12 | 66,411 | 5,534.2 | — | |

| Southern Africa: | ||||

| 600,370 | 1,591,232 | 2.7 | Gaborone | |

| 30,355 | 2,207,954 | 72.7 | Maseru | |

| 825,418 | 1,820,916 | 2.2 | Windhoek | |

| 1,219,912 | 43,647,658 | 35.8 | Bloemfontein, Cape Town, Pretoria[41] | |

| 17,363 | 1,123,605 | 64.7 | Mbabane | |

| Western Africa: | ||||

| 112,620 | 6,787,625 | 60.3 | Porto-Novo | |

| 274,200 | 12,603,185 | 46.0 | Ouagadougou | |

| 4,033 | 408,760 | 101.4 | Praia | |

| 322,460 | 16,804,784 | 52.1 | Abidjan, Yamoussoukro[42] | |

| 11,300 | 1,455,842 | 128.8 | Banjul | |

| 239,460 | 20,244,154 | 84.5 | Accra | |

| 245,857 | 7,775,065 | 31.6 | Conakry | |

| 36,120 | 1,345,479 | 37.3 | Bissau | |

| 111,370 | 3,288,198 | 29.5 | Monrovia | |

| 1,240,000 | 11,340,480 | 9.1 | Bamako | |

| 1,030,700 | 2,828,858 | 2.7 | Nouakchott | |

| 1,267,000 | 10,639,744 | 8.4 | Niamey | |

| 923,768 | 129,934,911 | 140.7 | Abuja | |

| 410 | 7,317 | 17.8 | Jamestown | |

| 196,190 | 10,589,571 | 54.0 | Dakar | |

| 71,740 | 5,614,743 | 78.3 | Freetown | |

| 56,785 | 5,285,501 | 93.1 | Lomé | |

| Total | 30,368,609 | 843,705,143 | 27.8 | |

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Sayre, April Pulley. (1999) Africa, Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 0-7613-1367-2.

- ^ "World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision" United Nations (Department of Economic and Social Affairs, population division)

- ^ Consultos.com etymology

- ^ Drysdale, Alasdair & Gerald H. Blake. (1985) The Middle East and North Africa, Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-503538-0.

- ^ Lewin, Evans. (1924) Africa, Clarendon press.

- ^ a b (1998) Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary (Index), Merriam-Webster. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-87779-546-0.

- ^ Hoare, Ben. (2002) The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia, Kingfisher Publications. p. 11. ISBN 0-7534-5569-2.

- ^ Kimbel, William H. & Yoel Rak & Donald C. Johanson. (2004) The Skull of Australopithecus Afarensis, Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-515706-0.

- ^ Tudge, Colin. (2002) The Variety of Life., Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860426-2.

- ^ Sertima, Ivan Van. (1995) Egypt: Child of Africa/S V12 (Ppr), Transaction Publishers. pp. 324-325. ISBN 1-56000-792-3.

- ^ Mokhtar, G. (1990) UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. II, Abridged Edition: Ancient Africa, University of California Press. ISBN 0-85255-092-8.

- ^ Eyma, A. K. & C. J. Bennett. (2003) Delts-Man in Yebu: Occasional Volume of the Egyptologists' Electronic Forum No. 1, Universal Publishers. p. 210. SBN 1-58112-564-X.

- ^ Diamond, Jared. (1999) "Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York:Norton, pp.167.

- ^ a b c O'Brien, Patrick K. (General Editor). Oxford Atlas of World History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. pp.22-23

- ^ Diamond, Jared. (1999) "Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York:Norton, pp.100.

- ^ Diamond, Jared. (1999) "Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York:Norton, pp.126–127.

- ^ Martin and O'Meara. "Africa, 3rd Ed." Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1995. http://princetonol.com/groups/iad/lessons/middle/history1.htm#Irontechnology

- ^ Hassan, Fekri A. (2002) Droughts, Food and Culture, Springer. p. 17. ISBN 0-306-46755-0.

- ^ McGrail, Sean. (2004) Boats of the World, Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 0-19-927186-0.

- ^ Fage, J. D. (1979) The Cambridge History of Africa, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-21592-7.

- ^ Oliver, Roland & Anthony Atmore. (1994) Africa Since 1800, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42970-6.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N. (2001) The Encyclopedia of World History, Houghton Mifflin Books. p. 16. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

- ^ McEvedy, Colin (1980) Atlas of African History, p. 44. ISBN 0-87196-480-5.

- ^ "The Fate of Africa - A Survey of Fifty Years of Independence" (html). washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Oliver, Roland. (1977) The Cambridge History of Africa, Cambridge University Press. p. 453. ISBN 0-521-20981-1.

- ^ Simon, Julian L. (1995) State of Humanity, Blackwell Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 1-55786-585-X.

- ^ The Deadliest War In The World

- ^ Richard Sandbrook, The Politics of Africa's Economic Stagnation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1985 passim

- ^ http://hdr.undp.org/

- ^ Africa Population Dynamics

- ^ "African Religion on the Internet", Stanford University

- ^ Bulliet, Richard, Pamela Crossley, Daniel Headrick, Steven Hirsch, Lyman Johnson, and David Northrup. The Earth and Its Peoples. 3. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005. ISBN 0-618-42770-8

- ^ [1]

- ^ Continental regions as per UN categorisations/map.

- ^ Egypt is generally considered a transcontinental country in Northern Africa (UN region) and Western Asia; population and area figures are for African portion only, west of the Suez Canal.

- ^ Western Sahara is disputed between the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, who administer a minority of the territory, and Morocco, who occupy the remainder.

- ^ The Spanish Canary Islands, of which Las Palmas de Gran Canaria are Santa Cruz de Tenerife are co-capitals, are often considered part of Northern Africa due to their relative proximity to Morocco and Western Sahara; population and area figures are for 2001.

- ^ The Spanish exclave of Ceuta is surrounded on land by Morocco in Northern Africa; population and area figures are for 2001.

- ^ The Portuguese Madeira Islands are often considered part of Northern Africa due to their relative proximity to Morocco; population and area figures are for 2001.

- ^ The Spanish exclave of Melilla is surrounded on land by Morocco in Northern Africa; population and area figures are for 2001.

- ^ Bloemfontein is the judicial capital of South Africa, while Cape Town is its legislative seat, and Pretoria is the country's administrative seat.

- ^ Yamoussoukro is the official capital of Côte d'Ivoire, while Abidjan is the de facto seat.

References

- "Africa". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World Online. 2005. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bibliography

- Clark, J. Desmond (1970). The Prehistory of Africa. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500020692.

- Crowder, Michael (1978). The Story of Nigeria. London: Faber. ISBN 9780571049479.

- Davidson, Basil (1966). The African past; chronicles from antiquity to modern times. Harmondsworth: Penguin. OCLC 2016817.

- Gordon, April A. (1996). Understanding contemporary Africa. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 9781555875473.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Khapoya, Vincent B. (1998). The African experience: an introduction. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780137458523.

External links

- News

- allAfrica.com current news, events and statistics

- AfricaFront.com African news articles, African journalists

- BBC News In Depth - Africa 2005: Time for Change?

- Yale Economic Review Africa:Failed Economic History

- Directories

- Library of Congress - African & Middle Eastern Reading Room

- Open Directory Project - Africa directory category

- Stanford University - Africa South of the Sahara

- The Index on Africa directory from The Norwegian Council for Africa

- Politics

- Africa Action Africa Action is the oldest organization in the United States working on African affairs. It is a national organization that works for political, economic and social justice in Africa.

- Commission for Africa

- African Unification Front

- Working class history in Africa -- people's and grassroots histories

- Business

- Business Action for Africa - Business Action for Africa is an international alliance of businesses, business organisations, non-government organisations, governments, donors and academics, working together to accelerate growth and poverty reduction in Africa.

- Sports

- Tourism