Liberalism: Difference between revisions

additions and amendations to introduction |

m typo |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

The [[American Revolution]] and the [[French Revolution]] used liberal philosophy to justify the violent overthrow of autocratic rule, paving the way for the development of [[History of liberalism|liberalism as a governing ideology]]. The 19th century saw liberal governments established in nations across [[Liberalism in Europe|Europe]], [[Liberalism and conservatism in Latin America|Latin America]], and [[Liberalism in the United States|North America]]. In this period it is associated with the political theory of [[James Madison]], [[Thomas Jefferson]], and with the most progressive wing of the British [[Whig]] party. It was also increasingly associated with [[political economy]] based on the work of [[Adam Smith]] and the rise of the idea of [[Laissez-Faire]] economic policy, and in continental Europe with the ideas of [[Jacobinism]] and the philosophy of [[Immanuel Kant]]. |

The [[American Revolution]] and the [[French Revolution]] used liberal philosophy to justify the violent overthrow of autocratic rule, paving the way for the development of [[History of liberalism|liberalism as a governing ideology]]. The 19th century saw liberal governments established in nations across [[Liberalism in Europe|Europe]], [[Liberalism and conservatism in Latin America|Latin America]], and [[Liberalism in the United States|North America]]. In this period it is associated with the political theory of [[James Madison]], [[Thomas Jefferson]], and with the most progressive wing of the British [[Whig]] party. It was also increasingly associated with [[political economy]] based on the work of [[Adam Smith]] and the rise of the idea of [[Laissez-Faire]] economic policy, and in continental Europe with the ideas of [[Jacobinism]] and the philosophy of [[Immanuel Kant]]. |

||

In the 19th century liberal ideas become associated with [[Free trade]], expansion of voting rights, reduction in the power of the [[Catholic church]] in government, and [[utilitarianism]]. It became defined by its political opposition to [[conservatism]] in the United Kingdom, and by it's alliance with the idea of |

In the 19th century liberal ideas become associated with [[Free trade]], expansion of voting rights, reduction in the power of the [[Catholic church]] in government, and [[utilitarianism]]. It became defined by its political opposition to [[conservatism]] in the United Kingdom, and by it's alliance with the idea of [[progress]] as being the essential means of improving the [[human condition]]. In this era it is associated with the economics of [[John Riccardo]] and [[Thomas Malthus]], the philosophy of [[John Stuart Mill]] and [[Jeremy Bentham]] in the English speaking world, and with liberal revolutions in [[Liberal Revolution of 1820|Portugal]] and [[Spanish Civil War, 1820–1823|Spain]] overthrowing monarchy and mercantilism. In Germany liberalism was associated with unification and nationalism, for example in the plays of [[Robert Blum]]. There was a repeated emphasis in a shift of government from a self-justifying monarchy regardless of the constituent parts, to a state which was based on consent of the governed and national character. |

||

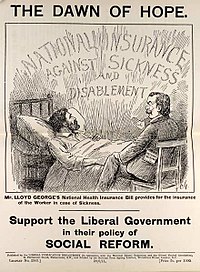

In the late 19th century, many liberal thinkers and politicians began responding to the challenges of late industrialization, population growth, [[Marxism]], and the unification of the global economy by incorporating ideas from [[socialism]] or by formulating liberal responses to [[communitarian]] thinking. This was at first termed "new Liberalism" or "social Liberalism" but often became simply referred to as "liberalism" or "modern liberalism". Notable exponents including [[John Dewey]], British Prime Minister [[Lloyd George]], and economist [[John Maynard Keynes]]. Many adherents to the older form of liberalism rejected, and continue to reject, these developments as [[statist]], and [[socialist]]. |

In the late 19th century, many liberal thinkers and politicians began responding to the challenges of late industrialization, population growth, [[Marxism]], and the unification of the global economy by incorporating ideas from [[socialism]] or by formulating liberal responses to [[communitarian]] thinking. This was at first termed "new Liberalism" or "social Liberalism" but often became simply referred to as "liberalism" or "modern liberalism". Notable exponents including [[John Dewey]], British Prime Minister [[Lloyd George]], and economist [[John Maynard Keynes]]. Many adherents to the older form of liberalism rejected, and continue to reject, these developments as [[statist]], and [[socialist]]. |

||

Revision as of 12:25, 24 March 2010

Liberalism (from the Latin liberalis, "of freedom"[1]) is the belief in the importance of liberty and equality.[2][3] Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but most liberals support such fundamental ideas as constitutions, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights, free trade, secularism, and the market economy. Essential to all forms of liberalism is the belief in self-government as a practical reality, in economic, political, moral, and intellectual affairs. These ideas are often accepted even among political groups that do not openly profess a liberal ideological orientation. Liberalism encompasses several intellectual trends and traditions, but the dominant variants are classical liberalism, which took shape in the late 18th century and early 19th century, and social liberalism, which formed in the early 20th century.

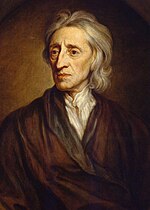

What would later be termed liberalism first became a powerful force in the Age of Reason, rejecting several foundational assumptions that dominated most earlier theories of government, such as hereditary status, established religion, absolute monarchy, and the Divine Right of Kings. Early liberal thinkers such as John Locke, who is often regarded as the founder of liberalism as a distinct philosophical tradition, employed the concept of natural rights and the social contract to argue that the rule of law should replace autocratic government, that rulers were subject to the consent of the governed, and that private individuals had a fundamental right to life, liberty, and property. In the 17th century liberal was often an attack for being without restraint or tradition, but evolved in the late 18th century the world "liberal" came to be applied to being free of prejudice, for example in Edward Gibbon, but to the political ideology only at the beginning of the 19th century.

The American Revolution and the French Revolution used liberal philosophy to justify the violent overthrow of autocratic rule, paving the way for the development of liberalism as a governing ideology. The 19th century saw liberal governments established in nations across Europe, Latin America, and North America. In this period it is associated with the political theory of James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and with the most progressive wing of the British Whig party. It was also increasingly associated with political economy based on the work of Adam Smith and the rise of the idea of Laissez-Faire economic policy, and in continental Europe with the ideas of Jacobinism and the philosophy of Immanuel Kant.

In the 19th century liberal ideas become associated with Free trade, expansion of voting rights, reduction in the power of the Catholic church in government, and utilitarianism. It became defined by its political opposition to conservatism in the United Kingdom, and by it's alliance with the idea of progress as being the essential means of improving the human condition. In this era it is associated with the economics of John Riccardo and Thomas Malthus, the philosophy of John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham in the English speaking world, and with liberal revolutions in Portugal and Spain overthrowing monarchy and mercantilism. In Germany liberalism was associated with unification and nationalism, for example in the plays of Robert Blum. There was a repeated emphasis in a shift of government from a self-justifying monarchy regardless of the constituent parts, to a state which was based on consent of the governed and national character.

In the late 19th century, many liberal thinkers and politicians began responding to the challenges of late industrialization, population growth, Marxism, and the unification of the global economy by incorporating ideas from socialism or by formulating liberal responses to communitarian thinking. This was at first termed "new Liberalism" or "social Liberalism" but often became simply referred to as "liberalism" or "modern liberalism". Notable exponents including John Dewey, British Prime Minister Lloyd George, and economist John Maynard Keynes. Many adherents to the older form of liberalism rejected, and continue to reject, these developments as statist, and socialist.

Liberalism, both in the broader sense and in the narrower sense of new Liberalism, emerged in a transfigured form as the dominant ideology of government in the mid 20th century, when liberal democracies triumphed in two world wars and survived major ideological challenges from fascism and communism. In the United States liberalism is specifically associated with the Democratic Party, and the line of policies begun by Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Today, liberal liberal parties exist on all major continents. They have played a decisive role in the growth of republics, the spread of civil rights and civil liberties, the establishment of the modern welfare state, the institution of religious toleration and religious freedom, and the development of globalization. They have also shown strong support for regional and international organizations, including the European Union and the United Nations, hoping to reduce conflict through diplomacy and multilateral negotiations. To highlight the importance of liberalism in modern life, political scientist Alan Wolfe claimed that "liberalism is the answer for which modernity is the question".[4]

In the present liberalism has a specific meaning in economics, which is often called neo-liberalism in the United States.

Etymology and definition

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Words such as liberal, liberty, and libertarian all trace their history to the Latin liber, which means "free".[5] One of the first recorded instances of the word liberal occurs in 1375, when it was used to describe the liberal arts.[6] The word's early connection with the classical education of a medieval university soon gave way to a proliferation of different denotations and connotations. Liberal could refer to "free in bestowing" as early as 1387, "made without stint" in 1433, "freely permitted" in 1530, and "free from restraint"—often as a pejorative remark—in the 16th and the 17th centuries.[7] In 16th century England, liberal could have positive or negative attributes in referring to someone's generosity or indiscretion.[8] In Much Ado About Nothing, Shakespeare wrote of "a liberal villaine" who "hath...confest his vile encounters".[9] With the rise of the Enlightenment, the word acquired decisively more positive undertones, being defined as "free from narrow prejudice" in 1781 and "free from bigotry" in 1823.[10] In 1815, the first use of the word liberalism appeared in English.[11] By the middle of the 19th century, liberal started being used as a fully politicized term for parties and movements all over the world.

The Oxford Encyclopedic English Dictionary defines the word liberal as "giving freely, generous, not sparing; open-minded, not prejudiced ... for general broadening of the mind".[12] It also defines the word as "regarding many traditional beliefs as dispensable, invalidated by modern thought, or liable to change".[13] Identifying any definitive meaning for the word, however, has proven challenging to scholars and to the general public. The widespread use of the word liberal often inspires people to understand it based on a wide array of factors, including geographic location or political orientation.[14] The American political scientist Louis Hartz echoed this frustration and confusion, writing that "Liberalism is an even vaguer term, clouded as it is by all sorts of modern social reform connotations, and even when one insists on using it in the Lockian sense...there are aspects of our original life in the Puritan colonies and the South which hardly fit its meaning".[15] Hartz emphasized the European origin of the word, conceptualizing a liberal as someone who believes in liberty, equality, and capitalism—in opposition to the association that American conservatives have tried to establish between liberalism and centralized government.[16]

History

The history of liberalism spans the better part of the last four centuries, beginning in the English Civil War and continuing after the end of the Cold War. Liberalism started as a major doctrine and intellectual endeavor in response to the religious wars gripping Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries, although the historical context for the ascendancy of liberalism goes back to the Middle Ages. The first notable incarnation of liberal agitation came with the American Revolution, and liberalism fully exploded as a comprehensive movement against the old order during the French Revolution, which set the pace for the future development of human history. Classical liberals, who broadly emphasized the importance of free markets and civil liberties, dominated liberal history for a century after the French Revolution. The onset of the First World War and the Great Depression, however, accelerated the trends begun in late 19th century Britain towards a new liberalism that emphasized a greater role for the state in ameliorating devastating social conditions. By the beginning of the 21st century, liberal democracies and their fundamental characteristics—support for constitutions, civil rights and individual liberties, pluralistic society, and the welfare state—had prevailed in most regions around the world.

Inception to revolution

European experiences during the Middle Ages were often characterized by fear, uncertainty, and warfare—the latter being especially endemic in medieval life.[17] A symbiotic relationship emerged between the Catholic Church and regional rulers: the Church gave kings and queens authority to rule while the latter spread the message of the Christian faith and did the bidding of Christian social and military forces.[18] The influence of the Church can be seen by the fact that the very term often referred to European society as a whole.[19] In the 14th century, however, disputes over papal successions and the enormous casualty rates of the Black Death incensed people across the continent because they believed that the Church was ineffective.[20][21] The emergence of the Renaissance in the 15th century also helped to weaken unquestioning submission to the Church by reinvigorating interest in science and in the classical world.[22] In the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation developed from sentiments that viewed the Church as an oppressive ruling order too involved in the feudal and baronial structure of European society.[23] The Church launched a Counter Reformation to contain these bubbling sentiments, but the effort unraveled in the Thirty Years War of the 17th century. In England, a massive civil war led to the execution of King Charles I in 1649. Parliament ultimately succeeded—with the Glorious Revolution of 1688—in establishing a limited and constitutional monarchy. The main facets of early liberal ideology emerged from these events, and historians Colton and Palmer characterize the period in the following light:

The unique thing about England was that Parliament, in defeating the king, arrived at a workable form of government. Government remained strong but came under parliamentary control. This determined the character of modern England and launched into the history of Europe and of the world the great movement of liberalism.[24]

The early hero of that movement was the English philosopher John Locke. Locke debated recent political controversies with some of the most famous intellectuals of the day, but his greatest rival was Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes and Locke looked at the political world and disagreed on several substantial issues, although their arguments inspired later social contract theories outlining the relationship between people and their governments.[25] Locke developed a radical political notion, arguing that government acquires consent from the governed. His celebrated Two Treatises (1690), the foundational text of liberal ideology, outlined his major ideas. Once humans moved out of their natural state and formed societies, Locke argued as follows: "Thus that which begins and actually constitutes any political society is nothing but the consent of any number of freemen capable of a majority to unite and incorporate into such a society. And this is that, and that only, which did or could give beginning to any lawful government in the world".[26] The stringent insistence that lawful government did not have a supernatural basis was a sharp break with most previous traditions of governance.[27] The intellectual journey of liberalism continued beyond Locke with the Enlightenment, a period of profound intellectual vitality that questioned old traditions and influenced several monarchies throughout the 18th century.

The ideas circulating in the Enlightenment had a powerful impact in North America and in France. The American colonies had been loyal British subjects for decades, but they declared independence in 1776 after harsh British taxation policies. Military engagements in the American Revolution began in 1775 and were largely complete by 1781. After the war, the colonies held a Constitutional Convention in 1787 to resolve the problems stemming from the Articles of Confederation. The resulting Constitution of the United States settled on a republic. The American Revolution was an important struggle in liberal history, and it was quickly followed by the most important: the French Revolution.

Three years into the French Revolution, German writer Johann von Goethe reportedly told the defeated Prussian soldiers after the Battle of Valmy that "from this place and from this time forth commences a new era in world history, and you can all say that you were present at its birth".[28] Historians widely regard the Revolution as one of the most important events in human history, and the end of the early modern period is attributed to the onset of the Revolution in 1789.[29] The Revolution is often seen as marking the "dawn of the modern era,"[30] and its convulsions are widely associated with "the triumph of liberalism".[31] For liberals, the Revolution was their defining moment, and later liberals approved of the French Revolution almost entirely—"not only its results but the act itself," as two historians noted.[32] The French Revolution began in May 1789 with the convocation of the Estates-General. The first year of the Revolution witnessed, among other major events, the Storming of the Bastille in July and the passage of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in August. The next few years were dominated by tensions between various liberal assemblies and a conservative monarchy intent on thwarting major reforms. A republic was proclaimed in September 1792. External conflict and internal squabbling significantly radicalized the Revolution, culminating in the brutal Reign of Terror. After the fall of Robespierre and the Jacobins, the Directory assumed control of the French state in 1795 and held power until 1799, when it was replaced by the Consulate under Napoleon Bonaparte.

Napoleon ruled as First Consul for about five years, centralizing power and streamlining the bureaucracy along the way. The Napoleonic Wars, pitting the heirs of a revolutionary state against the old monarchies of Europe, started in 1805 and lasted for a decade. Along with their boots and Charleville muskets, French soldiers brought to the rest of the European continent the liquidation of the feudal system, the liberalization of property laws, the end of seigneurial dues, the abolition of guilds, the legalization of divorce, the disintegration of Jewish ghettos, the collapse of the Inquisition, the permanent destruction of the Holy Roman Empire, the elimination of church courts and religious authority, the establishment of the metric system, and equality under the law for all men.[33] Napoleon wrote that "the peoples of Germany, as of France, Italy and Spain, want equality and liberal ideas,"[34] with some historians suggesting that he may have been the first person ever to use the word liberal in a political sense.[35] He also governed through a method that one historian described as "civilian dictatorship," which "drew its legitimacy from direct consultation with the people, in the form of a plebiscite".[36] Napoleon did not always live up the liberal ideals he espoused, however. His most lasting achievement, the Civil Code, served as "an object of emulation all over the globe,"[37] but it also perpetuated further discrimination against women under the banner of the "natural order".[38] The First Empire eventually collapsed in 1815, but this period of chaos and revolution introduced the world to a new movement and ideology that would soon crisscross the globe.

Children of revolution

Liberals in the 19th century wanted to develop a world free from government intervention, or at least free from too much government intervention. They championed the ideal of negative liberty, which constitutes the absence of coercion and the absence of external constraints.[39] They believed governments were cumbersome burdens and they wanted governments to stay out of the lives of individuals.[40] Liberals simultaneously pushed for the expansion of civil rights and for the expansion of free markets and free trade. The latter kind of economic thinking had been formalized by Adam Smith in his monumental Wealth of Nations (1776), which revolutionized the field of economics and established the "invisible hand" of the free market as a self-regulating mechanism that did not depend on external interference.[41] Sheltered by liberalism, the laissez-faire economic world of the 19th century emerged with full tenacity, particularly in the United States and in the United Kingdom.[42]

Politically, liberals saw the 19th century as a gateway to achieving the promises of 1789. In Spain, the Liberales, the first group to use the liberal label in a political context,[43] fought for the implementation of the 1812 Constitution for decades—overthrowing the monarchy in 1820 as part of the Trienio Liberal and defeating the conservative Carlists in the 1830s. In France, the July Revolution of 1830, orchestrated by liberal politicians and journalists, removed the Bourbon monarchy and inspired similar uprisings elsewhere in Europe. Frustration with the pace of political progress, however, sparked even more gigantic revolutions in 1848. Revolutions spread throughout the Austrian Empire, the German states, and the Italian states. Governments fell rapidly. Liberal nationalists demanded written constitutions, representative assemblies, greater suffrage rights, and freedom of the press.[44] A second republic was proclaimed in France. Serfdom was abolished in Prussia, Galicia, Bohemia, and Hungary.[45] Metternich shocked Europe when he resigned and fled to Britain in panic and disguise.[46]

Eventually, however, the success of the revolutionaries petered out. Without French help, the Italians were easily defeated by the Austrians. Austria also managed to contain the bubbling nationalist sentiments in Germany and Hungary, helped along by the failure of the Frankfurt Assembly to unify the German states into a single nation. Under abler leadership, however, the Italians and the Germans wound up realizing their dreams for independence. The Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo di Cavour, was a shrewd liberal who understood that the only effective way for the Italians to gain independence was if the French were on their side.[47] Napoleon III agreed to Cavour's request for assistance and France defeated Austria in the Franco-Austrian War of 1859, setting the stage for Italian independence. German unification transpired under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, who decimated the enemies of Prussia in war after war, finally triumphing against France in 1871 and proclaiming the German Empire in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, ending another saga in the drive for nationalization. The French proclaimed a third republic after their loss in the war, and the rest of French history transpired under republican eyes.

Just a few decades after the French Revolution, liberalism went global. The liberal and conservative struggles in Spain also replicated themselves in Latin American countries like Mexico and Ecuador. From 1857 to 1861, Mexico was gripped in the bloody War of Reform, a massive internal and ideological confrontation between the liberals and the conservatives.[48] The liberal triumph there parallels with the situation in Ecuador. Similar to other nations throughout the region at the time, Ecuador was steeped in turmoil, with the people divided between rival liberal and conservative camps. From these conflicts, García Moreno established a conservative government was eventually overthrown in the Liberal Revolution of 1895. The Radical Liberals who toppled the conservatives were led by Eloy Alfaro, a firebrand who implemented a variety of sociopolitical reforms, including the separation of church and state, the legalization of divorce, and the establishment of public schools.[49]

Although liberals were active throughout the world in the 19th century, it was in Britain that the future character of liberalism would take shape. The liberal sentiments unleashed after the revolutionary era of the previous century ultimately coalesced into the Liberal Party, formed in 1859 from various Radical and Whig elements. The Liberals produced one of the greatest British prime ministers—William Gladstone, who was also known as the Grand Old Man.[50] Under Gladstone, the Liberals reformed education, disestablished the Church of Ireland, and introduced the secret ballot for local and parliamentary elections. Following Gladstone, and after a period of Conservative domination, the Liberals returned with full strength in the general election of 1906, aided by working class voters worried about food prices. After that historic victory, the Liberal Party shifted from its classical liberalism and laid the groundwork for the future British welfare state, establishing various forms of health insurance, unemployment insurance, and pensions for elderly workers.[51] This new kind of liberalism would sweep over much of the world in the 20th century.

Conflict and renewal

The 20th century started perilously for liberalism. The First World War proved a major challenge for liberal democracies, although they ultimately defeated the dictatorial states of the Central Powers. The war precipitated the collapse of older forms of government, including empires and dynastic states. The number of republics in Europe reached 13 by the end of the war, as compared with only three at the start of the war in 1914.[52] This phenomenon became readily apparent in Russia. Before the war, the Russian monarchy was reeling from losses to Japan and political struggles with the Kadets, a powerful liberal bloc in the Duma. Facing huge shortages in basic necessities along with widespread riots in early 1917, Czar Nicholas II abdicated in March, ending three centuries of Romanov rule and allowing liberals to declare a republic. Under the uncertain leadership of Alexander Kerensky, however, the Provisional Government mismanaged Russia's continuing involvement in the war, prompting angry reactions from the Petrograd workers, who drifted further and further to the left. The Bolsheviks, a communist group led by Vladimir Lenin, seized the political opportunity from this confusion and launched a second revolution in Russia during the same year. The communist victory presented a major challenge for liberalism because it precipitated a rise in totalitarian regimes, but the economic problems that rocked the Western world in the 1930s proved even more devastating.

The Great Depression fundamentally changed the liberal world. There was an inkling of a new liberalism during the First World War, but modern liberalism fully hatched in the 1930s as a response to the Depression, which inspired John Maynard Keynes to revolutionize the field of economics. Classical liberals, such as economist Ludwig von Mises, posited that completely free markets were the optimal economic units capable of effectively allocating resources—that over time, in other words, they would produce full employment and economic security.[53] Keynes spearheaded a broad assault on classical economics and its followers, arguing that totally free markets were not ideal, and that hard economic times required intervention and investment from the state. Where the market failed to properly allocate resources, for example, the government was required to stimulate the economy until private funds could start flowing again—a "prime the pump" kind of strategy designed to boost industrial production.[54]

The social liberal program launched by President Roosevelt in the United States, the New Deal, proved very popular with the American public. In 1933, when FDR came into office, the unemployment rate stood at roughly 25 percent.[55] The size of the economy, measured by the gross national product, had fallen to half the value it had in early 1929.[56] The electoral victories of FDR and the Democrats precipitated a deluge of deficit spending and public works programs. In 1940, the level of unemployment had fallen by 10 points to around 15 percent.[57] Additional state spending and the gigantic public works program sparked by the Second World War eventually pulled the United States out of the Great Depression. From 1940 to 1941, government spending increased by 59 percent, the gross domestic product skyrocketed 17 percent, and unemployment fell below 10 percent for the first time since 1929.[58] By 1945, after vast government spending, public debt stood at a staggering 120 percent of GNP, but unemployment had been effectively eliminated.[59] Most nations that emerged from the Great Depression did so with deficit spending and strong intervention from the state.

The economic woes of the period prompted widespread unrest in the European political world, leading to the rise of fascism as an ideology and a movement that heavily criticized liberalism.[60] Broadly speaking, fascist ideology emphasized elite rule and absolute leadership, a rejection of equality, the imposition of patriarchal society, a stern commitment to war as an instrument of natural behavior, and the elimination of supposedly inferior or subhuman groups from the structure of the nation.[61] The fascist and nationalist grievances of the 1930s eventually culminated in the Second World War, the deadliest conflict in human history. The Allies prevailed in the war by 1945, and their victory set the stage for the Cold War between communist states and liberal democracies. The Cold War featured extensive ideological competition and several proxy wars. While communist states and liberal democracies competed against one another, an economic crisis in the 1970s inspired a temporary move away from Keynesian economics across many Western governments. This classical liberal renewal, known as neoliberalism, lasted through the 1980s and the 1990s, bringing about economic privatization of previously state-owned industries. However, recent economic troubles have prompted a resurgence in Keynesian economic thought. Meanwhile, nearing the end of the 20th century, communist states in Eastern Europe collapsed precipitously, leaving liberal democracies as the only major forms of government. At the beginning of the Second World War, the number of democracies around the world was about the same as it had been forty years before.[62] After 1945, liberal democracies spread very quickly. Even as late as 1974, roughly 75 percent of all nations were considered dictatorial, but now more than half of all countries are democracies.[63] This last achievement spoke volumes about the influence of liberalism to the American intellectual Francis Fukuyama, who speculated on the "end of history" by claiming:

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such; that is, the end point of...ideological evolution and the universalization of...liberal democracy as the final form of human government.[64]

Philosophy

Liberalism—both as a political current and an intellectual tradition—is mostly a modern phenomenon that started in the 17th century, although some liberal philosophical ideas had precursors in classical antiquity.[65] The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius praised "the idea of a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed".[66] Scholars have also recognized a number of principles familiar to contemporary liberals in the works of several Sophists and in the Funeral Oration by Pericles.[67] Liberal philosophy symbolizes an extensive intellectual tradition that has examined and popularized some of the most important and controversial principles of the modern world. Its immense scholarly and academic output has been characterized as containing "richness and diversity," but that diversity often has meant that liberalism comes in different formulations and presents a challenge to anyone looking for a clear definition.[68]

Major themes

Though all liberal doctrines possess a common heritage, scholars frequently assume that those doctrines contain "separate and often contradictory streams of thought".[69] The objectives of liberal theorists and philosophers have differed across various times, cultures, and continents. The diversity of liberalism can be gleaned from the numerous adjectives that liberal thinkers and movements have attached to the very term liberalism, including classical, egalitarian, economic, social, welfare-state, ethical, humanist, deontological, perfectionist, democratic, and institutional, to name a few.[70] Despite these variations, liberal thought does exhibit a few definite and fundamental conceptions. At its very root, liberalism is a philosophy about the meaning of humanity and society. Political philosopher John Gray identified the common strands in liberal thought as being individualist, egalitarian, meliorist, and universalist. The individualist element avers the ethical primacy of the human being against the pressures of social collectivism, the egalitarian element assigns the same moral worth and status to all individuals, the meliorist element asserts that successive generations can improve their sociopolitical arrangements, and the universalist element affirms the moral unity of the human species and marginalizes local cultural differences.[71] The meliorist element has been the subject of much controversy, defended by thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, who believed in human progress, while suffering from attacks by thinkers such as Rousseau, who believed that human attempts to improve themselves through social cooperation would fail.[72] Describing the liberal temperament, Gray claimed that it "has been inspired by skepticism and by a fideistic certainty of divine revelation ... it has exalted the power of reason even as, in other contexts, it has sought to humble reason's claims". The liberal philosophical tradition has searched for validation and justification through several intellectual projects. The moral and political suppositions of liberalism have been based on traditions such as natural rights and utilitarian theory, although sometimes liberals even requested support from scientific and religious circles.[73] Through all these strands and traditions, scholars have identified the following major common facets of liberal thought: believing in equality and individual liberty, supporting private property and individual rights, supporting the idea of limited constitutional government, and recognizing the importance of related values such as pluralism, toleration, autonomy, and consent.[74]

Dominant ideas and traditions

Early liberals, including John Locke and Baruch Spinoza, attempted to determine the purpose of government in a liberal society. To these liberals, securing the most essential amenities of life—liberty and private property among them—required the formation of a "sovereign" authority with universal jurisdiction.[75] In a natural state of affairs, liberals argued, humans were driven by the instincts of survival and self-preservation, and the only way to escape from such a dangerous existence was to form a common and supreme power capable of arbitrating between competing human desires.[76] This power could be formed in the framework of a civil society that allows individuals to make a voluntary social contract with the sovereign authority, transferring their natural rights to that authority in return for the protection of life, liberty, and property.[77] These early liberals often disagreed in their opinion of the most appropriate form of government, but they all shared the belief that liberty was natural and that its restriction needed strong justification.[78] Liberals generally believed in limited government, although several liberal philosophers decried government outright, with Thomas Paine writing that "government even in its best state is a necessary evil".[79] As part of the project to limit the powers of government, various liberal theorists—such as James Madison and the Baron de Montesquieu—conceived the notion of separation of powers, a system designed to equally distribute governmental authority among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.[80] Finally, governments had to realize, liberals maintained, that poor and improper governance gave the people authority to overthrow the ruling order through any and all possible means—even through outright violence and revolution, if needed.[81] Contemporary liberals, heavily influenced by social liberalism, have continued to support limited constitutional government while also advocating for state services and provisions to ensure equal rights. Modern liberals claim that formal or official guarantees of individual rights are irrelevant when individuals lack the material means to benefit from those rights, urging a greater role for government in the administration of economic affairs.[82]

Beyond identifying a clear role for government in modern society, liberals also have obsessed over the meaning and nature of the most important principle in liberal philosophy: liberty. From the 17th century until the 19th century, liberals—from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill—conceptualized liberty as the absence of interference from government and from other individuals, claiming that all people should have the freedom to develop their own unique abilities and capacities without being sabotaged by others.[83] Mill's On Liberty (1859), one of the classic texts in liberal philosophy, proclaimed that "the only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way".[84] Support for laissez-faire capitalism is often associated with this principle, with Friedrich Hayek arguing in the The Road to Serfdom (1944) that reliance on free markets would preclude totalitarian control by the state.[85] Beginning in the late 19th century, however, a new conception of liberty entered the liberal intellectual arena. This new kind of liberty became known as positive liberty to distinguish it from the prior negative version, and it was first developed by British philosopher Thomas Hill Green. Green rejected the idea that humans were driven solely by self-interest, emphasizing instead the complex circumstances that are involved in the evolution of our moral character.[86] In a very profound step for the future of modern liberalism, he also tasked social and political institutions with the enhancement of individual freedom and identity.[87] Foreshadowing the new liberty as the freedom to act rather than to avoid suffering from the acts of others, Green wrote the following:

If it were ever reasonable to wish that the usage of words had been other than it has been...one might be inclined to wish that the term 'freedom' had been confined to the...power to do what one wills.[88]

Rather than previous liberal conceptions viewing society as populated by selfish individuals, Green viewed society as an organic whole in which all individuals have a duty to promote the common good.[89] His ideas spread rapidly and were developed by other thinkers such as L. T. Hobhouse and John Hobson. In a few short years, this New Liberalism had become the essential social and political program of the Liberal Party in Britain,[90] and it would encircle much of the world in the 20th century. In addition to examining negative and positive liberty, liberals have tried to understand the proper relationship between liberty and democracy. As they struggled to expand suffrage rights, liberals increasingly understood that people left out of the democratic decision-making process were liable to the tyranny of the majority, a concept explained in Mill's On Liberty and in Democracy in America (1835) by Alexis de Tocqueville.[91] As a response, liberals began demanding proper safeguards to thwart majorities in their attempts at suppressing the rights of minorities.[92]

Besides liberty, liberals have developed several other principles important to the construction of their philosophical structure, such as equality, pluralism, and toleration. Highlighting the confusion over the first principle, Voltaire commented that "equality is at once the most natural and at times the most chimeral of things".[93] All forms of liberalism assume, in some basic sense, that individuals are equal.[94] In maintaining that people are naturally equal, liberals assume that they all possess the same right to liberty.[95] In other words, no one is inherently entitled to enjoy the benefits of liberal society more than anyone else, and all people are equal subjects before the law.[96] Beyond this basic conception, liberal theorists diverge on their understanding of equality. American philosopher John Rawls emphasized the need to ensure not only equality under the law, but also the equal distribution of material resources that individuals required to develop their aspirations in life.[97] Libertarian thinker Robert Nozick disagreed with Rawls, championing the former version of Lockean equality instead.[98] To contribute to the development of liberty, liberals also have promoted concepts like pluralism and toleration. By pluralism, liberals refer to the proliferation of opinions and beliefs that characterize a stable social order.[99] Unlike many of their competitors and predecessors, liberals do not seek conformity and homogeneity in the way that people think; in fact, their efforts have been geared towards establishing a governing framework that harmonizes and minimizes conflicting views, but still allows those views to exist and flourish.[100] For liberal philosophy, pluralism leads easily to toleration. Since individuals will hold diverging viewpoints, liberals argue, they ought to uphold and respect the right of one another to disagree.[101] From the liberal perspective, toleration was initially connected to religious toleration, with Spinoza condemning "the stupidity of religious persecution and ideological wars".[102] Toleration also played a central role in the ideas of Kant and John Stuart Mill. Both thinkers believed that society will contain different conceptions of a good ethical life and that people should be allowed to make their own choices without interference from the state or other individuals.[103]

Relation to other ideologies

As one of the first modern ideologies, liberalism has had a profound impact on the ones that followed it. In particular, some scholars suggest that liberalism gave rise to feminism, although others maintain that liberal democracy is inadequate for the realization of feminist objectives.[104] Liberal feminism, the dominant tradition in feminist history, hopes to eradicate all barriers to gender equality—claiming that the continued existence of such barriers eviscerates the individual rights and freedoms ostensibly guaranteed by a liberal social order.[105] British philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft is widely regarded as the pioneer of liberal feminism, with A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) expanding the boundaries of liberalism to include women in the political structure of liberal society.[106] Less friendly to the goals of liberalism has been conservatism. Like liberalism, conservatism is complex and amorphous, laying claims to several intellectual traditions over the last three centuries.[107] Edmund Burke, considered by some to be the first major proponent of modern conservative thought, offered a blistering critique of the French Revolution by assailing the liberal pretensions to the power of rationality and to the natural equality of all humans.[108] However, a few variations of conservatism, like conservative liberalism, expound some of the same ideas and principles championed by classical liberalism, including "small government and thriving capitalism".[109] Even more uncertain is the relationship between liberalism and socialism. Socialism began as a concrete ideology in the 19th century with the writings of Karl Marx, and it too—as with liberalism and conservatism—fractured into several major movements in the decades after its founding.[110] The most prominent eventually became social democracy, which can be broadly defined as a project that aims to correct what it regards as the intrinsic defects of capitalism by reducing the inequalities that exist within an economic system.[111] Several commentators have noted strong similarities between social liberalism and social democracy, with one political scientist even calling American liberalism "bootleg social democracy".[112] Another movement associated with modern democracy, Christian democracy, hopes to spread Catholic social ideas and has gained a large following in some European nations.[113] The early roots of Christian democracy developed as a reaction against the industrialization and urbanization associated with laissez-faire liberalism in the 19th century.[114] Despite these complex relationships, some scholars have argued that liberalism actually "rejects ideological thinking" altogether, largely because such thinking could lead to unrealistic expectations for human society.[115]

Worldwide

Liberals are committed to build and safeguard free, fair and open societies, in which they seek to balance the fundamental values of liberty, equality and community, and in which no one is enslaved by poverty, ignorance or conformity ... Liberalism aims to disperse power, to foster diversity and to nurture creativity.

Liberalism is frequently cited as the dominant ideology of modern times.[117][118] Politically, liberals have organized extensively throughout the world. Liberal parties, think tanks, and other institutions are common in many nations, although they advocate for different causes based on their ideological orientation. Liberal parties can be center-left, centrist, or center-right depending on their location. They can further be divided based on their adherence to social liberalism or classical liberalism, although all liberal parties and individuals share basic similarities, including the support for civil rights and democratic institutions. On a global level, liberals are united in the Liberal International, which contains over 100 influential liberal parties and organizations from across the ideological spectrum. Some parties in the LI are among the most famous in the world, such as the Liberal Party of Canada, while others are among the smallest, such as the Liberal Party of Gibraltar. Regionally, liberals are organized through various institutions depending on the prevailing geopolitical context. In the European Parliament, for example, the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe is the predominant group that represents the interest of European liberals.

Europe

In Europe, liberalism has a long tradition dating back to 17th century. Scholars often split those traditions into English and French versions, with the former version of liberalism emphasizing the expansion of democratic values and constitutional reform and the latter rejecting authoritarian political and economic structures, as well as being involved with nation-building.[119] The continental French version was deeply divided between moderates and progressives, with the moderates tending to elitism and the progressives supporting the universalization of fundamental institutions, such as universal suffrage, universal education, and the expansion of property rights.[120] Over time, the moderates displaced the progressives as the main guardians of continental European liberalism. Moderates were identified with liberalism or liberal conservatism whereas progressives could fall under a number of left-wing camps, from liberalism and radicalism to republicanism and social democracy.[121] A prominent example of these divisions is the German Free Democratic Party, which was historically divided between national liberal and social liberal factions.[122]

Before the First World War, liberal parties dominated the European political scene, but they were gradually displaced by socialists and social democrats in the early 20th century. The fortunes of liberal parties since World War II have been mixed, with some gaining strength while others suffered from continuous declines.[123] The fall of the Soviet Union and the breakup of Yugoslavia at the end of the 20th century, however, allowed the formation of many liberal parties throughout Eastern Europe. These parties developed varying ideological characters. Some, such as the Slovenian Liberal Democrats or the Lithuanian Social Liberals, have been characterized as center-left.[124][125] Others, such as the Romanian National Liberal Party, have been classified as center-right.[126] Meanwhile, some liberal parties in Western Europe have undergone renewal and transformation, coming back to the political limelight after historic disappointments. Perhaps the most famous instance is the Liberal Democrats in Britain. The Liberal Democrats are the heirs of the once-mighty Liberal Party, which suffered a huge erosion of support to the Labour Party in the early 20th century. After nearly vanishing from the British political scene altogether, the Liberals eventually united with the Social Democratic Party, a Labour splinter group, in 1988—forming the current Liberal Democrats along the way. The Liberal Democrats have earned significant popular support in the general election of 2005 and in local council elections, marking the first time in decades that a British party with a liberal ideology has achieved such electoral success. Both in Britain and elsewhere in Western Europe, liberal parties have often cooperated with socialist and social democratic parties, as evidenced by the Purple Coalition in the Netherlands during the late 1990s and into the 21st century. The Purple Coalition, one of the most consequential in Dutch history, brought together the progressive left-liberal D66,[127] the market liberal and center-right VVD,[128] and the socialist Labour Party—an unusual combination that ultimately legalized same-sex marriage, euthanasia, and prostitution while also instituting a non-enforcement policy on marijuana.

Americas

In North America, unlike in Europe, the word liberalism almost exclusively refers to social liberalism in contemporary politics. The dominant Canadian and American parties, the Liberal Party and the Democratic Party, are frequently identified as being modern liberal or center-left organizations in the academic literature.[129][130][131] In Canada, the long-dominant Liberal Party, affectionately known as the Grits, ruled the country for nearly 70 years during the 20th century. The party produced some of the most famous prime ministers in Canadian history, including Pierre Trudeau and Jean Chrétien, and has been primarily responsible for the development of the Canadian welfare state. The enormous success of the Liberals—virtually unmatched in any other liberal democracy—has prompted many political commentators over time to identify them as the nation's natural governing party.[132][133]

In the United States, modern liberalism traces its history to the popular presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who initiated the New Deal in response to the Great Depression and won an unprecedented four elections. The New Deal coalition established by FDR left a decisive legacy and impacted many future American presidents, including John F. Kennedy, a self-described liberal who defined a liberal as "someone who looks ahead and not behind, someone who welcomes new ideas without rigid reactions...someone who cares about the welfare of the people".[134] In the late 20th century, a conservative backlash against the kind of liberalism championed by FDR and JFK developed in the Republican Party.[135] This brand of conservatism primarily reacted against the civil unrest and the cultural changes that transpired during the 1960s.[136] It launched into power presidents such as Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush. Economic woes in the early 21st century, however, led to a resurgence of social liberalism with the election of Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential election.[137]

In Latin America, liberal agitation dates back to the 19th century, when liberal groups frequently fought against and violently overthrew conservative regimes in several countries across the region. Liberal revolutions in countries such as Mexico and Ecuador ushered in the modern world for much of Latin America. Latin American liberals generally emphasized free trade, private property, and anti-clericalism.[138] Today, market liberals in Latin America are organized in the Red Liberal de América Latina, a network that brings together dozens of liberal parties and organizations. RELIAL features parties as geographically diverse as the Mexican Nueva Alianza and the Cuban Liberal Union, which aims to secure power in Cuba. Some major liberal parties in the region continue, however, to align themselves with social liberal ideas and policies—a notable case being the Colombian Liberal Party, which is a member of the Socialist International. Another famous example is the Paraguayan Authentic Radical Liberal Party, one of the most powerful parties in the country, which has also been classified as center-left.[139]

Asia and Oceania

In Asia, liberalism is a much younger political current than in Europe or the Americas. Continentally, liberals are organized through the Council of Asian Liberals and Democrats, which includes powerful parties such the Liberal Party in the Philippines, the Democratic Progressive Party in Taiwan, and the Democrat Party in Thailand. Two notable examples of liberal influence can be found in India and Australia, although several Asian nations have rejected important liberal principles.

In Australia, liberalism is primarily championed by the center-right Liberal Party.[140] The Liberals in Australia support free markets as well as social conservatism.[141][142] In India, the most populous democracy in the world, the Indian National Congress has long dominated political affairs. The INC was founded in the late 19th century by liberal nationalists demanding the creation of a more liberal and autonomous India.[143] Liberalism continued to be the main ideological current of the group through the early years of the 20th century, but socialism gradually overshadowed the thinking of the party in the next few decades. A famous struggle led by the INC eventually earned India's independence from Britain. In recent times, the party has adopted more of a liberal streak, championing open markets while simultaneously seeking social justice. In its 2009 Manifesto, the INC praised a "secular and liberal" Indian nationalism against the nativist, communal, and conservative ideological tendencies it claims are espoused by the right.[144] In general, the major theme of Asian liberalism in the past few decades has been the rise of democratization as a method facilitate the rapid economic modernization of the continent.[145] Several Asian nations, however, notably China, are challenging Western liberalism with a combination of authoritarian government and capitalism,[146] while in others, notably Myanmar, liberal democracy has been replaced by military dictatorship.[147]

Africa

Liberalism in Africa is comparatively weak. In recent times, however, liberal parties and institutions have made a major push for political power. On a continental level, liberals are organized in the Africa Liberal Network, which contains influential parties such as the Popular Movement in Morocco, the Democratic Party in Senegal, and the Rally of the Republicans in Côte d'Ivoire. Among African nations, South Africa stands out for having a notable liberal tradition that other countries on the continent lack. In the middle of the 20th century, the Liberal Party and the Progressive Party were formed to oppose the apartheid policies of the government. The Liberals formed a multiracial party that originally drew considerable support from urban Africans and college-educated whites.[148] It also gained supporters from the "westernized sectors of the peasantry", and its public meetings were heavily attended by black Africans.[149] The party had 7,000 members at its height, although its appeal to the white population as a whole was too small to make any meaningful political changes.[150] The Liberals were disbanded in 1968 after the government passed a law that prohibited parties from having multiracial membership. Today, liberalism in South Africa is represented by the Democratic Alliance, the official opposition party to the ruling African National Congress. The Democratic Alliance is the second largest party in the National Assembly and currently leads the provincial government of Western Cape.

Impact and influence

The fundamental elements of contemporary society have liberal roots. The early waves of liberalism expanded constitutional and parliamentary government, popularized economic individualism, and established a clear distinction between religious and political authority.[151] One of the greatest liberal triumphs involved replacing the capricious nature of royalist and absolutist rule with a decision-making process encoded in written law.[152] Liberals sought and established a constitutional order that prized important individual freedoms, such as the freedom of speech and of association, an independent judiciary and public trial by jury, and the abolition of aristocratic privileges.[153] These sweeping changes in political authority marked the modern transition from absolutism to constitutional rule.[154] The expansion and promotion of free markets was another major liberal achievement. Before they could establish markets, however, liberals had to destroy the old economic structures of the world. In that vein, liberals ended mercantilist policies, royal monopolies, and various other restraints on economic activities.[155] They also sought to abolish internal barriers to trade—eliminating guilds, local tariffs, and prohibitions on the sale of land along the way.[156] Beyond free markets and constitutional government, early liberals also laid the groundwork for the separation of church and state. As heirs of the Enlightenment, liberals believed that any given social and political order emanated from human interactions, not from divine will.[157] Many liberals were openly hostile to religious belief itself, but most concentrated their opposition to the union of religious and political authority—arguing that faith could prosper on its own, without official sponsorship or administration from the state.[158]

Later waves of liberal thought and struggle were strongly influenced by the need to expand civil rights. In the 1960s and 1970s, the cause of Second Wave feminism in the United States was advanced in large part by liberal feminist organizations such as National Organization for Women.[159] In addition to supporting gender equality, liberals also have advocated for racial equality in their drive to promote civil rights, and a global civil rights movement in the 20th century achieved several objectives towards both goals. Among the various regional and national movements, the civil rights movement in the United States during the 1960s strongly highlighted the liberal crusade for equal rights. Describing the political efforts of the period, some historians have asserted that "the voting rights campaign marked...the convergence of two political forces at their zenith: the black campaign for equality and the movement for liberal reform," further remarking about how "the struggle to assure blacks the ballot coincided with the liberal call for expanded federal action to protect the rights of all citizens".[160] The Great Society project launched by President Lyndon B. Johnson oversaw the creation of Medicare and Medicaid, the establishment of Head Start and the Job Corps as part of the War on Poverty, and the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964—an altogether rapid series of events that some historians have dubbed the Liberal Hour.[161]

Another major accomplishment of liberal agitation includes the rise of liberal internationalism, which has been credited with the establishment of global organizations such as the League of Nations and, after the Second World War, the United Nations.[162] The idea of exporting liberalism worldwide and constructing a harmonious and liberal internationalist order has dominated the thinking of liberals since the 18th century.[163] "Wherever liberalism has flourished domestically, it has been accompanied by visions of liberal internationalism," one historian wrote.[164] But resistance to liberal internationalism was deep and bitter, with critics arguing that growing global interdependency would result in the loss of national sovereignty and that democracies represented a corrupt order incapable of either domestic or global governance.[165] Other scholars have praised the influence of liberal internationalism, claiming that the rise of globalization "constitutes a triumph of the liberal vision that first appeared in the eighteenth century" while also writing that liberalism is "the only comprehensive and hopeful vision of world affairs".[166] The gains of liberalism have been significant. In 1975, roughly 40 countries around the world were characterized as liberal democracies, but that number had increased to more than 80 as of 2008.[167] Most of the world's richest and most powerful nations are liberal democracies with extensive social welfare programs.[168]

Notes

- ^ Latin Dictionary and Grammar Aid University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ Young, p. 39. Like liberty, equality has been a fundamental feature of the liberal outlook.

- ^ Song, p. 45. Grounded on these foundations are the two central values of liberalism: equality and liberty.

- ^ Wolfe, p. 254.

- ^ Gross, p. 5.

- ^ Gross, p. 5.

- ^ Gross, p. 5.

- ^ Gross, p. 5.

- ^ Gross, p. 5.

- ^ Gross, p. 5.

- ^ Kirchner, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Dorrien, p. xix.

- ^ Dorrien, p. xix.

- ^ Kirchner, p. 2.

- ^ Hartz, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Hartz, p. ix.

- ^ Tanner, p. xx.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, pp. 22–4.

- ^ Roberts, p. 473. By 'the Church' as an earthly institution, Christians mean the whole body of the faithful, lay and cleric alike. In this sense the Church came to be the same thing as European society during the Middle Ages.

- ^ Tanner, p. 1.

- ^ Peters, p. 47.

- ^ Johnson, p. 28. Dante was not just a medieval man, he was a Renaissance man too. He was highly critical of the church, like many so scholars who followed him.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 75. They might wish to manage their own religious affairs as they did their other business, believing that the church hierarchy was too much embedded in a feudal, baronial, and monarchical system with which they had little in common.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 171.

- ^ Copleston, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Locke, p. 170.

- ^ Forster, p. 219.

- ^ Coker, p. 3.

- ^ Frey, Foreword.

- ^ Frey, Preface.

- ^ Ros, p. 11.

- ^ Manent and Seigel, p. 80.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, pp. 428–9.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 428.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 428.

- ^ Lyons, p. 111.

- ^ Lyons, p. 94.

- ^ Lyons, pp. 98–102.

- ^ Heywood, p. 47.

- ^ Heywood, pp. 47–8.

- ^ Heywood, p. 52.

- ^ Heywood, p. 53.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 479.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 510.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 510.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 509.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, pp. 546–7.

- ^ Stacy, p. 698.

- ^ Handelsman, p. 10.

- ^ Cook, p. 31.

- ^ Heywood, p. 61.

- ^ Mazower, p. 3.

- ^ Shaw, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 808.

- ^ Auerbach and Kotlikoff, p. 299.

- ^ Dobson, p. 264.

- ^ Steindl, p. 111.

- ^ Knoop, p. 151.

- ^ Rivlin, p. 53.

- ^ Perry et al., p. 759. Hitler writes that the chief principle of fascism is the following: to abolish the liberal concept of the individual and the Marxist concept of humanity, and to substitute for them the Volk community, rooted in the soil and united by the bond of its common blood.

- ^ Heywood, pp. 218–26.

- ^ Colomer, p. 62.

- ^ Diamond, cover flap.

- ^ Browning et al., p. 61.

- ^ Young, pp. 25–6.

- ^ Antoninus, p. 3.

- ^ Young, pp. 25–6.

- ^ Young, p. 24.

- ^ Young, p. 24.

- ^ Young, p. 25.

- ^ Gray, p. xii.

- ^ Wolfe, pp. 33-6.

- ^ Gray, p. xii.

- ^ Young, p. 45.

- ^ Young, pp. 30–1.

- ^ Young, p. 30.

- ^ Young, p. 30.

- ^ Young, p. 30.

- ^ Young, p. 31.

- ^ Young, p. 31.

- ^ Young, p. 32.

- ^ Young, pp. 32–3.

- ^ Young, p. 33.

- ^ Young, p. 33.

- ^ Wolfe, p. 74.

- ^ Adams, pp. 54–5.

- ^ Adams, pp. 54–5.

- ^ Wempe, p. 123.

- ^ Adams, p. 55.

- ^ Adams, p. 58.

- ^ Young, p. 36.

- ^ Young, p. 36.

- ^ Wolfe, p. 63.

- ^ Young, p. 39.

- ^ Young, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Young, p. 40.

- ^ Young, p. 40.

- ^ Young, p. 40.

- ^ Young, pp. 42–3.

- ^ Young, p. 43.

- ^ Young, p. 44.

- ^ Young, p. 44.

- ^ Young, p. 44.

- ^ Jensen, p. 1.

- ^ Jensen, p. 2.

- ^ Falco, pp. 47–8.

- ^ Grigsby, p. 108.

- ^ Grigsby, p. 108.

- ^ Grigsby, p. 108.

- ^ Grigsby, pp. 119–22.

- ^ Lightfoot, p. 17.

- ^ Susser, p. 110.

- ^ Riff, pp. 34–6.

- ^ Riff, p. 34.

- ^ Wolfe, p. 116.

- ^ The International Liberal International. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ Wolfe, p. 23.

- ^ Adams, p. 11.

- ^ Kirchner, p. 3.

- ^ Kirchner, p. 3.

- ^ Kirchner, p. 3.

- ^ Kirchner, p. 4.

- ^ Kirchner, p. 10.

- ^ Karatnycky et al., p. 247.

- ^ Hafner and Ramet, p. 104.

- ^ Various authors, p. 1615.

- ^ Schie and Voermann, p. 121.

- ^ Gallagher et al., p. 226.

- ^ Puddington, p. 142. After a dozen years of center-left Liberal Party rule, the Conservative Party emerged from the 2006 parliamentary elections with a plurality and established a fragile minority government.

- ^ Grigsby, p. 106-7. [Talking about the Democratic Party] Its liberalism is for the most part the later version of liberalism—modern liberalism.

- ^ Arnold, p. 3. Modern liberalism occupies the left-of-center in the traditional political spectrum and is represented by the Democratic Party in the United States.

- ^ Penniman, p. 72.

- ^ Chodos et al., p. 9.

- ^ Alterman, p. 32.

- ^ Flamm and Steigerwald, pp. 156–8.

- ^ Flamm and Steigerwald, pp. 156–8.

- ^ Wolfe, p. xiv.

- ^ Dore and Molyneux, p. 9.

- ^ Ameringer, p. 489.

- ^ Monsma and Soper, p. 95.

- ^ Monsma and Soper, p. 95.

- ^ Karatnycky, p. 59.

- ^ Hodge, p. 346.

- ^ 2009 Manifesto Indian National Congress. Retrieved 2010-02-21.

- ^ Routledge et al., p. 111.

- ^ Gifford, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Steinberg, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Van den Berghe, p. 56.

- ^ Van den Berghe, p. 57.

- ^ Van den Berghe, p. 56.

- ^ Gould, p. 3.

- ^ Gould, p. 3.

- ^ Gould, p. 3.

- ^ Gould, p. 3.

- ^ Gould, p. 3.

- ^ Gould, p. 3.

- ^ Gould, p. 4.

- ^ Gould, p. 4.

- ^ Worell, p. 470.

- ^ Mackenzie and Weisbrot, p. 178.

- ^ Mackenzie and Weisbrot, p. 5.

- ^ Sinclair, p. 145.

- ^ Schell, p. 266.

- ^ Schell, p. 266.

- ^ Schell, pp. 273–80.

- ^ Venturelli, p. 247.

- ^ Farr, p. 81.

- ^ Pierson, p. 110.

References

- Adams, Ian. Ideology and politics in Britain today. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-719-05056-1

- Alterman, Eric. Why We're Liberals. New York: Viking Adult, 2008. ISBN 0-670-01860-0

- Ameringer, Charles. Political parties of the Americas, 1980s to 1990s. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1992. ISBN 0-313-27418-5

- Antoninus, Marcus Aurelius. The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-199-54059-4

- Arnold, N. Scott. Imposing values: an essay on liberalism and regulation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 0-495-50112-3

- Auerbach, Alan and Kotlikoff, Laurence. Macroeconomics Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998. ISBN 0-262-01170-0

- Bernstein, Richard. Thomas Jefferson: The Revolution of Ideas. New York: Oxford University Press US, 2004. ISBN 0-195-14368-X

- Browning, Gary et al. Understanding Contemporary Society: Theories of the Present. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2000. ISBN 0-761-95926-2

- Chodos, Robert et al. The unmaking of Canada: the hidden theme in Canadian history since 1945. Halifax: James Lorimer & Company, 1991. ISBN 1-550-28337-5

- Coker, Christopher. Twilight of the West. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998. ISBN 0-813-33368-7

- Colomer, Josep Maria. Great Empires, Small Nations. New York: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 0-415-43775-X

- Colton, Joel and Palmer, R.R. A History of the Modern World. New York: McGraw Hill, Inc., 1995. ISBN 0-07-040826-2

- Cook, Richard. The Grand Old Man. Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-419-16449-X

- Copleston, Frederick. A History of Philosophy: Volume V. New York: Doubleday, 1959. ISBN 0-385-47042-8

- Delaney, Tim. The march of unreason: science, democracy, and the new fundamentalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-192-80485-5

- Diamond, Larry. The Spirit of Democracy. New York: Macmillan, 2008. ISBN 0-805-07869-X

- Dobson, John. Bulls, Bears, Boom, and Bust. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 1-851-09553-5

- Dorrien, Gary. The making of American liberal theology. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0-664-22354-0

- Farr, Thomas. World of Faith and Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press US, 2008. ISBN 0-195-17995-1

- Falco, Maria. Feminist interpretations of Mary Wollstonecraft. State College: Penn State Press, 1996. ISBN 0-271-01493-8

- Flamm, Michael and Steigerwald, David. Debating the 1960s: liberal, conservative, and radical perspectives. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. ISBN 0-742-52212-1

- Forster, Greg. John Locke's politics of moral consensus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-84218-2

- Frey, Linda and Frey, Marsha. The French Revolution. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0-313-32193-0

- Gallagher, Michael et al. Representative government in modern Europe. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-072-32267-5

- Gifford, Rob. China Road: A Journey into the Future of a Rising Power. Random House, 2008. ISBN 0-812-97524-3

- Godwin, Kenneth et al. School choice tradeoffs: liberty, equity, and diversity. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002. ISBN 0-292-72842-5

- Gould, Andrew. Origins of liberal dominance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999. ISBN 0-472-11015-2

- Gray, John. Liberalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995. ISBN 0-816-62801-7

- Gregg, Pauline. Free-Born John: A Biography of John Lilburne. Phoenix Press, 2001. ISBN 978-1842122006

- Grigsby, Ellen. Analyzing Politics: An Introduction to Political Science. Florence: Cengage Learning, 2008. ISBN 0-495-50112-3

- Gross, Jonathan. Byron: the erotic liberal. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2001. ISBN 0-742-51162-6

- Hafner, Danica and Ramet, Sabrina. Democratic transition in Slovenia: value transformation, education, and media. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2006. ISBN 1-585-44525-8

- Handelsman, Michael. Culture and Customs of Ecuador. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30244-8

- Hanson, Paul. Contesting the French Revolution. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing, 2009. ISBN 1-405-16083-7

- Hartz, Louis. The liberal tradition in America. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1955. ISBN 0-156-51269-6

- Heywood, Andrew. Political Ideologies: An Introduction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-333-96177-3

- Hodge, Carl. Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800-1944. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. ISBN 0-313-33406-4

- Jensen, Pamela Grande. Finding a new feminism: rethinking the woman question for liberal democracy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1996. ISBN 0-847-68189-0

- Johnson, Paul. The Renaissance: A Short History. New York: Modern Library, 2002. ISBN 0-812-96619-8

- Karatnycky, Adrian. Freedom in the World. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0-765-80760-2

- Karatnycky, Adrian et al. Nations in transit, 2001. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2001. ISBN 0-765-80897-8

- Kerber, Linda. "The Republican Mother". Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1976.

- Kirchner, Emil. Liberal parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-521-32394-0

- Knoop, Todd. Recessions and Depressions Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0-313-38163-1

- Lightfoot, Simon. Europeanizing social democracy?: the rise of the Party of European Socialists. New York: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-34803-X

- Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. reprint, New York: Hafner Publishing Company, Inc., 1947. ISBN 0-028-48500-9

- Locke, John. A Letter Concerning Toleration: Humbly Submitted. CreateSpace, 2009. ISBN 978-1449523763

- Lyons, Martyn. Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., 1994. ISBN 0-312-12123-7

- Mackenzie, G. Calvin and Weisbrot, Robert. The liberal hour: Washington and the politics of change in the 1960s. New York: Penguin Group, 2008. ISBN 1-594-20170-6

- Manent, Pierre and Seigel, Jerrold. An Intellectual History of Liberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-691-02911-3

- Mazower, Mark. Dark Continent. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. ISBN 0-679-75704-X

- Mernissi, Fatima. Islam and Democracy: Fear of the Modern World. Basic Books, 2002. ISBN 0-738-20745-4

- Monsma, Stephen and Soper, J. Christopher. The Challenge of Pluralism: Church and State in Five Democracies. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. ISBN 0-742-55417-1

- Olson, Roger. The mosaic of Christian belief: twenty centuries of unity and diversity. Westmont: InterVarsity Press, 2002. ISBN 0-830-82695-5

- Penniman, Howard. Canada at the polls, 1984: a study of the federal general elections. Durham: Duke University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-822-30821-5

- Perry, Marvin et al. Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society. Florence, KY: Cengage Learning, 2008. ISBN 0-547-14742-2

- Peters, Stephanie. The Black Death. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2004. ISBN 0-761-41633-1

- Pierson, Paul. The New Politics of the Welfare State. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-198-29756-4

- Puddington, Arch. Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. ISBN 0-742-55897-5

- Riff, Michael. Dictionary of modern political ideologies. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-719-03289-X

- Rivlin, Alice. Reviving the American Dream Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1992. ISBN 0-815-77476-1

- Roberts, J.M. The Penguin History of the World. New York: Penguin Group, 1992. ISBN 0-19-521043-3

- Ros, Agustin. Profits for all?: the cost and benefits of employee ownership. New York: Nova Publishers, 2001. ISBN 1-590-33061-7

- Routledge, Paul et al. The geopolitics reader. New York: Routledge, 2006. ISBN 0-415-34148-5

- Schell, Jonathan. The Unconquerable World: Power, Nonviolence, and the Will of the People. New York: Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 0-805-04457-4

- Shaw, G. K. Keynesian Economics: The Permanent Revolution. Aldershot, England: Edward Elgar Publishing Company, 1988. ISBN 1-852-78099-1

- Shlapentokh, Dmitry. The French Revolution and the Russian Anti-Democratic Tradition. Edison, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1997. ISBN 1-560-00244-1

- Sinclair, Timothy. Global governance: critical concepts in political science. Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 2004. ISBN 0-415-27662-4

- Song, Robert. Christianity and Liberal Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-198-26933-1

- Stacy, Lee. Mexico and the United States. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2002. ISBN 0-761-47402-1

- Steinberg, David I. Burma: the State of Myanmar. Georgetown University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-878-40893-2

- Steindl, Frank. Understanding Economic Recovery in the 1930s. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004. ISBN 0-472-11348-8

- Susser, Bernard. Political ideology in the modern world. Upper Saddle River: Allyn and Bacon, 1995. ISBN 0-024-18442-X

- Tanner, Norman. The Church in the Later Middle Ages. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2008. ISBN 1-845-11438-8