Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

| Line 684: | Line 684: | ||

:*Thirdly, the company that laid the pipe isn't necessarily the company selling you the gas. Instead, the company selling you the gas probably leases the pipe from the pipeline company. |

:*Thirdly, the company that laid the pipe isn't necessarily the company selling you the gas. Instead, the company selling you the gas probably leases the pipe from the pipeline company. |

||

:As a final note, you may find [[Oil and gas law in the United States]] an interesting read. --[[User:Jayron32|<font style="color:#000099">Jayron</font>]]'''''[[User talk:Jayron32|<font style="color:#009900">32</font>]]''''' 18:50, 12 July 2011 (UTC) |

:As a final note, you may find [[Oil and gas law in the United States]] an interesting read. --[[User:Jayron32|<font style="color:#000099">Jayron</font>]]'''''[[User talk:Jayron32|<font style="color:#009900">32</font>]]''''' 18:50, 12 July 2011 (UTC) |

||

::Thanks for that very informative answer, Jayron32. The "Gas Company" retailer from your first bullet, is that the same entity as the semi-private "Public utility" in your second bullet? [[Special:Contributions/76.27.175.80|76.27.175.80]] ([[User talk:76.27.175.80|talk]]) 19:05, 12 July 2011 (UTC) |

|||

Revision as of 19:05, 12 July 2011

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

July 7

Wood catching fire from propane or natural gas

How hard is to catch a wooden structure on fire from a propane or natural gas flash (say, one from a barbecue)? I would imagine pretty hard since it is gone very fast, the heat rises and as a gas it doesn't carry nearly as much heat for the same area as a liquid or solid would, but I don't know. Any insights? --T H F S W (T · C · E) 00:10, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- It depends on the surface area and moisture of the wood, along with the length of exposure. Most pieces of wood that can fit on barbecues can be ignited by them, but healthy twigs six feet above a barbecue are unlikely to catch fire unless a lot of exploding grease or the like is involved. 99.24.223.58 (talk) 00:19, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I don't mean if you've got a piece of wood sitting above a barbecue, I mean from the sudden flash if the gas is left running with the lid closed too long. --T H F S W (T · C · E) 01:01, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- If you filled a cubic meter of space with propane until something ignited it, whether it could ignite adjacent wood would depend more on what actually ends up igniting it. If there is a source of ignition, that is something to mitigate. If your barbecue is leaking, then you need to mitigate that or you will always be out of gas or pay too much for your gas bill. You need to describe the situational geometry and surroundings of the grill to get a better answer. 99.24.223.58 (talk) 01:53, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The structure would be unlikely to ignite directly, but there could be something else that does catch fire, like clothes on an attached clothes line, that then provides the sustained flame needed to light the structure on fire. StuRat (talk) 07:21, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Pollination prospects

"One-third of the honeybee population has died off every year since 2006, and evidence points to pesticides used on corn, soy, and wheat crops as the culprits."[1] True? What is the anticipated effect on fruit and vegetable production? 99.24.223.58 (talk) 01:49, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- You may find the article Colony collapse disorder interesting. --Jayron32 01:54, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- If bees all went extinct (which is quite unlikely), then we would need to rely on other pollinators, like hummingbirds and humans, or move to crops which don't require pollination. StuRat (talk) 07:17, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The pesticides used on corn (i.e. maize), at least, are intended to kill the larvae of corn borers and rootworms; and more and more often those pesticides are being generated from within the plants, as a result of genetic modification. Maize relies on wind pollination, so bees wouldn't be a factor. Wheat and soybeans can self-pollinate. The primary impact from loss of bees would be on fruits and vegetables. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 11:20, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- It's rather telling that the original link is by a guy who apparently signed a petition without bothering to see if the claims were true or not. Pesticides have been used for generations. What's special about 2006? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 11:22, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I am ambivalent about this. On one hand I wonder if it is an opportunity to control pollination, which is otherwise a random process, and at the same time reduce the probability of accidental bee stings, which I'd love to see happen. On the other hand, I'm not sure what I would do with control of pollination. Probably more brazil nuts. I'm not sure what most people would do with control of pollination, but I'm not sure it would be better than what bees have been doing. When I was in elementary school the "africanized killer bee sweeping north from Mexico" was the number one impending environmental threat. (Ha! Take that! In your face, africanized killer bees! You all better start making better brazil nuts or I'm cutting my honey budget even further.) 99.24.223.58 (talk) 17:56, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Without bees, it may not be economically viable to hand-pollinate many crops. StuRat (talk) 04:57, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

- That is certainly true. I expect that if bees die out enough that lack of pollination affects crop yields, farmers will introduce more (healthier?) bees, or other insects or birds which can take up the slack. Honestly, I think it's a very serious situation which needs a lot more thought and action by people independent of the manufacturers of the implicated insecticides. I wonder how many more years of decline to 2/3rds of the previous years' population it will take before bees get on the endangered species list. I wonder if fruit and vegetable supplies and prices have already been impacted. 99.24.223.58 (talk) 09:38, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

- Without bees, it may not be economically viable to hand-pollinate many crops. StuRat (talk) 04:57, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

Most commons monkeys

What are the most common monkeys known to humans? --111Engo (talk) 02:55, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I would guess the Rhesus Macaque but I am not seeing a good reference yet. Rmhermen (talk) 03:22, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- If you use the term 'monkey' loosely, I'd suggest that you look in a mirror. AndyTheGrump (talk) 03:33, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Um, you are not monkey, you are an ape. No joke, please be scientific. :) --111Engo (talk) 03:41, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Not necessarily. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 11:26, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Also, humans are not apes, either. We are primates. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 11:27, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, it depends upon how you define "ape", but if you take it to be equivalent to a monophyletic taxonomic grouping, then yes, humans are apes (and apes are a subset of primates). The only way humans aren't considered apes is if you define the term "ape" to be a paraphyletic group explicitly excluding humans (which is not common in scientific circles), or completely reject scientific consensus of human evolution. -- 174.31.204.164 (talk) 15:26, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well he did say loosely. More importantly, if you want to be scientific, monkeys are a paraphyletic group. So from a scientific view, it's questionable if it makes sense to ask a question where the answer can be either in parvorder Platyrrhini or superfamily Cercopithecidae or but not superfamily Hominoidea.... Nil Einne (talk) 04:30, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yup. 'monkey' is a vague term, so I gave a vague answer. (And 'ape' isn't exactly clear either, though I'll suggest that whatever they are, we are too...). AndyTheGrump (talk) 14:09, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Um, you are not monkey, you are an ape. No joke, please be scientific. :) --111Engo (talk) 03:41, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- If you use the term 'monkey' loosely, I'd suggest that you look in a mirror. AndyTheGrump (talk) 03:33, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Ok, will anyone go to the original question? --111Engo (talk) 12:19, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- For the most "commons monkeys", check out wikimedia commons.[2] For the most "common monkeys"... first, define what you mean by "common". Most populous? Most often used in circus acts? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 12:27, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'd assume 'most populous', i.e. which species of Platyrrhini or Cercopithecidae (and not Hominoidea) has the largest total living population. Even this may be difficult to answer, given that large populations tend to be genetically diverse, and it may not always be clear whether they are all the same species. And then there is observer bias - generally speaking, primatologists tend to be more interested in counting rare species than common ones. AndyTheGrump (talk) 14:09, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- On that basis the Vervet monkey of East and Southern Africa is possibly also a contender. Roger (talk) 14:14, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I should think this question would be a no-brainer.[3] Bus stop (talk) 14:23, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Clarification: By "most common", I mean monkeys which are known to most people i.e. monkeys about which most people have heard of and monkeys humans interact with most. --111Engo (talk) 14:27, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think you are asking what is the quintessential monkey—is that correct? As in—what is the iconic monkey, or what monkey comes to most people's minds when they hear the word monkey. If that is what you are asking, I think that different sorts of monkeys would come to mind, depending on which human group were queried. In a society bombarded by media images, I think the most common one is the chimpanzee. Bus stop (talk) 14:44, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- ... which is actually an ape, not a monkey. Gandalf61 (talk) 15:00, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- In that case the clear winner is the Rhesus Macaque as hundreds of millions of Asian people are familiar with them. Many people interact with them on a practically a daily basis - particularly in India. Roger (talk) 14:53, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Year the Duwamish Railroad Bridge in Seattle was built?

I a attempting to finish off a list and create an article on a bridge in Seattle. I have found some in-depth info from engineering journals through Google Books searches, but I am struggling to find a year it was built and think some more info could be useful to create an article. Some keywords and other information that might assist in any searches:

- One of the earliest "heel trunnion" bridges

- Operated by Northern Pacific Railway (I think it is now operated by Burlington Northern)

- Built around 1912

- Seattle landmark (I cannot find an ordinance #) but not NHRP

Any assistance would be appreciated.Cptnono (talk) 03:55, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

BirAli Crater

I've visited this area and uploaded the photo here. How can I know if this were an impact crater, (see also the other one beside on Google maps)?--Almuhammedi (talk) 04:45, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- You can search on the web -- every mention says that it is volcanic. The fact that it is not perfectly round (as you see on the map) also means it is pretty surely not an impact crater. Looking around on the map, there are a number of clear volcanic cones in the area -- you can see one in the background of your photo. The second crater is much more difficult to recognize based on shape, but since there are so many volcanic craters and cones around, it must surely be volcanic as well. Looie496 (talk) 05:20, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Then can I consider it as a volcanic crater lake? Can I also add it to the list of volcanic crater lakes? --Almuhammedi (talk) 13:24, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, I saw at least a dozen sites that identify it as volcanic, but none of them was a reliable source. It would be good to find a book or other published source for the information before adding it to an article. Looie496 (talk) 16:30, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The lake is Shouran lake according to Wikimapia here [4]. It looks like a maar, formed by an explosive phreatomagmatic eruption, but that's pure OR. Mikenorton (talk) 22:10, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Try one of the following links on Google Scholar: Metasomatism of the shallow mantle beneath Yemen by the Afar plume—Implications for mantle plumes, flood volcanism, and intraplate volcanism (ABSTRACT) or Clinopyroxene-rich lherzolite xenoliths from Bir Ali, Yemen—possible product of peridotite/melt reactions (PDF, 6 pg.). ~AH1 (discuss!) 16:46, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- See also Scoria in Yemen. Mikenorton (talk) 12:13, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

- Try one of the following links on Google Scholar: Metasomatism of the shallow mantle beneath Yemen by the Afar plume—Implications for mantle plumes, flood volcanism, and intraplate volcanism (ABSTRACT) or Clinopyroxene-rich lherzolite xenoliths from Bir Ali, Yemen—possible product of peridotite/melt reactions (PDF, 6 pg.). ~AH1 (discuss!) 16:46, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- The lake is Shouran lake according to Wikimapia here [4]. It looks like a maar, formed by an explosive phreatomagmatic eruption, but that's pure OR. Mikenorton (talk) 22:10, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, I saw at least a dozen sites that identify it as volcanic, but none of them was a reliable source. It would be good to find a book or other published source for the information before adding it to an article. Looie496 (talk) 16:30, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Then can I consider it as a volcanic crater lake? Can I also add it to the list of volcanic crater lakes? --Almuhammedi (talk) 13:24, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Why not adopt measurement scales better suited for very large quantities?

I find that I can imagine the scale of some colossal entities if they are given in large but familiar units, even where those units are Olympic pools of water, or elephants. What is the use of telling me that a large ocean has so many litres in it? They might as well use thimble-fulls. And you get figures like 10 ^ 17, which mean nothing to anyone.

My prime target for amendment would be using miles or kilometres for astronomical distances. I remember a mile as being from my back fence to Mrs Carruther's chook pen. It's a short walk. We use light years for very large distances - why not use them for distances in our local solar system. For example, it is about 8 light minutes to the sun, and about 1.5 light seconds to the moon. This gives one a pretty good idea of the relative distance of the sun and moon from Earth. The distances to Jupiter and the other gas giants are about 4 to 8 hours.

Voyager 1, launched over 30 years ago is the furthest man-made object from Earth. The NASA site http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/ gives it as being 17,481,723,800 kilometers away, a figure which is billons of times further than Mrs Carruthers chook pen - and means nothing to most people. It also gives the distance as 117 AU (Astronomical Units - a single one being the distance between the Earth and the Sun.) Now, if we accept that 1 AU is about 8 light minutes, then Voyager 1 is about 15.5 light hours away, or nearly double the distance to Jupiter. The Sun is 8 minutes away, and Voyager is 15.6 hours away. Hey, suddenly everyone can see these distances in perspective! This is just common sense. Why doesn't NASA use this instead of AU's and kilometers? And the speed of light is totally constant too, an additional plus.

Same goes for Olympic swimming pools. Everyone has been in one and has a good idea of how much water they hold. If you had a unit "Kilopool", i.e. a thousand swimming pools, you could express the scale of very large quantities of liquid in a way that a person could easily visualise. For example, a Kilopool would be a cube, with each side having 10 Olympic pools. In my view, the whole system of measuring large quantities in thimblefuls and feathers and then announcing that something is 10^17 is absurd, and we should adopt scales like the ones I've suggeted here. It's a no-brainer really, or I should say, a one-pea brainer.

I blame the frogs (the French) for starting this. The centimetre was apparenty picked as a basic lengh unit because it did not naturally measure anything, unlike the inch, which is about the length of man's thumb. The metre is too long to be a step, too short to be a room length, and so on.

Now, watch, the Kilopool idea will suddenly and quite by "coincidence" be put forward as an official unit. And will I get a jot of recognition? No sir! I'm going to put on my alfoil thought blocking cap right now. Myles325a (talk) 04:49, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- If you don't mind removing your tin foil hat for a minute...

- You seem to be ranting about the lack of using measurements which result in small numbers. I am with you on this matter; for some godforsaken reason the astronomical community continues to use CGS units. I always found it ironic that the people who study the largest and heaviest objects in the universe use smaller units than the kilograms and meters that most scientists use. I believe in using units that result in small numbers for the scales you are using, although not to the point of making unit conversions awkward.

- However, you have to see the conundrum that we scientists have when communicating to the general public: if we use crazy units like megaparsecs, light minutes, and AUs, Joe Shmoe has no idea what those are. Kilometers, as you say, are about 60% of the walk from your back fence to Mrs Carruther's chook pen, which was a short, easy walk, and an easy distance for you to comprehend. Could you tell me how long it would take to walk a parsec? To me, the best solution is to give both a normal unit (miles) and a small-number unit (parsecs or what have you), which would satisfy both crowds.

And contrary to your assertion that NASA does not do this, on this page they list Voyager 1 as being "16.9 billion kilometers (~ 113 AU)" from Earth. - Additionally, if you look at meter, you can see that it was originally defined as one ten-millionth of the distance from pole-to-pole, to avoid using arbitrary objects to define the measurement like "foot". Having a standard unit of measurement was useful for science. Now if only we could convince those damn Americans to use it. You can put your foil hat back on now :) -RunningOnBrains(talk) 05:08, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The metre is actually one ten-millionth of (North) pole to equator. AndrewWTaylor (talk) 08:03, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I have struck one of my previous comments, since apparently I need to learn how to read, but this leads me to a further point: why do you think light years or light minutes are easier for the public to understand than an Astronomical Unit (AU)? To me, AUs make more sense in the solar system, especially because we're often talking about distance from the sun, so when I see that Voyager is 117 AUs from the sun, I think "hm, so it's more than 100 times further away from the sun than we are!". To me that's much more understandable than "light minutes", but it's all personal preference.

- I don't know about you, but I'm sure that not every one has been in (or even seen) an Olympic size swimming pool. I certainly haven't, at least not recently. And no scientist that I know of actually uses this measure. Your idea for using pool-length for volume makes no sense, since these pools have different length, width, and depth, so it wouldn't really be even on each side (they aren't a standardized depth anyway: if you read the link, they only have to be a minimum depth). Vulcanologists and oceanographers deal with extremely large volumes all the time, and so they use units like cubic miles and cubic kilometers (and my favorite-sounding one: Sverdrups). Why aren't these acceptable? As I said above, you can't really satisfy everybody at once.

- I'm personally a fan of Rhode Islands as a unit of measure for area. Which do you prefer?-RunningOnBrains(talk) 06:05, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

OPmyles325a back live. Hi RunningOnBrains, I was writing a hefty reply to your note when a glitch occurred and I lost the lot. When I got back, you had made another entry. Thanks for the effort. As I wrote initially, I can understand kilometers and miles very well, because I experience such directly every day from childhood, as I had earlier supposed everyone else did. My objection to miles / kays being used for astronomical distances is that the familiarity we have with these distances is drowned out by the sheer number of the miles/kays involved. I don’t know where the cutoff point is, but I strongly suspect that billion is about the farthest an ordinary human mind can take in. The problems with AU’s are twofold. First, most laypeople have little notion of how far the Earth is from the Sun (or the Moon for that matter). The value of AU is depleted if many think Earth /Sun distance is a matter of thousands or trillions of miles / kays. The second problem is that AU is only good for the Solar System and really only the inner Solar System at that. Once you get into interstellar space and then intergalactic space, AU’s become very much like miles / kays – there are just too many of them to get a grip.

The great thing about light speed is that it is based on time, which humans experience directly and fundamentally. EVERYONE knows what 10 minutes is, and also 10 years. If a driver asks for directions and you tell him that a warehouse is “10 minutes yonder”, then you will never get a request for clarification. It’s as clear as can be. That’s because he knows the normal speed of a car, and he knows what 10 minutes is. You can tell someone that light could travel around the equator 7 times in a second. Anyone who has an atlas will take that on board. Now if you tell them that the Moon is about 1.5 seconds away, he can see that means that it is about 11 Earth circumferences away. And if you tell him that the Sun is 8 minutes away, he can compare that with the distance from the Moon, and start to get a very good idea of the general nature of where we are. This is not the case when you start rabbiting on about “billions of miles” and so on. And as I said initially, you can then proceed to tell him that the gas giant planets are about 4 to 8 hours away, and Voyager is about 15 hours away. What could be simpler? It is a matter of taking what the reader is well familiar with, and then building on that, but not in a way where suddenly you expect him to visualize figures with 15 zeros in them.

Once we get beyond the planets, the system still works well. Anyone who has done some history will have a good idea of what “a thousand years” means. After all, people can live to be a hundred, and a thousand is no more than 10 of them, with one born as the other reaches 100. Galactic distances are amenable to figures no larger than thousands of light years, so we are in a position to comprehend them with relative ease. Try telling someone how far we are from the galactic centre in AU’s - it might as well be centimeters. So I cannot fathom why the NASA site - and thousands like it - don’t permanently ditch this ridiculous, and artificial, feathers and thimbles approach, and use the superb scale that has been provided for us in the constant ruler of light. I was surprised to hear you say that you had never been in, peed in, or been seen in, an Olympic swimming pool. What, have you never even watched a swimming event at the Olympics? Not to worry, we could have a base unit of a Wading Pool. I guess being an Aussie, I just assumed that everyone spent summer diving and cavorting in large pools. Yes, a flaw with the Kilopool idea is that an Olympic Pool is rectangular, not square, and it is deep at one end and shallow at the other. But these flaws are not serious. The important thing is that from early childhood, an Aussie kid is up and down the lanes in the pool, dives down to the bottom, and thus gets a very good idea of how much water there is, not only with his or her mind, but with every inch of their bodies.

In the case of employing units which, as you put well, give small and comprehensible numbers to describe large quantities, it is necessary to use entities which are well-known to those likely to come across them and be interested in them. So it appears that I have been guilty of cultural imperialism when I suggested the Kilopool. In much the same way as using "Rhode islands" as a base is culturally insensitive, because outside of the U.S. few people would know how big that means. (On an aside, it is interesting to see how often Belgium is used to denote large areas, because Belgium is quite small, probably smaller than most people realize.)

The reason that elephants are often used for large weight concerns is that writers are assuming that people have seen them in zoos, and have a rough idea of how heavy they would be. Blue whales are much heavier, but then they float and that massive weight is not so evident. Myles325a (talk) 07:00, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Ask yourself how accurately in percent you could establish, maintain and transfer to others your proposed pool-length unit. Then see the article Metre and compare. Then please look into the usefulness of the Logarithmic scale which is a good way of managing very small and very large quantities that are inevitably beyond tangible comprehension. In some cases such as sound amplitude and sound frequencies in music the log scale actually agrees better with human experience than a simple linear scale. Please don't call the citizens of France "frogs". They are a proud nation with nuclear capability and veto right at the UN so it is unwise to get them hopping mad. See Australia–France relations. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 08:23, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I have a better idea. Why don't educate the public better so they can understand what a power like 10 ^ 17 mean? Dauto (talk) 17:49, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- What does 10^17 mean to you Dauto? It is a difficult number to conceptualize. Think of it this way, if 10^17 grains of rice were given to each person on earth, that would be around 1000 lbs per person. That much rice would fill enough grain cars to make a train long enough to circle the earth 13 times. Education can only go so far when it comes to conceptualizing incredibly large numbers. Googlemeister (talk) 18:50, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think you did a pretty good job at conceptualizing it proving my point, thank you. Dauto (talk) 19:21, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Granted, but it took me 8 minutes, a graphing calculator and looking up the size of a railroad hopper car to do it. Googlemeister (talk) 14:09, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- A 60-bit binary computer can keep track of every grain of rice through a calculation without losing or gaining a single grain. Conceptualise that. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 20:03, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The ocean volume is often measured in cubic kilometres, rather than in mass units of "1.024 ± ~0.005 x 109 metric tonnes s.v.". ~AH1 (discuss!) 16:37, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think you did a pretty good job at conceptualizing it proving my point, thank you. Dauto (talk) 19:21, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- What does 10^17 mean to you Dauto? It is a difficult number to conceptualize. Think of it this way, if 10^17 grains of rice were given to each person on earth, that would be around 1000 lbs per person. That much rice would fill enough grain cars to make a train long enough to circle the earth 13 times. Education can only go so far when it comes to conceptualizing incredibly large numbers. Googlemeister (talk) 18:50, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I have a better idea. Why don't educate the public better so they can understand what a power like 10 ^ 17 mean? Dauto (talk) 17:49, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

To the original question, how does making the base units larger help? A light year is so utterly unimaginably large and literally inconceivable (I mean 'literally' literally here.) I can't imagine 1 minute compared to one year on any practical level, so using numbers this big actually help illustrate just how crazy huge (and terribly small) nature is. I mean, at a certain point, the difference between a billion miles and a billion kilometers loses much meaning to the average Joe, even if the difference is so big. Mingmingla (talk) 01:04, 12 July 2011 (UTC)

Species identification request

Hello, I was wondering if anybody could help me identify a few species of insects and plants before I upload the pictures to Commons. There are three different species of plants, one with pink flowers, one with white and pink flowers, and one with white flowers. There are also two species of dragonfly, one which is bright green and black (see pictures here, here, and here) and a yellow and black one. All pictures except the first were taken at Tirta Gangga lake in East Lampung Regency, Lampung, Sumatra while the first picture was taken near the regent's office in Sukadana, Lampung. Any help would be greatly appreciated. Crisco 1492 (talk) 05:03, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- "one with white and pink flowers" = Plumeria

- "one with white flowers" = Bougainvillea

- Sean.hoyland - talk 11:31, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Would Plumeria rubra be the best guess for the one with white and pink flowers? Crisco 1492 (talk) 15:20, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, I guess from the leaf shape but there are many named cultivars. Sean.hoyland - talk 15:45, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The joys of being a botanist. I have uploaded the Plumeria at File:Plumeria at Tirta Gangga, Sumatra.jpg, but we have many, many, many ad infinitum better pictures of Bougainvillea. So one plant and two dragonflies to go. Crisco 1492 (talk) 16:01, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, I guess from the leaf shape but there are many named cultivars. Sean.hoyland - talk 15:45, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Would Plumeria rubra be the best guess for the one with white and pink flowers? Crisco 1492 (talk) 15:20, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

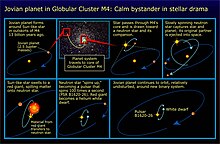

what will happen If any massive star comes to be black hole and it has planets?

A.mohammadzade--78.38.28.3 (talk) 06:22, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- While I don't see any reason planets couldn't have stable orbits around a black hole, they couldn't remain after a star has a supernova explosion leaving a black hole, because the portion of the supernova which blasts outward would destroy any planets there. However, there might be some complex multiple-body gravitational interaction which brings new planets into stable orbits about the black hole, later on. StuRat (talk) 06:34, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- A supernova explosion would not necessarily disperse a planetary system completely; see PSR B1257+12 for an example of a planetary system around a neutron star, which is the end result of some supernovae.-RunningOnBrains(talk) 07:05, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, but the concern here is the larger supernovae which produce black holes. Would any planets survive those ? StuRat (talk) 08:16, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The back of my envelope suggests that a supernova is probably survivable for large and distant planets, provided one is only asking whether the planet receives less energy than its gravitational binding energy when exposed to a core collapse supernova. A large fraction of the planet would still be completely ablated, but the event might be survivable (provided survivable merely asks whether any gravitationally bound nugget still exists). Dragons flight (talk) 09:11, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Hmmm, I though that the planets of PSR B1257+12 were formed after the neutron star formed... Count Iblis (talk) 14:32, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

I abslotly think that the black hole (not super nova) cannot change condition and rotational orbit of planets round early star except one of them come to roche limitMohammadzade--it means that if any star had planets and end its energy to be black hole those planets still rotate round main star 78.38.28.3 (talk) 06:41, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Consider that all exchangings are happening inside the event horison.and consider the binary star systems which first detected black holes --

78.38.28.3 (talk) 06:58, 7 July 2011 (UTC)A.mohammadzade

Let's imagine that somehow a planet is shielded from the supernova of its host star and survives that star becoming a black hole. As the star has lost mass in the explosion, its overall gravitational field is diluted, and the planet would move away from the Black Hole, and its orbit would be longer. I would imagine, the orbit would be further altered as the Hole's gravitational attraction comes from a point, not a finite area. The forces involved in the preservation of angular momentum would thus become intensified, and if the planet did not face the Sun all the time before, it might do so now. Also, it would now be very dark on the planet, and life would be much harder. If there was an intelligent and technological species there, they might be able to survive, using the energy released by the tidal forces of the Black Hole on their home planet, and living near hot vents and volcanos and the like. Or alternatively, they might exploit the Black Hole by sending material streaming into it, and collecting the energy dissipated when the Hole rips it apart and spaghettifies it. If they have sophisticated control over genetic processes, they might biologically engineer their species to be only an inch or so high, with work to be done by robots. That way, they would need very little food or fuel, and could live happily on the smell of an oily rag. Myles325a (talk) 07:16, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- please dont mix supernova with black hole. --78.38.28.3 (talk) 09:30, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Do you have another mechanism for forming a black hole that does not involve a supernova? --Jayron32 19:52, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The big bang likely made primordial black holes, such as the supermassive one at the center of our galaxy. That could explain dark matter with intermediate mass black holes and according to Lacki and Beacom (2010) that would explain why people haven't found any weakly interacting massive particles. 99.24.223.58 (talk) 20:39, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Do you have another mechanism for forming a black hole that does not involve a supernova? --Jayron32 19:52, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- There may be some minor relativistic effects, but the shell theorem tells us that (with Newtonian gravity, which is a good approximation at the distances we're talking about) there is no difference between the gravitational field of a point-mass and the gravitational field of a spherically symmetric object (which a star is, give or take an equatorial bulge). I don't understand your comment about tidal locking. If gravity is reduced, then so are tidal forces. They are also reduced by the increased distance you mention. The chance of becoming tidally locked would reduce (or, perhaps more accurately, the time it would take to become tidally locked would increase). In order for the civilization you describe to exploit the block hole, they would need to get closer to it than the original radius of the star, since outside that radius nothing has really changed. That won't be easy. Geothermal energy would work for a time, although the planet will cool down quicker without a star keeping it warm (although that could still be millions of years, I'd need to look up some numbers). --Tango (talk) 12:03, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- You are almost certainly right, Tango, as I gain my inspiration telepathically from my overlords from Fubia, and they often pull my leg. But still, granted the tidal forces would decrease as the planet moved away from its sun, but isn't it still true that the concentration of the Sun's mass affects the rate of tidal locking? For example, the Moon is tidally locked to the Earth. Suppose the Earth was made of some very heavy stuff and was only 10 miles in diameter. This would concentrate the Earth's gravitational attraction in a more focussed way, whereas now it must be diluted as a larger part of the Earth is involved in the attraction. To take a reductio ad absurdum approach, imagine the the Earth is a billion miles in diameter. To all intents and purposes, a small satellite of such a large object would feel the attraction of its host almost equally at every point facing the host.

- And I am wondering at your point re: geothermal energy running out. I am thinking of Jupiter's moon Io, which is extremely active as it is kneaded by its giant host and other moons. When I first read about this, it came to mind that it is no longer necessary for a planet to be within a Goldilocks band around the Sun in order to obtain enough heat for life to form and endure. A very remote body could be in Io’s situation and have heat created within itself as a result of gravitational flexing. Now, if instead of Jupiter, a Black Hole was the main host body, then a planet could be flexed in this way for as long as the Hole endures, which is close enough to forever. This is more true the more powerful the gravity of the Hole, and the smaller the planet, so that the orbit of the planet is basically stable. Life could evolve near deep underwater fissures (and some experts think this is where life may have first appeared on Earth.) In Io, the kneading is so intense, that the entire surface is in constant flux and turns over regularly. Life probably could not evolve there, even if there was water. But I had never thought that Io’s geothermal energy would run out, I had assumed that it would go on for as long as it was a satellite of Jupiter. Am I wrong in this? Myles325a (talk) 04:36, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

about the matter said abow:

Jupiter's moon Io, which is extremely active as it is kneaded by its giant host and other moons.let me to say:I am sure existing theories about the formation of planets in solar system might be developed to contain the reason of Io activity and saturns moon volcanic activity , so for titan surface . consider that [[late heavy bombardmant ]] is very poor display for planets and moons molten core . and [[Impact theory for the formation of moon ]] might be developed , excuse me I am studying about them . and I hope to find new results .And I will say them in suitable place.

akbarmohammadzade--78.38.28.3 (talk) 09:30, 10 July 2011 (UTC)

The supernove makes neutron star and remnant nebula ,any star which changes to black hole , condences to Schwartz shield radius and matter disapiers in any point , that dosenot through the matter to interstellar space , this is diffrence between neutrone star and black hole , neutron star or pulsar is not same to black hole and it send pulses .Ilast said this sentences about them:

I love supernovae for their first brightness as some people suppose them new star , their palpitation such as our heart , and their expanding such as universe , and their rule in our life with sending material of our body" A. mohammadzade somebody used to say something about black holes , I prefer to say about supernovae , the first one is death and being secretary , the second one shows celebrating and brightness , and life .A. mohammadzade — Preceding unsigned comment added by 81.12.40.120 (talk) 20:29, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, as mohammadzade has put it so poetically "the first one is death and being secretary", You read it here first. I would really like a supernova to take dictation from me. My first note would be "Don't you dare blow up until I am a thousand light years away." Myles325a (talk) 04:39, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

Estrous vs Menstruation

I've read the Estrous cycle article, and the Menstruation article. The latter is primarily focused on humans, to my disappointment. I have a few questions:

Which appeared first, estrous or menstruation? Do more mammals go through estrous or go through menstruation? Is estrous equally powerful across all species that have it? (example: my female cats became mindless horny robots for ~10 day periods every month or so before they were spayed) Apart from humans, does menstruation not have as strong a mental effect? Why?

Thanks for your help! The Masked Booby (talk) 06:10, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Just a spelling note: I think it's going through estrus, not "estrous". Estrous is presumably an adjective. Another one to add to my list of these commonly confused pairs: Mucus/mucous, callus/callous, phosphorus/phosphorous. In every case the second word is an adjective, but commonly misused as a noun. --Trovatore (talk) 23:32, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

I fixed your Estrous cycle link which was not working. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 07:42, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, I think it should be oestrous, but I can cope with non-classical spelling. HiLo48 (talk) 00:23, 10 July 2011 (UTC)

- Even in Commonwealth spelling, that's still one too many o's for the noun — should be oestrus (but of course oestrous cycle). --Trovatore (talk) 07:48, 10 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, I think it should be oestrous, but I can cope with non-classical spelling. HiLo48 (talk) 00:23, 10 July 2011 (UTC)

- After spending the better part of a half hour chasing this, I came up with the following which I added to menstruation: "Though there is some disagreement in definitions between sources, menstruation is generally limited to primates. It is common in simians including Old World monkeys and apes and New World monkey, but variably expressed in prosimians, being completely lacking in strepsirrhine primates and possibly weakly present in tarsiers. Outside the primates it is known only in bats and the elephant shrew, an insectivore.[1][2][3][4]" I didn't comment on a controversy, running back to 1898, about whether the elephant shrew isn't really menstruating because ovulation occurs at that time (or in a low-grade online source I found, shortly afterward)[5] Note that aside from the elephant shrew - doubly ambiguous because its taxonomy has also been disputed - all of the menstruators appear to be in Archonta. Wnt (talk) 18:56, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

checking xray escape from baggage machine

A friend works at an airport, and the other day a passenger had a geiger counter with them them to observe the increased radiation at altitude. He let the staff put it through the xray security machine and it showed a higher reading, no surprise. but then when it was held at the conveyer belt it showed a fluctuating reading when the curtains were moved by baggage coming through.

What device can he use to detect if xrays are getting out? would a digital camera (which detects infrared) also be useful? It would seem that any xrays getting at people would be bad. Polypipe Wrangler (talk) 06:11, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- He seems to have the right device. If you wanted a movie showing it, you would need a fluoroscope screen. Note that the main danger is to the security guards who stand there all day long, and might want to wear protective clothing. You didn't ask, but the two cures I can think of are either to stop the belt, close the curtains, use the X-ray, then turn the X-rays off and restart the belt, or to make the belt longer with multiple sets of lead curtains. StuRat (talk) 06:37, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- A Geiger counter responds to any kind of ionising radiation so what came through the curtains may not have been xrays. One can speculate what kind of radioactive trace someone's baggage may have left on the conveyer. I would expect a rubber curtain to be transparent to xrays but it might also act as a diffraction grid. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 07:39, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Are they rubber curtains ? What would be the point in those ? I assumed they contained lead or some other heavy element, to act as an X-ray shield. StuRat (talk) 08:12, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes I was going to say a similar thing, [6] suggests they contain lead. Nil Einne (talk) 08:15, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Curtains like these? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 08:35, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- That photo is of a baggage claim conveyor, not the X-ray machine. The baggage claim conveyor typically connects to some outside area. The rubber curtains are just to keep the cold/hot air out of the building. Rckrone (talk) 15:13, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes I'm thinking something like [7] or [8]. Unless you work in airport security you only tend to see the smaller ones for hand luggage nowadays from my experience because check in baggage is handled behind the scenes. Nil Einne (talk) 16:13, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

- That photo is of a baggage claim conveyor, not the X-ray machine. The baggage claim conveyor typically connects to some outside area. The rubber curtains are just to keep the cold/hot air out of the building. Rckrone (talk) 15:13, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Curtains like these? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 08:35, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The proper test for this would be to require TSA employees to wear dosimeters. 99.24.223.58 (talk) 18:42, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- A dosimeter would be useful, but wouldn't tell you precisely where the radiation leak was. StuRat (talk) 08:39, 10 July 2011 (UTC)

Can I ask: Is there any fundamental difference in operation and effect between the electrical stunning techniques used on animals pre-slaughter, and the Taser stun-guns used by various police forces?

If the taser is apparently very painful, is the pre-slaughter technique any less painful for the animals? (I've never been tasered, thankfully). Eliyohub (talk) 12:18, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The taser is painful because it doesn't kill. However, it is not nearly as painful as it appears to be. We associate tensed muscles with pain. The electrical current causes the muscles to tense up. So, bystanders assume that there is extreme pain. It is actually far less painful than accidentally touching and discharging a CRT (from experience - the CRT knocked me out cold, but the taser was just a sting). In a slaughterhouse that I visited, cow prods give the cows enough of a sting to make them move. It isn't enough to cause them to completely tense up and hit the floor. Before slaughter, the cows had one metal clip attached to an ear and another to a nostril. Then, an extreme amount of current was sent through the cow's brain. The cows didn't tense up or cry out or anything. They went from looking around to being dead on the floor in an instant. So, it is obvious that both the operation and effect are very different. -- kainaw™ 12:41, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Hardest Known Material

So, lonsdaleite is harder than diamond. But... what is the hardest material known to man? 68.48.123.29 (talk) 13:42, 7 July 2011 (UTC)luos

- Diamond is the hardest confirmed naturally occurring substance, but several attempts (i.e. Aggregated diamond nanorods, Rhenium diboride, etc.) have been made to synthetically form a material that is harder. It is hard to say, however, as many of these reports remain unconfirmed. This article may interest you, as it pertains to some very rare substances (including lonsdaleite) w/ similar structures as diamond, but may be much harder due to various reasons. Tyrol5 [Talk] 14:53, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Quarkium. Degenerate matter is the densest material in the Universe, so quarkium (which would be to quark stars what neutronium is to neutron stars) would be the most dense. YMMV as to whether this qualifies as "known to man"? -- SmashTheState (talk) 20:09, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Dense yes, but hard? You're sure it's not a superfluid? Wnt (talk) 20:20, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- If we were to use the Mohs hardness scale, then quarkium would easily outmatch any other substance, since attempting to scratch something that dense would be utterly futile. I don't think its state really matters at that density. Although you may be right, the physical properties of something like quarkium are probably wildly bizarre, and I don't have the scientific knowledge to even guess at it. -- SmashTheState (talk) 21:46, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The problem is, the conditions under which quarkium exists are conditions under which any matter will be converted to quarkium. (At least, that's my understanding.) If you got a diamond in contact with the quarkium in order to try and scratch it, you wouldn't have a diamond any more. --Tango (talk) 12:06, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Depending on how much quarkium you have on Earth, the energies involved in any material attempting to contact it (or even attempting to hold it?) would likely annihalate the entire planet. ~AH1 (discuss!) 16:06, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- The problem is, the conditions under which quarkium exists are conditions under which any matter will be converted to quarkium. (At least, that's my understanding.) If you got a diamond in contact with the quarkium in order to try and scratch it, you wouldn't have a diamond any more. --Tango (talk) 12:06, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- If we were to use the Mohs hardness scale, then quarkium would easily outmatch any other substance, since attempting to scratch something that dense would be utterly futile. I don't think its state really matters at that density. Although you may be right, the physical properties of something like quarkium are probably wildly bizarre, and I don't have the scientific knowledge to even guess at it. -- SmashTheState (talk) 21:46, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- At low temperatures diamond is harder than boron nitride, assuming an oxygen atmosphere. 99.24.223.58 (talk) 20:52, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

Third most important blood property

What is the 3rd most important blood property after blood group and Rh?--188.146.90.106 (talk) 16:21, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- WHAG here but I'd say it was clotting factor. --TammyMoet (talk) 17:16, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I don't think the question is valid. Blood group is practically irrelevant except for the practice of blood transfusion from human donors, which was invented only recently and will probably become obsolete just as quickly. Rh creates a notable fertility problem, yes, but it's only our current level of understanding which makes it important to test in advance. Presently perhaps CCR5-Δ32 is the most important trait, at least in Africa. It shifts over time, and in the long run, perhaps everything is of equal importance in evolution, as otherwise the more important part would receive special attention. Wnt (talk) 19:01, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- THE most important blood property is its role in transporting nutrients and wastes, right? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 20:18, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Oxygen/CO2 transportation is much more important.

- Hmmm, are we talking simply about characteristics, or about genetically variable traits? My answer concerned the latter. I suppose blood does have specific "purposes" which are indeed more important than others, but these are things which are genetically non-negotiable. Wnt (talk) 22:38, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Since blood group and Rh were mentioned, I presume the question refers to properties that determine compatibility. This may be a homework question, but what the hell, I'll answer it anyway: as our Blood transfusion#Compatibility testing article says, once blood type and Rh have been verified, it is important to screen for antibodies that may react with the donor blood. Looie496 (talk) 22:50, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- "Screening for antibodies" describes all the tests. ABO blood group and Rh blood group are all about antibodies. A, B and Rh are antigens that the person receiving the transfusion may have antibodies to. If they have those antibodies, then the antibodies will attack the blood. The question, therefore, is which antibodies is it the next most important to screen for. --Tango (talk) 12:09, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Neither Cross-matching or Blood transfusion seems to mention which antibodies they are testing for. Rmhermen (talk) 13:36, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- You don't need to test for specific antibodies. You just mix the donor blood with the receiver's blood and watch for a reaction. It doesn't really make any different which antigen in the donor blood is being reacted to. If there is a reaction, then the blood isn't compatible. --Tango (talk) 22:33, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Neither Cross-matching or Blood transfusion seems to mention which antibodies they are testing for. Rmhermen (talk) 13:36, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- "Screening for antibodies" describes all the tests. ABO blood group and Rh blood group are all about antibodies. A, B and Rh are antigens that the person receiving the transfusion may have antibodies to. If they have those antibodies, then the antibodies will attack the blood. The question, therefore, is which antibodies is it the next most important to screen for. --Tango (talk) 12:09, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Physiology is an interconnected system. This question is like asking which mole in a Whac-A-Mole game is most likely to pop up next. 99.24.223.58 (talk) 20:53, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

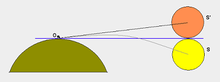

Astronomical observation time

Are there any time corrections being made during Moon/Sun and star observations because of incoming light delay, such as that of 8 minutes in case of the Sun?--188.146.90.106 (talk) 16:26, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The timings for regular events (i.e. sunset) are based on actual physical sunset, while sunlight (perceived by humans as the sun itself) is still visible for several minutes due to atmospheric refraction (see image to right). For star observations, however, the timings are determined based on predicted position in the sky (sometimes it can take several millions of years for light to reach Earth, enabling us to "see back in time"). For nearby astronomical objects (i.e. the Moon), the time delay (something like two seconds) is negligible and is not taken into account specifically in determining observational timings. Tyrol5 [Talk] 16:44, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I was just reading something neat about that topic - the speed of light was first correctly measured by observations of the moons of Jupiter! It never ceases to amaze me how the invention of lenses opened up so many fields of biology and physics to explosive growth all at once. Wnt (talk) 19:12, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The thing is, it doesn't take 8 minutes for "just" the light from the sun to reach us, it takes 8 minutes for ANY information from the sun to reach us. So there's nothing to correct for. From earth, the sun IS on the horizon when we "see" it there, not 8 minutes previous, absolutely no part of the sun is there 8 minutes prior, not the gravity, not the light, not the information, not even any mystical magical "sun" force we haven't discovered yet (well i'm not 100% certain about that one, but call it 99.99% certain) For all we know, the sun might have completely vanished a few minutes ago and it would be completely impossible for us to know until that information reached us, at the speed of light. Vespine (talk) 05:00, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Let's say the Sun vanishes exactly at sunset from a given position on Earth with an unobscured western horizon and no refraction. Would we fail to notice the Sun disappearing until it is already no longer visible on the horizon? ~AH1 (discuss!) 16:03, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- i'm no astro physisyst and this really bends my brain.. with the sun 8 minutes away, say it vanishes when it is right on the horizon on earth. Well, the earth will keep rotating for 8 more minutes before the last light reaches it, (light and gravity and everything, that makes me thing of another question, but I'll ask it below).. Now with the sun and the earth that's pretty straight forward, but what about a galaxy 10 billion light years away, but the universe is only 13.75 billion years old, we see that object where it was 3.75 billion years after the big bang, but now we're 10 Billion light years away from it... so we have moved apart 10 Billion light years in 3.75 Billion years? But we're not ACTUALLY 10 billion light years apart, are we? Presumably the ACTUAL distance between us and a galaxy that we see 10 billion light years away is far greater since it has had 10 billion years to move some further distance away? Since the light that we're seeing now originally left.. This is the point where my brain melts down.. Vespine (talk) 02:50, 12 July 2011 (UTC)

- Let's say the Sun vanishes exactly at sunset from a given position on Earth with an unobscured western horizon and no refraction. Would we fail to notice the Sun disappearing until it is already no longer visible on the horizon? ~AH1 (discuss!) 16:03, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- The thing is, it doesn't take 8 minutes for "just" the light from the sun to reach us, it takes 8 minutes for ANY information from the sun to reach us. So there's nothing to correct for. From earth, the sun IS on the horizon when we "see" it there, not 8 minutes previous, absolutely no part of the sun is there 8 minutes prior, not the gravity, not the light, not the information, not even any mystical magical "sun" force we haven't discovered yet (well i'm not 100% certain about that one, but call it 99.99% certain) For all we know, the sun might have completely vanished a few minutes ago and it would be completely impossible for us to know until that information reached us, at the speed of light. Vespine (talk) 05:00, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- I was just reading something neat about that topic - the speed of light was first correctly measured by observations of the moons of Jupiter! It never ceases to amaze me how the invention of lenses opened up so many fields of biology and physics to explosive growth all at once. Wnt (talk) 19:12, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Regarding special relativity and time dilation

Let's say Planet A and Planet B are 100 lightdays apart. A spaceship leaves Planet A and heads to Planet B, travelling at about .99 c (from the relative position of Planet A). While travelling, the spaceship broadcasts a song by radio towards each of the planets.

Now, as I understand it, the following will occur:

- The ship will reach Planet B in about 102 days from the viewpoint of Planet A.

- The song will be redshifted on Planet A (and thus slowed down), and blueshifted on Planet B (and thus sped up)

- Time will pass more slowly on the spaceship, relative to the two planets (although, to the spaceship, time seems to pass normally, and everything else is sped up).

So, the questions I have are:

- How long will the journey take relative to the spaceship? (exact figures aren't necessary, just ballpark)

- How long will the journey take relative to Planet B? This is what's confusing me the most. So the ship would leave Planet A, and that light would reach Planet B 100 days later, but the ship obviously couldn't then arrive one day later. So time dilation would have the ship move more slowly through time to "correct" this. Err... wait a second, am I answering my own question?

Heh, typing it all out actually made it make more sense. So would it then appear to take about 102 days for the journey from each vantage point (with time dilation affecting the ship)? Also, would the song sent from the ship appear to be the exact same speed to each planet, despite being redshifted for A, and blueshifted for B? I guess my main question is: am I getting this?!

Cheers. --Goodbye Galaxy (talk) 16:30, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Not sure about the spaceship's apparent trip duration offhand, but I can answer the others.

- If Planets A and B are at rest with respect to each other (you don't specifically say this, but I think it's your intent), then each observes the trip to take the same amount of time. 102 days sounds about right, but I haven't done the math.

- Planet B will in fact only see light from the ship's departure a couple days before the ship actually arrives. This is fairly straightforward, since B observes the ship approaching at .99c, moving just behind the light from its departure.

- The song will be redshifted towards A and blueshifted towards B. The shifts will be of similar magnitude but opposing direction. Assuming the song is played for the length of the ship's voyage, each planet receives the song over a period of (departure day + transmission lag) to (arrival day + transmission lag). For Planet A, that's Day 0 to Day 202; for Planet B, that's Day 100 to Day 102.

- Does that help? — Lomn 18:35, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The ship takes 101 days (not 102) to reach planet B from the point of view of either planet.

- Calculating the -factor:

- The trip takes from the point of view of the ship. Dauto (talk) 18:39, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Hmm... both these response have just made me more confused. Lomn's response doesn't seem right, because if B tracked the ship from its departure, it would see the ship travelling 100 lightdays' distance in two days, which is faster than c, and thus impossible.

- Dauto's response confuses me, because it seems the ship would observe itself as approaching B faster than c as well. --Goodbye Galaxy (talk) 19:01, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The ship sees itself approaching B at 0.99c. That only takes about 14 days because from the point of view of the ship the distance between the planets is Lorentz contracted to about 14 light-days. Lomn is also right because even though the trip takes 100 days from B's point of view, he sees it happening over only 1 day because of Doppler effect. Dauto (talk) 19:06, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- To be clear, how long the trip takes from B's point of view, and how long it takes him to observe the trip are different because of time delays due to the finite speed of light (B uses light to observe the trip). Dauto (talk) 19:10, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- Ah, of course. I forgot that distances are relative as well. I'm still slightly confused about Planet B's point of view. I guess I've been operating under the assumption that no object can even appear to move faster than c, but... I was wrong? (p.s. science is awesome, and thanks for your answers, guys) --Goodbye Galaxy (talk) 19:20, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- See also superluminal jet, a real-world example. Wnt (talk) 19:31, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- From the perspective of the "moving" observer, there's a cute unit, the "roddenberry", describing how fast it looks like you're going - alas, we don't have an article on it! Wnt (talk) 19:34, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The observers on Planet B know the speed of light and will allow for it. Therefore, then they see the ship leave Planet A, they'll know that it actually left 100 days ago. Therefore, when the ship arrives a day later, they know the trip took 101 days (the people on the ship will disagree, of course). --Tango (talk) 12:13, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

Weak Interaction - article

Hi, reading the weak interaction article, I have remained with some question ? In quantum physics we have learned that always we have two or more particles with electric charge, they interact exchanging photons and so we have electromagnetic force among them. Also, always we have particles very close, in distances lower to proton diameter, we have strong force interacting based in echanging of gluons among quarks. But I have learned in the article that all fundamental particles have weak isospin that acts as electric charge. So I have two questions: 1. - Do quarks exchange bosons (W+, W-, Z) all the time ? and , or 2. - What conditions cause a down quark decay to up quark since we can´t predict this phenomenon ?

Thanks for all, and my comment is based on fact that it is very difficult to get good explanation about weak interaction for begginers. This article can helps a lot. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Futurengineer (talk • contribs) 17:19, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- 1. Yes, quarks do exchange virtual (W+, W-, Z) all the time.

- 2. The decay is completely random. no special condition is required.

- Dauto (talk) 18:29, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- You may also be interested in strangeness and charm. ~AH1 (discuss!) 15:54, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

Orbits after central mass changes

Can't quite figure out how to approach this. Some satellites are in circular orbits around the Earth. Suddenly the mass of the Earth doubles. What happens to the orbits of the satellites? Twang (talk) 19:07, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- It becomes elliptic with the satellite at the apogee. Dauto (talk) 19:15, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- We could also be more rigorous in defining the behavior if you can elaborate on the meaning of "suddenly." Even if the change is (theoretically) instantaneous, the branch of classical mechanics called continuum mechanics elucidates the mathematical procedures you would need to use to model an instantaneous change of mass, based on where the mass came from and how it distributed itself. I'm thinking about an "accretion process" where the mass accretes on a time-scale much faster than the orbital time-scale. Gauss's law for gravity may also help you identify the conceptual behavior for this thought experiment. Nimur (talk) 20:09, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Let's try simpler: Given a planet with mass M, and a satellite in circular orbit with radius r. How to find r for a satellite with the same kinetic energy orbiting a planet with mass 2M. (Actually matter accretion is what got me thinking about it, but not trying to build a computer model, just trying to get a handle on what's involved ... I don't really grok orbital mechanics.)Twang (talk) 22:14, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- If I recall correctly, a satellite in circular orbit has one-half the kinetic energy it needs to achieve escape velocity, i.e. to reach zero gravitational potential energy. Gravitational potential energy is negative and proportional to m1m2/r. Since the kinetic energy remains the same, the gravitational potential energy needs to be the same, which means if you double m2 you need to double r. So if you double the planet's mass, the satellite needs to be twice as far out to orbit at the same leisurely speed as before. To put this another way, the orbital period of a satellite with a given semi-major axis will decrease according to the square root of the central mass. Wnt (talk) 22:49, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- That's a helpful thought. This page [9] on Earth-orbit velocity shows that the orbital velocity decreases with increasing radius. But then, the centripetal force law [10] is Fc=mv^2/r, so if Fc doubles, either r is halved, or v increases by 1.414 ... probably some combination of the two... which is Dauto's line. Imagine a weight twirled in a circle at the end of a rubber band; if the elasticity of the band suddenly increases, the weight's "orbit" would be elongated, and probably precesses depending (as Nimur suggests) on what "sudden" means. I'll hit the books - thanks folks.Twang (talk) 05:03, 9 July 2011 (UTC)

Why do so many adult males like my little pony?

Question moved to Wikipedia:Reference desk/Entertainment

Genetics of garden flower colours

Some garden flower species can have a variety of different coloured flowers. I have some Hollyhocks, Alcea rosea, in my garden with each plant having flowers of a particular colour. What are the chances of their seeds producing plants with flowers the same colour? Is anything known about the dominance or recessiveness of the genes for flower colour? 92.28.254.38 (talk) 21:00, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think you'll find as much variety in flower color genetics as in any other area of genetics. So, if you have parents of two different colors, you may have a strict dominant-recessive relationship, where 3/4 of offsprings' flowers are the dominant color and 1/4 are the recessive, or some other ratio, if it's a multi-gene interaction, or perhaps you'll get a blended or variegated variety where there isn't a dominance-recessive relationship. StuRat (talk) 21:22, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

Question about the sun

It's acknowledged that a human couldn't survive long on the Sun not to mention Earth itself. My question is since Jupiter and Saturn are bigger than any of the other planets in our solar system, if the Sun were to consume Jupiter and Saturn, how long would it take for the sun's heat to vanquish the two planets? My question applies to both if the sun were to swallow them at the same time or subsequently, by the way. SwisterTwister talk 23:08, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- As our Roche limit article explains (although not very understandably), a planet such as Jupiter or Saturn could not even reach the Sun before being torn apart by tidal forces -- so they would be "vanquished" before they even got to the heat. Looie496 (talk) 23:18, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'll explain if the article is insufficient: basically, we know that the closer an object is to the Sun, the faster it completes one revolution around the Sun. This is due to the stronger pull of gravity the closer you get to the Sun. Therefore, if you think about a planet as a 3-d sphere instead of a point mass, you will realize that the point closest to the Sun on a planet will be pulled slightly harder than a point on the far side, leading to internal stresses within the planet. Now, for a faraway and small planet like Earth, the stress is not nearly enough to overcome the gravitational pull holding the Earth together. However, as you get closer and closer to a heavy body (like the Sun in this example), the gravitational force is increasing more and more rapidly, and the difference in forces between the near and far side of the planet get greater and greater. At some point, the difference in gravitational force will be too much for the planet to bear, and it will break apart into smaller pieces. The point at which this happens is called the Roche limit.

- See, astrophysics doesn't have to be scary! -RunningOnBrains(talk) 23:26, 7 July 2011 (UTC)

- The Roche limit varies as a function of density and as the lighter outer layers of the planets are removed the average density of the planet would increase eventually becoming high enough to stop the disintegration (That would only be true for the rocky core likely present at the center of those planets). Dauto (talk) 02:01, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- But suppose you used duct tape to secure all the surface of the planet before you sent it towards the Sun? Myles325a (talk) 06:38, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- The Roche limit varies as a function of density and as the lighter outer layers of the planets are removed the average density of the planet would increase eventually becoming high enough to stop the disintegration (That would only be true for the rocky core likely present at the center of those planets). Dauto (talk) 02:01, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Even if Jupiter and Saturn had a surface, duct tape would have a negligible effect compared to the gravitational forces involved. There are some things that even duct tape cannot fix.--Shantavira|feed me 07:28, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- What if the duct tape is made of Quarkium? (See a section farther up the page). As regards the concept of duct-taping Jupiter and Saturn, that's a funny mental picture. Where's Red Green when you need him? :) ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 08:29, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, if you used quarkium duct tape, then the tape might not fail, but the glue still would. Googlemeister (talk) 15:46, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Some simulations suggest that the Sun's final transition to planetary nebula will blow off the outer gaseous atmosphere of Jupiter and Saturn, although Saturn's rings may have collapsed by then. ~AH1 (discuss!) 15:47, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, if you used quarkium duct tape, then the tape might not fail, but the glue still would. Googlemeister (talk) 15:46, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- What if the duct tape is made of Quarkium? (See a section farther up the page). As regards the concept of duct-taping Jupiter and Saturn, that's a funny mental picture. Where's Red Green when you need him? :) ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 08:29, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Even if Jupiter and Saturn had a surface, duct tape would have a negligible effect compared to the gravitational forces involved. There are some things that even duct tape cannot fix.--Shantavira|feed me 07:28, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

July 8

Climate in Kuwait

I have a friend living in Kuwait City, which is currently experiencing temperatures bordering on 50 degrees celsius. Where does this place rank globally in terms of summertime maximum and average temperatures? I've never heard of a place this hot. Thanks. 49.185.136.107 (talk) 03:04, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- It ranks pretty high, but there are many spots in that region that frequently reach similar temperatures in midsummer. The average temperatures are actually a lot lower, because the dryness and lack of vegetation produce a lot of cooling during the night. For what it's worth, the hottest place on Earth, in terms of average temperature, is said to be the Afar Depression in Ethiopa -- not all that far away from Kuwait. Looie496 (talk) 03:29, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- See Climate of Kuwait. The hottest recorded temperature in Kuwait was 52.6°C in Abdaly, on June 15, 2010[11]. ~AH1 (discuss!) 15:44, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

Nuclear reticulum

Is nuclear reticulum same as Nuclear lamina? --111Engo (talk) 04:07, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- No, the nuclear lamina is the meshwork of proteins adjacent the phospholipd nuclear membrane. The nuclear reticulum is a term used to refer to a network like pattern seen in the nucleus. Depending on the context it may be the

- the pattern of chromatin when it is stained

- the distribution of ribonucleoproteins seen by immunostaining .

- the tubules and vesicles formed by the nuclear membrane protruding into the centre of the nucleus.(think of this as an endoplasmic reticulum) in the nucleus.

(maybe the nuclear architecture article needs updating?)Staticd (talk) 07:57, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

Hello, a question about the article "Wilson's disease"

it says (in the part; "nutrition"); "In general, a diet low in copper-containing foods is recommended, with the avoidance of mushrooms, nuts, chocolate, dried fruit, liver, and shellfish".[1]

my Q;

Nuts, what kind of nuts?, and also, organic for example also contain copper?.

and mushrooms, what kind?.

BTW, is it true that some plants organically contain copper? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 79.182.28.217 (talk) 07:31, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- All plants contain copper as it is part of many essential enzymes. However the levels vary depending on the species, the part and how it was grown. Regarding what foods to avoid, that would be medical advice, you would have to ask a doctor. It's taboo to offer it here. :). Staticd (talk) 08:01, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- It's a little bit late telling the OP we can't help with dietary recommendations, when those he listed above came straight from Wikipedia anyway. Even the title of this section says the question is about the Wilson's disease article just as much as the disease itself. And that list of foods to avoid IS questionable, including, as it does, nuts. That's such a catch-all category of foods in English. It includes things as diverse as peanuts, pistachios, walnuts and macadamias. To assign a common characteristic to them all is not very scientific. Given what the OP has already garnered from Wikipedia, I think anyone who can is almost obliged to help clarify further. HiLo48 (talk) 09:07, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- The book Wilson's disease: a clinician's guide to recognition, diagnosis, and management, (from 2001 though) suggests that diet isn't important apart from liver and shellfish which can be significantly high in copper. See page 73. Sean.hoyland - talk 10:25, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

Electric Power

IN DIRECT CURRENT,flow of electron is continues i.e.,from negative terminal to positive terminal.but in ALTERNATING CURRENT, electron moves forward and again backward but does not move from negative terminal to the positive terminal so that only current wave travel like when we throw a stone in a river then wave only travels not the water particle. is it true or not. PLEASE GIVE ME BRIEF DETAIL ABOUT ELECTRON FLOW IN A.Cvsnkumar (talk) 12:20, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Have a look at Alternating current and Wave. Dolphin (t) 12:44, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- You seem to have the right idea. For both AC and DC, it is the movement of the charges ("current") that matters, not where they end up. In AC, electrons move into the terminals and out of them again. The electrons do work on the load both when they move in and when they move out. --Srleffler (talk) 17:31, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

Electric power2

I put a Electric tester in a socket's neutral,it shows zero voltage.we know that Alternating current is a sinusoidal.i.e.,for positive cycle it travels in one direction and for negative half cycle it travel in opposite direction.according to this,is phase and neutral reverses for every cycle in a socket or not? if not how electrons flow in a conductor for A.C. Also in d.c, please give me brief detail about electron flow in a.c according to my questionvsnkumar (talk) 12:23, 8 July 2011 (UTC)

- Have a look at Alternating current. Dolphin (t) 12:46, 8 July 2011 (UTC)