The Piano: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v2.0beta10) (Smasongarrison) |

→External links: Information about different movie Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 418: | Line 418: | ||

{{wikiquote}} |

{{wikiquote}} |

||

* {{IMDb title|0107822|The Piano}} |

* {{IMDb title|0107822|The Piano}} |

||

* [https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0253474/awards The Pianist (2002) - Awards] |

|||

* {{tcmdb title|86647|The Piano}} |

* {{tcmdb title|86647|The Piano}} |

||

* {{mojo title|piano|The Piano}} |

* {{mojo title|piano|The Piano}} |

||

Revision as of 17:22, 30 December 2018

| The Piano | |

|---|---|

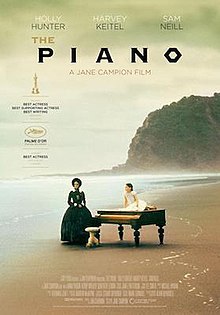

US theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jane Campion |

| Written by | Jane Campion |

| Produced by | Jan Chapman |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Stuart Dryburgh |

| Edited by | Veronika Jenet |

| Music by | Michael Nyman |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Bac Films (France) Miramax Films (US) Entertainment Film Distributors (UK) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 117 minutes |

| Countries | New Zealand Australia France |

| Languages | English Māori British Sign Language |

| Budget | US$7 million[1] |

| Box office | US$140 million[2] |

The Piano is a 1993 New Zealand drama film about a mute piano player and her daughter, set during the mid-19th century in a rainy, muddy frontier backwater town on the west coast of New Zealand. It revolves around the musician's passion for playing the piano and her efforts to regain her piano after it is sold. The Piano was written and directed by Jane Campion and stars Holly Hunter, Harvey Keitel, Sam Neill, and Anna Paquin in her first acting role. The film's score by Michael Nyman became a best-selling soundtrack album, and Hunter played her own piano pieces for the film. She also served as sign language teacher for Paquin, earning three screen credits. The film is an international co-production by Australian producer Jan Chapman with the French company Ciby 2000.

The Piano was a success both critically and commercially, grossing US$140 million worldwide against its US$7 million budget. Hunter and Paquin both received high praise for their respective roles as Ada and Flora McGrath. In 1993, the film won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It won three Academy Awards out of eight total nominations in March 1994: Best Actress for Hunter, Best Supporting Actress for Paquin, and Best Original Screenplay for Campion. Paquin was 11 years old at the time and is the second youngest actor to win an Oscar in a competitive category.

Plot

A mute Scotswoman named Ada McGrath is sold by her father into marriage to a New Zealand frontiersman named Alisdair Stewart, bringing her young daughter Flora with her. Ada has not spoken a word since she was six and no one, including herself, knows why. She expresses herself through her piano playing and through sign language, for which her daughter has served as the interpreter. Flora, it is later learned, is the product of a relationship with a teacher with whom Ada believed she could communicate through her mind, but who "became frightened and stopped listening", and thus left her.

Ada, Flora, and their belongings, including a hand crafted piano, are deposited on a New Zealand beach by a ship's crew. The following day, Alisdair arrives with a Māori crew and his white friend, Baines, a fellow forester and retired sailor who has adopted many of the Maori customs, including tattooing his face. Alisdair tells Ada that there is no room in his small house for the piano and abandons the piano on the beach. Ada, in turn, is cold to him and is determined to be reunited with her piano. Unable to communicate with Alisdair, Ada and Flora visit Baines with a note asking to be taken to the piano. He explains that he cannot read. Baines soon suggests that Alisdair trade the instrument to him for some land. Alisdair consents, and agrees to his further request to receive lessons from Ada, oblivious to his attraction to her. Ada is enraged when she learns that Alisdair has traded away her precious piano without consulting her. During one visit, Baines proposes that Ada can earn her piano back at a rate of one piano key per "lesson", provided that he can observe her and do "things he likes" while she plays. She agrees, but negotiates for a number of lessons equal to the number of black keys only. While Ada and her husband Alisdair have had no sexual, nor even mildly affectionate, interaction, the lessons with Baines become a slow seduction for her affection. Baines requests gradually increased intimacy in exchange for greater numbers of keys. Ada reluctantly accepts but does not give herself to him the way he desires. Realizing that she only does what she has to in order to regain the piano, and that she has no romantic feelings for him, Baines gives up and simply returns the piano to Ada, saying that their arrangement "is making you a whore, and me wretched", and that what he really wants is for her to actually care for him.

Despite Ada having her piano back, she ultimately finds herself missing Baines watching her as she plays. She returns to him one afternoon, where they submit to their desire for one another. Alisdair, having become suspicious of their relationship, hears them having sex as he walks by Baines' house, and then watches them through a crack in the wall. Outraged, he follows her the next day and confronts her in the forest, where he attempts to force himself on her, despite her intense resistance. He eventually exacts a promise from Ada that she will not see Baines.

Soon afterwards, Ada sends her daughter with a package for Baines, containing a single piano key with an inscribed love declaration reading "Dear George you have my heart Ada McGrath". Flora does not want to deliver the package and brings the piano key instead to Alisdair. After reading the love note burnt onto the piano key, Alisdair furiously returns home with an ax and cuts off Ada's index finger to deprive her of the ability to play the piano. He then sends Flora who witnessed this to Baines with the severed finger wrapped in cloth, with the message that if Baines ever attempts to see Ada again, he will chop off more fingers. Later that night, while touching Ada in her sleep, Alisdair hears what he believes to be Ada's voice inside of his head, asking him to let Baines take her away. Deeply shaken, he goes to Baines' house and asks if she has ever spoken words to him. Baines assures him she has not. Ultimately, it is assumed that he decides to send Ada and Flora away with Baines and dissolve their marriage once she has recovered from her injuries. They depart from the same beach on which she first landed in New Zealand. While being rowed to the ship with her baggage and Ada's piano tied onto a Māori longboat, Ada asks Baines to throw the piano overboard. As it sinks, she deliberately tangles her foot in the rope trailing after it. She is pulled overboard but, deep under water, changes her mind and kicks free and is pulled to safety.

In an epilogue, Ada describes her new life with Baines and Flora in Nelson, where she has started to give piano lessons in their new home, and her severed finger has been replaced with a silver finger made by Baines. Ada has also started to take speech lessons in order to learn how to speak again.

Cast

- Holly Hunter as Ada McGrath

- Harvey Keitel as George Baines

- Sam Neill as Alisdair Stewart

- Anna Paquin as Flora McGrath

- Kerry Walker as Aunt Morag

- Genevieve Lemon as Nessie

- Tungia Baker as Hira

- Ian Mune as Reverend

- Peter Dennett as Head seaman

- Cliff Curtis as Mana

- George Boyle as Ada's father

- Rose McIver as Angel

Production

Casting the role of Ada was a difficult process. Sigourney Weaver was Campion's first choice, but she turned down the role because she was taking a break from film at the time. Jennifer Jason Leigh was also considered, but she could not meet with Campion to read the script because she was committed to shooting the film Rush (1991).[3] Isabelle Huppert met with Jane Campion and had vintage period-style photographs taken of her as Ada, and later said she regretted not fighting for the role as Hunter did.[4]

The casting for Flora occurred after Hunter had been selected for the part. They did a series of open auditions for girls age 9 to 13, focusing on girls who were small enough to be believable as Ada's daughter (as Holly Hunter is relatively short at 157 cm / 5' 2" tall[5]). Anna Paquin ended up winning the role of Flora over 5,000 other girls.[6]

Alistair Fox has argued that The Piano was significantly influenced by Jane Mander's The Story of a New Zealand River.[7] Robert Macklin, an associate editor with The Canberra Times newspaper, has also written about the similarities.[8] The film also serves as a retelling of the fairytale "Bluebeard",[9][10] which is hinted at further in the inclusion of "Bluebeard" as a piece of the Christmas pageant.

In July 2013, Campion revealed that she originally intended for the main character to drown in the sea after going overboard after her piano.[11]

Production on the film started in April 1992, filming began on 11 May 1992 and lasted until July 1992, and production officially ended on 22 December 1992.[12]

Reception

Reviews for the film were overwhelmingly positive. Roger Ebert wrote: "The Piano is as peculiar and haunting as any film I've seen" and "It is one of those rare movies that is not just about a story, or some characters, but about a whole universe of feeling".[13] Hal Hinson of The Washington Post called it "[An] evocative, powerful, extraordinarily beautiful film".[14]

In his 2013 Movie Guide, Leonard Maltin gave the film 3 1/2 stars out of 4, calling the film a "Haunting, unpredictable tale of love and sex told from a woman's point of view" and went on to say "Writer-director Campion has fashioned a highly original fable, showing the tragedy and triumph erotic passion can bring to one's daily life".[15]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 92% based on 59 reviews, and an average rating of 8.2/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Powered by Holly Hunter's main performance, The Piano is a truth-seeking romance played in the key of erotic passion."[16] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 89 out of 100, based on 20 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[17]

Accolades

At the 1993 Cannes Film Festival, the film shared the Palme d'Or, with Chen Kaige's Farewell My Concubine, with Campion becoming the first woman to win the honour.[18] Aside from being the first woman to win the highest Cannes honour, she was the first filmmaker from New Zealand to achieve this.[19] Holly Hunter also received the Best Actress Award.[20] In 1994, the film won three Academy Awards: Best Actress (Holly Hunter), Best Supporting Actress (Anna Paquin) and Best Original Screenplay (Jane Campion). Anna Paquin was the second youngest person (after Tatum O'Neal) to win an Academy Award.[21]

Soundtrack

The score for the film was written by Michael Nyman, and included the acclaimed piece "The Heart Asks Pleasure First"; additional pieces were "Big My Secret", "The Mood That Passes Through You", "Silver Fingered Fling", "Deep Sleep Playing" and "The Attraction of the Peddling Ankle". This album is rated in the top 100 soundtrack albums of all time and Nyman's work is regarded as a key voice in the film, which has a mute lead character.[36]

Home media

The film was released on DVD in 1997 by LIVE Entertainment and on Blu-ray on 31 January 2012 by Lionsgate, but already released in 2010 in Australia.[37]

References

- ^ Box Office Information for The Piano. Archived 11 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine The Wrap. Retrieved 4 April 2013

- ^ Margolis, H. (2000). Jane Campion's The Piano. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 9780521597210. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "A Pinewood Dialogue With Jennifer Jason Leigh" (PDF). Museum of the Moving Image. 23 November 1994.

- ^ "Isabelle Huppert: La Vie Pour Jouer – Career/Trivia". Archived from the original on 16 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Denise Worrell (21 December 1987). "Show Business: Holly Hunter Takes Hollywood". time.com. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ Andrew Fish (Summer 2010). "It's in Her Blood: From Child Prodigy to Supernatural Heroine, Anna Paquin Has Us Under Her Spell". Venice Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Alistair Fox. "Puritanism and the Erotics of Transgression: the New Zealand Influence on Jane Campion's Thematic Imaginary". Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Macklin, Robert (September 2000). "FIELD NOTES: The Purloined Piano?". lingua franca. Vol. 10, no. 6.

- ^ Heidi Ann Heiner. "Modern Interpretations of Bluebeard". Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Scott C. Smith. "Look at The Piano". Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Child, Ben (8 July 2013). "Jane Campion wanted a bleaker ending for The Piano". The Guardian.

- ^ "The Piano (1993) – Box office / business". IMDb.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (19 November 1993). "THE PIANO". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (19 November 1993). "'The Piano' (R)". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard. 2013 Movie Guide. Penguin Books. p. 1084. ISBN 978-0-451-23774-3.

- ^ "The Piano (1993)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "The Piano Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Dowd, AA (13 February 2014). "1993 is the first and last time the Palme went to a woman". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Margolis, Harriet (2000). "Introduction". Jane Campion's The Piano. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0521597218.

- ^ a b "THE PIANO". Cannes Film Festival. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Young, John (24 December 2008). "Anna Paquin: Did she really deserve an Oscar?". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "1993 Winners & Nominees". Australian Film Institute. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "The 66th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Film in 1994". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Past Award Winners". Boston Society of Film Critics. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Williams, Michael (27 February 1994). "Resnais' 'Smoking' duo dominates Cesar prizes". Variety. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Terry, Clifford (8 February 1994). "Spielberg, `List' Win In Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Piano, The". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "The Piano (1993)". Swedish Film Institute. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ a b Wiener, Tom (2002). "The Piano". The Off-Hollywood Film Guide: The Definitive Guide to Independent and Foreign Films on Video and DVD. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 0679647376.

- ^ "AWARD: FILM OF THE YEAR". London Film Critics' Circle. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "19TH ANNUAL LOS ANGELES FILM CRITICS ASSOCIATION AWARDS". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "1993 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Fox, David J. (14 March 1994). "'Schindler's' Adds a Pair to the List : Awards: Spielberg epic takes more honors--for screenwriting and editing. Jane Campion's 'The Piano' also wins". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Entertainment Weekly, 12 October 2001, p. 44

- ^ Piano [Blu-ray] (1993)

External links

- Use dmy dates from May 2011

- 1993 films

- 1990s romantic drama films

- Adultery in films

- Australian films

- Australian romantic drama films

- French films

- French romantic drama films

- New Zealand drama films

- New Zealand romance films

- New Zealand films

- English-language films

- Māori-language films

- British Sign Language films

- Films directed by Jane Campion

- Best Foreign Film César Award winners

- Feminist films

- Films featuring a Best Actress Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Drama Actress Golden Globe-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award-winning performance

- Films set in New Zealand

- Films set in the 1850s

- Films set in the British Empire

- Films about pianos and pianists

- Films shot in New Zealand

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Historical romance films

- New Zealand independent films

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Foreign Film winners

- Best Foreign Film Guldbagge Award winners

- Palme d'Or winners

- Romantic period films

- Ciby 2000 films

- Australian historical films

- New Zealand historical films

- Australian independent films

- French historical films

- French independent films

- Films scored by Michael Nyman