Timeline of extinctions in the Holocene

This article is a list of biological species and subspecies that are known to have become extinct during the Holocene, the current geologic epoch, ordered by their known or approximate date of disappearance from oldest to most recent.

The Holocene is considered to have started with the Holocene glacial retreat around 11650 years Before Present (c. 9700 Before Common Era). It is characterized by a general trend towards global warming, the expansion of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) to all emerged land masses, the appearance of agriculture and animal husbandry, and a reduction in global biodiversity. The latter, dubbed the sixth mass extinction in Earth history, is largely attributed to increased human population and activity, and may have started already during the preceding Pleistocene epoch with the demise of the Pleistocene megafauna.

The following list is incomplete by necessity, since the majority of extinctions are thought to be undocumented, and for many others there isn't a definitive, widely accepted last, or most recent record. According to the species-area theory, the present rate of extinction may be up to 140,000 species per year.[1]

10th millennium BCE

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highland gomphothere | Cuvieronius hyodon | Northern and central Andes[2] | 9790 BCE | Hunting?[3] |

| Macrauchenia | Macrauchenia patachonica | Southwestern South America | 9730-5320 BCE | Hunting.[4] |

| Patagonian panther | Panthera onca mesembrina | Patagonia | 9705-9545 | Undetermined.[5] |

| Toronto subway deer | Torontoceros hypnogeos | Toronto, Canada | 9690-9040 BCE | Undetermined.[6] |

| Western bison | Bison occidentalis | North America; Eastern Siberia and Japan? | 9590-9250 BCE[6] | Possibly hybridization with ancient bison resulting in modern American bison.[7] |

| Dwarf pronghorn | Capromeryx minor | Western United States and northern Mexico | 9580-8860 BCE | Undetermined.[8] |

| Chinese cave hyena | Crocuta crocuta ultima | East Asia | 9550 BCE (confirmed) 5850 BCE (unconfirmed) |

Undetermined.[9] |

| Shrub-ox | Euceratherium collinum | Southwestern North America | 9550 BCE | Undetermined.[10] |

| American mountain deer | Odocoileus lucasi | Rocky Mountains | 9550 BCE | Hunting?[11] |

| Stock's pronghorn | Stockoceros sp. | Mexico and Southwestern United States | 9550 BCE | Hunting?[11] |

| Sardinian dhole | Cynotherium sardous | Corsica and Sardinia | 9500-9300 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Long-nosed peccary | Mylohyus nasutus | Eastern United States | 9350 BCE 9050-7550 BCE (dubious)[13] |

Habitat loss and competition with the American black bear.[11] |

| Scelidothere | Scelidotherium sp. | Southern South America | 9280-8900 BCE | Hunting?[11] |

| Jefferson's ground sloth | Megalonyx jeffersonii | North America | 9190-8870 BCE | Undetermined.[11] |

| Flat-headed peccary | Platygonus compressus | North America | 9170-9050 BCE[5] | Possibly vegetation changes induced by climate change and competition with the American black bear.[11] |

| Pygmy mammoth | Mammuthus exilis | Channel Islands of California, United States | 9130-9030 BCE | Undetermined.[5] |

| Asphalt stork | Ciconia maltha | Americas | 9050-8050 BCE | Undetermined.[14] |

| Merriam's teratorn | Teratornis merriami | California, United States | 9050-8050 BCE | Undetermined.[14] |

9th millennium BCE

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North American short-faced bear | Arctodus simus | North America | 8995-8845 BCE[5] | Competition with the grizzly bear.[11] |

| Mexican horse | Equus conversidens | North America | 8965-8875 BCE[5] 7250-6750 BCE (dubious)[15] |

Hunting.[5] |

| Giant beaver | Castoroides ohiensis | North America | 8960-8840 BCE | Undetermined.[5] |

| Schneider's duck | Anas schneideri | Converse County, Wyoming, United States | 8800-8300 BCE | Undetermined.[14] |

| Large-billed blackbird | Euphagus magnirostris | North America | 8800-8300 BCE | Undetermined.[14] |

| American lion | Panthera atrox | North America; Western South America? |

8580-8260 BCE | Undetermined.[7] |

| Yukon horse | Equus lambei | Eastern Beringia | 8550 BCE | Undetermined.[16] |

| Argentinian short-faced bear | Arctotherium tarijense | Argentina[17] | 8470-8320 BCE | Undetermined.[5] |

| Stag-moose | Cervalces scotti | Eastern United States | 8430-8130 BCE | Undetermined.[7] |

| Woodland muskox | Bootherium bombifrons | North America | 8420 BCE | Undetermined.[8] |

| Shasta ground sloth | Nothrotheriops shastensis | Southwestern United States | 8350-7550 BCE[7] | Hunting.[18] |

| Giant Cape zebra | Equus capensis | Southern Africa | 8340-3950 BCE | Reduction of grasslands after the end of the Last Glacial Period.[19] |

| Giant pika | Ochotona whartoni | Northern North America; Eastern Siberia? |

8301-7190 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Vero tapir | Tapirus veroensis | Southern United States | 8200-7660 BCE[7] | Hunting.[11] |

| Harrington's mountain goat | Oreamnos harringtoni | Southern Rocky Mountains | 8100 BCE[7] | Hunting.[18] |

| Little South American horse | Hippidion saldiasi[20] | Eastern South America[21] | 8059 BCE[22] | Hunting.[4] |

| South American palmate-antlered deer | Morenelaphus brachyceros | Temperate South America | 8050-5845 BCE | Undetermined.[23] |

8th millennium BCE

-

Tracing of paleo-American petroglyphs depicting two Columbian mammoths and an ancient bison.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North American pampathere | Holmesina septentrionalis | Southeastern United States | 7930 BCE | Undetermined.[11] |

| Catonyx | Catonyx cuvieri | Eastern South America | 7830-7430 BCE | Undetermined.[5][12] |

| Panamerican ground sloth | Eremotherium laurillardi[24] | Southern United States to Brazil | 7800-7740 BCE | Undetermined.[25] |

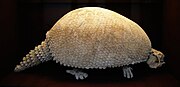

| Pampean giant armadillo | Eutatus seguini | Northern Argentina and Uruguay[26] | 7775-5845 BCE | Undetermined.[23] |

| North American sabertooth | Smilodon fatalis | Southern North America and northern South America | 7615-7305 BCE | Prey loss.[11] |

| South American sabertooth | Smilodon populator | Eastern South America | 7330-7030 BCE[12] | Competition with human hunters.[4] |

| American camel | Camelops hesternus | Western North America | 7250-5330 BCE | Hunting.[11] |

| Scott's horse | Equus scotti | Western North America | 7250-6750 BCE (dubious)[15] 900-720 BCE (dubious)[6] |

Hunting? |

| Chilean scelidodont | Scelidodon chiliensis | Western South America[27] | 7160-6760 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Columbian mammoth | Mammuthus columbi | Northern Mexico, western and southern United States | 7100-6300 BCE[6] 3095-2775 BCE (dubious) |

Hunting.[11] |

| Giant ghost-faced bat | Mormoops magna | Cuba | 7043-6503 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Greater Cuban nesophontes | Nesophontes major | Cuba | 7043-6507 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Cuban pauraque | Siphonorhis daiquiri | Cuba | 7043-6507 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

7th millennium BCE

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-legged llama | Hemiauchenia macrocephala | North and Central America | 6833-6321 BCE | Hunting.[11] |

| Glossothere | Glossotherium sp. | South America | 6810-6650 BCE[12] | Hunting.[4] |

| Lowland gomphothere | Notiomastodon platensis | South America[2] | 6810-6650 BCE[12] | Hunting?[11] |

| Mylodont | Mylodon darwini | Pampas and Patagonia | 6689 BCE[11] | Hunting.[4] |

| Large South American horse | Equus neogeus | South America[28] | 6660-4880[12] | Hunting.[4] |

| Common glyptodont | Glyptodon sp. | Eastern South America | 6660-4880 BCE (confirmed)[12] 5850-4350 BCE (unconfirmed) 2350 BCE (dubious) |

Hunting.[4] |

| Brazilian glyptodont | Hoplophorus euphractus | Eastern Brazil | 6660-4880 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Stout-legged llama | Palaeolama mirifica | North, Central, and South America | 6660-4880 BCE[12] | Hunting.[4] |

| Eastern giant armadillo | Propraopus sulcatus | Eastern South America[29] | 6660-4880 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Giant hartebeest | Megalotragus priscus | Southern Africa; Eastern Africa? |

6130-3950 BCE | Reduction of grasslands after the end of the Last Glacial Period.[19] |

| Dire wolf | Aenocyon dirus | North America and western South America | 6050-5050 BCE[7] | Competition with the gray wolf.[11] |

| American mastodon | Mammut americanum | North America | 6050-5050 BCE[7] | Possibly habitat fragmentation as a result of climate change, and competition with the moose.[11] |

6th millennium BCE

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kambuaya's triok | Dactylopsila kambuayai | New Guinea | 5941-5596 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| New Guinea greater glider | Petauroides ayamaruensis | New Guinea | 5941-5596 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Bond's springbok | Antidorcas bondi | Southern Africa | 5740-5500 BCE | Reduction of grasslands after the end of the Last Glacial Period.[19] |

| Sardinian giant deer | Praemegaceros cazioti | Corsica and Sardinia[30] | 5550 BCE | Undetermined.[31] |

| Unnamed South African caprine | ?Makapania sp. | South African mountains | 5483-5221 BCE | Reduction of grasslands after the end of the Last Glacial Period.[19] |

| Ibiza rail | Rallus eivissensis | Ibiza, Spain | 5295-4848 BCE | Undetermined, but presumably a result of human colonization.[32] |

| Ancient bison | Bison antiquus | North America | 5271-5131 BCE[33] | Possibly hibridization with western bison resulting in modern American bison.[7] |

| Giant ground sloth | Megatherium americanum | Temperate South America and the Andes | 5270-4310 BCE[34] | Hunting.[4] |

5th millennium BCE

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irish elk | Megaloceros giganteus | Europe and southern Siberia | 4901-4831 BCE[35] 600-500 BCE (dubious) |

Reduction of grasslands after the end of the Last Glacial Period, and possibly hunting.[36] |

| North African horse | Equus algericus | Maghreb | 4855-4733 BCE | Aridification.[19] |

| Majorcan giant dormouse | Hypnomys morpheus | Mallorca, Spain | 4840-4690 BCE | Possibly disease spread by introduced rodents.[37] |

| Giant glyptodont | Doedicurus clavicaudatus | South American Pampas | 4765-4445 BCE 3023-2809 BCE (dubious)[38] |

Undetermined.[34] |

| Algerian giant deer | Megaceroides algericus | Northern Maghreb | 4691-4059 BCE | Possibly habitat fragmentation.[39] |

| Toxodont | Toxodon platensis | South America | 4650-1450 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| North African aurochs | Bos primigenius africanus | North Africa | c. 4000 BCE | Aridification. Domestic descendants survive in captivity.[19] |

| North African zebra | Equus mauritanicus | North Africa | c. 4000 BCE | Aridification.[19] |

4th millennium BCE

-

Tracing of a steppe bison painted in Altamira Cave.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steppe bison | Bison priscus | Northern Eurasia and North America | 6950-6870 BCE (Eurasia)[40] 3628-3377 BCE (America)[41] |

Hunting.[40] |

| Kauaʻi mole duck | Talpanas lippa | Kaua'i, Hawaii, United States | 3540-3355 BCE | Undetermined.[42] |

| Radofilao's sloth lemur | Babakotia radofilai | Northern coast of Madagascar | 3340-2890 BCE | Undetermined.[43] |

| Smaller Cuban ground sloth | Parocnus brownii | Cuba | 3290-2730 BCE[5] | Hunting.[44] |

| Giant long-horned buffalo | Pelorovis antiquus | North Africa; south, east, and central Africa (Pleistocene) | 3060-2470 BCE | Aridification and competition with domestic cattle for water and pastures.[12] |

| Tilos dwarf elephant | Palaeoloxodon tiliensis | Tilos, Greece | 3040-1840 BCE (confirmed) c. 1470-1445 BCE (unconfirmed) |

Undetermined.[45] |

| Balearic giant shrew | Nesiotites hidalgo | Gymnesian Islands, Spain | 3030-2690 BCE | Possibly disease spread by introduced rodents.[37] |

3rd millennium BCE

-

Representation of the Egyptian god Bennu, allegedly inspired by the Bennu heron.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balearic cave goat | Myotragus balearicus | Gymnesian Islands, Spain | 2830-2470 BCE | Likely vegetation changes related to aridification or human activity.[46][47] |

| Bennu heron | Ardea bennuides | Arabian Peninsula | 2550 BCE | Wetland degradation.[12] |

| Niue night heron | Nycticorax kalavikai | Niue | 2550-1550 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Hispaniola monkey | Antillothrix bernensis | Hispaniola | 2508-2116 BCE | Undetermined.[48] |

| Small Hispaniola ground sloth | Neocnus comes | Hispaniola | 2483-2399 BCE | Undetermined.[5] |

| New Caledonian giant megapode | Sylviornis neocaledoniae | Grande Terre and Isle of Pines, New Caledonia | 2457-1319 BCE (confirmed) 850 BCE (unconfirmed) |

Undetermined.[12] |

| Larger Cuban ground sloth | Megalocnus rodens | Cuba | 2280-2240 BCE | Undetermined.[49] |

| Chatham raven | Corvus moriorum | Chatham Islands, New Zealand | 2134-1408 BCE (confirmed) c. 1350 CE (unconfirmed) |

Undetermined.[12] |

2nd millennium BCE

-

Woolly mammoth cave art from Grotte de Rouff, depicting it alongside extant Alpine ibexes.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Caledonian terrestrial crocodile | Mekosuchus inexpectatus | New Caledonia and Isle of Pines | 1950-1050 BCE (confirmed) 140-180 CE (unconfirmed) |

Hunting.[50] |

| Indian aurochs | Bos primigenius namadicus | Indian Subcontinent | 1800 BCE | Undetermined. Domestic descendants survive in captivity and as feral populations.[51] |

| Woolly mammoth | Mammuthus primigenius | Northern Eurasia and North America | 7780-7660 BCE (Eurasia)[52] 6390-6270 BCE (America)[6] 3580-3480 BCE (Saint Paul)[53] 1795-1675 BCE (Wrangel)[52] |

Hunting.[54] |

| Chinese wild water buffalo | Bubalus mephistopheles | Lower Yellow River, China | 1750-1650 BCE | Undetermined.[55] |

| Puerto Rican ground sloth | Acratocnus odontrigonus | Puerto Rico | 1738-1500 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Christensen's pademelon | Thylogale christenseni | New Guinea | 1738-1385 BCE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Puerto Rican flower bat | Phyllonycteris major | Puerto Rico and Antigua | c. 1500 BCE | Undetermined.[56] |

| Leeward Islands curlytail | Leiocephalus cuneus | Antigua and Barbuda | c. 1500 BCE | Undetermined.[56] |

| European wild ass | Equus hydruntinus | Southern Europe and Southwest Asia; Northern Europe (Pleistocene) | 1294-1035 BCE (confirmed) 983 BCE - 635 CE (estimated) |

Hunting and habitat fragmentation after the end of the Last Glacial Period.[57] |

| Dune shearwater | Puffinus holeae | Canary Islands, Spain; mainland Portugal (Pleistocene) |

1159-790 BCE | Predation by introduced house mice.[58] |

| Vanuatu terrestrial crocodile | Mekosuchus kalpokasi | Efate, Vanuatu | 1050 BCE | Hunting.[50] |

| Vanuatu horned turtle | ?Meiolania damelipi | Vanuatu and Viti Levu, Fiji | 1050-550 BCE | Hunting.[59] |

1st millennium BCE

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balsam shrew | Crocidura balsamifera | Nile gallery forests, Egypt | 821-171 BCE | Habitat destruction.[12] |

| Eurasian muskox | Ovibos muschatus | Northern Eurasia | 820-680 BCE | Hunting.[40] The species is considered synonymous with the extant North American muskox (O. muschatus), only slightly larger.[60] North American animals have been successfully introduced to Eurasia during the 20th century.[61] |

| Syrian elephant | Elephas maximus asurus | Mesopotamia | 800-700 BCE | Hunting and habitat loss due to agriculture and aridification. However, it's been suggested that it was introduced by humans in the area, which would not make it a valid subspecies.[62] |

| MacPhee's shrew tenrec | Microgale macpheei | Southeastern Madagascar | 790-410 BCE | Aridification.[63] |

| Jamaican ibis | Xenicibis xympithecus | Jamaica | 787 BCE - 320 CE | Undetermined.[12] |

| Flightless sea duck | Chendytes lawi | Coastal California and Oregon, United States | 770-400 BCE | Hunting.[64] |

| Consumed scrubfowl | Megapodius alimentum | Tonga and Fiji | 760-660 BCE | Hunting.[65] |

| Large Tongan iguana | Brachylophus gibbonsi | Tonga | 650-570 BCE | Hunting.[65] |

| Plate-toothed giant hutia | Elasmodontomys obliquus | Puerto Rico | 511-407 BCE | Undetermined.[66] |

| Gorilla lemur | Archaeoindris fontoynontii | Central Madagascar | 412-199 BCE[43] | Hunting.[67] |

| Common koala lemur | Megaladapis madagascariensis | Madagascar | 370-40 BCE[43] | Hunting.[67] |

| Corsican giant shrew | Asoriculus corsicanus | Corsica, France | 348 BCE - 283 CE | Introduced black rats and human-induced habitat loss.[68] |

| Sardinian pika | Prolagus sardus | Corsica and Sardinia | 348 BCE - 283 CE (confirmed)[68] 1774 (unconfirmed) |

Hunting, predation and competition with introduced mammals.[69] |

| Hensel's field mouse | Rhagamys orthodon | Corsica and Sardinia | 348 BCE - 283 CE | Introduced black rats and human-induced habitat loss.[68] |

| Tyrrhenian vole | Tyrrhenicola henseli | Corsica and Sardinia | 348 BCE - 283 CE | Introduced black rats and human-induced habitat loss.[68] |

| Lena horse | Equus lenensis | Eastern Siberia[70] | 320-220 BCE | Hunting.[40] |

| Maui flightless ibis | Apteribis brevis | Maui, Hawaii, United States | 170 BCE - 370 CE | Undetermined.[71] |

| Ancient coua | Coua primaeva | Madagascar | 110 BCE - 130 CE | Undetermined.[43] |

| São Miguel scops owl | Otus frutuosoi | São Miguel Island, Azores, Portugal | 49 BCE - 125 CE | Introduced predators?[72] |

1st millennium CE

1st-5th century

-

Ancient coin from Cyrene depicting a silphium stalk.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silphium | ?Ferula sp. | Cyrenaica coast | 54-68 | Aridification, overgrazing, and overharvesting.[73] |

| Powerful goshawk | Accipiter efficax | New Caledonia | 86-428 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Gracile goshawk | Accipiter quartus | New Caledonia | 86-428 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Kanaka pigeon | Caloenas canacorum | New Caledonia and Tonga | 86-428 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Pile-builder megapode | Megapodius molistructor | New Caledonia and Tonga | 86-428 | Undetermined.[12] |

| New Caledonian gallinule | Porphyrio kukwiedei | New Caledonia | 86-428 (confirmed) 1860 (unconfirmed) |

Undetermined.[12] |

| Ball-headed sloth lemur | Mesopropithecus globiceps | Southwestern Madagascar | 245-429[43] | Hunting and aridification.[67] |

| Atlas wild ass | Equus africanus atlanticus | North Africa | c. 300 | Undetermined. Domestic descendants survive in captivity.[74] |

| New Ireland forest rat | Rattus sanila | New Ireland, Papua New Guinea | 347-535 | Undetermined.[12] |

| North African elephant | Loxodonta africana pharaoensis | Northwest Africa | 370[75] | Hunting and aridification.[76] |

| Southern Malagasy giant rat | Hypogeomys australis | Central and southern Madagascar | 428-618 | Undetermined.[43] |

| Jamaican monkey | Xenothrix mcgregori | Jamaica | 439-473 (confirmed) 1050 (estimated) |

Undetermined.[48] |

| Oʻahu moa-nalo | Thambetochen xanion | Oahu, Hawaii, United States | 440-639 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Large baboon lemur | Hadropithecus stenognathus | Central and southern Madagascar | 444-772[43] | Hunting and aridification.[67] |

| Chatham duck | Pachyanas chathamica | Chatham Islands, New Zealand | 448-657 (confirmed) c. 1350 (unconfirmed) |

Hunting?[12] |

| New Caledonian horned turtle | Meiolania mackayi | New Caledonia | c. 450 | Hunting.[77] |

6th-10th century

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuban spectacled owl | Pulsatrix arredondoi | Cuba | 530-590 | Undetermined.[78] |

| Malagasy shelduck | Alopochen sirabensis | Madagascar | 530-860 | Undetermined.[43] |

| Monkey-like sloth lemur | Mesopropithecus pithecoides | Central Madagascar | 570-679[43] | Hunting and aridification.[67] |

| Abrupt giant tortoise | Aldabrachelys abrupta | Madagascar | 580-1960[43] | Hunting and aridification.[67] |

| Forsyth Major's baboon lemur | Archaeolemur majori | Madagascar | 650-780[43] | Hunting and aridification.[67] |

| Lesser elephant bird | Mullerornis modestus | Central and southern Madagascar | 650-890[43] | Hunting and aridification.[67] |

| Small O'ahu crake | Porzana ziegleri | Oahu, Hawaii, United States | 650-869 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Cayman Islands geocapromys | Geocapromys caymanensis | Cayman Islands | 666-857 | Undetermined.[79] |

| Cayman Islands nesophontes | Nesophontes cingulus | Cayman Islands | 666-857 | Undetermined.[79] |

| Grandidier's giant tortoise | Aldabrachelys grandidieri | Madagascar | 670-890[43] | Hunting and aridification.[67] |

| Huahine starling | Aplonis diluvialis | Huahine, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 700-1150 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Huahine rail | Gallirallus storrsolsoni | Huahine, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 700-1150 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Huahine swamphen | Porphyrio mcnabi | Huahine, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 700-1150 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Southern giant ruffed lemur | Pachylemur insignis | Southwestern Madagascar | 715-985[43] | Hunting and aridification.[67] |

| Cuban cave rail | Nesotrochis picapicensis | Cuba | 760 | Undetermined.[78] |

| Insular cave rat | Heteropsomys insulans | Puerto Rico | 772-870 | Undetermined.[66] |

| Sinoto's lorikeet | Vini sinotoi | Marquesas and Society Islands, French Polynesia | 810-1025 | Hunting.[80] |

| Conquered lorikeet | Vini vidivici | Marquesas, Society, and Cook Islands | 810-1025 | Hunting.[80] |

| Malagasy aardvark | Plesiorycteropus madagascariensis | Central and southern Madagascar | 865-965 | Undetermined.[11] |

| Giant island deer mouse | Peromyscus nesodytes | Channel Islands of California, United States | 883-994 | Possibly habitat loss through overgrazing and erosion.[81] |

| Giant aye-aye | Daubentonia robusta | Southern Madagascar | 900-1150 | Hunting, expansion of grasses and deforestation caused by domestic cattle and goat grazing.[67] |

| Grandidier's koala lemur | Megaladapis grandidieri | Madagascar | 980-1170 | Hunting and vegetation changes caused by livestock.[67] |

2nd millennium CE

11th-12th century

-

A Malagasy pygmy hippopotamus skeleton compared to a common hippopotamus skull.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malagasy dwarf hippopotamus | Hippopotamus lemerlei | Southwestern Madagascar[82] | c. 1000[83] | Hunting, competition with, and changes to vegetation caused by livestock.[67] |

| Malagasy pygmy hippopotamus | Hippopotamus madagascariensis | Northwestern and central Madagascar[82] | c. 1000[84] | Hunting, competition with, and changes to vegetation caused by livestock.[67] |

| Puerto Rican nesophontes | Nesophontes edithae | Puerto Rico | 1015-1147 | Undetermined.[66] |

| Lava shearwater | Puffinus olsoni | Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, Canary Islands | 1020-1260 | Predation by introduced black rats and cats.[85] |

| Elephant bird | Aepyornis maximus | Southern Madagascar | 1040-1380 | Hunting, competition with, and changes to vegetation caused by livestock.[67] |

| Nēnē-nui | Branta hylobadistes | Oahu, Hawaii, United States | 1046-1380 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Edwards' baboon lemur | Archaeolemur edwardsi | Central Madagascar[86] | 1047-1280[43] | Hunting and changes to vegetation caused by livestock.[67] |

| Maui Nui moa-nalo | Thambetochen chauliodous | Molokai and Maui, Hawaii, United States | 1057-1375 | Undetermined.[12] |

| New Zealand swan | Cygnus sumnerensis | New Zealand and the Chatham Islands | 1059-1401 | Hunting.[12] |

| Tenerife giant rat | Canariomys bravoi | Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain | 1100-1300 | Hunting.[87] |

| Barbuda giant rice rat | Megalomys audreyae | Barbuda | 1173-1385 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Atalaye nesophontes | Nesophontes hypomicrus | Hispaniola | 1175-1295 | Undetermined.[88] |

| New Zealand owlet-nightjar | Aegotheles novaezealandiae | New Zealand | 1183 | Predation by introduced polynesian rats.[89] |

13th-14th century

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Michel nesophontes | Nesophontes paramicrus | Hispaniola | 1265-1400 | Undetermined.[88] |

| Lava mouse | Malpaisomys insularis | Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, Canary Islands | 1270 | Possibly disease spread by introduced rats.[90] |

| Mantell's moa | Pachyornis geranoides | North Island, New Zealand | 1278-1415 | Hunting.[12] |

| North Island giant moa | Dinornis novaezelandiae | North Island, New Zealand | 1286-1390 | Hunting.[91] |

| Heavy-footed moa | Pachyornis elephantopus | Eastern South Island, New Zealand | 1294-1438 | Hunting.[92] |

| Western Cuban nesophontes | Nesophontes micrus | Cuba | 1295-1430 | Undetermined.[88] |

| Haitian nesophontes | Nesophontes zamicrus | Hispaniola | 1295-1430 | Undetermined.[12] |

| Upland moa | Megalapteryx didinus | South Island, New Zealand | 1300-1422 | Hunting.[92] |

| Edwards' koala lemur | Megaladapis edwardsi | Madagascar | 1300-1430 | Hunting and vegetation changes caused by livestock.[67] |

| Bush moa | Anomalopteryx didiformis | New Zealand | 1310-1420 | Hunting.[92] |

| Eastern moa | Emeus crassus | South Island, New Zealand | 1320-1350 | Hunting.[93] |

| Haast's eagle | Hieraaetus moorei | South Island, New Zealand | 1320-1350 | Hunting?[93] |

| Southern sloth lemur | Palaeopropithecus ingens | Southwestern Madagascar | 1320-1630 | Hunting and vegetation changes caused by livestock.[67] |

| Hispaniola woodcock | Scolopax brachycarpa | Hispaniola | 1320-1380 | Undetermined.[94] |

| Waitaha penguin | Megadyptes waitaha | Coastal South Island, New Zealand | 1347-1529 | Hunting.[95] |

| Scarlett's shearwater | Puffinus spelaeus | Western South Island, New Zealand | 1350 | Predation by polynesian rats.[85] |

| Crested moa | Pachyornis australis | Subalpine South Island, New Zealand | 1396-1442 | Hunting.[92] |

15th-16th century

-

Taxidermied Falkland Island wolf, the closest relative of the South American Dusicyon avus (both extinct).

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenerife giant lizard | Gallotia goliath | Tenerife and La Palma, Canary Islands | 1400-1500 | Hunting.[87] | |

| Kauaʻi finch | Telespiza persecutrix | Kaua'i and Oahu, Hawaii, United States | 1425-1660 | Undetermined.[12] | |

| South Island giant moa | Dinornis robustus | South Island, New Zealand | 1451-1952[92] (1558-1728)[96] |

Hunting.[92] | |

| South American wolf | Dusicyon avus | Southern Cone | 1454-1626 | Possibly climate change, hunting, and competition with domestic dogs.[97] | |

| Broad-billed moa | Euryapteryx curtus | North, South, and Stewart Island of New Zealand | 1464-1637[92] (1542-1618)[98] |

Hunting.[92] | |

| Finsch's duck | Chenonetta finschi | New Zealand | 1500-1600 | 2014 (IUCN) | Hunting and predation by introduced polynesian rats.[99] |

| Olson's petrel | Bulweria bifax | Saint Helena | 1502 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting and introduced predators?[100] |

| Vespucci's giant rat | Noronhomys vespucii | Fernando de Noronha Island, Brazil | 1503 | 2008 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[101] |

| Galápagos giant rat | Megaoryzomys curioi | Santa Cruz, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador | 1520-1950[12] | 2008 (IUCN) | Possibly introduced predators.[102] |

| Puerto Rican hutia | Isolobodon portoricensis | Hispaniola and Gonâve; Introduced to Puerto Rico, Mona, and U.S. Virgin Islands |

1525 (confirmed) c. 1800 (unconfirmed) |

1994-2008 (IUCN) | Possibly predation by introduced black rats.[103] |

| Cayman Islands hutia | Capromys sp. | Cayman Islands | 1525-1625[5] c. 1700 (estimated)[79] |

Possibly hunting, introduced predators, and habitat loss caused by introduced ungulates.[79] | |

| Hispaniolan edible rat | Brotomys voratus | Hispaniola | 1550-1670[5] | 1994 (IUCN) | Introduced rats.[104] |

17th century

-

Depiction of a live dodo by Ustad Mansur, c. 1625.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bermuda saw-whet owl | Aegolius gradyi | Bermuda | c. 1600 | 2014 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[105] |

| Hodgens's waterhen | Tribonyx hodgenorum | New Zealand | 1600-1700 | 2014 (IUCN) | Hunting and predation by Polynesian rats.[106] |

| Bermuda night heron | Nyctanassa carcinocatactes | Bermuda | 1610 | 2014 (IUCN) | Possibly hunting and introduced predators.[107] |

| Eurasian aurochs | Bos primigenius primigenius | Mid-latitude Eurasia | 1627 | 2008 (IUCN) | Hunting, competition with, and diseases from domestic cattle. Domestic descendants survive worldwide, including feral populations.[108] There are several ongoing projects to re-breed wild-type aurochs and release them into the wild. |

| Ascension crake | Mundia elpenor | Ascension Island | 1656 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly introduction of rats and cats, although it is not attested by the time they arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries.[109] |

| Dodo | Raphus cucullatus | Mauritius, Mascarene Islands | 1662 (confirmed) 1688 (unconfirmed)[110] |

1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[111] |

| Larger malagasy hippopotamus | Hippopotamus laloumena | Eastern Madagascar | 1670-1950 (confirmed)[43] 1976 (unconfirmed) |

Increased human and cattle pressure after the introduction of prickly pear farming.[67] Its specific separation from the common hippopotamus has been questioned.[112] | |

| Réunion sheldgoose | Alopochen kervazoi | Réunion, Mascarene Islands | 1671-1672 | 1710 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting and habitat destruction.[113] |

| Réunion kestrel | Falco duboisi | Réunion | 1671-1672 | 2004 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[114] |

| Réunion fody | Foudia delloni | Réunion | c. 1672 | 2016 (IUCN) | Probably predation by introduced rats.[115] |

| Broad-billed parrot | Lophopsittacus mauritianus | Mauritius | 1673-1675 | 1693 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting.[116] |

| Réunion rail | Dryolimnas augusti | Réunion | 1674 | 2014 (IUCN) | Probably hunting and introduced rats and cats.[117] |

| Réunion pigeon | Nesoenas duboisi | Réunion | 1674 | 1988 (IUCN) | Probably introduced rats and cats.[118] |

| Réunion night heron | Nycticorax duboisi | Réunion | 1674 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[119] |

| Giant vampire bat | Desmodus draculae | Eastern South America; Central America (Pleistocene)[120] |

1675-1755 | Undetermined.[121] | |

| Mauritius sheldgoose | Alopochen mauritiana | Mauritius | 1693 | 1698 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting.[122] |

| Red rail | Aphanapteryx bonasia | Mauritius | 1693 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting and predation by introduced cats.[123] |

| Mauritius night heron | Nycticorax mauritianus | Mauritius | 1693 | 1988 (IUCN) | Probably hunting.[124] |

| Mascarene teal | Anas theodori | Mauritius; Réunion? | 1696 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[125] |

18th century

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guadeloupe parakeet | Psittacara labati | Guadeloupe | 1724 | 1988 (IUCN) | Probably hunting.[126] |

| Rodrigues rail | Erythromachus leguati | Rodrigues, Mascarene Islands | 1726 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[127] |

| Rodrigues owl | Mascarenotus murivorus | Rodrigues | 1726 | 1988 (IUCN) | Probably hunting, deforestation, and predation by introduced animals.[128] |

| Rodrigues starling | Necropsar rodericanus | Rodrigues | 1726 | 1761 1988 (IUCN) |

Undetermined.[129] |

| Rodrigues pigeon | Nesoenas rodericanus | Rodrigues | 1726 | 1988 (IUCN) | Probably predation by introduced black rats.[130] |

| Rodrigues night heron | Nycticorax megacephalus | Rodrigues | 1726 | 1761 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting.[131] |

| Réunion swamphen | Porphyrio caerulescens | Réunion, Mascarene Islands | c. 1730 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[132] |

| Pausinystalia brachythyrsum | Cameroon | 1746 | 1998 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[133] | |

| Atlantic gray whale | Eschrichtius robustus | North Atlantic and the Mediterranean | 550 (Europe) 1760 (North America) |

Whaling. The same species survives in the Pacific Ocean.[134] | |

| Rodrigues parrot | Necropsittacus rodricanus | Rodrigues | 1761 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[135] |

| Rodrigues solitaire | Pezophaps solitaria | Rodrigues | 1761 | 1778 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting and predation by introduced cats.[136] |

| Steller's sea cow | Hydrodamalis gigas | Bering Sea; Northern Pacific coasts from Japan to Baja California (Pleistocene) | 1762-1763 | 1768 1986 (IUCN) |

Hunting and reduction of kelp as a result of sea otter hunting, which caused proliferation of kelp-eating sea urchins.[137] |

| Réunion ibis | Threskiornis solitarius | Réunion | 1763 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[138] |

| Mauritius grey parrot | Lophopsittacus bensoni | Mauritius | 1764 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[139] |

| Raiatea parakeet | Cyanoramphus ulietanus | Raiatea, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1773 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly deforestation, hunting, and predation by introduced species.[140] |

| Raiatea starling | ?Aplonis ulietensis | Raiatea, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1774 | 1850 2016 (IUCN) |

Possibly predation by introduced rats.[141] |

| Moorea sandpiper | Prosobonia ellisi | Moorea, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1777 | 1988 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced rats.[142] |

| Tahiti sandpiper | Prosobonia leucoptera | Tahiti, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1777 | 1988 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced rats.[143] |

| Tahiti crake | Zapornia nigra | Tahiti, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1784 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly introduced predators.[144] |

| White swamphen | Porphyrio albus | Lord Howe Island, Australia | 1790 | 1834 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting.[145] |

| Bluebuck | Hippotragus leucophaeus | Overberg; South Africa (Pleistocene) |

1799-1800 | 1986 (IUCN)[146] | Vegetation change and disruption of migration routes after the Last Glacial Period, competition with domestic cattle, overhunting, and further habitat loss due to agriculture.[19] |

19th century

1800s-1820s

-

Drawing of a spotted green pigeon by John Latham (1823).

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kangaroo Island emu | Dromaius baudinianus | Kangaroo Island, Australia | 1802 (confirmed) 1827 (unconfirmed) |

1837 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting.[147] |

| King Island emu | Dromaius minor | King Island, Australia | 1802 | 1805 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting.[148] |

| Spotted green pigeon | Caloenas maculata | Tahiti, French Polynesia? | 1823 (confirmed) 1928 (unconfirmed) |

2008 (IUCN) | Hunting?[149] |

| Maupiti monarch | Pomarea pomarea | Maupiti, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1823 | 1988 (IUCN) | Probably introduced species.[150] |

| Mysterious starling | Aplonis mavornata | Mauke, Cook Islands | 1825 | 1988 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced brown rats.[151] |

| ʻĀmaui | Myadestes woahensis | Oahu, Hawaii, United States | 1825 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat destruction and introduced avian malaria.[152] |

| Mauritius blue pigeon | Alectroenas nitidissimus | Mauritius | 1826 (confirmed) 1837 (unconfirmed)[153] |

1988 (IUCN) | Hunting and deforestation.[154] |

| Kosrae crake | Zapornia monasa | Kosrae, Micronesia | 1827-1828 | 1988 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced rats.[155] |

| Kosrae starling | Aplonis corvina | Kosrae, Micronesia | 1828 | 1880 1988 (IUCN) |

Probably predation by introduced rats.[156] |

| Bonin grosbeak | Carpodacus ferreorostris | Bonin Islands, Japan | 1828 (confirmed) 1890 (unconfirmed) |

1854 1988 (IUCN) |

Possibly deforestation and predation by introduced cats and rats.[157] |

| Bonin thrush | Zoothera terrestris | Bonin Islands, Japan | 1828 | 1889 1988 (IUCN) |

Probably predation by introduced cats and rats.[158] |

| Tonga ground skink | Tachygyia microlepis | Tonga | c. 1829[159] | 1996 (IUCN) | Habitat loss and predation by introduced dogs, pigs, and rats.[160] |

1830s-1840s

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlas bear | Ursus arctos crowtheri | Northern Maghreb | 1834[161] | Possibly habitat fragmentation.[161] Two haplotypes are found in remains from the Vandal and Byzantine periods: one shared with Iberian bears that could have been introduced by humans, and another unique to Africa.[162] It is not known which type survived until more recent times. | |

| Oʻahu ʻakialoa | Akialoa ellisana | Oahu, Hawaii, United States | 1837 (confirmed) 1940 (unconfirmed) |

2016 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat destruction and introduced disease.[163] |

| Hoopoe starling | Fregilupus varius | Réunion, Mascarene Islands | 1837 (confirmed) 1850-1860 (unconfirmed) |

1988 (IUCN) | Possibly introduced disease, hunting, and habitat degradation.[164] |

| Oʻahu ʻōʻō | Moho apicalis | Oahu, Hawaii, United States | 1837 | 1988 (IUCN) | Habitat loss and introduction of disease-carrying mosquitos.[165] |

| Oʻahu nukupuʻu | Hemignathus lucidus | Oahu, Hawaii, United States | 1838-1841 (confirmed) 1860 (unconfirmed) |

1890 | Undetermined.[166] |

| Large Samoan flying fox | Pteropus coxi | Samoan Islands | 1839-1841 | 2020 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[167] |

| Dieffenbach's Rail | Hypotaenidia dieffenbachii | Chatham Islands, New Zealand | 1840 | 1872 1988 (IUCN) |

Possibly introduced predators and habitat loss from fire.[168] |

1850s-1860s

-

Painting of great auks by John James Audubon (1827-1838).

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern black rhinoceros | Diceros bicornis bicornis | Southwestern Africa | c. 1850 | Undetermined.[169] | |

| Spectacled cormorant | Phalacrocorax perspicillatus | Commander Islands; Kamchatka coast? | 1850 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[170] |

| String tree | Acalypha rubrinervis | Central ridge of St Helena island | 1850-1875 (captive) | 1998 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[171] |

| Great auk | Pinguinus impennis | North Atlantic and western Mediterranean | 1852 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting.[172] |

| Small Samoan flying fox | Pteropus allenorum | Upolu, Samoa | 1856 | 2020 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[173] |

| Kioea | Chaetoptila angustipluma | Hawaii, United States | 1859 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly deforestation, hunting, and introduced predators.[174] |

| Sea mink | Neovison macrodon | Atlantic coast of Canada and New England | c. 1860 (confirmed) 1894 (unconfirmed) |

2002 (IUCN) | Hunting for the fur trade.[175] |

| Jamaican poorwill | Siphonorhis americana | Jamaica | 1860 | Predation by introduced black rats, brown rats, and small Indian mongooses.[176] | |

| Small Mauritian flying fox | Pteropus subniger | Mauritius and Réunion | 1862 (confirmed) 1864-1873 (unconfirmed) |

1988 (IUCN) | Hunting and deforestation.[177] |

| Cuban macaw | Ara tricolor | Cuba and Juventud | 1864 (confirmed) 1885 (unconfirmed) |

2000 (IUCN) | Hunting for food and the exotic pet trade.[178] |

| Cape lion | Panthera leo melanochaita | Cape Province, South Africa | 1865 | Extermination campaign.[179] Genetics do not support subspecific differentiation between the Cape lion and living lions in Eastern Africa; if placed in a single subspecies, it would be P. l. melanochaita because of being the older name.[180] | |

| Eastern elk | Cervus canadensis canadensis | Eastern North America | 1867[181] | 1880[182] | Hunting. It's been argued (based on genetic data) that most or all elk subspecies in North America are actually the same, which would be C. c. canadensis due to being named first.[183][184] |

| Kawaihae hibiscadelphus | Hibiscadelphus bombycinus | Kawaihae, Hawaii, United States[185] | 1868[186] | Undetermined. |

1870s-1880s

-

Quagga painted by Jacques-Laurent Agasse (1821).

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cape warthog | Phacochoerus aethiopicus aethiopicus | Cape Province, South Africa | 1871 | Undetermined.[187] | |

| Tasmanian emu | Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis | Tasmania, Australia | 1845-1846 (wild)[188] 1873 (captive)[189] |

Hunting. | |

| Tristan moorhen | Gallinula nesiotis | Tristan da Cunha | 1873-1900 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting, predation by introduced cats, rats, and pigs; and habitat destruction by fire.[190] |

| Samoan woodhen | Pareudiastes pacificus | Savai'i, Samoa | 1873 (confirmed) 2003 (unconfirmed) |

Hunting and predation by introduced cats, rats, pigs, and dogs.[191] | |

| Large Palau flying fox | Pteropus pilosus | Palau | Before 1874 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly hunting and habitat degradation.[192] |

| Percy Island flying fox | Pteropus brunneus | Percy Islands, Australia | 1874 | 1996 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat loss.[193] |

| Labrador duck | Camptorhynchus labradorius | Atlantic coast of Canada and New England | 1875 (confirmed) 1878 (unconfirmed)[194] |

1988 (IUCN) | Hunting, egg harvesting, and habitat loss.[195] |

| New Zealand quail | Coturnix novaezelandiae | New Zealand | 1875 | 1988 (IUCN) | Introduced diseases?[196] |

| Broad-faced potoroo | Potorous platyops | Western Australia | 1875 | 1982 (IUCN) | Predation by feral cats and habitat loss.[197] |

| Falkland Islands wolf | Dusicyon australis | Falkland Islands | 1876 | 1986 (IUCN) | Extermination campaign.[198] |

| Himalayan quail | Ophrysia superciliosa | Uttarakhand, India | 1876 (confirmed) 2010 (unconfirmed) |

Hunting and habitat loss.[199] | |

| Jamaican rice rat | Oryzomys antillarum | Jamaica | 1877 | 2008 (IUCN) | Competition with introduced rats,[48] or predation by introduced mongooses.[200] |

| Jamaican petrel | Pterodroma caribbaea | Jamaica; Dominica and Guadeloupe? | 1879 | Hunting and predation by introduced rats, mongooses, pigs, and dogs.[201] | |

| Saint Lucia giant rice rat | Megalomys luciae | Saint Lucia | c. 1881 | 1994 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced mongooses.[202] |

| Quagga | Equus quagga quagga | Cape Province, South Africa | 1860-1865 (wild)[203] 1883 (captive) |

1889[203] 1986 (IUCN)[204] |

Hunting. |

| Hawaiian rail | Zapornia sandwichensis | Eastern Hawai'i (and Molokai?), United States | 1884 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly hunting and predation by introduced rats, cats, and dogs.[205] |

| Bennett's seaweed | Vanvoorstia bennettiana | Sydney Harbor, Australia | 1886 | 2003 (IUCN) | Habitat loss and pollution.[206] |

| Hokkaido wolf | Canis lupus hattai | Hokkaido, Japan | c. 1889 | Extermination campaign.[207][better source needed] | |

| Eastern hare-wallaby | Lagorchestes leporides | Interior southeastern Australia | 1889[208] | 1982 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat loss due to livestock grazing and wildfires.[209] |

| Sturdee's pipistrelle | Pipistrellus sturdeei | Haha-jima, Bonin Islands, Japan | 1889 | 1994 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[210] |

1890s

-

Kauaʻi nukupuʻu by J. G. Keulemans (1893-1900).

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portuguese ibex | Capra pyrenaica lusitanica | Portuguese-Galician border | c. 1890[211] | Hunting. | |

| New Caledonian rail | Cabalus lafresnayanus | New Caledonia | 1890 (confirmed) 1984 (unconfirmed) |

Probably predation by introduced dogs, cats, pigs, and rats.[212] | |

| Kauaʻi nukupuʻu | Hemignathus hanapepe | Kaua'i, Hawaii, United States | 1890 (confirmed)[213] 2007 (unconfirmed) |

Undetermined. | |

| New Zealand bittern | Ixobrychus novaezelandiae | New Zealand | 1890-1899 | 1988 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[214] |

| Lesser koa finch | Rhodacanthis flaviceps | Hawai'i Island, Hawaii, United States | 1891 | 1893 1988 (IUCN) |

Undetermined.[215] |

| Maui Nui ʻakialoa | Akialoa lanaiensis | Lana'i, Hawaii, United States | 1892 | 2016 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat destruction and introduced disease.[216] |

| ʻUla-ʻai-hawane | Ciridops anna | Hawai'i Island, Hawaii, United States | 1892 (confirmed) 1937 (unconfirmed) |

1988 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[217] |

| Nendo tube-nosed fruit bat | Nyctimene sanctacrucis | Santa Cruz Islands, Solomon Islands | 1892 (confirmed) 1907 (unconfirmed) |

1994 (IUCN) | Undetermined. Could be conspecific with the Island tube-nosed fruit bat.[218] |

| St. Vincent pygmy rice rat | Oligoryzomys victus | St. Vincent | 1892 | 2008 (IUCN) | Probably predation by introduced brown rats, black rats, and mongooses.[219] |

| Chatham fernbird | Poodytes rufescens | Chatham Islands, New Zealand | 1892 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat loss and predation by introduced cats.[220] |

| Chatham rail | Cabalus modestus | Chatham Islands, New Zealand | 1893-1895 | 1988 (IUCN) | Habitat destruction, predation and competition with introduced mammals.[221] |

| Kona grosbeak | Chloridops kona | Lana'i, Hawaii, United States | 1894 | 1988 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[222] |

| North Island takahē | Porhyrio mantelli | North Island, New Zealand | 1894 | 2000 (IUCN) | Climate-induced reduction of grasslands and hunting.[223] |

| Hawkins's rail | Diaphorapteryx hawkinsi | Chatham Islands, New Zealand | 1895 | 2005 (IUCN) | Hunting.[224] |

| Greater koa finch | Rhodacanthis palmeri | Hawai'i Island, Hawaii, United States | 1896 | 1906 1988 (IUCN) |

Possibly habitat destruction and introduced avian malaria.[225] |

| Newfoundland wolf | Canis lupus beothucus | Newfoundland, Canada | 1896 (confirmed)[226] 1911 (unconfirmed) |

Hunting. | |

| Martinique giant rice rat | Megalomys desmarestii | Martinique | 1897 (confirmed) 1902 (unconfirmed) |

1994 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced mongooses.[227] |

| Nelson's rice rat | Oryzomys nelsoni | Central María Madre Island, Mexico | 1897 | 1996 (IUCN) | Competition with introduced black rats.[228] |

| Hawaii mamo | Drepanis pacifica | Hawai'i Island, Hawaii, United States | 1899 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting, habitat destruction, and introduced disease.[229] |

20th century

1900s

-

Painting of pig-footed bandicoots by John Gould.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian moose | Alces alces caucasicus | Northern Caucasus and Transcaucasian shore of the Black Sea[230] | c. 1900 | Hunting. The subspecies' validity is questioned because moose from Russia recolonized the Caucasian moose's former range naturally over the 20th century.[231] | |

| Saint Croix racer | Borikenophis sanctaecrucis | Saint Croix, United States Virgin Islands | c. 1900 | Undetermined.[232] | |

| Leafshell | Epioblasma flexuosa | Tennessee, Cumberland, and Ohio River systems, United States | 1900[233] | Undetermined. | |

| Southern pig-footed bandicoot | Chaeropus ecaudatus | Interior Australia | 1901 (confirmed) 1950s (unconfirmed) |

1982 (IUCN) | Predation by feral cats and red foxes.[234] |

| Tennessee riffleshell | Epioblasma propinqua | Tennessee, Cumberland, Wabash, and Ohio River systems, United States | 1901[235] | Undetermined. | |

| Greater ʻamakihi | Viridonia sagittirostris | Wailuku river, Hawai'i Island, United States | 1901 | 1988 (IUCN) | Habitat destruction for sugarcane agriculture.[236] |

| Rocky Mountain locust | Melanoplus spretus | Rocky Mountains and North American Prairie | 1902 | 2014 (IUCN)[237] | Breeding habitat loss due to irrigation and cattle ranching. |

| Auckland merganser | Mergus australis | South, Stewart, and Auckland Island, New Zealand | 1902 | 1910 1988 (IUCN) |

Hunting and predation by introduced animals.[238] |

| North Island piopio | Turnagra tanagra | North Island, New Zealand | 1902 (confirmed) 1970 (unconfirmed) |

1988 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat destruction, hunting, and predation by introduced cats and rats.[239] |

| Guadalupe caracara | Caracara lutosa | Guadalupe Island, Mexico | 1903 | 1988 (IUCN) | Extermination campaign.[240] |

| Japanese wolf | Canis lupus hodophilax | Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū, Japan | 1905 (confirmed)[241] 1910-1996 (unconfirmed)[242][243] |

Hunting and a rabies-like epidemic.[207] | |

| South Island piopio | Turnagra capensis | South Island, New Zealand | 1905 (confirmed) 1963 (unconfirmed) |

1988 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat destruction and predation by introduced rats.[244] |

| Chatham bellbird | Anthornis melanocephala | Chatham Islands, New Zealand | 1906 | 1938 1988 (IUCN) |

Possibly habitat destruction, predation by rats and cats, and overhunting by collectionists.[245] |

| Black mamo | Drepanis funerea | Molokai and Maui, Hawaii, United States | 1907 | 1988 (IUCN) | Habitat destruction by introduced cattle and deer, and predation by introduced rats and mongooses.[246] |

| Huia | Heteralocha acutirostris | North Island, New Zealand | 1907 (confirmed)[247] 1963 (unconfirmed)[248] |

1988 (IUCN) | Hunting and deforestation of old growth forests to make pastures for livestock. |

| Huia louse | Rallicola extinctus | North Island, New Zealand | 1907? | 1990 | Extinction of its host.[249] |

| Robust white-eye | Zosterops strenuus | Lord Howe Island, Australia | 1908 | 1928 1988 (IUCN) |

Predation by black rats.[250] |

| Cumberland leafshell | Epioblasma stewardsonii | Tennessee and Coosa River systems, United States | 1909[251] | Undetermined. | |

| Tarpan | Equus ferus ferus | Europe | 1879 (wild)[252] 1909 (captive) |

Hunting and hybridization with domestic horses. |

1910s

-

Depiction of juvenile, male, and female passenger pigeons, by Louis Agassiz Fuertes (1910).

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maui hau kuahiwi | Hibiscadelphus wilderianus | Maui, Hawaii, United States | 1910[185] | 1978 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[253] |

| Slender-billed grackle | Quiscalus palustris | Lerma River and Xochimilco, Mexico | 1910 | 1988 (IUCN) | Draining of marshlands.[254] |

| Cape Verde giant skink | Chioninia coctei | Cape Verde | 1912 (confirmed) 2005 (unconfirmed) |

1996 (IUCN) | Predation by feral cats.[255] |

| Guadalupe storm petrel | Oceanodroma macrodactyla | Guadalupe Island, Mexico | 1912 | Predation by feral cats, and habitat degradation by goat grazing.[256] | |

| Passenger pigeon | Ectopistes migratorius | Eastern North America | 1901 (wild, confirmed)[257] 1902-1907 (unconfirmed)[257][258] 1914 (captive) |

Hunting and habitat loss. | |

| Laughing owl | Ninox albifacies | New Zealand | 1914 (confirmed) 1960 (unconfirmed)[259] |

1988 (IUCN) | Competition or predation by introduced stoats and cats.[260] |

| Kenai Peninsula wolf | Canis lupus alces | Kenai Peninsula, Alaska | c. 1915[261] | Extermination campaign. | |

| Lord Howe starling | Aplonis fusca hulliana | Lord Howe Island, Australia | 1918 | 1928 1988 (IUCN) |

Predation by introduced black rats.[262] |

| Bernard's wolf | Canis lupus bernardi | Banks Island, Canada | 1918-1952[263] | Undetermined. It's been suggested that Bernard's wolf should be merged with the extant arctic wolf[264] or other wolves from the continent.[263] | |

| Carolina parakeet | Conorupsis carolinensis | Eastern and central United States | 1910 (wild) 1918 (captive) 1930s (wild, unconfirmed) |

1988 (IUCN) | Hunting, habitat loss, and competition with introduced bees.[265] |

| Lānaʻi hookbill | Dysmorodrepanis munroi | Lana'i, Hawaii, United States | 1918 | 1988 (IUCN) | Habitat destruction for pineapple agriculture, and predation by introduced cats and rats.[266] |

1920s

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida black wolf | Canis rufus[267] floridanus | Southeastern United States | c. 1920 | Hunting and habitat loss.[267] | |

| Great Plains wolf | Canis lupus nubilus | North American prairie | 1922[268] | 1926[269] | Extermination campaign. The Great Plains wolf has been later determined to be continuous morphologically[264] and genetically[270] with the still existing Mexican wolf, which would use the name C. l. nubilus if placed in the same subspecies, due to being the older one. |

| Norfolk Island starling | Aplonis fusca fusca | Norfolk Island, Australia | 1923 | 1968 1988 (IUCN) |

Undetermined.[262] |

| Laysan honeycreeper | Himatione fraithii | Laysan, Hawaii, United States | 1923 | 2016 (IUCN) | Habitat destruction by introduced rabbits.[271] |

| Round combshell | Epioblasma personata | Tennessee, Wabash, and Ohio River systems, United States | 1924 | Undetermined.[272] | |

| California grizzly bear | Ursus arctos californicus | California, United States | 1924 | Hunting.[273] | |

| Bubal hartebeest | Alcelaphus buselaphus buselaphus | North Africa and Southern Levant | 1925 | Hunting.[274] | |

| Anthony's woodrat | Neotoma bryanti anthonyi | Isla Todos Santos, Mexico | 1926 | 2008 (IUCN) | Predation by feral cats.[275] |

| Caucasian wisent | Bison bonasus caucasicus | Caucasus Mountains | 1927[276] | Hunting. Hybrid descendants exist in captivity, and have been reintroduced to the wild.[277] | |

| Syrian wild ass | Equus hemionus hemippus | Near East | 1927 | Hunting.[278] | |

| Cry pansy | Viola cryana | Cry, Yonne, France | 1927 | Overcollection by botanists and limestone quarrying.[279] | |

| Lord Howe gerygone | Gerygone insularis | Lord Howe Island, Australia | 1928 | 1936 1988 (IUCN) |

Predation by introduced rats.[280] |

| Acalypha wilderi | Northwestern Rarotonga, Cook Islands | 1929 | 2014 (IUCN) | Deforestation for agriculture and housing development. Doubts exist about it being distinct from still living A. raivavensis and A. tubuaiensis; if indeed the same, the older name A. wilderi prevails.[281] |

1930s

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tahiti rail | Hypotaenidia pacifica | Tahiti, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1930-1939 | 1988 (IUCN) | Probably predation by introduced cats and rats.[282] |

| St Kilda house mouse | Mus musculus muralis | St Kilda, Scotland | 1930 | Complete evacuation of St Kilda's human population, which it depended on.[283] | |

| Darwin's Galápagos mouse | Nesoryzomys darwini | Santa Cruz, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador | 1930 | Competition, predation, and exotic pathogens from introduced black rats.[284] | |

| Nuku Hiva monarch | Pomarea nukuhivae | Nuku Hiva, Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia | 1930-1939 (confirmed) 1977 (unconfirmed) |

1972 2006 (IUCN) |

Probably habitat destruction and predation by introduced species.[285] |

| Bunker's woodrat | Neotoma bryanti bunkeri | Coronados Islands, Mexico | 1931 | 2008 (IUCN) | Depletion of food resources and predation by feral cats.[286] |

| Heath hen | Tympanuchus cupido cupido | East Coast of the United States | 1932 | Hunting, predation by feral cats, wildfires, and histomoniasis transmitted by domestic poultry.[287][288] | |

| Hawaiʻi ʻōʻō | Moho nobilis | Lana'i, Hawaii, United States | 1934 | 1988 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat loss and disease.[289] |

| Indefatigable Galápagos mouse | Nesoryzomys indefessus | Santa Cruz and Baltra, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador | 1934 | 2008 (IUCN) | Introduction of black rats.[290] |

| Desert rat-kangaroo | Caloprymnus campestris | Central Australia | 1935 (confirmed) 1957-2011 (unconfirmed) |

1994 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced red foxes and cats.[291] |

| Mogollon mountain wolf | Canis lupus mogollonensis | Arizona, United States | 1935[292][better source needed] | Hunting. The subspecific differences between extinct Great Plains wolf, Mogollon mountain wolf, Southern Rocky Mountain wolf, and surviving Mexican wolf have been denied on morphological grounds.[264] | |

| Southern Rocky Mountain wolf | Canis lupus youngi | Southern Rocky Mountains | 1935[292][better source needed] | ||

| Thylacine | Thylacinus cynocephalus | Australia and New Guinea | 1931 (wild, confirmed)[293] 1936 (captive) 1937-2000 (wild, unconfirmed)[294] |

1982 (IUCN)[295] | Competition with humans and dingos, extermination campaign (in Tasmania). |

| Bali tiger | Panthera tigris balica | Bali, Indonesia | 1937 (confirmed)[179] 1972 (unconfirmed) |

Hunting and habitat loss. Genetics do not support a subspecific differentiation with the living Sumatran tiger.[180] | |

| Marquesas swamphen | Porphyrio paepae | Hiva Oa and Tahuata, Marquesas, French Polynesia | 1937 | 2014 (IUCN) | Probably hunting and predation by rats and cats.[296] |

| Eastern cougar | Puma concolor couguar | Eastern North America | 1938 (confirmed)[297] 1992 (unconfirmed) |

2011[298] | Hunting. Genetics do not support subspecies differentiation between the eastern cougar and living cougars in Florida and Western North America;[180] if placed under a single subspecies, this would have the name P. c. couguar because of being older. |

| Schomburgk's deer | Rucervus schomburgki | Central Thailand | 1932 (wild) 1938 (captive) |

1994 (IUCN) | Hunting.[299] |

| Grand Cayman thrush | Turdus ravidus | Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands | 1938 | 1965 1988 (IUCN) |

Probably habitat loss.[300] |

| Toolache wallaby | Macropus greyi | Southeastern Australia | 1924 (wild, confirmed) 1939 (captive) 1943-1970s (wild, unconfirmed) |

1982 (IUCN) | Habitat loss to agriculture, hunting, and predation by introduced red fox.[301] |

1940s

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugarspoon | Epioblasma arcaeformis | Cumberland and Tennessee river systems, United States | c. 1940 | 1983 (IUCN) | Damming.[302] |

| Lesser ʻakialoa | Akialoa obscura | Hawai'i Island, Hawaii, United States | 1940 | 1994 (IUCN) | Possibly deforestation and introduced disease-carrying mosquitos.[303] |

| Cascade mountain wolf | Canis lupus fuscus | Continental Cascadia[264] | 1940[292][better source needed] | Hunting. | |

| Arabian ostrich | Struthio camelus syriacus | Arabian Peninsula and the Near East | c. 1941 (confirmed) 1966 (unconfirmed) |

Hunting.[304] | |

| Texas gray wolf | Canis lupus monstrabilis | Texas, United States | 1942[292][better source needed] | Hunting. The Texas gray wolf has been at times included within either the extinct Great Plains wolf or the living Mexican wolf on morphological grounds.[264] | |

| Barbary lion | Panthera leo leo | North Africa | 1943 (confirmed)[179] 1956 (unconfirmed) |

Habitat loss from desertification and human activities, followed by extermination campaign. Hybrid descendants are believed to exist in captivity.[305] However, genetics do not support subspecies differentiation with living wild lions in Asia, West and Central Africa,[180] which would be named P. l. leo if placed within a single subspecies. | |

| Desert bandicoot | Perameles eremiana | Central Australia | 1943 (confirmed) 1960-1970 (unconfirmed) |

1982 (IUCN) | Predation by cats and foxes, competition with European rabbits, and changes to the fire regime after the British colonization of Australia.[306] |

| American ivory-billed woodpecker | Campephilus principalis principalis | Southern United States | 1944 (confirmed)[307] 2008 (unconfirmed)[308][309] |

Logging and hunting. | |

| Laysan rail | Zapornia palmeri | Laysan, Hawaii, United States | 1944 | 1988 (IUCN) | Habitat destruction by introduced rabbits and guinea pigs, and predation by introduced rats.[310] |

| Wake Island rail | Hypotaenidia wakensis | Wake Island, United States | 1945 | 1988 (IUCN) | Hunting and destruction caused by fighting in World War II.[311] |

| Pink-headed duck | Rhodonessa caryophyllacea | Northeast India, Bangladesh, and northern Myanmar | 1949 (confirmed) 2011 (unconfirmed) |

Habitat loss to agriculture.[312] |

1950s

-

Japanese sea lion drawn by Philipp Franz von Siebold (1823-1829).

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Swan Island hutia | Geocapromys thoracatus | Little Swan Island, Honduras | c. 1950 | 1996 (IUCN) | Introduced rats.[313] |

| San Martín Island woodrat | Neotoma bryanti martinensis | Isla San Martín, Mexico | 1950-1960 | 2008 (IUCN) | Predation by feral cats.[314] |

| Japanese sea lion | Zalophus japonicus | Japanese Islands and Korea | 1951 (confirmed) 1975 (unconfirmed) |

1994 (IUCN) | Hunting.[315] |

| Caribbean monk seal | Neomonachus tropicalis | Caribbean Sea, Bahamas, and Gulf of Mexico | 1952 (confirmed) 1962 (unconfirmed)[316] |

1994 (IUCN) | Hunting.[317] 2008[318] |

| Coosa elktoe | Alasmidonta mccordi | Coosa River, Alabama, United States | 1956 | 2000 (IUCN) | Impoundment of the Coosa River.[319] |

| Imperial woodpecker | Campephilus imperialis | North-Central Mexico | 1956 | Hunting and habitat loss.[320] | |

| Levuana moth | Levuana iridescens | Viti Levu, Fiji | 1956[321] | 1994 (IUCN)[322] | Introduction of the parasitic fly Bessa remota by coconut farmers, as a form of biological pest control. It's been argued that L. iridescens was not actually native to Fiji and that lack of post-1956 records is the result of diminished enthomological research after Fiji's independence.[321] |

| Crescent nail-tail wallaby | Onychogalea lunata | Western and central Australia | 1956[323] | 1982 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced foxes and feral cats, human-induced habitat degradation.[324] |

| Scioto madtom | Noturus trautmani | Big Darby Creek, Ohio, United States | 1957 | 2013 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[325] |

| Hainan ormosia | Ormosia howii | Hainan and Guangdong, China | 1957[326] | 1998 (IUCN) | Possibly deforestation for agriculture.[327] |

| Blue Pike | Stizostedion vitreum glaucum | Lake Erie, Ontario, and Niagara River | 1958 | 1983 | Overfishing and hybridization with walleye.[328] |

| Santa Barbara song sparrow | Melospiza melodia graminea | Santa Barbara Island, California, United States | 1959 | 1983 | Wildfire.[328] |

1960s

-

Only kouprey seen outside Cambodia: a male at Vincennes Zoo, photographed in 1937.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesser bilby | Macrotis leucura | Deserts of Australia | c. 1960 | 1982 (IUCN) | Probably predation by introduced cats and red foxes, and changes to the fire regime.[329] |

| Candango mouse | Juscelinomys candango | Brasilia, Brazil | 1960 | 2008 (IUCN) | Urban sprawl.[330] |

| Semper's warbler | Leucopeza semperi | St Lucia mountains | 1961 (confirmed) 2015 (unconfirmed) |

Predation by introduced Javan mongooses.[331] | |

| Kākāwahie | Paroreomyza flammea | Molokai, Hawaii, United States | 1961-1963 | 1979 1994 (IUCN) |

Probably habitat destruction and introduced disease.[332] |

| Red-bellied gracile opossum | Cryptonanus ignitus | Jujuy, Argentina | 1962 | 2008 (IUCN) | Habitat loss to agriculture and industry development.[333] |

| Hawaii chaff flower | Achyranthes atollensis | The atolls Kure, Midway, Pearl and Hermes, and Laysan of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, United States | 1964 | 2003 (IUCN) | Habitat loss due to the construction of military installations.[334] |

| Crested shelduck | Tadorna cristata | Primorye, Hokkaido, and Korea; Northeastern China? |

1964 (confirmed) 1971 (unconfirmed) |

Undetermined.[335] | |

| Turgid blossom | Epioblasma turgidula | Southern Appalachians and Cumberland Plateau, United States | 1965 | Damming and water pollution.[336] | |

| Narrow catspaw | Epioblasma lenior | Tennessee River system, United States | 1967 | Damming.[337] | |

| New Zealand greater short-tailed bat | Mystacina robusta | New Zealand | 1967 | 1988 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced Polynesian and black rats.[338] |

| Amistad gambusia | Gambusia amistadensis | Goodenough Spring, Texas, United States | 1968 (wild) | 1987 | Flooding of the spring by the Amistad Reservoir, hybridization and predation.[328] |

| Kauaʻi ʻakialoa | Akialoa stejnegeri | Kaua'i, Hawaii, United States | 1969 | 2016 (IUCN) | Possibly habitat destruction and introduced disease.[339] |

| Tubercled blossom | Epioblasma torulosa torulosa | Tennessee and Ohio River systems, United States | 1969 | Impoundment, siltation, and pollution.[340] | |

| Kouprey | Bos sauveli | Northeastern Cambodia | 1969-1970 (confirmed)[341] 1982-1983 (unconfirmed)[342] |

Hunting. |

1970s

-

A Caspian tiger photographed at the Berlin Zoo in 1899.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi gazelle | Gazella saudiya | Arabian Peninsula | 1970 | 2008 (IUCN) | Hunting.[343] |

| Acornshell | Epioblasma haysiana | Tennessee and Cumberland River systems, United States | 1970-1979 | Exposure to domestic sewage.[344] | |

| Tropical acidweed | Desmarestia tropica | Galápagos Islands, Ecuador | 1972 | Undetermined.[345] | |

| Mason River myrtle | Myrcia skeldingii | Mason River, Jamaica | 1972 | 1998 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[346] |

| Tecopa pupfish | Cyprinodon nevadensis calidae | Tecopa Hot Springs, California, United States | 1972 | 1982 | Habitat degradation and introduced bluegill sunfish and mosquito fish.[328] |

| Bar-winged rail | Hypotaenidia poeciloptera | Fiji | 1973 | 1994 (IUCN) | Predation by introduced cats and mongooses.[347] |

| Mexican grizzly bear | Ursus arctos nelsoni | Aridoamerica | 1976[348] | Hunting. | |

| Colombian grebe | Podiceps andinus | Bogotá wetlands, Colombia | 1977 | 1994 (IUCN) | Habitat loss, pollution, hunting, and predation of chicks by introduced rainbow trout.[349] |

| Eiao monarch | Pomarea fluxa | Eiao, Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia | 1977 | 2006 (IUCN) | Possibly predation by introduced cats, black rats, and Polynesian rats; disease transmitted by introduced chestnut-breasted mannikin, and habitat loss due to grazing by sheep.[350] |

| White-eyed river martin | Eurochelidon sirintarae | Central Thailand | 1978 | Hunting and habitat loss.[351] | |

| Little earth hutia | Mesocapromys sanfelipensis | Key Juan García, Cuba | 1978 | Hunting, man-made fires, and competition with black rats.[352] | |

| Japanese river otter | Lutra lutra whiteleyi | Japan | 1979 | 2012 | Hunting and habitat loss.[353] |

| Caspian tiger | Panthera tigris virgata | Transcaucasia, Kurdistan, Hyrcania, Afghanistan, and Turkestan | 1972 (wild, confirmed) 1979 (captive) 2007 (wild, unconfirmed) |

Hunting and desertification.[179] Genetics do not support subspecific differentiation with extant mainland tigers.[180] | |

| Mount Glorious day frog | Taudactylus diurnus | Southeast Queensland, Australia | 1979 | 2002 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[354] |

1980s

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maui nukupu'u | Hemignathus affinis | Maui, Hawaii, United States | 1980[355] | Undetermined. | |

| Olomaʻo | Myadestes lanaiensis | Islands Maui, Lana'i, and Molokai in Hawaii, United States | 1980 (confirmed) 2005 (unconfirmed) |

Disease and habitat degradation caused by introduced pigs, axis deer, and mosquitos.[356] | |

| Mariana mallard | Anas platyrhynchos oustaleti | Mariana Islands | 1979 (wild) 1981 (captive)[357] |

2004 | Hunting and habitat loss to agriculture.[358] |

| Puhielelu hibiscadelphus | Hibiscadelphus crucibracteatus | Lana'i, Hawaii, United States | 1981 | Predation by introduced axis deer.[185] | |

| Bishop's ʻōʻō | Moho bishopi | Molokai, Hawaii, United States | 1981 | 2000 (IUCN) | Habitat loss to agriculture and livestock grazing, followed by the introduction of black rats and disease-carrying mosquitos.[359] |

| Southern gastric-brooding frog | Rheobatrachus silus | Southeast Queensland, Australia | 1981 | 2002 (IUCN) | Undetermined, possibly chytridiomycosis.[360] |

| Galápagos damsel | Azurina eupalama | Galápagos Islands, Ecuador | 1982-1983 | 1982-83 El Niño event.[361] | |

| San Marcos gambusia | Gambusia georgei | San Marcos spring and river, Texas, United States | 1983 | 1990 | Reduced flow and pollution from agriculture, introduced fishes and plants (Colocasia esculenta), and hybridization with Gambusia affinis.[362] |

| 24-rayed sunstar | Heliaster solaris | Galápagos Islands, Ecuador | 1983 | 1982-83 El Niño event.[363] | |

| Guam flycatcher | Myiagra freycineti | Guam | 1983 | 1994 (IUCN) 2004[358] |

Predation by the introduced brown tree snake.[364] |

| Formosan clouded leopard | Neofelis nebulosa brachyura | Taiwan | 1983 (confirmed) 2019 (unconfirmed) |

2013[365][better source needed] | Hunting. Subspecific status has been denied on morphological and genetic grounds.[180] |

| Aldabra brush-warbler | Nesillas aldabrana | Malabar Island, Seychelles | 1983 | 1994 (IUCN) | Possibly predation by introduced cats and rats, and habitat degradation by goats and tortoises.[366] |

| Atitlán grebe | Podilymbus gigas | Lake Atitlán, Guatemala | 1983-1986 | 1994 (IUCN) | Predation and competition with introduced largemouth bass, water level fall after the 1976 Guatemala earthquake, and degradation of breeding sites due to reed-cutting and tourism development.[367] |

| Green blossom | Epioblasma torulosa gubernaculum | Tennessee River system, United States | 1984 | Impoundment, siltation, and pollution.[368] | |

| Javan tiger | Panthera tigris sondaica | Java, Indonesia | 1984 | 1994 | Hunting and habitat loss.[179] Genetics do not support subspecies differentiation with the extant Sumatran tiger; if placed in the same subspecies, this would have the name P. t. sondaica due to being older.[180] |

| Christmas Island shrew | Crocidura trichura | Christmas Island, Australia | 1985 (confirmed) 1998 (unconfirmed) |

Undetermined.[369] | |

| Kāmaʻo | Myadestes myadestinus | Kaua'i, Hawaii, United States | 1985 (confirmed) 1991 (unconfirmed) |

2004 (IUCN) | Habitat loss and disease spread by introduced mosquitos.[370] |

| Ua Pou monarch | Pomarea mira | Ua Pou, Marquesas, French Polynesia | 1985 (confirmed) 2010 (unconfirmed) |

Deforestation and predation by introduced black rats.[371] | |

| Northern gastric-brooding frog | Rheobatrachus vitellinus | Mid-eastern Queensland, Australia | 1985 | 2002 (IUCN) | Undetermined, possibly chytridiomycosis.[372] |

| Alaotra grebe | Tachybaptus rufolavatus | Lake Alaotra, Madagascar | 1985 (confirmed) 1988 (unconfirmed) |

2010 (IUCN) | Hunting, accidental capture in nylon gillnets, predation and competition with introduced largemouth bass, striped snakehead, and Tilapia; habitat degradation from agriculture, and hybridization with the little grebe.[373] |

| Zanzibar leopard | Panthera pardus adersi | Unguja Island, Tanzania | 1986 (confirmed) 2018 (unconfirmed) |

Extermination campaign.[179] The subspecies has been subsumed into the extant African leopard on morphological grounds.[374] | |

| Banff longnose dace | Rhinichthys cataractae smithi | Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada | 1986 | 1987 | Habitat degradation, competition and hybridization with introduced fishes.[375] |

| Dusky seaside sparrow | Ammospiza maritima nigrescens | Merritt Island and the St. Johns River, Florida, United States | 1980 (wild) 1987 (captive) |

1990 | Flooding and draining of marshes to reduce mosquito population.[376] |

| Cuban ivory-billed woodpecker | Campephilus principalis bairdii | Cuba | 1987 (confirmed) 1998 (unconfirmed) |

Habitat loss.[307] | |

| Kauaʻi ʻōʻō | Moho braccatus | Kauaʻi, Hawaii, United States | 1987 | 2000 (IUCN) | Habitat loss and introduced black rats, pigs, and disease-carrying mosquitos. The last female was killed by Hurricane Iwa during the 1982-1983 El Niño event.[377] |

| Bachman's warbler | Vermivora bachmanii | Southeastern United States and Cuba | 1988[378] | Habitat destruction from swampland draining and sugarcane agriculture.[379] | |

| Golden toad | Incilius periglenes | Monteverde, Costa Rica | 1989 | 2020 (IUCN) | Anthropogenic global warming, chytridiomycosis, and airborne pollution.[380] |

1990s

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbary leopard | Panthera pardus panthera | Atlas Mountains | 1996 | Hunting.[179] The subspecies has been subsumed into the extant African leopard on morphological grounds.[374] | |

| Swollen Raiatea Tree Snail | Partula turgida | Raiatea, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1992 (wild) 1996 (captive) |

1996 (IUCN) | Predation by the introduced carnivorous snail Euglandina rosea.[381] |

3rd millennium CE

21st century

2000s

-

"Qiqi", the last captive Chinese river dolphin, which died in 2002.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrenean ibex | Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica | Pyrenees;[211] Cantabrian Mountains?[382] |

2000 (briefly cloned in 2003) |

2000 (IUCN)[383] | Hunting, competition for pastures and diseases from exotic and domestic ungulates.[384][385] |

| Glaucous macaw | Anodorhynchus glaucus | Border area of Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, and Uruguay | 2001 | Deforestation for agriculture and livestock grazing, particularly of the Yatay palm in which it fed.[386] | |

| Polynesian tree snail | Partula labrusca | Raiatea, Society Islands, French Polynesia | 1992 (wild) 2002 (captive) |

2007 (IUCN) | Predation by Euglandina rosea.[387] |

| Saint Helena olive | Nesiota elliptica | Saint Helena | 1994 (wild) 2003 (captive) |

2003 (IUCN) | Deforestation for fuel and timber, and use of the land for plantations of New Zealand flax, leading to inbreeding depression and fungal infections from reduced numbers.[388] |

| Chinese paddlefish | Psephurus gladius | Yangtze and Yellow River basins, China | 2003 | 2019 (IUCN)[389] | Overfishing; construction of the Gezhouba and Three Gorges dams, causing population fragmentation and blocking the anadromous spawning migration. |

| Chinese river dolphin | Lipotes vexillifer | Middle and lower Yangtze, China | 2002 (captive) 2007-2018 (wild, unconfirmed) |

2007[390] | Hunting, increased pollution and naval traffic, and habitat loss including as a result of the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. |

| Po'ouli | Melamprosops phaeosoma | Eastern Maui, Hawaii, United States | 2004 | 2019 (IUCN) | Introduced avian malaria and predators.[391] |

| Western black rhinoceros | Diceros bicornis longipes | South Sudan to Nigerian-Niger border area | 2006 | 2011 (IUCN) | Hunting.[392] |

| South Island kōkako | Callaeas cinereus | South Island, New Zealand | 2007 (confirmed) 2018 (unconfirmed) |

Habitat destruction from logging and grazing ungulates, and predation by introduced black rats, brush-tailed possums, and stoats.[393] | |

| Bramble Cay melomys | Melomys rubicola | Bramble Cay, Australia | 2009 | 2015 (IUCN)[394] | Sea level rise as a consequence of global warming.[395] |

| Christmas Island pipistrelle | Pipistrellus murrayi | Christmas Island, Australia | 2009 | 2017 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[396] |

2010s

-

"Lonesome George", the last full-blooded Pinta Island tortoise, photographed in 2006.

| Common name | Binomial name | Former range | Last record | Declared extinct | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnamese rhinoceros | Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus | South China and Indochina | 2010 | 2011 | Hunting.[397] |

| Pinta Island tortoise | Chelonoidis abingdonii | Pinta, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador | 1971 (wild) 2012 (captive) |

2012 (IUCN)[398] | Hunting and overgrazing by introduced goats. Hybrid descendants of this species still exist in other Galapagos islands, as a result of human action.[399] |

| Christmas Island forest skink | Emoia nativitatis | Christmas Island, Australia | 2008 (wild) 2014 (captive) |

2017 (IUCN) | Undetermined.[400] |

| Rabbs' fringe-limbed treefrog | Ecnomiohyla rabborum | El Valle de Antón, Panama | 2008 (wild) 2016 (captive) |

Chytridiomycosis.[401] |

See also

- List of extinct animals

- Extinction event

- Quaternary extinction event

- Holocene extinction

- Timeline of evolution

- Timeline of environmental events

- List of environment topics

- List of environmental issues