Artemis program

| |

| Program overview | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Organization | NASA and partners: ESA, JAXA, and CSA |

| Manager | Mike Sarafin[1] |

| Purpose | Crewed lunar exploration |

| Status | Ongoing |

| Program history | |

| Cost | US$35 billion (2020–2024)[2] |

| Duration | 2017–present[3] |

| First flight | Artemis I (16 November 2022, 06:47:44 UTC)[4][5] |

| First crewed flight | Artemis II (NET May 2024)[6] |

| Launch site(s) |

|

| Vehicle information | |

| Crewed vehicle(s) | |

| Launch vehicle(s) |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| United States space program |

|---|

|

The Artemis program is a robotic and human Moon exploration program led by the United States' National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) with three partner agencies: European Space Agency (ESA), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and Canadian Space Agency (CSA). If successful, the Artemis program will reestablish a human presence on the Moon for the first time since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. The major components of the program are the Space Launch System (SLS), Orion spacecraft, Lunar Gateway space station and the commercial Human Landing Systems, including Starship HLS. The program's long-term goal is to establish a permanent base camp on the Moon and facilitate human missions to Mars.

The Artemis program is a collaboration of government space agencies and private spaceflight companies, bound together by the Artemis Accords and supporting contracts. As of July 2022, twenty-one countries have signed the accords,[9] including traditional U.S. space partners (such as the European Space Agency as well as agencies from Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom) and emerging space powers such as Brazil, South Korea, and the United Arab Emirates.[10]

The Artemis program was formally established in 2017 during the Trump administration; however, many of its components such as the Orion spacecraft were developed during the previous Constellation program (2005–2010) during the Bush administration, and after its cancellation during the Obama administration. Orion's first launch, and the first use of the Space Launch System, was originally set in 2016, but was rescheduled and launched on 16 November 2022 as the Artemis 1 mission, with robots and mannequins aboard. According to plan, the crewed Artemis 2 launch will take place in 2024, the Artemis 3 crewed lunar landing in 2025, the Artemis 4 docking with the Lunar Gateway in 2027, and future yearly landings on the Moon thereafter. However, some observers note that the program's cost and timeline are likely to be overrun and delayed, due to, according to internal and external review, NASA's inadequate management of contractors.[11][12]

Overview

The Artemis program is organized around a series of Space Launch System (SLS) missions. These space missions will increase in complexity and are scheduled to occur at intervals of a year or more. NASA and its partners have planned Artemis I through Artemis V missions; later Artemis missions have also been proposed. Each SLS mission centers on the launch of an SLS launch vehicle carrying an Orion spacecraft. Missions after Artemis II will depend on support missions launched by other organizations and spacecraft for support functions.

SLS missions

Artemis I (2022) is an uncrewed test of the SLS and Orion, and is the first test flight for both craft.[a] The goal of the Artemis I mission is to place Orion into a lunar orbit, and then return it to Earth. The SLS uses the ICPS second stage, which will perform the trans-lunar injection burn to send Orion to lunar space. Orion will brake into a retrograde distant polar lunar orbit and remain for about six days before boosting back toward Earth. The Orion capsule will separate from its service module, re-enter the atmosphere for aerobraking, and splash down under parachutes.[13]

Artemis II (2024) will be the first crewed test flight of SLS and the Orion spacecraft.[14] The four crew members will perform extensive testing in Earth orbit, and Orion will then be boosted into a free-return trajectory around the Moon, which will return Orion back to Earth for re-entry and splashdown. Launch is scheduled no earlier than May 2024.[15]

Artemis III (2025) will be a crewed lunar landing.[14] The mission depends on a support mission to place a Human Landing System (HLS) in place in a near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO) of the Moon prior to the launch of SLS/Orion. After HLS reaches NRHO, SLS/Orion will send the Orion spacecraft with a crew of four, which is intended to include the first woman and the first person of color to land on the Moon, to rendezvous and dock with HLS.[b] Two astronauts will transfer to HLS, which will descend to the lunar surface and spend about 6.5 days on the surface. The astronauts will perform at least two EVAs on the surface before the HLS ascends to return them to a rendezvous with Orion. Orion will return the four astronauts to Earth. Launch is scheduled no earlier than 2025.[16]

Artemis IV (2027) is a crewed mission to the Lunar Gateway station in NRHO, using an SLS Block 1B. A prior support mission will deliver the first two gateway modules to NRHO. The extra power of the Block 1B will allow SLS/Orion to deliver the I-HAB gateway module for connection to the Gateway. Launch is scheduled no earlier than 2027.[17]

Artemis V through Artemis VIII and beyond are proposed to land astronauts on the lunar surface, where they will take advantage of increasing amounts of infrastructure that are to be landed by support missions. These will include habitats, rovers, scientific instruments, and resource extraction equipment.[18]

Support missions

Support missions include robotic landers, delivery of Gateway modules, Gateway logistics, delivery of the HLS, and delivery of elements of the Moon base. Most of these missions are executed under NASA contracts to commercial providers.

Under the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, several robotic landers will deliver scientific instruments and robotic rovers to the lunar surface after Artemis I. Additional CLPS missions are planned throughout the Artemis program to deliver payloads to the Moon base. These include habitat modules and rovers in support of crewed missions.

The Human Landing System (HLS) is a spacecraft that can convey crew members from NRHO to the lunar surface, support them on the surface, and return them to NRHO. Each crewed landing needs one HLS, although some or all of the spacecraft may be reusable. Each HLS must be launched from Earth and delivered to NRHO in one or more launches. The initial commercial contract was awarded to SpaceX for two Starship HLS missions, one uncrewed and one crewed as part of Artemis 3. These two missions each require one HLS launch and multiple fueling launches, all on SpaceX Starship launchers. As of June 2022[update], NASA has also exercised an option under the initial contract to commission an upgraded Starship HLS design and third demonstration lunar mission under new sustainability rules it is drafting. It intends to pursue another HLS design from outside SpaceX in parallel, for redundancy and competition.[19][20]

The first two gateway modules (PPE and HALO) will be delivered to NRHO in a single launch using a Falcon Heavy launcher. Originally planned to be available prior to Artemis III, as of 2021 it is planned for availability before Artemis IV.

The Gateway will be resupplied and supported by launches of Dragon XL spacecraft launched by Falcon Heavy. Each Dragon XL will remain attached to Gateway for up to six months. the Dragon XLs will not return to Earth, but will be disposed of, probably by deliberate crashes on the lunar surface.

History

Early history

The Artemis program incorporates several major components of previous canceled NASA programs and missions, including the Constellation program and the Asteroid Redirect Mission. Originally legislated by the NASA Authorization Act of 2005, Constellation included the development of Ares I, Ares V, and the Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle. The program ran from the early 2000s until 2010.[21]

In May 2009, President Barack Obama established the Augustine Committee to take into account several objectives including support for the International Space Station, development of missions beyond low Earth orbit (including the Moon, Mars, and near-Earth objects), and utilization of the commercial space industry within defined budget limits.[22] The committee concluded that the Constellation program was massively underfunded and that a 2020 Moon landing was impossible. Constellation was subsequently put on hold.[23]

On 15 April 2010, President Obama spoke at the Kennedy Space Center, announcing the administration's plans for NASA and cancelling the non-Orion elements of Constellation on the premise that the program had become nonviable.[24] He instead proposed US$6 billion in additional funding and called for development of a new heavy lift rocket program to be ready for construction by 2015 with crewed missions to Mars orbit by the mid-2030s.[25]

On 11 October 2010, President Obama signed into law the NASA Authorization Act of 2010, which included requirements for the immediate development of the Space Launch System as a follow-on launch vehicle to the Space Shuttle, and continued development of a Crew Exploration Vehicle to be capable of supporting missions beyond low Earth orbit starting in 2016, while making use of the workforce, assets, and capabilities of the Space Shuttle program, Constellation program, and other NASA programs. The law also invested in space technologies and robotics capabilities tied to the overall space exploration framework, ensured continued support for Commercial Orbital Transportation Services, Commercial Resupply Services, and expanded the Commercial Crew Development program.[26]

On 30 June 2017, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to re-establish the National Space Council, chaired by Vice-President Mike Pence. The Trump administration's first budget request kept Obama-era human spaceflight programs in place: Commercial Resupply Services, Commercial Crew Development, the Space Launch System, and the Orion spacecraft for deep space missions, while reducing Earth science research and calling for the elimination of NASA's education office.[27]

Redefinition and naming as Artemis

On 11 December 2017, President Trump signed Space Policy Directive 1, a change in national space policy that provides for a U.S.-led, integrated program with private sector partners for a human return to the Moon, followed by missions to Mars and beyond. The policy calls for the NASA administrator to "lead an innovative and sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international partners to enable human expansion across the Solar System and to bring back to Earth new knowledge and opportunities". The effort intends to more effectively organize government, private industry, and international efforts toward returning humans to the Moon, and laying the foundation of eventual human exploration of Mars.[3] Space Policy Directive 1 authorized the lunar-focused campaign. The campaign (later named Artemis) draws upon legacy US spacecraft programs including the Orion space capsule, the Lunar Gateway space station, Commercial Lunar Payload Services, and also creates entirely new programs such as the Human Landing System. The in-development Space Launch System is expected to serve as the primary launch vehicle for Orion, while commercial launch vehicles will launch various other elements of the program.[28]

On 26 March 2019, Vice President Mike Pence announced that NASA's Moon landing goal would be accelerated by four years with a planned landing in 2024.[29] On 14 May 2019, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine announced that the new program would be named Artemis, after the goddess of the Moon in Greek mythology who is the twin sister of Apollo.[28][30] Despite the immediate new goals, Mars missions by the 2030s were still intended as of May 2019[update].[3]

In mid-2019, NASA requested US$1.6 billion in additional funding for Artemis for fiscal year 2020,[31] while the Senate Appropriations Committee requested from NASA a five-year budget profile[32] which is needed for evaluation and approval by Congress.[33][34]

In February 2020, the White House requested a funding increase of 12% to cover the Artemis program as part of its fiscal year 2021 budget. The total budget would have been US$25.2 billion per year with US$3.7 billion dedicated towards a Human Landing System. NASA Chief Financial Officer Jeff DeWit said he thought the agency has "a very good shot" to get this budget through Congress despite Democratic concerns around the program.[2] However, in July 2020 the House Appropriations Committee rejected the White House's requested funding increase.[35] The bill proposed in the House dedicated only US$700 million towards the Human Landing System, 81% (US$3 billion) short of the requested amount.[36]

In April 2020, NASA awarded funding to Blue Origin, Dynetics, and SpaceX for competing 10-month-long preliminary design studies for the HLS.[37][38][39]

Throughout February 2021, Acting Administrator of NASA Steve Jurczyk reiterated those budget concerns when asked about the project's schedule,[40][41] clarifying that "The 2024 lunar landing goal may no longer be a realistic target [...]".[42]

On 4 February 2021, the Biden Administration endorsed the Artemis program.[43] More specifically, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki expressed the Biden administration's "support [for] this effort and endeavor".[44][45][46]

On 16 April 2021, NASA contracted SpaceX to develop, manufacture, and fly two lunar landing flights with the Starship HLS lunar lander.[47] Blue Origin and Dynetics protested the award to the GAO on 26 April.[48][49] After the GAO rejected the protests,[50] Blue Origin sued NASA over the award,[51][52] and NASA agreed to stop work on the contract until 1 November 2021 as the lawsuit proceeded. The judge dismissed the suit on 4 November 2021 and NASA resumed work with SpaceX.[53]

On 25 September 2021, NASA released its first digital, interactive graphic novel in celebration of National Comic Book Day. "First Woman: NASA's Promise for Humanity" is the fictional story of Callie Rodriguez, the first woman to explore the Moon.[54]

In addition to the initial SpaceX contract, NASA awarded two rounds of separate contracts in May 2019[55] and September 2021,[56] on aspects of the HLS to encourage alternative designs, separately from the initial HLS development effort. It announced in March 2022 that it was developing new sustainability rules and pursuing both a Starship HLS upgrade (an option under the initial SpaceX contract) and new competing alternative designs. These came after criticism from members of Congress over lack of redundancy and competition, and led NASA to ask for additional support.[19][57]

Launch

Artemis 1 was originally scheduled for late 2021, but the launch date was pushed back to 29 August 2022.[58] Engine sensor problems caused a delay on that date; the next launch window was September 3.[59] A fuel supply line leak in a quick disconnect arm on a ground tail service mast caused a further delay to a period between 23 September and 4 October.[60][61][62] While the leak was partially repaired to a satisfactory condition, weather delays due to Hurricane Ian forced NASA managers to begin preparing for the stack's rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building and call off the September–early October launch window.[63][64][65]

As of October 2022[update], NASA launch managers decided on a new launch date of 14 November, with backup options for 16 November and 19 November.[66] As of November 2022[update], NASA launch managers have ruled out the 14 November option and made preparations to secure the SLS at the pad for Tropical Storm Nicole, after which launch is planned for 16 November.[67][5]

On 16 November 2022, at 01:47:44 EST (06:47:44 UTC), Artemis I successfully launched from the Kennedy Space Center.

Supporting programs

Implementation of the Artemis program will require additional programs, projects, and commercial launchers to support the construction of the Gateway, launch resupply missions to the station, and deploy numerous robotic spacecraft and instruments to the lunar surface.[68] Several precursor robotic missions are being coordinated through the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, which is dedicated to scouting and characterization of lunar resources as well as testing principles for in-situ resource utilization.[68][69]

Commercial Lunar Payload Services

In March 2018, NASA established the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program with the aim of sending small robotic landers and rovers mostly to the lunar south pole region as a precursor to and in support of crewed missions.[69][70][71] The main goals include scouting of lunar resources, in situ resource utilization (ISRU) feasibility testing, and lunar science.[72] NASA is awarding commercial providers indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity contracts to develop and fly lunar landers with scientific payloads.[73] The first phase considered proposals capable of delivering at least 10 kg (22 lb) of payload by the end of 2021.[73] Proposals for mid-sized landers capable of delivering between 500 kg (1,100 lb) and 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) of cargo were planned to also be considered for launch beyond 2021.[74]

In November 2018, NASA announced the first nine companies that were qualified to bid on the CLPS transportation service contracts (see list below).[75] On 31 May 2019, three of those were awarded lander contracts: Astrobotic Technology, Intuitive Machines, and OrbitBeyond.[76] On 29 July 2019, NASA announced that it had granted OrbitBeyond's request to be released from obligations under the contract citing "internal corporate challenges".[77]

The first twelve payloads and experiments from NASA centers were announced on 21 February 2019.[78] On 1 July 2019, NASA announced the selection of twelve additional payloads, provided by universities and industry. Seven of these are scientific investigations while five are technology demonstrations.[79]

The Lunar Surface Instrument and Technology Payloads (LSITP) program was soliciting payloads in 2019 that do not require significant additional development. They will include technology demonstrators to advance lunar science or the commercial development of the Moon.[80][81]

In November 2019, NASA added five contractors to the group of companies who are eligible to bid to send large payloads to the surface of the moon under the CLPS program: Blue Origin, Ceres Robotics, Sierra Nevada Corporation, SpaceX, and Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems.[82][83]

In April 2020, NASA selected Masten Space Systems for a follow-on CLPS delivery of cargo to the Moon in 2022.[84][85] On 23 June 2021, Masten Space Systems announced it was delayed until November 2023. Dave Masten, the founder and chief technology officer, blamed the delay on the COVID pandemic and industry-wide supply chain issues.[86]

In February 2021, NASA selected Firefly Aerospace for a CLPS launch to Mare Crisium in mid-2023.[87][88]

VIPER

The VIPER (Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover) is a lunar rover by NASA planned to be delivered to the surface of the Moon in November 2024.[89] The rover will be tasked with prospecting for lunar resources in permanently shadowed areas in the lunar south pole region, especially by mapping the distribution and concentration of water ice. The mission builds on a previous NASA rover concept called Resource Prospector, which was cancelled in 2018.[90]

The VIPER rover is part of the Lunar Discovery and Exploration Program managed by the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters, and it is meant to support the crewed Artemis program.[91] NASA's Ames Research Center is managing the rover project. The hardware for the rover is being designed by the Johnson Space Center, while the instruments are provided by Ames Research Center, Kennedy Space Center, and Honeybee Robotics.[91] As of March 2021[update], the estimated cost of the mission is US$433.5 million.[92]

The VIPER rover will operate near the lunar south pole at Nobile Crater. VIPER is planned to travel several kilometers, collecting data on different kinds of soil environments affected by light and temperature — those in complete darkness, occasional light, and in constant sunlight. Once it enters a permanently shadowed location, it will operate on battery power alone and will not be able to recharge them until it drives to a sunlit area. Its total operation time will be approximately 100 Earth days.

Both the launcher and the lander to be used will be competitively provided through the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) contractors, with Astrobotic delivering the Griffin lander and SpaceX providing the Falcon Heavy launch vehicle.[93]

| Qualification date | Company | Proposed services | Contract award | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | amount US$ millions | |||

| 29 November 2018 |

Astrobotic Technology | Peregrine lander | 31 May 2019 | 79.5[76] |

| Deep Space Systems | Rover; design and development services | [75] | ||

| Draper Laboratory | Artemis-7 lander | [75] | ||

| Firefly Aerospace | Blue Ghost lander | 4 February 2021 | 93.3[87] | |

| Intuitive Machines | Nova-C lander | 31 May 2019 | 77[76] | |

| Lockheed Martin Space | McCandless Lunar Lander | [75] | ||

| Masten Space Systems | XL-1 lander | 8 April 2020 | 75.9[84][75] | |

| Moon Express | MX-1, MX-2, MX-5, MX-9 landers; sample return. | [75] | ||

| OrbitBeyond | Z-01 and Z-02 landers | 31 May 2019 | 97 [76][c] | |

| 18 November 2019 |

Blue Origin | Blue Moon lander | [83] | |

| Ceres Robotics | [83] | |||

| Sierra Nevada Corporation | [83] | |||

| SpaceX | Starship cargo lander | [83] | ||

| Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems | [83] | |||

International contractors

| Name | Country | Location | Program element | Services performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ispace | Tokyo | Lunar in situ resource utilization | Hakuto-R lunar regolith transfer[95] | |

| Ispace Europe | Luxembourg City | Lunar in situ resource utilization | Lunar regolith transfer[96] | |

| Toyota | Toyota City | Crewed lunar rover | Lunar Cruiser[97] | |

| ArianeGroup | Gironde | Orion | Propulsion system components[98] | |

| ESAB | Laxå Municipality | Space Launch System | Fuel tank structures[99] | |

| MT Aerospace | Augsburg | Space Launch System | Cryogenic core stage dome core panels[100] | |

| Schaeffler Aerospace Germany GmbH & Co. KG | Schweinfurt | Space Launch System | Cronidur 30 in SLS propulsion systems, components for Orion spacecraft[101] | |

| Magna Steyr | Graz | Space Launch System | Pressurization lines for the SLS core stage[102] | |

| Airbus | Bremen | Orion | Orion European Service Module[103] | |

| 7 Sisters Consortium (includes Fleet Space Technologies[104], OZ Minerals, University of Adelaide[105], University of New South Wales, and Unearthed) | Adelaide, Perth, Sydney | Lunar exploration support | Companion program to Artemis to provide nanosatellite solutions and exploration support for crewed Artemis missions.[106] | |

| MDA | Brampton, Ontario | Lunar Gateway | Canadarm 3[107] |

Artemis Accords

On 5 May 2020, Reuters reported that the Trump administration was drafting a new international agreement outlining the laws for mining on the Moon.[108] NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine officially announced the Artemis Accords on 15 May 2020. It consists of a series of bilateral agreements between the governments of participating nations in the Artemis program "grounded in the Outer Space Treaty of 1967".[109][110] The Artemis Accords have been criticized by some American researchers as "a concerted, strategic effort to redirect international space cooperation in favor of short-term U.S. commercial interests".[111] The Accords were signed by the United States, Australia, Canada, Japan, Luxembourg, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates on 13 October 2020,[111] and later signed by Ukraine.[112][113] In May 2021, South Korea joined as the 10th signatory state of the Artemis Accords,[114] with New Zealand following later the same month. Brazil became the 12th signatory country in June 2021. Poland became the 13th signatory country in October 2021. Mexico signed in December 2021. Israel signed in January 2022, Romania and Singapore in March 2022,[115] Colombia signed in May 2022,[116] France signed in June 2022,[117] followed by Saudi Arabia in July 2022.[118]

Exploration Ground Systems (EGS)

The Exploration Ground Systems (EGS) Program is one of three NASA programs based at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. EGS was established to develop and operate the systems and facilities necessary to process and launch rockets and spacecraft during assembly, transport, and launch.[119] EGS is preparing the infrastructure to support NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and its payloads, such as the Orion spacecraft for Artemis 1.[120][121]

Gateway Logistics Services

The Lunar Gateway is a station set to be constructed in lunar orbit, and the Gateway Logistics Services program will provide cargo and other supplies to the station, even when crews are not present. As of 2022[update], only SpaceX's supply vehicle, known as Dragon XL, is planned to supply the Gateway. Dragon XL is a version of the Dragon spacecraft, to be launched by the Falcon Heavy. Unlike Dragon 2 and its predecessor, it is intended to be an expendable spacecraft.

Launch vehicles

As of the early mission concepts outlined by NASA in May 2020 and refined by the HLS contract award in July 2021, launch vehicles planned to be used will include the NASA Space Launch System for Orion, SpaceX Starship for the HLS,[122] and Falcon Heavy for Gateway components,[123] as well as launch vehicles that are contracted for the various CLPS cargo providers. The European Ariane 6 was also proposed to be part of the program in July 2019.[124]

The Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) module and the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) of the Gateway, which were previously planned for the SLS Block 1B,[125] will now fly together on a Falcon Heavy in November 2024.[126][127] The Gateway will be supported and resupplied by approximately 28 commercial cargo missions launched by undetermined commercial launch vehicles.[128] The Gateway Logistics Services (GLS) will be in charge of the resupply missions.[128] GLS has also contracted for the construction of a resupply vehicle, Dragon XL, capable of remaining docked to the Gateway for one year of operations, providing and generating its own power while docked, and capable of autonomous disposal at the end of its mission.[128][129][130]

In May 2019, the plan was for components of a crewed lunar lander to be deployed to the Gateway on commercial launchers before the arrival of the first crewed mission, Artemis 3.[131] An alternative approach where the HLS and Orion dock together directly was discussed.[132][133]

As late as mid-2019, NASA considered use of Delta IV Heavy and Falcon Heavy to launch a crewed Orion mission given SLS delays.[134]. Given the complexity of conversion to a different vehicle, the agency ultimately decided to use only the SLS to launch astronauts.[8]

| Launch vehicle |

Missions | Payload | Estimated cost per launch |

First launch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEO | TLI | ||||

| SLS Block 1 | Crew transportation | 95 t | 27 t | US$2 billion | 16 November 2022, 6:47 UTC[67][5] |

| SLS Block 1B | Crew transportation, I-HAB Gateway Module |

105 t | 42 t | US$2 billion | In development (2026) |

| SLS Block 2 | Crew transportation, Heavy payloads |

130 t | 45 t | US$2 billion | In development (after 2029) |

| Falcon Heavy | Dragon XL launches, two Gateway modules, VIPER |

63.8 t | US$150 million (expendable)[135] |

2018 | |

| Vulcan Centaur | CLPS missions | 27.2 t | 12.1 t | US$82–200 million | In development (2022) |

| Falcon 9 | CLPS missions | 22.8 t | US$62 million[136] | 2010 | |

| Electron | CAPSTONE | 0.3 t | US$7.5 million[137][138] | 2017 | |

| Starship | Starship HLS, heavy CLPS payloads |

100–150 t | US$2 million (goal)[139] | Under construction (2022) | |

| Ariane 6 | Heracles | 21.6 t | EU€115 million[140][141] | In development (2023) | |

Space Launch System

The Space Launch System (SLS) is a United States super heavy-lift expendable launch vehicle, which has been under development since its announcement in 2011. The SLS is the main launch vehicle of the Artemis lunar program, as of March 2021[update]. NASA is required by the U.S. Congress to utilize SLS Block 1, which will be powerful enough to lift a payload of 95 t (209,000 lb) to low Earth orbit (LEO), and will launch Artemis 1, 2, and 3.[citation needed] Starting in 2027, Block 1B is intended to debut the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) and launch the notional Artemis 4-7.[142][full citation needed] Starting in 2029, Block 2 is planned to replace the initial Shuttle-derived boosters with advanced boosters and would have a LEO capability of more than 130 t (130 long tons; 140 short tons), again as required by Congress.[143] Block 2 is intended to enable crewed launches to Mars.[7] The SLS will launch the Orion spacecraft and use the ground operations capabilities and launch facilities at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

In March 2019, the Trump Administration released its Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Request for NASA. This budget did not initially include any money for the Block 1B and Block 2 variants of SLS, but later a request for a budget increase of $1.6 billion towards SLS, Orion, and crewed landers was made. Block 1B is currently intended to debut on Artemis 4 and will be used mainly for co-manifested crew transfers and logistics rather than constructing the Gateway as initially planned. An uncrewed Block 1B was planned to launch the Lunar Surface Asset in 2028, the first lunar outpost of the Artemis program, but now that launch has been moved to a commercial launcher.[18] Block 2 development will most likely start in the late 2020s after NASA is regularly visiting the lunar surface and shifts focus towards Mars.[144]

In October 2019, NASA authorized Boeing to purchase materials in bulk for more SLS rockets ahead of the announcement of a new contract. The contract was expected to support up to ten core stages and eight Exploration Upper Stages for the SLS 1B to transfer heavy payloads of up to 40 metric tons on a lunar trajectory.[145]

SpaceX Starship

The SpaceX Starship system is a super heavy-lift launch system consisting of a booster named Super Heavy and a second stage named Starship. Starship is both a second stage and a spacecraft. The booster and most variants of the spacecraft are fully reusable. The system will be used to launch Starship HLS to LEO as its second stage. Super Heavy will also be used for multiple fueling missions, launching fully reusable tanker Starship spacecraft to LEO to refuel Starship HLS for its transit to the Gateway. Thus, each Starship HLS that is delivered to the Gateway will require multiple launches. It is also qualified to be bid for CLPS launches.

Falcon Heavy

The SpaceX Falcon Heavy is a partially reusable heavy-lift launcher. It will be used to launch the first two Gateway modules into NRHO.[146] It will also be used to launch the Dragon XL spacecraft on supply missions to Gateway,[147] and it is qualified to be bid for other launches under the CLPS program. It was selected under CLPS to launch the VIPER mission.

CLPS launchers

Under the CLPS program, qualified CLPS vendors can use any launcher that meets their mission requirements.

Spacecraft

Orion

Orion is a class of partially reusable spacecraft to be used in the Artemis program. The spacecraft consists of a Crew Module (CM) space capsule designed by Lockheed Martin and the European Service Module (ESM) manufactured by Airbus Defence and Space. Capable of supporting a crew of six beyond low Earth orbit, Orion is equipped with solar panels, an automated docking system, and glass cockpit interfaces modeled after those used in the Boeing 787 Dreamliner. It has a single AJ10 engine for primary propulsion, and others including reaction control system engines. Although designed to be compatible with other launch vehicles, Orion is primarily intended to launch atop a Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, with a tower launch escape system.

Orion was originally conceived by Lockheed Martin as a proposal for the Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV) to be used in NASA's Constellation program. Lockheed Martin's proposal defeated a competing proposal by Northrop Grumman, and was selected by NASA in 2006 to be the CEV. Originally designed with a service module featuring a new "Orion Main Engine" and a pair of circular solar panels, the spacecraft was to be launched atop the Ares I rocket. Following the cancellation of the Constellation program in 2010, Orion was heavily redesigned for use in NASA's Journey to Mars initiative; later named Moon to Mars. The SLS replaced the Ares I as Orion's primary launch vehicle, and the service module was replaced with a design based on the European Space Agency's Automated Transfer Vehicle. A development version of Orion's CM was launched in 2014 during Exploration Flight Test-1, while at least four test articles were produced. By 2022, three flight-worthy Orion crew modules have been built, with an additional one ordered, for use in the Artemis program; the first of these is due to be launched on Artemis 1. On 30 November 2020, it was reported that NASA and Lockheed Martin had found a failure with a component in one of the Orion spacecraft's power data units but NASA later clarified that it does not expect the issue to affect the Artemis 1 launch date.

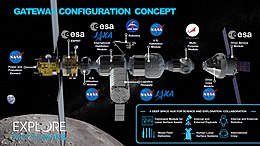

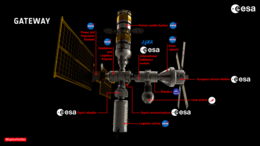

Gateway

NASA's Gateway is an in-development mini-space station in lunar orbit intended to serve as a solar-powered communication hub, science laboratory, short-term habitation module, and holding area for rovers and other robots.[148] While the project is led by NASA, the Gateway is meant to be developed, serviced, and utilized in collaboration with commercial and international partners: Canada (Canadian Space Agency) (CSA), Europe (European Space Agency) (ESA), and Japan (JAXA).

The Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) started development at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory during the now canceled Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM). The original concept was a robotic, high performance solar electric spacecraft that would retrieve a multi-ton boulder from an asteroid and bring it to lunar orbit for study.[149] When ARM was canceled, the solar electric propulsion was repurposed for the Gateway.[150][151] The PPE will allow access to the entire lunar surface and act as a space tug for visiting craft.[152] It will also serve as the command and communications center of the Gateway.[153][154] The PPE is intended to have a mass of 8-9 tonnes and the capability to generate 50 kW[155] of solar electric power for its ion thrusters, which can be supplemented by chemical propulsion.[156]

The Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO),[157][158] also called the Minimal Habitation Module (MHM) and formerly known as the Utilization Module,[159] will be built by Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems (NGIS).[160][161] A single Falcon Heavy equipped with an extended fairing[162] will launch the PPE together with the HALO in November 2024.[126] The HALO is based on a Cygnus Cargo resupply module[160] to the outside of which radial docking ports, body mounted radiators (BMRs), batteries and communications antennae will be added. The HALO will be a scaled-down habitation module,[163] yet, it will feature a functional pressurized volume providing sufficient command, control, and data handling capabilities, energy storage and power distribution, thermal control, communications and tracking capabilities, two axial and up to two radial docking ports, stowage volume, environmental control and life support systems to augment the Orion spacecraft and support a crew of four for at least 30 days.[161]

In March 2020, Doug Loverro, NASA's associate administrator for human exploration and operations at that time, removed the Gateway construction from the 2024 critical path to clear up funding for the HLS. He stated that the PPE could face delays and that moving it back to 2026 would allow for a more refined vehicle. It is also worth noting that the international partners on the Gateway would not have their modules ready until 2026. It was made a requirement that all Human Landing System proposals would be capable of free flight without the Gateway.[164]

On 30 April 2020, a key to NASA's vision for a "sustainable" crew presence on or near the Moon, the Gateway station, was announced to be optional, rather than required, in mission planning. NASA officials originally hoped the Gateway would be in position near the Moon in time for the Artemis 3 mission in 2024, allowing elements of the lunar lander to be assembled, or aggregated, at the Gateway before the arrival of astronauts on an Orion crew capsule. Jim Bridenstine told Spaceflight Now, the Artemis 3 mission will no longer go through the Gateway, but NASA is not backing away from the program.[133]

In late October 2020, NASA and European Space Agency (ESA) finalized their agreement to collaborate in the Gateway program. ESA will provide a habitat module in partnership with JAXA (I-HAB) and a refueling module (ESPRIT). In return Europe will have three flight opportunities to launch crew aboard the Orion crew capsule, which they will provide the service module for.[165][166]

Dragon XL

On 27 March 2020, SpaceX revealed the Dragon XL resupply spacecraft designed to carry pressurized and unpressurized cargo, experiments, and other supplies to NASA's planned Gateway under a NASA Gateway Logistics Services (GLS) contract. The equipment delivered by Dragon XL missions could include sample collection materials, spacesuits, and other items astronauts may need on the Gateway and the surface of the Moon, according to NASA. It will launch on SpaceX's Falcon Heavy launch vehicle from pad LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The Dragon XL is planned to stay at the Gateway for six to 12 months at a time when research payloads inside and outside the cargo vessel could be operated remotely, even when crews are not present. Its payload capacity is expected to be more than 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) to lunar orbit. Unlike previous Dragon variants, the spacecraft will not be reusable and will instead be built solely for transporting cargo. It will act as the United States' logistics vehicle.[167]

Human Landing System

The Human Landing System (HLS) is a critical component of the Artemis mission. This system transports crew from lunar orbit (the Gateway or an Orion spacecraft) to the lunar surface, acts as a lunar habitat, and then transports the crew back to lunar orbit.

Development history

NASA elected to have the HLS designed and developed by commercial vendors. NASA called for proposals, and five vendors responded. In April 2020, NASA awarded three competing design contracts, and in April 2021, NASA selected the Starship HLS to proceed to development and production.

Separately from the design and development program for the first two HLS spacecraft, NASA has multiple smaller contracts to study elements of alternative HLS designs. Eleven contracts were awarded in May 2019 and five were awarded in September 2021.

Starship HLS

The Starship Human Landing System (Starship HLS) was the winner selected by NASA for potential use for long-duration crewed lunar landings as part of NASA's Artemis program.[47][168]

Starship HLS is a variant of SpaceX's Starship spacecraft optimized to operate on and around the Moon. In contrast to the Starship spacecraft from which it derives, Starship HLS will never re-enter an atmosphere, so it does not have a heat shield or flight control surfaces. In contrast to other proposed HLS designs that used multiple stages, the entire spacecraft will land on the Moon and will then launch from the Moon. Like other Starship variants, Starship HLS has Raptor engines mounted at the tail as its primary propulsion system. However, when it is within "tens of meters" of the lunar surface during descent and ascent, it will use high-thrust meth/ox RCS thrusters located mid-body instead of the Raptors to avoid raising dust via plume impingement. A solar array located on the nose below the docking port provides electrical power. Elon Musk stated that Starship HLS would be able to deliver "potentially up to 200 tons" to the lunar surface.

Starship HLS would be launched to Earth orbit using the SpaceX Super Heavy booster, and would use a series of tanker spacecraft to refuel the Starship HLS vehicle in Earth orbit for lunar transit and lunar landing operations. Starship HLS would then boost itself to lunar orbit for rendezvous with Orion. In the mission concept, a NASA Orion spacecraft would carry a NASA crew to the lander, where they would depart and descend to the surface of the Moon. After lunar surface operations, Starship HLS would lift off from the lunar surface acting as a single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) vehicle and return the crew to Orion.

HERACLES lander

HERACLES (Human-Enhanced Robotic Architecture and Capability for Lunar Exploration and Science) is a planned ESA-JAXA-CSA space cargo transport system that will feature a robotic lunar lander called the European Large Logistic Lander (EL3),[169] which can be configured for different operations such as up to 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) of payload,[170] sample-returns, or prospecting resources found on the Moon.[171] ESA approved the project in November 2019.[170][172][173] Its first mission is envisioned for launch in the mid to late 2020s aboard an Ariane 6.[174][169]

The EL3 lander will be launched directly to the Moon and will have a landing mass of approximately 1,800 kg (4,000 lb).[175] It will be capable of transporting a Canadian robotic rover to explore, prospect potential resources, and load samples up to 15 kg (33 lb) on the ascent module.[176] The rover would then traverse several kilometers across the Schrödinger basin on the far side of the Moon to explore and collect more samples to load on the next EL3 lander.[177][175] The ascent module would return each time to the Gateway, where it would be captured by the Canadian robotic arm and samples transferred to an Orion spacecraft for transport to Earth with returning astronauts.[178][179]

Astronauts

On 10 January 2020, NASA's 22nd astronaut group, nicknamed the "Turtles", graduated and were assigned to the Artemis program. The group includes two Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronauts. The group earned their nickname from the prior astronaut group, "The 8-Balls", as is a tradition dating back to "The Mercury Seven" in 1962 which subsequently provided the "Next Nine" with their nickname. They were given this name, for the most part, because of Hurricane Harvey. Some of the astronauts will fly on the Artemis missions to the Moon and may be part of the first crew to fly to Mars.[180]

Artemis team 1

On 9 December 2020, Vice President Mike Pence announced the first group of 18 astronauts (all American, including 9 male and 9 female from different backgrounds), the 1st Artemis team, who could be selected as astronauts of early missions of the Artemis program:[181]

Chief Astronaut Reid Wiseman said in August 2022, however, that all 42 active members of the NASA Astronaut Corps, and the ten more training as NASA Astronaut Group 23, are eligible for Artemis 2 and later flights.[182]

Planned surface operations

As of February 2020, a lunar stay during a Phase 1 Artemis mission will be about seven days and will have five extravehicular activities (EVA). A notional concept of operations (i.e., a hypothetical but possible plan) would include the following: On Day 1 of the stay, astronauts touchdown on the Moon but do not conduct an EVA. Instead, they prepare for the EVA scheduled for the next day in what is referred to as "The Road to EVA". On Day 2, the astronauts open the hatch on the Human Landing System and embark on EVA 1 which will be six hours long. It will include collecting a contingency sample, conducting public affairs activities, deploying the experiment package, and acquiring samples. The astronauts will stay close to the landing site on this first EVA. EVA 2 begins on day 3. The astronauts characterize and collect samples from permanently shadowed regions. Unlike the previous EVA, the astronauts will go farther from the landing site, up to 2 kilometres (1.2 mi), and up and down slopes of 20°. Day 4 will not include an EVA but Day 5 will. EVA 3 may include activities such as collecting samples from an ejecta blanket. Day 6 will have the two astronauts deploy a geotechnical instrument alongside an environmental monitoring station for in-situ resource utilization (ISRU). Day 7 will have the final and shortest EVA; this EVA will only last one hour rather than the others' six hours in duration from egress to ingress and mostly comprises preparations for the lunar liftoff, including jettisoning hardware. Once the final EVA is concluded, the astronauts will return into the Human Landing System and the vehicle will launch from the surface and join up with Orion/Gateway.[183]

Artemis Base Camp

Artemis Base Camp is the prospective lunar base that was proposed to be established at the end of the 2020s. It would consist of three main modules: the Foundational Surface Habitat, the Habitable Mobility Platform, and the Lunar Terrain Vehicle. It would support missions of up to two months and be used to study technologies to use on Mars. The idea would be to build upon this initial base site for decades through both Government and commercial programs. Currently Shackleton Crater is the prime target for this outpost due to its wide variety of lunar geography and water ice. It would fall under the guidelines of the Outer Space Treaty.[184][185]

Foundational Surface Habitat

Little is known about the surface outpost with most information coming from studies and launch manifests that include its launch. It would be commercially built and possibly commercially launched in 2028 along with the Mobile Habitat.[186] The first habitat is referred to as the Artemis Foundation Habitat formerly the Artemis Surface Asset. Current launch plans show that landing it on the surface would be similar to the HLS. The pressurized habitat would be sent to the Gateway where it would then be attached to a descent stage separately launched from a commercial launcher, it would utilize the same transfer stage used for the HLS. Other designs from 2019 see it being launched from an SLS Block 1B as a single unit and landing directly on the surface. It would then be hooked up to a surface power system launched by a CLPS mission and tested by the Artemis 6 crew. The location of the base would be in the south pole region and most likely be a site visited by prior crewed and robotic missions.[184][187]

Habitable Mobility Platform

The Habitable Mobility Platform would be a large pressurized rover used to transport crews across large distances. NASA has developed multiple pressurized rovers including the Space Exploration Vehicle built for the Constellation program which was fabricated and tested. In the 2020 flight manifest it was referred to as the Mobile Habitat suggesting it could fill a similar role to the ILREC Lunar Bus. It would be ready for the crew to use on the surface but could also be autonomously controlled from the Gateway or other locations. Mark Kirasich, who is the acting director of NASA's Advanced Exploration Systems, has stated that the current plan is to partner with JAXA and Toyota to develop a closed cabin rover to support crews for up to 14 days (currently known as Lunar Cruiser). "It's very important to our leadership at the moment to involve JAXA in a major surface element", he said. "... The Japanese, and their auto industry, have a very strong interest in rover-type things. So there was an idea to — even though we have done a lot of work — to let the Japanese lead development of a pressurized rover. So right now, that's the direction we're heading in". In regards to the SEV, Senior Lunar Scientist Clive Neal said "Under Constellation NASA had a sophisticated rover put together, It's pretty sad if it's never going to get to the Moon". but also said that he understands the different scopes of the Constellation Program and Artemis program and the focus on international collaboration.[184][188][189][190][191]

Lunar Terrain Vehicle

In February 2020, NASA released two requests for information regarding both a crewed and uncrewed unpressurized surface rover. The LTV would be propositioned by a CLPS vehicle before the Artemis 3 mission. It would be used to transport crews around the exploration site. It would serve a similar function as the Apollo Lunar Rover. In July 2020, NASA will move to formally establish a program office for the rover at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.[184][needs update]

Space suits

The Artemis program will make use of two types of space suit revealed in October 2019: the Exploration Extravehicular Mobility Unit (xEMU),[192] and the Orion Crew Survival System (OCSS).[193]

On 10 August 2021, a NASA Office of Inspector General audit reported a conclusion that the spacesuits would not be ready until April 2025 at the earliest, likely delaying the mission from the planned late 2024.[194] In response to the IG report, SpaceX indicated that they could provide the suits.[195]

Commercial spacesuits

NASA published a draft RFP to procure commercially-produced spacesuits in order to meet the 2024 schedule. [196] On 2 June 2022, NASA announced that commercially produced spacesuits would be developed by Axiom Space and Collins Aerospace.[197]

Artemis flights

Orion testing

A prototype version of the Orion Crew Module was launched on Exploration Flight Test-1 on 5 December 2014[198][199] atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket. Its reaction control system and other components were tested during two medium Earth orbits, reaching an apogee of 5,800 km (3,600 mi) and crossing the Van Allen radiation belts before making a high-energy reentry at 32,000 km/h (20,000 mph).[200][201]

The Ascent Abort-2 test on 2 July 2019 tested the final iteration of the launch abort system on a 10,000 kg (22,000 lb) Orion boilerplate at maximum aerodynamic load,[202][203][204] using a custom Minotaur IV-derived launch vehicle built by Orbital ATK.[204][205]

Planned missions

As of December 2020[update], all crewed Artemis missions launched on the Space Launch System from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39B. Current plans call for some supporting hardware to be launched on other vehicles and from other launch pads.

| Mission | Patch | Launch date | Crew | Launch vehicle | Duration | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemis I | 16 November 2022[67][5] | — | SLS Block 1 Crew | ≈42 days | Uncrewed lunar orbit and return | |

| Artemis II | To be designed by the crew | May 2024[6] | TBA | SLS Block 1 Crew | ≈10 days | 4-person lunar flyby |

| Artemis III | To be designed by the crew | 2025[6] | TBA | Starship HLS | ≈30 days | 4-person lunar orbit with 2-person lunar landing |

| Artemis IV | To be designed by the crew | 2027[17] | TBA | SLS Block 1B Crew | ≈30 days | 4-person lunar orbit and delivery of the I-HAB module to the Lunar Gateway.[206] |

| Artemis V | To be designed by the crew | 2028[17][207] | TBA | SLS Block 1B Crew | ≈30 days | Lunar landing with the Lunar Terrain Vehicle and delivery of the ESPRIT Refueling Module to the Lunar Gateway.[208] |

| Artemis VI | To be designed by the crew | 2029[209] | TBA | SLS Block 1B Crew | ≈30 days | Lunar landing with the delivery of the Gateway Airlock Module[208] |

Proposed missions

A proposal curated by William H. Gerstenmaier before his 10 July 2019 reassignment[210] suggested four launches of the SLS Block 1B launch vehicle with crewed Orion spacecraft and logistics modules to the Gateway between 2024 and 2028.[211][212] In November 2021, plans to return humans to the Moon in 2024 were cancelled, and the Artemis 3 mission was delayed until at least 2025.[213] However, as of October 2021[update], plans remained in place for crewed Artemis V through IX missions to launch yearly between 2027 and 2031,[214][18] testing in situ resource utilization and nuclear power on the lunar surface with a partially reusable lander. Artemis VII would deliver in 2029[214] a crew of four astronauts to a Surface lunar outpost known as the Foundation Habitat along with the Mobile Habitat.[18] The Foundation Habitat would be launched back to back with the Mobile Habitat by an undetermined super heavy launcher[18] and would be used for extended crewed lunar surface missions.[18][215][216] Prior to each crewed Artemis mission, various payloads to the Gateway, such as refueling depots and expendable elements of the lunar lander, would be deployed by commercial launch vehicles.[212][216] The most updated manifest includes missions suggested in NASA's timelines that have not been designed or funded from Artemis IV-IX.[214][217][18][186]

| Mission | Launch date | Crew | Launch vehicle | Duration | Goal (proposed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemis VII | 2030[209] | TBA | SLS Block 1B Crew | ≈30 days | Lunar landing with the delivery of Habitable Mobility Platform to surface |

| Artemis VIII | 2031[209] | TBA | SLS Block 1B Crew | ≈60 days | Lunar landing with the delivery of lunar surface logistics |

| Artemis IX | 2032 | TBA | SLS Block 2 Crew | ≈60 days | Lunar landing with the delivery of the Foundational Surface Habitat |

| Artemis X | 2033 | TBA | SLS Block 2 Crew | ≈60 days | Lunar landing with the delivery of lunar surface logistics |

| Artemis XI | 2034 | TBA | SLS Block 2 Crew | ≈60 days | Delivery of lunar surface logistics |

Support missions

| Date | Mission objective | Mission name | Launch vehicle | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 June 2022[218] | NRHO Pathfinder mission CAPSTONE[219] | CAPSTONE | Electron | Operational |

| March 2023[220] | First launch of the Nova-C lunar lander by Intuitive Machines[123] | IM-1 | Falcon 9 | Planned |

| Q1 2023[221] | First launch of the Peregrine lunar lander by Astrobotic[222] | Peregrine Mission One | Vulcan Centaur[223] | Planned |

| November 2023 | Tools for mapping the lunar surface temperature, radiation, and hydrogen delivered by Masten Space Systems via their XL-1 lander. | Masten Mission One[224] | Falcon 9[225] | Planned |

| 2023[226] | ISRU tech demonstration converting lunar ice to H2O using Nova-C | PRIME-1[227] | Falcon 9[228] | Planned |

| 2023 | Fuel Cells Demo 1 delivered to surface via CLPS lander[186] | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Planned |

| 2023 | Delivery of Starship HLS for uncrewed HLS Demo landing mission | Artemis HLS Demo | Starship | Planned |

| 2024 | Delivery of the Lunar Terrain Vehicle ahead of Artemis III[229] | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Planned |

| November 2024[89] | Delivery of NASA's VIPER rover on the Griffin lunar lander to the lunar surface by Astrobotic Technology[230] | VIPER | Falcon Heavy[231] | Planned |

| November 2024[126] | Launch of the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) and the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) as an integrated assembly. First two Lunar Gateway modules. | Artemis support mission | Falcon Heavy | Planned |

| 2025 | Delivery of Starship HLS for Artemis III | Artemis HLS 1 | Starship | Planned |

| 2025 | ISRU Subsystems, lunar regolith to O2, performed by crew on surface | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Planned |

| 2027 | (Proposed) Moon landing support mission(s) for Artemis IV | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Proposed |

| 2027 | Fuel Cells Demo 2 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Planned |

| 2028 | (Proposed) Moon landing support mission(s) for Artemis V | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Proposed |

| 2029 | (Proposed) Moon landing support mission(s) for Artemis VI | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Proposed |

| 2029 | Cryo Fluid Management Systems | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Planned |

| 2029 | Surface power crew demonstration mission | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Planned |

| 2029 | (Proposed) delivery of a Gateway station module | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Proposed |

| 2030 | (Proposed) Moon landing support mission(s) for Artemis VII | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Proposed |

| 2030 | (Proposed) delivery of the Foundation Habitat to the lunar south pole[186] | Artemis support mission | Space Launch System Block 1B / 2[citation needed] | Proposed |

| 2030 | (Proposed) delivery of the JAXA closed cabin rover to the lunar south pole | Artemis support mission | Space Launch System Block 1B / 2[citation needed] | Proposed |

| 2031 | (Proposed) Moon landing support mission(s) for Artemis VIII | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Proposed |

| 2032 | (Proposed) Moon landing support mission(s) for Artemis IX | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicle | Proposed |

Criticism

The Artemis program has received criticisms from several space professionals.

Mark Whittington, who is a contributor to The Hill and an author of several space exploration studies, stated in an article that the "lunar orbit project doesn't help us get back to the Moon".[232]

Aerospace engineer, author, and Mars Society founder Robert Zubrin has voiced his distaste for the Gateway which is part of the Artemis program as of 2020. He presented an alternative approach to a 2024 crewed lunar landing called "Moon Direct", a successor to his proposed Mars Direct. His vision phases out the SLS and Orion, replacing them with the SpaceX launch vehicles and SpaceX Dragon 2. It also proposes using a heavy ferry/lander that would be refueled on the lunar surface via in situ resource utilization and transfer the crew from LEO to the lunar surface. The concept bears a heavy resemblance to NASA's own Space Transportation System proposal from the 1970s.[233]

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin disagrees with NASA's current goals and priorities, including their plans for a lunar outpost. He also questioned the benefit of the idea to "send a crew to an intermediate point in space, pick up a lander there and go down". However, Aldrin expressed support for Robert Zubrin's "Moon Direct" concept which involves lunar landers traveling from Earth orbit to the lunar surface and back.[234]

House Authorization Bill of 2020

The leadership of the House Science Committee introduced a bipartisan NASA authorization bill on 24 January 2020 that would significantly alter NASA's current plans to return humans to the Moon and rather would focus on a Mars orbital mission in 2033. Bill H.R. 5666 would change the lunar landing date from 2024 to 2028 and put the program as a whole underneath a larger space exploration plan. The bill became stuck in the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, and there were no committee votes or further action for the remainder of the congressional term. Major proposed changes included:[235][236]

- Creation of a new Moon to Mars program office with a goal of landing humans on Mars "in a sustainable manner as soon as practicable"

- A 2028 target date for a lunar landing to allow the technology to mature

- A NASA developed expendable Human Landing System (HLS), something along the line of the Advanced Exploration Lander or the expendable Altair design

- Launching both the Orion and HLS on SLS 1B rockets rather than splitting them between SLS and a commercial vehicle

- The requirement of one uncrewed and one crewed test flight of the HLS before a lunar landing is attempted, something not currently required

- Once operational, the system would perform two lunar landings a year rather than one

- No base would be set up on the lunar surface rather, the missions would follow the "flag and footsteps" approach of Apollo

- Development of the Gateway as a separate program to test Mars transportation technologies and not be required for lunar operations

- ISRU technologies would be managed under a program separate from the Moon to Mars campaign and not be required for either mission

- International Space Station funding would be extended to 2030

Many of these changes, such as uncrewed HLS test flights[237] and the development of the Gateway as no longer essential to Artemis,[238] were implemented into the current timeline.

Gallery

-

Planned missions of Artemis program

-

Phase 1 Gateway with an Orion and HLS docked on Artemis 3

-

Concept of surface operations

-

Artemis I planned flight path

See also

- Apollo program – 1961–1972 American crewed lunar exploration program

- Chinese Lunar Exploration Program – Chinese crewed lunar program with international partners e.g. Russia.

- Colonization of the Moon – Settlement on the Moon

- Commercial Crew Development – NASA space program partnership with space companies

- Deep Space Transport – Crewed interplanetary spacecraft concept

- First Lunar Outpost – Crewed lunar program proposal from the SEI

- International Lunar Resources Exploration Concept – Lunar exploration concept

- List of crewed spacecraft

- NASA Astronaut Group 23

- Space policy of the United States

Notes

- ^ An Orion Capsule was flown in 2014, but not the entire Orion spacecraft.

- ^ If an ancillary mission has already delivered Gateway to NRHO, HLS and Orion will dock to Gateway instead of to each other.

- ^ On 29 Jul 2019, NASA accepted a request for contract termination from OrbitBeyond given its identification of internal corporate challenges[94]

References

- ^ Moran, Norah (29 January 2021). "Ep 180: Artemis Mission Management". NASA. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ a b Berger, Eric (11 February 2020). "NASA puts a price on a 2024 Moon landing — US$35 billion". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ a b c

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "NASA: Moon to Mars". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "NASA: Moon to Mars". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Artemis I Launch to the Moon (Official NASA Broadcast) - Nov. 16, 2022, retrieved 16 November 2022

- ^ a b c d "NASA Prepares Rocket, Spacecraft Ahead of Tropical Storm Nicole, Re-targets Launch". NASA. 8 November 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Foust, Jeff (9 November 2021). "NASA delays human lunar landing to at least 2025". SpaceNews. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ a b Gebhardt, Chris (6 April 2017). "NASA finally sets goals, missions for SLS — multi-step plan to Mars". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ a b Grush, Loren (18 July 2019). "NASA's daunting to-do list for sending people back to the Moon". The Verge. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "NASA: Artemis Accords". NASA. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (10 December 2021). "Mexico joins Artemis Accords". SpaceNews. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "NASA's management of the Artemis missions" (PDF). NASA Office of Inspector General. 15 November 2021. "What We Found" section at 3th and 4th page. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Davis, Jason (11 June 2019). "NASA's Artemis program will return astronauts to the moon and give us the first female moonwalker". NBC News. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (18 May 2020). "NASA will likely add a rendezvous test to the first piloted Orion space mission". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ a b Latifiyan, Pouya (August 2022). "Artemis 1 and space communications". Qoqnoos Scientific Magazine. 1: 4.

- ^ Sloss, Philip (31 May 2021). "NASA evaluating schedule, launch date forecasts for Artemis 2". NASASpaceFlight. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (21 July 2019). "NASA outlines plans for lunar lander development through commercial partnerships". SpaceNews. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Foust, Jeff (30 October 2022). "Lunar landing restored for Artemis 4 mission". SpaceNews. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Forward to the Moon: NASA's Strategic Plan for Human Exploration" (PDF). NASA. 4 September 2019 [Updated 9 April 2019]. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Forward to the Moon: NASA's Strategic Plan for Human Exploration" (PDF). NASA. 4 September 2019 [Updated 9 April 2019]. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ a b McGuinness, Jackie; Russell, Jimi; Sudnik, Janet; Potter, Sean (23 March 2022). "NASA Provides Update to Astronaut Moon Lander Plans Under Artemis". NASA. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "The Space Review: A second chance at the Moon". www.thespacereview.com. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Moskowitz, Clara (7 January 2011). "NASA Stuck in Limbo as New Congress Takes Over". Space.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Bonilla, Dennis (8 September 2009). "Charter of the Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee". NASA. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Bonilla, Dennis (8 September 2009). "Charter of the Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee". NASA. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (11 October 2010). "Obama signs Nasa up to new future". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee; Augustine; Austin; Chyba; et al. "Seeking A Human Spaceflight Program Worthy of A Great Nation" (PDF). Final Report. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee; Augustine; Austin; Chyba; et al. "Seeking A Human Spaceflight Program Worthy of A Great Nation" (PDF). Final Report. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "President Barack Obama on Space Exploration in the 21st Century". NASA. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "President Barack Obama on Space Exploration in the 21st Century". NASA. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "S.3729 - National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2010". United States Congress. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "S.3729 - National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2010". United States Congress. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (30 June 2017). "Trump signs order reviving long-dormant National Space Council". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b Grush, Loren (17 May 2019). "NASA administrator on new Moon plan: "We're doing this in a way that's never been done before"". The Verge. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert (14 May 2019). "NASA Names New Moon Landing Program Artemis After Apollo's Sister". Space.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (13 May 2019). "For Artemis Mission to Moon, NASA Seeks to Add Billions to Budget". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Harwood, William (17 July 2019). "NASA boss pleads for steady moon mission funding". CBS News. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "Senate appropriators advance bill funding NASA despite uncertainties about Artemis costs". SpaceNews. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Fernholz, Tim (14 May 2019). "Trump wants US$1.6 billion for a Moon mission and proposes to get it from college aid". Quartz. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Berger, Eric (14 May 2019). "NASA reveals funding needed for Moon program, says it will be named Artemis". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Appropriations Committee Releases Fiscal Year 2021 Commerce-Justice-Science Funding Bill". 7 July 2020. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Appropriations Committee Releases Fiscal Year 2021 Commerce-Justice-Science Funding Bill". 7 July 2020. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "House bill offers flat funding for NASA". SpaceNews. 7 July 2020. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Burghardt, Thomas (1 May 2020). "NASA Selects Blue Origin, Dynetics, and SpaceX Human Landers for Artemis". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Berger, Eric (30 April 2020). "NASA awards lunar lander contracts to Blue Origin, Dynetics and Starship". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Potter, Sean (30 April 2020). "NASA Names Companies to Develop Human Landers for Artemis Missions". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Potter, Sean (30 April 2020). "NASA Names Companies to Develop Human Landers for Artemis Missions". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Bartels, Meghan (5 February 2021). "NASA has a lot to tackle this year as Biden takes charge. Here's what the agency's acting chief has to say". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Feldscher, Jacqueline (16 February 2021). "NASA reassesses Trump's 2024 moon goal". Politico. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (18 February 2021). "Acting NASA chief says 2024 Moon landing no longer a "realistic" target". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "White House endorses Artemis program". SpaceNews. 4 February 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Press Briefing by Press Secretary Jen Psaki and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, February 4, 2021". whitehouse.gov. 4 February 2021. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (5 February 2021). "Artemis: Biden administration backs US Moon shot". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Davenport, Christian (2 March 2021). "The Biden administration has set out to dismantle Trump's legacy, except in one area: Space". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ a b Berger, Eric (16 April 2021). "NASA selects SpaceX as its sole provider for a lunar lander - "We looked at what's the best value to the government."". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Blue Origin protests NASA Human Landing System award". SpaceNews. 26 April 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Dynetics protests NASA HLS award". SpaceNews. 27 April 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (30 July 2021). "GAO denies Blue Origin and Dynetics protests of NASA lunar lander contract". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin sues NASA, escalating its fight for a Moon lander contract". The Verge. 16 August 2021. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

protest prevented SpaceX from starting its contract for 95 days while the GAO adjudicated the case.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (16 August 2021). "Bezos' Blue Origin takes NASA to federal court over award of lunar lander contract to SpaceX". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (4 November 2021). ""Bezos' Blue Origin loses NASA lawsuit over SpaceX $2.9 billion lunar lander contract"". CNBC. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "NASA Releases Interactive Graphic Novel "First Woman"" Archived 26 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine. NASA, September 25, 2021.

- ^ "NASA awards US$45.5 million to 11 American companies to "advance human lunar landers"". mlive.com. 22 May 2019. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "NASA Selects Five U.S. Companies to Mature Artemis Lander Concepts". NASA. 14 September 2021. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Wall, Mike (23 March 2022). "NASA wants another moon lander for Artemis astronauts, not just SpaceX's Starship". Space.com. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (26 April 2022). "NASA's moon rocket rolls back to Vehicle Assembly Building for repairs". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (31 August 2022). "Next Artemis 1 launch attempt set for Sept. 3". SpaceNews. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (3 September 2022). "Second Artemis 1 launch attempt scrubbed". SpaceNews. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ Kraft, Rachel. "Artemis I Launch Attempt Scrubbed". NASA blog. NASA. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (8 September 2022). "NASA discusses path to SLS repairs as launch uncertainty looms for September, October". NASASpaceflight. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Kraft, Rachel (24 September 2022). "Artemis I Managers Wave Off Sept. 27 Launch, Preparing for Rollback – Artemis". NASA Blogs. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ "NASA to Roll Artemis I Rocket and Spacecraft Back to VAB Tonight – Artemis". blogs.nasa.gov. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (26 September 2022). "SLS to roll back to VAB as hurricane approaches Florida". SpaceNews. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "NASA Sets Date for Next Launch Attempt for Artemis I Moon Mission". NASA. 12 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Wattles, Jackie (8 November 2022). "NASA's Artemis I mission delayed again as storm barrels toward launch site". CNN. Warner Bros Discovery. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ a b Burghardt, Thomas (14 May 2019). "NASA aims for quick start to 2024 Moon landing via newly named Artemis Program". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ a b Harwood, William (31 May 2019). "NASA taps three companies for commercial moon missions". CBS News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "NASA awards contracts to three companies to land payloads on the moon". SpaceNews. 31 May 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (19 March 2018). "NASA courts commercial options for Lunar Landers". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

NASA's new Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) effort to award contracts to provide capabilities as soon as 2019.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "NASA Expands Plans for Moon Exploration: More Missions, More Science". NASA. 30 April 2018. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "NASA Expands Plans for Moon Exploration: More Missions, More Science". NASA. 30 April 2018. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2018.