Outline of anarchism

Anarchism is a broad category of active ethical, social and political philosophies encompassing theories and attitudes which reject compulsory government[1] (the state) and support its elimination,[2][3] often due to a wider rejection of involuntary or permanent authority.[4] Anarchism is defined by The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics as "a cluster of doctrines and attitudes centered on the belief that government is both harmful and unnecessary."[5]

The following outline is provided as an overview of and introduction to anarchism.

Essence of anarchism

Anarchism promotes a rejection of philosophies, ideologies, institutions, and representatives of authority in support of liberty. It asserts that cooperation is preferable to competition in promoting social harmony; that cooperation is only authentic when it is voluntary; and that societies are capable of spontaneous order, rendering government authority unnecessary at best, or harmful at worst. In most cases, anarchism…

Supports:

Rejects:

Manifestos and expositions of anarchist viewpoints

Template:Details3 Anarchism is a living project which has continued to evolve as social conditions have changed. The following are examples of anarchist manifestos and essays produced during various time periods, each expressing different interpretations and proposals for anarchist philosophy.

|

(1840–1914) |

(1914–1984)

|

(1985–present)

|

Schools of anarchist thought

Anarchism has many heterogeneous and diverse schools of thought, united by a common opposition to compulsory rule. Anarchist schools are characterized by "the belief that government is both harmful and unnecessary", but may differ fundamentally, supporting anything from extreme individualism to complete collectivism.[5] Regardless, some are viewed as being compatible, and it is not uncommon for individuals to subscribe to more than one.

Schools of thought

Umbrella terms

The following terms do not refer to specific branches of anarchist thought, but rather are generic labels applied to various branches.

History of anarchism

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

Although social movements and philosophies with anarchic qualities predate anarchism, anarchism as a specific political philosophy began in 1840 with the publication of What Is Property? by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. In the following decades it spread from Western Europe to various regions, countries, and continents, impacting local social movements. Anarchism declined in prominence between the early and late 20th century, roughly coinciding with the time period referred to by historians as The short twentieth century. Since the late 1980s, anarchism has begun a gradual return to the world stage.

- 1793 – William Godwin publishes Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, implicitly establishing the philosophical foundations of anarchism.[6]

- 1840 – Pierre-Joseph Proudhon publishes What Is Property? and becomes history's first self-proclaimed anarchist.

- 1864 – International Workingmen's Association founded. Early seeds of split between anarchists and Marxists begin.

- 1871 – Paris Commune takes place. Early anarchists (mutualists) participate.

- 1872 – IWA meets at the Hague Congress. Anarchists expelled by Marxist branch, beginning the anarchist/Marxist conflict.

- 1878 – Max Hödel fails in assassination attempt against Kaiser Wilhelm I. Ushers in era of propaganda of the deed.

- 1882 – God and the State by Mikhail Bakunin is published.

- 1886 – Haymarket affair takes place. Origin of May Day as a worker's holiday. Inspires a new generation of anarchists.

- 1892 – The Conquest of Bread by Peter Kropotkin published. Establishes anarchist communism.

- 1911 – The High Treason Incident leads to the execution of twelve Japanese anarchists; the first major blow against the Japanese anarchist movement.

- 1917 – The Russian Revolution creates first "socialist state." The combination of a Soviet dictatorship in the east, the Red Scare in the west, and the global Cold War, discourage anarchist revolution throughout the following decades.

- 1919-1921 – The Free Territory, the first major anarchist revolution, is established in the Ukraine.

- 1919-1921 – The Palmer Raids effectively cripple the anarchist movement in the United States.

- 1921 – The Communist Party of China is founded. The anarchist movement in China begins slow decline due to communist repression.

- 1929-1931 – The autonomous Shinmin region, the second major anarchist revolution, is established in Manchuria.

- 1936-1939 – The Spanish Revolution, the third and last major anarchist revolution, is established in Catalonia and surrounding areas.

- 1959 – The Cuban Revolution establishes a communist dictatorship. The Cuban anarchist movement is immediately repressed.

- 1999 – Anarchists take part in riots which interrupt the WTO conference in Seattle. Is viewed as part of an anarchist resurgence in the United States.

Basic anarchism concepts

These are concepts which, although not exclusive to anarchism, are significant in historical and/or modern anarchist circles. (It should be noted that the anarchist milieu is philosophically heterogeneous and there is disagreement over which of these concepts should play a role in anarchism.)

Organizations

Notable organizations

Formal anarchist organizational initiatives date back to the mid-1800s. The oldest surviving anarchist organizations include Freedom Press (est. 1886) of England, the Industrial Workers of the World (est. 1905), Anarchist Black Cross (est. 1906), Central Organisation of the Workers of Sweden (est. 1910) and the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (est. 1910) of Spain.

- Jura federation (est. 1870)

- Freedom Press (est. 1886)

- Industrial Workers of the World (est. 1905)

- Anarchist Black Cross (est. 1906)

- Mexican Liberal Party (est. 1906)

- Central Organisation of the Workers of Sweden (est. 1910)

- Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (est. 1910)

- Black Guards (est. 1917)

- International Workers Association (est. 1922)

Structures

Anarchist organizations come in a variety of forms, largely based upon common anarchist principles of voluntary cooperation, mutual aid, and direct action. They are also largely informed by anarchist social theory and philosophy, tending towards horizontalism and decentralization.

Anarchism scholars

Anarchists

Prior to the establishment of Anarchism as a political philosophy, the word "anarchist" was used in political circles as an epithet. The first individual to self-identity as an anarchist and ascribe to it positive connotations was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, in 1840. Since then, the label has continued to be used in both of these senses.

Anarchists, with their inherent rejection of authority, have tended not to assign involuntary power in individuals. With few exceptions, forms of anarchist theory and social movements have been named after their organizational forms or core tenants, rather than after their supposed founders. However, there is a tendency for some anarchists to become leaders and historical figures by virtue of their exposure to public media, through the publishing of books, the propagation of ideas, or in rare cases, by taking part in armed rebellion and revolution.

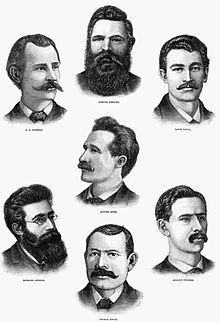

Notable anarchists

The following is a list of anarchists who have made a major impact on the development or propagation of anarchist theory:

Notable non-anarchists

The following is a list of individuals who have influenced anarchist philosophy, despite not being self-identified as anarchists:

Anarchism lists

Related topics

Related philosophies

Footnotes and citations

- ^ Malatesta, Errico, "Towards Anarchism", MAN!. Los Angeles: International Group of San Francisco. OCLC 3930443.

- ^ "Anarchism". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 29 August 2006

- ^ "Anarchism". The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2005. P. 14 "Anarchism is the view that a society without the state, or government, is both possible and desirable."

- ^ Bakunin, Mikhail, God and the State, pt. 2.; Tucker, Benjamin, State Socialism and Anarchism.; Kropotkin, Piotr, Anarchism: its Philosophy and Ideal; Malatesta, Errico, Towards Anarchism; Bookchin, Murray, Anarchism: Past and Present, pt. 4; An Introduction to Anarchism by Liz A. Highleyman

- ^ a b Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ Peter Kropotkin, "Anarchism", Encyclopædia Britannica 1910

External links

- "Anarchism", entry from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, (1910) by Peter Kropotkin.

- "Introductions to anarchism". Spunk Library.

- "The New Anarchists", from New Left Review #13, (2002) by David Graeber.