Mitt Romney

Mitt Romney | |

|---|---|

| |

| 70th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 2, 2003 – January 4, 2007 | |

| Lieutenant | Kerry Healey |

| Preceded by | Jane Swift (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Deval Patrick |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Willard Mitt Romney March 12, 1947 Detroit, Michigan |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Taggart (Tagg) (b. 1970) Matthew (b. 1971) Joshua (b. 1975) Benjamin (b. 1978) Craig (b. 1981) |

| Residence(s) | Belmont, Massachusetts Wolfeboro, New Hampshire San Diego, California |

| Alma mater | Brigham Young University (BA) Harvard University (MBA, JD) |

| Positions | Co-founder, Bain Capital (1984–1998) CEO, Bain & Company (1991–1992) CEO, 2002 Winter Olympics Organizing Committee (1999–2002) |

| Signature | |

| Website | mittromney.com |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Governor of Massachusetts

Presidential campaigns

U.S. Senator from Utah

|

||

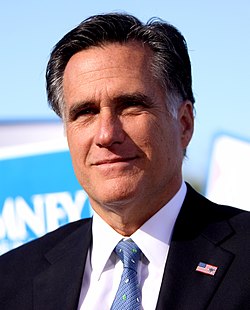

Willard Mitt Romney (born March 12, 1947) is an American businessman and politician. He was the 70th Governor of Massachusetts from 2003 to 2007 and is a candidate for the 2012 Republican Party presidential nomination.

The son of George W. Romney (the former Governor of Michigan) and Lenore Romney, Mitt Romney was raised in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and later served as a Mormon missionary in France. He married Ann Davies in 1969 and they have five children. He received his undergraduate degree from Brigham Young University, and then earned a joint JD and MBA from Harvard University. Romney entered the management consulting business, which led to a position at Bain & Company. Eventually serving as CEO, Romney brought the company out of crisis. He was co-founder and head of the spin-off company Bain Capital, a private equity investment firm that became highly profitable and one of the largest such firms in the nation. His wealth helped fund most of his future political campaigns. Active in his church, he served as ward bishop and later stake president in his area. He ran as the Republican candidate in the 1994 U.S. Senate election in Massachusetts, losing to long-time incumbent Ted Kennedy. Romney organized and steered the 2002 Winter Olympics as head of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee, and helped turn the troubled games into a financial success.

Romney was elected Governor of Massachusetts in 2002 but did not seek re-election in 2006. He presided over a series of spending cuts and increases in fees that eliminated an up to $1.5 billion deficit. He also signed into law the Massachusetts health care reform legislation, which provided near-universal health insurance access via subsidies and state-level mandates and was the first of its kind in the nation. During the course of his political career, his positions or rhetorical emphasis have shifted more towards American conservatism in several areas.

Romney ran for the Republican nomination in the 2008 U.S. presidential election, winning several primaries and caucuses, but eventually losing the nomination to John McCain. In the following years, he gave speeches and raised campaign funds on behalf of fellow Republicans. On June 2, 2011, Romney announced that he would seek the 2012 Republican presidential nomination. The results of the caucuses and primaries so far place him as the leader for the nomination.

Early life and education

Heritage and youth

Romney was born in Detroit, Michigan.[1] He was the youngest child of George W. Romney, who by 1948 had become an automobile executive, and Lenore Romney (née LaFount). His mother was a native of Logan, Utah, and his father had been born in a Mormon colony in Chihuahua, Mexico, to American parents.[2][3][4] Romney is of primarily English descent, and also has more distant Scottish and German ancestry.[5][6][7] Romney is a fifth-generation member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[8][9] A great-great-grandfather, Miles Archibald Romney, converted to the faith in its first decade, and another great-great-grandfather, Parley P. Pratt, was an early leader in the church during the same time.[10][11][12]

The three siblings before him were Margo Lynn, Jane LaFount, and G. Scott,[13] followed by Mitt after a gap of six years.[14] Romney was named after hotel magnate J. Willard Marriott, his father's best friend, and his father's cousin Milton "Mitt" Romney, 1925–1929 quarterback for the Chicago Bears.[13][nb 1] When he was five, the family moved from Detroit to the affluent suburb of Bloomfield Hills.[16] His father became CEO of American Motors and turned the company around from the brink of bankruptcy; by the time he was twelve, his father had become a nationally known figure in print and on television.[17] Romney idolized his father, read automotive trade magazines, kept abreast of automotive developments, and aspired to be an executive in the industry.[16][18][19] His father also presided over the Detroit Stake of the LDS Church.[1]

Romney went to public elementary schools[15] and then from seventh grade on, attended Cranbrook School in Bloomfield Hills, a private boys preparatory school of the classic mold where he was the lone Mormon and where many students came from even more privileged backgrounds.[16][20][21][22] He was not particularly athletic and at first did not excel at academics.[16] While a sophomore, he participated in the campaign in which his father was elected Governor of Michigan.[nb 2] George Romney was re-elected twice; Mitt worked for him as an intern in the governor's office, and was present at the 1964 Republican National Convention when his moderate father battled conservative party nominee Barry Goldwater over issues of civil rights and ideological extremism.[16][18] Romney had a steady set of chores and worked summer jobs, including being a security guard at a Chrysler plant.[20]

Initially a manager for the ice hockey team and a member of the pep squad and various school clubs,[20][23][1] during his final year at Cranbook, Romney joined the cross country running team[15] and improved academically, but was still not a star pupil.[16][21] His social skills were good, however, and he won an award for those "whose contributions to school life are often not fully recognized through already existing channels".[21] Romney was an energetic child who enjoyed pranks.[nb 3]

In March of his senior year, he began dating Ann Davies, two years behind him, whom he had once known in elementary school;[25][26] she attended the private Kingswood School, the sister school to Cranbrook.[21] The two informally agreed to marriage around the time of his June 1965 graduation.[16][26]

University, France mission, marriage and children: 1965–1975

Romney attended Stanford University for a year,[16][nb 4] where he worked as a night security guard to fund secret trips home to see Ann.[27] Although the campus was becoming radicalized with the beginnings of 1960s social and political movements, Romney kept a well-groomed appearance and enjoyed traditional campus events.[16] In May 1966, he was part of a counter-protest against a group staging a sit-in in the university administration building in opposition to draft status tests.[16][28]

"As you can imagine, it's quite an experience to go to Bordeaux and say, 'Give up your wine! I’ve got a great religion for you!'"

—Mitt Romney in 2002 reflecting upon his missionary experience.[29]

In July 1966, Romney left for 30 months in France as a Mormon missionary.[16][30][31] Missionary work was a traditional rite of passage that his father and many other relatives had volunteered for.[nb 5] He arrived in Le Havre with ideas about how to change and promote the French Mission, while facing physical and economic deprivation in their cramped quarters.[31][10] Rules against drinking, smoking, and dating were strictly enforced.[10] Like most individual Mormon missionaries, he did not gain many converts, with the nominally Catholic but secular, wine-loving French people proving especially resistant to a religion that prohibits alcohol.[16][31][10][29] He became demoralized, and later recalled it as the only time when "most of what I was trying to do was rejected."[31] In Nantes, Romney was bruised defending two female missionaries against a horde of local rugby players.[10] He continued to work hard; having grown up in Michigan rather than the more insular Utah world, Romney was better able to interact with the French.[22][10] He was promoted to zone leader in Bordeaux in early 1968, then in the spring of that year became assistant to the mission president in Paris, the highest position for a missionary.[31][10][34] In the Mission Home in Paris he enjoyed palace-like accommodations.[34] Romney's support for the U.S. role in the Vietnam War was only reinforced when the French greeted him with hostility over the matter and he debated them in return.[31][10] He also witnessed the May 1968 general strike and student uprisings.[31]

In June 1968, an automobile Romney was driving in southern France was hit by another vehicle, seriously injuring him and killing one of his passengers, the wife of the mission president.[nb 6] Romney, who was not at fault in the accident,[nb 6] became co-acting president of a mission demoralized and disorganized by the May civil disturbances and by the car accident.[22] Romney rallied and motivated the others and they met an ambitious goal of 200 baptisms for the year, the most for the mission in a decade.[22] By the end of his stint in December 1968, Romney was overseeing the work of 175 fellow members.[31][35] Romney developed a lifelong affection for France and its people, and speaks French.[37] The experience in the country also changed him. It instilled in him a belief that life is fragile and that he needed seriousness of purpose. He gained organizational experience and a record of accomplishments that he had theretofore lacked.[16][22][10][35] It also represented a crucible, after having been only a half-hearted Mormon growing up: "On a mission, your faith in Jesus Christ either evaporates or it becomes much deeper. For me it became much deeper."[31]

While he was away, Ann Davies had converted to the LDS Church, guided by George Romney, and had begun attending Brigham Young University (BYU).[16][26] Romney was nervous that she had been wooed by others while he was away, and she had indeed started dating popular campus figure Kim S. Cameron and had sent Romney in France a "Dear John letter", greatly upsetting him; he wrote to her to in an attempt to win her back.[38][15] At their first meeting following Romney's return they reconnected, and decided to get married in two weeks but agreed to wait three months to appease their parents.[26][39] At Ann's request, Romney began attending Brigham Young too, in February 1969.[38][nb 4] The couple were married on March 21, 1969, in a civil ceremony at Ann's family's home in Bloomfield Hills that was presided over by a church elder.[39][41][42] The following day the couple flew to Utah for a wedding ceremony at the Salt Lake Temple.[39][41]

Romney had missed much of the tumultuous American anti-Vietnam War movement while away, and was surprised to learn that his father had turned against the war during his unsuccessful 1968 presidential campaign.[31] Regarding the military draft, Romney had initially received a student deferment, then like most other Mormon missionaries a ministerial deferment while in France, then another student deferment.[31][43] When those ran out, his high number in the December 1969 draft lottery (300) ensured he would not be selected.[19][31][43][44]

At culturally conservative BYU, Romney continued to be separated from much of the upheaval of the era, and did not join in those protests that did occur against the war or the LDS Church's policy at the time of denying full membership to blacks.[19][31][38] He became president of, and an innovative fundraiser for, the all-male Cougar Club and showed a new-found discipline in his studies.[31][38] In his senior year he took leave to work as driver and advance man for his mother Lenore Romney's eventually unsuccessful 1970 campaign for U.S. Senator from Michigan.[19][39] He earned a Bachelor of Arts in English with highest honors in 1971,[38] and gave commencement addresses to both his own College of Humanities and to the whole university.[nb 7]

The Romneys' first son, Tagg, was born in 1970[39] while the Romneys were undergraduates at Brigham Young[46] and living in a basement apartment.[31][38] Ann subsequently gave birth to Matt (1971), Josh (1975), Ben (1978), and Craig (1981).[39] Ann Romney's work as a homemaker would enable her husband to pursue his career.[47]

Romney still wanted to pursue a business path, but his father, by now serving in President Richard Nixon's cabinet as U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, advised that a law degree would be valuable.[48][49] Thus Romney became one of only fifteen students to enroll at the recently created joint Juris Doctor/Master of Business Administration four-year program coordinated between Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School.[50] Fellow students considered Romney guilelessly optimistic, noting his solid work ethic along with a buttoned-down demeanor and appearance.[50][51] He readily adapted to the business school's pragmatic, data-driven case study method of teaching, participated in class well, and led a study group whom he pushed to get all A's.[49] He had a different social experience from most of his classmates, since he lived in a Belmont, Massachusetts, house with Ann and two children; he was non-ideological and did not involve himself in the political or social issues of the day.[39][49] He graduated in 1975 cum laude from the law school, in the top third of that class, and was named a Baker Scholar for graduating in the top five percent of his business school class.[45][50]

Business career

Management consulting

Romney was heavily recruited and chose to remain in Massachusetts to work for Boston Consulting Group (BCG), thinking that working as a management consultant to a variety of companies would prepare him for a future job as a chief executive.[20][48][52][nb 8] Romney was part of a 1970s wave of top graduates who chose to go into consulting rather than join a major company directly.[54] Romney's legal and business education proved useful in his job, and he became a rising star[48] while applying BCG principles such as the growth-share matrix.[55]

In 1977, he was hired away by Bain & Company, a management consulting firm in Boston that had been formed a few years earlier by Bill Bain and other former BCG employees.[55][48][56] Bain would later say of the thirty-year-old Romney, "He had the appearance of confidence of a guy who was maybe ten years older."[57] With Bain & Company, Romney learned the "Bain way", which consisted of immersing the firm in each client's business,[48][57] and not simply to issue recommendations, but to stay with the company until they were changed for the better.[55][56][58] With a record of helping clients such as the Monsanto Company, Outboard Marine Corporation, Burlington Industries, and Corning Incorporated, Romney became a vice president of the firm in 1978 and within a few years one of its best consultants and one sought after by clients over more senior partners.[15][48][52][59] Romney became a believer in Bain's methods; he later said, "The idea that consultancies should not measure themselves by the thickness of their reports, or even the elegance of their writing, but rather by whether or not the report was effectively implemented was an inflection point in the history of consulting."[56]

Private equity

Romney was restless for a company of his own to run, and in 1983, Bill Bain offered him the chance to head a new venture that would buy into companies, have them benefit from Bain techniques, and then reap higher rewards than just consulting fees.[55][48] Romney initially refrained from accepting the offer, and Bain re-arranged the terms in a complicated partnership structure so that there was no financial or professional risk to Romney.[48][57][60] Thus, in 1984, Romney left Bain & Company to co-found the spin-off private equity investment firm, Bain Capital.[58] In the face of skepticism from potential investors, Bain and Romney spent a year raising the $37 million in funds needed to start the new operation, which had fewer than ten employees.[52][57][61][62] As general partner of the new firm, Romney spent little money on costs such as office appearance, and saw weak spots in so many potential deals that by 1986, few had been done.[48] At first, Bain Capital focused on venture capital opportunities.[48] Their first big success came with a 1986 investment to help start Staples Inc., after founder Thomas G. Stemberg convinced Romney of the market size for office supplies and Romney convinced others; Bain Capital eventually reaped a nearly sevenfold return on its investment, and Romney sat on the Staples board of directors for over a decade.[48][61][62]

Romney soon switched Bain Capital's focus from startups to the relatively new business of leveraged buyouts: buying existing firms with money mostly borrowed against their assets, partnering with existing management to apply the "Bain way" to their operations (rather than the hostile takeovers practiced in other leverage buyout scenarios), and then selling them off in a few years.[48][57] Existing CEOs were offered large equity stakes in the process, as part of Bain Capital's belief in the emerging agency theory notion that CEOs should be bound to maximizing shareholder value rather than other goals.[62] Bain Capital lost most of its money in many of its early leveraged buyouts, but then started finding deals that made large returns.[48] The firm invested in or acquired Accuride, Brookstone, Domino's Pizza, Sealy Corporation, Sports Authority, and Artisan Entertainment, as well as lesser-known companies in the industrial and medical sectors.[48][57][63] During the 14 years Romney headed the company, Bain Capital's average annual internal rate of return on realized investments was 113 percent.[52] Much of this profit was earned from a relatively small number of deals, with Bain Capital's overall success–to–failure ratio being about even.[nb 9]

Less an entrepreneur than an executive running an investment operation,[59][64] Romney was good at presenting and selling the deals the company made.[60] The firm initially gave a cut of its profits to Bain & Company, but Romney persuaded Bain to give that up.[60] Within Bain Capital, Romney spread profits from deals widely within the firm to keep people motivated, often keeping less than ten percent for himself.[65] Viewed as a fair manager, he received considerable loyalty from the firm's members.[62] Romney's wary instincts were still in force at times, and he was generally data-driven and averse to risk.[48][62] He wanted to drop a Bain Capital hedge fund that initially lost money, but other partners prevailed and it eventually gained billions.[48] He also personally opted out of the Artisan Entertainment deal, not wanting to profit from a studio that produced R-rated films.[48] Romney was on the board of directors of Damon Corporation, a medical testing company later found guilty of defrauding the government; Bain Capital tripled its investment before selling off the company, and the fraud was discovered by the new owners (Romney was never implicated).[48] In some cases Romney had little involvement with a company once acquired.[61]

"Sometimes the medicine is a little bitter but it is necessary to save the life of the patient. My job was to try and make the enterprise successful, and in my view the best security a family can have is that the business they work for is strong."

—Mitt Romney in 2007, commenting on job losses at companies that Bain Capital executed leveraged buyouts of.[60]

Bain Capital's leveraged buyouts sometimes led to layoffs, either soon after acquisition or later after the firm had left.[55][48][60][61] How jobs added compared to those lost due to these investments and buyouts is unknown, due to a lack of records and Bain Capital's penchant for privacy on behalf of itself and its investors.[66][67][68] In any case, maximizing the value of acquired companies and the return to Bain's investors, not job creation, was the firm's fundamental goal, as it was for most private equity operations.[61][69] Bain Capital's acquisition of Ampad exemplified a deal where it profited handsomely from early payments and management fees, even though the subject company itself ended up going into bankruptcy.[48][62][69] Dade Behring was another case where Bain Capital received an eightfold return on its investment, but the company itself was saddled with debt and laid off over a thousand employees before Bain Capital exited (the company subsequently went into bankruptcy, with more layoffs, before recovering and prospering).[66] Bain was among the private equity firms that took the most fees in such cases.[57][62]

In 1990, Romney was asked to return to Bain & Company, which was facing financial collapse.[58] He was announced as its new CEO in January 1991[70][71] (but drew only a symbolic salary of one dollar).[58] Romney managed an effort to restructure the firm's employee stock-ownership plan, real-estate deals and bank loans, while rallying the firm's thousand employees, imposing a new governing structure that included Bain and the other founding partners giving up control, and increasing fiscal transparency.[48][52][58] Within about a year, he had led Bain & Company through a turnaround and returned the firm to profitability without further layoffs or partner defections.[52] He turned Bain & Company over to new leadership and returned to Bain Capital in December 1992.[48][71][72]

Romney left Bain Capital in February 1999 to serve as the President and CEO of the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympic Games Organizing Committee.[48] By that time, Bain Capital was on its way to being one of the top private equity firms in the nation,[60] having increased its number of partners from 5 to 18, having 115 employees overall, and having $4 billion under its management.[57][61]

Wealth

Bain Capital's approach of applying consulting expertise to the companies it invested in became widely copied within the private equity industry.[23][61] Economist Steven Kaplan would later say, "[Romney] came up with a model that was very successful and very innovative and that now everybody uses."[62]

At the time of his departure, Romney negotiated an agreement with Bain Capital that allowed him to receive a passive profit share as a retired partner in some Bain Capital entities, including buyout and investment funds.[65][73] Because the private equity business continued to thrive, this deal brought him millions of dollars in income each year.[65]

As a result of his business career, by 2007, Romney and his wife had a net worth of between $190 and $250 million, most of it held in blind trusts.[73] An additional blind trust existed in the name of the Romneys' children and grandchildren that was valued at between $70 and $100 million as of 2007.[74] The couple's net worth remained in the same range as of 2011, and was still held in blind trusts.[75] By 2010 and 2011, Romney and his wife were receiving about $21 million a year from investment income, of which about $3 million went to federal income taxes (based upon the beneficial rate accorded investment income by the U.S. tax code) and about $3.5 million to charity, including to the LDS Church.[76][77] In 2010, the Romney family's Tyler Charitable Foundation gave out about $650,000, with some of it going to organizations that fight specific diseases.[78]

It is estimated that Romney has as much as $100 million in his IRA account, which represents an appreciation of at least 20,000%, and an average annualized growth in excess of 50% for over 25 years.[79] (If Romney’s IRA continues to grow at the above rate, in 65 years Romney’s IRA will be worth over $100 Trillion, and liquidation of Romney’s IRA in 2077 will result in taxes sufficient to pay off the projected national debt that year.)

Local church leadership

Romney has always tithed to the LDS Church, over time donating millions of dollars to it, including stock from Bain Capital holdings[10][80][81] (by 2010 and 2011, annual donations to the church from Romney and his wife were about $2 million a year).[77]

During his years in business, Romney also served in the local lay clergy.[10] Around 1977 he became a counselor to an area leader, an unusual post for someone of his age.[59] He then served as ward bishop for Belmont, Massachusetts from 1981 to 1986, acting as the ecclesiastical and administrative head of his congregation.[82][83] As such, he formulated Sunday services and classes, using the Bible and the Book of Mormon to guide the congregation, and also did home teaching.[84] He forged bonds with other religious institutions in the area when the Belmont Meeting House was hit by a fire of suspicious origins in 1984; the congregation rotated its meetings at other churches while theirs was rebuilt.[80][83]

From 1986 to 1994, Romney presided over the Boston Stake, which included more than a dozen congregations in eastern Massachusetts with a total of about 4,000 church members.[10][59][82][84][85] He organized a team to handle financial and management issues, sought to counter anti-Mormon sentiments, and tried to solve social problems among poor Southeast Asian converts.[80][83] An unpaid position, Romney's local church leadership often took 30 or more hours a week of his time,[84] and he became known for his unflagging energy in the role.[59] Due to his responsibilities, he generally refrained from overnight business travel.[84]

Romney took a hands-on role in general matters, helping in maintenance efforts in- and outside homes, visiting the sick, and counseling troubled or burdened church members.[82][83][84] A number of local church members later credited Romney with turning their lives around or helping them through difficult times.[80][82][83][84] Some others were rankled by his leadership style and desired a more consensus-based approach.[83] Romney tried to balance the conservative dogma insisted upon by the church leadership in Utah with the desire by some Massachusetts members to have a more flexible application of doctrine.[59] He agreed with some modest requests from the liberal women's group Exponent II for changes in the way the church dealt with women, but clashed with women who he felt were departing too much from doctrine.[59] In particular, he counseled women not to have abortions except in the rare cases allowed by LDS doctrine, and also in accordance with doctrine encouraged prospective mothers to give up children for adoption when a successful marriage was not present.[59] Romney later said that the years spent as pastor gave him direct exposure to people struggling in economically difficult circumstances different from his own affluent upbringing, and empathy for those going through problematic family situations.[86]

1994 U.S. senatorial campaign

Romney had been thinking about entering politics for a while.[39] He decided to take on longtime incumbent Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy, who was more vulnerable than usual in 1994 – in part because of the unpopularity of the Democratic Congress as a whole, and also because this was Kennedy's first election since the William Kennedy Smith trial in Florida, in which Kennedy had taken some public relations hits regarding his character.[87][88][89] Romney changed his affiliation from Independent to Republican in October 1993 and formally announced his candidacy in February 1994.[39] He stepped down from his position at Bain Capital, and from his church leadership role, during the run.[15][84]

Romney came from behind to win the Massachusetts Republican Party's nomination for U.S. Senate after buying substantial television time to get out his message and gaining overwhelming support in the state party convention.[90] He then defeated businessman John Lakian in the September 1994 primary with over 80 percent of the vote.[15][91]

In the general election, Kennedy faced the first serious re-election challenger of his career in the young, telegenic, and well-funded Romney.[87] Romney ran as a fresh face, as a businessperson who stated he had created ten thousand jobs, and as a Washington outsider with a solid family image and moderate stands on social issues.[87][92] When Kennedy tried to tie Romney's policies to those of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, Romney responded, "Look, I was an independent during the time of Reagan-Bush. I'm not trying to take us back to Reagan-Bush."[93] Romney stated: "Ultimately, this is a campaign about change."[94] After two decades out of public view, his father George re-emerged during the campaign as well.[95][96]

Romney's campaign was effective in portraying Kennedy as soft on crime, but had trouble establishing its own positions in a consistent manner.[97] By mid-September 1994, polls showed the race to be approximately even.[87][98][99] Kennedy responded with a series of attack ads, which focused both on Romney's seemingly shifting political views on issues such as abortion and on the treatment of workers at the Ampad plant owned by Romney's Bain Capital.[87][100][101] The latter was effective in blunting Romney's momentum.[62] Kennedy and Romney held a widely watched late October debate without a clear winner, but by then Kennedy had pulled ahead in polls and stayed ahead afterward.[102] Romney spent $3 million of his own money in the race.[nb 10]

In the November general election, despite a disastrous showing for Democrats overall, Kennedy won the election with 58 percent of the vote to Romney's 41 percent,[48] the smallest margin in Kennedy's eight re-election campaigns for the Senate.

2002 Winter Olympics

Romney returned to Bain Capital the day after the election but still smarted from the loss, subsequently telling his brother, "I never want to run for something again unless I can win."[39][106] When his father died in 1995, Mitt donated his inheritance to BYU's George W. Romney Institute of Public Management and joined the board and was vice-chair of the Points of Light Foundation (which had incorporated his father's National Volunteer Center).[40][107] His mother died in 1998. Romney felt restless as the decade neared a close; the goal of simply making more money was losing its appeal to him.[39][106] He no longer had a church leadership position, although he still taught Sunday School.[82] Fearing he would be a focal point for opposition, he had a limited, behind-the-scenes role in trying to ease tensions between the church and local residents during the long and controversial approval and construction process for a Mormon temple in Belmont (nevertheless, it still was sometimes referred to as "Mitt's Temple" by locals).[80][82][83][84] Ann Romney was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1998; Romney described watching her fail a series of neurological tests as the worst day of his life.[39] After two years of severe difficulties with the disease, she found in Park City, Utah (where the couple had built a vacation home) a mixture of mainstream, alternative, and equestrian therapies that gave her a lifestyle mostly without limitations.[47] When the offer came for Romney to take over the troubled 2002 Winter Olympics, to be held in Salt Lake City in Utah, she urged him to take it, and eager for a new challenge, he did.[106][108] On February 11, 1999, Romney was hired as the president and CEO of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games of 2002.[109]

Before Romney came on, the event was running $379 million short of its revenue benchmarks.[109] Plans were being made to scale back the games to compensate for the fiscal crisis and there were fears the games might be moved away entirely.[110] The Games had also been damaged by allegations of bribery involving top officials, including prior Salt Lake Olympic Committee president and CEO Frank Joklik. Joklik and committee vice president Dave Johnson were forced to resign.[111] Romney's appointment faced some initial criticism from non-Mormons, and fears from Mormons, that it represented cronyism or gave the games too Mormon an image.[29]

Romney revamped the organization's leadership and policies, reduced budgets, and boosted fund raising. He soothed worried corporate sponsors and recruited many new ones.[106][112] He admitted past problems, listened to local critics, and rallied Utah's citizenry with a sense of optimism.[106] Romney worked to ensure the safety of the Games following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks by ignoring those who suggested the games be called off and coordinating a $300 million security budget.[108][113] Overall he oversaw a $1.32 billion budget, 700 employees, and 26,000 volunteers.[109] The federal government provided $382 million of that budget,[112] much of it because Romney lobbied Congress to provide money for both security- and non-security-related items.[114] An additional federal $1.1 billion was spent on indirect support in the form of highway and transit projects.[114]

Romney became the public face of the Olympic effort, appearing in countless photographs and news stories and even on Olympics souvenir pins.[106] Romney's omnipresence irked those who thought he was taking too much of the credit for the success, or had exaggerated the state of initial distress, or was primarily looking to improve his own image.[106][112]

Despite the initial fiscal shortfall, the Games ended up clearing a profit of $100 million,[115] not counting the $224.5 million in security costs contributed by outside sources.[116] Romney broke the record for most private money raised by any individual for an Olympics games, summer or winter.[108] His performance as Olympics head was rated positively by 87 percent of Utahns.[117] Romney and his wife contributed $1 million to the Olympics, and he donated to charity the $1.4 million in salary and severance payments he received for his three years as president and CEO.[118]

Romney was widely praised for his efforts with the 2002 Winter Olympics[108] including by President George W. Bush,[23] and it solidified his reputation as a turnaround artist.[112] Harvard Business School taught a case study based around Romney's actions.[55] Romney wrote a book about his experience titled Turnaround: Crisis, Leadership, and the Olympic Games, published in 2004. The role gave Romney experience in dealing with federal, state, and local entities, a public persona he had previously lacked, and the chance to re-launch his political aspirations.[106] He was mentioned as a possible candidate for statewide office in both Massachusetts and Utah, and also as possibly joining the Bush administration.[108][119][120]

Governor of Massachusetts

2002 gubernatorial campaign

In 2002, Republican Acting Governor Jane Swift's administration was plagued by political missteps and personal scandals.[117] Many Republicans viewed her as a liability and considered her unable to win a general election.[121] Prominent GOP activists campaigned to persuade Romney to run for governor.[119] One poll taken at that time showed Republicans favoring Romney over Swift by more than 50 percentage points.[122] In March 2002, Swift decided not to seek her party's nomination, and so Romney was unopposed in the Republican party primary.[117][123]

Massachusetts Democratic Party officials contested Romney's eligibility to run for governor, citing residency issues involving Romney's time in Utah for the Olympics. In June 2002, the Massachusetts State Ballot Law Commission unanimously ruled that Romney was eligible to run.[124]

Romney ran as a political outsider again,[117] saying he was "not a partisan Republican" but rather a "moderate" with "progressive" views.[125] Supporters of Romney hailed his business record, especially with the Olympics, as the record of someone who would be able to bring a new era of efficiency into Massachusetts politics.[123] The campaign was the first to use microtargeting techniques, in which fine-grained groups of voters were reached with narrowly tailored messaging.[126] Nevertheless, Romney had difficulty connecting with voters and fell behind his Democratic opponent, Massachusetts State Treasurer Shannon O'Brien, in polls for a while before rebounding.[127] He contributed over $6 million to his own campaign during the election, a state record at the time.[117][128] Romney was elected governor on November 5, 2002, with 50 percent of the vote to O'Brien's 45 percent.[129]

Tenure, 2003–2007

Romney was sworn in as the 70th governor of Massachusetts on January 2, 2003.[130] Both houses of the Massachusetts state legislature held large Democratic majorities.[131] He picked his cabinet and advisors more on managerial abilities than partisan affiliation.[20] Upon entering office in the middle of a fiscal year, Romney faced an immediate $650 million shortfall and a projected $3 billion deficit for the next year.[120] Unexpected revenue of $1.0–1.3 billion from a previously enacted capital gains tax increase and $500 million in unanticipated federal grants decreased the deficit to $1.2–1.5 billion.[132][133] Through a combination of spending cuts, increased fees, and removal of corporate tax loopholes,[132] the state ran surpluses of around $600–700 million for the last two full fiscal years Romney was in office, although it began running deficits again after that.[nb 11]

Romney supported raising various fees by more than $300 million, including those for driver's licenses, marriage licenses, and gun licenses.[120][132] He increased a special gasoline retailer fee by two cents per gallon, generating about $60 million per year in additional revenue.[120][132] (Opponents said the reliance on fees sometimes imposed a hardship on those who could least afford them.)[132] Romney also closed tax loopholes that brought in another $181 million from businesses over the next two years and over $300 million for his term.[120][138] Romney did so from a sense of rectitude and in the face of conservative and corporate critics that considered them tax increases.[138]

The state legislature, with Romney's support, also cut spending by $1.6 billion, including $700 million in reductions in state aid to cities and towns.[139] The cuts also included a $140 million reduction in state funding for higher education, which led state-run colleges and universities to increase tuition by 63 percent over four years.[120][132] Romney sought additional cuts in his last year as governor by vetoing nearly 250 items in the state budget, but all were overridden by the heavily Democratic legislature.[140]

The cuts in state spending put added pressure on local property taxes; the share of town and city revenues coming from property taxes rose from 49 to 53 percent.[120][132] The combined state and local tax burden in Massachusetts increased during Romney's governorship but still was below the national average.[120]

Romney was at the forefront of a movement to bring near-universal health insurance coverage to the state, after Staples founder Stemberg told him at the start of his term that doing so would be the best way he could help people[141][142][143] and after the federal government, due to the rules of Medicaid funding, threatened to cut $385 million in those payments to Massachusetts if the state did not reduce the number of uninsured recipients of health care services.[20][141][144] Despite not having campaigned on the idea of universal health insurance,[143] Romney decided that because people without insurance still received expensive health care, the money spent by the state for such care could be better used to subsidize insurance for the poor.[142][143]

After positing that any measure adopted not raise taxes and not resemble the previous decade's failed "Hillarycare" proposal, Romney formed a team of consultants from different political backgrounds that beginning in late 2004 came up with a set of innovative proposals more ambitious than an incremental one from the Massachusetts Senate and more acceptable to him than one from the Massachusetts House of Representatives that incorporated a new payroll tax.[20][141][144] In particular, Romney pushed for incorporating an individual mandate at the state level.[14] Past rival Ted Kennedy, who had made universal heath coverage his life's work and who, over time, had developed a warm relationship with Romney,[145] gave Romney's plan a positive reception, which encouraged Democratic legislators to cooperate.[141][144] The effort eventually gained the support of all major stakeholders within the state, and Romney helped break a logjam between rival Democratic leaders in the legislature.[141][144]

"There really wasn't Republican or Democrat in this. People ask me if this is conservative or liberal, and my answer is yes. It's liberal in the sense that we're getting our citizens health insurance. It's conservative in that we're not getting a government takeover."

—Mitt Romney upon passage of the Massachusetts health reform law in 2006.[141]

On April 12, 2006, Romney signed the resulting Massachusetts health reform law, which requires nearly all Massachusetts residents to buy health insurance coverage or face escalating tax penalties such as the loss of their personal income tax exemption.[146] The bill also establishes means-tested state subsidies for people who do not have adequate employer insurance and who make below an income threshold, by using funds previously designated to compensate for the health costs of the uninsured.[147][148][149] He vetoed eight sections of the health care legislation, including a controversial $295-per-employee assessment on businesses that do not offer health insurance and provisions guaranteeing dental benefits to Medicaid recipients.[146][150] The legislature overrode all eight vetoes, but the governor's office said the differences were not essential.[150] The law was the first of its kind in the nation and became the signature achievement of Romney's term in office.[144][nb 12]

At the beginning of his governorship, Romney opposed same-sex marriage and civil unions, but advocated tolerance and supported some domestic partnership benefits.[144][152][153] Faced with the dilemma of choosing between same-sex marriage or civil unions after the November 2003 Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decision legalizing same-sex marriages (Goodridge v. Department of Public Health), Romney reluctantly backed a state constitutional amendment in February 2004 that would have banned same-sex marriage but still allow civil unions, viewing it as the only feasible way to ban same-sex marriage in Massachusetts.[154] In May 2004, Romney instructed town clerks to begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, but citing a 1913 law that barred out-of-state residents from getting married in Massachusetts if their union would be illegal in their home state, no marriage licenses were to be issued to out-of-state same-sex couples not planning to move to Massachusetts.[152][155] In June 2005, Romney abandoned his support for the compromise amendment, stating that the amendment confused voters who oppose both same-sex marriage and civil unions.[152] Instead, Romney endorsed a petition effort led by the Coalition for Marriage & Family that would have banned same-sex marriage and made no provisions for civil unions.[152] In 2004 and 2006, he urged the U.S. Senate to vote in favor of the Federal Marriage Amendment.[156][157]

In 2005, Romney revealed a change of view regarding abortion, moving from an "unequivocal" pro-choice position expressed during his 2002 campaign to a pro-life one where he opposed Roe v. Wade.[144] He vetoed a bill on pro-life grounds that would expand access to emergency contraception in hospitals and pharmacies[158] (the veto was overridden by the legislature).[159]

Romney generally used the bully pulpit approach towards promoting his agenda, staging well-organized media events to appeal directly to the public rather than pushing his proposals in behind-doors sessions with the state legislature.[144] Romney dealt with a crisis of confidence in Boston's Big Dig project – that followed a fatal ceiling collapse in 2006 – by wresting control of the project from the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority and helping ensure it would eventually complete.[144]

During 2004, Romney spent considerable effort trying to bolster the state Republican Party, but it failed to gain any seats in the state legislative elections that year.[120][160] Given a prime-time appearance at the 2004 Republican National Convention, Romney was already being discussed as a potential 2008 presidential candidate.[161] Midway through his term, Romney decided that he wanted to stage a full-time run for president,[162] and on December 14, 2005, Romney announced that he would not seek re-election for a second term as governor.[163][164] As chair of the Republican Governors Association, Romney traveled around the country, meeting prominent Republicans and building a national political network;[162] he spent part or all of more than 200 days out of state during 2006, preparing for his run.[165] Romney's frequent out-of-state travel contributed towards his approval rating declining in public polls towards the end of his term.[166] The weak condition of the Republican state party was one of several factors that led to Democrat Deval Patrick's lopsided win over Republican Kerry Healey in the 2006 Massachusetts gubernatorial election.[166]

Romney filed to register a presidential campaign committee with the Federal Election Commission on his penultimate day in office as governor.[167] Romney's term ended January 4, 2007.

2008 presidential campaign

Romney formally announced his candidacy for the 2008 Republican nomination for president on February 13, 2007, at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.[168] In his speech, Romney frequently invoked his father and his own family and stressed experiences in the private, public, and voluntary sectors that had brought him to this point.[168][169] He said, "Throughout my life, I have pursued innovation and transformation,"[169] and casting himself as a political outsider, said, "I do not believe Washington can be transformed from within by a lifelong politician."[170]

The assets that Romney's campaign began with included his résumé of a highly-profitable career in the business world and his stewardship of the Olympics.[162][171][nb 13] Romney also had political experience as governor, together with a political pedigree courtesy of his father, and had a reputation for a strong work ethic and energy level.[162][171][174] Ann Romney, who had become an outspoken advocate for those with multiple sclerosis,[175] was in remission and would be an active participant in his campaign,[176] helping to soften his political personality.[174] Moreover, a number of commentators noted that with his square jaw and ample hair graying at the temples, Romney physically matched one of the common images of what some believed a president should look like.[58][177][178][179] Romney's liabilities included having run for senator and served as governor in one of the nation's most liberal states, having taken some positions there that were opposed by the party's conservative base, and subsequently shifting those positions.[162][171][176] His religion was also viewed with suspicion and skepticism by some in the Evangelical portion of the party.[180]

Romney assembled for his campaign a veteran group of Republican staffers, consultants, and pollsters.[171][181] He was little-known nationally, though, and stayed around the 10 percent range in Republican preference polls for the first half of 2007.[162] Romney's strategy was to win the first two big contests, the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary, and carry the momentum and visibility gained through the big Super Tuesday primaries and on to the nomination.[181] He proved the most effective fundraiser of any of the Republican candidates;[182] his Olympics ties helped him with fundraising from Utahns and from sponsors and trustees of the games.[118] He also partly financed his campaign with his own personal fortune.[171] These resources, combined with the mid-year near-collapse of nominal front-runner John McCain's campaign, made Romney a threat to win the nomination and the focus of the other candidates' attacks.[183] Romney's staff suffered from internal strife and the candidate himself was indecisive at times, constantly asking for more data before making a decision.[171][184]

During all of his political campaigns, Romney has generally avoided speaking publicly about specific Mormon doctrines, referring to the U.S. Constitution prohibition of religious tests for public office.[185] But persistent questions about the role of religion in Romney's life in this race, as well as Southern Baptist minister and former Governor of Arkansas Mike Huckabee's rise in the polls based upon an explicitly Christian-themed campaign, led to the December 6, 2007, "Faith in America" speech.[186] He said should neither be elected nor rejected based upon his religion,[187] and echoed Senator John F. Kennedy's famous speech during his 1960 presidential campaign in saying, "I will put no doctrine of any church above the plain duties of the office and the sovereign authority of the law."[186] Instead of discussing the specific tenets of his faith, he said that he would be informed by it and that, "Freedom requires religion just as religion requires freedom. Freedom and religion endure together, or perish alone."[186][187] Academics would later study the role religion had played in the campaign.[nb 14]

In the January 3, 2008, Iowa Republican caucuses, the first contest of the primary season, Romney received 25 percent of the vote and placed second to the vastly outspent Huckabee, who received 34 percent.[190][191] Of the 60 percent of caucus-goers who were evangelical Christians, Huckabee was supported by about half of them while Romney by only a fifth.[190] A couple of days later, Romney won the lightly contested Wyoming Republican caucuses.[192]

At a Saint Anselm College debate, Huckabee and McCain pounded away at Romney's image as a flip flopper.[190] Indeed, this label would stick to Romney through the campaign[171] (but was one that Romney rejected as unfair and inaccurate, except for his acknowledged change of mind on abortion).[174][193] Romney seemed to approach the campaign as a management consulting exercise, and showed a lack of personal warmth and political feel; journalist Evan Thomas wrote that Romney "came off as a phony, even when he was perfectly sincere."[174][194] Romney's staff would conclude that competing as a candidate of social conservatism and ideological purity rather than of pragmatic competence had been a mistake.[174]

Romney finished in second place by 5 percentage points to the resurgent McCain in the next-door-to-his-home-state New Hampshire primary on January 8.[190] Romney rebounded to win the January 15 Michigan primary over McCain by a solid margin, capitalizing on his childhood ties to the state and his vow to bring back lost automotive industry jobs which was seen by several commentators as unrealistic.[nb 15] On January 19, Romney won the lightly contested Nevada caucuses, but placed fourth in the intense South Carolina primary, where he had effectively ceded the contest to his rivals.[199] McCain gained further momentum with his win in South Carolina, leading to a showdown between him and Romney in the Florida primary.[200][201]

For ten days, Romney campaigned intensively on economic issues and the burgeoning subprime mortgage crisis, while McCain repeatedly, and inaccurately, asserted that Romney favored a premature withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq.[nb 16] McCain won key last-minute endorsements from Florida Senator Mel Martinez and Governor Charlie Crist, which helped push him to a 5 percentage point victory on January 29.[200][201] Although many Republican officials were now lining up behind McCain,[201] Romney persisted through the nationwide Super Tuesday contests on February 5. There he won primaries or caucuses in several states, including Massachusetts, Alaska, Minnesota, Colorado and Utah, but McCain won more, including large states such as California and New York.[203] Trailing McCain in delegates by a more than two-to-one margin, Romney announced the end of his campaign on February 7 during a speech before the Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington.[203]

Altogether, Romney had won 11 primaries and caucuses,[204] received about 4.7 million total votes,[205] and garnered about 280 delegates.[206] Romney spent $110 million during the campaign, including $45 million of his own money.[207]

Romney endorsed McCain for president a week later.[206] He became one of the McCain campaign's most visible surrogates, appearing on behalf of the GOP nominee at fundraisers, state Republican party conventions, and on cable news programs.[208] His efforts earned McCain's respect and the two developed a warmer relationship; he was on the nominee's short list for the vice presidential running mate slot, where his economic expertise would have balanced one of McCain's weaknesses.[209] McCain, behind in the polls, opted instead for a high-risk, high-reward "game changer" and selected Alaska Governor Sarah Palin.[210]

Activity between presidential campaigns

Following the election, Romney paved the way for a possible 2012 presidential campaign by using his Free and Strong America PAC to raise money for other Republican candidates and to pay for salaries and consulting fees for his existing political staff.[211][212] He also had a network of former staff and supporters around the nation who were eager for him to run again.[213] He continued to give speeches and raise campaign funds on behalf of fellow Republicans,[214] but turned down many potential media appearances so as not to become overexposed.[193] He also spoke before business, educational, and motivational groups.[215] He served on the board of directors of Marriott International for a second time (his first tenure was from 1993 to 2002) from 2009 to 2011.[216]

The Romneys sold their main home in Belmont and their ski house in Utah, leaving them an estate along Lake Winnipesaukee in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, and an oceanfront home in the La Jolla district of San Diego, California, which they had bought the year before.[193][217][218] Both locations were near some of the Romneys' grandchildren,[217] who by 2011 numbered sixteen.[219] The San Diego location was also ideal for Ann Romney's multiple sclerosis therapies and for recovering from her late 2008 diagnosis and lumpectomy for mammary ductal carcinoma in situ.[217][220][221] Romney maintained his voting registration in Massachusetts, however, and bought a smaller condominium in Belmont during 2010.[220][222][nb 17] In February 2010, Romney had a minor altercation with LMFAO musical group member Skyler Gordy, known as Sky Blu, on an airplane flight.[nb 18]

Romney's book, No Apology: The Case for American Greatness, was released on March 2, 2010; an 18-state book tour was undertaken.[229] The book, which debuted atop The New York Times Best Seller list,[230] avoided anecdotes about Romney's personal or political life and focused on a presentation of his economic and geopolitical views.[231][232] Earnings from the book were donated to charity.[75]

Polls of various kinds showed Romney remaining in the forefront of possible 2012 presidential contenders. In nationwide opinion polling for the 2012 Republican Presidential primaries, he led polls or placed in the top three with Palin and Huckabee. A January 2010 National Journal poll of political insiders found that a majority of Republican insiders, and a plurality of Democratic insiders, predicted Romney would become the party's 2012 nominee.[233]

Romney campaigned heavily for Republican candidates around the nation in the 2010 midterm elections,[234] and raised the most funds of any of the prospective 2012 Republican presidential candidates.[235] Appearances during early 2011 found Romney emphasizing how his experience could be applied towards solving the nation's economic problems and presenting a more relaxed visual image.[236][237]

2012 presidential campaign

On April 11, 2011, Romney announced in a video taped outdoors at the University of New Hampshire that he had formed an exploratory committee for a run for the Republican presidential nomination.[238][239] A Quinnipiac University political science professor stated, "We all knew that he was going to run. He's really been running for president ever since the day after the 2008 election."[239]

Romney stood to possibly gain from the Republican electorate's tendency to nominate candidates who had previously run for president and appeared to be "next in line" to be chosen.[213][237][240][241][242][243] Perhaps his greatest hurdle in gaining the Republican nomination was party opposition to the Massachusetts health care reform law that he had signed five years earlier.[237][239][243] The early stages of the race found Romney as the apparent front-runner in a weak field, especially in terms of fundraising prowess and organization.[244][245][246] As many potential Republican candidates decided not to run (including Mike Pence, John Thune, Haley Barbour, Mike Huckabee, and Mitch Daniels), Republican party figures searched for plausible alternatives to Romney.[244][246]

On June 2, 2011, Romney formally announced the start of his campaign. Speaking on a farm in Stratham, New Hampshire, he focused on the economy and criticized President Obama's handling of it.[247] He said, "In the campaign to come, the American ideals of economic freedom and opportunity need a clear and unapologetic defense, and I intend to make it – because I have lived it."[243]

Romney raised $56 million during 2011, far more than any of his Republican opponents,[248] and refrained from spending any of his own money on his campaign.[249][250] He initially ran a low-key, low-profile campaign.[251] Michele Bachmann staged a brief surge, then by September 2011, Romney's chief rival in polls was a recent entrant, Texas Governor Rick Perry, and the two exchanged sharp criticisms of each other during a series of debates among the Republican candidates.[252] The October 2011 decisions of Chris Christie and Sarah Palin not to run finally settled the field.[253][254] Perry faded due to poor performances in those debates, while Herman Cain staged a long-shot surge until allegations of sexual misconduct derailed him.

Romney continued to seek support from a wary Republican electorate, with his poll numbers relatively flat and at a historically low level for a Republican frontrunner at this point in the race.[253][255] (A Time magazine cover picturing Romney and captioned "Why Don't They Like Me?" exemplified the phenomenon.)[256][257] After the charges of flip flopping that marked his 2008 campaign began to accumulate again, Romney declared in November 2011 that "I've been as consistent as human beings can be."[258][259][260] In the final month before voting began, Newt Gingrich enjoyed a major surge, taking a solid lead in national polls and in most of the early caucus and primary states[257] before settling back into parity or worse with Romney following a barrage of negative ads from Restore Our Future, a pro-Romney Super PAC.[261]

In the initial 2012 Iowa caucuses of January 3, Romney was announced as the victor on election night with 25 percent of the vote, edging out a late-surging Rick Santorum by eight votes (with an also-surging Ron Paul finishing third),[262] but sixteen days later, Santorum was certified as the winner by a 34-vote margin.[263] Romney decidedly won the New Hampshire primary the following week with a total of 39 percent; Paul finished second with 23 percent and Jon Huntsman third with 17 percent.[264]

In the run-up to the South Carolina Republican primary, Gingrich launched attack ads criticizing Romney for causing job losses while at Bain Capital, Perry referred to Romney's role there as "vulture capitalism", and Sarah Palin questioned whether Romney could prove his claim that 100,000 jobs were created during that time.[265][266] Many conservatives rallied in defense of Romney and the implied criticism of free-market capitalism.[265] However, during two debates, Romney fumbled questions about releasing his income tax returns while Gingrich surged with audience-rousing attacks on the debate moderators.[267][268] Combined with the delayed loss in Iowa, Romney's admitted bad week resulted in a previous double-digit lead in polls – and chance to end the race early – turning into a 13-point loss to Gingrich in the January 21 primary and a decision afterward to release his returns quickly.[267][269] The race turned to the Florida Republican primary, where in debates, appearances, and advertisements, Romney unleashed a concerted, unrelenting attack on Gingrich's past record and associations and current electability.[270][271] Romney enjoyed a big spending advantage from both his campaign and his aligned Super PAC, and after a record-breaking rate of negative ads from both sides, Romney won Florida on January 31, gaining 46 percent of the vote to Gingrich's 32 percent.[272]

February saw a number of caucuses and primaries; Santorum won three in a single night early in the month, propelling him into a lead in national and some state polls and positioning him as Romney's main rival,[273] while Romney won the other five, including a closely fought contest in his home state of Michigan at the end of the month.[274][275] In the Super Tuesday primaries and caucuses of March 6, Romney won six of ten contests, including a narrow victory in Ohio over a greatly-outspent Santorum, and despite not landing a knockout blow to end the race, still held a more than two-to-one edge over Santorum in total delegates.[276][277] Romney has maintained that delegate margin through subsequent contests and has moved ever closer to clinching the nomination.[278][279] Santorum's April 10 decision to stop his campaign made Romney virtually certain to become the nominee.[280]

Political positions and public perceptions

For much of his business career, Romney did not take public political positions.[281][282] He followed national politics avidly in college,[31] and the circumstances of his father's presidential campaign loss would grate on him for decades,[19] but his early philosophical influences were often non-political, such as in his missionary days when he read and absorbed Napoleon Hill's pioneering self-help tome Think and Grow Rich and encouraged his colleagues to do the same.[55][10] Until his 1994 U.S. Senate campaign, he was registered as an Independent.[39] In the 1992 Democratic Party presidential primaries, he had voted for the Democratic former senator from the state, Paul Tsongas.[281][283]

In the 1994 Senate race, Romney aligned himself with Republican Massachusetts Governor William Weld, who believed in fiscal conservatism and supported abortion rights and gay rights, saying "I think Bill Weld's fiscal conservatism, his focus on creating jobs and employment and his efforts to fight discrimination and assure civil rights for all is a model that I identify with and aspire to."[284]

As a gubernatorial candidate, and then as Governor of Massachusetts, Romney again generally operated in the mold established by Weld and followed by Weld's two other Republican successors, Paul Cellucci and Jane Swift: restrain spending and taxing, be tolerant or permissive on social issues, protect the environment, be tough on crime, try to appear post-partisan.[283][285]

During his time as governor, Romney's position on abortion changed in conjunction with a similar change of position on stem cell research.[144][nb 19] Also during that time, his position or choice of emphasis on some aspects of gay rights,[nb 20] and some aspects of abstinence-only sex education,[nb 21] evolved in a more conservative direction. The change in 2005 on abortion was the result of what Romney described as an epiphany experienced while investigating stem cell research issues.[144] He later said, "Changing my position was in line with an ongoing struggle that anyone has that is opposed to abortion personally, vehemently opposed to it, and yet says, 'Well, I'll let other people make that decision.' And you say to yourself, but if you believe that you're taking innocent life, it's hard to justify letting other people make that decision."[144]

This increased alignment with traditional conservatives on social issues coincided with Romney's becoming a candidate for the 2008 Republican nomination for President.[292][293] He displayed a new-found admiration for the National Rifle Association and portrayed himself as a lifelong hunter.[nb 22] He downplayed the Massachusetts health care law,[14][283][293] became a convert on signing an anti-tax pledge,[55][14] and backed away from further closings of corporate tax loopholes.[138] He also displayed aggressiveness on foreign policy matters such as wanting to double the number of detainees at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[293] Skeptics, including some Republicans, charged Romney with opportunism and having a lack of core principles.[144][171][283][297] The fervor with which Romney adopted his new stances and attitudes contributed to the perception of inauthenticity which hampered that campaign.[55][236]

While there have been many biographical parallels between the lives of George Romney and his son Mitt,[nb 23] one particular difference is that while George was willing to defy political trends, Mitt has been much more willing to adapt to them.[14][20] Mitt Romney has said that learning from experience and changing views accordingly is a virtue, and that, "If you're looking for someone who's never changed any positions on any policies, then I'm not your guy."[297] Romney responded to criticisms of ideological pandering with the explanation that "The older I get, the smarter Ronald Reagan gets."[176]

Journalist and author Daniel Gross sees Romney as approaching politics in the same terms as a business competing in markets, in that successful executives do not hold firm to public stances over long periods of time, but rather constantly devise new strategies and plans to deal with new geographical regions and ever-changing market conditions.[283] Political profiler Ryan Lizza sees the same question regarding whether Romney's business skills can be adapted to politics, saying that "while giving customers exactly what they want may be normal in the corporate world, it can be costly in politics".[55] Writer Robert Draper holds a somewhat similar perspective: "The Romney curse was this: His strength lay in his adaptability. In governance, this was a virtue; in a political race, it was an invitation to be called a phony."[174] Writer Benjamin Wallace-Wells sees Romney as a detached problem solver rather than one who approaches political issues from a humanistic or philosophical perspective.[62] Journalist Neil Swidey views Romney as a political and cultural enigma, "the product of two of the most mysterious and least understood subcultures in the country: the Mormon Church and private-equity finance," and believes that has led to the continued interest in a 1983 episode in which Romney went on a long trip with the family dog on the roof of his car.[nb 24] Political writer Joe Klein sees Romney as actually more conservative on social issues than he portrayed himself during his Massachusetts campaigns and less conservative on other issues than his presidential campaigns have represented, and concludes that Romney "has always campaigned as something he probably is not."[303]

Immediately following the March 2010 passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Romney attacked the landmark legislation as "an unconscionable abuse of power" and said the act should be repealed.[304] The hostile attention it held among Republicans created a potential problem for the former governor, since the new federal law was in many ways similar to the Massachusetts health care reform passed during Romney's term; as one Associated Press article stated, "Obamacare ... looks a lot like Romneycare."[304] While acknowledging that his plan was not perfect and still was a work in progress, Romney did not back away from it, and has consistently defended the state-level health insurance mandate that underpins it.[304][305] He has focused on its having had bipartisan support in the state legislature, while the Obama plan received no Republican support at all in Congress,[304] and upon it being the right answer to Massachusetts' specific problems at the time.[304][306] A Romney spokesperson has stated: "Mitt Romney has been very clear in all his public statements that he is opposed to a national individual mandate. He believes those decisions should be left to the states."[307] While Romney has not explicitly argued for a federally imposed mandate, during his 1994 Senate campaign he indicated he would vote for an overall health insurance proposal that contained one, and he suggested during his time as governor and during his 2008 presidential campaign that the Massachusetts plan was a model for the nation and that, over time, mandate plans might be adopted by most or all of the nation.[308][309][310][311]

Throughout his business, Olympics, and political career, Romney's instinct has been to apply the "Bain way" towards problems.[174][293][312] Romney has said, "There were two key things I learned at Bain. One was a series of concepts for approaching tough problems and a problem-solving methodology; the other was an enormous respect for data, analysis, and debate."[312] He has written, "There are answers in numbers – gold in numbers. Pile the budgets on my desk and let me wallow."[55] Romney believes the Bain approach is not only effective in the business realm but also in running for office and, once there, in solving political conundrums such as proper Pentagon spending levels and the future of Social Security.[293][312] Former Bain and Olympics colleague Fraser Bullock has said of Romney, "He's not an ideologue. He makes decisions based on researching data more deeply than anyone I know."[23] Romney's technocratic instincts have thus always been with him; in his public appearances during the 2002 gubernatorial campaign he sometimes gave PowerPoint presentations rather than conventional speeches.[313] Upon taking office he became, in the words of The Boston Globe, "the state's first self-styled CEO governor".[120] During his 2008 presidential campaign, he was constantly asking for data, analysis, and opposing arguments,[293] and has been viewed as a potential "CEO president".[283]

Awards and honors

Romney has received four honorary doctorates: an Honorary Doctor of Business from the University of Utah in 1999,[314] an Honorary Doctor of Law from Bentley College in 2002,[315] an Honorary Doctor of Public Administration from Suffolk University Law School in 2004,[316] and an Honorary Doctor of Public Service from Hillsdale College in 2007.[317]

People magazine included Romney in its 50 Most Beautiful People list for 2002.[318] In 2004, Romney received the inaugural Truce Ideal Award for his role in the 2002 Winter Olympics.[319] In 2006, he received the Secretary of Defense Employer Support Freedom Award, the highest recognition given by the U.S. Government to employers for their support of their employees who serve in the National Guard and Reserve, on behalf of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.[320] In 2008, he shared with his wife Ann the Canterbury Medal from The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, for "refus[ing] to compromise their principles and faith" during the presidential campaign.[321]

Writings

- With Timothy Robinson (2004). Turnaround: Crisis, Leadership, and the Olympic Games. Washington: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0-89526-084-0.

- No Apology: The Case for American Greatness. New York: St. Martin's Press. 2010. ISBN 0-312-60980-9.

See also

- Republican Party presidential debates, 2012

- Mitt Romney presidential campaign, 2012

- Republican Party presidential primaries, 2012

- Results of the 2012 Republican Party presidential primaries

- List of richest American politicians

- List of JD/MBAs

Notes

- ^ He was called "Billy" until kindergarten, when he indicated a preference for "Mitt".[15]

- ^ Mitt's campaigning for his father included working the phone banks and appearing at county fairs; at the latter, he manned a booth and exclaimed over a loudspeaker, "You should vote for my father for Governor. He's a truly great person. You've got to support him. He's going to make things better."[14]

- ^ Such pranks included sliding down golf courses on large ice cubes, dressing as a police officer and tapping on the car windows of teenage friends who were making out, and staging an elaborate formal dinner on the median of a busy street.[16][21] The golf course escapade apparently got Romney and Ann Davies arrested, or otherwise detained, by the local police.[19][23] Romney was also arrested in 1981 while at a family outing at Lake Cochituate in Massachusetts. According to Romney, a ranger from Cochituate State Park told him his motorboat had an insufficiently visible license number and he would face a $50 fine if he took the boat onto the lake. Disagreeing about the license and wanting to continue the outing, Romney took it out anyway, saying he would pay the fine. The angry officer then arrested him for disorderly conduct. The charges were dropped several days later after Romney threatened to sue the officer and the state for false arrest.[24]

- ^ a b When initially considering colleges after high school, Romney had not wanted to go to BYU.[38] He later recounted that he had planned to attend BYU to convince Ann to marry him, then the couple planned to transfer together back to Stanford, but in the end, they enjoyed BYU and decided to stay.[40]

- ^ Romney's great-grandfather, grandfather, father, and two uncles had been missionaries,[32] as had his older brother.[31] All five of Romney's sons would do stints as missionaries.[33]

- ^ a b On June 16, 1968, Romney was driving fellow missionaries on dangerous roads in southern France.[16][22][35] As they drove through the village of Bernos-Beaulac, a Mercedes that was passing a truck missed a curve and suddenly swerved into the opposite lane and hit the Citroën DS Romney was driving in a head-on collision.[16][36] Trapped between the steering wheel and door, the unconscious and seriously injured Romney had to be pried from the car; a French police officer mistakenly wrote Il est mort in his passport.[16][19][35] The wife of the mission president was killed and other passengers were seriously injured as well.[35] George Romney relied on his friend Sargent Shriver, the U.S. Ambassador to France, to go to the local hospital and discover that his son had survived.[19] Romney, who was not at fault in the accident,[31][35] had suffered broken ribs, a fractured arm, a concussion, and facial injuries, but recovered quickly without needing surgery.[22][35] The French police say that they have no records of the incident because such records are routinely destroyed after 10 years.[35]

- ^ Some sources incorrectly report that Romney graduated BYU as valedictorian. Romney himself has corrected this notion, saying that he was not. While he believes he did have the highest grade point average for his BYU years in the College of Humanities, he did not if his Stanford year was factored in, and he did not among the graduating class university-wide.[45][40]

- ^ Romney sat for the bar exam in his home state of Michigan in July 1975, passed it and was admitted to practice law there, but never worked as a lawyer and only considered in case his business career did not work out.[53]

- ^ One study of 68 deals that Bain Capital made during Romney's time there found that the firm lost money or broke even on 33 of them.[59] Another study that looked at the eight-year period following 77 deals during Romney's time found that in 17 cases the company went bankrupt or out of business, and in 6 cases Bain Capital lost all its investment. But 10 deals were very successful and represented 70 percent of the total profits.[64]

- ^ Romney spent $3 million of his own money in the 1994 race[103] and more than $7 million overall. Kennedy spent $10.5 million overall, including a $1.5 million loan to himself.[104] This was the second-most expensive race of the 1994 election cycle, after the Dianne Feinstein–Michael Huffington Senate race in California.[105]

- ^ Official state figures for fiscal year 2005 (July 1, 2004 – June 30, 2005) declared a $594.4 million surplus.[120][134] For fiscal 2006, the surplus was $720.9 million.[134] During fiscal 2007, Romney cut $384 million in spending that the legislature wanted; in January 2007, midway through the fiscal year, incoming Governor Deval Patrick restored that amount,[135] and also declared that the state faced a "looming budget shortfall" of $1 billion for fiscal 2008.[136] Patrick consequently proposed a budget for fiscal 2008 that included $515 million in spending cuts and $295 million in new corporate taxes.[137] As it happened, the state ended fiscal 2007 with a $307.1 million deficit and fiscal 2008 with a $495.2 million deficit.[134]

- ^ Within four years, the Massachusetts law had achieved its primary goal of expanding coverage: in 2010, 98% of state residents had coverage, compared to a national average of 83%. Among children and seniors the 2010 coverage rate was even higher, 99.8% and 99.6% respectively. Approximately two-thirds of residents received coverage through employers; one-sixth each received it through Medicare or public plans.[151]

- ^ American political opinion periodically looked towards industry for business managers who it was thought could straighten out what was held to be wrong in the nation's capital. The track record of such efforts was at best mixed, with Lee Iacocca declining to run, Romney's father George and Steve Forbes failing to get far in the primaries, and Ross Perot staging one of the more successful third-party runs in American history.[172][173]