White trash

White trash is a derogatory American English slur referring to poor white people, especially in the rural southern United States. The label signifies a low social class inside the white population[1] and especially a degraded standard of living.[2] The term has been adopted for people living on the fringes of the social order, who are seen as dangerous because they may be criminal, unpredictable, and without respect for political, legal, or moral authority.[3] The term is primarily used by urban and middle-class whites as a class signifier,[4] but may also be used self-referentially by working class whites to jokingly describe their origins or lifestyle.[5][6][7][8][9]

In common usage, "white trash" overlaps in meaning with "crackers", used of people in the backcountry of the Southern states; "hillbilly", regarding poor people from Appalachia; "Okie" regarding those with origins in Oklahoma; and "redneck", regarding rural origins; especially in the South.[10] The primary difference is that "redneck", "cracker", "Okie", and "hillbilly" emphasize that a person is poor and uneducated and comes from the backwoods with little awareness of and interaction with the modern world, while "white trash" – and the modern term "trailer trash" – emphasizes the person's moral failings.[11]

Scholars from the late 19th to the early 21st century explored generations of families who were considered "disreputable", such as The Jukes family and The Kallikak Family, both pseudonyms for real families. [12]

Description and causes

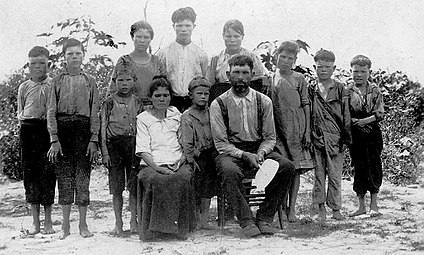

In the popular imagination of the mid-19th century, "poor white trash" were a "curious" breed of degenerate, gaunt, haggard people who suffered from numerous physical and social defects. They were dirty, callow, ragged, cadaverous, leathery, and emaciated, and had feeble children with distended abdomens who were wrinkled and withered and looked aged beyond their physical years, so that even 10-year-olds' "countenances are stupid and heavy and they often become dropsical and loathsome to sight," according to a New Hampshire schoolteacher. The skin of a poor white Southerner had a "ghastly yellowish-white" tinge to it, like "yellow parchment", and was waxy looking, or they were so white they almost appeared to be albinos. They were listless and slothful, did not properly care for their children, and were addicted to alcohol. They were looked on with contempt by upper-class Southerners.[13]

Harriet Beecher Stowe described a white trash woman and her children in Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, published in 1856:

Crouched on a pile of dirty straw, sat a miserable haggard woman, with large, wild eyes, sunken cheeks, disheveled matted hair, and long, lean hands, like a bird's claws. At her skinny breast an emaciated infant was hanging, pushing, with its little skeleton hands, as if to force nourishment which nature no longer gave; and two scared-looking children, with features wasted and pinched blue with famine, were clinging to her gown. The whole group huddled together, drawing as far away as possible from the new comer [sic], looking up with large, frightened eyes, like hunted wild animals.[14]

Poor white trash were generally only able to locate themselves on the worst land in the South, since the best land was taken by the slaveholders, large and small. They lived and attempted to survive on land that was sandy or swampy or covered in scrub pine and not suited for agriculture; for this they became known as "sandhillers" and "pineys".[15] These "hard-scratch" inhabitants were seen to match their surroundings: they were "stony, stumpy, and shrubby, as they land they lived on."[16]

Restricted from holding political office due to property qualifications, their ability to vote at the mercy of the courts which were controlled by the slave-holding planters, poor whites had few advocates within the political system or the dominant social hierarchy. Although many were tenant farmers or day laborers, other white trash people were forced to live as scavengers, thieves and vagrants, but all, employed or not, were socially ostracized by "proper" white society by being forced to use the back door when entering "proper" homes. Even slaves looked down on them: when poor whites came begging for food, the slaves called them "stray goats."[17]

Northerners claimed that the existence of white trash was the result of the system of slavery in the South, while Southerners worried that these clearly inferior whites would upset the "natural" class system which held that all whites were superior to all other races, especially blacks. People of both regions expressed concern that if the number of white trash people increased significantly, they would threaten the Jeffersonian ideal of a population of educated white freemen as the basis of a robust American democracy.[18]

History

Beginning in the early 1600s, the City of London shipped their unwanted excess population, including vagrant children, to the American colonies – especially Virgina, Maryland, and Pennsylvania – where they became not apprentices, as the children had been told, but indentured servants, especially working in the fields. Even before the beginning of the slave trade brought Africans to the colonies in 1619, this influx of "transported" Britons, Scots and Irish was a crucial part of the American workforce. The Virginia Company also imported boatloads of poor woman to be sold as brides. The numbers of these all-but-slaves was significant: by the middle of the 17th century, at a time when the population of Virgina was 11,000, only 300 were Africans, who were unnumbered by British, Irish and Scots indentured servants. In New England, one-fifth of the Puritans were indentured servants. More indentured servants were sent to the colonies as a result of insurrections in Ireland; Oliver Cromwell sent hundreds of Irish Catholics to British North America for this reason. In 1718 Parliament passed the Transportation Act, which allowed tens of thousands of convicts to be sent to North America to alleviate overcrowding in British prisons. By the time it ceased during the American Revolutionary War, some 50,000 people had been transported to the New World under the law. When the American market closed to them, the convicts were then sent to Australia. In total, 300,000 to 400,000 people were shipped to the North American colonies as unfree laborers, between 1/2 and 2/3 of all white immigrants.[19]

The British conceived of the American colonies as a "wasteland", and a place to dump their underclass.[20] The people they sent there were "waste people", the "scum and dregs" of society. The term "waste people" gave way to "squatters" and "crackers", used to describe the settlers who populated the western frontier of the United States and the backcountry of some southern states, but who did not have title to the land they settled on.[21] "Cracker" was especially used in the south.

The first use of "white trash" in print to describe this population occurred in 1821.[22] It came into common use in the 1830s as a pejorative used by house slaves against poor whites. In 1833, Fanny Kemble, an English actress visiting Georgia, noted in her journal: "The slaves themselves entertain the very highest contempt for white servants, whom they designate as 'poor white trash'".[23][24]

The term achieved widespread popularity in the 1850s,[22] and by 1855, it had passed into common usage by upper-class whites, and was common usage among all Southerners, regardless of race, throughout the rest of the 19th century.[25]

In 1854, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote the chapter "Poor White Trash" in her book A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin. Stowe wrote that slavery not only produces "degraded, miserable slaves", but also poor whites who are even more degraded and miserable. The plantation system forced those whites to struggle for subsistence. Beyond economic factors, Stowe traces this class to the shortage of schools and churches in their community, and says that both blacks and whites in the area look down on these "poor white trash".[26] In Stowe's second novel Dred, she describes the poor white inhabitants of that swamp, which formed much of the border between Virginia and North Carolina, as an ignorant, degenerate and immoral class of people prone to criminality.[27] Hinton Rowan Helper's extremely influential 1857 book The Impending Crisis of the South – which sold 140,000 copies and was considered to be the most important book of the 19th century by many people – describes the region's poor Caucasians as a class oppressed by the effects of slavery, a people of lesser physical stature who would be driven to extinction by the South's "cesspool of degradation and ignorance."[28]

During the Civil War

During the Civil War, the Confederacy instituted conscription to raise soldiers for its army, with all men between the ages of 18 and 35 being eligible to be drafted – later expanded to all men between 17 and 50. However, exemptions were numerous, including any slave-owner with more than 20 slaves, political officeholders, teachers, ministers and clerks, and men who worked in valuable trades. Left to be drafted, or to serve as paid substitutes, were poor white trash Southerners, who were looked down on as cannon fodder. Conscripts who failed to report for duty were hunted down by so-called "dog catchers". Poor southerners said that it was a "rich man's war", but "a poor man's fight." While upper-class Southern "cavalier" officers were granted frequent furloughs to return home, this was not the case with the ordinary private soldier, which led to an extremely high rate of desertion among this group, who put their families well-being above the cause of the Confederacy, and thought of themselves as "Conditional Confederates." Deserters harassed soldiers, raided farms and stole food, and sometimes banded together in settlements, such as the "Free State of Jones" (formerly Jones County) in Mississippi; desertion was openly joked about. When found, deserters could be executed, or humiliated by being put into chains.[29]

Despite the war being fought to protect the right of the patrician elite of the South to own slaves, the planter class was reluctant to give up their cash crop, cotton, to grow the corn and grain needed by the Confederate armies and the civilian population. As a result, food shortages, exacerbated by inflation and hoarding of foodstuffs by the rich, caused the poor of the South to suffer greatly. This led to food riots of angry mobs of poor women, who raided stores, warehouses and depots looking for sustenance for their families. Both the male deserters and the female rioters put the lie to the myth of Confederate unity, and that the war was being fought for the rights of all white Southerners.[30]

Ideologically, the Confederacy claimed that the system of slavery in the South was superior to the class divisions of the North, because while the South devolved all its degrading labor onto what it saw as an inferior race, the black slaves, the North did so to its own "brothers in blood", the white working class. This the leaders and intellectuals of the Confederacy called "mudsill" democracy, and lauded the superiority of the pure-blooded Southern slave-owning "cavaliers" – who were worth five Northerners in a fight – over the sullied Anglo-Saxon upper class of the North.[31] For its part, some of the military leaders of the North, especially Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, recognized that their fight was not only to liberate slaves, but also the poor white Southerners who were oppressed by the system of slavery. Thus they took steps to exploit the class divisions between the white trash population and plantation owners. An Army chaplain wrote in a letter to his wife after the Union siege of Petersburg, Virginia that winning the war would not only result in the end of American slavery, but would also increase opportunities for "poor white trash." He said that the war would "knock off the shackles of millions of poor whites, whose bondage was really worse than that African." In these respects, the Civil War was in large part a class war.[32]

During Reconstruction

After the war, President Andrew Johnson's first idea for the reconstruction of the South was not to take steps to create an egalitarian democracy. Instead, he envisioned what was essentially a "white trash republic", in which the aristocracy would maintain their property holdings and an amount of social power, but be disenfranchised until they could show their loyalty to the Union. The freed blacks would no longer be slaves, but would still be denied essential rights of citizenship and would make up the lowest rung on the social ladder. In between would be the poor white Southerner, the white trash, who while occupying a lesser social position, would essentially become the masters of the South, voting and occupying political offices, and maintaining a superior status to the free blacks and freed slaves. Emancipated from the inequities of the plantation system, poor white trash would become the bulwark of Johnson's rebuilding of the South and its restoration into the Union.[33]

Johnson's plan was never put into effect, and the Freedmen's Bureau, – which was created in 1865, before President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated – was authorized to help "all refugees and all freedmen", black and white alike, and the agency did this, despite Johnson's basic lack of concern for the freed slaves the war had supposedly been fought over. But even though they provided relief to them, the Bureau did not accept Johnson's vision of poor whites as the loyal and honorable foundation of a reconstructed South. Northern journalists and other observers maintained that poor white trash, who were now destitute refugees, "beggars, dependents, houseless and homeless wanderers", were still victimized by poverty and vagrancy. They were "loafers" dressed in rags and covered in filth who did no work, but accepted government relief handouts. They were seen as only slightly more intelligent than blacks. One observer, James R. Gilmore, a cotton merchant and novelist who had traveled throughout the South, wrote the book Down in Tennessee, published in 1864, in which he differentiated poor whites into two groups, "mean whites" and "common whites". While the former were thieves, loafers and brutes, the latter were law-abiding citizens who were enterprising and productive. It was the "mean" minority who gave white trash their bad name and character. [34]

A number of commentators noted that poor white Southerners did not compare favorably to freed blacks, who were described as "capable, thrifty, and loyal to the Union." Marcus Sterling, a Freedmen's Bureau agent and a former Union officer, said that the "pitiable class of poor whites" were "the only class which seem almost unaffected by the [bureau's] great benevolence and its bold reform", while in contrast black freedmen had become "more settled, industrious and ambitious," eager to learn how to read and improve themselves. Sidney Andrews saw in black a "shrewd instinct for preservation" which poor whites did not have, and Whitelaw Reid, a politician and newspaper editor from Ohio, thought that black children appeared eager to learn. Atlantic Monthly went so far as to suggest that government policy should switch from "disenfranchis[ing] the humble, quiet, hardworking Negro" and cease to provide help to the "worthless barbarian", the "ignorant, illiterate, and vicious" white trash population.[35]

So, during the Reconstruction Era, white trash were no longer seen simply as a freakish, degenerate breed who lived almost invisibly in the backcountry wilderness, the war had brought them out of the darkness into the mainstream of society, where they developed the reputation of being a dangerous class of criminals, vagrants and delinquents, lacking intelligence, unable to speak properly, the "Homo genus without the sapien", an evolutionary dead end in the Social Darwinist thinking of the time. Plus, they were immoral, breaking all social codes and sexual norms, engaging in incest and prostitution, pimping out family members, and producing numerous in-bred bastard children.[36]

Scalawags and rednecks

One of the responses of Southerners and Northern Democrats after the war to Reconstruction was the invention of the myth of the "carpetbaggers", those Northern Republican scoundrels and adventurers who invaded the South to take advantage of its people, but less well known is that of the "scalawags", those Southern white who betrayed their race by supporting the Republican Party and Reconstruction. The scalawag, even if they came from a higher social class, was often described as having a "white trash heart". They were accused of easily mingling with blacks, inviting them to dine in their homes, and inciting them by encouraging them to seek social equality. The Democrats retaliated with Autobiography of a Scalawag, a parody of the standard "self-made man" story, in which a white trash southerner with no innate ambition nevertheless is raised to a position of middling power just by being in the right place at the right time or by lying and cheating.[37]

Around 1890, the term "redneck" began to be widely used for poor white southerners, especially those racist followers of the Democratic demagogues of the time. Rednecks were found working in the mills, living deep in the swamps, heckling at Republican rallies, and were even occasionally elected to be a state legislator. Such was the case with Guy Rencher, who claimed that "redneck" came from his own "long red neck".[38]

The Depression

The beginning of the 20th century brought no change of status for poor white southerners, especially after the onset of the Great Depression. The condition of this class was presented to the public in Margaret Bourke-White's photographic series for Life magazine, and the work of other photographers made for Roy Stryker's Historical Section of the federal Resettlement Agency. Author James Agee wrote about them in his ground-breaking work Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), as did Jonathan Daniels in A Southerner Discovers the South (1938).[39]

A number of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal agencies tried to help the rural poor to better themselves and to break through the social barriers of Southern society which held them back, reinstating the American Dream of upward mobility. Programs such as those of the Subsistence Homesteads Division of the Department of the Interior; its successor, the Resettlement Administration, whose express purpose was to help the poor in rural areas; and its replacement, the Farm Security Administration which aimed to break the cycle of tenant farming and sharecropping and help poor whites and black to own their own farms, and to initiate the creation of the communities necessary to support those farms. The agencies also provided services for migrant workers, such as the Arkies and Okies, who had been devastated by the Dust Bowl – the condition of which was well-documented by photographer Dorothea Lange in An American Exodus (1939) – and been forced to take to the road, jamming all their belongings into Ford motorcars and heading west toward California.[39]

Important in the devising and running of these programs were politicians and bureaucrats such as Henry Wallace, the Secretary of Agriculture; Milburn Lincoln Wilson, the first head of the Subsistence Homesteads Division, who was a social scientist and an agricultural expert; and Rexford G. Tugwell, a Columbia University economics professor who managed to be appointed the first head of the Resettlement Agency, despite refusing to present himself with a "homely, democratic manner" in his confirmation hearings. Tugwell understood that the status of tenant farmers would not change if they could not vote, so he campaigned against poll tax, which prevented them voting, since they could not afford to pay it. His agency's goals were the four "R's": "retirement of bad land, relocation of rural poor, resettlement of the unemployed in suburban communities, and rehabilitation of farm families."[39]

Other individuals important in the fight to help the rural poor were Arthur Raper, an expert on tenancy farming, whose study Preface to Peasantry (1936) explained why the south's system held back the region's poor and caused them to migrate; and Howard Odum, a University of North Carolina sociologist and psychologist who founded the journal Social Forces, and worked closely with the Federal government. Odum wrote the 600-page masterwork Southern Regions of the United States, which became a guidebook for the New Deal. Journalist Gerald W. Johnson translated Odum's ideas in the book into a popular volume, The Wasted Land. It was Odum who, in 1938, mailed questionnaires to academics to determine their views on what "poor white" meant to them. The results were in many ways indistinguishable from the popular views of "white trash" that had been held for many decades, since the words that came back all indicated serious character flaws in poor whites: "purposeless, hand to mouth, lazy, unambitious, no account, no desire to improve themselves, inertia", but, most often, "shiftless". Despite the passage of time, poor whites were still seen as white trash, a breed apart, a class partway between blacks and whites, whose shiftless ways may have even originated from their proximity to blacks.[39]

Trailer trash

In the mid-20th century, poor whites who could not afford to buy suburban-style tract housing began to purchase mobile homes, which were not only cheaper, but which could be easily relocated if work in one location ran out. These – sometimes by choice and sometimes through local zoning laws – gathered in trailer camps, and the people who lived in them became known as "trailer trash". Despite many of them having jobs, albeit sometimes itinerant ones, the character flaws that had been perceived in poor white trash in the past were transferred to trailer trash, and trailer camps or parks were seen as being inhabited by retired persons, migrant workers, and, generally, the poor. By 1968, a survey found that only 13% of those who owned and lived in mobile homes had white collar jobs.[40]

Trailers got their start in the 1930s, and their use proliferated during the housing shortage of World War II, when the Federal government used as many as 30,000 of them to house defense workers, soldiers and sailors throughout the country, but especially around areas with a large military or defense presence, such as Mobile, Alabama and Pascagoula, Mississippi. In her book Journey Through Chaos, reporter Agnes Meyer of The Washington Post travelled throughout the country, reporting on the condition of the "neglected rural areas", and described the people who lived in the trailers, tents and shacks in such areas as malnourished, unable to read or write, and generally ragged. The workers who came to Mobile and Pascagoula to work in the shipyards there were from the backwoods of the South, "subnormal swamp and mountain folk" whom the locals described as "vermin"; elsewhere, they were called "squatters". They were accused of having loose morals, high illegitimacy rates, and of allowing prostitution to thrive in their "Hillbilly Havens". The trailers themselves – sometimes purchased second- or third-hand – were often unsightly, unsanitary and dilapidated, causing communities to zone them away from the more desirable areas, which meant away from schools, stores, and other necessary facilities, often literally on the other side of the railroad tracks.[40]

In popular culture

Violence

American pop culture connects both drinking and violence to being a white, poor, rural man[41] for which there is considerable evidence.[42] The historian David Hackett Fischer, a Professor of History at Brandeis University, makes a case for an enduring genetic basis for a "willingness to resort to violence" (citing especially the finding of high blood levels of testosterone) in the four main chapters of his book Albion's Seed.[43] He proposes that a Mid-Atlantic state, Southern and Western propensity for violence is inheritable by genetic changes wrought over generations living in traditional herding societies in Northern England, the Scottish Borders, and Irish Border Region. He proposes that this propensity has been transferred to other ethnic groups by shared culture, whence it can be traced to different urban populations of the United States.[44]

White popular culture

George Bernard Shaw uses the term in his 1909 play The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet, set in the wild American west. The prostitute Feemy says to Blanco "I'll hang you, you dirty horse-thief; or not a man in this camp will ever get a word or a look from me again. You're just trash: that's what you are. White trash."

Ernest Matthew Mickler's White Trash Cooking (1986) enjoyed an unanticipated rise to popularity. The cookbook, which is based on the cooking of rural white Southerners, features recipes with names such as Goldie's Yo Yo Pudding, Resurrection Cake, Vickies Stickies, and Tutti's Fruited Porkettes.[45][46] As Sherrie A. Inness notes, "white trash authors used humor to express what was happening to them in a society that wished to forget about the poor, especially those who were white". She points out that under the humor was a serious lesson about living in poverty.[47]

By the 1980s, fiction was being published by Southern authors who identified as having redneck or white trash origins, such as Harry Crews, Dorothy Allison, Larry Brown, and Tim McLaurin.[48] Autobiographies sometimes mention white trash origins. Gay rights activist Amber L. Hollibaugh wrote, "I grew up a mixed-race, white-trash girl in a country that considered me dangerous, corrupt, fascinating, exotic. I responded to the challenge by becoming that alarming, hazardous, sexually disruptive woman."[49]

Mainstream literature

- 1900 – Evelyn Greenleaf Sutherland's play Po' White Trash, exposes complicated cultural tensions in the post-Reconstruction South, related to the social and racial status of poor whites.[50]

- 1907? – O Henry's short story "Shoes" refers to the male protagonist "Pink Dawson" – which the narrator consistently confuses with "Dink Pawson" – as "Poor white trash".[51]

- 1986 – Ernest Matthew Mickler's self-deprecating cookbook White Trash Cooking, contains recipes from the American South East.[52]

Black popular culture

Use of "white trash" epithets has been extensively reported in African American culture.[53][54][55] Black authors have noted that blacks, when taunted by whites as "niggers", taunted back, calling them "white trash".[54] Some black parents taught their children that poor whites were "white trash".[56] The epithet appears in black folklore.[57] As an example, slaves (when out of earshot of whites) would refer to harsh slave owners as a "low down" man, "lower than poor white trash", "a brute, really".[58]

Mainstream literature

- 1948 – Zora Neale Hurston's Seraph on the Suwanee explores images of "white trash" women. In 2000, Chuck Jackson argued in the African American Review that Hurston's meditation on abjection, waste, and the construction of class and gender identities among poor whites reflects the eugenics discourses of the 1920s.[59]

See also

|

|

References

Notes

- ^ https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/313197/white-trash-by-nancy-isenberg/9780143129677/excerpt

- ^ Donnella, Leah (August 1, 2018). "Why Is It Still OK To 'Trash' Poor White People?". Code Switch. NPR. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Wray (2006), p. 2

- ^ Hartigan, John Jr. (2003). "Who are these white people?: 'Rednecks,' 'Hillbillies,' and 'White Trash' as marked racial subjects". In Doane, Ashley "Woody"; Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo (eds.). White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism. Routledge. pp. 97, 105. ISBN 0-41-593582-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Lamar, Michelle; Wendland, Molly (2008). The White Trash Mom Handbook: Embrace Your Inner Trailerpark, Forget Perfection, Resist Assimilation into the PTA, Stay Sane, and Keep Your Sense of Humor.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Mickler, Ernest (1986). White Trash Cooking.

- ^ Morris, Kendra (2006). White Trash Gatherings: From-Scratch Cooking for down-Home Entertaining.

- ^ Marbry, Bill (2011). Talkin' White Trash.

- ^ https://www.muniarequipa.gob.pe/libraries/cms/language/all/34ce68gdrx2483590634ce68.html

- ^ Wray (2006), p. x

- ^ Wray (2006), pp. 79, 102

- ^ Rafter, Nicole Hahn (1988) White Trash: The Eugenic Family Studies, 1877-1919

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.136, 146, 151-52, 167, 170

- ^ Stowe, Harriet Beecher (2000} [1856] Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp Chapel Hill, North Carolia: University of North Carolina Press. pp.105-06. Quoted in Isenberg (2016), p.148-49

- ^ Isenberg (2016), p.146

- ^ Burton, Warren (1839) White Slavery: A New Emancipation Cause Presented to the United States. Worcester, Massachusetts. pp.168-69; quoted in Isenberg (2016), p.146

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.149-150

- ^ Isenberg (2016), p.136

- ^ Painter, Nell Irvin (2010) The History of White People New York: Norton. pp.41-42. ISBN 978-0-393-33974-1

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.xxvi-xxvii, 17-42

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.105-132

- ^ a b Isenberg (2016), p.135

- ^ Kemble, Fannie (1835) Journal. p. 81

- ^ Wray suggests that the term may have originated in the Baltimore-Washington area during the 1840s, when Irish and blacks were competing for the same jobs. Wray (2006),42-p.44. The quote from Kemble is reprinted in page 41 of the book.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee; Wray, Matthew (July 1, 1997). "What is White Trash?" (PDF). In Hill, Mike (ed.). Whiteness: a Critical Reader. NYU Press. p. 170. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Wray (2006), pp. 57-58

- ^ Isenberg (2016), p.137

- ^ Helper, Hinton Rowan (1968) [1857] The Impending Crisis of the South. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press; quoted in Isenberg (2016), p.137

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.159, 163-65

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.165-66

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.157-160

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.157-160, 172

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.176-78

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.177-80

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.179-180

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.180-81

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.182-86

- ^ Isenberg (2016), pp.187-90

- ^ a b c d Isenberg (2016), pp.206-30

- ^ a b Isenberg (2016), pp.240-47

- ^ Jason T. Eastman and Douglas P. Schrock, "Southern Rock Musicians' Construction of White Trash", Race, Gender & Class, Vol. 15, No. 1/2 (2008), pp. 205-219

- ^ Colin Webster, "Marginalized white ethnicity, race and crime", Theoretical Criminology, Volume: 12 issue: 3, page(s): 293-312, August 1, 2008

- ^ particularly the chapter titled "Borderlands to the Backcountry: The Flight from Middle Britain and Northern Ireland, 1717-1775"

- ^ David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, (ISBN 0-19-506905-6), Oxford University Press, 1989.

- ^ Edge, John T. (2007) "White Trash Cooking, Twenty Years Later", Southern Quarterly. 44(2): pp. 88-94; Smith (2004)

- ^ Mickler, Ernest Matthew (2011)White Trash Cooking (new ed. 2011)

- ^ Inness, Sherrie A. (2006) Secret Ingredients: Race, Gender, and Class at the Dinner Table. p. 147

- ^ Bledsoe, Erik (2000) "The Rise of Southern Redneck and White Trash Writers", Southern Cultures 6#1 pp. 68-90

- ^ Hollibaugh, Amber L. (2000). My Dangerous Desires: A Queer Girl Dreaming Her Way Home. Duke University Press. pp. 12, 209. ISBN 978-0822326199.

- ^ Hester, Jessica (2008). "Progressivism, Suffragists and Constructions of Race: Evelyn Greenleaf Sutherland's 'Po' White Trash'". Women's Writing. 15 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1080/09699080701871443.

- ^ Henry, O (1907). "Shoes". The best short stories of O. Henry. Random House. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-679-601227. Archived from the original on 1997-01-01.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Oxford American.com

- ^ Wilson, William Juliusin Cashmore, Ernest and Jennings, James eds. (2001) Racism: Essential Readings p.188

- ^ a b Kolin, Philip C. (2007) Contemporary African American Women Playwrights. p.29

- ^ Roediger, David R. (1999) Take Black on White: Black Writers on What It Means to be White pp.13, 123

- ^ Obiakor, Festus E. and Ford, Bridgie Alexis (2002) Creating Successful Learning Environments for African-American Learners With Exceptionalities p.198

- ^ Prahlad, Anand (2006) The Greenwood Encyclopedia of African American Folklore. volume 2, p.966

- ^ Nolen, Claude H. (2005) African American Southerners in Slavery, Civil War and Reconstruction. p.81

- ^ Jackson, Chuck (2000). "Waste and Whiteness: Zora Neale Hurston and the Politics of Eugenics". African American Review. 34 (4): 639–660. doi:10.2307/2901423. JSTOR 2901423.

Bibliography

- Berger, Maurice (2000). White Lies: Race and the Myths of Whiteness. ISBN 0-374-52715-6

- Goad, Jim (1998). The Redneck Manifesto: How Hillbillies Hicks and White Trash Became Americas Scapegoats. ISBN 0-684-83864-8

- explores the history of the pejorative term "White trash", as well as detailing the history and class issues related to the impoverished European diaspora in North America.

- Hartigan, John, Jr. (2005) Odd Tribes: Toward a Cultural Analysis of White People. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3597-2

- Hartigan, John, Jr. (2003) "Who are these white people?: 'Rednecks,' 'Hillbillies,' and 'White Trash' as marked racial subjects" in Doane, Ashley W. and Bonilla-Silva, Edouardo eds. (2003). White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism. Psychology Press. pp. 95–111. ISBN 9780415935838.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Isenberg, Nancy (2016) White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-312967-7

- Rasmussen, Dana (2011). Things White Trash People Like: The Stereotypes of America's Poor White Trash. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781241610449.

- Smith, Dina (2004) "Cultural Studies' Misfit: White Trash Studies", Mississippi Quarterly. 57(3): pp. 369–387

- traces the emergence of 'white trash studies' as a scholarly field by placing representative 20th-century popular images of 'white trash' in their Southern economic and cultural contexts.

- Sullivan, Nell (2003) "Academic Constructions of 'White Trash'" in Adair, Vivyan Campbell, and Sandra L. Dahlberg, eds. (2003) Reclaiming Class. Women, Poverty, and the Promise of Higher Education in America. pp 53-66. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-59213-021-6

- Taylor, Kirstine (March 2015) "Untimely Subjects: White Trash and the Making of Racial Innocence in the Postwar South" American Quarterly 67. pp.55–79

- Wray, Matt and Newitz, Annalee eds. (1997). White Trash: Race and Class in America. ISBN 0-415-91692-5

- Wray, Matt (2006) Not Quite White: White Trash and the Boundaries of Whiteness

- Pitcher, Ben (2007) "The Problem with White Trash" (review of Not Quite White) DarkMatter Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3873-4

External links

- Allison, Dorothy "A Question of Class"

- Entertainers loved By trailer trash (videos)

- American phraseology

- Anti-European and anti-white slurs

- Class-related slurs

- Ethnic and racial stereotypes

- Ethnic and racial stereotypes in the United States

- Ethnic and religious slurs

- Intersectional racial topics

- Intersectional social class topics

- Social class subcultures

- Stereotypes of rural people

- Stereotypes of white Americans

- Stereotypes of the working class