Anatolia

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 39°N 35°E / 39°N 35°E |

| Area | 756,000 km2 (292,000 sq mi)[3] |

| Administration | |

Turkey | |

| Largest city | Istanbul (pop. 15,067,724[4]) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Anatolian |

| Languages | Turkish, Kurdish, Armenian, Greek, Arabic, Kabardian, various others |

| Ethnic groups | Turks, Kurds, Armenians, Greeks, Arabs, Laz, various others |

Anatolia (from Greek: Ἀνατολή, Anatolḗ, "east" or "[sun]rise"; Template:Lang-tr), also known as Asia Minor (Medieval and Modern Greek: Μικρά Ἀσία, Mikrá Asía, "small Asia"; Template:Lang-tr), Asian Turkey, the Anatolian peninsula or the Anatolian plateau, is a large peninsula in West Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It makes up the majority of modern-day Turkey. The region is bounded by the Black Sea to the north, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Armenian Highlands to the east and the Aegean Sea to the west. The Sea of Marmara forms a connection between the Black and Aegean seas through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits and separates Anatolia from Thrace on the Balkan peninsula of Europe.

The eastern border of Anatolia is traditionally held to be a line between the Gulf of Alexandretta and the Black Sea, bounded by the Armenian Highland to the east and Mesopotamia to the southeast. Thus, traditionally Anatolia is the territory that comprises approximately the western two-thirds of the Asian part of Turkey. Today, Anatolia is also often considered to be synonymous with Asian Turkey, which comprises almost the entire country;[5] its eastern and southeastern borders are widely taken to be Turkey's eastern border.[6] By some definitions, the Armenian Highlands lies beyond the boundary of the Anatolian plateau. The official name of this inland region is the Eastern Anatolia Region.[7][8]

The ancient inhabitants of Anatolia spoke the now-extinct Anatolian languages, which were largely replaced by the Greek language starting from classical antiquity and during the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods. Major Anatolian languages included Hittite, Luwian, and Lydian, among other more poorly attested relatives. The Turkification of Anatolia began under the Seljuk Empire in the late 11th century and continued under the Ottoman Empire between the late 13th and early 20th centuries. However, various non-Turkic languages continue to be spoken by minorities in Anatolia today, including Kurdish, Neo-Aramaic, Armenian, Arabic, Laz, Georgian and Greek. Other ancient peoples in the region included Galatians, Hurrians, Assyrians, Hattians, Cimmerians, as well as Ionian, Dorian and Aeolian Greeks.

Geography

Traditionally, Anatolia is considered to extend in the east to an indefinite line running from the Gulf of Alexandretta to the Black Sea,[9] coterminous with the Anatolian Plateau. This traditional geographical definition is used, for example, in the latest edition of Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary.[1] Under this definition, Anatolia is bounded to the east by the Armenian Highlands, and the Euphrates before that river bends to the southeast to enter Mesopotamia.[2] To the southeast, it is bounded by the ranges that separate it from the Orontes valley in Syria and the Mesopotamian plain.[2]

Following the Armenian genocide, Ottoman Armenia was renamed "Eastern Anatolia" by the newly established Turkish government.[10][11] Vazken Davidian terms the expanded use of "Anatolia" to apply to territory formerly referred to as Armenia an "ahistorical imposition", and notes that a growing body of literature is uncomfortable with referring to the Ottoman East as "Eastern Anatolia".[12]

The highest mountain in "Eastern Anatolia" (on the Armenian Plateau) is Mount Ararat (5123 m).[13] The Euphrates, Araxes, Karasu and Murat rivers connect the Armenian Plateau to the South Caucasus and the Upper Euphrates Valley. Along with the Çoruh, these rivers are the longest in "Eastern Anatolia".[14]

Etymology

The English-language name Anatolia derives from the Greek Ἀνατολή (Anatolḗ) meaning "the East" or more literally "sunrise" (comparable to the Latin-derived terms "levant" and "orient").[15][16] The precise reference of this term has varied over time, perhaps originally referring to the Aeolian, Ionian and Dorian colonies on the west coast of Asia Minor. In the Byzantine Empire, the Anatolic Theme (Ἀνατολικόν θέμα "the Eastern theme") was a theme covering the western and central parts of Turkey's present-day Central Anatolia Region, centered around Iconium, but ruled from the city of Amorium.[17][18]

The term "Anatolia", with its -ia ending, is probably a Medieval Latin innovation.[16] The modern Turkish form Anadolu derives directly from the Greek name Aνατολή (Anatolḗ). The Russian male name Anatoly, the French Anatole and plain Anatol, all stemming from saints Anatolius of Laodicea (d. 283) and Anatolius of Constantinople (d. 458; the first Patriarch of Constantinople), share the same linguistic origin.

Names

The oldest known reference to Anatolia – as "Land of the Hatti" – appears on Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets from the period of the Akkadian Empire (2350–2150 BC).[citation needed] The first recorded name the Greeks used for the Anatolian peninsula, though not particularly popular at the time, was Ἀσία (Asía),[19] perhaps from an Akkadian expression for the "sunrise", or possibly echoing the name of the Assuwa league in western Anatolia.[citation needed] The Romans used it as the name of their province, comprising the west of the peninsula plus the nearby Aegean islands. As the name "Asia" broadened its scope to apply to the vaster region east of the Mediterranean, some Greeks in Late Antiquity came to use the name Asia Minor (Μικρὰ Ἀσία, Mikrà Asía), meaning "Lesser Asia", to refer to present-day Anatolia, whereas the administration of the Empire preferred the description Ἀνατολή (Anatolḗ "the East").

The endonym Ῥωμανία (Rhōmanía "the land of the Romans, i. e. the Eastern Roman Empire") was understood as another name for the province by the invading Seljuq Turks, who founded a Sultanate of Rûm in 1076. Thus (land of the) Rûm became another name for Anatolia. By the 12th century Europeans had started referring to Anatolia as Turchia.[20]

During the era of the Ottoman Empire, mapmakers outside the Empire referred to the mountainous plateau in eastern Anatolia as Armenia. Other contemporary sources called the same area Kurdistan.[21] Geographers have variously used the terms east Anatolian plateau and Armenian plateau to refer to the region, although the territory encompassed by each term largely overlaps with the other. According to archaeologist Lori Khatchadourian, this difference in terminology "primarily result[s] from the shifting political fortunes and cultural trajectories of the region since the nineteenth century."[22]

Turkey's First Geography Congress in 1941 created two geographical regions of Turkey to the east of the Gulf of Iskenderun-Black Sea line named the Eastern Anatolia Region and the Southeastern Anatolia Region,[23] the former largely corresponding to the western part of the Armenian Highlands, the latter to the northern part of the Mesopotamian plain. According to Richard Hovannisian, this changing of toponyms was "necessary to obscure all evidence" of Armenian presence as part of a campaign of genocide denial embarked upon by the newly established Turkish government and what Hovannisian calls its "foreign collaborators".[24]

History

Prehistory

Human habitation in Anatolia dates back to the Paleolithic.[26] Neolithic Anatolia has been proposed as the homeland of the Indo-European language family, although linguists tend to favour a later origin in the steppes north of the Black Sea. However, it is clear that the Anatolian languages, the earliest attested branch of Indo-European, have been spoken in Anatolia since at least the 19th century BC.[citation needed]

Ancient Near East (Bronze and Iron Ages)

Hattians and Hurrians

The earliest historical records of Anatolia stem from the southeast of the region and are from the Mesopotamian-based Akkadian Empire during the reign of Sargon of Akkad in the 24th century BC. Scholars generally believe the earliest indigenous populations of Anatolia were the Hattians and Hurrians. The Hattians spoke a language of unclear affiliation, and the Hurrian language belongs to a small family called Hurro-Urartian, all these languages now being extinct; relationships with indigenous languages of the Caucasus have been proposed[27] but are not generally accepted. The region was famous for exporting raw materials, and areas of Hattian- and Hurrian-populated southeast Anatolia were colonised by the Akkadians.[28]

Assyrian Empire (21st–18th centuries BC)

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire in the mid-21st century BC, the Assyrians, who were the northern branch of the Akkadian people, colonised parts of the region between the 21st and mid-18th centuries BC and claimed its resources, notably silver. One of the numerous cuneiform records dated circa 20th century BC, found in Anatolia at the Assyrian colony of Kanesh, uses an advanced system of trading computations and credit lines.[28]

Hittite Kingdom and Empire (17th–12th centuries BC)

Unlike the Akkadians and their descendants, the Assyrians, whose Anatolian possessions were peripheral to their core lands in Mesopotamia, the Hittites were centred at Hattusa (modern Boğazkale) in north-central Anatolia by the 17th century BC. They were speakers of an Indo-European language, the Hittite language, or nesili (the language of Nesa) in Hittite. The Hittites originated of local ancient cultures that grew in Anatolia, in addition to the arrival of Indo-European languages. Attested for the first time in the Assyrian tablets of Nesa around 2000BC, they conquered Hattusa in the 18th century BC, imposing themselves over Hattian- and Hurrian-speaking populations. According to the widely accepted Kurgan theory on the Proto-Indo-European homeland, however, the Hittites (along with the other Indo-European ancient Anatolians) were themselves relatively recent immigrants to Anatolia from the north. However, they did not necessarily displace the population genetically, they would rather assimilate into the former peoples' culture, preserving the Hittite language.

The Hittites adopted the cuneiform script, invented in Mesopotamia. During the Late Bronze Age circa 1650 BC, they created a kingdom, the Hittite New Kingdom, which became an empire in the 14th century BC after the conquest of Kizzuwatna in the south-east and the defeat of the Assuwa league in western Anatolia. The empire reached its height in the 13th century BC, controlling much of Asia Minor, northwestern Syria and northwest upper Mesopotamia. They failed to reach the Anatolian coasts of the Black Sea, however, as a non-Indo-European people, the semi-nomadic pastoralist and tribal Kaskians, had established themselves there, displacing earlier Palaic-speaking Indo-Europeans.[29] Much of the history of the Hittite Empire concerned war with the rival empires of Egypt, Assyria and the Mitanni.[30]

The Egyptians eventually withdrew from the region after failing to gain the upper hand over the Hittites and becoming wary of the power of Assyria, which had destroyed the Mitanni Empire.[30] The Assyrians and Hittites were then left to battle over control of eastern and southern Anatolia and colonial territories in Syria. The Assyrians had better success than the Egyptians, annexing much Hittite (and Hurrian) territory in these regions.[31]

Neo-Hittite kingdoms (c. 1180–700 BC)

After 1180 BC, during the Late Bronze Age collapse, the Hittite empire disintegrated into several independent Syro-Hittite states, subsequent to losing much territory to the Middle Assyrian Empire and being finally overrun by the Phrygians, another Indo-European people who are believed to have migrated from the Balkans. The Phrygian expansion into southeast Anatolia was eventually halted by the Assyrians, who controlled that region.[31]

- Arameans

Arameans encroached over the borders of south central Anatolia in the century or so after the fall of the Hittite empire, and some of the Syro-Hittite states in this region became an amalgam of Hittites and Arameans. These became known as Syro-Hittite states.

- Luwians

Another Indo-European people, the Luwians, rose to prominence in central and western Anatolia circa 2000 BC. Their language belonged to the same linguistic branch as Hittite.[32] The general consensus amongst scholars is that Luwian was spoken across a large area of western Anatolia, including (possibly) Wilusa (Troy), the Seha River Land (to be identified with the Hermos and/or Kaikos valley), and the kingdom of Mira-Kuwaliya with its core territory of the Maeander valley.[33] From the 9th century BC, Luwian regions coalesced into a number of states such as Lydia, Caria and Lycia, all of which had Hellenic influence.

Neo-Assyrian Empire (10th–7th centuries BC)

From the 10th to late 7th centuries BC, much of Anatolia (particularly the southeastern regions) fell to the Neo-Assyrian Empire, including all of the Syro-Hittite states, Tabal, Kingdom of Commagene, the Cimmerians and Scythians and swathes of Cappadocia.

The Neo-Assyrian empire collapsed due to a bitter series of civil wars followed by a combined attack by Medes, Persians, Scythians and their own Babylonian relations. The last Assyrian city to fall was Harran in southeast Anatolia. This city was the birthplace of the last king of Babylon, the Assyrian Nabonidus and his son and regent Belshazzar. Much of the region then fell to the short-lived Iran-based Median Empire, with the Babylonians and Scythians briefly appropriating some territory.

Cimmerian and Scythian invasions (8th–7th centuries BC)

From the late 8th century BC, a new wave of Indo-European-speaking raiders entered northern and northeast Anatolia: the Cimmerians and Scythians. The Cimmerians overran Phrygia and the Scythians threatened to do the same to Urartu and Lydia, before both were finally checked by the Assyrians.

Greek West

The north-western coast of Anatolia was inhabited by Greeks of the Achaean/Mycenaean culture from the 20th century BC, related to the Greeks of south eastern Europe and the Aegean.[35] Beginning with the Bronze Age collapse at the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the west coast of Anatolia was settled by Ionian Greeks, usurping the area of the related but earlier Mycenaean Greeks. Over several centuries, numerous Ancient Greek city-states were established on the coasts of Anatolia. Greeks started Western philosophy on the western coast of Anatolia (Pre-Socratic philosophy).[35]

Classical Antiquity

In classical antiquity, Anatolia was described by Herodotus and later historians as divided into regions that were diverse in culture, language and religious practices.[36] The northern regions included Bithynia, Paphlagonia and Pontus; to the west were Mysia, Lydia and Caria; and Lycia, Pamphylia and Cilicia belonged to the southern shore. There were also several inland regions: Phrygia, Cappadocia, Pisidia and Galatia.[36] Languages spoken included the late surviving Anatolic languages Isaurian[37] and Pisidian, Greek in Western and coastal regions, Phrygian spoken until the 7th century CE,[38] local variants of Thracian in the Northwest, the Galatian variant of Gaulish in Galatia until the 6th century CE,[39][40][41] Cappadocian[42] and Armenian in the East, and Kartvelian languages in the Northeast.

Anatolia is known as the birthplace of minted coinage (as opposed to unminted coinage, which first appears in Mesopotamia at a much earlier date) as a medium of exchange, some time in the 7th century BC in Lydia. The use of minted coins continued to flourish during the Greek and Roman eras.[43][44]

During the 6th century BC, all of Anatolia was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire, the Persians having usurped the Medes as the dominant dynasty in Iran. In 499 BC, the Ionian city-states on the west coast of Anatolia rebelled against Persian rule. The Ionian Revolt, as it became known, though quelled, initiated the Greco-Persian Wars, which ended in a Greek victory in 449 BC, and the Ionian cities regained their independence. By the Peace of Antalcidas (387 BC), which ended the Corinthian War, Persia regained control over Ionia.[45][46]

In 334 BC, the Macedonian Greek king Alexander the Great conquered the peninsula from the Achaemenid Persian Empire.[47] Alexander's conquest opened up the interior of Asia Minor to Greek settlement and influence.

Following the death of Alexander and the breakup of his empire, Anatolia was ruled by a series of Hellenistic kingdoms, such as the Attalids of Pergamum and the Seleucids, the latter controlling most of Anatolia. A period of peaceful Hellenization followed, such that the local Anatolian languages had been supplanted by Greek by the 1st century BC. In 133 BC the last Attalid king bequeathed his kingdom to the Roman Republic, and western and central Anatolia came under Roman control, but Hellenistic culture remained predominant. Further annexations by Rome, in particular of the Kingdom of Pontus by Pompey, brought all of Anatolia under Roman control, except for the eastern frontier with the Parthian Empire, which remained unstable for centuries, causing a series of wars, culminating in the Roman-Parthian Wars.

Early Christian Period

After the division of the Roman Empire, Anatolia became part of the East Roman, or Byzantine Empire. Anatolia was one of the first places where Christianity spread, so that by the 4th century AD, western and central Anatolia were overwhelmingly Christian and Greek-speaking. For the next 600 years, while Imperial possessions in Europe were subjected to barbarian invasions, Anatolia would be the center of the Hellenic world.[citation needed]

It was one of the wealthiest and most densely populated places in the Late Roman Empire. Anatolia's wealth grew during the 4th and 5th centuries thanks, in part, to the Pilgrim's Road that ran through the peninsula. Literary evidence about the rural landscape has come down to us from the hagiographies of 6th century Nicholas of Sion and 7th century Theodore of Sykeon. Large urban centers included Ephesus, Pergamum, Sardis and Aphrodisias. Scholars continue to debate the cause of urban decline in the 6th and 7th centuries variously attributing it to the Plague of Justinian (541), and the 7th century Persian incursion and Arab conquest of the Levant.[48]

In the ninth and tenth century a resurgent Byzantine Empire regained its lost territories, including even long lost territory such as Armenia and Syria (ancient Aram).[citation needed]

Medieval Period

In the 10 years following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Seljuk Turks from Central Asia migrated over large areas of Anatolia, with particular concentrations around the northwestern rim.[49] The Turkish language and the Islamic religion were gradually introduced as a result of the Seljuk conquest, and this period marks the start of Anatolia's slow transition from predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking, to predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking (although ethnic groups such as Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians remained numerous and retained Christianity and their native languages). In the following century, the Byzantines managed to reassert their control in western and northern Anatolia. Control of Anatolia was then split between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm, with the Byzantine holdings gradually being reduced.[50]

In 1255, the Mongols swept through eastern and central Anatolia, and would remain until 1335. The Ilkhanate garrison was stationed near Ankara.[50][51] After the decline of the Ilkhanate from 1335–1353, the Mongol Empire's legacy in the region was the Uyghur Eretna Dynasty that was overthrown by Kadi Burhan al-Din in 1381.[52]

By the end of the 14th century, most of Anatolia was controlled by various Anatolian beyliks. Smyrna fell in 1330, and the last Byzantine stronghold in Anatolia, Philadelphia, fell in 1390. The Turkmen Beyliks were under the control of the Mongols, at least nominally, through declining Seljuk sultans.[53][54] The Beyliks did not mint coins in the names of their own leaders while they remained under the suzerainty of the Mongol Ilkhanids.[55] The Osmanli ruler Osman I was the first Turkish ruler who minted coins in his own name in 1320s; they bear the legend "Minted by Osman son of Ertugrul".[56] Since the minting of coins was a prerogative accorded in Islamic practice only to a sovereign, it can be considered that the Osmanli, or Ottoman Turks, had become formally independent from the Mongol Khans.[57]

Ottoman Empire

Among the Turkish leaders, the Ottomans emerged as great power under Osman I and his son Orhan I.[58][59] The Anatolian beyliks were successively absorbed into the rising Ottoman Empire during the 15th century.[60] It is not well understood how the Osmanlı, or Ottoman Turks, came to dominate their neighbours, as the history of medieval Anatolia is still little known.[61] The Ottomans completed the conquest of the peninsula in 1517 with the taking of Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum) from the Knights of Saint John.[62]

Modern times

With the acceleration of the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century, and as a result of the expansionist policies of the Russian Empire in the Caucasus, many Muslim nations and groups in that region, mainly Circassians, Tatars, Azeris, Lezgis, Chechens and several Turkic groups left their homelands and settled in Anatolia. As the Ottoman Empire further shrank in the Balkan regions and then fragmented during the Balkan Wars, much of the non-Christian populations of its former possessions, mainly Balkan Muslims (Bosnian Muslims, Albanians, Turks, Muslim Bulgarians and Greek Muslims such as the Vallahades from Greek Macedonia), were resettled in various parts of Anatolia, mostly in formerly Christian villages throughout Anatolia.

A continuous reverse migration occurred since the early 19th century, when Greeks from Anatolia, Constantinople and Pontus area migrated toward the newly independent Kingdom of Greece, and also towards the United States, southern part of the Russian Empire, Latin America and rest of Europe.

Following the Russo-Persian Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) and the incorporation of the Eastern Armenia into the Russian Empire, another migration involved the large Armenian population of Anatolia, which recorded significant migration rates from Western Armenia (Eastern Anatolia) toward the Russian Empire, especially toward its newly established Armenian provinces.

Anatolia remained multi-ethnic until the early 20th century (see the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire). During World War I, the Armenian Genocide, the Greek genocide (especially in Pontus), and the Assyrian genocide almost entirely removed the ancient indigenous communities of Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian populations in Anatolia and surrounding regions. Following the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, most remaining ethnic Anatolian Greeks were forced out during the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Of the remainder, most have left Turkey since then, leaving fewer than 5,000 Greeks in Anatolia today. Since the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, Anatolia has been within Turkey, its inhabitants being mainly Turks and Kurds (see demographics of Turkey and history of Turkey).

Geology

Anatolia's terrain is structurally complex. A central massif composed of uplifted blocks and downfolded troughs, covered by recent deposits and giving the appearance of a plateau with rough terrain, is wedged between two folded mountain ranges that converge in the east. True lowland is confined to a few narrow coastal strips along the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Black Sea coasts. Flat or gently sloping land is rare and largely confined to the deltas of the Kızıl River, the coastal plains of Çukurova and the valley floors of the Gediz River and the Büyük Menderes River as well as some interior high plains in Anatolia, mainly around Lake Tuz (Salt Lake) and the Konya Basin (Konya Ovasi).

There are two mountain ranges in southern Anatolia: the Taurus and the Zagros mountains.[63]

Climate

- Temperatures of Anatolia

-

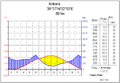

Ankara (central Anatolia)

-

Antalya (southern Anatolia)

-

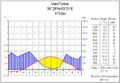

Van (eastern Anatolia)

Anatolia has a varied range of climates. The central plateau is characterized by a continental climate, with hot summers and cold snowy winters. The south and west coasts enjoy a typical Mediterranean climate, with mild rainy winters, and warm dry summers.[64] The Black Sea and Marmara coasts have a temperate oceanic climate, with cool foggy summers and much rainfall throughout the year.

Ecoregions

There is a diverse number of plant and animal communities.

The mountains and coastal plain of northern Anatolia experiences humid and mild climate. There are temperate broadleaf, mixed and coniferous forests. The central and eastern plateau, with its drier continental climate, has deciduous forests and forest steppes. Western and southern Anatolia, which have a Mediterranean climate, contain Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub ecoregions.

- Euxine-Colchic deciduous forests: These temperate broadleaf and mixed forests extend across northern Anatolia, lying between the mountains of northern Anatolia and the Black Sea. They include the enclaves of temperate rainforest lying along the southeastern coast of the Black Sea in eastern Turkey and Georgia.[65]

- Northern Anatolian conifer and deciduous forests: These forests occupy the mountains of northern Anatolia, running east and west between the coastal Euxine-Colchic forests and the drier, continental climate forests of central and eastern Anatolia.[66]

- Central Anatolian deciduous forests: These forests of deciduous oaks and evergreen pines cover the plateau of central Anatolia.[67]

- Central Anatolian steppe: These dry grasslands cover the drier valleys and surround the saline lakes of central Anatolia, and include halophytic (salt tolerant) plant communities.[68]

- Eastern Anatolian deciduous forests: This ecoregion occupies the plateau of eastern Anatolia. The drier and more continental climate is beneficial for steppe-forests dominated by deciduous oaks, with areas of shrubland, montane forest, and valley forest.[69]

- Anatolian conifer and deciduous mixed forests: These forests occupy the western, Mediterranean-climate portion of the Anatolian plateau. Pine forests and mixed pine and oak woodlands and shrublands are predominant.[70]

- Aegean and Western Turkey sclerophyllous and mixed forests: These Mediterranean-climate forests occupy the coastal lowlands and valleys of western Anatolia bordering the Aegean Sea. The ecoregion has forests of Turkish pine (Pinus brutia), oak forests and woodlands, and maquis shrubland of Turkish pine and evergreen sclerophyllous trees and shrubs, including Olive (Olea europaea), Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo), Arbutus andrachne, Kermes Oak (Quercus coccifera), and Bay Laurel (Laurus nobilis).[71]

- Southern Anatolian montane conifer and deciduous forests: These mountain forests occupy the Mediterranean-climate Taurus Mountains of southern Anatolia. Conifer forests are predominant, chiefly Anatolian black pine (Pinus nigra), Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani), Taurus fir (Abies cilicica), and juniper (Juniperus foetidissima and J. excelsa). Broadleaf trees include oaks, hornbeam, and maples.[72]

- Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests: This ecoregion occupies the coastal strip of southern Anatolia between the Taurus Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea. Plant communities include broadleaf sclerophyllous maquis shrublands, forests of Aleppo Pine (Pinus halepensis) and Turkish Pine (Pinus brutia), and dry oak (Quercus spp.) woodlands and steppes.[73]

Demographics

Almost 80% of the people currently residing in Anatolia are Turks. Kurds (Kurmanjis and Zazas) constitute a major community in southeastern Anatolia,[74] and are the largest ethnic minority. Abkhazians, Albanians, Arabs, Arameans, Armenians, Assyrians, Azerbaijanis, Bosnian Muslims, Circassians, Gagauz, Georgians, Serbs, Greeks, Hemshin, Jews, Laz, Levantines, Pomaks, and a number of other ethnic groups also live in Anatolia in smaller numbers.[citation needed]

Cuisine

Bamia is a traditional Anatolian-era stew dish prepared using lamb, okra and tomatoes as primary ingredients.[75]

See also

- Aeolis

- Alacahöyük

- Anatolian hypothesis

- Anatolian languages

- Anatolianism

- Anatolian leopard

- Anatolian Plate

- Anatolian Shepherd

- Anatolian beyliks

- Ancient kingdoms of Anatolia

- Antigonid dynasty

- Attalid dynasty

- Bithynia

- Byzantine Empire

- Cappadocia

- Caria

- Çatalhöyük

- Cilicia

- Doris (Asia Minor)

- Empire of Nicaea

- Empire of Trebizond

- Ephesus

- Galatia

- Gordium

- Halicarnassus

- Hattusa

- History of Anatolia

- Hittites

- Ionia

- Lycaonia

- Lycia

- Lydia

- Midas

- Miletus

- Myra

- Mysia

- Pamphylia

- Paphlagonia

- Pentarchy

- Pergamon

- Phrygia

- Pisidia

- Pontic Greeks

- Pontus

- Rumi

- Saint Anatolia

- Saint John

- Saint Nicholas

- Saint Paul

- Sardis

- Seleucid Empire

- Great Seljuq Empire

- Seven churches of Asia

- Seven Sleepers

- Sultanate of Rum

- Tarsus

- Troad

- Troy

- Turkic migration

References

- ^ a b Hopkins, Daniel J.; Staff, Merriam-Webster; 편집부 (2001). Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. p. 46. ISBN 0-87779-546-0. Retrieved 19 May 2001.

- ^ a b c Stephen Mitchell, Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor. The Celts in Anatolia and the impact of Roman rule. Clarendon Press, 24 August 1995 – 266 pages. ISBN 978-0198150299 [1]

- ^ Sansal, Burak. "History of Anatolia".

- ^ (TÜİK), Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. "Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu, Adrese Dayalı Nüfus Kayıt Sistemi Sonuçları, 2018".

- ^ Hooglund, Eric (2004). "Anatolia". Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa. Macmillan/Gale – via Encyclopedia.com.

Anatolia comprises more than 95 percent of Turkey's total land area.

- ^ Khatchadourian, Lori (5 September 2011). McMahon, Gregory; Steadman, Sharon (eds.). "The Iron Age in Eastern Anatolia". The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0020. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical dictionary of Armenia (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. pp. 336–8. ISBN 978-0810874503.

- ^ Grierson, Otto Mørkholm ; edited by Philip; Westermark, Ulla (1991). Early Hellenistic coinage : from the accession of Alexander to the Peace of Apamea (336–188 B.C.) (Repr. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0521395045.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Philipp Niewohner (17 March 2017). The Archaeology of Byzantine Anatolia: From the End of Late Antiquity until the Coming of the Turks. Oxford University Press. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-19-061047-0.

- ^ Sahakyan, Lusine (2010). Turkification of the Toponyms in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. Montreal: Arod Books. ISBN 978-0969987970.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard (2007). The Armenian genocide cultural and ethical legacies. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1412835923.

- ^ Vazken Khatchig Davidian, "Imagining Ottoman Armenia: Realism and Allegory in Garabed Nichanian's Provincial Wedding in Moush and Late Ottoman Art Criticism", p7 & footnote 34, in Études arméniennes contemporaines volume 6, 2015.

- ^ Fevzi Özgökçe; Kit Tan; Vladimir Stevanović (2005). "A new subspecies of Silene acaulis (Caryophyllaceae) from East Anatolia, Turkey". Annales Botanici Fennici. 42 (2): 143–149. JSTOR 23726860.

- ^ Palumbi, Giulio (5 September 2011). McMahon, Gregory; Steadman, Sharon (eds.). "The Chalcolithic of Eastern Anatolia". The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0009. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott. "A Greek-English Lexicon".

- ^ a b "Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ^ "On the First Thema, called Anatolikón. This theme is called Anatolikón or Theme of the Anatolics, not because it is above and in the direction of the east where the sun rises, but because it lies to the East of Byzantium and Europe." Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, De Thematibus, ed. A. Pertusi. Vatican: Vatican Library, 1952, p. 59 ff.

- ^ John Haldon, Byzantium, a History, 2002, p. 32.

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, Ἀσία, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (20 September 2018). "Anatolia". The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780191866326.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-186632-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (22 March 2015). "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1.

- ^ Khatchadourian, Lori (5 September 2011). McMahon, Gregory; Steadman, Sharon (eds.). "The Iron Age in Eastern Anatolia". The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0020. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Ali Yiğit, "Geçmişten Günümüze Türkiye'yi Bölgelere Ayıran Çalışmalar ve Yapılması Gerekenler", Ankara Üniversitesi Türkiye Coğrafyası Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi, IV. Ulural Coğrafya Sempozyumu, "Avrupa Birliği Sürecindeki Türkiye'de Bölgesel Farklılıklar", pp. 34–35.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1998). Remembrance and Denial: The Case of the Armenian Genocide. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2777-7.

- ^ "Çatalhöyük added to UNESCO World Heritage List". Global Heritage Fund. 3 July 2012. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Stiner, Mary C.; Kuhn, Steven L.; Güleç, Erksin (2013). "Early Upper Paleolithic shell beads at Üçağızlı Cave I (Turkey): Technology and the socioeconomic context of ornament life-histories". Journal of Human Evolution. 64 (5): 380–398. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.01.008. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 23481346.

- ^ Bryce 2005:12

- ^ a b Freeman, Charles (1999). Egypt, Greece and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-872194-9.

- ^ Carruba, O. Das Palaische. Texte, Grammatik, Lexikon. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1970. StBoT 10

- ^ a b Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ^ a b Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books, 1966.

- ^ Melchert 2003

- ^ Watkins 1994; id. 1995:144–51; Starke 1997; Melchert 2003; for the geography Hawkins 1998

- ^ CAHN, HERBERT A.; GERIN, DOMINIQUE (1988). "Themistocles at Magnesia". The Numismatic Chronicle (1966–). 148: 20 & Plate 3. JSTOR 42668124.

- ^ a b Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times

- ^ a b Yavuz, Mehmet Fatih (2010). "Anatolia". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195170726.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Honey, Linda. "Justifiably Outraged or Simply Outrageous? The Isaurian Incident of Ammianus Marcellinus". Violence in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Practices. p. 50.

- ^ Swain, Simon; Adams, J. Maxwell; Janse, Mark (2002). Bilingualism in Ancient Society: Language Contact and the Written Word. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 246–266. ISBN 0-19-924506-1.

- ^ Freeman, Philip, The Galatian Language, Edwin Mellen, 2001, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Clackson, James. "Language maintenance and language shift in the Mediterranean world during the Roman Empire." Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds (2012): 36–57. Page 46: The second testimonium for the late survival of Galatian appears in the Life of Saint Euthymius, who died in ad 487.

- ^ Norton, Tom. [2] | A question of identity: who were the Galatians?. University of Wales. Page 62: The final reference to Galatian comes two hundred years later in the sixth century CE when Cyril of Scythopolis attests that Galatian was still being spoken eight hundred years after the Galatians arrived in Asia Minor. Cyril tells of the temporary possession of a monk from Galatia by Satan and rendered speechless, but when he recovered he spoke only in his native Galatian when questioned: ‘If he were pressed, he spoke only in Galatian’.180 After this, the rest is silence, and further archaeological or literary discoveries are awaited to see if Galatian survived any later. In this regard, the example of Crimean Gothic is instructive. It was presumed to have died out in the fifth century CE, but the discovery of a small corpus of the language dating from the sixteenth century altered this perception.

- ^ J. Eric Cooper, Michael J. Decker, Life and Society in Byzantine Cappadocia ISBN 0230361064, p. 14

- ^ Howgego, C. J. (1995). Ancient History from Coins. ISBN 978-0-415-08992-0.

- ^ Asia Minor Coins - an index of Greek and Roman coins from Asia Minor (ancient Anatolia)

- ^ Dandamaev, M. A. (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. Brill. p. 294. ISBN 978-9004091726.

- ^ Schmitt, R. (1986). "ARTAXERXES II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 656–658.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2010). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Thonemann, Peter ThonemannPeter (22 March 2018). "Anatolia". The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Angold, Michael (1997). The Byzantine Empire 1025–1204. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-582-29468-4.

- ^ a b H. M. Balyuzi Muḥammad and the course of Islám, p. 342

- ^ John Freely Storm on Horseback: The Seljuk Warriors of Turkey, p. 83

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth-The new Islamic dynasties: a chronological and genealogical manual, p. 234

- ^ Mehmet Fuat Köprülü, Gary Leiser-The origins of the Ottoman Empire, p. 33

- ^ Peter Partner God of battles: holy wars of Christianity and Islam, p. 122

- ^ Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire, p. 13

- ^ Artuk – Osmanli Beyliginin Kurucusu, 27f

- ^ Pamuk – A Monetary History, pp. 30–31

- ^ "Osman I | Ottoman sultan". Retrieved 23 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - ^ "Orhan | Ottoman sultan". Retrieved 23 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - ^ Fleet, Kate (2010). "The rise of the Ottomans". The rise of the Ottomans (Chapter 11) – The New Cambridge History of Islam. pp. 313–331. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521839570.013. ISBN 9781139056151. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Finkel, Caroline (2007). Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-465-00850-6. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ electricpulp.com. "HALICARNASSUS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Cemen, Ibrahim; Yilmaz, Yucel (3 March 2017). Active Global Seismology: Neotectonics and Earthquake Potential of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-94501-8.

- ^ Prothero, W.G. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office.

- ^ "Euxine-Colchic deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Northern Anatolian conifer and deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Central Anatolian deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Central Anatolian steppe". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Eastern Anatolian deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Anatolian conifer and deciduous mixed forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Aegean and Western Turkey sclerophyllous and mixed forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Southern Anatolian montane conifer and deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "A Kurdish Majority in Turkey Within One Generation?". 6 May 2012.

- ^ Webb, L.S.; Roten, L.G. (2009). The Multicultural Cookbook for Students. EBL-Schweitzer. ABC-CLIO. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-0-313-37559-0.

Bibliography

- Steadman, Sharon R.; McMahon, Gregory (2011). McMahon, Gregory; Steadman, Sharon (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia:(10,000–323 BCE). Oxford University Press Inc. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.001.0001. hdl:11693/51311. ISBN 9780195376142.

Further reading

- Akat, Uücel, Neşe Özgünel, and Aynur Durukan. 1991. Anatolia: A World Heritage. Ankara: Kültür Bakanliǧi.

- Brewster, Harry. 1993. Classical Anatolia: The Glory of Hellenism. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Donbaz, Veysel, and Şemsi Güner. 1995. The Royal Roads of Anatolia. Istanbul: Dünya.

- Dusinberre, Elspeth R. M. 2013. Empire, Authority, and Autonomy In Achaemenid Anatolia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gates, Charles, Jacques Morin, and Thomas Zimmermann. 2009. Sacred Landscapes In Anatolia and Neighboring Regions. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Mikasa, Takahito, ed. 1999. Essays On Ancient Anatolia. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Takaoğlu, Turan. 2004. Ethnoarchaeological Investigations In Rural Anatolia. İstanbul: Ege Yayınları.

- Taracha, Piotr. 2009. Religions of Second Millennium Anatolia. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Taymaz, Tuncay, Y. Yilmaz, and Yildirim Dilek. 2007. The Geodynamics of the Aegean and Anatolia. London: Geological Society.

External links

Media related to Anatolia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Anatolia at Wikimedia Commons