Syrian opposition

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Syrian Opposition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

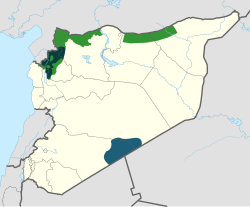

Areas under control of various opposition groups as of February 2020 Interim Government (National Army) Salvation Government (Tahrir al-Sham) al-Tanf (Army of Free Syria) | |||||||

| Capital | Damascus (claimed) Azaz (de facto by SIG)[1][2] Al-Tanf Base (used by Syrian Free Army) | ||||||

| Largest city | Damascus (claimed) | ||||||

| Official languages | Arabic | ||||||

| Demonym(s) | Syrian | ||||||

| Government | Unitary provisional government | ||||||

• President of the Syrian National Coalition | Salem al-Meslet | ||||||

• Prime Minister of interim government | Abdurrahman Mustafa | ||||||

| Legislature | General Assembly / General Shura Council | ||||||

| Establishment | |||||||

• Formation | 15 March 2011 | ||||||

| Currency | Turkish lira,[3][4] Euro, United States dollar and Syrian pound (SYP) | ||||||

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EET) | ||||||

| Drives on | right | ||||||

| Calling code | +963 | ||||||

| ISO 3166 code | SY | ||||||

| Internet TLD | .sy سوريا. | ||||||

| |||||||

|

|---|

The Syrian opposition (Arabic: المعارضة السورية al-Muʻaraḍatu s-Sūrīyah, [almʊˈʕaːɾadˤɑtu s.suːˈɾɪj.ja]) is the political structure represented by the Syrian National Coalition and associated Syrian anti-Assad groups with certain territorial control as an alternative Syrian government.

The Syrian opposition has evolved since the beginning of the Syrian conflict from groups calling for the overthrow of the Assad government in Syria and who have opposed its Ba'athist government.[5] Prior to the Syrian Civil War, the term "opposition" (Arabic: المعارضة) had been used to refer to traditional political actors, for example the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change; that is, groups and individuals who have had a history of dissidence against the Syrian state.[6]

The first opposition structures to form in the Syrian uprising were local protest-organizing committees. These formed in April 2011, as protesters graduated from spontaneous protests to protests organized by meetings beforehand.[7]

The Syrian uprising phase, from March 2011 until the start of August 2011, was characterized by a consensus for nonviolent struggle among the uprising's participants.[8] Thus the conflict could not have been yet characterized as a "civil war", until army units defected in response to government reprisals against the protest movement.[9][10] This occurred 2012, allowing the conflict to meet the definition of "civil war."[11]

Opposition groups in Syria took a new turn in late 2011, during the Syrian Civil War, as they united to form the Syrian National Council (SNC),[12] which has received significant international support and recognition as a partner for dialogue. The Syrian National Council was recognized or supported in some capacity by at least 17 member states of the United Nations, with three of those (France, United Kingdom and the United States) being permanent members of the Security Council.[13][14][15][16][17][18]

A broader opposition umbrella group, the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, was formed in November 2012 and has gained recognition as the "legitimate representative of the Syrian people" by the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (CCASG) and as a "representative of aspirations of Syrian people" by the Arab League.[19] The Syrian National Coalition was subsequently considered to take the seat of Syria in the Arab League, with the representative of Bashar Al-Assad's government suspended that year. The Syrian National Council, initially a part of the Syrian National Coalition, withdrew on 20 January 2014 in protest at the decision of the coalition to attend the Geneva talks.[20] Despite tensions, the Syrian National Council retained a degree of ties with the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces. Syrian opposition groups held reconciliation talks in Astana, Kazakhstan in October 2015.[21] In late 2015, the Syrian Interim Government relocated its headquarters to the city of Azaz in North Syria and began to execute some authority in the area. In 2017, the opposition government in the Idlib Governorate was challenged by the rival Syrian Salvation Government, backed by the Islamist faction Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

A July 2015 ORB International poll of 1,365 adults across all of Syria's 14 governorates found that about 26 percent of the population supported the Syrian opposition (41 percent in the areas it controlled), compared to 47 percent who supported the Syrian Arab Republic's government (73 percent in the areas it controlled), 35 percent who supported the Al-Nusra Front (58 percent in the areas it controlled), and 22 percent who supported the Islamic State (71 percent in the areas it controlled).[22] A March 2018 ORB International Poll with a similar method and sample size found that support had changed to 40% Syrian government, 40% Syrian opposition (in general), 15% Syrian Democratic Forces, 10% al-Nusra Front, and 4% Islamic State (crossover may exist between supporters of factions).[23]

Background

Syria has been an independent republic since 1946 after the expulsion of the French forces. For decades, the country was partially stable with a series of coups until the Ba'ath Party seized power in Syria in 1963 after a coup d'état. The head of state since 1971 has been a member of the Assad dynasty, beginning with Hafez al-Assad (1971–2000). Syria was under emergency law from the time of the 1963 Syrian coup d'état until 21 April 2011, when it was rescinded by Bashar al-Assad, Hafez's eldest surviving son and the current President of Syria.[24]

The rule of Assad dynasty was marked by heavy repression of secular opposition factions such as the Arab nationalist Nasserists and liberal democrats. The biggest organised resistance to the Ba’athist rule has been the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood; which successfully capitalised on the widespread Sunni resentment against the Alawite hegemony. Syrian Ikhwan was inspired by the Syrian Salafiyya movement led by Muhammad Rashid Rida, an influential Sunni Islamic theologian who is respected as their Imam. In line with the teachings of Rashid Rida, the Muslim Brotherhood advocates the replacement of the Ba’ath party rule with an Islamic state led by an Emir elected by qualified Muslim delegates known as Ahl al-Hall wa-al-‘Aqd. The Islamic government should implement laws based on sharia (Islamic law) with the assistance of ulema who are to be consulted on solving contemporary challenges. The power of the ruler is also to be checked by the provisions laid out in an Islamic constitution through shura (consultation) with the Ahl al-Hall wa-al-‘Aqd. Assad regime introduced Law No. 49 in 1980 which banned the movement and instituted death penalty of anyone accused of membership in the Brotherhood. In response, the Syrian Islamic Front was established the same year to topple the Assadist military dictatorship through an armed revolution. The Front got widespread support from the traditional Sunni ulema and the conservative population; enabling the Syrian Ikhwan al-Muslimeen to rise as the most powerful opposition force by the 1980s.[25][26]

As the revolutionary wave commonly referred to as the Arab Spring began to take shape in early 2011, Syrian protesters began consolidating opposition councils.

History

The Istanbul Meeting for Syria, the first convention of the Syrian opposition, took place on 26 April 2011, during the Syrian civil uprising. There followed the Antalya Conference for Change in Syria or Antalya Opposition Conference, a three-day conference of representatives of the Syrian opposition held from 31 May until 3 June 2011 in Antalya, Turkey.

Organized by Ammar al-Qurabi's National Organization for Human Rights in Syria and financed by the wealthy Damascene Sanqar family, it led to a final statement refusing compromise or reform solutions, and to the election of a 31-member leadership.

After the Antalya conference, a follow-up meeting took place two days later in Brussels, then another gathering in Paris that was addressed by Bernard Henri Levy.[27] It took a number of further meetings in Istanbul and Doha before yet another meeting on 23 August 2011 in Istanbul set up a permanent transitional council in form of the Syrian National Council.[28]

Political groups

The Syrian opposition does not have a definitive political structure. In December 2015, members of the Syrian opposition convened in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: 34 groups attended the convention, which aimed to produce a unified delegation for negotiations with the Syrian government.[29] Notable groups present included:

- the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, which supported the implementation of the 2012 Geneva Communique, which calls for the establishment of a transitional governing body in Syria

- the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change, which called for negotiations on a peaceful transition

- armed groups:

The December 2015 convention notably did not include:[29]

- the Kurdish PYD party and its affiliates

- Salafist armed groups such as Al-Nusra Front.

National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces

The National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces is a coalition of opposition groups and individuals, mostly exilic, who support the Syrian revolutionary side and oppose the Assad government ruling Syria. It formed on 11 November 2012 at a conference of opposition groups and individuals held in Doha, Qatar. It has relations with other opposition organizations such as the Syrian National Council, the previous iteration of an exilic political body attempting to represent the grassroots movement; the union of the two was planned,[by whom?] but has failed to realize. Moderate Islamic preacher Moaz al-Khatib, who had protested on the Syrian street in the early nonviolent phase of the uprising, served a term as the president of the coalition, but soon resigned his post, frustrated with the gap between the body and the grassroots of the uprising inside Syria.[30] Riad Seif and Suheir Atassi, both of whom had also protested on the street in Syria early in the uprising, were elected as vice presidents. Mustafa Sabbagh is the coalition's secretary-general.[31]

Notable members of the Coalition include:

- the Assyrian Democratic Organization: a party representing Assyrians in Syria and long repressed by the Assad government, it has participated in opposition structures since the beginning of the conflict. Abdul-Ahad Astepho is a member of the SNC.[32][33]

Syrian National Council

The Syrian National Council (al-Majlis al-Waṭanī as-Sūri) sometimes known as SNC,[34][35] the Syrian National Transitional Council[36] or the National Council of Syria, is a Syrian opposition coalition, based in Istanbul (Turkey), formed in August 2011 during the Syrian civil uprising against the government of Bashar al-Assad.[37][38]

Initially, the council denied seeking to play the role of a government in exile,[39] but this changed a few months later when violence in Syria intensified.[40][41][42] The Syrian National Council seeks the end of Bashar al-Assad's rule and the establishment of a modern, civil, democratic state. The SNC National Charter lists human rights, judicial independence, press freedom, democracy and political pluralism as its guiding principles.[43]

In November 2012 the Council agreed to unite with several other opposition groups to form the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, with the SNC having 22 out of 60 seats.[44][45][46] The Council withdrew from the Coalition on 20 January 2014 in protest at the decision of the Coalition to attend talks in Geneva.[47]

Notable members of the Council include:

- the Syrian Democratic People's Party, a socialist party which played a "key role" in forming the SNC.[48] The Party's leader George Sabra (a secularist born into a Christian family) is the official spokesman of the SNC, and also ran for chairman.[49]

- the Supreme Council of the Syrian Revolution, a Syrian opposition group supporting the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad's government. It grants local opposition groups representation in its national organization.

- the Syrian Democratic Turkmen Movement: An opposition party, constituted in Istanbul on 21 March 2012, of Syrian Turkmens. Ziyad Hasan leads the Syrian Democratic Turkmen Movement.

National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change

The National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change (NCC), or National Coordination Body for Democratic Change[50] (NCB), is a Syrian bloc chaired by Hassan Abdel Azim and consisting of 13 left-wing political parties and "independent political and youth activists".[51] Reuters has defined the committee as the internal opposition's main umbrella group.[52] The NCC initially had several Kurdish political parties as members, but all except for the Democratic Union Party left in October 2011 to join the Kurdish National Council.[53] Some opposition activists[who?] have accused the NCC of being a "front organization" for Bashar al-Assad's government and have denounced some of its members as ex-government insiders.[54]

The NCC generally has poor relationships with other Syrian political opposition groups. The Syrian Revolution General Commission, the Local Coordination Committees of Syria, and the Supreme Council of the Syrian Revolution oppose the NCC calls to dialogue with the Syrian government.[55] In September 2012 the Syrian National Council (SNC) reaffirmed that despite broadening its membership, it would not join with "currents close to [the] NCC".[56] Despite the NCC recognizing the Free Syrian Army (FSA) on 23 September 2012,[57] the FSA has dismissed the NCC as an extension of the government, stating that "this opposition is just the other face of the same coin".[52]

Notable former members of the Committee have included:

- the Syriac Union Party, a party representing the interests of Syriac Christians and affiliated with the Syriac Union Party in Lebanon (itself part of the anti-Assad March 14 Alliance). It has taken part in numerous opposition demonstrations, including storming the Syrian embassy in Stockholm in August 2012.[58] It later left the NCC and joined the Syrian Democratic Council in late 2015.[59] [failed verification]

- the Democratic Union Party, the main Kurdish party in Syria and the dominant party in the de facto Democratic Federation of Northern Syria. It later left the NCC and joined the Syrian Democratic Council in late 2015.[59] [failed verification]

Syrian Democratic Council

The Syrian Democratic Council was established on 10 December 2015 in al-Malikiyah. It was co-founded by prominent human rights activist Haytham Manna and was intended as the political wing of the Syrian Democratic Forces. The council includes more than a dozen blocs and coalitions that support federalism in Syria, including the Movement for a Democratic Society, the Kurdish National Alliance in Syria, the Law–Citizenship–Rights Movement, and since September 2016 the Syria's Tomorrow Movement. The last group is led by former National Coalition president and Syrian National Council Ahmad Jarba. In August 2016 the SDC opened a public office in al-Hasakah.[60]

The Syrian Democratic Council is considered an "alternative opposition" bloc.[61] Its leaders included former NCC members such as Riad Darar, a "key figure" in the Syrian opposition, and Haytham Manna, who resigned from the SDC in March 2016 in protest of its announcement of the Northern Syria Federation.[62] The SDC was rejected by some other opposition groups due to its system of federalism.[63]

The Syrian Democratic Council was invited to participate in the international Geneva III peace talks on Syria in March 2016. However, it rejected the invitations because no representatives of the Movement for a Democratic Society, led by the Democratic Union Party, were invited.[citation needed]

Other groups affiliated with Syrian opposition

- Muslim Brotherhood: Islamist party founded in 1930. The brotherhood was behind the Islamic uprising in Syria between 1976 until 1982. The party is banned in Syria and membership became a capital offence in 1980. The Muslim Brotherhood has issued statements of support for the Syrian uprising.[64][65] Other sources have described the group as having "risen from the ashes",[66] "resurrected itself"[67] to be a dominant force in the uprising.[68] The Muslim Brotherhood has constantly lost influence with militants on the ground, who have defected from the Brotherhood affiliated Shields of the Revolution Council to the Islamic Front.[69]

- Coalition of Secular and Democratic Syrians: nucleus of a Syrian secular and democratic opposition that appeared during the Syrian civil war. It came about through the union of a dozen Muslim and Christian, Arab and Kurd parties, who called the minorities of Syria to support the fight against the government of Bashar al-Assad.[70][71] The Coalition has also called for military intervention in Syria, under the form of a no-fly zone similar to that of Kosovo, with a safe zone and cities.[72][73] The president of the coalition, who is also a member of the SNC, is Randa Kassis.[74][75][76][77]

- Syrian Turkmen Assembly: A recently formed assembly of Syrian Turkmens which constitutes a coalition of Turkmen parties and groups in Syria. It is against the partition of Syria after the collapse of Baath government. The common decision of Syrian Turkmen Assembly is: "Regardless of any ethnic or religious identity, a future in which everybody can be able to live commonly under the identity of Syrian is targeted in the future of Syria."[78]

- Syrian Turkmen National Bloc: An opposition party of Syrian Turkmens, which was founded in February 2012. The chairman of the political party is Yusuf Molla.

- Local Coordination Committees of Syria: Network of local protest groups that organise and report on protests as part of the Syrian civil war, founded in 2011.[79][80] As of August 2011[update], the network supported civil disobedience and opposed local armed resistance and international military intervention as methods of opposing the Syrian government.[81] Key people are activists Razan Zaitouneh and Suhair al-Atassi.[82]

- Syrian National Democratic Council: formed in Paris on 13 November 2011 during the Syrian civil war by Rifaat al-Assad, uncle of Bashar al-Assad. Rifaat al-Assad has expressed the wish to replace Bashar al-Assad with the authoritarian state apparatus intact, and to guarantee the safety of government members, while also making vague allusions to a "transition".[83] Rifaat has his own political organisation, the United National Democratic Rally.[84]

- Syrian Revolution General Commission: Syrian coalition of 40 Syrian opposition groups to unite their efforts during the Syrian civil war that was announced[by whom?] on 19 August 2011 in Istanbul.[85]

Other opposition groups

- The Democratic National Assembly: Political gathering of political parties and organizations, citizens independent of parties, and public figures.[86] It was established in 1979 and consists of five parties: the Democratic Arab Socialists Union, the Syrian Democratic People's Party, the Arab Revolutionary Workers' Party, the Arab Socialists Movement, and the Arab Socialist Democratic Ba'ath Party. In 2006, the Communist Labour Party joined this coalition, and it was one of the participants in the "Damascus Spring".

- The National Salvation Front in Syria: It was founded in 2005 by Abdul Halim Khaddam, who is the former vice-president, along with a number of opposition figures abroad.[87] He was previously one of the symbols of the regime during the days of former President Hafez al-Assad.[88]

- Ehrar - The Syrian Liberal Party: This party was founded in February 2000.[89] It is a social liberal political party. It is headed by Mrs. Yasmine Merhi and her deputy, Mr. Khaled al-Bitar. It is the first opposition political party headed by a Syrian woman.[90]

Parliamentary opposition

Several political parties and organizations existed inside Syria, and they reached the dome of the People's Assembly. Among these parties are included:

- The Popular Front for Change and Liberation: The front was founded in Augst 2011 in Damascus.[91] It established in its national charter the launch of public freedoms, the start of a national dialogue, and work on drafting a new constitution. The Front participated in the 2012 elections and achieved the second place, after the list of the National Progressive Front. They achieved 5 seats.[92][93] Among the different parties united in the Front are:

- Syrian Social Nationalist Party: Founded in 1932 in Lebanon, the party believes that the Syrian nation is one community together with the Fertile Crescent region. This also includes Kuwait, Cyprus, the Sinai Peninsula and southeastern Turkey.[94] This ideology was more attractive to minorities in that region, at the expense of Arab nationalism and Islamic ideologies.[95] Therefore, ethnic and religious minorities constituted the largest proportion of party members.

- Popular Will Party: Founded on August 21, 2012 by Qadri Jamil. It is a communist-associated Syrian political party that affirms the interests of the working class and other hard-working Syrians. They also fight for the recognition of them as a representative of these interests.[96]

Governance

Syrian Interim Government

At a conference held in Istanbul on 19 March 2013 members of the National Coalition elected Ghassan Hitto as prime minister of an interim government for Syria, the Syrian Interim Government (SIG). Hitto has announced that a technical government will be formed which will be led by between 10 and 12 ministers, with the Free Syrian Army choosing the Minister of Defense.[97] The SIG is based in Turkey. It has been the primary civilian authority throughout most of opposition-held Syria. Its system of administrative local councils operate services such as schools and hospitals in these areas, as well as the Free Aleppo University.[98][99] By late 2017, it presided over 12 provincial councils and over 400 elected local councils. It also operates a major border crossing between Syria and Turkey, which generates an estimated $1 million revenue each month.[98] It is internationally recognized by the European Union and the United States, among others. It maintains diplomatic ties with some non-FSA rebel groups, such as Ahrar al-Sham, but is in conflict with the more extreme Tahrir al-Sham, which is one of the largest armed groups in Idlib Governorate.[98]

Syrian Salvation Government

The Syrian Salvation Government is an alternative government of the Syrian opposition seated within Idlib Governorate, which was formed by the General Syrian Conference in September 2017.[100] The domestic group has appointed Mohammed al-Sheikh as head of the Government with 11 more ministers for Interior, Justice, Endowment, Higher Education, Education, Health, Agriculture, Economy, Social Affairs and Displaced, Housing and Reconstruction and Local Administration and Services. Al-Sheikh, in a press conference held at the Bab al-Hawa Border Crossing has also announced the formation of four commissions: Inspection Authority, Prisoners and missing Affairs, Planning and Statistics Authority, and the Union of Trade Unions.[101] The founder of the Free Syrian Army, Col. Riad al-Asaad, was appointed as deputy prime minister for military affairs.[citation needed] The SSG is associated with Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and not recognised by the rest of the opposition, which is in conflict with HTS.[101]

There is a sharp ideological divide between the two competing opposition civil authorities: The SIG espouses secular, moderate values and regularly participates in international peace talks; the SSG enforces a strict interpretation of Islamic law and stringently rejects talks with the Syrian regime.[98]

Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria is an area that extends in northeastern Syria and includes parts of the governorates Al-Hasakah, Al-Raqqa, Aleppo and Deir ez-Zor.[102] The capital of the area is Ain Issa, a town belonging to the Al-Raqqa governorate.[103] The Administration is headed by Siham Qaryo and Farid Atti with a joint head.[104] In January 2014, a number of parties, social actors, and civil institutions announced the formation of the Autonomous Administration to fill the power vacuum that existed at that time in the Syrian Kurdish regions.[105] Although its authority has not been recognized or authorized by any formal agreement involving the sovereign Syrian state or any international power, its presence in the region and its ability to wield power was unchallenged.[102]

Territorial control

(For a more detailed, interactive map, see Template:Syrian Civil War detailed map.)

Various Syrian opposition groups have at least some presence in seven Syrian governorates, though none is fully under the control of the entity. Governorates with partial opposition control include:

Governorates under partial control of opposition groups aligned with the Syrian Interim Government:

- Latakia Governorate - Control on Eastern areas next to Idlib.

- Idlib Governorate -

- Hama Governorate - Limited Control on Northern areas next to Idlib.

- Aleppo Governorate

- Hasakah Governorate

- Raqqa Governorate

Governorates under partial control of opposition groups aligned with the Syrian Democratic Council:

Turkish-Controlled territories and territories controlled by the Syrian Interim Government

In April 2015, after the Second Battle of Idlib, the interim seat of the Syrian Interim Government was proposed to be Idlib, in the Idlib Governorate. However, this move was rejected by the al-Nusra Front and Ahrar al-Sham-led Army of Conquest, which between them controlled Idlib.[106] According to the Syrian National Coalition, in 2017 there were 404 opposition-aligned local councils operating in villages, towns, and cities controlled by rebel forces.[107] In 2016, the Syrian Interim Government became established within the Turkish Controlled areas.

Territories governed by the Salvation Government

The Salvation Government extends authority mostly in the Idlib Governorate.

Al-Tanf Garrison

The Syrian Free Army maintains the al-Tanf Garrison. Due to this garrison being inside an American De-Escalation zone, the garrison is not often attacked, nor does it often attempt to expand its territory.

Recognition and foreign relations

The foreign relations of the Syrian opposition refers to the external relations of the self-proclaimed oppositional Syrian Arab Republic, which sees itself as the genuine Syria. The region of control of Syrian opposition affiliated groups is not well defined. The Turkish government recognizes Syrian opposition as the genuine Syrian Arab Republic and hosts several of its institutions on its territory. The seat of Syria in the Arab League is reserved for the Syrian opposition since 2014, but not populated.[citation needed]

The opposition as a whole is characterised as "terrorist" by Iran,[108] Russia[109] and Syria.[110]

Military forces

Initially, the Free Syrian Army was perceived as the ultimate military force of the Syrian Opposition, but with the collapse of many FSA factions and emergence of powerful Islamist groups, it became clear to the opposition that only a cooperation of secular military forces and moderate Islamists could form a sufficient coalition to battle both the Syrian Government forces and radical Jihadists such as ISIL and in some cases al-Nusra Front.

In 2014, the military forces associated with the Syrian Opposition were defined by the Syrian Revolutionary Command Council, which in turn was mainly relying on the Free Syrian Army (with links to Syrian National Coalition) and the Islamic Front (Syria). Members of the Syrian Revolutionary Command Council:

- Free Syrian Army: Paramilitary that has been active during the Syrian civil war.[111][112] Composed mainly of defected Syrian Armed Forces personnel,[113][114] its formation was announced on 29 July 2011 in a video released on the Internet by a uniformed group of deserters from the Syrian military who called upon members of the Syrian army to defect and join them.[115] The leader of the group, who identified himself as Colonel Riad al-Asaad, announced that the Free Syrian Army would work with demonstrators to bring down the system, and declared that all security forces attacking civilians are justified targets.[116][117] It has also been reported that many former Syrian Consulates are trying to band together a Free Syrian Navy from fishermen and defectors to secure the coast.[118]

- Syrian Turkmen Brigades: An armed opposition structure of Syrian Turkmens fighting against Syrian Armed Forces. It is also the military wing of Syrian Turkmen Assembly. It is led by Colonel Muhammad Awad and Ali Basher.

- Syrian Free Army - Free Syrian Army unit trained by, and politically very close too, the United States. It remains the last unit in the Al-Tanf area, and functions as the de facto opposition government there.

- Islamic Front: An Islamist rebel group formed in November 2013 and led by Ahrar al-Sham.[119] It was always a loose alliance and was defunct by 2015.[120]

- Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF): An alliance that brings together many multi-ethnic and multi-religious militias, and is controlled by the forces affiliated with the Kurdish Democratic Union Party represented by the People's Protection Forces and the Women's Protection Forces.[121] These forces are characterized by a less hostile attitude towards the Syrian regime than other opposition brigades. They function de facto as the armed forces of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and are also recognized as such by the Administration.[122]

Other rebel fighting forces:

- Syrian Islamic Liberation Front: The major rebel fighting coalition independent of the FSA in the period 2012–2013, including the moderate Islamist groups Suqour al-Sham, Al-Tawhid Brigade and Jaysh al-Islam, deploying up to half the opposition's fighting force. It main members joined the Islamic Front in 2013.

- Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army: A coalition of mainly Arab and Turkmen opposition fighters in Northern Syria, armed and backed by Turkey since May 2017, partially reorganized as the Syrian National Army in December 2017.

- National Front for Liberation: A coalition of FSA groups in Idlib and NW Syria formed in early 2018 and backed by Turkey.

- Syrian Liberation Front: An Islamist rebel group formed in early 2018 and including Ahrar al-Sham and the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement, the largest rebel fighting groups in NW Syria.

List of opposition figures

- Abdulrazak Eid, Syrian writer and thinker, participated in finding the Committees for the Civil Society in Syria, wrote the first draft of the Statement of 1000, and participated in drafting the Damascus Declaration, president of the national council of Damascus Declaration abroad.

- Ammar Abdulhamid, leading Human-Rights Advocate, Founder of Tharwa Foundation, first Syrian to testify in front of American Congress 2006/2008, briefed Presidents of the United States, and called for Syria Revolution in 2006.[123]

- Aref Dalilah, prominent economist, professor, former member of Syrian Parliament and a member of the Damascus Declaration

- Burhan Ghalioun, former head of the SNC

- Riad al-Asaad, a leader in the Free Syrian Army

- Riad Seif, former head of the Forum for National Dialogue

- Riyad al-Turk, ex-communist politician and liberal democrat

- Haitham al-Maleh, leading human rights activist and former judge

- Anwar al-Bunni, human rights lawyer, democracy activist and political prisoner

- Maher Arar, Syrian-Canadian human rights activist

- Marwan Habash, politician and writer and pre-Assad Minister of Industry

- Michel Kilo, Christian[124] writer and human rights activist, who has been called "one of Syria's leading opposition thinkers"[125]

- Kamal al-Labwani, doctor and artist, considered one of the most prominent members of the Syrian opposition movement

- Tal al-Mallohi, blogger from Homs and world's youngest prisoner of conscience

- Yassin al-Haj Saleh, writer and political dissident

- Fares Tammo, son of assassinated Kurdish politician Mashaal Tammo

- Bassma Kodmani, an academic and former spokesperson of the SNC

- Radwan Ziadeh, co-spokesperson for the SNC

- Randa Kassis, president of the Coalition of Secular and Democratic Syrians

- Fadwa Suleiman, leader of protests in Homs

- Razan Ghazzawi, prominent blogger

- Samar Yazbek, Syrian author and journalist. She was awarded the 2012 PEN Pinter International Writer of Courage Award for her book, A Woman in the Crossfire: Diaries of the Syrian Revolution. She fled Syria in 2011 but continues to be an outspoken critic of the al-Assad government from abroad, from Europe and the US.

- Razan Zaitouneh, leader in the Local Coordination Committees of Syria and the 2011 Sakharov Prize winner

- Muhammad al-Yaqoubi Sunni Muslim scholar and preacher, currently residing in exile in Morocco

- Hussam Awak, ex-Syrian Air Force and Air Force Intelligence Directorate officer who later joined the Syrian Democratic Forces

- Abdulhakim Bachar: one of the most prominent Kurdish figures participating in the National Coalition, where he served as Vice President of the National Coalition for several sessions.[126] He is also a founding member of the Damascus Declaration, as well as a founding member of the Kurdish National Council and its first elected president.[127]

See also

References

- ^ Charles Lister (31 October 2017). "Turkey's Idlib Incursion and the HTS Question: Understanding the Long Game in Syria". War on the Rocks. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ al-Khateb, Khaled (19 September 2018). "Idlib still wary of attack despite Turkish-Russian agreement". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Ashawi, Khalil (28 August 2018). "Falling lira hits Syrian enclave backed by Turkey". Reuters.

- ^ Ghuraibi, Yousef (1 July 2020). "Residents of northwestern Syria replace Syrian pound with Turkish lira". Enab Baladi. Idlib. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Bashar al-Assad: Facing down rebellion". BBC News. 3 September 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Sayigh, Yezid. "The Syrian Opposition's Leadership Problem". Carnegie Middle East Center. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Ghattas, Kim (22 April 2011). "Syria's spontaneously organised protests". BBC News. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Kouddous, Sharif Abdel (23 August 2012). "How the Syrian Revolution Became Militarized". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Asad's Armed Opposition: The Free Syrian Army". www.washingtoninstitute.org. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "We Live as in War". Human Rights Watch. 11 November 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Syrian Civil War | Facts & Timeline". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "The main components of the Syrian opposition". London: BBC Arabic. 24 February 2012. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ thejournal.ie (27 February 2012). "EU ministers recognise Syrian National Council as legitimate representatives". Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Andrew Rettman (24 October 2011). "France recognises Syrian council, proposes military intervention". EUObserwer. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ^ "Clinton to Syrian opposition: Ousting al-Assad is only first step in transition". CNN. 6 December 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "UK Recognizes Syrian Opposition". International Business Times. 24 February 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Libya NTC says recognises Syrian National Council". Khaleej Times. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ "Libya to arm syrian rebels". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney Morning Herald. 27 November 2011. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ "Syria's newly-formed opposition coalition draws mixed reaction". Xinhua. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Main bloc quits Syrian National Coalition over Geneva". The Times of Israel. 21 January 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "Syrian opposition sign joint document in Kazakhstan's Astana". Tengri News. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "ORB/IIACSS POLL IN IRAQ AND SYRIA GIVES RARE INSIGHT INTO PUBLIC OPINION." ORB International July 2015. PDF link (see tables 1 and 8).

- ^ NEW ORB POLL: 52% SYRIANS BELIEVE ASSAD REGIME WILL WIN THE WAR Archived 9 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine. ORB International. 15 March 2015.

- ^ Syria's state of emergency Archived 24 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Al Jazeera, 17 April 2011.

- ^ Rpberts, David (2015). The Ba'th and the creation of Modern Syria. 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN: Routledge. pp. 9, 19–20, 115–116, 120. ISBN 978-0-415-83882-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria". 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019.

- ^ Samir Aita (2015). "Syria". In I. William Zartman (ed.). Arab Spring: Negotiating in the Shadow of the Intifadat. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. p. 302 f. ISBN 978-0-8203-4824-7.

- ^ Ufuk Ulutaş (2011). "The Syrian Opposition in the Making: Capabilities and Limits". Insight Turkey. 13 (3): 92.

- ^ a b "Syrian opposition seeks unified front at Riyadh conference". bbc.com. 8 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Kahf, Mohja. "Lack of U.S. Peace Movement Solidarity with Syrian Uprising and the "No Good Guys Excuse" | Fellowship of Reconciliation". Forusa.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Rebhy, Abdullah (11 November 2012). "Syrian opposition groups reach unity deal". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Carnegie Middle East Center: The Assyrian Democratic Organization". Carnegie Middle East Center. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "Assyrians and the Syrian Uprising". Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ Skelton, Charlie (12 July 2012). "The Syrian opposition: who's doing the talking?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ the CNN (23 August 2011). "Syrian activists form a 'national council'". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Arab League under pressure, resists freezing Syria membership". Al Ahram. 12 November 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Yezdani, Ipek (23 August 2011). "Syrian dissidents form national council". World Wires. Miami Herald Media. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Yezdani, İpek (23 August 2011). "Syrian dissidents form national council". The Edmond Sun. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "Syrian council wants recognition as voice of opposition". Reuters. 10 October 2011. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "Syrian National Council, Syria's rebel government, opens offices in Turkey". Global Post. 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 20 December 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "Syrian National Council Holds First Congress in Tunis". Tunisia Live. 16 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "Why Syria's Kurds Will Determine the Fate of the Revolution". IKJNEWS. 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "Q&A: Syrian opposition alliance". BBC News. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ AP 4:15 p.m. EST 11 November 2012 (11 November 2012). "Syrian opposition groups reach unity deal". Usatoday.com. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Syrian opposition groups sign coalition deal – Middle East". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Gamal, Rania El (11 November 2012). "Syrian opposition agrees deal, chooses preacher as leader". Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ "Main bloc quits Syrian National Coalition over Geneva". The Times of Israel. 21 January 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "Carnegie Middle East Center: The Syrian Democratic People's Party". Carnegie Middle East Center. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "Carnegie Middle East Center: George Sabra". Carnegie Middle East Center. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ Haddad, Bassam (30 June 2012). "The Current Impasse in Syria: Interview with Haytham Manna". Jadaliyya. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "Guide to the Syrian opposition". BBC News. 25 July 2012. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Damascus meeting calls for peaceful change in Syria". Reuters UK. 23 September 2012. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ "National Coordination Body for Democratic Change". Carnegie Middle East Center. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "Syria opposition groups fail to reach accord". Financial Times. 4 January 2012. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "Meet Syria's Opposition". Foreign Policy. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Syria's opposition SNC to expand, reform". AFP. 2 September 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ "Syria Salvation Conference: Our Main Principles". NCC/NCB official statement. 23 September 2012. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "Parked at Loopia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Kurdish-Arab coalition fighting Islamic State in Syria creates political wing". GlobalPost (AFP). 10 December 2015. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ "Inauguration of the 1st MSD office". Hawar News Agency. 1 August 2016. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ "Haytham Manna Elected Joint Chairman of Syrian Democratic Council". Syrian Observer. 14 December 2015. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Syrian opposition co-leader speaks about Kurdish-Baathist party relations". Rudaw. 28 April 2017. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Yousif Ismael (13 February 2017). "Interview with Ilham Ahmad Co-chair of Syria Democratic Council (MSD)". Washington Kurdish Institute. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Muslim Brotherhood Behind Syrian Uprising". The Stafford Voice. Beirut. AP. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ Ghosh, Palash (11 April 2011). "Outlawed Muslim Brotherhood supports Syrian revolt". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ Syria's Muslim Brotherhood rise from the ashes Archived 15 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine|By Khaled Yacoub Oweis|6 May 2012

- ^ Syria's Muslim Brotherhood is gaining influence over anti-Assad revolt Archived 9 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine By Liz Sly, Washington Post 12 May 2012

- ^ "Free Article for Non-Subscriber". Stratfor. 27 February 2012. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Masi, Alessandria (9 March 2015). "Aleppo Battle: Al Qaeda's Jabhat Al-Nusra is Friend To Syrian Rebel Groups". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

In 2013, the Syrian opposition included a large number of Islamist brigades that were neither moderate nor jihadist but were aligned with the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood, under an umbrella organization called the Commission of the Shields of the Revolution. Two years later, the brigades have begun to slowly disperse.

- ^ John Irish (16 September 2011) "France hails Syria council, develops contacts" Archived 15 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters.

- ^ "Les partis d'opposition laïcs syriens unissent leurs forces à Paris" Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Agence France-Presse, 18 September 2011.

- ^ "UN: Syria death toll tops 2,700" Archived 11 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Al Jazeera, 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Répression en Syrie: Al Assad seul contre tous ?" Archived 15 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, France 24, 11 January 2012.

- ^ "Entretien avec Randa Kassis, opposante et intellectuelle syrienne porte-parole de la Coalition des Forces Laïques et membre du Conseil National Syrien" Archived 26 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, France Soir, 11 November 2011.

- ^ Alexandre Del Valle (2 June 2011) "Syrie: Pourquoi Assad reste au pouvoir" Archived 3 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, France Soir.

- ^ Julien Peyron (11 January 2012) Discours de Bachar al-Assad: "Comme d’habitude, il ressort le complot de l’étranger" Archived 9 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, France 24.

- ^ "Randa Kassis est membre du comité directeur de la Coalition des forces laïques et démocratiques syriennes." Archived 12 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Radio France International, 18 September 2011.

- ^ Syrian Turkmens ask equality in opposition, Hürriyet Daily News Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 17 December 2012, Istanbul.

- ^ "Syrian woman activist wins human rights award". Amnesty International. 7 October 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ Basil, Yousuf; Richard Roth; Mick Krever; Salma Abdelaziz; Mohamed Fadel Fahmy (5 February 2012). "Opposition group calls for strike as Syrian violence grows". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ "Syrian Local Coordinating Committees on Taking Up Arms and Foreign Intervention". Jadaliyya. Arab Studies Institute. 31 August 2011. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ Shadid, Anthony; Hwaida Saad (30 June 2011). "Coalition of Factions From the Streets Fuels a New Opposition in Syria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ "Exiled Assad's uncle wants to lead Syria transition". Al Arabiya. 14 November 2011. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "United National Democratic Rally التجمع القومي الديموقراطي الموحد". Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "Syrian coalition against Assad formed". Dawn. Agence France-Presse. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ "التجمع الوطني الديمقراطي في سورية". www.mafhoum.com. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Conduit, Dara (29 July 2019). The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108758321. ISBN 978-1-108-75832-1. S2CID 201528149.

- ^ "An administrative decision from the leadership of the National Salvation Front in Syria". 20 August 2011. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ ZMRDSTUDIO. "Ahrar - Liberal Party of Syria - english". Ahrar - Liberal Party of Syria. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "حزب أحرار - الحزب الليبرالي السوري - الإعلان عن اطلاق حزب "أحرار" السوري بقيادة نسائية". 25 November 2020. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Elizabeth O'Bagy (7 June 2012). "Syria's political struggle: Spring 2012" (PDF). Institute for the Study of War.

- ^ "Russia Bids to Unite Syria's Fractured Opposition | Russia | RIA Novosti". 2 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Memorandum of Understanding between the National Coordination Body for Democratic Change in Syria – NCB and the Change and Liberation Front | هيئة التنسيق الوطنية لقوى التغيير الديمقراطي". 25 November 2015. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "غاية الحزب السوري القومي الإجتماعي". الحزب السوري القومي الاجتماعي (in Arabic). Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Yonker, Carl C. (15 April 2021). The Rise and Fall of Greater Syria. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110729092. ISBN 978-3-11-072909-2. S2CID 234838604.

- ^ قاسيون (13 September 2013). "مشروع برنامج حزب الإرادة الشعبية". kassioun.org (in Arabic). Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Syrian rebels to choose interim defence minister | Middle East". World Bulletin. 29 March 2013. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d "HTS-backed civil authority moves against rivals in latest power grab in northwest Syria". Syria Direct. 13 December 2017. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "A power struggle over education emerges between rival opposition governments in Idlib province". Syria Direct. 10 January 2018. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "The Syrian General Conference Faces the Interim Government in Idlib". Enab Baladi. 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ a b Enab Baladi Online (opposition website) (9 November 2017). "Who Will Lead Idleb's New 'Salvation Government?'". The Syrian Observer. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ a b Allsopp, Harriet; van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (2019). The Kurds of Northern Syria. Volume 2: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts. London; New York City; etc.: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-83860-445-5

- ^ van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (2018/09/06). "New administration formed for northeastern Syria". Kurdistan24. Retrieved 2023/05/12.

- ^ "الرئاسة والنواب - الإدارة الذاتية لشمال وشرق سوريا" (in Arabic). 27 October 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ IMPACT - Civil Society Research and Development. "The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria Framework and Resources" (October 2019): 2.

- ^ "Will Syrian opposition move interim government to Idlib? – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. 7 April 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016.

- ^ Anton Mardasov (20 February 2017). "Why Moscow now sees value in Syrian local councils". Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Iran's Unwavering Support to Assad's Syria". 27 August 2013. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "World powers drawing up Syrian rebel 'terrorist' red list". 10 November 2015.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Country Reports on Terrorism 2017 - State Sponsors of Terrorism: Syria". Refworld.

- ^ Albayrak, Ayla (4 October 2011). "Turkey Plans Military Exercise on Syrian Border". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Syria Army Defectors Press Conference – 9–23–11". Syria2011archives. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ Bearing Witness in Syria: A Correspondent's Last Days Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. NYTimes (4 March 2012)

- ^ 1 week with the "free syrian army" – February 2012 – Arte reportage 1 of 2 Archived 3 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. YouTube. Retrieved on 23 March 2012.

- ^ Landis, Joshua (29 July 2011). "Free Syrian Army Founded by Seven Officers to Fight the Syrian Army". Syria Comment. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ^ "Defecting troops form 'Free Syrian Army', target Assad security forces". World Tribune. 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ^ "Syrian Army Colonel Defects forms Free Syrian Army". Asharq Alawsat. 1 August 2011. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ^ "Former Syrian Consulates Support Free Syrian Navy".

- ^ "Leading Syrian rebel groups form new Islamic Front". BBC. 22 November 2013. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ Aron Lund (23 March 2015). "Islamist Mergers in Syria: Ahrar al-Sham Swallows Suqour al-Sham". Carnegie Middle East Center. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Ghazal, Amal, Hanssen, Jens (2015). Ghazal, Amal; Hanssen, Jens (eds.). Contemporary Middle Eastern and North African History. Oxford University Press. p. 651. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199672530.001.0001. ISBN 9780191751387.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Syria Kurds adopt constitution for autonomous federal region". TheNewArab. 31 December 2016. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Our Team". Foundation for defense of democracies. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Syria's Kilo pledges to continue struggle". Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ Wright, Robin (2008). Dreams and Shadows: The Future of the Middle East. New York: Penguin Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-59420-111-0..

- ^ S, T. (5 March 2014). "Who's who: Abdulhakim Bashar". The Syrian Observer. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ spare (7 March 2014). "Abdulhakim Bachar". Syrian National Coalition Of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces. Retrieved 18 May 2023.