Columbine High School massacre

| Columbine High School massacre | |

|---|---|

Eric Harris (left) and Dylan Klebold (right) caught on the high school's security cameras in the cafeteria, 11 minutes before their suicides | |

| Location | Columbine, Colorado,[1] U.S. |

| Coordinates | 39°36′12″N 105°04′29″W / 39.60333°N 105.07472°W |

| Date | April 20, 1999 11:19 a.m. – 12:08 p.m. (UTC-6) |

| Target | Students and faculty at Columbine High School |

Attack type | School shooting, mass murder, murder–suicide, arson, attempted bombing, shootout |

| Weapons | |

| Deaths | 15 (including both perpetrators) |

| Injured | 24 (21 by gunfire) |

| Perpetrators | Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold |

| Defenders | William David Sanders Aaron Hancey[2] Neil Gardner[3] |

The Columbine High School massacre was a school shooting that occurred on April 20, 1999, at Columbine High School in Columbine,[4][5] an unincorporated area of Jefferson County, Colorado, United States, near Littleton in the Denver metropolitan area. The perpetrators, senior students Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, murdered 12 students and one teacher. They injured 21 additional people, and three more were injured while attempting to escape the school. The pair subsequently committed suicide.[6][7]

In addition to the shootings, the complex and highly planned attack involved several improvised explosive devices, including tossing pipe bombs, a bomb to divert firefighters, propane tanks converted to bombs placed in the cafeteria, and car bombs. The pair hoped that, after detonating the cafeteria bombs at the busiest lunch hour, killing hundreds of students, they would shoot the fleeing survivors. Then as police and first-responders came to the school, bombs set in their cars would detonate in the parking lot. That did not happen, since the bombs in the cafeteria and cars failed to detonate.

Their precise motives remain unclear, but the personal journals of the perpetrators document that they wished their actions to rival the Oklahoma City bombing and other deadly incidents in the United States in the 1990s. The attack has been referred to by USA Today as a "suicidal attack [that was] planned as a grand—if badly implemented—terrorist bombing."[8]

The massacre sparked debate over gun control laws, high school cliques, subcultures, and bullying. It resulted in an increased emphasis on school security with zero tolerance policies,[9][10] and a moral panic over goth culture, gun culture, social outcasts (though the perpetrators were not outcasts),[11][12] the use of pharmaceutical antidepressants by teenagers, teenage Internet use,[13] and violence in video games.[14][15]

Preliminary activities and intent

In 1996, Eric Harris created a private website on America Online, initially to host gaming levels he created for use in the video game Doom. On the site, Harris began a blog, which included jokes and short journal entries with thoughts on parents, school, and friends. By the end of the year, the site contained instructions on how to cause mischief, as well as instructions on how to make explosives, and blogs in which he described the trouble he and Klebold were causing. Beginning in early 1997, the blog postings began to show the first signs of Harris's ever-growing anger against society.[16]

Harris's site attracted few visitors, and caused no concern until March 1998. Klebold was aware of the site and gave the web address to his classmate Brooks Brown, in an effort to warn him of Harris's threats of violence against him and his family. Brown's mother had filed numerous complaints with the Jefferson County Sheriff's office concerning Harris, as she thought he was dangerous. After Brown's parents viewed the site, they did indeed contact the Jefferson County Sheriff's Office. Investigator Michael Guerra was told about the website.[16] When he accessed it, Guerra discovered numerous violent threats directed against the students and teachers of Columbine High School. Other material included blurbs that Harris had written about his general hatred of society, and his desire to kill those who annoyed him.

Harris had noted on his site that he had made pipe bombs, in addition to a hit list of individuals (he did not post any plan on how he intended to attack targets).[17] As Harris had posted on his website that he possessed explosives, Guerra wrote a draft affidavit, requesting a search warrant of the Harris household. The affidavit also mentioned a suspicion of Harris being involved in an unsolved pipe bomb case in February 1998. The affidavit was never filed.[16] It was concealed by the Jefferson County Sheriff's Office and not revealed until September 2001, resulting from an investigation by the TV show 60 Minutes.

After the revelation about the affidavit, a series of grand jury investigations were begun into the cover-up activities of Jefferson County officials. The investigation revealed that high-ranking county officials had met a few days after the massacre to discuss the release of the affidavit to the public. It was decided that because the affidavit's contents lacked the necessary probable cause to have supported the issuance of a search warrant for the Harris household by a judge, it would be best not to disclose the affidavit's existence at an upcoming press conference; the actual conversations and points of discussion were never revealed to anyone other than the grand jury members. Following the press conference, the original Guerra documents disappeared. In September 1999, a Jefferson County investigator failed to find the documents during a secret search of the county's computer system. A second attempt in late 2000 found copies of the document within the Jefferson County archives. The documents were reconstructed and released to the public in September 2001, but the original documents are still missing. The final grand jury investigation was released in September 2004.[citation needed]

On January 30, 1998, Harris and Klebold stole tools and other equipment from a van parked near the city of Littleton.[18] Both youths were arrested and subsequently attended a joint court hearing, where they pleaded guilty to the felony theft. The judge sentenced the duo to attend a juvenile diversion program. There, both boys attended mandated classes and talked with diversion officers. One of their classes taught anger management. Harris also began attending therapy classes with a psychologist. Klebold had a history of drinking and had failed a dilute urine test, but neither he nor Harris attended any substance abuse classes.[19]

Harris and Klebold were eventually released from diversion several weeks early because of positive actions in the program;[16] they were both on probation.[20] Shortly after Harris' and Klebold's court hearing, Harris's online blog disappeared. His website was reverted to its original purpose of posting user-created levels of Doom. Harris began to write in a journal, in which he recorded his thoughts and plans. In April 1998,[21] as part of his diversion program, Harris wrote a letter of apology to the owner of the van. Around the same time, he derided him in his journal, stating that he believed himself to have the right to steal something if he wanted to.[22][23] Harris continued his scheduled meetings with his psychologist until a few months before he and Klebold committed the Columbine High School massacre.

Harris dedicated a section of his website to posting content regarding his and Klebold's progress in their collection of guns and building of bombs (they subsequently used both in attacking students at their school). After the website was made public, AOL permanently deleted it from its servers.[24]

Medication

In one scheduled meeting with his appointed psychiatrist, Harris had complained of depression, anger, and suicidal thoughts. As a result, he was prescribed the anti-depressant Zoloft. He complained of feeling restless and having trouble concentrating; in April, his doctor switched him to Luvox, a similar anti-depressant drug.[25]

Journals and videos

Harris and Klebold both began keeping journals soon after their 1998 arrests. In these journals, the pair documented their arsenal with video tapes they kept secret.[16][26]

Their journals documented their plan for a major bombing to rival that of the Oklahoma City bombing. Their entries contained blurbs about ways to escape to Mexico, hijacking an aircraft at Denver International Airport and crashing it into a building in New York City, and details about the planned attack. The pair hoped that, after detonating their home-made explosives in the cafeteria at the busiest time of day, killing hundreds of students,[27] they would shoot survivors fleeing from the school. Then, as police vehicles, ambulances, fire trucks, and reporters came to the school, bombs set in the boys' cars would detonate, killing these emergency and other personnel. That did not happen, since these explosives did not detonate.[16][28]

The pair kept videos that documented the explosives, ammunition, and weapons they had obtained illegally. They revealed the ways they hid their arsenals in their homes, as well as how they deceived their parents about their activities. The pair shot videos of doing target practice in nearby foothills, as well as areas of the high school they planned to attack.[16] On April 20, approximately thirty minutes before the attack,[29] they made a final video saying goodbye and apologizing to their friends and families.

Firearms and explosives

In the months prior to the attacks, Harris and Klebold acquired two 9 mm firearms and two 12-gauge shotguns. Harris had a 12-gauge Savage-Springfield 67H pump-action shotgun (which he discharged a total of 25 times) and a Hi-Point 995 Carbine 9 mm carbine with thirteen 10-round magazines (which he fired a total of 96 times).[30][31] Klebold used a 9×19mm Intratec TEC-9 semi-automatic handgun with one 52-, one 32-, and one 28-round magazine and a 12-gauge Stevens 311D double-barreled sawed-off shotgun. Klebold fired the TEC-9 handgun 55 times, while he discharged a total of 12 rounds from his double-barreled shotgun.[30][31]

The multiple weapons obtained resembled the video game Doom, in which one switches between shotguns and other weapons depending on the monsters one has to shoot. The game's protagonist is depicted with a long gun like the carbine rifle, though he does not use it in the game, and the first zombie antagonist fires at you with a 9mm rifle. The second zombie antagonist fires at you with a shotgun, and the second gun the protagonist can acquire and use in the game is a pump-action shotgun. Doom 2 introduces the "super shotgun", which is a double-barreled shotgun. The Doom novels speak often of an AB-10 handgun, which resembles the TEC-9. Harris named his pump-action shotgun Arlene after a character in these novels.

Using instructions obtained via the Internet and the Anarchist Cookbook, they also constructed a total of 99 improvised explosive devices.[32] These included propane tanks converted to bombs, pipe bombs, CO2 cartridges with matches taped to them (which they called "crickets"), and car bombs.

In December 1998, their friend Robyn Anderson had purchased the carbine rifle and the two shotguns for the pair at the Tanner Gun Show, as they were too young to legally purchase the guns themselves.[33] Anderson made her purchase from a private seller, not a licensed dealer.[33] After the attack, she told investigators that she had believed the pair wanted the items for target shooting, and that she had no prior knowledge of their plans.[33][34] Anderson was not charged for supplying the guns to Harris and Klebold.[33][35] The Jefferson County Final Report on the Columbine High School Shootings explained that "No law, state or federal, prohibits the purchase of a long gun (rifle) from a private individual (non-licensed dealer). Because of this, Anderson could not be charged with any crime. If Anderson had purchased the guns from a federally licensed dealer, it would have been considered a “straw purchase” and considered illegal under federal law to make the purchase for Harris and Klebold."[36]

Through Philip Duran, a coworker, Harris and Klebold later bought a TEC-9 handgun from Mark Manes for $500.[37] After the massacre, Manes and Duran were prosecuted for their roles in supplying guns to Harris and Klebold.[38][39] Each was charged with supplying a handgun to a minor and possession of a sawed-off shotgun. Manes and Duran were sentenced to a total of six years and four-and-a-half years in prison, respectively.[40]

April 20, 1999: The massacre

Prior to the massacre

On Tuesday morning, April 20, 1999, Harris and Klebold placed a small fire bomb in a field about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Columbine High School, and 2 mi (3.2 km) south of the fire station.[41] Set to explode at 11:14 a.m., the bomb was intended as a diversion to draw firefighters and emergency personnel away from the school (it partially detonated and caused a small fire, which was quickly extinguished by the fire department).

At 11:10 a.m.,[42] Harris and Klebold arrived separately at Columbine High School. Harris parked his vehicle in the junior student parking lot, by the south entrance, and Klebold parked in the adjoining senior student parking lot, by the west entrance. The school cafeteria, their primary bomb target, with its long outside window-wall and ground-level doors, was between their parking spots.[43]

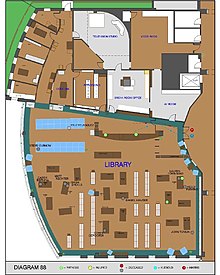

After parking their cars, each containing concealed car bombs timed to detonate at 12:00,[44] the duo met near Harris' car and armed a further two 20 pounds (9.1 kg) propane bombs before entering the cafeteria a few minutes prior to the beginning of the "A" lunch shift. The youths placed the duffel bags containing the bombs, set to explode at approximately 11:17 a.m.,[16] inside the cafeteria before returning to their separate vehicles to await the explosion and shoot survivors fleeing the building. Had these bombs exploded with full power, they would have killed or severely wounded all 488 students in the cafeteria and possibly collapsed the ceiling, dropping part of the library into the cafeteria.[45]

A Jefferson County Sheriff's Deputy, Neil Gardner, was assigned to the high school as a full-time uniformed and armed school resource officer. Gardner usually ate lunch with students in the cafeteria, but on April 20 he was eating lunch in his patrol car at the northwest corner of the campus, watching students in the Smokers' Pit in Clement Park.[46] The security staff at Columbine did not observe the bombs being placed in the cafeteria, since a custodian was replacing the school security video tape as it happened. The bags holding the bombs were first visible on the fresh security tape, but they were not identified as suspicious items. No witness recalled seeing the duffel bags being added to the 400 or so backpacks already in the cafeteria.[47]

As the two youths returned to their vehicles, Harris encountered their classmate Brooks Brown, with whom he had recently patched up a longstanding series of disagreements. Brown, who was in the parking lot smoking a cigarette, was surprised to see Harris, whom he had earlier noted had been absent from an important class test. Harris seemed unconcerned when reminded of this fact by Brown, commenting, "It doesn't matter anymore." Harris then elaborated: "Brooks, I like you now. Get out of here. Go home." Brown, feeling uneasy, walked away.[48] Several minutes later, students departing Columbine for their lunch break observed Brown heading down South Pierce Street away from the school. Meanwhile, Harris and Klebold armed themselves by their vehicles and waited for the bombs to explode.

11:19 a.m.: Shooting begins

When the cafeteria bombs failed to explode, Harris and Klebold convened and walked toward the school. Both armed, they climbed to the top of the outdoor west entrance steps, placing them on a level with the athletic fields west of the building and the library inside the west entrance, directly above the cafeteria. From this vantage point, the cafeteria's west entrance was located at the bottom of the staircase, next to the senior parking lot.

- 1. Rachel Scott, age 17. Killed by shots to the head, torso, and leg alongside the west entrance of the school.

- 2. Richard Castaldo, age 17. Shot in the arm, chest, back, and abdomen alongside the west entrance to the school.

- 3. Daniel Rohrbough, age 15. Fatally injured by shots to the abdomen and leg on the west staircase, shot through the upper chest at the base of the same staircase.

- 4. Sean Graves, age 15. Shot in the back, foot, and abdomen on the west staircase.

- 5. Lance Kirklin, age 16. Critically injured by shots to the leg, neck, and jaw on the west staircase.

- 6. Michael Johnson, age 15. Shot in the face, arm, and leg to the west of the staircase.

- 7. Mark Taylor, age 16. Shot in the chest, arms, and leg to the west of the staircase.

- 8. Anne-Marie Hochhalter, age 17. Shot in the chest, arm, abdomen, back, and left leg near the cafeteria's entrance.

- 9. Brian Anderson, age 17. Injured near the west entrance by flying glass.

- 10. Patti Nielson, age 35. Hit in the shoulder by shrapnel near the west entrance.

- 11. Stephanie Munson, age 17. Shot in the ankle inside the North Hallway.

- 12. William David Sanders, age 47. Died of blood loss after being shot in the neck and back inside the South Hallway.

At 11:19 a.m., 17-year-old Rachel Scott was having lunch with friend Richard Castaldo while sitting on the grass next to an auxiliary door at the west entrance of the school. Castaldo said he saw one of the boys throw a pipe bomb, which only partially detonated. Thinking the bomb was no more than a crude senior prank, Castaldo did not take it seriously. At that moment, a witness heard Eric Harris yell, "Go! Go!" The two gunmen pulled their guns from beneath their trench coats and began shooting at Castaldo and Scott.[49] Scott was killed when she was hit four times with 9mm rounds fired from Harris' Hi-Point 995.[50] Castaldo was shot eight times in the chest, arm, and abdomen and paralyzed below the chest, falling into unconsciousness.[16] It is unknown who fired first; Harris shot and killed Scott, and Castaldo reported that Scott was hit immediately before he was.[3]

After the first two shootings, Harris removed his trench coat and aimed his 9 mm carbine down the west staircase toward three youths: 15-year-olds Daniel Rohrbough and Sean Graves and 16-year-old Lance Kirklin. The three friends had been ascending the staircase directly below the shooters. Kirklin later reported seeing Klebold and Harris standing at the top of the staircase before the pair opened fire. All three youths were shot and wounded.[51] Inside the school, some of the students had believed that they were bearing witness to a senior prank by the two seniors. But in the cafeteria, Dave Sanders, a computer and business teacher as well as a varsity coach,[52] quickly realized it was not a prank but a deliberate attack on the school.

Harris and Klebold turned and began shooting west in the direction of five students sitting on the grassy hillside adjacent to the steps and opposite the west entrance of the school.[53] 15-year-old Michael Johnson was hit in the face, leg, and arm, but ran and escaped; 16-year-old Mark Taylor was shot in the chest, arms, and leg and fell to the ground, where he feigned death. The other three escaped uninjured.[47]

Klebold walked down the steps toward the cafeteria. He came up to Kirklin, who was already wounded and lying on the ground, weakly calling for help. Klebold said, "Sure. I'll help you,"[54] then shot Kirklin in the face, critically wounding him. Daniel Rohrbough and Sean Graves had descended the staircase when Klebold and Harris' attention was diverted by the students on the grass; Graves—paralyzed beneath the waist[55]—had crawled into the doorway of the cafeteria's west entrance and collapsed. Klebold shot Rohrbough, who was already fatally wounded by the shots previously fired by Harris, at close range through the upper left chest and then stepped over the injured Sean Graves to enter the cafeteria. Officials speculated that Klebold went to the cafeteria to check on the propane bombs. Harris shot down the steps at several students sitting near the cafeteria's entrance, severely wounding and partially paralyzing 17-year-old Anne-Marie Hochhalter[56] as she tried to flee. Klebold came out of the cafeteria and went back up the stairs to join Harris.[47]

They shot toward students standing close to a soccer field but did not hit anyone. They walked toward the west entrance, throwing pipe bombs, very few of which detonated.[16] Meanwhile, inside the school, Patti Nielson, an art teacher, had noticed the commotion and walked toward the west entrance with a 17-year-old student, Brian Anderson. She had intended to walk outside to tell the two students to "Knock it off,"[57] thinking Klebold and Harris were either filming a video or pulling a student prank. As Anderson opened the first set of double doors, Harris and Klebold shot out the windows, injuring him with flying glass and hitting Nielson in the shoulder with shrapnel. Nielson stood and ran back down the hall into the library, alerting the students inside to the danger and telling them to get under desks and keep silent. Nielson dialed 9-1-1 and hid under the library's administrative counter.[16] Anderson remained behind, caught between the exterior and interior doors.

11:22 a.m.: Police response

At 11:22, the custodian called Deputy Neil Gardner, the assigned resource officer to Columbine, on the school radio, requesting assistance in the senior parking lot. The only paved route took him around the school to the east and south on Pierce Street, where at 11:23 he heard on his police radio that a female was down, and assumed she had been struck by a car. While exiting his patrol car in the Senior lot at 11:24, he heard another call on the school radio, "Neil, there's a shooter in the school".[46] Harris, at the west entrance, immediately turned and fired ten shots from his carbine at Gardner, who was sixty yards away.[46] As Harris reloaded his carbine, Gardner leaned over the top of his car and fired four rounds at Harris from his service pistol. Harris ducked back behind the building, and Gardner momentarily believed that he had hit him. Harris then reemerged and fired at least four more rounds at Gardner (which missed and struck two parked cars), before retreating into the building.[46] No one was hit during the exchange of gunfire.[46][58] Gardner was not wearing his prescription eyeglasses and was unable to hit the shooters.[59]

Thus, five minutes after the shooting started, and two minutes after the first radio call, Gardner had engaged in a gunfight with one of the student shooters. There were already two students dead and ten wounded. Gardner reported on his police radio, "Shots in the building. I need someone in the south lot with me."[46]

The gunfight distracted Harris and Klebold from the injured Brian Anderson.[16] Anderson escaped to the library and hid inside an open staff break room. Back in the school, the duo moved along the main North Hallway, throwing pipe bombs and shooting at anyone they encountered. Klebold shot Stephanie Munson in the ankle; she was able to walk out of the school. The pair then shot out the windows to the East Entrance of the school. After proceeding through the hall several times and shooting toward—and missing—any students they saw, Harris and Klebold went toward the west entrance and turned into the Library Hallway.

Deputy Paul Smoker, a motorcycle patrolman for the Jefferson County Sheriff's Office, was writing a traffic ticket north of the school when the "female down" call came in at 11:23, most likely referring to the already dead Rachel Scott. Taking the shortest route, he drove his motorcycle over grass between the athletic fields and headed toward the west entrance. When he saw Deputy Scott Taborsky following him in a patrol car, he abandoned his motorcycle for the safety of the car. The two deputies had begun to rescue two wounded students near the ball fields when another gunfight broke out at 11:26, as Harris returned to the double doors and again began shooting at Deputy Gardner, who returned fire. From the hilltop, Deputy Smoker fired three rounds from his pistol at Harris, who again retreated into the building. As before, no one was hit.[46][47]

Inside the school, teacher Dave Sanders had successfully evacuated students from the cafeteria, where some of them went up a staircase leading to the second floor of the school.[16] The stairs were located around the corner from the Library Hallway in the main South Hallway. By now, Harris and Klebold were inside the main hallway. Sanders and another student were down at the end of the hallway still trying to secure as much of the school as they could. As they ran, they encountered Harris and Klebold, who were approaching from the corner of the North Hallway. Sanders and the student turned and ran in the opposite direction.[60] Harris and Klebold shot at them both, with Harris hitting Sanders twice in the chest but missing the student. The latter ran into a science classroom and warned everyone to hide. Klebold walked over towards Sanders, who had collapsed, to look for the student but returned to Harris up the North Hallway.

Sanders struggled toward the science area, and a teacher took him into a classroom where 30 students were located. They placed a sign in the window: "1 bleeding to death," in order to alert police and medical personnel of Sanders' location. Due to his knowledge of first aid, student Aaron Hancey was brought to the classroom from another by teachers despite the unfolding commotion. With the assistance of a fellow student named Kevin Starkey,[61] and teacher Teresa Miller, Hancey administered first aid to Sanders for three hours, attempting to stem the blood loss using shirts from students in the room. Using a phone in the room, Miller and several students maintained contact with police outside the school. All the students in this room were evacuated safely.

11:29 a.m. – 11:36 a.m.: Library massacre

As the shooting unfolded, Patti Nielson talked on the phone with emergency services, telling her story and urging students to take cover beneath desks.[16] According to transcripts, her call was received by a 9-1-1 operator at 11:25:05 a.m. The time between the call being answered and the shooters entering the library was four minutes and ten seconds. Before entering, the shooters threw two bombs into the cafeteria, both of which exploded. They then threw another bomb into the Library Hallway; it exploded and damaged several lockers. At 11:29 a.m., Harris and Klebold entered the library, where a total of 52 students, two teachers and two librarians had concealed themselves.[16]

Harris yelled, "Get up!" so loudly that he can be heard on Patti Nielson's 9-1-1 recording at 11:29:18.[62] Staff and students hiding in the library exterior rooms later said they also heard the gunmen say: "All jocks stand up! We'll get the guys in white hats!" (Wearing a white baseball cap at Columbine was a tradition among sports team members, typically jocks.)[16] When no one stood up in response, Harris said, "Fine, I'll start shooting anyway!" He fired his shotgun twice at a desk, not knowing that a student named Evan Todd was hiding beneath it. Todd was hit by wood splinters but was not seriously injured.[63]

The shooters walked to the opposite side of the library, to two rows of computers. Todd hid behind the administrative counter. Kyle Velasquez, 16, was sitting at the north row of computers; police later said he had not hidden underneath the desk when Klebold and Harris had first entered the library, but had curled up under the computer table. Klebold shot and killed Velasquez, hitting him in the head and back. Klebold and Harris put down their ammunition-filled duffel bags at the south—or lower—row of computers and reloaded their weapons. They walked back toward the windows facing the outside staircase. Noticing police evacuating students outside the school, Harris said: "Let's go kill some cops." He and Klebold began to shoot out the windows in the direction of the police. Officers returned fire, and Harris and Klebold retreated from the windows; no one was injured.[47][64]

- 13. Evan Todd, age 15. Sustained minor injuries from the splintering of a desk he was hiding under.

- 14. Kyle Velasquez, age 16. Killed by gunshot wounds to the head and back.

- 15. Patrick Ireland, age 17. Shot in the head and foot.

- 16. Daniel Steepleton, age 17. Shot in the thigh.

- 17. Makai Hall, age 18. Shot in the knee.

- 18. Steven Curnow, age 14. Killed by a shot to the neck.

- 19. Kacey Ruegsegger, age 17. Shot in the shoulder, hand and neck.

- 20. Cassie Bernall, age 17. Killed by a shotgun wound to the head.

- 21. Isaiah Shoels, age 18. Killed by a shot to the chest.

- 22. Matthew Kechter, age 16. Killed by a shot to the chest.

- 23. Lisa Kreutz, age 18. Shot in the shoulder, hand, arms and thigh.

- 24. Valeen Schnurr, age 18. Injured with wounds to the chest, arms and abdomen.

- 25. Mark Kintgen, age 17. Shot in the head and shoulder.

- 26. Lauren Townsend, age 18. Killed by multiple gunshot wounds to the head, chest and lower body.

- 27. Nicole Nowlen, age 16. Shot in the abdomen.

- 28. John Tomlin, age 16. Killed by multiple shots to the head and neck.

- 29. Kelly Fleming, age 16. Killed by a shotgun wound to the back.

- 30. Jeanna Park, age 18. Shot in the knee, shoulder and foot.

- 31. Daniel Mauser, age 15. Killed by a single shot to the face.

- 32. Jennifer Doyle, age 17. Shot in the hand, leg and shoulder.

- 33. Austin Eubanks, age 17. Shot in the hand and knee.

- 34. Corey DePooter, age 17. Killed by shots to the chest and neck.

After firing through the windows at evacuating students and the police, Klebold fired his shotgun at a nearby table, injuring three students: Patrick Ireland, Daniel Steepleton, and Makai Hall.[16] He removed his trench coat. As Klebold fired at the three, Harris grabbed his shotgun and walked toward the lower row of computer desks, firing a single shot under the first desk without looking. He hit 14-year-old Steven Curnow with a mortal wound to the neck. Harris then shot under the adjacent computer desk, injuring 17-year-old Kacey Ruegsegger with a shot which passed completely through her right shoulder and hand, also grazing her neck and severing a major artery.[65] When she started gasping in pain, Harris tersely stated, "Quit your bitching."[66]

Harris walked over to the table across from the lower computer row, slapped the surface twice and knelt, saying "Peek-a-boo" to 17-year-old Cassie Bernall before shooting her once in the head, killing her instantly.[67] Harris had been holding the shotgun with one hand at this point and the weapon hit his face in recoil, breaking his nose. Initial reports suggest that Harris asked Bernall "Do you believe in God?", to which she replied yes, before getting killed. Three students who witnessed Bernall's death, including Emily Wyant, who had been hiding beneath the table with her, have testified that Bernall did not exchange words with Harris after his initial taunt; Wyant stated Bernall had been praying prior to her murder.[68]

After fatally shooting Bernall, Harris turned toward the next table, where Bree Pasquale sat next to the table rather than under it. Harris asked Pasquale if she wanted to die, and she responded with a plea for her life. Witnesses later reported that Harris seemed disoriented—possibly from the heavily bleeding wound to his nose. As Harris taunted Pasquale, Klebold noted Ireland trying to provide aid to Hall, who had suffered a wound to his knee. As Ireland tried to help Hall, his head rose above the table; Klebold shot him a second time, hitting him twice in the head and once in the foot.[16] Ireland was knocked unconscious, but survived.

Klebold walked toward another set of tables, where he discovered 18-year-old Isaiah Shoels, 16-year-old Matthew Kechter and 16-year-old Craig Scott (the younger brother of Rachel Scott), hiding under one table. All three were popular athletes. Klebold tried to pull Shoels out from under the table. He called to Harris, referring to him by his online identity and shouting, "Reb! There's a nigger over here!"[69] Harris left Pasquale and joined him. According to witnesses, Klebold and Harris taunted Shoels for a few seconds, making derogatory racial comments.[16] Harris knelt down and shot Shoels once in the chest at close range, killing him instantly. Klebold also knelt down and opened fire, hitting and killing Kechter. Harris then yelled; "Who's ready to die next?".[70] Meanwhile, Scott was uninjured; he lay in the blood of his friends, feigning death.[16] Harris turned and threw a CO2 bomb at the table where Hall, Steepleton, and Ireland were located. It landed on Steepleton's thigh, and Hall quickly threw it away.

Harris walked toward the bookcases between the west and center section of tables in the library. He jumped on one and shook it, then shot in an unknown direction within that general area. Klebold walked through the main area, past the first set of bookcases, the central desk area and a second set of bookcases into the east area. Harris walked from the bookcase he had shot from, past the central area to meet Klebold. The latter shot at a display case located next to the door, then turned and shot toward the closest table, hitting and injuring 17-year-old Mark Kintgen in the head and shoulder. He then turned toward the table to his left and fired, injuring 18-year-olds Lisa Kreutz and Valeen Schnurr with the same shotgun blast. Klebold then moved toward the same table and fired with the TEC-9, killing 18-year-old Lauren Townsend. At this point, the seriously injured Valeen Schnurr began screaming, "Oh my God, oh my God!"[71] In response, Klebold asked Schnurr if she believed in the existence of God; when Schnurr replied she did, Klebold simply asked "Why?" before walking from the table.[72]

Harris approached another table where two girls were hiding. He bent down to look at them and dismissed them as "pathetic".[73] Harris then moved to another table where he fired twice, injuring 16-year-olds Nicole Nowlen and John Tomlin. When Tomlin attempted to move away from the table, Klebold kicked him. Harris then taunted Tomlin's attempt at escape before Klebold shot the youth repeatedly, killing him. Harris then walked back over to the other side of the table where Lauren Townsend lay dead. Behind the table, a 16-year-old girl named Kelly Fleming had, like Bree Pasquale, sat next to the table rather than beneath it due to a lack of space. Harris shot Fleming with his shotgun, hitting her in the back and killing her instantly. He shot at the table behind Fleming, hitting Townsend and Kreutz again, and wounding 18-year-old Jeanna Park.[74] An autopsy later revealed that Townsend died from the earlier gunshots inflicted by Klebold.

The shooters moved to the center of the library, where they continued to reload their weapons at a table there. Harris noticed a student hiding nearby and asked him to identify himself. It was John Savage, an acquaintance of Klebold's, who had come to the library to study for a history test. Savage said his name, believing they were targeting only jocks (which he himself was not), in an attempt to save his life; he then asked Klebold what they were doing, to which he answered, "Oh, just killing people." Savage asked if they were going to kill him. Possibly because of a fire alarm, Klebold said, "What?" Savage asked again whether they were going to kill him. Klebold hesitated, then told him to leave. Savage fled immediately, and escaped through the library's main entrance.[75]

After Savage had left, Harris turned and fired his carbine at the table directly north of where they had been, grazing the ear of 15-year-old Daniel Mauser. When Mauser fought back, shoving a chair at Harris, Harris fired again and hit Mauser in the face at close range, killing him. Both shooters moved south and fired randomly under another table, critically injuring two 17-year-olds, Jennifer Doyle and Austin Eubanks, and fatally wounding 17-year-old Corey DePooter. DePooter, the last to die in the massacre, at 11:35, was later credited with having kept his friends calm during the ordeal.[47][76]

There were no further injuries after 11:35 a.m. They had killed 10 people in the library and wounded 12. Of the 56 library hostages, 34 remained unharmed. Investigators would later find that the shooters had enough ammunition to have killed them all.[47]

At this point, several witnesses later said they heard Harris and Klebold comment that they no longer found a thrill in shooting their victims. Klebold was quoted as saying, "Maybe we should start knifing people, that might be more fun." (Both youths were equipped with knives.) They moved away from the table and went toward the library's main counter. Harris threw a Molotov cocktail toward the southwestern end of the library, but it failed to explode. Harris went around the east side of the counter and Klebold joined him from the west; they converged close to where Todd had moved after having been wounded. Harris and Klebold mocked Todd, who was wearing a white hat. When the shooters demanded to see his face, Todd partly lifted his hat so his face would remain obscured. When Klebold asked Todd to give him one reason why he should not kill him, Todd said: "I don't want trouble." Klebold said, "You [Todd] used to call me a fag. Who's a fag now?!" The shooters continued to taunt Todd and debated killing him, but they eventually walked away.

Harris's nose was bleeding heavily, which may have caused him to decide to leave the library. Klebold turned and fired a single shot into an open library staff break room, hitting a small television. Before they left, Klebold slammed a chair down on top of the computer terminal and several books on the library counter, directly above the bureau where Patti Nielson had hidden.

The two walked out of the library at 11:36 a.m., ending the hostage situation there. Cautiously, fearing the shooters' return, 34 uninjured and 10 injured survivors began to evacuate the library through the north door, which led to the sidewalk adjacent to the west entrance. Kacey Ruegsegger was evacuated from the library by Craig Scott. Had she not been evacuated at this point, Ruegsegger would likely have bled to death from her injuries.[77] Patrick Ireland, unconscious, and Lisa Kreutz, unable to move, remained in the building.[78] Patti Nielson joined Brian Anderson and the three library staff in the exterior break room, into which Klebold had earlier fired shots. They locked themselves in and remained there until they were freed, at approximately 3:30 p.m.

12:08 p.m.: Suicide of the perpetrators

After leaving the library, Harris and Klebold entered the science area, where they threw a small fire bomb into an empty storage closet. It caused a fire, which was put out by a teacher hidden in an adjacent room. The duo proceeded toward the south hallway, where they shot into an empty science room. At approximately 11:44 a.m., Harris and Klebold were captured on the school security cameras as they re-entered the cafeteria.[16] The recording shows Harris kneeling on the landing and firing a single shot toward one of the propane bombs he and Klebold had earlier left in the cafeteria, in an unsuccessful attempt to detonate it. He took a sip from one of the drinks left behind as Klebold approached the propane bomb and examined it. Klebold lit a Molotov cocktail and threw it at the propane bomb. As the two left the cafeteria, the Molotov cocktail exploded, partially detonating one of the propane bombs at 11:46 a.m.[79] Two minutes later, approximately one gallon of fuel ignited in the same vicinity, causing a fire that was extinguished by the fire sprinklers.[80]

After leaving the cafeteria, the duo returned to the main north and south hallways of the school, shooting aimlessly. Harris and Klebold walked through the south hallway into the main office before returning to the north hallway. On several occasions, the pair looked through the windows of classroom doors, making eye contact with students hidden inside, but neither Harris nor Klebold tried to enter any of the rooms. They even reloaded their firearms close by the room that Dave Sanders was in. After leaving the main office, Harris and Klebold walked toward a bathroom, where they taunted students hidden inside, making such comments as: "We know you're in there" and "Let's kill anyone we find in here." Neither attempted to enter the bathroom. At 11:55 a.m., the two returned to the cafeteria, where they briefly entered the school kitchen. They returned up the staircase and into the south hallway at 11:58 a.m.

Harris and Klebold reentered the library, presumably to watch their car bombs detonate, which had been set to explode at noon, but which failed. The library was empty of surviving students except for the unconscious Patrick Ireland and the injured Lisa Kreutz. Once inside, at 12:02 p.m., they shot through the west windows at police, who returned fire. Nobody was injured in the exchange.

- 35. Eric Harris, age 18. Committed suicide by a single shot to the mouth.

- 36. Dylan Klebold, age 17. Committed suicide by a single shot to the head.

By approximately 12:08 p.m., both Harris and Klebold had committed suicide: Harris by firing his shotgun through the roof of his mouth; Klebold by shooting himself in the left temple with his TEC-9.[81] An article by The Rocky Mountain News stated that Patti Nielson overheard Harris and Klebold suddenly shout "One! Two! Three!" in unison, just before a loud boom.[81] However, Nielson has said that she at no time had ever spoken with either of the writers of the article,[82] and evidence suggests Harris killed himself first. Just before committing suicide, Klebold lit a Molotov cocktail on a nearby table, underneath which lay Patrick Ireland, which caused the tabletop to momentarily catch fire. Underneath the scorched film of material was a piece of Harris's brain matter, suggesting Harris had shot himself by this point.

In 2002, the National Enquirer published two photos of Harris and Klebold after their suicides, showing both dead laying on their backs, and the guns in seemingly curious locations, such as Klebold's right hand laying on his gun despite his being left-handed, and leading to speculation that Harris shot Klebold before killing himself. However, the photographs were taken after SWAT had checked the bodies for bombs and booby-traps, and likely kicked Klebold onto his back.

Patrick Ireland had regained and lost consciousness several times after being shot by Klebold. He crawled to the library windows where, at 2:38 p.m., he stretched out the window, intending to fall into the arms of two SWAT team members standing on the roof of an emergency vehicle, but instead falling directly onto the vehicle's roof in a pool of blood. They were later criticized for allowing Ireland to drop more than seven feet to the ground while doing nothing to try to ensure he could be lowered to the ground safely or break his fall. Eighteen-year-old Lisa Kreutz, shot in the shoulder, arms, hand, and thigh, remained in the library. In a subsequent interview, she recalled hearing a comment such as, "You in the library," around the time of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold's suicides. Kreutz lay in the library, keeping track of time by the sound of the school's bells until police arrived. She had tried to move but became light-headed.[16] She was finally evacuated at 3:22 p.m., along with Patti Nielson, Brian Anderson and the three library staff who had hidden in the break room.

Crisis ends

By noon, SWAT teams were stationed outside the school, and ambulances started taking the wounded to local hospitals. Meanwhile, families of students and staff were asked to gather at nearby Leawood Elementary School to await information.

A call for additional ammunition for police officers in case of a shootout came at 12:20 p.m. The killers had ceased shooting just minutes earlier. Authorities reported pipe bombs by 1:00 p.m., and two SWAT teams entered the school at 1:09 p.m., moving from classroom to classroom, discovering hidden students and faculty.[16] All students, teachers, and school employees were taken away, questioned, and offered medical care in small holding areas before being bussed to meet with their family members at Leawood Elementary. By 3:00 p.m., Dave Sanders had died of his injuries before SWAT officers could take him to get medical care. He was the only teacher to die in the shooting. Officials found the bodies in the library by 3:30 p.m.[83]

By 4:00 p.m., the sheriff made an initial estimate of 25 dead students and teachers. The estimate was ten over the true count, but close to the total count of wounded students. He said that police officers were searching the bodies of Harris and Klebold. At 4:30 p.m. the school was declared safe. At 5:30 p.m., additional officers were called in, as more explosives were found in the parking lot and on the roof. By 6:15 p.m., officials had found a bomb in Klebold's car in the parking lot. The sheriff decided to mark the entire school as a crime scene. Thirteen of the dead, including the shooters, were still inside the school at the time. At 10:40 p.m., a member of the bomb squad, who was attempting to dispose of an un-detonated pipe bomb, accidentally lit a striking match attached to the bomb by brushing it against the wall of the ordnance disposal trailer. The bomb detonated inside the trailer but no one was injured.[45]

The total count of deaths was 12 students and one teacher; 20 students and one teacher were injured as a result of the shootings. Three more victims were injured indirectly as they tried to escape the school. Harris and Klebold are thought to have committed suicide about 49 minutes after they started the massacre.

A total of 188 rounds of ammunition were fired by the perpetrators during the massacre (67 by Klebold and 121 by Harris). Additionally, law enforcement officers fired a total of 141 rounds during exchanges of gunfire with the shooters.[84]

Immediate aftermath

On April 21, bomb squads combed the high school. At 10:00 a.m., the bomb squad declared the building safe for officials to enter. By 11:30 a.m., a spokesman of the sheriff declared the investigation underway. Thirteen of the bodies were still inside the high school as investigators photographed the building.[85]

At 2:30 p.m., a press conference was held by Jefferson County District Attorney David Thomas and Sheriff John Stone, at which they said that they suspected others had helped plan the shooting. Formal identification of the dead had not yet taken place, but families of the children thought to have been killed had been notified. Throughout the late afternoon and early evening, the bodies were gradually removed from the school and taken to the Jefferson County Coroner's Office to be identified and autopsied. By 5:00 p.m., the names of many of the dead were known. An official statement was released, saying there were 15 confirmed deaths and 27 injuries related to the massacre.[85]

On April 30, high-ranking officials of Jefferson County and the Jefferson County Sheriff's Office met to decide if they should reveal that Michael Guerra, a Sheriff's Office detective, had drafted an affidavit for a search warrant of Harris's residence more than a year before the shootings, based on his previous investigation of Harris's website and activities.[86] They decided not to disclose this information at a press conference held on April 30, nor did they mention it in any other way. Over the next two years, Guerra's original draft and investigative file documents were lost. Their loss was termed "troubling" by a grand jury convened after the file's existence was reported in April 2001.[87]

In the months following the shooting, considerable media attention focused upon Cassie Bernall, who had been killed by Harris in the library and who Harris was reported to have asked, "Do you believe in God?" immediately prior to her murder.[88] Bernall was reported to have responded "Yes" to this question before her murder. Emily Wyant, the closest living witness to Bernall's death, denied that Bernall and Harris had such an exchange.[89]

Survivor Valeen Schnurr claims that she was the one questioned as to her belief in God by Harris.[89] Joshua Lapp thought Bernall had been queried about her belief, but was unable to correctly point out where Bernall was located, and was closer to Schnurr during the shootings. Another witness, Craig Scott, whose sister Rachel Scott was also portrayed as a Christian martyr, claimed that the discussion was with Bernall. When asked to indicate where the conversation had been coming from, he pointed to where Schnurr was shot.

Nevertheless, Bernall and Rachel Scott came to be regarded as Christian martyrs by Evangelical Christians.[90][91]

Rationale

The conclusion of the FBI was that Harris was a clinical psychopath, and Klebold was depressive.[92] Dr. Dwayne Fuselier, the supervisor in charge of the Columbine investigation, would later remark: "I believe Eric went to the school to kill and didn't care if he died, while Dylan wanted to die and didn't care if others died as well."[93]

According to this theory, Harris had been the mastermind, having a messianic-level superiority complex, and hoping to demonstrate his superiority to the world.[92] Klebold had repeatedly documented his desires to commit suicide in his diaries, and had primarily participated in the massacre as a means to simply end his life.[94][92] Klebold's final remark in the videotape he and Harris made shortly before their attack upon Columbine High School is a resigned statement made as he glances away from the camera: "Just know I'm going to a better place. I didn't like life too much."[95]

Harris's journals show methodical preparation for the massacre over a long period of time, including several experimental bomb detonations.[96][97] In contrast, by far the most prevalent theme in Klebold's journals is his private despair at his lack of success with women, which he refers to as an "infinite sadness."[98]

However, it was Klebold and not Harris who first mentioned going on a killing spree in his journal, and there is evidence to suggest both were depressed. Harris had been prescribed the SSRI antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox);[99] toxicology reports confirmed that Harris had fluvoxamine in his bloodstream at the time of the shootings.[100] Klebold had no medications in his system.[101]

Other factors explored

Bullying

The link between bullying and school violence has attracted increasing attention since the 1999 attack at Columbine High School. Both of the shooters were classified as gifted children who had allegedly been victims of bullying for four years. According to Brooks Brown, Klebold and Harris were the most ostracized students in the entire school, and even many of those close to them regarded the two as "the losers of the losers".[102] Klebold is known to have remarked to his father of his hatred of the jock culture at Columbine, adding that Harris in particular had been victimized by this social group. In this remark, Klebold had stated, "They sure give Eric hell."[103] On another occasion just weeks before the massacre,[104] both Harris and Klebold had been confronted by a group of youths at the school—all members of the football team—who had sprayed them with ketchup and mustard while referring to the pair as "faggots" and "queers".[105]

A year after the massacre, an analysis by officials at the U.S. Secret Service of 37 premeditated school shootings found that bullying, which some of the shooters described "in terms that approached torment", played the major role in more than two-thirds of the attacks.[106] A similar theory was expounded by Brooks Brown in his book on the massacre; he noted that teachers commonly looked the other way when confronted with bullying,[48] and that whenever Klebold and Harris were the recipients of such incidents from the jocks at Columbine, they would make statements such as: "Don't worry, man. It happens all the time!" if anyone expressed shock or surprise.[107]

Early stories following the shootings charged that school administrators and teachers at Columbine had long condoned a climate of bullying by the so-called jocks or athletes, allowing an atmosphere of intimidation and resentment to fester. Critics said this could have contributed to triggering the perpetrators' extreme violence.[108] Reportedly, homophobic remarks were directed at Klebold and Harris.[109]

One author has strongly disputed the theory of "revenge for bullying" as a motivation for the actions of Harris and Klebold. David Cullen, author of the 2009 book Columbine, while acknowledging the pervasiveness of bullying in high schools including Columbine, has claimed that the two were not victims of bullying. Cullen said that Harris was more often the perpetrator than victim of bullying.[110]

Social climate

During and after the initial investigations, social cliques within high schools were widely discussed. One perception formed was that both Klebold and Harris had been isolated from their classmates, prompting feelings of helplessness, insecurity, and depression, as well as a strong need for attention. This concept has been questioned, as both Harris and Klebold had a close circle of friends and a wider informal social group.[111]

Goth subculture

In the weeks following the Columbine shootings, media reports about Harris and Klebold portrayed them as part of a gothic cult. An increased suspicion of goth subculture subsequently manifested.[112] Harris and Klebold had initially been thought to be members of "The Trenchcoat Mafia"; an informal club within Columbine High School. Later, such characterizations were considered incorrect.[113]

Video games

Both Harris and Klebold were fans of video games such as Doom, Wolfenstein 3D, Duke Nukem, and Quake. Harris often created levels for Doom that were widely distributed; these can still be found on the Internet as the Harris levels. Rumors that the layout of these levels resembled that of Columbine High School circulated, but appear to be untrue.[114] Harris spent a great deal of time creating another large mod, named Tier, calling it his "life's work."[115] The mod was uploaded to the Columbine school computer and to AOL shortly before the attack, but appears to have been lost. One researcher argued that it is almost certain the Tier mod included a mock-up of Columbine High School.[19]

Parents of some of the victims filed several unsuccessful lawsuits against video game manufacturers.[116][117]

Natural Born Killers

Harris and Klebold were fans of the movie Natural Born Killers, and used the film's acronym, NBK, as a code in their home videos and journals.[19]

Music

Blame for the shootings was directed on a number of metal or 'dark music' bands such as KMFDM and Rammstein.[118] The majority of that blame was directed at Marilyn Manson and his eponymous band.[119][120] After being linked by news outlets and pundits with sensationalist headlines such as "Killers Worshipped Rock Freak Manson" and "Devil-Worshipping Maniac Told Kids To Kill",[121][122] many came to believe that Manson's music and imagery were, indeed, Harris and Klebold's sole motivation,[123] despite later reports that the two were not fans.[113][124]

In the immediate aftermath, the band canceled the remaining North American dates of their Rock Is Dead Tour out of respect for the victims, while steadfastly maintaining that music, movies, books or video games were not to blame. Manson stated:[125][126][127][128]

The media has unfairly scapegoated the music industry and so-called Goth kids and has speculated, with no basis in truth, that artists like myself are in some way to blame. This tragedy was a product of ignorance, hatred and an access to guns. I hope the media's irresponsible finger-pointing doesn't create more discrimination against kids who look different.[125]

On May 1, 1999, Manson expanded his rebuttal to the accusations leveled at him and his band in his Rolling Stone magazine op-ed piece, "Columbine: Whose Fault Is It?" He castigated the ensuing hysteria and moral panic and criticized the news media for their irresponsible coverage; he chastised America's habit of hanging blame on scapegoats to escape responsibility.[129][130][131] Columbine and America's fixation on a culture of guns, blame, and "celebrity by death" was further explored in the group's 2000 album Holy Wood.

In 2002, Manson appeared in Michael Moore's documentary, Bowling for Columbine; his appearance was filmed during the band's first show in Denver since the shooting. When Moore asked Manson what he would have said to the students at Columbine, he replied, "I wouldn't say a single word to them. I would listen to what they have to say and that's what no one did."[132]

Sascha Konietzko of KMFDM said their music denounced "war, oppression, fascism and violence against others."[118]

Impact on school policies

Secret Service report on school shootings

A United States Secret Service study concluded that schools were placing false hope in physical security, when they should be paying more attention to the pre-attack behaviors of students. Zero-tolerance policies and metal detectors "are unlikely to be helpful," the Secret Service researchers found. The researchers focused on questions concerning the reliance on SWAT teams when most attacks are over before police arrive, profiling of students who show warning signs in the absence of a definitive profile, expulsion of students for minor infractions when expulsion is the spark that push some to return to school with a gun, buying software not based on school shooting studies to evaluate threats although killers rarely make direct threats, and reliance on metal detectors and police officers in schools when shooters often make no effort to conceal their weapons.[133]

In May 2002, the Secret Service published a report that examined 37 U.S. school shootings. They had the following findings:

- Incidents of targeted violence at school were rarely sudden, impulsive acts.

- Prior to most incidents, other people knew about the attacker's idea or plan to attack.

- Most attackers did not threaten their targets directly prior to advancing the attack.

- There is no accurate or useful profile of students who engaged in targeted school violence.

- Most attackers engaged in some behavior prior to the incident that caused others concern or indicated a need for help.

- Most attackers had difficulty coping with significant losses or personal failures. Moreover, many had considered or attempted suicide.

- Many attackers felt bullied, persecuted, or injured by others prior to the attack.

- Most attackers had access to and had used weapons prior to the attack.

- In many cases, other students were involved in some capacity.

- Despite prompt law enforcement responses, most shooting incidents were stopped by means other than law enforcement intervention.[134]

School security

Following the Columbine shooting, schools across the United States instituted new security measures such as see-through backpacks, metal detectors, school uniforms, and security guards. Some schools implemented school door numbering to improve public safety response. Several schools throughout the country resorted to requiring students to wear computer-generated IDs.[135] At the same time, police departments reassessed their tactics and now train for Columbine-like situations after criticism over the slow response and progress of the SWAT teams during the shooting.[136]

Anti-bullying policies

In response to expressed concerns over the causes of the Columbine High School massacre and other school shootings, some schools renewed existing anti-bullying policies, in addition to adopting a zero tolerance approach to possession of weapons and threatening behavior by students.[137] Despite the Columbine incident, several social science experts feel the zero tolerance approach adopted in schools has been implemented too harshly, with unintended consequences creating other problems.[138]

Long-term impact

Police tactics

One significant change to police tactics following Columbine is the introduction of the Immediate Action Rapid Deployment tactic, used in situations with an active shooter. Police followed the traditional tactic at Columbine: surround the building, set up a perimeter, and contain the damage. That approach has been replaced by a tactic that takes into account the presence of an active shooter whose interest is to kill, not to take hostages. This tactic calls for a four-person team to advance into the site of any ongoing shooting, optimally a diamond-shaped wedge, but even with just a single officer if more are not available. Police officers using this tactic are trained to move toward the sound of gunfire and neutralize the shooter as quickly as possible.[139] Their goal is to stop the shooter at all costs; they are to walk past wounded victims, as the aim is to prevent the shooter from killing or wounding more. David Cullen, author of Columbine, has stated: "The active protocol has proved successful at numerous shootings during the past decade. At Virginia Tech alone, it probably saved dozens of lives."[140]

Gun control

The shooting resulted in calls for more gun control measures. In 2000 federal and state legislation was introduced that would require safety locks on firearms as well as ban the importation of high-capacity ammunition magazines. Though laws were passed that made it a crime to buy guns for criminals and minors, there was considerable controversy over legislation pertaining to background checks at gun shows. There was concern in the gun lobby over restrictions on Second Amendment rights in the United States.[141][142] In 2001, K-Mart, which had sold ammunition to the shooters, announced it would no longer sell handgun ammunition.[143] This action was encouraged by Michael Moore, writer and director of the award-winning 2002 documentary Bowling for Columbine.[144]

Memorials

In 2000, youth advocate Melissa Helmbrecht organized a remembrance event in Denver featuring two surviving students, called the "Day of Hope."[145][146]

A permanent memorial "to honor and remember the victims of the April 20, 1999 shootings at Columbine High School" was dedicated on September 21, 2007, in Clement Park, a meadow adjacent to the school where impromptu memorials were held in the days following the shooting. The memorial fund raised $1.5 million in donations over eight years of planning.[147]

Becoming part of the vernacular

Since the shooting, "Columbine" or "the Columbine incident" has become a euphemism for a school shooting. Charles Andrew Williams, the Santana High School shooter, reportedly told his friends that he was going to "pull a Columbine," though none of them took him seriously. Many foiled school shooting plots mentioned Columbine and the desire to "outdo Harris and Klebold."[148] Convicted students Brian Draper and Torey Adamcik of Pocatello High School in Idaho, who murdered their classmate Cassie Jo Stoddart, mentioned Harris and Klebold in their homemade videos, and were reportedly planning a "Columbine-like" shooting.[149]

In a self-made video recording posted by Seung-Hui Cho to the news media immediately prior to his committing the Virginia Tech shootings,[150] Cho referred the Columbine massacre in an apparent reference to his motivation for his own acts. In the recording, he also referred to Harris and Klebold as being "martyrs."[151]

Fandom

Since the advent of online social media, a fandom for shooters Harris and Klebold has had a documented presence on social media sites, especially Tumblr.[152] Fans of Harris and Klebold referred to themselves "Columbiners."[153] The group gained widespread media attention in February 2015 after three of its members conspired to commit a mass shooting at a Halifax mall on Valentine's Day.[154] An article published in 2015 in the Journal of Transformative Works, a scholarly journal which focuses on the sociology of fandoms, noted that Columbiners were not fundamentally functionally different from more mainstream fandoms. Columbiners create fan art and fan fiction, as well as having a scholarly interest in the shooting.[155]

Influence on subsequent school shootings

The Columbine shootings influenced subsequent school shootings.[151]

In 2009 sociologist Ralph Larkin of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at City University of New York wrote that Harris and Klebold established a script for subsequent school shootings. Larkin examined twelve major school shootings in the United States in the eight years after Columbine and found that in eight of those, "the shooters made explicit reference to Harris and Klebold."[156] Larkin concluded:

Harris and Klebold committed their rampage shooting as an overtly political act in the name of oppressed students victimized by their peers. Numerous post-Columbine rampage shooters referred directly to Columbine as their inspiration; others attempted to supersede the Columbine shootings in body count. ... The Columbine shootings redefined such acts not merely as revenge but as a means of protest of bullying, intimidation, social isolation, and public rituals of humiliation.[157]

In 2012 sociologist Nathalie E. Paton of the National Center for Scientific Research in Paris analyzed the online videos created by post-Columbine school shooting perpetrators. A recurring set of motifs was found, including self-portraits with firearms in which the perpetrator points his gun "at the camera, then at his own temple, and then spreads his arms wide with a gun in each hand; the closeup" and "the wave goodbye at the end," as well as explicit statements of admiration and identification with previous perpetrators. Paton said the videos serve the perpetrators by distinguishing themselves from their classmates and associating themselves with the previous perpetrators.[156][158]

A 2014 investigation by ABC News identified "at least 17 attacks and another 36 alleged plots or serious threats against schools since the assault on Columbine High School that can be tied to the 1999 massacre." Ties identified by ABC News included online research by the perpetrators into the Columbine shooting, clipping news coverage and images of Columbine, explicit statements of admiration of Harris and Klebold, such as writings in journals and on social media, in video posts, and in police interviews, timing planned to an anniversary of Columbine, plans to exceed the Columbine victim counts, and other ties.[159]

A 2015 investigation by CNN identified "more than 40 people...charged with Columbine-style plots." According to psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey of the Treatment Advocacy Center, a legacy of the Columbine shootings is its "allure to disaffected youth."[160] In 2017, two 15 year old school boys from Northallerton, North Yorkshire, UK were charged with conspiracy to murder after becoming infatuated with the crime and "hero-worshipping" the two perpetrators. The two boys plotted to emulate the actions of Harris and Klebold before being arrested.[161]

In 2015 journalist Malcolm Gladwell writing in The New Yorker magazine proposed a threshold model of school shootings in which Harris and Klebold were the triggering actors in "a slow-motion, ever-evolving riot, in which each new participant's action makes sense in reaction to and in combination with those who came before."[156][162]

Lawsuits against state agencies and families of perpetrators

After the massacre, many survivors and relatives of deceased victims filed lawsuits. Under Colorado state law at the time, the maximum a family could receive in a lawsuit against a government agency was $600,000.[163] Most cases against the Jefferson County police department and school district were dismissed by the federal court on the grounds of government immunity.[164] The case against the sheriff's office regarding the death of teacher Dave Sanders was not dismissed due to the police preventing paramedics from going to his aid for hours after they knew Harris and Klebold were dead. The case was settled out of court in August 2002 for $1,500,000.[165]

In April 2001, the families of more than 30 victims received a $2,538,000 settlement in their case against the families of Eric Harris, Dylan Klebold, Mark Manes, and Phillip Duran.[166] Under the terms of the settlement, the Harrises and the Klebolds contributed $1,568,000 through their homeowners' policies, with another $32,000 set aside for future claims; the Manes contributed $720,000, with another $80,000 set aside for future claims; and the Durans contributed $250,000, with an additional $50,000 available for future claims.[166] The family of Isaiah Shoels, the only African-American victim, rejected this settlement, but in June 2003 were ordered by a judge to accept a $366,000 settlement in their $250-million lawsuit against the shooters' families.[167][168] In August 2003, the families of victims Daniel Rohrbough, Kelly Fleming, Matt Kechter, Lauren Townsend, and Kyle Velasquez received undisclosed settlements in a wrongful death suit against the Harrises and Klebolds.[167]

See also

- Columbine High School massacre in popular culture

- Columbine (book)

- A Mother's Reckoning, 2016 memoir by Klebold's mother

- Gun violence in the United States

- Mass shootings in the United States

- List of attacks related to secondary schools

- List of school-related attacks

- List of school shootings in the United States

- I'm Not Ashamed

- W. R. Myers High School shooting – believed to be a copycat crime

References

Specific

- ^ "2010 CENSUS – CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Columbine CDP, CO Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine" U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on April 25, 2015. The school's location is on Pierce Street, which runs north-south through Columbine, roughly one mile west of the Littleton city limit.

- ^ Trostle, Pat (February 2, 2000). "Columbine hero has local ties". Archived from the original on March 10, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Massacre at Columbine High". Zero Hour. Season 1. Episode 3. 2004. History.

- ^ "Columbine High School". Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) The U.S. Postal Service designates "Littleton" as the default place name for addresses in the school's ZIP code; thus, the massacre was widely reported as having happened in the adjacent City of Littleton. The school actually lies a mile west of the Littleton city limit. - ^ "columbine high school shootings". history.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lamb, Gina (April 17, 2008). "Columbine High School". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Donaldson James, Susan (April 13, 2009). "Columbine Shootings 10 Years Later: Students, Teacher Still Haunted by Post-Traumatic Stress". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 27, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "10 years later, the real story behind Columbine". April 14, 2009.

- ^ Daryl Khan (February 10, 2014). "A Plot with a Scandal: A Closer Look at 'Kids for Cash' Documentary". Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

His message reflected what many experts say was the dominant one from law enforcement in the wake of the shootings in Columbine.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mark McPherson (March 20, 2015). "Kids for Cash Review". Cinema Paradiso Blog. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

After the events of the Columbine school massacre, Pennsylvanian Judge Ciavarella took a tough stance on juveniles with the zero tolerance policy.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brooks, David (April 24, 2004). "The Columbine Killers" Archived February 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ Toppo, Greg (April 14, 2009). "10 years later, the real story behind Columbine". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Janelle Brown (April 23, 1999). "Doom, Quake and mass murder". Salon. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lessons from Littleton (Part I)". Independent School. National Association of Independent Schools. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "JonKatz" (April 26, 1999). "Voices From The Hellmouth". Slashdot. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Columbine". The Final Report. Season 1. Episode 9.

- ^ Harris, Eric. "Columbine shooter Eric Harris's webpages". Acolumbinesite.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "District attorney releases Columbine gunman's juvenile records". The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. November 6, 2002. Archived from the original on December 8, 2002.

- ^ a b c Jerald Block. "Lessons From Columbine: Virtual and Real Rage" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 31, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. July 2007. - ^ Toppo, Greg (April 14, 2009). "10 years later, the real story behind Columbine". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Eric Harris diversion files" (PDF). Office of the District Attorney, First Judicial District, Jefferson and Gilpin Counties. p. 49. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cullen, Dave. "Eric's big lie". Columbine Online. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ Typed transcripts of Eric's journal Archived September 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, acolumbinesite.com.

- ^ "Columbine High School Shooting Details". Acolumbinesite.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cullen, Dave (2009). Columbine. Grand Central Publishing. pp. 214, 261. ISBN 978-0-446-54693-5.

- ^ "Analysis of journals and videos". Slate. April 20, 2004. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The lead investigator, Kate Battan, noted Archived January 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine that Harris went as far as monitoring the cafeteria prior to the attack in order to get an idea of when the busiest period was, and thus gain an estimate of the maximum number they could kill there. He reckoned on being able to kill about 450 students; 455 students were in the cafeteria when the bombs failed to detonate.

- ^ "Columbine killers planned to kill 500". BBC News. April 27, 1999. Archived from the original on May 15, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Columbine Basement Tapes". Acolumbinesite.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Quotes and transcripts from Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold's video tapes. - ^ a b "VPC – Where'd They Get Their Guns? – Columbine High School, Littleton, Colorado". www.vpc.org. Archived from the original on December 17, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "How they were equipped that day". www.cnn.com. Jefferson County Sheriff's Office. May 15, 2000. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2018 – via CNN.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bomb summary". www.cnn.com. Jefferson County Sheriff's Office. May 15, 2000. Archived from the original on February 18, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2018 – via CNN.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Dan Luzadder (October 3, 1999). "Loophole protects Columbine 'witness'". Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2001.

- ^ A Mother's Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of the Columbine Tragedy p. 84

- ^ "CNN - Gun provider pleads guilty in Columbine case - August 18, 1999". www.cnn.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Trench Coat Mafia & Associates". www.cnn.com. Jefferson County Sheriff's Office. May 15, 2000. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2018 – via CNN.