Islamic glass

Islamic glass is glass made in the Islamic world, especially in periods up to the 19th century. It built on pre-Islamic cultures in the Middle East, especially ancient Egyptian, Persian and Roman glass, and developed distinct styles, characterized by the introduction of new techniques and the reinterpreting of old traditions.[1] It came under European influence by the end of the Middle Ages, with imports of Venetian glass documented by the late 15th century.[2]

It rarely has religious content, other than inscriptions, although the mosque lamp was mainly used in religious contexts, to light mosques, but it uses the decorative styles of Islamic art from the same times and places. The makers were not necessarily Muslims themselves.

Though most glass was simple, and presumably cheap, finely formed and decorated pieces were expensive products, and often highly decorated, using several different techniques.[3] Muhammad disapproved of the use of tableware and drinking vessels made from precious metals, which remained usual for Christian elites in Europe and the Byzantine Empire. Islamic pottery and glass benefited from this, developing luxury styles in the absence of as much competition from ware in other materials, though some Islamic pottery reached the standards required for court entertainments.

The most important centres were Persia, Egypt, Mesopotamia and Syria through most of the period, with Turkey and India later joining them.

Roman and Sassanian influences

[edit]Islamic glass did not begin to develop a recognizable expression until the late 8th or early 9th century AD, despite Islam spreading across the Middle East and North Africa during the mid-7th century AD.[4] Despite bringing enormous religious and socio-political changes to the region, this event appears to have not drastically affected the day-to-day workings of craft industries, nor did it cause "extensive destruction or long-lasting disruption".[5] The Byzantine glass industry (Levant and Egypt) and Sassanian (Persia and Mesopotamia) glassmaking industries continued in much the same way they had for centuries, and glass was apparently still exported to the Byzantine Empire from the traditional centres, now under Islamic control.[6] Following the unification of the entire region, the interaction of ideas and techniques was facilitated, allowing for the fusion of these two separate traditions with new ideas, ultimately leading to the Islamic glass industry.[4]

Roman glassmaking traditions that are important in the Islamic period include the application of glass trails as a surface embellishment, while stylistic techniques adopted from the Sassanian Empire include various styles of glass cutting. This may have developed out of the long-standing hardstone carving traditions in Persia and Mesopotamia.[7][8] In regards to glass-making technology, tank furnaces used in the Levant to produce slabs of raw glass for export during the Classical Period were used during the Early Islamic Period in the same region until the 10th or 11th centuries AD.[9][10]

Technological change

[edit]

During the first centuries of Islamic rule, glassmakers in the Eastern Mediterranean continued to use the Roman recipe consisting of calcium-rich sand (providing the silica and lime) and mineral natron (soda component) from the Wādi el-Natrūn in Egypt, and examples of natron-based Islamic glass have been found in the Levant up to the late 9th century AD.[11] Much Roman glass had apparently begun as enormous slabs made in the Levant, then shipped to Europe for breaking and working. Archaeological evidence has shown that the use of natron ceased, and plant ash became the source of soda for all Islamic glass in the following centuries.[12][13][14][15] The reasons for this technological transition remain unclear, although it has been postulated that civil unrest in Egypt during the early 9th century AD led to a cut-off in the natron supply, thus forcing Islamic glassmakers to look for alternate soda sources.[16]

Evidence of experimentation with the basic glass recipe at Beth She'arim (modern Israel) during the early 9th century AD further supports this argument. A glass slab made from a tank mould from the site contained an excess amount of lime, and may be the result of mixing sand with plant ash.[17] Although the raw glass would have been unusable due to its composition, it does suggest that at this time, Islamic glassmakers in the Levant were combining aspects of Sassanian and Roman traditions in an effort to solve the problem created by the lack of access to mineral natron. The use of plant ash, specifically from halophytic (salt-loving) plants, which were plentiful in the Middle East due to the climate,[18] was well known in Persia and Mesopotamia. It undoubtedly would not take long for the glassmakers in the Near East to correct their manufacturing errors and begin using the plant ash-based recipe used further east.

Early Islamic glass: mid-7th to late 12th century AD

[edit]

The glass industry in the Early Islamic Period can initially be characterized as a continuation of older traditions, coinciding with the Umayyad Caliphate, the first Islamic dynasty (Israeli 2003, 319). Following the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate in 750 AD, the capital of the Islamic world was moved from Damascus in the Levant to Baghdad in Mesopotamia. This led to a cultural shift away from the influences of Classical traditions, and allowed for the development of an 'Islamic' expression.[19]

The production of glass during this period is concentrated in three main regions of the Islamic world. Firstly, the Eastern Mediterranean remained a centre of glass production, as it had been for centuries. Excavations at Qal'at Sem'an in northern Syria,[12] Tyre in Lebanon,[20] Beth She'arim and Bet Eli'ezer in Israel,[10] and at Fustat (Old Cairo) in Egypt[21] have all shown evidence for glass production, including numerous vessels, raw glass, and their associated furnaces. In Persia, a formerly Sassanian region, archaeological activity has located a number of sites with large deposits of Early Islamic Glass, including Nishapur, Siraf, and Susa.[22] Numerous kilns suggest Nishapur was an important production centre, and the identification of a local type of glass at Siraf suggests the same for that site.[23]

In Mesopotamia, excavations at Samarra, a temporary capital of the Abbasid Caliphate during the mid-9th century AD, produced a wide range of glass vessels, while work at al-Madā'in (former Ctesiphon) and Raqqa (on the Euphrates River in modern Syria) provide evidence for glass production in the region.[24][25] However, it is difficult to clearly identify the place in which a glass piece was manufactured without the presence of wastes (pieces broken and discarded in the process of making), which indicate that the location was a site of glassmaking. Furthermore, during the Abbasid caliphate, both glassmakers and their products moved throughout the empire, leading to dispersion of glassware and "universality of style", which further prevents the identification of a piece's birthplace. As the Seljuk empire arose from Seljuk generals conquering lands under the Abbasid flag only nominally, it is likely that glass technology, style, and trade might have continued similarly under the Seljuks as it did under the Abbasids.[26] Despite the increasing ability and style of Islamic glassmakers during this time, few pieces were signed or dated, making identification of a piece's location of origin unfortunately difficult. Glass pieces are typically dated by stylistic comparisons to other pieces from the era.[27]

The majority of the decorative traditions used in the Early Islamic Period concerned the manipulation of the glass itself, and included trail-application, carving, and mould-blowing.[19] As mentioned previously, glass-carving and trail application are a continuation of older techniques, the former associated with Sassanian glassmaking and the latter with Roman traditions. In relief cutting, a specialized form of glass-carving most often used on colourless and transparent glass, "the area surrounding the decorative elements was carved back to the ground, thus leaving the former in relief".[28]

Unlike relief cutting, trail application, or thread trailing, allowed decoration with hot glass.[29] The glassblower would manipulate molten glass while still malleable and create patterns, handles, or flanges. While cutting reached the height of its popularity from the 9th–11th centuries CE,[30] thread-trailing became more widely used during the 11th–12th centuries, when Seljuq glassmakers were considered at the height of their skill.[31]

Mould-blowing, based on Roman traditions from the 1st century CE, is another specialized technique that spread widely throughout the Islamic Mediterranean world during this period. Two distinct types of moulds are known archaeologically; a two-part mould made up of separate halves, and the 'dip' mould, whereby the viscous glass is placed entirely inside one mould.[32] The moulds were often made of bronze,[33] although there are examples of some being ceramic.[34] Moulds also often included a carved pattern; the finished piece would take on the shape and style of the mould (Carboni and Adamjee 2002). With these advances in glassmaking technology, artisans began to stylize and simplify their designs, emphasizing designs with "no foreground or background" and "plain but beautiful vessels".[29]

A final decorative technology that is a distinct marker of the Early Islamic Period is the use of painted lustre decoration. While some scholars see this as a purely Islamic invention originating in Fustat,[35] others place the origins of lustre decoration in Roman and Coptic Egypt during the centuries preceding the rise of Islam. Staining glass vessels with copper and silver pigments was known from around the 3rd century AD,[36] although true lustre technology probably began sometime between the 4th and 8th centuries AD.[37][38] Lustre painting on glass involves the application of copper and silver pigments, followed by a specific firing that allows for the ionic exchange of Ag+ and Cu+ with the glass, resulting in a metallic sheen fully bound to the vessel.[39] Regardless of its specific origins, lustre decoration was a key technology in glass production that continued to develop throughout the Early Islamic Period, and spread not only geographically, but also to other material industries in the form of lustreware glazed ceramics.[36]

-

8th-9th-century dish with lustre paint, 25.1 cm (9.8 in) wide

-

9th century bowl, millefiori, 5 5/8 in. (14.3 cm) wide

-

9th century beaker, Nishapur

-

Pattern-moulded flask, 10th or 11th century, 19.8 cm high

-

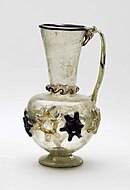

11th or 12th-century jug, blown, trail-decorated and tooled, 18.2 cm tall

Middle Islamic glass: late 12th to late 14th century AD

[edit]

This is the 'Golden Age' of Islamic glassmaking,[40] despite the fractious nature of the Islamic world. Persia and Mesopotamia (along with parts of Syria for some time) came under control of the Seljuq Turks, and later the Mongols, while in the Eastern Mediterranean, the Ayyubid and Mamluk Dynasties held sway. Furthermore, this period saw European interruptions into the Middle East due to the Crusades.[40][41] Glass production seemingly ceased to exist in Persia and Mesopotamia, and little is known about the reasons for this.[40] However, in the earlier part of this period, there is evidence for glass-making in Central Asia, for example at Kuva in modern Uzbekistan.[42] This tradition presumably ended with the Mongol invasions of the mid-13th century that destroyed other sites in the region.[43]

The glass-producing regions of Syria and Egypt continued their industries. It is for the materials excavated and produced at sites such as Samsat in southern Turkey,[44] Aleppo and Damascus in Syria,[45] Hebron in the Levant,[46] and Cairo[47][48] that this period is referred to as the 'Golden Age' of Islamic glass. The Middle Islamic Period is characterized by the perfection of various polychrome decorative traditions, the most important of which are marvering, enamelling, and gilding, while relief-carving and lustreware painting seemingly fell out of fashion.[49]

Marvering involves applying a continuous trail of opaque glass (in various colours such as white, red, yellow, or pale blue) around the body of a glass object. This trail may then be manipulated by pulling it, creating a characteristic 'wavy' pattern. The object was then rolled on a marver (a stone or iron slab) to work the trail into the glass vessel itself.[50] This technique, used on a variety of glass objects from bowls and bottles to chess pieces, was introduced around the late 12th century AD,[50] but is in fact a revival of a much older glass-working tradition that has its origins in the Late Bronze Age in Egypt.[51]

Gilding during this period involved applying small amounts of gold in suspension onto a glass body, followed by a low firing to fuse the two materials, and was adopted from Byzantine traditions.[52] Given that gilding individual color enamels have various chemical compositions, a process for firing each color separately was created by Mamluk glass makers. Recognizing that continuously firing and adding different color enamels could result in losing the shape of the original mold. They found that by lowering the temperature and using richer lead enamels it was able to adhere in a single firing.

[53] This technique was often combined with enamelling, the application of ground glass with a colourant, to traditional and new vessel forms, and represents the height of Islamic glassmaking.[54] Enamelled glass, a resurrection of older techniques, was first practiced in the Islamic world at Raqqa (Syria) during the late 12th century, but also spread to Cairo during Mamluk rule.[47]

[55] A study of various enamelled vessels, including beakers and mosque lamps, suggests that there are two subtle yet distinct firing practices, possibly representing two distinct production centres or glass-working traditions.[56] Due to its high demand, enamelled glass was exported throughout the Islamic world, Europe, and China during this period.[57] Enamelling of glass eventually ended in Syria and Egypt following disruption by various Mongol invasions from the 13th through to the 15th centuries AD.[58]

A feature of glass from the Middle Islamic Period is the increased interaction between the Middle East and Europe. The Crusades allowed for the European discovery of Islamic gilded and enamelled vessels. The 'Goblet of the Eight Princes' brought to France from the Levant is one of the earliest examples of this technique.[57] Furthermore, large amounts of raw plant ash were exported solely to Venice, fuelling that city's glass industries.[59] It was also in Venice that enamelling was resurrected following its decline in the Islamic world.[56]

-

Beaker with polo players, Syria, 1250–1300, with gold and enamel, found in Italy

-

Flask with applied decoration and turquoise trails, Persia, 12th or early 13th century

-

Enamelled and gilded bottle, 17 1/8 in. (43.5 cm) high, Egypt or Syria, late 13th century

-

Unique double-walled marvered bowl, 13th-14th century AD

-

Stacking beakers, with enamels and gilding, mid 13th century AD

Late Islamic glass: 15th to mid-19th century AD

[edit]

The Late Islamic Period is dominated by three main empires and areas of glass production; the Ottomans in Turkey, the Safavid (and later the Zand and Qajar) Dynasty in Persia, and the Mughals in northern India.[60] The most important over-riding characteristic of glass production in this period is the "direct influence of European glass" and, in particular, that of Venice, Bohemia (in the 18th century), and the Dutch.[61]

The production of high-quality fine glass essentially ended in Egypt, Syria, and Persia, and it was only in India during the 17th century that Islamic glass regained a high level of artistic expression following European influence.[61][62] The lack of court patronage for glassmaking, as the Ottoman Empire swallowed up most of the Middle East, and the high quality of European glass contributed to a decline in the industry; however, utilitarian glass was still being made in the traditional centres.[60]

Historical documents and accounts, such as the Surname-i Humayun, show the presence of glassmaking, and a glassmaker's guild, in Istanbul, as well as production at Beykoz on the coast of the Bosphorus, in the Ottoman Empire. The glass made at these centres was not of great quality and was highly influenced by Venetian and Bohemian styles and techniques.[63]

In Persia, evidence for glassmaking following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century does not reappear until the Safavid period (17th century). European travellers wrote accounts of glass factories in Shiraz, and it is thought that transplanted Italian craftsmen brought about this revival.[64] No significant decorative treatments or technical characteristics of glass were introduced or revived during this period in Persia. Bottle and jug forms with simple applied or ribbed decoration, made from coloured transparent glass, were common, and are linked to the Shirazi wine industry.[65] The elegant swan-neck bottle for serving wine, began in this period.

Glassmaking in India, on the other hand, saw a return under the Mughal Empire to the enamelling and gilding traditions from the Middle Islamic Period, as well as the glass–carving techniques used in Persia during the earliest centuries of the Islamic world.[66] Glass workshops and factories were initially found near the Mughal capital of Agra, Patna (eastern India), and in Gujarat province (western India), and by the 18th century had spread to other regions in western India.[67]

New forms were introduced using these older Islamic glass-working techniques, and of these, nargileh (water pipe) bases became the most dominant.[68] Square bottles based on Dutch forms, decorated with enamelling and gilding in Indian motifs, are another important expression in Mughal glassmaking, and were produced at Bhuj, Kutch, and in Gujarat.[69][70] Ethnographic study of current glass production in Jalesar shows fundamental similarities between this site and the Early Islamic tank furnaces found in the Levant, despite differences in the shape of the structures (round in India, rectangular at Bet She'arim), highlighting the technological continuity of the glass industry throughout the Islamic period.[71]

-

Safavid period bottles

-

Persian Swan-neck bottles, 1600–1800

-

Syrian mosque lamp, 19th-century

-

Persian bottle with portraits of Qajar rulers, 19th-century

-

Indian cobalt blue lamp, 1930s

Roles

[edit]

Glass filled a multitude of roles throughout the history of the Islamic world. As with other old glass, most archaeological finds are in fragments, and are plain, undecorated, and utilitarian.[72] Apart from a wide range of open shapes - cups, bowls and dishes, and closed bottle or vase shapes, particular designs include mosque lamps from the Middle Islamic Period, wine bottles from Safavid Persia, and nargileh bases from Mughal India. A variety of vessel forms used to hold a wide range of materials make up the bulk of glass objects (bowls, goblets, dishes, perfume bottles, etc.), and have seen the most attention from Islamic glass scholars.[73]

Some of the more distinct vessel functions from the Islamic period include inkwells (Israeli 2003, 345), qumqum or perfume sprinklers,[74][75][76] and vessels associated with Islamic science and medicine such as alembics, test-tubes, and cuppers.[77][78][79][80] Glass was also used for aesthetic purposes in the form of decorative figurines,[81][82] and for jewellery as bracelets (Carboni 1994; Spaer 1992) and beads.[83][46] The bracelets, in particular, may prove to be an important archaeological tool in the dating of Islamic sites.[84]

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Glass also filled various utilitarian roles, with evidence of use as windows,[85][86] and as coin weights. These are a distinctive form, very common in Egypt from the 8th century on, of small stamped disks used to check the weight of coins; the earliest known is dated 708–9.[87][88][89] The variety of functions filled by glass and the sheer bulk of the material found through excavation further highlights its significance as a distinct and highly developed material industry throughout the Islamic world.

Academic study

[edit]Islamic glass from this period has been given relatively little attention by scholars. One exception to this was the work carried out by Carl J. Lamm (1902–1987).[90] Lamm catalogued and classified the glass finds from important Islamic sites; for example Susa in Iran (Lamm 1931), and at Samarra in Iraq (Lamm 1928). One of the most important discoveries in the field of Islamic glass was a shipwreck dated to around 1036 AD on the Turkey coast at Serçe Liman. The recovered cargo included vessel fragments and glass cullet exported from Syria.[91] The significance of these finds lies in the information they can tell us about the production and distribution of Islamic glass.

Despite this, the majority of studies have concentrated on stylistic and decorative classification (Carboni 2001; Kröger 1995; Lamm 1928; Lamm 1931; Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001), and as such technological aspects of the industry, as well as undecorated vessels and objects, have often been overlooked within the field. This, in particular, is frustrating because the majority of glass finds during the Islamic period are undecorated and used for utilitarian purposes.[72]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 112

- ^ Whitehouse 1991, 45

- ^ Whitehouse 1991, 40-42

- ^ a b Israeli 2003, 319

- ^ Schick 1998, 75

- ^ Jenkins, Marylin, "Islamic Glass: A Brief History," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series Vol.44 No.2 (Autumn 1986), 6.

- ^ Carboni 2001, 15–17

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 115–122

- ^ Aldsworth et al. 2002, 65

- ^ a b Freestone 2006, 202

- ^ Whitehouse 2002, 193–195

- ^ a b Dussart et al. 2004

- ^ Freestone 2002

- ^ Freestone 2006

- ^ Whitehouse 2002

- ^ Whitehouse 2002, 194

- ^ Freestone and Gorin-Rosin 1999, 116

- ^ Barkoudah and Henderson 2006, 297–298

- ^ a b Israeli 2003, 320

- ^ Aldsworth et al. 2002

- ^ Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001

- ^ Kröger 1995, 1–6

- ^ Kröger 1995, 5-20

- ^ Freestone 2006, 203

- ^ Kröger 1995, 6–7

- ^ Ragab 2013

- ^ Lukens 2013, 199

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 116

- ^ a b Jenkins 2013, 28

- ^ Lukens 2013, 200

- ^ Lukens 2013, 207

- ^ Carboni 2001, 198

- ^ Carboni 2001, 197

- ^ von Folsach and Whitehouse 1993, 149

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 124

- ^ a b Carboni 2001, 51

- ^ Caiger-Smith 1985, 24

- ^ Pradell et al. 2008, 1201

- ^ Pradell et al. 2008, 1204

- ^ a b c Israeli 2003, 321

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 126

- ^ Ivanov 2003, 211–212

- ^ Anarbaev and Rehren 2009

- ^ Redford 1994

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 131

- ^ a b Spaer 1992, 46

- ^ a b Carboni 2001, 323

- ^ Israeli 2003, 231

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 126–130

- ^ a b Carboni 2001, 291

- ^ Tatton-Brown and Andrews 1991, 26

- ^ Ömür Bakırer, Scott Redford 2017

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 130

- ^ Carboni 2001, 323–325

- ^ Gudenrath 2006, 42

- ^ a b Gudenrath 2006, 47

- ^ a b Pinder-Wilson 1991, 135

- ^ Israeli 2003, 376

- ^ Jacoby 1993

- ^ a b Pinder-Wilson 1991, 136

- ^ a b Carboni 2001, 371

- ^ Markel 1991, 82–83

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 137

- ^ Carboni 2001, 374

- ^ Carboni 2001, 374–375

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 138

- ^ Markel 1991, 83

- ^ Markel 1991, 84

- ^ Carboni 2001, 389

- ^ Markel 1991, 87

- ^ Sode and Kock 2001

- ^ a b Carboni 2001, 139

- ^ Carboni 2001; Israeli 2003; Kröger 1995; Pinder-Wilson 1991; Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001

- ^ Carboni 2001, 350–351

- ^ Israeli 2003, 378-382

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 128–129

- ^ Carboni 2001, 375

- ^ Israeli 2003, 347

- ^ Kröger 1995, 186

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 2001, 56–60

- ^ Carboni 2001, 303

- ^ Israeli 2003, 383

- ^ Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001, 119–123

- ^ Spaer 1992, 54

- ^ Kröger 1995, 184

- ^ Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001, 61

- ^ Schick 1998, 95

- ^ Whitehouse 2002, 195

- ^ Whitehouse 1991, 40

- ^ Israeli 2003, 322

- ^ Pinder-Wilson 1991, 114

Sources

[edit]- Aldsworth, F., Haggarty, G., Jennings, S., Whitehouse, D. 2002. "Medieval Glassmaking at Tyre". Journal of Glass Studies 44, 49–66.

- Anarbaev, A. A. and Rehren, T. 2009. Unpublished Akhsiket Research Notes.

- Barkoudah, Y., Henderson, J. 2006. "Plant Ashes from Syria and the Manufacture of Ancient Glass: Ethnographic and Scientific Aspects". Journal of Glass Studies 48, 297–321.

- Caiger-Smith, A. 1985. Lustre Pottery: Technique, Tradition and Innovation in Islam and the Western World. New York: New Amsterdam Books.

- Carboni, S. 1994. "Glass Bracelets from the Mamluk Period in the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Journal of Glass Studies 36, 126–129.

- Carboni, S. 2001. Glass from Islamic Lands. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

- Carboni, S. and Adamjee, Q. 2002. "Glass with Mold-Blown Decoration from Islamic Lands". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

- Dussart, O., Velde, B., Blanc, P., Sodini, J. 2004. "Glass from Qal'at Sem'an (Northern Syria): The Reworking of Glass During the Transition from Roman to Islamic Compositions". Journal of Glass Studies 46, 67–83.

- Freestone, I. C. 2002. "Composition and Affinities of Glass from the Furnaces on the Island Site, Tyre". Journal of Glass Studies 44, 67–77.

- Freestone, I. C. 2006. "Glass Production in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic Period: A Geochemical Perspective". In: M. Maggetti and B. Messiga (eds.), Geomaterials in Cultural History. London: Geological Society of London, 201–216.

- Freestone, I. C., Gorin-Rosin, Y. 1999. "The Great Slab at Bet She'arim, Israel: An Early Islamic Glassmaking Experiment?" Journal of Glass Studies 41, 105–116.

- Gudenrath, W. 2006. "Enameled Glass Vessels, 1425 BCE – 1800: The Decorating Process". Journal of Glass Studies 48, 23–70.

- Israeli, Y. 2003. Ancient Glass in the Israel Museum: The Eliahu Dobkin Collection and Other Gifts. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum.

- Ivanov, G. 2003. Excavations at Kuva (Ferghana Valley, Uzbekistan). Iran 41, 205–216.

- Jacoby, D. 1993. Raw Materials for the Glass Industries of Venice and the Terraferma, about 1370 – about 1460. Journal of Glass Studies 35, 65–90.

- Jenkins, M. 1986. "Islamic Glass: A Brief History". Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. JSTOR, 1–52.

- Kröger, J. 1995. Nishapur: Glass of the Early Islamic Period. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Lamm, C. J. 1928. Das Glas von Samarra: Die Ausgrabungen von Samarra. Berlin: Reimer/Vohsen.

- Lamm, C. J. 1931. Les Verres Trouvés à Suse. Syria 12, 358–367.

- Lukens, M. G. 1965. "Medieval Islamic Glass". Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 23.6. JSTOR, 198–208.

- Markel, S. 1991. "Indian and 'Indianate' Glass Vessels in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art". Journal of Glass Studies 33, 82–92.

- Ömür Bakırer, Scott Redford. Journal of Glass Studies; 2017, Vol. 59, p171-191, 21p .Kubadabad Plate: A Study of Islamic Gilded and Enameled Glass.

- Pinder-Wilson, R. 1991. "The Islamic Lands and China". In: H. Tait (ed.), Five Thousand Years of Glass. London: British Museum Press, 112–143.

- Pradell, T., Molera, J., Smith, A. D., Tite, M. S. 2008. "The Invention of Lustre: Iraq 9th and 10th centuries AD". Journal of Archaeological Science 35, 1201–1215.

- Ragab, A. 2013. "Saladin (d. 1193) and Richard Lionheart (d. 1199): The Story of the Good Rivals". History of Science 113 Lecture. Science Center 469, Cambridge. Lecture.

- Redford, S. 1994. "Ayyubid Glass from Samsat, Turkey". Journal of Glass Studies 36, 81–91.

- Scanlon, G. T., Pinder-Wilson, R. 2001. Fustat Glass of the Early Islamic Period: Finds Excavated by the American Research Center in Egypt 1964–1980. London: Altajir World of Islam Trust.

- Schick, R. 1998. "Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: Palestine in the Early Islamic Period: Luxuriant Legacy". Near Eastern Archaeology 61/2, 74–108.

- Sode, T., Kock, J. 2001. Traditional Raw Glass Production in Northern India: The Final Stage of an ancient Technology. Journal of Glass Studies 43, 155–169.

- Spaer, M. 1992. "The Islamic Bracelets of Palestine: Preliminary Findings". Journal of Glass Studies 34, 44–62.

- Tatton-Brown, V., Andrews, C. 1991. "Before the Invention of Glassblowing". In: H. Tait (ed.), Five Thousand Years of Glass. London: British Museum Press, 21–61.

- von Folasch, K., Whitehouse, D. 1993. "Three Islamic Molds". Journal of Glass Studies 35, 149–153.

- Whitehouse, David. 2002. "The Transition from Natron to Plant Ash in the Levant". Journal of Glass Studies 44, 193–196.

- Whitehouse, David, in Battie, David and Cottle, Simon, eds., Sotheby's Concise Encyclopedia of Glass, 1991, Conran Octopus, ISBN 1850296545

Further reading

[edit]- Carboni, Stefano; Whitehouse, David (2001). Glass of the sultans. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870999869.