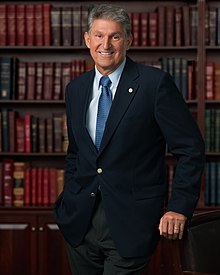

Joe Manchin

Joe Manchin | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from West Virginia | |

| Assumed office November 15, 2010 Serving with Shelley Moore Capito | |

| Preceded by | Carte Goodwin |

| Chair of the National Governors Association | |

| In office July 11, 2010 – November 15, 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Jim Douglas |

| Succeeded by | Christine Gregoire |

| 34th Governor of West Virginia | |

| In office January 17, 2005 – November 15, 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Bob Wise |

| Succeeded by | Earl Ray Tomblin |

| 27th Secretary of State of West Virginia | |

| In office January 15, 2001 – January 17, 2005 | |

| Governor | Bob Wise |

| Preceded by | Ken Hechler |

| Succeeded by | Betty Ireland |

| Member of the West Virginia Senate from the 13th district | |

| In office December 1, 1992 – December 1, 1996 | |

| Preceded by | Bill Sharpe |

| Succeeded by | Roman Prezioso |

| Member of the West Virginia Senate from the 14th district | |

| In office December 1, 1986 – December 1, 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Anthony Yanero |

| Succeeded by | Charles Felton |

| Member of the West Virginia House of Delegates from the 31st district | |

| In office December 1, 1982 – December 1, 1984 | |

| Preceded by | Clyde See |

| Succeeded by | Duane Southern |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joseph Manchin III August 24, 1947 Farmington, West Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, including Heather |

| Education | West Virginia University (BBA) |

| Signature | |

| Website | Senate website |

Joseph Manchin III (born August 24, 1947) is an American politician serving as the senior United States Senator from West Virginia, a seat he has held since 2010. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th governor of West Virginia from 2005 to 2010 and the 27th secretary of state of West Virginia from 2001 to 2005.

Manchin has been known throughout his career to be a moderate—or even conservative—Democrat, a fact which has allowed him to win elections in West Virginia even as the state shifted from one of the most heavily Democratic in the country to one of the most heavily Republican.[1] He won the 2004 West Virginia gubernatorial election by a large margin and was re-elected with an even larger margin in 2008; in both years, Republican presidential candidates captured the majority of West Virginia's votes. Manchin won the special election in 2010 to fill the seat vacated by Senator Robert Byrd when he died in office. Manchin was elected to a full term in 2012 with 60 percent of the vote, and was later reelected in 2018 by a much narrower margin. Manchin became the state's senior U.S. Senator when Jay Rockefeller retired in 2015.

As a member of Congress, Manchin is known for his bipartisanship, voting or working with Republicans on issues such as abortion and gun ownership. He opposed the energy policies of President Barack Obama, voted against the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010, voted for removing federal funding from Planned Parenthood in 2015, and voted to confirm most of Republican President Donald Trump's cabinet and judicial appointees. However, Manchin has repeatedly voted against attempts to repeal the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare), voted to preserve funding for Planned Parenthood in 2017, and voted against the 2017 Republican tax plan. Manchin has complained about the "toxic" lack of bipartisanship in Congress on almost every issue; "liberal activists argue he is too conservative for the Democratic Party, while Republicans argue he is too liberal for West Virginia."[2]

Early life and education

Manchin was born in 1947 in Farmington, West Virginia, a small coal mining town, the second of five children of Mary O. (née Gouzd) and John Manchin.[3][4] Manchin was derived from "Mancini". His father was of Italian descent and his maternal grandparents were Czechoslovak immigrants.[3][5]

His father owned a carpet and furniture store, and his grandfather, Joseph Manchin, owned a grocery store.[6] His father and his grandfather both served as Mayor of Farmington, West Virginia. His uncle, A.J. Manchin, was a member of the West Virginia House of Delegates and was elected as the state's Secretary of State and Treasurer.[7]

Manchin graduated from Farmington High School in 1965.[8] He entered West Virginia University on a football scholarship in 1965; however, an injury during practice ended his football career. Manchin graduated in 1970 with a degree in business administration[9] and went to work for his family's business, where he ran a carpet store.[3]

Manchin was a childhood friend of Alabama Crimson Tide football coach Nick Saban and they are still close friends to this day.[10]

Early political career

Manchin was elected to the West Virginia House of Delegates in 1982 at the age of 35 and was elected to the West Virginia Senate in 1986, where he served until 1996. He ran for governor in 1996, finishing second to Charlotte Pritt among a large group of candidates in the Democratic primary election. He later ran and was elected as Secretary of State of West Virginia in 2000.

Governor of West Virginia

Manchin announced his intention to challenge incumbent Democratic Governor, Bob Wise, in the 2004 Democratic primary election in May 2003. Wise decided not to seek re-election after a scandal, and Manchin won the Democratic primary and general election by large margins. His election marked the first time that two people of the same political party had followed one another in the West Virginia Governor's office since 1964.

Manchin was a member of the National Governors Association, the Southern Governors' Association, and the Democratic Governors Association. He was also chairman of the Southern States Energy Board, state's chair of the Appalachian Regional Commission and chairman of the Interstate Mining Compact Commission.

In July 2005, Massey Energy CEO Don Blankenship sued Manchin, alleging that Manchin had violated Blankenship's First Amendment rights by threatening increased government scrutiny of his coal operations in retaliation for Blankenship's political activities.[11] Blankenship had donated substantial funds into campaigns to defeat a proposed pension bond amendment and oppose the re-election of state Supreme Court Justice Warren McGraw,[12] and he fought against a proposed increase in the severance tax on extraction of mineral resources.[13] Soon after defeat of the pension bond amendment, the state Division of Environmental Protection (DEP) revoked a permit approval for controversial new silos near Marsh Fork Elementary School in Raleigh County. While area residents had complained for some time that the coal operation there endangered their children, Blankenship claimed that the DEP acted in response to his opposition to the bond amendment.[14]

During the 2006 Sago Mine disaster in early January 2006 in Upshur County, West Virginia, Manchin appeared to confirm incorrect reports that 12 miners had survived;[citation needed] in actuality only one survived. Manchin later acknowledged that an unintentional miscommunication had occurred with rescue teams in the mine.[citation needed] On February 1, 2006, he ordered a stop to all coal production in West Virginia, pending safety checks, after two more miners were killed in separate accidents.[15] Sixteen West Virginia coal miners died from mining accidents in early 2006. In November 2006, SurveyUSA ranked him as one of the most popular governors in the country with a 74 percent approval rating.[16]

Manchin easily won re-election to a second term as governor in 2008 against Republican Russ Weeks, capturing 69.77% percent of the vote and winning every county.[17]

U.S. Senate

Elections

2010

Due to the declining health of Senator Robert Byrd, speculation focused on what Manchin's response would be if Byrd died. The governor consistently refused to comment on the subject prior to Byrd's death, except for stating that he would not appoint himself to the position.[18] Byrd died on June 28, 2010,[19] and Manchin appointed Carte Goodwin, his 36-year-old legal adviser, on July 16.[20]

On July 20, 2010, Manchin announced he would seek the Senate seat.[21] In the Democratic primary on August 28, he defeated former Democratic Congressman and former West Virginia Secretary of State Ken Hechler.[22] In the general election, he then defeated Republican John Raese.

2012

Manchin chose to stand for reelection to a full term in 2012. According to the Democratic firm Public Policy Polling, early polling found Manchin heavily favored, leading Congresswoman Shelley Moore Capito 50–39, 2010 opponent John Raese 60–31, and Congressman David McKinley 57–28.[23] Manchin had not endorsed his party's candidate, President Barack Obama, for the 2012 presidential election, saying that he had "some real differences" with the presumptive nominees of both major parties, finding fault with Obama's economic and energy policies, and questioning Romney's understanding of the "challenges facing ordinary people."[24]

Manchin defeated Republican John Raese and Mountain Party candidate Bob Henry Baber with 60.49% of the total vote and won a full term in the U.S. Senate.[25]

2018

Manchin is running for re-election in 2018.[26] He was challenged in the Democratic primary by Paula Jean Swearengin. Swearengin is an activist and coal miner's daughter who is supported by former members of the Bernie Sanders campaign. Swearengin criticized Manchin for voting with the Republicans and supporting the policies of Donald Trump.[2][27]

On the Republican side, Manchin was challenged by West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey. In August 2017, Morrisey publicly asked Manchin to resign from the Senate Democratic leadership team. Manchin responded, "I don't give a shit, you understand?" to a Charleston Gazette-Mail reporter when asked about Morrisey's call. "I just don't give a shit. Don't care if I get elected, don't care if I get defeated, how about that?"[28]

Manchin narrowly defeated Mr. Morrisey.

Tenure

Manchin was sworn in by Vice President Joe Biden on November 15, 2010, succeeding interim Senator Carte Goodwin. Manchin named Democratic strategist Chris Kofinis to be his chief of staff. In 2015, Manchin announced that he would seek re-election to the Senate in 2018.[26]

Political positions

Joe Manchin is often considered to be a moderate[29][30]—or even conservative[29][31]—Democrat. Manchin describes himself as "fiscally responsible and socially compassionate"; CBS News has called him "a rifle-brandishing moderate" who is "about as centrist as a senator can get".[32] In February 2018, Congressional Quarterly published a study finding that Manchin had voted with President Trump's position 71% of the time.[33] As of June 2018, Five ThirtyEight, which tracks congressional votes, found that Manchin had voted with President Trump's position nearly 61% of the time.[34] In 2013, the National Journal gave Manchin an overall score of 55% conservative and 46% liberal.[35]

Abortion

Manchin identifies as "pro-life".[36] He has mixed ratings from both pro-choice and pro-life political action groups. In 2018, Planned Parenthood, which supports legal abortion, gave Manchin a lifetime grade of 57% while National Right to Life (NRLC), which opposes abortion, gave Manchin a 40% score; in 2016, the NRLC scored Manchin at 75% and NARAL Pro-Choice America gave him a 100% in the same year.[37] On August 3, 2015, he broke with Democratic leadership by voting in favor of a Republican-sponsored bill to terminate federal funding for Planned Parenthood, a nonprofit organization that provides reproductive health services, including abortions, both in the United States and globally. The organization had been accused of "illegal activity".[38] He has the endorsement of Democrats for Life of America, a pro-life Democratic PAC.[39]

On March 30, 2017, however, Manchin expressed support for abortion rights providers by voting against H.J.Res. 43.[40] A pending federal regulation would have prevented states from withholding money from abortion providers. H.J.Res. 43, which was signed by President Trump, would have nullified that regulation.[41] In April 2017, Manchin endorsed the continued funding of Planned Parenthood.[42][43][44] Also in 2017, Planned Parenthood gave Manchin a rating of 44%.[45] In January 2018, Manchin joined two other Democrats and the majority of Republicans by voting in favor of a bill to ban abortion after 20 weeks.[46] In June 2018, following the retirement of Supreme Court justice Anthony Kennedy, Manchin urged Trump not to appoint a judge who would seek to overturn Roe v. Wade and to instead choose a "centrist."[47]

Afghanistan

On June 21, 2011, Manchin delivered a speech on the Senate floor calling for a "substantial and responsible reduction in the United States' military presence in Afghanistan." He said, "We can no longer afford to rebuild Afghanistan and America. We must choose. And I choose America."[48]

Manchin introduced legislation to reduce the use of overseas service and security contractors. He successfully amended the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act to cap contractors' taxpayer funded salaries at $230,000.[49]

Bipartisanship

In his first year in office, Manchin met one-on-one with all of his 99 Senate colleagues in an effort to get to know them better.[50]

On December 13, 2010, Manchin participated in the launch of No Labels, a new, nonpartisan organization that is "committed to bringing all sides together to move the nation forward."[51] Manchin is a co-chair of No Labels.[52]

Manchin worked with Senator Pat Toomey (R-PA) to introduce legislation that would require a background check for most gun sales.[53]

Manchin opposed the January 2018 government shutdown.[54] The New York Times suggested that Manchin helped bring an end to the shutdown by threatening not to run for re-election unless his fellow Democrats put an end to it.[54]

Before his Senate swearing-in, rumors suggested that the Republican Party was courting Manchin to change parties.[55] Although the Republicans later suggested that Manchin was the source of the rumors,[56] they attempted to convince him again in 2014 after retaking control of the Senate.[57] He again rejected their overtures.[58] As the 2016 elections approached, reports speculated that Manchin would switch to the Republican Party if the Senate were in a 50-50 tie.[59] However, he later stated that he would stay with the Democratic Party for at least as long as he remained in the Senate.[60]

China

In July 2017, he urged Trump to block the sale of the Chicago Stock Exchange to Chinese investors, arguing that China's "rejection of fundamental free-market norms and property rights of private citizens makes me strongly doubt whether an Exchange operating under the direct control of a Chinese entity can be trusted to 'self-regulate' now and in the future." He also expressed concern "that the challenges plaguing the Chinese market – lack of transparency, currency manipulation, etc. – will bleed into the Chicago Stock Exchange and adversely impact financial markets across the country."[61]

Dodd-Frank

In 2018, Manchin was one of 17 Democrats to break with their party and vote with Republicans to ease the Dodd-Frank banking rules.[62]

Donald Trump

Manchin welcomed Donald Trump's presidency, saying: "He'll correct the trading policies, the imbalance in our trade policies, which are horrible." He supported the idea of Trump "calling companies to keep them from moving factories overseas."[29] Manchin voted for most of the Trump nominees. He was the only Democrat to vote in confirmation of Trump cabinet appointees Jeff Sessions[63] and Steven Mnuchin,[64] one of two Democrats who voted to confirm Scott Pruitt as EPA Administrator, and one of three who voted to confirm Rex Tillerson.[65]

In June 2017, Manchin voted to support President Trump's $350 billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia.[66]

In his 2018 campaign for Senate, Manchin announced that he supports Trump's proposal to construct a border wall along the southern border of the continental United States.[67] He also said that he regrets voting for Hillary Clinton and would be open to supporting Donald Trump for president in 2020.[68]

Drugs

In June 2011, Manchin joined Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) in seeking a crackdown on Bitcoin currency transactions, saying that they facilitated illegal drug trade transactions. "The transactions leave no traditional [bank transfer] money trail for investigators to follow, and leave it hard to prove a package recipient knew in advance what was in a shipment," using an "'anonymizing network' known as Tor."[69] One opinion website said the senators wanted "to disrupt [the] Silk Road drug website."[70]

In May 2012, in an effort to reduce prescription drug abuse, Manchin successfully proposed an amendment to the Food and Drug Administration re-authorization bill to reclassify hydrocodone as a Schedule II controlled substance.[71]

Energy and environment

Manchin sits on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee and supports a comprehensive, all-of-the-above energy approach that uses coal.[72]

Manchin's first bill in the Senate dealt with what he calls the EPA's overreach. After the EPA vetoed a previously-approved permit for the Spruce Mine in Logan County, West Virginia, Senator Manchin offered the "EPA Fair Play Act."[73] The bill would "clarify and confirm the authority of the Environment Protection Agency to deny or restrict the use of defined areas as disposal sites for the discharge of dredged or filled material."[74] Manchin said the bill would prevent the agency from "changing its rules on businesses after permits have already been granted."[75]

On October 6, 2010, Manchin directed a lawsuit aimed at overturning new federal rules concerning mountaintop removal mining. Filed by the state Department of Environmental Protection, the lawsuit "accuses U.S. EPA of overstepping its authority and asks the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia to throw out the federal agency's new guidelines for issuing Clean Water Act permits for coal mines." In order to qualify for the permits, mining companies need to prove their projects would not cause the concentration of pollutants in the local water to rise 5 times past the normal level. The New York Times reported that EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson said the new legislation would protect 95 percent of aquatic life by banning operators from dumping mine waste into streams.[76]

Manchin has received criticism from environmentalists due to his close family ties to the coal industry. He served as president of Energysystems in the late 1990s before becoming active in politics. On his financial disclosures in 2009 and 2010, his reported earnings from the company were $1,363,916 and $417,255 respectively.[77] Critics have stated his opposition to health regulations that would raise expenses for the industry are due to his stake in the industry; Jim Sconyers, chairman of West Virginia's Sierra Club chapter stated that "he's been nothing but a mouthpiece for the coal industry his whole public life."[77] However, opinions on the subject are mixed; The Charleston Gazette noted "the prospect that Manchin's $1.7 million-plus in recent Enersystems earnings might tilt him even more strongly pro-coal might seem remote, given the deep economic and cultural connections that the industry maintains in West Virginia."[78]

On November 14, 2011, Manchin chaired his first field hearing of that committee in Charleston, West Virginia, to focus on Marcellus Shale natural gas development and production. Manchin said, "We are literally sitting on top of tremendous potential with the Marcellus shale. We need to work together to chart a path forward in a safe and responsible way that lets us produce energy right here in America."[79]

Manchin supports building the Keystone XL Pipeline from Canada. Manchin has said, "It makes so much common sense that you want to buy [oil] off your friends and not your enemies." The pipeline would span over 2,000 miles across the United States.[80]

On November 9, 2011, Manchin introduced the "Fair Compliance Act" with Senator Dan Coats (R-IN). Their bill would "lengthen timelines and establish benchmarks for utilities to comply with two major Environmental Protection Agency air pollution rules. The legislation would extend the compliance deadline for the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, or CSAPR, by three years and the deadline for the Utility MACT rule by two years—setting both to January 1, 2017."[81]

Manchin introduced the "American Alternative Fuels Act" on May 10, 2011, with Senator John Barrasso (R-WY). The bill would remove restrictions on the development of alternative fuels, repeal part of the 2007 energy bill restricting the federal government from buying alternative fuels and encourage the development of algae-based fuels and synthetic natural gas. Regarding the bill, Manchin said, "Our unacceptably high gas prices are hurting not only West Virginians, but all Americans, and they underscore a critical need: the federal government needs to be a partner, not an obstacle, for businesses that can transform our domestic energy resources into gas."[82]

In 2011, Manchin was the only Democratic senator to support the proposed Energy Tax Prevention Act, which sought to prohibit the United States Environmental Protection Agency from regulating greenhouse gas.[83] He was also one of four Democratic senators to vote against the Stream Protection Rule.[84] In 2012 Manchin supported a GOP effort to "scuttle Environmental Protection Agency regulations that mandate cuts in mercury pollution and other toxic emissions from coal-fired power plants", while West Virginia's other senator, Jay Rockefeller, did not.[85]

Manchin criticized Obama's environmental regulations as a "war on coal" and demanded what he described as a proper balance between the needs of the environment and the coal business.[86] The Los Angeles Times has noted that while professing environmental concerns, he has consistently stood up for coal, saying "no one is going to stop using fossil [fuels] for a long time." He "does not deny the existence of man-made climate change," wrote the Los Angeles Times, but "is reluctant to curtail it."[87] In February 2017, he was one of only two Democratic senators to vote to confirm Scott Pruitt as Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency.[88] In June 2017, Manchin supported President Trump's withdrawal from the Paris climate accord, saying he supported "a cleaner energy future" but that the Paris deal failed to strike "a balance between our environment and the economy."[89]

Federal budget

Manchin has co-sponsored balanced budget amendments put forth by Senators Mike Lee (R-UT),[90] Richard Shelby (R-AL), and Mark Udall (D-CO).[91] He has also voted against raising the federal debt ceiling.[92]

Manchin has expressed strong opposition to entitlement reform, describing Mitch McConnell's comments in October 2018 on the need to reform entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare as "absolutely ridiculous."[93]

Guns

In 2012 Manchin's candidacy was endorsed by the National Rifle Association (NRA), which gave him an "A" rating.[94] Following the Sandy Hook shooting, Manchin partnered with Republican senator Pat Toomey to introduce a bill that would have strengthened background checks on gun sales. The Manchin-Toomey bill was defeated on April 17, 2013, by a vote of 54–46; 60 votes would have been required to pass it.[53] Despite the fact that the bill did not pass, the NRA targeted Manchin in an attack ad.[95][96][97]

Manchin was criticized in 2013 for agreeing to an interview with The Journal in Martinsburg, West Virginia, but demanding that he not be asked any questions about gun control or the Second Amendment.[98]

In 2016, referring to the difficulty of keeping guns out of the hands of potential terrorists, Manchin said, "due process is what's killing us right now." This comment drew the criticism of both the NRA and the Cato Institute, which accused Manchin of attacking a fundamental constitutional principle. "With all respect," commented Ilya Shapiro of Cato, "due process is the essential basis of America."[99][100]

Health care

In 2010, Manchin called for "repairs" of the Affordable Care Act and repeal of the "bad parts of Obamacare".[101][102] On January 14, 2017, Manchin expressed concern at the strict party-line vote on repealing Obamacare and said he could not, in good conscience, vote to repeal without a new plan in place. He added, however, that he was willing to work with Trump and the GOP to formulate a replacement.[103] In June 2017, Manchin and Bob Casey Jr. of Pennsylvania warned that repealing Obamacare would worsen the opioid crisis.[104] In July 2017, he said that he was one of about ten senators from both parties who had been "working together behind the scenes" to formulate a new health-care program, but that there was otherwise insufficient bipartisanship on the issue.[105]

During 2016-17, Manchin read to the Senate several letters from constituents about loved ones' deaths from opioids and urged his colleagues to act to prevent more deaths. Manchin took "an unusual proposal" to President Trump to address the crisis and called for a "war on drugs" that involves not punishment but treatment. He proposed the LifeBOAT Act, which would fund treatment. He also opposes marijuana legalization.[106][107] In January 2018, Manchin was one of six Democrats who broke with their party to vote to confirm Trump's nominee for Health Secretary, Alex Azar.[108]

In his 2018 re-election campaign, Manchin emphasized his support for Obamacare, running an ad where he shot holes in a lawsuit that sought to repeal the Affordable Care Act.[102]

Immigration

Manchin is opposed to the DREAM Act, and was absent from a 2010 vote on the bill.[109] Manchin supports the construction of a wall along the southern border of the United States.[110][111] Manchin voted against the McCain-Coons proposal to create a pathway to citizenship for some undocumented immigrants without funding for a border wall and he voted against a comprehensive immigration bill proposed by Susan Collins which gave a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers as well as funding for border security; he voted 'yes' to withholding funding for 'sanctuary cities' and he voted in support of President Trump's proposal to give a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers, build a border wall, and reduce legal immigration.[112][113]

Manchin has mixed ratings from political action committees opposed to illegal immigration; NumbersUSA, which seeks to reduce illegal and legal immigration, gave Manchin a 55% rating and the Federation for American Immigration Reform, which also seeks to reduce legal immigration, gave him a 25% rating.[114]

LGBT rights

On December 9, 2010, Manchin was the sole Democrat to vote against cloture for the 2011 National Defense Authorization Act, which contained a provision to repeal Don't Ask, Don't Tell. In an interview with The Associated Press, Manchin cited the advice of retired military chaplains as a basis for his decision to vote against repeal.[115] He also indicated he wanted more time to "hear the full range of viewpoints from the citizens of West Virginia."[116] A day later, he was publicly criticized at a gay rights rally for his position on the bill.[117]

As of 2013, he was one of three Democratic senators who still opposed same-sex marriage, and as of 2015, he was the only Democratic senator who opposed gay marriage.[118] The Guardian attributed his opposition to "ideology, rather than electoral concerns," noting his votes against the repeal of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" and for the Defense of Marriage Act.[119] The Human Rights Campaign, a PAC which supports same-sex marriage and other LGBT rights, gave Manchin an 85% scoring in line with their positions in 2016, a 0% in 2014, and a 65% in 2012.[37]

Senior citizens

To help locate missing senior citizens, Manchin introduced the Silver Alert Act in July 2011 to create a nationwide network for locating missing adults and senior citizens modeled after the AMBER Alert.[120] Manchin also sponsored the National Yellow Dot Act to create a voluntary program that would alert emergency services personnel responding to car accidents of the availability of personal and medical information on the car's owner.[121]

Manchin said in 2014 that he "would change Social Security completely. I would do it on an inflationary basis, as far as paying into payroll taxes, and change that, to keep us stabilized as far as cash flow. I'd do COLAs—I'd talk about COLA for 250 percent of poverty guidelines." Asked whether this meant he would "cut benefits to old people," Manchin said that "a rich old person...won't get the COLAs." He asked: "Do you want chained CPI? I can live with either one."[122]

Supreme Court nominations

Manchin was the first Democrat to say he would vote for Trump's first nominee for the Supreme Court, Neil Gorsuch. Manchin said, "During his time on the bench, Judge Gorsuch has received praise from his colleagues who have been appointed by both Democrats and Republicans. He has been consistently rated as a well-qualified jurist, the highest rating a jurist can receive, and I have found him to be an honest and thoughtful man."[123]

He was the first Democrat to announce that he would meet with Trump's second Supreme Court nominee, Brett Kavanaugh.[124] Manchin was the only Democrat to vote 'yes' on the cloture of Kavanaugh's nomination, advancing the motion to a final vote.[125] On October 5, 2018, he announced he would vote to confirm Kavanaugh.[126] On October 6, Manchin was the only Democrat to vote to confirm Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court in a 50-48 count.[127]

Taxes

According to Politico, Manchin sees Trump's Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 as "a closed process" that "makes little impact in the paychecks of the people in his state." At the same time, he posited the bill contains "some good things...Initially people will benefit", although ultimately voting against it. In turn, NRSC spokesman Bob Salera stated that he had "turned his back and voted with Washington Democrats."[128][129]

Terrorism

In June 2017, he was one of five Democrats who, by voting against a Senate resolution disapproving of arms sales to Saudi Arabia, ensured its failure. Potential primary opponent Paula Jean Swearengin charged that because of Manchin's vote, weapons sold to the Saudis "could possibly end up in the hands of terrorists."[130]

Committee assignments

- Committee on Appropriations

- Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies

- Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

- Subcommittee on Homeland Security

- Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies

- Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies

- Committee on Energy and Natural Resources

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence

- Senate Veterans' Affairs Committee

Personal life

Manchin is a member of the National Rifle Association and a licensed pilot.[3][131][132] In 1967, he married Gayle Conelly. Together they have three children: Heather, Joseph IV, and Brooke.[3]

In 2006 and 2010 Manchin delivered commencement addresses at Wheeling Jesuit University and at Davis & Elkins College, receiving honorary degrees from both institutions.

In December 2012, Manchin voiced his displeasure with MTV's new reality show Buckwild, set in his home state's capital Charleston, and asked the network's president to cancel the show, which, he argued, depicted West Virginia in a negative, unrealistic fashion.[133] The show ended after its first season.[134]

Controversies

Heather Bresch

West Virginia University (WVU) awarded Manchin's daughter, Heather Bresch, an MBA in 2007, the year she became COO at Mylan Inc., the third largest generic pharmaceutical manufacturer in the U.S. with headquarters in Morgantown, adjacent to the WVU campus. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that in order to justify this degree, university officials had added courses to her transcript that she had never taken and altered grades she had received. The ensuing controversy resulted in the rescinding of her MBA and the resignation of the university president, Mike Garrison, a Manchin family friend, and Garrison's legal counsel and the Dean of the Business School. A panel was convened to fully investigate the measure.[135] When the MBA controversy erupted, according to The Huntington News, Manchin "act[ed] as though he and his wife, Gayle, were somehow the victims of this hoax that almost cost WVU its academic credibility." According to the Huntington News, "the Manchins were seen as people willing to destroy [the university's] reputation rather than admit a mistake."[136]

Noting in a December 2011 editorial that the magazine Esquire had promoted Heather Bresch as an "American hero" owing to her support for a pharma safety law, the Huntington News pointed out that the law also protected U.S. pharma firms like Mylan and suggested that the article was a "public makeover" engineered by "the Manchin public relations machine." It also said that Mylan "must have the only corporate Board of Directors in the country that doesn't care about one of their top execs being proven to have a phony MBA degree."[137]

Despite Manchin's call for a war on drugs, particularly opioids, and his charge that "Big Pharma" had "targeted" his state, Manchin's daughter, as noted, is the CEO of Mylan, a pharmaceutical firm that produces opioids, and Manchin himself accepted "nearly $180,000 in donations from pharmaceutical companies between 2011 and 2016."[138] In August 2016, Fortune Magazine and the Washington Post ran a total of three articles about the fact that the "CEO of the company at the center of the EpiPen controversy" was Manchin's daughter. The articles noted that skyrocketing EpiPen costs were "the next big flash point in the national debate over skyrocketing prescription drug prices," that Bresch had originally gotten her Mylan job through her father, and that her career had "risen along with her father's, a fact that has not gone unnoticed by her critics." A particular point of controversy was the fact that Bresch had transferred Mylan's official headquarters to the Netherlands, a tax dodge maneuver known as tax inversion.[139]

Family lawsuit

In a lawsuit filed in July 2014, Dr. John Manchin II, one of Joe Manchin's brothers, sued Joe Manchin and his other brother, Roch Manchin, over a $1.7 million loan. The lawsuit alleged that Joe and Roch Manchin borrowed the money to keep the doors open at the family-owned carpet business run by Roch, that no part of the loan had yet been repaid, and that the defendants had taken other measures to evade compensating John Manchin II for non-payment.[140] Dr. Manchin withdrew the suit on June 30, 2015.[141]

Manchin's coal interests

In July 2011, The New York Times ran a long article headlined "Sen. Manchin Maintains Lucrative Ties to Family-Owned Coal Company." Manchin's 2009 and 2010 financial disclosures included major earnings from Enersystems Inc., "a coal brokerage that he helped run before his political star rose." Many senators earn business income, but Manchin is rare in that "he derives income from an industry while acting as one of its biggest boosters."[77]

Skipping votes and convention

On December 18, 2010, Manchin skipped the vote to repeal Don't Ask, Don't Tell and the vote on the DREAM Act, regarding immigration. The National Republican Senatorial Committee criticized Manchin for attending a family Christmas gathering instead of voting on these important issues. "For a Senator who has only been on the job a few weeks," commented the NRSC, "Manchin's absence today, and the apparent lack of seriousness with which he takes the job he was elected to do, speaks volumes."[142] The Washington Post reported that he was the only Senate Democrat to miss these votes "on two of his party's signature pieces of legislation."[143] Later, in 2012, Manchin also skipped the Democratic National Convention, saying he planned "to spend this fall focused on the people of West Virginia."[144]

Electoral history

| West Virginia 31st district House of Delegates Democratic primary election, 1982 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 7,687 | 21.2 |

| Democratic | Cody Starcher | 6,844 | 18.8 |

| Democratic | William Stewart | 6,391 | 17.6 |

| Democratic | Nick Fantasia | 5,072 | 14.0 |

| Democratic | Samuel Morasco | 4,250 | 11.7 |

| Democratic | Donald Smith | 3,276 | 9.0 |

| Democratic | Lonnie Bray | 2,819 | 7.8 |

| West Virginia 31st district House of Delegates election, 1982 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 16,160 | 16.7 |

| Democratic | Cody Starcher | 16,110 | 16.6 |

| Democratic | William Stewart | 15,090 | 15.6 |

| Republican | Paul Prunty | 14,620 | 15.1 |

| Republican | Benjamin Springston | 12,166 | 12.6 |

| Democratic | Samuel Morasco | 11,741 | 12.1 |

| Republican | Edgar Williams III | 5,702 | 5.9 |

| Republican | Lyman Clark | 5,270 | 5.4 |

| West Virginia 14th district State Senate Democratic primary election, 1986 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 10,691 | 56.5 |

| Democratic | Jack May | 8,220 | 43.5 |

| West Virginia 14th district state senate election, 1986 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 17,284 | 65.9 |

| Republican | Lyman Clark | 8,955 | 34.1 |

| West Virginia 14th district State Senate Democratic primary election, 1988 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 13,932 | 63.6 |

| Democratic | Anthony Yanero | 7,981 | 36.4 |

| West Virginia 14th district state senate election, 1988 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 29,792 | 100.0 |

| West Virginia 13th district state senate election, 1992 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 33,218 | 100.0 |

| West Virginia gubernatorial Democratic primary election, 1996 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Charlotte Pritt | 130,107 | 39.5 |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 107,124 | 32.6 |

| Democratic | Jim Lees | 64,100 | 19.5 |

| Democratic | Larrie Bailey | 15,733 | 4.8 |

| Democratic | Bob Myers | 3,038 | 0.9 |

| Democratic | Lyle Sattes | 2,931 | 0.9 |

| Democratic | Bob Henry Baber | 1,456 | 0.4 |

| Democratic | Louis "Lou" Davis | 1,351 | 0.4 |

| Democratic | Richard Koon | 1,154 | 0.4 |

| Democratic | Frankie Rocchetti | 1,330 | 0.4 |

| Democratic | Fred Schell | 733 | 0.2 |

| West Virginia Secretary of State Democratic primary election, 2000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 141,839 | 51.1 |

| Democratic | Charlotte Pritt | 80,148 | 28.9 |

| Democratic | Mike Oliverio | 35,424 | 12.8 |

| Democratic | Bobby Nelson | 20,259 | 7.3 |

| West Virginia Secretary of State election, 2000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 478,489 | 89.4 |

| Libertarian | Poochie Myers | 56,477 | 10.6 |

| West Virginia gubernatorial Democratic primary election, 2004 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 149,362 | 52.7 |

| Democratic | Lloyd Jackson | 77,052 | 27.2 |

| Democratic | Jim Lees | 40,161 | 14.2 |

| Democratic | Lacy Wright Jr. | 4,963 | 1.8 |

| Democratic | Jerry Baker | 3,009 | 1.1 |

| Democratic | James Baughman | 2,999 | 1.1 |

| Democratic | Phillip "Icky" Frye | 2,892 | 1.0 |

| Democratic | Louis "Lou" Davis | 2,824 | 1.0 |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 472,758 | 63.5 | |

| Republican | Monty Warner | 253,131 | 33.6 | |

| Mountain | Jesse Johnson | 18,430 | 2 | |

| West Virginia gubernatorial Democratic primary election, 2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 264,775 | 74.62 |

| Democratic | Melvin Ray Kessler | 90,074 | 25.38 |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 493,246 | 69.77 | |

| Republican | Russ Weeks | 181,908 | 25.73 | |

| Mountain | Jesse Johnson | 31,515 | 4.46 | |

| United States Senate special Democratic primary election, 2010 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 68,287 | 73.06 |

| Democratic | Ken Hechler | 16,267 | 17.27 |

| Democratic | Sheirl Lee Fletcher | 9,108 | 9.67 |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 280,771 | 53.5 | |

| Republican | John Raese | 227,960 | 43.4 | |

| Mountain | Jesse Johnson | 10,048 | 1.9 | |

| Constitution | Jeff Becker | 6,366 | 1.2 | |

| United States Senate Democratic primary election, 2012 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 163,891 | 79.94 |

| Democratic | Sheirl Fletcher | 41,118 | 20.06 |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 391,669 | 60.49 | |

| Republican | John Raese | 236,620 | 36.54 | |

| Mountain | Bob Henry Baber | 19,232 | 2.97 | |

| United States Senate Democratic primary election, 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 111,589 | 69.79 |

| Democratic | Paula Jean Swearengin | 48.302 | 30.21 |

References

- ^ Gonyea, Don (October 24, 2015). "West Virginia Tells The Story Of America's Shifting Political Climate". NPR.

- ^ a b Foran, Clare (May 9, 2017). "West Virginia's Conservative Democrat Gets a Primary Challenger". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Burton, Danielle (August 1, 2008). "10 Things You Didn't Know About West Virginia Gov. Joe Manchin". US News & World Report. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ^ "Manchin's mom was a tomboy in her youth". The Register-Herald. December 26, 2009. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ Baxter, Anna (August 26, 2008). "Day 2: Democratic National Convention". WSAZ-TV. Archived from the original on August 31, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A Day with Joe Manchin". The Shepherdstown Observer. August 7, 2010. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gov. Joe Manchin (D)". National Journal. June 22, 2005. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fournier, Eddie (November 2008). "Joe Manchin III". Our States: West Virginia. EBSCO Publishing. pp. 1–3. ISBN 1-4298-1207-9.

- ^ "Manchin, Joe, III, (1947-)". Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ "US Senator vacationed with childhood friend Nick Saban but can't cheer for him Saturday". AL.com. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ Bundy, Jennifer (July 27, 2005). "Massey CEO sues W.Va. governor in federal court". The Herald-Dispatch. Retrieved May 26, 2012 – via Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition.

- ^ Newhouse, Eric. "West Virginia: The story behind the score". StateIntegrity.org. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The WV Coal Equation: Living With Past Peak Production". CalhounPowerline.com. April 17, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ Shnayerson, Michael (November 20, 2006). "The Rape of Appalachia". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ "W.Va. governor asks for coal production halt after two deaths". San Mateo Daily Journal. February 2, 2006. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "Approval Ratings For All 50 Governors". SurveyUSA. November 20, 2006.

- ^ Lilly, Jessica (November 5, 2008). "Gov. Manchin wins second term". West Virginia Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Joe Manchin stated that he would not select himself for the US senate position should Robert Byrd be unable to serve a full term on YouTube[dead link]

- ^ Lerer, Lisa (June 28, 2010). "Robert Byrd, Longest-Serving U.S. Senator, Dies at 92". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ CNN Wire Staff (July 16, 2010). "West Virginia governor to name Byrd replacement". CNN. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Blake, Aaron (July 20, 2010). "W.Va. Gov. Joe Manchin launches Senate campaign; Capitol on deck". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ "Manchin & Raese Nominees for Byrd's Senate Seat". WSAZ-TV. Associated Press. August 30, 2010. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Manchin leads Capito, Raese, McKinley for 2012 re-election" (PDF). Public Policy Polling. January 25, 2011.

- ^ "Dem Senator Doesn't Know If He Will Vote For Obama". CBS DC. April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b "Statewide Results : General Election - November 6, 2012". West Virginia Secretary of State — Online Data Services. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Cheney, Kyle (April 19, 2015). "Joe Manchin won't run for West Virginia governor". Politico. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Hains, Tim (May 9, 2017). "'Justice Democrat' Coal Miner's Daughter Paula Swearingen Announces Primary Challenge Against West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin". RealClearPolitics. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ Dickerson, Chris (August 7, 2017). "Manchin says he 'doesn't give a sh-t' about Morrisey's demand". West Virginia Record. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c Kruse, Michael; Everett, Burgess (March–April 2017). "Manchin in the Middle". Politico. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ "Democratic senator criticizes Pelosi's immigration comment". Reuters. January 28, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ Foran, Clare (May 9, 2017). "Will Liberals Force a Conservative Democrat Out of the Senate?". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ Alemany, Jacqueline (July 24, 2014). "Is there room for Joe Manchin among Democrats in 2016?". CBS News. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ "Study finds 62% of Donnelly's votes support Trump's positions". The Journal Gazette. February 14, 2018. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ Bycoffe, Aaron (January 30, 2017). "Tracking Joe Manchin III In The Age Of Trump". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ Cohen, Richard E.; Barnes, James A.; Holland, Keating; Cook, Charlie; Barone, Michael; Jacobson, Louis; Peck, Louis (2016). The Almanac of American Politics: Members of Congress and Governors: their profiles and election results, their states and districts. Bethesda, Maryland: Columbia Books & Information Services. ISBN 978-1-93851-831-7. OCLC 927103599.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Gonzalez, Jose, R. (April 22, 2014). "Pro-Life Democrats, Squeezed by a Partisan Issue". Real Clear Politics. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Joe Manchin III's Ratings and Endorsements". VoteSmart.org. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Snell, Kelsey (August 3, 2015). "Joe Manchin and Joe Donnelly vote to defund Planned Parenthood". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Davis, Susan (July 3, 2018). "5 Senators Who Will Likely Decide The Next Supreme Court Justice". KUNC. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Dinan, Stephen (April 13, 2017). "Trump Gives States Power to Cut off Planned Parenthood Money". The Washington Times. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Dinan, Stephen; Richardson, Bradford (March 30, 2017). "Senate Passes Bill to Let States Strip Funding from Planned Parenthood". The Washington Times. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ Schor, Elana (May 14, 2017). "Abortion Politics Hound Senators from Both Parties". Politico. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Swan, Jonathan (May 8, 2017). "Joe Manchin's Tightrope on Planned Parenthood". Axios. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Ross, Chuck (May 9, 2017). "Photos Show Sen. Joe Manchin Is A Planned Parenthood Poseur". The Daily Caller. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "Congressional Scorecard". Planned Parenthood Action. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ Collins, Eliza (January 30, 2018). "Senate blocks 20-week abortion ban bill GOP pushed to get Democrats on record". USA Today. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Carney, Jordain (June 29, 2018). "Manchin warns Trump against picking court nominee who will overturn Roe v. Wade". The Hill. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ "Manchin: It's Time to Rebuild America, Not Afghanistan". WHSV-TV. June 21, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ Nyden, Paul J. (March 9, 2012). "Manchin questions military officials on contractors". Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Higgins, Carra (November 16, 2011). "Manchin marks a year in Senate". The Inter-Mountain. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sen. Manchin joins group aiming to reduce partisanship". West Virginia Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kurtz, Judy (September 17, 2014). "Biden, Huntsman praise bipartisanship at No Labels". The Hill. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Korte, Gregory; Camia, Catalina (April 17, 2013). "Senate rejects gun background checks". USA Today. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ a b Martin, Jonathan (January 23, 2018). "Manchin Will Seek Re-election but Sends Democrats a Stern Warning". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ Stirewalt, Chris (November 8, 2010). "Today's Power Play: GOP Sweetens its Offer to Manchin". Fox News. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Drucker, David (November 10, 2010). "GOP Suggests Manchin Source of Own Party-Switch Rumors". Roll Call. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Bolton, Alexander (November 5, 2014). "McConnell expected to woo King, Manchin". The Hill. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ O'Keefe, Ed (November 5, 2014). "Joe Manchin on election results: 'This is a real ass-whuppin'". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin reportedly hasn't ruled out switching parties in a tied Senate". The Week. November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ Everett, Burgess (November 8, 2016). "Source: Manchin to remain a Democrat". Politico. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ Louis, Brian (October 13, 2017). "Two Chinese bidders for Chicago Exchange are said to drop out". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Schoen, Jacob; Pramuk, John W. (March 15, 2018). "Why 17 Democrats voted with Republicans to ease bank rules". CNBC. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ McBride, Jessica (February 8, 2017). "Source: Joe Manchin: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy.com. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "How Senators Voted on Steven Mnuchin for Treasury Secretary". The New York Times. February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Andrews, Wilson (May 11, 2017). Manchin was the only Democratic senator to vote in favor of the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. "Source: How Each Senator Voted on Trump's Cabinet and Administration Nominees". The New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Carney, Jordain (June 13, 2017). "Senate rejects effort to block Saudi arms sale". The Hill.

- ^ Kapur, Sahil (June 14, 2018). "Manchin Touts Border Wall Vote in Bid for Trump Fans". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Shaw, Adam (June 6, 2018). "Manchin says he regrets Clinton support, could back Trump in 2020". Fox News. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Wolf, Brett (June 8, 2011). "Senators seek crackdown on Bitcoin currency". Reuters. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Senators Charles Schumer, Joe Manchin discuss targetting bitcoin exchanges in convoluted scheme to disrupt Silk Road drug website". Hammer of Truth. June 9, 2011. Archived from the original on May 13, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Senators approve Manchin amendment to reclassify hydrocodone drugs". Charleston Gazette-Mail. May 23, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Manchin 'Energy belongs to all of us - regardless of party labels'". Logan Banner. [dead link]

- ^ "Manchin touts EPA bill in maiden Senate speech". Charleston Daily Mail. February 3, 2011. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "S. 272 (is) - EPA Fair Play Act". U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Hicks, Martin (February 3, 2011). "Senator Manchin Introduces EPA Fair Play Act Of 2011". WCHS-TV. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reis, Patrick (October 6, 2010). "W.Va. Sues Obama, EPA Over Mining Coal Regulations". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c Quinones, Manuel; Schor, Elana (July 26, 2011). "Sen. Manchin Maintains Lucrative Ties to Family-Owned Coal Company". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Ward Jr., Ken (July 26, 2011). "Sen. Manchin's coal ties under scrutiny". The Charleston Gazette. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Senator Manchin Leads Field Hearing On Marcellus Shale". West Virginia Metro News. November 14, 2011.

- ^ "Manchin Speaks Out About 'Political Football' Pipeline Treatment". WVNS-TV. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ Kasey, Pam. "Manchin Co-Sponsors Bill to Delay EPA Air Pollution Rules". The State Journal. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Manchin introduces alternative fuels bill". The Parkersburg News and Sentinel. May 11, 2011.

- ^ Broder, John M. (March 16, 2011). "House Panel Votes to Limit E.P.A. Power". The New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ "On the Joint Resolution (H.J.Res. 38 )". United States Senate: U.S. Roll Call Votes. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ Geman, Ben; Strauss, Daniel (June 20, 2012). "Bid to kill EPA coal plant regulations thwarted in Senate". The Hill. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ "Trump Seeks an Ally, or At Least an Ear, in West Virginia Democrat". Fortune. February 4, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Banerjee, Neela. "2 Senate Democrats explore how to protect coal jobs and the environment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "How Senators Voted on Scott Pruitt for E.P.A. Administrator". The New York Times. February 17, 2017. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Beavers, Olivia (June 1, 2017). "Dem senator: Paris accord did not 'balance' environment, economy". The Hill. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Nyden, Paul J. (March 2, 2011). "Manchin questions U.S. role in Afghanistan". Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nyden, Paul J. (April 26, 2011). "Manchin launches 'Commonsense' tour". Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on October 28, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Rockefeller, Manchin cast opposite votes on debt ceiling". Charleston Gazette. January 27, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "'Campaign gold': McConnell delivers election gift to Manchin and red-state Dems". POLITICO. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ^ "NRA-PVF Endorses Joe Manchin for U.S. Senate in West Virginia". NRA Political Victory Fund. October 2, 2012. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Friedman, Dan. "Sen. Joe Manchin drawing straws for votes on gun background check". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Terkel, Amanda (June 12, 2013). "Joe Manchin Targeted By NRA In New Ad". Huffington Post. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Bresnahan, John (June 17, 2013). "Joe Manchin takes on NRA in TV spot". Politico. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Simpson, Connor (March 3, 2013). "Sen. Joe Manchin Really Doesn't Want to Talk About Guns". The Wire. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Shapiro, Ilya (June 16, 2016). "Does Joe Manchin Want to Make America a Police State?". Cato Institute. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Sen. Joe Manchin Reveals Gross Contempt for U.S. Constitution". NRA-ILA. June 16, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Schor, Elana (January 12, 2017). "Manchin: I'll help GOP 'repair' Obamacare". Politico. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Sanger-Katz, Margot (September 17, 2018). "No. 1 Aim of Democratic Campaign Ads: Protect Pre-existing Conditions". The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ O'Brien, Soledad (January 14, 2017). "Sen. Joe Manchin On The Affordable Care Act". Matter of Fact.tv. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Potter, Chris (June 20, 2017). "Bob Casey and Joe Manchin: Senate plan to repeal Obamacare would worsen opioid epidemic". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Beavers, Olivia (September 12, 2017). "Manchin clarifies that he is 'skeptical' of single-payer system". The Hill. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Blau, Max (March 27, 2017). "Senator Joe Manchin: Time for a new 'war on drugs' to tackle opioids". STAT. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ King, Joselyn (February 3, 2018). "Sen. Joe Manchin Visits Unity Center in Benwood". The Intelligencer and Wheeling News Register. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Cohn, Alicia (January 24, 2018). "Senate confirms Trump health secretary". The Hill. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Sonmez, Felicia (December 18, 2010). "Joe Manchin absent for two major Senate votes". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ Wong, Scott; Toeplitz, Shira (December 18, 2010). "DREAM Act dies in Senate". Politico. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ Wise, Justin (June 14, 2018). "Manchin touts support for Trump border wall in new ad". The Hill. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ Schoen, John W. (February 16, 2018). "Here's how your senators voted on failed immigration proposals". CNBC. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ "Did Joe Manchin vote to fund the border wall?". Politifact. October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "Joe Manchin III's Ratings and Endorsements on Issue: Immigration". Vote Smart. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ "Manchin: Chaplains May Leave Military If 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' is Repealed". WOWK-TV. December 3, 2010. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Knezevich, Alison (December 9, 2010). "Manchin lone Democrat to oppose 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' repeal". Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on December 12, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wong, Scott (December 10, 2010). "Joe Manchin booed over 'Don't ask' vote". Politico. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Manchin won't back Dems effort in support of marriage equality". Washington Blade. March 2, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ Enten, Harry J. (April 10, 2013). "The final three: the Democratic senators against gay marriage". The Guardian. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "West Virginia Metro News". West Virginia Metro News. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Bill unveiled for seniors in emergency situations". The Parkersburg News and Sentinel. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Weigel, David (March 18, 2014). "Joe Manchin, Grover Norquist, and the Economic Consensus of #ThisTown". Slate. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Dickerson, Chris (March 30, 2017). "Manchin becomes first Democrat to say he'll vote for Gorsuch". West Virginia Record. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ Doocy, Peter (July 25, 2018). "Supreme Court pick shakes up West Virginia Senate race". Fox News. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ Higgins, Tucker (October 5, 2018). "Facing pressure at home, Manchin and Murkowski buck party lines in key vote on Kavanaugh". CNBC. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ Fandos, Nicholas; Stolberg, Sheryl (October 5, 2018). "Collins and Manchin Will Vote for Kavanaugh, All but Ensuring His Confirmation". The New York Times. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ Daniel, Annie (October 6, 2018). "How Every Senator Voted on Kavanaugh's Confirmation". The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ Dovere, Edward-Isaac (December 19, 2017). "'I Was An Easy Pickup': How Trump Lost Manchin on Taxes". Politico. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Drucker, David M. (December 20, 2017). "Joe Manchin struggles to explain opposition to GOP tax bill". The Washington Examiner. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Jilani, Zaid (June 19, 2017). "Joe Manchin was one of five Democrats who saved Saudi arms sales. His primary opponent is furious". The Intercept. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Jones, Katherine (November 11, 2005). "Governor Manchin Speaks Out on Pro-Life". WVNS-TV. West Virginia Media Holdings, LLC. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Goldsmith, Brian (May 9, 2008). "W.Va. Gov. In No Rush To End Race". CBSNews.com. CBS Interactive. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ O'Keefe, Ed (December 7, 2012). "Joe Manchin objects to MTV's 'Buckwild' reality show". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Buckwild". IMDb. January 3, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Joe Manchin III: The Harry Houdini of West Virginia Politics". The Huntington News. September 1, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Message for WVU: The board of governors must restore credibility". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. May 16, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Editorial: The Manchin PR Machine Keeps Rollin'. But Who Buys It?". The Huntington News. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Siegel, Zachary (December 22, 2016). "West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin: We Need To Declare A War on Drugs". The Fix. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Wieczner, Jen (August 26, 2016). "The Truth About Mylan CEO's 'Heather Bresch Situation' and Her MBA". Fortune. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ "Joe Manchin sued by brother over loan". The Washington Times. July 25, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Gallagher, Emily (June 30, 2015). "John Manchin drops lawsuit against two brothers". Times West Virginian. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ Rayfield, Jillian (December 18, 2010). "Joe Manchin Skipped DREAM And DADT Votes For A Christmas Party". Talking Points Memo.

- ^ Sonmez, Felicia (December 18, 2010). "Joe Manchin absent for two major Senate votes". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ Hamby, Peter; Killough, Ashley (June 18, 2012). "Manchin to skip Democratic National Convention". Political Ticker - CNN. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ "2008 Gubernatorial General Election Results, West Virginia". US Election Atlas. November 4, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

Further reading

Senator

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Profile at Vote Smart

Governor

- Profile at the National Governors Association

- Inaugural Address of Governor Joe Manchin III, January 17, 2005

External links

- Senator Joe Manchin official U.S. Senate site

- Joe Manchin for Senate

- Template:Dmoz

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1947 births

- 21st-century American politicians

- American people of Czech descent

- American people of Italian descent

- American Roman Catholics

- Aviators from West Virginia

- Catholics from West Virginia

- Democratic Party state governors of the United States

- Democratic Party United States Senators

- Governors of West Virginia

- Living people

- Manchin family

- Members of the West Virginia House of Delegates

- People from Farmington, West Virginia

- Secretaries of State of West Virginia

- United States Senators from West Virginia

- West Virginia Democrats

- West Virginia Mountaineers football players

- West Virginia state senators

- West Virginia University alumni