Immaculate Conception

Immaculate Conception of Mary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church (East and West) |

| Major shrine | Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception |

| Feast | December 8 (Roman Rite) December 9 (Byzantine Rite) |

| Attributes |

|

| Patronage | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Mariology of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

|

The Immaculate Conception is the belief that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception.[1] First debated by medieval theologians, it proved so controversial that it did not become part of official Catholic teaching until 1854, when Pius IX gave it the status of dogma in the papal bull Ineffabilis Deus.[2]

The Roman Missal and the Roman Rite Liturgy of the Hours include references to Mary's immaculate conception in the feast of the Immaculate Conception. The Immaculate Conception became a popular subject in literature,[3] but its abstract nature meant it was late in appearing as a subject in works of art.[4] The iconography of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception shows Mary standing, with arms outstretched or hands clasped in prayer. The feast day of the Immaculate Conception is December 8.[5]

Some Protestants rejected the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception as un-scriptural,[6] though some Anglicans accept it as a pious devotion.[7] It is not accepted by Eastern Orthodoxy due to differences in the understanding of original sin, although they do affirm Mary's purity and preservation from sin.[1]

Doctrine

The Immaculate Conception of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church, meaning that it is held to be a divinely revealed truth whose denial is heresy.[8] Defined by Pope Pius IX in Ineffabilis Deus in 1854, it states that Mary, through God's grace, was conceived free from the stain of original sin through her role as the Mother of God:[9]

We declare, pronounce, and define that the doctrine which holds that the most Blessed Virgin Mary, in the first instance of her conception, by a singular grace and privilege granted by Almighty God, in view of the merits of Jesus Christ, the Saviour of the human race, was preserved free from all stain of original sin, is a doctrine revealed by God and therefore to be believed firmly and constantly by all the faithful.[10]

While the Immaculate Conception asserts Mary's freedom from original sin, the Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563, had previously affirmed her freedom from personal sin.[11]

History

Anne, mother of Mary, and original sin

Anne appears as the mother of Mary in the late 2nd-century Gospel of James.[12] Anne and her husband, Saint Joachim, are infertile, but God hears their prayers and Mary is conceived. [13] According to historian Stephen Shoemaker, the conception occurs without sexual intercourse between Anne and Joachim, but the story does not advance the idea of an immaculate conception.[14] The Orthodox Church holds that "Mary is conceived by her parents as we are all conceived."[15]

Church Fathers

A variety of Church Fathers heap praise upon Mary, often employing language with immaculate connotations. In the late 4th Century, the great songwriter Ephrem the Syrian declares,

Only you and your Mother

are more beautiful than everything.

For on you, O Lord, there is no mark;

neither is there any stain in your Mother.[16]

In the Latin Vulgate Bible, the word "stain" here used, "macula,"[17] is the root-word source of the Latin word "Immaculate." St. Augustine takes especial precaution against scribing sin to Mary, writing,

In the matter of sin, it is my wish to exclude absolutely all questions concerning the holy Virgin Mary, on account of the honor due to Christ. For since she conceived and brought forth Him who most certainly was guilty of no sin, we know that an abundance of grace was given her that she might be in every way the conqueror of sin.[18]

In the early 5th Century, St. Theodotus of Ancyra, employing numerous verses from the Song of Songs, calls her,

"...a virgin innocent, without blemish, empty of any fault, inviolate, unpolluted, holy in soul and body,[19] like a lily blossoming among thorns,[20]

unversed in the evils of Eve; unsullied with feminine vanity; uninstructed in old wives' tales; [having] ears un-dirtied with bad gossip; a tongue unpolluted with dishonest discourse; eyes uninfected with illicit gaze;

who didn't disfigure her natural color with the added colors of lust, nor spread her cheeks with makeup; nor received brightness upon her neck from jewels formed into a necklace; nor bound her hands with bracelets, or her feet with twisted golden ribbons; nor would've been softened with the appearances of perfumes; nor, like a bride, received a splendid dress from men; nor incised the likenesses of error into her heart:

far be it, that she practiced either these things, or similar ones (for neither does darkness have any communion with light[21]):

But she who was not yet born was consecrated to God her creator; truly, she was born as a true monument of a pleasing soul; as a holy nursling she was offered that she might pass her days in the shrine and temple, a disciple of the Law, smeared with [oil of] the Holy Spirit, clothed with divine grace as with a pallium, knowing the divine [secrets] in her soul, wedded in heart to God, breathing forth the splendors of sanctity from her eyes, intoning canticles with her ears, a tongue flowing with honey, with her lips distilling forth honeycomb;[22]

beautiful in her steps, more beautiful in her demeanors; venerable in her speech, more venerable in her deeds; meek in her behaviors, more meek in her movements; good in the eyes of men, better in the contemplations of God;

she who received God in her womb, and truly gave forth God in birth; lastly, if I might say a word, all-beautiful[23], as an eager will, all sweet, as a storeroom of myrrhs[24];"[25][26]

Medieval formulation

By the 4th century it was generally accepted that Mary was free of personal sin,[27] but original sin raised the question of whether she was also free of the sin passed down from Adam.[28] The question became acute when the feast of her conception began to be celebrated in England in the 11th century,[29] and the opponents of the feast of Mary's conception brought forth the objection that as sexual intercourse is sinful, to celebrate Mary's conception was to celebrate a sinful event.[30] (The feast of Mary's conception originated in the Eastern Church in the 7th century, reached England in the 11th, and from there spread to Europe, where it was given official approval in 1477 and extended to the whole Church in 1693; the word "immaculate" was not officially added to the name of the feast until 1854).[29]

The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception caused a virtual civil war between Franciscans and Dominicans during the middle ages, with Franciscan 'Scotists' in its favour and Dominican 'Thomists' against it.[31] [32] The English ecclesiastic and scholar Eadmer (c.1060-c.1126) reasoned that it was possible that Mary was conceived without original sin in view of God's omnipotence, and that it was also appropriate in view of her role as Mother of God: Potuit, decuit, fecit, "it was possible, it was fitting, therefore it was done."[33] Others, including Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) and Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), objected that if Mary were free of original sin at her conception then she would have no need of redemption, making Christ superfluous; they were answered by Duns Scotus (1264–1308), who "developed the idea of preservative redemption as being a more perfect one: to have been preserved free from original sin was a greater grace than to be set free from sin."[34] In 1439, the Council of Basel, in schism with Pope Eugene IV who resided at the Council of Florence,[35] declared Mary's Immaculate Conception a "pious opinion" consistent with faith and Scripture; the Council of Trent, held in several sessions in the early 1500s, made no explicit declaration on the subject but exempted her from the universality of original sin; and by 1571 the Pope's Breviary (prayerbook) set out an elaborate celebration of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception on 8 December.[36]

Popular devotion and Ineffabilis Deus

The eventual creation of the dogma was due more to popular devotion than scholarship.[37] The Immaculate Conception became a popular subject in literature and art,[3] and some devotees went so far as to hold that Anne had conceived Mary by kissing her husband Joachim, and that Anne's father and grandmother had likewise been conceived without sexual intercourse, although St Bridget of Sweden (c.1303–1373) told how Mary herself had revealed to her that Anne and Joachim conceived their daughter through a sexual union which was sinless because it was pure and free of sexual lust.[38]

In the 16th and especially the 17th centuries there was a proliferation of Immaculatist devotion in Spain, leading the Habsburg monarchs to demand that the papacy elevate the belief to the status of dogma.[39] In France in 1830 Catherine Labouré (May 2, 1806 – December 31, 1876) saw a vision of Mary as the Immaculate Conception standing on a globe while a voice commanded her to have a medal made in imitation of what she saw,[40] and her vision marked the beginning of a great 19th-century Marian revival.[41]

In 1849 Pope Pius IX issued the encyclical Ubi primum soliciting the Bishops of the Church for their views on whether the doctrine should be defined as dogma; ninety percent of those who responded were supportive, while the rest against, one of them was the Archbishop of Paris, Marie-Dominique-Auguste Sibour, who warned that the Immaculate Conception "could be proved neither from the Scriptures nor from tradition", [42] and in 1854 the Immaculate Conception dogma was proclaimed with the bull Ineffabilis Deus.[43]

Dom Prosper Guéranger, Abbot of Solesmes Abbey, who had been one of the main promoters of the dogmatic statement, wrote Mémoire sur l'Immaculée Conception, explaining what he saw as its basis:

For the belief to be defined as a dogma of faith ... it is necessary that the Immaculate Conception form part of Revelation, expressed in Scripture or Tradition, or be implied in beliefs previously defined. Needed, afterward, is that it be proposed to the faith of the faithful through the teaching of the ordinary magisterium. Finally, it is necessary that it be attested by the liturgy, and the Fathers and Doctors of the Church.[44]

Guéranger maintained that these conditions were met and that the definition was therefore possible. Ineffabilis Deus found the Immaculate Conception in the Ark of Salvation (Noah's Ark), Jacob's Ladder, the Burning Bush at Sinai, the Enclosed Garden from the Song of Songs, and many more passages.[45] From this wealth of support the pope's advisors singled out Genesis 3:15: "The most glorious Virgin ... was foretold by God when he said to the serpent: 'I will put enmity between you and the woman,'"[46] a prophecy which reached fulfilment in the figure of the Woman in the Revelation of John, crowned with stars and trampling the Dragon underfoot.[47] Luke 1:28, and specifically the phrase "full of grace" by which Gabriel greeted Mary, was another reference to her Immaculate Conception: "she was never subject to the curse and was, together with her Son, the only partaker of perpetual benediction."[48]

Ineffabilis Deus was one of the pivotal events of the papacy of Pius, pope from 16 June 1846 to his death on 7 February 1878.[49] Four years after the proclamation of the dogma, in 1858, Mary appeared to the young Bernadette Soubirous at Lourdes in southern France, to announce that she was the Immaculate Conception.[50]

Feast, patronages and disputes

The feast day of the Immaculate Conception is December 8.[5] Its celebration seems to have begun in the Eastern church in the 7th century and may have spread to Ireland by the 8th, although the earliest well-attested record in the Western church is from England early in the 11th.[51] It was suppressed there after the Norman Conquest (1066), and the first thorough exposition of the doctrine was a response to this suppression.[51] It continued to spread through the 15th century despite accusations of heresy from the Thomists and strong objections from several prominent theologians. [52] Beginning around 1140 St Bernard of Clairvaux, a Cistercian monk, wrote to Lyons Cathedral to express his surprise and dissatisfaction that it had recently begun to be observed there,[30] but in 1477 Pope Sixtus IV, a Franciscan Scotist and devoted Immaculist, placed it on the Roman calendar (i.e., list of Church festivals and observances) via the bull Cum praexcelsa.[53] Thereafter in 1481 and 1483, in response to the polemic writings of the prominent Thomist, Vincenzo Bandello, Pope Sixtus IV published two more bulls which forbade anybody to preach or teach against the Immaculate Conception, or for either side to accuse the other of heresy, on pains of excommunication. Pope Pius V kept the feast on the tridentine calendar but suppressed the word "immaculate".[54] Gregory XV in 1622 prohibited any public or private assertion that Mary was conceived in sin. Urban VIII in 1624 allowed the Franciscans to establish a military order dedicated to the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception.[54] Following the promulgation of Ineffabilis Deus the typically Franciscan phrase "immaculate conception" reasserted itself in the title and euchology (prayer formulae) of the feast. Pius IX solemnly promulgated a mass formulary drawn chiefly from one composed 400 years by a papal chamberlain at the behest of Sixtus IV, beginning "O God who by the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin...". [55]

By pontifical decree a number of countries are considered to be under the patronage of the Immaculate Conception. These include Argentina, Brazil, Korea, Nicaragua, Paraguay, the Philippines, Spain (including the old kingdoms and the present state), the United States and Uruguay. By royal decree under the House of Bragança, she is the principal Patroness of Portugal.[citation needed]

Prayers and hymns

The Roman Missal and the Roman Rite Liturgy of the Hours naturally include references to Mary's immaculate conception in the feast of the Immaculate Conception. An example is the antiphon that begins: "Tota pulchra es, Maria, et macula originalis non est in te" ("You are all beautiful, Mary, and the original stain [of sin] is not in you." It continues: "Your clothing is white as snow, and your face is like the sun. You are all beautiful, Mary, and the original stain [of sin] is not in you. You are the glory of Jerusalem, you are the joy of Israel, you give honour to our people. You are all beautiful, Mary.")[56] On the basis of the original Gregorian chant music,[57] polyphonic settings have been composed by Anton Bruckner,[58] Pablo Casals, Maurice Duruflé,[59] Grzegorz Gerwazy Gorczycki,[60] Ola Gjeilo,[61] José Maurício Nunes Garcia,[62] and Nikolaus Schapfl.[63]

Other prayers honouring Mary's immaculate conception are in use outside the formal liturgy. The Immaculata prayer, composed by Saint Maximillian Kolbe, is a prayer of entrustment to Mary as the Immaculata.[64] A novena of prayers, with a specific prayer for each of the nine days has been composed under the title of the Immaculate Conception Novena.[65]

Ave Maris Stella is the vesper hymn of the feast of the Immaculate Conception.[66] The hymn Immaculate Mary, addressed to Mary as the Immaculately Conceived One, is closely associated with Lourdes.[67]

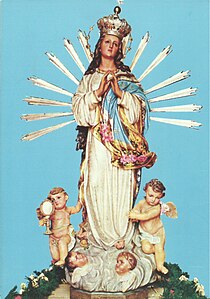

Artistic representation

The Immaculate Conception became a popular subject in literature,[3] but its abstract nature meant it was late in appearing as a subject in art.[4] During the Medieval period it was depicted as "Joachim and Anne Meeting at the Golden Gate", meaning Mary's conception through the chaste kiss of her parents at the Golden Gate in Jerusalem;[68] the 14th and 15th centuries were the heyday for this scene, after which it was gradually replaced by more allegorical depictions featuring an adult Mary.[69] The 1476 extension of the feast of the Immaculate Conception to the entire Latin Church reduced the likelihood of controversy for the artist or patron in depicting an image, so that emblems depicting The Immaculate Conception began to appear. Many artists in the 15th century faced the problem of how to depict an abstract idea such as the Immaculate Conception, and the problem was not fully solved for 150 years. The Italian Renaissance artist Piero di Cosimo was among those artists who tried new solutions, but none of these became generally adopted so that the subject matter would be immediately recognisable to the faithful.[citation needed]

The definitive iconography for the depiction of "Our Lady" seems to have been finally established by the painter and theorist Francisco Pacheco in his "El arte de la pintura" of 1649: a beautiful young girl of 12 or 13, wearing a white tunic and blue mantle, rays of light emanating from her head ringed by twelve stars and crowned by an imperial crown, the sun behind her and the moon beneath her feet.[70] Pacheco's iconography influenced other Spanish artists or artists active in Spain such as El Greco, Bartolomé Murillo, Diego Velázquez, and Francisco Zurbarán, who each produced a number of artistic masterpieces based on the use of these same symbols.[71] The popularity of this particular representation of The Immaculate Conception spread across the rest of Europe, and has since remained the best known artistic depiction of the concept: in a heavenly realm, moments after her creation, the spirit of Mary (in the form of a young woman) looks up in awe at (or bows her head to) God. The moon is under her feet and a halo of twelve stars surround her head, possibly a reference to "a woman clothed with the sun" from Revelation 12:1–2. Additional imagery may include clouds, a golden light, and putti. In some paintings the putti are holding lilies and roses, flowers often associated with Mary.[72]

-

Rubens, Immaculate Conception, 1628–1629

-

Zurbarán, Immaculate Conception, 1630

-

Murillo, Immaculate Conception, 1650

-

Murillo, Immaculate Conception, 1660

-

Murillo, Immaculate Conception, 1678

-

Carlo Maratta, 1689

-

Juan Antonio Escalante, 17th century

-

Caxias do Sul museum, Brazil

-

Statue, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 19th century

-

Palmi, Calabria, Immaculate Conception, 1925

-

Nicaragua, Immaculate Conception, 1950

-

Our Lady of Aparecida, Brasilia

-

A bronze statue of the Immaculate Conception at the Manila Cathedral in Intramuros, Manila, Philippines

Other churches

Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy never accepted Augustine's specific ideas on original sin, and in consequence did not become involved in the later developments that took place in the Roman Catholic Church, including the Immaculate Conception.[73][74] When in 1894 Pope Leo XIII addressed the Eastern church in his encyclical Praeclara gratulationis, Ecumenical Patriarch Anthimos in 1895 replied with an encyclical approved by the Constantinopolitan Synod in which he stigmatised the dogmas of the Immaculate Conception and papal infallibility as "Roman novelties" and called on the Roman church to return to the faith of the early centuries.[75] Eastern Orthodox Bishop Kallistos Ware comments that "the Latin dogma seems to us not so much erroneous as superfluous."[76]

Oriental Orthodoxy

The Eritrean and Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo do believe in the Immaculate Conception of the Theotokos. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church celebrates the Feast of the Immaculate Conception on Nehasie 7 (August 13).[77][78] The 96th chapter of the Kebra Nagast states: “He cleansed Eve's body and sanctified it and made for it a dwelling in her for Adam’s salvation. She [i.e., Mary] was born without blemish, for He made her pure, without pollution, and she redeemed his debt without carnal union and embrace...Through the transgression of Eve, we died and were buried, and by the purity of Mary we receive the honor, and are exalted to the heights.”

Old Catholics

In the mid-19th century, some Catholics who were unable to accept the doctrine of papal infallibility left the Roman Church and formed the Old Catholic Church. This movement rejects the Immaculate Conception.[79][80]

Protestantism

Protestants overwhelmingly condemned the promulgation of Ineffabilis Deus as an exercise in papal power, and the doctrine itself as un-scriptural,[6] for it denied that all had sinned and rested on the Latin translation of Luke 1:28 (the "full of grace" passage) that the original Greek did not support.[81] Protestants, therefore, teach that Mary was a sinner saved through grace like all believers.[48] The ecumenical Lutheran-Catholic Statement on Saints, Mary, issued in 1990, after seven years of study and discussion, conceded that Lutherans and Catholics remained separated "by differing views on matters such as the invocation of saints, the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption of Mary;"[82] the final report of the Anglican–Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC), created in 1969 to further ecumenical progress between the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion, similarly recorded the disagreement of the Anglicans with the doctrine, although Anglo-Catholics may hold the Immaculate Conception as an optional pious belief.[83]

See also

- Act for the Immaculate Conception of Mary

- Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception (disambiguation)

- Church of the Immaculate Conception (disambiguation)

- Congregation of the Immaculate Conception

- Marian doctrines of the Catholic Church

- Marian Fathers of the Immaculate Conception

- Miraculous medal

- Mother of God (Roman Catholic)

- Patronages of the Immaculate Conception

- Perpetual virginity of Mary

- Roman Catholic Marian art

References

Citations

- ^ a b Tinsley 2005, p. 286.

- ^ Wright 1992, p. 237.

- ^ a b c Twomey 2008, p. ix.

- ^ a b Hall 2018, p. 337.

- ^ a b Barrely 2014, p. 40.

- ^ a b Herringer 2019, p. 507.

- ^ "Immaculate Conception". An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church, A User Friendly Reference for Episcopalians. Retrieved May 3, 2022 – via Episcopal Church.

- ^ Collinge 2012, p. 133.

- ^ Collinge 2012, p. 209.

- ^ Sheed 1958, pp. 134–138.

- ^ Fastiggi 2019, p. 455.

- ^ Nixon 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Nixon 2004, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Shoemaker 2016, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Hopko, Thomas. The Winter Pascha Chapter 9, Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America

- ^ Ephrem, St. (350). "27:8". Nisibene Hymns (in Syriac). Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium. p. 109. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "Song of Songs 4:7". Vulgate.

- ^ Augustine, St. "42(36)". On Nature and Grace.

- ^ "1 Cor. 7:34". Bible.

- ^ "Song of Songs 2:2". Bible.

- ^ "2 Cor. 6:14". Bible.

- ^ "Song of Songs 4:11". Bible.

- ^ "Song of Songs 4:7". Bible. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- ^ "Song of Songs 4:6". Bible.

- ^ of Ancyra, Theodotus (1859). Migne, J.P. (ed.). Patrologiae Graeca, vol. 77 (in Latin). p. 1427. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

...virgo innocens, sine macula, omni culpa vacans, intemerata, impolluta, sancta animo et corpore, sicut lilium inter medias spinas germinans: non docta Evæ mala; non muliebri vanitate foedata; non anilibus instituta fabulis; non malo auditu aures sordidata; non inhonesto sermone polluta linguam, non visu illicito infecta oculos; quæ nativum colorem luxuriæ adductis coloribus non deturparit, non fucis genas obduxerit; non collo efformatis in torques lapillis fulgorem asciverit; non manus armillis, pedesque aureis torquibus vinxerit; non unguentariorum speciebus emollita sit; non splendidam vestem ab hominibus sponsa acceperit; non erroris simulacra cordi insculpserit: longe hæc facessant, et similia (neque enim tenebris ad lucem ulla communio est): sed quæ necdum nata auctori Deo consecrata sit ; nata vero grati animi monumento, sacra alumna ut in sacrario ac templo moraretur oblata fuerit, legis discipula, Spiritu sancto delibuta, divina gratia ut palliolo amicta, animo divina sapiens, Deo corde nupta, sanctitatis splendores oculis spirans, auribus cantica insonans, lingua melliflua, labiis favum stillantibus; pulchra gressibus, moribus pulchrior; sermone venerabilis, actione venerabilior; mansueta moribus, mansuetior motibus; bona in hominum oculis, Dei obtutibus melior ; quæ Deum ventre susceperit, vereque Deum partu ediderit; atque, ut verbo dicam, tota pulchra ut propensa voluntas, totaque suavis ut cella unguentaria.

- ^ Lennerz, H. (1957). De Beata Virgine: Tractatus Dogmaticus (in Latin). Rome: Gregorian University. p. 88. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ Shoemaker 2016, p. 119.

- ^ Coyle 1996, p. 36-37.

- ^ a b Collinge 2012, p. 209-210.

- ^ a b Boss 2000, p. 126.

- ^ Cameron 1996, p. 335.

- ^ Kappes 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Coyle 1996, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Coyle 1996, p. 38.

- ^ Kappes 2014, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Reynolds 2012, pp. 4–5, 117.

- ^ Granziera 2019, p. 469.

- ^ Solberg 2018, p. 108-109.

- ^ Hernández 2019, p. 6.

- ^ Mack 2003.

- ^ Foley 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Schaff 1931, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Foley 2002, p. 153.

- ^ "How Abbot of Solesmes Explained the Immaculate Conception", Zenit, December 9, 2004

- ^ Manelli 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Manelli 1994, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Twomey 2008, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b German 2001, p. 596.

- ^ Hillerbrand 2012, p. 250.

- ^ Hammond 2003, p. 602.

- ^ a b Boss 2000, p. 124.

- ^ Boss 2000, p. 128.

- ^ Manelli 2008, p. 643.

- ^ a b Hernández 2019, p. 38.

- ^ Manelli 2008, pp. 643–644.

- ^ The text (in Latin) is given at Tota Pulchra Es – GMEA Honor Chorus.

- ^ Tota pulchra es Maria, Canto gregoriano nella devozione mariana, studio di Giovanni Vianini, Milano. November 6, 2008. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Anton Bruckner – Tota pulchra es. October 3, 2008. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Maurice Duruflé: Tota pulchra es Maria. May 23, 2010. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Tota pulchra es – Grzegorz Gerwazy Gorczycki. June 17, 2011. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ TOTA PULCHRA ES GREX VOCALIS. May 21, 2009. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Tota pulchra es, Maria Canto gregoriano nella devozione mariana. September 21, 2008. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Tota Pulchra – Composed by Nikolaus Schapfl (*1963). January 4, 2010. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Prayers of Consecration". Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Nine Days Of Prayer – Immaculate Conception".

- ^ Sutfin, Edward J., True Christmas Spirit, Grail Publications, St. Meinrad, Indiana, 1955

- ^ "Immaculate Conception Prayers".

- ^ Hall 2018, p. 175.

- ^ Hall 2018, p. 171.

- ^ Moffitt 2001, p. 676.

- ^ Katz & Orsi 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Jenner 1910, pp. 3–9.

- ^ McGuckin 2010, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Coyle 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Meyendorff 1981, p. 90.

- ^ Ware 1995, p. 77.

- ^ "What is our position on St. Mary and Immaculate Conception and what is it?". January 19, 2016.

- ^ "THE BIRTH OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY – Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Sunday School Department – Mahibere Kidusan".

- ^ Hillerbrand 2012, p. 63.

- ^ Smit 2019, pp. 14, 53.

- ^ Hammond 2003, p. 601.

- ^ J. Francis Stafford, Avery Dulles, Robert B. Eno, Joseph A Fitzmyer, Elizabeth Johnson, Killian McDonnell, Carl J. Peter, Walter Principe, Georges Tavard, Frederick M. Jelly, John f. Hotchkin, George Anderson, Robert W. Bertram, Joseph W. Burgess, Gerhard O. Forde, Karlfried Froelich, Eric Gritsch, Kenneth Hagen, John Reumann, Daniel F. Martensen, Horace Hummel, John F. Johnson (February 23, 1990). "Lutheran-Catholic Statement on Saints, Mary" (PDF). USCCB. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Armentrout 2000, p. 260.

Bibliography

- Armentrout, Don S. (2000). An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A User-Friendly Reference for Episcopalians. Church Publishing. ISBN 9780898697018.

- Barrely, Christine (2014). The Little Book of Mary. Chronicle Books. ISBN 9781452135663.

- Boring, Eugene (2012). An Introduction to the New Testament: History, Literature, Theology. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9788178354569.

- Boss, Sarah Jane (2000). Empress and Handmaid: On Nature and Gender in the Cult of the Virgin Mary. A&C Black. ISBN 9780304707812.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1995). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837851.

- Brown, Raymond Edward (1978). Mary in the New Testament. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809121687.

- Buchanan, Colin (2015). Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442250161.

- Cameron, Euan (1996), "Cultural and Sociopolitical Context of the Reformation", in Sæbø, Magne; Brekelmans, Christianus; Haran, Menahem; Fishbane, Michael A.; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.), Hebrew Bible, Old Testament: The History of Its Interpretation, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 9783525539828

- Carrigan, Henry L. (2000). "Virgin Birth". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Collinge, William J. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Catholicism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810879799.

- Coyle, Kathleen (1996). Mary in the Christian Tradition: From a Contemporary Perspective. Gracewing Publishing. ISBN 9780852443804.

- Elliott, J.K. (1993). The Apocryphal New Testament: A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191520327.

- Espín, Orlando O. (2007). "Immaculate Conception". In Espín, Orlando O.; Nickoloff, James B. (eds.). An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658567.

- Fastiggi, Robert (2019). "Mariology in the Counter-Reformation". In Maunder, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198792550.

- Foley, Donal Anthony (2002). Marian Apparitions, the Bible, and the Modern World. Gracewing Publishing. ISBN 9780852443132.

- German, T.J. (2001). "Immaculate Conception". In Elwell, Walter A. (ed.). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801020759.

- Göle, Nilüfer (2016). Islam and Public Controversy in Europe. Routledge. ISBN 9781317112549.

- Granziera, Patrizia (2019). "Mary and Inculturation in Mexico and India". In Maunder, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198792550.

- Hall, James (2018). Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art. Routledge. ISBN 9780429962509.

- Hernández, Rosilie (2019). Immaculate Conceptions: The Power of the Religious Imagination in Early Modern Spain. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781487504779.

- Herringer, Carol Engelhardt (2019). "Mary as Cultural Symbol in the Nineteenth Century". In Maunder, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198792550.

- Hillerbrand, Hans J. (2012). A New History of Christianity. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426719141.

- Hammond, Carolyn (2003). "Mary". In Houlden, James Leslie (ed.). Jesus in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576078563.

- Jenner, Katherine Lee Rawlings (1910). Our Lady in Art. A.C. McClurg & Company. OCLC 903296042.

- Kappes, Christiaan (2014). Immaculate Conception: Why Thomas Aquinas Denied, While Duns Scotus, Gregory Palamas, and Mark Eugenicus Professed Absolute Immaculate Existence of Mary. New Bedford, MA: Academy of the Immaculate.

- Katz, Melissa R.; Orsi, Robert A. (2001). Divine Mirrors: The Virgin Mary in the Visual Arts. Oxford University Press.

- Kritzeck, James Aloysius (2015). Peter the Venerable and Islam. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400875771.

- Lohse, Bernhard (1966). A Short History of Christian Doctrine. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451404234.

- Mack, John (2003). The museum of the mind: art and memory in world cultures. British Museum.

- Manelli, Fr. Stephano (1994). All Generations Shall Call Me Blessed: Biblical Mariology. Academy of the Immaculate. ISBN 9781601140005.

- Manelli, Fr. Stephano (2008). "The Mystery of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Old Testament". In Miravalle, Mark I. (ed.). Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons. Seat of Wisdom Books. ISBN 9781579183554.

- Maunder, Chris (2019). "Introduction". In Maunder, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198792550.

- Meyendorff, Jean (1981). The Orthodox Church: Its Past and Its Role in the World Today. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9788178354569.

- McGuckin, John Anthony (2010). The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444393835.

- Moffitt, John F. (2001), "Modern Extraterrestrial Portraiture", in Caron, Richard; Godwin, Joscelyn; Hanegraaff, Wouter J.; Vieillard-Baron, Jean-Louis (eds.), Esotérisme, gnoses & imaginaire symbolique: mélanges offerts à Antoine Faivre, Peeters Publishers, ISBN 9789042909557

- Mullett, Michael A. (1999). The Catholic Reformation. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415189149.

- Nixon, Virginia (2004). Mary's Mother: Saint Anne in Late Medieval Europe. Penn State Press. ISBN 0271024666.

- Norman, Edward R. (2007). The Roman Catholic Church: An Illustrated History. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520252516.

- Obach, Robert (2008). The Catholic Church on Marital Intercourse: From St. Paul to Pope John Paul II. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739130896.

- O'Collins, Gerald (1983), "Dogma", in Richardson, Alan; Bowden, John (eds.), The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 9780664227487

- Pies, Ronald W. (2000). The Ethics of the Sages: An Interfaith Commentary on Pirkei Avot. Jason Aronson. ISBN 9780765761033.

- Reynolds, Brian (2012). Gateway to Heaven: Marian Doctrine and Devotion, Image and Typology in the Patristic and Medieval Periods, Volume 1. New City Press. ISBN 9781565484498.

- Schaff, Philip (1931). Creeds of Christendom: Volume I (6th ed.). CCEL. ISBN 9781610250375.

- Sheed, Frank J. (1958). Theology for Beginners. A&C Black. ISBN 9780722074251.

- Shoemaker, Stephen J. (2016). Mary in Early Christian Faith and Devotion. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300219531.

- Smit, Peter-Ben (2019). Old Catholic Theology: An Introduction. Brill. ISBN 9789004412149.

- Solberg, Emma Maggie (2018). Virgin Whore. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501730344.

- Stortz, Martha Ellen (2001). "Where or When Was Your Servant Innocent?". In Bunge, Marcia J. (ed.). The Child in Christian Thought. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846938.

- Tinsley, E.J. (2005), "Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary", in Richardson, Alan; Bowden, John (eds.), The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology, Presbyterian Publishing House, ISBN 9780664227487

- Toews, John (2013). The Story of Original Sin. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781620323694.

- Twomey, Lesley K. (2008). The Serpent and the Rose: The Immaculate Conception and Hispanic Poetry in the Late Medieval Period. Brill. ISBN 9789047433200.

- Ware, Bishop Kallistos (1995). The Orthodox Way. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780913836583.

- Wiley, Tatha (2002). Original Sin: Origins, Developments, Contemporary Meanings. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809141289.

- Williams, Paul (2019). "The Virgin Mary in the Eucharist". In Maunder, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198792550.

- Wright, David F. (1992). "Mary". In McKim, Donald K.; Wright, David F. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Reformed Faith. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664218829.

External links

- Ineffabilis Deus – encyclical defining the Immaculate Conception