Tom Seaver

| Tom Seaver | |

|---|---|

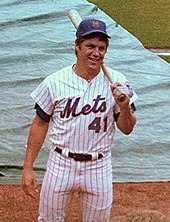

Seaver with the New York Mets, c. 1971 | |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: November 17, 1944 Fresno, California, U.S. | |

| Died: August 31, 2020 (aged 75) Calistoga, California, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 13, 1967, for the New York Mets | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 19, 1986, for the Boston Red Sox | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 311–205 |

| Earned run average | 2.86 |

| Strikeouts | 3,640 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1992 |

| Vote | 98.8% (first ballot) |

George Thomas Seaver (November 17, 1944 – August 31, 2020), nicknamed "Tom Terrific" and "the Franchise", was an American professional baseball pitcher who played 20 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). He played for the New York Mets, Cincinnati Reds, Chicago White Sox, and Boston Red Sox from 1967 to 1986. Commonly described as the most iconic player in Mets history, Seaver played a significant role in their victory in the 1969 World Series over the Baltimore Orioles.

With the Mets, Seaver won the National League's (NL) Rookie of the Year Award in 1967, and won three NL Cy Young Awards as the league's best pitcher. He was a 12-time All-Star and ranks as the Mets' all-time leader in wins. During his MLB career, he compiled 311 wins, 3,640 strikeouts, 61 shutouts, a 2.86 earned run average, and he threw a no-hitter in 1978.

In 1992, Seaver was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the highest percentage of votes ever recorded at the time.[a] Along with Mike Piazza, he is one of two players wearing a New York Mets hat on his plaque in the Hall of Fame. Seaver's No. 41 was retired by the Mets in 1988, and New York City changed the address of Citi Field to 41 Seaver Way in 2019. Seaver is also a member of the New York Mets Hall of Fame and the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame.

Early life

[edit]Seaver was born in Fresno, California, to Betty Lee (née Cline) and Charles Henry Seaver. He attended Fresno High School and was a pitcher for the school's baseball team.[1] Seaver compensated for his lack of size and strength by developing great control on the mound. Despite being an All-City basketball player, he hoped to play baseball in college. He joined the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve on June 28, 1962. He served with AIRFMFPAC 29 Palms, California, through July 1963.[2] After six months of active duty in the reserve, Seaver enrolled at Fresno City College.[1] He remained a part-time member of the reserve until his eight-year commitment ended in 1970.[3]

The University of Southern California (USC) recruited Seaver to play college baseball. Unsure as to whether Seaver was worthy of a scholarship, USC sent him to pitch in Alaska for the Alaska Goldpanners of Fairbanks in the summer of 1964. After a stellar season, in which he pitched and won a game in the national tournament with a grand slam, USC head coach Rod Dedeaux awarded him a scholarship. As a sophomore in 1965, Seaver posted a 10–2 record for the Trojans, and he was selected in the tenth round of the 1965 Major League Baseball draft by the Los Angeles Dodgers.[4] When Seaver asked for $70,000, however, the Dodgers passed, only offering Seaver $2,000.[5]

In 1966, Seaver signed a professional contract with the Atlanta Braves, who had selected him in the first round of the secondary January draft, 20th overall. However, the contract was voided by Baseball Commissioner William Eckert because USC had played two exhibition games that year, although Seaver had not participated.[4] He then intended to finish the college season, but because he had signed a pro contract, the NCAA ruled him ineligible. After Seaver's father complained to Eckert about the unfairness of the situation, and threatened a lawsuit, Eckert ruled that other teams could match the Braves' offer.[5] The Mets were subsequently awarded his signing rights in a lottery drawing among the three teams (the Philadelphia Phillies and Cleveland Indians being the two others) that were willing to match the Braves' terms.[6]

Professional playing career

[edit]Minor leagues (1966)

[edit]In 1966, Seaver was 12–12 with a 3.13 earned run average pitching in Class AAA with the Jacksonville Suns, the Mets' affiliate in the International League.[7]

New York Mets (1967–1977)

[edit]Seaver made the Mets' roster in 1967, was named to the 1967 All-Star Game, and got the save by pitching a scoreless 15th inning.[8] In his rookie season, Seaver was 16–13 for the last-place Mets, with 18 complete games, 170 strikeouts, and a 2.76 earned run average. Seaver was named the 1967 National League Rookie of the Year.[9]

Seaver recalled later on that he approached Henry Aaron just before the All-Star Game, for his autograph. Seaver felt the need to introduce himself to Aaron, as he was certain that the veteran player would not know who he was. Aaron replied to Seaver, "Kid, I know who you are, and before your career is over, I guarantee you everyone in this stadium will, too."[10]

Seaver started for the Mets on Opening Day in 1968.[11] He won 16 games again during that season, and recorded over 200 strikeouts for the first of nine consecutive seasons, but the Mets moved up only one spot in the standings, to ninth.[12] In 1969, Seaver won a league-high 25 games, including nine consecutive complete-game victories. He won his first National League Cy Young Award. He also finished runner-up to Willie McCovey for the League's Most Valuable Player Award.[13]

In front of a crowd of over 59,000 at New York's Shea Stadium on July 9, Seaver threw 8+1⁄3 perfect innings against the division-leading Chicago Cubs. Rookie backup outfielder Jim Qualls broke up Seaver's bid for a perfect game when he lined a clean single to left field.[14][15]

In the inaugural National League Championship Series, Seaver outlasted Atlanta's Phil Niekro in the first game for a 9–5 victory. Seaver was also the starter for Game One of the World Series, but lost a 4–1 decision to the Baltimore Orioles' Mike Cuellar. Seaver then pitched a 10-inning complete game for a 2–1 win in Game Four. The "Miracle Mets" won the series.[1] At year's end, Seaver was presented with the Hickok Belt as the top professional athlete of the year and Sports Illustrated magazine's "Sportsman of the Year" award.[16][17]

On April 22, 1970, Seaver set a major league record by striking out the final ten batters of the game in a 2–1 victory over the San Diego Padres at Shea Stadium.[18] Al Ferrara, who had homered in the second inning for the Padres' run, accounted for both the first and the final strikeout of the streak. In addition to his ten consecutive strikeouts, Seaver tied Steve Carlton's major league record at the time,[19] with 19 strikeouts in a nine-inning game.[20] (The record was later eclipsed by 20-strikeout games by Kerry Wood, Randy Johnson, Max Scherzer, and twice by Roger Clemens.)[21] By mid-August, Seaver's record stood at 17–6 and he seemed well on his way to a second consecutive 20-victory season. But he only won one of his last ten starts, including four on short rest, to finish 18–12. Nonetheless, Seaver led the National League in both earned run average (2.82) and strikeouts (283).[22]

In 1971, Seaver led the league in earned run average (1.76) and strikeouts (289 in 286 innings) while going 20–10. However, he finished second in the Cy Young balloting to Ferguson Jenkins of the Chicago Cubs, due to Jenkins' league-leading 24 wins, 325 innings pitched, and exceptional control numbers.[23]

Seaver had four more 20-win seasons (20 in 1971, 21 in 1972, 22 in 1975, and 21 in 1977). He won two more Cy Young Awards (1973 and 1975, both with the Mets). Between 1970 and 1976, Seaver led the National League in strikeouts five times, while also finishing second in 1972 and third in 1974. Seaver also won three earned run average titles as a Met. Two famous quotes about Seaver are attributed to Reggie Jackson: "Blind men come to the park just to hear him pitch."[24] The second was in the 1973 World series, with the Mets up 3 games to 2, and poised to win their second championship. Seaver started the game, but did not have his "arm" that day, and lost the game. Jackson is reported to have said "Seaver pitched with his heart that day." Seaver was known for his "drop and drive" overhand delivery, powered by his legs and trunk with his knee sinking to the ground.[25]

Midnight Massacre

[edit]By 1977, free agency had begun and contract negotiations between Mets' ownership and Seaver were not going well. Seaver wanted to renegotiate his contract to bring his salary in line with what other top pitchers were earning, but chairman of the board M. Donald Grant, who by that time had been given carte blanche by Mets management to do what he wished, refused to budge. Longtime New York Daily News columnist Dick Young regularly wrote negative columns about Seaver's "greedy" demands. Seaver attempted to resolve the impasse by going to team owner Lorinda de Roulet, who along with general manager Joe McDonald, had negotiated in principle a three-year contract extension by mid-June. Before the contract could be signed, Young wrote an unattributed story in the Daily News saying that Seaver was being goaded by his wife to ask for more money because she was envious of Nolan Ryan earning more money with the California Angels. Upon learning of the story, Seaver informed de Roulet and McDonald that he immediately wanted to be traded, believing that he could not co-exist with Grant.[26]

In one of two trades that New York's sports reporters dubbed "the Midnight Massacre" (the other involved struggling outfielder Dave Kingman), Seaver was traded to the Cincinnati Reds at the trading deadline, June 15, 1977, for pitcher Pat Zachry, minor league outfielder Steve Henderson, infielder Doug Flynn, and minor league outfielder Dan Norman.[27][28]

Cincinnati Reds (1977–1982)

[edit]

Seaver went 14–3 with the Reds and won 21 games in 1977, including an emotional 5–1 victory over the Mets in his return to Shea Stadium. Seaver struck out 11 batters during the return game and also hit a double. He also received a lengthy ovation at the All-Star Game, held in New York's Yankee Stadium. His departure from New York sparked sustained negative fan reaction, as the Mets became the league's worst team, finishing in last place the next three seasons. Combined with the Yankees' resurgence in the market, attendance dipped during the 1978 New York Mets season and plunged during the 1979 New York Mets season to 9,740 per game. M. Donald Grant was fired after the 1978 season, and Joe McDonald was fired after the 1979 season following a sale of the team to publishing magnate Nelson Doubleday, Jr.[29] In a sardonic nod to the general manager, Shea Stadium acquired the nickname "Grant's Tomb".[30]

After having thrown five one-hitters for the Mets, including two games in which no-hit bids were broken up in the ninth inning, Seaver recorded a 4–0 no-hitter for the Reds in 1978 against the St. Louis Cardinals on June 16 at Riverfront Stadium.[31] It was the only no-hitter of his professional career.[32]

He led the Cincinnati pitching staff in 1979, when the Reds won the Western Division, and again in the strike-shortened 1981 season, when the Reds had the best record in the major leagues. In the latter season, Seaver, with his sterling 14–2 performance, was a close runner-up to Fernando Valenzuela for the 1981 Cy Young Award. (Seaver had finished third and fourth in two other previous years.) In 1981, during one of his two losses, Seaver recorded his 3,000th strikeout against Keith Hernandez of the St. Louis Cardinals. Then in 1982 he suffered through an injury-ridden campaign, finishing the season 5–13.[33]

In six seasons with the Reds, Seaver was 75–46 with a 3.18 earned run average and 42 complete games in 158 starts.[33]

Return to Mets (1983)

[edit]On December 16, 1982, Seaver was traded back to the Mets, for Charlie Puleo, Lloyd McClendon, and Jason Felice.[4] On April 5, 1983, he tied Walter Johnson's major league record of 14 Opening Day starts, shutting out the Philadelphia Phillies for six innings in a 2–0 Mets win.[34] However, he posted a subpar 9–14 record that season.[33]

The Mets exercised an option on Seaver's contract worth $750,000 for the 1984 season.[35] Overall, in 12 seasons with the Mets, Seaver was 198–124 with a 2.57 earned run average in 3,045 innings with 171 complete games, winning three Cy Young awards, the 1969 World Series and the 1967 NL Rookie of the Year Award.[33]

Chicago White Sox (1984–1986)

[edit]On January 20, 1984, the Chicago White Sox claimed Seaver from the Mets in a free-agent compensation draft.[4] The Mets, especially general manager Frank Cashen, incorrectly assumed that no one would pursue a high-salaried, 39-year-old starting pitcher and left him off the protected list.[36]

Seaver pitched two and a half seasons in Chicago and recorded his last shutout on July 19, 1985, against the visiting Indians. In an anomaly, Seaver won two games on May 9, 1984; he pitched the 25th and final inning of a game suspended the day before, picking up the win in relief against the Milwaukee Brewers, before starting and winning the day's regularly scheduled game, also facing the Brewers.[37][38]

On August 4, 1985, Seaver recorded his 300th victory at Yankee Stadium over the Yankees, throwing a complete game 4–1 victory, with Mets announcer Lindsey Nelson in the booth.[39][40]

Seaver started on Opening Day for the 16th and final time of his career in 1986.[41] In three seasons with the White Sox, Seaver was 33–28 with a 3.67 earned run average and 17 complete games in 81 appearances.[33]

Boston Red Sox (1986)

[edit]The White Sox traded Seaver to the Boston Red Sox for Steve Lyons in mid-season.[4] Seaver's 311th and final win came on August 18, 1986, against the Minnesota Twins.

A knee injury prevented Seaver from appearing against the Mets in the World Series with the Red Sox, but he received among the loudest ovations during player introductions prior to Game 1. Roger Clemens attributes the time he shared with Seaver as teammates in 1986 as instrumental in helping him make the transition from thrower to pitcher. The Red Sox did not offer Seaver a contract to his liking for the 1987 season. His 1986 salary was $1 million; the Red Sox offered $500,000, which Seaver declined. When no new contract agreement was reached, Seaver was granted free agency on November 12, 1986.[4]

Seaver was 5–7 with a 3.80 earned run average in 16 starts with Boston in 1986.[33]

In 1987, the Mets starting rotation was decimated by injury and they sought help from Seaver. Though no contract was signed, Seaver joined the club on June 6, and was hit hard in an exhibition game against the Triple-A Tidewater Tides on June 11. After similarly poor outings on June 16 and 20, he announced his retirement, saying that, "there were no more pitches in this 42-year-old arm that were competitive. I've used them all up."[42]

Career overall

[edit]Only Seaver and Walter Johnson have 300 wins, 3,000 strikeouts, and an earned run average under 3.00.[43] Seaver's 16 Opening-Day starts are a MLB record.[24] At the time of his retirement, he was third on MLB's all-time strikeout list (3,640), trailing only his former teammate Nolan Ryan and Steve Carlton; he currently ranks sixth all time. Seaver is tied with Ryan for the seventh-most shutouts in MLB history (61).[44] His feat of striking out ten consecutive batters has only been matched once, by Aaron Nola in 2021.[45] He also holds the record for consecutive 200-strikeout seasons with nine (1968–1976).[44]

Seaver could also help himself at the plate. A decent hitter and proficient bunter, Seaver hit 12 home runs during his career, along with a relatively solid lifetime batting average, for a pitcher, of .154.[33]

| Category | W | L | PCT | ERA | G | GS | CG | SHO | SV | IP | H | ER | R | HR | BB | SO | WP | HBP | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 311 | 205 | .603 | 2.86 | 656 | 647 | 231 | 61 | 1 | 4782.2 | 3971 | 1521 | 1674 | 380 | 1390 | 3640 | 126 | 76 | [33] |

Awards and honors

[edit]

The Mets retired Seaver's uniform number 41 in 1988 in a Tom Seaver Day ceremony, making him the franchise's first player to be so honored.[46]

Seaver was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on January 7, 1992, with the then-highest percentage of votes with 98.84%. He was named on 425 out of 430 ballots. Three of the five ballots that had omitted Seaver were blank, cast by writers protesting the Hall's decision to make Pete Rose ineligible for consideration. One ballot was sent by a writer who was recovering from open-heart surgery and failed to notice Seaver's name. The fifth "no" vote was cast by a writer who said he never voted for any player in their first year of eligibility.[47] Seaver is one of two players enshrined in the Hall of Fame with a Mets cap on his plaque, along with Mike Piazza. He was also inducted into the New York Mets Hall of Fame,[46] the Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame,[48] and the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame.[49]

In 1999, Seaver ranked 32nd on Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players,[50] the only player to have spent a majority of his career with the Mets to make the list. In 2016, ESPN.com ranked Seaver 34th on its list of the greatest MLB players,[51] while The Athletic ranked him the 41st-greatest player in 2020.[52]

On September 28, 2006, Seaver was chosen as the "Hometown Hero" for the Mets franchise by ESPN.[53] Seaver made a return to Shea Stadium during the "Shea Goodbye" closing ceremony on September 28, 2008, where he threw out the final pitch in the history of the stadium to Piazza.[54] Along with Piazza he opened the Mets' new home, Citi Field with the ceremonial first pitch on April 13, 2009.

The 2013 Major League Baseball All-Star Game was dedicated to Seaver. He concluded the introduction of the starting lineup ceremonies by throwing out the ceremonial first pitch. Mets player David Wright participated.[55] In 2019, the New York City renamed the street outside Citi Field from 126th Street to Seaver Way and changed the ballpark's address to 41 Seaver Way,[56][57] a salute of the number he wore throughout his career.[58]

In 2017, Seaver was awarded the Bob Feller Act of Valor Award as the Hall of Fame recipient.[59]

On April 15, 2022, at their home opener against the Arizona Diamondbacks, the Mets unveiled a 10-foot statue of Seaver in front of Citi Field.[60]

Broadcasting career

[edit]

Seaver's television broadcasting experience dated back to his playing career, when he was invited to serve as a World Series analyst for ABC in 1977 and for NBC in 1978, 1980, and 1982. Also while an active player, Seaver called the 1981 National League Division Series between Montreal and Philadelphia and that year's National League Championship Series alongside Dick Enberg for NBC.[61]

After retiring as a player, Seaver worked as a television color commentator for the Mets, the New York Yankees, and with Vin Scully in 1989 for NBC. Seaver replaced Joe Garagiola[62] as NBC's lead baseball color commentator, which led to him calling the 1989 All-Star Game and National League Championship Series. He worked as an analyst for Yankees' telecasts on WPIX from 1989 to 1993 and for Mets' telecasts on WPIX from 1999 to 2005, making him one of three sportscasters to be regular announcers for both teams; the others are Fran Healy and Tim McCarver.

Personal life and death

[edit]Seaver married Nancy Lynn McIntyre on June 9, 1966, in Jacksonville, Florida during Seaver's Triple-A stint. They were the parents of two daughters, Sarah and Annie. They lived in Calistoga, California, where Seaver started his own 3.5-acre (1.4 ha) vineyard, Seaver Family Vineyards,[63] on his 116-acre (47 ha) estate, in 2002.[64] His first vintage was produced in 2005.[65][66][67] He presented his two cabernets, "Nancy's Fancy" and "GTS," at an April 2010 wine-tasting event in SoHo, to positive reviews.[68]

At the annual Hall of Fame induction, Seaver was part of a "club" which included Bob Gibson, Sandy Koufax, and Steve Carlton which annually brought a bottle of wine to share that dinner held at The Otesaga Hotel.[69][70]

Seaver was an opponent of the Vietnam War, and spoke out against it leading up to the 1969 World Series.[71][72]

In 2013, it was reported that Seaver suffered from memory loss, not even remembering long-term acquaintances and experiencing symptoms of "sleep disorder, nausea, and a general overall feeling of chemical imbalance".[73][74] According to former teammate Bud Harrelson, Seaver was "otherwise doing well".[75] On March 7, 2019, Seaver's family announced that he had dementia and was retiring from public life.[76]

Seaver died in his sleep as a result of complications from Lewy body dementia and COVID-19 on August 31, 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic in California. He was 75.[18][44]

See also

[edit]- DHL Hometown Heroes

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual shutout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career WHIP leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career shutout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball individual streaks

- List of Major League Baseball no-hitters

- List of Major League Baseball single-game strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball retired numbers

- List of celebrities who own wineries and vineyards

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Seaver received 98.84%. This was subsequently surpassed in 2016 by Ken Griffey Jr. with 99.32% and Mariano Rivera in 2019 with 100%. Derek Jeter also received 99.7% of the vote in 2020.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Tom Seaver (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

- ^ "Tom Seaver, Class of 2003". Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012.

- ^ Blum, Ronald (September 3, 2020). "Marine veteran Tom Seaver, heart and mighty arm of Miracle Mets, dies at 75". Marine Corps Times. Springfield, VA. Associated Press.

- ^ a b c d e f "Tom Seaver Trades and Transactions". Baseball Almanac.

- ^ a b Golenbock, Peter (2002). Amazin': The Miraculous History of New York's most Beloved Baseball Team. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 187. ISBN 0-312-30992-9.

- ^ Lukehart, Jason (February 24, 2016). "Tom Seaver was almost on the Cleveland Indians instead of the Mets". Let's Go Tribe. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ "Tom Seaver Minor Leagues Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference.

- ^ "1967 All-Star Game Box Score, July 11". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ "1967 Awards Voting". Baseball-Reference. January 1, 1970. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ "Tom Seaver, Hall of Fame pitcher and Mets legend, dies at 75". ABC7 New York. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Simon, Andrew (May 24, 2018). "Most Opening Day starts by a pitcher". MLB.com. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ "1968 New York Mets Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Madden, Bill. "Madden: Remembering Willie McCovey and the time Tom Seaver figured out how to strike out the man known as 'Stretch'". New York Daily News. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Bamberger, Michael (July 8, 2009). "Forty years ago, little-known Qualls spoiled Seaver's bid at perfection". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ Raylesberg, Alan. "July 9, 1969: Tom Seaver's near-perfect game". Society for American Baseball Research (SABR Games Project).

- ^ "Tom Seaver". Hickok Belt. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ Leggett, William (December 22, 1969). "Tom Seaver: 1969 Sportsman of the Year". Sports Illustrated. p. 32. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ a b "Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Seaver passes away at age 75". National Baseball Hall of Fame. September 2, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Muder, Craig. "Tom Seaver strikes out 10 straight Padres". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Box Score of 19-strikeout game, April 22, 1970". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Nowlin, Bill; Tan, Cecilia. "April 29, 1986: Roger Clemens becomes first pitcher to strike out 20 in nine innings". Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "1970 National League pitching leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Durso, Joseph (November 4, 1971). "Cubs' Jenkins Voted Cy Young Award". The New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Dittmeier, Bob (September 2, 2020). "Seaver, greatest Met of all time, dies at 75". MLB.com. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Verducci, Tom (October 23, 2019). "Tom Seaver and the Enduring Hope of the 1969 Mets". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Madden, Bill (June 17, 2007). "The true story of The Midnight Massacre – How Tom Seaver was run out of town 30 years ago". Daily News. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Madden, Bill (June 17, 2007). "The true story of The Midnight Massacre". New York Daily News. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Keith, Larry (June 27, 1977). "Tom Terrific arms the Red arsenal". Sports Illustrated. p. 22. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ "New York Mets Attendance Records". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Mallozzi, Vincent M. (June 18, 2006). "Recalling the Time of the Signs at Shea". The New York Times. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ "Tom's terrific!". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. June 17, 1978. p. 11.

- ^ Wolf, Gregory. "June 16, 1978: Tom Terrific! Seaver tosses only no-hitter". Society for American Baseball Research (SABR Games Project).

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Tom Seaver Stats". Baseball-Reference.

- ^ Wulf, Steve (April 18, 1983). "It was a terrific homecoming". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (November 3, 1983). "The 'Unofficial' Pitching Coach". The New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Durso, Joseph (January 21, 1984). "White Sox Take Seaver; Mets Are Stunned". The New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ "Milwaukee Brewers at Chicago White Sox Box Score: May 8, 1984". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ "Milwaukee Brewers at Chicago White Sox Box Score: May 9, 1984". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Neff, Craig (August 12, 1985). "Tom takes a giant step". Sports Illustrated. p. 14. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ Harper, John (August 5, 1985). "Win No. 300 for Seaver meant to be". Daily Record. p. 27. Retrieved October 24, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Simon, Andrew (February 18, 2019). "Most Opening Day starts by a pitcher". MLB.com. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Lang, Jack. "Pitches 'Used All Up,' Seaver Calls It Quits". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Oster, Patrick (September 2, 2020). "Tom Seaver, New York Mets Hall of Fame Pitcher, Dies at 75". Bloomberg News. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c Madden, Bill (September 2, 2020). "Tom Seaver, the greatest Met of all time, dies at 75". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Kelly, Matt; Langs, Sarah (August 2, 2020). "Most consecutive strikeouts by pitcher". MLB.com. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Mets Retired Numbers". MLB.com. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ "Ripken is a 100% Hall of Famer". USA Today. December 22, 2006.

- ^ "Donovan good fit for Marine sports hall". The Baltimore Sun. August 6, 2004.

- ^ Nightengale, Bobby (September 2, 2020). "Cincinnati Reds Hall of Famer Tom Seaver dies at 75". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Boswell, Thomas (May 9, 1999). "Baseball's All-Time List of Greats Really Grates". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "MLB: All-Time #MLBRank, Nos. 40-31". ESPN. July 21, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Posnanski, Joe (February 15, 2020). "The Baseball 100: No. 41, Tom Seaver". The Athletic. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ ""DHL Presents Major League Baseball Hometown Heroes" winners revealed". MLB.com. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Robinson, Joshua (September 28, 2008). "Immersed in Gloom, a Farewell to Shea Still Enchants". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Terrific time: Tom Seaver has some fun throwing the ceremonial first pitch at All-Star Game". Newsday. July 16, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Citi Field Street Renamed in Honor of 'Miracle Mets' Pitcher Tom Seaver". CBS News. June 27, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ Madden, Bill (June 27, 2019). "Mets' '41 Seaver Way' ceremony was a welcome distraction this week". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, Houston (June 28, 2019). "Morning Briefing: Mets honor Tom Seaver". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ "2017 Bob Feller Act of Valor Award". October 4, 2017.

- ^ Overmyer, Steve; Dias, John (April 15, 2022). "Tom Seaver statue unveiled outside Citi Field before Mets' home opener". CBS News. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ King, Norm. "October 11, 1981: Steve Rogers leads Expos to NLCS". Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Martzke, Rudy (January 31, 1989). "NBC plans innovative ways to fill baseball void". USA Today. p. 3C.

- ^ "Seaver Vineyards". Archived from the original on September 16, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ Asimov, Eric (December 28, 2005). "Warming Up in the Vineyard, Tom Terrific". The New York Times.

- ^ Lindbloom, John (August 26, 2010). "St. Helena gets a taste of Seaver and Sinatra". St. Helena Star. Napa, California. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ James, Marty (October 8, 2009). "Tom's terrific life after baseball". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ Madden, Bill (May 26, 2017). "Mets legend Tom Seaver says pitchers should 'learn to pitch' or they won't age well". New York Daily News. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ Belson, Ken (April 26, 2010). "Seaver's Tales of Wine and Roses". The New York Times.

- ^ Fauchald, Nick (March 11, 2005). "Wine Talk: Tom Seaver". Wine Spectator.

- ^ Frank, Mitch (September 2, 2020). "Tom Seaver, Hall of Fame Pitcher and Napa Vintner, Dies at 75". Wine Spectator.

- ^ Candaele, Kelly; Dreier, Peter (September 11, 2020). "Tom Seaver's Major League Protest". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "Tom Seaver Says U. S. Should Leave Vietnam". The New York Times. October 11, 1969. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ Madden, Bill (March 15, 2013). "Mets great and Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Seaver feeling better, winning his battle with Lyme disease". New York Daily News.

- ^ Madden, Bill (July 9, 2013). "At 2013 MLB All-Star Game, Mets legend Tom Seaver, fighting back from Lyme disease and memory loss, ready for pitch". New York Daily News.

- ^ Marcus, Steven (June 10, 2017). "40 years ago, the Mets did the unthinkable: They traded Tom Seaver". Newsday. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017.

- ^ Adler, David (March 7, 2019). "Hall of Famer Seaver to retire from public life". MLB.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Tom Seaver at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Tom Seaver at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Tom Seaver at IMDb

- 1944 births

- 2020 deaths

- Alaska Goldpanners of Fairbanks players

- American winemakers

- Baseball players from Fresno, California

- Baseball players from Napa County, California

- Boston Red Sox players

- Chicago White Sox players

- Cincinnati Reds players

- Cy Young Award winners

- Deaths from the COVID-19 pandemic in California

- Deaths from dementia in California

- Deaths from Lewy body dementia

- Fresno City Rams baseball players

- Jacksonville Suns players

- Major League Baseball broadcasters

- Major League Baseball pitchers

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- Major League Baseball Rookie of the Year Award winners

- Military personnel from California

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- National League All-Stars

- National League ERA champions

- National League strikeout champions

- National League (baseball) wins champions

- New York Mets announcers

- New York Mets players

- New York Yankees announcers

- People from Calistoga, California

- United States Marine Corps reservists

- USC Trojans baseball players