Hull Paragon Interchange

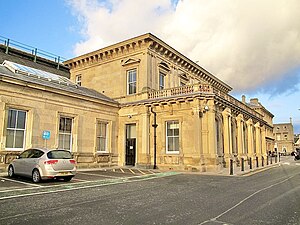

The original station entrance | |||||

| General information | |||||

| Location | Kingston upon Hull England | ||||

| Coordinates | 53°44′37″N 0°20′46″W / 53.7435°N 0.3460°W | ||||

| Grid reference | TA090287 | ||||

| Managed by | TransPennine Express | ||||

| Platforms | 7 | ||||

| Other information | |||||

| Station code | HUL | ||||

| Classification | DfT category B | ||||

| History | |||||

| Opened | 1847 | ||||

| Passengers | |||||

| 2017/18 | |||||

| 2018/19 | |||||

| 2019/20 | |||||

| 2020/21 | |||||

| 2021/22 | |||||

| |||||

Hull Paragon Interchange is a transport interchange providing rail, bus and coach services located in the city centre of Kingston upon Hull, England. The G. T. Andrews-designed station was originally named Paragon Station, and together with the adjoining Station Hotel, it opened in 1847 as the new Hull terminus for the growing traffic of the York and North Midland (Y&NMR) leased to the Hull and Selby Railway (H&S).[1] As well as trains to the west, the station was the terminus of the Y&NMR and H&S railway's Hull to Scarborough Line. From the 1860s the station also became the terminus of the Hull and Holderness and Hull and Hornsea railways.

At the beginning of the 20th century the North Eastern Railway (NER) expanded the trainshed and station to the designs of William Bell, installing the present five arched span platform roof. In 1962 a modernist office block Paragon House was installed above the station main entrance, replacing a 1900s iron canopy; the offices were initially used as regional headquarters for British Rail.

A bus station was erected adjacent to the north of the station in the mid 1930s. In the early 2000s plans for an integrated bus and rail station were made, as part of a larger development including a shopping centre; St Stephen's shopping centre, a hotel, housing, and music and theatre facilities. The new station, named "Paragon Interchange" opened in September 2007, integrating the city's railway and bus stations under William Bell's 1900s trainshed.

The station is currently operated by TransPennine Express, which provides train services along with Northern Trains, Hull Trains and London North Eastern Railway.

Paragon railway station

Background

In 1840 the Hull and Selby Railway opened the first railway line into Hull, terminating at a passenger and goods terminal, Manor House Street station, adjacent to the Humber Dock, near the old town. Subsequently, the Hull and Selby Railway entered into working arrangements with the Manchester and Leeds Railway and then the York and North Midland Railway. In 1845 an Act of Parliament enabled the York and North Midland and/or the Manchester and Leeds to take a lease of the company with an option to buy the line at a later date – only the York and North Midland was subsequently active. In 1846 the Hull and Selby completed its Bridlington branch which connected from a junction at Dairycoates near Hull to a line the York and North Midland was building from Bridlington to Seamer, connecting to its York to Scarborough Line, forming a railway route from Hull to Scarborough on the east coast.[2]

First railway station, hotel and branches (1848)

In 1846 the York and North Midland and Manchester and Leeds railways began proceedings to create a new terminal station and connecting branch line in Hull.[3][4] The York and North Midland (Hull Station) Act 1847 was subsequently passed.[n 1]

The new station had the advantage of being better situated for travellers, and allowed the old station to be used exclusively for freight traffic. In addition the Hull and Selby company were keen to attract the investment in a new station from the leaseholders, as the capital investment was likely to increase the permanence of the relationship with the lessors.[6]

The branches to the station were constructed off the Bridlington branch: a branch turning north-east close to the line's crossing of the Hessle Road;[map 1][7] and a branch turning south-east at 'Cottingham Junction' near to Haverflatts farm;[map 2][8] the two branches met at a junction 0.5 miles (0.8 km) roughly west of the new station.[7] In addition a new connecting chord was made from the Hull and Selby Line,[map 3] to the Bridlington branch,[map 4] allowing direct through running from the west into the new station.[9] The station was located on the western edge of the growing Georgian town, and took its name from "Paragon Street".[10]

Construction contracts had been signed by early 1847, before the bill had been formally passed.[n 2] The station opened in 1847 without any notable ceremony.[11]

The station and hotel were both in the Italian Renaissance style, with both Doric and Ionic order elements; the facades show inspiration from the interior courtyard of the Palazzo Farnese. The main station building was aligned east–west, south of the tracks, facing onto Anlaby Road – a two-storey centrally located booking hall was entered via a small porte-cochère,[map 5] and flanked by eleven bay wide single storey wings, with two storey three bay buildings on either end, one a parcels office, the other the station master's house.[11][12][10] The train shed contained five tracks and two platforms, each 30 feet (9.1 m), covered with a three span iron roof.[map 6] The station site was nearly 2.5 acres (1.0 ha).[n 3][11]

The hotel was in a similar style to the station, located at the east end of the station with its main façade and entrance facing east.[map 7] It was completed in 1849 as a three-storey building, nine bays wide, of area 120 by 130 feet (37 by 40 m). The centre of the building contained a 650 feet (200 m) square lightwell with ground glass roof.[13][12][10]

Architect for both buildings was G. T. Andrews, and represent his last major commission. The station and hotel were described by some contemporaries as "Hudson's Folly", who thought the scale of the development too great;[14] the station was the largest built in England to that time associated with a railway station.[10] By the time of completion of the station hotel George Hudson, chairman of the York and North Midland was in disgrace after his fraudulent dealings had been discovered.[10] The hotel's official opening ceremony took place on 6 November 1851.[11]

Additional facilities at the station also included a locomotive house, on the west end of north side of the main shed;[map 8] a coal depot to the north-west;[map 9] and a turntable.[15] A new engine shed was constructed in the 1860s, and a 20 engine shed was constructed in the mid 1870s.[16][n 4]

In 1853 Queen Victoria visited the town, and the use of the station hotel given to the corporation for the accommodation of the royal party; a throne room was created on the first floor, and the royal household accommodated on the second. The royal party including the Queen, Albert, Prince Consort and five royal children arrived on the Royal Train on 13 October 1853 at Paragon Station. The visit concluded with a dinner at the hotel on 14 October.[18]

NER period (1854–1923)

In 1853 the Victoria Dock Branch Line had opened in Hull, connecting the Victoria Dock and a number of stations in Hull on a circular route around the outskirts of the town; the line connected to the existing network at junctions 0.5 miles (0.8 km) west of the station.[19][20] This line was doubled in mid 1864 and brought more trains into Paragon: from the Hull and Hornsea Railway (opened 1864); and from the Hull and Holderness Railway (opened 1854[21]) via a connecting chord to the Victoria Dock Branch Line.[22] Further developments in the 1860s created additional or shorted routes into Paragon; the York to Beverley Line was completed in 1865 with the opening of the Market Weighton to Beverley section;[23] the Hull and Doncaster Branch to south Yorkshire in 1869;[24] and the line to Leeds extension was completed, extending the line from Hull to Leeds to the city centre, and allowing through running westward.[23]

In 1873 the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway obtained running powers into Hull, and passenger trains from that company running to Paragon from August.[25] In 1898/9 the Hull and Barnsley Railway and the NER began work towards constructing a joint dock in Hull (see Alexandra Dock); as part of this cooperation between the two companies the H&BR gave the NER running powers over its line in Hull, and the NER allowed the H&BR to run into and use Paragon station.[26]

The growth of traffic was accommodated in the mid 1870s by adding a third middle platform to the trainshed; the outer platforms were also lengthened beyond the shed, and short bay platforms added on either side. The cross platform was widened at the expense of the length of the main platforms; the booking office and parcels offices swapped positions, and the middle portico walled up to create greater enclosed space.[27][28][29] In 1884/5 the hotel was also expanded, adding room at first floor level by extending westward across a concourse entrance.[27] In 1887 a station canopy was added over the ends of the departure (southside) platform that extended beyond the shed.[28][n 5]

In addition to the standard facilities the increased emigration to the United States in the 19th century led to the construction of an emigrant station,[map 11] south-west of the main station, in part due to concerns over public health dangers, such as cholera; the station also enabled more efficient handling of the large numbers of emigrants. The station rooms were built in 1871 to the designs of Thomas Prosser, and extended 1881. Because of its historical significance the building is now grade II listed.[30][31][32][33]

An extensive enlargement of the station was authorised by the NER board in 1897, as part of the extension programme the station's engine shed facilities were transferred to a new site at Botanic Gardens;[34][16][n 6] the transfer was complete by 1901, and in 1902 work began on the rebuilding of the station; the expansion of the site was northwards towards Colliers Street, and required purchases and demolition of houses south of the street.[27][28][36]

The main station was enlarged to a design by NER architect William Bell. The extension included a new five span steel platform roof, with a two span roof over the concourse, built by the Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Co.,[map 6] with the offices resited to the east end of the station, facing the station concourse, together with the adjacent Hotel. Half of the new office spaces was taken up by a tiled booking office, with wooden booking windows, and architectural detailing in faience.[map 12] The booking office's main entrance faced Paragon Square (Ferensway) accessed under a large iron made porte-cochère.[12][37][38][map 13] The enlarged station opened 12 December 1904.[39] An additional range of buildings was built c. 1908 to the south-east of the station, to provide stock rooms for the hotel.[40][41][map 14][n 7]

As built the station had nine platforms under the four southernmost spans of the roof; the northernmost span had facilities for special goods, such as cars and horses, and was screened off from the other four;[42] it was served by platform 1, known as the fish dock or fish platform, which was also used for fish.[43] The southern bay platforms, and 1887 platform roof was retained for a total of fourteen passenger platforms; platforms 1–9 also received low level roofs outside the main shed.[44] The original station offices were retained and used as waiting rooms and parcel offices.[45]

In 1904 the station signalling system was converted to an electro-pneumatic power signalling system – the station had two signal boxes: Paragon Station box was a 143 lever box and was located at the end of platforms 1 and 2;[map 15] Park Street box, with 179 levers was located 714 feet (218 m) west of the station.[46][map 16]

In World War I, the station hosted a rest station and canteen for servicemen.[47]

On 5 March 1916 during a First World War Zeppelin raid that killed 17, a bomb blast blew out the glass in the station roof.[48]

LNER period (1923–1948)

From 1924 passenger trains running from the Hull and Barnsley Line became able to run into Paragon station with the construction of a connecting chord between the NER and H&BR networks in north-west Hull.[map 17] The H&BR's Cannon Street station closed in the same year.[49]

On 14 February 1927 it was the site of a head-on train collision (see Hull Paragon rail accident) in which 12 passengers were killed and 24 seriously injured, caused by a signalling error.[50][51]

In 1931–32 the hotel was internally revamped, and expanded by the addition of an extra storey of rooms on the roof, replacing staff bedrooms; and by cement rendered wing on either side of the main entrance; an art deco entrance onto the station concourse was also added.[10][52] A railway museum was established by Hull Museums director Thomas Sheppard in the station in 1933.[53][54]

In 1935 the decision was made to resignal the station and approaches, replacing the 1904 electro-pneutmatic power signalling system with an electrically operated system. "Park Street" and "Paragon station" signal boxes were to be replaced with a single box; the running lines out of the station, including those controlled by the West Parade signal box,[map 18] were to be track circuited.[46][n 8] The system was an early British example of electrical interlocking. 48 points were controlled, using thumb switches in the signal box.[55] Power supply was from the Hull Corporation at 400 V 50 Hz three phase, with a backup generator powered by a 28 horsepower (21 kW) Petter oil-engine. The main external system was electrified at 110 V AC, with shunt signals at 100 or 55 V AC; the point motors, previously electro-pneumatically operated were retained, with a 50 cubic feet (1.4 m3) per hour 80 pounds per square inch (550 kPa) max. pressure compressor system, duplicated for redundancy.[56] Signalling was electric lamp backlit.[57] The Westinghouse Brake and Signal Company Ltd was the main supplier of the equipment.[58] A new signal box was installed,[map 19] a LNER type 13, resembling in architectural design the Southern Railway's Streamline Moderne signal boxes, but with square corners.[59]

During the Hull Blitz of 1941 the station received direct hits on the night of 7 May, with many incendiary bombs hitting the roof. The signal box was badly damaged when a parachute mine exploded nearby[60] during the same night the station's small railway museum was destroyed by fire.[54]

BR period (1948–1995)

The main entrance canopy was replaced by an office building Paragon House in 1962.[12][61][map 13] The building was originally used as a regional headquarters for British Rail, but was unused in later years.[62]

In 1965 the Newington branch which had been used by trains running from west of Hull to Bridlington and beyond was closed and replaced by a new chord near Victoria crossing.[map 20][map 21][63] The roofs sheltering platforms 1–9 outside the main shed were removed in the 1970s.[64]

In the 1980s a new "travel centre" (booking and information office) was added on the station concourse. The body of the building was faced with light sandstone, with lighting via semicircular arched windows, and an approximately barrel roofed skylight. In the same period a clerestory roofed waiting room was added at the head of the station platforms, an architectural homage to both Victorian trainshed roofs and clerestory carriages.[65]

After the privatisation of British Transport Hotels in the 1980s the "Royal Station Hotel" was renamed Royal Hotel.[62]

Post privatisation period (1995–present)

In 1990 the hotel was gutted by a fire,[66][67] the interior was rebuilt and the hotel re-opened in 1992.[12]

In 2000 outline planning permission was given for a transport interchange and shopping and leisure complex near Ferensway, Hull; in 2001 full planning documents were submitted for works on a 42-acre (16.8 ha) site included a new shopping arcade development incorporating a hotel and car parking facilities; a transport interchange incorporating the station; as well as landscaping, setting out of streets, a petrol station and a housing development.[68] The development also included new facilities for the Hull Truck Theatre and the Albemarle Music Centre.[69] The shopping development is known as St Stephen's shopping centre.[70] The interchange fully opened on 16 September 2007.[71][72]

Features of the railway 2007 station redevelopment include a new canopy to the Ferensway entrance;[70][map 13] the "Paragon House" office block was demolished as part of the redevelopment.[62] The former station booking office area was restored, and in 2009 opened as a community area.[73] From 2009 a mobility scooter hire service was provided at the station.[74] The interior of the booking office is used (2011) as a branch of WH Smith.[62]

The new transport interchange was officially opened by the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh when they unveiled a plaque on 5 March 2009 after arriving at the station on the Royal Train.[75]

A £65,000 bronze statue of Hull resident poet Philip Larkin by Martin Jennings was unveiled on the concourse of Hull Paragon Interchange on 2 December 2010, marking the 25th anniversary of the poet's death. The statue was located near to the entrance to the Station Hotel, a favoured watering place of the poet.[76][77] In 2011, an additional five slate roundels containing inscriptions of Larkin's poems were installed in the floor around the statue;[78] and in 2012 a memorial bench was installed around a pillar near the statue.[79]

In February 2017 a full-size model of the Gipsy Moth aircraft used by Amy Johnson to fly solo from Britain to Australia, created over a six-month period by inmates of Hull Prison, was put on display at the station.[80] This remained throughout the City of Culture but moved to the adjacent St Stephen's shopping centre in March 2018.[81] The station underwent a revamp during 2017, with a £1.4 million investment providing a new waiting area and more retail units.[82]

Bus and coach station

History and description

The bus concourse in 2010 | |

| General information | |

| Location | Ferensway, Hull |

| Bus stands | 38 bus stands + 4 coach stands |

| Bus operators | East Yorkshire Megabusplus National Express Stagecoach in Hull Stagecoach in Lincolnshire |

| History | |

| Opened | 16 September 2007 |

A bus station was built adjacent to Paragon station in 1935, at a cost of £55,000 on land freed by slum clearance.[83]

A new bus station integrated with the main railway station was developed and constructed in the first decade of the 21st century. (see also §Paragon station post privatisation.)

Hull Paragon Interchange opened on Sunday 16 September 2007 combining rail and bus station services on a single site. The bus terminal has 38 bus and 4 coach stands, replacing a separate 'island' bus station;[71][84] the site of the former Hull Bus Station, adjacent to the north of the railway station now forms part of the St Stephen's shopping centre.[85] The bus ranks are located at the north of the station, in a "saw-tooth" arrangement. The entrance to the station is from Ferensway, and a reversing roundabout was provided at the west end of the station.[86][87] The station has approximately 1,700 bus departures per day (September 2010).[87] The area under the northernmost span of the trainshed roof was converted into the concourse and queueing area for the bus station.[62][map 22]

Services

Bus services

Bus services run from the station to all areas of Hull, as well as to the East Riding and North Lincolnshire and as far out as York, Leeds, Grimsby and Scunthorpe on some express services. Most city bus services are operated by Stagecoach East Midlands, whilst East Yorkshire is the main bus company for services to the East Riding. Services to North East Lincolnshire are operated by Stagecoach in Lincolnshire and Stagecoach Grimsby-Cleethorpes. Former smaller operators who used the Interchange included Alpha Bus and Coach[citation needed] and CT Plus Yorkshire.[88]

Rail services

Hull Paragon is managed by TransPennine Express, serving mainly its North TransPennine route and several Northern Trains routes. Additional services are provided by Hull Trains and London North Eastern Railway.

TransPennine Express operates a Monday-Saturday service of one train per hour to and from Manchester Piccadilly via Leeds, and one early morning train to Manchester Airport per day. Direct services to and from Manchester are less frequent after 7pm. In May 2017, a later direct service to Manchester Piccadilly was introduced. On Sunday, a similar service runs at a reduced frequency (approximately every one to two hours), starting later and finishing earlier, with no direct service to Manchester Airport.[89][90][91] All services are operated by Class 185 Desiros.

Northern Trains's weekday service consists of two trains per hour from Hull to Bridlington, made up of one semi-fast service and one stopping service, with one service per hour continuing through to Scarborough. Northern also operates one fast service per hour to Sheffield via Goole plus a second local stopping train each hour to Doncaster and hourly to both York and Halifax via Leeds. At peak times there are additional services between Hull and Beverley, calling at Cottingham. Weekend running is similar, but with reduced frequencies on some routes and all services finishing earlier. Most fast services from Sheffield call at Hull before continuing to Scarborough, although some timetables show these services as separate rather than continuous.[92] All services are typically operated by a mixture of Class 150 Sprinters, Class 155 Sprinters and Class 158 Express Sprinters.

Hull Trains operates a weekday service of seven trains in each direction to London King's Cross. At weekends this service is reduced, with 6 trains on Saturday, and 5 on Sunday. However, Sunday services were be increased to 6 trains in each direction from December 2017. Every day one train to London starts at Beverley progressing to Hull in the early morning, with one late night train from London terminating at Beverley after Hull.[93][91] All services are currently operated by Class 802 Paragons.

London North Eastern Railway operates one train per day Monday-Saturday in each direction between Hull and London King's Cross, with the morning service departing Hull at 06:58 and the evening service arriving at 20:05 in Hull, from where it then returns to Doncaster. On Sundays, there is no morning departure with only an evening arrival from London.[94] Each service is operated by a Class 800 Azuma.

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TransPennine Express North TransPennine | Terminus | |||

| Northern Trains Selby line | Terminus | |||

| Terminus | ||||

| Northern Trains Yorkshire Coast line | ||||

| Brough | Hull Trains London – Hull / Beverley |

Terminus | ||

| Cottingham | ||||

| Brough | London North Eastern Railway East Coast Main Line (Limited service) |

Terminus | ||

| Disused railways | ||||

| Terminus | Hull and Selby Railway | Hessle | ||

| Terminus | Hull and Holderness Railway | Hull Botanic Gardens | ||

| Hull and Hornsea Railway | ||||

| Victoria Dock Branch Line | ||||

| Terminus | London and North Eastern Railway (Hull and Barnsley Line) | Springhead Halt | ||

| Future services | ||||

| Doncaster | Northern Connect Sheffield – Hull |

Terminus | ||

| Leeds | TBA Northern Powerhouse Rail |

Terminus | ||

| Doncaster | ||||

Platforms

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2016) |

- Platform 1 – A bay platform. Has been out of use since the mid 1990s. Work is scheduled in July 2020 to bring it back in to use.

- Platform 2 – Northern Trains services on routes to Sheffield from Bridlington or Scarborough or services from York terminating here.

- Platform 3 – TransPennine Express services terminating from Manchester Piccadilly along with Platform 4.

- Platform 4 – TransPennine Express services from Manchester Piccadilly.

- Platform 5 – Northern Trains services terminating from Doncaster and also occasionally used for services from York when platform 2 is in use.

- Platform 6 – Northern Trains services from Beverley or services terminating here from Sheffield.

- Platform 7 – Hull Trains services from/to London King's Cross/Beverley and Northern services from/to Bridlington/Scarborough terminating or from Doncaster/Sheffield. This platform is also used by London North Eastern Railway's limited service to and from King's Cross, with the platform being just about long enough to accommodate a 9-car Azuma.

Naming

The rail station is commonly known as "Paragon station", "Hull Paragon", or just "Hull station". National Rail refers to the station as "Hull" (HUL).

The name comes from the nearby "Paragon Street" which was itself built c. 1802;[95] the name dates back earlier – The Paragon Hotel public house, (now the "Hull Cheese") gave its name to the street, and dates back as far as 1700.[96]

The station was opened as "Hull Paragon Street" 8 May 1848 by the York and North Midland Railway;[97] the NER used the name "Hull Paragon",[97] however the 'Paragon' suffix was inconsistently used over ninety years from opening to 1948.[98]

Since the British Railways period (1948) the officially used name has usually been "Hull", excluded the 'Paragon' suffix.[99][n 9]

The term "Hull (Paragon)" has also been used by Network Rail.[100] Since redevelopment in 2007 the official name has been "Paragon Interchange"; however as of 2012 timetables continued to use "Hull", except when referring to bus services.[99]

The hotel has been known as the "Station Hotel" or "Royal Station Hotel" from its early history;[101] after privatisation in the 1980s the owners renamed it "Royal Hotel".[62] As of 2014, as part of the Mercure Hotels group the hotel's official name is the Mercure Hull Royal Hotel.[102]

In popular culture

The station has been used as a filming location in the film Clockwise,[103] in an episode of Agatha Christie's Poirot "The Plymouth Express"[104] and in the comedy Only Fools and Horses – To Hull and Back.[105]

Notes

- ^ "An Act for enabling the York and North Midland Railway Company to make a Station at Hull, and certain Branch Railways connected with their Railways and the said Station; and for other Purposes" (c. 218, 22 July 1847)[5]

- ^ Fawcett (2001, p. 84) states 1 April 1847, whilst Hitches (2012) gives 1 March 1847

- ^ Sheahan (1864, p. 572) gives ground dimensions of 153 by 125 feet (47 by 38 m) long by wide for the station, which appears erroneous based on the 1856 Ordnance Survey 1:1056 town plans.

- ^ A square shed of approximately 150 feet (46 m) square had been constructed north-west of the original shed, south of St Stephen's church and square by the late 1800s.[17][map 10]

- ^ Note. The 1891 Ordnance Survey 1:500 OS Town plan shows the locations of the supporting columns.

- ^ The station's coal depot was resited to the site of the shed near St Stephens Square.[35][map 10]

- ^ The diagram in Fawcett (2005, Fig.3.7, p.46) notes a bakery and stock rooms, whilst The Engineer & 11 February 1908, p.160, col.3) notes a motor garage and stock rooms. To the west and south of the 1848 front another building was built at around the same time (OS. 1:2500 1893, 1910/1)

- ^ "West Parade" a street between the Park Street and Argyle Street bridges; West Parade Junction was just east of Argyle street bridge, a double diamond crossover (1928), and the point were the Beverley, Hornsea, Withernsea and Selby lines diverged. "West Parade signal box" was just west of the junction and bridge (OS. 1:2500. 1928)

- ^ Since the closure of Cannon Street to passengers in 1924 the station was the only consistently timetabled rail terminus in the city.[99]

References

- ^ Young, Angus (7 July 2015). "Hull Paragon Station gets new stonework facelift". Hull Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ See Hull and Selby Railway, Hull to Scarborough Railway

- ^ "York and North Midland and Manchester and Leeds Railways (Hull Station and Branches)". The London Gazette (20671): 4970–1. 21 November 1846.

- ^ "York and North Midland (Hull Station and Branches)". The London Gazette (20671): 4971–2. 21 November 1846.

- ^ A Collection of the Public General Statutes passed in the Tenth and Eleventh Year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. 1847. p. xxvii.

- ^ MacTurk, G. G. (1970) [1879]. A History of the Hull Railways (reprint). p. 130.

- ^ a b Ordnance Survey. Sheet 240. 1853

- ^ Ordnance Survey. Sheet 226. 1853

- ^ Addyman, John F.; Fawcett, Bil, eds. (2013). A History of the Hull and Scarborough Railway. North Eastern Railway Association. p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f Fawcett 2001, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d Sheahan 1864, p. 572.

- ^ a b c d e Pevsner & Neave 1995, p. 524.

- ^ Sheahan 1864, pp. 572–3.

- ^ Gillett & MacMahon 1980, p. 275.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. 1:1056 Town Plan

- ^ a b Hoole, K. (1986). North Eastern locomotive sheds. p. 222.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. 1:500 Town Plans 1891

- ^ Sheahan 1864, pp. 180–191.

- ^ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 519–20.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. 1852-3. Sheets 226, 240

- ^ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 522–3, 525.

- ^ Tomlinson 1915, p. 606, 612.

- ^ a b Tomlinson 1915, pp. 472, 499, 606, 620.

- ^ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 608–9, 634.

- ^ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 663–4.

- ^ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 718–721.

- ^ a b c Fawcett 2001, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Fawcett 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. Town Plans. 1856, 1:1056; 1891: 1:500

- ^ Historic England. "Former Immigrant Station and Railway Platform (1207714)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Evans, Nicholas J. (1999). "Migration from Northern Europe to America via the Port of Hull, 1848–1914". www.norwayheritage.com. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ Evans, Nicholas J. "A piece of Britain that shall forever remain foreign". BBC. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ Evans, N. J. (2001). "Work in progress: Indirect passage from Europe Transmigration via the UK, 1836–1914". Journal for Maritime Research. 3: 70–84. doi:10.1080/21533369.2001.9668313.

- ^ Goode 1992, p. 36.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. 1:2500. 1893, 1910–1

- ^ Ordnance Survey 1:2500 1893, 1910–11

- ^ Fawcett 2005, pp. 45–50.

- ^ Biddle, Gordon; Nock, Owsald Stephens (1983). The Railway Heritage of Britain. p. 31.

- ^ Tomlinson 1915, p. 761.

- ^ Fawcett 2005, Fig.3.7, p.46.

- ^ The Engineer & 11 February 1908, p.160, col.3.

- ^ Fawcett 2005, p. 48.

- ^ The Engineer & 11 February 1908, p.161, cols.1, 3.

- ^ Fawcett 2005, Figs.3.6 & 3.7, p.46.

- ^ Fawcett 2005, p. 47.

- ^ a b "Paragon Station, Hull, L.N.E.R, is to be resignalled" (PDF). The Engineer. Vol. 159. 3 May 1935. p. 463.

- ^ "Hull's WWI Hospitals and Charities". Kingston upon Hull War Memorial 1914–1918.

- ^ Gillett & MacMahon 1980, p. 376.

- ^ Hoole (1986, pp. 50–51). See also Hull and Barnsley Railway § "As part of the LNER (1923–1948)"

- ^ Rolt, L. T. C. (1955). Red for Danger. pp. 216–8.

- ^ Sources:

- "TEN DEAD IN RAIL SMASH: Fifty-Three People Injured: Twenty in Serious Condition TRAINS COLLIDE HEAD ON Breach Made in Hospital Wall for Injured". The Manchester Guardian. 15 February 1927. p. 11.

- "HULL RAILWAY DISASTER INQUEST: Rule Often Broken SIGNALS RESTORED TOO SOON Verdict of Accident". The Manchester Guardian. 17 March 1927. p. 7.

- "INQUEST ON VICTIMS OF RAIL DISASTER: Distressing Scenes GOVERNMENT INQUIRY OPENS TO-DAY". The Manchester Guardian. 17 February 1927. p. 4.

- ^ Fawcett 2005, pp. 198–199.

- ^ "Railway Exhibition at Hull". The Manchester Guardian. 25 February 1933. p. 8.

- ^ a b Sources:

- "History of Hull Museums (part 2)". Hull Museums Collections. 2008.

- Sitch, Bryan (September 1994). "Thomas Sheppard and Archaeological Collecting" (PDF). ERAS News (lecture text). East Riding Archaeological Society. pp. 5–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2014.

- ^ The Engineer (8 July 1938) p.49, col.1

- ^ The Engineer (8 July 1938) p.49, col.2

- ^ The Engineer (8 July 1938) p.49, cols.2–3

- ^ The Engineer (8 July 1938) p.49, col.3

- ^ Minnis, John (2012). Railway Signal Boxes – A review. English Heritage. §F. Post-grouping designs, p.43.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Goode 1992, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Fawcett 2005, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d e f "Yorkshire Coast Line – Heritage Rail Trail" (PDF). Yorkshire Coast Community Rail Partnership. 2011. Hull Paragon Station, p.16.

- ^ Hoole 1986, p. 49.

- ^ Fawcett 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Fawcett 2005, p.236; Plate 15.10, p.237; Colour Plate 77, p.239.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (8 October 1990). "Police study hotel blaze". The Guardian. p. 2.

- ^ The Times. No. 63831. 8 October 1990. p. 3.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ London & Amsterdam (Ferensway) Ltd 2001, Overview Statement, §1-1.5, pp.1–2.

- ^ London & Amsterdam (Ferensway) Ltd 2001, Overview Statement, §3.5, p.4.

- ^ a b Neave, David; Neave, Susan (2010). Hull. pp. 134–136.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Paragon Interchange". Hull City Council. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "City's new interchange is open". BBC News Online. 16 September 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ "Railway Heritage Trust Funded Project At Hull Wins Award". www.railwayheritagetrust.co.uk. 27 May 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ "Travel Extra at Hull Paragon Interchange". Visit Hull and East Yorkshire. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "Queen meets city's flood victims". BBC News Online. 5 March 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ "Bronze tribute depicts Philip Larkin rushing for train at Paragon". Hull Daily Mail. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 11 December 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Philip Larkin statue unveiled in Hull". BBC Humberside. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ "Larkins words set to greet visitors". Hull Daily Mail. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Philip Larkin honoured at Hull Paragon station". BBC News Humberside. 2 December 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Full-size model of Amy Johnson's Gipsy Moth on show in Hull". BBC News. BBC. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ "Amy Johnson's Plane Rehomes in St Stephen's". Hull Central. 9 March 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Saker-Clark, Henry (4 August 2017). "Finish date revealed for Hull Paragon refurb which could bring big brands". Hull Daily Mail. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "New Coach Station for Hull". Manchester Guardian. 23 October 1935. p. 9.

- ^ "Paragon Transport Interchange". Wilkinson Eyre Architects. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. 1:2500. 1959–70; OS Open Data, c. 2014

- ^ London & Amsterdam (Ferensway) Ltd 2001, 01_00913_PO-DRAWINGS-347163, Sheet 3, "Proposed Site Plan" (Job 2836, Drawing SK-010, Revision A).

- ^ a b "8. Public transport". Local Transport Plan (2011–2026). Hull City Council. January 2011. §8.1.2, pp.64–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ "London group wins Hull park and ride deal". This is Hull and East Riding. 15 September 2009. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ "Hull to Leeds and Manchester Timetable" (PDF). First TransPennine Express. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ "Hull to Manchester Airport, February 7th at 05:48". thetrainline.com. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ a b Young, Angus (16 February 2017). "Hull Trains and TransPennine Express reveal new services to London and Manchester". Hull Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ See 2014 Northern Rail Timetables: 28, "Hull to Bridlington and Scarborough"; 30. "Hull to Doncaster and Sheffield"; 34, "York to Selby and Hull and York to Sheffield via Pontefract Baghill"

- ^ "Our Timetables". First Hull Trains. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ "Timetable from 19 May 2019" (PDF). London North Eastern Railway. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Fawcett 2001, p. 85.

- ^ "The East Yorkshire Historian". The Journal of the East Yorkshire Local History Society. 7: 108.

- ^ a b Butt 1995, p. 125.

- ^ Quick, M. (2009). Railway Passenger Stations in Great Britain: A Chronology.

- ^ a b c Tuffrey, Peter (2012). East Yorkshire Railway Stations. pp. 66–69.

- ^ London North Eastern Route. Network Rail. December 2006. LN914, LN915.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Sheahan 1864, pp. 201, 563, 577, 605.

- ^ "Mercure Royal Hotel". Mercure Hotels. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Clockwise film locations". IMDb. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "The LNER in Books, Film, and TV". The LNER Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "The true story of when Only Fools and Horses came 'to Hull and back'". Hull Daily Mail. 9 October 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

Maps

- ^ 53°44′00″N 0°22′55″W / 53.73323°N 0.38191°W, Hessle Road junction (North)

- ^ 53°45′22″N 0°23′30″W / 53.75616°N 0.39174°W, Cottingham junction (1848)

- ^ 53°43′29″N 0°23′43″W / 53.72460°N 0.3952°W, Hessle West junction (1848)

- ^ 53°43′58″N 0°22′55″W / 53.73276°N 0.38184°W, Hessle Road junction (1848)

- ^ 53°44′37″N 0°20′48″W / 53.743651°N 0.346715°W, Station entrance (1853)

- ^ a b 53°44′38″N 0°20′48″W / 53.743996°N 0.346797°W, Paragon station (trainshed)

- ^ 53°44′38″N 0°20′44″W / 53.744003°N 0.345469°W, Station Hotel

- ^ 53°44′39″N 0°20′52″W / 53.744144°N 0.347765°W, Engine shed (c. 1850s)

- ^ 53°44′39″N 0°20′58″W / 53.744233°N 0.349335°W, Coal depot (original)

- ^ a b 53°44′41″N 0°20′58″W / 53.744722°N 0.349337°W, Engine shed (c. 1880s), later site of coal depot

- ^ 53°44′35″N 0°20′52″W / 53.743176°N 0.347835°W, Emigrant waiting rooms

- ^ 53°44′40″N 0°20′44″W / 53.744455°N 0.345581°W, Ticket hall and entrance (1904)

- ^ a b c 53°44′40″N 0°20′43″W / 53.744478°N 0.345290°W, Iron entrance canopy (1904); Paragon House (1960); Paragon Interchange entrance hall (2007)

- ^ 53°44′37″N 0°20′43″W / 53.74367°N 0.34531°W, Hotel service building

- ^ 53°44′40″N 0°21′01″W / 53.744372°N 0.350409°W, Platform signal box (1904)

- ^ 53°44′38″N 0°21′04″W / 53.743920°N 0.351163°W, Park Street signal box (1904)

- ^ 53°45′03″N 0°22′35″W / 53.75097°N 0.376421°W, Junction for chord to former Hull and Barnsley Railway

- ^ 53°44′44″N 0°21′35″W / 53.745670°N 0.359604°W, West Parade signal box

- ^ 53°44′39″N 0°21′06″W / 53.744180°N 0.351776°W, Paragon Signal box (1938)

- ^ 53°44′50″N 0°22′00″W / 53.74736°N 0.36660°W, West Parade North junction

- ^ 53°44′38″N 0°22′01″W / 53.74396°N 0.36701°W, Anlaby Road junction

- ^ 53°44′40″N 0°20′50″W / 53.744534°N 0.347133°W, Paragon Interchange bus station (concourse)

Sources

- Sheahan, James Joseph (1864), General and concise history and description of the town and port of Kingston-upon-Hull, Simpson, Marshall and Co. (London)

- "Large Railway Stations – No.1 – Hull Paragon" (PDF), The Engineer, vol. 93, pp. 159–162, 11 February 1908

- Tomlinson, William Weaver (1915), The North Eastern Railway; its rise and development, Andrew Reid and Company, Newcastle; Longmans, Green and Company, London

- Fawcett, Bill (2001), A History of North Eastern Railway Architecture, vol. 1, North Eastern Railway Association

- Fawcett, Bill (2005), A History of North Eastern Railway Architecture, vol. 3, North Eastern Railway Association

- Gillett, Edward; MacMahon, Kenneth A. (1980), A History of Hull, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-713436-X

- Goode, C. T. (1992), The Railways of Hull, ISBN 1870313119

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Neave, David (1995), "Yorkshire: York and the East Riding", The Buildings of England (2nd ed.)

- Hitches, Mike (2012), Steam around York and the East Riding

- "Resignalling of Paragon Station, Hull" (PDF), The Engineer, vol. 166, pp. 48–49, 8 July 1983

- London & Amsterdam (Ferensway) Ltd (15 August 2001), (01/00913/PO) REVISED PROPOSAL FOR REDEVELOPMENT OF LAND FOR A MIXED USE SCHEME COMPRISING: (1) ERECTION OF BUILDINGS AROUND A PEDESTRIAN COVERED STREET FOR RETAIL, FOOD AND DRINK AND LEISURE USES, INCLUDING A HOTEL, RELOCATED ARTS CENTRE AND THEATRE, WITH SERVICE AREAS AND CAR PARKS ACCESSED FROM PARK STREET, PORTLAND STREET AND CANNING STREET (2) PROVISION OF NEW TRANSPORT INTERCHANGE WITH ACCESS FROM FERENSWAY, ALTERATIONS TO PARAGON STATION, TEMPORARY BUS STATION, AND PARKING AREAS (3) PETROL FILLING STATION, WITH ACCESS OFF PARK STREET (4) ERECTION OF BUILDINGS FOR RESIDENTIAL USES WITH ACCESSES FROM SPRING STREET, COLONIAL STREET AND PARK STREET (5) LAYING OUT OF OPEN SPACES, PUBLIC SQUARES (6) HIGHWAY WORKS, PROVISION OF CYCLE AND PEDESTRIAN ROUTES, East Riding of Yorkshire Council[permanent dead link]

- Historic England. "Paragon Station & Station Hotel (1218434)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- Butt, R. V. J. (October 1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199. OL 11956311M.

Further reading

- Lawrence, H. S. (1910). "Twenty-four Hours at Hull (Paragon)". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 27. pp. 144–.

- Steadman, Tony. "Paragon Interchange – gallery". Hull City Council. Retrieved 30 June 2014. Pictorial record of the redevelopment of the Paragon Interchange.

External links

- Train times and station information for Hull Paragon Interchange from National Rail

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1218434)". National Heritage List for England.

- Mercure Hull Royal Hotel

- Railway stations in the East Riding of Yorkshire

- 1847 establishments in England

- Railway stations in Kingston upon Hull

- Former York and North Midland Railway stations

- Railway stations in Great Britain opened in 1847

- Railway stations served by Hull Trains

- Northern franchise railway stations

- Railway stations served by TransPennine Express

- Railway stations served by London North Eastern Railway

- Bus stations in England

- Grade II* listed buildings in the East Riding of Yorkshire

- George Townsend Andrews railway stations

- Thomas Prosser railway stations

- William Bell railway stations

- Transport in Kingston upon Hull

- DfT Category B stations

- Grade II* listed railway stations