Turkic peoples: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 386: | Line 386: | ||

* [http://www.vatankirim.net Crimean Tatar Web Site] |

* [http://www.vatankirim.net Crimean Tatar Web Site] |

||

* [http://www.kirimtatar.net Kemal's Crimean Tatar Web Site with Crimean Tatar Language Resources] |

* [http://www.kirimtatar.net Kemal's Crimean Tatar Web Site with Crimean Tatar Language Resources] |

||

* [http://www.cafeterya.com Okey] |

|||

* [http://www.oktaka.com Okey] |

* [http://www.oktaka.com Okey] |

||

* [http://www.adji.ru/main_en.html Murad Adji's site] Contains books in English |

* [http://www.adji.ru/main_en.html Murad Adji's site] Contains books in English |

||

Revision as of 21:58, 31 October 2009

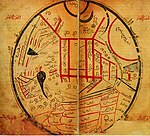

Countries and autonomous regions where a Turkic language has official status.

Countries and autonomous regions where a Turkic language has official status. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Asia Minor and the Middle East, the Caucasus, Central Asia, Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Siberia, Western China, Western Mongolia and as immigrant communities in Australia, North America, and Western Europe. | |

| Languages | |

| Turkic Languages, closely related to other Altaic languages. | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (predominantly), Christianity[1], Buddhism[2], Shamanism, Tengriism, Atheism, Agnosticism and Syncretic religion. |

The Turkish peoples are Eurasian peoples residing in northern, central and western Eurasia. They speak languages belonging to the Turkic language family.[4] They share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds. The term Turkic represents a broad ethno-linguistic group of people including existing societies such as the Azerbaijani, Kazakhs, Tatar, Kyrgyz, Turkish people, Turkmen, Uyghur, Uzbeks, and as well as past civilizations such as the Huns, Bulgars, Kumans, Avars, Seljuks, Khazars, Ottomans, Mamluks, Timurids, and possibly the Xiongnu.[4][5][6]

Many of the Turkish peoples have their homelands in Central Asia, where the Turkish peoples originated from, but since then Turkic languages have spread, through migrations and conquests, to other locations including present-day Turkey. While the term "Turk" may refer to a member of any Turkic people, the term Turkish usually refers specifically to the people and language of Turkey.

Demographics

The distribution of people of Turkic cultural background ranges from Siberia, across Central Asia, to Eastern Europe. Presently, the largest groups of Turkic people live throughout Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan, in addition to Turkey. Additionally, Turkic peoples are found within Crimea, East Turkistan region of western China, northern Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Israel, Russia, Afghanistan, Cyprus, and the Balkans: Moldova, Bulgaria, Romania, and former Yugoslavia. A small number of Turkic people also live in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. There is also a small number in eastern Poland and southeastern part of Finland.[7]. There are also considerable populations of Turkic people (originating mostly from Turkey) in Germany, United States, and Australia, largely because of migrations during the twentieth century.

Sometimes the above list is grouped into six branches: the Oghuz Turks, Kipchak, Karluk, Siberian, Chuvash, and Sakha/Yakut branches. The Oghuz have been termed Western Turks, while the remaining five, in such a classificatory scheme, are called Eastern Turks.

One of the major difficulties perceived by many who try to classify the various Turkic languages and dialects is the impact of Soviet and particularly Stalinist nationality policies—the creation of new national demarcations, suppression of languages and writing scripts, and mass deportations—had on the ethnic mix in previously multicultural regions like Khwarezm, the Fergana Valley, and Caucasia. Many of the above-mentioned classifications are therefore by no means universally accepted, either in detail or in general. Another aspect often debated is the influence of Pan-Turkism, and the emerging nationalism in the newly independent Central Asian republics, on the perception of ethnic divisions.

The Turkic peoples display a great variety of ethnic types.[8] They possess physical features ranging from Caucasoid to Northern Mongoloid. Mongoloid and Caucasoid facial structure is common among many Turkic groups, such as Chuvash people, Tatars, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Hazara, and Bashkirs. There has been much debate about the racial nature of the original Turkic-speaking ancestors, with some in the past presuming a "Ural-Altaic race" with Caucasoid features at one end of the spectrum and Mongoloid features at the other.

The following is an incomplete list of Turkic people with the respective groups's core areas of settlements and their estimated sizes (in million):

| People | region | population |

|---|---|---|

| Turkish people | Turkey, Cyprus, Germany, France, England, USA, Bulgaria, Greece Georgia Syria Iraq |

70 M |

| Uzbeks | Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan | 23 to 29 M |

| Azerbaijanis | Iran, Azerbaijan | 21 to 30 M |

| Uyghurs | China, Pakistan, Kazakhstan | 20 M |

| Kazakhs | Kazakhstan, Russia, Pakistan, China(Xinjiang), and Uzbekistan | 16 M |

| Tatars | Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Finland | 10 M |

| Turkmens | Turkmenistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan | 7 M |

| Kyrgyzs | Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan | 4 M |

| Chuvashs | Russia | 1.8 M |

| Bashkirs | Russia | 1.8 M |

| Gagauzs | Moldovia | 0.2 M |

| Yakuts | Russia | 0.5 M |

| Karachays and Balkars | Russia, Turkey | 0.4 M |

| Crimean Karaites and Krymchaks | Lituania, Poland, Russia, Turkey |

Geographical distribution

The Turkic languages constitute a language family of some 30 languages, spoken across a vast area from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, to Siberia and Western China, and to northern edges of Pakistan and the Middle East.

Some 165 million people have a Turkic language as their native language;[9] an additional 20 million people speak a Turkic language as a second language. The Turkic language with the greatest number of speakers is Turkish proper, or Anatolian Turkish, the speakers of which account for about 40% of all Turkic speakers.[10] More than one third of these are ethnic Turks of Turkey, dwelling predominantly in Turkey proper and formerly Ottoman-dominated areas of Eastern Europe and West Asia; as well as in Western Europe, Australia and the Americas as a result of immigration. The remainder of the Turkic people are concentrated in Central Asia, Russia, the Caucasus, China, northern Iraq and northern and northwestern Iran.

At present, there are six independent Turkic countries: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Turkey, Uzbekistan; There are also several Turkic national subdivisions[11] in the Russian Federation including Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, Chuvashia, Khakassia, Tuva, Yakutia, the Altai Republic, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Karachayevo-Cherkessiya. Each of these subdivisions has its own flag, parliament, laws, and official state language (in addition to Russian).

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in western China and the autonomous region of Gagauzia, located within eastern Moldova and bordering Ukraine to the north, are two major autonomous Turkic regions. The Autonomous Republic of Crimea within Ukraine is a home of Crimean Tatars. In addition, there are several Turkic-inhabited regions in Iran, Iraq, Georgia, Bulgaria, the Republic of Macedonia, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and western Mongolia.

In the age of nationalism, Turkic speakers were among the first Muslim people to take up Western ideas of liberalism and secular ideologies. Pan-Turkism first sprang up at the end of the nineteenth century in the Russian Empire and was advanced by leading Turkish intellectuals like Crimean Tatar İsmail Gaspıralı, Azerbaijan philosophers like Mirza Fatali Akhundov and Tatar Yusuf Akçura, as a reaction to Panslavist and Russification policies of the Russian Empire. The first fully democratic and secular republics in the Islamic world were Turks: the ill-fated Idel-Ural State established in 1917, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1918 (both annexed and absorbed by the Soviet Union), and in 1923 Republic of Turkey. In 1991 Azerbaijan became an independent Azerbaijan Republic.

The Turks in Turkey are over 60 million[12] to 70 million worldwide, while the second largest Turkic people are the Azerbaijanis, numbering 20.5 to 33 million worldwide; most of them live in northwestern Iran ("Iranian Azerbaijan") and the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Nomenclature

The first known mention of the term Turk applied to a Turkic group was in reference to the Göktürks in the sixth century. A letter by the Chinese Emperor written to a Göktürk Khan named Ishbara in 585 described him as "the Great Turk Khan." The Orhun inscriptions (AD 735) use the terms Turk and Turuk.

Previous use of similar terms are of unknown significance, although some strongly feel that they are evidence of the historical continuity of the term and the people as a linguistic unit since early times. This includes a Chinese record of 1328 BC referring to a neighbouring people as Tu-Kiu.

In modern Turkey, a distinction is made between "Turks" and the "Turkic peoples" in loosely speaking: the term Türk corresponds specifically to the "Turkish-speaking" people (in this context, "Turkish-speaking" is considered the same as "Turkic-speaking"), while the term Türki refers generally to the people of modern "Turkic Republics" (Türki Cumhuriyetler or Türk Cumhuriyetleri). However, the proper usage of the term is based on the linguistic classification in order to avoid any political sense. In short, the term Turkic can be used for Turk or vice versa.[13]

According to Mahmud of Kashgar, an eleventh century Turkic scholar, and various other traditional Islamic scholars and historians, the name "Turk" stems from Tur, one of the sons of Japheth, and comes from the same lineage as Gomer (Cimmerians) and Ashkenaz (Scythians, Ishkuz) who, according to tradition, were some of the earliest Turks. For millennia, a long string of historical references specifically linked Herodotus’ Scythians with various tribes, such as the Hunno-Bulgars, Avars, Türks, Mongols, Khazars etc. [15]. Between 400 CE and the 16th century the Byzantine sources use the name Σκΰθαι in reference to twelve different Türkic peoples [15] (most modern scholars believe these tribes to have been Iranian). A similar name, Dur, appears in mediaeval Hungarian legend as a legendary chieftain of the Caucasian Alans (Arran, Iron) whose daughters supposedly bred with the Magyar ancestors Hunor and Magor.

Alp Er Tunga is a mythical hero in Turkic tradition; the Göktürks of the sixth century carried on the tradition of Alp Er Tunga and they too had a myth according to which they themselves were descendants of a wolf.

History

Origins and early expansion

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (September 2009) |

The first historical text to mention the Turks was from the standpoint of the Chinese, who mentioned trade of Turk tribes with the Sogdians along the Silk Road.[16] It has often been suggested that the Xiongnu mentioned in Han Dynasty records may have been Proto-Turkic speakers,[17][18][19][20][21] and though little is known for certain about their language(s), it seems likely that at least some of them spoke an Altaic (Turkic?) language[22], while some scholars see a possible connection with the Iranic-speaking Sakas,[23] while others believe they were probably a confederation of various ethnic and linguistic groups. All that can be said with certainty is that

". . . the earliest clearly Turkic peoples appeared on the peripheries of the late Xiongnu Empire. Peoples associated with it also spread far to the west, if, as often thought, what the Europeans called the Huns were an extension of the Xiongnu. If not their ethnic progenitors, then, the Xiongnu had manifold ties to the later Turks.[24]

As suggested above, there is a similar uncertainty about the ethnic and linguistic background of the Hun hordes of Attila who invaded and conquered much of Europe.[25][26] On the other hand, recent genetics research dated 2003[27] confirms the studies indicating that the Turkic people originated from the same area and therefore are possibly related with the Xiongnu.[28]

The rock art of the Yinshan and Helanshan is dated from the 9th millennium BC to 19th century. It consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and only minimally of painted images.[29] Ma Liqing compared the petroglyphs (which he presumed to be the sole extant example of possible Xiongnu writings), and the Orkhon script (the earliest known Turkic alphabet) recently, and argued a new connection between the two.[30]

Excavations conducted between 1924–1925, in Noin-Ula kurgans located in Selenga River in the northern Mongolian hills north of Ulan Bator, produced objects with over twenty carved characters, which were either identical or very similar to that of to the runic letters of the Turkic Orkhon script discovered in the Orkhon Valley.[31]

The first recorded use of "Turk" as a political name is a sixth-century reference to the word now pronounced in Modern Chinese as Tujue. It is believed that some Turkic tribes, such as Khazars and Pechenegs, probably lived as nomads for many years before establishing a political state (Göktürk empire). Turkic peoples originally used their own alphabets, like Orkhon and Yenisey runiform, and later the Uyghur alphabet. The oldest inscription was found near the Issyk river in Kyrgyzstan and has been dated to 500 BC. The traditional national and cultural symbols of the Turkic peoples include wolves, a part of Turkic mythology and tradition; as well as the color blue, iron, and fire. The turquoise blue, from the French of Turkish, is the colour of the stone turquoise still used as jewelry and a protection against evil eye.

Four hundred years after the collapse of northern Xiongnu power in Inner Asia, leadership of the Turkic peoples was taken over by the Göktürks. Formerly an element of the Xiongnu nomadic confederation, the Göktürks inherited their traditions and administrative experience. From 552 to 745, Göktürk leadership bound together the nomadic Turkic tribes into an empire, which eventually collapsed due to a series of dynastic conflicts. The great difference between the Göktürk Khanate and its Xiongnu predecessor was that the Göktürks' temporary khans from the Ashina clan were subordinate to a sovereign authority that was left in the hands of a council of tribal chiefs. The Khanate received missionaries from the Buddhists, Manicheans, and Nestorian Christians, but retained their original shamanistic religion, Tengriism. The Göktürks were the first Turkic people to write their language in a runic script.

The Turkic peoples and the related groups migrated west towards Eastern Europe, Iranian plateau and Anatolia.[32] Turks or Turkish people are among those who migrated early from what is known today as Mongolia to modern Turkey but also among the late-arrival peoples; they also participated in the Crusades.[33] After many battles they established their own state and later created the Ottoman Empire.[34]

It is generally believed that the first Turkic people were native to a region extending from Central Asia to Siberia. Some scholars contend that the Huns were one of the earlier Turkic tribes, while others support Mongolic origin for the Huns.[35] Otto Maenchen-Helfen's linguistic studies also support a Turkic origin for the Huns. [36][37] The main migration of Turks, who were among the ancient inhabitants of Turkestan, occurred in medieval times, when they spread across most of Asia and into Europe and the Middle East.[38]

The precise date of the initial expansion from the early homeland remains unknown. The first state known as "Turk", giving its name to many states and peoples afterwards, was that of the Göktürks (gok = "blue" or "celestial") in the sixth century AD. The head of the Asena clan led his people from Li-jien (modern Zhelai Zhai) to the Juan Juan seeking inclusion in their confederacy and protection from China. His tribe were famed metal smiths and were granted land near a mountain quarry which looked like a helmet, from which they were said to have gotten their name 突厥(tūjué). A century later their power had increased such that they conquered the Juan Juan and set about establishing their Gök Empire.[38]

Later Turkic peoples include the Avars, Karluks (mainly eighth century), Uyghurs, Kyrgyz, Oghuz (or Ğuz) Turks, and Turkmens. As these peoples were founding states in the area between Mongolia and Transoxiana, they came into contact with Muslims, and most gradually adopted Islam. However, there were also (and still are) small groups of Turkic people belonging to other religions, including Christians, Jews (Khazars), Buddhists, and Zoroastrians.

Middle Ages

Turkic soldiers in the army of the Abbasid caliphs emerged as the de facto rulers of most of the Muslim Middle East (apart from Syria and Egypt), particularly after the tenth century. The Oghuz and other tribes captured and dominated various countries under the leadership of the Seljuk dynasty and eventually captured the territories of the Abbasid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.[38]

Meanwhile, the Kyrgyz and Uyghurs were struggling with one another and with the Chinese Empire. The Kyrgyz people ultimately settled in the region now referred to as Kyrgyzstan. The Tatar peoples conquered the Volga Bulgars in what is today Tatarstan, following the westward sweep of the Mongols under Genghis Khan in the thirteenth century. Those Volga Bulgars were thus mistakenly called Tatars by the Russians. Native Tatars live only in Asia; European "Tatars" are in fact Bulgars. Other Bulgars, who had initially invaded Europe in 5th-6th centuries, as part of the Hunnic tribal confederation, finally settled in Southastern Europe in the 7th-8th centuries,and mixed with the Slavic population, adopting what eventually became the Slavic Bulgarian language. Everywhere, Turkic groups mixed with the local populations to varying degrees.[38] In 1090–91, the Turkic Pechenegs reached the walls of Constantinople, where Emperor Alexius I with the aid of the Kipchaks annihilated their army.[39]

Islamic empires

As the Seljuk Empire declined following the Mongol invasion, the Ottoman Empire emerged as the new important Turkic state, that came to dominate not only the Middle East, but even southeastern Europe, parts of southwestern Russia, and northern Africa.[38]

The Mughal Empire was a Muslim empire that, at its greatest territorial extent, ruled most of the Indian subcontinent, then known as Hindustan, and parts of what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan from the early 16th to the mid-18th century. The Mughal dynasty was founded by a Chagatai Turkic prince named Babur (reigned 1526–30), who was descended from the Turkic conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) on his father's side and from Chagatai, second son of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, on his mother's side.[40][41] The Mughal dynasty was notable for the ability of its rulers, who through seven generations maintained a record of unusual talent, and for its administrative organization. A further distinction was the attempt of the Mughals to integrate Hindus and Muslims into a united Indian state.[40][42][43][44]

The Ottoman Empire gradually grew weaker in the face of maladministration, repeated wars with Russia and Austro-Hungary, and the emergence of nationalist movements in the Balkans, and it finally gave way after World War I to the present-day republic of Turkey.[38]

Language

The Turkic alphabets are sets of related alphabets with letters (formerly known as runes), used for writing mostly Turkic languages. Inscriptions in Turkic alphabets were found from Mongolia and Eastern Turkestan in the east to Balkans in the west. Most of the preserved inscriptions were dated to between 8th and 10th centuries AD.

The earliest positively dated and read Turkic inscriptions date from ca. 150, and the alphabets were generally replaced by the Uyghur alphabet in the Central Asia, Arabic script in the Middle and Western Asia, Greek-derived Cyrillic in Eastern Europe and in the Balkans, and Latin alphabet in Central Europe. The latest recorded use of Turkic alphabet was recorded in Central Europe's Hungary in AD 1699.

The Turkic runiform scripts, unlike other typologically close scripts of the world, do not have a uniform palaeography as, for example, have the Gothic runes, noted for the exceptional uniformity of its language and paleography. [45] The Turkic alphabets are divided into four groups, the best known of them is the Orkhon version of the Enisei group.

The Turkic language family is traditionally considered to be part of the proposed Altaic language family.[10][46][47][48] The Altaic language family includes 66 languages[49] spoken by about 348 million people, mostly in and around Central Asia and northeast Asia.[46][50][51]

The various Turkic languages are usually considered in geographical groupings: the Oghuz (or Southwestern) languages, the Kypchak (or Northwestern) languages, the Eastern languages (like Uygur), the Northern languages (like Altay and Yakut), and divergent languages (like Chuvash). The high mobility and intermixing of Turkic peoples in history makes an exact classification extremely difficult.

The Turkish language belongs to the Oghuz subfamily of Turkic. It is for the most part mutually intelligible with the other Oghuz languages, which include Azeri, Gagauz, Turkmen and Urum, and to a varying extent with the other Turkic languages.

Mythology

Turkic mythology is the mythology of the Turkic peoples that spoke Turkic languages which are argued to be a subfamily of the disputed Altaic language family. Tengriism and other Shamanistic religions had been the dominant religion for most of history.

In one tradition, described in the ancient Zoroastrian text called the Zend-Avesta — similar to the biblical story of Noah — the Turkic peoples are descendants of "Tur" or "Tura", a grandson of Yima, who was the sole survivor of a catastrophe that depopulated the Earth.

Animals

The Wolf symbolizes honour and is also considered the father of most Turkic peoples. Asena (Ashina Tuwu) is the wolf mother of Tumen Il-Qağan, the first Khan of the Göktürks.

The Horse is also one of the main figures of Turkic mythology. Türks consider the horse an extension of the human, one creature.

The Dragon, also expressed as a Snake or Lizard, is the symbol of might and power. It is believed, especially in mountainous Central Asia, that dragons still live in the mountains of Tian-Shan (Tangri Tagh) and Altay. Dragons also symbolize the god Tengri (Tanrı) in ancient Turkic tradition, although dragons themselves aren't worshipped as gods.

Personalities

Geser (Ges'r, Kesar) is a Tibetan/Mongolian religious epic about 'Geser' (also known as 'Bukhe Beligte') a Turkic prophet who taught Türks the new monotheistic religion Tengriism. It is unknown when he lived, and there are not many historical documents that mention him. Tengriism isn't approved by most Muslim scholars, but sura 108 of the Quran has the name Al-Kawthar,in which the word kawthar could potentially be read as 'Käusar', which may be an Arabisation of the Turkic name 'Geser'. The name of this sura is conventionally interpreted as "all goods" or "abundance", but this is not certain and many scholars have different opinions on this sura.

The legend of Timur (Temir) is the most ancient and well-known. Timur found a strange stone that fell from the sky, an iron ore meteorite. He was a smith and decided to make a sword of it. Few knew about iron in Asia before then. He tried to make a sword from it by using the usual bronze sword making process. He mentioned that this material, iron, was very easy to change and manipulate, though it was even stronger than bronze. Today, the word "temir" or "timur" means "iron". The melting process was known before in Egypt, but it wasn't used that widely in Asia, because of the very high iron price (much higher than gold) in the Mediterranian and Europe at that time.

Bai-Ulgan (Bai-Ulgen, Ulgen, Ülgen, Ulgan) is a Turkic and Mongolian creator-deity.

In the Bible, Togarmah, son of Gomer, was ancestor of the Turkic-speaking peoples. His sons Ujur (Uyghur: Mongol-Turks), Tauris, Avar, Uauz (Oghuz Turks), Bizal, Tarna, Khazar, Janur, Bulgar, and Sawir (Sabir, a Turkic people, probably of Hunnic origin) are the mythical founders of tribes that once lived around the Black and Caspian Seas.

Religion

Various pre-Islamic Turkic civilizations of the sixth century adhered to shamanist and Tengriist traditions which are reflected in the state symbols of Kazakhstan. The Shamanist religion is based on spiritual and natural elements of earth. Tengriism involves belief in Tengri as the god who ruled over the skies. Turkish: Tanrı and Azerbaijani: Tanrı remain in use by speakers of those languages as a term for God regardless of their faith.

Today, most Turks are Sunni Muslims. These include the majority of Balkan Turks, Balkars, Bashkorts, Crimean Tatars, Karachay, Kazaks, Kumuk, Kyrgyz, Nogay, Tatars (Kazan Tatars), Turkmens, Turks of Turkey, Uygurs, and Uzbeks. The Azerbaijanis of the Republic of Azerbaijan and Iranian Azerbaijan are the only major Turkic-speaking people that traditionally adhere to the Shī‘ah sect of Islam. The Qashqay nomads and Khorasani Turks as well as various Turkic tribes spread across Iran are also Shī‘ah. The Alevis of Turkey are the largest religious minority in the country. Their belief system is a branch of Twelver Shī‘ah theology.

The major Christian-Turkic peoples are the Chuvash of Chuvashia and the Gagauz (Gökoğuz) of Moldova. Many Karaim Turks of Eastern Europe are Jewish, and there are Turks of Jewish backgrounds who live in major cities such as Istanbul, Ankara and Baku. The Khazars, who existed long before Islam appeared, widely practiced Judaism. In the Siberian region, the Altay, some Tuvan and Hakas are Tengriist, having kept the original religion of Turkic peoples.[citation needed] The Yakuts of Yakutia in northeastern Siberia are traditionally Shamanists, yet many have converted to Christianity. The Sari Uygurs "Yellow Yughurs" of Western China, as well as the Tuvans of Russia are the only remaining Buddhist Turkic peoples. In addition, there are small scattered populations of Turks belonging to other religions such as the Bahá'í Faith and Zoroastrianism.

Even though many Turkic peoples became Muslims under the influence of Sufis, often of Shī‘ah persuasion, most Turkic people today are Sunni Muslims, although a significant number in Turkey are Alevis. Alevi Turks, who were once primarily dwelling in eastern Anatolia, are today concentrated in major urban centers in western Turkey with the increased urbanism.

The traditional religion of the Chuvash of Russia, while containing many ancient Turkic concepts, also shares some elements with Zoroastrianism, Khazar Judaism, and Islam. The Chuvash religious calendar cycle and the agrarian cult that it was based on combined ancestor worship and worship of earth, water and vegetation. The Chuvash converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity for the most part in the second half of the nineteenth century. As a result, festivals and rites were made to coincide with Orthodox feasts, and Christian rites replaced their traditional counterparts. A minority of the Chuvash still profess their traditional faith.[52]

Some Turkic peoples (particularly in the Russian autonomous regions and republics of Altay, Khakassia and Tuva) are largely Tengriists. Tengriism was the predominant religion of the different Turkic branches prior to the eighth century, when the majority accepted Islam.

Traditional Inner Asian cults, commonly referred to as shamanism, survive in many places, often submerged in other religions. In post-Soviet Siberia, 300 years after their forced conversion, the Yakuts (Sakha) and others have completely rejected Eastern Orthodox Christianity in favor of a revived shamanism.[53]

Gallery

-

2nd century BC - 2nd century AD, characters of Hun- Syr-Tardush (Syanbi) script (Mongolia and Inner Mongolia), N. Ishjatms, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the "History of civilizations of Central Asia", Volume 2, Fig 5, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

-

Oldest known Turkic alphabet listings, Rjukoku and Toyok manuscripts. Toyok manuscript transliterates Turkic alphabet into the Uyghur alphabet. Per I.L. Kyzlasov, Runic Scripts of Eurasian Steppes, Moscow, Eastern Literature, 1994, ISBN 5-02-017741-5.

-

Inscription in Kyzyl using Orkhon script

-

Golden Horde invasion of Russia in 1382.

-

The entry of Mehmet II into Constantinople.

-

Sattar Khan (1868-1914) was a major revolutionary figure in the late Qajar period in Iran.

-

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk with his soldiers at Anafartalar, Çanakkale, 1915.

-

The battle of Wadi al-Khazandar, 1299. 14th century image.

-

Karachay patriarchs in the nineteenth century

-

Whirling dervishes in Turkey

-

Qashqai caravan halt in Iran

-

Kazan Tatar woman, 18th century

-

Crimean Tatar soldier fighting with the soldier of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

-

Babur, founder of the Mughal dynasty.

People

-

Meyers Blitz-Lexikon (Leipzig, 1932) shows a Turkish man as an example of the ethnic Turkish type.

-

Azerbaijani girls (Azerbaijan)

-

Uzbek students (Uzbekistan)

-

Turkmen girl (Turkmenistan)

-

Kyrgyz man performing epic poem (Kyrgyzstan)

-

Performing Azeri musicians

-

Gagauz people in traditional clothing (Moldova)

-

An Uzbek girl with traditional headdress. (Uzbekistan)

-

A Dolgan

Flags of the Turkic republics

-

Flag of Altai Republic

-

Flag of Azerbaijan

-

Flag of Bashkortostan

-

Flag of Chuvashia

-

Flag of Gagauzia

-

Flag of Kabardino-Balkaria

-

Flag of Karachay-Cherkessia

-

Flag of Karakalpakstan

-

Flag of Kazakhstan

-

Flag of Khakassia

-

Flag of Kyrgyzstan

-

Flag of Sakha

-

Flag of Tatarstan

-

Flag of Turkey

-

Flag of Turkmenistan

-

Flag of Tuva

-

Flag of Uzbekistan

-

The "Kokbayraq" flag. Flag of 1st ETR. This flag is currently used as a symbol of the Uyghurs East Turkestan independence movement. The Chinese government prohibits using the flag in the country.

-

Unofficial Gagauzia flag.

-

Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.

Notes and references

- ^ The Gagauz of the Danubian delta, the Chuvash of the Volga region, and the Yakuts and some smaller Turkic people in Siberia are Orthodox Christians

- ^ The Tuvans of Siberia and the Yellow Uighurs of Gansu Province, China are Buddhists

- ^ Ethnic people groups of the Turkic people

- ^ a b Turkic people, Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Academic Edition, 2008

- ^ "Timur", The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001–05, Columbia University Press.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica article: Consolidation & expansion of the Indo-Timurids, Online Edition, 2007.

- ^ Finnish Tatars

- ^ Turkic people, Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Edition, 2008

- ^ Turkic Language family tree entries provide the information on the Turkic-speaking populations and regions.

- ^ a b Katzner, Kenneth (2002). Languages of the World, Third Edition. Routledge, an imprint of Taylor & Francis Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0415250047.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Across Central Asia, a New Bond Grows - Iron Curtain's Fall Has Spawned a Convergence for Descendants of Turkic Nomad Hordes

- ^ (in Turkish). Milliyet. 2008-06-06 http://www.milliyet.com.tr/default.aspx?aType=SonDakika&Kategori=yasam&ArticleID=873452&Date=07.06.2008&ver=16. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Jean-Paul Roux, "Historie des Turks - Deux mille ans du Pacifique á la Méditerranée". Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2000.

- ^ Alekseev A.Yu. et al., "Chronology of Eurasian Scythian Antiquities Born by New Archaeological and 14C Data", © 2001 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona, Radiocarbon, Vol .43, No 2B, 2001, p 1085–1107

- ^ a b G. Moravcsik, "Byzantinoturcica" II, p. 236–39

- ^ Etienne de la Vaissiere, Encyclopaedia Iranica Article:Sogdian Trade, 1 December 2004.

- ^ Silk-Road:Xiongnu

- ^ Yeni Türkiye

- ^ The Rise of the Turkic People

- ^ Early Turkish History

- ^ "An outline of Turkish History until 1923."

- ^ Lebedynsky (2006), p. 59.

- ^ Beckwith (2009), pp. 72–73 and 404–405, nn. 51–52.

- ^ Findley (2005), p. 29.

- ^ Chinese History - The Xiongnu

- ^ G. Pulleyblank, "The Consonantal System of Old Chinese: Part II", Asia Major n.s. 9 (1963) 206—65

- ^ Keyser-Tracqui C., Crubezy E., Ludes B. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis of a 2,000-year-old necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia American Journal of Human Genetics 2003 August; 73(2): 247–260.

- ^ Nancy Touchette Ancient DNA Tells Tales from the Grave "Skeletons from the most recent graves also contained DNA sequences similar to those in people from present-day Turkey. This supports other studies indicating that Turkic tribes originated at least in part in Mongolia at the end of the Xiongnu period."

- ^ Paola Demattè Writing the Landscape: the Petroglyphs of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Province (China). (Paper presented at the First International Conference of Eurasian Archaeology, University of Chicago, 3 May-4 May 2002.)

- ^ MA Li-qing On the new evidence on Xiongnu's writings. (Wanfang Data: Digital Periodicals, 2004)

- ^ N. Ishjatms, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the "History of civilizations of Central Asia", Volume 2, Fig 6, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

- ^ Josh Burk, "The Middle East and Its Origins" p.45"

- ^ Moses Parkson, "Ottoman Empire and its past life" p.98

- ^ Johnson, Mark "Turkic roots its origins" p.43

- ^ The Origins of the Huns

- ^ Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen. The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press, 1973

- ^ Otto Maenchen-Helfen, Language of Huns

- ^ a b c d e f Carter V. Findley, The Turks in World History, (Oxford University Press, October 2004) ISBN 0-19-517726-6

- ^ The Pechenegs, Steven Lowe and Dmitriy V. Ryaboy

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica Article:Mughal Dynasty

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Article:Babur

- ^ the Mughal dynasty

- ^ When the Moguls Ruled India...

- ^ Babur: Encyclopædia Britannica Article

- ^ Vasiliev D.D. Graphical fund of Turkic runiform writing monuments in Asian areal, М., 1983, p. 44

- ^ a b Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Language Family Trees - Altaic". Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg, S., Michalove, P.A., Manaster Ramer, A., Sidwell, P.J.: "Telling general linguists about Altaic", Journal of Linguistics 35 (1999): 65–98 Online abstract and link to free pdf

- ^ Turkic peoples, Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Academic Edition, 2008

- ^ Language Family Trees: Altaic

- ^ Altaic Language Family Tree Ethnologue report for Altaic.

- ^ Ethnographic maps

- ^ Guide to Russia:Chuvash

- ^ A.M. Khazanov, After the USSR: Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Politics in the Commonwealth of Independent States., pp.184–89, 1995, University of Wisconsin Press

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Thoughts on the Origins of the Turks and the Shaping of the Turkic Peoples". (2006) In: Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Ed. Victor H. Mair. University of Hawai'i Press. Pp. 136–157. ISBN 978-0-8248-2884-4; ISBN 0-8248-2884-4

Further reading and references

- Alpamysh, H.B. Paksoy: Central Asian Identity under Russian Rule (Hartford: AACAR, 1989)

- Amanjolov A.S., "History of тhe Ancient Turkic Script", Almaty, "Mektep", 2003, ISBN 9965-16-204-2

- Baichorov S.Ya., "Ancient Turkic runic monuments of the Europe", Stavropol, 1989 (In Russian)

- Baskakov, N.A. 1962, 1969. Introduction to the study of the Turkic languages. Moscow. (In Russian).

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009): Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Boeschoten, Hendrik & Lars Johanson. 2006. Turkic languages in contact. Turcologica, Bd. 61. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3447052120.

- Chavannes, Édouard (1900): Documents sur les Tou-kiue (Turcs) occidentaux. Paris, Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient. Reprint: Taipei. Cheng Wen Publishing Co. 1969.

- Clausen, Gerard. 1972. An etymological dictionary of pre-thirteenth-century Turkish. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deny, Jean et al. 1959-1964. Philologiae Turcicae Fundamenta. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Findley, Carter Vaughn. 2005. The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516770-8; ISBN 0-19-517726-6 (pbk.)

- Golden, Peter B. An introduction to the history of the Turkic peoples: Ethnogenesis and state-formation in medieval and early modern Eurasia and the Middle East, (Otto Harrassowitz (Wiesbaden) 1992) ISBN 3-447-03274-X

- Heywood, Colin. The Turks (The Peoples of Europe), (Blackwell 2005), ISBN 978-0631158974.

- Hostler, Charles Warren. The Turks of Central Asia, (Greenwood Press, November 1993), ISBN 0-275-93931-6.

- Ishjatms N., "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the "History of civilizations of Central Asia", Volume 2, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- Johanson, Lars & Éva Agnes Csató (ed.). 1998. The Turkic languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08200-5.

- Johanson, Lars. 1998. "The history of Turkic." In: Johanson & Csató, pp. 81–125. Classification of Turkic languages

- Johanson, Lars. 1998. "Turkic languages." In: Encyclopaedia Britannica. CD 98. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, 5 September. 2007. Turkic languages: Linguistic history.

- Kyzlasov I.L., "Runic Scripts of Eurasian Steppes", Moscow, Eastern Literature, 1994, ISBN 5-02-017741-5.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. (2006). Les Saces: Les « Scythes » d'Asie, VIIIe siècle apr. J.-C. Editions Errance, Paris. ISBN 2-87772-337-2.

- Malov S.E., "Monuments of the ancient Turkic inscriptions. Texts and research", M.-L., 1951 (In Russian).

- Mukhamadiev A., "Turanian Writing", in "Problems Of Lingo-Ethno-History Of The Tatar People", Kazan, 1995, ISBN 5-201-08300 (Азгар Мухамадиев, "Туранская Письменность", "Проблемы лингвоэтноистории татарского народа", Казань, 1995. с.38, ISBN 5-201-08300, (In Russian)

- Menges, K. H. 1968. The Turkic languages and peoples: An introduction to Turkic studies. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Öztopçu, Kurtuluş. 1996. Dictionary of the Turkic languages: English, Azerbaijani, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Turkish, Turkmen, Uighur, Uzbek. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415141982

- Samoilovich, A. N. 1922. Some additions to the classification of the Turkish languages. Petrograd. Classification of Türkic languages

- Schönig, Claus. 1997-1998. "A new attempt to classify the Turkic languages I-III." Turkic Languages 1:1.117–133, 1:2.262–277, 2:1.130–151.

- Vasiliev D.D. Graphical fund of Turkic runiform writing monuments in Asian areal. М., 1983, (In Russian)

- Vasiliev D.D. Corpus of Turkic runiform monuments in the basin of Enisei. М., 1983, (In Russian)

- Voegelin, C.F. & F.M. Voegelin. 1977. Classification and index of the World's languages. New York: Elsevier.

See also

- Chigils Turks

- Shatuo Turks

- Pan-Turanism

- Pan-Turkism

- Turkic European

- Turkic languages

- Turkic migrations

- Turkic states and empires

- Turko-Iranian

- Turko-Persian tradition

- Turko-Mongol

- Turkology

- List of ethnic groups

- European ethnic groups

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- Altaic people

External links

- Turkic Republics, Regions, and Peoples: Resources - University of Michigan

- Turkic Cultures and Children's Festival, Turkic Fest

- Encyclopedia Britanica 1911 Edition

- turkicworld

- Ethnographic maps

- International Turcology and Turkish History Research Symposium

- Istanbul Kültür University

- Examples of traditional Turkish and Ottoman Clothing

- Türkçekent Orientaal's links for Turkish Language Learning

- Türkçestan Orientaal's links to Turkic languages

- Ural-Altaic-Sumerian Etymological Dictionary

- Crimean Tatar Internet Resources

- Nationwide game of Turks

- Crimean Tatar Web Site

- Kemal's Crimean Tatar Web Site with Crimean Tatar Language Resources

- Okey

- Okey

- Murad Adji's site Contains books in English

New DNA Results

- "Probable ancestors of Hungarian ethnic groups: an admixture analysis"C. R. GUGLIELMINO1, A. DE SILVESTRI2 and J. BERES

- MtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms in Hungary: inferences from the Palaeolithic, Neolithic and Uralic influences on the modern Hungarian gene pool

- World History Study Guide: "Dastan Turkic" at BookRsgs.com

- The Altaic Epic