Human: Difference between revisions

m fix interwiki, accidentally lost in editing |

|||

| (418 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Taxobox | color = pink |

||

| name = Human |

|||

{{Taxobox_image | image = [[Image:PPlaquecloseup.png|200px|Pioneer image]] | caption = Image of a man and a woman, sent into space with the ''[[Pioneer 11]]'' mission}} |

|||

| status = {{StatusSecure}} |

|||

{{Taxobox_begin_placement | color = pink}} |

|||

| image = PPlaquecloseup.png |

|||

{{Taxobox_regnum_entry | taxon = [[Animal]]ia}} |

|||

| image_width = 200px |

|||

{{Taxobox_phylum_entry | taxon = [[Chordata]]}} |

|||

| caption = Image of a man and a woman on [[Pioneer plaque]], sent into space with the ''[[Pioneer 11]]'' mission |

|||

{{Taxobox_classis_entry | taxon = [[Mammal]]ia}} |

|||

| regnum = [[Animal]]ia |

|||

{{Taxobox_ordo_entry | taxon = [[Primates]]}} |

|||

| phylum = [[Chordata]] |

|||

{{Taxobox_superfamilia_entry | taxon = [[Hominoidea]]}} |

|||

| classis = [[Mammal]]ia |

|||

{{Taxobox_familia_entry | taxon = [[Hominidae]]}} |

|||

| ordo = [[Primates]] |

|||

{{Taxobox_subfamilia_entry | taxon = [[Homininae]]}} |

|||

| superfamilia = [[Hominoidea]] |

|||

{{Taxobox_tribus_entry | taxon = [[Hominini]]}} |

|||

| familia = [[Hominidae]] |

|||

{{Taxobox_genus_entry | taxon = ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]''}} |

|||

| subfamilia = [[Homininae]] |

|||

{{Taxobox_species_entry | taxon = '''''H. sapiens '''''}} |

|||

| tribus = [[Hominini]] |

|||

{{Taxobox_end_placement}} |

|||

| genus = ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]'' |

|||

{{Taxobox_section_binomial | color = pink | binomial_name = Homo sapiens | author = [[Carolus Linnaeus|Linnaeus]] | date = [[1758]]}} |

|||

| species = '''''H. sapiens ''''' |

|||

{{Taxobox_section_subdivision | color = pink | plural_taxon = Subspecies}} |

|||

'' |

| binomial = ''Homo sapiens'' |

||

| binomial_authority = [[Carolus Linnaeus|Linnaeus]], 1758 |

|||

'''''Homo sapiens sapiens''''' |

|||

| subdivision_ranks = [[Subspecies]] |

|||

{{Taxobox_end}} |

|||

| subdivision = ''[[Homo sapiens idaltu]]'' (extinct)<br /> '''''Homo sapiens sapiens''''' |

|||

:''For other uses, see [[Human (disambiguation)]].'' |

|||

}} |

|||

{{dablink|This article is about modern humans. For other human species, see ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo ''(genus)'']]''. For other uses, see [[Human (disambiguation)]].}} |

|||

<!-- this paragraph is a general introduction--> |

<!-- this paragraph is a general introduction--> |

||

'''Human beings''' define themselves in [[biological]], [[social]], and [[spiritual]] terms. Biologically, humans are classified as the [[species]] '''''Homo sapiens''''' ([[Latin]] for " |

'''Human beings''' define themselves in [[biological]], [[social]], and [[spiritual]] terms. Biologically, humans are classified as the [[species]] '''''Homo sapiens''''' ([[Latin]] for "wise man"): a [[biped]]al [[primate]] of the superfamily [[Hominoidea]], together with the other [[ape]]s—[[chimpanzee]]s, [[gorilla]]s, [[orangutan]]s, and [[gibbon]]s. |

||

Humans have an erect body carriage that frees their upper limbs for manipulating objects and a highly developed [[brain]] capable of abstract [[reason]]ing, [[speech]], [[language]], and [[introspection]]. Bipedal locomotion appears to have [[human evolution|evolved]] before the development of a [[Encephalization|large brain]]. The origins of bipedal locomotion and of its role in the evolution of the [[human brain]] are topics of ongoing research. |

Humans have an erect body carriage that frees their upper limbs for manipulating objects, and a highly developed [[brain]] capable of abstract [[reason]]ing, [[speech]], [[language]], and [[introspection]]. Bipedal locomotion appears to have [[human evolution|evolved]] before the development of a [[Encephalization|large brain]]. The origins of bipedal locomotion and of its role in the evolution of the [[human brain]] are topics of ongoing research. |

||

<!--Each sentence in this paragraph is about a different thing: they don't flow. Can you make it run more smoothly; to start with, a leading sentence is required, and possibly, at the start of each subsequent sentence, a leading phrase to back-reference the previous statement. Not sure.-->The human [[mind]] has several distinct attributes. It is responsible for complex [[behaviour]], especially [[language]]. [[Curiosity]] and [[observation]] have led to a variety of explanations for [[consciousness]] and the relation between mind and [[body]]. [[Psychology]] attempts to study behaviour from a scientific point of view. [[Religious]] perspectives emphasise a [[soul]], [[qi]] or [[atman]] as the essence of [[being]], and are often characterised by the belief in and worship of [[God]], [[gods]] |

<!--Each sentence in this paragraph is about a different thing: they don't flow. Can you make it run more smoothly; to start with, a leading sentence is required, and possibly, at the start of each subsequent sentence, a leading phrase to back-reference the previous statement. Not sure.-->The human [[mind]] has several distinct attributes. It is responsible for complex [[behaviour]], especially [[language]]. [[Curiosity]] and [[observation]] have led to a variety of explanations for [[consciousness]] and the relation between mind and [[body]]. [[Psychology]] attempts to study behaviour from a scientific point of view. [[Religious]] perspectives emphasise a [[soul]], [[qi]] or [[atman]] as the essence of [[being]], and are often characterised by the belief in and worship of [[God]], [[gods]] or [[spirit]]s. [[Philosophy]], especially [[philosophy of mind]], attempts to fathom the depths of each of these perspectives. [[Art]], [[music]] and [[literature]] are often used in expressing these concepts and [[feelings]]. |

||

Like all primates, humans are inherently [[society|social]]. They create complex [[sociology|social structures]] composed of [[co-operation|co-operating]] and [[competition|competing]] groups. These range from [[nation]]s and [[state]]s down to [[Family|families]], and from the [[community]] to the [[self]]. Seeking to [[understand]] and [[manipulate]] the world around them has led to the development of [[technology]] and [[science]]. [[Artifact (archaeology)|Artifacts]], [[belief]]s, [[myths]], [[ritual]]s, [[values]], and [[norm (sociology)|social norms]] have |

Like all primates, humans are inherently [[society|social]]. They create complex [[sociology|social structures]] composed of [[co-operation|co-operating]] and [[competition|competing]] groups. These range from [[nation]]s and [[state]]s down to [[Family|families]], and from the [[community]] to the [[self]]. Seeking to [[understand]] and [[manipulate]] the world around them has led to the development of [[technology]] and [[science]]. [[Artifact (archaeology)|Artifacts]], [[belief]]s, [[myths]], [[ritual]]s, [[values]], and [[norm (sociology)|social norms]] have each played a role in forming humanity's [[culture]]. |

||

==Terminology== |

==Terminology== |

||

[[Image:Inuit women 1907.jpg|thumb|left|A [[Inuit]] woman, circa 1907.]] |

|||

In general, the word |

In general, the word "people" is a collective or plural term for any specific group of individual [[person]]s. However, when used to refer to a group of humans possessing a common [[Ethnic group|ethnic]], cultural or national unitary characteristic or identity, "people" is a singular count noun, and as such takes an "s" in the plural (examples: "the English-speaking peoples of the world", "the indigenous peoples of Brazil"). |

||

Juvenile males are called [[boy]]s, adult males [[man|men]], juvenile females [[girl]]s, and adult females [[woman|women]]. Humans are commonly referred to as [[person]]s or people, and collectively as Man (capital M), mankind, humankind, humanity, or the human race. Until the 20th century, "human" was only used adjectivally ("pertaining to mankind"). Nominal use of "human" (plural "humans") is short for "human being", and not considered good style in traditional English grammar. As an adjective, "human" is used neutrally (as in "human race"), but "human" and especially "humane" may also emphasise positive aspects of [[human nature]], and can be synonymous with "benevolent" (versus "inhumane"; cf. [[humanitarian]]). |

|||

[[Image:Inuit women 1907.jpg|thumb|right|[[Inuit]] woman (c.1907)]] |

|||

A distinction is maintained in [[philosophy]] and [[law]] between the notions "human being", or "man", and "person". The former refers to the species, while the latter refers to a [[rational agent]] (see, for example, [[John Locke]]'s ''Essay concerning Human Understanding'' II 27 and [[Immanuel Kant]]'s ''Introduction to the Metaphysic of Morals''). The term "person" is thus used of non-human [[animal]]s, and could be used of a [[mythical being]], an [[artificial intelligence]], or an [[extraterrestrial]]. An important question in [[theology]] and the [[philosophy of religion]] concerns whether God is a person. |

|||

Juvenile males are called [[boy]]s, adult males [[man|men]], juvenile females [[girl]]s, and adult females [[woman|women]]. Humans are commonly referred to as ''[[person]]s'' or ''[[people]]'' and collectively as ''Man'' (capital M), ''mankind'', ''humanity'', or ''the human race''. Until the [[20th century]], ''human'' was only used adjectivally ("pertaining to mankind"). Nominal use of ''human'' (plural ''humans'') is short for ''human being'', and not to be considered good style in traditional English grammar. As an adjective, ''human'' is used neutrally (as in ''human race''), but ''human'' and especially ''humane'' may also emphasise positive aspects of [[human nature]], and can be synonymous with ''benevolent'' (versus ''inhumane''; c.f. ''[[humanitarian]]''). |

|||

In [[Latin language|Latin]], "''humanus''" is the adjectival form of the noun "''homo''", translated as "man" (to include males and females). The [[Old English language|Old English]] word "man" could also have this generic meaning, as demonstrated by such compounds as "''wifman''" ("female person") → "''wiman''" → "''woman''". For the etymology of "man" see [[mannaz]]. |

|||

A distinction is maintained in [[philosophy]] and [[law]] between the notions "human being", or "man", and "person". The former refers to the species, while the latter refers to a [[rational agent]] (see, for example, [[John Locke]]'s ''Essay concerning Human Understanding'' II 27 and [[Immanuel Kant]]'s ''Introduction to the Metaphysic of Morals''). The term "person" is thus used of non-human [[animal]]s, and could be used of a [[mythical being]], an [[artificial intelligence]], or an [[extraterrestrial]]. An important question in [[theology]] and the [[philosophy of religion]] concerns whether [[God]] is a person. |

|||

In [[Latin language|Latin]], ''humanus'' is the adjectival form of the noun ''homo'', translated as "man" (to include males and females). The [[Old English language|Old English]] word ''[[man]]'' could also have this generic meaning, as demonstrated by such compounds as ''wifman'' (“female person”) → ''wiman'' → ''woman''. For the etymology of '''man''' see [[mannaz]]. |

|||

==Biology== |

==Biology== |

||

{{main|Human biology}} |

|||

=== |

===Anatomy and physiology=== |

||

{{main articles|[[Human anatomy]], [[Human physical appearance]], and [[Human height]]}} |

|||

[[Image:Skeleton_diag.png|thumbnail|140px|right|An old diagram of a male [[human skeleton]].]] |

|||

Human body types varies substantially, with many individuals diverging significantly from the mean height and weight. Some of this variation is caused by locality and historical factors. Although body size is largely determined by [[gene]]s, it is also significantly influenced by [[diet (nutrition)|diet]] and [[exercise]]. The mean height of a North American adult female is 162 [[metre|centimetres]] (5 feet 4 inches), and the mean weight is 62 [[kilogram]]s (137 [[pound (mass)|pound]]s). Human males are typically larger than females: the mean height and weight of a North American adult male is 175 centimetres (5 feet 9 inches) and 78 kilograms (172 pounds). |

|||

[[Image:Skeleton_diag.png|thumbnail|140px|left|A vintage diagram of a male [[human skeleton]]]] |

|||

[[Image:Anatomical_Man.jpg|thumbnail|195px|right|Anatomical Man, Musée Condé, [[Chantilly]]]] |

|||

{{main3|Human anatomy|Human physical appearance|Human height}} |

|||

Although human [[skin]] appears relatively hairless compared to that of other primates, with notable hair growth occurring chiefly on the top of the head, the average human has a larger number of hairs on his or her body than the average [[chimpanzee]]. The main distinction is that human hairs are shorter, finer, and less coloured than the average chimpanzee's, thus rendering them harder to see. The colour of human hair and skin is determined by the presence of coloured pigments called [[melanin]]s. Human skin colour can range from very dark brown to very pale pink, while human hair ranges from [[blond]] to [[brown hair|brown]] to [[red hair|red]]. Most researchers believe that skin darkening was an adaptation that evolved as a defence against [[ultraviolet]] [[solar radiation]]; melanin is an effective sunblock. The skin colour of contemporary humans is geographically stratified, and in general correlates with the environmental level of ultraviolet radiation. Human skin and hair colour is controlled in part by the genes [[Mc1r]] and [[SLC24A5]]. For example, the red hair and pale skin of some Europeans is the result of [[mutation]]s in Mc1r. Human skin has a capacity to darken ([[sun tanning]]) in response to exposure to ultraviolet radiation; this is also controlled in part by Mc1r. |

|||

[[Image:2005 World Championships in Athletics 4.jpg.JPG|300px|left|thumb|Humans [[walking]] briskly in a [[race walking|race]]. The upright, [[biped]]al [[gait (human)|gait]] of humans distinguishes them from other [[primate]]s.]] |

|||

Humans exhibit fully [[bipedal locomotion]]. This leaves the forelimbs available for manipulating objects using [[opposable thumb]]s. |

|||

Humans are capable of fully [[biped]]al locomotion, walking upright on two legs. This leaves the forelimbs available for manipulating objects using their [[hand]]s, aided especially by opposable [[thumb]]s. Because humans are bipedal, the pelvic region and spinal column tend to become worn, creating locomotion difficulties in old age. |

|||

Humans vary substantially around the mean height and mean weight. Some of this variation is explained by locality and historical factors. Although body size is largely determined by genes, it is also significantly influenced by [[diet (nutrition)|diet]] and exercise. The mean height of a North American adult female is 162 [[centimetre|cm]] (5'4") and the mean weight is 62 [[kilogram|kg]] (137 [[pound|lb]]). North American adult males are typically larger: 175 cm (5'9") and 78 kilograms (172 lb). |

|||

The individual need for regular intake of [[food]] and [[drink]] is prominently reflected in human culture, and has led to the development of [[food science]]. Failure to obtain food leads to [[hunger]] and eventually [[starvation]], while failure to obtain water leads to [[dehydration]] and [[thirst]]. Both starvation and dehydration cause [[death]] if not alleviated.<!-- The following needs clarification: "human beings can survive for over two months without food, but only up to around fourteen days without water". Some foods contain enough water to make the water unnecessary. If these "fourteen days" mean living with food that contains no water (by burning lipids producing in result water) then this is much more severe restriction than just living without water. Or if it means living on an usual food diete but just without drinking water then this should be clarified. --><!--I think it means what it says: that if you stop eating, but continue drinking water, you can survive for over two months. But if you stop eating and stop drinking water, you're unlikely to survive for more than 14 days.--> In modern times, [[obesity]] amongst some human populations has increased to almost [[epidemic]] proportions, leading to health complications and increased [[mortality]] in some [[developed country|developed countries]], and is becoming problematic elsewhere. |

|||

Human skin appears to be relatively hairless in comparison to other primates; however, most humans have a larger number of hairs on their body than a [[chimpanzee]]. The main difference is that human hairs are shorter, finer, and less coloured then the average chimpanzee's, thus rendering them harder to see. |

|||

It is sometimes said that the average [[sleep]] requirement is between seven and eight hours a day for an adult and nine to ten hours for a child. More accurately, negative effects result from restriction of sleep. For instance a sustained restriction of adult sleep to four hours per day has been shown to correlate with changes in variables, including tiredness-fatigue, anger-aggression, and bodily discomfort. Normative data suggests elderly people usually sleep for six to seven hours, although such normative data varies depending upon the sociocultural characteristics of the population. It is common in [[modern]] societies for people to get less sleep than they need to avoid adverse effects, leading to a state of [[sleep deprivation]]. |

|||

The colour of human hair and skin is determined by the presence of coloured pigments called [[melanin]]s. Most researchers believe that skin darkening was an adaptation that evolved as a defence against [[UV]] solar radiation; melanin is an effective sunblock. The skin colour of contemporary humans can range from very dark brown to very pale pink. It is geographically stratified and in general correlates with the environmental level of UV. Human skin and hair colour is controlled in part by the [[Mc1r|MC1R]] gene. For example, the [[red hair]] and pale skin of some Europeans is the result of [[mutation]]s in MC1R. Human skin has a capacity to darken ([[sun tanning]]) in response to UV exposure. Variation in the ability to sun tan is also controlled in part by MC1R. |

|||

Because humans are [[bipedal]], the pelvic region and spinal column tend to get worn, creating locomotion difficulties in old age. |

|||

The individual need for regular intake of [[food]] and [[drink]] is prominently reflected in human culture, and has led to the development of [[food science]]. Failure to obtain food leads to [[hunger]] and eventually [[starvation]], while failure to obtain water leads to [[dehydration]] and [[thirst]]. Both starvation and dehydration cause [[death]] if not alleviated: human beings can survive for over two months without food, but only up to around 14 days without water. |

|||

The average [[sleep]] requirement is between seven and eight hours a day for an adult and nine to ten hours for a child. Elderly people usually sleep for six to seven hours. It is common, however, in [[modern]] societies for people to get less sleep than they need, leading to a state of [[sleep deprivation]]. |

|||

The human body is subject to an [[ageing]] process and to [[illness]]. [[Medicine]] is the science that explores methods of preserving bodily [[health]]. |

|||

===Life cycle=== |

===Life cycle=== |

||

[[Image:Fetus.png|thumb|right|180px|Human [[fetus]]]] |

[[Image:Fetus.png|thumb|right|180px|Human [[fetus]]]] |

||

The human [[biological life cycle|life cycle]] is similar to that of other [[placenta]]l [[mammal]]s. New human life develops [[vivipary|viviparously]] from [[fertilisation|conception]]. An [[Ovum|egg]] is usually fertilised inside the female by [[sperm]] from the male through [[sexual intercourse]], though [[in vitro fertilisation]] methods are also used. The fertilised egg is called a [[zygote]]. The zygote divides inside the female's [[uterus]] to become an [[embryo]] which over a period of thirty-eight weeks becomes the [[fetus]]. At birth, the fully grown fetus is expelled from the female's body and breathes independently as a [[baby]] for the first time. At this point, most modern cultures recognise the baby as a person entitled to the full protection of the [[law]], though some jurisdictions extend [[personhood]] to human fetuses while they remain in the uterus. |

|||

The human [[biological life cycle|life cycle]] is similar to that of other [[placenta]]l [[mammal]]s. New human [[life]] develops from [[fertilisation|conception]]. An [[Ovum|egg]] is usually fertilised inside the female by [[sperm]] from the male through [[sexual intercourse]], though [[In vitro fertilisation|''in vitro'']] fertilisation methods are also used. The fertilized egg is called a [[zygote]]. The zygote divides inside the female's [[uterus]] to become an [[embryo]] which over a period of 38 weeks becomes the [[foetus]]. At birth, the fully grown foetus is expelled from the female's body and breathes independently as a [[baby]] for the first time. At this point, most modern cultures recognise the baby as a [[person]] entitled to the full protection of the [[law]], though some jurisdictions extend [[personhood]] to human foetuses while they remain in the uterus. |

|||

Compared with that of other species, human [[childbirth]] is relatively complicated. Painful labours lasting twenty-four hours or more are not uncommon, and may result in [[birth trauma|injury]] to the child or the death of the mother, although the chances of a successful labour increased significantly during the twentieth century in wealthier countries. [[Natural childbirth]] remains an arguably more dangerous ordeal in remote, underdeveloped regions of the world, though the women who live in these regions have argued that their natural childbirth methods are safer and less traumatic for mother and child. |

Compared with that of other species, human [[childbirth]] is relatively complicated. Painful labours lasting twenty-four hours or more are not uncommon, and may result in [[birth trauma|injury]] to the child or the death of the mother, although the chances of a successful labour increased significantly during the twentieth century in wealthier countries. [[Natural childbirth]] remains an arguably more dangerous ordeal in remote, underdeveloped regions of the world, though the women who live in these regions have argued that their natural childbirth methods are safer and less traumatic for mother and child. |

||

[[Image:Two young girls at Camp Christmas Seals.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Two young girls]] |

[[Image:Two young girls at Camp Christmas Seals.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Two young girls]] |

||

Human children are born after a nine-month [[gestation]] period, with typically 3–4 kilograms (6–9 pounds) in weight and 50–60 centimetres (20–24 inches) in height in developed countries. [http://www.childinfo.org/eddb/lbw] Helpless at birth, they continue to grow for some years, typically reaching [[sexual maturity]] at twelve to fifteen years of age. Boys continue growing for some time after this, reaching their maximum height around the age of eighteen. These values vary too, depending on genes and environment. |

|||

Human children are born after a nine-month [[gestation]] period, with typically 3–4 kilograms (6–9 pounds) in weight and 50–60 centimetres (20–24 inches) in height in developed countries. [http://www.childinfo.org/eddb/lbw] Helpless at birth, they continue to grow for some years, typically reaching [[sexual maturity]] at 12–15 years of age. Boys continue growing for some time after this, reaching their maximum height around the age of 18. These values vary too, depending on genes and environment. |

|||

The human lifespan can be split into a number of stages: [[infancy]], [[childhood]], [[adolescence]], [[young adulthood]], [[maturity]] and [[old age]], though the lengths of these stages, especially the later ones, are not fixed. |

The human lifespan can be split into a number of stages: [[infancy]], [[childhood]], [[adolescence]], [[young adulthood]], [[maturity]] and [[old age]], though the lengths of these stages, especially the later ones, are not fixed. |

||

There are striking differences in [[life expectancy]] around the world. The developed world is quickly getting older, with the median age around 40 years (highest in [[Monaco]] at 45.1 years), while in the [[third world|developing world]], the median age is 15–20 years (the lowest in [[Uganda]] at 14.8 years). Life expectancy at birth is 77.2 years in the U.S. as of |

There are striking differences in [[life expectancy]] around the world. The developed world is quickly getting older, with the median age around 40 years (highest in [[Monaco]] at 45.1 years), while in the [[third world|developing world]], the median age is 15–20 years (the lowest in [[Uganda]] at 14.8 years). Life expectancy at birth is 77.2 years in the U.S. as of 2001. [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lifexpec.htm] The expected life span at birth in [[Singapore]] is 84.29 years for a female and 78.96 years for a male, while in [[Botswana]], due largely to [[AIDS]], it is 30.99 years for a male and 30.53 years for a female. One in five [[European]]s, but one in twenty [[African]]s, is 60 years or older, according to ''The World Factbook''. [http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook] |

||

[[Image:Wheeler.jpg|right|thumb|250px|A [[man]] with a full [[beard]].]] |

[[Image:Wheeler.jpg|right|thumb|250px|A [[man]] with a full [[beard]].]] |

||

The number of [[centenarian]]s in the world was estimated by the [[United Nations]] [http://www.un.org/ageing/note5713.doc.htm] at 210,000 in |

The number of [[centenarian]]s in the world was estimated by the [[United Nations]] [http://www.un.org/ageing/note5713.doc.htm] at 210,000 in 2002. The [[maximum life span]] that humans have acheived thus far is thought to be over 120 years. Worldwide, there are 81 men aged 60 or over for every 100 women, and among the oldest, there are 53 men for every 100 women. |

||

The philosophical questions of when human personhood begins and whether it persists after |

The philosophical questions of when human personhood begins and whether it persists after death are the subject of considerable debate. The prospect of death may cause unease or fear. People who are near death sometimes report having a [[near-death experience]], in which they have visions. [[Burial]] ceremonies are characteristic of human societies, often inspired by beliefs in an [[afterlife]]. Institutions of [[inheritance]] or [[ancestor worship]] may extend an individual's presence beyond his physical lifespan (see [[immortality]]). |

||

===Genetics=== |

===Genetics=== |

||

{{main|Genetics of humans}} |

{{main|Genetics of humans}} |

||

Humans are a [[eukaryote|eukaryotic]] species. Each [[diploid]] [[cell (biology)|cell]] has two sets of 23 [[chromosome]]s, each set received from one parent. There are 22 pairs of [[autosome]]s and one pair of [[sex chromosome]]s. At present estimate, humans have approximately 20,000–25,000 [[gene]]s and share 95% of their [[DNA]] with their closest living evolutionary relatives, the two species of [[chimpanzee]]s. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12368483] Like other [[mammal]]s, humans have an [[XY sex determination system]], so that |

Humans are a [[eukaryote|eukaryotic]] species. Each [[diploid]] [[cell (biology)|cell]] has two sets of 23 [[chromosome]]s, each set received from one parent. There are 22 pairs of [[autosome]]s and one pair of [[sex chromosome]]s. At present estimate, humans have approximately 20,000–25,000 [[gene]]s and share 95% of their [[DNA]] with their closest living evolutionary relatives, the two species of [[chimpanzee]]s. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12368483] Like other [[mammal]]s, humans have an [[XY sex determination system]], so that [[female]]s have the sex chromosomes XX and [[male]]s have XY. The X chromosome is larger and carries many genes not on the Y chromosome, which means that [[recessive gene|recessive]] diseases associated with X-linked genes affect men more often than women. For example, genes that control the clotting of [[blood]] reside on the X chromosome. Women have a blood-clotting gene on each X chromosome so that one normal blood-clotting gene can compensate for a flaw in the gene on the other X chromosome. But men are [[hemizygote|hemizygous]] for the blood-clotting gene, since there is no gene on the Y chromosome to control blood clotting. As a result, men will suffer from [[haemophilia]] more often than women. |

||

===Race and ethnicity=== |

===Race and ethnicity=== |

||

{{ |

{{main articles|[[Race]] and [[Ethnic group]]}} |

||

[[Image:RaceMugshots.jpg|thumb| |

[[Image:RaceMugshots.jpg|thumb|350px|The [[Federal Bureau of Investigation|FBI]] identifies fugitives by sex, physical features, occupation, nationality, and race. From left to right, the FBI identifies the above as belonging to the following races: [[White]], [[Black]], [[Hispanic]], and [[Asian]]. Top row males, bottom row females.]] |

||

Humans often categorise themselves and others in terms of [[race]] or [[ethnicity]]. |

Humans often categorise themselves and others in terms of [[race]] or [[ethnicity]], although the [[validity of human races]] is disputed. The most widely used human racial categories are based on visible [[trait]]s (especially [[skin color]] and [[face|facial features]]), [[genes]], and self-identification. [[Language]] and [[ethnicity]], [[blood type]], [[ancestry]], and other factors are also sometimes considered. Self identification with an ethnic group is based on [[kinship and descent]], as well as presumed advantage. When race and ethnicity often lead to variant treatment and impact [[social identity]], giving rise to the theory of [[identity politics]]. |

||

An [[ethnic group]] is a [[culture]] or [[subculture]] whose members are readily distinguishable by outsiders based on traits originating from a common [[racial]], [[nation]]al, [[linguistic]], regional or [[religious]] source. Members of an ethnic group are often presumed to be culturally or [[genetically]] similar, although this is not in fact necessarily the case. |

|||

Although most humans recognise that variances occur within a species, it is often a point of dispute as to what these differences entail, and if discrimination based on race ([[racism]]) is acceptable in the early twenty-first century. [[Race and intelligence]], [[scientific racism]] and [[ethnocentrism]] are some of the many justifications for such practices. |

|||

Although most humans recognise that variances occur within a species, it is often a point of dispute as to what these differences entail, their import, and if discrimination based on race ([[racism]]) is acceptable. [[Race and intelligence]], [[scientific racism]], [[xenophobia]] and [[ethnocentrism]] are just a few of the many bases for such practices. |

|||

===Habitat=== |

|||

Some societies have placed a great deal of emphasis on race, others have not. Two extremes include [[ancient egypt]], and the [[racial policy of Nazi Germany]].<br clear="right" /> |

|||

The conventional view of human evolution states that humans evolved in inland [[savanna]] environments in Africa. (See [[Human evolution]], [[Vagina gentium]], [[Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness]].) Technology has allowed humans to colonise all of the [[continents]] and adapt to all climates. Within the last few decades, humans have been able to explore [[Antarctica]], the [[ocean]] depths, and [[space colonization|space]], although long-term habitation of these environments are not yet possible. Humans, with a population of about six billion, are one of the most numerous [[mammal]]s on Earth. |

|||

[[Image:Races all(modern).JPG|thumb|500px|center|The five human racial divisions proposed in [[Carleton Coon]]'s ''The Origin of Races'' (1962)]] |

|||

Most humans (61%) live in the [[Asia]]n region. The vast majority of the remainder live in the [[Americas]] (14%), [[Africa]] (13%) and [[Europe]] (12%), with only 0.3% in Australia. (See [[list of countries by population]] and [[list of countries by population density]].) |

|||

===Habitat=== |

|||

The view most widely accepted by the anthropological community is that the human species originated in the African savanna between 100 and 200 thousand years ago, had colonised the rest of the [[Old World]] and [[Oceania]] by 40,000 years ago, and finally colonised the Americas by 10,000 years ago. Homo sapiens displaced groups such as [[Neanderthals]] and [[Homo floresiensis]] through more successful reproduction and competition for resources, and/or extermination. (See [[Human evolution]], [[Vagina gentium]], and [[Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness]].) Technology has allowed humans to colonise all of the [[continents]] and adapt to all climates. Within the last few decades, humans have been able to explore [[Antarctica]], the [[ocean]] depths, and [[space colonization|space]], although long-term habitation of these environments are not yet possible. Humans, with a population of over six billion, are one of the most numerous [[mammal]]s on Earth. |

|||

Most humans (61%) live in the [[Asia]]n region. The vast majority of the remainder live in the [[Americas]] (14%), [[Africa]] (13%) and [[Europe]] (12%), with 5% in [[Oceania]]. (See [[list of countries by population]] and [[list of countries by population density]].) |

|||

[[Image:Map-of-human-migrations.jpg|thumb|350px|Map of early human migrations according to [[Mitochondrial DNA|mitochondrial]] [[population genetics]] (The [[arctic]] is at the centre of the map and the numbers are [[millennia]] before present).]] |

[[Image:Map-of-human-migrations.jpg|thumb|350px|Map of early human migrations according to [[Mitochondrial DNA|mitochondrial]] [[population genetics]] (The [[arctic]] is at the centre of the map and the numbers are [[millennia]] before present).]] |

||

The original human lifestyle is [[Hunter-gatherer|hunting-gathering]], which is adapted to the savanna. Other human lifestyles are [[nomad]]ism (often linked to animal herding) and permanent settlements made possible by the development of agriculture. Humans have a great capacity for altering their [[habitat (ecology)|habitats]] by various methods, such as [[agriculture]], [[irrigation]], [[urban planning]], [[construction]], [[transport]], and [[manufacturing]] goods. |

The original human lifestyle is [[Hunter-gatherer|hunting-gathering]], which is adapted to the savanna. Other human lifestyles are [[nomad]]ism (often linked to animal herding) and permanent settlements made possible by the development of agriculture. Humans have a great capacity for altering their [[habitat (ecology)|habitats]] by various methods, such as [[agriculture]], [[irrigation]], [[urban planning]], [[construction]], [[transport]], and [[manufacturing]] goods. |

||

Permanent human settlements are dependent on proximity to [[water]] and, depending on the lifestyle, other natural resources such as fertile land for growing [[crops]] and grazing [[livestock]], or seasonally by populations of [[hunting|prey]]. With the advent of large-scale trade and transport infrastructure, immediate proximity to these resources has become unnecessary, and in many places these factors are no longer the driving force behind growth and decline of population. |

Permanent human settlements are dependent on proximity to [[water]] and, depending on the lifestyle, other natural resources such as fertile land for growing [[agriculture|crops]] and grazing [[livestock]], or seasonally by populations of [[hunting|prey]]. With the advent of large-scale trade and transport infrastructure, immediate proximity to these resources has become unnecessary, and in many places these factors are no longer the driving force behind growth and decline of population. |

||

Human habitation within [[closed ecological system]]s in hostile environments ([[Antarctica]], [[outer space]]) is expensive, typically limited in duration, and restricted to scientific, military, or industrial expeditions. Life in space has been very sporadic, with a maximum of thirteen humans in space at any given time, starting with [[Yuri Gagarin]]'s space flight in |

Human habitation within [[closed ecological system]]s in hostile environments ([[Antarctica]], [[outer space]]) is expensive, typically limited in duration, and restricted to scientific, military, or industrial expeditions. Life in space has been very sporadic, with a maximum of thirteen humans in space at any given time, starting with [[Yuri Gagarin]]'s space flight in 1961. Between 1969 and 1972, up to two humans at a time spent brief intervals on the [[Moon]]. [[As of 2005]], no other [[astronomical object|celestial body]] has been visited by human beings, although there has been a continuous human presence in space since the launch of the initial crew to inhabit the [[International Space Station]] on [[October 31]], [[2000]]. |

||

=== |

===Food and drink=== |

||

{{Meals}} |

|||

[[Image:Earthlights dmsp.jpg|thumb|right|350px|City lights from space.]] |

|||

Humans are commonly believed to be [[omnivore|omnivorous]] animals that can consume both plant and animal products. Evidence suggests that early [[Homo Sapiens]] employed ''[[Hunter-gatherer]]'' as their primary means of food collection. This involves combining stationary plant and fungal food sources (such as [[fruit]]s, [[grains]], [[tuber]]s, and [[mushrooms]]) with [[wild game]] which must be hunted and killed in order to be consumed. Additionally, it is believed that humans have used [[fire]] to prepare food prior to eating since their divergence from [[Homo erectus]], possibly even earlier. |

|||

From [[1800]] to 2000, [[world human population|the human population]] increased from one to six [[billion]]. It is expected to crest at around ten billion during the [[21st century]]. [[As of 2004]], around 2.5 billion out of 6.3 billion people live in [[urban area|urban]] centres, and this is expected to rise during the 21st century. Problems for humans living in [[city|cities]] include various forms of [[pollution]], [[crime]], and [[poverty]], especially in inner city and [[suburb]]an slums. |

|||

At least ten thousand years ago, humans developed [[agriculture]], which has [[Timeline of agriculture and food technology|altered substantially the kind of food people eat]]. This has led to a variety of important historical consequences, such as increased [[population]], the development of [[cities]], and the wider spread of [[infectious disease]]s. The types of food consumed, and the way in which they are prepared has varied widely by time, location, and culture. |

|||

[[Genetics|Geneticists]] Lynn Jorde and Henry Harpending of the [[University of Utah]] have concluded that the variation in the total stock of human [[DNA]] is minute compared to that of other species; and that around 74,000 years ago, human population was reduced to a small number of breeding pairs, possibly as small as 1000, resulting in a very small residual gene pool. Various reasons for this bottleneck have been postulated, the most popular, called the [[Toba catastrophe theory]], being the eruption of a volcano at [[Lake Toba]]. |

|||

The last century or so has produced enormous improvements in food production, preservation, storage and shipping. Today almost every locale in the world has access to not only its traditional cuisine, but also to many other world cuisines, as well. New cuisines are constantly evolving, as certain aesthetics rise and fall in popularity among professional [[chef|chefs]] and their clientele. |

|||

In addition to [[food]], a [[cuisine]] is also often held to include [[beverage|beverages]], including [[wine]], [[liquor]], [[tea]], [[coffee]] and other drinks. |

|||

There are also different cultural attitudes to food, for example: |

|||

* In [[India]], consumption of food is regarded as an offering, a ''[[Yajna]]''. Thus the stomach is considered to be a ''homagunda'' (holy fire) and all the food consumed is an offering to the holy fire. |

|||

* In [[Japan]], [[Tea]] drinking is a fine-art and there is an elaborate ceremony about it. Not drinking tea in the right way is considered to be an act of barbarism. |

|||

* Some persons are [[vegetarian]], refusing to consume [[animal]] [[meat]], and sometimes [[animal products]] (this varies). Many others consume [[fast food]] at rates alarming to [[dietician]]s. |

|||

===Population=== |

|||

{{main|World population}} |

|||

From 1800 to 2000, the human population increased from one to six [[billion]]. It is expected to crest at around ten billion during the 21st century. In 2004, around 2.5 billion out of 6.3 billion people lived in [[urban area]]s, and this is expected to rise during the 21st century. Problems for humans living in [[city|cities]] include various forms of [[pollution]], [[crime]], and [[poverty]], especially in inner city and [[suburb]]an slums. |

|||

[[Genetics|Geneticists]] Lynn Jorde and [[Henry Harpending]] of the [[University of Utah]] have concluded that the variation in the total stock of human [[DNA]] is minute compared to that of other species; and that around 74,000 years ago, human population was reduced to a small number of breeding pairs, possibly as small as 1000, resulting in a very small residual gene pool. Various reasons for this bottleneck have been postulated, the most popular, called the [[Toba catastrophe theory]], being the eruption of a volcano at [[Lake Toba]]. |

|||

===Human evolution=== |

|||

{{main2|Human evolution|Human migration}} |

|||

===Evolution=== |

|||

{{main articles|[[Human evolution]] and [[Human migration]]}} |

|||

The study of [[human evolution]] encompasses many scientific disciplines, but most notably [[physical anthropology]] and [[genetics]]. The term "human", in the context of human evolution, refers to the genus ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]'', but studies of human evolution usually include other [[hominid]]s and [[hominine]]s, such as the [[australopithecines]]. |

The study of [[human evolution]] encompasses many scientific disciplines, but most notably [[physical anthropology]] and [[genetics]]. The term "human", in the context of human evolution, refers to the genus ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]'', but studies of human evolution usually include other [[hominid]]s and [[hominine]]s, such as the [[australopithecines]]. |

||

Biologically, humans are defined as hominids of the [[species]] ''Homo sapiens'', of which the only extant [[subspecies]] is ''Homo sapiens sapiens''. |

Biologically, humans are defined as hominids of the [[species]] ''Homo sapiens'', of which the only extant [[subspecies]] is ''Homo sapiens sapiens'' (Latin for "very wise man"); ''[[Homo sapiens idaltu]]'' (roughly translated as "elderly wise man") is the extinct subspecies. Modern humans are usually considered the only surviving species in the genus ''Homo'', although some argue that the two species of chimpanzees should be reclassified from ''[[Pan troglodytes]]'' (Common Chimpanzee) and ''[[Pan paniscus]]'' (Bonobo/Pygmy Chimpanzee) to ''Homo troglodytes'' and ''Homo paniscus'' respectively, given that they share a recent ancestor with man. [http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/05/0520_030520_chimpanzees.html] |

||

{{Human Evolution}} |

|||

Full genome sequencing resulted in these conclusions: "After 6 [million] years of separate evolution, the differences between chimp and human are just 10 times greater than those between two unrelated people and 10 times less than those between rats and mice." [http://news.ft.com/cms/s/43445728-1a44-11da-b279-00000e2511c8.html Chimp and human DNA is 96% identical] |

Full genome sequencing resulted in these conclusions: "After 6 [million] years of separate evolution, the differences between chimp and human are just 10 times greater than those between two unrelated people and 10 times less than those between rats and mice." [http://news.ft.com/cms/s/43445728-1a44-11da-b279-00000e2511c8.html Chimp and human DNA is 96% identical] |

||

It has been estimated that the human [[Lineage (evolution)|lineage]] diverged from that of chimpanzees about five million years ago, and from gorillas about eight million years ago. However, in |

It has been estimated that the human [[Lineage (evolution)|lineage]] diverged from that of chimpanzees about five million years ago, and from gorillas about eight million years ago. However, in 2001 a hominine skull approximately seven million years old, classified as ''[[Sahelanthropus tchadensis]]'', was discovered in [[Chad]] and seems to indicate an earlier divergence. |

||

Two prominent scientific theories of the origins of contemporary humans exist. They concern the relationship between modern humans and other hominids: |

Two prominent scientific theories of the origins of contemporary humans exist. They concern the relationship between modern humans and other hominids: |

||

The [[single-origin hypothesis|single-origin]] or "[[out of |

The [[single-origin hypothesis|single-origin]] or "[[out of Africa]]" hypothesis proposes that modern humans evolved in Africa and later replaced hominids in other parts of the world. |

||

The [[multiregional hypothesis]] proposes that modern humans evolved at least in part from independent hominid populations. |

The [[multiregional hypothesis]] proposes that modern humans evolved at least in part from independent hominid populations. |

||

| Line 145: | Line 157: | ||

* descent of the [[larynx]], which makes speech possible. |

* descent of the [[larynx]], which makes speech possible. |

||

Humans are classified as |

Humans are classified as ''Homo sapiens sapiens''. A camp of physical anthropologists see ''neanderthalensis'' as a subspecies and classify the neanderthals as ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''. A second camp of physical anthropologists see the neanderthals as a distinct species diverging from the modern human lineage over 500,000 years ago. Under this classification, neaderthals are ''Homo neanderthalensis''. Recent DNA analysis suggests that ''neanderthalensis'' were not a subspecies. |

||

How these trends are related and what their role is in the evolution of complex social organisation and culture are matters of ongoing debate. |

How these trends are related and what their role is in the evolution of complex social organisation and culture are matters of ongoing debate. |

||

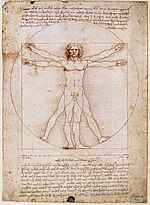

[[Image:Vitruvian.jpg|right|thumb|150px|[[Leonardo da Vinci]]'s [[Vitruvian Man]]]] |

|||

===Intelligence=== |

===Intelligence=== |

||

{{main|Intelligence (trait)}} |

{{main|Intelligence (trait)}} |

||

[[Image:Vitruvian.jpg|right|thumb|150px|[[Leonardo da Vinci]]'s [[Vitruvian Man]].]] |

|||

Human beings are the most intelligent living being, animal or otherwise on Earth. While other animals are capable of creating structures (mostly as a result of [[instinct]]) and using tools, human technology is in a class by itself, constantly evolving and improving with time. Indeed, even the most ancient human tools, and structures are far more advanced than any structure or tool created by another animal. In terms of [[brain to body mass ratio]], humans are the second highest ratio. While some consider this a good measure of intelligence, the [[tree shrew]] which is ranked with the highest ratio, directly contradicts this notion, because it is far less intelligent than even animals with lower brain to body mass ratios than humans. |

|||

Most humans consider their species to be the most intelligent in the animal kingdom. Certainly, humans are the only technologically advanced animal. Along with the brain's internal complexity, the [[brain to body mass ratio]] is generally assumed to be a good indicator of relative intelligence. Humans have the second highest ratio, with the [[tree shrew]] having the highest [http://www.hindustantimes.com/news/181_935198,00300006.htm], and the [[bottlenose dolphin]] very similar to humans. |

|||

The human ability to abstract may be unparalleled in the animal kingdom. Human beings are one of five species to pass the [[mirror test]] |

The human ability to abstract may be unparalleled in the animal kingdom. Human beings are one of five species to pass the [[mirror test]] — which tests whether an animal recognises its reflection as an image of itself — along with [[chimpanzee]]s or [[bonobo]]s, [[orangutan]]s, and [[dolphin]]s. Human beings under the age of 2 usually fail the test[http://www.ulm.edu/~palmer/ConsciousnessandtheSymbolicUniverse.htm]. <!--Other intelligence tests show that a fully grown chimpanzee has approximately the same ability to abstract as a four-year-old human child.--><!--And it may be reasonably argued that the some children may have encountered mirrors more frequently and noted discrepancies by older ages, when self-care becomes more common.--> |

||

==Culture== |

==Culture== |

||

{{ |

{{main articles|[[Culture of human beings]] and [[Culture]]}} |

||

[[Image:Lascaux.jpg|thumb|280px|Cave art - [[Lascaux]], [[France]]]] |

|||

[[Culture]] is defined here as a set of distinctive material, [[intellect|intellectual]], [[emotion|emotional]], and [[spirit|spiritual]] features of a social group, including [[art]], [[literature]], [[lifestyle]]s, [[ethics|value systems]], [[tradition]]s, [[ritual]]s, and [[belief]]s. |

[[Culture]] is defined here as a set of distinctive material, [[intellect|intellectual]], [[emotion|emotional]], and [[spirit|spiritual]] features of a social group, including [[art]], [[literature]], [[lifestyle]]s, [[ethics|value systems]], [[tradition]]s, [[ritual]]s, and [[belief]]s. |

||

Culture consists of at least three elements: values, social norms, and [[Artifact (archaeology)| |

Culture consists of at least three elements: values, social norms, and [[Artifact (archaeology)|artifacts]]. A culture's values define what it holds to be important. Norms are expectations of how people ought to behave. Artifacts — things, or material culture — derive from the culture's values and norms together with its understanding of the way the world functions. |

||

===Origins=== |

===Origins=== |

||

{{ |

{{main articles|[[Origin belief]] and [[Creationism]]}} |

||

Essentially every culture has its characteristic [[origin beliefs]]. [[Creationism]] or |

Essentially every culture has its characteristic [[origin beliefs]]. [[Creationism]] or [[Creation (theology)|creation theology]] is the belief that humans, the [[Earth]], the [[universe]] and the [[multiverse]] were created by a [[supreme being]] or [[deity]]. The event itself may be seen either as an ''act of creation'' (''[[ex nihilo]]'') or the emergence of order from preexisting chaos ([[demiurge]]). Many who hold "creation" beliefs consider such belief to be a part of religious [[faith]], and hence compatible with, or otherwise unaffected by [[science|scientific]] views while others maintain the scientific data is compatible with creationism. Proponents of [[Theistic evolution|evolutionary creationism]] may claim that understood scientific mechanisms are simply ''aspects'' of supreme creation. Otherwise, science-oriented believers may consider the [[scripture|scriptural]] account of [[creation]] as simply a [[metaphor]]. |

||

===Emotion and sexuality=== |

|||

{{main articles|[[emotion]] and [[sexuality]]}} |

|||

[[Image:RodinKiss.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[Rodin]]'s "[[The Kiss (Rodin sculpture)|The Kiss]]"]] |

|||

Human [[emotion]] has a significant influence on, or can even be said to control, human behaviour. Emotional experiences perceived as pleasant, like [[love]], admiration, or [[joy]], contrast with those perceived as unpleasant, like [[hate]], [[envy]], or [[sorrow]]. There is often a distinction seen between refined emotions, which are socially learned, and survival oriented emotions, which are thought to be innate. |

|||

Human exploration of emotions as separate from other neurological phenomena is worth note, particularly in those cultures where emotion is considered separate from physiological state. In some cultural medical theories, to provide an example, emotion is considered so synonymous with certain forms of physical health that no difference is thought to exist. The Stoics believed excessive emotion was harmful, while some [[Sufi]] teachers (in particular, the poet and astronomer [[Omar Khayyám]]) felt certain extreme emotions could yield a conceptual perfection, what is often translated as [[ecstasy (emotion)|ecstasy]]. |

|||

In modern [[scientific]] thought, certain refined emotions are considered to be a complex neural trait of many domesticated and a few non-domesticated [[mammal]]s, developed commonly in reaction to superior survival mechanisms and intelligent interaction with each other and the environment; as such, refined emotion is not in all cases as discrete and separate from natural neural function as was once assumed. Still, when humans function in civilised tandem, it has been noted that uninhibited acting on extreme emotion can lead to social [[disorder]] and [[crime]]. |

|||

Human [[sexuality]], besides ensuring [[reproduction]], has important social functions, creating [[ physical intimacy]], bonds and hierarchies among individuals, and that may be directed to spiritual transcendence, and/or to the enjoyment of activity involving sexual gratification. [[Sexual desire]], [[libido]], is experienced as a bodily urge, often accompanied by strong emotions, both positive (such as [[love]] or [[ecstasy (emotion)|ecstasy]]) and negative (such as [[jealousy]]). |

|||

As with other human self-descriptions, humans propose it is high intelligence and complex societies of humans that have produced the most complex sexual behaviors of any animal. Human sexual choices are usually made in reference to cultural [[norms]], which vary widely. Restrictions are largely determined by religious beliefs. Most sexologist, starting with the pioneer Alfred Kinsey and Sigmund Freud, believe based upon the human species close relatives' sexual habits such as the bonobo apes, and historical records (particularly the widespread ancient practices of paederasty) that the majority of homo sapiens are attracted to males and females, being inherently bisexual. |

|||

===Language=== |

===Language=== |

||

{{ |

{{main articles|[[Language]] and [[Philosophy of language]]}} |

||

[[Image:Human langs.png|left|thumb|150px|From top-left, "human" in [[English language|English]], [[Japanese language|Japanese]], [[ |

[[Image:Human langs.png|left|thumb|150px|From top-left, "human" in [[English language|English]], [[Japanese language|Japanese]], [[Chinese language|Chinese]], [[Korean language|Korean]], [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] and [[Greek language|Greek]]]] |

||

Values, norms and technology are dependent on the capacity for humans to share ideas. The faculty of [[speech]] may be a defining feature of humanity, probably predating [[phylogenetic]] separation of the modern population. (See [[Proto-World language]], [[Origins of language]].) [[Language]] is central to the [[communication]] between humans. Some scientists argue that non-human animals are able to use some form of language too, and that non-human [[primate]]s are able to learn human [[sign language]] [http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/cultural/language/chimpanzee.html] [http://www.msubillings.edu/asc/PDF-WritingLab/3-Minute%20Spr05/APA%20sample%20paper.pdf] (pdf). Language is central to the sense of identity that unites [[culture]]s and [[ethnicity|ethnicities]]. |

Values, norms and technology are dependent on the capacity for humans to share ideas. The faculty of [[speech]] may be a defining feature of humanity, probably predating [[phylogenetic]] separation of the modern population. (See [[Proto-World language]], [[Origins of language]].) [[Language]] is central to the [[communication]] between humans. Some scientists argue that non-human animals are able to use some form of language too, and that non-human [[primate]]s are able to learn human [[sign language]] [http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/cultural/language/chimpanzee.html] [http://www.msubillings.edu/asc/PDF-WritingLab/3-Minute%20Spr05/APA%20sample%20paper.pdf] (pdf). Language is central to the sense of identity that unites [[culture]]s and [[ethnicity|ethnicities]]. |

||

The invention of [[writing systems]] some [[4th millennium BCE|5000 years ago]], allowing the preservation of speech, was a major step in cultural evolution. Language, especially written language, is sometimes thought to have supernatural status or powers. (See [[Magic]], [[Mantra]], [[Vac]].) |

The invention of [[writing systems]] some [[4th millennium BCE|5000 years ago]], allowing the preservation of speech, was a major step in cultural evolution. Language, especially written language, is sometimes thought to have supernatural status or powers. (See [[magic (paranormal)|Magic]], [[Mantra]], [[Vac]].) |

||

The science of [[linguistics]] describes the structure of language and the relationship between languages. There are estimated to be some 6,000 different languages, including sign languages, used today. |

The science of [[linguistics]] describes the structure of language and the relationship between languages. There are estimated to be some 6,000 different languages, including sign languages, used today. |

||

===Music=== |

===Music=== |

||

{{main|music}} |

|||

[[Music]] is a natural [[intuition|intuitive]] phenomenon operating in the three worlds of [[time]], [[pitch (music)|pitch]], [[energy]], and under the three distinct and interrelated |

[[Music]] is a natural [[intuition|intuitive]] phenomenon operating in the three worlds of [[time]], [[pitch (music)|pitch]], and [[energy]], and under the three distinct and interrelated organisation structures of [[rhythm]], [[harmony]], and [[melody]]. |

||

[[Composing]], [[improvising]] and performing music are all [[art]] forms. Listening to music is perhaps the most common form of [[entertainment]], while learning and understanding it are popular [[discipline]]s. There are a wide variety of [[ |

[[Composing]], [[improvising]] and performing music are all [[art]] forms. Listening to music is perhaps the most common form of [[entertainment]], while learning and understanding it are popular [[discipline]]s. There are a wide variety of [[music genre]]s and [[ethnic music]]s. |

||

=== |

===Government, politics and the state=== |

||

{{main articles|[[government]], [[politics]] and [[state]]}} |

|||

A [[state]] is an organized [[politics|political]] community occupying a definite [[territory]], having an organized [[government]], and possessing internal and external [[sovereignty]]. Recognition of the state's claim to independence by other states, enabling it to enter into international agreements, is often important to the establishment of its statehood. The "state" can also be defined in terms of domestic conditions, specifically, as conceptualized by [[Max Weber]], "a state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory." [http://www.mdx.ac.uk/www/study/xweb.htm] |

|||

Human [[emotion]] has a significant influence on, or can even be said to control, human behaviour. Emotional experiences perceived as pleasant, like [[love]], [[admiration]], or [[joy]], contrast with those perceived as unpleasant, like [[hate]], [[envy]], or [[sorrow]]. There is often a distinction seen between refined emotions, which are socially learned, and survival oriented emotions, which are thought to be innate. |

|||

[[Government]] can be defined as the [[politics|political]] means of creating and enforcing [[law]]s; typically via a [[bureaucracy|bureaucratic]] [[hierarchy]]. |

|||

Human exploration of emotions as separate from other neurological phenomena is worth note, particularly in those cultures were emotion is considered separate from physiological state. In some cultural medical theories, to provide an example, emotion is considered so synonymous with certain forms of physical health that no difference is thought to exist. The Stoics believed excessive emotion was harmful, while some [[Sufi]] teachers (in particular, the poet and astronomer [[Omar Khayyám]]) felt certain extreme emotions could yield a conceptual perfection, what is often translated as [[ecstasy]]. |

|||

[[Politics]] is the process by which decisions are made within groups. Although the term is generally applied to behavior within [[government]]s, politics is also observed in all human group interactions, including [[corporation|corporate]], [[academia|academic]], and [[religion|religious]] institutions. Many different political systems exist, as do many different ways of understanding them, and many definitions overlap. Common examples include [[monarchy]], [[social democracy]], [[military dictatorship]] and [[theocracy]]. |

|||

[[Image:RodinKiss.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[Rodin]]'s "[[The Kiss (Rodin sculpture)|The Kiss]]"]] In modern [[scientific]] thought, certain refined emotions are considered to be a complex neural trait of many domesticated and a few non-domesticated [[mammal]]s, developed commonly in reaction to superior survival mechanisms and intelligent interaction with each other and the environment; as such, refined emotion is not in all cases as discrete and separate from natural neural function as was once assumed. Still, when humans function in civilised tandem, it has been noted that uninhibited acting on extreme emotion can lead to social [[disorder]] and [[crime]]. |

|||

All of these issues have a direct relationship with [[economics]]. |

|||

Human [[sexuality]], besides ensuring [[reproduction]], has important social functions, creating [[ physical intimacy]], bonds and hierarchies among individuals, and that may be directed to spiritual transcendence, and/or to the enjoyment of any activity involving sexual gratification. [[Sexual desire]], [[libido]], is experienced as a bodily urge, often accompanied by strong emotions, both positive (such as [[love]] or [[ecstasy (state)|ecstasy]]) and negative (such as [[jealousy]]). |

|||

===Trade and economics=== |

|||

As with other human self-descriptions, humans propose it is high intelligence and complex societies of humans that have produced the most complex sexual behaviors of any animal. Human sexual choices are usually made in reference to cultural [[norms]], which vary widely. Restrictions against sexual relations outside a [[marriage]] bond and same-sex relations are amongst the most common. |

|||

{{main articles|[[trade]] and [[economics]]}} |

|||

[[Image:Market-Chichicastenango.jpg|thumb|375px|Buyers bargain for good prices while sellers put forth their best front in [[Chichicastenango]] Market, [[Guatemala]].]] |

|||

=== Body image === |

|||

[[Trade]] is the voluntary exchange of [[good (accounting)|goods]], [[service]]s, or both, and a form of [[economics]]. A mechanism that allows trade is called a [[market]]. The original form of trade was [[barter]], the direct exchange of goods and services. Modern traders instead generally negotiate through a medium of exchange, such as [[money]]. As a result, '''buying''' can be separated from '''selling''', or [[earning]]. The invention of money (and later credit, paper money and non-physical money) greatly simplified and promoted trade. |

|||

[[Image:Geisha-fullheight.jpg|thumb|left|140px|Women dressed as apprentice [[geisha]] in [[Kyoto]], [[Japan]]]]The [[Human physical appearance|physical appearance]] of the human body is central to [[culture]] and [[art]]. In every human culture, people adorn their bodies with [[tattoos]], [[cosmetics]], [[clothing]], and [[jewellery]]. [[Hairstyle]]s and hair colour also have important cultural implications. The perception of an individual as physically [[Beauty|beautiful]] or [[ugliness|ugly]] can have profound implications for their lives. This is particularly true of women, whose external [[appearance]] is highly valued in most, if not all, human societies. [[Anthropologist]]s believe this to be an important factor in the development of personality and [[social relations]] in particular [[physical attractiveness]]. |

|||

Trade exists for many reasons. Due to specialisation and [[division of labor]], most people concentrate on a small aspect of [[manufacturing]] or [[service]], trading their labour for products. Trade exists between regions because different regions have an absolute or [[comparative advantage]] in the production of some tradable commodity, or because different regions' size allows for the benefits of [[mass production]]. As such, trade between locations benefits both locations. |

|||

There is a relatively low [[sexual dimorphism]] between human males and females in comparison with other mammals. |

|||

Economics is a [[social science]] that studies the [[production]], [[distribution]], [[trade]] and [[consumption]] of goods and services. |

|||

===Trade and economics=== |

|||

Economics, which focuses on measurable variables, is broadly divided into two main branches: '''[[microeconomics]]''', which deals with individual agents, such as households and businesses, and '''[[macroeconomics]]''', which considers the economy as a whole, in which case it considers [[aggregate supply]] and [[aggregate demand|demand]] for [[money]], [[capital (economics)|capital]] and [[commodity|commodities]]. Aspects receiving particular attention in economics are [[resource allocation]], production, distribution, trade, and [[competition]]. Economic logic is increasingly applied to any problem that involves choice under scarcity or determining economic [[value#Economics|value]]. Mainstream economics focuses on how prices reflect [[supply and demand]], and uses equations to predict consequences of decisions. |

|||

[[Image:Market-Chichicastenango.jpg|thumb|375px|Buyers bargain for good prices while sellers put forth their best front in [[Chichicastenango]] Market, [[Guatemala]].]] |

|||

===War=== |

|||

[[Trade]] is the voluntary exchange of [[goods]], [[service]]s, or both, and a form of [[economics]]. A mechanism that allows trade is called a [[market]]. The original form of trade was [[barter]], the direct exchange of goods and services. Modern traders instead generally negotiate through a medium of exchange, such as [[money]]. As a result, '''buying''' can be separated from '''selling''', or [[earning]]. The invention of money (and later credit, paper money and non-physical money) greatly simplified and promoted trade. |

|||

{{main|War}} |

|||

[[Image:Nagasakibomb.jpg|250px|left|thumbnail|An act of war - the [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan]] on August 9, 1945, effectively ending [[World War II]]. The bombs over Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki immediately killed over 120,000 people.]] |

|||

War is a state of widespread [[conflict]] between [[state]]s, [[organisation]]s, or relatively large groups of people, which is characterised by the use of lethal [[violence]] between [[combatant]]s or upon [[civilian]]s. War is contrasted with [[peace]], which is usually defined as a state of existence free of conflict. |

|||

A common perception of war is a series of [[military campaign]]s between at least two opposing sides involving a dispute over [[sovereignty]], [[territory]], [[natural resource|resources]], [[religion]] or a host of other issues. A war said to [[liberation|liberate]] an [[military occupation|occupied]] country is sometimes characterised as a "[[War of Liberation|war of liberation]]", while a war between internal elements of a state may constitute a [[civil war]]. |

|||

Trade exists for many reasons. Due to specialization and [[division of labor]], most people concentrate on a small aspect of [[manufacturing]] or [[service]], trading their labour for products. Trade exists between regions because different regions have an absolute or [[comparative advantage]] in the production of some tradable commodity, or because different regions' size allows for the benefits of [[mass production]]. As such, trade between locations benefits both locations. |

|||

There have been a wide variety of [[Revolution in Military Affairs|rapidly advancing]] [[tactic]]s throughout the [[history of war]], ranging from [[conventional war]] to [[asymetric warfare]] to [[total war]] and [[unconventional warfare]]. Techniques have nearly always included [[hand to hand combat]], the usage of [[ranged weapons]], [[propaganda]], [[Shock and Awe]], and [[ethnic cleansing]]. [[Military intelligence]] has also always been key. In [[modern warfare]] [[armoured fighting vehicle]]s are used to control the land, [[warships]] the seas, and [[air power]] the skies. |

|||

Economics is a [[social science]] that studies the [[production]], [[distribution]], [[trade]] and [[consumption]] of [[goods]] and services. |

|||

Througout history there has been a constant strugle between [[defense]] and [[offense]], [[armour]] and the [[weapon]]s designed to breach it. Modern examples include the [[bunker buster bomb]], and the [[bunker]]s for which they are designed to destroy. |

|||

Economics, which focuses on measurable variables, is broadly divided into two main branches: '''[[microeconomics]]''', which deals with individual agents, such as households and businesses, and '''[[macroeconomics]]''', which considers the economy as a whole, in which case it considers [[aggregate supply]] and [[aggregate demand|demand]] for [[money]], [[capital (economics)|capital]] and [[commodity|commodities]]. Aspects receiving particular attention in economics are [[resource allocation]], production, distribution, trade, and [[competition]]. Economic logic is increasingly applied to any problem that involves choice under scarcity or determining economic [[value#Economics|value]]. Mainstream economics focuses on how prices reflect [[supply and demand]], and uses equations to predict consequences of decisions. |

|||

Many see war as destructive in nature, and a negative correlation has been shown between trade and war. |

|||

===Artefacts, technology, and science=== |

|||

===Artifacts, science, and technology=== |

|||

[[Image:Astronaut-EVA.jpg|thumb|right|300px|In the mid to late [[20th century]] humans achieved a level of technological mastery sufficient to leave the surface of the planet for the first time and [[space exploration|explore space]].]] |

|||

{{ |

{{main articles|[[Archaeology]], [[Technology]] and [[Science]]}} |

||

[[Image:Astronaut-EVA.jpg|thumb|right|300px|In the mid- to late 20th century humans achieved a level of technological mastery sufficient to leave the atmosphere of [[Earth]] for the first time and [[space exploration|explore space]].]] |

|||

Human cultures are both characterised and differentiated by the objects that they make and use. [[Archaeology]] attempts to tell the story of past or lost cultures in part by close examination of the [[Artifact (archaeology)|artefacts]] they produced. Early humans left [[stone tools]], [[pottery]] and [[jewellery]] that are particular to various regions and times. |

|||

Human cultures are both characterized and differentiated by the objects that they make and use. [[Archaeology]] attempts to tell the story of past or lost cultures in part by close examination of the [[Artifact (archaeology)|artifacts]] they produced. Early humans left [[stone tools]], [[pottery]] and [[jewellery]] that are particular to various regions and times. |

|||

Improvements in technology are passed from one culture to another. For instance, the [[agriculture|cultivation]] of crops arose in several different locations, but quickly spread to be an almost ubiquitous feature of human life. Similarly, advances in [[weapons]], [[architecture]] and [[metallurgy]] are quickly disseminated. |

Improvements in technology are passed from one culture to another. For instance, the [[agriculture|cultivation]] of crops arose in several different locations, but quickly spread to be an almost ubiquitous feature of human life. Similarly, advances in [[weapons]], [[architecture]] and [[metallurgy]] are quickly disseminated. |

||

Such techniques can be passed on by [[oral tradition]]. The development of [[writing]], itself a type of |

Such techniques can be passed on by [[oral tradition]]. The development of [[writing]], itself a type of artifact, made it possible to pass information from generation to generation and from region to region with greater accuracy. |

||

Together, these developments made possible the commencement of [[civilisation]] and [[urbanisation]], with their inherently complex social arrangements. Eventually this led to the institutionalisation of the development of new technology, and the associated understanding of the way the world functions. This [[ |

Together, these developments made possible the commencement of [[civilisation]] and [[urbanisation]], with their inherently complex social arrangements. Eventually this led to the institutionalisation of the development of new technology, and the associated understanding of the way the world functions. This [[science]] now forms a central part of human culture. |

||

In recent times, [[physics]] and [[astrophysics]] have come to play a central role in shaping what is now known as [[physical cosmology]], that is, the understanding of the universe through scientific observation and experiment. This discipline, which focuses on the universe as it exists on the largest scales and at the earliest times, begins by arguing for the [[big bang]], a sort of cosmic explosion from which the universe itself is said to have erupted ~13.7 ± 0.2 [[billion]] (10<sup>9</sup>) years ago. After its violent beginnings and until its very [[end of the universe|end]], scientists then propose that the entire history of the universe has been an orderly progression governed by [[physical laws]]. |

In recent times, [[physics]] and [[astrophysics]] have come to play a central role in shaping what is now known as [[physical cosmology]], that is, the understanding of the universe through scientific observation and experiment. This discipline, which focuses on the universe as it exists on the largest scales and at the earliest times, begins by arguing for the [[big bang]], a sort of cosmic explosion from which the universe itself is said to have erupted ~13.7 ± 0.2 [[billion]] (10<sup>9</sup>) years ago. After its violent beginnings and until its very [[end of the universe|end]], scientists then propose that the entire history of the universe has been an orderly progression governed by [[physical laws]]. |

||

== |

===Body image=== |

||

{{main|body image}} |

|||

{{Main2|Mind|Consciousness}} |

|||

[[Image:Senses_brain.png|right|thumb|200px|Human head with lines connecting the senses of taste, hearing, sight, and smell to areas of the brain. (d.1525)]] |

|||

[[Image:Geisha-fullheight.jpg|thumb|140px|Women dressed as apprentice [[geisha]] in [[Kyoto]], [[Japan]]]]The [[Human physical appearance|physical appearance]] of the human body is central to [[culture]] and [[art]]. In every human culture, people adorn their bodies with [[tattoos]], [[cosmetics]], [[clothing]], and [[jewellery]]. [[Hairstyle]]s and hair colour also have important cultural implications. The perception of an individual as physically [[Beauty|beautiful]] or [[ugliness|ugly]] can have profound implications for their lives. This is particularly true of women, whose external [[appearance]] is highly valued in most, if not all, human societies. [[Anthropologist]]s believe this to be an important factor in the development of personality and [[social relations]] in particular [[physical attractiveness]]. |

|||

There is a relatively low [[sexual dimorphism]] between human males and females in comparison with other mammals. |

|||

==Mind== |

|||

{{main articles|[[Mind]] and [[Consciousness]]}} |

|||

[[Image:Senses_brain.png|left|thumb|200px|Human head with lines connecting the senses of taste, hearing, sight, and smell to areas of the brain. (d.1525)]] |

|||

[[Consciousness]] is a state of [[mind]], said to possess qualities such as, [[self-awareness]], [[sentience]], [[sapience]], and the ability to [[perception|perceive]] the relationship between [[personal identity|oneself]] and one's [[natural environment|environment]]. |

[[Consciousness]] is a state of [[mind]], said to possess qualities such as, [[self-awareness]], [[sentience]], [[sapience]], and the ability to [[perception|perceive]] the relationship between [[personal identity|oneself]] and one's [[natural environment|environment]]. |

||