Bulgars: Difference between revisions

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

===Subsequent migrations=== |

===Subsequent migrations=== |

||

The legend tells that on his death-bed, Khan Kubrat had his sons gather sticks and bring them to him, which he then bundled together and told his eldest son [[Batbayan of Bulgaria|Bayan]] to break the bundle. Bayan failed under the strength of the combined sticks, and, after the rest of the sons failed this test as well, Kubrat took the sticks back, separated each one, and broke them all one-by-one even in his weakened state. Then he told his sons the words "Unity makes strength", which |

The legend tells that on his death-bed, Khan Kubrat had his sons gather sticks and bring them to him, which he then bundled together and told his eldest son [[Batbayan of Bulgaria|Bayan]] to break the bundle. Bayan failed under the strength of the combined sticks, and, after the rest of the sons failed this test as well, Kubrat took the sticks back, separated each one, and broke them all one-by-one even in his weakened state. Then he told his sons the words "Unity makes strength", which has become a very popular Bulgarian slogan and now appears on the modern [[Coat of arms of Bulgaria|Bulgarian coat of arms]]. |

||

The Byzantine Patriarch [[Nicephorus I]]<ref> [[Patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople]], ''Historia syntomos, breviarium''</ref> tells that Kubrat's sons, however, did not heed these very specific words, and thus soon after the death of Kubrat around [[665]], the Khazar expansion eventually led to the dissolution of [[Great Bulgaria]]. |

The Byzantine Patriarch [[Nicephorus I]]<ref> [[Patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople]], ''Historia syntomos, breviarium''</ref> tells that Kubrat's sons, however, did not heed these very specific words, and thus soon after the death of Kubrat around [[665]], the Khazar expansion eventually led to the dissolution of [[Great Bulgaria]]. |

||

Revision as of 15:10, 2 September 2008

The Bulgars (also Bolgars or proto-Bulgarians[1]) were a seminomadic people, probably of Turkic descent[2], originally from Central Asia, who from the 2nd century onwards dwelled in the steppes north of the Caucasus and around the banks of river Volga (then Itil). A branch of them gave rise to the First Bulgarian Empire.

Ethnicity and language

Racial type and descendants

Anthropological data collected from medieval Bulgar necropolises from Dobrudja, Crimea and the Ukrainian steppe shows that Bulgars were a high-statured Caucasoid people with a small Mongoloid admixture, and practiced artificial cranial deformation of the round type.[4][5][6][7][8][9]. From historical point of view the present-day Chuvash and Bulgarians are believed to originate partly from the Bulgars. According to their DNA data, the genetic backgrounds of both populations are clearly different. The Chuvash have a Central European and some Mediterranean genetic background (probably coming from the Caucasus), while the Bulgarians have a classical eastern Mediterranean (probably coming from the Balkans) composition. It is possible that only a cultural and low genetic Bulgar influence was brought into the two regions, without modifying the genetic background of the local populations.[10]

Оrigins

A leading theory about the origins of the Bulgars, is that they were Turkic speaking people from Central Asia, and their language was, alongside with Khazar, Turkic Avar, Hunnic and Chuvash, a member of the Oghuric branch of the Turkic language family.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28] It is supported, among other things, by the facts that some Bulgar words contained in the few surviving stone inscriptions,[29] and in other documents (mainly military and hierarchical terms such as tarkan, bagatur, and probably kan and kanartikin "prince") appear to be of Turkic origin, that the Bulgars apparently used a 12-year cyclic calendar similar to the one adopted by Turkic and Mongolian peoples from the Chinese, with names and numbers that are deciphered as Turkic, and that the Bulgars' supreme god was apparently called Tangra, a deity widely known among the Turkic peoples under names such as Tengri, Tura etc.[30] Some also point out the presence of a small number of Turkic loanwords in the Slavic Old Bulgarian language, and the fact that the Bulgars used an alphabet similar to the Turkic Orkhon script, although this alphabet hasn't been satisfactorily deciphered yet: fortunately, the Bulgar inscriptions were sometimes written in Greek or Cyrillic characters, most commonly in Greek, thus allowing the scholars to identify some of the Bulgar glosses. Supposedly, the name Bulgar is derived from the Turkic verb bulģa "to mix, shake, stir" and its derivative bulgak "revolt, disorder".[31]

Further evidence culturally linking the Danubian Bulgar state to Turkic steppe traditions was the layout of the Bulgars' new capital of Pliska, founded just north of the Balkan Mountains shortly after 681. The large area enclosed by ramparts, with the rulers' habitations and assorted utility structures concentrated in the center, resembled more a steppe winter encampment turned into a permanent settlement than it did a typical Roman Balkan city.[32]

Another alternative view is that Bulgar, far from being affiliated to Chuvash, belonged instead to the same branch as all other surviving Turkic languages and more specifically Kazan Tatar. Bulgarian scholar Ivan Shishmanov speculated in 1900 that this was the case,[33] and the same view is espoused also by modern Bulgarist Kazan Tatar linguist Mirfatyh Zakiev.[34]

Cäğfär Taríxı, a Russian language document of disputed authenticity, purports to be a 1680 compilation of ancient Bulgar annals. It was published by a Volga Tatar Bulgarist editor in 1993. Cäğfär Taríxı contains a very detailed description of Bulgar history. Among other things, it implies that the Bulgars were formed as a result of consolidation of many Turkic and Turkicized tribes.

Additional theories

A newer Aryan theory, claims that the Bulgar language was originally an Iranian language, and so according to this theory, the Bulgar people would be classified as an Aryan people, although some of its proponents concede that the language was later influenced by Turkic due to Hunnic military domination. This notion became popular in Bulgaria in the 1990s, with the works of Petar Dobrev, a specialist in economic history.[35] Supporters of this theory are some Bulgarian historians such as professor Georgi Bakalov[36] and professor Bozhidar Dimitrov.[37] The theory is supported mostly by linguistic arguments, as authors (who are usually not linguists[38]) attempt to prove the Iranian origin of a number of words and sometimes even grammatical features in Bulgar and modern Bulgarian.[39]

In the 19th century, even theories of a Slavic or Finno-Ugric affiliation were proposed on the basis of the little or no evidence.[33] These have practically no adherents among today's scholars.

Contemporaneous sources like Procopius, Agathias and Menander called the Kutrigur and Utigur Bulgars "Huns"[40] while others, like the Byzantine Patriarch Michael II of Antioch, called them "Scythians" or "Sarmatians". But this latter identification is clearly due to the Byzantine tradition of naming peoples geographically; for example, centuries later the obviously Turkic Petchenegs and Cumans, were still addressed with the respective terms.

Culture and society

Archaeological finds from the Ukrainian steppe suggest that the early Bulgars had the typical culture of the nomadic equestrians of Central Asia. They were primarily nomadic herdsmen who migrated seasonally in pursuit of pastures but also planted crops such as wheat and barley. The Bulgars were skilled blacksmiths, stone masons and carpenters. From the 7th century onwards they rapidly began to settle down.

Social structure

The Bulgars had a well-developed clan system and were governed by hereditary rulers. The members of the military aristocracy bore the title boil (boyar) which could be either inherited or acquired[citation needed]. There also were bagains - lesser military commanders. The nobility were further divided onto Small and Great Boyars. The latter formed the Council of the Great Boyars and gathered to take decisions on important state matters presided by the khan (king). Their numbers varied between six and twelve. These probably included the ichirgu boil and the kavkhan (vice khan), the two most powerful people after the khan. These titles were administrative and non-inheritable. The boyars could also be internal and external, probably distinguished by their place of residence - inside or outside the capital [41]. The heir of the throne was called kanartikin. Other non-kingly titles used by the Bulgarian noble class include boila tarkan (possibly the second son of the khan), kana boila kolobur (chief priest), boritarkan (city mayor).

The title khan for early Bulgar ruler is an assumed one as only the form kanasubigi is attested in stone inscriptions. Historians presume that it includes the word khan in its archaic form kana and there is a supporting evidence suggesting that the latter title was indeed used in Bulgaria, e.g. the name of one of the Bulgarian rulers Pagan occurs in Patriarch Nicephorus's so-called Breviarium as Καμπαγάνος (Kampaganos), likely an erroneous rendition of the phrase "Kan Pagan".[42] Among the proposed translations for the phrase kanasubigi as a whole are lord of the army, from the reconstructed Turkic phrase *sü begi, paralleling the attested Old Turkic sü baši,[43] and, more recently, (ruler) from God, from the Indo-European *su- and baga-, i.e. *su-baga (a counterpart of the Greek phrase ὁ ἐκ Θεοῦ ἄρχων, ho ek Theou archon, which is common in Bulgar inscriptions).[44] This titulature presumably persisted until the Bulgars adopted Christianity.[45] Some Bulgar inscriptions written in Greek and later in Slavonic refer to the Bulgarian ruler respectively with the Greek title archon or the Slavic title knyaz.[46].

Religion

The religion of the Bulgars is also obscure but it is supposed that it was monotheistic, worshiping the Turkic Sky god Tengri. However, the archaeological evidence shows that the Bulgar sanctuaries resembled the layout of the Zoroastrian temples of the fire. Therefore, the religion may have comprised elements of both, Turkic and Iranian cults[47]. In Pliska, the first capital of Danube Bulgaria, there is a building of this type - two entered one into another squares of ashlars.A second, much larger building, oriented towards the sunrise, was excavated near the Throne palace in Pliska. Its religious utilization is confirmed by the fact that after the adoption of Christianity the building was transformed into a Christian church (the so called Palace church). Similar buildings are also found in Preslav. Similar in plan is the pagan sanctuary at the Proto-Bulgarian religious complex of Madara, near the location Daul Tash.

History

Migration to Europe

In the early 2nd century, some groups of Bulgars migrated from Central Asia to the European continent and settled on the plains between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea. The Bulgars appear (under the ethnonym of ‘Bulensii’) in certain Latin versions of Ptolemy’s second century AD mapping, shown as occupying the territory along the northwest coast of Black Sea east of Axiacus River (Southern Bug).[48][49][50]

Between 351 and 389, some of the Bulgars crossed the Caucasus to settle in Armenia. Toponymic data testify to the fact that they remained there and were eventually assimilated by the Armenians.

Swept by the Hunnish wave at the beginning of the 4th century, other Bulgar tribes broke loose from their settlements in Central Asia to migrate to the fertile lands along the lower valleys of the Donets and the Don rivers and the Azov seashore, assimilating what was left of the Sarmatians. Some of these remained for centuries in their new settlements, whereas others moved on with the Huns towards Central Europe, settling in Pannonia.

Those Bulgars took part in the Hun raids on Central and Western Europe between 377 and 453. After the death of Attila in 453, and the subsequent disintegration of the Hunnish empire, the Bulgar tribes dispersed mostly to the eastern and southeastern parts of Europe.

At the end of the 5th century (probably in the years 480, 486, and 488) they fought against the Ostrogoths as allies of the Byzantine emperor Zeno. From 493 they carried out frequent attacks on the western territories of the Byzantine Empire. Later raids were carried out at the end of the 5th century and the beginning of the 6th century.

In the middle of the 6th century, war broke out between the two main Bulgar tribes, the Kutrigur and Utigur. At the end of the 6th century, the Kutrigur allied with the Avars to conquer the Utigur. The Bulgars fell under the domination of the Göktürk Khanate in 568.

Establishment of Great Bulgaria

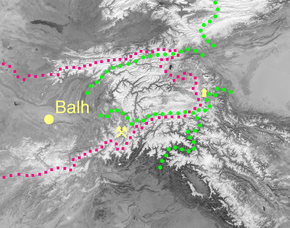

United under Kubrat or Kurt of the Dulo clan (supposedly [who?] identical to the ruler mentioned by Arabic chronicler At-Tabari under the name of Shahriar), they joined forces of the Utigur and Kutrigur Bulgars and probably the non-Bulgar Onogurs, and broke loose from the Turkic khanate in the 630s. They formed an independent state, the Onogundur-Bulgar (Oghondor-blkar or Olhontor-blkar) Empire, often called by Byzantine sources[51] ‘the Old Great Bulgaria’. The empire was situated between the lower course of the Danube to the west, the Black Sea and the Azov Sea to the south, the Kuban River to the east, and the Donets River to the north. It is assumed that the state capital was Phanagoria, an ancient city on the Taman peninsula (see Tmutarakan). However, the archaeological evidence shows that the city became predominantly Bulgarian only after Kubrat's death and the consequent disintegration of his state.

Subsequent migrations

The legend tells that on his death-bed, Khan Kubrat had his sons gather sticks and bring them to him, which he then bundled together and told his eldest son Bayan to break the bundle. Bayan failed under the strength of the combined sticks, and, after the rest of the sons failed this test as well, Kubrat took the sticks back, separated each one, and broke them all one-by-one even in his weakened state. Then he told his sons the words "Unity makes strength", which has become a very popular Bulgarian slogan and now appears on the modern Bulgarian coat of arms.

The Byzantine Patriarch Nicephorus I[52] tells that Kubrat's sons, however, did not heed these very specific words, and thus soon after the death of Kubrat around 665, the Khazar expansion eventually led to the dissolution of Great Bulgaria.

The khan’s eldest son, Batbayan (also Bayan or Boyan), remained the ruler of the land north of the Black and the Azov Seas, which was, however, soon subdued by the Khazars. Those Bulgars converted to Judaism in the 9th century, along with the Khazars, and were eventually assimilated. A different theory claims that the Balkars in Kabardino-Balkaria may be the descendants of this Bulgar branch.

Another Bulgar tribe, led by Kubrat’s second son Kotrag, migrated to the confluence of the Volga and Kama Rivers in what is now Russia (see Volga Bulgaria). The present-day republics of Tatarstan and Chuvashia are considered to be the descendants of Volga Bulgaria in terms of territory and people, but only Chuvash is thought to be similar to the old Bulgar language.

A third Bulgar tribe, led by the youngest son Asparukh, moved westward, occupying today’s southern Bessarabia. After a successful war with Byzantium in 680, Asparukh's khanate setteled in Dobrudja and conquered later Moesia Superior So it was recognized as an independent state under the subsequent treaty signed with the Byzantine Empire and emperor Constantine IV Pogonatus in 681. The same year is usually regarded as the year of the establishment of modern Bulgaria (see History of Bulgaria).

A fourth group of Bulgars, ruled by Kuber, existed in Pannonia. After breaking off Avar overlordship, they moved on to Macedonia.[53] Bulgarian scholar Vasil Zlatarski posits that Kuber was also a son of Kubrat. He believes that Kuber's Bulgars formed a khanate in Macedonia, which joined Slavs to attack the Byzantine Empire, although the majority of historians do not see any evidence for the existence of a Bulgar khanate in Macedonia before 850 AD. In addition this group from around 70, 000 people,[54] included also descendents of Roman captives of various ethnicities that had been re-settled in Pannonia by the Avars.[55][56].

The fifth and smallest group, of Alcek (also transliterated as 'Altsek' and 'Altzek'), after many wanderings, ended up led by Emnetzur and settled in Italy, northeast of Naples.

List of Bulgar tribes

Tribes thought to have been Bulgar in origin include:

After the dissolution of Great Bulgaria these tribes formed:

- Asparukh’s Horde

- Batbayan's Horde

- Kotrag's Horde

- Kuber’s Horde

- Alcek’s Horde

See also

- Bulgar language

- Bulgarians

- Pamir languages

- Madara Rider

- Chuvash

- Volga Bulgaria

- Bactrians

- Balkar

- Bolghar

- Yuezhi

- Kuber

- Mount Imeon

- Kingdom of Balhara

- Old Great Bulgaria

References

- ^ The term proto-Bulgarians was introduced after WWII.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online - Bulgars

- ^ ЗЛАТНОТО СЪКРОВИЩЕ НА БЪЛГАРСКИТЕ KАНОВЕ - анотация на проф. Иван Добрев. Военна Академия "Г. С. Раковски", София.

- ^ D.Dimitrov,1987, History of the Proto-Bulgarians north and west of the Black Sea.

- ^ Сарматски елементи в езическите некрополи от Североизточна България и Северна Добруджа. Елена Ангелова (сп. Археология, 1995, 2, 5-17, София)

- ^ М. Б а л а н, П. Б о е в. Антропологични материали от некропола при Нови пазар. — ИАИ, XX, 1955, 347— 371

- ^ Й. Ал. Й о р д а н о в. Антропологично изследване на костния материал от раннобългарски масов гроб при гр. Девня. - ИНМВ, XII (XVII), 1976, 171-194

- ^ Н. К о н д о в а, П. Б о е в, С л. Ч о л а к о в. Изкуствено деформирани черепи от некропола при с. Кюлевча, Шуменски окръг. — Интердисциплинарни изследвания, 1979, 3—4, 129— 138;

- ^ Н. К о н д о в а, С л. Чолаков. Антропологични данни за етногенеза на ранносредновековната популация от Североизточна България. — Българска етнография, 1992, 2, 61-68

- ^ HLA genes in the Chuvashian population from European Russia: Admixture of central European and Mediterranean populations - pg. 5

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia: Eastern Bulgars

- ^ Образуване на българската държава. проф. Петър Петров (Издателство Наука и изкуство, София, 1981)

- ^ Образуване на българската народност.проф. Димитър Ангелов (Издателство Наука и изкуство, “Векове”, София, 1971)

- ^ A history of the First Bulgarian Empire.Prof. Steven Runciman (G. Bell & Sons, London 1930)

- ^ История на българската държава през средните векове Васил Н. Златарски (I изд. София 1918; II изд., Наука и изкуство, София 1970, под ред. на проф. Петър Хр. Петров)

- ^ История на българите с поправки и добавки от самия автор акад. Константин Иречек (Издателство Наука и изкуство, 1978) проф. Петър Хр. Петров

- ^ Heinz Siegert: Osteuropa – Vom Ursprung bis Moskaus Aufstieg, Panorama der Weltgeschichte, Bd. II, hg. von Dr. Heinrich Pleticha, Gütersloh 1985, p. 46

- ^ P. B. Golden An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. - Wisbaden, 1992. - p.92-104

- ^ [René Grousset: Die Steppenvölker, München 1970, p. 249]

- ^ Harald Haarmann: Protobulgaren in: Lexikon der untergegangenen Völker, München 2005, p.225

- ^ Rashev, Rasho. 1992. On the origin of the Proto-Bulgarians. p. 23-33 in: Studia protobulgarica et mediaevalia europensia. In honour of Prof. V. Beshevliev, Veliko Tarnovo

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online - Bolgar Turkic

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online - Bulgars

- ^ Sedlar, Jean W. East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press, 1994. page 6

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online - Bulgar

- ^ Bowersock, G. W. & Grabar, Oleg. Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press, 1998. page 354

- ^ Chadwick, Henry. East and West: The Making of a Rift in the Church : from Apostolic Times. Oxford University Press, 2003. page 109

- ^ Reuter, Timothy. The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge University Press, 2000. page 492

- ^ Beshevliev, Vesselin. Proto-Bulgarian Epigraphic Monuments. Sofia, 1981. web page

- ^ Sedlar, Jean W. East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press, 1994. page 141

- ^ Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. Les Nomades : Les peuples nomades de la steppe des origines aux invasions mongoles. Paris: Errance, 2003: p.178.

- ^ Dennis P. Hupchick, The Balkans, 2001, pp.10, ISBN 0-312-21736-6

- ^ a b Шишманов, Иван. 1900. Критичен преглед на въпроса за произхода на прабългарите от езиково гледище и етимологиите на името българин

- ^ Закиев, Мирфатых. 2003. Происхождение тюрков и татар. 2003. in English

- ^ Добрев, Петър, 1995. "Езикът на Аспаруховите и Куберовите българи" 1995

- ^ Бакалов, Георги. Малко известни факти от историята на древните българи Част 1част 2

- ^ Димитров, Божидар, 2005. 12 мита в българската история

- ^ IST World Community Portal - Peter Dobrev

- ^ Peter Dobrev, The language of the Asparukh and Kuber Bulgars, Vocabulary and grammar

- ^ The World of the Huns. Chapter IX. Language, by O. Maenchen-Helfen

- ^ [http://www.promacedonia.org/vb/vb_7.html Прабългарски епиграфски паметници В. Бешевлиев]

- ^ Източници за българската история - Fontes historiae bulgaricae. VI. Fontes graeci historiae Bulgaricae. БАН, София. p.305 (in Byzantine Greek and Bulgarian). Also available online

- ^ V. Beshevliev - Prabylgarski epigrafski pametnici - 5

- ^ Blackwell Synergy - Early Medieval Eur, Volume 10 Issue 1 Page 1-19, March 2001 (Article Abstract)

- ^ Sedlar, Jean W. "East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500", page 46

- ^ Manassias Chronicle, Vatican transcription, p. 145, see Battle of Pliska

- ^ The Proto-Bulgarians east of the Sea of Azov in the 8-9th c.

- ^ Dobrev, Petar. Unknown Ancient Bulgaria. Sofia: Ivan Vazov Publishers, 2001. 158 pp. (in Bulgarian) ISBN 9546041211

- ^ Fries, Lorenz and Claudius Ptolemy. Tabula IX. Europae. In: Servetus, Michael. Opus Geographiae. Lyon, 1535.

- ^ Germanus, Nikolaus and Claudius Ptolemy. Geographia. Ulm: Lienhart Holle, 1482. (fragment)

- ^ Patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople, "Historia syntomos, breviarium"

- ^ Patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople, Historia syntomos, breviarium

- ^ Васил Н. Златарски - История на Първото българско Царство.(I изд. София 1918; II изд., Наука и изкуство, София 1970, под ред. на Петър Хр. Петров) стр. 514.

- ^ Средновековни градови и тврдини во Македониjа,(Скопjе, Македонска цивилизациjа, 1996) Иван Микулчик, стр. 71.

- ^ The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. D P Hupchik

- ^ Southeastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages. Florin Curta

External links

- History of Bulgaria

- History of the Bulgars

- Bulgars on Regnal Chronologies

- The language of the Asparukh and Kuber Bulgars, Vocabulary and grammar, by Peter Dobrev

- Inscriptions and Alphabet of the Proto-Bulgarians, by Peter Dobrev

- On the origins of the Proto-Bulgarians

- Proto-Bulgarian Epigraphic Monuments, Vesselin Beshevliev

- Conceptions of Ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies, by Walter Pohl

- History of the Proto-Bulgarians north and west of the Black Sea

- Encyclopaedia Britannica Online - Arrival of the Bulgars