Pallava dynasty: Difference between revisions

Edits. Undid some misquoting by Lifebonzza. |

Lifebonzza (talk | contribs) Undid revision 504266958, vandalism |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{redirect|Pallava|the Pallava script|Grantha alphabet}} |

{{redirect|Pallava|the Pallava script|Grantha alphabet}} |

||

{{Infobox Former Country |

{{Infobox Former Country |

||

|native_name = பல்லவர் |

|||

|conventional_long_name = Pallava dynasty |

|conventional_long_name = Pallava dynasty |

||

|common_name = Pallava |

|common_name = Pallava or Tondaiyar |

||

|continent = Asia |

|continent = Asia |

||

|region = South-East Asia |

|region = South-East Asia |

||

| Line 40: | Line 41: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

{{HistoryOfSouthAsia}} |

{{HistoryOfSouthAsia}} |

||

''' |

'''Pallava dynasty''' ([[Tamil language|Tamil]]: பல்லவர்), also the '''Tondaiyar dynasty of [[Tondai Nadu]]''', was a ruling dynasty of [[South India]] from the second to the ninth century CE. Establishing themselves as a rising Tamil power in the region with the metropolis [[Kanchipuram]] of [[Tamil Nadu]] as their capital, the Pallavas emerged after the [[Three Crowned Kings]] to become one of the major states of the post-[[Sangam period]] before the rise of the medieval [[Chola Dynasty|Chola]] empire.<ref>Ancient India, A History Textbook for Class XI, Ram Sharan Sharma, National Council of Educational Research and Training, India pp 209</ref> [[Origin of Pallava|Four family dynastic lines]] of the Pallavas have been traced to at least the second century of the common era. An ancient [[Early Cholas|Chola]]-[[Naga people (Sri Lanka)|Nāka]] alliance at [[Nainativu]] and succeeding Pallava-Naka liaisons marked the dynasty's formative years.<ref name="Gangoly">{{cite book|author=Ordhendra Coomar Gangoly|title=The art of the Pallavas, Volume 2 of Indian Sculpture Series|page=2|publisher=G. Wittenborn, 1957}}</ref> Centering their authority in Tondai Nadu, one ''Thiraiyar'' Pallava lineage gained prominence around Kanchi after the reign of [[Karikala Chola]] and the eclipse of the [[Satavahanas|Satavahana dynasty]] of [[Andhra Pradesh]] in 220.<ref>The journal of the Numismatic Society of India, Volume 51, p.109</ref><ref>Alī Jāvīd and Tabassum Javeed. (2008). World heritage monuments and related edifices in India, p.107 [http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=54XBlIF9LFgC&pg=PA107&dq=pallava+feudatory+satavahana&hl=en&ei=GdG3TvPDEITtrQfDuNjDAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAQ#v=snippet&q=feudatories&f=false]</ref> |

||

From gaining power, the dynasty sought to expand their country passed the northern frontiers of Aruva Nadu in Tamilakkam. Under Skandavarman I, the Pallavas extended their dominions north to the [[Krishna River]] and west to the [[Arabian Sea]], while King Vishnugopa attacked and weakened the early Chola state around Kanchi before facing defeat in 365. Emperor [[Simhavishnu]] joined [[Pandyan dynasty|Pandyan]] [[Kadungon]] in ending the [[Kalabhras dynasty|Kalabhra Interregnum]] by 550, reestablishing Pallava maritime power and consolidating Tamil rule across Asia. [[Narasimhavarman I]] oversaw Pallava supremacy in peninsular India before their dominions eventually passed to the Chola kings in 880. The dynasty's descendants established the [[Kadava|Kadava kingdom]] in the thirteenth century. |

|||

Kanchipuram, the Pallava imperial capital, developed into a city of temples to many faiths under their rule. Literary, painting and music activity spread, the [[Bhakti movement]] of the [[Vaishnava]] [[Alvars]] and the [[Saiva]] [[Nayanars]] flourishing under Pallava royal patronage alongside [[Tamil Jain|Tamil Jainism]], [[Tamil Buddhism|Buddhism]] and [[Native Dravidian religion]]. Largely Brahmanical Hindus, they constructed the [[Kailasanathar Temple|Kailasanathar stone temples and sculptures]], the [[Ekambareswarar Temple]] and [[Kamakshi Amman Temple]] in Kanchi. Becoming a major military, economic and cultural power in Asia, the dynasty extended their artistic prowess to the temples of [[Koneswaram temple|Koneswaram]], [[Ketheeswaram temple|Ketheeswaram]], [[Nalanda Gedige]], [[Thiriyai]] and [[Tenavaram temple|Tenavarai]]. Founding the school of [[Zen Buddhism]], Pallava prince [[Bodhidarma]] transmitted his knowledge of the religion and [[martial arts]] techniques of [[Silambam]] to [[Silat]] and [[Kung-Fu]] at the [[Shaolin Monastery]] in the 5th century, attracting Chinese Buddhist pilgrims including [[Xuanzang]] to Kanchipuram in 642 to find a city of 80 Hindu shrines, 100 monasteries and 10000 monks under Narasimhavarman I. As trade with China increased, [[Narasimhavarman II|Rajasimha]] built the "Chinese Pagoda" of [[Nagapattinam]] to please their diplomats, merchants and monks at the Pallava court. |

|||

The Pallavas joined the Chola Dynasty in settling and asserting commercial influence in Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia by the fourth century. Pallava royal lineages were established in the [[Early history of Kedah|old kingdom of Kedah]] of the Malay Peninsula under Rudravarman I, [[Chenla]] under [[Bhavavarman I]], [[History of Champa|Champa]] under [[Fan Hu Ta|Bhadravarman I]] and the Kaundinya-Gunavarman line of the [[Kingdom of Funan|Funan]] in Cambodia, eventually their rule growing to form the [[Khmer Empire]]. These dynasties' unique [[Dravidian architecture|Dravidian architectural]] style was introduced to build [[Angor Wat]] while Tamil cultural norms spread across the continent, their surviving epigraphic inscriptions recording domestic societal life and their pivotal role in Asian trade routes.<ref name=International2000>{{cite book | last = International Tamil Language Foundation| first = |title = The Handbook of Tamil Culture and Heritage| year = 2000| publisher = International Tamil Language Foundation| location = Chicago| page = 877}}</ref><ref name=Sastri1949>{{cite book | last = Sastri| first = K.A. Nilakanta|title = South Indian Influences in the Far East| year = 1949| publisher = Hind Kitab Ltd.| location = Bombay| pages = 28 & 48}}</ref> Direct extensive contacts with these regions were maintained from the maritime commerce city [[Mamallapuram]], where [[Mahendravarman I]] and his son "Mahamalla" [[Narasimhavarman I]] built the [[Shore Temple]] of the [[Seven Pagodas of Mahabalipuram]]. In the far east, the Pallavas established the [[South Indian]] doctrines of [[Saivism]], [[Vaishnavism]] and state languages written in [[Grantha alphabet|Pallava Grantha]] and [[Vatteluttu alphabet]] characters; these Tamil scripts would give rise to multiple writing systems in Asia over the next millennium, one of the Pallava's most enduring legacies. |

|||

==Origins== |

==Origins== |

||

{{Expand section|date=July 2012}} |

|||

{{TNhistory}} |

|||

{{main article|Origin of Pallava}} |

|||

{{APhistory}} |

|||

The antiquity of this dynasty is evident from the mentions in [[Sangam literature|ancient Tamil literature]] and in inscriptions. Later Pallavas also claimed in multilingual inscriptions and folklore traditions a long and ancient lineage to their dynasty. Mentions in the early [[Sangam Literature|Sangam literature]] (c. 150 CE)<ref name="sangam">The age of Sangam is established through the correlation between the evidence on foreign trade found in the poems and the writings by ancient Greek and Romans such as ''Periplus''. [[K.A. Nilakanta Sastri]], ''A History of South India'', p 106</ref> indicate that the earliest kings of the dynasty antedated 250. Early Pallava script charters in Prakrit dated on paleographic grounds to 250-350 reveal that a dynasty named ''Pallava'' was active in the Tondai-Aruva region of [[Tamil Nadu]] in the latter stages of floruit of the Sangam period's [[Three Crowned Kings]]. One prominent dynastic line of this clan consolidated power at the city of [[Kanchipuram]] following the eclipse of the [[Satavahanas|Satavahana dynasty]] of [[Andhra Pradesh]] in 220, whom the Pallavas had served as subordinates, while related family lines located around the country grew. |

|||

Main article: [[Origin of Pallava]] |

|||

An ancient [[Early Cholas|Chola]]-[[Naga people (Sri Lanka)|Nāka]] alliance at [[Nainativu]] and succeeding Pallava-Naka liaisons marked the dynasty's formative years. [[Sattanar|Seethalai Saathanar]], author of the Tamil classic ''[[Manimekalai]]'' notes a union between Princess Pilli Valai of [[Nāka Nadu]] with King Killi of [[Chola Nadu]] at [[Nainativu]] - an islet he names ''Manipallavam''; here was born Prince Tondai [[Ilandiraiyan]] (of the Thiraiyar/sea farer of [[Eelam]] lineage). Ilandiraiyan, a young contemporary of Karikala Chola became an independent ruler of ''Tondaimandalam'' around 200, stretching his Tondaiyar-Thiraiyar domain passed the [[Tirumala Venkateswara Temple]], [[Tirupati (city)|Tirupati]] whose construction he consecrated.<ref name="Gangoly">{{cite book|author=Ordhendra Coomar Gangoly|title=The art of the Pallavas, Volume 2 of Indian Sculpture Series|page=2|publisher=G. Wittenborn, 1957}}</ref> The earlier written poem ''[[Akananuru]]'' locates two Thiraiyar kings; an elder Tiriyan in Gudur, Nellore district, with a kingdom extending to Thiruvengadam, Tirupati,<ref name="SKR 72">KR Subramanian. (1989). Buddhist remains in Āndhra and the history of Āndhra between 224 & 610 A.D, p.72</ref> distinguished from the younger Tiraiyan (Ilandiraiyan) whose capital was Kanchipuram.<ref name="SKR 72"/><ref>[[Perumbanarrupadai|Perumpāṇāṟṟuppaṭai]] 29-30, 454</ref> The Sangam work ''[[Perumpāṇāṟṟuppaṭai|Perumbanarruppatai]]'' traces the line of Ilandiraiyan to the Solar dynasty of [[Andhra Ikshvaku]], who ruled in the late second century, while later Tamil commentators identify him with the Chola-Naka alliance.<ref name="SKR 72"/> Ilandiraiyan was a patron and poet during the Sangam period, obtaining the respect of the Three Crowned Kings. Some traditions describe him as Karikala's grandson and viceroy at Kanchi. Centering their authority in Tondai Nadu, Ilandiraiyan's descendants gained prominence as one Pallava line ruling Kanchi from 220.<ref>The journal of the Numismatic Society of India, Volume 51, p.109</ref><ref>Alī Jāvīd and Tabassum Javeed. (2008). World heritage monuments and related edifices in India, p.107 [http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=54XBlIF9LFgC&pg=PA107&dq=pallava+feudatory+satavahana&hl=en&ei=GdG3TvPDEITtrQfDuNjDAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAQ#v=snippet&q=feudatories&f=false]</ref><ref>Vakataka - Gupta Age Circa 200-550 A.D. |

|||

The [[Three Crowned Kings]] (Tamil: மூவேந்தர், Mūvēntar), refers to the triumvirate of Chola, Chera and Pandya who dominated the politics of the ancient Tamil country, Tamilakam made up of the regions of Chola Nadu, Chera Nadu and Pandya Nadu. The Pallavas found no mention as rulers in Tamil regions during this time. The earliest Tamil literature which throws light on a region associated with the Pallavas is [[Ahananuru]] which locates two Tiriyans -- the elder Tiriyan in Gudur, Nellore district, with a kingdom extending to Tirupati or Thiruvengadam; and the younger Tiraiyan whose capital was Kanchipuram.<ref name="SKR 72">KR Subramanian. (1989). Buddhist remains in Āndhra and the history of Āndhra between 224 & 610 A.D, p.72</ref> The Sangam work, [[Perumpāṇāṟṟuppaṭai|Perumbanarruppatai]], traces the line of the younger Tiriyan (aka Ilam Tiriyan) to the Solar dynasty of Ikshvakus, while the later Tamil commentators identify him as the illegitimate child of a Chola king and a Naga princess.<ref name="SKR 72"/> |

|||

By R. C. Majumdar, A. S. Altekar. pp. 222-223</ref> |

|||

[[Nandivarman III]]'s Velurpalaiyam plates of 852 credit the Chola-Naka liaison episode and creation of the Pallava line to a king named Virakurcha, son of Chutapallava.<ref name="RMD 189-241">Michael D Rabe. (1997). The Māmallapuram Praśasti: A Panegyric in Figures, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 57, No. 3/4 (1997), pp. 189-241.</ref> A stanza reads "from [[Ashwatthama|Aśvatthāman]] in order (came) Pallava, the lord of the whole earth, whose fame was bewildering. Thence, came into existence the race of Pallavas... [including the son of Chūtapallava] Vīrakūrcha, of celebrated name, who simultaneously with (the hand of) the daughter of the chief of serpents grasped also the complete insignia of royalty and became famous..." Historically, early relations between the Nagas and Pallavas became well established.<ref name="SKR 71"/> A ''praśasti'' (literally "praise"), composed in 753 on the dynastic eulogy in the Kasakadi plates by [[Nandivarman II]] traces the Pallava lineage from creation through a series of mythic progenitors, then praises the dynasty in terms of two similes hinged together by triple use of the word avatara ("descent"), as follows<ref name="RMD 189-241"/> - "From [them] descended the powerful, spotless Pallava dynasty [vaṁśāvatāra], which resembled a partial incarnation [aṃśāvatāra] of Visnu, as it displayed unbroken courage in conquering the circle of the world...and which resembled the descent of the Ganges [gaṅgāvatāra] as it purified the whole world." |

|||

PT Srinivasa Iyengar states 'Tondaiyar' means the "''tribe whose symbol was the Tondai creeper''".<ref name="PTSI"/> Tondai or ''Coccinia indica'' is commonly known as ''Kōvai'' in Tamil in modern times, but the name Doṇḍe is the ordinary name for the plant in Telugu.<ref name="PTSI">{{cite book|author=P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar|title=History of the Tamils: from the earliest times to 600 A.D.|page=401|publisher=Asian Educational Services|year=1929|ISBN=81-206-0145-9, 9788120601451|url=http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=ERq-OCn2cloC&pg=PA401&dq=pallava+tondai&hl=en&sa=X&ei=oQ8VT7vtDs-xrAeF67GSAg&ved=0CEoQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=pallava%20tondai&f=false}}</ref> Synonyms of Doṇḍe, Tonde or Tondai (Coccinia indica) are Cephalandra indica and [[Coccinia grandis]]. |

|||

[[Khmer]] folklore and inscriptions relate the [[Kingdom of Funan|Funan dynasty]]’s origins with that of the Pallavas. Around 180, the Kaundinya-Gunavarman line of the Khmer civilization was founded following the consummation of a relationship between Prince Kaundinya – a Brahman and worshipper of Ashwatthama - with Queen Somadevi of the Naga tribe. Kang Tai, a Chinese envoy of the third century reports that when Kaundinya arrived to Funan by ship, the local princess tried to capture it, but was forced to surrender, the two eventually marrying to end the war. The [[Champa|Cham]] king [[Mỹ Sơn#Prakasadharma|Prakasadharma]] (Vikrantavarman I) of 657 also relates his ancestry in an inscription to the episode of Kaundinya settling his spear in a certain place, taking Somadevi, daughter of the Nagas, as his wife and starting a family, beginning the first Funan dynasty. In Sri Lanka, during the reign of the [[The Five Dravidians]] of the [[Early Pandyan Kingdom|early Pandyan kingdom]], traditions mention how Queen Somadevi of [[Eelam]] was taken by a Tamil chief to Tamilakkam as his wife during war. She later gave birth to a future king, Chora-Naga. |

|||

The ''Proceedings of the First Annual Congress'' of South Indian History also notes: The word ''Tondai'' means a creeper and the term ''Pallava'' conveys a similar meaning.<ref name="Proceedings">{{cite book|author=South Indian History Congress.|title=Proceedings of the First Annual Conference|Volume=1|date=February 15–17|year=1980|publisher=The Congress, 1980}}</ref> KA Nilakanta Sastri postulated that Pallavas were descendants of a North Indian dynasty of Indian origin who moved down South, adopted local traditions to their own use, and named themselves after the land called Tondai as Tondaiyar.<ref name="Proceedings"/><ref name="Krishnaswami">{{cite book|author=A.Krishnaswami|title=Topics in South Indian history: from early times upto 1565 A.D.|pages=89–90|publisher=Krishnaswami, 1975}}</ref> KP Jayaswal also proposed a North Indian origin for them, putting forward the theory that the Pallavas were a branch of the [[Vakatakas]].<ref name="Proceedings"/> The association with Vakatakas is corroborated by the fact that the Pallavas adopted imperial Vakataka heraldic marks, as is evident from Pallava insignia. The Pallavas had on their seal, the Ganga and Yamuna, known to be Vakataka insignia<ref name="BRS">{{cite book|author=Bihar Research Society|title=The Journal of the Bihar Research Society|volume=19|pages=183–184|year=1933}}</ref> |

|||

==Early Pallavas== |

|||

In Tamil literature, the [[Sangam_literature|Sangam Period]] classic, [[Manimekhalai]] describes the origin of the first Pallava King from a liaison between the daughter of a Naga king of Manipallava named Pilli Valai (Pilivalai), with a Chola King Killivalavan, out of which union was born a prince,<ref name="Gangoly">{{cite book|author=Ordhendra Coomar Gangoly|title=The art of the Pallavas, Volume 2 of Indian Sculpture Series|page=2|publisher=G. Wittenborn, 1957}}</ref> who was lost in ship wreck and found with a twig (pallava) of Cephallandra indica (Tondai) around his ankle and hence named ''Tondai-man''.<ref name="Gangoly"/> Another version states "Pallava" was born from the union of Asvathama with a Naga Princess<ref name="Gangoly"/> also supposedly supported in the sixth verse of the Bahur plates which states "From Asvathama was born the king named Pallava".<ref name="Gangoly"/> Since Pallavas ruled in the territory extending from Bellary to Bezwada, it led to the probability of a theory that the Pallavas were a northern dynasty who having contracted marriages with princesses of the Andhra Dynasty inherited a portion of Southern Andhra Pradesh.<ref name="Gangoly"/><ref name="Gabriel">{{cite book|author=Gabriel Jouveau-Dubreuil|title=The Pallavas|pages=13-14|publisher=Asian Educational Services, 1995|url=http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=6o9XCT3XiaMC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> |

|||

{{Expand section|date=July 2012}} |

|||

[[Origin of Pallava|Four family dynastic lines]] of the Pallavas have been traced to at least the second century of the common era. Under Skandavarman I (315), the greatest of the early Pallava rulers of Kanchi, the state extended its dominions in the early fourth century north of Aruva Nadu from the South [[Penner River]] to the northern Telugu districts of [[Godavari]] and the [[Krishna River]], while expanding west passed the city of [[Bellary]]. He was crowned with the epithet ''Yuvamaharaja Shivaskandavarman'', a ruler with many subordinate chiefs who conducted several horse sacrifices. One of his inscriptions mentions the ''Vallave'' (herdsmen) and ''Govallave'' (cow herdsmen) of Pallava society. [[Amravati]] flourished as a great Buddhist learning centre under Pallava rule, while maritime commercial trade and cultural exchange grew. Pallava citizens settled in [[Ceylon]] and [[Far East Asia]]. Shivaskandavarman was succeeded by Vijayaskandavarman of Kanchi. |

|||

As the Pallavas of Kanchi grew in strength, so too did the medieval [[Telugu Cholas]], descended from the Sangam Chola emperor [[Karikala Chola]] who ruled in 180. According to this dynasty's inscriptions, the monarch's subordinate king Trilochana Pallava lost his third eye for refusing to carry out orders to construct the floodbanks of the [[Kaveri River]]. Folklore traditions and later inscriptions in Telugu mention this famous monarch as the earliest Telugu king in history.<ref>KR Subramanian. (1989). Buddhist remains in Āndhra and the history of Āndhra between 224 & 610 A.D, p.71: [http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=vnO2BMPdYEoC&pg=PA71&dq=pallava+telugu&hl=en&ei=csi3Tu_WEsO3rAeCtoH4Aw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=pallava%20telugu&f=false]</ref> A parallel unbroken line of contemporary Telugu Pallava kings, twenty-four of them in number and cousins to the Middle Pallava Kanchi line, appear to have ruled at a city north of Aruva Nadu following the reign of Vishnugopa in 340. Their stronghold was Dasanapura, modern day [[Darsi]], [[Nellore district]].<ref name="HH 1931">Rev. H Heras, SJ (1931) Pallava Genealogy: An attempt to unify the Pallava Pedigrees of the Inscriptions, Indian Historical Research Institute</ref><ref>Paramanand Gupta. (1973). Geography in ancient Indian inscriptions, up to 650 A.D, p.69</ref><ref>Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti. (2009). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age, p.279 [http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=dnhDAAAAYAAJ&q=Dasanapura+darsi&dq=Dasanapura+darsi&hl=en&ei=g2e6ToGmPIeyrAfM-7zPBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAQ]</ref> The earliest inscriptions of these Pallavas were found in the districts of [[Bellary]], [[Guntur]] and [[Nellore]].<ref name="SKR 71">KR Subramanian. (1989). Buddhist remains in Āndhra and the history of Āndhra between 224 & 610 A.D, p.71</ref> The early Pallava state grew to rule over several areas of the modern states of Andhra Pradesh and [[Karnataka]]. |

|||

The Velurpalaiyam Plates states this of Simhavishnu:<ref name="Gabriel"/> |

|||

<blockquote> He quickly seized the country of the Cholas embellished by the daughter of Kavira (i.e. the river Kaveri), whose ornaments are the forests of paddy (fields), and where (are found) brilliant groves of areca (palms).</blockquote> Hence, the Chola country did not originally belong to the Pallavas and that it was the Pallava King, Simhavishnu who captured the Chola country.<ref name="Gabriel"/>. This military operation was opposed by many southern kings which can be discerned from the Kasakudi Plates which state that Simhavishnu vanquished the following rulers:<ref name="Gabriel"/><blockquote> The Malaya, Kalabhra, Malava, Chola and Pandya (kings), the Simhala (kings) who was proud of the strength of his arms, and the Keralas.</blockquote> |

|||

==Middle Pallavas== |

|||

The Velurpalaiyam Plates credit the capture of Kanchi from the [[Chola dynasty|Cholas]] to the reign of the fifth king of the Pallava line Kumaravishnu I.<ref name="HH 1931"/> Thereafter Kanchi figures in inscriptions as the capital of the Pallavas. The Cholas drove the Pallavas away from Kanchi in mid-4th century CE, in the reign of Vishugopa, the tenth king of the Pallava line.<ref name="HH 1931"/> The Pallavas re-captured Kanchi in the mid-6th century, possibly in the reign of Simhavishnu, the fourteenth king of the Pallava line, whom the Kasakudi plates state as "the lion of the earth". Thereafter the Pallavas held on to Kanchi till the 9th century CE, till the reign of their last king, Vijaya-Nripatungavarman.<ref name="HH 1931"/> |

|||

[[Image:Rock Cut Temple.jpeg|200px|right|thumb|Rock cut cave temple of [[Mahendravadi]], Tamil Nadu, built by [[Mahendravarman I]] c. 571]] |

|||

The Middle Pallavas ascension in the fourth century saw the dynasty adopt Sanskrit charters to chronicle its exploits, replacing Prakrit. The Cholas drove the Pallavas away from Kanchi in 340, during the reign of Vishnugopa.<ref name="HH 1931"/> Records in Prakrit detail how King Vishnugopa attacked the early Chola state, but was attacked by [[Samudra Gupta]] of the [[Gupta Empire]] of North India. Taking advantage of the weakening of Pallava power, [[Mayurasharma]] a native of [[Talagunda]] launched parallel attacks on the state and eventually declared independence from Kanchi following a dispute with a Pallava guardsman, forming the [[Kadamba dynasty]]. He had travelled to Kanchi with his guru to pursue Vedic studies; his declaration of sovereign power centered on land south of the [[Malaprabha River]]. Hostilities between the Pallavas and Kadambas continued in the following decades. Twenty years later, in 360, Kumaravishnu I captured Kanchi from the [[Chola dynasty|Chola Dynasty]] as recorded in the Velurpalaiyam Plates. His son, Buddhavarman, is noted to have fought hard against the Cholas. Thereafter Kanchi developed into the capital of the imperial Pallava dynasty. |

|||

Simhavarman I's reign from 435 - 436 finds mention in the Sanskrit Jaina work ''[[Lokavibhaga]]''. The poet [[Kalidasa]] visited his court, declaring the capital to be ''Nagareshu Kanchi'', the world's "greatest city." Simhavarman I was succeeded by his son Skandavarman, mentioned in the Udeyindaram plates. Both kings are mentioned in the Penukonda plates of King Madhava III of the [[Western Ganga Dynasty]] as having successfully crowned two Ganga kings. The Pallavas re-captured Kanchi in the mid-6th century, possibly in the reign of Simhavishnu, the fourteenth king of the Pallava line, whom the Kasakudi plates describes as "the lion of the earth". Thereafter the Pallavas held on to Kanchi till the 9th century CE, with the last king having been Vijaya-Nripatungavarman.<ref name="HH 1931"/> From sixth to eight centuries CE, the long struggle between the Pallavas and the [[Chalukya dynasty|Badami Chalukyas]] for the supremacy over the Tungabhadra-Krishna doab was the primary political activity in peninsular India. Chalukya ruler [[Pulakesi II|Pulikeshi II]] almost reached the Pallava capital at Kanchi, but peace was made between them by purchasing Vengi ([[Rayalaseema]]) to the Chalukyas. However Pulakeshin's second Pallava invasion ended in failure with Pallava ruler 'Vatapikonda' Narasimhavarman I occupying the Chalukya capital Vatapi. King Narasimhavarman also defeated the [[Pandya dynasty|Pandya]]s, the [[Chola dynasty|Chola]]s and the [[Chera dynasty|Chera]]s. Later, in 740 CE, Badami Chalukya ruler Vikramaditya II ended the Pallava supremacy in southern India permanently<ref>Ancient India, A History Textbook for Class XI, Ram Sharan Sharma, [[National Council of Educational Research and Training]], India pp 211-215</ref> and the Pallava dominions were passed to the Chola kings in 9th century CE. |

|||

Though [[Manimekhalai]] posits Ilam Tiriyan as a Chola, not a Pallava, historically however, the Velurpalaiyam plates dated to 852 CE, does not mention the Cholas. Instead it credits the Naga liaison episode, and creation of the Pallava line, to a different Pallava king named Virakurcha, while preserving its legitimizing significance:<ref name="RMD 189-241">Michael D Rabe. (1997). The Māmallapuram Praśasti: A Panegyric in Figures, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 57, No. 3/4 (1997), pp. 189-241</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>...from him (Aśvatthāman) in order (came) Pallava, the lord of the whole earth, whose fame was bewildering. Thence, came into existence the race of Pallavas... [including the son of Chūtapallava] Vīrakūrcha, of celebrated name, who simultaneously with (the hand of) the daughter of the chief of serpents grasped also the complete insignia of royalty and became famous. </blockquote> |

|||

The royal custom of using a series of descriptive honorific titles, ''birudas'', was particularly prevalent among the Pallavas. The birudas of Mahendravarman I are in Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu. The Telugu birudas show that his involvement with the Andhra region continued to be strong at the time he was creating his cave-temples in the Tamil region.<ref name="HM & PMI 109-130">Marilyn Hirsh (1987) Mahendravarman I Pallava: Artist and Patron of Māmallapuram, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 48, Number 1/2 (1987), pp. 109-130</ref> The suffix "Malla" was used by the Pallava rulers.<ref name="HM & PMI 109-130"/> Mahendravarman I used the biruda, ''Satrumalla'', "a warrior who overthrows his enemies", and his grandson Paramesvara I was called ''Ekamalla'' "the sole warrior or wrestler". Pallavas kings, persumably exalted ones, were known by their title, Mahamalla or the "great wrestler".<ref>Michael D Rabe. (1997). The Māmallapuram Praśasti: A Panegyric in Figures, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 57, Number 3/4 (1997), pp. 189-241</ref> |

|||

Historically, early relations between the Nagas and Pallavas became well established before the myth of Pallava's birth to Ashwatthama took root.<ref name="SKR 71"/> A ''praśasti'' (literally "praise"), composed in 753 CE on the dynastic eulogy in the Kasakadi (Kasakudi) plates, by the Pallava Trivikrama, traces the Pallava lineage from creation through a series of mythic progenitors, and then praises the dynasty in terms of two similes hinged together by triple use of the word avatara ("descent"), as below:<ref name="RMD 189-241"/> |

|||

<blockquote>From [them] descended the powerful, spotless Pallava dynasty [vaṁśāvatāra], which resembled a partial incarnation [aṃśāvatāra] of Visnu, as it displayed unbroken courage in conquering the circle of the world...and which resembled the descent of the Ganges [gaṅgāvatāra] as it purified the whole world.</blockquote> |

|||

{{TNhistory}} |

|||

The Pallavas were originally not a Tamil power, they were a native Telugu power; and Telugu Sources know of a Trilochana Pallava.<ref>KR Subramanian. (1989). Buddhist remains in Āndhra and the history of Āndhra between 224 & 610 A.D, p.71: ''The Pallavas were first a Telugu and not a Tamil power. Telugu traditions know a certain Trilochana Pallava as the earliest Telugu King and they are confirmed by later inscriptions.'' [http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=vnO2BMPdYEoC&pg=PA71&dq=pallava+telugu&hl=en&ei=csi3Tu_WEsO3rAeCtoH4Aw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=pallava%20telugu&f=false]</ref> The earliest inscriptions of the Pallavas were found in the districts of [[Bellary]], [[Guntur]] and [[Nellore]].<ref name="SKR 71">KR Subramanian. (1989). Buddhist remains in Āndhra and the history of Āndhra between 224 & 610 A.D, p.71</ref> After a careful study of Pallava genealogy with all the available material, of no less than 45 inscriptions, Rev. H. Heras put forth the theory that there was an unbroken line of Pallava kings, twenty-four of them in number, who originally ruled at some city of the Telugu country, possibly at Dasanapura, which the Darsi Copper Plates state as their ''adhisthana''.<ref name="HH 1931">Rev. H Heras, SJ (1931) Pallava Genealogy: An attempt to unify the Pallava Pedigrees of the Inscriptions, Indian Historical Research Institute</ref> Dasanapura has been identified as Darsi, in Nellore district.<ref>Paramanand Gupta. (1973). Geography in ancient Indian inscriptions, up to 650 A.D, p.69</ref><ref>Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti. (2009). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age, p.279 [http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=dnhDAAAAYAAJ&q=Dasanapura+darsi&dq=Dasanapura+darsi&hl=en&ei=g2e6ToGmPIeyrAfM-7zPBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAQ]</ref> |

|||

{{APhistory}} |

|||

==List of Pallava monarchs== |

|||

The Genealogy of Pallavas mentioned in the Māmallapuram Praśasti is as follows:<ref name="RMD 189-241"/> |

|||

The earliest documentation on the Pallavas are copper-plate grants,<ref name="earlygrant">Now referred to as the ''Mayidavolu'', ''Hirahadagalli'' and the ''British Museum'' plates – Durga Prasad (1988)</ref> belonging to Skandavarman I and written in [[Prakrit]].<ref name=sastri91>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', p91</ref> Skandavarman appears to have been the first great ruler of the early Pallavas, though there are references to other early Pallavas who may have been predecessors to Skandavarman.<ref>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', pp91–92</ref> He was heralded as Vijaya-Skandavarman or Shiva-Skandavarman. |

|||

* Vishnu |

|||

* Brahma |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Bharadvaja |

|||

* Drona |

|||

* Ashvatthaman |

|||

* Pallava |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Simhavarman I (circa 275 CE) |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Simhavarman IV (436 CE - circa 460 CE) |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Skandashishya |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Simhavisnu (circa 550-585 CE) |

|||

* Mahendravarman I (ca. 571-630 CE) |

|||

* Maha-malla Narasimhavarman I (630-668 CE) |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Paramesvaravarman I (669-690 CE) |

|||

* Rajasimha Narasimhavaram II (690-728 CE) |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Pallavamalla Nandivarman II (731-796 CE) |

|||

* Unknown / undecipherable |

|||

* Nandivarman III (846-69) |

|||

Skandavarman extended his dominions from the [[Krishna River|Krishna]] in the north to the [[Pennar]] in the south and to the [[Bellary]] district in the West. He performed the ''Aswamedha'' and other Vedic sacrifices and bore the title "Supreme King of Kings devoted to ''dharma''".<ref name=sastri91/> According to the available inscriptions of the Pallavas, the Pallavas could be divided into four separate families or dynasties.<ref>http://chestofbooks.com/history/india/South-India-Culture/Chapter-VIII-Early-History-Of-The-Pallavas.html</ref> A combination of dynastic plates and grants from the period mention their rule thus: |

|||

The royal custom of using a series of descriptive honorific titles, ''birudas'', was particularly prevalent among the Pallavas. The birudas of Mahendravarman I are in Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu. The Telugu birudas show Mahendravarman's involvement with the Andhra region continued to be strong at the time he was creating his cave-temples in the Tamil region.<ref name="HM & PMI 109-130">Marilyn Hirsh (1987) Mahendravarman I Pallava: Artist and Patron of Māmallapuram, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 48, Number 1/2 (1987), pp. 109-130</ref> The suffix "Malla" was used by the Pallava rulers.<ref name="HM & PMI 109-130"/> Mahendravarman I used the biruda, ''Satrumalla'', "a warrior who overthrows his enemies", and his grandson Paramesvara I was called ''Ekamalla'' "the sole warrior or wrestler". Pallavas kings, persumably exalted ones, were known by their title, Mahamalla or the "great wrestler".<ref name="RMD 189-241"/> |

|||

===Early Pallavas=== |

|||

==Expansions and conquests== |

|||

* ''Bappa'' - Virakurcha - married a Naga of Mavilanga (Kanchi) - ''The Great Founder of a Pallava lineage'' |

|||

The Pallavas were in conflict with major kingdoms at various periods of time. The early Pallavas came into conflict with the [[Kadamba Dynasty|Kadambas]], the rulers of northern Karnataka and Konkan in the fourth century CE. Soon, Pallavas recognized the authority of Kadambas over them. The Pallavas also contracted matrimonial relationships with Kadambas. According to the Velurpalaiyam Plates the mother of the Pallava king Nandivarman was a Kadamba princess named Aggalanimmati.<ref name="Gabriel"/> The Velurpalaiyam Palates also state that Nandivarman had to fight for his father's throne.<ref name="Gabriel"/> |

|||

* Simha Varman I (275–300 or 315–345) |

|||

* Skanda Varman I (345–355) (''Shivaskandavarman'') |

|||

===Middle Pallavas=== |

|||

The revolt led by the [[Kalabhra dynasty|Kalabhras]] was put down by the allied efforts of Pallavas, [[Pandyan Dynasty|Pandyas]] and [[Chalukya dynasty|Chalukyas]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} After the Kalabhra upheaval the long struggle between the Pallavas and Chalukyas of Badami for supremacy in peninsular India began. Both tried to establish control over the Krishna-Tungabhadra doab. Under Skandavarman I, the Pallavas extended their dominions north to the [[Krishna River]] and west to the [[Arabian Sea]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Although the Chalukya ruler Pulakeshin II almost reached the Pallava capitalm his second invasion ended in failure. The Pallava ruler Narasimhavarman occupied [[Vatapi]], defeated the Pandyas, Cholas and Cheras. The conflict resumed in the first half of the eight century with multiple Pallava setbacks. The Chalukyas overrun them completely in 740 CE, ending the Pallava supremacy in South India.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} King Vishnugopa attacked and weakened the early Chola state around Kanchi before facing defeat in 365 AD. |

|||

* Visnugopa (340–355) (''Yuvamaharaja Vishnugopa'') |

|||

* Kumaravisnu I (355–370) |

|||

* Skanda Varman II (370–385) |

|||

* Vira Varman (385–400) |

|||

* Skanda Varman III (400–435) |

|||

* Simha Varman II (435–460) |

|||

* Skanda Varman IV (460–480) |

|||

* Nandi Varman I (480–500) |

|||

* Kumaravisnu II (c. 500–510) |

|||

* Buddha Varman (c. 510–520) |

|||

* Kumaravisnu III (c. 520–530) |

|||

* Simha Varman III (c. 530–537) |

|||

===Later Pallavas=== |

|||

Emperor [[Simhavishnu]] joined [[Pandyan dynasty|Pandyan]] [[Kadungon]] in ending the [[Kalabhras dynasty|Kalabhra Interregnum]] by 550, reestablishing Pallava maritime power.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} [[Narasimhavarman I]] oversaw Pallava supremacy in peninsular India before their dominions eventually passed to the Chola kings in 880 AD. The dynasty's descendants established the [[Kadava|Kadava kingdom]] in the thirteenth century.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} |

|||

*[[Simhavishnu]] (537-570) |

|||

*[[Mahendravarman I]] 571–630 |

|||

*[[Narasimhavarman I]] (Mamalla) 630–668 |

|||

*[[Mahendravarman II]] 668–672 |

|||

*[[Paramesvaravarman I]] 672–700 |

|||

*[[Narasimhavarman II]] (Raja Simha) 700–728 |

|||

*[[Paramesvaravarman II]] 705–710 |

|||

*[[Nandivarman II]] (Pallavamalla) 732–796 |

|||

*[[Dantivarman]] 775–825 |

|||

*[[Nandivarman III]] 825–869 |

|||

*Nirupathungan (869–882) |

|||

*[[Aparajithavarman]] 882–901 |

|||

===Other traditions=== |

|||

Kanchipuram, the Pallava imperial capital, developed into a city of temples to many faiths under their rule. Literary, painting and music activity spread, the [[Bhakti movement]] of the [[Vaishnava]] [[Alvars]] and the [[Saiva]] [[Nayanars]] flourishing under Pallava royal patronage alongside [[Tamil Jain|Tamil Jainism]], [[Tamil Buddhism|Buddhism]] and [[Native Dravidian religion]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Largely Brahmanical Hindus,{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} they constructed the [[Kailasanathar Temple|Kailasanathar stone temples and sculptures]], the [[Ekambareswarar Temple]] and [[Kamakshi Amman Temple]] in Kanchi.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Becoming a major military, economic and cultural power in Asia, the dynasty extended their artistic prowess to the temples of [[Koneswaram temple|Koneswaram]], [[Ketheeswaram temple|Ketheeswaram]], [[Nalanda Gedige]], [[Thiriyai]] and [[Tenavaram temple|Tenavarai]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Founding the school of [[Zen Buddhism]], Pallava prince [[Bodhidarma]] transmitted his knowledge of the religion and [[martial arts]] techniques of [[Silambam]] to [[Silat]] and [[Kung-Fu]] at the [[Shaolin Monastery]] in the 5th century, attracting Chinese Buddhist pilgrims including [[Xuanzang]] to Kanchipuram in 642 to find a city of 80 Hindu shrines, 100 monasteries and 10000 monks under Narasimhavarman I.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} As trade with China increased, [[Narasimhavarman II|Rajasimha]] built the "Chinese Pagoda" of [[Nagapattinam]] to please their diplomats, merchants and monks at the Pallava court.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} |

|||

Telugu traditions know of a certain Trilochana Pallava as the earliest Telugu King, which is confirmed by later inscriptions |

|||

.<ref name="SKR 71"/> Trilochana Pallava was killed by a Chalukya King near Mudivemu, Cuddapah District. A Buddhist story describes Kala the Nagaraja, resembling the Pallava Kalabhartar as a king of the region near [[Krishna district]]. The Pallava Bogga may be identified with the kingdom of Kala in Andhra which had close and early maritime and cultural relations with Ceylon.<ref name="SKR 71"/> Rev Heras also identified King Bappa with Kalabhartar (aka Kalabhartri), "the head jewel of the family", whom Rev Heras proposes as the founder of the dynasty, detecting in the references to Bappa in the Hirahadagalli and Uruvapalli plates, "the flavour of antiquity and veneration which always surround the memory of the founder of a dynasty".<ref name="HH 1931"/> |

|||

==Etymology of Tondai== |

|||

The Pallavas joined the Chola Dynasty in settling and asserting commercial influence in Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia by the fourth century.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Pallava royal lineages were established in the [[Early history of Kedah|old kingdom of Kedah]] of the Malay Peninsula under Rudravarman I, [[Chenla]] under [[Bhavavarman I]], [[History of Champa|Champa]] under [[Fan Hu Ta|Bhadravarman I]] and the Kaundinya-Gunavarman line of the [[Kingdom of Funan|Funan]] in Cambodia, eventually their rule growing to form the [[Khmer Empire]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} |

|||

The word ''Tondai'' means a creeper and the term ''Pallava'' conveys a similar meaning.<ref name="Proceedings">{{cite book|author=South Indian History Congress.|title=Proceedings of the First Annual Conference|Volume=1|date=February 15–17|year=1980|publisher=The Congress, 1980}}</ref> KA Nilakanta Sastri postulated that Pallavas were descendants of a North Indian dynasty of Indian origin who moved down South, adopted local traditions to their own use, and named themselves after the land called Tondai as Tondaiyar.<ref name="Proceedings"/><ref name="Krishnaswami">{{cite book|author=A.Krishnaswami|title=Topics in South Indian history: from early times upto 1565 A.D.|pages=89–90|publisher=Krishnaswami, 1975}}</ref> |

|||

These dynasties' unique [[Dravidian architecture|Dravidian architectural]] style was introduced to build [[Angor Wat]] while Tamil cultural norms{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} spread across the continent, their surviving epigraphic inscriptions recording domestic societal life and their pivotal role in Asian trade routes.<ref name=International2000>{{cite book | last = International Tamil Language Foundation| first = |title = The Handbook of Tamil Culture and Heritage| year = 2000| publisher = International Tamil Language Foundation| location = Chicago| page = 877}}</ref><ref name=Sastri1949>{{cite book | last = Sastri| first = K.A. Nilakanta|title = South Indian Influences in the Far East| year = 1949| publisher = Hind Kitab Ltd.| location = Bombay| pages = 28 & 48}}</ref> Direct extensive contacts with these regions were maintained from the maritime commerce city [[Mamallapuram]], where [[Mahendravarman I]] and his son "Mahamalla" [[Narasimhavarman I]] built the [[Shore Temple]] of the [[Seven Pagodas of Mahabalipuram]]. |

|||

KP Jayaswal also proposed a North Indian origin for them, putting forward the theory that the Pallavas were a branch of the [[Vakatakas]].<ref name="Proceedings"/> The association with Vakatakas is corroborated by the fact that the Pallavas adopted imperial Vakataka heraldic marks, as is evident from Pallava insignia. The Pallavas had on their seal, the Ganga and Yamuna, known to be Vakataka insignia<ref name="BRS">{{cite book|author=Bihar Research Society|title=The Journal of the Bihar Research Society|volume=19|pages=183–184|year=1933}}</ref> |

|||

[[Khmer]] folklore and inscriptions relate the [[Kingdom of Funan|Funan dynasty]]’s origins with that of the Pallavas.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Around 180, the Kaundinya-Gunavarman line of the Khmer civilization was founded following the consummation of a relationship between Prince Kaundinya – a Brahman and worshipper of Ashwatthama - with Queen Somadevi of the Naga tribe.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Kang Tai, a Chinese envoy of the third century reports that when Kaundinya arrived to Funan by ship, the local princess tried to capture it, but was forced to surrender, the two eventually marrying to end the war.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} The [[Champa|Cham]] king [[Mỹ Sơn#Prakasadharma|Prakasadharma]] (Vikrantavarman I) of 657 also relates his ancestry in an inscription to the episode of Kaundinya settling his spear in a certain place, taking Somadevi, daughter of the Nagas, as his wife and starting a family, beginning the first Funan dynasty.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} In Sri Lanka, during the reign of the [[The Five Dravidians]] of the [[Early Pandyan Kingdom|early Pandyan kingdom]],{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} traditions mention how Queen Somadevi of [[Eelam]] was taken by a Tamil chief to Tamilakkam as his wife during war.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} She later gave birth to a future king, Chora-Naga.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} |

|||

The [[Sangam literature]] epic ''[[Manimekhalai]]'' describes that the first Pallava king, Ilam Thiraiyan (or younger Thiraiyan), was born of a liaison between a Naga princess named Pilli Valai (Pilivalai) and a Chola king named Killi ([[Killivalavan]]). Ilam Tiriyan was lost in a ship-wreck and found washed ashore with a twig (pallava) of the Tondai creeper, ''Cephalandra indica'', coiled around his ankle. Hence he derived the name Tondai-man from the Tondai creeper. He became an independent ruler and the territory ruled by him came to be known as ''Tondaimandalam'', or 'Realm of the Tondai'.<ref name="Gangoly">{{cite book|author=Ordhendra Coomar Gangoly|title=The art of the Pallavas, Volume 2 of Indian Sculpture Series|page=2|publisher=G. Wittenborn, 1957}}</ref> |

|||

PT Srinivasa Iyengar says 'Tondaiyar' means the "tribe whose symbol was the Tondai creeper". Tondai or ''Coccinia indica'' is commonly known as ''Kōvai'' in Tamil in modern times, but the name Doṇḍe is the ordinary name for the plant in Telugu.<ref name="PTSI">{{cite book|author=P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar|title=History of the Tamils: from the earliest times to 600 A.D.|page=401|publisher=Asian Educational Services|year=1929| |

|||

ISBN=81-206-0145-9, 9788120601451|url=http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=ERq-OCn2cloC&pg=PA401&dq=pallava+tondai&hl=en&sa=X&ei=oQ8VT7vtDs-xrAeF67GSAg&ved=0CEoQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=pallava%20tondai&f=false}}</ref> Hence, Doṇḍe became Tonde or Tondai. Coccinia indica is also known as Cephalandra indica. See [[Coccinia grandis]]. |

|||

==Politics== |

|||

The Pallavas attacked and weakened the early [[Chola dynasty|Chola state]] of the [[early Cholas|ancient period]]. The [[Gupta empire|Gupta emperor]] [[Samudragupta]] of Magadha brought King Vishnugopa of the Pallavas under his sway in the middle of the 4th century. At this time, the early Pallavas came into conflict with the [[Kadamba Dynasty|Kadambas]], the rulers of northern Karnataka and Konkan, eventually recognising Kadamba authority. During the reign of Simhavarman I, the [[Kalabhra dynasty|Kalabhra Interregnum]] affected the dynasty; it was eventually put down by the allied efforts of Pallavas, [[Pandyan Dynasty|Pandyas of Madurai]] and the [[Western Chalukya|Western Chalukyas]]. Emperor [[Simhavishnu]] reestablished Pallava maritime power one hundred years later, inheriting Tamil conquests of [[Eelam|Eela Nadu]], [[Ceylon]]. After the Kalabhra upheaval, the long struggle between the Pallavas and [[Chalukya dynasty|Chalukyas of Badami]] for supremacy in peninsular India began. Pallava ruler [[Narasimhavarman I]] occupied [[Vatapi]] following [[Pulakesi II]]'s defeat in the [[Battle of Vatapi]], defeating the Pandyas, Cholas and Cheras. The conflict resumed in the first half of the eight century with multiple Pallava setbacks, their dominions eventually passing to the Chola kings in 880 CE. |

|||

==Languagues used== |

==Languagues used== |

||

| Line 127: | Line 145: | ||

The entire body of the inscription is in an old form of Prakrit; but a short benediction in Sanskrit is added at its close, and the king's name on the seal is also written in its Sanskrit form. With regard to the date of the grant, Professor Buhler remarks that "it is impossible to say how the donor is connected with the other Pallava kings known from the sasanas as yet published, or to fix the period when he reigned", but he derives an argument for a tentative early date from the circumstance of its being written in Prakrit.<ref name="FT 1111-1124"/> |

The entire body of the inscription is in an old form of Prakrit; but a short benediction in Sanskrit is added at its close, and the king's name on the seal is also written in its Sanskrit form. With regard to the date of the grant, Professor Buhler remarks that "it is impossible to say how the donor is connected with the other Pallava kings known from the sasanas as yet published, or to fix the period when he reigned", but he derives an argument for a tentative early date from the circumstance of its being written in Prakrit.<ref name="FT 1111-1124"/> |

||

Assuming the correctness of the identification of the Pallavas with the pauranic Pahlavas, and of the Pahlavas with the Parthians, there are good historical grounds for supposing that Parthian colonies established themselves in the Deccan at a very early period.<ref name="FT 1111-1124"/> From the time of the separation of Bactria from |

Assuming the correctness of the identification of the Pallavas with the pauranic Pahlavas, and of the Pahlavas with the Parthians, there are good historical grounds for supposing that Parthian colonies established themselves in the Deccan at a very early period.<ref name="FT 1111-1124"/> From the time of the separation of Bactria from Scythia in the middle of the 3rd century BC, the tendency of the Bactrians, forced by the pressure of their western and northern neighbours, was to extend themselves southwards into India. The Parthians, after their conquest of the Bactrians about a century later, followed up their successes by overrunning the Indian provinces of Bactria. The natural effect of this latter movement was to press the conquered Indo-Bactrians still further southwards and eastwards into India, with the concurrent tendency on the side of the Parthians always to follow up the retreat of their vanquished foes. After another interval, the Indo-Parthians were themselves forced out of their possessions in Afghanistan, Punjab, and Upper India by the Scythian invasion, and their only possible refuge then was in the south.<ref name="FT 1111-1124"/> |

||

Foulkes says in the article "The Early Pallavas of Kánchípura" published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland as follows: |

Foulkes says in the article "The Early Pallavas of Kánchípura" published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland as follows: |

||

| Line 143: | Line 161: | ||

The crown had the power to confer grants of land for religious uses, for "the increase of the merit, longevity, power, and fame of his own family and race," and to exempt the grantees and their grant-lands from the payment of the customary taxes. When such land-grants were made, the agricultural "labourers," and the "kolikas" or village staff, were transferred with the land. These "labourers" received for their remuneration "half the produce," according to the system of varam.<ref name="FT 1111-1124"/> |

The crown had the power to confer grants of land for religious uses, for "the increase of the merit, longevity, power, and fame of his own family and race," and to exempt the grantees and their grant-lands from the payment of the customary taxes. When such land-grants were made, the agricultural "labourers," and the "kolikas" or village staff, were transferred with the land. These "labourers" received for their remuneration "half the produce," according to the system of varam.<ref name="FT 1111-1124"/> |

||

Village free of taxes were given to the Brahmanas. |

|||

==Early Pallavas== |

|||

The history of the early Pallavas has not yet been satisfactorily settled. The earliest documentation on the Pallavas is the three copper-plate grants, now referred to as the ''Mayidavolu'', ''Hirahadagalli'' and the ''British Museum'' plates (Durga Prasad, 1988) belonging to Skandavarman I and written in [[Prakrit]].<ref name=sastri91> Nilakanta Sastri. A History of South India, p.91</ref> Skandavarman appears to have been the first great ruler of the early Pallavas, though there are references to other early Pallavas who were probably predecessors of Skandavarman.<ref>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', p.91–92</ref> |

|||

==Description== |

|||

The word Pallava means "branch", in contrast with Chola meaning "new country", Pandiya meaning "old country" and Chera meaning "hill country" in Sangam Tamil lexicon.{{citation needed|date=January 2012}} |

|||

Between 105–150 CE, the ancient capital of the Cholas, [[Puhar]] or Kaveripoompuharpatinnam, was submerged in a [[tsunami]] during Killivalavan's reign; and he moved the capital to [[Urayur]] as noted by [[Ptolemy]].{{citation needed|date=January 2012}} The Chola king annexed a part of his territory as Tondaimandalam and presented it to his son, Ilam Tiriyan, who ruled the kingdom between 150–175 CE. He was a contemporary of [[Athiyamān Nedumān Añci]] and [[Avvaiyar|Avvaiyar I]].{{citation needed|date=January 2012}} |

|||

Some of the most illustrious Tamil bhakti poets like the Nayanmars [[Campantar|Sambandhar]] and [[Tirunavukkarasar]], Sanskrit poets Bharavi and Dandin, as well as the seashore rock-cut temples of Mahabalipuram belong to the Pallava era. They developed the [[Grantha alphabet|Pallava Grantha]] script, known as [[Grantha]] Tamil to write [[Sanskrit]] and [[Manipravalam]], an alphabet that would give rise to several other southeast Asian scripts.{{citation needed|date=January 2012}} Chinese traveller [[Hiuen Tsang]] visited [[Kanchipuram]] during Pallava rule and extolled their benign rule.{{citation needed|date=January 2012}}. |

|||

==Pallava Chronology== |

|||

The rule of the Pallavas apparently starts as early as 275 CE, but their greatest epoch corresponds to the 7th and 8th century.<ref>Avari, p186</ref> |

|||

===Early Pallavas=== |

|||

The history of the early Pallavas has not yet been satisfactorily settled. The earliest documentation on the Pallavas is the three copper-plate grants,<ref name="earlygrant">Now referred to as the ''Mayidavolu'', ''Hirahadagalli'' and the ''British Museum'' plates – Durga Prasad (1988)</ref> belonging to Skandavarman I and written in [[Prakrit]].<ref name=sastri91>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', p91</ref> Skandavarman appears to have been the first great ruler of the early Pallavas, though there are references to other early Pallavas who were probably predecessors of Skandavarman.<ref>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', pp91–92</ref> |

|||

Skandavarman extended his dominions from the [[Krishna River|Krishna]] in the north to the [[Pennar]] in the south and to the [[Bellary]] district in the West. He performed the ''Aswamedha'' and other Vedic sacrifices and bore the title of 'Supreme King of Kings devoted to ''dharma'''.<ref name=sastri91/> |

Skandavarman extended his dominions from the [[Krishna River|Krishna]] in the north to the [[Pennar]] in the south and to the [[Bellary]] district in the West. He performed the ''Aswamedha'' and other Vedic sacrifices and bore the title of 'Supreme King of Kings devoted to ''dharma'''.<ref name=sastri91/> |

||

In the reign of Simhavarman IV, who ascended the throne in 436 CE, the fallen prestige of the Pallavas was restored. He recovered the territories lost to the [[Vishnukundin]]s in the north up to the mouth of the Krishna. The early Pallava history from this period onwards is furnished by a dozen or so copper-plate grants in [[Sanskrit]]. They are all dated in the regnal years of the kings.<ref name=sastri92>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', |

In the reign of Simhavarman IV, who ascended the throne in 436 CE, the fallen prestige of the Pallavas was restored. He recovered the territories lost to the [[Vishnukundin]]s in the north up to the mouth of the Krishna. The early Pallava history from this period onwards is furnished by a dozen or so copper-plate grants in [[Sanskrit]]. They are all dated in the regnal years of the kings.<ref name=sastri92>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', p92</ref> |

||

With the accession of Nandivarman I (480–500 CE), the decline of the early Pallava family was seen. The [[Kadambas]] had their aggressions and attacked even the headquarters of the [[Pallavas]] with the Pallavas taking retaliatory measures by expelling and invading [[Kadamba Dynasty|Kadamba]] territories in [[Karnataka]]. In [[coastal Andhra]] the Vishnukundins established their ascendency. The Pallava authority was confined to Tondaimandalam. |

With the accession of Nandivarman I (480–500 CE), the decline of the early Pallava family was seen. The [[Kadambas]] had their aggressions and attacked even the headquarters of the [[Pallavas]] with the Pallavas taking retaliatory measures by expelling and invading [[Kadamba Dynasty|Kadamba]] territories in [[Karnataka]]. In [[coastal Andhra]] the Vishnukundins established their ascendency. The Pallava authority was confined to Tondaimandalam. |

||

With the accession of Simhavishnu, father of Mahendravarman I, (c. 575 CE), the Pallava revival began in the south. |

|||

==Middle Pallavas== |

|||

[[Image:Rock Cut Temple.jpeg|200px|right|thumb|Rock cut cave temple of [[Mahendravadi]], Tamil Nadu, built by [[Mahendravarman I]] c. 571]] |

|||

The Middle Pallavas ascension in the fourth century saw the dynasty adopt Sanskrit charters to chronicle its exploits, replacing Prakrit.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} The Cholas drove the Pallavas away from Kanchi in 340, during the reign of Vishnugopa.<ref name="HH 1931"/> Records in Prakrit detail how King Vishnugopa attacked the early Chola state, but was attacked by [[Samudra Gupta]] of the [[Gupta Empire]] of North India.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Taking advantage of the weakening of Pallava power, [[Mayurasharma]] a native of [[Talagunda]] launched parallel attacks on the state and eventually declared independence from Kanchi following a dispute with a Pallava guardsman, forming the [[Kadamba dynasty]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} He had travelled to Kanchi with his guru to pursue Vedic studies; his declaration of sovereign power centered on land south of the [[Malaprabha River]]. Hostilities between the Pallavas and Kadambas continued in the following decades.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Twenty years later, in 360, Kumaravishnu I captured Kanchi from the [[Chola dynasty|Chola Dynasty]] as recorded in the Velurpalaiyam Plates.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} His son, Buddhavarman, is noted to have fought hard against the Cholas.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Thereafter Kanchi developed into the capital of the imperial Pallava dynasty.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} |

|||

<!--The following chronology is gathered from these three charters: <ref name=sastri92/> |

|||

Simhavarman I's reign from 435 - 436 finds mention in the Sanskrit Jaina work ''[[Lokavibhaga]]''. The poet [[Kalidasa]] visited his court, declaring the capital to be ''Nagareshu Kanchi'', the world's "greatest city."{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Simhavarman I was succeeded by his son Skandavarman, mentioned in the Udeyindaram plates. Both kings are mentioned in the Penukonda plates of King Madhava III of the [[Western Ganga Dynasty]] as having successfully crowned two Ganga kings.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} The Pallavas re-captured Kanchi in the mid-6th century, possibly in the reign of Simhavishnu, the fourteenth king of the Pallava line, whom the Kasakudi plates describes as "the lion of the earth". Thereafter the Pallavas held on to Kanchi till the 9th century CE, with the last king having been Vijaya-Nripatungavarman.<ref name="HH 1931"/> From sixth to eight centuries CE, the long struggle between the Pallavas and the [[Chalukya dynasty|Badami Chalukyas]] for the supremacy over the Tungabhadra-Krishna doab was the primary political activity in peninsular India.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Chalukya ruler [[Pulakesi II|Pulikeshi II]] almost reached the Pallava capital at Kanchi, but peace was made between them by purchasing Vengi ([[Rayalaseema]]) to the Chalukyas. However Pulakeshin's second Pallava invasion ended in failure with Pallava ruler 'Vatapikonda' Narasimhavarman I occupying the Chalukya capital Vatapi.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} King Narasimhavarman also defeated the [[Pandya dynasty|Pandya]]s, the [[Chola dynasty|Chola]]s and the [[Chera dynasty|Chera]]s.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Later, in 740 CE, Badami Chalukya ruler Vikramaditya II ended the Pallava supremacy in southern India permanently<ref>Ancient India, A History Textbook for Class XI, Ram Sharan Sharma, [[National Council of Educational Research and Training]], India pp 211-215</ref> and the Pallava dominions were passed to the Chola kings in 9th century CE. |

|||

* [[Simhavarman I]] 275–300 CE |

|||

* [[Skandavarman]] |

|||

* [[Visnugopa]] 350 – 355 CE |

|||

* [[Kumaravishnu I]] 350–370 CE |

|||

* [[Skandavarman II]] 370–385 CE |

|||

* [[Viravarman]] 385–400 CE |

|||

* [[Skandavarman III]] 400–436 CE |

|||

* [[Simhavarman II]] 436–460 CE |

|||

* [[Skandavarman IV]] 460–480 CE |

|||

* [[Nandivarman I]] 480–510 CE |

|||

* [[Kumaravishnu II]] 510–530 CE |

|||

* [[Buddhavarman]] 530–540 CE |

|||

* [[Kumaravishnu III]] 540–550 CE |

|||

* [[Simhavarman III]] 550–560 CE --> |

|||

===Later Pallavas=== |

===Later Pallavas=== |

||

| Line 175: | Line 218: | ||

* [[Nandivarman III]] 825–869 CE |

* [[Nandivarman III]] 825–869 CE |

||

* [[Aparajithavarman]] 882–901 CE |

* [[Aparajithavarman]] 882–901 CE |

||

==List of Pallava monarchs== |

|||

The earliest documentation on the Pallavas are copper-plate grants,<ref name="earlygrant">Now referred to as the ''Mayidavolu'', ''Hirahadagalli'' and the ''British Museum'' plates – Durga Prasad (1988)</ref> belonging to Skandavarman I and written in [[Prakrit]].<ref name=sastri91>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', p91</ref> Skandavarman appears to have been the first great ruler of the early Pallavas, though there are references to other early Pallavas who may have been predecessors to Skandavarman.<ref>Nilakanta Sastri, ''A History of South India'', p.91–92</ref> He was heralded as Vijaya-Skandavarman or Shiva-Skandavarman. |

|||

According to S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar, the Pallavas could be divided into four separate families or dynasties some of whose connections are known and some unknown. At first surfaced a number of charters in Prakrit of which three are important. Then followed a dynasty which issued their charters in Sanskrit; following which came the family of the great Pallavas beginning with Simha Vishnu; and this was followed by a dynasty of the usurper Nandi Varman, another great Pallava. <ref>S.Krishnaswami Aiyangar. Some Contributions Of South India To Indian Culture. [[http://chestofbooks.com/history/india/South-India-Culture/Chapter-VIII-Early-History-Of-The-Pallavas.html]]</ref> A combination of dynastic plates and grants from the period mention their rule thus: |

|||

===Early Pallavas=== |

|||

* ''Bappa'' - Virakurcha - married a Naga of Mavilanga (Kanchi) - ''The Great Founder of a Pallava lineage'' |

|||

* Simha Varman I (275–300 or 315–345) |

|||

* Skanda Varman I (345–355) (''Shivaskandavarman'') |

|||

===Middle Pallavas=== |

|||

* Visnugopa (340–355) (''Yuvamaharaja Vishnugopa'') |

|||

* Kumaravisnu I (355–370) |

|||

* Skanda Varman II (370–385) |

|||

* Vira Varman (385–400) |

|||

* Skanda Varman III (400–435) |

|||

* Simha Varman II (435–460) |

|||

* Skanda Varman IV (460–480) |

|||

* Nandi Varman I (480–500) |

|||

* Kumaravisnu II (c. 500–510) |

|||

* Buddha Varman (c. 510–520) |

|||

* Kumaravisnu III (c. 520–530) |

|||

* Simha Varman III (c. 530–537) |

|||

===Later Pallavas=== |

|||

*[[Simhavishnu]] (537-570) |

|||

*[[Mahendravarman I]] 571–630 |

|||

*[[Narasimhavarman I]] (Mamalla) 630–668 |

|||

*[[Mahendravarman II]] 668–672 |

|||

*[[Paramesvaravarman I]] 672–700 |

|||

*[[Narasimhavarman II]] (Raja Simha) 700–728 |

|||

*[[Paramesvaravarman II]] 705–710 |

|||

*[[Nandivarman II]] (Pallavamalla) 732–796 |

|||

*[[Dantivarman]] 775–825 |

|||

*[[Nandivarman III]] 825–869 |

|||

*Nirupathungan (869–882) |

|||

*[[Aparajithavarman]] 882–901 |

|||

==Politics== |

|||

The Pallavas attacked and weakened the early [[Chola dynasty|Chola state]] of the [[early Cholas|ancient period]]. The [[Gupta empire|Gupta emperor]] [[Samudragupta]] of Magadha brought King Vishnugopa of the Pallavas under his sway in the middle of the 4th century. At this time, the early Pallavas came into conflict with the [[Kadamba Dynasty|Kadambas]], the rulers of northern Karnataka and Konkan, eventually recognising Kadamba authority. During the reign of Simhavarman I, the [[Kalabhra dynasty|Kalabhra Interregnum]] affected the dynasty; it was eventually put down by the allied efforts of Pallavas, [[Pandyan Dynasty|Pandyas of Madurai]] and the [[Western Chalukya|Western Chalukyas]]. Emperor [[Simhavishnu]] reestablished Pallava maritime power one hundred years later, inheriting Tamil conquests of [[Eelam|Eela Nadu]], [[Ceylon]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} After the Kalabhra upheaval, the long struggle between the Pallavas and [[Chalukya dynasty|Chalukyas of Badami]] for supremacy in peninsular India began. Pallava ruler [[Narasimhavarman I]] occupied [[Vatapi]] following [[Pulakesi II]]'s defeat in the [[Battle of Vatapi]], defeating the Pandyas, Cholas and Cheras. The conflict resumed in the first half of the eight century with multiple Pallava setbacks, their dominions eventually passing to the Chola kings in 880 CE. |

|||

===Kadava kingdom=== |

===Kadava kingdom=== |

||

| Line 225: | Line 226: | ||

Pallavas were followers of Hinduism and made gifts of land to gods and Brahmins. In line with the prevalent customs, some of the rulers performed the ''[[Aswamedha]]'' and other [[Historical Vedic religion|Vedic sacrifices]].<ref name=sastri92/> They were, however, tolerant of other faiths. The Chinese monk [[Xuanzang]] who visited [[Kanchipuram]] during the reign of Narasimhavarman I reported that there were 100 Buddhist monasteries, and 80 temples in Kanchipuram.<ref>Kulke and Rothermund, pp121–122</ref> |

Pallavas were followers of Hinduism and made gifts of land to gods and Brahmins. In line with the prevalent customs, some of the rulers performed the ''[[Aswamedha]]'' and other [[Historical Vedic religion|Vedic sacrifices]].<ref name=sastri92/> They were, however, tolerant of other faiths. The Chinese monk [[Xuanzang]] who visited [[Kanchipuram]] during the reign of Narasimhavarman I reported that there were 100 Buddhist monasteries, and 80 temples in Kanchipuram.<ref>Kulke and Rothermund, pp121–122</ref> |

||

Mahendravarman I was initially a patron of the [[Jain]] faith. He later re-converted to [[Hinduism]] under the influence of the Saiva saint [[Appar]].<ref>[http://www.tamilnation.org/sathyam/east/saivaism/63nayanmars.htm#_VPID_31 Appar]</ref> |

Mahendravarman I was initially a patron of the [[Jain]] faith. He later re-converted to [[Hinduism]] under the influence of the Saiva saint [[Appar]] with the revival of Hinduism during the Bhakti movement in [[South India]].<ref>[http://www.tamilnation.org/sathyam/east/saivaism/63nayanmars.htm#_VPID_31 Appar]</ref> |

||

==Pallava architecture== |

==Pallava architecture== |

||

Revision as of 13:33, 26 July 2012

Pallava dynasty பல்லவர் | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd -–9th century CE | |||||||||||

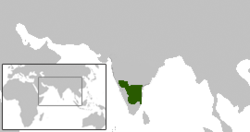

Pallava territories during Narasimhavarman I c. 645 CE. This includes the Chalukya territories occupied by the Pallavas. | |||||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||||

| Capital | Kanchi | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Tamil, Sanskrit, Telugu | ||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient-Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Established | 2nd - | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 9th century CE | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

Pallava dynasty (Tamil: பல்லவர்), also the Tondaiyar dynasty of Tondai Nadu, was a ruling dynasty of South India from the second to the ninth century CE. Establishing themselves as a rising Tamil power in the region with the metropolis Kanchipuram of Tamil Nadu as their capital, the Pallavas emerged after the Three Crowned Kings to become one of the major states of the post-Sangam period before the rise of the medieval Chola empire.[1] Four family dynastic lines of the Pallavas have been traced to at least the second century of the common era. An ancient Chola-Nāka alliance at Nainativu and succeeding Pallava-Naka liaisons marked the dynasty's formative years.[2] Centering their authority in Tondai Nadu, one Thiraiyar Pallava lineage gained prominence around Kanchi after the reign of Karikala Chola and the eclipse of the Satavahana dynasty of Andhra Pradesh in 220.[3][4]

From gaining power, the dynasty sought to expand their country passed the northern frontiers of Aruva Nadu in Tamilakkam. Under Skandavarman I, the Pallavas extended their dominions north to the Krishna River and west to the Arabian Sea, while King Vishnugopa attacked and weakened the early Chola state around Kanchi before facing defeat in 365. Emperor Simhavishnu joined Pandyan Kadungon in ending the Kalabhra Interregnum by 550, reestablishing Pallava maritime power and consolidating Tamil rule across Asia. Narasimhavarman I oversaw Pallava supremacy in peninsular India before their dominions eventually passed to the Chola kings in 880. The dynasty's descendants established the Kadava kingdom in the thirteenth century.

Kanchipuram, the Pallava imperial capital, developed into a city of temples to many faiths under their rule. Literary, painting and music activity spread, the Bhakti movement of the Vaishnava Alvars and the Saiva Nayanars flourishing under Pallava royal patronage alongside Tamil Jainism, Buddhism and Native Dravidian religion. Largely Brahmanical Hindus, they constructed the Kailasanathar stone temples and sculptures, the Ekambareswarar Temple and Kamakshi Amman Temple in Kanchi. Becoming a major military, economic and cultural power in Asia, the dynasty extended their artistic prowess to the temples of Koneswaram, Ketheeswaram, Nalanda Gedige, Thiriyai and Tenavarai. Founding the school of Zen Buddhism, Pallava prince Bodhidarma transmitted his knowledge of the religion and martial arts techniques of Silambam to Silat and Kung-Fu at the Shaolin Monastery in the 5th century, attracting Chinese Buddhist pilgrims including Xuanzang to Kanchipuram in 642 to find a city of 80 Hindu shrines, 100 monasteries and 10000 monks under Narasimhavarman I. As trade with China increased, Rajasimha built the "Chinese Pagoda" of Nagapattinam to please their diplomats, merchants and monks at the Pallava court.

The Pallavas joined the Chola Dynasty in settling and asserting commercial influence in Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia by the fourth century. Pallava royal lineages were established in the old kingdom of Kedah of the Malay Peninsula under Rudravarman I, Chenla under Bhavavarman I, Champa under Bhadravarman I and the Kaundinya-Gunavarman line of the Funan in Cambodia, eventually their rule growing to form the Khmer Empire. These dynasties' unique Dravidian architectural style was introduced to build Angor Wat while Tamil cultural norms spread across the continent, their surviving epigraphic inscriptions recording domestic societal life and their pivotal role in Asian trade routes.[5][6] Direct extensive contacts with these regions were maintained from the maritime commerce city Mamallapuram, where Mahendravarman I and his son "Mahamalla" Narasimhavarman I built the Shore Temple of the Seven Pagodas of Mahabalipuram. In the far east, the Pallavas established the South Indian doctrines of Saivism, Vaishnavism and state languages written in Pallava Grantha and Vatteluttu alphabet characters; these Tamil scripts would give rise to multiple writing systems in Asia over the next millennium, one of the Pallava's most enduring legacies.

Origins

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2012) |

The antiquity of this dynasty is evident from the mentions in ancient Tamil literature and in inscriptions. Later Pallavas also claimed in multilingual inscriptions and folklore traditions a long and ancient lineage to their dynasty. Mentions in the early Sangam literature (c. 150 CE)[7] indicate that the earliest kings of the dynasty antedated 250. Early Pallava script charters in Prakrit dated on paleographic grounds to 250-350 reveal that a dynasty named Pallava was active in the Tondai-Aruva region of Tamil Nadu in the latter stages of floruit of the Sangam period's Three Crowned Kings. One prominent dynastic line of this clan consolidated power at the city of Kanchipuram following the eclipse of the Satavahana dynasty of Andhra Pradesh in 220, whom the Pallavas had served as subordinates, while related family lines located around the country grew.

An ancient Chola-Nāka alliance at Nainativu and succeeding Pallava-Naka liaisons marked the dynasty's formative years. Seethalai Saathanar, author of the Tamil classic Manimekalai notes a union between Princess Pilli Valai of Nāka Nadu with King Killi of Chola Nadu at Nainativu - an islet he names Manipallavam; here was born Prince Tondai Ilandiraiyan (of the Thiraiyar/sea farer of Eelam lineage). Ilandiraiyan, a young contemporary of Karikala Chola became an independent ruler of Tondaimandalam around 200, stretching his Tondaiyar-Thiraiyar domain passed the Tirumala Venkateswara Temple, Tirupati whose construction he consecrated.[2] The earlier written poem Akananuru locates two Thiraiyar kings; an elder Tiriyan in Gudur, Nellore district, with a kingdom extending to Thiruvengadam, Tirupati,[8] distinguished from the younger Tiraiyan (Ilandiraiyan) whose capital was Kanchipuram.[8][9] The Sangam work Perumbanarruppatai traces the line of Ilandiraiyan to the Solar dynasty of Andhra Ikshvaku, who ruled in the late second century, while later Tamil commentators identify him with the Chola-Naka alliance.[8] Ilandiraiyan was a patron and poet during the Sangam period, obtaining the respect of the Three Crowned Kings. Some traditions describe him as Karikala's grandson and viceroy at Kanchi. Centering their authority in Tondai Nadu, Ilandiraiyan's descendants gained prominence as one Pallava line ruling Kanchi from 220.[10][11][12]

Nandivarman III's Velurpalaiyam plates of 852 credit the Chola-Naka liaison episode and creation of the Pallava line to a king named Virakurcha, son of Chutapallava.[13] A stanza reads "from Aśvatthāman in order (came) Pallava, the lord of the whole earth, whose fame was bewildering. Thence, came into existence the race of Pallavas... [including the son of Chūtapallava] Vīrakūrcha, of celebrated name, who simultaneously with (the hand of) the daughter of the chief of serpents grasped also the complete insignia of royalty and became famous..." Historically, early relations between the Nagas and Pallavas became well established.[14] A praśasti (literally "praise"), composed in 753 on the dynastic eulogy in the Kasakadi plates by Nandivarman II traces the Pallava lineage from creation through a series of mythic progenitors, then praises the dynasty in terms of two similes hinged together by triple use of the word avatara ("descent"), as follows[13] - "From [them] descended the powerful, spotless Pallava dynasty [vaṁśāvatāra], which resembled a partial incarnation [aṃśāvatāra] of Visnu, as it displayed unbroken courage in conquering the circle of the world...and which resembled the descent of the Ganges [gaṅgāvatāra] as it purified the whole world."

Khmer folklore and inscriptions relate the Funan dynasty’s origins with that of the Pallavas. Around 180, the Kaundinya-Gunavarman line of the Khmer civilization was founded following the consummation of a relationship between Prince Kaundinya – a Brahman and worshipper of Ashwatthama - with Queen Somadevi of the Naga tribe. Kang Tai, a Chinese envoy of the third century reports that when Kaundinya arrived to Funan by ship, the local princess tried to capture it, but was forced to surrender, the two eventually marrying to end the war. The Cham king Prakasadharma (Vikrantavarman I) of 657 also relates his ancestry in an inscription to the episode of Kaundinya settling his spear in a certain place, taking Somadevi, daughter of the Nagas, as his wife and starting a family, beginning the first Funan dynasty. In Sri Lanka, during the reign of the The Five Dravidians of the early Pandyan kingdom, traditions mention how Queen Somadevi of Eelam was taken by a Tamil chief to Tamilakkam as his wife during war. She later gave birth to a future king, Chora-Naga.

Early Pallavas

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2012) |