American Revolutionary War: Difference between revisions

move 'British logistics' to Talk:British Army during the American Revolution; move orphaned references to 'Further reading' here |

ce: remove to Talk:American Revolution, political background off-topic for military strategy & campaigning |

||

| Line 143: | Line 143: | ||

;Taxation and legislation |

;Taxation and legislation |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Boston Tea Party Currier colored.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.3|alt=Two ships in a harbor, one in the distance. On board, men stripped to the waist and wearing feathers in their hair throw crates of tea overboard. A large crowd, mostly men, stands on the dock, waving hats and cheering. A few people wave their hats from windows in a nearby building|<center>19th c. print of the 1774 [[Boston Tea Party]]</center>]] |

||

From their founding in the 17th century, the colonies were largely allowed to govern themselves; unlike the [[Spanish colonization of the Americas|Spanish Americas]], native-born property owners were allowed to participate in [[Colonial government in the Thirteen Colonies|colonial government]]. Although [[London]] managed external affairs, the colonists funded [[Militia (United States)|militia]] for defense against [[New France]] and their [[Indigenous peoples in Quebec|indigenous allies]]. Once this threat ended with the eviction of France from North America in [[Treaty of Paris (1763)|1763]], disputes arose between [[Parliament of Great Britain|Parliament]] and the colonies as to how these expenses should be paid.<ref>[[#bellot|Bellot 1960]], pp. 73-77</ref> With Britain's enlarged North American empire, the earlier Navigation Acts were expanded from mercantile regulation and repurposed for additional revenue.<ref>[[#morganmorgan|Morgan and Morgan 1963]], p. 96-97</ref> |

From their founding in the 17th century, the colonies were largely allowed to govern themselves; unlike the [[Spanish colonization of the Americas|Spanish Americas]], native-born property owners were allowed to participate in [[Colonial government in the Thirteen Colonies|colonial government]]. Although [[London]] managed external affairs, the colonists funded [[Militia (United States)|militia]] for defense against [[New France]] and their [[Indigenous peoples in Quebec|indigenous allies]]. Once this threat ended with the eviction of France from North America in [[Treaty of Paris (1763)|1763]], disputes arose between [[Parliament of Great Britain|Parliament]] and the colonies as to how these expenses should be paid.<ref>[[#bellot|Bellot 1960]], pp. 73-77</ref> With Britain's enlarged North American empire, the earlier Navigation Acts were expanded from mercantile regulation and repurposed for additional revenue.<ref>[[#morganmorgan|Morgan and Morgan 1963]], p. 96-97</ref> |

||

Parliament sought to expand British American settlement north into Nova Scotia and south into Florida as a hedge against French and Spanish designs respectively. At the [[Proclamation Line of 1763]], British policy was to limit Indian warfare to increase their trade revenue directly to the Crown. But maintaining the frontier peace for interior trade required policing against illicit colonial settlement. And that required British garrisons in the formerly French forts ceded by the Indians. Limiting colonial westward expansion was to be paid for by the Americans themselves by the [[Sugar Act|1764 Sugar Act]] and the [[Stamp Act|1765 Stamp Act]].<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 184</ref> |

Parliament sought to expand British American settlement north into Nova Scotia and south into Florida as a hedge against French and Spanish designs respectively. At the [[Proclamation Line of 1763]], British policy was to limit Indian warfare to increase their trade revenue directly to the Crown. But maintaining the frontier peace for interior trade required policing against illicit colonial settlement. And that required British garrisons in the formerly French forts ceded by the Indians. Limiting colonial westward expansion was to be paid for by the Americans themselves by the [[Sugar Act|1764 Sugar Act]] and the [[Stamp Act|1765 Stamp Act]].<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 184</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Philip Dawe (attributed), The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering (1774) - 02.jpg|thumb |upright=0.9 |alt=In the foreground, five leering men of the Sons of Liberty are holding down a Loyalist Commissioner of Customs agent, one holding a club. The agent is tarred and feathered, and they are pouring scalding hot tea down his throat. In the middle ground is the Boston Liberty Tree with a noose hanging from it. In the background, is a merchant ship with protestors throwing tea overboard into the habor. |<center>[[John Malcolm (Loyalist)|Loyalist]] customs official tarred and feathered by [[Sons of Liberty]].</center>]] |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Boston Tea Party Currier colored.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.3|alt=Two ships in a harbor, one in the distance. On board, men stripped to the waist and wearing feathers in their hair throw crates of tea overboard. A large crowd, mostly men, stands on the dock, waving hats and cheering. A few people wave their hats from windows in a nearby building|<center>19th c. print of the 1774 [[Boston Tea Party]]</center>]] |

||

Most of the frontier garrison expense was to be paid by the Sugar Act, which also renewed provisions of the old 1733 [[Molasses Act]].<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 183-184</ref> The economic effect was crippling for New England.<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 187</ref>{{efn|Eighty-five percent of New England's rum exports worldwide was manufactured from French molasses, prohibited to the French to protect their domestic Brandy industry. When the Lord Rockingham administration abolished the Stamp Act, it also reduced the tax on foreign molasses to one-penny a gallon in an explicit policy to help the New England economy recover and expand.<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 187</ref>}} |

Most of the frontier garrison expense was to be paid by the Sugar Act, which also renewed provisions of the old 1733 [[Molasses Act]].<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 183-184</ref> The economic effect was crippling for New England.<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 187</ref>{{efn|Eighty-five percent of New England's rum exports worldwide was manufactured from French molasses, prohibited to the French to protect their domestic Brandy industry. When the Lord Rockingham administration abolished the Stamp Act, it also reduced the tax on foreign molasses to one-penny a gallon in an explicit policy to help the New England economy recover and expand.<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 187</ref>}} |

||

Stamp Act monies were expected to be relatively small, an estimated 16% of American frontier expense. But with the passage of the Stamp Act, an innovative direct tax was placed on official documents. That provoked further unrest among colonists of every description who bought land, practiced law, read newspapers, or gambled with cards or dice.<ref>[[#morganmorgan|Morgan and Morgan 1963]], p. 96-97</ref>{{efn|Fifty colonial papermakers operating their own mills lost valuable local markets. All paper listed for colonial use had to come from Britain with an embossed stamp.<ref>[[#westlager|Westlager 1976]], p. 42</ref>}} The taxes had to be paid in scarce gold or silver, not in colonial legislature paper money.<ref>[[#morganmorgan|Morgan and Morgan 1963]], p. 42</ref> |

|||

Most dangerously for the Englishman's right to jury trial, the Stamp Act extended Admiralty Court jurisdiction beyond the high seas to violations in colonial ports, with the accused to stand trial in London. The accumulating discontent with Royal collections agents and Admiralty justice culminated in the 1773 [[Boston Tea Party]].<ref>[[#morganmorgan|Morgan and Morgan 1963]], p. 98</ref>{{efn|Colonial paper had been issued by all the North American colonial legislatures to increase local commerce in the cash-starved business environment. It allowed a limited financial independence from British merchant-creditors, and it permitted local funding for new manufacturers to begin in the otherwise deflated specie-only colonial economies. However the early 18th century practice was gradually ending, because additional paper money issues had been banned since 1764 .<ref>[[#watsonclark|Watson and Clark 1960]], p. 187</ref>}} The colonial legislatures argued the [[Stamp Act 1765|Stamp Act]] was illegal, since only they had the representative right to impose local taxes within their jurisdictions.<ref>[[#bonwick|Bonwick 1991]], pp 71-72</ref> They also claimed that their [[Rights of Englishmen|rights as Englishmen]] protected them from taxes imposed by a body in which they had [[no taxation without representation|no actual representation]].<ref>[[#gladney|Gladney 2014]], p. 5</ref> Prime Minister [[George Grenville]]'s defense to the effect that the colonies had a "[[virtual representation]]" in Parliament was dismissed on both sides of the Atlantic.<ref>[[#dickinson1977|Dickinson 1977]], p. 218</ref> Although the [[Chatham ministry]] of Whig [[William Pitt the Elder]] repealed the Stamp Act in 1766 to widespread rejoicing, it simultaneously [[Declaratory Act|re-affirmed Parliament's right]] to tax the colonies in the future.<ref>[[#McIlwain|McIlwain 1938]], p. 51</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | [[File:Philip Dawe (attributed), The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering (1774) - 02.jpg|thumb |upright=0.9 |alt=In the foreground, five leering men of the Sons of Liberty are holding down a Loyalist Commissioner of Customs agent, one holding a club. The agent is tarred and feathered, and they are pouring scalding hot tea down his throat. In the middle ground is the Boston Liberty Tree with a noose hanging from it. In the background, is a merchant ship with protestors throwing tea overboard into the habor. |<center> |

||

The 1767 [[Townshend Acts]] instituted new taxes on tea, lead, glass, and paper, but collection proved increasingly difficult. With the new revenue taxes came an enforcement policy from Parliament meant expressly for the American colonies and their widespread smuggling among the islands held by the Dutch, French, Spanish, and even other British colonies in the Caribbean Sea. The “Writs of Assistance” allowed British agent to arbitrarily conduct searches without warrants. |

|||

The Writs had been challenged in a ruling by [[James Otis Sr.]] in the Superior Court of Massachusetts. But on appeal to London the next year in 1762, Writs of Assistance for the colonies were upheld. For five years after the renewed 1767 enforcement, the Writs were challenged again in all thirteen colonial courts. In eight superior colonial courts they were refused. Where the colonial plaintiffs won, they were subsequently all overturned again in London.<ref>[[#wallenfeldt|Wallenfeldt 2015]], “Writ of Assistance”</ref> |

|||

When the British royal authorities seized the sloop ''[[HMS Liberty (1768)|Liberty]]'' in 1768 on suspicion of smuggling, it triggered a riot in Boston. Relations between Parliament and the colonies worsened after [[Frederick North, Lord North|Lord North]] became [[Prime Minister]] in January 1770, an office he held until just after the British defeat at [[Siege of Yorktown (1781)|Yorktown]]. He pursued tougher policies, including a threat to charge colonists with [[Treason Act 1543|treason]], although there was no support for this in Parliament; tensions then escalated in March 1770 when British troops fired on rock-throwing civilians [[Boston Massacre|in Boston]].<ref>[[#ferling2007|Ferling 2007]], p.23</ref> |

When the British royal authorities seized the sloop ''[[HMS Liberty (1768)|Liberty]]'' in 1768 on suspicion of smuggling, it triggered a riot in Boston. Relations between Parliament and the colonies worsened after [[Frederick North, Lord North|Lord North]] became [[Prime Minister]] in January 1770, an office he held until just after the British defeat at [[Siege of Yorktown (1781)|Yorktown]]. He pursued tougher policies, including a threat to charge colonists with [[Treason Act 1543|treason]], although there was no support for this in Parliament; tensions then escalated in March 1770 when British troops fired on rock-throwing civilians [[Boston Massacre|in Boston]].<ref>[[#ferling2007|Ferling 2007]], p.23</ref> |

||

| Line 187: | Line 179: | ||

Patriots were those who supported independence from Britain in their states and a new national union in Congress. Loyalists remained faithful to British imperial rule. Loyalists were usually minorities in each population, the appointed colonial officials, licensed merchants, Anglican churchmen, and the politically traditional. They were concentrated around port cities, on the New England Iroquois frontier and in the South near Cherokee settlement.<ref>[[#mays2019|Mays 2019]], p. 2</ref> Tories saw any subjects of the King who pretended to remove their ruler for whatever reasons as committing treason, and George III was encouraged to convict those responsible with the death penalty.<ref>[[#maier1998|Maier 1998]], p. 152</ref> |

Patriots were those who supported independence from Britain in their states and a new national union in Congress. Loyalists remained faithful to British imperial rule. Loyalists were usually minorities in each population, the appointed colonial officials, licensed merchants, Anglican churchmen, and the politically traditional. They were concentrated around port cities, on the New England Iroquois frontier and in the South near Cherokee settlement.<ref>[[#mays2019|Mays 2019]], p. 2</ref> Tories saw any subjects of the King who pretended to remove their ruler for whatever reasons as committing treason, and George III was encouraged to convict those responsible with the death penalty.<ref>[[#maier1998|Maier 1998]], p. 152</ref> |

||

In each state legislature, Patriots responded to the Loyalist challenge by passing Test Laws that required all residents to swear allegiance to their state.<ref>[[#boatner74|Boatner 1974]], p.1094</ref> These were meant to identify neutrals or to drive opponents of independence into self-exile. Failure to take the oath meant possible imprisonment, forced exile, or even death.<ref>[[#jasanoff2012|Jasanoff 2012]], p. 28</ref> American Tories were barred from public office, forbidden from practicing medicine and law, or forced to pay increased taxes. Some could not execute wills or become guardians.<ref>[[#bonwick|Bonwick 1991]], p. 152</ref> Congress enabled states to confiscate Loyalist property to fund the war.<ref>[[callahan|Callahan 1967]], p. 120</ref> |

|||

{{clear}} |

{{clear}} |

||

| Line 737: | Line 727: | ||

* {{cite book |last1=Black |first1=Jeremy |title=Fighting for America: The Struggle for Mastery in North America, 1519–1871 |date=2011 |url=https://www.amazon.com/Fighting-America-Struggle-Mastery-1519-1871/dp/0253356601 |publisher=Indiana University Press |isbn=9780253005618|ref=Black2011 |author-mask=2}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Black |first1=Jeremy |title=Fighting for America: The Struggle for Mastery in North America, 1519–1871 |date=2011 |url=https://www.amazon.com/Fighting-America-Struggle-Mastery-1519-1871/dp/0253356601 |publisher=Indiana University Press |isbn=9780253005618|ref=Black2011 |author-mask=2}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Boatner |first=Mark M. |title=Encyclopedia of the American Revolution' |publisher=D. McKay Company |year=1974 |orig-year=1966 |isbn=978-0-6795-0440-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hQN2AAAAMAAJ |ref=boatner74}} |

* {{cite book |last=Boatner |first=Mark M. |title=Encyclopedia of the American Revolution' |publisher=D. McKay Company |year=1974 |orig-year=1966 |isbn=978-0-6795-0440-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hQN2AAAAMAAJ |ref=boatner74}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Bonwick |first=Colin |title=The American Revolution |year=1991 |isbn=9780813913476 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B8tKlNRnc_wC |ref=bonwick}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Buchanan |first=John |title=The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-4711-6402-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zHh2AAAAMAAJ |ref=buchanan97}} |

* {{cite book |last=Buchanan |first=John |title=The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-4711-6402-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zHh2AAAAMAAJ |ref=buchanan97}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Burgoyne |first=John |editor=O'Callaghan, E. B. |title=Orderly book of Lieut. Gen. John Burgoyne, from his entry into the state of New York until his surrender at Saratoga, 16th Oct. 1777 |author-link=John Burgoyne |publisher=Albany, N.Y., J. Munsell |year=1860 |isbn= |url=https://archive.org/details/orderlybookoflie00burg |ref=burgoyne1860 |author-mask=2}} |

* {{cite book |last=Burgoyne |first=John |editor=O'Callaghan, E. B. |title=Orderly book of Lieut. Gen. John Burgoyne, from his entry into the state of New York until his surrender at Saratoga, 16th Oct. 1777 |author-link=John Burgoyne |publisher=Albany, N.Y., J. Munsell |year=1860 |isbn= |url=https://archive.org/details/orderlybookoflie00burg |ref=burgoyne1860 |author-mask=2}} |

||

| Line 748: | Line 737: | ||

* {{cite book |last=Cadwalader| first=Richard McCall |title=Observance of the One Hundred and Twenty-third Anniversary of the Evacuation of Philadelphia by the British Army: Fort Washington and the Encampment of White Marsh, November 2, 1777 |publisher=Press of the New Era Printing Company |url=https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniasoc00socigoog |isbn= |year=1901 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniasoc00socigoog/page/n26 20]–28|accessdate=January 7, 2016 |ref=cadwalader1901}} |

* {{cite book |last=Cadwalader| first=Richard McCall |title=Observance of the One Hundred and Twenty-third Anniversary of the Evacuation of Philadelphia by the British Army: Fort Washington and the Encampment of White Marsh, November 2, 1777 |publisher=Press of the New Era Printing Company |url=https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniasoc00socigoog |isbn= |year=1901 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniasoc00socigoog/page/n26 20]–28|accessdate=January 7, 2016 |ref=cadwalader1901}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Calhoon |first1=Robert McCluer |title=The Loyalists in Revolutionary America, 1760-1781 |isbn=978-0801490088 |publisher= Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. |date=1973 |url=https://www.amazon.com/Loyalists-Revolutionary-1760-1781-Founding-American/dp/0151547459 |ref=Calhoon1973 |quote=The Founding of the American Republic Series}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Calhoon |first1=Robert McCluer |title=The Loyalists in Revolutionary America, 1760-1781 |isbn=978-0801490088 |publisher= Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. |date=1973 |url=https://www.amazon.com/Loyalists-Revolutionary-1760-1781-Founding-American/dp/0151547459 |ref=Calhoon1973 |quote=The Founding of the American Republic Series}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Callahan |first=North |title=Flight of the Tories from the Republic, The Tories of the American Revolution |year=1967 |url=https://www.amazon.com/Flight-Republic-Tories-American-Revolution/dp/B0006BQPQG |asin= B0006BQPQG |publisher=Bobb-Merrill |ref=callahan}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Calloway |first=Colin G. |title=The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America |isbn= 978-0195331271 |year=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XtxG369-VHQC&vq=mercenaries |ref=calloway2007}} |

* {{cite book |last=Calloway |first=Colin G. |title=The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America |isbn= 978-0195331271 |year=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XtxG369-VHQC&vq=mercenaries |ref=calloway2007}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Cannon |first1=John |last2=Crowcroft |first2=Robert |title=The Oxford Companion to British History |year=2015 |publisher=Oxford University Press |edition=2 |isbn=978-0-1996-7783-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9vL8CgAAQBAJ |ref=cannon2015}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Cannon |first1=John |last2=Crowcroft |first2=Robert |title=The Oxford Companion to British History |year=2015 |publisher=Oxford University Press |edition=2 |isbn=978-0-1996-7783-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9vL8CgAAQBAJ |ref=cannon2015}} |

||

| Line 777: | Line 765: | ||

* {{cite news |last=Deane |first=Mark |title=That time when Spanish New Orleans helped America win independence |url=https://wgno.com/news-with-a-twist/nola-300-that-time-when-spanish-new-orleans-helped-america-win-independence/ |date=May 14, 2018 |access-date=6 October 2020 |work=WGNO-ABC-TV|ref=Deane2018 |quote=Exhibit at the Cabildo Museum, ‘Recovered Memories: Spain, New Orleans, and the Support for the American Revolution’}} |

* {{cite news |last=Deane |first=Mark |title=That time when Spanish New Orleans helped America win independence |url=https://wgno.com/news-with-a-twist/nola-300-that-time-when-spanish-new-orleans-helped-america-win-independence/ |date=May 14, 2018 |access-date=6 October 2020 |work=WGNO-ABC-TV|ref=Deane2018 |quote=Exhibit at the Cabildo Museum, ‘Recovered Memories: Spain, New Orleans, and the Support for the American Revolution’}} |

||

* {{cite book |editor=Debrett, J. |url=https://archive.org/details/parliamentaryre11parlgoog/page/n2/mode/2up |title=Parliamentary Register, House of Commons, Fifteenth Parliament of Great Britain |volume=1 |year=1781 |ref=Debrett1781}} |

* {{cite book |editor=Debrett, J. |url=https://archive.org/details/parliamentaryre11parlgoog/page/n2/mode/2up |title=Parliamentary Register, House of Commons, Fifteenth Parliament of Great Britain |volume=1 |year=1781 |ref=Debrett1781}} |

||

* {{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YKYOAAAAQAAJ |title=Liberty and Property: Political Ideology in Eighteenth-century Britain – H.T. Dickinson |year=1977 |isbn=978-0-416-72930-6 |last1=Dickinson |first1=H. T |ref=dickinson1977}} |

|||

* {{cite book |editor=Donne, W. Bodham |title=The correspondence of King George the Third with Lord North from 1768 to 1783 |year=1867 |volume=2 |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b750334&view=1up&seq=5 |ref=donne |quote=online at Hathi Trust}} |

* {{cite book |editor=Donne, W. Bodham |title=The correspondence of King George the Third with Lord North from 1768 to 1783 |year=1867 |volume=2 |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b750334&view=1up&seq=5 |ref=donne |quote=online at Hathi Trust}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Duffy |first=Christopher |title=The Military Experience in the Age of Reason, 1715–1789 |publisher=Routledge |year=2005 |orig-year=1987 |isbn=978-1-1357-9458-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zZiRAgAAQBAJ |ref=duffy1987}} |

* {{cite book |last=Duffy |first=Christopher |title=The Military Experience in the Age of Reason, 1715–1789 |publisher=Routledge |year=2005 |orig-year=1987 |isbn=978-1-1357-9458-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zZiRAgAAQBAJ |ref=duffy1987}} |

||

| Line 811: | Line 798: | ||

* {{cite book |last=Gaff |first=Alan D. |title=Bayonets in the Wilderness. Anthony Waynes Legion in the Old Northwest |publisher=University of Oklahoma Press |location=Norman |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-8061-3585-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QEI11WSV3WcC&vq=Augustin |ref=gaff}} |

* {{cite book |last=Gaff |first=Alan D. |title=Bayonets in the Wilderness. Anthony Waynes Legion in the Old Northwest |publisher=University of Oklahoma Press |location=Norman |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-8061-3585-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QEI11WSV3WcC&vq=Augustin |ref=gaff}} |

||

* {{cite archive |author1=George III, his Britannic Majesty |author2=Commissioners of the United States of America |item=Preliminary Articles of Peace |date=30 November 1782 |url=https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/prel1782.asp |access-date=6 October 2020 |collection=18th Century; British-American Diplomacy |institution=Yale Law School Avalon Project |ref=geoIII1782 |quote=Nine articles}} |

* {{cite archive |author1=George III, his Britannic Majesty |author2=Commissioners of the United States of America |item=Preliminary Articles of Peace |date=30 November 1782 |url=https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/prel1782.asp |access-date=6 October 2020 |collection=18th Century; British-American Diplomacy |institution=Yale Law School Avalon Project |ref=geoIII1782 |quote=Nine articles}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Gladney |first=Henry M. |title=No Taxation without Representation: 1768 Petition, Memorial, and Remonstrance |year=2014 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mGbmoQEACAAJ |isbn=978-1-4990-4209-2 |ref=gladney}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Glattharr |first=Joseph T. | title=Forgotten Allies |year=2007 |url=https://www.amazon.com/Forgotten-Allies-Indians-American-Revolution/dp/0809046008 |isbn=978-0809046003 |publisher=Hill & Wang |ref=glatthaar}} |

* {{cite book |last=Glattharr |first=Joseph T. | title=Forgotten Allies |year=2007 |url=https://www.amazon.com/Forgotten-Allies-Indians-American-Revolution/dp/0809046008 |isbn=978-0809046003 |publisher=Hill & Wang |ref=glatthaar}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Gordon |first1=John W. |last2=Keegan |first2=John |title=South Carolina and the American Revolution: A Battlefield History |year=2007 |isbn=9781570034800 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UYqYDMxOcc4C |ref=gordon}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Gordon |first1=John W. |last2=Keegan |first2=John |title=South Carolina and the American Revolution: A Battlefield History |year=2007 |isbn=9781570034800 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UYqYDMxOcc4C |ref=gordon}} |

||

| Line 885: | Line 871: | ||

* {{cite book |last=McCusker |first=John J. |title=Essays in the economic history of the Atlantic world |publisher=Routledge |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-415-16841-0 |location=London |oclc=470415294 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=a2-GAgAAQBAJ&vq=mercenaries |ref=mccusker1997}} |

* {{cite book |last=McCusker |first=John J. |title=Essays in the economic history of the Atlantic world |publisher=Routledge |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-415-16841-0 |location=London |oclc=470415294 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=a2-GAgAAQBAJ&vq=mercenaries |ref=mccusker1997}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=McGuire |first=Thomas J. |title=Stop the Revolution: America in the Summer of Independence and the Conference for Peace |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OsNi7Byog6kC&pg=PA166|year=2011|publisher=Stackpole Books |isbn=978-0-8117-4508-6 |ref=mcguire2011}} |

* {{cite book |last=McGuire |first=Thomas J. |title=Stop the Revolution: America in the Summer of Independence and the Conference for Peace |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OsNi7Byog6kC&pg=PA166|year=2011|publisher=Stackpole Books |isbn=978-0-8117-4508-6 |ref=mcguire2011}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=McIlwain |first=Charles Howard |title=The American Revolution: A Constitutional Interpretation |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uPCOs3MBUUEC |year=2005 |orig-year=1938 |isbn=978-1-58477-568-3 |ref=McIlwain}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal |last=Middleton | first=Richard |date=2014 |title=Naval Resources and the British Defeat at Yorktown, 1781 |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00253359.2014.866373 |journal=The Mariner's Mirror |volume=100 |issue=1 |pages=29–43| doi=10.1080/00253359.2014.866373| s2cid=154569534 |ref=middleton2014}} |

* {{Cite journal |last=Middleton | first=Richard |date=2014 |title=Naval Resources and the British Defeat at Yorktown, 1781 |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00253359.2014.866373 |journal=The Mariner's Mirror |volume=100 |issue=1 |pages=29–43| doi=10.1080/00253359.2014.866373| s2cid=154569534 |ref=middleton2014}} |

||

* {{cite book |editor=Miller, Hunter |title=Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America: 1776-1818 <small>(Documents 1-40)</small> |volume=II|publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office |year=1931 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=huu6xgEACAAJ |ref=miller1931}} |

* {{cite book |editor=Miller, Hunter |title=Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America: 1776-1818 <small>(Documents 1-40)</small> |volume=II|publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office |year=1931 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=huu6xgEACAAJ |ref=miller1931}} |

||

| Line 892: | Line 877: | ||

* {{Cite book |last=Montero |first=Francisco Maria |title=Historia de Gibraltar y de su campo |publisher=Imprenta de la Revista Médica |year = 1860 |language=Spanish |page=356 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bHRmkdBONd0C |ref=montero}} |

* {{Cite book |last=Montero |first=Francisco Maria |title=Historia de Gibraltar y de su campo |publisher=Imprenta de la Revista Médica |year = 1860 |language=Spanish |page=356 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bHRmkdBONd0C |ref=montero}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Morgan |first=Edmund S. |title=The Birth of the Republic: 1763-1789 |year=2012 |orig-year=1956 | url=https://www.amazon.com/Republic-1763-89-Chicago-American-Civilization/dp/0226923428 |edition=fourth |isbn=978-0226923420 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |ref=morgan |quote=foreward by Joseph J. Ellis}} |

* {{cite book |last=Morgan |first=Edmund S. |title=The Birth of the Republic: 1763-1789 |year=2012 |orig-year=1956 | url=https://www.amazon.com/Republic-1763-89-Chicago-American-Civilization/dp/0226923428 |edition=fourth |isbn=978-0226923420 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |ref=morgan |quote=foreward by Joseph J. Ellis}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Morgan |first1=Edmund S. |last2=Morgan |first2=Helen M. |title=The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution |date=1995 |orig-year=First published 1963|url=https://www.amazon.com/Stamp-Act-Crisis-Revolution-University/dp/0807845132 |publisher= University of North Carolina Press |isbn= 978-0807845134 |ref=morganmorgan}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Morley |first=Vincent |title=Irish Opinion and the American Revolution, 1760–1783 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iBrJz9XYzNgC&pg=PA154 |year=2002 |publisher=Cambridge UP |isbn=978-1-1394-3456-0 |ref=morley2002}} |

* {{cite book |last=Morley |first=Vincent |title=Irish Opinion and the American Revolution, 1760–1783 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iBrJz9XYzNgC&pg=PA154 |year=2002 |publisher=Cambridge UP |isbn=978-1-1394-3456-0 |ref=morley2002}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Morrill |first=Dan|title=Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution|publisher=Nautical & Aviation Publishing |year=1993 |isbn=978-1-8778-5321-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RXh2AAAAMAAJ |ref=morrill}} |

* {{cite book|last=Morrill |first=Dan|title=Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution|publisher=Nautical & Aviation Publishing |year=1993 |isbn=978-1-8778-5321-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RXh2AAAAMAAJ |ref=morrill}} |

||

| Line 985: | Line 969: | ||

* {{cite book |last=Wallace |first=Willard M. |author-link=Willard M. Wallace |title=Traitorous Hero: The Life and Fortunes of Benedict Arnold |isbn=978-1199083234 |place=New York |publisher=Harper & Brothers |year=1954 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y192AAAAMAAJ |ref=wallace54}} |

* {{cite book |last=Wallace |first=Willard M. |author-link=Willard M. Wallace |title=Traitorous Hero: The Life and Fortunes of Benedict Arnold |isbn=978-1199083234 |place=New York |publisher=Harper & Brothers |year=1954 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y192AAAAMAAJ |ref=wallace54}} |

||

* {{cite web |url= https://www.britannica.com/event/American-Revolution | title=American Revolution |last1=Wallace |first1=Willard M. |last2=Ray |first2=Michael |date=21 September 2015 | website=Britannica |publisher=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=24 August 2020 |ref=wallaceray2015 |author-mask=2 |quote=American Revolution, (1775-83, insurrection by which 13 of Great Britain’s North American colonies won political independence and went on to form the United States of America.}} |

* {{cite web |url= https://www.britannica.com/event/American-Revolution | title=American Revolution |last1=Wallace |first1=Willard M. |last2=Ray |first2=Michael |date=21 September 2015 | website=Britannica |publisher=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=24 August 2020 |ref=wallaceray2015 |author-mask=2 |quote=American Revolution, (1775-83, insurrection by which 13 of Great Britain’s North American colonies won political independence and went on to form the United States of America.}} |

||

* {{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/writ-of-assistance |title=Writ of assistance, British-American colonial history |last=Wallenfeldt |first=Jeff |date=29 May 2015 |website=Britannica |publisher=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=25 August 2020 |quote=Customhouse officers were authorized to search any house for smuggled goods without specifying either the house or the goods. |ref=wallenfeldt}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Ward |first1=A.W. |last2= Prothero |first2=G.W. |title=Cambridge Modern History, vol.6 (18th Century) |year=1925 |publisher=University of Oxford, The University Press |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.107358/page/n503/mode/2up?q=Van+Tyne |quote=Digital Library of India Item 2015.107358 |ref=wardA1925}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Ward |first1=A.W. |last2= Prothero |first2=G.W. |title=Cambridge Modern History, vol.6 (18th Century) |year=1925 |publisher=University of Oxford, The University Press |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.107358/page/n503/mode/2up?q=Van+Tyne |quote=Digital Library of India Item 2015.107358 |ref=wardA1925}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Ward |first=Christopher |title=The War of the Revolution (2 volumes) |publisher=New York: Macmillan |year=1952 |isbn=9781616080808 |quote=History of land battles in North America |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ut5DCgAAQBAJ |ref=ward1952}} |

* {{cite book |last=Ward |first=Christopher |title=The War of the Revolution (2 volumes) |publisher=New York: Macmillan |year=1952 |isbn=9781616080808 |quote=History of land battles in North America |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ut5DCgAAQBAJ |ref=ward1952}} |

||

| Line 991: | Line 974: | ||

* {{cite book |last1=Watson |first1=J. Steven |last2=Clark |first2=Sir George |title=The Reign of George III, 1760-1815 |url=https://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=22810670 |year=1960 |isbn=978-0198217138 |publisher=Oxford University Press |ref=watsonclark}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Watson |first1=J. Steven |last2=Clark |first2=Sir George |title=The Reign of George III, 1760-1815 |url=https://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=22810670 |year=1960 |isbn=978-0198217138 |publisher=Oxford University Press |ref=watsonclark}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Weigley |first= Russell F. |title=The American Way of War |publisher=Indiana University Press |year=1977 |isbn=978-0-2532-8029-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=77wNLMJn8CEC |ref=weigley1977}} |

* {{cite book |last=Weigley |first= Russell F. |title=The American Way of War |publisher=Indiana University Press |year=1977 |isbn=978-0-2532-8029-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=77wNLMJn8CEC |ref=weigley1977}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Westlager |first1=Clinton Alfred |title=The Stamp Act Congress |date=1976 |url=https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Stamp_Act_Congress/0KV2AAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 |publisher=University of Delaware Press |isbn= 9780874131116 |ref=weslager}} |

|||

* {{cite web |last=White |first=Matthew |year=2010 |url= http://necrometrics.com/wars18c.htm#AmRev |title= Spanish casualties in The American Revolutionary war |publisher= Necrometrics |ref=white2020}} |

* {{cite web |last=White |first=Matthew |year=2010 |url= http://necrometrics.com/wars18c.htm#AmRev |title= Spanish casualties in The American Revolutionary war |publisher= Necrometrics |ref=white2020}} |

||

* {{cite book |title=The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780 |first=David K |last=Wilson |publisher=University of South Carolina Press |year=2005 |isbn=978-1-57003-573-9 |location=Columbia, SC |oclc=232001108 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X2GrR0Eyh-4C |ref=wilson2005}} |

* {{cite book |title=The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780 |first=David K |last=Wilson |publisher=University of South Carolina Press |year=2005 |isbn=978-1-57003-573-9 |location=Columbia, SC |oclc=232001108 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X2GrR0Eyh-4C |ref=wilson2005}} |

||

Revision as of 09:12, 14 October 2020

| American Revolutionary War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Left, Continental infantry at Redoubt 10, Yorktown; Washington rallying the broken center at Monmouth; USS Bonhomme Richard captured HMS Serapis | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

full list... |

full list... | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

United States: Unknown |

Great Britain: 13,000[25] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

United States: French & Spanish overseas:[31]

|

Great Britain: | ||||||||

The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), also known as the American War of Independence, was initiated by the thirteen original colonies in Congress against the Kingdom of Great Britain over their objection to Parliament's direct taxation and its lack of colonial representation.[p] From their founding in the 1600s, the colonies were largely left to govern themselves. When France left North America in 1763, the British Empire expanded, and the elected part of the colonial legislatures challenged how the new expenses should be paid. The new 1765 Stamp Act provoked an unrest that led to the 1773 Boston Tea Party. When Parliament answered with punitive measures on Massachusetts, twelve colonies responded with the First Continental Congress to boycott British goods.[q]

In June 1775, the Second Continental Congress appointed George Washington to create a Continental Army and oversee the capture of Boston. When their Olive Branch Petition to King and Parliament was rejected, the Patriots attacked British Quebec but failed. In July 1776, Congress unanimously passed the Declaration of Independence. Hopes of a quick settlement were increased by a substantial element within Parliament who opposed Lord North's "coercion policy" in the colonies.[r] However the new British commander in chief, General Sir William Howe launched a counter-offensive, capturing New York City. Washington retaliated with harassing attacks at Trenton and Princeton. Howe's 1777–1778 Philadelphia campaign captured that city, but the British were defeated at Saratoga in October 1777. At Valley Forge that winter, Washington built a professional army. American victory at Saratoga had dramatic consequences for the war. A few of the European "Enlightened rulers", especially the Dutch with a former colony in New York, supported the American rebellion with funds, provisions and arms via Sint Eustatius, a Dutch port in the Leeward Islands. But at the American victory at Saratoga capturing a British army, the French feared an early "American settlement" that would strengthen Britain.

Saratoga proved the Continental Army was capable of winning independence. The French saw an opportunity to weaken their British rivals and gain a new trading partner that would be militarily dependent on them. They made two treaties with Congress, the first for trade, and the second to protect that trade in the 1788 Treaty of Alliance.[s] In 1779, the war by Congress for independence from Britain,[58] gained more collateral help. The forty-five year-old Bourbon Family Pact between French and Spanish royalty was activated by their Aranjuez Convention. They began a war for global imperial expansion against Britain, including a Spanish Gibraltar. The Bourbons were cobelligerents with Congress against Britain for the next eighteen months.[59]

In North America, Spanish Louisiana Governor Bernardo Gálvez routed British forces from Spanish territory. The Spanish and American privateers supplied the 1779 Virginia militia conquest of Western Quebec (later the US Northwest Territory).[60] Gálvez then expelled British forces from Mobile and Pensacola, cutting off British military assistance to American Indian allies in the interior southeast. Howe's replacement, General Sir Henry Clinton, then mounted a 1778 "Southern strategy" from Charleston. After initial success taking Savannah, their losses at King's Mountain and Cowpens led to the British southern army retreat to Yorktown where it was besieged by Franco-American forces. A decisive French naval victory brought the October 1781 surrender of the second British army lost in the American Revolution. Shooting war between Britain and France allied with Spain continued for another two years.[t]

But at Yorktown, the British lost their will to contest American independence. The Tory government fell, replaced by Whig Lord Rockingham. George III promised American independence, and Anglo-American talks began. The Preliminary Peace was signed in November, and in December 1782, George III spoke from the British throne for US independence, trade, and peace between the two countries. In April 1783, Congress accepted the British-proposed treaty that met its peace demands including independence, British evacuation, territory to the Mississippi River, river navigation, and Newfoundland fishing rights. On September 3, 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed between Great Britain and the United States. Formal exchange of the treaties ratified by both Congress and Parliament were exchanged in Paris the following spring.

Background and political developments

In the three years 1607–1609, English Jamestown, French Quebec and Spanish Santa Fe were established as North American outposts of three European powers in their ongoing conflict and imperial competition.[63] At the edges of each North American sphere of influence, frontier settlements were interspersed in a babble of languages. From the first English settlement in Virginia north were Algonkin, Iroquoian, Siouan, French and English. Southerly were Iroquoian speakers in the Appalachian Mountains, Souian on the Atlantic coast, Muskegan in the southeast to the Mississippi, Spanish at the Gulf, and English on the seaboard. Just west of the Mississippi River were Siouan, French and Spanish.[64]

Early English settlement in Virginia and Massachusetts under Elizabeth I and successor James I pointedly recruited veterans from European religious wars in the Eighty Years' War, such as Virginia's Captain John Smith. These brought “hard war” tactics against every foe, whether native, nation-state or pirate, and they effectively schooled their successors in each British North American colony.[65][u]

Just a decade before the Revolution, the North American French and Indian War spread to Europe and their imperial territories as the Seven Years’ War.[67] At the 1763 Peace of Paris ending it, France was removed from North America, Spain expanded north and east to the Mississippi River, and the British formally abandoned the Stuart King colonial charters “from sea to sea”, accepting a western boundary of the “middle of the Mississippi River” with free navigation on it “to the open sea”. The Europeans changed their maps and everything on the American continent was disrupted: military alliances, trade networks, and any former economic stability.[68] The coming American Revolutionary War was set amidst this already unsettled world.

- Taxation and legislation

From their founding in the 17th century, the colonies were largely allowed to govern themselves; unlike the Spanish Americas, native-born property owners were allowed to participate in colonial government. Although London managed external affairs, the colonists funded militia for defense against New France and their indigenous allies. Once this threat ended with the eviction of France from North America in 1763, disputes arose between Parliament and the colonies as to how these expenses should be paid.[69] With Britain's enlarged North American empire, the earlier Navigation Acts were expanded from mercantile regulation and repurposed for additional revenue.[70]

Parliament sought to expand British American settlement north into Nova Scotia and south into Florida as a hedge against French and Spanish designs respectively. At the Proclamation Line of 1763, British policy was to limit Indian warfare to increase their trade revenue directly to the Crown. But maintaining the frontier peace for interior trade required policing against illicit colonial settlement. And that required British garrisons in the formerly French forts ceded by the Indians. Limiting colonial westward expansion was to be paid for by the Americans themselves by the 1764 Sugar Act and the 1765 Stamp Act.[71]

Most of the frontier garrison expense was to be paid by the Sugar Act, which also renewed provisions of the old 1733 Molasses Act.[72] The economic effect was crippling for New England.[73][v]

When the British royal authorities seized the sloop Liberty in 1768 on suspicion of smuggling, it triggered a riot in Boston. Relations between Parliament and the colonies worsened after Lord North became Prime Minister in January 1770, an office he held until just after the British defeat at Yorktown. He pursued tougher policies, including a threat to charge colonists with treason, although there was no support for this in Parliament; tensions then escalated in March 1770 when British troops fired on rock-throwing civilians in Boston.[75]

After the 1772 Gaspee Affair when a customs vessel was destroyed in Rhode Island, Parliament repealed all taxes other than that on tea. Partly designed to undercut illegal imports, it was also recognized as another attempt to assert their right to tax the colonies, so it did nothing to quiet opposition.[76] Following the Sons of Liberty protest at the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, Parliament passed a series of measures called the Intolerable Acts. While intended to narrowly punish Massachusetts, they were widely viewed as a threat to the liberty of all the colonies and gained widespread support among the Patriots in America and among the Whig Opposition in Parliament.[77]

- Colonial response

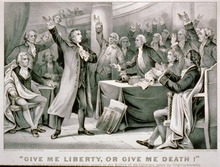

“Give me liberty or give me death!”

The elected members in the Royal colonial legislatures, those who represented the smaller landowners in the lower-house assemblies, responded by establishing ad hoc provincial legislatures, variously called Congresses, Conventions and Conferences. They effectively removed Crown control within their respective colonies. Twelve sent representatives to the First Continental Congress to develop a joint American response to the crisis.[78] [w] It passed a compact declaring a trade boycott against Britain.[79][x]

While the Congress also affirmed that Parliament had no authority over internal American matters, they also acquiesced to trade regulations for the benefit of the empire.[y] Awaiting some measure of reconciliation from Parliament and the King's Tory government, Congress authorized the extralegal committees and conventions of the colonial legislatures to enforce the Congressional boycott. In the event, the boycott was effective, as imports from Britain dropped by 97% in 1775 compared to 1774.[81]

by Adams[z], 1st Continental Congress

Parliament refused to yield to Congressional proposals. In 1775, it declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion and enforced a blockade of the colony.[82] It then passed the Restraining Acts of 1775 aimed at limiting colonial trade to the British West Indies and the British Isles. New England ships were barred from the Newfoundland cod fisheries. These increasing tensions led to a mutual scramble for ordnance between royal governors and the elected assemblies. British raids on colonial powder magazines pushed the assemblies towards open war. Each assembly was required by law to defend them for the purpose of providing arms and ammunition for frontier defense.[83] Thomas Gage was appointed the British Commander-in-Chief for North America. As military governor of Massachusetts he was ordered to disarm the local militias on April 14, 1775.[84] On April 19, the Battles of Lexington and Concord were fought between Massachusetts militia and British regulars, with scores of casualties.

- Political reactions

After fighting began, Congress launched an Olive Branch Petition in another attempt to avert war. George III rejected the offer as insincere because Congress also made contingency plans for muskets and gunpowder.[85] The King answered militia resistance at Bunker Hill with a Proclamation of Rebellion, which further provoked the Patriot faction in Congress.[86] Parliament rejected coercive measures on the colonies by 170 votes. The tentative Whig majority there feared an aggressive policy would drive the Americans towards independence.[87] Tories stiffened their resistance to compromise,[88] and the King himself began micromanaging the war effort.[89] The Irish Parliament pledged to send troops to America, and Irish Catholics were allowed to enlist in the army for the first time.[90][aa]

The initial hostilities in Boston caused a pause in British activity, they remained in New York City awaiting more troops.[92] That inactive response gave the Patriots a political advantage in the colonial assemblies, and the British lost control over every former colony.[93] The army in the British Isles had been deliberately kept small since 1688 to prevent abuses of power by the King.[94] To prepare for war overseas, Parliament signed treaties of subsidy with small German states for additional troops.[95] Within a year it had sent an army of 32,000 men to America.[96][ab]

At the onset of the war, the Second Continental Congress realized that they would need foreign alliances and intelligence-gathering capability to defeat a world power like Britain. To this end, they formed the Committee of Secret Correspondence which operated from 1775 to 1776 for "the sole purpose of corresponding with our friends in Great Britain and other parts of the world". Through secret correspondence the Committee shared information and forged alliances with persons in France, England and throughout America. It employed secret agents in Europe to gather foreign intelligence, conduct undercover operations, analyze foreign publications, and initiate American propaganda campaigns to gain Patriot support.[97] Members included Thomas Paine, the committee's secretary, and Silas Deane who was instrumental in securing French aid in Paris.[98][ac]

Adams, Sherman, Livingston,

Jefferson, Franklin (l-r presenting)

Thomas Paine's pamphlet Common Sense boosted public support for independence throughout the thirteen colonies, and it was widely reprinted.[100] At the rejection of the Olive Branch Petition, Congress appointed the Committee of Five consisting of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston[101] to draft a Declaration of Independence to politically separate the United States from Britain. The document argued for government by consent of the governed on the authority of the people of the thirteen colonies as "one people", along with a long list indicting George III as violating English rights.[102] On July 2, Congress voted for independence, and it published the declaration on July 4[103] which George Washington read to assembled troops in New York City on July 9.[104] Later that evening a mob tore down a lead statue of the King, which was later melted down into musket balls.[105]

At this point, the American Revolution passed from its "colonial war" stage as thirteen colonies in Congress contesting the economic rules of empire with the Mother Country, to a second stage, one of civil war. The self-proclaimed states through their delegates assembled in Congress engaged in a military, political, and economic struggle against Great Britain. Politically and militarily, there were in every colony and county, a mix of Patriots (Whigs) and Loyalists (Tories) who now went to war against their neighbors.[106]

Patriots were those who supported independence from Britain in their states and a new national union in Congress. Loyalists remained faithful to British imperial rule. Loyalists were usually minorities in each population, the appointed colonial officials, licensed merchants, Anglican churchmen, and the politically traditional. They were concentrated around port cities, on the New England Iroquois frontier and in the South near Cherokee settlement.[107] Tories saw any subjects of the King who pretended to remove their ruler for whatever reasons as committing treason, and George III was encouraged to convict those responsible with the death penalty.[108]

War in America

As the American Revolutionary War was to unfold in North America, there were two principal campaign theaters within the thirteen states, and a smaller but strategically important one west of the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River and north to the Great Lakes. The full-on military campaigning began in the states north of Maryland, and fighting was most frequent and severest there between 1775 and 1778. Patriots achieved several strategic victories in the South, the British lost their first army at Saratoga, and the French entered the war as a US ally.

After wintering at Valley Forge, from the 1778 Battle of Monmouth, Washington stalemated British initiatives into a series of raids, containing the British army in New York City. In 1778, Spanish-supplied Virginia Col. George Rogers Clark, Francophone settlers and their Indian allies conquered Western Quebec, the US Northwest Territory. Starting in 1779, the British initiated a southern strategy to begin at Savannah, gather Loyalist support, and reoccupy Patriot-controlled territory north to the Chesapeake Bay. The Americans lost an army in their greatest defeat at Charleston in 1780. British maneuvering north led to a combined American and French force cornering a second British army at Battle of Yorktown, and their surrender effectively ended the Revolutionary War.[109]

Early engagements

Sir Thomas Gage, the British Commander-in-Chief in America 1763-1775 and sitting Governor of Massachusetts, gathered intelligence of a Patriot plan to destroy stores of militia ordnance at Concord. He set out to secure the stores there by way of Lexington to capture John Hancock and Samuel Adams, the two principal provocateurs of the rebellion. The operation was to commence before midnight while completing their objectives and retreating to Boston before multitudes of patriot militias could respond. However, the patriots had a good intelligence network of their own, which Paul Revere had helped organize. Subsequently, the Patriots learned of Gage's intentions before he could act, where Revere quickly dispatched this information and alerted Captain John Parker and the patriot forces in Concord.[110]

Fighting broke out during the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, when patriots fired the first shot forcing the British troops to conduct a fighting withdrawal to Boston. Overnight, the local militia converged on and laid siege to Boston.[111] On May 25, 4,500 British reinforcements arrived with generals William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton.[112] During the Battle of Bunker Hill the British seized the Charlestown Peninsula on June 17 with a frontal assault costing many officer casualties to American rifle snipers.[113] Surviving British commanders were dismayed at the costly attack which had gained them little,[114] and Gage appealed to London stressing the need for a large army to suppress the revolt.[115] Total British losses killed and wounded exceeded 1,000, leading Howe to replace Gage.[116]

Congressional leader John Adams of Massachusetts nominated Virginia delegate George Washington for commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in June 1775. He had previously commanded Virginia militia regiments in British combat commands during the French and Indian War.[117] Washington proceeded to Boston to assume field command of the ongoing Siege of Boston on July 3.[118] Howe made no effort to attack in a standoff with Washington,[119] who made no plan to assault the city.[120] Instead, the Americans fortified Dorchester Heights. In early March 1776, Colonel Henry Knox arrived with heavy artillery captured from a raid on Fort Ticonderoga.[121] Under cover of darkness Washington placed his artillery atop Dorchester Heights March 5,[122] threatening Boston and the British ships in the harbor. Howe did not want another battle like Gage's Bunker Hill, so he evacuated Boston. The British were permitted to withdraw without further casualties on March 17, and they sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia. Washington then moved his army south to New York.[123]

Beginning in August 1775, American Privateers had begun to raid villages in Nova Scotia, first at Saint John, then Charlottetown and Yarmouth. They continued in 1776 at Canso and then a land assault on Fort Cumberland.

Meanwhile, British officials in Quebec began negotiating with Indian tribes to support them,[124] while the Americans urged them to maintain neutrality.[125] In April 1775, Congress feared an Anglo-Indian attack from Canada and authorized an invasion of Quebec. Quebec had a largely Francophone population and had been under British rule for only 12 years.[126][ad] A Massachusetts sponsored uprising in Nova Scotia had been disbursed in November, but The Americans expected that they would welcome liberation from the British.[127] The second American expedition into the former French territory was defeated at the Battle of Quebec on December 31.[128] After a loose siege, the Americans withdrew on May 6, 1776.[129] An American failed counter-attack on June 8 ended their operations in Quebec.[130] However, British pursuit was blocked by American ships on Lake Champlain until they were cleared on October 11 at the Battle of Valcour Island. The American troops were forced to withdraw to Ticonderoga, ending the campaign. The invasion cost the Patriots their support in British public opinion,[131] and their aggressive anti-Loyalist policies had diluted Canadian support.[132] No further Patriot attempts to invade were subsequently made.[133]

In Virginia, Royal Governor Lord Dunmore had attempted to disarm the militia as tensions increased, although no fighting broke out.[134] He issued a proclamation on November 7, 1775, promising freedom for slaves who fled their Patriot masters to fight for the Crown.[135] Dunmore's troops were repulsed at the Battle of Great Bridge, and Dunmore fled to British ships anchored off the nearby port at Norfolk. The Third Virginia Convention refused to disband its militia or accept martial law. Speaker Peyton Randolph in the last Royal Virginia Assembly session did not make a response to Lord Dunmore concerning Parliament's Conciliatory Resolution. Negotiations failed in part because Randolph was also President of the Virginia Conventions, and he deferred to Congress, where he was also President. Dunmore ordered the ship's crews to burn Norfolk on January 1, 1776.[136]

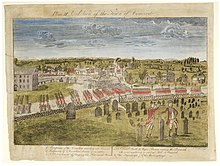

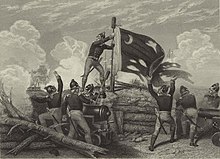

Battle of Sullivan's Island, June 1776

Fighting broke out on November 19 in South Carolina between Loyalist and Patriot militias,[137] and the Loyalists were subsequently driven out of the colony.[138] Loyalists were recruited in North Carolina to reassert colonial rule in the South, but they were decisively defeated and Loyalist sentiment was subdued.[139] A troop of British regulars set out to reconquer South Carolina and launched an attack on Charleston during the Battle of Sullivan's Island, on June 28, 1776,[140] but it failed and left the South in Patriot control until 1780.[141]

Shortages in Patriot gunpowder led Congress to authorize an expedition against the Bahamas colony in the British West Indies to secure additional ordnance there.[142] On March 3, 1776, the Americans landed and engaged the British at the Battle of Nassau, but the local militia offered no resistance.[143] The expedition confiscated what supplies they could and sailed for home on March 17.[144] The squadron reached New London, Connecticut, on April 8, after a brief skirmish during the Battle of Block Island with the Royal Navy frigate HMS Glasgow on April 6.[145]

British New York counter-offensive

After regrouping at Halifax, William Howe determined to take the fight to the Americans.[146] He set sail in June 1776 and began landing troops on Staten Island near the entrance to New York Harbor on July 2. The Americans rejected Howe's informal attempt to negotiate peace July 30.[147] Facing off against the British at New York City, Washington realized that he needed advance information to deal with disciplined British regular troops. On August 12, 1776, Thomas Knowlton was given orders to form an elite group for reconnaissance and secret missions. Knowlton's Rangers became the Army's first intelligence unit.[148]

When Washington split his army to positions on Manhattan Island and across the East River in western Long Island,[149] on August 27 at the Battle of Long Island Howe outflanked Washington and forced him back to Brooklyn Heights, but he did not attempt to encircle Washington's forces.[150] Through the night of August 28, General Henry Knox bombarded the British. On August 29, an American council of war all agreed to retreat to Manhattan. Washington quickly had his troops assembled and ferried them across the East River to Manhattan on flat-bottomed freight boats without any losses in men or ordnance, with General Thomas Mifflin's regiments in the rear guard.[151]

The Staten Island Peace Conference failed to negotiate peace as the British delegates did not have authority to recognize independence to meet the rebel demands.[152] Howe seized control of New York City on September 15 and unsuccessfully engaged the Americans the following day.[153] He failed to encircle the Americans at the Battle of Pell's Point, then the Americans successfully withdrew. Howe declined to close with Washington's army on October 28 at the Battle of White Plains, but instead concentrated his efforts on a hill that was of no strategic value.[154]

Washington's retreat had left his remaining forces isolated, and the British captured their Fort Washington on November 16. The British victory there took 3,000 prisoners and amounted to Washington's most disastrous defeat.[155] Washington's remaining army on Long Island fell back four days later.[156] Henry Clinton wanted to pursue Washington's disorganized army, but he was required to commit 6,000 troops to first capture Newport, Rhode Island in an operation that he had opposed.[157] The American prisoners were subsequently sent to the infamous prison ships where more American soldiers and sailors died of disease and neglect than died in every battle of the war combined.[158] Charles Cornwallis pursued Washington, but Howe ordered him to halt and Washington marched away unmolested.[159]

The outlook was bleak for the American cause; the reduced army had dwindled to fewer than 5,000 men and that number would be reduced further when enlistments expired at the end of the year.[160] Popular support wavered, morale ebbed away, and Congress abandoned Philadelphia.[161] Loyalist activity surged in the wake of the American defeat, especially in New York.[162] Once Washington was driven out of New York, he realized that he would need more than military might and amateur spies to defeat the British and earnestly made efforts to professionalize military intelligence with the aid of Benjamin Tallmadge. They created the Culper spy ring of six men.[ae]

News of the campaign was well received in Britain with festivities held in London, public support reached a peak,[164] and the King awarded the Order of the Bath to Howe. The successes led to predictions that the British could win within a year.[165] Strategic deficiencies among Patriot forces were evident by Washington's dividing a numerically weaker army in the face of a stronger one, inexperienced staff misreading the situation, and their troops fleeing in the face of enemy fire.[166] In the meantime, the British entered winter quarters and were in a good place to resume campaigning.[167]

On the night of December 25–26, 1776, Washington crossed the ice-choked Delaware River and surprised and overwhelmed Colonel Johann Rall and the Hessian garrison at Trenton, New Jersey, and taking 900 prisoners.[168][af] The decisive victory rescued the army's flagging morale, dispelled much of the fear for professional Hessian "mercenaries"[170] and gave a new hope to the Patriot cause.[171] Cornwallis marched to retake Trenton, but his efforts were repulsed in the Battle of the Assunpink Creek on January 2.[172] Washington outmaneuvered Cornwallis that night and defeated his rearguard the following day. The two victories contributed to convincing the French that the Americans were worthwhile allies.[173] Washington entered winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey on January 6,[174] though a prolonged guerrilla conflict continued.[175] Howe made no attempt to attack, much to Washington's amazement.[176]

British northern strategy fails

In December 1776, John Burgoyne returned to London to set strategy with Lord George Germain. Burgoyne's plan was to isolate New England by establishing control of the Great Lakes from New York to Quebec. Efforts could then concentrate on the southern colonies, where it was believed that Loyalist support was widespread and substantial.[177]

Burgoyne's plan was to maneuver two armies by different routes and rendezvous at Albany, New York.[178] Burgoyne set out along Lake Champlain on June 14, 1777, quickly capturing Ticonderoga on July 5. From there the pace slowed. The Americans blocked roads, destroyed bridges, dammed streams, and stripped the area of food.[179] Meanwhile, Barry St. Ledger's diversionary column along the Mohawk River laid siege to Fort Stanwix. St. Ledger withdrew to Quebec on August 22 after his Indian support abandoned him. On August 16, a Brunswick foraging expedition was soundly defeated at Bennington, and more than 700 troops were captured.[180] The vast majority of Burgoyne's Indian support then abandoned him in the field, but Lord Howe informed him that he would still launch their planned campaign on Philadelphia, but without his support from New York.[181]

Burgoyne continued the advance, and he attempted to flank the American position at Freeman's Farm on September 19 in the First Battle of Saratoga. The British won, but at the cost of 600 casualties. Burgoyne then dug in, but he suffered a constant hemorrhage of deserters, and critical supplies ran low.[182] The Americans repulsed a British reconnaissance in force against the American lines on October 7, with heavy British losses during the second Battle of Saratoga. Burgoyne then withdrew in the face of American pursuit, but he was surrounded by October 13. With supplies exhausted and no hope of relief, Burgoyne surrendered his army on October 17, and the Americans took 6,222 soldiers as prisoners of war.[183]

Meanwhile, Howe took command of a New York-based campaign against Washington. Early feints failed to bring Washington to battle in June 1777.[184] Howe then declined to attack towards Philadelphia further, either overland via New Jersey or by sea via the Delaware Bay, leaving Burgoyne's initiative launched from the interior unsupported.

Later in the fall with additional supplies, Howe recommenced the Philadelphia campaign. This time on advancing, he outflanked and defeated Washington on September 11, but failed to pursue and destroy the defeated Americans on two occasions; once after the Battle of Brandywine,[185] and again after the Battle of Germantown.[186] A British victory at Willistown left Philadelphia defenseless, and Howe captured the city unopposed on September 26. He then moved 9,000 men to Germantown north of Philadelphia.[187] Washington launched a surprise attack there on Howe's garrison on October 4, but he was eventually repulsed.[188] Once again, Howe did not follow up on his victory.[189]

"Model Infantry" at Valley Forge

Howe, surprised by the American defenses, inexplicably ordered a retreat to Philadelphia after several days of probing at the Battle of White Marsh.[190] He ignored the vulnerable American rear, where an attack might possibly have deprived Washington of his baggage and supplies.[191] On December 19, Washington's army entered winter quarters at Valley Forge. Poor conditions and supply problems there resulted in the deaths of some 2,500 American troops.[192] During Washington's winter encampment at Valley Forge, Baron von Steuben, introduced the latest Prussian methods of drilling and infantry tactics to the entire Continental Army.[193]

While the Americans wintered only twenty miles away, Howe made no effort to attack their camp, which some critics argue could have ended the war.[194] Following the conclusion of the campaign, Howe resigned his commission, and was replaced by Henry Clinton on May 24, 1778.[195] Clinton received orders to abandon Philadelphia and fortify New York following France's entry into the war. On June 18, the British departed Philadelphia, with the reinvigorated Americans in pursuit.[196] The two armies fought at Monmouth Court House on June 28, with the Americans holding the field, greatly boosting Patriot morale and confidence.[197] By July, both armies were back in the same positions they had been two years prior.

Foreign intervention

Early in the war, it became clear to Congress that help from France was imperative. First, the British instituted a blockade on the Atlantic seacoast ports against military assistance that could not be challenged. Second, its army troop strength attrited by death, disease and desertion, and the states failed to meet recruitment quotas. Third, the British had a continuing resupply of German auxiliaries to compensate for their losses.[198]

French foreign minister the Comte de Vergennes was strongly anti-British,[199] and he had long sought a pretext for going to war with Britain since the conquest of Canada in 1763.[200] The French public favored war, but Vergennes and King Louis XVI were hesitant, owing to the military and financial risk.[201]

France, however, would not feel compelled to intervene if the colonies were still considering reconciliation with Britain, as France would have nothing to gain in that event.[202] To assure assistance from France, independence would have to be declared, which was effected by Congress in July 1776.[203] The Americans who had been covertly supplied by French merchants through neutral Dutch ports since the onset of the war, were now also supplied directly by the French government.[204] These proved invaluable in the American 1777 Saratoga campaign.[205]

The British defeat at Saratoga caused British anxiety over possible foreign intervention. The North ministry sought reconciliation with the colonies by consenting to their original demands, but without independence.[206] However the Americans were now bolstered by their French trade, and would settle for no terms short of complete independence from Britain.[207] The American victory at Saratoga convinced the French that supporting the Patriots was worthwhile,[208] but doing so too late brought major concerns. King Louis XVI feared that Britain's concessions would be accepted and bring reconciliation with the Colonies. Britain would then be free to strike at French Caribbean possessions.[209] To prevent this, France formally recognized the United States in a trade treaty on February 6, 1778, and followed that with a defensive military alliance guaranteeing American independence.[210][ag] Spain was wary of recognizing a republic of former European colonies, and also of provoking war with Britain before it was well prepared. It opted to covertly supply the Patriots mainly from Havana in Cuba and New Orleans in Spanish Louisiana.[212]

To encourage French participation in the American struggle for independence, diplomat Silas Deane promised promotions and command positions to any French officer who joined the American war effort. However, many of the French officer-adventurers were completely unfit for command. In one outstanding exception, Congress recognized Lafayette's "great zeal to the cause of liberty" and commissioned him a major General. He was immediately instrumental in reconciling some of Washington's rival officers and he aligned some of the delegates in Philadelphia to support Washington in an otherwise indifferent Congress.[213]

Congress also hoped to persuade Spain into an open alliance, as formally extended in the French treaty. The American Commissioners met with the Count of Aranda in 1776.[214] But Spain was still reluctant to make an early commitment due to its Great Power concerns on the Continent.[215] Nevertheless, the following year, Spain affirmed its desire to support the Americans so as to weaken Britain's empire.[216][ah]

Since the outbreak of the conflict, Britain had appealed to its former ally, the neutral Dutch Republic, to lend the use of the Scots Brigade for service in America. But pro-American sentiment there forced its elected representatives to deny the request.[218] Consequently, the British attempted to invoke treaties for outright Dutch military support, but the Republic still refused. At the same time, American troops were being supplied with ordnance by Dutch merchants via their West Indies colonies.[219] French supplies bound for America were also transshipped through Dutch ports.[220] The Republic traded with France following France's declaration of war on Britain, citing a prior concession by Britain on this issue. But despite standing international agreements, Britain responded by confiscating Dutch shipping, and even firing upon it. The Republic joined the First League of Armed Neutrality with Austria, Prussia and Russia to enforce their neutral status.[221] But The Republic had further assisted the rebelling Patriot cause. It had also given sanctuary to American privateers[222] and had drafted a treaty of commerce with the Americans. Britain argued that these actions contravened the Republic's neutral stance and declared war in December 1780.[223]

Meanwhile, George III had given up on subduing America while Britain had a European war to fight.[224] He did not welcome war with France, but he believed that Britain had made all necessary steps to avoid it and cited the British victories over France in the Seven Years' War as a reason to remain optimistic in the event of war with France.[225] Britain tried in vain to find a powerful ally to engage France. It was isolated among the Great Powers, and French strength was not drawn off into Europe as in the Seven Years' War.[226] Britain subsequently changed its focus from one theater,[227] and diverted major military resources away from America.[228] Despite these developments, George III still determined never to recognize American independence and to make war on the American colonies indefinitely, or until they pleaded to return as his subjects.[229][ai]

Stalemate in the North

Following the British defeat at Saratoga in October, 1777, and French entry into the war, Clinton withdrew from Philadelphia to consolidate his forces in New York.[231] French admiral the Comte d'Estaing had been dispatched to America in April 1778 to assist Washington. The Franco-American forces felt that New York's defenses were too formidable for the French fleet, so in August 1778 they launched an attack on Newport at the Battle of Rhode Island under the command of General John Sullivan.[232] The effort failed when the French opted to withdraw, disappointing the Americans.[233] The war then stalemated. Most actions were fought as large skirmishes such as those at Chestnut Neck and Little Egg Harbor. In the summer of 1779, the Americans captured British posts at the Battles of Stony Point and Paulus Hook.[234] In July, Clinton unsuccessfully attempted to coax Washington into a decisive engagement by making a major raid into Connecticut.[235] That month, a large American naval operation attempted to retake Maine, but it resulted in a humiliating defeat.[236] The high frequency of Iroquois raids compelled Washington to mount a punitive expedition which destroyed a large number of Iroquois settlements, but the effort ultimately failed to stop the raids.[237] During the winter of 1779–80, the Continental Army suffered greater hardships than at Valley Forge.[238] Morale was poor, public support fell away in the long war, the national currency was virtually worthless, the army was plagued with supply problems, desertion was common, and whole regiments mutinied over the conditions in early 1780.[239]

In 1780, Clinton launched an attempt to retake New Jersey. On June 7, 6,000 men invaded under Hessian general Wilhelm von Knyphausen, but they met stiff resistance from the local militia at the Battle of Connecticut Farms. The British held the field, but Knyphausen feared a general engagement with Washington's main army and withdrew.[240] A second attempt two weeks later was soundly defeated at Springfield, effectively ending British ambitions in New Jersey.[241] Meanwhile, American general Benedict Arnold turned traitor, joined the British army and attempted to surrender the American West Point fortress. The plot was foiled when British spy-master John André was captured. Arnold fled to British lines in New York where he justified his betrayal by appealing to Loyalist public opinion, but the Patriots strongly condemned him as a coward and turncoat.[242]