Cheetah: Difference between revisions

BhagyaMani (talk | contribs) →Speed and acceleration: edited refs, rem ref to news |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Large feline of the genus Acinonyx}} |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

{{ |

{{About|the animal||Cheetah (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{ |

{{Pp|small=yes}} |

||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=April 2016}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} |

|||

{{Automatic taxobox |

|||

{{Use British English|date=May 2020}} |

|||

| taxon = Acinonyx jubatus |

|||

{{Speciesbox |

|||

| name = Cheetah |

| name = Cheetah |

||

| fossil_range = [[Pleistocene]] |

| fossil_range = [[Pleistocene]]–Present |

||

| status = VU |

| status = VU |

||

| status_system = IUCN3.1 |

|||

| trend = down |

|||

| status_ref = <ref name=iucn>{{cite iucn |author=Durant, S.M. |author2=Groom, R. |author3=Ipavec, A. |author4=Mitchell, N. |author5=Khalatbari, L. |year=2022 |title=''Acinonyx jubatus'' |page=e.T219A124366642 |doi=10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T219A124366642.en}}</ref> |

|||

| status_system = iucn3.1 |

|||

| status2 = CITES_A1 |

|||

| status_ref =<ref name=iucn>{{cite journal | authors = Durant, S.; Mitchell, N.; Ipavec, A.; Groom, R. | title = ''Acinonyx jubatus'' | journal = [[IUCN Red List of Threatened Species]] | volume= 2015 | page = e.T219A50649567 | publisher = [[IUCN]] | year = 2015 | url = http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T219A50649567.en | accessdate = 30 May 2016}}</ref> |

|||

| status2_system = CITES |

|||

| image = Cheetah Umfolozi SouthAfrica MWegmann.jpg |

|||

| status2_ref = <ref name=iucn/> |

|||

| image_caption = A [[South African cheetah]]<br>(''A. jubatus jubatus'') |

|||

| image = Male cheetah facing left in South Africa.jpg |

|||

| binomial = ''Acinonyx jubatus'' |

|||

| image_caption = Male cheetah, in [[South Africa]] |

|||

| binomial_authority = ([[Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber|Schreber]], 1775) |

|||

| image_alt = Male cheetah, in [[South Africa]] |

|||

| taxon = Acinonyx jubatus |

|||

| authority = ([[Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber|Schreber]], 1775) |

|||

| subdivision_ranks = Subspecies |

| subdivision_ranks = Subspecies |

||

| subdivision = |

| subdivision = {{collapsible list |

||

|[[Southeast African cheetah]] (''A. j. jubatus'') {{small|(Schreber, 1775)}} |

|||

|[[Asiatic cheetah]] (''A. j. venaticus'') {{small|([[Edward Griffith (zoologist)|Griffith]], 1821)}} |

|||

|[[Northeast African cheetah]] (''A. j. soemmeringii'') {{small|([[Leopold Fitzinger|Fitzinger]], 1855)}} |

|||

|[[Northwest African cheetah]] (''A. j. hecki'') {{small|([[:de:Max Hilzheimer|Hilzheimer]], 1913)}} |

|||

*[[Tanzanian cheetah|''A. j. raineyii'']] <small>[[Edmund Heller|Heller]], 1913</small> |

|||

| synonyms_ref = |

|||

| synonyms = {{collapsible list|title=<small>List</small><ref name=mammal/> |

|||

|''Acinonyx venator'' <small>[[Joshua Brookes|Brookes]], 1828</small> |

|||

|''Cynælurus jubata'' <small>[[St George Jackson Mivart|Mivart]], 1900</small> |

|||

|''C. jubatus'' <small>[[William Thomas Blanford|Blanford]], 1888</small> |

|||

|''C. guttatus'' <small>[[Ned Hollister|Hollister]], 1911</small> |

|||

|''Felis guttata'' <small>[[Johann Hermann|Hermann]], 1804</small> |

|||

|''F. fearonii'' <small>[[Andrew Smith (zoologist)|Smith]], 1834</small> |

|||

|''F. jubata'' <small>Erxleben, 1777</small> |

|||

|''F. jubatus'' <small>Schreber, 1775</small> |

|||

|''F. megaballa'' <small>Heuglin, 1868</small> |

|||

|''F. venatica'' <small>[[Edward Griffith (zoologist)|Griffith]], 1821</small> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| synonyms_ref = <ref name=mammal/> |

|||

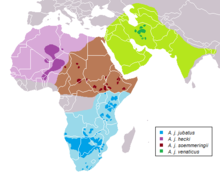

| range_map = Cheetah_range.gif |

|||

| synonyms = {{collapsible list |

|||

| range_map_caption = The range of the cheetah |

|||

|''Acinonyx venator'' {{small|[[Joshua Brookes|Brookes]], 1828}} |

|||

|''A. guepard'' {{small|Hilzheimer, 1913}} |

|||

|''A. rex'' {{small|[[Reginald Innes Pocock|Pocock]], 1927}} |

|||

|''A. wagneri'' {{small|Hilzheimer, 1913}} |

|||

|''Cynaelurus guttatus'' {{small|[[St. George Jackson Mivart|Mivart]], 1900}} |

|||

|''Cynaelurus jubata'' {{small|Mivart, 1900}} |

|||

|''Cynaelurus lanea'' {{small|[[Theodor von Heuglin|Heuglin]], 1861}} |

|||

|''Cynailurus jubatus'' {{small|[[Johann Georg Wagler|Wagler]], 1830}} |

|||

|''Cynailurus soemmeringii'' {{small|Fitzinger, 1855}} |

|||

|''Cynofelis guttata'' {{small|[[René Lesson|Lesson]], 1842}} |

|||

|''Cynofelis jubata'' {{small|Lesson, 1842}} |

|||

|''Felis fearonii'' {{small|[[Andrew Smith (zoologist)|Smith]], 1834}} |

|||

|''F. fearonis'' {{small|Fitzinger, 1855}} |

|||

|''F. megabalica'' {{small|Heuglin, 1863}} |

|||

|''F. megaballa'' {{small|Heuglin, 1868}} |

|||

|''Guepar jubatus'' {{small|[[Pierre Boitard|Boitard]], 1842}} |

|||

|''Gueparda guttata'' {{small|[[John Edward Gray|Gray]], 1867}} |

|||

|''Guepardus guttata'' {{small|[[Georges Louis Duvernoy|Duvernoy]], 1834}} |

|||

|''Guepardus jubatus'' {{small|Duvernoy, 1834}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| range_map = Acinonyx jubatus subspecies range IUCN 2015 (cropped).png |

|||

| range_map_caption = The range of the cheetah as of 2015<ref name=iucn /> |

|||

| range_map_alt = Map showing the distribution of the cheetah in 2015 |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''cheetah''' ('''''Acinonyx jubatus''''') is a large [[Felidae|cat]] and the [[Fastest animals|fastest]] land animal. It has a tawny to creamy white or pale buff fur that is marked with evenly spaced, solid black spots. The head is small and rounded, with a short [[snout]] and black tear-like facial streaks. It reaches {{cvt|67–94|cm}} at the shoulder, and the head-and-body length is between {{cvt|1.1|and|1.5|m}}. Adults weigh between {{cvt|21|and|72|kg}}. The cheetah is capable of running at {{cvt|93|to|104|km/h}}; it has evolved specialized adaptations for speed, including a light build, long thin legs and a long tail. |

|||

The '''cheetah''' ({{IPA-en|ˈtʃi-tə|pron}}) (''Acinonyx jubatus''), also known as the '''hunting leopard''', is a [[big cat]] that occurs mainly in eastern and southern Africa and a few parts of [[Iran]]. The only [[extant taxon|extant member]] of the [[Genus (biology)|genus]] ''[[Acinonyx]]'', the cheetah was first [[scientific description|described]] by [[Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber]] in 1775. The cheetah is characterised by a slender body, deep chest, spotted [[Coat (animal)|coat]], a small rounded head, black tear-like streaks on the face, long thin legs and a long spotted tail. Its lightly built, slender form is in sharp contrast with the robust build of the other [[big cat]]s. The cheetah reaches nearly {{convert|70|to|90|cm|in|abbr=on}} at the shoulder, and weighs {{convert|21|-|72|kg|abbr=on}}. Though taller than the [[leopard]], it is notably smaller than the [[lion]]. Basically yellowish tan or rufous to greyish white, the coat is uniformly covered with nearly 2,000 solid black spots. |

|||

The cheetah was first [[Species description|described]] in the late 18th century. Four subspecies are recognised today that are native to [[Africa]] and central [[Iran]]. An African subspecies was [[Cheetah reintroduction in India|introduced to India]] in 2022. It is now distributed mainly in small, fragmented populations in northwestern, [[East Africa|eastern]] and [[southern Africa]] and central Iran. It lives in a variety of habitats such as [[savannah]]s in the [[Serengeti]], arid mountain ranges in the [[Sahara]], and hilly desert terrain. |

|||

Cheetah are active mainly during the day, with hunting its major activity. Adult males are sociable despite their [[Territory (animal)|territoriality]], forming groups called "coalitions". Females are not territorial; they may be solitary or live with their offspring in [[home range]]s. [[Carnivore]]s, cheetah mainly prey upon [[antelope]]s and [[gazelle]]s. They will stalk their prey to within {{convert|100|–|300|m|ft|-1}}, charge towards it and kill it by tripping it during the chase and biting its throat to suffocate it to death. The cheetah's body is specialised for speed; it is the [[Fastest animals|fastest]] land animal. The speed of a hunting cheetah averages {{convert|64|km/h|mph|abbr=on}} during a sprint; the chase is interspersed with a few short bursts of speed, when the animal can clock {{convert|112|km/h|mph|abbr=on}}. Cheetahs are [[Induced ovulation (animals)|induced ovulator]]s, breeding throughout the year. [[Gestation]] is nearly three months long, resulting in a litter of typically three to five cubs (the number can vary from one to eight). Weaning occurs at six months; siblings tend to stay together for some time. Cheetah cubs face higher mortality than most other mammals, especially in the [[Serengeti]] region. Cheetahs inhabit a variety of habitats{{snds}}dry forests, [[scrub forest]]s and [[savanna]]hs. |

|||

The cheetah lives in three main [[sociality|social group]]s: females and their cubs, male "coalitions", and solitary males. While females lead a nomadic life searching for prey in large [[home range]]s, males are more sedentary and instead establish much smaller [[Territory (animal)|territories]] in areas with plentiful prey and access to females. The cheetah is active during the day, with peaks during dawn and dusk. It feeds on small- to medium-sized prey, mostly weighing under {{cvt|40|kg}}, and prefers medium-sized [[ungulate]]s such as [[impala]], [[springbok]] and [[Thomson's gazelle]]s. The cheetah typically stalks its prey within {{cvt|60|-|100|m}} before charging towards it, trips it during the chase and bites its throat to suffocate it to death. It breeds throughout the year. After a [[gestation]] of nearly three months, females give birth to a litter of three or four cubs. Cheetah cubs are highly vulnerable to predation by other large carnivores. They are weaned at around four months and are independent by around 20 months of age. |

|||

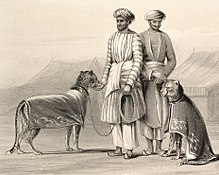

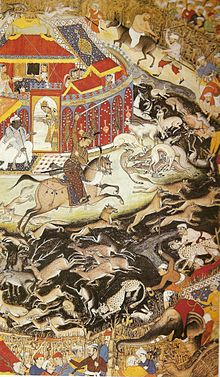

Classified as [[Vulnerable species|vulnerable]] by the [[IUCN]], the cheetah has suffered a substantial decline in its historic range due to rampant hunting in the 20th century. Several African countries have taken steps to improve the standards of cheetah conservation. Thanks to its prowess at hunting, the cheetah was tamed and used to kill game at hunts in the past. The animal has been widely depicted in art, literature, advertising and animation. |

|||

The cheetah is threatened by [[habitat loss]], conflict with humans, [[poaching]] and high susceptibility to diseases. The global cheetah population was estimated in 2021 at 6,517; it is listed as [[Vulnerable species|Vulnerable]] on the [[IUCN Red List]]. It has been widely depicted in art, literature, advertising, and animation. It was [[Taming|tamed]] in [[ancient Egypt]] and trained for hunting ungulates in the [[Arabian Peninsula]] and India. It has been kept in [[zoo]]s since the early 19th century. |

|||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

The vernacular name "cheetah" is derived from [[Hindustani language|Hindustani]] {{lang-ur|چیتا}} and {{lang-hi|चीता}} ({{lang|hi-Latn|ćītā}}).<ref>{{cite book |last=Platts |first=J. T. |author-link=John Thompson Platts |year=1884 |title=A Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi, and English |location=London |publisher=[[W. H. Allen & Co.]] |chapter=چيتا चीता ćītā |page=470 |chapter-url=https://dsal.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/app/platts_query.py?qs=%DA%86%D9%8A%D8%AA%D8%A7&searchhws=yes&matchtype=exact |access-date=27 September 2022 |archive-date=27 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220927104057/https://dsal.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/app/platts_query.py?qs=%DA%86%D9%8A%D8%AA%D8%A7&searchhws=yes&matchtype=exact |url-status=live}}</ref> This in turn comes from {{lang-sa|चित्रय}} ({{lang|sa-Latn|Chitra-ya}}) meaning 'variegated', 'adorned' or 'painted'.<ref>{{cite book |last=Macdonell |first=A. A. |author-link=Arthur Anthony Macdonell |year=1929 |title=A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary with Transliteration, Accentuation, and Etymological Analysis throughout |location=London |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |chapter=चित्रय kitra-ya |page=68 |chapter-url=https://dsalsrv04.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/app/macdonell_query.py?qs=%E0%A4%9A%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%AF&searchhws=yes |access-date=5 April 2019 |archive-date=2 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200702082049/https://dsalsrv04.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/app/macdonell_query.py?qs=%E0%A4%9A%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%AF&searchhws=yes |url-status=dead}}</ref> In the past, the cheetah was often called "hunting leopard" because they could be tamed and used for [[coursing]].<ref name=marker1>{{cite book |editor1=Marker, L. |editor2=Boast, L. K. |editor3=Schmidt-Kuentzel, A. |title=Cheetahs: Biology and Conservation |date=2018 |publisher=[[Academic Press]] |location=London |isbn=978-0-12-804088-1 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H3rXDgAAQBAJ&pg=3 |chapter=A brief history of cheetah conservation |last1=Marker |first1=L. |last2=Grisham |first2=J. |last3=Brewer |first3=B. |name-list-style=amp |pages=3–16 |access-date=25 April 2020 |archive-date=7 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220407160709/https://books.google.com/books?id=H3rXDgAAQBAJ&pg=3 |url-status=live}}</ref> The [[generic name (biology)|generic name]] ''Acinonyx'' probably derives from the combination of two [[Greek language|Greek]] words: {{lang|el|ἁκινητος}} ({{lang|el-Latn|akinitos}}) meaning 'unmoved' or 'motionless', and {{lang|el|ὄνυξ}} ({{lang|el-Latn|onyx}}) meaning 'nail' or 'hoof'.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Liddell |first1=H. G. | author1-link=Henry Liddell |last2=Scott |first2=R. |author2-link=Robert Scott (philologist) |name-list-style=amp |year=1889 |title=An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon |location=Oxford |publisher=[[Clarendon Press]] |pages=27, 560 |chapter=ἁκινητος |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/intermediategree00lidd/page/n32}}</ref> A rough translation is "immobile nails", a reference to the cheetah's limited ability to retract its claws.<ref name=Rosevear1974>{{cite book |title=The Carnivores of West Africa |last=Rosevear |first=D. R. |year=1974 |publisher=[[Natural History Museum, London|Natural History Museum]] |location=London |isbn=978-0-565-00723-2 |pages=492–512 |chapter=Genus ''Acinonyx'' Brookes, 1828 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/carnivoresofwest00rose#page/492/mode/1up}}</ref> A similar meaning can be obtained by the combination of the Greek prefix ''a–'' (implying a lack of) and {{lang|el|κῑνέω}} ({{lang|el-Latn|kīnéō}}) meaning 'to move' or 'to set in motion'.<ref name="skinner">{{cite book |last1=Skinner |first1=J. D. |last2=Chimimba |first2=C. T. |name-list-style=amp |title=The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion |date=2005 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |location=New York |isbn=978-0521844185 |edition=3rd |chapter=Subfamily Acinonychinae Pocock 1917 |pages=379–384 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F23lAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA379 |access-date=5 January 2020 |archive-date=28 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328013025/https://books.google.com/books?id=F23lAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA379 |url-status=live}}</ref> The [[Specific name (zoology)|specific name]] {{lang|la|jubatus}} is [[Latin]] for 'crested, having a mane'.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=C. T. |author1-link=Charlton Thomas Lewis |last2=Short |first2=C. |name-list-style=amp |year=1879 |title=A Latin Dictionary |location=Oxford |publisher=Clarendon Press |chapter=jubatus |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.61236/page/n1033 |page=1014}}</ref> |

|||

The vernacular name "cheetah" ({{IPA-en|ˈchē-tə|pron}}) is derived from the [[Hindi]] word चीता (''cītā''), which in turn comes from the [[Sanskrit]] word चित्रकायः (''{{IAST|citrakāyaḥ}}'') meaning "bright" or "[[Variegation|variegated]]". The first recorded use of this word was in 1610.<ref>{{MerriamWebsterDictionary|Cheetah|accessdate=12 February 2016}}</ref><ref>{{Oxford Dictionaries|Cheetah|accessdate=22 March 2016}}</ref> An alternative name for the cheetah is "hunting leopard".<ref name=mair/> The [[scientific name]] of the cheetah is ''Acinonyx jubatus''.<ref name=MSW3/> The [[generic name (biology)|generic name]] ''Acinonyx'' could have originated from the combination of three [[Greek language|Greek]] words: ''a'' means "not", ''kaina'' means thorn, and ''onus'' means [[claw]]. A rough translation of the word would be "non-moving claws", a reference to the limited retractability (capability of being drawn inside) of the claws of the cheetah. The [[specific name (zoology)|specific name]] ''jubatus'' means "maned" in [[Latin]], referring to the [[Dorsal (location)|dorsal]] crest of this animal.<ref name=catsg>{{cite web |title = ''Acinonyx jubatus'' |url = http://www.catsg.org/cheetah/01_information/1_2_species-information/species-information.htm#Phylogenetic%20history |publisher = [[IUCN]] Cat Specialist Group |accessdate = 6 May 2014 }}</ref> |

|||

A few old generic names such as ''Cynailurus'' and ''Cynofelis'' allude to the similarities between the cheetah and [[canid]]s.<ref name="marker7">{{cite book |title=Cheetahs: Biology and Conservation |editor1=Marker, L. |editor2=Boast, L. K. |editor3=Schmidt-Kuentzel, A. |last1=Meachen |first1=J. |last2=Schmidt-Kuntzel |first2=A. |last3=Haefele |first3=H. |last4=Steenkamp |first4=G. |last5=Robinson |first5=J. M. |last6=Randau |first6=M. A. |last7=McGowan |first7=N. |last8=Scantlebury |first8=D. M. |last9=Marks |first9=N. |name-list-style=amp |last10=Maule |first10=A. |last11=Marker |first11=L. |date=2018 |publisher=Academic Press |isbn=978-0-12-804088-1 |location=London |pages=93–106 |chapter=Cheetah specialization: physiology and morphology |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H3rXDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA93 |access-date=26 March 2023 |archive-date=28 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328013046/https://books.google.com/books?id=H3rXDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA93 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==Taxonomy== |

==Taxonomy== |

||

{{cladogram|align=left|title= |

|||

|caption=The ''Puma'' lineage, depicted along with the ''Lynx'' and ''Felis'' lineages of the family [[Felid]]ae<ref name="werdelin" /><ref name="Mattern and McLennan"/> |

|||

|1={{clade | style=font-size:90%;line-height:100%;width:300px; |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|label1=''[[Lynx (genus)|Lynx]]'' |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1= {{clade |

|||

|1=''Lynx rufus'' ([[Bobcat]]) |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''L. canadensis'' ([[Canadian lynx]]) |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''L. pardinus'' ([[Iberian lynx]]) |

|||

|2=''L. lynx'' ([[Eurasian lynx]]) |

|||

}}}}}} |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|label1=''[[Puma (genus)|Puma]]'' |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1= ''Acinonyx jubatus'' (Cheetah) |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''Puma concolor'' ([[Cougar]]) |

|||

|2=''P. yagouaroundi'' ([[Jaguarundi]])}}}} |

|||

|label2=''[[Felis]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''Felis chaus'' ([[Jungle cat]]) |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''F. nigripes'' ([[Black-footed cat]]) |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''F. silvestris silvestris'' ([[European wildcat]]) |

|||

|2=''F. margarita'' ([[Sand cat]]) |

|||

|3={{clade |

|||

|1=''F. silvestris lybica'' ([[African wildcat]]) |

|||

|2=''F. catus'' ([[Domestic cat]]) |

|||

}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}} |

|||

The cheetah is the only extant [[species]] of the [[Genus (biology)|genus]] ''[[Acinonyx]]''. It is classified under the [[subfamily]] [[Felinae]] and [[family (biology)|family]] [[Felidae]], the family that also includes large cats such as the [[lion]], [[tiger]] and [[leopard]]. The species was first [[scientific description|described]] by German naturalist [[Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber]] in his 1775 publication ''Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen''.<ref name=MSW3>{{MSW3 Wozencraft |id=14000006 |pages=532-533}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Felisjubatus.jpg|thumb|An illustration of the "woolly cheetah" (described as ''Felis lanea'') from the ''[[Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London]]'' (1877)|alt=Illustration of the woolly cheetah (Felis lanea) published in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London in 1877]] |

|||

The cheetah's closest relatives are the [[cougar]] (''Puma concolor'') and the [[jaguarundi]] (''P.{{nbsp}}yagouaroundi''). These three species together form the ''Puma'' lineage, one of the eight lineages of Felidae.<ref name="werdelin">{{cite book|last1=Werdelin|first1=L.|last2=Yamaguchi|first2=N.|last3=Johnson|first3=W.E.|last4=O'Brien|first4=S.J.|chapter=Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)|date=2010|pages=59–82|url=https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nobuyuki_Yamaguchi3/publication/266755142_Phylogeny_and_evolution_of_cats_Felidae/links/543ba0710cf2d6698be30c5e.pdf|editor1-last=Macdonald|editor1-first=D.W.|editor2-last=Loveridge|editor2-first=A.J.|title=Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, UK|isbn=978-0-19-923445-5|edition=Reprinted}}</ref><ref name=johnson>{{cite journal |pmid = 9071018 |year = 1997 |last1 = Johnson |first1 = W.E. |last2 = O'Brien |first2 = S.J. |title = Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Felidae using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 mitochondrial genes |volume = 44 Suppl. 1 |pages = S98–S116 |journal = [[Journal of Molecular Evolution]] |doi = 10.1007/PL00000060 }}</ref><ref name="wcw">{{cite book |last1 = Sunquist |first1 = F. |last2 = Sunquist |first2 = M. |title = Wild Cats of the World |date = 2002 |publisher = The University of Chicago Press |location = Chicago, USA |isbn = 978-0-226-77999-7 |pages = 14–36 }}</ref> The [[sister group]] of the ''Puma'' lineage is a clade of smaller Old World cats that includes the genera ''[[Felis]]'', ''[[Otocolobus]]'' and ''[[Prionailurus]]''.<ref name="Mattern and McLennan"/><ref name=heptner/> |

|||

In 1777, [[Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber]] described the cheetah based on a skin from the [[Cape of Good Hope]] and gave it the [[Biological nomenclature|scientific name]] ''Felis jubatus''.<ref>{{cite book |last=Schreber |first=J. C. D. |author-link=Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber |year=1777 |chapter=Der Gepard (The cheetah) |title=Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen |volume=Dritter Theil |trans-title=The Mammals in Illustrations according to Nature with Descriptions |publisher=Wolfgang Walther |location=Erlangen |pages=392–393 |chapter-url=https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/schreber1875textbd3/0112/image |language=de |access-date=19 February 2019 |archive-date=28 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328013046/https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/schreber1875textbd3/0112/image |url-status=live}}</ref> [[Joshua Brookes]] proposed the [[Genus (biology)|generic]] name ''Acinonyx'' in 1828.<ref>{{cite book |last=Brookes |first=J. |author-link=Joshua Brookes |year=1828 |title=A Catalogue of the Anatomical and Zoological Museum of Joshua Brookes |location=London |publisher=[[Richard Taylor (editor)|Richard Taylor]] |page=16 |chapter=Section Carnivora |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/b22475886/page/16}}</ref> In 1917, [[Reginald Innes Pocock]] placed the cheetah in a subfamily of its own, Acinonychinae,<ref name=Pocock1917>{{cite journal |last1=Pocock |first1=R. I. |author-link=Reginald Innes Pocock |year=1917 |title=The classification of the existing Felidae |journal=[[Annals and Magazine of Natural History]] |series=Series 8 |volume=XX |issue=119 |pages=329–350 |doi=10.1080/00222931709487018 |url=https://archive.org/stream/annalsmagazineof8201917lond#page/332/mode/2up}}</ref> given its striking morphological resemblance to the [[greyhound]] and significant deviation from typical felid features; the cheetah was classified in [[Felinae]] in later taxonomic revisions.<ref name=caro1994/> |

|||

Although the cheetah is an African cat, molecular evidence indicates that the three species of the ''Puma'' lineage evolved in North America two to three million years ago, where they possibly had a common ancestor during the [[Miocene]].<ref name="adams">{{cite journal |last1 = Adams |first1 = D.B. |title = The Cheetah: Native American |journal = [[Science (journal)|Science]] |year = 1979 |volume = 205 |issue = 4411 |pages = 1155–8 |doi = 10.1126/science.205.4411.1155 |pmid=17735054}}</ref> They possibly diverged from this ancestor 8.25 million years ago.<ref name=johnson/> The cheetah diverged from the puma and the jaguarundi around 6.7 million years ago.<ref name="hunterwcw">{{cite book |last1 = Hunter |first1 = L. |title = Wild Cats of the World |date = 2015 |publisher = Bloomsbury Publishing |location = London, UK |isbn = 978-1-4729-1219-0 |pages = 167–76 }}</ref> A [[genome]] study concluded that cheetahs experienced two [[population bottleneck|genetic bottlenecks]] in their history, the first about 100,000 years ago and the second about 12,000 years ago, greatly lowering their [[genetic variability]]. These bottlenecks may have been associated with migrations across Asia and into Africa (with the current African population founded about 12,000 years ago), and/or with a depletion of prey species at the end of the Pleistocene.<ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Dobrynin |first1 = P. |last2 = Liu |first2 = S. |last3 = Tamazian |first3 = G. |last4 = Xiong |first4 = Z. |last5 = Yurchenko |first5 = A.A. |last6 = Krasheninnikova |first6 = K. |last7 = Kliver |first7 = S. |last8 = Schmidt-Küntzel |first8 = A. |title = Genomic legacy of the African cheetah, ''Acinonyx jubatus'' |journal = [[Genome Biology]] |year = 2015 |volume = 16 |pages = 277 |doi = 10.1186/s13059-015-0837-4 |url = http://genomebiology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13059-015-0837-4}} {{open access}}</ref> |

|||

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several cheetah [[Zoological specimen|specimens]] were described; some were proposed as [[subspecies]]. An example is the South African specimen known as the "woolly cheetah", named for its notably dense fur—this was described as a new species (''Felis lanea'') by [[Philip Sclater]] in 1877,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sclater |first1=P. |author-link=Philip Sclater |title=The secretary on additions to the menagerie |journal=[[Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London]] |date=1877 |volume=1877:May-Dec. |pages=530–533 |url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/90449#page/202/mode/1up |access-date=3 January 2020 |archive-date=20 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190720141620/https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/90449#page/202/mode/1up |url-status=live}}</ref> but the classification was mostly disputed.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lydekker |first1=R. |author-link=Richard Lydekker |title=The Royal Natural History |volume=1 |date=1893 |publisher=[[Frederick Warne & Co.]] |location=London |pages=442–446 |chapter=The hunting leopard |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/royalnaturalhist01lydeuoft/page/442}}</ref> There has been considerable confusion in the nomenclature of cheetahs and [[leopard]]s (''Panthera pardus'') as authors often confused the two; some considered "hunting leopards" an independent species, or equal to the leopard.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Baker |first1=E. D. |title=Sport in Bengal: and How, When and Where to Seek it |date=1887 |publisher=Ledger, Smith & Co |location=London |pages=[https://archive.org/details/sportinbengalhow00bakerich/page/205 205]–221 |url=https://archive.org/details/sportinbengalhow00bakerich}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Sterndale |first1=R. A. |title=Natural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon |date=1884 |publisher=Thacker, Spink & Co |location=Calcutta |pages=[https://archive.org/details/naturalhistoryof00ster/page/175 175]–178 |url=https://archive.org/details/naturalhistoryof00ster}}</ref> |

|||

Cheetah fossils found in the lower beds of the [[Olduvai Gorge]] site in northern [[Tanzania]] date back to the Pleistocene.<ref name="leakey">{{cite book |last1 = Leakey |first1 = L.S.B. |last2 = Hopwood |first2 = A.T. |title = Olduvai Gorge: A Report on the Evolution of the Hand-axe Culture in Beds I-IV |date = 1951 |pages = 20–5 |publisher = Cambridge University Press |location = Cambridge, UK }}</ref> The [[extinct]] species of ''Acinonyx'' are older than the cheetah, with the oldest known from the late [[Pliocene]]; these fossils are about three million years old.<ref name=mammal>{{cite journal |last = Krausman |first = P.R. |last2 = Morales |first2 = S.M. |year = 2005 |title = ''Acinonyx jubatus'' |journal = [[Mammalian Species]] |volume = 771 |pages = 1–6 |url = http://www.science.smith.edu/departments/biology/VHAYSSEN/msi/pdf/i1545-1410-771-1-1.pdf |doi = 10.1644/1545-1410(2005)771[0001:aj]2.0.co;2 }} {{open access}}</ref> These species include ''[[Acinonyx pardinensis]]'' (Pliocene epoch), notably larger than the modern cheetah, and ''[[Acinonyx intermedius|A.{{nbsp}}intermedius]]'' (mid-Pleistocene period).<ref name=janis/> While the range of ''A.{{nbsp}}intermedius'' stretched from Europe to [[China]], ''A{{nbsp}}pardinensis'' spanned over Eurasia as well as eastern and southern Africa.<ref name=mammal/> A variety of larger cheetah believed to have existed in Europe fell to extinction around half a million years ago.<ref name="mair">{{cite book |last1 = Mair |first1 = V.H. |title = Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World |date = 2006 |publisher = University of Hawai'i Press |location = Hawai'i, Honolulu |isbn = 978-0-8248-2884-4 |pages = 116–23 |oclc=62896389}}</ref> |

|||

Extinct North American cats resembling the cheetah had historically been assigned to ''Felis'', ''Puma'' or ''Acinonyx''. However, a [[Phylogenetics|phylogenetic]] analysis in 1990 placed these species under the genus ''[[American cheetah|Miracinonyx]]''.<ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Van Valkenburgh |first1 = B. |last2 = Grady |first2 = F. |last3 = Kurtén |first3 = B. |title = The Plio-Pleistocene cheetah-like ''Miracinonyx inexpectatus'' of North America |journal = [[Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology]] |year = 1990 |volume = 10 |issue = 4 |pages = 434–54 |doi = 10.1080/02724634.1990.10011827 }}</ref> ''Miracinonyx'' exhibited a high degree of similarity with the cheetah. However, in 1998, a [[DNA]] analysis showed that ''Miracinonyx inexpectatus'', ''M.{{nbsp}}studeri'', and ''M.{{nbsp}}trumani'' (early to late Pleistocene epoch), found in North America,<ref name="janis">{{cite book |last1 = Janis |first1 = C.M. |last2 = Scott |first2 = K.M. |last3 = Jacobs |first3 = L.L. |title = Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America |date = 1998 |publisher = Cambridge University Press |location = Cambridge, UK |isbn = 978-0-521-35519-3 |pages = 236–40 |edition = 1st }}</ref> are not true cheetahs; in fact, they are close relatives of the cougar.<ref name="Mattern and McLennan">{{cite journal |last1 = Mattern |first1 = M.Y. |first2 = D.A. |last2 = McLennan |year = 2000 |title = Phylogeny and speciation of felids |journal = [[Cladistics (journal)|Cladistics]] |volume = 16 |pages = 232–53 |doi = 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2000.tb00354.x |issue = 2 |url = https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Deborah_Mclennan/publication/229782333_Phylogeny_and_Speciation_of_Felids/links/02e7e521c97244a58a000000.pdf?inViewer=0&pdfJsDownload=0&origin=publication_detail }} {{open access}}</ref> |

|||

===Subspecies=== |

===Subspecies=== |

||

[[File:Acinonyx jubatus subspecies range.png|thumb|right|Subspecies' range]] |

|||

The five recognised [[subspecies]] of the cheetah are:<ref name=itis>{{ITIS|taxon=''Acinonyx jubatus''|id=183813|accessdate=13 February 2016}}</ref> |

|||

In 1975, five cheetah subspecies were considered [[Valid name (zoology)|valid]] [[Taxon|taxa]]: ''A. j. hecki'', ''A. j. jubatus'', ''A. j. raineyi'', ''A. j. soemmeringii'' and ''A. j. venaticus''.<ref name="Catsg2017"/> In 2011, a [[Phylogeography|phylogeographic]] study found minimal [[genetic variation]] between ''A. j. jubatus'' and ''A. j. raineyi''; only four subspecies were identified.<ref name="subspecies">{{cite journal |last1=Charruau |first1=P. |last2=Fernandes |first2=C. |last3=Orozco-terwengel |first3=P. |last4=Peters |first4=J. |last5=Hunter |first5=L. |last6=Ziaie |first6=H. |last7=Jourabchian |first7=A. |last8=Jowkar |first8=H. |last9=Schaller |first9=G. |last10=Ostrowski|first10=S. |last11=Vercammen |first11=P. |last12=Grange |first12=T. |last13=Schlotterer |first13=C. |last14=Kotze |first14=A. |last15=Geigl |first15=E. M. |last16=Walzer |first16=C. |last17=Burger |first17=P. A. |name-list-style=amp |title=Phylogeography, genetic structure and population divergence time of cheetahs in Africa and Asia: evidence for long-term geographic isolates |journal=[[Molecular Ecology]] |year=2011 |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=706–724 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04986.x |pmid=21214655 |pmc=3531615 |bibcode=2011MolEc..20..706C}}</ref> In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the [[IUCN]] Cat Specialist Group revised felid taxonomy and recognised these four subspecies as valid. Their details are tabulated below:<ref name="Catsg2017"/><ref name=MSW3>{{MSW3 Wozencraft |id=14000006 |pages=532–533 |heading=''Acinonyx jubatus''}}</ref> |

|||

*'''[[Asiatic cheetah]]''' (''A. j. venaticus'') <small>([[Edward Griffith (zoologist)|Griffith]], 1821)</small>: Also called the '''Iranian''' or '''Indian cheetah'''. Formerly occurred across southwestern Asia and India.<ref name="hildyard">{{cite book |last1 = Hildyard |first1 = A. |title = Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World |date = 2001 |publisher = Marshall Cavendish |location = New York, USA |isbn = 978-0-7614-7196-7 |pages = 250–1 }}</ref> According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources ([[IUCN]]), it is confined to [[Iran]], and is thus the only surviving cheetah subspecies indigenous to Asia. It has been classified as [[Critically Endangered]].<ref name=iucn2>{{IUCN |assessors=Durant, S., Marker, L., Purchase, N., Belbachir, F., Hunter, L., Packer, C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Sogbohossou, E. and Bauer, H. |year=2008 |id=220 |title=''Acinonyx jubatus'' ssp. ''venaticus'' |version=2015.2}}</ref> A 2004 study estimated the total population at 50 to 60.<ref name=farhadinia>{{cite journal |last1 = Farhadinia |first1 = M.S. |title = The last stronghold: Cheetah in Iran |journal = Cat News |year = 2004 |pages = 11–14 |url = http://wildlife.ir/Files/library/IranianCheetah_Farhadinia2004.pdf }} {{open access}}</ref> Later, a 2007 study gave the total population in Iran as 60 to 100; the majority of individuals were likely to be juveniles. The population has declined sharply since the mid-1970s.<ref name="hunter2007">{{cite journal |last2 = Jowkar |first2 = H. |last3 = Ziaie |first3 = H. |last4 = Schaller |first4 = G. |last5 = Balme |first5 = G. |last6 = Walzer |first6 = C. |last7 = Ostrowski |first7 = S. |last8 = Zahler |first8 = P. |last9 = Robert-Charrue |first9 = N.|last10=Kashiri|first10=K. |last11 = Christie |first11 = S. |last1 = Hunter |first1 = L. |title = Conserving the Asiatic cheetah in Iran: launching the first radio-telemetry study |journal = Cat News |year = 2007 |volume = 46 |pages = 8–11 }}</ref> As of 2012, only two captive individuals are known.<ref name=CatWatch/> |

|||

*'''[[Northwest African cheetah]]''' (''A. j. hecki'') <small>Hilzheimer, 1913</small>: Also called the '''Saharan cheetah'''. Found in northwestern Africa; the IUCN confirms its presence in only four countries: [[Algeria]], [[Benin]], [[Burkina Faso]] and [[Niger]]. Small populations are known to exist in the [[Ahaggar National Park|Ahaggar]] and [[Tassili N'Ajjer National Park|Tassili N'Ajjer]] National Parks (Algeria);<ref name="busby">{{cite report |last = Busby |first = G.B.J. |last2 = Gottelli |first2 = D. |last3 = Durant |first3 = S. |last4 = Wacher |first4 = T. |last5 = Marker |first5 = L. |last6 = Belbachir |first6 = F. |last7 = De Smet |first7 = K. |last8 = Belbachir-Bazi |first8 = A. |last9 = Fellous |first9 = A.|last10=Belghoul|first10=M. |title = A report from the Sahelo-Saharan interest group – Parc National de L’Ahaggar survey, Algeria (March 2005), Part 5: Using molecular genetics to study the presence of endangered carnivores (November 2006) [Unpublished report] |year = 2006 |pages = 1–19 |url = http://users.ox.ac.uk/~some2456/docs/Carniv_Mol_Gen_Ahaggar_Report_2006.pdf }} {{open access}}</ref> a 2003 study estimated a population of 20 to 40 individuals in Ahaggar National Park.<ref name="hamdine">{{cite journal |last1 = Hamdine |first1 = W. |last2 = Meftah |first2 = T. |last3 = Sehki |first3 = A. |title = Distribution and status of cheetahs (''Acinonyx jubatus'') in the Algerian Central Sahara (Ahaggar and Tassili) |journal = Mammalia |year = 2003 |volume = 67 |issue = 3 |pages = 439–43 |doi=10.1515/mamm.2003.67.3.439}}</ref> In Niger, cheetahs have been reported from the [[Aïr Mountains]], [[Ténéré]], [[Termit Massif]], [[Talak, Niger|Talak]] and Azaouak valley. A 1993 study reported a population of 50 from Ténéré. In Benin, the cheetah still survives in [[Pendjari National Park]] and [[W National Park]]. The status is obscure in Burkina Faso, where individuals may be confined to the southeastern region. With the total world population estimated at less than 250 mature individuals, it is listed as [[Critically endangered species|Critically Endangered]].<ref name=iucn3>{{IUCN |assessors=Durant, S., Marker, L., Purchase, N., Belbachir, F., Hunter, L., Packer, C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Sogbohossou, E. and Bauer, H. |year=2008 |id=221 |title=''Acinonyx jubatus'' ssp. ''hecki''|version=2015.2}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[South African cheetah]]''' (''A. j. jubatus'') <small>(Schreber, 1775)</small>: Also called the '''Namibian cheetah'''. Occurs in southern African countries such as [[Namibia]], [[Botswana]], [[Zimbabwe]], [[South Africa]] and [[Zambia]]. Diverged from the Asiatic cheetah nearly 0.32–0.67 million years ago.<ref name="subspecies">{{cite journal |last1 = Charruau |first1 = P. |last2 = Fernandes |first2 = C. |last3 = Orozco-terwengel |first3 = P. |last4 = Peters |first4 = J. |last5 = Hunter |first5 = L. |last6 = Ziaie |first6 = H. |last7 = Jourabchian |first7 = A. |last8 = Jowkar |first8 = H. |last9 = Schaller |first9 = G. |author9-link = George Schaller|last10=Ostrowski|first10=S. |last11 = Vercammen |first11 = P. |last12 = Grange |first12 = T. |last13 = Schlotterer |first13 = C. |last14 = Kotze |first14 = A. |last15 = Geigl |first15 = E.-M. |last16 = Walzer |first16 = C. |last17 = Burger |first17 = P. A. |title = Phylogeography, genetic structure and population divergence time of cheetahs in Africa and Asia: evidence for long-term geographic isolates |journal = Molecular Ecology |year = 2011 |volume = 20 |issue = 4 |pages = 706–24 |doi = 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04986.x }}</ref> In 2007 the population was roughly estimated at less than 5,000 to maximum 6,500 adult individuals.<ref name=south1>{{cite report |title = Regional conservation strategy for the cheetah and African wild dog in southern Africa |url = https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/Rep-2007-002.pdf |publisher = [[IUCN]] }} {{open access}}</ref><ref name=south2>{{cite report |last1 = Purchase |first1 = G. |last2 = Marker |first2 = L. |last3 = Marnewick |first3 = K. |last4 = Klein |first4 = R. |last5 = Williams |first5 = S. |title = Regional assessment of the status, distribution and conservation needs of cheetahs in southern Africa |year = 2007 |pages = 1–3 |publisher = [[IUCN]] Cat Specialist Group |url = http://www.catsg.org/fileadmin/filesharing/3.Conservation_Center/3.2._Status_Reports/Cheetah/Purchase_et_al_2007_Regional_assessment.pdf }} {{open access}}</ref> Not listed by the IUCN.<ref name=iucn/> |

|||

*'''[[Sudan cheetah]]''' (''A. j. soemmeringii'') <small>([[Leopold Fitzinger|Fitzinger]], 1855)</small>: Also called the '''central''' or '''northeast African cheetah'''. Found in the central and northeastern regions of the continent and the [[Horn of Africa]]. This subspecies was considered identical to the South African cheetah until a 2011 genetic analysis demonstrated significant differences between the two.<ref name=subspecies/><ref name=distinct1>{{cite news |title = Iran's endangered cheetahs are a unique subspecies |last = Davies |first = E. |url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_9365000/9365567.stm |publisher = [[BBC]] |date = 24 January 2011 |accessdate = 22 March 2016 }}</ref> |

|||

*'''[[Tanzanian cheetah]]''' (''A. j. raineyii'' [[Synonym (taxonomy)|syn]]. ''A. j. fearsoni'') <small>[[Edmund Heller|Heller]], 1913</small>: Also called the '''east African cheetah'''. Found in [[Kenya]], [[Somalia]], Tanzania, and [[Uganda]]. The total population in 2007 was estimated at 2,572 adults and independent adolescents. Significant populations occur in the [[Maasai Mara]] and the [[Serengeti]] [[ecoregion]]s.<ref name=iucn/> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

{{Gallery |

|||

|- |

|||

|title=The five subspecies of the cheetah |

|||

! Subspecies !! Details !! Image |

|||

|width=180 |

|||

|- style="vertical-align: top;" |

|||

|height=200 |

|||

|[[Southeast African cheetah]] (''A. j. jubatus'') {{small|(Schreber, 1775)}}, [[Synonym (taxonomy)|syn.]] ''A. j. raineyi'' {{small|[[Edmund Heller|Heller]], 1913}}<ref name=heller>{{cite journal |author=Heller, E. |year=1913 |title=New races of carnivores and baboons from equatorial Africa and Abyssinia |journal=[[Smithsonian Contributions and Studies Series|Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections]] |volume=61 |issue=19 |pages=1–12}}</ref> |

|||

|lines=1 |

|||

|The [[Nominate subspecies|nominate]] subspecies;<ref name=MSW3/> it [[Genetic divergence|genetically diverged]] from the Asiatic cheetah 67,000–32,000 years ago.<ref name="subspecies"/> As of 2016, the largest population of nearly 4,000 individuals is sparsely distributed in Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and Zambia.<ref name=durant2017/> |

|||

|align=center |

|||

|[[File:Cheetah, Masai Mara (52448476886).jpg|frameless|alt=Southeast African cheetah in Masai Mara, Kenya]] |

|||

|File:Asian cheetah.jpg|Asian cheetah |

|||

|- style="vertical-align: top;" |

|||

|File:SaharanCheetah.gif|Northwest African cheetah |

|||

|[[Asiatic cheetah]] (''A. j. venaticus'') {{small|[[Edward Griffith (zoologist)|Griffith]], 1821}}<ref name=griffith>{{cite book |last=Griffith |first=E. |year=1821 |title=General and Particular Descriptions of the Vertebrated Animals, arranged Conformably to the Modern Discoveries and Improvements in Zoology. Order Carnivora |location=London |publisher=Baldwin, Cradock and Joy |chapter=''Felis venatica'' |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/generalparticula00grif/page/n149 |page=93}}</ref> |

|||

|File:Cheetah (Kruger National Park, South Africa, 2001).jpg|South African cheetah |

|||

|This subspecies is confined to central Iran, and is the only surviving cheetah population in Asia.<ref name=marker4>{{cite book |editor1=Marker, L. |editor2=Boast, L. K. |editor3=Schmidt-Kuentzel, A. |title=Cheetahs: Biology and Conservation |date=2018 |publisher=Academic Press |location=London |isbn=978-0-12-804088-1 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H3rXDgAAQBAJ&pg=33 |pages=33–54 |chapter=Cheetah rangewide status and distribution |last1=Marker |first1=L. |last2=Cristescu |first2=B. |last3=Morrison |first3=T. |last4=Flyman |first4=M. V. |last5=Horgan |first5=J. |last6=Sogbohossou |first6=E. A. |last7=Bissett |first7=C. |last8=van der Merwe |first8=V. |last9=Machado |first9=I. B. de M. |last10=Fabiano |first10=E. |last11=van der Meer |first11=E. |last12=Aschenborn |first12=O. |last13=Melzheimer |first13=J. |last14=Young-Overton |first14=K. |last15=Farhadinia |first15=M. S. |last16=Wykstra |first16=M. |last17=Chege |first17=M. |last18=Abdoulkarim |first18=S. |last19=Amir |first19=O. G. |last20=Mohanun |first20=A. S. |last21=Paulos |first21=O. D. |last22=Nhabonga |first22=A. R. |last23=M'soka |first23=J. L. J. |last24=Belbachir |first24=F. |last25=Ashenafi |first25=Z. T. |last26=Nghikembua |first26=M. T. |name-list-style=amp |access-date=19 April 2020 |archive-date=7 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220407160713/https://books.google.com/books?id=H3rXDgAAQBAJ&pg=33 |url-status=live}}</ref> As of 2022, only 12 individuals were estimated to survive in Iran, nine of which are males and three of which are females.<ref>{{cite web |date=10 January 2022 |title=Iran says only 12 Asiatic cheetahs left in the country |url=https://www.timesofisrael.com/iran-says-only-12-asiatic-cheetahs-left-in-the-country/|url-status=live |website=The Times of Israel|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220110082914/https://www.timesofisrael.com/iran-says-only-12-asiatic-cheetahs-left-in-the-country/ |archive-date=10 January 2022}}</ref> |

|||

|File:Cheetah at Whipsnade Zoo, Dunstable.jpg|Sudan cheetah |

|||

|File: |

|[[File:Iranian Cheetah roars.jpg|frameless]] |

||

|- style="vertical-align: top;" |

|||

|[[Northeast African cheetah]] (''A. j. soemmeringii'') {{small|[[Leopold Fitzinger|Fitzinger]], 1855}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Fitzinger |first=L. |year=1855 |chapter=Bericht an die kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften über die von dem Herrn Consultatsverweser Dr. Theodor v. Heuglin für die kaiserliche Menagerie zu Schönbrunn mitgebrachten lebenden Thiere [Report to the Imperial Academy of Sciences about the Consultant Administrator Dr. Theodor v. Heuglin about the Living Animals brought to the Imperial Menagerie at Schönbrunn] |title=Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe |trans-title=Meeting Reports from the Imperial Academy of Sciences. Mathematical and Natural Science Class |pages=242–253 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/sitzungsbericht171855kais/page/244 |language=de}}</ref> |

|||

|This subspecies occurs in the northern Central African Republic, Chad, Ethiopia and South Sudan in small and heavily fragmented populations; in 2016, the largest population of 238 individuals occurred in the northern CAR and southeastern Chad. It diverged genetically from the southeast African cheetah 72,000–16,000 years ago.<ref name=subspecies/> |

|||

|[[File:Cheetah in the shade DVIDS147321.jpg|frameless|alt=Northeast African cheetah resting on the ground in Djibouti City, Djibouti]] |

|||

|- style="vertical-align: top;" |

|||

|[[Northwest African cheetah]] (''A. j. hecki'') {{small|[[:de: Max Hilzheimer|Hilzheimer]], 1913}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Hilzheimer |first=M. |year=1913 |chapter=Über neue Gepparden nebst Bemerkungen über die Nomenklatur dieser Tiere [About new cheetahs and comments about the nomenclature of these animals] |language=de |title=Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin |trans-title=Meeting Reports of the Society of Friends of Natural Science in Berlin |pages=283–292 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/sitzungsberichte1913gese/page/n311}}</ref> |

|||

|This subspecies occurs in Algeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.<ref name=iucn /> In 2016, the largest population of 191 individuals occurred in [[Adrar des Ifoghas]], Ahaggar and [[Tassili n'Ajjer]] in south-central Algeria and northeastern Mali.<ref name=marker4/> It is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List.<ref name=iucn3>{{cite iucn |author1=Durant, S. |author2=Marker, L. |author3=Purchase, N. |author4=Belbachir, F. |author5=Hunter, L. |author6=Packer, C. |author7=Breitenmoser-Würsten, C. |author8=Sogbohossou, E. |author9=Bauer, H. |name-list-style=amp |year=2008 |page=e.T221A13035738 |title=''Acinonyx jubatus'' ssp. ''hecki'' |doi=10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T221A13035738.en}}</ref> |

|||

| |

|||

|} |

|||

==Phylogeny and evolution== |

|||

{{cladogram|title= |

|||

|caption=The ''Puma'' lineage of the family [[Felidae]], depicted along with closely related genera<ref name="bcw2"/> |

|||

|1={{clade | style=font-size:90%;line-height:100%;width:475px; |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|label1=''Lynx'' lineage |

|||

|1=''[[Lynx]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|label1=''Puma'' lineage |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|label1=''[[Acinonyx]]'' |

|||

|1='''Cheetah''' [[File:Acinonyx jubatus (white background).jpg|60px|alt=Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus)]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|label1=''[[Puma (genus)|Puma]]'' |

|||

|1=[[Cougar]] ''P. concolor'' [[File:Felis concolor - 1818-1842 - Print - Iconographia Zoologica - Special Collections University of Amsterdam -(white background).jpg|50px|alt=Cougar (Puma concolor)]] |

|||

|label2=''[[Herpailurus]]'' |

|||

|2=[[Jaguarundi]] ''H. yagouaroundi'' [[File:Lydekker_-_Eyra_White_background.jpg|50px|alt=Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi)]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|label1=Domestic cat lineage |

|||

|1=''[[Felis]]'' |

|||

|label2=Leopard cat lineage |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Otocolobus]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Prionailurus]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

The cheetah's closest relatives are the [[cougar]] (''Puma concolor'') and the [[jaguarundi]] (''Herpailurus yagouaroundi'').<ref name="Catsg2017">{{cite journal |author1=Kitchener, A. C. |author2=Breitenmoser-Würsten, C. |author3=Eizirik, E. |author4=Gentry, A. |author5=Werdelin, L. |author6=Wilting, A. |author7=Yamaguchi, N. |author8=Abramov, A. V. |author9=Christiansen, P. |author10=Driscoll, C. |author11=Duckworth, J. W. |author12=Johnson, W. |author13=Luo, S.-J. |author14=Meijaard, E. |author15=O'Donoghue, P. |author16=Sanderson, J. |author17=Seymour, K. |author18=Bruford, M. |author19=Groves, C. |author20=Hoffmann, M. |author21=Nowell, K. |author22=Timmons, Z. |author23=Tobe, S. |year=2017 |name-list-style=amp |title=A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: the final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group |journal=Cat News |issue=Special Issue 11 |url=https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y |pages=30–31 |access-date=13 May 2018 |archive-date=17 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200117172708/https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y |url-status=live}}</ref> Together, these three species form the ''Puma'' lineage, one of the eight lineages of the extant [[felid]]s; the ''Puma'' lineage [[Genetic divergence|diverged]] from the rest 6.7 [[Mya (unit)|mya]]. The [[sister group]] of the ''Puma'' lineage is a [[clade]] of smaller [[Old World]] cats that includes the genera ''[[Felis]]'', ''[[Otocolobus]]'' and ''[[Prionailurus]]''.<ref name="bcw2">{{cite book |last1=Werdelin |first1=L. |last2=Yamaguchi |first2=N. |last3=Johnson |first3=W. E. |last4=O'Brien |first4=S. J. |chapter=Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae) |name-list-style=amp |year=2010 |pages=59–82 |chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266755142 |editor1-last=Macdonald |editor1-first=D. W. |editor2-last=Loveridge |editor2-first=A. J. |title=Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford, UK |isbn=978-0-19-923445-5 |access-date=7 January 2020 |archive-date=25 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180925141956/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266755142 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The oldest cheetah fossils, excavated in eastern and southern Africa, date to 3.5–3 mya; the earliest known specimen from South Africa is from the lowermost deposits of the Silberberg Grotto ([[Sterkfontein]]).<ref name=mammal/><ref name=skinner/> Though incomplete, these fossils indicate forms larger but less [[cursorial]] than the modern cheetah.<ref name="marker2">{{cite book |author1=Van Valkenburgh, B. |title=Cheetahs: Biology and Conservation |author2=Pang, B. |author3=Cherin, M. |author4=Rook, L. |date=2018 |publisher=Academic Press |isbn=978-0-12-804088-1 |editor1=Marker, L. |location=London |chapter=The cheetah: evolutionary history and paleoecology |editor2=Boast, L. K. |editor3=Schmidt-Kuentzel, A. |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H3rXDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA25 |name-list-style=amp |access-date=26 March 2023 |archive-date=28 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328013452/https://books.google.com/books?id=H3rXDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA25 |url-status=live}}</ref> The first occurrence of the modern species ''A. jubatus'' in Africa may come from Cooper's D, a site in South Africa dating back to 1.5 to 1.4 Ma, during the [[Calabrian (stage)|Calabrian]] [[stage (geology)|stage]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=O'Regan |first1=Hannah J. |last2=Steininger |first2=Christine |date=30 June 2017 |title=Felidae from Cooper's Cave, South Africa (Mammalia: Carnivora) |url=https://bioone.org/journals/Geodiversitas/volume-39/issue-2/g2017n2a8/Felidae-from-Coopers-Cave-South-Africa-Mammalia-Carnivora/10.5252/g2017n2a8.short |journal=[[Geodiversitas]] |language=en |volume=39 |issue=2 |pages=315–332 |doi=10.5252/g2017n2a8 |s2cid=53959454 |issn=1280-9659 |access-date=28 January 2024 |via=BioOne Digital Library |archive-date=29 January 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240129032419/https://bioone.org/journals/Geodiversitas/volume-39/issue-2/g2017n2a8/Felidae-from-Coopers-Cave-South-Africa-Mammalia-Carnivora/10.5252/g2017n2a8.short |url-status=live}}</ref> Fossil remains from Europe are limited to a few [[Middle Pleistocene]] specimens from [[Hundsheim]] (Austria) and Mosbach Sands (Germany).<ref name="hemmer">{{cite journal |last1=Hemmer |first1=H. |last2=Kahlke |first2=R.-D. |last3=Keller |first3=T. |name-list-style=amp |title=Cheetahs in the Middle Pleistocene of Europe: ''Acinonyx pardinensis'' (sensu lato) ''intermedius'' (Thenius, 1954) from the Mosbach Sands (Wiesbaden, Hesse, Germany) |journal=Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen |date=2008 |volume=249 |issue=3 |pages=345–356 |doi=10.1127/0077-7749/2008/0249-0345}}</ref> Cheetah-like cats are known from as late as 10,000 years ago from the Old World. The [[giant cheetah]] (''A. pardinensis''), significantly larger and slower compared to the modern cheetah, occurred in Eurasia and eastern and southern Africa in the [[Villafranchian]] period roughly 3.8–1.9 mya.<ref name=caro1994/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Cherin |first1=M. |last2=Iurino |first2=D. A. |last3=Sardella |first3=R. |last4=Rook |first4=L. |name-list-style=amp |title=''Acinonyx pardinensis'' (Carnivora, Felidae) from the Early Pleistocene of Pantalla (Italy): predatory behavior and ecological role of the giant Plio–Pleistocene cheetah |journal=[[Quaternary Science Reviews]] |year=2014 |volume=87 |pages=82–97 |doi=10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.01.004 |bibcode=2014QSRv...87...82C}}</ref> In the Middle Pleistocene a smaller cheetah, ''A. intermedius'', ranged from Europe to China.<ref name=mammal>{{cite journal |last1=Krausman |first1=P. R. |last2=Morales |first2=S. M. |name-list-style=amp |year=2005 |title=''Acinonyx jubatus'' |journal=[[Mammalian Species]] |volume=771 |pages=1–6 |url=http://www.science.smith.edu/departments/biology/VHAYSSEN/msi/pdf/i1545-1410-771-1-1.pdf |doi=10.1644/1545-1410(2005)771[0001:aj]2.0.co;2 |s2cid=198969000 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304045916/http://www.science.smith.edu/departments/biology/VHAYSSEN/msi/pdf/i1545-1410-771-1-1.pdf |archive-date=4 March 2016}}</ref> The modern cheetah appeared in Africa around 1.9 mya; its fossil record is restricted to Africa.<ref name=marker2/> |

|||

Extinct North American cheetah-like cats had historically been classified in ''Felis'', ''Puma'' or ''Acinonyx''; two such species, ''F. studeri'' and ''F. trumani'', were considered to be closer to the puma than the cheetah, despite their close similarities to the latter. Noting this, palaeontologist Daniel Adams proposed ''[[Miracinonyx]]'', a new subgenus under ''Acinonyx'', in 1979 for the North American cheetah-like cats;<ref name="adams"/> this was later elevated to genus rank.<ref name="Valkenburgh1990" /> Adams pointed out that North American and Old World cheetah-like cats may have had a common ancestor, and ''Acinonyx'' might have originated in North America instead of Eurasia.<ref name="adams">{{cite journal |last1=Adams |first1=D. B. |s2cid=17951039 |title=The cheetah: native American |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |year=1979 |volume=205 |issue=4411 |pages=1155–1158 |doi=10.1126/science.205.4411.1155 |pmid=17735054 |bibcode=1979Sci...205.1155A}}</ref> However, subsequent research has shown that ''Miracinonyx'' is phylogenetically closer to the cougar than the cheetah;<ref name=sabre>{{cite journal |last1=Barnett |first1=R. |last2=Barnes |first2=I. |last3=Phillips |first3=M. J. |last4=Martin |first4=L. D. |last5=Harington |first5=C. R. |last6=Leonard |first6=J. A. |last7=Cooper |first7=A. |title=Evolution of the extinct sabretooths and the American cheetah-like cat |journal=[[Current Biology]] |year=2005 |volume=15 |issue=15 |pages=R589–R590 |doi=10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.052 |pmid=16085477 |s2cid=17665121 |name-list-style=amp|doi-access=free |bibcode=2005CBio...15.R589B}}</ref> the similarities to cheetahs have been attributed to [[parallel evolution]].<ref name="bcw2"/> |

|||

The three species of the ''Puma'' lineage may have had a common ancestor during the [[Miocene]] (roughly 8.25 mya).<ref name=adams/><ref name=johnson>{{cite journal |pmid=9071018 |year=1997 |last1=Johnson |first1=W. E. |last2=O'Brien |first2=S. J. |name-list-style=amp |title=Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Felidae using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 mitochondrial genes |volume=44 |issue=S1 |pages=S98–S116 |journal=Journal of Molecular Evolution |doi=10.1007/PL00000060 |url=https://zenodo.org/record/1232587 |bibcode=1997JMolE..44S..98J |s2cid=40185850 |access-date=6 June 2018 |archive-date=4 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201004075723/https://zenodo.org/record/1232587 |url-status=live}}</ref> Some suggest that North American cheetahs possibly migrated to Asia via the [[Bering Strait]], then dispersed southward to Africa through Eurasia at least 100,000 years ago;<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Johnson |first1=W. E. |title=The Late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: a genetic assessment |journal=Science |date=2006 |volume=311 |issue=5757 |pages=73–77 |doi=10.1126/science.1122277 |pmid=16400146 |bibcode=2006Sci...311...73J |s2cid=41672825 |url=https://zenodo.org/record/1230866 |access-date=17 March 2020 |archive-date=4 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201004075725/https://zenodo.org/record/1230866 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=dobrynin>{{cite journal |last1=Dobrynin |first1=P. |last2=Liu |first2=S. |last3=Tamazian |first3=G. |last4=Xiong |first4=Z. |last5=Yurchenko |first5=A. A. |last6=Krasheninnikova |first6=K. |last7=Kliver |first7=S. |last8=Schmidt-Küntzel |first8=A. |name-list-style=amp |title=Genomic legacy of the African cheetah, ''Acinonyx jubatus'' |journal=[[Genome Biology]] |year=2015 |volume=16 |page=277 |doi=10.1186/s13059-015-0837-4 |pmid=26653294 |pmc=4676127 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=O'Brien |first1=S. J. |last2=Johnson |first2=W. E. |name-list-style=amp |title=The evolution of cats |journal=[[Scientific American]] |date=2007 |volume=297 |issue=1 |pages=68–75 |doi=10.1038/scientificamerican0707-68 |bibcode=2007SciAm.297a..68O |url=http://www.bio-nica.info/biblioteca/O%27brien2007EvolutionCats.pdf |access-date=5 January 2020 |archive-date=5 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190105160544/http://www.bio-nica.info/biblioteca/O%27brien2007EvolutionCats.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> some authors have expressed doubt over the occurrence of cheetah-like cats in North America, and instead suppose the modern cheetah to have evolved from Asian populations that eventually spread to Africa.<ref name=sabre/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Faurby |first1=S. |last2=Werdelin |first2=L. |last3=Svenning |first3=J. C. |name-list-style=amp |title=The difference between trivial and scientific names: there were never any true cheetahs in North America |journal=Genome Biology |year=2016 |volume=17 |issue=1 |page=89 |doi=10.1186/s13059-016-0943-y |pmid=27150269 |pmc=4858926 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The cheetah is thought to have experienced two [[population bottleneck]]s that greatly decreased the [[genetic variability]] in populations; one occurred about 100,000 years ago that has been correlated to migration from North America to Asia, and the second 10,000–12,000 years ago in Africa, possibly as part of the [[Quaternary extinction event|Late Pleistocene extinction event]].<ref name=dobrynin/><ref name="o'brien1987">{{cite journal |last1=O'Brien |first1=S. J. |last2=Wildt |first2=D. E. |last3=Bush |first3=M. |last4=Caro |first4=T. M. |author4-link=Tim Caro |last5=FitzGibbon |first5=C. |last6=Aggundey |first6=I. |last7=Leakey |first7=R. E. |name-list-style=amp |title=East African cheetahs: evidence for two population bottlenecks? |journal=[[PNAS]] |year=1987 |volume=84 |issue=2 |pages=508–511 |pmid=3467370 |pmc=304238 |doi=10.1073/pnas.84.2.508 |bibcode=1987PNAS...84..508O|doi-access = free}}</ref><ref name="o'brien1993">{{cite journal |last1=Menotti-Raymond |first1=M. |last2=O'Brien |first2=S. J. |name-list-style=amp |title=Dating the genetic bottleneck of the African cheetah |journal=PNAS |year=1993 |volume=90 |issue=8 |pages=3172–3176 |pmid=8475057 |doi=10.1073/pnas.90.8.3172 |pmc=46261 |bibcode=1993PNAS...90.3172M|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

==Genetics== |

==Genetics== |

||

The [[Diploidy|diploid]] number of [[chromosome]]s in the cheetah is 38, the same as in |

The [[Diploidy|diploid]] number of [[chromosome]]s in the cheetah is 38, the same as in most other felids.<ref name=Geptner1972/> The cheetah was the first felid observed to have unusually low genetic variability among individuals,<ref name="bcw4">{{cite book |first1=M. |last1=Culver |first2=C. |last2=Driscoll |first3=E. |last3=Eizirik |first4=G. |last4=Spong |name-list-style=amp |chapter=Genetic applications in wild felids |pages=107–123 |year=2010 |chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308022395 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6USDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA115 |editor1-last=Macdonald |editor1-first=D. W. |editor2-last=Loveridge |editor2-first=A. J. |title=Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford, UK |isbn=978-0-19-923445-5 |access-date=7 January 2020 |archive-date=28 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328013747/https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6USDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA115 |url-status=live}}</ref> which has led to poor breeding in captivity, increased [[spermatozoa]]l defects, high juvenile mortality and increased susceptibility to diseases and infections.<ref name="o'brien1985">{{cite journal |last1=O'Brien |first1=S. J. |last2=Roelke |first2=M. |last3=Marker |first3=L. |last4=Newman |first4=A. |last5=Winkler |first5=C. |last6=Meltzer |first6=D. |last7=Colly |first7=L. |last8=Evermann |first8=J. |last9=Bush |first9=M. |last10=Wildt |first10=D. E. |title=Genetic basis for species vulnerability in the cheetah|name-list-style=amp |journal=Science |year=1985 |volume=227 |issue=4693 |pages=1428–1434 |doi=10.1126/science.2983425 |pmid=2983425 |bibcode=1985Sci...227.1428O}}</ref><ref name=obrien2017>{{cite journal |last1=O'Brien |first1=S. J |last2=Johnson |first2=W. E |last3=Driscoll |first3=C. A |last4=Dobrynin |first4=P. |last5=Marker |first5=L. |name-list-style=amp |title=Conservation genetics of the cheetah: lessons learned and new opportunities |journal=[[Journal of Heredity]] |date=2017 |volume=108 |issue=6 |pages=671–677 |doi=10.1093/jhered/esx047 |pmid=28821181 |pmc=5892392}}</ref> A prominent instance was the deadly [[feline coronavirus]] outbreak in a cheetah breeding facility of Oregon in 1983 which had a mortality rate of 60%, higher than that recorded for previous [[epizootic]]s of [[feline infectious peritonitis]] in any felid.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Heeney |first1=J. L. |last2=Evermann |first2=J. F. |last3=McKeirnan |first3=A. J. |last4=Marker-Kraus |first4=L. |last5=Roelke |first5=M. E. |last6=Bush |first6=M. |last7=Wildt |first7=D. E. |last8=Meltzer |first8=D. G. |last9=Colly |first9=L. |last10=Lukas |first10=J. |name-list-style=amp |title=Prevalence and implications of feline coronavirus infections of captive and free-ranging cheetahs (''Acinonyx jubatus'') |journal=[[Journal of Virology]] |date=1990 |volume=64 |issue=5 |pages=1964–1972 |doi=10.1128/JVI.64.5.1964-1972.1990 |pmid=2157864 |pmc=249350}}</ref> The remarkable homogeneity in cheetah genes has been demonstrated by experiments involving the [[major histocompatibility complex]] (MHC); unless the MHC genes are highly homogeneous in a population, [[Skin grafting|skin grafts]] exchanged between a pair of unrelated individuals would be rejected. Skin grafts exchanged between unrelated cheetahs are accepted well and heal, as if their genetic makeup were the same.<ref name=yuhki>{{cite journal |last1=Yuhki |first1=N. |last2=O'Brien |first2=S. J. |name-list-style=amp |title=DNA variation of the mammalian major histocompatibility complex reflects genomic diversity and population history |journal=PNAS |year=1990 |volume=87 |issue=2 |pages=836–840 |pmid=1967831 |pmc=53361 |doi=10.1073/pnas.87.2.836 |bibcode=1990PNAS...87..836Y|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=tears>{{cite book |last1=O'Brien |first1=S. J. |title=Tears of the Cheetah: the Genetic Secrets of our Animal Ancestors |date=2003 |publisher=Thomas Dunne Books |location=New York |isbn=978-0-312-33900-5 |pages=15–34 |chapter=Tears of the cheetah |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=S9iLCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA15 |access-date=30 April 2020 |archive-date=28 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328013712/https://books.google.com/books?id=S9iLCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA15 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

The low genetic diversity is thought to have been created by two [[population bottleneck]]s from about 100,000 years and about 12,000 years ago, respectively. The resultant level of genetic variation is around 0.1–4% of average living species, lower than that of [[Tasmanian devil]]s, [[Virunga gorilla]]s, [[Amur tiger]]s, and even highly inbred domestic cats and dogs.<ref name=obrien2017/> |

|||

===King cheetah=== |

===King cheetah=== |

||

[[File:King cheetah.jpg|thumb|upright| |

[[File:King cheetah.jpg|thumb|upright|alt=A seated king cheetah|King cheetah]] |

||

The king cheetah is a variety of cheetah with a rare [[mutation]] for cream-coloured fur marked with large, blotchy spots and three dark, wide stripes extending from their neck to the tail.<ref name="thompson">{{cite book |last1 = Thompson |first1 = S.E. |title = Built for Speed: The Extraordinary, Enigmatic Cheetah |year = 1998 |publisher = Lerner Publications Co. |location = Minneapolis, USA |isbn = 978-0-8225-2854-8 |pages = 66–8 }}</ref> In 1926 Major A.{{nbsp}}Cooper wrote about an animal he had shot near modern-day [[Harare]]. Describing the animal, he noted its remarkable similarity to the cheetah, but the body of this individual was covered with fur as thick as that of a [[snow leopard]] and the spots merged to form stripes. He suggested that it could be a [[Hybrid (biology)|cross]] between a leopard and a cheetah. After further similar animals were discovered, it was established they were similar to the cheetah in having non-retractable [[claw]]s{{snds}}a characteristic feature of the cheetah.<ref name="heuvelmans">{{cite book |last1 = Heuvelmans |first1 = B. |title = On the Track of Unknown Animals |year = 1995 |publisher = Kegan Paul International |location = London, UK |isbn = 978-0-7103-0498-8 |pages = 500–2 |edition = 3rd, revised }}</ref><ref name=pocock/> |

|||

The king cheetah is a variety of cheetah with a rare [[mutation]] for cream-coloured fur marked with large, blotchy spots and three dark, wide stripes extending from the neck to the tail.<ref name=thompson>{{cite book |last1=Thompson |first1=S. E. |title=Built for Speed: The Extraordinary, Enigmatic Cheetah |year=1998 |publisher=Lerner Publications Co |location=Minneapolis |isbn=978-0-8225-2854-8 |chapter=Cheetahs in a bottleneck |chapter-url={{Google Books |plainurl=yes |page=61 |id=wNV5xsM1GVYC}} |pages=61–75 |url=https://archive.org/details/builtforspeedext00thom/page/61}}</ref> In [[Manicaland]], [[Zimbabwe]], it was known as ''nsuifisi'' and thought to be a [[Hybrid (biology)|cross]] between a leopard and a [[hyena]].<ref name=bottriell/> In 1926, Major A. Cooper wrote about a cheetah-like animal he had shot near modern-day [[Harare]], with fur as thick as that of a [[snow leopard]] and spots that merged to form stripes. He suggested it could be a cross between a leopard and a cheetah. As more such individuals were observed it was seen that they had non-retractable claws like the cheetah.<ref name=pocock/><ref name=heuvelmans>{{cite book |last1=Heuvelmans |first1=B. |title=On the Track of Unknown Animals |year=1995 |publisher=[[Routledge]] |location=Abingdon |isbn=978-1-315-82885-5 |pages=495–502 |edition=3rd, revised |chapter=Mngwa, the strange one |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u64ABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA495 |access-date=20 December 2019 |archive-date=28 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328013747/https://books.google.com/books?id=u64ABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA495 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

English zoologist [[Reginald Innes Pocock]] described it as a new species by the name of ''Acinonyx rex'' ("rex" being Latin for "king", the name translated to "king cheetah");<ref name="pocock">{{cite journal |last1 = Pocock |first1 = R.I. |authorlink = Reginald Innes Pocock |title = Description of a new species of cheetah (''Acinonyx'') |journal = [[Journal of Zoology|Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London]] |year = 1927 |volume = 97 |issue = 1 |pages = 245–52 |doi = 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1927.tb02258.x }}</ref> However, he reverted from this in 1939. English hunter-naturalist [[Abel Chapman]] considered it to be a [[colour morph]] of the spotted cheetah.<ref name=catsg/><ref name="shuker">{{cite book |last1 = Shuker |first1 = K.P.N. |title = Mystery Cats of the World: From Blue Tigers to Exmoor Beasts |year = 1989 |publisher = Hale |location = London, UK |isbn = 978-0-7090-3706-4 |page = 119 }}</ref> Since 1927 the king cheetah has been reported five more times in the wild; an individual was photographed in 1975.<ref name="bottriell">{{cite book |last1 = Bottriell |first1 = L.G. |title = King Cheetah : The Story of the Quest |year = 1987 |publisher = Brill |location = Leiden, Netherlands |isbn = 978-90-04-08588-6 }}</ref> |

|||

In 1927, Pocock described these individuals as a new species by the name of ''Acinonyx rex'' ("king cheetah").<ref name="pocock">{{cite journal |last1=Pocock |first1=R. I. |author-link=Reginald Innes Pocock |title=Description of a new species of cheetah (''Acinonyx'') |journal=[[Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London]] |year=1927 |volume=97 |issue=1 |pages=245–252 |doi=10.1111/j.1096-3642.1927.tb02258.x}}</ref> However, in the absence of proof to support his claim, he withdrew his proposal in 1939. [[Abel Chapman]] considered it a [[colour morph]] of the normally spotted cheetah.<ref name=catsg>{{cite web |title=Cheetah—guépard—duma—''Acinonyx jubatus'' |url=http://www.catsg.org/cheetah/01_information/1_2_species-information/species-information.htm#Phylogenetic%20history |publisher=IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group |access-date = 6 May 2014 |archive-date = 21 July 2017 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170721022535/http://www.catsg.org/cheetah/01_information/1_2_species-information/species-information.htm#Phylogenetic%20history |url-status = live}}</ref> Since 1927, the king cheetah has been reported five more times in the wild in Zimbabwe, Botswana and northern [[Transvaal Province|Transvaal]]; one was photographed in 1975.<ref name="bottriell">{{cite book |last1=Bottriell |first1=L. G. |title=King Cheetah: The Story of the Quest |year=1987 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nNcUAAAAIAAJ&pg=frontcover |pages=26; 83–96 |publisher=[[Brill Publishers]] |location=Leiden |isbn=978-90-04-08588-6 |access-date=22 May 2020 |archive-date=28 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328013736/https://books.google.com/books?id=nNcUAAAAIAAJ&pg=frontcover |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

In May 1981 two spotted sisters gave birth at the [[De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre]] (South Africa), and each litter contained one king cheetah. Each sister had mated with a wild male from the [[Transvaal Province|Transvaal]] region (where king cheetahs had been recorded). Further king cheetahs were later born at the Centre. They have been known to exist in Zimbabwe, Botswana and northern Transvaal. In 2012 the cause of this alternative coat pattern was found to be a mutation in the gene for transmembrane aminopeptidase{{nbsp}}Q (Taqpep), the same gene responsible for the striped "mackerel" versus blotchy "classic" patterning seen in [[Cat coat genetics|tabby cats]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1 = Kaelin |first1 = C.B. |last2 = Xu |first2 = X. |last3 = Hong |first3 = L.Z. |last4 = David |first4 = V.A. |last5 = McGowan |first5 = K.A. |last6 = Schmidt-Küntzel |first6 = A. |last7 = Roelke |first7 = M.E. |last8 = Pino |first8 = J. |last9 = Pontius |first9 = J.| last10 = Cooper | first10 = G.M. |last11 = Manuel |first11 = H. |last12 = Swanson |first12 = W. F. |last13 = Marker |first13 = L. |last14 = Harper |first14 = C. K. |last15 = van Dyk |first15 = A. |last16 = Yue |first16 = B. |last17 = Mullikin |first17 = J.C. |last18 = Warren |first18 = W.C. |last19 = Eizirik |first19 = E. | last20 = Kos | first20 = L. |last21 = O'Brien |first21 = S.J. |last22 = Barsh |first22 = G.S. |last23 = Menotti-Raymond |first23 = M. |year = 2012 |title = Specifying and sustaining pigmentation patterns in domestic and wild cats |journal = [[Science (journal)|Science]] |volume = 337 |issue = 6101 |pages = 1536–41 |pmid = 22997338 |doi = 10.1126/science.1220893 }}</ref> Hence, genetically the king cheetah is simply a variety of the common cheetah and not a separate species. This case is similar to that of the [[black panther]]s.<ref name="thompson"/> The mutation is [[recessive (genetics)|recessive]], a reason behind the rareness of the mutation. As a result, if two mating cheetahs have the same gene, then a quarter of their offspring can be expected to be king cheetahs.<ref name=wcw/> |

|||

In 1981, two female cheetahs that had mated with a wild male from Transvaal at the [[De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre]] (South Africa) gave birth to one king cheetah each; subsequently, more king cheetahs were born at the centre.<ref name = catsg/> In 2012, the cause of this coat pattern was found to be a mutation in the gene for [[Transmembrane protein|transmembrane]] [[aminopeptidase]] (Taqpep), the same gene responsible for the striped "mackerel" versus blotchy "classic" pattern seen in [[Cat coat genetics|tabby cats]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Aarde |first1=R. J. van |last2=Dyk |first2=A. van |name-list-style=amp |title=Inheritance of the king coat colour pattern in cheetahs ''Acinonyx jubatus'' |journal=Journal of Zoology |date=1986 |volume=209 |issue=4 |pages=573–578 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1986.tb03612.x}}</ref> The appearance is caused by reinforcement of a [[recessive (genetics)|recessive allele]]; hence if two mating cheetahs are [[heterozygosity|heterozygous]] [[genetic carrier|carriers]] of the mutated allele, a quarter of their offspring can be expected to be king cheetahs.<ref name="wcw">{{cite book |last1=Sunquist |first1=F. |last2=Sunquist |first2=M. |name-list-style=amp |title=Wild Cats of the World |date=2002 |publisher=[[The University of Chicago Press]] |location=Chicago |isbn=978-0-226-77999-7 |pages=19–36 |chapter=Cheetah ''Acinonyx jubatus'' (Schreber, 1776) |chapter-url={{Google Books |plainurl=yes |id=hFbJWMh9-OAC |page=19}} }}</ref> |

|||

==Characteristics== |

==Characteristics== |

||

[[File:Cheetah portrait Whipsnade Zoo.jpg|thumb |

[[File:Cheetah portrait Whipsnade Zoo.jpg|thumb|Cheetah portrait showing black "tear marks" running from the corners of the eyes down the side of the nose|alt=Close-up of the face of a cheetah showing black tear marks running from the corners of the eyes down the side of the nose]] |

||

[[File:Cheetah Kruger.jpg|thumbnail|Close view of a cheetah. Note the lightly built, slender body, spotted coat and long tail.|alt=Close full-body view of a cheetah]] |

|||