Occupation of Iraq (2003–2011)

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (August 2008) |

| Occupation of Iraq (2003–2011) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

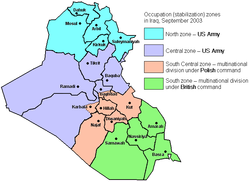

Occupation zones in Iraq as of September 2003 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Coalition: Other Coalition forces |

Mahdi Army Other Insurgent groups | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Coalition ~400,000 current Contractors*~182,000 (118,000 Iraqi, 43,000 Other, 21,000 US [2][3] Kurdish Army 250,000 current New Iraqi Army 180,000 Iraqi Police 79-227,000 |

Sunni Insurgents 70,000 [17] Mahdi Army ~60,000[4][5] al Qaeda/others 1,300+[6] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Iraqi Security Forces (post-Saddam, Coalition allies) Police/military killed: 10,020 (6,490 police and 3,530 Military) See: Casualties of the Iraq War Coalition dead (3,937 US, 143 UK, 136 other): 4,216[7] Coalition wounded (29,978 US, ~350 UK, 295 other): 29,411[8][9] Coalition injured** (28,645 US, 2,436 other): 31,081[7][9] Contractors dead (US 242): 1,025[10][11][12][13] Contractors missing or captured (US 9): 17 Contractors wounded & injured: ~13,000[14] |

10,418 Insurgents Detainees: 21,000[16][17] | ||||||

|

***Total deaths (all excess deaths) Johns Hopkins - As of June 2006: 654,965 (range of 392,979–942,636). 601,027 were violent deaths (31% attributed to Coalition, 24% to others, 46% unknown)[18][19] War-related & criminal violence deaths (all Iraqis) Iraq Health Minister. Through early November 2006: 100,000-150,000[20][21] War-related & criminal violence deaths (civilians) Iraq Body Count - English language media only: 69,045-75,495[22] | |||||||

|

*Contractors (U.S. government) perform "often highly dangerous duties almost identical to those performed by many U.S. troops."[3] **"injured" refers to those casualties reported as injured, diseased, or requiring medical air transport. ***Total deaths include all additional deaths due to increased lawlessness, degraded infrastructure, poorer healthcare, etc. For explanations of the wide variation in casualty estimates, see: Casualties of the conflict in Iraq since 2003 | |||||||

The post-invasion period in Iraq, also known as the Occupation of Iraq,[23]and the Liberation of Iraq[24] followed the 2003 invasion of Iraq by a multinational coalition led by the United States, which overthrew the Ba'ath Party government of Saddam Hussein. This article covers the period starting May 1, 2003, after United States president George W. Bush officially declared the end of major combat operations.

Military occupation

A military occupation was established and run by the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), which later appointed and granted limited powers to an Iraq Interim Governing Council. Troops for the invasion came primarily from the United States, the United Kingdom and Poland, but twenty-nine other nations also provided some troops, and there were varying levels of assistance from Japan and other allied countries. Tens of thousands of private security personnel provided protection of infrastructure, facilities and personnel.

Coalition and allied Iraqi forces have been fighting a stronger-than-expected militant Iraqi insurgency, and the reconstruction of Iraq has been slow. In mid-2004, the direct rule of the CPA was ended and a new "sovereign and independent" Interim Government of Iraq assumed the full responsibility and authority of the state. The CPA and the Governing Council were disbanded on June 28, 2004, and a new transitional constitution came into effect.[25] Sovereignty was transferred to a Governing Council Iraqi interim government led by Iyad Allawi as Iraq's first post-Saddam prime minister; this government was not allowed to make new laws without the approval of the CPA. The Iraqi Interim Government was replaced as a result of the elections which took place in January 2005. A period of negotiations by the elected Iraqi National Assembly followed, which culminated on April 6, 2005 with the selection of, among others, Prime Minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari and President Jalal Talabani. The Prime Minister al-Jaafari led the majority party of the United Iraqi Alliance (UIA), a coalition of the al-Dawa and SCIRI (Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq) parties. Both parties are Tehran backed, and were banned by Saddam Hussein.

Jalal Talabani is the long time leader of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, one of the two main Kurdish parties. The three main Kurdish provinces have extensive autonomy, with their own parliament. They have not experienced any considerable insurgency. Most Kurds welcomed the American invasion, and danced in the streets when Saddam was captured. Iraqi Kurdistan is experiencing an economic boom, with many expatriates returning home to take part in rebuilding the country that was devastated during the rule of Saddam Hussein.[citation needed]

Legal status of the coalition presence

The US dominated multinational forces still exercise considerable power in the country and, with the New Iraqi Army, conduct military operations against the Iraqi insurgency. The role of Iraqi government forces in providing security is increasing.

According to Article 42 of the Hague Convention, "territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army."[26] The International Humanitarian Law Research Initiative states: "the wording of Security Council resolution 1546 . . . indicates that, regardless of how the situation is characterized, international humanitarian law will apply to it."[27]

- There may be situations... where the former occupier will maintain a military presence in the country, with the agreement of the legitimate government under a security arrangement (e.g., U.S. military presence in Japan and Germany). The legality of such agreement and the legitimacy of the national authorities signing it are subject to international recognition, whereby members of the international community re-establish diplomatic and political relations with the national government. In this context, it is in the interest of all the parties involved to maintain a clear regime of occupation until the conditions for stability and peace are created allowing the re-establishment of a legitimate national government. A post-occupation military presence can only be construed in the context of a viable, stable and peaceful situation.[28]

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1546 in 2004 looked forward to the end of the occupation and the assumption of full responsibility and authority by a fully sovereign and independent Interim Government of Iraq.[29] Afterwards, the UN and individual nations established diplomatic relations with the Interim Government and began planning for elections and the writing of a new constitution.

Despite the continuing insurgency, conditions were deemed stable enough to conduct elections, despite the objections of the United States government but pursuant to the insistence of Grand Ayatollah Sistani. John Negroponte, U.S. ambassador to Baghdad, has indicated that the United States government would comply with a United Nations resolution declaring that coalition forces would have to leave if requested by the Iraqi government. "If that's the wish of the government of Iraq, we will comply with those wishes. But no, we haven't been approached on this issue — although obviously we stand prepared to engage the future government on any issue concerning our presence here."[30]

On May 10, 2007, 144 Iraqi Parliamentary lawmakers signed onto a legislative petition calling on the United States to set a timetable for withdrawal.[31] On June 3, 2007, the Iraqi Parliament voted 85 to 59 to require the Iraqi government to consult with Parliament before requesting additional extensions of the UN Security Council Mandate for Coalition operations in Iraq.[32] The current UN mandate under United Nations Security Council Resolution 1790 expires on December 31, 2008.

2003

Fall of Saddam Hussein's regime

On May 1, 2003, President Bush declared the "end of major combat operations" in Iraq, while aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln with a large "Mission Accomplished" banner displayed behind him.

The weeks following the removal of the Saddam Hussein regime were portrayed by American media as generally a euphoric time among the Iraqi populace. New York Post correspondent Jonathan Foreman, reporting from Baghdad in May 2003, wrote that looting was less widespread than reported, and that "the intensity of the population's pro-American enthusiasm is astonishing".[33] There were widespread reports of looting, though much of the looting was directed at former government buildings and other remnants of the Saddam Hussein regime. There were reports of looting of Iraq's archaeological treasures, mostly from the National Museum of Iraq; up to an alleged 170,000 items, worth billions of U.S. dollars:[34] these reports were later revealed to be vastly exaggerated.[35][36] Cities, especially Baghdad, suffered through reductions in electricity, clean water and telephone service from pre-war levels, with shortages that continued through at least the next year.[37]

Insurgency begins

In the summer of 2003, the U.S. military focused on hunting down the remaining leaders of the former regime, culminating in the killing of Saddam's sons Uday Hussein and Qusay Hussein on July 22. In all, over 200 top leaders of the former regime were killed or captured, as well as numerous lesser functionaries and military personnel. However, even as the Ba'ath party organization disintegrated, elements of the secret police and army began forming guerilla units, since in many cases they had simply gone home rather than openly fight the invading forces. These began to focus their attacks around Mosul, Tikrit and Fallujah. In the fall, these units and other elements who called themselves Jihadists began using ambush tactics, suicide bombings, and improvised explosive devices, targeting coalition forces and checkpoints. They favored attacking the unarmored Humvee vehicles, and in November they successfully attacked U.S. rotary aircraft with SA-7 missiles bought on the global black market. On August 19, the UN Headquarters in Baghdad was destroyed in the Canal Hotel Bombing, killing at least 22 people, among them Sérgio Vieira de Mello, Special Representative of the UN Secretary General.

Saddam captured and elections urged

In December, Saddam himself was captured. The provisional government began training a security force intended to defend critical infrastructure, and the U.S. promised over $20 billion in reconstruction aid in the form of credits against Iraq's future oil revenues. At the same time, elements left out of the Iraqi Patriotic Alliance (IPA) began to agitate for elections. Most prominent among these was Ali al-Sistani, Grand Ayatollah in the Shia sect of Islam. The United States and its Coalition Provisional Authority opposed allowing democratic elections at this time, preferring instead to eventually hand over power to an unelected group of Iraqis.[38] More insurgents stepped up their activities. The two most turbulent centers were the area around Fallujah and the poor Shia sections of cities from Baghdad to Basra in the south.

2004

Spring uprisings

In the spring, the United States and the Coalition Provisional Authority decided to confront the rebels with a pair of assaults: one on Fallujah, the center of the "Mohammed's Army of Al-Ansar", and another on Najaf, home of an important mosque, which had become the focal point for the Mahdi Army and its activities. In Fallujah four private security contractors, working for Blackwater USA, were ambushed and killed, and their corpses desecrated. In retaliation a U.S. offensive was begun, but it was soon halted because of the protests by the Iraqi Governing Council and negative media coverage. A truce was negotiated that put a former Baathist general in complete charge of the town. The 1st Armored Division along with the 2nd ACR were then shifted south, because Spanish, Salvadoran, Italian, Ukrainian, and Polish forces were having increasing difficulties retaining control over Nasiriya, Al Kut, and Najaf. The 1st Armored Division and 2nd ACR relieved the Spaniards, Salvadoran, Poles, and Italians, and put down the overt rebellion. At the same time, British forces in Basra were faced with increasing restiveness, and became more selective in the areas they patrolled. In all, April, May and early June represented the bloodiest months of fighting since the end of hostilities. The Iraqi troops who were left in charge of Fallujah after the truce began to disperse and the city fell back under insurgent control. In the April battle for Fallujah, U.S. troops killed about 200 resistance fighters, while 40 Americans died and hundreds were wounded in a fierce battle. U.S. forces then turned their attention to the al Mahdi Army in Najaf.

Transfer of sovereignty

In June 2004, under the auspices of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1546 the Coalition transferred limited sovereignty to a caretaker government, whose first act was to begin the trial of Saddam Hussein. The government began the process of moving towards elections, though the insurgency, and the lack of cohesion within the government itself, led to repeated delays.

Militia leader Muqtada al-Sadr used his grass-roots organization and Mahdi Militia of over a thousand armed men to take control of the streets of Baghdad. The CPA soon realized it had lost control and closed down his popular newspaper. This resulted in mass anti-American demonstrations. The CPA then attempted to arrest al-Sadr on murder charges. He defied the American military by taking refuge in the Holy City of Najaf. Through the months of July and August, a series of skirmishes in and around Najaf culminated with the Imman Ali Mosque itself under siege, only to have a peace deal brokered by al-Sistani in late August.[39] Al-Sadr then declared a national cease fire, and opened negotiations with the American and government forces. His militia was incorporated into the Iraqi security forces and al-Sadr is now a special envoy. This incident was the turning point in the failed American efforts to install Ahmed Chalabi as leader of the interim government. The CPA then put Iyad Allawi in power, ultimately he was only marginally more popular than the convicted felon Chalabi.

The Allawi government, with significant numbers of holdovers from the Coalition Provisional Authority, began to engage in attempts to secure control of the oil infrastructure, the source of Iraq's foreign currency, and control of the major cities of Iraq. The continuing insurgencies, poor state of the Iraqi Army, disorganized condition of police and security forces, as well as the lack of revenue hampered their efforts to assert control. In addition, both former Baathist elements and militant Shia groups engaged in sabotage, terrorism, open rebellion, and establishing their own security zones in all or part of a dozen cities. The Allawi government vowed to crush resistance, using U.S. troops, but at the same time negotiated with Muqtada al-Sadr.

Offensives and counteroffensives

Beginning November 8, American and Iraqi forces invaded the militant stronghold of Fallujah in Operation Phantom Fury, killing and capturing many insurgents. Many rebels were thought to have fled the city before the invasion. U.S.-backed figures put insurgency losses at over 2,000. It was the bloodiest single battle for the U.S. in the war, with 92 Americans dead and several hundred wounded. A video showing the killing of at least one unarmed and wounded man by an American serviceman surfaced, throwing renewed doubt and outrage at the efficiency of the U.S. occupation.[40] The Marine was later cleared of any wrongdoing because the Marines had been warned that the enemy would sometimes feign death and booby-trap bodies as a tactic to lure Marines to their deaths. November was the deadliest month of the occupation for coalition troops, surpassing April.

Another offensive was launched by insurgents during the month of November in Mosul. U.S. forces backed by peshmerga fighters launched a counteroffensive which resulted in the Battle of Mosul (2004). The fighting in Mosul occurred concurrently with the fighting in Fallujah and attributed to the high number of American casualties taken that month.

In December, 14 American soldiers were killed and over a hundred injured when an explosion struck an open-tent mess hall in Mosul, where President Bush had spent Thanksgiving with troops the year before. The explosion is believed to have come from a suicide bomber.

2005

Iraqi elections and aftermath

On January 30, an election for a government to draft a permanent constitution took place. Although some violence and lack of widespread Sunni Arab participation marred the event, most of the eligible Kurd and Shia populace participated. On February 4, Paul Wolfowitz announced that 15,000 U.S. troops whose tours of duty had been extended in order to provide election security would be pulled out of Iraq by the next month.[41] February, March and April proved to be relatively peaceful months compared to the carnage of November and January, with insurgent attacks averaging 30 a day from the average 70.

Hopes for a quick end to an insurgency and a withdrawal of U.S. troops were dashed at the advent of May, Iraq's bloodiest month since the invasion of U.S. forces in March and April 2003. Suicide bombers, believed to be mainly disheartened Iraqi Sunni Arabs, Syrians and Saudis, tore through Iraq. Their targets were often Shia gatherings or civilian concentrations mainly of Shias. As a result, over 700 Iraqi civilians died in that month, as well as 79 U.S. soldiers.

During early and mid-May, the U.S. also launched Operation Matador, an assault by around 1,000 Marines in the ungoverned region of western Iraq. Its goal was the closing of suspected insurgent supply routes of volunteers and material from Syria, and with the fight they received their assumption proved correct. Fighters armed with flak jackets (unseen in the insurgency by this time) and sporting sophisticated tactics met the Marines, eventually inflicting 30 U.S. casualties by the operation's end, and suffering 125 casualties themselves. The Marines succeeded, recapturing the whole region and even fighting insurgents all the way to the Syrian border, where they were forced to stop (Syrian residents living near the border heard the American bombs very clearly during the operation). The vast majority of these armed and trained insurgents quickly dispersed before the U.S. could bring the full force of its firepower on them, as it did in Fallujah.

Announcements and renewed fighting

On August 14, 2005 the Washington Post[42] quoted one anonymous U.S. senior official expressing that "the United States no longer expects to see a model new democracy, a self-supporting oil industry or a society in which the majority of people are free from serious security or economic challenges... 'What we expected to achieve was never realistic given the timetable or what unfolded on the ground'". On September 22, 2005, Prince Saud al-Faisal, the Saudi foreign minister, said that he had warned the Bush administration in recent days that Iraq was hurtling toward disintegration, and that the election planned for December was unlikely to make any difference.[43] U. S. officials immediately made statements rejecting this view.[44]

Constitutional ratification and elections

The National Assembly elected in January had drafted a new constitution to be ratified in a national referendum on October 15, 2005. For ratification, the constitution required a majority of national vote, and could be blocked by a two thirds "no" vote in each of at least three of the 18 governates. In the actual vote, 79% of the voters voted in favor, and there was a two thirds "no" vote in only two governates, both predominantly Sunni. The new Constitution of Iraq was ratified and took effect. Sunni turnout was substantially heavier than for the January elections, but insufficient to block ratification.

Elections for a new Iraqi National Assembly were held under the new constitution on December 15, 2005. This election used a proportional system, with approximately 25% of the seats required to be filled by women. After the election, a coalition government was formed under the leadership of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, with Jalal Talibani as president.

2006

The beginning of that year was marked by government creation talks and continuous anti-coalition and attacks on mainly Shia civilians.

Al-Askari shrine bombing and Sunni-Shia fighting

On February 22, 2006, at 6:55 a.m. local time (0355 UTC) two bombs were set off by five to seven men dressed as personnel of the Iraqi Special forces who entered the Al Askari Mosque during the morning. Explosions occurred at the mosque, effectively destroying its golden dome and severely damaging the mosque. Several men, one wearing a military uniform, had earlier entered the mosque, tied up the guards there and set explosives, resulting in the blast.

Shiites across Iraq expressed their anger by destroying Sunni mosques and killing dozens. Religious leaders of both sides called for calm amid fears the situation could erupt into a long-awaited Sunni-Shia civil war in Iraq.

On March 2 the director of the Baghdad morgue fled Iraq explaining, "7,000 people have been killed by death squads in recent months."[45] The Boston Globe reported that around eight times the number of Iraqis killed by terrorist bombings during March 2006 were killed by sectarian death squads during the same period. A total of 1,313 were killed by sectarian militias while 173 were killed by suicide bombings.[46] The LA Times later reported that about 3,800 Iraqis were killed by sectarian violence in Baghdad alone during the first three months of 2006. During April 2006, morgue numbers show that 1,091 Baghdad residents were killed by sectarian executions.[47]

Insurgencies, frequent terrorist attacks and sectarian violence lead to harsh criticism of US Iraq policy and fears of a failing state and civil war. The concerns were expressed by several US think tanks[48][49][50][51] as well as the US ambassador to Iraq, Zalmay Khalilzad.[52]

In early 2006, a handful of high ranking retired generals begin to demand Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld's resignation due in part to the aforementioned chaos that resulted from his management of the war.

British hand Muthanna province to Iraqis

On July 12, 2006, Iraq took full control of the Muthanna province, marking the first time since the invasion that a province had been handed from foreign troops to the Iraqi government. In a joint statement, the U.S. ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad and the U.S. commander in Iraq, General George Casey, hailed it as a milestone in Iraq's capability to govern and protect itself as a "sovereign nation" and said handovers in other provinces will take place as conditions are achieved. "With this first transition of security responsibility, Muthanna demonstrates the progress Iraq is making toward self- governance", the statement said, adding that "Multi-National Forces will stand ready to provide assistance if needed." At the ceremony marking the event, Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki stated, "It is a great national day that will be registered in the history of Iraq. This step forward will bring happiness to all Iraqis."[53][54]

Forward Operating Base Courage handed over to Nineveh province government

A former presidential compound of Saddam Hussein, dubbed Forward Operating Base Courage by Coalition forces, was handed over to the Nineveh province government on July 20, 2006. The main palace had been home to the 101st Airborne Division Main Command Post, Task Force Olympia CP, and the Task Force Freedom CP. The palace served as the last command post for the Multinational Force-Iraq–Northwest. U.S. soldiers had spent the summer restoring the palace for the eventual handover. Maj. Gen. Thomas R. Turner II, commanding general, Task Force Band of Brothers stated at a ceremony marking the occasion "The turnover of Forward Operating Base Courage is one of the larger efforts towards empowering the Iraqi people and represents an important step in achieving Iraqi self-reliance...The gains made during the past three years demonstrate that the provincial government, the Iraqi Army and the Iraqi Police are increasing their capabilities to take the lead for their nation’s security." Duraid Mohammed Da’ud Abbodi Kashmoula, the Nineveh province governor, stated after being handed the key to the palace "Now this palace will be used to benefit the Iraqi government and its people."[55][56]

British troops leave Camp Abu Naji

On August 24, 2006, Maj. Charlie Burbridge, a British military spokesman, said the last of 1,200 British troops left Camp Abu Naji, just outside Amarah in Iraq's southern Maysan province. Burbridge told Reuters that British troops leaving the base were preparing to head deep into the marshlands along the Iranian border, stating "We are repositioning our forces to focus on border areas and deal with reports of smuggling of weapons and improvised explosive devices from across the border."

The base had been a target for frequent mortar and rocket barrages since being set up in 2003, but Burbridge dismissed suggestions the British had been forced out of Amara while acknowledging the attacks had been one reason for the decision to withdraw, the second being that a static base did not fit with the new operation. "Abu Naji was a bulls-eye in the middle of a dartboard. The attacks were a nuisance and were a contributing factor in our planning", to quit the base, he said, adding "By no longer presenting a static target, we reduce the ability of the militias to strike us..We understand the militias in Maysan province are using this as an example that we have been pushed out of Abu Naji, but that is not true. It was very rare for us to take casualties." Burbridge stated that Iraqi security forces would now be responsible for day-to-day security in Maysan but stressed that the British had not yet handed over complete control to them.

Muqtada al-Sadr called the departure the first expulsion of U.S.-led coalition forces from an Iraqi urban center. A message from al-Sadr's office that played on car-mounted speakers throughout Amarah exclaimed "This is the first Iraqi city that has kicked out the occupier...We have to celebrate this occasion!" A crowd of as many as 5,000 people, including hundreds armed with AK-47 assault rifles, ransacked Camp Abu Naji immediately after the last British soldier had departed despite the presence of a 450-member Iraqi army brigade meant to guard the base. The looting, which lasted from about 10 a.m. to early evening, turned violent at about noon when individuals in the mob shot at the base. The Iraqi troops asked the province's governor for permission to return fire, a decision the British military highlighted as evidence of the security force's training. "It demonstrated that they understand the importance of civilian primacy, that the government -- and not the military -- is in charge", Burbridge said in a phone interview with the Washington Post. Injuries were reported on both sides, but no one was killed. Burbridge attributed the looting to economic factors rather than malice, stating "The people of Amarah -- many of whom are extremely poor -- saw what they believed to be a bit of an Aladdin's cave inside." Residents of Amarah, however, told the Post that antipathy toward the British was strong. "The looters stole everything -- even the bricks...They almost leveled the whole base to the ground", said Ahmed Mohammed Abdul Latief, 20, a student at Maysan University.[57][58][59]

Situation in and around Baghdad

A US general says on August 28, 2006 violence has fallen in Baghdad by nearly a half since July, although he acknowledged a spike in bombings in the past 48 hours. "Insurgents and terrorists are hitting back in an attempt to offset the success of the Iraqi government and its security forces", Maj Gen William Caldwell told reporters. After meeting Iraqi Defence Minister Abdul-Qader Mohammed Jassim al-Mifarji, UK Defence Minister Des Browne said Iraq was moving forward. "Each time I come, I see more progress", he said.[60]

The American military command acknowledged in the week of October 16, 2006 that it was considering an overhaul of its latest security plan for Baghdad, where three months of intensive American-led sweeps had failed to curb violence by Sunni Arab-led insurgents and Shiite and Sunni militias.[61]

Numerous car and roadside bombs rocked the capital November 9, 2006 morning: In the Karrada district, a car bomb killed six and wounded 28 others. Another car bomb killed seven and wounded another 27 in the northern Qahira neighborhood. In South Baghdad, a mortar then a suicide car bomber killed seven and wounded 27 others near the Mishin bazaar. Near the college of Fine Arts in north-central Baghdad, a car bomb targeting an Iraqi patrol killed three and wounded six others. Two policemen were injured when they tried to dismantle a car bomb in the Zayouna district. A car bomb on Palestine Street in northeastern Baghdad meant for an Iraqi patrol killed one soldier but also wounded four civilians. Yet another car bomb in southern Baghdad wounded three people. And another car bomb near a passport services building in a northern neighborhood killed 2 people and wounded 7 others.

A roadside bomb in central Baghdad killed two and wounded 26 others. A police patrol was blasted by a roadside bomb near a petrol station; four were killed in the explosion. Another four people were wounded in the New Baghdad neighborhood by yet another roadside bomb. A bomb hidden in a sack exploded in Tayern square killing three and wounding 19. Another bomb in the Doura neighborhood killed one and wounded three. Mortars fell in Kadmiyah killing one woman and injuring eight people, and in Bayaladat where four were wounded.

Also in the capital, a group of laborers were kidnapped November 9, 2006 morning; five bodies were recovered later in the Doura neighborhood, but at least one other body was found in Baghdad November 9, 2006. Gunmen killed a police colonel and his driver in eastern Baghdad. And just outside of town, police arrested two people in a raid and discovered one corpse.[62]

November 10, 2006, Iraqi police recovered 18 bullet-riddled bodies in various neighborhoods around the capital. Police were unable to identify the bodies.

November 11, 2006, two bombs planted in an outdoor market in central Baghdad exploded around noon, killing six and wounded 32 people. A car bomb and a roadside bomb were detonated five minutes apart in the market, which is in an area close to Baghdad's main commercial center. The U.S. military said it has put up a $50,000 reward for anyone who helps find an American soldier kidnapped in Baghdad. The 42-year-old Army Reserve specialist, Ahmed K. Altaie, was abducted on October 23 when he left the Green Zone, the heavily fortified section where the United States maintains its headquarters, to visit his Iraqi wife and family.

A suicide bomber killed 25 Iraqis and wounded 45 November 12, 2006 morning outside the national police headquarters' recruitment center in western Baghdad, an emergency police official said. They were among dozens of men waiting to join the police force in the Qadessiya district when a suicide bomber detonated an explosives belt. In central Baghdad, a car bomb and roadside bomb killed four Iraqi civilians and wounded 10 near the Interior Ministry complex. And in the Karrada district of central Baghdad, one Iraqi was killed and five were wounded when a car bomb exploded near an outdoor market November 12, 2006 morning. Gunmen shot dead an Iraqi officer with the new Iraqi intelligence system as he was walking towards his parked car in the southwestern Baghdad neighborhood of Bayaa. Two civilians were killed and four more were wounded when a roadside bomb hit a car in the eastern Baghdad neighborhood of Zayuna.[63]

Violent incidents in other cities

- Suwayrah: Four bodies were recovered from the Tigris River. Three of them were in police uniforms.

- Amarah: A roadside bomb killed one and wounded three others in Amarah. Gunmen also shot dead a suspected former member of the Fedayeen paramilitary.

- Muqdadiyah: Gunmen stormed a primary school and killed three: a guard, a policeman and a student.

- Tal Afar: A roadside bomb in Tal Afar killed four, including a policeman, and wounded eight other people. Two policemen were killed and four civilians were injured when a rocket landed in a residential neighborhood.

- Mosul: Six people were shot dead, including one policeman.

- Latifiya: Four bodies, bound and gagged, were discovered.

- Baqubah: Eight people were killed in different incidents.

- Latifiya: Gunmen killed a truck driver and kidnapped 11 Iraqis after stopping four vehicles at a fake checkpoint south of the capital. At the fake checkpoint in Latifiya, about 25 miles (40 km) south of Baghdad, gunmen took the four vehicles -- three minibuses and a truck -- along with the kidnapped Iraqis. The Iraqis -- 11 men and three women -- were driving from Diwaniya to Baghdad for shopping when they were stopped. The gunmen left the three women and kidnapped the 11 men, the official said.

- Baqubah: North of the capital near Baquba, a suicide car bomb explosion killed two people at the main gate of a police station in Zaghanya town.

Al-Qaeda

Saddam Hussein was accused of hiding Al-Qaeda members in Iraq, that was one of the justifications for the war with Iraq, however that claim had no merits since only few Al-Qaeda members were found hiding in Iraq before the invasion, all were of lower standings. Saddam was not a fundamentalist, he was a secular leader, something terrorist groups do not approve of a Muslim leader.

On September 3, 2006, Iraq says it has arrested the country's second most senior figure in Al-Qaeda, "severely wounding" an organization the US military says is spreading sectarian violence that could bring civil war. The National Security Adviser Mowaffak al-Rubaie summoned reporters to a hastily arranged news conference to announce that al Qaeda leader Hamid Juma Faris al-Suaidi had been seized some days ago. Hitherto little heard of, and also known as Abu Humam or Abu Rana, Suaidi was captured hiding in a building with a group of followers. "Al-Qaeda in Iraq is severely wounded", Rubaie said. He said Suaidi had been involved in ordering the bombing of the Shi'ite shrine in Samarra in February 2006 that unleashed the wave of tit-for-tat killings now threatening civil war. Iraqi officials blame Al-Qaeda for the attack. The group denies it. Rubaie did not give Suaidi's nationality. He said he had been tracked to the same area north of Baghdad where US forces killed Al-Qaeda's leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in June 2006. "He was hiding in a building used by families. He wanted to use children and women as human shields", Rubaie said. Little is publicly known about Suaidi. Rubaie called him the deputy of Abu Ayyub al-Masri, a shadowy figure, probably Egyptian, who took over the Sunni Islamist group from Zarqawi.[64]

The US military says Al-Qaeda is a "prime instigator" of the violence between Iraq's Sunni minority and Shi'ite majority but that U.S. and Iraqi operations have "severely disrupted" it.[65]

Security handover to Iraq's army

A Zogby poll in February 2006 determined that a majority of U.S. troops serving in Iraq think that the U.S. should exit the country within a year, i.e. before February 2007.[66] The poll found:

- "An overwhelming majority of 72% of American troops serving in Iraq think the U.S. should exit the country within the next year, and nearly one in four say the troops should leave immediately"

- "89% of reserves and 82% of those in the National Guard said the U.S. should leave Iraq within a year, 58% of Marines think so."

Washington claims to be eager for Iraq's army to take over security and pave the way for a withdrawal of its 140,000 troops. But a handover ceremony on September 2, 2006 was postponed at the last minute, first to September 3, 2006 , then indefinitely, after a dispute emerged between the government and Washington over the wording of a document outlining their armies' new working relationship. "There are some disputes", an Iraqi government source said. "We want thorough control and the freedom to make decisions independently." US spokesman Lieutenant Colonel Barry Johnson played down any arguments and expected a signing soon: "It is embarrassing but it was decided it was better not to sign the document." Practically, US troops remain the dominant force. Their tanks entered the southern, Shi'ite city of Diwaniya on September 3, 2006 . The show of force came a week after Shi'ite militiamen killed 20 Iraqi troops in a battle that highlighted violent power struggles between rival Shi'ite factions in the oil-rich south.[65]

Abu Ghraib

On September 2, 2006, the Abu Ghraib prison was formally handed over to Iraq's government. The formal transfer was conducted between Major General Jack Gardner, Commander of Task Force 134, and representatives of the Iraqi Ministry of Justice and the Iraqi army.[67]

Iraqi government takes control of the 8th Iraqi Army Division

On September 7, 2006, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki signed a document taking control of Iraq's small naval and air forces and the 8th Iraqi Army Division, based in the south. At a ceremony marking the occasion, Gen. George Casey, the top U.S. commander in Iraq stated "From today forward, the Iraqi military responsibilities will be increasingly conceived and led by Iraqis." Previously, the U.S.-led Multinational Forces in Iraq, commanded by Casey, gave orders to the Iraqi armed forces through a joint American-Iraqi headquarters and chain of command. Senior U.S. and coalition officers controlled army divisions but smaller units were commanded by Iraqi officers. After the handover, the chain of command flows directly from the prime minister in his role as Iraqi commander in chief, through his Defense Ministry to an Iraqi military headquarters. From there, the orders go to Iraqi units on the ground. The other nine Iraqi division remain under U.S. command, with authority gradually being transeferred. U.S. military officials said there was no specific timetable for the transition. U.S. military spokesman Maj. Gen. William Caldwell said it would be up to al-Maliki to decide "how rapidly he wants to move along with assuming control...They can move as rapidly thereafter as they want. I know, conceptually, they've talked about perhaps two divisions a month." The 8th Division's commander, Brig. Gen. Othman al-Farhoud, told The Associated Press his forces still needed support from the U.S.-led coalition for things such as medical assistance, storage facilities and air support, stating "In my opinion, it will take time before his division was completely self-sufficient."[68]

Anbar province reported as politically "lost" to U. S. and Iraqi government

On September 11, 2006, it transpired that Colonel Peter Devlin, chief of intelligence for the Marine Corps in Iraq, had filed a secret report, described by those who have seen it as saying that the U.S. and the Iraqi government have been defeated politically in Anbar province. According to The Washington Post, an unnamed Defense Department source described Devlin as saying "there are no functioning Iraqi government institutions in Anbar, leaving a vacuum that has been filled by the insurgent group al-Qaeda in Iraq, which has become the province's most significant political force." The Post said that Devlin is a very experienced intelligence officer whose report was being taken seriously.[69]

The next day, Major General Richard Zilmer, commander of the Marines in Iraq, stated: "We are winning this war... I have never heard any discussion about the war being lost before this weekend."[70]

Iraq takes over security responsibility in southern Dhi Qar province

On September 21, 2006, Italian troops handed security control of the Dhi Qar province to Iraqi forces, making Dhi Qar the second of the country's 18 provinces to come under complete local control. At a ceremony in Nasiriyah marking the handover, Italian Defense Minister Arturo Parisi told Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki "The Italian contingent is going back. The mission is accomplished - the security of the province is in your hands." Italy has about 1,600 troops in the country, mostly in Nasiriyah, and that force is expected to be withdrawn by year’s end. Dhi Qar is populated mainly by Shiite Muslims and has not experienced the sectarian violence that has plagued other provinces of Iraq.[71]

Iraq takes over security responsibilities in Najaf province

On December 20, 2006, U.S. forces handed over control of the southern province of Najaf to Iraqi security forces. Najaf is the third Iraqi province to be turned over to Iraqi forces, but the first such handover by U.S. troops. U.S. forces will remain on standby in case the security situation deteriorates. "If we don't handle the responsibility, history will destroy us", Iraq's national security adviser, Mouwafak al-Rubaie, said at a ceremony in a stadium in Najaf city, the provincial capital. "Transferring responsibility is an indication of the increased capacity of the Iraqi police and the Iraqi army", Maj. Gen. Kurt Cichowski said at the ceremony.[72][73]

2007

2008

Participating nations

As of September, 2006, there were 21 countries with military forces stationed in Iraq. These were Albania, Armenia, Australia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, El Salvador, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Mongolia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, United Kingdom, and the United States. Fiji is also present but under the United Nations banner.[74]

Well over 80% of the forces occupying Iraq are American. As of September 2006, there were an estimated 145,000 U.S. troops in Iraq.[75] The next largest contingent is that of the United Kingdom, with just under 9,000.[74] There are also approximately 20,000 private security contractors of different nationalities under various employers.

Casualties

Estimates of the casualties from the Iraq War (beginning with the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the ensuing occupation and insurgency and civil war) have come in several forms, and those estimates of different types of Iraq War casualties vary greatly.

Estimating war-related deaths poses many challenges.[76][77] Experts distinguish between population-based studies, which extrapolate from random samples of the population, and body counts, which tally reported deaths and likely significantly underestimate casualties.[78] Population-based studies produce estimates of the number of Iraq War casualties ranging from 151,000 violent deaths as of June 2006 (per the Iraq Family Health Survey) to 1,033,000 excess deaths (per the 2007 Opinion Research Business (ORB) survey). Other survey-based studies covering different time-spans find 461,000 total deaths (over 60% of them violent) as of June 2011 (per PLOS Medicine 2013), and 655,000 total deaths (over 90% of them violent) as of June 2006 (per the 2006 Lancet study). Body counts counted at least 110,600 violent deaths as of April 2009 (Associated Press). The Iraq Body Count project documents 186,901 – 210,296 violent civilian deaths in their table. All estimates of Iraq War casualties are disputed.[79][80]

Tables

The tables below summarize reports on Iraqi casualty figures.

Scientific surveys:

| Source | Estimated violent deaths | Time period |

|---|---|---|

| Iraq Family Health Survey | 151,000 violent deaths | March 2003 to June 2006 |

| Lancet survey | 601,027 violent deaths out of 654,965 excess deaths | March 2003 to June 2006 |

| PLOS Medicine Survey[79] | 460,000 deaths in Iraq as direct or indirect result of the war including more than 60% of deaths directly attributable to violence. | March 2003 to June 2011 |

Body counts:

| Source | Documented deaths from violence | Time period |

|---|---|---|

| Associated Press | 110,600 violent deaths.[81][82] | March 2003 to April 2009 |

| Iraq Body Count project | 186,901 – 210,296 civilian deaths from violence.[83] | March 2003 onwards |

| Classified Iraq War Logs[84][85][86][87] | 109,032 deaths including 66,081 civilian deaths.[88][89] | January 2004 to December 2009 |

Overview: Iraqi death estimates by source Summary of casualties of the Iraq War. Possible estimates on the number of people killed in the invasion and occupation of Iraq vary widely,[90] and are highly disputed. Estimates of casualties below include both the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the following Post-invasion Iraq, 2003–present.

|

Iraq war logs |

Classified US military documents released by WikiLeaks in October 2010, record Iraqi and Coalition military deaths between January 2004 and December 2009.[84][85][86][87][91][92] The documents record 109,032 deaths broken down into "Civilian" (66,081 deaths), "Host Nation" (15,196 deaths),"Enemy" (23,984 deaths), and "Friendly" (3,771 deaths).[89][93] |

|

Iraqi Health Ministry |

The Health Ministry of the Iraqi government recorded 87,215 Iraqi violent deaths between January 1, 2005, and February 28, 2009. The data was in the form of a list of yearly totals for death certificates issued for violent deaths by hospitals and morgues. The official who provided the data told the Associated Press said the ministry does not have figures for the first two years of the war, and estimated the actual number of deaths at 10 to 20 percent higher because of thousands who are still missing and civilians who were buried in the chaos of war without official records.[81][82] |

|

The Associated Press |

Associated Press stated that more than 110,600 Iraqis had been killed since the start of the war to April 2009. This number is per the Health Ministry tally of 87,215 covering January 1, 2005, to February 28, 2009 combined with counts of casualties for 2003–2004, and after February 29, 2009, from hospital sources and media reports.[81][82] For more info see farther down at The Associated Press and Health Ministry (2009). |

|

Iraq Body Count |

The Iraq Body Count project (IBC) figure of documented civilian deaths from violence is 183,535 – 206,107 through April 2019. This includes reported civilian deaths due to Coalition and insurgent military action, sectarian violence and increased criminal violence.[83] The IBC site states: "many deaths will probably go unreported or unrecorded by officials and media."[94] |

|

Iraq Family Health Survey |

Iraq Family Health Survey for the World Health Organization.[95][96] On January 9, 2008, the World Health Organization reported the results of the "Iraq Family Health Survey" published in The New England Journal of Medicine.[97] The study surveyed 9,345 households across Iraq and estimated 151,000 deaths due to violence (95% uncertainty range, 104,000 to 223,000) from March 2003 through June 2006. Employees of the Iraqi Health Ministry carried out the survey.[98][99][100] See also farther down: Iraq Family Health Survey (IFHS, 2008). |

|

Opinion Research Business |

Opinion Research Business (ORB) poll conducted August 12–19, 2007, estimated 1,033,000 violent deaths due to the Iraq War. The range given was 946,000 to 1,120,000 deaths. A nationally representative sample of approximately 2,000 Iraqi adults answered whether any members of their household (living under their roof) were killed due to the Iraq War. 22% of the respondents had lost one or more household members. ORB reported that "48% died from a gunshot wound, 20% from the impact of a car bomb, 9% from aerial bombardment, 6% as a result of an accident and 6% from another blast/ordnance."[101][102][103][104][105] |

|

United Nations |

The United Nations reported that 34,452 violent deaths occurred in 2006, based on data from morgues, hospitals, and municipal authorities across Iraq.[106] |

|

Lancet studies |

The Lancet study's figure of 654,965 excess deaths through the end of June 2006 is based on household survey data. The estimate is for all excess violent and nonviolent deaths. That also includes those due to increased lawlessness, degraded infrastructure, poorer healthcare, etc. 601,027 deaths (range of 426,369 to 793,663 using a 95% confidence interval) were estimated to be due to violence. 31% of those were attributed to the Coalition, 24% to others, 46% unknown. The causes of violent deaths were gunshot (56%), car bomb (13%), other explosion/ordnance (14%), airstrike (13%), accident (2%), unknown (2%). A copy of a death certificate was available for a high proportion of the reported deaths (92% of those households asked to produce one).[107][108][109] |

|

PLOS Medicine Study |

The PLOS Medicine study's figure of approximately 460,000 excess deaths through the end of June 2011 is based on household survey data including more than 60% of deaths directly attributable to violence. The estimate is for all excess violent and nonviolent deaths. That also includes those due to increased lawlessness, degraded infrastructure, poorer healthcare, etc. 405,000 deaths (range of 48,000 to 751,000 using a 95% confidence interval) were estimated as excess deaths attributable to the conflict. They estimated at least 55,000 additional deaths occurred that the survey missed, as the families had migrated out of Iraq. The survey found that more than 60% of excess deaths were caused by violence, with the rest caused indirectly by the war, through degradation of infrastructure and similar causes. The survey notes that although car bombs received more significant press internationally, gunshot wounds were responsible for the majority (63%) of violent deaths. The study also estimated that 35% of violent deaths were attributed to the Coalition, and 32% to militias. Cardiovascular conditions accounted for about half (47%) of nonviolent deaths, chronic illnesses 11%, infant or childhood deaths other than injuries 12.4%, non-war injuries 11%, and cancer 8%.[79] |

|

Ali al-Shemari (previous Iraqi Health Minister) |

Concerning war-related deaths (civilian and non-civilian), and deaths from criminal gangs, Iraq's Health Minister Ali al-Shemari said that since the March 2003 invasion between 100,000 and 150,000 Iraqis had been killed.[21] "Al-Shemari said on Thursday [November 9, 2006] that he based his figure on an estimate of 100 bodies per day brought to morgues and hospitals – though such a calculation would come out closer to 130,000 in total."[20] For more info see farther down at Iraq Health Minister estimate in November 2006. |

|

268,000 - 295,000 people were killed in violence in the Iraq war from March 2003 - Oct. 2018, including 182,272 - 204,575 civilians (using Iraq Body Count's figures), according to the findings of the Costs of War Project, a team of 35 scholars, legal experts, human rights practitioners, and physicians, assembled by Brown University and the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, "about the costs of the post-9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the related violence in Pakistan and Syria." The civilian violent death numbers are "surely an underestimate."[110][111][112][113] |

Overview: Death estimates by group

|

Iraqi Security Forces (aligned with Coalition) |

From June 2003, through December 31, 2010, there have been 16,623 Iraqi military and police killed based on several estimates.[114] The Iraq Index of the Brookings Institution keeps a running total of ISF casualties.[115] There is also a breakdown of ISF casualties at the iCasualties.org website.[116] |

|

Iraqi insurgents |

From June 2003, through September 30, 2011, there have been 26,320-27,000+ Iraqi insurgents killed based on several estimates.[117] |

|

Media and aid workers |

136 journalists and 51 media support workers were killed on duty according to the numbers listed on source pages on February 24, 2009.[118][119][120] (See Category:Journalists killed while covering the Iraq War.) 94 aid workers have been killed according to a November 21, 2007, Reuters article.[121][122] |

|

U.S. armed forces |

As of July 19, 2021, according to the U.S. Department of Defense casualty website, there were 4,431 total deaths (including both killed in action and non-hostile) and 31,994 wounded in action (WIA) as a result of the Iraq War. As a part of Operation New Dawn, which was initiated on September 1, 2010, there were 74 total deaths (including KIA and non-hostile) and 298 WIA.[124] See the references for a breakdown of the wounded, injured, ill, those returned to duty (RTD), those requiring medical air transport, non-hostile-related medical air transports, non-hostile injuries, diseases, or other medical reasons.[124][7][125][126][127][128] |

|

Coalition deaths by hostile fire |

As of 23 October 2011[update], hostile-fire deaths accounted for 3,777 of the 4,799 total coalition military deaths.[129] |

|

Armed forces of other coalition countries |

See Multinational force in Iraq. As of 24 February 2009[update], there were 318 deaths from the armed forces of other Coalition nations. 179 UK deaths and 139 deaths from other nations. Breakdown:[7][125][130]

|

|

Contractors |

Contractors. At least 1,487 deaths between March 2003 and June 2011 according to the list of private contractor deaths in Iraq. 245 of those are from the U.S.[131][132][133][134][135] Contractors are "Americans, Iraqis and workers from more than three dozen other countries."[136] 10,569 wounded or injured.[131] Contractors "cook meals, do laundry, repair infrastructure, translate documents, analyze intelligence, guard prisoners, protect military convoys, deliver water in the heavily fortified Green Zone and stand sentry at buildings – often highly dangerous duties almost identical to those performed by many U.S. troops."[137] A July 4, 2007, Los Angeles Times article reported 182,000 employees of U.S.-government-funded contractors and subcontractors (118,000 Iraqi, 43,000 other, 21,000 U.S.).[132][138] |

Overview: Iraqi injury estimates by source

|

Iraqi Human Rights Ministry |

The Human Rights Ministry of the Iraqi government recorded 250,000 Iraqi injuries between 2003 and 2012.[139] The ministry had earlier reported that 147,195 injuries were recorded for the period 2004–2008.[140] |

|

Iraqi Government |

Iraqi Government spokesman Ali al-Dabbagh reported that 239,133 Iraqi injuries were recorded by the government between 2004 and 2011.[141] |

|

Iraq war logs |

Classified US military documents released by WikiLeaks in October 2010, recorded 176,382 injuries, including 99,163 civilian injuries between January 2004 and December 2009.[142] |

|

Iraq Body Count |

The Iraq Body Count project reported that there were at least 20,000 civilian injuries in the earliest months of the war between March and July 2003.[143] A follow-up report noted that at least 42,500 civilians were reported wounded in the first two years of the war between March 2003 and March 2005.[144] |

|

UN Assistance Mission for Iraq |

The United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) reported that there were 36,685 Iraqi injuries during the year 2006.[145] |

|

Iraqi Health Ministry |

The Health Ministry of the Iraqi government reported that 38,609 Iraqi injuries had occurred during the year 2007, based on statistics derived from official Iraqi health departments' records. Baghdad had the highest number of injuries (18,335), followed by Nineveh (6,217), Basra (1,387) and Kirkuk (655).[146] |

Additional statistics for the Iraq War

- Iraqis:

- Deadliest single insurgent bombings:[147]

- August 14, 2007. Truck bombs – 2007 Yazidi communities bombings (in northwestern Iraq):

- 796 killed.

- August 14, 2007. Truck bombs – 2007 Yazidi communities bombings (in northwestern Iraq):

- Other deadly days:

- November 23, 2006, (281 killed) and April 18, 2007, (233 killed):

- "4 bombings in Baghdad kill at least 183. ... Nationwide, the number of people killed or found dead on Wednesday [, April 18, 2007, ] was 233, which was the second deadliest day in Iraq since Associated Press began keeping records in May 2005. Five car bombings, mortar rounds and other attacks killed 281 people across Iraq on November 23, 2006, according to the AP count."[148]

- November 23, 2006, (281 killed) and April 18, 2007, (233 killed):

- As of January 12, 2007, 500 U.S. troops have undergone amputations due to the Iraq War. Toes and fingers are not counted.[149]

- As of September 30, 2006, 725 American troops have had limbs amputated from wounds received in Iraq and Afghanistan.[150]

- A 2006 study by the Walter Reed Medical Center, which serves more critically injured soldiers than most VA hospitals, concluded that 62 percent of patients there had suffered a brain injury.[151]

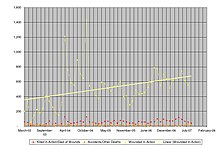

- In March 2003, U.S. military personnel were wounded in action at a rate averaging about 350 per month. As of September 2007, this rate has increased to about 675 per month.[128]

- U.S. military: number unknown.

- An October 18, 2005, USA Today article reports:

- "More than one in four U.S. troops have come home from the Iraq war with health problems that require medical or mental health treatment, according to The Pentagon's first detailed screening of service members leaving a war zone."[152]

- An October 18, 2005, USA Today article reports:

- Iraqi combatants: number unknown

- As of November 4, 2006, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that 1.8 million Iraqis had been displaced to neighboring countries, and 1.6 million were displaced internally, with nearly 100,000 Iraqis fleeing to Syria and Jordan each month.[153]

Iraqi invasion casualties

Franks reportedly estimated soon after the invasion that there had been 30,000 Iraqi casualties as of April 9, 2003.[154] That number comes from the transcript of an October 2003 interview of U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld with journalist Bob Woodward. But neither could remember the number clearly, nor whether it was just for deaths, or both deaths and wounded.

A May 28, 2003, Guardian article reported that "Extrapolating from the death-rates of between 3% and 10% found in the units around Baghdad, one reaches a toll of between 13,500 and 45,000 dead among troops and paramilitaries."[155]

An October 20, 2003, study by the Project on Defense Alternatives at Commonwealth Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, estimated that for March 19, 2003, to April 30, 2003, the "probable death of approximately 11,000 to 15,000 Iraqis, including approximately 3,200 to 4,300 civilian noncombatants."[156][157]

The Iraq Body Count project (IBC) documented a higher number of civilian deaths up to the end of the major combat phase (May 1, 2003). In a 2005 report,[158] using updated information, the IBC reported that 7,299 civilians are documented to have been killed, primarily by U.S. air and ground forces. There were 17,338 civilian injuries inflicted up to May 1, 2003. The IBC says its figures are probably underestimates because: "many deaths will probably go unreported or unrecorded by officials and media."[94]

Iraqi civilian casualties

Iraq Body Count project (IBC)

An independent British-American group, the Iraq Body Count project (IBC project) compiles reported Iraqi civilian deaths resulting from war since the 2003 invasion and ensuing insurgency and civil war, including those caused directly by coalition military action, Iraqi military actions, the Iraqi insurgency, and those resulting from excess crime. The IBC maintains that the occupying authority has a responsibility to prevent these deaths under international law.

The IBC project has recorded a range of at least 185,194 – 208,167 total violent civilian deaths through June 2020 in their database.[83][94] The Iraq Body Count (IBC) project records its numbers based on a "comprehensive survey of commercial media and NGO-based reports, along with official records that have been released into the public sphere. Reports range from specific, incident based accounts to figures from hospitals, morgues, and other documentary data-gathering agencies." The IBC was also given access to the WikiLeaks disclosures of the Iraq War Logs.[84][159]

Iraq Body Count project data shows that the type of attack that resulted in the most civilian deaths was execution after abduction or capture. These accounted for 33% of civilian deaths and 29% of these deaths involved torture. The following most common causes of death were small arms gunfire at 20%, suicide bombs at 14%, vehicle bombs at 9%, roadside bombs at 5%, and air attacks at 5%.[160]

The IBC project, reported that by the end of the major combat phase of the invasion period up to April 30, 2003, 7,419 civilians had been killed, primarily by U.S. air-and-ground forces.[83][158]

The IBC project released a report detailing the deaths it recorded between March 2003 and March 2005[158] in which it recorded 24,865 civilian deaths. The report says the U.S. and its allies were responsible for the largest share (37%) with 9,270 deaths. The remaining deaths were attributed to anti-occupation forces (9%), crime (36%) and unknown agents (11%). It also lists the primary sources used by the media – mortuaries, medics, Iraqi officials, eyewitnesses, police, relatives, U.S.-coalition, journalists, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), friends/associates and other.

According to a 2010 assessment by John Sloboda, director of Iraq Body Count, 150,000 people including 122,000 civilians were killed in the Iraq War with U.S. and Coalition forces responsible for at least 22,668 insurgents as well as 13,807 civilians, with the rest of the civilians killed by insurgents, militias, or terrorists.[161]

The IBC project has been criticized by some, including scholars, who believe it counts only a small percentage of the number of actual deaths because of its reliance on media sources.[105][162][163][164][165] The IBC project's director, John Sloboda, has stated, "We've always said our work is an undercount, you can't possibly expect that a media-based analysis will get all the deaths."[166] However, the IBC project rejects many of these criticisms as exaggerated or misinformed.[167]

According to a 2013 Lancet article, the Iraq Body Count is "a non-peer-reviewed but innovative online and media-centred approach that passively counted non-combatant civilian deaths as they were recorded in the media and available morgue reports. In passive surveillance no special effort is made to find those deaths that go unreported. The volunteer staff collecting data for the IBC have risked criticism that their data are inherently biased because of scarcity or absence of independent verification, variation in original sources of information, and underestimation of mortality from violence... In research circles, random cross-sectional cluster sampling survey methods are deemed to be a more rigorous epidemiological method in conflict settings."[168]

Civilian deaths by perpetrator

In 2011, the IBC published data in PLOS Medicine on 2003-2008 civilian deaths in Iraq by perpetrator and cause of death. The study broke down civilian deaths by perpetrator into the following categories:[169]

- 74% unidentified perpetrator: defined as "those who target civilians (i.e., no identifiable military target is present), while appearing indistinguishable from civilians: for example, a suicide bomber disguised as a civilian in a market. Unknown (i.e., unidentified) perpetrators in Iraq include sectarian combatants and Anti-Coalition combatants who maintain a civilian appearance while targeting civilians."

- 11% anti-coalition forces: defined as "un-uniformed combatants identified by attacks on coalition targets" during the event. Anti-Coalition combatants in the event of targeting purely civilians would instead be classed under the "unidentified perpetrator" category.

- 12% coalition forces: identified by uniforms or use of air attacks.

IBC table of violent civilian deaths

Following are the yearly IBC Project violent civilian death totals, broken down by month from the beginning of 2003. Table below is copied irregularly from the source page, and is soon out-of-date as data is continually updated at the source. As of June 12, 2023 the top of the IBC database page with the table says 186,901 – 210,296 "Documented civilian deaths from violence". That page also says: "Gaps in recording and reporting suggest that even our highest totals to date may be missing many civilian deaths from violence."[83]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Yearly totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 3 | 2 | 3986 | 3448 | 545 | 597 | 646 | 833 | 566 | 515 | 487 | 524 | 12,152 |

| 2004 | 610 | 663 | 1004 | 1303 | 655 | 910 | 834 | 878 | 1042 | 1033 | 1676 | 1129 | 11,737 |

| 2005 | 1222 | 1297 | 905 | 1145 | 1396 | 1347 | 1536 | 2352 | 1444 | 1311 | 1487 | 1141 | 16,583 |

| 2006 | 1546 | 1579 | 1957 | 1805 | 2279 | 2594 | 3298 | 2865 | 2567 | 3041 | 3095 | 2900 | 29,526 |

| 2007 | 3035 | 2680 | 2728 | 2573 | 2854 | 2219 | 2702 | 2483 | 1391 | 1326 | 1124 | 997 | 26,112 |

| 2008 | 861 | 1093 | 1669 | 1317 | 915 | 755 | 640 | 704 | 612 | 594 | 540 | 586 | 10,286 |

| 2009 | 372 | 409 | 438 | 590 | 428 | 564 | 431 | 653 | 352 | 441 | 226 | 478 | 5,382 |

| 2010 | 267 | 305 | 336 | 385 | 387 | 385 | 488 | 520 | 254 | 315 | 307 | 218 | 4,167 |

| 2011 | 389 | 254 | 311 | 289 | 381 | 386 | 308 | 401 | 397 | 366 | 288 | 392 | 4,162 |

| 2012 | 531 | 356 | 377 | 392 | 304 | 529 | 469 | 422 | 400 | 290 | 253 | 299 | 4,622 |

| 2013 | 357 | 360 | 403 | 545 | 888 | 659 | 1145 | 1013 | 1306 | 1180 | 870 | 1126 | 9,852 |

| 2014 | 1097 | 972 | 1029 | 1037 | 1100 | 4088 | 1580 | 3340 | 1474 | 1738 | 1436 | 1327 | 20,218 |

| 2015 | 1490 | 1625 | 1105 | 2013 | 1295 | 1355 | 1845 | 1991 | 1445 | 1297 | 1021 | 1096 | 17,578 |

| 2016 | 1374 | 1258 | 1459 | 1192 | 1276 | 1405 | 1280 | 1375 | 935 | 1970 | 1738 | 1131 | 16,393 |

| 2017 | 1119 | 982 | 1918 | 1816 | 1871 | 1858 | 1498 | 597 | 490 | 397 | 346 | 291 | 13,183 |

| 2018 | 474 | 410 | 402 | 303 | 229 | 209 | 230 | 201 | 241 | 305 | 160 | 155 | 3,319 |

| 2019 | 323 | 271 | 123 | 140 | 167 | 130 | 145 | 93 | 151 | 361 | 274 | 215 | 2,393 |

| 2020 | 114 | 148 | 73 | 52 | 74 | 64 | 49 | 82 | 54 | 70 | 74 | 54 | 908 |

| 2021 | 64 | 56 | 49 | 66 | 49 | 46 | 87 | 60 | 41 | 65 | 23 | 63 | 669 |

| 2022 | 62 | 46 | 42 | 31 | 82 | 44 | 67 | 80 | 68 | 63 | 65 | 90 | 740 |

| 2023 | 56 | 52 | 76 | 85 | 45 | 314 |

People's Kifah

The Iraqi political party People's Kifah, or Struggle Against Hegemony (PK) said that its survey conducted between March and June 2003 throughout the non-Kurdish areas of Iraq tallied 36,533 civilians killed in those areas by June 2003. While detailed town-by-town totals were given by the PK spokesperson, details of methodology are very thin and raw data is not in the public domain. A still-less-detailed report on this study appeared some months later on Al Jazeera's website, and covered casualties up to October 2003.[170]

Iraqi refugees crisis

Roughly 40 percent of Iraq's middle class is believed to have fled, the U.N. reported in 2007. Most are fleeing systematic persecution and have no desire to return. All kinds of people, from university professors to bakers, have been targeted by militias, Iraqi insurgents and criminals. An estimated 331 school teachers were slain in the first four months of 2006, according to Human Rights Watch, and at least 2,000 Iraqi doctors have been killed and 250 kidnapped since the 2003 U.S. invasion.[171]

Coalition military casualties

| Coalition deaths by country

|

For the latest casualty numbers see the overview chart at the top of the page.

Since the official handover of power to the Iraqi Interim Government on June 28, 2004, coalition soldiers have continued to come under attack in towns across Iraq.

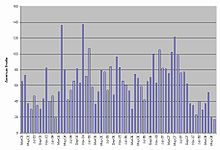

National Public Radio, iCasualties.org, and GlobalSecurity.org have month-by-month charts of American troop deaths in the Iraq War.[90][172][173]

The combined total of coalition and contractor casualties in the conflict is now over ten times that of the 1990–1991 Gulf War. In the Gulf War, coalition forces suffered around 378 deaths, and among the Iraqi military, tens of thousands were killed, along with thousands of civilians.

Troops fallen ill, injured, or wounded

See the overview chart at the top of the page for recent numbers.

On August 29, 2006, The Christian Science Monitor reported:[174] "Because of new body armor and advances in military medicine, for example, the ratio of combat-zone deaths to those wounded has dropped from 24 percent in Vietnam to 13 percent in Iraq and Afghanistan. In other words, the numbers of those killed as a percentage of overall casualties is lower."

Many U.S. veterans of the Iraq War have reported a range of serious health issues, including tumors, daily blood in urine and stool, sexual dysfunction, migraines, frequent muscle spasms, and other symptoms similar to the debilitating symptoms of "Gulf War syndrome" reported by many veterans of the 1991 Gulf War, which some believe is related to the U.S.'s use of radioactive depleted uranium.[175]

A study of U.S. veterans published in July 2004 in The New England Journal of Medicine on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans found that 5 percent to 9.4 percent (depending on the strictness of the PTSD definition used) suffered from PTSD before deployment. After deployment, 6.2 percent to 19.9 percent suffered from PTSD. For the broad definition of PTSD that represents an increase of 10.5 percent (19.9 percent – 9.4 percent = 10.5 percent). That is 10,500 additional cases of PTSD for every 100,000 U.S. troops after they have served in Iraq. ePluribus Media, an independent citizen journalism collective, is tracking and cataloging press-reported possible, probable, or confirmed incidents of post-deployment or combat-zone cases in its PTSD Timeline.[176]

Information on injuries suffered by troops of other coalition countries is less readily available, but a statement in Hansard indicated that 2,703 U.K. soldiers had been medically evacuated from Iraq for wounds or injuries as of October 4, 2004, and that 155 U.K. troops were wounded in combat in the initial invasion.[177]

Leishmaniasis has been reported by U.S. troops stationed in Iraq, including visceral leishmaniasis.[178] Leishmaniasis, spread by biting sand fleas, was diagnosed in hundreds of U.S. troops compared to just 32 during the first Gulf War.[179]

Accidents and negligence

As of August 2008, sixteen American troops have died from accidental electrocutions in Iraq according to the Defense Department.[180] One soldier had been electrocuted in a shower, while another had been electrocuted in a swimming pool. KBR, the contractor responsible, had been warned by employees of unsafe practices, and was criticised following the revelations.[181]

Nightline controversy

Ted Koppel, host of ABC's Nightline, devoted his entire show on April 30, 2004, to reading the names of 721 of the 737 U.S. troops who had died thus far in Iraq. (The show had not been able to confirm the remaining sixteen names.) Claiming that the broadcast was "motivated by a political agenda designed to undermine the efforts of the United States in Iraq", the Sinclair Broadcast Group took the action of barring the seven ABC network-affiliated stations it controls from airing the show. The decision to censor the broadcast drew criticism from both sides, including members of the armed forces, opponents of the war, MoveOn.org, and most notably Republican U.S. Senator John McCain, who denounced the move as "unpatriotic" and "a gross disservice to the public".[182][183][184]

Amputees

As of January 18, 2007, there were at least 500 American amputees due to the Iraq War. In 2016, the number was estimated to be 1,650 U.S. troops.[185] The 2007 estimate suggests amputees represent 2.2% of the 22,700 U.S. troops wounded in action (5% for soldiers whose wounds prevented them returning to duty).[149]

Traumatic brain injuries

By March 2009, the Pentagon estimated as many as 360,000 U.S. veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts may have suffered traumatic brain injuries (TBI), including 45,000 to 90,000 veterans with persistent symptoms requiring specialized care.[186]

In February 2007, one expert from the VA estimated that the number of undiagnosed TBIs were higher than 7,500.[187]

According to USA Today, by November 2007 there were more than an estimated 20,000 US troops who had signs of brain injuries without being classified as wounded during combat in Iraq and Afghanistan.[188]

Mental illness and suicide

A top U.S. Army psychiatrist, Colonel Charles Hoge, said in March 2008 that nearly 30% of troops on their third deployment suffered from serious mental-health problems, and that one year was not enough time between combat tours.[189]

A March 12, 2007, Time article[190] reported on a study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine. About one third of the 103,788 veterans returning from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars seen at U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs facilities between September 30, 2001, and September 30, 2005, were diagnosed with mental illness or a psycho-social disorder, such as homelessness and marital problems, including domestic violence. More than half of those diagnosed, 56 percent, were suffering from more than one disorder. The most common combination was post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

In January 2008, the U.S. Army reported that the rate of suicide among soldiers in 2007 was the highest since the Army started counting in 1980. There were 121 suicides in 2007, a 20-percent jump over the prior year. Also, there were around 2100 attempted suicides and self-injuries in 2007.[191] Other sources reveal higher estimates.[192]

Time magazine reported on June 5, 2008:

Data contained in the Army's fifth Mental Health Advisory Team report indicate that, according to an anonymous survey of U.S. troops taken last fall, about 12% of combat troops in Iraq and 17% of those in Afghanistan are taking prescription antidepressants or sleeping pills to help them cope. ... About a third of soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq say they can't see a mental-health professional when they need to. When the number of troops in Iraq surged by 30,000 last year, the number of Army mental-health workers remained the same – about 200 – making counseling and care even tougher to get.[189]

In the same article Time also reported on some of the reasons for the prescription drug use:

That imbalance between seeing the price of war up close and yet not feeling able to do much about it, the survey suggests, contributes to feelings of "intense fear, helplessness or horror" that plant the seeds of mental distress. "A friend was liquefied in the driver's position on a tank, and I saw everything", was a typical comment. Another: "A huge f______ bomb blew my friend's head off like 50 meters from me." Such indelible scenes – and wondering when and where the next one will happen – are driving thousands of soldiers to take antidepressants, military psychiatrists say. It's not hard to imagine why.[189]

Concern has been expressed by mental health professionals about the effects on the emotional health and development of returning veterans' infants and children, due to the increased rates of interpersonal violence, posttraumatic stress, depression, and substance abuse that have been reported among these veterans.[193][194][195] Moreover, the stressful effects of physical casualties and loss pose enormous stress for the primary caregiver that can adversely affect her or his parenting, as well as the couple's children directly.[196] The mental health needs of military families in the aftermath of combat exposure and other war-related trauma have been thought likely to be inadequately addressed by the military health system that separates mental health care of the returning soldier from his or her family's care, the latter of whom is generally covered under a contracted, civilian managed-care system.[194][193]

Iraqi insurgent casualties

Total insurgent deaths are hard to estimate.[197][198] In 2003, 597 insurgents were killed, according to the U.S. military.[199] From January 2004 through December 2009 (not including May 2004 and March 2009), 23,984 insurgents were estimated to have been killed based on reports from Coalition soldiers on the frontlines.[200] In the two missing months from the estimate, 652 were killed in May 2004,[84] and 45 were killed in March 2009.[201] In 2010, another 676 insurgents were killed.[202] In January and March through October 2011, 451 insurgents were killed.[203][204][205][206][207][208][209][210][211] Based on all of these estimates some 26,405 insurgents/militia were killed from 2003, up until late 2011.