Czech language

| Czech | |

|---|---|

| čeština, český jazyk | |

| Native to | Czech Republic |

Native speakers | 10 million (2007)[1] |

| Latin script (Czech alphabet) Czech Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Institute of the Czech Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | cs |

| ISO 639-2 | cze (B) ces (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | ces |

| Glottolog | czec1258 |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-da < 53-AAA-b...-d (varieties: 53-AAA-daa to 53-AAA-dam) |

Czech (/ˈtʃɛk/; čeština Czech pronunciation: [ˈt͡ʃɛʃcɪna]) is a West Slavic language spoken by over 10 million people. It is an official language in the Czech Republic, where most of its speakers reside, and claims minority language status in Slovakia. It is most closely related to Slovak—with which it is mutually intelligible—then to other West Slavic languages like Polish, and then to other Slavic languages like Russian. Most of its vocabulary is based on roots shared with other Slavic and otherwise Indo-European languages, but many loanwords have been adopted in recent years, most of them associated with high culture.

Czech began life in its current branch as Old Czech before slowly dwindling in societal importance, being outclassed by German on its own land. In the mid-eighteenth century, however, the language underwent a revival, termed the Czech National Revival, in which Czech academics stressed the past accomplishments of their people and advocated for Czech to return as a written and esteemed language. The language has not changed much since this time, barring some minor morphological shifts and adoption of colloquial elements into formal varieties.

The language's phoneme inventory is of a moderate size: it includes five vowels—each of which is distinguished between short and long length—and twenty-five consonants, which are divided into "hard", "neutral", and "soft". Words may contain uncommon or complicated consonant clusters or be bereft of vowels altogether, and Czech contains a phoneme represented by the consonant ř, which is believed not to exist elsewhere. However, Czech orthography is very simple and has been used by phonologists as a model.

As a member of the Slavic sub-family of Indo-European, Czech is a fusional language and highly inflected. Its nouns and adjectives undergo a complex system of declension that accounts for case, number, gender, animacy, and even whether words end in hard, neutral, or soft consonants. With somewhat less complexity, verbs are conjugated for tense, number, and gender, and also display aspect. Because of this inflection, Czech word order is very flexible, and words may be moved around freely to change emphasis or form questions.

Classification

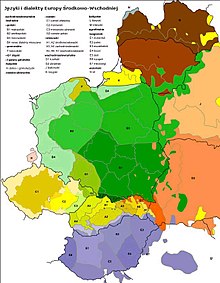

Czech is classified as a member of the West Slavic branch of the Slavic family. This places it in the same branch as Polish, Kashubian, and Upper and Lower Sorbian, as well as Slovak. Slovak is by far its closest genetic neighbor, and the two languages are closer than any other pair of West Slavic languages, including Upper and Lower Sorbian – they share a name through association with the same ethnic group.[2]

The West Slavic languages are all spoken in an area variously classified as part of Central or Eastern Europe. They are distinguished from East and South Slavic languages by features such as stress always being placed on the initial syllables of words and distinction between "hard" and "soft" consonants.[2]

Mutual intelligibility

Czech and Slovak are considered mutually intelligible: speakers of the two languages can communicate with relative ease, more so than speakers of most pairs of languages within the West, East, or South Slavic branches. Moreover, neither language has been endangered in recent years or forced to conform to an external standard, so there has been little artificial separation of the languages as a result of nationalism, as has occurred with, for example, Bosnian, Serbian, and Croatian. However, most Slavic languages, Czech included, have undergone some deliberate distancing from Russian influences due to widespread public resentment against the former Soviet Union, which occupied what was then Czechoslovakia during the Cold War.[3]

Most differences between Czech and Slovak are minor. In terms of sounds, Czech possesses a glottal stop before initial vowels, Slovak uses long vowels less frequently,[4] and Slovak possesses long forms of the consonants r and l for when they function as vowels.[5] The orthographies, however, are noticeably different. One study showed that the lexicons of Czech and Slovak differed by 80 percent, but this high percentage was found to stem mostly from differing orthographies and slight inconsistencies in morphological formation.[6] Slovak also has no vocative case.[4]

History

Old Czech

The Czech and Slovak lands were populated until the first century B.C. by Celts, after which Germanic tribes occupied it until the sixth century of the common era. Around the sixth century, a tribe of Slavs arrived in the area; they were led by a legendary hero named Čech, from whom the modern word Czech originates. However, these lands were shortly taken over by the Eurasian Avars, who were expanding all over western Eurasia. In the seventh century, the burgeoning ethnic group recaptured its old land from the Avars, led by a non-Czech named Samo.[7]

The ninth century brought with it the new state of Great Moravia, which comprised the Czech lands and fringes of modern-day Slovakia, Poland, and Hungary. Its first ruler, Rastislav of Moravia, invited Byzantine ruler Michael III to send his missionaries over. These missionaries, Constantine and Methodius, converted the West Slavs from traditional Slavic paganism to Orthodox Christianity and established an Orthodox church system. In addition, they brought the Latin alphabet for the West Slavs, who had had no writing system before.[7]

Bohemia, as the Czech civilization was known by then, rose in power over the centuries – not enough to compete economically or politically with neighboring European powers, but enough to keep its national integrity and stand as a respectable European cultural center. This growth was expedited in the fourteenth century by Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who founded Charles University in Prague in 1348. At this university flourished early literature in the Czech language: a Bible translation, hymns, and hagiography. Later in the century, Jan Hus contributed significantly to the standardization of Czech orthography, advocated for widespread literacy among Czech commoners—particularly in religious contexts—and made early efforts at modeling written Czech after spoken varieties.[8]

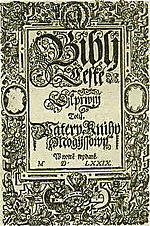

Overall, Czech continued to evolve up through the sixteenth century;[1] so too did it increase in local importance. A new Bible translation called the Kralice Bible appeared; it was published in the late sixteenth century, around the time of the King James and Luther versions but was more linguistically conservative than either of them. The Kralice Bible's publication spawned widespread nationalistic feelings, and in 1615 the government of Bohemia declared that only Czech-speaking residents would be allowed to become full citizens or inherit goods or land. This bold move—along with the Czech upper classes converting from the Habsburg Empire's Catholicism to Protestantism—angered the Habsburgs and caused the Czechs to tumble into the Thirty Years' War, where they were summarily defeated at the Battle of White Mountain. As a result, Czech farmers were made serfs, Bohemia's printing industry and linguistic and political rights were dismembered, and—as a final symbolic act—the Jesuits took over Charles University.[9] German quickly gained dominance in Bohemia.[1]

Modern Czech

The general consensus among linguists is that the modern standard form of the Czech language came into being in the eighteenth century.[10] By this point, Czech had developed a literary tradition, after which the language has not changed much; journals from around this time have been described as possessing no meaningful differences from modern standard Czech, and Czechs nowadays can understand them with little difficulty.[11] Among the changes conceded are the overall morphological shift of í into ej and é into í to take its place, though é survives for some uses, and the merging of í and the former ejí.[12]

The Czech people gained a widespread sense of nationalistic pride during the mid-eighteenth century, inspired by the ideals of the European Age of Enlightenment a half-century earlier. Czech historians began to take pride in their people's accomplishments from the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries and, as a result, rebel against the Counter-Reformation in the Bohemian lands, which had regarded the Czech language and other non-Latin tongues with scorn.[13] These scholars took to philology and studied sixteenth-century Czech texts, advocating for Czech to return as a language of high culture.[14] This period has been termed the Czech National Revival[15] or Renascence.[14]

In 1809, during the National Revival, linguist and historian Josef Dobrovský released a German-language grammar of old Czech titled Ausfürliches Lehrgebäude der böhmischen Sprache (Comprehensive Doctrine of the Bohemian Language). Dobrovský had intended his book to be merely descriptive, as he did not think Czech had a realistic chance of returning as a widespread language. However, Josef Jungmann and other revivalists latched onto Dobrovský's work and advocated for a conservative standard of Czech to make a comeback. The modern academic community is divided on whether these conservative revivalists were motivated more by their nationalist ideology or because contemporary spoken Czech was unsuitable for formal and widespread usage.[15]

Later on, however, allegiance to historical patterns was relaxed, and standard Czech took on a number of adoptions from Common Czech that have been decried as "decay" or even "agony", such as leaving certain proper nouns undeclined. This has resulted in a relatively high level of homogeneity among all varieties of the Czech language.[16]

Geographic distribution

In 2005 and 2007, Czech was spoken by about 10 million residents of the Czech Republic.[1][17] A Eurobarometer survey conducted between January and March 2012 found that 98% of Czech citizens had their nation's official language as their mother tongue – the third highest in the European Union, behind Malta and Hungary.[18]

Through being the official language of the Czech Republic, a member of the European Union (EU) since 2005, Czech is one of the EU's official languages. The 2012 Eurobarometer survey found that Czech was the most spoken foreign language in Slovakia.[18] Economist Jonathan van Parys collected data on knowledge of various languages across European nations to celebrate the 2012 European Day of Languages, and the five countries with the highest prevalence of Czech knowledge were as follows.[19]

- Czech Republic: 98.77%

- Slovakia: 24.86%

- Portugal: 1.93%

- Poland: 0.98%

- Germany: 0.47%

Czech speakers in Slovakia cluster mainly in its urban areas. Czech is recognized as a minority language in Slovakia; thus, citizens of this country who speak only Czech are allowed to interact with the government in their language to the extent that Slovak speakers are in theirs.[20]

United States

Immigration of Czechs from Europe to the United States occurred mainly between 1848 and 1914, and they brought their language with them. However, it is rarely taught in schools, instead being mainly offered at Czech heritage centers. Large communities of Czech Americans live in the states of Nebraska, Texas, and Wisconsin.[21] In the 2000 United States Census, Czech was reported as the most common language spoken at home besides English in Valley, Butler, and Saunders Counties, Nebraska, and Republic County, Kansas. However, Spanish is by far the most common language spoken at home besides English, and when Spanish too was removed, Czech was the most common in over a dozen more counties of Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, North Dakota, and Minnesota.[22] As of 2009, 70,500 Americans spoke Czech as their primary language; this placed it 49th among all languages, behind Turkish and ahead of Swedish.[23]

Dialects

The Czech language comprises a few regional dialects in addition to a general spoken standard and a closely related written standard. Czechs especially in rural areas have mostly spoken in their dialects; some are less than proficient in other dialects or in standard Czech. Beginning roughly with the second half of the twentieth century, however, dialect use among Czechs began to weaken. By the early 1990s, dialect use had become stigmatized and associated with the shrinking lower class; when represented in literature or other media, it was usually utilized for comedic effect rather than to sincerely represent its associated populace. Increasing availability of travel and media to populations speaking divergent dialects has encouraged them to shift to—or adopt alongside their own dialect—standard Czech.[24] Moreover, while Czech has seen a high amount of scholarly interest for a Slavic language, this interest has focused mostly on modern standard Czech and ancient texts rather than on dialects of any time period.[25]

The division of Czech into dialects is not consistent. One fairly high estimate made in 2003 comes from the Czech Statistical Office; it counts the following dialects.[26]

- Nářečí středočeská (Central Bohemian Dialect)

- Nářečí jihozápadočeská (Southwestern Bohemian Dialect)

- Nářečí českomoravská (Bohemian–Moravian Dialect)

- Nářečí středomoravská (Central Moravian Dialect)

- Podskupina tišnovská (Tišnov Subgroup)

- Nářečí východomoravská (Eastern Moravian Dialect)

- Podskupina slovácká (Slovak Subgroup)

- Podskupina valašská (Valašská Polanka Subgroup)

- Nářečí slezská (Silesian Dialect)

- Nářečí severovýchodočeská (Northeastern Bohemian Dialect)

- Podskupina podkrknošská (Krkonoše Subgroup)

The main colloquial dialect of the language, spoken especially near Prague but also elsewhere throughout the country, is known as Common Czech (obecná čeština). This term is, first and foremost, an academic distinction. Most Czechs either do not know the compound term obecná čeština or associate it with all vernacular or incorrect forms of Czech combined.[25]

The general dialect of Moravia and Silesia is known widely as Moravian (moravský). During the Czech people's time in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, "Czech-Moravian-Slovak" was distinguished as a language aspiring citizens could register under, alongside German, Polish, and a few others.[27] Among Czech dialects, only Moravian is distinguished in nationwide surveys by the Czech Statistical Office. As of 2011, 62,908 Czech citizens had Moravian as their only mother tongue, while 45,561 more were natively diglossal between Moravian and standard Czech.[28]

Some southeastern Moravian dialects are also sometimes considered to actually be dialects of Slovak. These similarities originate with the ancient Moravian empire, in which Moravians and Slovaks were one nation with one language until the Moravians merged with the Czechs (Bohemians). Those dialects form a continuum between the Czech and Slovak languages[29] and still use the same declension patterns for nouns and pronouns and the same verb conjugations as Slovak.[30]

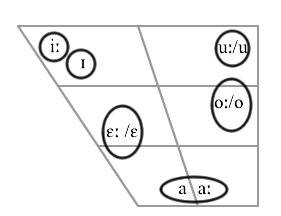

Phonology

Czech contains five basic vowel phonemes: /a/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /o/, and /u/.[31] They are all monophthongs[32]—except in the case of /ou̯/[33]—and never reduced to schwa sounds when unstressed.[32] Each word usually has primary stress on its first syllable; one exception is enclitics, minor monosyllabic words that receive no stress. In all words of more than two syllables, every odd-numbered syllable receives secondary stress. In all cases, stress is unrelated to vowel length; the possibility of stressed short vowels and unstressed long vowels can be confusing to learners of Czech whose native language combines the two features, such as English.[34]

Voiced consonants with unvoiced counterparts are unvoiced at the end of a word or when followed by unvoiced consonants.[35] As an unrelated feature, the body of Czech consonants is divided into hard, neutral, and soft consonants:

- Hard: /d/, /g/, /ɦ/, /k/, /n/, /r/, /t/, /x/

- Neutral: /b/, /f/, /l/, /m/, /p/, /s/, /v/, /z/

- Soft: /c/, /ɟ/, /j/, /ɲ/, /r̝/, /ʃ/, /ts/, /tʃ/, /ʒ/

This distinction has little phonetic value other than by affecting declension patterns, but in orthography, hard consonants may not be followed by y or ý, nor weak ones by i or í, except in loanwords such as kilogram. Neutral consonants may take either character. Hard consonants are sometimes referred to as strong and soft ones as weak.[36]

The consonant ř (capital Ř) is believed to be unique to Czech. It represents the raised alveolar non-sonorant trill (IPA: [r̝]), a sound somewhere between Czech's r and ž (example: ).[37] Notably, it appears in the name Dvořák.

The consonants /r/ and /l/ can act as acceptable vowels of syllables. This can be difficult for outsiders to pronounce; there exists a Czech tongue twister that goes: strč prst skrz krk (stick [your] finger down [your] throat).[38]

|

Consonants

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vocabulary

The vocabulary of Czech comes mostly from Slavic, Baltic, and other Indo-European roots. Generally, most verbs and prepositions are of Balto-Slavic origin, while pronouns and some verbs and prepositions are of wider Indo-European origin.[39] However, Czech- or Slavic-like construction is not always genuine: some words were apparently created from nonsense or non-Czech words to resemble Czech words, e.g. hřbitov (graveyard), listina (list).[40]

Most loanwords in Czech come from one of two time periods. Initially, they arrived, mostly from German,[41] Greek, and Latin,[42] before the nationalist re-invigoration of Czech as a literary language. In recent times, as the Czech people have come in contact with more of the world, loanwords from a wider variety of languages have arrived: principally English and French,[41] but also the likes of Hebrew, Arabic, and Persian. Lasting Russian loanwords have also been adopted, mainly concerning animal names and naval terms.[43]

Older German loanwords tend to be seen as crude or even vulgar, while more recent adoptions from other tongues are often associated with high culture.[41] Moreover, adoptions from Greek and Latin roots began to be rejected in the nineteenth century in favor of words based on older Czech words and common Slavic roots. For example, while the Polish word for "music" is muzyka and the Russian word музыка (muzyka), Czech uses hudba.[42]

Some Czech words have been adopted as loanwords into English and other languages, e.g. robot (from robota [labor]),[44] pilsner (from Plzeň [a Czech village]),[45] polka (from polka [Polish woman]).[46]

Grammar

Czech is a fusional language: its nouns, verbs, and adjectives are inflected to alter their meanings, unlike agglutinative and polysynthetic languages, which rely on extensive prefixes and suffixes, and analytic languages, in which few or no words are modified at all.[47] Most Indo-European languages are fusional, as are a few members of other families like Afro-Asiatic and Uralic. As a member of the Slavic sub-family, Czech inflection is complex and pervasive.[48]

Sentence and clause structure

Complete sentences in Czech must include, at minimum, a noun or pronoun and a verb. Pronouns are distinguished for person and number.[49]

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | já | my |

| 2. | ty vy (formal) |

vy |

| 3. | on (male) ona (female) ono (neuter) |

oni (males) ony (females) ono (neuter entities) |

Other parts of speech include adjectives, adverbs, numbers, question words, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections.[50] The rest stand on their own, but adverbs are mostly formed by taking the final ý or í of an adjective and replacing it with e, ě, or o.[51] Negative statements are formed simply by adding the affix ne- to the verb of the clause, with one exception: je (he is, she is, it is) becomes není.[52]

Because the language uses cases rather than relying on word order to convey the functions of words, as English does, Czech word order is very flexible; sometimes all possible permutations of words in a clause are acceptable. However, switching words in a clause around is not without grammatical use: it allows for differing emphasis. Typically, any word at the end of a clause is to be emphasized, unless an upward intonation indicates that the sentence is a question. One example follows.[53]

- Pes jí bagetu. – The dog eats the bagel (rather than eating something else).

- Jí bagetu pes. – The dog eats the bagel (rather than someone else doing so).

- Pes bagetu jí. – The dog eats the bagel (rather than doing something else to it).

- Jí pes bagetu? – Does the dog eat the bagel? (emphasis ambiguous)

However, in parts of Bohemia such as Prague, questions such as Jí pes bagetu? that do not have a distinctive question word (such as co [what] or kdo [who]) are instead given intonation that slowly escalates from low to high, then quickly drops to low on the last word or phrase.[54]

Declension

Each Czech noun and, if available, its associated adjective is declined into one of seven grammatical cases to indicate the noun's use in the sentence. When Czech children are formally learning their language's declension patterns, the cases are referred to by numbers, as follows.[55]

| No. | Ordinal name (Czech) | Full name (Czech) | Case | Main usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | první pád | nominativ | nominative | Subjects |

| 2. | druhý pád | genitiv | genitive | Belonging, movement away from something or someone |

| 3. | třetí pád | dativ | dative | Indirect objects, movement toward something or someone |

| 4. | čtvrtý pád | akuzativ | accusative | Direct objects |

| 5. | pátý pád | vokativ | vocative | Addressing someone |

| 6. | šestý pád | lokál | locative | Location |

| 7. | sedmý pád | instrumentál | instrumental | Being used for a task, acting alongside someone or something |

However, some grammars of Czech order the cases differently to group the nominative and accusative together, as well as the dative and locative, as these declension patterns are often identical. An added benefit of this order is to accommodate learners with experience in other inflected languages like Latin or Russian. This order is: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, locative, instrumental, vocative.[55]

While prepositions themselves are not declined, the noun phrases they modify are. These case markings are predictable for the most part, corresponding to the physical or metaphorical direction or location conveyed by each preposition. For example, od (from, away from) and z (out of, off of) assign the genitive case. Complicating the system is that some prepositions may take any of multiple cases and change their meaning depending on the case. For example, na means "onto" or "for" when used with the accusative case, but "on" with the locative.[56]

Gender and animacy

Czech distinguishes three genders—masculine, feminine, and neuter—and masculine is further divided into animate and inanimate. With few exceptions, feminine nouns in the nominative case end with -a, -e, or -ost; neuter nouns with -o, -e, or -í; and masculine nouns with a consonant.[57] Adjectives agree in gender with the nouns they modify and—for masculine nouns in the accusative/genitive singular and the nominative plural—also agree in animacy.[58] The main effect of gender in Czech is the differences in noun and adjective declension, but there are other effects. For example, past-tense verbs take similar endings based on gender: e.g. dělal (he did/made); dělala (she did/made); dělalo (it did/made).[59]

Number

Declension is also affected by number. This system is typical for a Slavic language: cardinal numbers one through four allow the nouns and adjectives they modify to take any case, but numbers over five place these nouns and adjectives in the genitive case. The Czech koruna is a handy example of this feature; it is shown here as the subject of a hypothetical sentence, and thus declined as genitive for numbers five and up.[60]

| English | Czech |

|---|---|

| one crown | jedna koruna |

| two crowns | dvě koruny |

| three crowns | tři koruny |

| four crowns | čtýři koruny |

| five crowns | pět korun |

Words for numbers decline for case and, for numbers one and two, also for gender. Numbers one through five are shown below as examples; they have some of the most exceptions among the numbers. The number one has declension patterns identical to those of the demonstrative pronoun, to.[61][62]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | jeden (male) jedna (female) jedno (neuter) |

dva (male) dvě (female, neuter) |

tři | čtýři | pět |

| Genitive | jednoho (male) jedné (female) jednoho (neuter) |

dvou | tří | čtýř | pěti |

| Dative | jednomu (male) jedné (female) jednomu (neuter) |

dvěma | třem | čtyřem | pěti |

| Accusative | jednoho (male an.) jeden (male in.) jednu (female) jedno (neuter) |

dva (male) dvě (female, neuter) |

tři | čtýři | pět |

| Locative | jednom (male) jedné (female) jednom (neuter) |

dvou | třech | čtyřech | pěti |

| Instrumental | jedním (male) jednou (female) jedním (neuter) |

dvěma | třemi | čtyřmi | pěti |

While Czech's main grammatical numbers are singular and plural, vestiges of a dual number remain. Most notably, some nouns referring to parts of the body that come in pairs have a dual form, e.g. ruka (hand) – ruce, noha (leg) – nohy, oko (eye) – oči, ucho (ear) – uši. Oddly, while two of these nouns are neuter in their singular forms, all dual nouns are treated as feminine. Czech has no standard declension scheme for dual nouns; their gender is relevant for their associated adjectives and verbs.[63]

Verb conjugation

As is typical in Slavic languages, Czech includes grammatical aspect in two forms: perfective and imperfective. Most verbs come in pairs, one of each aspect. The meaning is identical or similar in each case, but differs in that perfective verbs are seen as completed and imperfective verbs as ongoing. However, this does not mean that the perfective aspect is equal to the past tense and the imperfective aspect the present.[64] In fact, any Czech verb of either aspect can be conjugated into any of the language's three tenses: past, present, or future.[65] More accurately, aspect describes the state of the action at the time specified by tense.[64]

The verbs of most aspectual pairs differ in one of two ways: by prefixes or by suffixes. In prefix pairs, the perfective verb has an added prefix, e.g. imperfective psát (to write, to be writing) vs. perfective napsat (to write down, to finish writing). The most common prefixes are na-, o-, po-, s-, u-, vy-, z-, and za-.[66] In suffix pairs, a suffix is added to the root of the imperfective form, usually -at, -ávat, -et, -ovat, or -vat.[67]

Some verbs only exist in one aspect. Many verbs concerning continual states of being, e.g. být (to be), chtít (to want), moct (to be able to), ležet (to lie down, to be lying down) have no perfective form. Conversely, many verbs that represent immediate states of change, e.g. otěhotnět (to become pregnant), nadchnout se (to become enthusiastic), have no imperfective.[68]

The language's use of the present and future tenses is comparable to that of English, for the most part. However, Czech simply utilizes the past tense to represent what in English is the present perfect and past perfect. This means that Ona běžela could correspond to She ran, She has run, or She had run.[69]

In some contexts, Czech's perfective present (not to be confused with the present perfect of English) carries an implication of future action. In others, it connotes a habitual action.[70] As a result, the proper future tense is used to minimize ambiguity. The future tense does not involve conjugation of the verb that represents an action to be undertaken in the future. Instead, the future form of být is placed before the infinitive of this verb, as follows.[71]

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | budu | budeme |

| 2. | budeš | budete |

| 3. | bude | budou |

However, this conjugation is never followed by být itself, so future-oriented expressions involving nouns, adjectives, or prepositions rather than verbs simply omit být. For example, the expression "I will be happy" is translated as Budu šťáštný, not Budu být šťáštný.[71]

Czech also includes a conditional mood that is formed by placing special particles after the past-tense verb. This mood indicates possible events, namely I would and I wish. An example follows, using the verb koupit (to buy).[72]

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | koupil/a bych | koupil/y bychom |

| 2. | koupil/a bys | koupil/y byste |

| 3. | koupil/a by | koupil/y by |

Czech verbs come in several classes, affecting their declension patterns. The future tense of být would be classified as a typical "Class I" verb because of its endings. Although a full explanation of the system is much more complicated, a basic sample of the present tense of each class—as well as some common irregular verbs—follows.[73]

|

|

Orthography

Czech has one of the most phonetic and regular orthographies of all European languages: its thirty-one graphemes represent thirty sounds (in most dialects, i and y denote the same sound), and it contains only one digraph (ch). As a result, some of its characters have been used by phonologists to denote corresponding sounds in other languages. However, the characters q, w, and x appear only in foreign words.[74] The háček (ˇ) is used with certain letters to form new characters: š, ž, and č, as well as ň, ě, and ř, which are uncommon outside Czech. Additionally, ť and ď (aspirated versions of t and d) are written this way as an evolution of the háček that accommodates the letters' height.[75] The character ó exists only in loanwords.[76]

Unlike most European languages, Czech distinguishes vowel length: long vowels are indicated by an acute accent or, in one case, a ring, while short vowels are left unadorned. Long vowels are not normally considered separate letters, and Czech alphabetical order does not afford them their own spots.[74] The long u is written ú when starting a word and ů elsewhere.[77]

In general, Czech typographical features not tied to phonetics resemble those of most European languages using the Latin alphabet, including English. Proper nouns, honorifics, and the initial letters of direct quotations are capitalized, and punctuation is typical for the most part. One unusual feature is the way thousands are marked off in numbers written with Arabic numerals: the millions place and all higher places receive commas, the thousands place receives a period, and the ones place (preceding decimals) receives a mid-height period, similar to a bullet point. For example, the number written 20,671,634.09 in English would be 20,671.634·09 in Czech.[78] Another unusual feature is that in proper noun phrases of more than one word, only the first word is capitalized, e.g. Pražský hrad (Prague Castle).[79]

Sample text

Czech: Všichni lidé se rodí svobodní a sobě rovní co do důstojnosti a práv. Jsou nadáni rozumem a svědomím a mají spolu jednat v duchu bratrství.

English: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d Cerna & Machalek 2007, p. 26

- ^ a b Sussex & Cubberley 2011, pp. 54–55

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2011, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b Sussex & Cubberley 2011, pp. 57–58

- ^ Esposito 2011, p. 83

- ^ Esposito 2011, p. 82

- ^ a b Sussex & Cubberley 2011, p. 98

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2011, pp. 98–99

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2011, pp. 99–100

- ^ Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993, p. 92

- ^ Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993, p. 95

- ^ Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993, p. 93

- ^ Agnew 1994, p. 250

- ^ a b Agnew 1994, pp. 251–252

- ^ a b Wilson 2010, p. 18

- ^ Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993, pp. 93–95

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 2

- ^ a b "Europeans and Their Languages" (PDF). Eurobarometer. June 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ^ van Parys, Jonathan (2012). "Language knowledge in the European Union". Language Knowledge. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Škrobák, Zdeněk. "Language Policy of Slovak Republic" (PDF). Annual of Language & Politics and Politics of Identity. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hrouda, Simone J. "Czech Language Programs and Czech as a Heritage Language in the United States" (PDF). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Chapter 8: Language" (PDF). Census.gov. 2000. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Languages of the U.S.A." (PDF). U.S. English. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Eckert 1993, pp. 143–144

- ^ a b Wilson 2010, p. 21

- ^ "Map of Czech Dialects". Český statistický úřad (Czech Statistical Office). 2003. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Kortmann & van der Auwera 2011, p. 714

- ^ "Tab. 614b Obyvatelstvo podle věku, mateřského jazyka a pohlaví (Population by Age, Mother Tongue, and Gender)" (in Czech). Český statistický úřad (Czech Statistical Office). March 26, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Kortmann & van der Auwera 2011, p. 516

- ^ Šustek, Zbyšek (1998). "Otázka kodifikace spisovného moravského jazyka (The question of codifying a written Moravian language)" (in Czech). University of Tartu. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Harkins 1952, pp. 2–3

- ^ a b Harkins 1952, pp. 1–2

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 9

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 12

- ^ Harkins 1952, pp. 10–11

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 11

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 6

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 5

- ^ Mann 1957, p. 159

- ^ Mann 1957, p. 160

- ^ a b c Mathesius 2013, p. 20

- ^ a b Sussex & Cubberley 2011, p. 101

- ^ Mann 1957, pp. 159–160

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "robot (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "pilsner (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "polka (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ Qualls 2012, pp. 6–8

- ^ Qualls 2012, p. 5

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 74

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. v–viii

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 61–63

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 212

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 10–11

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 10

- ^ a b Naughton 2005, p. 25

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 201–205

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 22–24

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 51

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 141

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 114

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 83

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 117

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 40

- ^ a b Naughton 2005, p. 146

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 131

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 147

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 147–148

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 149

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 140

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 150

- ^ a b Naughton 2005, p. 151

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 152–154

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 136–140

- ^ a b Harkins 1952, p. 1

- ^ Harkins 1952, pp. 6–8

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 8

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 7

- ^ Harkins 1952, pp. 14–15

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 11

References

- Agnew, Hugh LeCaine (1994). Origins of the Czech National Renascence. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-8549-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barta, Peter I. (2013). The Fall of the Iron Curtain and the Culture of Europe. Routledge Press. ISBN 978-0-415-59237-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cerna, Iva; Machalek, Jolana (2007). Beginner's Czech. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1156-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chloupek, Jan; Nekvapil, Jiří (1993). Studies in Functional Stylistics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-1545-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eckert, Eva (1993). Varieties of Czech: Studies in Czech Sociolinguistics. Editions Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-5183-490-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Esposito, Anna (2011). Analysis of Verbal and Nonverbal Communication and Enactment: The Processing Issues. Springer Press. ISBN 978-3-642-25774-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harkins, William Edward (1952). A Modern Czech Grammar. King's Crown Press (Columbia University). ISBN 978-0-231-09937-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kortmann, Bernd; van der Auwera, Johan (2011). The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide (World of Linguistics). Mouton De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022025-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mann, Stuart Edward (1957). Czech Historical Grammar. Helmut Buske Verlag. ISBN 978-3-87118-261-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mathesius, Vilém (2013). A Functional Analysis of Present Day English on a General Linguistic Basis. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-90-279-3077-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Naughton, James (2005). Czech: An Essential Grammar. Routledge Press. ISBN 978-0-415-28785-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Qualls, Eduard J. (2012). The Qualls Concise English Grammar. Danaan Press. ISBN 978-1-890000-09-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stankiewicz, Edward (1986). The Slavic Languages: Unity in Diversity. Mouton De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-009904-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sussex, Rolan; Cubberley, Paul (2011). The Slavic Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. ISBN 978-0-521-29448-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, James (2009). Moravians in Prague: A Sociolinguistic Study of Dialect Contact in the Czech. Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-3-631-58694-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Ústav pro jazyk český – Czech Language Institute, the regulatory body for the Czech language Template:Cs icon

- A GRAMMAR OF CZECH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE, written by Karel Tahal

- Czech National Corpus

- Czech Monolingual Online Dictionary

- Czech Translation Dictionaries (Lexilogos)

- Czech Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Foreign Service Institute Czech basic course, audio, assignments, G+ hangouts and media sources

- USA Foreign Service Institute (FSI) Czech basic course

- Basic Czech Phrasebook with Audio