Manga

| Manga | |

|---|---|

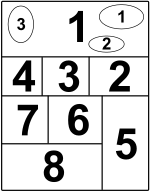

The kanji for "manga" from Seasonal Passersby (Shiki no Yukikai), 1798, by Santō Kyōden and Kitao Shigemasa. | |

| Publishers | |

| Publications | |

| Series | |

| Languages | Japanese |

| Related articles | |

| Part of a series on |

| Anime and manga |

|---|

|

|

|

Manga (漫画, Manga) are comics created in Japan, or by creators in the Japanese language, conforming to a style developed in Japan in the late 19th century.[1] They have a long and complex pre-history in earlier Japanese art.[2]

The term manga (kanji: 漫画; hiragana: まんが; katakana: マンガ; ; English: /ˈmæŋɡə/ or /ˈmɑːŋɡə/) is a Japanese word referring both to comics and cartooning. "Manga" as a term used outside Japan refers specifically to comics originally published in Japan.[3]

In Japan, people of all ages read manga. The medium includes works in a broad range of genres: action-adventure, business/commerce, comedy, detective, historical drama, horror, mystery, romance, science fiction and fantasy, sexuality, sports and games, and suspense, among others. Although this form of entertainment originated in Japan, many manga are translated into other languages, mainly English.[4] Since the 1950s, manga has steadily become a major part of the Japanese publishing industry,[5] representing a ¥406 billion market in Japan in 2007 (approximately $3.6 billion) and ¥420 billion (approximately $5.5 billion) in 2009.[6] Manga have also gained a significant worldwide audience.[7] In Europe and the Middle East the market was worth $250 million in 2012.[8] In 2008, in the U.S. and Canada, the manga market was valued at $175 million; the markets in France and the United States are about the same size.[citation needed] Manga stories are typically printed in black-and-white,[9] although some full-color manga exist (e.g., Colorful). In Japan, manga are usually serialized in large manga magazines, often containing many stories, each presented in a single episode to be continued in the next issue. If the series is successful, collected chapters may be republished in tankōbon volumes, frequently but not exclusively, paperback books.[10] A manga artist (mangaka in Japanese) typically works with a few assistants in a small studio and is associated with a creative editor from a commercial publishing company.[11] If a manga series is popular enough, it may be animated after or even during its run.[12] Sometimes manga are drawn centering on previously existing live-action or animated films.[13]

Manga-influenced comics, among original works, exist in other parts of the world, particularly in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan ("manhua"), and South Korea ("manhwa").[14][15] In France, "manfra" and "la nouvelle manga" have developed as forms of bande dessinée comics drawn in styles influenced by manga. The term OEL manga is often used to refer to comics or graphic novels created for a Western market in the English language, which draw inspiration from the "form of presentation and expression" found in manga.[citation needed]

Etymology

The word "manga" comes from the Japanese word 漫画,[16] composed of the two kanji 漫 (man) meaning "whimsical or impromptu" and 画 (ga) meaning "pictures".[17]

The word first came into common usage in the late 18th century[18] with the publication of such works as Santō Kyōden's picturebook Shiji no yukikai (1798),[19][20] and in the early 19th century with such works as Aikawa Minwa's Manga hyakujo (1814) and the celebrated Hokusai Manga books (1814–1834) containing assorted drawings from the sketchbooks of the famous ukiyo-e artist Hokusai.[21] Rakuten Kitazawa (1876–1955) first used the word "manga" in the modern sense.[22]

In Japanese, "manga" refers to all kinds of cartooning, comics, and animation. Among English speakers, "manga" has the stricter meaning of "Japanese comics", in parallel to the usage of "anime" in and outside Japan. The term "ani-manga" is used to describe comics produced from animation cels.[23]

History and characteristics

Modern manga originated in the Occupation (1945–1952) and post-Occupation years (1952–early 1960s), while a previously militaristic and ultra-nationalist Japan rebuilt its political and economic infrastructure.

Writers on manga history have described two broad and complementary processes shaping modern manga. One view emphasizes events occurring during and after the U.S. Occupation of Japan (1945–1952), and stresses U.S. cultural influences, including U.S. comics (brought to Japan by the GIs) and images and themes from U.S. television, film, and cartoons (especially Disney).[24] The other view, represented by other writers such as Frederik L. Schodt, Kinko Ito, and Adam L. Kern, stress continuity of Japanese cultural and aesthetic traditions, including pre-war, Meiji, and pre-Meiji culture and art.[25]

Regardless of its source, an explosion of artistic creativity certainly occurred in the post-war period,[26] involving manga artists such as Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy) and Machiko Hasegawa (Sazae-san). Astro Boy quickly became (and remains) immensely popular in Japan and elsewhere,[27] and the anime adaptation of Sazae-san drawing more viewers than any other anime on Japanese television in 2011 .[citation needed] Tezuka and Hasegawa both made stylistic innovations. In Tezuka's "cinematographic" technique, the panels are like a motion picture that reveals details of action bordering on slow motion as well as rapid zooms from distance to close-up shots. This kind of visual dynamism was widely adopted by later manga artists.[28] Hasegawa's focus on daily life and on women's experience also came to characterize later shōjo manga.[29] Between 1950 and 1969, an increasingly large readership for manga emerged in Japan with the solidification of its two main marketing genres, shōnen manga aimed at boys and shōjo manga aimed at girls.[30]

In 1969 a group of female manga artists (later called the Year 24 Group, also known as Magnificent 24s) made their shōjo manga debut ("year 24" comes from the Japanese name for the year 1949, the birth-year of many of these artists).[31] The group included Moto Hagio, Riyoko Ikeda, Yumiko Oshima, Keiko Takemiya, and Ryoko Yamagishi.[10] Thereafter, primarily female manga artists would draw shōjo for a readership of girls and young women.[32] In the following decades (1975–present), shōjo manga continued to develop stylistically while simultaneously evolving different but overlapping subgenres.[33] Major subgenres include romance, superheroines, and "Ladies Comics" (in Japanese, redisu レディース, redikomi レディコミ, and josei 女性).[34]

Modern shōjo manga romance features love as a major theme set into emotionally intense narratives of self-realization.[35] With the superheroines, shōjo manga saw releases such as Pink Hanamori's Mermaid Melody Pichi Pichi Pitch Reiko Yoshida's Tokyo Mew Mew, And, Naoko Takeuchi's Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon, which became internationally popular in both manga and anime formats.[36] Groups (or sentais) of girls working together have also been popular within this genre. Like Lucia, Hanon, and Rina singing together, and Sailor Moon, Sailor Mercury, Sailor Mars, Sailor Jupiter, and Sailor Venus working together.[37]

Manga for male readers sub-divides according to the age of its intended readership: boys up to 18 years old (shōnen manga) and young men 18 to 30 years old (seinen manga);[38] as well as by content, including action-adventure often involving male heroes, slapstick humor, themes of honor, and sometimes explicit sexuality.[39] The Japanese use different kanji for two closely allied meanings of "seinen"—青年 for "youth, young man" and 成年 for "adult, majority"—the second referring to sexually overt manga aimed at grown men and also called seijin ("adult" 成人) manga.[40] Shōnen, seinen, and seijin manga share many features in common.

Boys and young men became some of the earliest readers of manga after World War II. From the 1950s on, shōnen manga focused on topics thought to interest the archetypal boy, including subjects like robots, space-travel, and heroic action-adventure.[41] Popular themes include science fiction, technology, sports, and supernatural settings. Manga with solitary costumed superheroes like Superman, Batman, and Spider-Man generally did not become as popular.[42]

The role of girls and women in manga produced for male readers has evolved considerably over time to include those featuring single pretty girls (bishōjo)[43] such as Belldandy from Oh My Goddess!, stories where such girls and women surround the hero, as in Negima and Hanaukyo Maid Team, or groups of heavily armed female warriors (sentō bishōjo)[44]

With the relaxation of censorship in Japan in the 1990s, a wide variety of explicit sexual themes appeared in manga intended for male readers, and correspondingly occur in English translations.[45] However, in 2010 the Tokyo Metropolitan Government passed a bill to restrict harmful content.[46]

The gekiga style of drawing—emotionally dark, often starkly realistic, sometimes very violent—focuses on the day-in, day-out grim realities of life, often drawn in gritty and unpretty fashions.[47] Gekiga such as Sampei Shirato's 1959–1962 Chronicles of a Ninja's Military Accomplishments (Ninja Bugeichō) arose in the late 1950s and 1960s partly from left-wing student and working-class political activism[48] and partly from the aesthetic dissatisfaction of young manga artists like Yoshihiro Tatsumi with existing manga.[49]

Publications

In Japan, manga constituted an annual 40.6 billion yen (approximately $395 million USD) publication-industry by 2007.[50] In 2006 sales of manga books made up for about 27% of total book-sales, and sale of manga magazines, for 20% of total magazine-sales.[51] The manga industry has expanded worldwide, where distribution companies license and reprint manga into their native languages.

Marketeers primarily classify manga by the age and gender of the target readership.[52] In particular, books and magazines sold to boys (shōnen) and girls (shōjo) have distinctive cover-art, and most bookstores place them on different shelves. Due to cross-readership, consumer response is not limited by demographics. For example, male readers may subscribe to a series intended for female readers, and so on. Japan has manga cafés, or manga kissa (kissa is an abbreviation of kissaten). At a manga kissa, people drink coffee, read manga and sometimes stay overnight.

The Kyoto International Manga Museum maintains a very large website listing manga published in Japanese.[53]

Magazines

Manga magazines usually have many series running concurrently with approximately 20–40 pages allocated to each series per issue. Other magazines such as the anime fandom magazine Newtype featured single chapters within their monthly periodicals. Other magazines like Nakayoshi feature many stories written by many different artists; these magazines, or "anthology magazines", as they are also known (colloquially "phone books"), are usually printed on low-quality newsprint and can be anywhere from 200 to more than 850 pages thick. Manga magazines also contain one-shot comics and various four-panel yonkoma (equivalent to comic strips). Manga series can run for many years if they are successful. Manga artists sometimes start out with a few "one-shot" manga projects just to try to get their name out. If these are successful and receive good reviews, they are continued. Magazines often have a short life.[54]

Collected volumes

After a series has run for a while, publishers often collect the episodes together and print them in dedicated book-sized volumes, called tankōbon. These can be hardcover, or more usually softcover books, and are the equivalent of U.S. trade paperbacks or graphic novels. These volumes often use higher-quality paper, and are useful to those who want to "catch up" with a series so they can follow it in the magazines or if they find the cost of the weeklies or monthlies to be prohibitive. Recently, "deluxe" versions have also been printed as readers have gotten older and the need for something special grew. Old manga have also been reprinted using somewhat lesser quality paper and sold for 100 yen (about $1 U.S. dollar) each to compete with the used book market.

History

Kanagaki Robun and Kawanabe Kyosai created the first manga magazine in 1874: Eshinbun Nipponchi. The magazine was heavily influenced by Japan Punch, founded in 1862 by Charles Wirgman, a British cartoonist. Eshinbun Nipponchi had a very simple style of drawings and did not become popular with many people. Eshinbun Nipponchi ended after three issues. The magazine Kisho Shimbun in 1875 was inspired by Eshinbun Nipponchi, which was followed by Marumaru Chinbun in 1877, and then Garakuta Chinpo in 1879.[55] Shōnen Sekai was the first shōnen magazine created in 1895 by Iwaya Sazanami, a famous writer of Japanese children's literature back then. Shōnen Sekai had a strong focus on the First Sino-Japanese War.[56]

In 1905 the manga-magazine publishing boom started with the Russo-Japanese War,[57] Tokyo Pakku was created and became a huge hit.[58] After Tokyo Pakku in 1905, a female version of Shōnen Sekai was created and named Shōjo Sekai, considered the first shōjo magazine.[59] Shōnen Pakku was made and is considered the first children's manga magazine. The children's demographic was in an early stage of development in the Meiji period. Shōnen Pakku was influenced from foreign children's magazines such as Puck which an employee of Jitsugyō no Nihon (publisher of the magazine) saw and decided to emulate. In 1924, Kodomo Pakku was launched as another children's manga magazine after Shōnen Pakku.[58] During the boom, Poten (derived from the French "potin") was published in 1908. All the pages were in full color with influences from Tokyo Pakku and Osaka Puck. It is unknown if there were any more issues besides the first one.[57] Kodomo Pakku was launched May 1924 by Tokyosha and featured high-quality art by many members of the manga artistry like Takei Takeo, Takehisa Yumeji and Aso Yutaka. Some of the manga featured speech balloons, where other manga from the previous eras did not use speech balloons and were silent.[58]

Published from May 1935 to January 1941, Manga no Kuni coincided with the period of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Manga no Kuni featured information on becoming a mangaka and on other comics industries around the world. Manga no Kuni handed its title to Sashie Manga Kenkyū in August 1940.[60]

Dōjinshi

Dōjinshi, produced by small publishers outside of the mainstream commercial market, resemble in their publishing small-press independently published comic books in the United States. Comiket, the largest comic book convention in the world with around 500,000 visitors gathering over three days, is devoted to dōjinshi. While they most often contain original stories, many are parodies of or include characters from popular manga and anime series. Some dōjinshi continue with a series' story or write an entirely new one using its characters, much like fan fiction. In 2007, dōjinshi sold for 27.73 billion yen (245 million USD).[50] In 2006 they represented about a tenth of manga books and magazines sales.[51]

International markets

By 2007, the influence of manga on international comics had grown considerably over the past two decades.[61] "Influence" is used here to refer to effects on the comics markets outside Japan and to aesthetic effects on comics artists internationally.

Traditionally, manga stories flow from top to bottom and from right to left. Some publishers of translated manga keep to this original format. Other publishers mirror the pages horizontally before printing the translation, changing the reading direction to a more "Western" left to right, so as not to confuse foreign readers or traditional comics-consumers. This practice is known as "flipping".[62] For the most part, criticism suggests that flipping goes against the original intentions of the creator (for example, if a person wears a shirt that reads "MAY" on it, and gets flipped, then the word is altered to "YAM"), who may be ignorant of how awkward it is to read comics when the eyes must flow through the pages and text in opposite directions, resulting in an experience that's quite distinct from reading something that flows homogeneously. If the translation is not adapted to the flipped artwork carefully enough it is also possible for the text to go against the picture, such as a person referring to something on their left in the text while pointing to their right in the graphic. Characters shown writing with their right hands, the majority of them, would become left-handed when a series is flipped. Flipping may also cause oddities with familiar asymmetrical objects or layouts, such as a car being depicted with the gas pedal on the left and the brake on the right, or a shirt with the buttons on the wrong side, but these issues are minor when compared to the unnatural reading flow, and some of them could be solved with an adaptation work that goes beyond just translation and blind flipping.[63]

Europe

Manga has influenced European cartooning in a way that is somewhat different from in the U.S. Broadcast anime in France and Italy opened the European market to manga during the 1970s.[64] French art has borrowed from Japan since the 19th century (Japonisme)[65] and has its own highly developed tradition of bande dessinée cartooning.[66] In France, beginning in the mid-1990s,[67] manga has proven very popular to a wide readership, accounting for about one-third of comics sales in France since 2004.[68] According to the Japan External Trade Organization, sales of manga reached $212.6 million within France and Germany alone in 2006.[64] France represents about 50% of the European market and is the second worldwide market, behind Japan.[8] In 2013, there were 41 publishers of manga in France and, together with other Asian comics, manga represented around 40% of new comics releases in the country,[69] surpassing Franco-Belgian comics for the first time.[70] European publishers marketing manga translated into French include Asuka, Casterman, Glénat, Kana, and Pika Édition, among others.[citation needed] European publishers also translate manga into Dutch, German, Italian, and other languages. In 2007, about 70% of all comics sold in Germany were manga.[71]

Manga publishers based in the United Kingdom include Gollancz and Titan Books.[citation needed] Manga publishers from the United States have a strong marketing presence in the United Kingdom: for example, the Tanoshimi line from Random House.[citation needed]

United States

Manga made their way only gradually into U.S. markets, first in association with anime and then independently.[72] Some U.S. fans became aware of manga in the 1970s and early 1980s.[73] However, anime was initially more accessible than manga to U.S. fans,[74] many of whom were college-age young people who found it easier to obtain, subtitle, and exhibit video tapes of anime than translate, reproduce, and distribute tankōbon-style manga books.[75] One of the first manga translated into English and marketed in the U.S. was Keiji Nakazawa's Barefoot Gen, an autobiographical story of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima issued by Leonard Rifas and Educomics (1980–1982).[76] More manga were translated between the mid-1980s and 1990s, including Golgo 13 in 1986, Lone Wolf and Cub from First Comics in 1987, and Kamui, Area 88, and Mai the Psychic Girl, also in 1987 and all from Viz Media-Eclipse Comics.[77] Others soon followed, including Akira from Marvel Comics' Epic Comics imprint, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind from Viz Media, and Appleseed from Eclipse Comics in 1988, and later Iczer-1 (Antarctic Press, 1994) and Ippongi Bang's F-111 Bandit (Antarctic Press, 1995).

In the 1980s to the mid-1990s, Japanese animation, like Akira, Dragon Ball, Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Pokémon, made a bigger impact on the fan experience and in the market than manga.[78] Matters changed when translator-entrepreneur Toren Smith founded Studio Proteus in 1986. Smith and Studio Proteus acted as an agent and translator of many Japanese manga, including Masamune Shirow's Appleseed and Kōsuke Fujishima's Oh My Goddess!, for Dark Horse and Eros Comix, eliminating the need for these publishers to seek their own contacts in Japan.[79] Simultaneously, the Japanese publisher Shogakukan opened a U.S. market initiative with their U.S. subsidiary Viz, enabling Viz to draw directly on Shogakukan's catalogue and translation skills.[62]

Japanese publishers began pursuing a U.S. market in the mid-1990s due to a stagnation in the domestic market for manga.[80] The U.S. manga market took an upturn with mid-1990s anime and manga versions of Masamune Shirow's Ghost in the Shell (translated by Frederik L. Schodt and Toren Smith) becoming very popular among fans.[81] An extremely successful manga and anime translated and dubbed in English in the mid-1990s was Sailor Moon.[82] By 1995–1998, the Sailor Moon manga had been exported to over 23 countries, including China, Brazil, Mexico, Australia, North America and most of Europe.[83] In 1997, Mixx Entertainment began publishing Sailor Moon, along with CLAMP's Magic Knight Rayearth, Hitoshi Iwaaki's Parasyte and Tsutomu Takahashi's Ice Blade in the monthly manga magazine MixxZine. Two years later, MixxZine was renamed to Tokyopop before discontinuing in 2011. Mixx Entertainment, later renamed Tokyopop, also published manga in trade paperbacks and, like Viz, began aggressive marketing of manga to both young male and young female demographics.[84]

In the following years, manga became increasingly popular, and new publishers entered the field while the established publishers greatly expanded their catalogues.[85] and by 2008, the U.S. and Canadian manga market generated $175 million in annual sales.[86] Simultaneously, mainstream U.S. media began to discuss manga, with articles in The New York Times, Time magazine, The Wall Street Journal, and Wired magazine.[citation needed][87]

Localized manga

A number of artists in the United States have drawn comics and cartoons influenced by manga. As an early example, Vernon Grant drew manga-influenced comics while living in Japan in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[88] Others include Frank Miller's mid-1980s Ronin, Adam Warren and Toren Smith's 1988 The Dirty Pair,[89] Ben Dunn's 1987 Ninja High School and Manga Shi 2000 from Crusade Comics (1997).

By the 21st century several U.S. manga publishers had begun to produce work by U.S. artists under the broad marketing-label of manga.[90] In 2002 I.C. Entertainment, formerly Studio Ironcat and now out of business, launched a series of manga by U.S. artists called Amerimanga.[91] In 2004 eigoMANGA launched the Rumble Pak and Sakura Pakk anthology series. Seven Seas Entertainment followed suit with World Manga.[92] Simultaneously, TokyoPop introduced original English-language manga (OEL manga) later renamed Global Manga.[93]

Francophone artists have also developed their own versions of manga (manfra), like Frédéric Boilet's la nouvelle manga. Boilet has worked in France and in Japan, sometimes collaborating with Japanese artists.[94]

Awards

The Japanese manga industry grants a large number of awards, mostly sponsored by publishers, with the winning prize usually including publication of the winning stories in magazines released by the sponsoring publisher. Examples of these awards include:

- the Akatsuka Award for humorous manga

- the Dengeki Comic Grand Prix for one-shot manga

- the Japan Cartoonists Association Award various categories

- the Kodansha Manga Award (multiple genre awards)

- the Seiun Award for best science fiction comic of the year

- the Shogakukan Manga Award (multiple genres)

- the Tezuka Award for best new serial manga

- the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize (multiple genres)

The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has awarded the International Manga Award annually since May 2007.[95]

University education

Kyoto Seika University in Japan has offered a highly competitive course in manga since 2000.[96][97] Then, several established universities and vocational schools (専門学校: Semmon gakkou) established a training curriculum.

Shuho Sato, who wrote Umizaru and Say Hello to Black Jack, has created some controversy on Twitter. Sato says, "Manga school is meaningless because those schools have very low success rates. Then, I could teach novices required skills on the job in three months. Meanwhile, those school students spend several million yen, and four years, yet they are good for nothing." and that, "For instance, Keiko Takemiya, the then professor of Seika Univ., remarked in the Government Council that 'A complete novice will be able to understand where is "Tachikiri" (i.e., margin section) during four years.' On the other hand, I would imagine that, It takes about thirty minutes to completely understand that at work."[98]

See also

- Emakimono / Etoki (horizontal, illustrated narrative form)

- Japanese popular culture

- Kamishibai

- Lianhuanhua (small Chinese picture book)

- Light novel

- List of best-selling manga

- List of films based on manga

- List of licensed manga in English

- List of manga distributors

- Manga iconography

- Oekaki (act of drawing)

- Q-version (cartoonification)

- Ukiyo-e

- Visual novel

Footnotes

- ^ Lent 2001, pp. 3–4, Gravett 2004, p. 8

- ^ Kern 2006, Ito 2005, Schodt 1986

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2009

- ^ Gravett 2004, p. 8

- ^ Kinsella 2000, Schodt 1996

- ^ Saira Syed (18 August 2011). "Comic giants battle for readers". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ Wong 2006, Patten 2004

- ^ a b Danica Davidson (26 January 2012). "Manga grows in the heart of Europe". Geek Out! CNN. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ Katzenstein & Shiraishi 1997

- ^ a b Gravett 2004, p. 8, Schodt 1986

- ^ Kinsella 2000

- ^ Kittelson 1998

- ^ Johnston-O'Neill 2007

- ^ Webb 2006

- ^ Wong 2002

- ^ Rousmaniere 2001, p. 54, Thompson 2007, p. xvi, Prohl & Nelson 2012, p. 596,Fukushima 2013, p. 19

- ^ Webb 2006,Thompson 2007, p. xvi,Onoda 2009, p. 10,Petersen 2011, p. 120

- ^ Prohl & Nelson 2012, p. 596,McCarthy 2014, p. 6

- ^ "Santō Kyōden's picturebooks".

- ^ "Shiji no yukikai(Japanese National Diet Library)".

- ^ Bouquillard & Marquet 2007

- ^ Shimizu 1985, pp. 53–54, 102–103

- ^ "Inu Yasha Ani-MangaGraphic Novels". Animecornerstore.com. 1 November 1999. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kinsella 2000, Schodt 1986

- ^ Schodt 1986, Ito 2004, Kern 2006, Kern 2007

- ^ Schodt 1986, Schodt 1996, Schodt 2007, Gravett 2004

- ^ Kodansha 1999, pp. 692–715, Schodt 2007

- ^ Schodt 1986

- ^ Gravett 2004, p. 8, Lee 2000, Sanchez 1997–2003

- ^ Schodt 1986, Toku 2006

- ^ Gravett 2004, pp. 78–80, Lent 2001, pp. 9–10

- ^ Schodt 1986, Toku 2006, Thorn 2001

- ^ Ōgi 2004

- ^ Gravett 2004, p. 8, Schodt 1996

- ^ Drazen 2003

- ^ Allison 2000, pp. 259–278, Schodt 1996, p. 92

- ^ Poitras 2001

- ^ Thompson 2007, pp. xxiii–xxiv

- ^ Brenner 2007, pp. 31–34

- ^ Schodt 1996, p. 95, Perper & Cornog 2002

- ^ Schodt 1986, pp. 68–87, Gravett 2004, pp. 52–73

- ^ Schodt 1986, pp. 68–87

- ^ Perper & Cornog 2002, pp. 60–63

- ^ Gardner 2003

- ^ Perper & Cornog 2002

- ^ http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/dy/national/T101213003771.htm

- ^ Schodt 1986, pp. 68–73, Gravett 2006

- ^ Schodt 1986, pp. 68–73, Gravett 2004, pp. 38–42, Isao 2001

- ^ Isao 2001, pp. 147–149, Nunez 2006

- ^ a b Cube 2007

- ^ a b Manga Industry in Japan

- ^ Schodt 1996

- ^ Manga Museum 2009

- ^ Schodt 1996, p. 101

- ^ Eshinbun Nipponchi

- ^ Griffiths 2007

- ^ a b Poten

- ^ a b c Shonen Pakku

- ^ Lone 2007, p. 75

- ^ Manga no Kuni

- ^ Pink 2007, Wong 2007

- ^ a b Farago 2007

- ^ Randal, Bill (2005). "English, For Better or Worse". The Comics Journal (Special ed.). Fantagraphics Books.

- ^ a b Fishbein 2007

- ^ Berger 1992

- ^ Vollmar 2007

- ^ Mahousu 2005

- ^ Mahousu 2005, ANN 2004, Riciputi 2007

- ^ Brigid Alverson (12 February 2014). "Strong French Manga Market Begins to Dip". publishersweekly.com. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Rich Johnston (1 January 2014). "French Comics In 2013 – It's Not All Asterix. But Quite A Bit Is". bleedingcool.com. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Jennifer Fishbein (27 December 2007). "Europe's Manga Mania". Spiegel Online International. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Patten 2004

- ^ In 1987, "...Japanese comics were more legendary than accessible to American readers", Patten 2004, p. 259

- ^ Napier 2000, pp. 239–256, Clements & McCarthy 2006, pp. 475–476

- ^ Patten 2004, Schodt 1996, pp. 305–340, Leonard 2004

- ^ Schodt 1996, p. 309, Rifas 2004, Rifas adds that the original EduComics titles were Gen of Hiroshima and I SAW IT [sic].

- ^ Patten 2004, pp. 37, 259–260, Thompson 2007, p. xv

- ^ Leonard 2004, Patten 2004, pp. 52–73, Farago 2007

- ^ Schodt 1996, pp. 318–321, Dark Horse Comics 2004

- ^ Brienza, Casey E. (2009). "Books, Not Comics: Publishing Fields, Globalization, and Japanese Manga in the United States". Publishing Research Quarterly. 25 (2): 101–117. doi:10.1007/s12109-009-9114-2.

- ^ Kwok Wah Lau, Jenny (2003). "4". Multiple modernities: cinemas and popular media in transcultural East Asia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 78.

- ^ Patten 2004, pp. 50, 110, 124, 128, 135, Arnold 2000

- ^ Schodt 1996, p. 95

- ^ Arnold 2000, Farago 2007, Bacon 2005

- ^ Schodt 1996, pp. 308–319

- ^ Reid 2009

- ^ Glazer 2005, Masters 2006, Bosker 2007, Pink 2007

- ^ Stewart 1984

- ^ Crandol 2002

- ^ Tai 2007

- ^ ANN 2002

- ^ ANN & 10 May 2006

- ^ ANN & 5 May 2006

- ^ Boilet 2001, Boilet & Takahama 2004

- ^ ANN 2007, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2007

- ^ Obunsha Co.,Ltd. (18 July 2014). 京都精華大学、入試結果 (倍率)、マンガ学科。 (in Japanese). Obunsha Co.,Ltd. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Kyoto Seika University. "Kyoto Seika University, Faculty of Manga". Kyoto Seika University. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Shuho Sato; et al. (26 July 2012). 漫画を学校で学ぶ意義とは (in Japanese). togetter. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

References

- Allison, Anne (2000). "Sailor Moon: Japanese superheroes for global girls". In Craig, Timothy J. (ed.). Japan Pop! Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0561-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Arnold, Adam (2000). "Full Circle: The Unofficial History of MixxZine". Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bacon, Michelle (14 April 2005). "Tangerine Dreams: Guide to Shoujo Manga and Anime". Retrieved 1 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Berger, Klaus (1992). Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37321-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boilet, Frédéric (2001). Yukiko's Spinach. Castalla-Alicante, Spain: Ponent Mon. ISBN 84-933093-4-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boilet, Frédéric; Takahama, Kan (2004). Mariko Parade. Castalla-Alicante, Spain: Ponent Mon. ISBN 84-933409-1-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bosker, Bianca (31 August 2007). "Manga Mania". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bouquillard, Jocelyn; Marquet, Christophe (1 June 2007). Hokusai: First Manga Master. New York: Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-9341-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brenner, Robin E. (2007). Understanding Manga and Anime. Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited/Greenwood. ISBN 978-1-59158-332-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clements, Jonathan; McCarthy, Helen (2006). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917, Revised and Expanded Edition. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-933330-10-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crandol, Mike (14 January 2002). "The Dirty Pair: Run from the Future". Anime News Network. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cube (18 December 2007). 2007年のオタク市場規模は1866億円―メディアクリエイトが白書 (in Japanese). Inside for All Games. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Dark Horse buys Studio Proteus" (Press release). Dark Horse Comics. 6 February 2004.

- Drazen, Patrick (2003). Anime Explosion! The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge. ISBN 978-1-880656-72-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farago, Andrew (30 September 2007). "Interview: Jason Thompson". The Comics Journal. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fishbein, Jennifer (26 December 2007). "Europe's Manga Mania". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fukushima, Yoshiko (2013). Manga Discourse in Japan Theatre. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 9781136772733.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gardner, William O. (November 2003). "Attack of the Phallic Girls". Science Fiction Studies (88). Retrieved 5 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glazer, Sarah (18 September 2005). "Manga for Girls". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gravett, Paul (2004). Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. New York: Harper Design. ISBN 1-85669-391-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gravett, Paul (15 October 2006). "Gekiga: The Flipside of Manga". Retrieved 4 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Griffiths, Owen (22 September 2007). "Militarizing Japan: Patriotism, Profit, and Children's Print Media, 1894–1925". Japan Focus. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Isao, Shimizu (2001). "Red Comic Books: The Origins of Modern Japanese Manga". In Lent, John A. (ed.). Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2471-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ito, Kinko (2004). "Growing up Japanese reading manga". International Journal of Comic Art (6): 392–401.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ito, Kinko (2005). "A history of manga in the context of Japanese culture and society". The Journal of Popular Culture. 38 (3): 456–475. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.2005.00123.x. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnston-O'Neill, Tom (3 August 2007). "Finding the International in Comic Con International". The San Diego Participant Observer. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Katzenstein, Peter J.; Shiraishi, Takashi (1997). Network Power: Japan in Asia. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8373-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kern, Adam (2006). Manga from the Floating World: Comicbook Culture and the Kibyōshi of Edo Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02266-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kern, Adam (2007). "Symposium: Kibyoshi: The World's First Comicbook?". International Journal of Comic Art (9): 1–486.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kinsella, Sharon (2000). Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2318-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kittelson, Mary Lynn (1998). The Soul of Popular Culture: Looking at Contemporary Heroes, Myths, and Monsters. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9363-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lee, William (2000). "From Sazae-san to Crayon Shin-Chan". In Craig, Timothy J. (ed.). Japan Pop!: Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0561-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lent, John A. (2001). Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2471-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leonard, Sean (12 September 2004). "Progress Against the Law: Fan Distribution, Copyright, and the Explosive Growth of Japanese Animation" (PDF). Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lone, Stewart (2007). Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia: From the Taiping Rebellion to the Vietnam War. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-33684-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mahousu (January 2005). "Les editeurs des mangas". self-published. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[unreliable source?] - Masters, Coco (10 August 2006). "America is Drawn to Manga". Time Magazine.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "First International MANGA Award" (Press release). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 29 June 2007.

{{cite press release}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McCarthy, Helen (2014). A Brief History of Manga: The Essential Pocket Guide to the Japanese Pop Culture Phenomenon. Hachette UK. p. 6. ISBN 9781781571309.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Napier, Susan J. (2000). Anime: From Akira to Princess Mononoke. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-23863-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nunez, Irma (24 September 2006). "Alternative Comics Heroes: Tracing the Genealogy of Gekiga". The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ōgi, Fusami (2004). "Female subjectivity and shōjo (girls) manga (Japanese comics): shōjo in Ladies' Comics and Young Ladies' Comics". The Journal of Popular Culture. 36 (4): 780–803. doi:10.1111/1540-5931.00045.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Onoda, Natsu (2009). God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga. University Press of Mississippi. p. 10. ISBN 9781604734782.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Patten, Fred (2004). Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-92-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Perper, Timothy; Cornog, Martha (2002). "Eroticism for the masses: Japanese manga comics and their assimilation into the U.S.". Sexuality & Culture. 6 (1): 3–126. doi:10.1007/s12119-002-1000-4.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Perper, Timothy; Cornog, Martha (2003). "Sex, love, and women in Japanese comics". In Francoeur, Robert T.; Noonan, Raymond J. (eds.). The Comprehensive International Encyclopedia of Sexuality. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1488-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Petersen, Robert S. (2011). Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313363306.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Prohl, Inken; Nelson, John K (2012). Handbook of Contemporary Japanese Religions. BRILL. p. 596. ISBN 9789004234352.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pink, Daniel H. (22 October 2007). "Japan, Ink: Inside the Manga Industrial Complex". Wired. 15 (11). Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Poitras, Gilles (2001). Anime Essentials: Every Thing a Fan Needs to Know. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge. ISBN 978-1-880656-53-2.

- Reid, Calvin (28 March 2006). "HarperCollins, Tokyopop Ink Manga Deal". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reid, Calvin (6 February 2009). "2008 Graphic Novel Sales Up 5%; Manga Off 17%". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Riciputi, Marco (25 October 2007). "Komikazen: European comics go independent". Cafebabel.com. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[unreliable source?] - Rifas, Leonard (2004). "Globalizing Comic Books from Below: How Manga Came to America". International Journal of Comic Art. 6 (2): 138–171.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rousmaniere, Nicole (2001). Births and Rebirths in Japanese Art : Essays Celebrating the Inauguration of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures. Hotei Publishing. ISBN 978-9074822442.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sanchez, Frank (1997–2003). "Hist 102: History of Manga". AnimeInfo. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schodt, Frederik L. (1986). Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. Tokyo: Kodansha. ISBN 978-0-87011-752-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schodt, Frederik L. (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-23-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schodt, Frederik L. (2007). The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-933330-54-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shimizu, Isao (June 1985). 日本漫画の事典 : 全国のマンガファンに贈る (Nihon Manga no Jiten – Dictionary of Japanese Manga) (in Japanese). Sun lexica. ISBN 4-385-15586-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stewart, Bhob (October 1984). "Screaming Metal". The Comics Journal (94).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tai, Elizabeth (23 September 2007). "Manga outside Japan". Star Online. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tchiei, Go (1998). "Characteristics of Japanese Manga". Retrieved 5 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Jason (2007). Manga: The Complete Guide. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-48590-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thorn, Matt (July–September 2001). "Shôjo Manga—Something for the Girls". The Japan Quarterly. 48 (3). Retrieved 5 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toku, Masami (Spring 2006). "Shojo Manga: Girl Power!". Chico Statements. California State University, Chico. ISBN 1-886226-10-5. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vollmar, Rob (1 March 2007). "Frederic Boilet and the Nouvelle Manga revolution". World Literature Today. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Webb, Martin (28 May 2006). "Manga by any other name is..." The Japan Times. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wong, Wendy Siuyi (2002). Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-269-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wong, Wendy Siuyi (2006). "Globalizing manga: From Japan to Hong Kong and beyond". Mechademia: an Annual Forum for Anime, Manga, and the Fan Arts. pp. 23–45.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wong, Wendy (September 2007). "The Presence of Manga in Europe and North America". Media Digest. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "About Manga Museum: Current situation of manga culture". Kyoto Manga Museum. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- "Correction: World Manga". Anime News Network. 10 May 2006. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- "I.C. promotes AmeriManga". Anime News Network. 11 November 2002. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- "Interview with Tokyopop's Mike Kiley". ICv2. 7 September 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Japan: Profile of a Nation, Revised Edition. Tokyo: Kodansha International. 1999. ISBN 4-7700-2384-7.

- "Japan's Foreign Minister Creates Foreign Manga Award". Anime News Network. 22 May 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- "manga". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- "Manga-mania in France". Anime News Network. 4 February 2004. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- "'Manga no Kuni': A manga magazine from the Second Sino-Japanese War period". Kyoto International Manga Museum. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- "'Poten': a manga magazine from Kyoto". Kyoto International Manga Museum. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- "'Shonen Pakku'; Japan's first children's manga magazine". Kyoto International Manga Museum. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- "The first Japanese manga magazine: Eshinbun Nipponchi". Kyoto International Manga Museum. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- "Tokyopop To Move Away from OEL and World Manga Labels". Anime News Network. 5 May 2006. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

Further reading

- "Japanese Manga Market Drops Below 500 Billion Yen". ComiPress. 10 March 2007.

- "Un poil de culture – Une introduction à l'animation japonaise" (in French). 11 July 2007.

Hattie Jones: 'Manga girls: Sex, love, comedy and crime in recent boy's manga and anime', in Brigitte Steger and Angelika Koch (2013 eds): Manga Girl Seeks Herbivore Boy. Studying Japanese Gender at Cambridge. Lit Publisher, pp. 24–81.

- Template:It icon Marcella Zaccagnino and Sebastiano Contrari. "Manga: il Giappone alla conquista del mondo" (Archive) Limes, rivista italiana di geopolitica. 31/10/2007.