Essen

Essen | |

|---|---|

Skyline of Essen | |

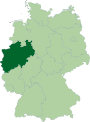

| Country | Germany |

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Admin. region | Düsseldorf |

| District | Urban district |

| Subdivisions | 9 districts, 50 boroughs |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor | Thomas Kufen (CDU) |

| Area | |

• City | 210.32 km2 (81.21 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 116 m (381 ft) |

| Population (2023-12-31)[1] | |

• City | 586,608 |

| • Density | 2,800/km2 (7,200/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 5.302.179 |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 45001–45359 |

| Dialling codes | 0201, 02054 (Kettwig) |

| Vehicle registration | E |

| Website | www.essen.de |

Essen (German pronunciation: [ˈʔɛsn̩] ; Latin: Assindia) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Its population of approximately 589,000 (as of 31 March 2016[update]) makes it the ninth-largest city in Germany. It is the central city of the northern (Ruhr) part of the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan area and seat to several of the region's authorities.

Founded around 845, Essen remained a small town within the sphere of influence of an important ecclesiastical principality (Essen Abbey) until the onset of industrialization. The city then — especially through the Krupp family iron works — became one of Germany's most important coal and steel centers. Essen, until the 1970s, attracted workers from all over the country; it was the 5th-largest city in Germany between 1929 and 1988, peaking at over 730,000 inhabitants in 1962. Following the region-wide decline of heavy industries in the last decades of the 20th century, the city has seen the development of a strong tertiary sector of the economy. Essen today is seat to 13 of the 100 largest German corporations, including two (by 2016, three [3]) DAX corporations, placing the city second only to Munich and on-par with Frankfurt am Main in number of corporate headquarters.

Although it is the (in total) most indebted city in Germany,[4] Essen continues to pursue its redevelopment plans. Notable accomplishments in recent years include the title of European Capital of Culture on behalf of the whole Ruhr area in 2010 and the selection as the European Green Capital for 2017.[5]

In 1958, Essen was chosen to serve as the seat to a Roman Catholic diocese (often referred to as Ruhrbistum or diocese of the Ruhr). In early 2003, the universities of Essen and the nearby city of Duisburg (both established in 1972) were merged into the University of Duisburg-Essen with campuses in both cities and a university hospital in Essen.

Geography

General

Oberhausen |

Bottrop |

Gladbeck1 |

Gelsenkirchen |

Mülheim an der Ruhr |

(Map of districts and boroughs) |

Bochum | |

Ratingen² |

Heiligenhaus² |

Velbert² |

Hattingen³ |

| 1 Recklinghausen district 2 Mettmann district 3 Ennepe-Ruhr district | |||

Essen is located in the centre of the Ruhr area, one of the largest urban areas in Europe (see also: megalopolis), comprising eleven independent cities and four districts with some 5.3 million inhabitants. The city limits of Essen itself are 87 km (54 mi) long and border ten cities, five independent and five kreisangehörig (i.e., belonging to a district), with a total population of approximately 1.4 million. The city extends over 21 km (13 mi) from north to south and 17 km (11 mi) from west to east, mainly north of the River Ruhr.

The Ruhr forms the Lake Baldeney reservoir in the boroughs of Fischlaken, Kupferdreh, Heisingen and Werden. The lake, a popular recreational area, dates from 1931 to 1933, when some thousands of unemployed coal miners dredged it with primitive tools . Generally, large areas south of the River Ruhr (including the suburbs of Schuir and Kettwig) are quite green and are often quoted as examples of rural structures in the otherwise relatively densely populated central Ruhr area. According to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany, Essen with 9.2% of its area covered by recreational green is the greenest city in North Rhine-Westphalia [6] and the third-greenest city in Germany.[7] The city has been shortlisted for the title of European Green Capital two consecutive times, for 2016 and 2017, winning for 2017.[8] The city was singled out for its exemplary practices in protecting and enhancing nature and biodiversity and efforts to reduce water consumption. Essen participates in a variety of networks and initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to improve the city’s resilience in the face of climate change.

The lowest point can be found in the northern borough of Karnap at 26.5 m (86.9 ft), the highest point in the borough of Heidhausen at 202.5 m (664 ft). The average elevation is 116 m (381 ft).

City districts

Essen comprises fifty boroughs which in turn are grouped into nine suburban districts (called Stadtbezirke) often named after the most important boroughs. Each Stadtbezirk is assigned a Roman numeral and has a local body of nineteen members with limited authority. Most of the boroughs were originally independent municipalities but were gradually annexed from 1901 to 1975. This long-lasting process of annexation has led to a strong identification of the population with "their" boroughs or districts and to a rare peculiarity: The borough of Kettwig, located south of the Ruhr River, and which was not annexed until 1975, has its own area code. Additionally (allegedly due to relatively high church tax incomes), the Archbishop of Cologne managed to keep Kettwig directly subject to the Archdiocese of Cologne, whereas all other boroughs of Essen and some neighboring cities constitute the Diocese of Essen.

- For a list of all boroughs of the city, see the section Boroughs of Essen below.

Climate

Essen has a temperate–Oceanic climate with relatively mild winters and cool summers. Its average annual temperature is 10 °C (50 °F): 13.3 °C (56 °F) during the day and 6.7 °C (44 °F) at night. The average annual precipitation is 934 mm (37 in). The coldest month of the year is January, when the average temperature is 2.4 °C (36 °F). The warmest months are July and August, with an average temperature of 18 °C (64 °F). The record high is 36.6 °C (98 °F) and the record low is −24 °C (−11 °F).[10]

| Climate data for Essen | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.7 (51.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

0.3 (32.5) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.6 (45.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 84.5 (3.33) |

58.1 (2.29) |

78.2 (3.08) |

61.0 (2.40) |

72.2 (2.84) |

92.8 (3.65) |

81.2 (3.20) |

78.8 (3.10) |

78.0 (3.07) |

75.1 (2.96) |

81.1 (3.19) |

93.1 (3.67) |

934.1 (36.78) |

| Average precipitation days | 14.1 | 10.5 | 13.6 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 13.6 | 14.1 | 142.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 82 | 78 | 75 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 80 | 79 | 81 | 82 | 80 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 43.4 | 78.3 | 102.3 | 147.0 | 192.2 | 183.0 | 186.0 | 182.9 | 135.0 | 111.6 | 57.0 | 40.3 | 1,459 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[11] Hong Kong Observatory[12] for data of sunshine hours | |||||||||||||

History

Origin of the name

In German-speaking countries, the name of the city Essen often causes confusion as to its origins, because it is commonly known as the German infinitive of the verb for "eating" (written as lowercase essen), and/or the German noun for food (which is always capitalized as Essen, adding to the confusion). Although scholars still dispute the interpretation of the name,[13] there remain a few noteworthy interpretations. The oldest known form of the city's name is Astnide, which changed to Essen by way of forms such as Astnidum, Assinde, Essendia and Esnede. The name Astnide may have referred either to a region where many ash trees were found or to a region in the East (of the Frankish Empire).[14] The Old High German word for fireplace, Esse, is also commonly mentioned due to the industrial history of the city, but is highly unlikely since the old forms of the city name originate from times before industrialization.

Early history

The oldest archaeological find, the Vogelheimer Klinge, dates back to 280,000 – 250,000 BC. It is a blade found in the borough of Vogelheim in the northern part of the city during the construction of the Rhine–Herne Canal in 1926.[15] Other artifacts from the Stone Age have also been found, although these are not overly numerous. Land utilization was very high – especially due to mining activities during the Industrial Age – and any more major finds, especially from the Mesolithic era, are not expected. Finds from 3,000 BC and onwards are far more common, the most important one being a Megalithic tomb found in 1937. Simply called Steinkiste (Chest of Stone), it is referred to as "Essen's earliest preserved example of architecture".[16]

Essen was part of the settlement areas of several Germanic peoples (Chatti, Bructeri, Marsi), although a clear distinction among these groupings is difficult.

The Alteburg castle in the south of Essen dates back to the 1st or 2nd century BC, the Herrenburg to the 8th century AD.

Recent research into Ptolemy's Geographia has identified the polis or oppidum Navalia as Essen.[17]

8th–12th centuries

Around 845, Saint Altfrid (around 800–874), the later Bishop of Hildesheim, founded an abbey for women (coenobium Astnide) in the centre of present-day Essen. The first abbess was Altfrid's relative Gerswit (see also: Essen Abbey). In 799, Saint Liudger had already founded Benedictine Werden Abbey on its own grounds a few kilometers south. The region was sparsely populated with only a few smallholdings and an old and probably abandoned castle. Whereas Werden Abbey sought to support Liudger's missionary work in the Harz region (Helmstedt/Halberstadt), Essen Abbey was meant to care for women of the higher Saxon nobility. This abbey was not an abbey in the ordinary sense, but rather intended as a residence and educational institution for the daughters and widows of the higher nobility; led by an abbess, the members other than the abbess herself were not obliged to take vows of chastity.

Around 852, construction of the collegiate church of the abbey began, to be completed in 870. A major fire in 946 heavily damaged both the church and the settlement. The church was rebuilt, expanded considerably, and is the foundation of the present Essen Cathedral.

The first documented mention of Essen dates back to 898, when Zwentibold, King of Lotharingia, willed territory on the western bank of the River Rhine to the abbey. Another document, describing the foundation of the abbey and allegedly dating back to 870, is now considered an 11th-century forgery.

In 971, Mathilde II, granddaughter of Emperor Otto I, took charge of the abbey. She was to become the most important of all abbesses in the history of Essen. She reigned for over 40 years, and endowed the abbey's treasury with invaluable objects such as the oldest preserved seven branched candelabrum, and the Golden Madonna of Essen, the oldest known sculpture of the Virgin Mary in the western world. Mathilde was succeeded by other women related to the Ottonian emperors: Sophia, daughter of Otto II and sister of Otto III, and Teophanu, granddaughter of Otto II. It was under the reign of Teophanu that Essen, which had been called a city since 1003, received the right to hold markets in 1041. Ten years later, Teophanu had the eastern part of Essen Abbey constructed. Its crypt contains the tombs of St. Altfrid, Mathilde II, and Teophanu herself.

13th–17th centuries

In 1216, the abbey, which had only been an important landowner until then, gained the status of a princely residence when Emperor Frederick II called abbess Elisabeth I Reichsfürstin (Princess of the Empire) in an official letter. In 1244, 28 years later, Essen received its town charter and seal when Konrad von Hochstaden, the Archbishop of Cologne, marched into the city and erected a city wall together with the population. This proved a temporary emancipation of the population of the city from the princess-abbesses, but this lasted only until 1290. That year, King Rudolph I restored the princess-abbesses to full sovereignty over the city, much to the dismay of the population of the growing city, who called for self-administration and imperial immediacy. The title free imperial city was finally granted by Emperor Charles IV in 1377. However, in 1372, Charles had paradoxically endorsed Rudolph I's 1290 decision and hence left both the abbey and the city in imperial favour. Disputes between the city and the abbey about supremacy over the region remained common until the abbey's dissolution in 1803. Many lawsuits were filed at the Reichskammergericht, one of them lasting almost 200 years. The final decision of the court in 1670 was that the city had to be "duly obedient in dos and don'ts" to the abbesses but could maintain its old rights—a decision that did not really solve any of the problems.

In 1563, the city council, with its self-conception as the only legitimate ruler of Essen, introduced the Protestant Reformation. The Catholic abbey had no troops to counter this development.

Thirty Years' War

During the Thirty Years' War, the Protestant city and the Catholic abbey opposed each other. In 1623, princess-abbess Maria Clara von Spaur, Pflaum und Valör, managed to direct Catholic Spaniards against the city in order to initiate a Counter-Reformation. In 1624, a "re-Catholicization" law was enacted, and churchgoing was strictly controlled. In 1628, the city council filed against this at the Reichskammergericht. Maria had to flee to Cologne when the Dutch stormed the city in 1629. She returned in the summer of 1631 following the Bavarians under Gottfried Heinrich Graf zu Pappenheim, only to leave again in September. She died 1644 in Cologne.

The war proved a severe blow to the city, with frequent arrests, kidnapping and rape. Even after the Peace of Westphalia from 1648, troops remained in the city until 9 September 1650.

Industrialisation

The first historic evidence of the important mining tradition of Essen date back to the 14th century, when the princess-abbess was granted mining rights. The first silver mine opened in 1354, but the indisputably more important coal was not mentioned until 1371, and coal mining only began in 1450.

At the end of the 16th century, many coal mines had opened in Essen, and the city earned a name as a centre of the weapons industry. Around 1570, gunsmiths made high profits and in 1620, they produced 14,000 rifles and pistols a year. The city became increasingly important strategically.

Resident in Essen since the 16th century, the Krupp family dynasty and Essen shaped each other. In 1811, Friedrich Krupp founded Germany's first cast-steel factory in Essen and laid the cornerstone for what was to be the largest enterprise in Europe for a couple of decades. The weapon factories in Essen became so important that a sign facing the main railway station welcomed visitor Benito Mussolini to the "Armory of the Reich" in 1937.[18] The Krupp Works also were the main reason for the large population growth beginning in the mid-19th century. Essen reached a population of 100,000 in 1896. Other industrialists, such as Friedrich Grillo, who in 1892 donated the Grillo-Theater to the city, also played a major role in the shaping of the city and the Ruhr area in the late 19th and early 20th century.

First World War

Riots broke out in February 1917 following a breakdown in the supply of flour. There were then strikes in the Krupp factory.[19]

Occupation of the Ruhr

On January 11, 1923, the Occupation of the Ruhr was carried out by the invasion of French and Belgian troops into the Ruhr. The French Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré was convinced that Germany failed to comply the demands of the Treaty of Versailles. On the morning of March 31, 1923 it came to the sad culmination of this French-German confrontation.[20] A small French military command, occupied the Krupp car hall to seize there several vehicles. This event called 13 deaths and 28 injured. The occupation of the Ruhr ended in summer 1925.

Phase of the Nazi seizure of power in 1933–34

Heinrich Maria Martin Schäfer was appointed mayor of Essen on December 21, 1932. After the Nazi seizure of power Theodor Reismann-Grone became on April 5, 1933 the mayor. Essen was then divided in 27 local NSDAP groups (NSDAP-Ortsgruppe).[21]

1938 November Pogrom

On the night of 10 November 1938, the synagogue was sacked, but remained through the whole war in the exterior almost intact.[22] The Steele synagogue was completely destroyed.

Forced labor camps and concentration camps

Tens of thousands of forced laborers arrived in the Nazi era in 350 Essen camps, forced to Forced labour under German rule during World War II at companies like Krupp, Siemens and for mining work.[23][24] In Essen there were in Second World War several Subcamps as the subcamp Humboldtstraße, the Gelsenberg subcamp and the subcamp Schwarze Poth.

Second World War

As a major industrial centre, Essen was a target for allied bombing, the Royal Air Force (RAF) dropping a total of 36,429 long tons of bombs on the city.[25] Over 270 air raids were launched against the city, destroying 90% of the centre and 60% of the suburbs.[26] On 5 March 1943 Essen was subjected to one of the heaviest air-raids of the war. 461 people were killed, 1,593 injured and a further 50,000 residents of Essen were made homeless.[27] On 13 December 1944 three British airmen were lynched.[28]

The Allied ground advance into Germany reached Essen in April 1945. The US 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 17th Airborne Division, acting as regular infantry and not in a parachute role, entered the city unopposed and captured it on 10 April 1945.[29]

Under British occupation

After the successful invasion of Germany by the allies, Essen was assigned to the British Zone of Occupation. On 8 March 1946, a German Army Officer and a civilian were hanged for the lynching of three British Airmen in December 1944.

Twenty-first century

Although no weaponry is produced in Essen any more, old industrial enterprises such as ThyssenKrupp and RWE remain large employers in the city. Foundations such as the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung still promote the well-being of the city, for example by supporting a hospital and donating €55,000,000 for a new building for the Museum Folkwang, one of the Ruhr area's major art museums.

| Largest groups of foreign residents[30] | |

| Nationality | Population (2014) |

|---|---|

| 15,280 | |

| 6,315 | |

| 2,796 | |

| 2,739 | |

| 2,723 | |

| 2,505 | |

| 2,443 | |

| 2,435 | |

| 1,989 | |

| 1,711 | |

Politics

Historical development

The administration of Essen had for a long time been in the hands of the princess-abbesses as heads of the Imperial Abbey of Essen. However, from the 14th century onwards, the city council increasingly grew in importance. In 1335, it started choosing two burgomasters, one of whom was placed in charge of the treasury. In 1377, Essen was granted imperial immediacy [31] but had to abandon this privilege later on. Between the early 15th and 20th centuries, the political system of Essen underwent several changes, most importantly the introduction of the Protestant Reformation in 1563, the annexation of 1802 by Prussia, and the subsequent secularization of the principality in 1803. The territory was made part of the Prussian Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg from 1815 to 1822, after which it became part of the Prussian Rhine Province until its dissolution in 1946.

During the German Revolution of 1918–19, Essen was the home of the Essen Tendency (Essener Richtung) within the Communist Workers' Party of Germany. In 1922 they founded the Communist Workers' International. Essen became one of the centres of resistance to Social Democracy and the Freikorps alike.

During the Nazi era (1933–1945), mayors were installed by the Nazi Party. After World War II, the military government of the British occupation zone installed a new mayor and a municipal constitution modeled on that of British cities. Later, the city council was again elected by the population. The mayor was elected by the council as its head and as the city's main representative. The administration was led by a full-time Oberstadtdirektor. In 1999, the position of Oberstadtdirektor was abolished in North Rhine-Westphalia and the mayor became both main representative and administrative head. In addition, the population now elects the mayor directly.

City council

The last local elections took place on 27.September 2015. Thomas Kufen (CDU) was elected Lord Mayor[32] and the following political parties gained seats in the city council:

| SPD (Social Democrats) |

CDU (Christian Democrats) |

GRÜNE (Greens) |

FDP Alternative Essen (Liberals) |

The Left (Left-wing) |

Essener Bürgerbündnis (Independent) |

REP (National Conservatives) |

NPD (Far right-wing) |

Essen steht AUF (MLPD) (Marxist–Leninists) |

Total |

| 34 | 31 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 90 |

The city is governed by a coalition of SPD and CDU.

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of the city of Essen is a heraldic peculiarity. Granted in 1886, it is a so-called Allianzwappen (arms of alliance) and consists of two separate shields under a single crown. Most other coats of arms of cities show a wall instead of a crown. The crown, however, does not refer to the city of Essen itself, but instead to the secularized ecclesiastical principality of Essen under the reign of the princess-abbesses. The dexter (heraldically right) escutcheon shows the double-headed Imperial Eagle of the Holy Roman Empire, granted to the city in 1623. The sinister (heraldically left) escutcheon is one of the oldest emblems of Essen and shows a sword that people believed was used to behead the city's patron Saints Cosmas and Damian. People tend to connect the sword in the left shield with one found in the Cathedral Treasury. This sword, however, is much more recent.[33] A slightly modified and more heraldically correct version of the coat of arms can be found on the roof of the Handelshof hotel near the main station.

International relations

- Grenoble, France (since 1974)[34][35][36]

- Nizhny Novgorod, Russia (since 1991)[34]

- City of Sunderland, United Kingdom (since 1949)[34]

- Tampere, Finland (since 1960)[34]

- Tel Aviv, Israel (since 1991)[34]

The City of Monessen, Pennsylvania, situated along the Monongahela River, was named after the river and Essen.[37]

There are cooperations with the following cities:[34]

Industry and infrastructure

Major companies based in Essen

Essen is seat to several large companies, among them the ThyssenKrupp industrial conglomerate which is also registered in Duisburg and originates from a 1999 merger between Duisburg-based Thyssen AG and Essen-based Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp. The largest company registered only in Essen is Germany's second-largest electric utility RWE AG. Essen also hosts parts of the corporate headquarters of Schenker AG, the logistics division of Deutsche Bahn. Other major companies include Germany's largest construction company Hochtief AG, as well as Aldi Nord, Evonik Industries, Karstadt, Medion AG and Deichmann, Europe's largest shoe retailer. The Coca-Cola Company had also originally established their German headquarters in Essen (around 1930), where it remained until 2003, when it was moved to the capital Berlin. In light of the Energy transition in Germany, Germany's largest electric utility E.ON announced that, after restructuring and splitting off its conventional electricity generation division (coal, gas, atomic energy), it will also move its headquarters to Essen in 2016, becoming a sole provider of renewable energy.[38] Further the chemical distribution company Brenntag announced to move its headquarter to Essen end of 2017.

Fairs

The city's exhibition centre, Messe Essen, hosts some 50 trade fairs each year. With around 530.000 visitors each year, Essen Motor Show is by far the largest event held there. Other important fairs open to consumers include SPIEL, the world's biggest consumer fair for gaming, and one of the leading fairs for equestrian sports, Equitana, held every two years. Important fairs restricted to professionals include "Security" (security and fire protection), IPM (gardening) and E-World (energy and water).

Media

The Westdeutscher Rundfunk has a studio in Essen, which is responsible for the central Ruhr area. Each day, it produces a 30-minute regional evening news magazine (called Lokalzeit Ruhr), a 5-minute afternoon news programme, and several radio news programmes. A local broadcasting station went on air in the late 1990s. The WAZ Media Group is one of the most important (print) media companies in Europe and publishes the Ruhr area's two most important daily newspapers, Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (WAZ; 580,000 copies) and Neue Ruhr/Rhein Zeitung (NRZ; 180,000 copies). In Essen, the WAZ Group also publishes the local Borbecker Nachrichten (at times Germany's largest local newspaper)[citation needed] and Werdener Nachrichten, both of which had been independent weekly newspapers for parts of Essen. Additionally, Axel Springer run a printing facility for their boulevard-style daily paper Bild in Essen.

Education

One renowned educational institution in Essen is the Folkwang University, a university of the arts founded in 1927, which is headquartered in Essen and has additional facilities in Duisburg, Bochum and Dortmund.

The University of Duisburg-Essen, which resulted from a 2003 merger of the universities of Essen and Duisburg, is one of Germany's "youngest" universities with about 42.000 Students.[39] One of its primary research areas is urban systems (i.e., sustainable development, logistics and transportation), a theme largely inspired by the highly urbanised Ruhr area. Other fields include nanotechnology, discrete mathematics and "education in the 21st century". Another university in Essen is the private Fachhochschule für Ökonomie und Management, a university of applied sciences with over 6,000 students and branches in 15 other major cities throughout Germany.

Medicine

Essen offers a highly diversified health care system with more than 1,350 resident doctors and almost 6,000 beds in 13 hospitals, including a university hospital. The university hospital dates back to 1909, when the city council established a municipal hospital; although it was largely destroyed during World War II, it was later rebuilt, and finally gained the title of a university hospital in 1963. It focuses on diseases of the circulatory system (West German Heart Centre Essen), oncology and transplantation medicine, with the department of bone marrow transplantation being the second-largest of its kind in the world.

Transport

Streets and motorways

The road network of Essen consists of over 3,200 streets, which in total have a length of roughly 1,600 km (994 mi).

Three Autobahnen touch Essen territory, most importantly the Ruhrschnellweg (Ruhr expressway, A 40), which runs directly through the city, dividing it roughly in half. In a west-eastern direction, the A 40 connects the Dutch city of Venlo with Dortmund, running through the whole Ruhr area. It is one of the arterial roads of the Ruhr area (> 140,000 vehicles/day) and suffers from heavy congestion during rush hours, which is why many people in the area nicknamed it Ruhrschleichweg (Ruhr crawling way). A tunnel was built in the 1970s, when the then-Bundesstraße was upgraded to motorway standards, so that the A 40 is hidden from public view in the inner-city district near the main railway station.

In the north, the A 42 briefly touches Essen territory, serving as an interconnection between the neighboring cities of Oberhausen and Gelsenkirchen and destinations beyond.

A segment of the A 52 connects Essen with the more southern region around Düsseldorf. On Essen territory, the A 52 runs from the southern boroughs near Mülheim an der Ruhr past the fairground and then merges with the Ruhrschnellweg at the Autobahndreieck Essen-Ost junction east of the city centre.

With the A 40/A 52 in the southern parts of the city and the A 42 in the north, there is a gap in the motorway system often leading to congestion on streets leading from the central to the northern boroughs. An extension of the A 52 to connect the Essen-Ost junction with the A 42 to close this gap is considered urgent;[40] it has been planned for years but not yet been realized – most importantly due to the high-density areas this extension would lead through, resulting in high costs and concerns with the citizens.

Public transport

As with most communes in the Ruhr area, local transport is carried out by a local, publicly owned company for transport within the city, the DB Regio subsidiary of Deutsche Bahn for regional transport and Deutsche Bahn itself for long-distance journeys. The local carrier, Essener Verkehrs-AG (EVAG), is a member of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr (VRR) association of public transport companies in the Ruhr area, which provides a uniform fare structure in the whole region. Within the VRR region, tickets are valid on lines of all members as well as DB's railway lines (except the high-speed InterCity and Intercity-Express networks) and can be bought at ticket machines and service centres of EVAG, all other members of VRR, and DB.

As of 2009[update], EVAG operates 3 U-Stadtbahn lines of the Essen Stadtbahn network, 7 Straßenbahn (tram) lines and 57 bus lines (16 of these serving as Nacht Express late-night lines only). The Stadtbahn and Straßenbahn operate on total route lengths of 19.6 kilometres (12.2 mi) and 52.4 kilometres (32.6 mi), respectively.[41] One tram line and a few bus lines coming from neighboring cities are operated by these cities' respective carriers. The U-Stadtbahn, which partly runs on used Docklands Light Railway stock, is a mixture of tram and full underground systems with 20 underground stations for the U-Stadtbahn and additional 4 underground stations used by the tram. Two lines of the U-Stadtbahn are completely intersection-free and hence independent from other traffic, and the U18 line leading from Mülheim main station to the Bismarckplatz station at the gates of the city centre partly runs above ground amidst the A 40 motorway. The Essen Stadtbahn is one of the Stadtbahn systems integrated into the greater Rhine-Ruhr Stadtbahn network.

On the same motorway, a long-term test of a guided bus system is being held since 1980. Many EVAG rail lines meet at the main station but only a handful of bus lines. However, all but one of the Nacht Express bus lines originate from / lead to Essen Hauptbahnhof in a star-shaped manner. All EVAG lines, including the Nacht Express lines, are closed on weekdays from 1:30 a.m. to 4:30 a.m.

Of the Rhein-Ruhr S-Bahn net's 13 lines, 5 lines lead through Essen territory and meet at the Essen Hauptbahnhof main station, which also serves as the connection to the Regional-Express and Intercity-Express network of regional and nationwide high-speed trains, respectively. Following Essen's appointment as European Capital of Culture 2010, the main station, which is classified as a station of highest importance and which had not been substantially renovated over decades, will be redeveloped with a budget of €57 million until early 2010.[42] Other important stations in Essen, where regional and local traffic are connected, are the Regionalbahnhöfe (regional railway stations) in the boroughs of Altenessen, Borbeck, Kray and Steele. Further 20 S-Bahn stations can be found in the whole urban area.

Aviation

Together with the neighbouring city of Mülheim an der Ruhr and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Essen maintains Essen/Mülheim Airport (IATA: ESS, ICAO: EDLE). While the first flights had already arrived in 1919, it was officially opened on 25 August 1925. Significantly expanded in 1935, Essen/Mülheim became the central airport of the Ruhr area until the end of the Second World War, providing an asphalted runway of 1,553 m (5,095 ft), another unsurfaced runway for gliding and destinations to most major European cities. It was heavily damaged during the war, yet partly reconstructed and used by the Allies as a secondary airport since visibility is less often obscured than at Düsseldorf Airport. The latter then developed into the large civil airport that it is now, while Essen/Mülheim now mainly serves occasional air traffic (some 33,000 passengers each year),[43] the base of a fleet of airships and Germany's oldest public flight training company. Residents of the region around Essen typically use Düsseldorf Airport (~ 20 driving minutes) and occasionally Dortmund Airport (~ 30 driving minutes) for both domestic and international flights.

Landmarks

Zollverein Industrial Complex

The Zollverein Industrial Complex is the city's most famous landmark. For decades, the coal mine (current form mainly from 1932, closed in 1986) and the coking plant (closed in 1993) ranked among the largest of their kinds in Europe. Shaft XII, built in Bauhaus style, with its characteristic winding tower, which over the years has become a symbol for the whole Ruhr area, is considered an architectural and technical masterpiece, earning it a reputation as the "most beautiful coal mine in the world".[44] After UNESCO had declared it a World Heritage Site in 2001, the complex, which had lain idle for a long time and was even threatened to be demolished, began to see a period of redevelopment. Under the direction of an agency borne by the land of North Rhine-Westphalia and the city itself, several arts and design institutions settled mainly on the grounds of the former coal mine; a redevelopment plan for the coking plant is to be realised.

On the grounds of the coal mine and the coking plant, which are both accessible free of charge while paid guided tours (some with former Kumpels) are also available, several tourist attractions can be found, most importantly the Design Zentrum NRW/Red Dot Design Museum. The Ruhrmuseum, a museum dedicated to the history of the Ruhr area, which had been existing since 1904, opened its gates as one of the anchor attractions in the former coal-washing facility in 2010.

Essen Minster and treasury

The former collegiate church of Essen Abbey and nowadays cathedral of the Bishop of Essen is a Gothic hall church made from light sandstone. The first church on the premises dates back to between 845 and 870; the current church was constructed after a former church had burnt down in 1275. However, the important westwork and crypt have survived from Ottonian times. The cathedral is located in the centre of the city which evolved around it. It is not spectacular in appearance and the adjacent church St. Johann Baptist, which is located directly within the pedestrian precinct, is often mistakenly referred to as the cathedral. The cathedral treasury, however, ranks amongst the most important in Germany since only few art works have been lost over the centuries. The most precious exhibit, located within the cathedral, is the Golden Madonna of Essen (around 980), the oldest known sculpture of the Madonna and the oldest free-standing sculpture north of the Alps. Other exhibits include the alleged child crown of Emperor Otto III, the eldest preserved seven-branched Christian candelabrum and several other art works from Ottonian times.

Old Synagogue

Opened in 1913, the then-New Synagogue served as the central meeting place of Essen's pre-war Jewish community. The building ranks as one of the largest and most impressive testimonies of Jewish culture in pre-war Germany. In post-war Germany, the former house of worship was bought by the city, used as an exhibition hall and later rededicated as a cultural meeting centre and house of Jewish culture.

Villa Hügel

Built in 1873 by industrial magnate Alfred Krupp, the 269-room mansion (8,100 m2 or 87,190 sq ft) and the surrounding park of 28 ha (69.2 acres) served as the Krupp family's representative seat. The city's land register solely lists the property, which at times had a staff of up to 640 people, as a single-family home.[45] At the time of its construction, the villa featured some technical novelties and peculiarities, such as a central hot air heating system, own water- and gas works and electric internal and external telegraph- and telephone systems (with a central induction alarm for the staff). The mansion's central clock became the reference clock for the whole Krupp enterprise; every clock was to be set with a maximum difference of half a minute. It even acquired its own railway station, Essen Hügel, which is still a regular stop. The Krupp family had to leave the Gründerzeit mansion in 1945, when it was annexed by the allies. Given back in 1952, Villa Hügel is now seat of the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation (major shareholder of Thyssen-Krupp) and was opened for concerts and sporadic yet high-profile exhibitions.

Kettwig and Werden

In the south of the city, the boroughs of Kettwig and Werden exceptionally stand for towns once of their own, which have been annexed in 1929 (Werden) and 1975 (Kettwig), respectively, and which have largely preserved their pre-annexation character. While most of the northern boroughs were heavily damaged during the Second World War and often lost their historic town centres; the more southern parts got off more lightly.

In Werden, St. Ludger founded Werden Abbey around 799, 45 years before St. Altfrid founded the later cornerstone of the modern city, Essen Abbey. The old church of Werden abbey, St. Ludgerus, was designated a papal basilica minor in 1993, while the main building of the former abbey today is the headquarters of the Folkwang University of music and performing arts.

Kettwig, which was annexed in 1975, much to the dismay of the population that still struggles for independence,[46] was mainly shaped by the textile industry. The most southern borough of Essen is also the city's largest (with regard to area) and presumably greenest.

Other important cultural sites

- Museum Folkwang: One of the Ruhr area's major art collections, mainly from the 19th and 20th centuries. Major parts of the museum have recently been rebuilt and expanded according to plans by David Chipperfield & Co. The Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation is the sole funder of the €55 million project which was completed in early 2010. After its re-opening, it also hosts the collection of the Deutsches Plakat Museum (more than 340 000 exhibits).

- Aalto Theatre: Opened in 1988 (the plans dating back to 1959), the asymmetric building with its deep indigo interior is home to the acclaimed Essen Opera and Ballet.

- Saalbau: Home of the Essen Philharmonic Orchestra, completely renovated in 2003/2004. Critics have repeatedly voted the Essen Philharmonic as Germany's Orchestra of the Year.[47]

- Colosseum Theater: Situated in a former Krupp factory building at the fringe of the central pedestrian precinct, the Colosseum Theater has been home to several musical theatre productions since 1996.

- Zeche Carl, a former coal mine, now a cultural centre and venue for Rock concerts and home of Offener Kanal Essen.

Other sites

- Gartenstadt Margarethenhöhe: Founded by Margarethe Krupp in 1906, the garden city with its 3092 units in 935 buildings on an area of 115 ha (284.2 acres) (of which 50 ha are woodland) is considered the first of its kind in Germany. All buildings follow the same stylistic concept, with slight variations for each one. Although originally designed as an area for the lower classes with quite small flats, the old part Margarethenhöhe I has developed into a middle class residential area and housing space has become highly sought after. A new part, Margarehenhöhe II, was built in the 1960s and 1970s but is architecturally inferior and especially the multi-storey buildings are still considered social hot spots.

- Moltkeviertel (Moltke Quarter): from 1908 on, following reformative plans of the city deputy Robert Schmidt, this quarter was developed just south-east of the city centre. Large green zones, forming broad urban ventilation lanes and incorporating sporting and playing areas and high quality architecture – invariably in the style of Reform Architecture, combine to create a unique example worldwide of modern town planning. It reflects reformative ideas and dates from the early part of the 20th century. The Moltkeviertel continues to be a much sought-after area for residential, educational, health care and small-scale commercial purposes. On the Moltkeplatz, the quarter's largest square, an ensemble of high quality contemporary art is maintained and cared for by local residents.

- Grugapark: With a total area of 70 ha (173.0 acres), the park near the exhibition halls is one of the largest urban parks in Germany and, although entry is not free of charge, one of the most popular recreational sites of the city. It includes the city's botanical garden, the Botanischer Garten Grugapark.

- Lake Baldeney: The largest of the six reservoirs of the River Ruhr, situated in the south of the city, is another popular recreational area. It is used for sailing, rowing and ship tours. The hilly and only lightly developed forest area around the lake, from which the Kettwig area is easily reachable, is also popular with hikers.

Notable people

- For a comprehensive list of people who were born or acted/lived in Essen, see this article in the German Wikipedia.

Honorary citizens

The city of Essen has been awarding honorary citizenships since 1879 but has (coincidentally) discontinued this tradition after the foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949. A notable exception was made in 2007, when Berthold Beitz, the president of the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation received honorary citizenship for his long lasting commitment to the city.[48] The following list contains all honorary citizens of the city of Essen:[49]

- 1879 Otto von Bismarck – Chancellor of Germany

- 1888 Friedrich Hammacher – Politician, lawyer and economist

- 1895 Johann Heinrich Peter Beising – Roman catholic theologian

- 1896 Friedrich Alfred Krupp – Industrialist (spouse of Margarethe Krupp, see below)

- 1901 Heinrich Carl Sölling – Tradesman and benefactor

- 1906 Erich Zweigert – Lord Mayor from 1886 till 1906

- 1912 Margarethe Krupp – benefactress (spouse of Friedrich Alfred Krupp, see above)

- 1917 Paul von Hindenburg – Generalfeldmarschall and army leader, later President of Germany

- 1948 Viktor Niemeyer – Councilman (posthumous recognition)

- 2007 Berthold Beitz – president of the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation

Today, the highest award of the city is the Ring of Honour, which Berthold Beitz, for example, had already received in 1983. Other bearers of the Ring of Honour include Essen's former Lord Mayor and later President of Germany, Gustav Heinemann, as well as Franz Cardinal Hengsbach, the first Bishop of Essen.

Sport

The biggest association football clubs in Essen are Rot-Weiss Essen (Red-White Essen) and Schwarz-Weiß Essen (Black-White Essen). Rot-Weiss Essen is playing in the fourth tier of the German football league system, Regionalliga West, and Schwarz-Weiß Essen in the fifth tier, Oberliga Nordrhein-Westfalen. Other football clubs are BV Altenessen, TuS Helene Altenessen, SG Essen-Schönebeck.

The city's main basketball team is ETB Essen, currently called the ETB Wohnbau Baskets for sponsorship reasons. The team is one of the main teams in Germany's second division ProA and has attempted to move up to Germany's elite league Basketball Bundesliga. The Baskets play their home games at the Sportpark am Hallo.

Footnotes

- ^ "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden Nordrhein-Westfalens am 31. Dezember 2023 – Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes auf Basis des Zensus vom 9. Mai 2011" (in German). Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW. Retrieved 2024-06-20.

- ^ [1] in the Regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf

- ^ https://www.eon.com/en/media/news/press-releases/2015/4/27/eon-moves-forward-with-transformation-key-organizational-and-personnel-decisions-made.html

- ^ http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/studie-zur-verschuldung-vielen-deutschen-staedten-droht-die-pleite-a-938203.html

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/applying-for-the-award/2017-egca-applicant-cities/

- ^ http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-125300649.html

- ^ http://www.handelsblatt.com/panorama/reise-leben/top-ten-das-sind-deutschlands-gruenste-staedte/4369498.html

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/media-corner/press-releases/index.html

- ^ http://www.sueddeutsche.de/leben/ranking-die-gesuendeste-stadt-deutschlands-1.240517

- ^ Extreme temperature records – Worldwide

- ^ "Weather Information for Essen".

- ^ "Climatological Information for Essen, Germany" – Hong Kong Observatory

- ^ Stadt Essen. "Origin of place names" (in German). Essen.de. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Paul Derks: Der Ortsname Essen, in: Essener Beiträge 103 (1989/90), pp. 27–51

- ^ "Ergrabene Zeiten", City of Essen, undated Template:De icon

- ^ Detlef Hopp: Essen vor der Geschichte – Die Archäologie der Stadt bis zum 9. Jahrhundert, in Borsdorf (Ed.): Essen – Geschichte einer Stadt, 2002, p. 32

- ^ "Mapping Ancient Germania: Berlin Researchers Crack the Ptolemy Code", Der Spiegel

- ^ "NRW 2000 – Epoche des Nationalsozialismus – Einleitung – Hitler und Mussolini besuchen die "Waffenschmiede des Reiches" und die Krupp-Werke Essen". Nrw2000.de. 25 September 1937. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Auszug aus der Zusammenstellung der Monatsberichte der stellv. Generalkommandos an das preußische Kriegsministerium betr. die allgemeine Stimmung im Volke" (Excerpt from the compilation of monthly reports of the Deputy Commanding Generals to the Prussian War Ministry concerning the morale of the population). 3 March 1917, no. 230/17 g. B. 6., Generallandesarchiv Karlsruhe, Abt. 456, vol. 70. Reprinted in Wilhelm Deist, Militär und Innenpolitik im Weltkrieg 1914–1918 (Military and Domestic Policy in the World War, 1914–1918). 2 volumes. Düsseldorf: Droste, 1970, vol. 2, pp. 666–67.

- ^ Her mit der Kohle – Der Spiegel EinesTages; retrieved on 4. May, 2012.

- ^ Historischer Verein der Stadt Essen/Stadtarchiv.

- ^ "Geschichte des Hauses" (in German). Retrieved 2014-10-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ "Ausstellung erinnert an Zwangsarbeiter" (in German). Retrieved 2014-10-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ "Der LVR in Europa" (in German). Retrieved 2014-10-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1945/1945%20-%201571.html

- ^ Essen, Germany – Transatlantic Cities Network, German Marshall Fund of the United States accessed 3 April 2010

- ^ Essen – History, eurotravelling.net, accessed 3 April 2010

- ^ The Essen Lynching Case, University of the West of England, accessed 3 April 2010

- ^ Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939–1946 (Revised Edition, 2006), Stackpole Books, p. 97.

- ^ Handbuch Essener Statistik Bevölkerung 1987–2014 (PDF). Stadt Essen. p. 99. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- ^ History of Essen (in German)

- ^ http://www.derwesten.de/staedte/essen/stadtinfo/wahlen/

- ^ "Origin of the sword in the Essen Cathedral Treasury". Regesta-imperii.adwmainz.de. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Politikfeld Bürgerbegegnungen und Städtepartnerschaften: Städtepartnerschaften". Essen.de (official website) (in German). Presse- und Kommunikationsamt, Oberbürgermeister, Stadt Essen. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ^ Jérôme Steffenino, Marguerite Masson. "Ville de Grenoble – Coopérations et villes jumelles". Grenoble.fr. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ Jérôme Steffenino, Marguerite Masson. "Ville de Grenoble –Coopérations et villes jumelles". Grenoble.fr. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Harvath, Les (18 March 2007). "School colors glimpse history". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ http://www.eon.com/en/media/news/press-releases/2015/4/27/eon-moves-forward-with-transformation-key-organizational-and-personnel-decisions-made.html

- ^ http://www.radioessen.de/essen/lokalnachrichten/lokalnachrichten/archive/2016/01/08/article/-84812ba8fa.html

- ^ Bundesverkehrswegeplan 2003, p. 124

- ^ "Kleine EVAG Statistik 2010* (*stand 31.12.2009)" (PDF) (in German). Essener Verkehrs-Aktiengesellschaft (EVAG). December 31, 2009. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs Archived September 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ According to RVV-Verkehrsstatistik 2007 (RVV Traffic Statistics 2007).

- ^ "European Route of Industrial Heritage". En.erih.net. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Official Villa Hügel Web Page Archived September 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Official Site of the State Parliament of North Rhine-Westphaila". Landtag.nrw.de. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Pressetext – Oper". Opernwelt. 28 September 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Speech by Mayor Wolfgang Reiniger (German)" (PDF). Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Stadt Essen. "Honorary Citizens of Essen". Essen.de. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

External links

- Official city website

- Essen, 2010 European Capital of Culture Guide

- Essen City Panoramas – Panoramic Views and virtual Tours

- Pictures from Kettwig

- World Cities Images. Germany. Essen

- Memorials in Essen at sites-of-memory.de

- ConRuhr – Academic Liaison Office for Universities of Duisburg-Essen, Dortmund, Bochum

- List of Hotels in Essen (English)