List of Iranian artifacts abroad

|

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

List of Iranian artifacts abroad is a list of Iranian and Persian antiquities outside Iran, especially in museums.[1][2][3] Most of these were found outside modern Iran, in parts of the former Persian Empire, or places influenced by it.

Neighbors of Iran during the Achaemenid period

[edit]Afghanistan

[edit]- Tillya Tepe often known as the Bactrian gold is a collection of about 20,600 ornaments, coins and other kinds of artifacts, made of gold, silver, ivory etc., that were found in six burial mounds (five women and one man) with extremely rich jewelry, dated to around the 1st century BCE-1st century CE.[4] The ornaments include necklaces set with semi-precious stones, belts, medallions and a crown. After its discovery, the hoard went missing during the wars in Afghanistan, until it was "rediscovered" and first brought to public attention again in 2003. The heavily fortified town of Yemshi Tepe, just five kilometres to the northeast of modern Sheberghan on the road to Akcha, is only half a kilometre from the now-famous necropolis of Tillia-tepe.[1]

- Buddhas of Bamiyan For half a century, through war, anarchy and upheaval, Afghanistan has been stripped of tens of thousands of Buddhist and Hindu antiquities, 33 of those antiquities, were handed over to the Afghan ambassador,at a ceremony in New York.

The artifacts were part of a hoard of 2,500 objects seized in a dozen raids between 2012 and 2014 from Subhash Kapoor, a disgraced Manhattan art dealer currently jailed in India on smuggling and theft charges.[2]

Gallery

[edit]-

Statuette of winged figurine

-

Cloth decorations.

-

Bracelets.

-

Decorative stars. Tomb I.

-

Amorini riding on fish, Tillia tepe. Tomb II.

-

Rings from Tillia tepe; the left one represents a seated Athena. Tomb II.

-

Necklace. Tomb II.

-

"Kings with dragons". Tomb II.

-

Men in armor, in Greek fighting gear. Tomb III.

-

"Akinakes" polylobed decorated daggers. Tomb IV.

Anatolia (Turkey)

[edit]

Xerxes I inscription at Van[5] is a trilingual cuneiform inscription of the Achaemenid King Xerxes I (r. 486–465 BC).[6][7] is located on the southern slope of a mountain adjacent to the Van Fortress, near Lake Van in present-day Turkey.[7] When inscribed it was located in the Achaemenid province of Armenia.[6] The inscription is inscribed on a smoothed section of the rock face near the fortress, approximately 20 metres (70 feet) above the ground. The niche was originally carved out by Xerxes' father, King Darius (r. 522–486 BC), but he left the surface blank.[8][7]

- A Persian city unearthed During the Oluz Höyük excavations in Amasya, column bases of a 2 thousand 500-year-old palace from the Persian period were unearthed. which reflects the Persian cultural character in terms of architecture, pottery and small finds, is divided into two main phases A and B. The head of the excavation, Professor of Archeology at Istanbul University, stated that they deepened the work after finding the remains of the city's road, mansion and fire temple. Dr. Şevket Dönmez said, “For the first time this year, a colonnaded reception hall called 'Apadana', a throne hall, and an executive hall began to come to light. We are just at the beginning of the excavations. But even the current findings are very exciting, ”he said.Emphasizing that the finds are very important in terms of Anatolian Iron Age history, Anatolian Ancient history and Persian archeology, Prof. Dr. Dönmez said, “Very important findings that identify and make it unique. Currently 6 column We have revealed the pedestal. Prof. Dr. Dönmez said, "Before we started the excavation, we did not know what such a Persian city we would find. Neither such a temple, nor such a reception hall. We did not guess anything. We would just dig an ordinary Central Anatolian mound and solve the problems of Iron Age culture by ourselves. Believe it now, the whole world has begun to follow Oluz Höyük. I think that after Göbeklitepe, Anatolia started to become a very important center that changed the history of religion in Anatolia. [3]

Tbilisi

[edit]Atashgah’. It means ‘place of fire’ and its use is usually associated with Zoroastrian fire temples. The history of the Atashgah in the capital city of Tbilisi goes back to the 5th or 6th century, when Persia was ruled by the Sasanian dynasty, of which Georgia was a part. [4] Also Treasure of Persian Manuscripts at Dagestan Scientific Centre.

Europe and the United States

[edit]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art displays ancient Persian artifacts. Among the oldest items on display are dozens of clay bowls, jugs and engraved coins dating back 3,500 years and formerly housed in the University of Chicago's famed Oriental Institute.[9]

- United Kingdom – Museums in UK have many Persian artifacts among them British Museum

The Cyrus Cylinder is an ancient clay cylinder, now broken into several pieces, on which is written a declaration in Akkadian cuneiform script in the name of Persia's Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great.[10][8] It dates from the 6th century BC and was discovered in the ruins of Babylon in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) in 1879.[10] It was created and used as a foundation deposit following the Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 BC, when the Neo-Babylonian Empire was invaded by Cyrus and incorporated into his own empire. It is currently in the possession of the British Museum, which sponsored the expedition that discovered the cylinder.

- France :The Louvre's department of Near Eastern antiquities was established in 1881 and presents an overview of early Near Eastern civilization and "first settlements", before the arrival of Islam. The department is divided into three geographic areas: the Levant, Mesopotamia (Iraq), and Persia (Iran). The collection's development corresponds to archaeological work such as Paul-Émile Botta's 1843 expedition to Khorsabad and the discovery of Sargon II's palace.[11][12] These finds formed the basis of the Assyrian museum, the precursor to today's department.[11]

The museum contains exhibits from Sumer and the city of Akkad, with monuments such as the Prince of Lagash's Stele of the Vultures from 2450 BC and the stele erected by Naram-Sin, King of Akkad, to celebrate a victory over barbarians in the Zagros Mountains. The 2.25-metre (7.38 ft) Code of Hammurabi, discovered in 1901, displays Babylonian Laws prominently, so that no man could plead their ignorance. The 18th-century BC mural of the Investiture of Zimrilim and the 25th-century BC Statue of Ebih-Il found in the ancient city-state of Mari are also on display at the museum.[citation needed] The Persian portion of Louvre contains work from the archaic period, like the Funerary Head and the Persian Archers of Darius I.[11][13] The section also contains rare objects from Persepolis which were lent to the British Museum for its Ancient Persia exhibition in 2005.[3]

Oxus treasure

[edit]

The Oxus treasure (Persian: گنجینه آمودریا) is a collection of about 180 surviving pieces of metalwork in gold and silver, the majority rather small, plus perhaps about 200 coins, all from the Achaemenid Persian period. The collection was found by the Oxus River sometime between 1877 and 1880.[14] The exact place of the find remains unclear but is often proposed as being near Kobadiyan, Tajikistan.[15] It is likely that many other pieces from the hoard were melted down for bullion; early reports suggest there were originally some 1500 coins and mention types of metalwork that are not among the surviving pieces. The metalwork is believed to date from the sixth to fourth centuries BC, but the coins show a greater range, with some of those believed to belong to the treasure coming from around 200 BC.[16] The most likely origin for the treasure is that it belonged to a temple, where votive offerings were deposited over a long period. How it came to be deposited is unknown.[17]

The British Museum now has nearly all the surviving metalwork, with one of the pair of griffin-headed bracelets on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum, and displays them in Room 52. The group arrived at the museum by different routes, with many items bequeathed to the nation by Augustus Wollaston Franks. The coins are more widely dispersed, and more difficult to firmly connect with the treasure. A group believed to come from it is in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, and other collections have examples.[18]

Japan

[edit]The Miho Museum houses Mihoko Koyama's private collection of Asian Achaemenid, Sassanid and Western antiques bought on the world market by the Shumei organization in the years before the museum was opened in 1997. There are over two thousand pieces in the permanent collection, of which approximately 250 are displayed at any one time.[19] Among the objects in the collection are more than 1,200 objects that appear to have been produced in Achaemenid Central Asia.[20] Some scholars have claimed these objects are part of the Oxus Treasure, lost shortly after its discovery in 1877 and rediscovered in Afghanistan in 1993.[21] The presence of a unique findspot for both the Miho acquisitions and the British Museum's material, however, has been challenged.[22]

The Tokyo National Museum preserves a variety of Iranian antiquities and works of art, including pottery, paintings, calligraphy, metalwork, sculpture, inlaid pottery and textiles.[5] [6].

Gallery

[edit]-

Proto-Elamite cylinder seal (Louvre Museum)

-

Orant figure of Susa IV (Louvre Museum)

-

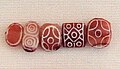

Carnelian beads (Louvre Museum)

-

Weight in veined jasper (Louvre Museum)

-

Iranian male royal figure (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Persian objects (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Artifacts of Tall-i Bakun in University of Chicago Oriental Institute

See also

[edit]- Antiochus cylinder

- Babylonian Chronicles

- Babylonian Map of the World

- Cylinders of Nabonidus

- Cyrus Cylinder

- Gilgamesh flood myth

- Greater Iran

- Jar of Xerxes I

- Kurkh Monoliths

- Lachish reliefs

- Lakh Mazar

- Library of Ashurbanipal

- Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal

- Persian Inscriptions on Indian Monuments

- Rassam cylinder

- Sennacherib's Annals

- Tall-i Bakun

- Xerxes I inscription at Van

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Persian antiquities found in almost all museums worldwide". Tehran times. 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ "Iranian artifacts Abroad". parssea.org. 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia". University of California Press. 2006. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ Srinivasan, Doris (2007). On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World. BRILL. p. 16. ISBN 9789004154513.

- ^ Dusinberre 2013, p. xxi.

- ^ a b Dusinberre 2013, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Khatchadourian 2016, p. 151.

- ^ a b Kuhrt (2007), pp. 70, 72, 301

- ^ Persian art in the collection of the Museum of Oriental Art, WorldCat

- ^ a b Dandamayev, (2010-01-26)

- ^ Mignot, pp. 119–21

- ^ "Decorative Arts". Musée du Louvre. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ Curtis, 5

- ^ "East of Termez, on the Kafirnigan River, on the territory of Tajikistan, lies the small town of Kobadiyan, near which was found in the late 1870s one of the most famous treasures of all time, the so-called treasure of Oxus." in Knobloch, Edgar (2001). Monuments of Central Asia: A Guide to the Archaeology, Art and Architecture of Turkestan. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-86064-590-7.

- ^ Curtis, 48, 57-58

- ^ Curtis, 58-61

- ^ Curtis, 48

- ^ Reif, Rita (16 August 1998). "ARTS/ARTIFACTS; A Japanese Vision of the Ancient World". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ^ Curtis, John (1 September 2004). "The Oxus Treasure in the British Museum". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 10 (3): 334. doi:10.1163/1570057042596397.

- ^ Southampton, Kathy Judelson; Pichikyan, I.R. (1 January 1998). "Rebirth of the Oxus Treasure: Second Part of the Oxus Treasure From the Miho Museum Collection". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 4 (4): 306–383 [308–309]. doi:10.1163/157005797X00126.

- ^ Muscarella, Oscar White (1 November 2003). "Museum Constructions of the Oxus Treasures: Forgeries of Provenience and Ancient Culture". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 9 (3): 259–275. doi:10.1163/157005703770961778.

References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia by John Curtis (Editor), Nigel Tallis.

- Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE Paperback – Illustrated, January 20, 2014 by Matt Waters (Author).

- Boardman, Sir John, "The Oxus Scabbard", Iran, Vol. 44, (2006), pp. 115–119, British Institute of Persian Studies, JSTOR

- Collon, Dominique, "Oxus Treasure", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, accessed 4 July 2013, subscription required.

- Curtis, John, The Oxus Treasure, British Museum Objects in Focus series, 2012, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714150796

- Curtis, John, "The Oxus Treasure in the British Museum", Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia, Vol. 10 (2004), pp. 293–338

- "Curtis and Tallis", Curtis, John and Tallis, Nigel (eds), Forgotten Empire - The World of Ancient Persia (catalogue of British Museum exhibition), 2005, University of California Press/British Museum, ISBN 9780714111575, google books

- Dalton, O.M., The Treasure Of The Oxus With Other Objects From Ancient Persia And India, 1905 (nb, not the final 3rd edition of 1963), British Museum, online at archive.org, catalogs 177 objects, with a long introduction.

- Frankfort, Henri, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, Pelican History of Art, 4th ed 1970, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), ISBN 0140561072

- Mongiatti, Aude; Meeks, Nigel & Simpson, St John (2010). "A gold four-horse model chariot from the Oxus Treasure: a fine illustration of Achaemenid goldwork" (PDF). The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin. 4. British Museum: 27–38. ISBN 9781904982555.

- Muscarella, Oscar White, Archaeology, Artifacts and Antiquities of the Ancient Near East: Sites, Cultures, and Proveniences, 2013, BRILL, ISBN 9004236694, 9789004236691, google books

- Yamauchi, Edwin M., review of The Treasure of the Oxus with Other Examples of Early Oriental Metal-Work, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 90, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1970), pp. 340–343, JSTOR

- "Zeymal": "E. V. Zeymal (1932-1998)", obituary by John Curtis, Iran, Vol. 37, (1999), pp. v-vi, British Institute of Persian Studies, JSTOR

- Arberry, A.J. (1953). The Legacy of Persia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821905-7. OCLC 1283292.

- Arnold, Bill T.; Michalowski, Piotr (2006). "Achaemenid Period Historical Texts Concerning Mesopotamia". In Chavelas, Mark W. (ed.). The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation. London: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23581-1.

- Bedford, Peter Ross (2000). Temple Restoration in Early Achaemenid Judah. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11509-5.

- Beaulieu, P.-A. (Oct 1993). "An Episode in the Fall of Babylon to the Persians". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 52 (4): 241–261. doi:10.1086/373633. S2CID 162399298.

- Becking, Bob (2006). ""We All Returned as One!": Critical Notes on the Myth of the Mass Return". In Lipschitz, Oded; Oeming, Manfred (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Persian period. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-104-7.

- Bidmead, Julye (2004). The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity And Royal Legitimation In Mesopotamia. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-59333-158-0.

- Briant, Pierre (2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbraun. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

- Brown, Dale (1996). Persians: Masters of Empire. Alexandra, VA: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-9104-9.

- Buchanan, G. (1964). "The Foundation and Extension of the Persian Empire". In Bury, J.B.; Cook, S.A.; Adcock, F.E. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: IV. The Persian Empire and the West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 57550495.

- Curtis, John; Tallis, Nigel; André-Salvini, Béatrice (2005). Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24731-4.

- Dandamaev, M.A. (1989). A political history of the Achaemenid Empire. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09172-6.

- Daniel, Elton L. (2000). The History of Iran. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30731-7.

- Dick, Michael B. (2004). "The "History of David's Rise to Power" and the Neo-Babylonian Succession Apologies". In Batto, Bernard Frank; Roberts, Kathryn L.; McBee Roberts, Jimmy Jack (eds.). David and Zion: Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-092-7.

- Dusinberre, Elspeth R. M. (2013). Empire, Authority, and Autonomy in Achaemenid Anatolia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107577152.

- Dyck, Jonathan E. (1998). The Theocratic Ideology of the Chronicler. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11146-2.

- Fowler, Richard; Hekster, Olivier (2005). Imaginary kings: royal images in the ancient Near East, Greece and Rome. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-08765-0.

- Free, Joseph P.; Vos, Howard Frederic (1992). Vos, Howard Frederic (ed.). Archaeology and Bible history. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-47961-1.

- Fried, Lisbeth S. (2004). The priest and the great king: temple-palace relations in the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-090-3.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: Yehud, the Persian Province of Judah. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-08998-4.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2006). "The "Persian Documents" in the Book of Ezra: Are They Authentic?". In Lipschitz, Oded; Oeming, Manfred (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Persian period. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-104-7.

- Hallo, William (2002). Hallo, William; Younger, K. Lawson (eds.). The Context of Scripture: Monumental inscriptions from the biblical world. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10619-2.

- Haubold, Johannes (2007). "Xerxes' Homer". In Bridges, Emma; Hall, Edith; Rhodes, P.J. (eds.). Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars: Antiquity to the Third Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927967-8.

- Hilprecht, Hermann Volrath (1903). Explorations in Bible lands during the 19th century. Philadelphia: A.J. Molman and Company.

- Janzen, David (2002). Witch-hunts, purity and social boundaries: the expulsion of the foreign women in Ezra 9–10. London: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84127-292-4.

- Khatchadourian, Lori (2016). Imperial Matter: Ancient Persia and the Archaeology of Empires. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520964952.

- Koldewey, Robert; Griffith Johns, Agnes Sophia (1914). The excavations at Babylon. London: MacMillan & co.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1982). "Babylonia from Cyrus to Xerxes". In Boardman, John (ed.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Vol IV – Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1983). "The Cyrus Cylinder and Achaemenid imperial policy". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 25. ISSN 1476-6728.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (2007). The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources of the Achaemenid Period. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-43628-1.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (2007b). "Cyrus the Great of Persia: Images and Realities". In Heinz, Marlies; Feldman, Marian H. (eds.). Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-135-1.

- Lincoln, Bruce (2007). Religion, empire and torture: the case of Achaemenian Persia, with a postscript on Abu Ghraib. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-48196-8.

- Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2009). "The First Persian Empire 550–330BC". In Harrison, Thomas (ed.). The Great Empires of the Ancient World. Getty Publications. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-89236-987-4.

- Mallowan, Max (1968). "Cyrus the Great (558-529 B.C.)". In Frye, Richard Nelson; Fisher, William Bayne (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2, The Median and Achaemenian periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2. OCLC 40820893.

- Mitchell, T.C. (1988). Biblical Archaeology: Documents from the British Museum. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36867-4.

- Pahlavi, Mohammed Reza (1967). The White Revolution of Iran. Imperial Pahlavi Library.

- Pritchard, James Bennett, ed. (1973). The Ancient Near East, Volume I: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press. OCLC 150577756.

- Shabani, Reza (2005). Iranian History at a Glance. Mahmood Farrokhpey (trans.). London: Alhoda UK. ISBN 978-964-439-005-0.

- van der Spek, R.J. (1982). "Did Cyrus the Great introduce a new policy towards subdued nations? Cyrus in Assyrian perspective". Persica. 10. OCLC 499757419.

- Walker, C.B.F. (1972). "A recently identified fragment of the Cyrus Cylinder". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 10 (10): 158–159. doi:10.2307/4300475. ISSN 0578-6967. JSTOR 4300475.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2001). Ancient Persia: From 550 BC to 650 AD. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-675-1.

- Weissbach, Franz Heinrich (1911). Die Keilinschriften der Achämeniden. Vorderasiatische Bibliotek (in German). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

- Winn Leith, Mary Joan (1998). "Israel among the Nations: The Persian Period". In Coogan, Michael David (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2007). "Cyrus the Great and early Achaemenids". Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-108-3.

- Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). "Philosophical Visions: Human Nature, Natural Law, and Natural Rights". The Evolution of International Human Rights: Visions Seen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1.

- 19th-century archaeological discoveries

- Ancient art

- Archaeological artifacts

- Archaeological sites in Afghanistan

- Archaeology of the Achaemenid Empire

- Archaeology-related lists

- Archaeology in Asia

- Asian art museums

- Art Nouveau collections

- Bactria

- Cyrus the Great

- Iran history-related lists

- Iranian archaeological sites

- Jewellery

- Lists of works of art

- Middle Eastern objects in the British Museum

- Old Persian language

- Persian art

- Saka

- Sculpture of the Ancient Near East

- Treasure troves of Asia