Duke University

| |

| Latin: Universitas Dukiana[1] | |

Former names | Brown School (1838–1841) Union Institute (1841–1851) Normal College (1851–1859) Trinity College (1859–1924) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Eruditio et Religio (Latin)[1] |

Motto in English | "Knowledge and Faith"[2] |

| Type | Private research university |

| Established | 1838 |

| Accreditation | SACS |

Religious affiliation | Nonsectarian; historically affiliated with the United Methodist Church[3] |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $12.7 billion (2021)[4] (The university is also the primary beneficiary (32%) of the independent $3.69 billion Duke Endowment)[5] |

| Budget | $7.7 billion (FY 2022)[6] |

| President | Vincent Price[7] |

| Provost | Alec Gallimore |

Academic staff | 3,982 (fall 2021)[6] |

Administrative staff |

|

| Students | 16,780 (fall 2021)[6] |

| Undergraduates | 6,640 (fall 2022) [6] |

| Postgraduates | 9,991 (fall 2021)[6] |

| Location | , , United States 36°00′05″N 78°56′18″W / 36.00139°N 78.93833°W |

| Campus | Large city[8], 8,693 acres (35.18 km2)[6] |

| Other campuses | |

| Newspaper | The Chronicle |

| Colors | Duke blue and white[9] |

| Nickname | Blue Devils |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I FBS – ACC |

| Mascot | Blue Devil |

| Website | duke |

| |

Duke University is a private research university in Durham, North Carolina, United States. Founded by Methodists and Quakers in the present-day city of Trinity in 1838, the school moved to Durham in 1892.[10] In 1924, tobacco and electric power industrialist James Buchanan Duke established the Duke Endowment and the institution changed its name to honor his deceased father, Washington Duke.[11]

The campus spans over 8,600 acres (3,500 hectares) on three contiguous sub-campuses in Durham, and a marine lab in Beaufort.[12] The West Campus—designed largely by architect Julian Abele—incorporates Gothic architecture with the 210-foot (64-meter) Duke Chapel at the campus' center and highest point of elevation, is adjacent to the Medical Center. East Campus, 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) away, home to all first-years, contains Georgian-style architecture.

The university administers two concurrent schools in Asia, Duke–NUS Medical School in Singapore (established in 2005) and Duke Kunshan University in Kunshan, China (established in 2013).[13]

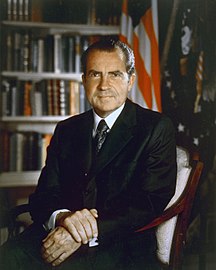

Duke spends more than $1 billion per year on research.[14] As of 2024[update], 16 Nobel laureates and 3 Turing Award winners have been affiliated with the university. Duke alumni also include 50 Rhodes Scholars. Duke is the alma mater of one president of the United States (Richard Nixon) and 14 living billionaires.[15]

History

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]

Duke first opened in 1838 as Brown's Schoolhouse, a private subscription school founded in Randolph County, North Carolina, in the present-day town of Trinity.[16] Organized by the Union Institute Society, a group of Methodists and Quakers, Brown's Schoolhouse became the Union Institute Academy in 1841 when North Carolina issued a charter. The academy was renamed Normal College in 1851, and then Trinity College in 1859 because of support from the Methodist Church.[16] In 1892, Trinity College moved to Durham, largely due to the generosity of Julian S. Carr and Washington Duke, powerful and respected Methodists who had grown wealthy through the tobacco and electrical industries.[10] Carr donated land in 1892 for the original Durham campus, which is now known as East Campus. At the same time, Washington Duke gave the school $85,000 ($2,880,000 adjusted for inflation) for an initial endowment and construction costs—later augmenting his generosity with three separate $100,000 contributions in 1896, 1899, and 1900—with the stipulation that the college "open its doors to women, placing them on an equal footing with men."[17] Duke would accelerate its mission to become a global university in 1910 with the promotion of William Preston Few as the new president of Trinity College, who sought to establish the university as a southern counterpart to Yale and Harvard.[18]

In 1924, Washington Duke's son, James B. Duke, established The Duke Endowment with a $40 million trust fund. Income from the fund was to be distributed to hospitals, orphanages, the Methodist Church, and four colleges (including Trinity College). Few, who remained president of Trinity, insisted that the institution be renamed Duke University to honor the family's generosity and to distinguish it from the myriad other colleges and universities carrying the "Trinity" name. At first, James B. Duke thought the name change would come off as self-serving, but eventually, he accepted Few's proposal as a memorial to his father.[10] Money from the endowment allowed the university to grow quickly. Duke's original campus, East Campus, was rebuilt from 1925 to 1927 with Georgian-style buildings. By 1930, the majority of the Collegiate Gothic-style buildings on the campus one mile (1.6 km) west were completed, and construction on West Campus culminated with the completion of Duke Chapel in 1935.[19]

In 1878, Trinity (in Randolph County) awarded A.B. degrees to three sisters—Mary, Persis, and Theresa Giles—who had studied both with private tutors and in classes with men. With the relocation of the college in 1892, the board of trustees voted to again allow women to be formally admitted to classes as day students. At the time of Washington Duke's donation in 1896, which carried the requirement that women be placed "on an equal footing with men" at the college, four women were enrolled; three of the four were faculty members' children. In 1903 Washington Duke wrote to the board of trustees withdrawing the provision, noting that it had been the only limitation he had ever put on a donation to the college. A woman's residential dormitory was built in 1897 and named the Mary Duke Building, after Washington Duke's daughter. By 1904, 54 women were enrolled in the college. In 1930, the Woman's College was established as a coordinate to the men's undergraduate college, which had been established and named Trinity College in 1924.[20]

According to Duke University Human Rights Center, the school's "policy in the 1920s excluded blacks from admissions and also restricted blacks from using certain campus facilities such as the dining halls and dorm housing ... In 1948, a group of divinity school students petitioned the divinity school to desegregate – the first concerted effort to push for the desegregation of Duke's admission policy."[21]

Expansion and growth

[edit]Engineering, which had been taught at Duke since 1903, became a separate school in 1939. The university president's official residence, the J. Deryl Hart House, was completed in 1934. In athletics, Duke hosted and competed in the first Rose Bowl ever played outside California in Wallace Wade Stadium in 1942; the second such game was played in Arlington, Texas, in 2021, moved as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.[16][22] During World War II, Duke was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a navy commission.[23] In 1963 the Board of Trustees officially desegregated the undergraduate college.[24]

Duke enrolled its first black graduate students in 1961.[25] The school did not admit Black undergraduates until September 1963. The teaching staff remained all-White until 1966.[26]

Increased activism on campus during the 1960s prompted Martin Luther King Jr. to speak at the university in November 1964 on the progress of the Civil Rights Movement. Following Douglas Knight's resignation from the office of university president, Terry Sanford, the former governor of North Carolina, was elected president of the university in 1969, propelling The Fuqua School of Business' opening, the William R. Perkins library completion, and the founding of the Institute of Policy Sciences and Public Affairs (now the Sanford School of Public Policy). The separate Woman's College merged back with Trinity as the liberal arts college for both men and women in 1972.

Beginning in the 1970s, Duke administrators began a long-term effort to strengthen Duke's reputation both nationally and internationally. Interdisciplinary work was emphasized, as was recruiting minority faculty and students. During this time it also became the birthplace of the first Physician Assistant degree program in the United States.[27][28][29] Duke University Hospital was finished in 1980 and the student union building was fully constructed two years later. In 1986 the men's soccer team captured Duke's first National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championship, and the men's basketball team followed shortly thereafter with championships in 1991 and 1992, then again in 2001, 2010, and 2015.

Duke Forward, a seven-year fundraising campaign, raised $3.85 billion by August 2017.[30]

Recent history

[edit]

In 2014, Duke removed the name of Charles B. Aycock, a white-supremacist governor of North Carolina, from an undergraduate dormitory.[32] It is now known as the East Residence Hall.

On August 19, 2017, following the violent clashes at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, the statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee was removed from the entrance to Duke University Chapel, after having been vandalized by protesters.[33][34][35]

In August 2020, the first undergraduates from Duke Kunshan University arrived for their study abroad on Duke's campus. Due to COVID-19, Chinese Duke undergraduate and graduate students unable to travel to the United States were reciprocally hosted at Duke Kunshan campus.[36]

Controversies

[edit]In 2006, three men's lacrosse team members were falsely accused of rape,[37][38] which garnered significant media attention.[39] On April 11, 2007, North Carolina Attorney General Roy Cooper dropped all charges and declared the three players innocent. Cooper stated that the charged players were victims of a "tragic rush to accuse."[40][41] The District Attorney, Mike Nifong, was subsequently disbarred.[42]

In 2019, Duke paid $112.5 million to settle False Claims Act allegations related to scientific research misconduct. A researcher at the school was falsifying or fabricating research data in order to win grants for financial gain. The researcher was arrested in 2013 on charges of embezzling funds from the university. The scheme was exposed by the allegations made through a lawsuit, filed by a whistleblower, who had worked as a Duke employee, and discovered the false data.[43][44]

In response to the misconduct settlement, Duke established an advisory panel of academics from Caltech, Stanford and Rockefeller University. Based on the recommendations of this panel, Duke Office of Scientific Integrity (DOSI) was established under the leadership of Lawrence Carin, an engineering professor who is one of the world's leading experts on machine learning and artificial intelligence[45] The establishment of this office brings Duke's research practices in line with those at peer institutions like Johns Hopkins University.[46]

Campus

[edit]

Duke University currently owns 256 buildings on 8,693 acres (35.18 km2) of land, which includes the 7,044 acres (28.51 km2) Duke Forest.[6] The campus is divided into four main areas: West, East, and Central campuses and the Medical Center, which are all connected via a free bus service. On the Atlantic coast in Beaufort, Duke owns 15 acres (61,000 m2) as part of its marine lab. One of the major public attractions on the main campus is the 54-acre (220,000 m2) Sarah P. Duke Gardens, established in the 1930s.[6]

Duke students often refer to the West Campus as "the Gothic Wonderland", a nickname referring to the Collegiate Gothic architecture of West Campus, a style chosen by the Campus's founders after campus visits to the University of Chicago, Yale, and Princeton.[47][48][49] Much of the campus was designed by Julian Abele, one of the first prominent African-American architects and the chief designer in the offices of architect Horace Trumbauer.[50] The residential quadrangles are of an early and somewhat unadorned design, while the buildings in the academic quadrangles show influences of the more elaborate late French and Italian styles. The freshmen campus, known as East Campus, is composed of buildings in the Georgian architecture style. In 2011, Travel+Leisure listed Duke among the most beautiful college campuses in the United States.[51]

Duke Chapel stands at the center of West Campus on the highest ridge. Constructed from 1930 to 1935 from Duke stone, the chapel seats 1,600 people and, at 210 feet (64 m) is one of the tallest buildings in Durham County.[52]

West, East, and Central Campuses

[edit]

West Campus, considered the main campus of the university, houses the sophomores and juniors, along with some seniors.[53] Most of the academic and administrative centers are located there. Main West Campus, with Duke Chapel at its center, contains the majority of residential quads to the south, while the main academic quad, library, and Medical Center are to the north. The campus, spanning 720 acres (2.9 km2), includes Science Drive, which is the location of science and engineering buildings. The residential quads on West Campus are Craven Quad, Crowell Quad, Edens Quad, Few Quad, Keohane Quad, Kilgo Quad, and Wannamaker Quad.[54] Most of the campus eateries and sports facilities – including the historic basketball stadium, Cameron Indoor Stadium – are on West Campus.[55]

East Campus, the original location of Duke after it moved to Durham,[56] functions as a first-year campus, housing the university's freshmen dormitories as well as the home of several academic departments. Since the 1995–96 academic year, all freshmen—and only freshmen, except for upperclassmen serving as Resident Assistants—have lived on East Campus, an effort to build class unity. The campus encompasses 172 acres (700,000 m2) and is 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from West Campus.[6] Studies, Art History, History, Cultural Anthropology, Literature, Music, Philosophy, and Women's Studies are housed on East.[56] Programs such as dance, drama, education, film, and the University Writing Program reside on East. The self-sufficient East Campus contains the freshmen residence halls, a dining hall, coffee shop, post office, Lilly Library, Baldwin Auditorium, a theater, Brodie Gym, tennis courts, several disc golf baskets, and a walking track as well as several academic buildings.[56] The East Campus dorms are Alspaugh, Basset, Bell Tower, Blackwell, Brown, East House (formerly known as Aycock), Epworth, Gilbert-Addoms, Giles, West House (formerly known as Jarvis), Pegram, Randolph, Southgate, Trinity, and Wilson.[57] Separated from downtown by a short walk, the area was the site of the Women's College from 1930 to 1972.[56]

Central Campus, consisting of 122 acres (0.49 km2) between East and West campuses, housed around 1,000 sophomores, juniors, and seniors, as well as around 200 professional students in double or quadruple apartments.[58] However, the housing of undergraduates on Central Campus ended after the 2018–2019 school year[59] and the respective buildings were demolished.[60] Central Campus is home to the Nasher Museum of Art, the Freeman Center for Jewish Life, the Center for Muslim Life, the Campus Police Department, Office of Disability Management, a Ronald McDonald House, and administrative departments such as Duke Residence Life and Housing Services. Central Campus has several recreation and social facilities such as basketball courts, a sand volleyball court, a turf field, barbecue grills and picnic shelters, a general gathering building called "Devil's Den", a restaurant known as "Devil's Bistro", a convenience store called Uncle Harry's, and the Mill Village. The Mill Village consists of a gym and group study rooms.[58][61]

In December 2016, Duke University purchased an apartment complex, now known as 300 Swift.[62] Swift houses upperclassmen, in addition to the West Campus area, and is located between East and West Campus.

Duke University Hospital and Health System

[edit]

Duke University Hospital is a 957-acute care bed academic tertiary care facility located in Durham, North Carolina. Established in 1930, it is the flagship teaching hospital for Duke University Health System, a network of physicians and hospitals serving Durham County and Wake County, North Carolina, and surrounding areas, as well as one of three Level I referral centers for the Research Triangle of North Carolina (the other two are UNC Hospitals in nearby Chapel Hill and WakeMed Raleigh in Raleigh).[63]

Duke University Health System combines Duke University School of Medicine, Duke University School of Nursing, Duke Clinic, and the member hospitals into a system of research, clinical care, and education.[63]

In early 2012, Duke Cancer Center opened next to Duke Hospital in Durham.[64] The patient care facility consolidates nearly all of Duke's outpatient clinical care services.

Other key places

[edit]

Duke Forest, established in 1931, consists of 7,044 acres (28.51 km2) in six divisions, just west of West Campus.[6] The largest private research forest in North Carolina and one of the largest in the nation,[65] Duke Forest demonstrates a variety of forest stand types and silvicultural treatments. Duke Forest is used extensively for research and includes the Aquatic Research Facility, Forest Carbon Transfer and Storage (FACTS-I) research facility, two permanent towers suitable for micrometeorological studies, and other areas designated for animal behavior and ecosystem study.[66] More than 30 miles (48 km) of trails are open to the public for hiking, cycling, and horseback riding.[67] Duke Lemur Center, located inside Duke Forest, is the world's largest sanctuary for rare and endangered strepsirrhine primates.[68] Founded in 1966, Duke Lemur Center spans 85 acres (34 ha) and contains nearly 300 animals of 25 different species of lemurs, galagos and lorises.[69]

The Sarah P. Duke Gardens, established in the early 1930s, is situated between West Campus and Central Campus. The gardens occupy 55 acres (22 ha), divided into four major sections:[70] the original Terraces and their surroundings; the H.L. Blomquist Garden of Native Plants, devoted to flora of the Southeastern United States; the W.L. Culberson Asiatic Arboretum, housing plants of Eastern Asia, as well as disjunct species found in Eastern Asia and Eastern North America; and the Doris Duke Center Gardens. There are five miles (8.0 km) of allées and paths throughout the gardens.[70]

Duke University Allen Building was the site of student protest in the late 1960s. In 1969, six years after the university began to allow African-American students to enroll, dozens of Black students overtook the Allen Building and barricaded themselves inside of it. Their justification included a "white top and a black bottom" power structure, according to the former director of employee relations; the university's gradualist and arguably complacent approach to civil rights; high attrition rates for Black students; lack of unionization rights for nonacademic employees; lack of institutional power and self-determination for a Black studies department; "police harassment for Black students"; "racist living conditions"; and "tokenism of Black representation in university power structures" among others. Their underlying demand was "to be taken seriously as human beings and to be treated as any respected human being would be treated." Provost Marcus E. Hobbes complained that the African-American students "wanted to run the University." At around 8 a.m., these students entered the Allen Building, asked everyone inside to leave and promptly barricaded themselves inside. The university called the police and, almost before law enforcement entered the building (it was widely understood by students and administration that the police would have likely brutally beat and possibly killed the unarmed Black students), the students exited with their trenchcoats over their faces. Meanwhile, white students and faculty had formed a human shield around the building and a brawl between the police and students ensued, sending a handful of students to the hospital. University president Vincent Price labelled the Takeover as "one of the most pivotal moments in our university's history," claiming that the protestors "changed this place for the better and improved the lives of many who followed."[71]

Duke University Marine Laboratory, located in the town of Beaufort, North Carolina, is also technically part of Duke's campus. The marine lab is situated on Pivers Island on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, 150 yards (140 m) across the channel from Beaufort. Duke's interest in the area began in the early 1930s and the first buildings were erected in 1938.[72] The resident faculty represent the disciplines of oceanography, marine biology, marine biomedicine, marine biotechnology, and coastal marine policy and management. The Marine Laboratory is a member of the National Association of Marine Laboratories.[72] In May 2014, the newly built Orrin H. Pilkey Marine Research Laboratory was dedicated.[73]

Duke stone

[edit]

The distinctive stone used for West Campus and other Duke buildings is said to have seven primary colors and seventeen shades of color.[74][75][76] The use of Duke stone has been given partial credit for the university's success: "Duke in fact became a great university in part because it looked like one from the start".[77]

During the planning of the Collegiate Gothic buildings,[77] James B. Duke initially suggested the use of stone from the Princeton quarry, but the plans were later amended to purchase a local quarry in Hillsborough to reduce costs.[78] After a search for a locally sourced stone suitable for construction in a style "that made it look like the university was growing out of the ground, like it had been here forever,"[79] Duke stone and its source quarry in Hillsborough were identified by Duke University Comptroller Frank Clyde Brown and purchased by the university in 1925.[80] Comptroller Brown, who oversaw the planning and construction of the Gothic buildings, wrote that Duke stone "is much warmer and softer in coloring than the Princeton, and it will look very much older and have a much more attractive antique effect."[81]

Duke stone is a type of Carolina 'slate' or 'bluestone', a metamorphic phyllite rock,[82] with both andesite and dacite mineral composition.[83] Dacitic phyllite is a predominant type of rock found through the Carolina Slate Belt.[84] Duke stone and the Carolina Slate Belt, like the greater Carolina Terrane,[85] are thought to have formed in the Iapetus Ocean off the coast of Gondwana by a chain of volcanic islands known as 'Carolinia',[86] starting around 650 million years ago.[84][87]

The Carolina Slate Belt contains stone of both meta-volcanic and meta-sedimentary origin.[88][89] The geological literature finds the pre-metamorphosis origin of Duke stone to be variously volcanic and sedimentary: it was likely originally formed by sedimentation of volcanic material.[87] A USGS geologist concludes: "The Duke quarry phyllite was derived from argillite, tuff or tuffaceous sandstone, and volcanic breccia. Occurrence of laminated argillites suggests marine deposition. … There is insufficient evidence to determine if the volcanic material was deposited directly by igneous action or if it was re-worked by sedimentary processes. Presence of lava flows and very coarse breccias in Orange County suggest that the volcanic centers were relatively near."[90][83] A UNC geologist concurred that "original features of the phyllite have been obscured by deformation and recrystallization, but the rock apparently was derived from argillites and tuffs," and that "sedimentary reworking of volcanic materials is to be expected."[91]

After its initial formation, Duke stone underwent several metamorphic events, including the collision of Carolinia with Laurentia.[92] The Carolinia-Laurentia collision started around 375 Mya, which coincides with timing of the Acadian orogeny that formed the Appalachian Mountains. Though Duke stone contains no fossils, other areas of the Carolina Terrane contain fossilized corals and trilobites that were used to establish that this formation is exotic to the main North American (Laurentia) landmass.[86][89][92]

The Duke stone quarry now occupies a five-acre (2.0 ha) section of the Hillsboro Division of the Duke Forest.[93] In new construction and repairs on Duke campus, the use of Duke stone is strictly regulated: "All stones shall be laid on their natural beds, with 20 percent of stone being split face and 80 percent seam face, mixed proportionately to show variations of stone coloring".[94] In recent years, high cost of quarrying the stone, and the irregular knapped ashlar shapes with its associated high stonemasonry costs has led to the university establishing a mix of bricks to imitate the Duke stone colors.[77]

Recent construction

[edit]A number of construction projects in recent years include renovations to Duke Chapel, Wallace Wade Stadium (football) and Cameron Indoor Stadium (basketball).[95]

In early 2014, the Nicholas School of the Environment opened a new home, Environmental Hall,[96] a five-story, glass-and-concrete building that incorporates the highest sustainable features and technologies, and meets or exceeds the criteria for LEED platinum certification. The School of Nursing in April 2014 opened a new 45,000 sq ft (4,200 m2) addition to the Christine Siegler Pearson Building.[97] In summer 2014, a number of construction projects were completed.[98] The project is part of the final phase of renovations to Duke's West Campus libraries that have transformed one of the university's oldest and most recognizable buildings into a state-of-the-art research facility. The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library reopened in August 2015 after about $60 million in renovations to the sections of the building built in 1928 and 1948. The renovations include more space, technology upgrades and new exhibits.[99] In 2013, construction projects included transforming buildings like Gross Hall and Baldwin Auditorium, plus new construction such as the Events Pavilion. About 125,000 sq ft (11,600 m2) was updated at Gross Hall, including new lighting and windows and a skylight.[100] Baldwin's upgrades include a larger stage, more efficient air conditioning for performers and audience and enhanced acoustics that will allow for the space to be "tuned" to each individual performance.[101] The 25,000 sq ft (2,300 m2) Events Pavilion opened to students in 2013 and serves as temporary dining space while the West Campus Union undergoes major renovations, expected to be completed in the spring of 2016.

From February 2001 to November 2005, Duke spent $835 million on 34 major construction projects as part of a five-year strategic plan, "Building on Excellence".[102] Completed projects since 2002 include major additions to the business, law, nursing, and divinity schools, a new library, the Nasher Museum of Art, a football training facility, two residential buildings, an engineering complex, a public policy building, an eye institute, two genetic research buildings, a student plaza, the French Family Science Center, and two new medical-research buildings.[103]

Singapore and China

[edit]In April 2005, Duke and the National University of Singapore signed a formal agreement under which the two institutions would partner to establish Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore.[104][105] Duke-NUS is intended to complement the National University of Singapore's existing undergraduate medical school, and had its first entering class in 2007.[106] The curriculum is based on that of Duke University School of Medicine. Sixty percent of matriculates are from Singapore and 40% are from over 20 countries. The school is part of the National University of Singapore system, but distinct in that it is overseen by a governing board, including a Duke representative who has veto power over any academic decision made by the board.[107][105]

In 2013, Duke Kunshan University (abbreviated "DKU"), a partnership between Duke University, Wuhan University, and the city of Kunshan, was established in Kunshan, China.[108] The university runs Duke degree graduate programs and an undergraduate liberal arts college. Undergraduates are awarded degrees from both Duke Kunshan University and Duke University upon graduation and become members of Duke and DKU's alumni organizations.[109] DKU conducted research projects on climate change, health-care policy and tuberculosis prevention and control.[110]

Administration and organization

[edit]| School founding | |

|---|---|

| School | Year founded |

| Trinity College of Arts and Sciences | 1838 |

| Duke University School of Law | 1868 |

| Graduate School of Duke University | 1926 |

| Duke Divinity School | 1926 |

| Duke University School of Medicine | 1930 |

| Duke University School of Nursing | 1931 |

| Nicholas School of the Environment | 1938 |

| Pratt School of Engineering | 1939 |

| Fuqua School of Business | 1969 |

| Sanford School of Public Policy | 1971 |

| Duke-NUS Medical School | 2007 |

| Duke Kunshan University | 2013 |

Duke University has 12 schools and institutes, three of which host undergraduate programs: Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, Pratt School of Engineering, and Duke Kunshan University.[111][112]

The university has "historical, formal, ongoing, and symbolic ties" with the United Methodist Church, but is a nonsectarian and independent institution.[113][114][115][116]

Duke's endowment had a market value of $12.1 billion in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2022.[4] The university's special academic facilities include an art museum, several language labs, Duke Forest, Duke Herbarium,[117] a lemur center, a phytotron, a free-electron laser, a nuclear magnetic resonance machine, a nuclear lab, and a marine lab. Duke is a leading participant in the National Lambda Rail Network and runs a program for gifted children known as the Talent Identification Program.[118][119]

Academics

[edit]

Undergraduate admissions

[edit]| Undergraduate admissions statistics | |

|---|---|

| Admit rate | 6.2% ( |

| Yield rate | 56.4% ( |

| Test scores middle 50% | |

| SAT Total | 1480–1560 ( |

| ACT Composite | 34–35 ( |

Admission to Duke is defined by U.S. News & World Report as "most selective." Duke received nearly 50,000 applications for the Class of 2025, with an overall acceptance rate of 6.2%.[122] The yield rate (the percentage of accepted students who choose to attend) for the Class of 2023 was 54%.[123] The Class of 2024 had a median ACT range of 34–35 and an SAT range of 1500–1570.[124] (Test score ranges account for the 25th–75th percentile of accepted students.)

From 2001 to 2011, Duke has had the sixth highest number of Fulbright, Rhodes, Truman, and Goldwater scholarships in the nation among private universities.[125][126][127][128] The university practices need-blind admissions and meets 100% of admitted students' demonstrated needs. About 50 percent of all Duke students receive some form of financial aid, which includes need-based aid, athletic aid, and merit aid. The average need-based grant for the 2019–20 academic year was $54,255.[6] In 2020, a study by the Chronicle of Higher Education ranked Duke first on its list of "Colleges That Are the Most Generous to the Financially Neediest Students."[129]

Roughly 60 merit-based full-tuition scholarships are offered, including the Angier B. Duke Memorial Scholarship awarded for academic excellence, the Benjamin N. Duke Scholarship awarded for community service, and the Robertson Scholars Leadership Program, a joint scholarship and leadership development program granting full student privileges at both Duke and UNC-Chapel Hill. Other scholarships are geared toward students in North Carolina, African-American students, children of alumni, and high-achieving students requiring financial aid.[130]

Duke's president, Vincent Price, has described efforts to ban legacy admissions as "troublesome".[131][132] A 2022 survey by The Chronicle found about 22% of first-year students were the child or sibling of a Duke alumnus.[133]

Graduate profile

[edit]In 2023, the School of Medicine received more than 7,000 applications and accepted approximately 2.9% of them, while the average GPA and MCAT scores for accepted students in 2023 were 3.92 and 520, respectively.[134] The School of Law accepted approximately 10.5% of its applicants for the Class of 2026, while enrolling students had a median GPA of 3.87 and median LSAT of 170.[135]

The university's graduate and professional schools include the Graduate School, Pratt School of Engineering, Nicholas School of the Environment, School of Medicine, Duke-NUS Medical School, School of Nursing, the Fuqua School of Business, School of Law, Divinity School, and Sanford School of Public Policy.[136]

Undergraduate curriculum

[edit]Duke offers 46 arts and sciences majors, four engineering majors, 52 minors (including two in engineering) and Program II, which allows students to design their own interdisciplinary major in arts & sciences, and IDEAS, which allows students to design their own engineering major.[137] Twenty-four certificate programs also are available.[137] Students pursue a major and can pursue a combination of a total of up to three, including minors, certificates, and/or a second major. Eighty-five percent of undergraduates enroll in the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences. The balance enroll in Duke's Pratt School of Engineering.[138] Undergraduates at Duke Kunshan can choose from 15 interdisciplinary majors approved by Duke and the Chinese Ministry of Education,[139] and more majors are in the process of approval, including a major in behavioral science.[140]

Trinity College of Arts and Sciences

[edit]

At Duke, the undergraduate experience centers around Trinity College, with Engineering students taking approximately half of their Duke common curriculum within Trinity.[141] Engineering students are able to enroll in any classes within the liberal arts college, and Trinity students are able to enroll in any classes within the engineering college. The undergraduate curriculum includes a focus on the humanities. All freshman students take a writing class and a current-issues seminar class.[142] The Graduate School trains roughly 1200 doctoral and masters students in the arts and sciences as well as in divinity, engineering, business, and environmental and earth sciences.

Trinity's curriculum operates under the revised version of "Curriculum 2000".[143] The curriculum aims to help students develop critical faculties and judgment by learning how to access, synthesize, and communicate knowledge effectively. The intent is to assist students in acquiring perspective on current and historical events, conducting research and solving problems, and developing tenacity and a capacity for hard and sustained work.[143] Freshmen can elect to participate in the FOCUS Program, which allows students to engage in an interdisciplinary exploration of a specific topic in a small group setting in their first semesters.[144]

Pratt School of Engineering

[edit]

The curriculum of Duke's Pratt School of Engineering, significantly transformed in recent years, immerses students in design, computing, research, and entrepreneurship — but still accommodates educational opportunities, including double majors, in a variety of disciplines from across Duke.[145] The school emphasizes undergraduate research opportunities with faculty. Research and design opportunities arise through a real-world design course for first-year students,[146] internships, independent study and research fellowships,[147] and through design-focused capstone courses. More than 60 percent of Duke Engineering undergraduates have an intensive research experience during their four years, and nearly a fifth publish or present a research paper off-campus. Nearly 54 percent of Duke Engineering undergraduates intern or study abroad. Eighty-five percent have jobs or job offers at the time of graduation.[148] Since July 2018, Duke engineering students have held the Guinness World Record for inventing the world's most fuel-efficient vehicle – powered by a fuel cell, it achieved 14,573 miles per gallon equivalent. In 2019, Duke Engineering students earned a second Guinness World Record for the world's most efficient all-electric vehicle – 797 miles per kilowatt-hour.[149]

Research expenditures at Duke Engineering exceed $88 million per year. Its faculty is highly ranked in overall research productivity among U.S. engineering schools by Academic Analytics.[150] More than 30 Duke alumni and faculty have been elected to the prestigious National Academy of Engineering since its founding in 1964.[151] The school was created by Duke's board of trustees in 1939. It was named in 1999 following a $35 million gift by Edmund T. Pratt Jr., a 1947 graduate and former chief executive of Pfizer.[152] Duke University Pratt School of Engineering celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2014–2015.[153]

Hudson Hall is the oldest engineering building at Duke, constructed in 1948. It was renamed to honor Fitzgerald S. "Jerry" Hudson (E'46) in 1992.[154]

The Fitzpatrick Center for Interdisciplinary Engineering, Medicine and Applied Sciences (FCIEMAS) opened in August 2004. Research facilities focus on the fields of photonics, bioengineering, communications, and materials science and materials engineering. The aim of the building was to emphasize interdisciplinary activities and encourage cross-departmental interactions. The building houses numerous wet bench laboratories (highlighted by a world-class nanotechnology research wing), offices, teaching spaces, and a café.[154] FCIEMAS is also home to the Master of Engineering Management Program offices. The construction of FCIEMAS took more than three years and cost more than $97 million.

The newest building is the Wilkinson Building which is a 150,000-square-foot building opened for classes in early 2021 with new spaces for education and research related to interdisciplinary themes of improving human health, advancing computing and intelligent systems, and sustainability.[155] It is located at Research Drive and Telcom Drive next to Bostock Library, also houses Duke Engineering's entrepreneurship initiatives. The building's name recognizes lifetime philanthropic and service contributions of Duke Engineering alumnus Jerry C. Wilkinson and family.[156]

Duke Kunshan University

[edit]

Duke Kunshan hosts the newest of Duke's undergraduate programs, with its curriculum focused heavily on interdisciplinary coursework and majors—described as a "research-inflected liberal arts experience".[157][158] The curriculum is rooted in seven "animating principles", among them Rooted Globalism, Collaborative Problem-Solving, Research and Practice, Lucid Communication, Independence and Creativity, Wise Leadership, and A Purposeful Life.[157] Noah M. Pickus, former Associate Provost and Senior Advisor at Duke and Dean of Undergraduate Curricula Affairs and Faculty Development at Duke Kunshan University, oversaw the development of the university's future-focused, internationalized curriculum.[159] The campus also hosts five Master's programs administered by Duke's graduate schools, including Medical Physics, Global Health, Environmental Policy, Management Studies and Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Libraries and museums

[edit]Duke Libraries includes the Perkins, Bostock, and Rubenstein Libraries on West Campus, the Lilly and Music Libraries on East Campus, the Pearse Memorial Library at Duke Marine Lab, and the separately administered libraries serving the schools of business, divinity, law, medicine, and Duke Kunshan University.[160]

Duke's art collections are housed at the Nasher Museum of Art on Central Campus. The museum was designed by Rafael Viñoly and is named for Duke alumnus and art collector Raymond Nasher. The museum opened in 2005 at a cost of over $23 million and contains over 13,000 works of art, including works by William Cordova, Marlene Dumas, Olafur Eliasson, David Hammons, Barkley L. Hendricks, Christian Marclay, Kerry James Marshall, Alma Thomas, Hank Willis Thomas, Bob Thompson, Kara Walker, Andy Warhol, Carrie Mae Weems, Ai Weiwei, Fred Wilson, and Lynette Yiadom Boakye.[161]

Research

[edit]

The National Science Foundation ranked Duke 9th among American universities for research and development expenditures in 2022 with $1.39 billion.[162][163] In fiscal year 2021, Duke received $608 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health, ranked third in the nation.[164] Duke is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity."[165]

Throughout the school's history, Duke researchers have made breakthroughs, including the biomedical engineering department's development of the world's first real-time, three-dimensional ultrasound diagnostic system and the first engineered blood vessels and stents.[166] In 2015, Paul Modrich shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of mechanism of DNA repairs.[167] In 2012, Robert Lefkowitz along with Brian Kobilka, who is also a former affiliate, shared the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their work on cell surface receptors.[168] Duke has pioneered studies involving nonlinear dynamics, chaos, and complex systems in physics.

In May 2006 Duke researchers mapped the final human chromosome, which made world news as it marked the completion of the Human Genome Project.[169] Reports of Duke researchers' involvement in new AIDS vaccine research surfaced in June 2006.[170] The biology department combines two historically strong programs in botany and zoology, while one of the divinity school's leading theologians is Stanley Hauerwas, whom Time named "America's Best Theologian" in 2001.[171] The graduate program in literature boasts several internationally renowned figures, including Fredric Jameson,[172] Michael Hardt,[173] and Rey Chow, while philosophers Robert Brandon and Lakatos Award-winner Alexander Rosenberg contribute to Duke's ranking as the nation's best program in philosophy of biology, according to the Philosophical Gourmet Report.[174]

Rankings and reputation

[edit]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Undergraduate rankings

[edit]In 2016, The Washington Post ranked Duke seventh overall based on the accumulated weighted average of the rankings from U.S. News & World Report, Washington Monthly, Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education, Times Higher Education (global), Money and Forbes.[184]

In 2021, Duke was ranked fifth in the Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings, having risen five places in the past year.[185] In addition, Duke was ranked second for student outcomes, tied with Harvard, M.I.T., and Stanford. The rankings take into account graduation rate, teaching reputation, graduate salaries, and student debt.[186]

In 2020, Duke was ranked 22nd in the world by U.S. News & World Report and 20th in the world by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[187][188] QS World University Rankings ranked Duke 50th in the world for its 2023 rankings.[189] Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) ranked Duke 20th globally in its 2020–21 report.[190] Duke was ranked 28th best globally by the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) in 2019, focusing on quality of scientific research and the number of Nobel Prizes.[191] The 2010 report by the Center for Measuring University Performance puts Duke at sixth in the nation.[192]

Duke also ranked 34th in the world and 12th in the country on Times Higher Education's global employability ranking in 2021.[193]

Duke ranks fifth among national universities to have produced Rhodes, Marshall, Truman, Goldwater, and Udall Scholars.[194] As of 2022, Duke graduates have received 20 Churchill Scholarships to the University of Cambridge.[195] As of 2020, Duke has produced 8 Mitchell Scholars.[196] Kiplinger's 50 Best Values in Private Universities 2013–14 ranks Duke at fifth best overall after taking financial aid into consideration.[197]

In a 2016 study by Forbes, Duke ranked 11th among universities in the United States that have produced billionaires and first among universities in the South.[198] Forbes magazine ranked Duke seventh in the world on its list of 'power factories' in 2012.[199] Duke was ranked 17th on Thomson Reuters' list of the world's most innovative universities in 2015. The ranking graded universities based on patent volume and research output among other factors.[200] In 2015, NPR ranked Duke first on its list of "schools that make financial sense".[201] In 2016, Forbes ranked Duke sixth on its list of "Expensive Schools Worth Every Penny".[202]

Graduate school rankings

[edit]Duke has been named one of the top universities for graduate outcomes several years in a row, having tied with Harvard University and Yale University.[203][204] In U.S. News & World Report's "America's Best Graduate Schools 2023–2024", Duke's medical school ranked 5th in research.[205] The School of Law was also ranked 5th in those same rankings,[206] with Duke's nursing school ranked 2nd[207] while the Sanford School of Public Policy ranked fifth in Public Policy Analysis for 2019.[208] Among business schools in the United States, the Fuqua School of Business is ranked tied for tenth overall by U.S. News & World Report for 2020, while BusinessWeek ranked its full-time MBA program first in the nation in 2014.[209][210] The graduate programs of Duke's Pratt School of Engineering ranked 24th in the U.S. by U.S. News & World Report in its 2020 rankings.[211]

Times Higher Education ranked the mathematics department tenth in the world in 2011.[212] Duke's graduate-level specialties that are ranked among the top ten in the nation include areas in the following departments: biological sciences, medicine, nursing, engineering, law, business, English, history, physics, statistics, public affairs, physician assistant (ranked #1), clinical psychology, political science, and sociology.[213] In 2007, Duke was ranked 22nd in the world by Wuhan University's Research Center for Chinese Science Evaluation. The ranking was based on journal article publication counts and citation frequencies in over 11,000 academic journals from around the world. A 2012 study conducted by academic analytics ranks Duke fourth in the nation (behind only Harvard, Stanford, and MIT) in terms of faculty productivity.[214] In 2013, Duke Law ranked sixth in Forbes magazine's ranking of law schools whose graduates earn the highest starting salaries.[215] In 2013, Duke's Fuqua School of Business was ranked sixth in terms of graduate starting salaries by U.S. News & World Report. In the same year, a ranking compiled by the University of Texas at Dallas ranked Fuqua fifth in the world based on the research productivity of its faculty. The MEM (Masters in Engineering Management) program has been ranked third in the world by Eduniversal[216] In 2013, Forbes ranked Duke fourth in the nation in terms of return on investment (ROI). The ranking used alumni giving as a criterion to determine which private colleges offer the best returns.[217] In 2023, Above the Law ranked Duke Law first in the nation in its ranking of law schools based on employment outcomes for the second year in a row.[218] In 2013, Business Insider ranked Duke's Fuqua School of Business fifth in the world based on an extensive survey of hiring professionals.[219] In the same year, Forbes magazine ranked Fuqua eighth in the country based on return on investment. In 2014, Duke was named the 20th best global research university according to rankings published by U.S. News & World Report and the University Ranking by Academic Performance published by Middle East Technical University. The U.S. News ranking was based on 10 indicators that measure academic research performance and global reputations.[220] The University Ranking by Academic Performance uses citation data obtained from Thomson Reuters' Web of Science to rank universities based on research output.[221]

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[222] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 41% | ||

| Asian | 21% | ||

| Other[a] | 11% | ||

| Hispanic | 10% | ||

| Black | 9% | ||

| Foreign national | 8% | ||

| Native American | 1% | ||

| Gender diversity | |||

| Male | 49% | ||

| Female | 51% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 12% | ||

Student body

[edit]Duke's student body consists of 6,789 undergraduates and 9,991 graduate and professional students (as of fall 2021).[6] The median family income of Duke students is $186,700, with 56% of students coming from the top 10% highest-earning families and 17% from the bottom 60% as of 2013[update].[223] The New York Times described Duke in 2023 as the least economically diverse top-ranked college in the U.S.[224]

Residential life

[edit]Duke requires its students to live on campus for the first three years of undergraduate life, except for a small percentage of second-semester juniors who are exempted by a lottery system.[53] This requirement is justified by the administration as an effort to help students connect more closely with one another and sustain a sense of belonging within Duke.[225] Thus, 85% of undergraduates live on campus.[226] All freshmen are housed in one of 14 residences on East Campus. These buildings range in occupancy size from 50 (Epworth—the oldest residence hall, built in 1892 as "the Inn"), which has not been used as a student dorm since the 2017–2018 school year, to 250 residents (Trinity).[227][228] Most of these are in the Georgian style typical of the East Campus architecture. Although the newer residence halls differ in style, they still relate to East's Georgian heritage. Learning communities connect the residential component of East Campus with students of similar academic and social interests.[229] Similarly, students in FOCUS, a first-year program that features courses clustered around a specific theme, live together in the same residence hall as other students in their cluster.[230]

Sophomores and juniors reside on West Campus, while the majority of undergraduate seniors choose to live off campus.[231] West Campus contains seven quadrangles—the four along "Main" West were built in the 1930s, while three newer ones have since been added. Central Campus provided housing for over 1,000 students in apartment buildings, until 2019.[232] All housing on West Campus is organized into "houses"—sections of residence halls—to which students can return each year. House residents create their house identities. There are houses of unaffiliated students, as well as wellness houses and living-learning communities that adopt a theme such as the arts or foreign languages. There are also numerous "selective living groups" on campus for students wanting self-selected living arrangements. SLGs are residential groups similar to fraternities or sororities, except they are generally co-ed and unaffiliated with any national organization. Many of them also revolve around a particular interest such as entrepreneurship, civic engagement or African-American or Asian culture. Fifteen fraternities and nine sororities also are housed on campus. Most of the non-fraternity selective living groups are coeducational.[233]

Greek and social life

[edit]

About 30% of undergraduate men and about 40% of undergraduate women at Duke are members of fraternities and sororities.[226] Most of the 17 Interfraternity Council recognized fraternity chapters live in sections within the residence halls. Eight National Pan-Hellenic Council (historically African-American) fraternities and sororities also hold chapters at Duke.[234] The first historically African-American Greek letter organization at Duke University was the Omega Psi Phi, Omega Zeta chapter, founded on April 12, 1974. In addition, there are seven other fraternities and sororities that are a part of the Inter-Greek Council, the multicultural Greek umbrella organization, in addition to the local group Trident Society.[235] Duke also has Selective Living Groups, or SLGs, on campus for students seeking informal residential communities often built around themes. SLGs are residential groups similar to fraternities or sororities, except they are generally co-ed and unaffiliated with any national organizations.[236] Current SLGs include Brownstone, Maxwell, The Cube, LangDorm, Round Table, Mundi, JAM!, and Wayne Manor.[237] Fraternity chapters and SLGs frequently host social events in their residential sections, which are often open to non-members.[238] Social events often feature established traditions, such as Wayne Manor's Malt Liquor Thursdays (M.L.T.), which have persisted since 1994.[239]

In the late 1990s, a new keg policy was put into effect that requires all student groups to purchase kegs through Duke Dining Services. According to administrators, the rule change was intended as a way to ensure compliance with alcohol consumption laws as well as to increase on-campus safety.[240] Some students saw the administration's increasingly strict policies as an attempt to alter social life at Duke.[241] As a result, off-campus parties at rented houses became more frequent in subsequent years as a way to avoid Duke policies. Many of these houses were situated in the midst of family neighborhoods, prompting residents to complain about excessive noise and other violations. Police have responded by breaking up parties at several houses, handing out citations, and occasionally arresting party-goers.[242] In the mid-to-late 2000s, the administration made a concerted effort to help students re-establish a robust, on-campus social life and has worked with numerous student groups, especially Duke University Union, to feature a wide array of events and activities. In March 2006, the university purchased 15 houses in the Trinity Park area that Duke students had typically rented and subsequently sold them to individual families in an effort to encourage renovations to the properties and to reduce off-campus partying in the midst of residential neighborhoods.[243][244]

Duke athletics, particularly men's basketball, traditionally serves as a significant component of student life. Duke's students have been recognized as some of the most creative and original fans in all of collegiate athletics.[245] Students, often referred to as Cameron Crazies, show their support of the men's basketball team by "tenting" for home games against key Atlantic Coast Conference opponents, especially rival University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC).[246] Because tickets to all varsity sports are free to students, they line up for hours before each game, often spending the night on the sidewalk. For a mid-February game against UNC, some of the most eager students might even begin tenting before spring classes begin.[247] The total number of participating tents is capped at 100 (each tent can have up to 12 occupants), though interest is such that it could exceed that number if space permitted.[248] Tenting involves setting up and inhabiting a tent on the grass near Cameron Indoor Stadium, an area known as Krzyzewskiville, or K-Ville for short. There are different categories of tenting based on the length of time and number of people who must be in the tent.[248] At night, K-Ville often turns into the scene of a party or occasional concert. Duke also has a "bench-burning" tradition that involves bonfires after certain basketball victories.[249]

Activities

[edit]Student organizations

[edit]

More than 400 student clubs and organizations operate on Duke's campus.[250] These include numerous student government, special interest, and service organizations.[251] Duke Student Government (DSG) charters and provides most of the funding for other student groups and represents students' interests when dealing with the administration.[252] Duke University Union (DUU) is the school's primary programming organization, serving a center of social, cultural, intellectual and recreational life.[253] There are a number of student-run businesses operating on campus, including Campus Enterprises, which offer students real-world business experience. Cultural groups are provided funding directly from the university via the Multicultural Center as well as other institutional funding sources. One of the most popular activities on campus is competing in sports. Duke has 37 sports clubs, and several intramural teams that are officially recognized. Performance groups such as Duke Players; Hoof 'n' Horn, the country's second-oldest student-run musical theater organization; a cappella groups; student bands; and other theater organizations are also prominent on campus.[254] As of the 2016–17 school year, there are seven a cappella groups recognized by Duke University A Cappella Council: Deja Blue, Lady Blue, Out of the Blue, the Pitchforks, Rhythm & Blue, Something Borrowed Something Blue, and Speak of the Devil.[255] Duke University mock trial team won the national championship in 2012.[256] Duke University Student Dining Advisory Committee provides guidance to the administration on issues regarding student dining, life, and restaurant choices.

Cultural groups on campus include the Asian Students Association, ASEAN (Alliance of Southeast Asian Nations), Blue Devils United (the student lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender group), Black Student Alliance, Diya (South Asian Association), International Association/International Council, Jewish Life at Duke, KUSA (Korean Undergraduate Student Association), Mi Gente (Latino Student Association), LangDorm, LASO (Latin American Student Organization), Muslim Student Association, Native American Student Coalition, Newman Catholic Student Center, and Students of the Caribbean.[250][257]

Duke's chapter of Students Supporting Israel (SSI), an international pro-Israel movement, was denied recognition by the Duke Student Government (DSG) in November 2021.[258] The incident attracted national media attention, with organizations such as The Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law[259] and the Zionist Organization of America[260] advocating on behalf of Duke SSI after Duke's chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine challenged its existence. The Brandeis Center sent a letter to President Price alleging that the derecognition of Duke SSI constituted discrimination against a Jewish student organization.[261] Duke SSI was officially recognized as a student organization in February 2022 after the student government reconsidered the group's application.[262]

Civic engagement

[edit]

More than 75 percent of Duke students pursue service-learning opportunities in Durham and around the world through DukeEngage and other programs that advance the university's mission of "knowledge in service to society." Launched in 2007, DukeEngage provides full funding for select Duke undergraduates who wish to pursue an immersive summer of service in partnership with a U.S. or international community. As of summer 2013, more than 2,400 Duke students had volunteered through DukeEngage in 75 nations on six continents. Duke students have created more than 30 service organizations in Durham and the surrounding area. Examples include a weeklong camp for children of cancer patients (Camp Kesem) and a group that promotes awareness about sexual health, rape prevention, alcohol and drug use, and eating disorders (Healthy Devils). Duke-Durham Neighborhood Partnership, started by the Office of Community Affairs in 1996, attempts to address major concerns of local residents and schools by leveraging university resources.[263] Another community project, "Scholarship with a Civic Mission", is a joint program between the Hart Leadership Program and the Kenan Institute for Ethics.[264] Another program includes Project CHILD, a tutoring program involving 80 first-year volunteers; and an after-school program for at-risk students in Durham that was started with a $2.25 million grant from the Kellogg Foundation in 2002.[265] Two prominent civic engagement pre-orientation programs also exist for incoming freshmen: Project CHANGE and Project BUILD. Project CHANGE is a free weeklong program co-sponsored by the Kenan Institute for Ethics and Duke Women's Center with the focus on ethical leadership and social change in the Durham community; students are challenged in a variety of ways and work closely with local non-profits.[266] Project BUILD is a freshman volunteering group that dedicates 3,300 hours of service to a variety of projects such as schools, Habitat for Humanity, food banks, substance rehabilitation centers, homeless shelters. Some courses at Duke incorporate service as part of the curriculum to augment material learned in class such as in psychology or education courses (known as service learning courses).[267]

Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC)

[edit]

Duke's Reserve Officers' Training Corps has three wings: Army, Air Force & Space Force, and Navy & Marines. Duke University Army Reserve Officers' Training Corps (AROTC) students who receive a scholarship or enter the Army ROTC Advanced Course (Junior and Senior Year) must agree to complete an eight-year period of service with the US Army.

Duke's Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (AFROTC) Detachment 585 includes members from Duke University and North Carolina Central University.[268] Established in 1951, Detachment 585 is located at Trent Hall on Duke University campus. This program is designed to provide men and women the opportunity to become military officers while earning a degree. Upon graduation, students who have successfully completed this program will receive a commission in either the US Air Force or US Space Force.[268]

Student media

[edit]The Chronicle, Duke's independent undergraduate daily newspaper, has been continually published since 1905.[269] Its editors are responsible for selecting the term "Blue Devil". The newspaper won Best in Show in the tabloid division at the 2005 Associated Collegiate Press National College Media Convention.[270] Cable 13, established in 1976, is Duke's student-run television station. It is a popular activity for students interested in film production and media.[271] WXDU, licensed in 1983, is the university's nationally recognized, noncommercial FM radio station, operated by student and community volunteers.[272][273]

The Chanticleer is Duke University's undergraduate yearbook. It was founded while the institution was still Trinity College in 1911, and was first published in 1912. The yearbook been published continually ever since, apart from 1918 when many students left for military service in World War I. In 1919 the yearbook was titled The Victory to mark the war's end.[274]

Alumni

[edit]Duke's active alumni base of more than 145,000 devote themselves to the university through organizations and events such as the annual Reunion Weekend and Homecoming.[275] There are 75 Duke clubs in the U.S. and 38 such international clubs.[276] For the 2008–09 fiscal year, Duke tied for third in alumni giving rate among U.S. colleges and universities according to U.S. News & World Report.[277] Based on statistics compiled by PayScale in 2011, Duke alumni rank seventh in mid-career median salary among all U.S. colleges and universities.[278]

-

37th President of the United States Richard Nixon (J.D. 1937)

-

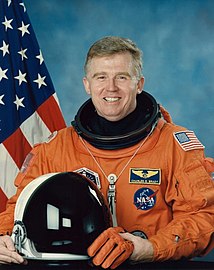

Astronaut Charles E. Brady, Jr. (M.D. 1975)

-

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey (M.A. 1984)

-

Philanthropist Melinda French Gates (A.B. 1986, M.B.A. 1987)

-

Prince of Jordan Hashim bin Al Hussein (X)

-

Seven-time NBA All-Star, NBA Champion Kyrie Irving (2010–2011)

-

7x NBA All-Star, 2X NCAA Champion, Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame member Grant Hill (B.A. 1994)

-

Former President of Chile Ricardo Lagos (Ph.D. 1966)

-

American billionaire, owner of Hyatt Hotels and TransUnion Corporation, and 43rd Governor of Illinois J. B. Pritzker (A.B. 1987)

-

Indian billionaire healthcare entrepreneur Shivinder Mohan Singh (M.B.A. 2000)

-

Former Chairman and CEO of General Motors Corporation G. Richard Wagoner, Jr. (A.B. 1975)

Duke Alumni Association

[edit]Duke Alumni Association (DAA) is an alumni association automatically available to all Duke graduates. Benefits include alumni events, a global network of regional DAA alumni chapters, educational and travel opportunities and communications such as The Blue Note, social media and Duke Magazine. It provides access to Duke Lemur Center, Nasher Museum of Art, Duke Rec Centers and other campus facilities.[279]

Athletics

[edit]

Teams for then Trinity College were known originally as the Trinity Eleven, the Blue and White or the Methodists. William H. Lander, as editor-in-chief, and Mike Bradshaw, as managing editor, of the Trinity Chronicle began the academic year 1922–23 referring to the athletic teams as the Blue Devils. The Chronicle staff continued its use and through repetition, Blue Devils eventually caught on.[280]

Duke University Athletic Association chairs 27 sports and more than 650 student-athletes. The Blue Devils are members of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I level, the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) and the Atlantic Coast Conference. Men's sports include baseball, basketball, cross country, fencing, football, golf, lacrosse, soccer, swimming & diving, tennis, track & field, and wrestling; women's sports include basketball, cross country, fencing, field hockey, golf, lacrosse, rowing, soccer, softball, swimming & diving, tennis, track & field, and volleyball.[281]

Duke's teams have won 17 NCAA team national championships—the women's golf team has won seven (1999, 2002, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2014 and 2019), the men's basketball team has won five (1991, 1992, 2001, 2010, and 2015), the men's lacrosse team has won three (2010, 2013, and 2014), and the men's soccer (1986) and women's tennis (2009) teams have won one each.[282] Duke consistently ranks among the top in the National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics (NACDA) Directors' Cup, an overall measure of an institution's athletic success. For Division I in 2015, Duke finished 20th overall and fifth in the ACC. The Blue Devils have finished within the top 10 six times since the inception of the Cup in 1993–94. Also, Athletic Director Kevin White earned multiple awards in 2014, including the National Football Foundation's John L. Toner Award.[283]

On the academic front, nine Duke varsity athletics programs registered a perfect 1,000 score in the NCAA's multi-year Academic Progress Report (APR) released in April 2016.[284]

Men's basketball

[edit]

Duke's men's basketball team is one of the nation's most successful basketball programs.[285][286] The team's success has been particularly outstanding over the past 30 years under coach Mike Krzyzewski (often simply called "Coach K").[287] The Blue Devils are the only team to win five national championships since the NCAA Tournament field was expanded to 64 teams in 1985, 11 Final Fours in the past 25 years, and eight of nine ACC tournament championships from 1999 to 2006. Coach K has also coached the USA men's national basketball team since 2006 and led the team to Olympic golds in 2008, 2012, and 2016. His teams also won World Championship gold in 2010 and 2014. Overall, 32 Duke players[288] have been selected in the first round of the NBA draft in the Coach K era. More than 50 Duke players have been selected in the NBA draft.[288]

Football

[edit]The Blue Devils have won seven ACC Football Championships, have had ten players honored as ACC Player of the Year (the most in the ACC),[289] and have had three Pro Football Hall of Famers come through the program (second in the ACC to only Miami's four). The Blue Devils have produced 11 College Football Hall of Famers, which is tied for the second most in the ACC. Duke has also won 18 total conference championships (7 ACC, 9 Southern Conference, and 1 Big Five Conference). That total is tied with Clemson for the highest in the ACC.[290]

The most famous Duke football season came in 1938,[291] when Wallace Wade coached the "Iron Dukes" that shut out all regular season opponents; only three teams in history can claim such a feat.[292] That same year, Duke made their first Rose Bowl appearance, where they lost, 7–3, when USC scored a touchdown in the final minute of the game.[291] Wade's Blue Devils lost another Rose Bowl to Oregon State in 1942, this one held at Duke's home stadium due to the attack on Pearl Harbor, which resulted in the fear that a large gathering on the West Coast might be in range of Japanese aircraft carriers.[293] The football program proved successful in the 1950s and 1960s, winning six of the first ten ACC football championships from 1953 to 1962 under coach Bill Murray; the Blue Devils would not win the ACC championship again until 1989 under coach Steve Spurrier.[294]

David Cutcliffe was brought in prior to the 2008 season, and amassed more wins in his first season than the previous three years combined. The 2009 team won 5 of 12 games, and was eliminated from bowl contention in the next-to-last game of the season.[295] Mike MacIntyre, the defensive coordinator, was named 2009 Assistant Coach of the Year by the American Football Coaches Association (AFCA).[296]

While the football team has struggled at times on the field, the graduation rate of its players is consistently among the highest among Division I FBS schools. Duke's high graduation rates have earned it more AFCA Academic Achievement Awards than any other institution.[297]

In 2012, Duke football team made its first bowl game appearance since 1994[298] with a win over arch-rival North Carolina, a bowl which they would lose to the Cincinnati Bearcats in the by a score of 48–34.[299]

2013 marked the beginning of the Blue Devils' recent but relative success, having a breakout 10–2, 6–2 (ACC)[300] season while claiming the title of Coastal Division Champions.[301] Duke would go on to play the Florida State Seminoles in the ACC Championship game where they would lose to the national champions 45–7.[302] Duke received an invite to the Chick-fil-a Peach Bowl that same year in which they took on the Texas A&M Aggies led by college football legend Johnny Manziel, losing by a score of 52–48.[303]

For the 2014 season, Duke finished 9–3, 5–3 (ACC) and earned a trip to the Sun Bowl,[304] where the Blue Devils lost to the Pac-12's Arizona State 36–31. In 2015, the Detroit Lions drafted Duke offensive guard Laken Tomlinson[305] and the Washington Redskins drafted wide receiver Jamison Crowder.[306] In 2019, Duke quarterback Daniel Jones was drafted sixth overall by the New York Giants.[307]

Track and field

[edit]In 2003, Norm Ogilvie was promoted to Director of Track and Field, and has led athletes to over 60 individual ACC championships, and 81 All-America selections, along with most of the track and field records being broken during his tenure.[308] A new facility, the Morris Williams Track and Field Stadium, opened in 2015.[309]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

References

[edit]- ^ a b King, William E. "Shield, Seal and Motto". Duke University Archives. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ "About – Duke Divinity School". Duke Divinity School. Archived from the original on July 2, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ "Duke University's Relation to the Methodist Church: the basics". Duke University. 2002. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

Duke University has historical, formal, on-going, and symbolic ties with Methodism, but is an independent and non-sectarian institution ... Duke would not be the institution it is today without its ties to the Methodist Church. However, the Methodist Church does not own or direct the University. Duke is and has developed as a private nonprofit corporation which is owned and governed by an autonomous and self-perpetuating Board of Trustees

- ^ a b As of September 27, 2021. Duke University's Endowment Sees Record 56% Gain in Latest Year (Report). Bloomberg. September 27, 2021. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ "About the Duke Endowment". The Duke Endowment. January 9, 2009. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Duke Facts". Duke University. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ "A First Day as President-Elect is a Memorable One". December 3, 2016. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ "IPEDS-Duke University". Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ "Color Palette". Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c King, William E. "Duke University: A Brief Narrative History". Duke University Archives. Archived from the original on March 12, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Sparks, Evan. "Duke of Carolina". Philanthropy Roundtable. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ Loftus, Sarah (July 15, 2019). "Duke Marine Lab Opens Doors to Visitors". Coastal Review. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ McGuinness, William (January 2, 2013). "Duke Readies For China Campus Amid Controversy". HuffPost. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ "Duke's Research Expenditures Exceed $1.2 Billion in Latest Federal Data". February 2, 2021. Archived from the original on July 24, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Elkins, Kathleen. "Billionaire Universities". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c "A Chronology of Significant Events in Duke University's History". Duke University Archives. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Pyatt, Tim (November–December 2006). "Retrospective: Selections from University Archives". Duke Magazine. 92 (6). Duke Office of Alumni Affairs. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "History of The Congregation At Duke University Chapel". The Congregation at Duke University Chapel. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ Duke University Chapel – History Archived May 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Friends of Duke Chapel. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ^ King, William E. (1997). "Washington Duke and the Education of Women". University Archives. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Twu, Marianne. "Slavery and Segregation". humanrights.fhi.duke.edu. Duke University. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Witz, Billy (January 1, 2021). "In Pasadena, Moving the Rose Bowl Makes For Unusual Rancor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "Navy V-12 Program". Durham, North Carolina: Duke University. 2011. Archived from the original on March 5, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ Twu, Marianne (2010). "Slavery and Segregation". Duke Human Rights Center. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ "Celebrating the Past, Charting the Future: Commemorating 50 Years of Black Students at Duke University". Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ "The Road to Desegregation". Duke University. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ Duke Annual Report 2000/2001-Interdisciplinary Archived July 24, 2012, at archive.today. Duke University Annual Report, 2001. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ Rogalski, Jim. Breaking the Barrier: A History of African-Americans at Duke University School of Medicine. Inside DUMC, February 20, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ Mock, Geoffrey. Duke's Black Faculty Initiative Reaches Goal Early. Duke University Office of News and Communication, November 21, 2002. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ "Duke Campaign Raises $3.85 Billion to Empower Service to Society". Duke Today. Duke University. August 9, 2017. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ Academic, Cultural and Research Centers Archived March 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Duke University Admissions. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ Phillip, Abby (June 17, 2014). "This Duke dorm is no longer named after a white supremacist former governor". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Duke University Removes Robert E. Lee Statue From Chapel Entrance". NPR. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Duke University removes contentious Confederate statue after vandalism". Reuters. August 19, 2017. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Drew, Jonathan (August 19, 2017). "Duke University removes damaged Robert E. Lee statue". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "Class of 2024 international students who face travel restrictions can spend Fall semester at DKU". The Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ "North Carolina: Woman in Duke case guilty in killing". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 22, 2013. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ Yamato, Jen (March 12, 2016). "The stripper who cried 'rape': Revisiting the Duke lacrosse case ten years later". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2019.