Greek alphabet: Difference between revisions

Kwamikagami (talk | contribs) |

→Antiquity: rewording, +Greco-Iberian |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!--this article has used the BC/AD convention since 2001--> |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}}{{pp-move-indef}} |

{{pp-semi-indef}}{{pp-move-indef}} |

||

{{Infobox writing system |

{{Infobox writing system |

||

| Line 15: | Line 14: | ||

|note = none |

|note = none |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{SpecialChars}} |

|||

{{Table Greekletters|letter=}} |

|||

The '''Greek alphabet''' is the script that has been used to write the [[Greek language]] since the 8th century BC.{{sfn|Cook|1987|p=9}} It was derived from the earlier [[Phoenician alphabet]], and was in turn the ancestor of numerous other European and Middle Eastern scripts, including [[Cyrillic script|Cyrillic]] and [[Latin script|Latin]].{{sfn|Coulmas|1996|p=}} While its main use has always been to write the Greek language, both in its ancient and its modern forms, its letters are today also used widely as technical symbols and labels in many domains of mathematics, science and other fields. |

|||

[[Image:Dipylon Inscription.JPG|thumb|[[Dipylon inscription]], one of the oldest known samples of the use of the Greek alphabet, ca. 740 BC]] |

|||

In its classical and modern form the alphabet has 24 letters, ordered from alpha to omega. Like Latin and Cyrillic, Greek (as written in the [[modern era]]) is a [[bicameral script]], distinguishing between upper case and lower case forms for each letter. The letter [[sigma]] 〈Σ〉 has two different lowercase forms in standard modern usage, 〈σ〉 and 〈ς〉. The form 〈ς〉 is used in word-final position,<ref name="nicholas_finalsigma">In some 19th-century typesetting, 〈ς〉 was also used word-medially at the end of a [[compound (linguistics)|compound]] morpheme, e.g. "δυςκατανοήτων", marking the morpheme boundary between "δυς-κατανοήτων" ('difficult to understand'); modern standard practice is to spell "δυσκατανοήτων" with a non-final sigma. {{cite web|first=Nick|last=Nicholas|year=2004|title=Sigma: final versus non-final|url=http://www.tlg.uci.edu/~opoudjis/dist/sigma.html|accessdate=2012-07-15}}</ref> 〈σ〉 elsewhere. |

|||

The '''Greek alphabet''' is the script that has been used to write the [[Greek language]] since at least 730 BC (the 8th century BC).{{sfn|Cook|1987|p=9}} The alphabet in its classical and modern form consists of 24 letters ordered in sequence from [[alpha]] to [[omega]]. The Greek alphabet was derived from the earlier [[Phoenician alphabet]], from which it differs by being the first alphabet that provides a full representation of one written symbol per sound for both [[vowel]]s and [[consonant]]s. The Greek alphabet in turn is the ancestor of numerous other European and Middle Eastern scripts that follow the same structural principle, among them [[Cyrillic script|Cyrillic]] and [[Latin script|Latin]].{{sfn|Coulmas|1996|p=}} |

|||

Sound values and conventional transcriptions for some of the letters differ between [[Ancient Greek]] and [[Modern Greek]] usage, owing to phonological changes in the language. |

|||

The Greek alphabet reached its classical form around 400 BC, with some details, including the use of [[diacritic]] marks, becoming fixed only during the following centuries of the [[Hellenistic period|Hellenistic]] and [[Roman period]]. The sequence of letters has remained unchanged since then up to the present day, although the sound values of individual letters have changed considerably due to phonological changes between [[Ancient Greek|ancient]] and [[modern Greek]]. While it was originally written with only a single, [[majuscule]] form for each letter, the Greek alphabet developed a second set of letter forms, the [[Minuscule Greek|minuscule]] letters, during the Middle Ages, resulting in the modern system of [[letter case|uppercase and lowercase]] forms. |

|||

In traditional ("polytonic") Greek orthography, vowel letters can be combined with any of numerous combinations of [[Greek diacritics|diacritics]] (accent marks and so-called "breathing" marks). In common present-day usage for Modern Greek since the 1980s, this system has been simplified to a so-called "monotonic" convention. |

|||

In addition to being used for writing Greek, both ancient and modern, the letters of the Greek alphabet are today used as technical symbols and labels in many domains of mathematics, science and other fields. |

|||

<table><tr><td><!-- outer table --> |

|||

== Description == |

|||

{|class="wikitable" style="float:left;" |

|||

In its classical and modern form, the Greek alphabet contains 24 letters. They are named, in order, as follows: [[alpha]], [[beta]], [[gamma]], [[delta (letter)|delta]], [[epsilon]], [[zeta]], [[eta]], [[theta]], [[iota]], [[kappa]], [[lambda]], [[Mu (letter)|mu]], [[Nu (letter)|nu]], [[Xi (letter)|xi]], [[omicron]], [[pi]], [[rho]], [[sigma]], [[tau]], [[upsilon]], [[phi]], [[chi (letter)|chi]], [[psi (letter)|psi]], [[omega]]. The 24 capital letters (upper-case symbols) are: Α, Β, Γ, Δ, Ε, Ζ, Η, Θ, Ι, Κ, Λ, Μ, Ν, Ξ, Ο, Π, Ρ, Σ, Τ, Υ, Φ, Χ, Ψ, Ω. The 24 [[Greek minuscule|minuscule]] symbols (lower-case letters) of the Greek alphabet (in order) are: α, β, γ, δ, ε, ζ, η, θ, ι, κ, λ, μ, ν, ξ, ο, π, ρ, σ (ς), τ, υ, φ, χ, ψ, ω. A system of [[diacritics]] on some letters was added during the [[Hellenistic civilization|Hellenistic period]]. Today the diacritics exist in two orthographic variants: the traditional ("polytonic") system and a simplified ("monotonic") one that has been in official use for Modern Greek since the 1980s. |

|||

|- |

|||

!rowspan="2"|Letter |

|||

!rowspan="2"|Name |

|||

!colspan="2"|Sound value |

|||

|- |

|||

!Ancient<ref name="woodard_2008_15">{{harvnb|Woodard|2008|pp=15–17}}</ref> |

|||

!Modern<ref name="holton_1998_31">{{harvnb|Holton|Mackridge|Philippaki-Warburton|1998|p=31}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Α α |

|||

|[[alpha]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|a}} {{IPAblink|aː}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|a}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Β β |

|||

|[[beta]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|b}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|v}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Γ γ |

|||

|[[gamma|gamma]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|ɡ}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|ɣ}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Δ δ |

|||

|[[delta (letter)|delta]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|d}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|ð}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ε ε |

|||

|[[epsilon]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|e}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|e}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ζ ζ |

|||

|[[zeta]] |

|||

|{{IPA|[zd]}} (or {{IPA|[dz]}}<ref name="hinge">{{harvnb|Hinge|2001|pp=212–234}}</ref>) |

|||

|{{IPAblink|z}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Η η |

|||

|[[eta]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|ɛː}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|e}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Θ θ |

|||

|[[theta]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|tʰ}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|θ}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ι ι |

|||

|[[iota]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|i}} {{IPAblink|iː}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|i}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Κ κ |

|||

|[[kappa]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|k}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|k}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Λ λ |

|||

|[[lambda]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|l}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|l}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Μ μ |

|||

|[[mu (letter)|mu]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|m}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|m}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|}</td><td> |

|||

{|class="wikitable" style="float:left;" |

|||

|- |

|||

!rowspan="2"|Letter |

|||

!rowspan="2"|Name |

|||

!colspan="2"|Sound value |

|||

|- |

|||

!Ancient |

|||

!Modern |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ν ν |

|||

|[[nu (letter)|nu]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|n}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|n}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ξ ξ |

|||

|[[xi (letter)|xi]] |

|||

|{{IPA|/ks/}} |

|||

|{{IPA|/ks/}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ο ο |

|||

|[[omicron]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|o}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|o}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Π π |

|||

|[[pi (letter)|pi]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|p}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|p}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ρ ρ |

|||

|[[rho]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|r}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|r}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Σ σς |

|||

|[[sigma]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|s}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|s}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Τ τ |

|||

|[[tau]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|t}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|t}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Υ υ |

|||

|[[upsilon]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|y}} {{IPAblink|yː}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|i}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Φ φ |

|||

|[[phi]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|pʰ}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|f}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Χ χ |

|||

|[[chi (letter)|chi]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|kʰ}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|x}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ψ ψ |

|||

|[[psi (letter)|psi]] |

|||

|{{IPA|/ps/}} |

|||

|{{IPA|/ps/}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="font-size:120%;"| Ω ω |

|||

|[[omega]] |

|||

|{{IPAblink|ɔː}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|o}} |

|||

|} |

|||

</td></tr></table><!-- outer table --> |

|||

<br style="clear:left;" /> |

|||

</div> |

|||

== |

==Letters== |

||

=== Sound values === |

|||

{{Main|History of the Greek alphabet|Archaic Greek alphabets}} |

|||

{{main|Greek orthography}} |

|||

[[Image:Griechisches Alphabet Varianten.png|thumb|200px|Variations of ancient Greek alphabets]] |

|||

Both in Ancient and Modern Greek, the letters of the Greek alphabet have fairly stable and consistent symbol-to-sound mappings, making pronunciation of words largely predictable. Ancient Greek spelling was generally near-phonemic. For a number of letters, sound values differ considerably between Ancient and Modern Greek, because their pronunciation has followed a set of systematic phonological shifts that affected the language in its post-classical stages.<ref name="horrocks_231">{{harvnb|Horrocks|2008|pp=231–250}}</ref> |

|||

Among consonant letters, all letters that denoted voiced plosive consonants (/b, d, g/) and aspirated plosives (/pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/) in Ancient Greek stand for corresponding fricative sounds in Modern Greek. The correspondences are as follows: |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

!rowspan="2"| |

|||

!colspan="3"|Former voiced plosives |

|||

!colspan="3"|Former aspirates |

|||

|- |

|||

!Letter |

|||

!Ancient |

|||

!Modern |

|||

!Letter |

|||

!Ancient |

|||

!Modern |

|||

|- |

|||

|Labial |

|||

|Β β |

|||

|{{IPAslink|b}} |

|||

|{{IPAslink|v}} |

|||

|Φ φ |

|||

|{{IPAslink|pʰ}} |

|||

|{{IPAslink|f}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|Dental |

|||

|Δ δ |

|||

|{{IPAslink|d}} |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ð}} |

|||

|Θ θ |

|||

|{{IPAslink|tʰ}} |

|||

|{{IPAslink|θ}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|Coronal |

|||

|Γ γ |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ɡ}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|ɣ}} ~ {{IPAblink|j}} |

|||

|Χ χ |

|||

|{{IPAslink|kʰ}} |

|||

|{{IPAblink|x}} ~ {{IPAblink|ç}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

Among the vowel symbols, Modern Greek sound values reflect the fact that the vowel system of post-classical Greek was radically simplified, merging multiple formerly distinct vowel phonemes into a much smaller number. This leads to several groups of vowel letters denoting identical sounds today. Modern Greek orthography remains true to the historical spellings in most of these cases. As a consequence, the spellings of words in Modern Greek are often not predictable from the pronunciation alone, while the reverse mapping, from spelling to pronunciation, is usually regular and predictable. |

|||

The following vowel letters and digraphs are involved in the mergers: |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

!letter!!ancient!!modern!!letter!!ancient!!modern |

|||

|- |

|||

| Η η || {{IPAlink|ɛː}} ||rowspan="5"| > {{IPAlink|i}} || Ω ω || {{IPAlink|ɔː}} ||rowspan="2"| > {{IPAlink|o}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Ι ι || {{IPAlink|i}}({{IPA|ː}}) || Ο ο || {{IPAlink|o}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| ΕΙ ει || {{IPA|ei}} || Ε ε || {{IPAlink|e}} ||rowspan="2"| > {{IPAlink|e}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Υ υ || {{IPAlink|u}}({{IPA|ː}}) > {{IPAlink|y}} || AΙ aι || {{IPA|ai}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| ΟΙ οι || {{IPA|oi}} > {{IPAlink|y}} ||colspan="3"| |

|||

|} |

|||

Modern Greek speakers typically use the same, modern, sound-symbol mappings in reading Greek of all historical stages. In other countries, students of Ancient Greek may use a variety of [[Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in teaching|conventional approximations]] of the historical sound system in pronouncing Ancient Greek. |

|||

=== Digraphs and letter combinations === |

|||

Several letters combinations have special conventional sound values different from those of their single components. Among them are several [[digraph]]s of vowel letters that formerly represented [[diphthong]]s but are now monophthongized. In addition to the three mentioned above (〈ει, αι, οι〉) there is also 〈ου〉 = /u/. The Ancient Greek diphthongs 〈ευ〉 and 〈αυ〉 are pronounced [ev] and [av] respectively in Modern Greek ([ef, af] in devoicing environments). The Modern Greek consonant combinations 〈μπ〉 and 〈ντ〉 stand for [b] and [d] (or [mb] and [nd]) respectively; 〈τζ〉 stands for [dz]. In addition, both in Ancient and Modern Greek, the letter 〈γ〉, before another [[velar consonant]], stands for the [[velar nasal]] [ŋ]; thus 〈γγ〉 and 〈γκ〉 are pronounced like English 〈ng〉. |

|||

=== Diacritics === |

|||

{{main|Greek diacritics}} |

|||

In the [[polytonic orthography]] traditionally used for ancient Greek, the stressed vowel of each words carries one of three accent marks: either the [[acute accent]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|ά}}}}), the [[grave accent]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|ὰ}}}}), or the [[circumflex accent]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|α̃ }}}} or {{big|{{lang|grc|α̑}}}}). These signs were originally designed to mark different forms of the phonological [[pitch accent]] in Ancient Greek. By the time their use became conventional and obligatory in Greek writing, in late antiquity, pitch accent was evolving into a single [[Stress (linguistics)|stress accent]], and thus the three signs have not corresponded to a phonological distinction in actual speech ever since. In addition to the accent marks, every word-initial vowel must carry either of two so-called "breathing marks": the [[Spiritus asper|rough breathing]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|ἁ}}}}), marking an {{IPA|/h/}} sound at the beginning of a word, or the [[Spiritus lenis|smooth breathing]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|ἀ}}}}), marking its absence. The letter rho (ρ), although not a vowel, also carries a rough breathing in word-initial position. |

|||

The vowel letters 〈α, η, ω〉 carry an additional diacritic in certain words, the so-called [[iota subscript]], which has the shape of a small vertical stroke or a miniature 〈ι〉 below the letter. This iota represents the former offglide of what were originally long diphthongs, 〈ᾱι, ηι, ωι〉 (i.e. /aːi, ɛːi, ɔːi/), which became monophthongized during antiquity. |

|||

Another diacritic used in Greek is the [[Double dot (diacritic)|diaeresis]] ({{big|{{lang|grc|¨}}}}), indicating a [[Hiatus (linguistics)|hiatus]]. |

|||

In 1982, a new, simplified orthography, known as "monotonic", was adopted for official use in Modern Greek by the Greek state. It uses only a single accent mark, the acute (also known in this context as ''tonos'', i.e. simply "accent"), marking the stressed syllable of polysyllabic words, and occasionally the diaeresis to distinguish diphthongal from digraph readings in pairs of vowel letters. The polytonic system is still conventionally used for writing Ancient Greek, while in some book printing and generally in the usage of conservative writers it can still also be found in use for Modern Greek. |

|||

=== Romanization === |

|||

{{main|Romanization of Greek}} |

|||

There are many different methods of rendering Greek text or Greek names in the Latin script. The form in which classical Greek names are conventionally rendered in English goes back to the way Greek loanwords were incorporated into Latin in antiquity. In this system, 〈κ〉 is replaced with 〈c〉, the diphthongs 〈αι〉 and 〈οι〉 are rendered as 〈ae〉 and 〈oe〉 (or 〈æ,œ〉) respectively; and 〈ει〉 and 〈ου〉 are simplified to 〈i〉 and 〈u〉 respectively. In modern scholarly transliteration of Ancient Greek, 〈κ〉 will instead be rendered as 〈k〉, and the vowel combinations 〈αι, οι, ει, ου〉 as 〈ai, oi, ei, ou〉 respectively. The letters 〈θ〉 and 〈φ〉 are generally rendered as 〈th〉 and 〈ph〉; 〈χ〉 as either 〈ch〉 or 〈kh〉; and word-initial 〈ρ〉 as 〈rh〉. |

|||

For Modern Greek, there are multiple different transcription conventions. They differ widely, depending on their purpose, on how close they stay to the conventional letter correspondences of Ancient Greek–based transcription systems, and to what degree they attempt either an exact letter-by-letter [[transliteration]] or rather a phonetically based transcription. Standardized formal transcription systems have been defined by the [[International Organization for Standardization]] (as [[ISO 843]]),<ref>{{cite web|title=ISO 843:1997 (Conversion of Greek characters into Latin characters)|author=ISO|authorlink=International Organization for Standardization|year=2010|accessdate=2012-07-15}}</ref> by the [[United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names]],<ref>{{cite web|title=Greek|url=http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/rom1_el.htm|author=UNGEGN Working Group on Romanization Systems|accessdate=2012-07-15|year=2003}}</ref> by the [[ALA-LC romanization|Library of Congress]] ,<ref>{{cite web|title=Greek (ALA-LC Romanization Tables)|year=2010|accessdate=2012-07-15}}</ref> and others. |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{Main|History of the Greek alphabet}} |

|||

=== Origins === |

|||

[[Image:Dipylon Inscription.JPG|thumb|[[Dipylon inscription]], one of the oldest known samples of the use of the Greek alphabet, ca. 740 BC]] |

|||

The Greek alphabet emerged in the late 9th century BC or early 8th century BC{{sfn|Johnston|2003|p=}} Another, unrelated writing system, [[Linear B]], had been in use to write the Greek language during the earlier [[Mycenean Greece|Mycenean]] period, but the two systems are separated from each other by a hiatus of several centuries, the so-called [[Greek Dark Ages]]. The Greeks adopted the alphabet from the earlier [[Phoenician alphabet]], a member of the family of closely related [[Abjad|West Semitic scripts]]. The most notable change made in adapting the Phoenician system to Greek was the introduction of vowel letters. According to a definition used by some modern authors, this feature makes Greek the first "alphabet" in the narrow sense,{{sfn|Coulmas|1996|p=}} as distinguished from the purely consonantal alphabets of the Semitic type, which according to this terminology are called "abjads".{{sfn|Daniels|Bright|1996|p=4}} |

The Greek alphabet emerged in the late 9th century BC or early 8th century BC{{sfn|Johnston|2003|p=}} Another, unrelated writing system, [[Linear B]], had been in use to write the Greek language during the earlier [[Mycenean Greece|Mycenean]] period, but the two systems are separated from each other by a hiatus of several centuries, the so-called [[Greek Dark Ages]]. The Greeks adopted the alphabet from the earlier [[Phoenician alphabet]], a member of the family of closely related [[Abjad|West Semitic scripts]]. The most notable change made in adapting the Phoenician system to Greek was the introduction of vowel letters. According to a definition used by some modern authors, this feature makes Greek the first "alphabet" in the narrow sense,{{sfn|Coulmas|1996|p=}} as distinguished from the purely consonantal alphabets of the Semitic type, which according to this terminology are called "abjads".{{sfn|Daniels|Bright|1996|p=4}} |

||

| Line 39: | Line 263: | ||

Greek also introduced three new consonant letters for its aspirated plosive sounds and consonant clusters: Φ (''[[Phi (letter)|phi]]'') for {{IPA|/pʰ/}}, Χ (''[[Chi (letter)|chi]]'') for {{IPA|/kʰ/}} and Ψ (''[[Psi (letter)|psi]]'') for {{IPA|/ps/}}. In western Greek variants, Χ was instead used for {{IPA|/ks/}} and Ψ for {{IPA|/kʰ/}} The origin of these letters is a matter of some debate. |

Greek also introduced three new consonant letters for its aspirated plosive sounds and consonant clusters: Φ (''[[Phi (letter)|phi]]'') for {{IPA|/pʰ/}}, Χ (''[[Chi (letter)|chi]]'') for {{IPA|/kʰ/}} and Ψ (''[[Psi (letter)|psi]]'') for {{IPA|/ps/}}. In western Greek variants, Χ was instead used for {{IPA|/ks/}} and Ψ for {{IPA|/kʰ/}} The origin of these letters is a matter of some debate. |

||

<div style="float:none;"> |

|||

Conversely, three of the original Phoenician letters dropped out of use before the alphabet took its classical shape: the letter {{Unicode|Ϻ}} (''[[San (letter)|san]]''), which had been in competition with Σ (''[[sigma]]'') denoting the same phoneme /s/; the letter {{Unicode|Ϙ}} (''[[qoppa]]''), which was redundant with Κ (''[[kappa]]'') for /k/, and Ϝ (''[[digamma]]''), whose sound value /w/ dropped out of the spoken language before or during the classical period. |

|||

{|class="wikitable" style="float:left;" |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan="3"|Phoenician |

|||

!colspan="4"|Greek |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician aleph.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[aleph (letter)|aleph]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ʔ}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Alpha 03}} |

|||

|Α |

|||

|[[alpha]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|a}}, {{IPAslink|aː}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician beth.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[beth (letter)|beth]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|b}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Beta 16}} |

|||

|Β |

|||

|[[beta]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|b}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician gimel.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[gimel (letter)|gimel]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ɡ}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Gamma archaic 1}} |

|||

|Γ |

|||

|[[gamma]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ɡ}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician daleth.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[daleth (letter)|daleth]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|d}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Delta 04}} |

|||

|Δ |

|||

|[[delta (letter)|delta]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|d}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician he.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[he (letter)|he]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|h}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Epsilon archaic}} |

|||

|Ε |

|||

|[[epsilon]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|e}}, {{IPAslink|eː}}<ref name="longepsilon">Epsilon 〈ε〉 and omicron 〈ο〉 originally could denote both short and long vowels in pre-classical archaic Greek spelling, just like other vowel letters. They were restricted to the function of short vowel signs in classical Greek, as the long vowels {{IPAslink|eː}} and {{IPAslink|oː}} came to be spelled instead with the digraphs 〈ει〉 and 〈ου〉, having phonologically merged with a corresponding pair of former diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/ respectively.</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician waw.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[waw (letter)|waw]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|w}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Digamma oblique}} |

|||

| – |

|||

|''([[digamma]])'' |

|||

|{{IPAslink|w}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician zayin.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[zayin (letter)|zayin]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|z}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Zeta archaic}} |

|||

|Ζ |

|||

|[[zeta (letter)|zeta]] |

|||

|[zd](?) |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician heth.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[heth (letter)|heth]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ħ}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Eta archaic}} |

|||

|Η |

|||

|[[eta (letter)|eta]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|h}}, {{IPAslink|ɛː}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician teth.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[teth (letter)|teth]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|tˤ}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Theta archaic}} |

|||

|Θ |

|||

|[[theta]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|tʰ}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician yodh.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[yodh (letter)|yodh]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|j}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Iota normal}} |

|||

|Ι |

|||

|[[iota]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|i}}, {{IPAslink|iː}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician kaph.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[kaph (letter)|kaph]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|k}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Kappa normal}} |

|||

|Κ |

|||

|[[kappa]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|k}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician lamedh.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[lamedh (letter)|lamedh]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|l}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Lambda 09}} |

|||

|Λ |

|||

|[[lambda]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|l}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician mem.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[mem (letter)|mem]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|m}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Mu 04}} |

|||

|Μ |

|||

|[[mu (letter)|mu]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|m}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician nun.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[nun (letter)|nun]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|n}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Nu 01}} |

|||

|Ν |

|||

|[[nu (letter)|nu]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|n}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

{|class="wikitable" style="float:left;" |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan="3"|Phoenician |

|||

!colspan="4"|Greek |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician samekh.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[samekh]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|s}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Xi archaic}} |

|||

|Ξ |

|||

|[[xi (letter)|xi]] |

|||

|{{IPA|/ks/}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician ayin.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[ayin (letter)|ʿayin]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ʕ}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Omicron 04}} |

|||

|Ο |

|||

|[[omicron]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|o}}, {{IPAslink|oː}}<ref name="longepsilon"/> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician pe.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[pe (letter)|pe]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|p}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Pi archaic}} |

|||

|Π |

|||

|[[pi (letter)|pi]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|p}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician sade.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[Tsade (letter)|ṣade]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|sˤ}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|San 02}} |

|||

| – |

|||

|''([[san (letter)|san]])'' |

|||

|{{IPAslink|s}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician qoph.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[qoph]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|q}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Koppa normal}} |

|||

| – |

|||

|''([[koppa (letter)|koppa]])'' |

|||

|{{IPAslink|k}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician res.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[resh|reš]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|r}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Rho pointed}} |

|||

|Ρ |

|||

|[[rho]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|r}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician sin.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[shin (letter)|šin]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ʃ}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Sigma normal}} |

|||

|Σ |

|||

|[[sigma]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|s}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician taw.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|[[taw]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|t}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Tau normal}} |

|||

|Τ |

|||

|[[tau (letter)|tau]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|t}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Phoenician waw.svg|x12px]] |

|||

|''([[waw (letter)|waw]])'' |

|||

|{{IPAslink|w}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Upsilon normal}} |

|||

|Υ |

|||

|[[upsilon]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|u}}, {{IPAslink|uː}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|colspan="3"| – |

|||

|{{GrGl|Phi archaic}} |

|||

|Φ |

|||

|[[phi]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|pʰ}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|colspan="3"| – |

|||

|{{GrGl|Chi normal}} |

|||

|Χ |

|||

|[[chi (letter)|chi]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|kʰ}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|colspan="3"| – |

|||

|{{GrGl|Psi straight}} |

|||

|Ψ |

|||

|[[psi (letter)|psi]] |

|||

|{{IPA|/ps/}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|colspan="3"| – |

|||

|{{GrGl|Omega normal}} |

|||

|Ω |

|||

|[[omega]] |

|||

|{{IPAslink|ɔː}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

<br style="clear:left;"/> |

|||

</div> |

|||

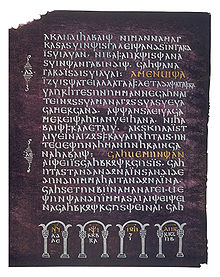

[[Image:NAMA Alphabet grec.jpg|thumb|right|Early Greek alphabet on pottery in the [[National Archaeological Museum of Athens]]]] |

|||

Three of the original Phoenician letters dropped out of use before the alphabet took its classical shape: the letter {{Unicode|Ϻ}} (''[[San (letter)|san]]''), which had been in competition with Σ (''[[sigma]]'') denoting the same phoneme /s/; the letter {{Unicode|Ϙ}} (''[[qoppa]]''), which was redundant with Κ (''[[kappa]]'') for /k/, and Ϝ (''[[digamma]]''), whose sound value /w/ dropped out of the spoken language before or during the classical period. |

|||

Greek was originally written predominantly from right to left, just like Phoenician, but scribes could freely alternate between directions. For a time, a writing style with alternating right-to-left and left-to-right lines (called ''[[boustrophedon]]'', literally "ox-turning", after the manner of an ox ploughing a field) was common, until in the classical period the left-to-right writing direction became the norm. Individual letter shapes were mirrored depending on the writing direction of the current line. |

Greek was originally written predominantly from right to left, just like Phoenician, but scribes could freely alternate between directions. For a time, a writing style with alternating right-to-left and left-to-right lines (called ''[[boustrophedon]]'', literally "ox-turning", after the manner of an ox ploughing a field) was common, until in the classical period the left-to-right writing direction became the norm. Individual letter shapes were mirrored depending on the writing direction of the current line. |

||

===Archaic variants=== |

|||

{{main|Archaic Greek alphabets}} |

|||

There were initially numerous [[Archaic Greek alphabets|local variants]] of the Greek alphabet, which differed in the use and non-use of the additional vowel and consonant symbols and several other features. A form of western Greek native to [[Euboea]], which among other things had Χ for /ks/, was transplanted to Italy by early Greek colonists, and became the ancestor of the [[Old Italic alphabet]]s and ultimately, through [[Etruscan language|Etruscan]], of the [[Latin alphabet]]. [[Athens]] used a local form of the alphabet until the 5th century BC; it lacked the letters Ξ and Ψ as well as the vowel symbols Η and Ω. The classical 24-letter alphabet that became the norm later was originally the local alphabet of [[Ionia]]; this was adopted by Athens in 403 BC under [[Eponymous archon|archon]] [[Eucleides]] and in most other parts of the Greek-speaking world during the 4th century BC. |

There were initially numerous [[Archaic Greek alphabets|local variants]] of the Greek alphabet, which differed in the use and non-use of the additional vowel and consonant symbols and several other features. A form of western Greek native to [[Euboea]], which among other things had Χ for /ks/, was transplanted to Italy by early Greek colonists, and became the ancestor of the [[Old Italic alphabet]]s and ultimately, through [[Etruscan language|Etruscan]], of the [[Latin alphabet]]. [[Athens]] used a local form of the alphabet until the 5th century BC; it lacked the letters Ξ and Ψ as well as the vowel symbols Η and Ω. The classical 24-letter alphabet that became the norm later was originally the local alphabet of [[Ionia]]; this was adopted by Athens in 403 BC under [[Eponymous archon|archon]] [[Eucleides]] and in most other parts of the Greek-speaking world during the 4th century BC. |

||

===Letter names=== |

|||

[[Image:NAMA Alphabet grec.jpg|thumb|right|Early Greek alphabet on pottery in the [[National Archaeological Museum of Athens]]]] |

|||

When the Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet, they took over not only the letter shapes and sound values, but also the names by which the sequence of the alphabet could be recited and memorized. In Phoenician, each letter name was a word that began with the sound represented by that letter; thus ''[[Aleph|ʾaleph]]'', the word for "ox", was used as the name for the glottal stop {{IPA|/ʔ/}}, ''[[Bet (letter)|bet]]'', or "house", for the {{IPA|/b/}} sound, and so on. When the letters were adopted by the Greeks, most of the Phoenician names were maintained or modified slightly to fit Greek phonology; thus, ''ʾaleph, bet, gimel'' became ''alpha, beta, gamma''. |

|||

In the [[Hellenistic civilization|Hellenistic period]], [[Aristophanes of Byzantium]] introduced [[diacritic]]s to Greek letters, to specify features of pronunciation that were being lost from the popular spoken language at around that time: the pair of [[rough breathing|rough]] and [[smooth breathing]], to denote the absence or presence of an initial /h/, and the set of three accent marks ([[acute accent|acute]], [[grave accent|grave]] and [[circumflex accent|circumflex]]) to denote distinctions of classical Greek [[pitch accent]]. During the [[Middle Ages]], the Greek scripts underwent changes paralleling those of the Latin alphabet: while the old forms were retained as a monumental script, [[Uncial script|uncial]] and eventually [[Greek minuscule|minuscule]] hands came to dominate. |

|||

The Greek names of the following letters are more or less straightforward continuations of their Phoenician antecedents. Between Ancient and Modern Greek they have remained largely unchanged, except that their pronunciation has followed regular sound changes along with other words (for instance, in the name of ''beta'', ancient /b/ regularly changed to modern /v/, and ancient /ɛː/ to modern /i/, resulting in the modern pronunciation ''vita''). The name of lambda is attested in early sources as {{lang|grc|λάβδα}} besides {{lang|grc|λάμβδα}};<ref>{{harvnb|Liddell|Scott|1940|loc=s.v. "λάβδα"}}</ref> in Modern Greek the spelling is often {{lang|el|λάμδα}}. The name of iota is sometimes rendered as {{lang|el|γιώτα}} in Modern Greek, following regular spelling conventions for the rendering of an initial glide /j/. In the tables below, the Greek names of all letters are given in their traditional polytonic spelling; in modern practice, like with all other words, they are usually spelled in the simplified monotonic system. |

|||

=== Letter names === |

|||

{{Listen|filename= Ell-AlphabitosUpload.ogg|title=Greek Alphabet.|description=(Names of the letters pronounced in Modern Greek)|format=[[Ogg]]}} |

{{Listen|filename= Ell-AlphabitosUpload.ogg|title=Greek Alphabet.|description=(Names of the letters pronounced in Modern Greek)|format=[[Ogg]]}} |

||

Each of the Phoenician letter names was a word that began with the sound represented by that letter; thus ''[[Aleph|ʾaleph]]'', the word for "ox", was adopted for the glottal stop {{IPA|/ʔ/}}, ''[[Bet (letter)|bet]]'', or "house", for the {{IPA|/b/}} sound, and so on. When the letters were adopted by the Greeks, most of the Phoenician names were maintained or modified slightly to fit Greek phonology; thus, ''ʾaleph, bet, gimel'' became ''alpha, beta, gamma''. These borrowed names had no meaning in Greek except as labels for the letters. However, a few signs that were added or modified later by the Greeks do in fact have names with meanings. For example, ''o mikron'' and ''o mega'' mean "small o" and "big o". Similarly, ''e psilon'' and ''u psilon'' mean "plain e" and "plain u", respectively. |

|||

=== Number notation === |

|||

{{main|Greek numerals}} |

|||

Greek letters were also used to write numbers. In the classical Ionian system, the first nine letters of the alphabet stood for the numbers from 1 to 9, the next nine letters stood for the multiples of 10, from 10 to 90, and the next nine letters stood for the multiples of 100, from 100 to 900. For this purpose, in addition to the 24 letters which by that time made up the standard alphabet, three of the obsolete letters were revived: wau/digamma (Ϝ) for 6, koppa (Ϙ) for 90, and a rare Ionian letter for /ss/, today called [[sampi]] (Ͳ), for 900. This system has remained in use in Greek up to the present day, although today it is only employed for limited purposes, similar to the way Roman numerals are used in English. The three extra symbols are today written as ϛ, ϟ and ϡ respectively. |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

== List of letters == |

|||

!rowspan="2"|Phoenician |

|||

Below is a table listing the Greek letters, as well as their forms when [[romanization|romanized]]. The table also provides the equivalent [[Phoenician alphabet|Phoenician letter]] from which each Greek letter is derived. Pronunciations transcribed using the [[International Phonetic Alphabet]]. |

|||

!colspan="4"|Greek |

|||

!rowspan="2"|English |

|||

The classical pronunciation given below is the reconstructed pronunciation of Attic in the late 5th and early 4th century BC. Some of the letters had different pronunciations in pre-classical times or in non-Attic dialects. For details, see [[History of the Greek alphabet]] and [[Ancient Greek phonology]]. For details on post-classical Ancient Greek pronunciation, see [[Koine Greek phonology]]. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!letter!!ancient!!modern!!spelling |

|||

!rowspan="2" style="background:#ccf;"|Letter |

|||

!rowspan="2" style="background:#ccf;"|Corresponding<br />[[Phoenician alphabet|Phoenician]]<br />letter |

|||

!colspan="4" style="background:#ccf;"|Name |

|||

!colspan="2" style="background:#ccf;"|[[Transliteration of Greek to the Latin alphabet|Transliteration]]<sup>1</sup> <!-- footnote explains caveats --> |

|||

!colspan="2" style="background:#ccf;"|[[International Phonetic Alphabet|Pronunciation]] |

|||

!rowspan="2" style="background:#ccf;"|[[Greek numerals|Numeric<br />value]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|aleph|| Α || {{IPA|alpʰa}}||{{IPA|ˈalfa}}||{{lang|el|ἄλφα}}||alpha |

|||

! style="background:#cff;"|English |

|||

! style="background:#cff;"|Ancient<br />Greek |

|||

! style="background:#cff;"|Medieval<br />Greek<br />([[polytonic orthography|polytonic]]) |

|||

! style="background:#cff;"|{{audio-nohelp|Ell-AlphabitosUpload.ogg|Modern<br />Greek}} |

|||

! style="background:#cff;"|Ancient<br />Greek |

|||

! style="background:#cff;"|Modern<br />Greek |

|||

! style="background:#cff;"|Classical<br />Ancient<br />Greek |

|||

! style="background:#cff;"|Modern<br />Greek |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|beth|| Β || {{IPA|bɛːta}}||{{IPA|ˈvita}}||{{lang|el|βῆτα}}||beta |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Α α |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician aleph.svg|x16px|Aleph]] [[Aleph (letter)|Aleph]] |

|||

|[[Alpha (letter)|Alpha]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|ἄλφα}} |

|||

|άλφα |

|||

|colspan="2"|a |

|||

|{{IPA|[a] [aː]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[a]}} |

|||

|1 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|gimel|| Γ || {{IPA|gamma}}||{{IPA|ˈγama}}||{{lang|el|γάμμα}}||gamma |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Β β |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician beth.svg|x16px|Beth]] [[Beth (letter)|Beth]] |

|||

|[[Beta (letter)|Beta]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|βῆτα}} |

|||

|βήτα |

|||

|b |

|||

|v |

|||

|{{IPA|[b]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[v]}} |

|||

|2 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|daleth|| Δ || {{IPA|delta}}||{{IPA|ˈðelta}}||{{lang|el|δέλτα}}||delta |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Γ γ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician gimel.svg|x16px|Gimel]] [[Gimel (letter)|Gimel]] |

|||

|[[Gamma (letter)|Gamma]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|γάμμα}} |

|||

|γάμ(μ)α |

|||

|g |

|||

|gh, g, y |

|||

|{{IPA|[ɡ]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[ɣ], [ʝ]}} |

|||

|3 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|heth|| Η || {{IPA|hɛːta, ɛːta}}||{{IPA|ˈita}}||{{lang|el|ἦτα}}||eta |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Δ δ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician daleth.svg|x16px|Daleth]] [[Daleth]] |

|||

|[[Delta (letter)|Delta]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|δέλτα}} |

|||

|δέλτα |

|||

|d |

|||

|d, dh |

|||

|{{IPA|[d]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[ð]}} |

|||

|4 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|teth|| Θ || {{IPA|tʰɛːta}}||{{IPA|ˈθita}}||{{lang|el|θῆτα}}||theta |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Ε ε |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician he.svg|x16px|He]] [[He (letter)|He]] |

|||

|[[Epsilon]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|εἶ}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|ἒ ψιλόν}} |

|||

|έψιλον |

|||

|colspan="2"|e |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{IPA|[e]}} |

|||

|5 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|yodh|| Ι || {{IPA|iɔːta}}||{{IPA|ˈjota}}||{{lang|el|ἰῶτα}}||iota |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Ζ ζ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician zayin.svg|x16px|Zayin]] [[Zayin]] |

|||

|[[Zeta (letter)|Zeta]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|ζῆτα}} |

|||

|ζήτα |

|||

|colspan="2"|z |

|||

|{{IPA|[[Zeta (letter)#Pronunciation|[zd, dz, zː] ]]}}(?) |

|||

|{{IPA|[z]}} |

|||

|7 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|kaph|| Κ || {{IPA|kappa}}||{{IPA|ˈkapa}}||{{lang|el|κάππα}}||kappa |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Η η |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician heth.svg|x16px|Heth]] [[Heth (letter)|Heth]] |

|||

|[[Eta (letter)|Eta]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|ἦτα}} |

|||

|ήτα |

|||

|e, ē |

|||

|i |

|||

|{{IPA|[ɛː]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[i]}} |

|||

|8 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|lamedh|| Λ || {{IPA|lambda}}||{{IPA|ˈlamða}}||{{lang|el|λάμβδα}}||lambda |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Θ θ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician teth.svg|x16px|Teth]] [[Teth]] |

|||

|[[Theta (letter)|Theta]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|θῆτα}} |

|||

|θήτα |

|||

|colspan="2"|th |

|||

|{{IPA|[tʰ]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[θ]}} |

|||

|9 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|mem|| Μ || {{IPA|myː}}||{{IPA|mi}}||{{lang|el|μῦ}}||mu |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Ι ι |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician yodh.svg|x16px|Yodh]] [[Yodh]] |

|||

|[[Iota (letter)|Iota]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|ἰῶτα}} |

|||

|(γ)ιώτα |

|||

|colspan="2"|i |

|||

|{{IPA|[i] [iː]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[i], [ʝ]}} |

|||

|10 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|nun|| Ν || {{IPA|nyː}}||{{IPA|ni}}||{{lang|el|νῦ}}||nu |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Κ κ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician kaph.svg|x16px|Kaph]] [[Kaph]] |

|||

|[[Kappa (letter)|Kappa]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|κάππα}} |

|||

|κάπ(π)α |

|||

|colspan="2"|k |

|||

|{{IPA|[k]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[k], [c]}} |

|||

|20 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|reš|| Ρ || {{IPA|rɔː}}||{{IPA|ro}}||{{lang|el|ῥῶ}}||rho |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Λ λ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician lamedh.svg|x16px|Lamedh]] [[Lamedh]] |

|||

|[[Lambda (letter)|Lambda]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|λάβδα}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|λάμβδα}} |

|||

|λάμ(β)δα |

|||

|colspan="2"|l |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{IPA|[l]}} |

|||

|30 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|taw|| Τ || {{IPA|tau}}||{{IPA|taf}}||{{lang|el|ταῦ}}||tau |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Μ μ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician mem.svg|x16px|Mem]] [[Mem]] |

|||

|[[Mu (letter)|Mu]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|μῦ}} |

|||

|μι/μυ |

|||

|colspan="2"|m |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{IPA|[m]}} |

|||

|40 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|} |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Ν ν |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician nun.svg|x16px|Nun]] [[Nun (letter)|Nun]] |

|||

In the cases of the three historical sibilant letters below, the correspondence between Phoenician and Ancient Greek is less clear, with apparent mismatches both in letter names and sound values. The early history of these letters (and the fourth sibilant letter, obsolete [[san]]) has been a matter of some debate. Here too, the changes in the pronuncation of the letter names between Ancient and Modern Greek are regular. |

|||

|[[Nu (letter)|Nu]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|νῦ}} |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

|νι/νυ |

|||

!rowspan="2"|Phoenician |

|||

!colspan="4"|Greek |

|||

!rowspan="2"|English |

|||

|50 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!letter!!ancient!!modern!!spelling |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Ξ ξ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician samekh.svg|x16px|Samekh]] [[Samekh]] |

|||

|[[Xi (letter)|Xi]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|ξεῖ}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|ξῖ}} |

|||

|ξι |

|||

|x |

|||

|x, ks |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{IPA|[ks]}} |

|||

|60 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|zayin || Ζ || {{IPA|dzɛːta}}||{{IPA|zita}}||{{lang|el|ζῆτα}}||zeta |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Ο ο |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician ayin.svg|x16px|Ayin]] [[Ayin|'Ayin]] |

|||

|[[Omicron]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|οὖ}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|ὂ μικρόν}} |

|||

|όμικρον |

|||

|colspan="2"|o |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{IPA|[o]}} |

|||

|70 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|samekh|| Ξ || {{IPA|kseː}}||{{IPA|ksi}}||{{lang|el|ξεῖ, ξῖ}}||xi |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Π π |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician pe.svg|x16px|Pe]] [[Pe (letter)|Pe]] |

|||

|[[Pi (letter)|Pi]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|πεῖ}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|πῖ}} |

|||

|πι |

|||

|colspan="2"|p |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{IPA|[p]}} |

|||

|80 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|šin || Σ || {{IPA|siɡma}}||{{IPA|siɣma}}||{{lang|el|σίγμα}}||siɡma |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Ρ ρ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician res.svg|x16px|Res]] [[Resh]] |

|||

|[[Rho (letter)|Rho]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|ῥῶ}} |

|||

|ρω |

|||

|r, rh |

|||

|r |

|||

|{{IPA|[r]}}, {{IPA|[r̥]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[r]}} |

|||

|100 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|} |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Σ σ ς |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician sin.svg|x16px|Sin]] [[Shin (letter)|Sin]] |

|||

In the following group of consonant letters, the older forms of the names in Ancient Greek were spelled with {{lang|grc|-εῖ}}, indicating an original pronunciation with ''-ē''. In Modern Greek these names are spelled with {{lang|el|-ι}}. |

|||

|[[Sigma (letter)|Sigma]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|σῖγμα}} |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

|σίγμα |

|||

!colspan="5"|Greek |

|||

!rowspan="2"|English |

|||

|200 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!letter!!ancient!!spellinɡ!!modern!!spelling |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Τ τ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician taw.svg|x16px|Taw]] [[Taw (letter)|Taw]] |

|||

|[[Tau (letter)|Tau]] |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{lang|grc|ταῦ}} |

|||

|ταυ |

|||

|colspan="2"|t |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{IPA|[t]}} |

|||

|300 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| Ξ || {{IPA|kseː}}||{{lang|el|ξεῖ}}||{{IPA|ksi}}||{{lang|el|ξῖ}}||xi |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Υ υ |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician waw.svg|x16px|Waw]] [[Waw (letter)|Waw]] |

|||

|[[Upsilon (letter)|Upsilon]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|ὗ/ὖ}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|ὖ ψιλόν}} |

|||

|ύψιλον |

|||

|u, y |

|||

|y, v, f |

|||

|{{IPA|[ʉ(ː)], [y(ː)]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[i]}} |

|||

|400 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| Π || {{IPA|peː}}||{{lang|el|πεῖ}}||{{IPA|pi}}||{{lang|el|πῖ}}||pi |

|||

|<span style="font-size:133%;">Φ φ |

|||

|rowspan="3"|origin debated |

|||

|[[Phi (letter)|Phi]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|φεῖ}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|φῖ}} |

|||

|φι |

|||

|ph |

|||

|f |

|||

|{{IPA|[pʰ]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[f]}} |

|||

|500 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| Φ || {{IPA|pʰeː}}||{{lang|el|φεῖ}}||{{IPA|fi}}||{{lang|el|φῖ}}||phi |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Χ χ |

|||

|[[Chi (letter)|Chi]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|χεῖ}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|χῖ}} |

|||

|χι |

|||

|ch |

|||

|ch, kh |

|||

|{{IPA|[kʰ]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[x], [ç]}} |

|||

|600 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| Χ || {{IPA|kʰeː}}||{{lang|el|χεῖ}}||{{IPA|çi}}||{{lang|el|χῖ}}||chi |

|||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Ψ ψ |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Psi (letter)|Psi]] |

|||

|{{lang| |

| Ψ || {{IPA|pseː}}||{{lang|el|ψεῖ}}||{{IPA|psi}}||{{lang|el|ψῖ}}||psi |

||

|{{lang|grc|ψῖ}} |

|||

|ψι |

|||

|colspan="2"|ps |

|||

|colspan="2"|{{IPA|[ps]}} |

|||

|700 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|style="font-size:133%;"|Ω ω |

|||

|[[Image:Phoenician ayin.svg|x16px|Ayin]] [[Ayin|'Ayin]] |

|||

|[[Omega]] |

|||

|{{lang|grc|ὦ}} |

|||

|{{lang|grc|ὦ μέγα}} |

|||

|ωμέγα |

|||

|o, ō |

|||

|o |

|||

|{{IPA|[ɔː]}} |

|||

|{{IPA|[o]}} |

|||

|800 |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

# For details and different transliteration systems see [[Romanization of Greek]]. |

|||

The following group of vowel letters were originally called simply by their sound values as long vowels: ē, ō, ū, and {{IPA|ɔ}}. Their modern names contain adjectival qualifiers that were added during the Byzantine period, to distinguish between letters that had become confusable. Thus, the letters 〈ο〉 and 〈ω〉, pronounced identically by this time, were called ''o mikron'' ("small o") and ''o mega'' ("big o") respectively. The letter 〈ε〉 was called ''e psilon'' ("plain e") to distinguish it from the identically pronounced digraph 〈αι〉, while, similarly, 〈υ〉, which at this time was pronounced {{IPAblink|y}}, was called ''y psilon'' ("plain y") to distinguish it from the identically pronounced digraph 〈οι〉. |

|||

=== Obsolete letters === |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

* [[Digamma]] or ''wau'' (Ϝ) was the continuation of Phoenician [[waw (letter)|waw]], denoting the sound /w/. It stood in the sixth position in the alphabet, after Ε. It dropped out of use because the sound /w/ became mute during the archaic and classical era. It remained in use as a numeric sign denoting the number six. In this function, its shape in uncial and cursive writing changed to "ϛ", until in medieval Greek handwriting it was conflated with an accidentally similar ligature sign for "στ". The symbol "ϛ", both in its function as a numeral continuing that of digamma and in its function as a ligature, is today called "stigma". |

|||

!colspan="7"|Greek |

|||

* [[San (letter)|San]] (Ϻ), shaped like a modern M, was a continuation either of Phoenician [[Shin (letter)|sin]] or [[tsade]] (the exact relationship being unclear), and was used as an alternative to sigma in writing the sound /s/ in some dialects. It was replaced by standard sigma during the classical period. Its position in the alphabet was after pi. |

|||

!rowspan="2"|English |

|||

* [[Koppa (letter)|Koppa]] (Ϙ) was the continuation of Phoenician [[Qoph]] and was used in some dialects to denote the retracted allophone of /k/ before back vowels. Like digamma, it remained in use as a numeral sign after it had become obsolete as an alphabetic letter. It is used for the number 90, reflecting its original position in the alphabet between pi and rho. In uncial and cursive handwriting its shape changed to {{GrGl|Koppa cursive 03}}{{GrGl|Koppa cursive 04}}. In its numeral function it is today displayed as {{lang|grc|ϟ}}. |

|||

|- |

|||

* [[Sampi]] ({{GrGl|Sampi palaeographic 04|3=Ͳ}}), of unknown origin, was a short-lived addition used for writing a consonant /ts/ or /ss/ in some Ionic forms of Greek, and then remained in use as a numeral for 900. It may have been a continuation of san, although in its numeral position it did not continue the position of the latter but was placed at the end, after omega. In later handwriting its shape changed to {{GrGl|Sampi palaeographic 05}} and it is today displayed as {{lang|grc|ϡ}}. Its modern name ''sampi'' probably refers to its shape ("(ὡ)σὰν πῖ", i.e. "like a pi"). |

|||

!letter!!ancient!!spellinɡ!!medieval!!meaning!!modern!!spelling |

|||

|- |

|||

| Ε || {{IPA|eː}}||{{lang|el|εἶ}}||{{lang|el|ἐ ψιλόν}}|| 'plain e' ||{{IPA|ˈepsilon}}||{{lang|el|ἔψιλον}}||epsilon |

|||

|- |

|||

| Ο || {{IPA|oː}}||{{lang|el|οὖ}}||{{lang|el|ὀ μικρόν}}|| 'small o' ||{{IPA|ˈomikron}}||{{lang|el|ὄμικρον}}||omicron |

|||

|- |

|||

| Υ || {{IPA|uː}}, {{IPA|yː}}||{{lang|el|ὖ}}||{{lang|el|ὐ ψιλόν}}|| 'plain y' ||{{IPA|ˈipsilon}}||{{lang|el|ὔψιλον}}||upsilon |

|||

|- |

|||

| Ω || {{IPA|ɔː}}||{{lang|el|ὦ}}||{{lang|el|ὠ μέγα}}|| 'big o' ||{{IPA|oˈmeɣa}}||{{lang|el|ὠμέγα}}||omega |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

=== |

=== Letter shapes === |

||

[[File:Gospel Estienne 1550.jpg|thumb|right|A 16th century edition of the New Testament, printed in a renaissance typeface by [[Claude Garamond]]]] |

|||

Some letters can occur in variant shapes, mostly inherited from medieval [[History of the Greek alphabet#Later developments|minuscule]] handwriting. While their use in normal typography of Greek is purely a matter of font styles, some such variants have been given separate encodings in [[Unicode]]. |

|||

Like Latin and other alphabetic scripts, Greek originally had only a single form of each letter, without a distinction between uppercase and lowercase. This distinction is an innovation of the modern era, drawing on different lines of development of the letter shapes in earlier handwriting. |

|||

*The symbol {{Unicode|ϐ}} ("curled beta") is a cursive variant form of [[Beta (letter)|beta]] (β). In the French tradition of Ancient Greek typography, β is used word-initially, and {{Unicode|ϐ}} is used word-internally. |

|||

*The letter [[epsilon]] can occur in two equally frequent stylistic variants, either shaped <math>\epsilon\,\!</math> ('lunate epsilon', like a semicircle with a stroke) or <math>\varepsilon\,\!</math> (similar to a reversed number 3). The symbol {{Unicode|ϵ}} (U+03F5) is designated specifically for the lunate form, used as a technical symbol. |

|||

*The symbol {{Unicode|ϑ}} ("script theta") is a cursive form of [[theta]] (θ), frequent in handwriting, and used with a specialized meaning as a technical symbol. |

|||

*The symbol {{Unicode|ϰ}} ("kappa symbol") is a cursive form of [[kappa]] (κ), used as a technical symbol. |

|||

*The symbol {{Unicode|ϖ}} ("variant pi") is an archaic script form of [[pi]] (π), also used as a technical symbol. |

|||

*The letter [[rho (letter)|rho]] (ρ) can occur in different stylistic variants, with the descending tail either going straight down or curled to the right. The symbol {{Unicode|ϱ}} (U+03F1) is designated specifically for the curled form, used as a technical symbol. |

|||

*The letter [[sigma]], in standard orthography, has two variants: ς, used only at the ends of words, and σ, used elsewhere. The form {{Unicode|ϲ}} ("[[Sigma#Lunate_sigma|lunate sigma]]", resembling a Latin ''[[c]]'') is a medieval stylistic variant that can be used in both environments without the final/non-final distinction. |

|||

*The capital letter [[upsilon]] (Υ) can occur in different stylistic variants, with the upper strokes either straight like a Latin ''Y'', or slightly curled. The symbol {{Unicode|ϒ}} (U+03D2) is designated specifically for the curled form, used as a technical symbol. |

|||

*The letter [[Phi (letter)|phi]] can occur in two equally frequent stylistic variants, either shaped as <math>\textstyle\phi\,\!</math> (a circle with a vertical stroke through it) or as <math>\textstyle\varphi\,\!</math> (a curled shape open at the top). The symbol {{Unicode|ϕ}} (U+03D5) is designated specifically for the closed form, used as a technical symbol. |

|||

The oldest forms of the letters in antiquity are [[majuscule]] forms. Besides the upright, straight inscriptional forms (capitals) found in stone carvings or incised pottery, more fluent writing styles adapted for handwriting on soft materials were also developed during antiquity. Such handwriting has been preserved especially from [[papyrus]] manuscripts in [[Egypt]] since the [[Hellenistic period]]. Ancient handwriting developed two distinct styles: [[uncial]] writing, with carefully drawn, rounded block letters of about equal size, used as a [[book hand]] for carefully produced literary and religious manuscripts, and [[cursive#Cursive Greek|cursive]] writing, used for everyday purposes.<ref name="thompson">{{harvnb|Thompson|1912|pp=102–103}}</ref> The cursive forms approached the style of lowercase letter forms, with [[Ascender (typography)|ascenders]] and descenders, as well as many connecting lines and ligatures between letters. |

|||

== Digraphs and diphthongs == |

|||

{{further2|[[Greek orthography]]}} |

|||

In the 9th and 10th century, uncial book hands were replaced with a new, more compact writing style, with letter forms partly adapted from the earlier cursive.<ref name="thompson"/> This [[Greek minuscule|minuscule]] style remained the dominant form of handwritten Greek into the modern era. During the [[Renaissance]], western printers adopted the minuscule letter forms as lowercase printed typefaces, while modelling uppercase letters on the ancient inscriptional forms. The orthographic practice of using the letter case distinction for marking proper names, titles etc. developed in parallel to the practice in Latin and other western languages. |

|||

A [[Digraph (orthography)|digraph]] is a pair of letters used to write one sound or a combination of sounds that does not correspond to the written letters in sequence. The orthography of Greek includes several digraphs, including various pairs of vowel letters that used to be pronounced as [[diphthong]]s but have been shortened to [[monophthong]]s in pronunciation. Many of these are characteristic developments of modern Greek, but some, such as ΟΥ (pronounced {{IPA|[oː]}}, then {{IPA|[uː]}}) and ΕΙ (pronounced {{IPA|[eː]}}, then {{IPA|[iː]}}), were already present in Classical Greek. None of them are regarded as a letter of the alphabet. |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

During the [[Medieval Greek|Byzantine period]], it became customary to write the [[silent letter|silent]] iota in digraphs as an [[iota subscript]] ({{lang|grc|ᾳ, ῃ, ῳ}}). |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan="2"|Inscription |

|||

!colspan="2"|Manuscript |

|||

!colspan="2"|Modern print |

|||

|- |

|||

!archaic!!classical!![[uncial]]!![[Greek minuscule|minuscule]]!!lowercase!!uppercase |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Alpha 03}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Alpha classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Alpha}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Alpha.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|α |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Α |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Beta 16}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Beta classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Beta}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Beta.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|β |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Β |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Gamma archaic 1}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Gamma classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Gamma}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Gamma.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|γ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Γ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Delta 04}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Delta classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Delta}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Delta.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|δ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Δ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Epsilon archaic}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Epsilon classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Epsilon}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Epsilon.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ε |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ε |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Zeta archaic}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Zeta classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Zeta}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Zeta.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ζ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ζ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Eta archaic}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Eta classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Eta}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Eta.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|η |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Η |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Theta archaic}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Theta classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Theta}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Theta.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|θ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Θ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Iota normal}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Iota classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Iota}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Iota.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ι |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ι |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Kappa normal}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Kappa classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Kappa}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Kappa.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|κ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Κ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Lambda 09}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Lambda classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Lambda}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Lambda.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|λ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Λ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Mu 04}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Mu classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Mu}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Mu.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|μ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Μ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Nu 01}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Nu classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Nu}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Nu.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ν |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ν |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Xi archaic}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Xi classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Xi}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Xi.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ξ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ξ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Omicron 04}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Omicron classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Omicron}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Omicron.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ο |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ο |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Pi archaic}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Pi classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Pi}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Pi.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|π |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Π |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Rho pointed}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Rho classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Rho}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Rho.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ρ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ρ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Sigma normal}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Sigma classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Sigma}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Sigma.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|σς |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Σ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Tau normal}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Tau classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Tau}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Tau.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|τ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Τ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Upsilon normal}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Upsilon classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Upsilon}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Upsilon.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|υ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Υ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Phi 03}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Phi archaic}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Phi}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Phi.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|φ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Φ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Chi normal}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Chi classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Chi}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Chi.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|χ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Χ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Psi straight}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Psi classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Psi}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Psi.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ψ |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ψ |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{GrGl|Omega normal}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|Omega classical}} |

|||

|{{GrGl|uncial Omega}} |

|||

|[[File:Greek minuscule Omega.svg|x30px]] |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|ω |

|||

|style="font-family:serif;font-size:larger;"|Ω |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

== |

== Derived alphabets == |

||

[[File:Masiliana tablet.svg|thumb|right|300px|The earliest Etruscan [[abecedarium]], from Marsiliana d'Albegna, still almost identical with contemporary archaic Greek alphabets]] |

|||

{{main|Greek diacritics}} |

|||

[[File:Wulfila bibel.jpg|thumb|right|A page from the [[Codex Argenteus]], a 6th century bible manuscript in Gothic]] |

|||

The Greek alphabet was the model for various others:{{sfn|Coulmas|1996|p=}} |

|||

*The [[Latin alphabet]], together with various other [[Old Italic script|ancient scripts in Italy]], adopted from an archaic form of the Greek alphabet brought to Italy by Greek colonists in the late 8th century BC, via [[Etruscan language|Etruscan]] |

|||

*The [[Gothic alphabet]], devised in the 4th century AD to write the [[Gothic language]], based on a combination of Greek and Latin models |

|||

*The [[Glagolitic alphabet]], devised in the 9th century AD for writing [[Old Church Slavonic]] |

|||

*The [[Cyrillic script]], which replaced the Glagolitic alphabet shortly afterwards |

|||

It is also considered a possible ancestor of the [[Armenian alphabet]], which in turn influenced the development of the [[Georgian alphabet]].<ref>{{harvnb|Stevenson|2007|p=1158}}</ref> |

|||

In the [[polytonic orthography]] traditionally used for ancient Greek, vowels can carry [[diacritic]]s, namely accents and breathings. The accents are the [[acute accent]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|ά}}}}), the [[grave accent]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|ὰ}}}}), and the [[circumflex accent]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|α̃ }}}} or {{big|{{lang|grc|α̑}}}} ). In Ancient Greek, these accents marked different forms of the [[pitch accent]] on a vowel. By the end of the Roman period, pitch accent had evolved into a [[Stress (linguistics)|stress accent]], and in later Greek all of these accents marked the stressed vowel. The breathings are the [[Spiritus asper|rough breathing]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|ἁ}}}}), marking an {{IPA|/h/}} sound at the beginning of a word, and the [[Spiritus lenis|smooth breathing]] ({{Big|{{lang|grc|ἀ}}}}), marking its absence. The letter rho (ρ), although not a vowel, always carries a rough breathing when it begins a word. Another diacritic used in Greek is the [[Double dot (diacritic)|diaeresis]] ({{big|{{lang|grc|¨}}}}), indicating a [[Hiatus (linguistics)|hiatus]]. |

|||

== Other uses == |

|||

In 1982, the old spelling system, known as polytonic, was simplified to become the monotonic system, which is now official in Greece. The accents have been reduced to one, the ''tonos'', and the breathings were abolished. |

|||

=== Use for other languages === |

|||

Apart from the daughter alphabets listed above, which were adapted from Greek but developed into separate writing systems, the Greek alphabet has also been adopted at various times and in various places to write other languages.{{sfn|Macrakis, Stavros M.|1996|p=}} For some of them, additional letters were introduced. |

|||

==== Antiquity ==== |

|||

== Use of the Greek script for other languages{{anchor|Greek script}} == |

|||

The Greek alphabet has been adopted at various times and in various places to write other languages.{{sfn|Macrakis, Stavros M.|1996|p=}} For some languages, additional letters were introduced. |

|||

=== Antiquity === |

|||

*Most of the [[alphabets of Asia Minor]], in use c. 800-300 BC to write languages like [[Lydian language|Lydian]] and [[Phrygian language|Phrygian]], were the early Greek alphabet with only slight modifications — as were the original [[Old Italic alphabet]]s. |

*Most of the [[alphabets of Asia Minor]], in use c. 800-300 BC to write languages like [[Lydian language|Lydian]] and [[Phrygian language|Phrygian]], were the early Greek alphabet with only slight modifications — as were the original [[Old Italic alphabet]]s. |

||

*Some [[Paleo-Balkan languages]], including [[Thracian language|Thracian]]. For other neighboring languages or dialects, such as [[Ancient Macedonian language|Ancient Macedonian]], isolated words are preserved in Greek texts, but no continuous texts are preserved. |

*Some [[Paleo-Balkan languages]], including [[Thracian language|Thracian]]. For other neighboring languages or dialects, such as [[Ancient Macedonian language|Ancient Macedonian]], isolated words are preserved in Greek texts, but no continuous texts are preserved. |

||

*The [[Greco–Iberian alphabet]] was used for writing the ancient [[Iberian language]] in parts of modern Spain. |

|||

*Some [[Gaulish language|Gaulish]] inscriptions (in modern France) use the Greek alphabet (c. 300 BC). |

*Some [[Gaulish language|Gaulish]] inscriptions (in modern France) use the Greek alphabet (c. 300 BC). |

||

*The [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] text of the [[Bible]] was written in Greek letters in [[Origen]]'s [[Hexapla]]. |

*The [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] text of the [[Bible]] was written in Greek letters in [[Origen]]'s [[Hexapla]]. |

||

*The Bactrian |

*The [[Bactrian language]], an [[Iranic languages|Iranic]] language spoken in what is now [[Afghanistan]], was written in the Greek alphabet during the [[Kushan Empire]] (65-250 AD). It adds an extra letter 〈[[Sho (letter)|þ]]〉 for the ''sh'' sound {{IPAblink|ʃ}}.{{sfn|Sims-Williams|1997|p=}} |

||

*The [[Coptic alphabet]] adds eight letters derived from [[Demotic (Egyptian)|Demotic]]. It is still used today, mostly in Egypt, to write |

*The [[Coptic alphabet]] adds eight letters derived from [[Demotic (Egyptian)|Demotic]]. It is still used today, mostly in Egypt, to write [[Coptic language|Coptic]], the liturgical language of Egyptian Christians. Letters usually retain an [[Uncial script|uncial form]] different from the forms used for Greek today. |

||

===Middle Ages=== |

====Middle Ages==== |

||