Myanmar: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Burma''' or |

'''Burma''' or<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/country_profiles/1300003.stm|work=BBC|title= Country profile: Burma}}</ref> the '''Union of Myanmar''' ([[Burmese language|Burmese]]: [[Image:Myanmar long form.svg|150px]], {{pronounced|pjìdàunzṵ mjəmà nàinŋàndɔ̀}}), is the largest country by geographical area in mainland [[Southeast Asia]]. |

||

The [[British]] began conquering Burma in 1824 and incorporated the country into the [[British Raj]] in 1886. Burma was administered as a province of British India until 1937 when it became a separate, self-governing colony. The country achieved independence from the United Kingdom on [[4 January]] [[1948]], as the "Union of Burma." It became the "Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma" on [[4 January]] [[1974]], before reverting to the "Union of Burma" on [[23 September]] [[1988]]. On [[18 June]] [[1989]], the [[State Law and Order Restoration Council]] (SLORC) adopted the name "Union of Myanmar" for English transliteration. This controversial name change in English was not recognized by the opposition groups and many English-speaking nations, as the government which decreed it is unrecognized. |

The [[British]] began conquering Burma in 1824 and incorporated the country into the [[British Raj]] in 1886. Burma was administered as a province of British India until 1937 when it became a separate, self-governing colony. The country achieved independence from the United Kingdom on [[4 January]] [[1948]], as the "Union of Burma." It became the "Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma" on [[4 January]] [[1974]], before reverting to the "Union of Burma" on [[23 September]] [[1988]]. On [[18 June]] [[1989]], the [[State Law and Order Restoration Council]] (SLORC) adopted the name "Union of Myanmar" for English transliteration. This controversial name change in English was not recognized by the opposition groups and many English-speaking nations, as the government which decreed it is unrecognized. |

||

Revision as of 16:30, 9 May 2008

Union of Myanmar | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Kaba Ma Kyei | |

| |

| Capital | Naypyidaw |

| Largest city | Yangon (Rangoon) |

| Official languages | Burmese |

| Recognised regional languages | Jingpho, Shan, Karen, Mon, Rakhine |

| Demonym(s) | Burmese |

| Government | Military dictatorship |

| Senior General Than Shwe | |

• Vice Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council | Vice-Senior General Maung Aye |

| General Thein Sein | |

• Secretary-1 of the State Peace and Development Council | Lt-Gen Thiha Thura Tin Aung Myint Oo |

| Establishment | |

• Bagan | 1044-1287 |

• Small Kingdoms | 1287-1531 |

• Taungoo | 1531-1752 |

• Konbaung | 1752-1885 |

• Colonial rule | 1886-1948 |

• Independence from the United Kingdom | 4 January 1948 |

| Area | |

• Total | 676,578 km2 (261,228 sq mi) (40th) |

• Water (%) | 3.06 |

| Population | |

• 2005-2006 estimate | 55,390,000 (24th) |

• 1983 census | 33,234,000 |

• Density | 75/km2 (194.2/sq mi) (119th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2005 estimate |

• Total | $93.77 billion (59th) |

• Per capita | $1,691 (150th) |

| HDI (2007) | Error: Invalid HDI value (132nd) |

| Currency | kyat (K) (mmK) |

| Time zone | UTC+6:30 (MMT) |

| Calling code | 95 |

| ISO 3166 code | MM |

| Internet TLD | .mm |

| |

Burma or[1] the Union of Myanmar (Burmese: ![]() , IPA: [pjìdàunzṵ mjəmà nàinŋàndɔ̀]), is the largest country by geographical area in mainland Southeast Asia.

, IPA: [pjìdàunzṵ mjəmà nàinŋàndɔ̀]), is the largest country by geographical area in mainland Southeast Asia.

The British began conquering Burma in 1824 and incorporated the country into the British Raj in 1886. Burma was administered as a province of British India until 1937 when it became a separate, self-governing colony. The country achieved independence from the United Kingdom on 4 January 1948, as the "Union of Burma." It became the "Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma" on 4 January 1974, before reverting to the "Union of Burma" on 23 September 1988. On 18 June 1989, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) adopted the name "Union of Myanmar" for English transliteration. This controversial name change in English was not recognized by the opposition groups and many English-speaking nations, as the government which decreed it is unrecognized.

The country is bordered by China on the north, Laos on the east, Thailand on the southeast, Bangladesh on the west, and India on the northwest, with the Bay of Bengal to the southwest. One-third of Burma's total perimeter, 1,930 kilometres (1,199 mi), forms an uninterrupted coastline.

The country's diverse population has played a major role in defining its politics, history and demographics in modern times. Its political system remains under the tight control of SPDC, the military led government, since 1992, by Senior General Than Shwe. The military has dominated government since General Ne Win led a coup in 1962 that toppled the civilian government of U Nu. Part of the British Empire until 1948, Burma continues to struggle to mend its ethnic tensions. The country's culture, heavily influenced by neighbours, is based on Theravada Buddhism intertwined with local elements.

Etymology and origins

The name "Myanmar" is derived from the local short-form name Myanma Naingngandaw.[2] In Burmese, the name Myanma (or Mranma Prañ) has been used since the thirteenth century.[3] Its etymology remains unclear. In older English documents the usage was Bermah, and later Burmah. Burma is known as Birmanie in French, Birmania in both Italian and Spanish and Birmânia in Portuguese.

In English it is pronounced variously as /ˌmjɑnˈmɑr/, /ˈmjɑːnmɑr/, /ˌmaɪənˈmɑr/, /ˈmiːənmɑr/, or /miˈɑːnmɑr/.[4][5][6])

On 18 June 1989, the military junta passed the 'Adaptation of Expressions Law' that officially changed the English version of the country's name from Burma to Myanmar, and changed the English versions of many place names in the country along with it, such as its former capital city from Rangoon to Yangon (which represents its pronunciation more accurately in Burmese though not in Arakanese). This prompted one scholar to coin the term 'Myanmarification' to refer to the top-down programme of political and cultural reform that led to and followed in the wake of this renaming.[7] This decision has not been subject to independent legislation and no national referendum was held to decide this change by the people.[2] Within the Burmese language, Myanmar is the written, literary name of the country, while Bama or Bamar (from which "Burma" derives) is the oral, colloquial name. In spoken Burmese, the distinction is less clear than the English transliteration suggests.

The renaming proved to be politically controversial.[8] Opposition groups continue to use the name "Burma," since they do not recognize the legitimacy of the ruling military government nor its authority to rename the country in English. The name change has been recognized by the United Nations, China, India, Singapore, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Bangladesh, ASEAN, and Russia. However it has not been recognized by many western governments such as the United States, Australia, Canada or the United Kingdom, which continue to use "Burma," while the European Union uses "Burma/Myanmar" as an alternative.[9][10][11]

Use of "Burma" and its adjective, "Burmese," remains common in the United States and Britain. Some news organizations, such as the BBC and The Financial Times, still use these forms.[12][13] MSNBC, The Economist, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and others use "Myanmar" as the country name and "Burmese" as the adjective. Jim Lehrer, of PBS's nightly news program The Newshour with Jim Lehrer, used to call the country Myanmar but now uses the phrase Myanmar-also referred to as Burma. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation also refers to both names in their news articles.

Geography

Burma, which has a total area of 678,500 square kilometres (261,970 sq mi), is the largest country in mainland Southeast Asia, and the 40th-largest in the world, (after Zambia). It is somewhat smaller than the US state of Texas and slightly larger than Afghanistan.

It is located between Chittagong Division of Bangladesh and Assam, Nagaland and Manipur of India to the northwest. It shares its longest borders with Tibet and Yunnan of China to the northeast for a total of 2,185 km (1,358 mi). Burma is bounded by Laos and Thailand to the southeast. Burma has a 1,930 km (1,199 mi) of contiguous coastline along the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea to the southwest and the south, which forms one-third of its total perimeter.[2]

In the north, the Hengduan Shan mountains form the border with China. Hkakabo Razi, located in Kachin State, at an elevation of 5,881 m (19,295 ft), is the highest point in Burma.[15] Three mountain ranges, namely the Rakhine Yoma, the Bago Yoma, and the Shan Plateau exist within Burma, all of which run north-to-south from the Himalayas.[16] The mountain chains divide Burma's three river systems, which are the Ayeyarwady, Salween (Thanlwin), and the Sittang rivers.[14] The Ayeyarwady River, Burma's longest river, nearly 2,170 kilometres (1,348 mi) long, flows into the Gulf of Martaban. Fertile plains exist in the valleys between the mountain chains.[16] The majority of Burma's population lives in the Ayeyarwady valley, which is situated between the Rakhine Yoma and the Shan Plateau.

Much of the country lies between the Tropic of Cancer and the Equator. It lies in the monsoon region of Asia, with its coastal regions receiving over 5,000 mm (200 in) of rain annually. Annual rainfall in the delta region is approximately 2,500 mm (100 in) , while average annual rainfall in the Dry Zone, which is located in central Burma, is less than 1,000 mm (40 in) . Northern regions of the country are the coolest, with average temperatures of 21 °C (70 °F). Coastal and delta regions have mean temperatures of 32 °C (90 °F).[14]

The country's slow economic growth has contributed to the preservation of much of its environment and ecosystems. Forests, including dense tropical growth and valuable teak in lower Burma, cover over 49% of the country. Other trees indigenous to the region include acacia, bamboo, ironwood, mangrove, coconut and betel palm, and rubber has been introduced. In the highlands of the north, oak, pine and various rhododendrons cover much of the land.[17] The lands along the coast support all varieties of tropical fruits. In the Dry Zone, vegetation is sparse and stunted.

Typical jungle animals, particularly tigers and leopards are common in Burma. In upper Burma, there are rhinoceros, wild buffalo, wild boars, deer antelope and elephants, which are also tamed or bred in captivity for use as work animals, particularly in the lumber industry. Smaller mammals are also numerous, ranging from gibbons and monkeys to flying foxes and tapirs. The abundance of birds is notable with over 800 species, including parrots, peafowl, pheasants, crows, herons and paddybirds. Among reptile species there are crocodiles, geckos, cobras, pythons and turtles. Hundreds of species of freshwater fish are wide-ranging, plentiful and are very important food sources.[18]

History

Early history

The Mon people are thought to be the earliest group to migrate into the lower Ayeyarwady valley, and by the mid-900s BC were dominant in southern Burma.[19] The Mons became one of the first in South East Asia to embrace Theravada Buddhism.

The Tibeto-Burman speaking Pyu arrived later in the 1st century BC, and established several city states - of which Sri Ksetra was the most powerful - in central Ayeyarwady valley. The Mon and Pyu kingdoms were an active overland trade route between India and China. The Pyu kingdoms entered a period of rapid decline in early 9th century AD when the powerful kingdom of Nanzhao (in present-day Yunnan) invaded Ayeyarwady valley several times. In 835, Nanzhao decimated the Pyu by carrying off many captives to be used as conscripts.

Bagan (1044-1287)

Tibeto-Burman speaking Burmans, or the Bamar, began migrating to the Ayeyarwady valley from present-day Yunnan's Nanzhao kingdom starting in 7th century AD. Filling the power gap left by the Pyu, the Burmans established a small kingdom centered in Bagan in 849. But it was not until the reign of King Anawrahta (1044-1077) that Bagan's influence expanded throughout much of present-day Burma.

After Anawrahta's capture of the Mon capital of Thaton in 1057, the Burmans adopted Theravada Buddhism from the Mons. The Burmese script was created, based on the Mon script, during the reign of King Kyanzittha (1084-1112). Prosperous from trade, Bagan kings built many magnificent temples and pagodas throughout the country - many of which can still be seen today.

Bagan's power slowly waned in 13th century. Kublai Khan's Mongol forces invaded northern Burma starting in 1277, and sacked Bagan city itself in 1287. Bagan's over two century reign of Ayeyarwady valley and its periphery was over.

Small kingdoms (1287-1531)

The Mongols could not stay for long in the searing Ayeyarwady valley. But the Tai-Shan people from Yunnan who came down with the Mongols fanned out to the Ayeyarwady valley, Shan states, Laos, Siam and Assam, and became powerful players in South East Asia.

The Bagan empire was irreparably broken up into several small kingdoms:

- The Burman kingdom of Ava or Innwa (1364-1555), the successor state to three smaller kingdoms founded by Burmanized Shan kings, controlling Upper Burma (without the Shan states)

- The Mon kingdom of Hanthawady Pegu or Bago (1287-1540), founded by a Mon-ized Shan King Wareru (1287-1306), controlling Lower Burma (without Taninthayi).

- The Rakhine kingdom of Mrauk U (1434-1784), in the west.

- Several Shan states in the Shan hills in the east and the Kachin hills in the north while the northwestern frontier of present Chin hills still disconnected yet.

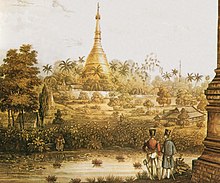

This period was characterized by constant warfare between Ava and Bago, and to a lesser extent, Ava and the Shans. Ava briefly controlled Rakhine (1379-1430) and came close to defeating Bago a few times, but could never quite reassemble the lost empire. Nevertheless, Burmese culture entered a golden age. Hanthawady Bago prospered. Bago's Queen Shin Saw Bu (1453-1472) raised the gilded Shwedagon Pagoda to its present height.

By the late 15th century, constant warfare had left Ava greatly weakened. Its peripheral areas became either independent or autonomous. In 1486, King Minkyinyo (1486-1531) of Taungoo broke away from Ava and established a small independent kingdom. In 1527, Mohnyin (Shan: Mong Yang) Shans finally captured Ava, upsetting the delicate power balance that had existed for nearly two centuries. The Shans would rule Upper Burma until 1555.

Taungoo (1531-1752)

Reinforced by fleeing Burmans from Ava, the minor Burman kingdom of Taungoo under its young, ambitious king Tabinshwehti (1531-1551) defeated the more powerful Mon kingdom at Bago, reunifying all of Lower Burma by 1540. Tabinshwehti's successor King Bayinnaung (1551-1581) would go on to conquer Upper Burma (1555), Manipur (1556), Shan states (1557), Chiang Mai (1557), Ayutthaya (1564, 1569) and Lan Xang (1574), bringing most of western South East Asia under his rule. Bayinnaung died in 1581, preparing to invade Rakhine, a maritime power controlling the entire coastline west of Rakhine Yoma, up to Chittagong province in Bengal.

Bayinnaung's massive empire unraveled soon after his death in 1581. Ayutthaya Siamese had driven out the Burmese by 1593 and went on to take Tanintharyi. In 1599, Rakhine forces aided by the Portuguese mercenaries sacked the kingdom's capital Bago. Chief Portuguese mercenary Filipe de Brito e Nicote (Burmese: Nga Zinga) promptly rebelled against his Rakhine masters and established Portuguese rule in Thanlyin (Syriam), then the most important seaport in Burma. The country was in chaos.

The Burmese under King Anaukpetlun (1605-1628) regrouped and defeated the Portuguese in 1611. Anaukpetlun reestablished a smaller reconstituted kingdom based in Ava covering Upper Burma, Lower Burma and Shan states (but without Rakhine or Taninthayi). After the reign of King Thalun (1629-1648), who rebuilt the war-torn country, the kingdom experienced a slow and steady decline for the next 100 years. The Mons successfully rebelled starting in 1740 with French help and Siamese encouragement, broke away Lower Burma by 1747, and finally put an end to the House of Taungoo in 1752 when they took Ava.

Konbaung (1752-1885)

King Alaungpaya (1752-1760), established the Konbaung Dynasty in Shwebo in 1752.[20] He founded Yangon in 1755. By his death in 1760, Alaungpaya had reunified the country. In 1767, King Hsinbyushin (1763-1777) sacked Ayutthya. The Qing Dynasty of China invaded four times from 1765 to 1769 without success. The Chinese invasions allowed the new Siamese kingdom based in Bangkok to repel the Burmese out of Siam by the late 1770s.

King Bodawpaya (1782-1819) failed repeatedly to reconquer Siam in 1780s and 1790s. Bodawpaya did manage to capture the western kingdom of Rakhine, which had been largely independent since the fall of Bagan, in 1784. Bodawpaya also formally annexed Manipur, a rebellion-prone protectorate, in 1813.

King Bagyidaw's (1819-1837) general Maha Bandula put down a rebellion in Manipur in 1819 and captured then independent kingdom of Assam in 1819 (again in 1821). The new conquests brought the Burmese adjacent to the British India. The British defeated the Burmese in the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-1826). Burma had to cede Assam, Manipur, Rakhine (Arakan) and Tanintharyi (Tenessarim).

In 1852, the British attacked a much weakened Burma during a Burmese palace power struggle. After the Second Anglo-Burmese War, which lasted 3 months, the British had captured the remaining coastal provinces: Ayeyarwady, Yangon and Bago, naming the territories as Lower Burma.

King Mindon (1853-1878) founded Mandalay in 1859 and made it his capital. He skillfully navigated the growing threats posed by the competing interests of Britain and France. In the process, Mindon had to renounce Kayah (Karenni) states in 1875. His successor, King Thibaw (1878-1885), was largely ineffectual. In 1885, the British, alarmed by the French conquest of neighboring Laos, grabbed Upper Burma. The Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885) lasted a mere one month insofar as capturing the capital Mandalay was concerned. The Burmese royal family was exiled to Ratnagiri, India. British forces spent at least another four years pacifying the country - not only in the Burman heartland but also in the Shan, Chin and Kachin hill areas. By some accounts, minor insurrections did not end until 1896.

Colonial era (1886-1948)

The United Kingdom began conquering Burma in 1824 and by 1886 had incorporated it into the British Raj. Burma was administered as a province of British India until 1937 when it became a separate, self-governing colony. To stimulate trade and facilitate changes, the British brought in Indians and Chinese, who quickly displaced the Burmese in urban areas. To this day Yangon and Mandalay have large ethnic Indian populations. Railroads and schools were built, as well as a large number of prisons, including the infamous Insein Prison, then as now used for political prisoners. Burmese resentment was strong and was vented in violent riots that paralyzed Yangon on occasion all the way until the 1930s.[21] Much of the discontent was caused by a perceived disrespect for Burmese culture and traditions, for example, what the British termed the Shoe Question: the colonisers' refusal to remove their shoes upon entering Buddhist temples or other holy places. In October 1919, Eindawya Pagoda in Mandalay was the scene of violence when tempers flared after scandalised Buddhist monks attempted to physically expel a group of shoe-wearing British visitors. The leader of the monks was later sentenced to life imprisonment for attempted murder. Such incidents inspired the Burmese resistance to use Buddhism as a rallying point for their cause. Buddhist monks became the vanguards of the independence movement, and many died while protesting. One monk-turned-martyr was U Wisara, who died in prison after a 166-day hunger strike to protest a rule that forbade him from wearing his Buddhist robes while imprisoned.[22]

Eric Blair, better known as the writer George Orwell, served in the Indian Imperial Police in Burma for five years and wrote about his experiences. An earlier writer with the same convoluted career path was Saki. During the colonial period, intermarriage between European settlers and Burmese women, as well as between Anglo-Indians (who arrived with the British) and Burmese caused the birth of the Anglo-Burmese community. This influential community was to dominate the country during colonial rule and through the mid 1960's.

On 1 April 1937, Burma became a separately administered territory, independent of the Indian administration. The vote for keeping Burma in India, or as a separate colony "khwe-yay-twe-yay" divided the populace, and laid the ground work for the insurgencies to come after independence. In the 1940s, the Thirty Comrades, commanded by Aung San, founded the Burma Independence Army. The Thirty Comrades received training in Japan.[23]

During World War II, Burma became a major frontline in the Southeast Asian Theatre. The British administration collapsed ahead of the advancing Japanese troops, jails and asylums were opened and Rangoon was deserted except for the many Anglo-Burmese and Indians who remained at their posts. A stream of some 300,000 refugees fled across the jungles into India; known as 'The Trek', all but 30,000 of those 300,000 arrived in India. Initially the Japanese-led Burma Campaign succeeded and the British were expelled from most of Burma, but the British counter-attacked using primarily troops of the British Indian Army. By July 1945, the British had retaken the country. Although many Burmese fought initially for the Japanese, some Burmese also served in the British Burma Army. In 1943, the Chin Levies and Kachin Levies were formed in the border districts of Burma still under British administration. The Burma Rifles fought as part of the Chindits under General Orde Wingate from 1943-1945. Later in the war, the Americans created American-Kachin Rangers who also fought for the occupiers. Many others fought with the British Special Operations Executive. The Burma Independence Army under the command of Aung San and the Arakan National Army fought with the Japanese from 1942-1944, but switched allegiance to the Allied side in 1945.

In 1947, Aung San became Deputy Chairman of the Executive Council of Burma, a transitional government. But in July 1947, political rivals assassinated Aung San and several cabinet members.[23]

Democratic republic (1948-1962)

On 4 January 1948, the nation became an independent republic, named the Union of Burma, with Sao Shwe Thaik as its first President and U Nu as its first Prime Minister. Unlike most other former British colonies and overseas territories, it did not become a member of the Commonwealth. A bicameral parliament was formed, consisting of a Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Nationalities.[24]

The geographical area Burma encompasses today can be traced to the Panglong Agreement, which combined Burma Proper, which consisted of Lower Burma and Upper Burma, and the Frontier Areas, which had been administered separately by the British.[25]

In 1961, U Thant, then Burma's Permanent Representative to the United Nations and former Secretary to the Prime Minister, was elected Secretary-General of the United Nations; he was the first non-Westerner to head any international organization and would serve as UN Secretary-General for ten years.[26] Among the Burmese to work at the UN when he was Secretary-General was a young Aung San Suu Kyi.

Military rule (1962-present)

Democratic rule ended in 1962 when General Ne Win led a military coup d'état. He ruled for nearly 26 years and pursued policies under the rubric of the Burmese Way to Socialism. Between 1962 and 1974, Burma was ruled by a Revolutionary Council headed by the general, and almost all aspects of society (business, media, production) were nationalized or brought under government control (including the Boy Scouts).[27] In an effort to consolidate power, General Ne Win and many top generals resigned from the military and took civilian posts and, from 1974, instituted elections in a one party system. Between 1974 and 1988, Burma was effectively ruled by General Ne Win through the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP).[28]

Almost from the beginning there were sporadic protests against the military rule, many of which were organized by students, and these were almost always violently suppressed by the government. On July 7th, 1962 the government broke up demonstrations at Rangoon University killing 15 students.[27] In 1974, the military violently suppressed anti-government protests at the funeral of U Thant. Student protests in 1975, 1976 and 1977 were quickly suppressed by overwhelming force.[28].

In 1988, unrest over economic mismanagement and political oppression by the government led to widespread pro-democracy demonstrations throughout the country known as the 8888 Uprising. Security forces killed hundreds of demonstrators, and General Saw Maung staged a coup d'état and formed the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). In 1989, SLORC declared martial law after widespread protests. The military government finalized plans for People's Assembly elections on 31 May 1989.[29]

SLORC changed the country's official English name from the "Union of Burma" to the "Union of Myanmar" in 1989.

In May 1990, the government held free elections for the first time in almost 30 years. The National League for Democracy (NLD), the party of Aung San Suu Kyi, won 392 out of a total 489 seats, but the election results were annulled by SLORC, which refused to step down.[30] Led by Than Shwe since 1992, the military regime has made cease-fire agreements with most ethnic guerrilla groups. In 1992, SLORC unveiled plans to create a new constitution through the National Convention, which began 9 January 1993. To date, this military-organized National Convention has not produced a new constitution despite well over ten years of operation.[31] In 1997, the State Law and Order Restoration Council was renamed the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

On 23 June 1997, Burma was admitted into the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The National Convention continues to convene and adjourn. Many major political parties, particularly the NLD, have been absent or excluded, and little progress has been made.[31] On 27 March 2006, the military junta, which had moved the national capital from Yangon to a site near Pyinmana in November 2005, officially named it Naypyidaw, meaning "city of the kings".[32]

In November 2006, the International Labour Organization announced it will be seeking "to prosecute members of the ruling Myanmar junta for crimes against humanity" over the continuous forced labour of its citizens by the military at the International Court of Justice.[33]

2007 protests and consequences

The August 2007 demonstrations were led by well-known dissidents, such as Min Ko Naing (with the nom de guerre Conqueror of Kings), Su Su Nway (now in hiding) and others. The military quickly cracked down and still has not allowed the International Red Cross to visit Min Ko Naing and others who are reportedly in Insein Prison after being severely tortured. Reports have surfaced of at least one death, of activist Win Shwe, under interrogation.[34]

On 19 September 2007, several hundred (possibly 2000 or more) monks staged a protest march in the city of Sittwe.[35] Larger protests in Rangoon and elsewhere ensued over the following days. Security became increasingly heavy handed, resulting in a number of deaths and injuries.[36] By 28 September, internet access had been cut[37] and journalists were reputedly warned not to report on protests.[38] Internet access was restored by at least midnight of 5 October, Burmese time.[citation needed] Sources in Burma[who?] said on 6 October that the internet seems to be working from 22:00 to 05:00 local time.

On October 13, 2007, the military junta of Burma made people march in a government rally, reportedly paying some participants 1000 kyat (approximately $0.80) each. Junta officials also approached local factories and demanded they provide 50 workers each; if they didn't, they were to be fined.[39]

On 7 February 2008, SPDC announced that there will be referendum for the Constitution in May 2008, and Election by 2010.

Various global corporations have been criticized for profiting from the dictatorship by financing Burma's military junta.[40]

World governments remain divided on how to deal with the military junta. Calls for further sanctions by United Kingdom, United States, and France are opposed by neighboring countries; in particular, China has stated its belief that "sanctions or pressure will not help to solve the issue".[41]

Cyclone Nargis

This article is about a current disaster where information can change quickly or be unreliable. The latest page updates may not reflect the most up-to-date information. |

On May 3, 2008, Cyclone Nargis devastated the country when winds of up to 150 mph[42] touched land in the densely populated, rice-farming delta of the Irrawaddy Division.[43]

More than 62,000 people are known to have died or are missing from Cyclone Nargis that hit the country's Irrawaddy delta. Shari Villarosa, who heads the U.S. Embassy in Yangon, said the number of dead could eventually exceed 100,000 because of illnesses.[44][45] Adds the World Food Programme, "Some villages have been almost totally eradicated and vast rice-growing areas are wiped out."[46]

The United Nations projects that as many as 1 million were left homeless; and the World Health Organization "has received reports of malaria outbreaks in the worst-affected area."[47] Yet in the critical days following this disaster, Myanmar's isolationist regime complicated recovery efforts by delaying the entry of United Nations planes delivering medicine, food, and other supplies into the Southeast Asian nation. Similarly, the junta continues to reject the United States offer to provide much-needed assistance. [48] The government has failed to permit entry for large-scale international relief efforts, described by the United Nations as "unprecedented".[49] The Burmese Foreign Ministry stressed its capability in handling the aftermath of the cyclone and insisted that it was not ready to accept large-scale foreign assistance.[50]

List of historical capitals

Government and politics

The Union of Myanmar is governed by a strict military regime. The current head of state is Senior General Than Shwe, who holds the posts of "Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council" and "Commander in Chief of the Defense Services". General Khin Nyunt was prime minister until 19 October 2004, when he was replaced by General Soe Win, after the purge of Military Intelligence sections within the Burma armed forces. The majority of ministry and cabinet posts are held by military officers, with the exceptions being the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Labour, and the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development, posts which are held by civilians.[51]

Elected delegates in the 1990 People's Assembly election formed the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB), a government-in-exile since December 1990, with the mission of restoring democracy.[52] Dr. Sein Win, a first cousin of Aung San Suu Kyi, has held the position of prime minister of the NCGUB since its inception. The NCGUB has been outlawed by the military government.

Major political parties in the country are the National League for Democracy and the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, although their activities are heavily regulated and suppressed by the military government. Many other parties, often representing ethnic minorities, exist. The military government allows little room for political organizations and has outlawed many political parties and underground student organizations. The military supported the National Unity Party in the 1990 elections and, more recently, an organization named the Union Solidarity and Development Association.[53]

Several human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science have reported on human rights abuses by the military government.[54][55] They have claimed that there is no independent judiciary in Burma. The military government restricts Internet access through software-based censorship that limits the material citizens can access on-line.[56][57] Forced labour, human trafficking, and child labour are common.[58] The military is also notorious for rampant use of sexual violence as an instrument of control, including systematic rapes and taking of sex slaves as porters for the military. A strong women's pro-democracy movement has formed in exile, largely along the Thai border and in Chiang Mai. There is a growing international movement to defend women's human rights issues.[59]

In 1988, the army violently repressed protests against economic mismanagement and political oppression. On 8 August 1988, the military opened fire on demonstrators in what is known as 8888 Uprising and imposed martial law. However, the 1988 protests paved way for the 1990 People's Assembly elections. The election results were subsequently annulled by Senior General Saw Maung's government. The National League for Democracy, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, won over 60% of the vote and over 80% of parliamentary seats in the 1990 election, the first held in 30 years. The military-backed National Unity Party won less than 2% of the seats. Aung San Suu Kyi has earned international recognition as an activist for the return of democratic rule, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. The ruling regime has repeatedly placed her under house arrest. Despite a direct appeal by former U.N Secretary General Kofi Annan to Senior General Than Shwe and pressure by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the military junta extended Aung San Suu Kyi's house arrest another year on 27 May 2006 under the 1975 State Protection Act, which grants the government the right to detain any persons on the grounds of protecting peace and stability in the country.[60][61] The junta faces increasing pressure from the United States and the United Kingdom. Burma's situation was referred to the UN Security Council for the first time in December 2005 for an informal consultation. In September 2006, ten of the United Nations Security Council's 15 members voted to place Burma on the council's formal agenda.[62] On Independence Day, 4 January 2007, the government released 40 political prisoners, under a general amnesty, in which 2,831 prisoners were released.[63] On 8 January 2007, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon urged the national government to free all political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi.[64] Three days later, on 11 January, five additional prisoners were released from prison.[63]

ASEAN has also stated its frustration with the Union of Myanmar's government. It has formed the ASEAN Inter-Parliamentary Myanmar Caucus to address the lack of democratisation in the country.[65] Dramatic change in the country's political situation remains unlikely, due to support from major regional powers such as India, Russia, and, in particular, China.[66][67]

In the annual ASEAN Summit in January 2007, held in Cebu, Philippines, member countries failed to find common ground on the issue of Burma's lack of political reform.[68] During the summit, ASEAN foreign ministers asked Burma to make greater progress on its roadmap toward democracy and national reconciliation.[69] Some member countries contend that Burma's human rights issues are the country's own domestic affairs, while others contend that its poor human rights record is an international issue.[69]

According to Human Rights Defenders and Promoters (HRDP), on April 18, 2007, several of its members (Myint Aye, Maung Maung Lay, Tin Maung Oo and Yin Kyi) were met by approximately a hundred people led by a local official, U Nyunt Oo, and beaten up. Due to the attack, Myint Hlaing and Maung Maung Lay were badly injured and are now hospitalized. The HRDP believes that this attack was condoned by the authorities and vows to take legal action. Human Rights Defenders and Promoters was formed in 2002 to raise awareness among the people of Burma about their human rights.

Divisions and states

The country is divided into seven states (pyine) and seven divisions (yin).[70] Divisions (တိုင္း) are predominantly Bamar. States (![]() ), in essence, are divisions which are home to particular ethnic minorities. The administrative divisions are further subdivided into districts, which are further subdivided into townships, wards, and villages.

), in essence, are divisions which are home to particular ethnic minorities. The administrative divisions are further subdivided into districts, which are further subdivided into townships, wards, and villages.

Divisions

- Ayeyarwady Division

- Bago Division

- Magway Division

- Mandalay Division

- Sagaing Division

- Tanintharyi Division

- Yangon Division

States

- Chin State

- Kachin State

- Kayin (Karen) State

- Kayah (Karenni) State

- Mon State

- Rakhine (Arakan) State

- Shan State

Administrative divisions

Number of Districts, Townships, Cities/Towns, Wards, Village Groups and Villages in Myanmar in December 31 2001[71]

| No. | State/Division | District | Township | City/Town | Wards | Village Groups | Villages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kachin State | 3 | 18 | 20 | 116 | 606 | 2630 |

| 2 | Kayah State | 2 | 7 | 7 | 29 | 79 | 624 |

| 3 | Kayin State | 3 | 7 | 10 | 46 | 376 | 2092 |

| 4 | Chin State | 2 | 9 | 9 | 29 | 475 | 1355 |

| 5 | Sagaing Division | 8 | 37 | 37 | 171 | 1769 | 6095 |

| 6 | Taninthayi Division | 3 | 10 | 10 | 63 | 265 | 1255 |

| 7 | Bago Division | 4 | 28 | 33 | 246 | 1424 | 6498 |

| 8 | Magway Division | 5 | 25 | 26 | 160 | 1543 | 4774 |

| 9 | Mandalay Division | 7 | 31 | 29 | 259 | 1611 | 5472 |

| 10 | Mon State | 2 | 10 | 11 | 69 | 381 | 1199 |

| 11 | Rakhine State | 4 | 17 | 17 | 120 | 1041 | 3871 |

| 12 | Yangon Division | 4 | 45 | 20 | 685 | 634 | 2119 |

| 13 | Shan State | 11 | 54 | 54 | 336 | 1626 | 15513 |

| 14 | Ayeyawady Division | 5 | 26 | 29 | 219 | 1912 | 11651 |

| Total | 63 | 324 | 312 | 2548 | 13742 | 65148 |

Foreign relations and military

The country's foreign relations, particularly with Western nations, have been strained. The United States has placed a ban on new investments by U.S. firms, an import ban, and an arms embargo on the Union of Myanmar, as well as frozen military assets in the United States because of the military regime's ongoing human rights abuses, the ongoing detention of Nobel Peace Prize recipient Aung San Suu Kyi, and refusal to honor the election results of the 1990 People's Assembly election.[72] Similarly, the European Union has placed sanctions on Burma, including an arms embargo, cessation of trade preferences, and suspension of all aid with the exception of humanitarian aid.[73] U.S. and European government sanctions against the military government, coupled with boycotts and other direct pressure on corporations by western supporters of the democracy movement, have resulted in the withdrawal from the country of most U.S. and many European companies. However, several Western companies remain due to loopholes in the sanctions. Asian corporations have generally remained willing to continue investing in the country and to initiate new investments, particularly in natural resource extraction. The country has close relations with neighboring India and People's Republic of China with several Indian and Chinese companies operating in the country. The French oil company Total S.A. is able to operate the Yadana natural gas pipeline from Burma to Thailand despite the European Union's sanctions on the country. Total is currently the subject of a lawsuit in French and Belgian courts for the condoning and use of the country's civilian slavery to construct the named pipeline. Experts[who?] say that the human rights abuses along the gas pipeline are the direct responsibility of Total S.A. and its American partner Chevron with aid and implementation by the Tatmadaw.[citation needed] Prior to its acquisition by Chevron, Unocal settled a similar human rights lawsuit for a reported multi-million dollar amount.[74] There remains active debate as to the extent to which the American-led sanctions have had adverse effects on the civilian population or on the military rulers.[75][76]

The country's armed forces are known as the Tatmadaw, which numbers 488,000. The Tatmadaw comprises the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force. The country ranked twelfth in the world for its number of active troops in service.[2] The military is very influential in the country, with top cabinet and ministry posts held by military officers. Although official figures for military spending are not available, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in its annual rankings, ranked the country in the top 15 military spenders in the world.[77] The country imports most of its weapons from Russia, Ukraine, China and India.

The country is building a research nuclear reactor near May Myo (Pyin Oo Lwin) with help from Russia. It is one of the signatories of the nuclear non-proliferation pact since 1992 and a member of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) since 1957. The military junta had informed the IAEA in September 2000 of its intention to construct the reactor. The research reactor outbuilding frame was built by ELE steel industries limited of Yangon and water from Anisakhan/BE water fall will be used for the reactor cavity cooling system.

ASEAN will not defend the country in any international forum following the military regime's refusal to restore democracy. In April 2007, the Malaysian Foreign Ministry parliamentary secretary Ahmad Shabery Cheek said Malaysia and other ASEAN members had decided not to defend Burma if the country's issue was raised for discussion at any international conference. "Now Myanmar has to defend itself if it is bombarded in any international forum," he said when winding up a debate at committee stage for the Foreign Ministry. He was replying to queries from opposition leader Lim Kit Siang on the next course of action to be taken by Malaysia and ASEAN with the military junta. Lim had said Malaysia must play a proactive role in pursuing regional initiatives to bring about a change in Burma and support efforts to bring the situation in Burma to the UN Security Council's attention.[78]

Drug trade

The country is a corner of the Golden Triangle of opium production. Neither Burma, Vietnam, Laos or Thailand had any history of opium production until colonial times, yet from then until very recently, most of the world's heroin came from the Golden Triangle, including Burma.

The main player in the country's drug market is the United Wa State Army, ethnic fighters who control areas along the country's eastern border with Thailand, part of the infamous Golden Triangle. The Wa army, an ally of Myanmar's ruling military junta, was once the militant arm of the Beijing-backed Burmese Communist Party. Burma has been a significant cog in the transnational drug trade since World War II.[79][80]

Poppy cultivation in the country decreased more than 80 percent from 1998 to 2006 following an eradication campaign in the Golden Triangle. Officials with the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime say opium poppy farming is now expanding. The number of hectares used to grow the crops in has bounced back 29 percent this year. A U.N. report cites corruption, poverty and a lack of government control as causes for the jump.[81]

United Nations

In 1961, U Thant, then Burma's Permanent Representative to the United Nations and former Secretary to the Prime Minister, was elected Secretary-General of the United Nations; he was the first non-Westerner to head any international organization and would serve as UN Secretary-General for ten years.[26] Among the Burmese to work at the UN when he was Secretary-General was the young Aung San Suu Kyi.

Until 2005, the United Nations General Assembly annually adopted a detailed resolution about the situation in Burma by consensus.[82][82][83][84][85] But in 2006 a divided United Nations General Assembly voted through a resolution that strongly called upon the government of Burma to end its systematic violations of human rights.[86]

In January 2007, Russia and China vetoed a draft resolution before the United Nations Security Council[87] calling on the government of Burma to respect human rights and begin a democratic transition. South Africa also voted against the resolution, arguing that since there were no peace and security concerns raised by its neighbours, the question did not belong in the Security Council when there were other more appropriate bodies to represent it, adding, "Ironically, should the Security Council adopt [this resolution] ... the Human Rights Council would not be able to address the situation in Myanmar while the Council remains seized with the matter."[88] The issue had been forced onto the agenda against the votes of Russia and the China[89] by the United States (veto power applies only to resolutions) claiming that the outflow from Burma of refugees, drugs, HIV-AIDS, and other diseases threatened international peace and security.[90]

The following September after the uprisings began and the human rights situation deteriorated, the Secretary-General dispatched his special envoy for the region, Ibrahim Gambari, to meet with the government.[91] After seeing most parties involved, he returned to New York and briefed the Security Council about his visit.[92] During this meeting, the ambassador said that the country "indeed [has experienced] a daunting challenge. However, we have been able to restore stability. The situation has now returned to normalcy. Currently, people all over the country are holding peaceful rallies within the bounds of the law to welcome the successful conclusion of the national convention, which has laid down the fundamental principles for a new constitution, and to demonstrate their aversion to recent provocative demonstrations.[93]

On 11 October the Security Council met and issued a statement and reaffirmed its "strong and unwavering support for the Secretary-General's good offices mission", especially the work by Ibrahim Gambari[94] (During a briefing to the Security Council in November, Gambari admitted that no timeframe had been set by the Government for any of the moves that he had been negotiating for.)[95]

United Nations envoy Ibrahim Gambari's latest round of intense shuttle diplomacy since September's "saffron revolution" produced no major breakthroughs in Yangon. It merely confirmed the suspicions of close Myanmar watchers that the military junta has no intentions to change its ways or compromise with anyone.

The regime, known officially as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), moved to expel the UN's top resident diplomat Charles Petrie even before Gambari set foot in Myanmar following his six-nation tour for diplomatic consultations. (The UN's Special Rapporteur for Human Rights, Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, who has been barred from Myanmar since 2003, however, returned there on Nov. 11 as scheduled).

The SPDC also rejected Gambari's offer of tripartite talks between the UN, ruling junta, and opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi. Worst of all, Gambari was rebuffed by the junta leader Senior General Than Shwe, who had kept Gambari waiting for three days during his previous visit. This time, the self-effacing diplomat endured a scolding by information minister Brigadier General Kyaw Hsan, who accused the UN of being pro-West and in favor of the sanctions imposed by the United States, European Union, and Australia.

Myanmar's government is counting on its ASEAN allies to shore up support at the upcoming Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) meetings in Singapore. The government threw open its doors to welcome ASEAN journalists earlier than planned. A group of 18 reporters went on a chaperoned Myanmar jaunt and stopped-over at Naypitaw-the fairytale capital city-in the hopes that ASEAN will approve of the regime's version of "flourishing discipline." And Myanmar's new Prime Minister Thein Sein sought out friends in socialist Laos and Vietnam on a recent visit billed by the junta as introductory courtesy calls.

Singapore, the current ASEAN chair, will host both Thein Sein and Gambari at the East Asia Summit on November 21. Barring last minute changes, it will be the first time since the crisis began in August that a senior Myanmar government official will participate in high-level talks with all major players with a direct stake in resolving it. The next steps forward could emerge from these meetings even though America and the European Union are technically excluded from the summit.

The immediate goals by all the international parties concerned can be summed up as this:

A genuine, broad-based and substantive dialogue between the SPDC, Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy Party, and ethnic minority groups; real, verifiable progress toward national reconciliation; and a lifting of restrictions on Aung San Suu Kyi and all political prisoners. In short, there should be no returning to the unsustainable status quo, as Gambari put it.

Whether the ongoing diplomatic efforts will eventually yield a peaceful transition to democracy and civilian-led rule remains to be seen. What's critical for the international community is to brainstorm strategies in the same collaborative spirit that resulted in the recent unanimous UN Security Council statement deploring the Myanmar government's violent response to peaceful demonstrations. In having China sign on to the criticism, the statement was unprecedented.

While there will always be competing strategic interests by the various players, it would be a mistake for some-the United States, UK, China, Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia-to hijack the process from the UN. Gambari, a Nigerian, is a seasoned negotiator with a track record to match the Myanmar military's 40-year reign, and he remains the best hope to break the political deadlock that has spanned two decades.

Gambari has not fully spelled out his political blueprint for Myanmar yet, though he claims there will be incentives to persuade the government to make meaningful concessions. So far, Thailand has proposed four power talks that involve the UN, China, ASEAN, and India. Yet others want to form a "Core Group" consisting of the Five Permanent Security Council Members, Japan, India, Singapore, and Norway that has long taken a traditional interest in Myanmar.[96]

Throughout this period the World Food Program has continued to organize shipments from the Mandalay Division to the famine-struck areas to the north.[97]

Human Rights

Human rights violations

In a press release of December 16, 2005 the US State Department says UN involvement in Burma is essential.[98] The US listed illicit narcotics, human rights abuses and political repression as serious problems that the UN needs to address.[99]

In a landmark legal case, some human rights groups have sued the Unocal corporation, previously known as Union Oil of California and now part of the Chevron Corporation. They charge that since the early 1990s, Unocal has joined hands with dictators in Myanmar to turn thousands of citizens there into virtual slaves under brutality. Unocal, before being purchased, stated that they had no knowledge or connection to these alleged actions although it continued working in Myanmar. This was a landmark case as this might be the first time that anybody has sued an American corporation in a U.S. court on the grounds that the company violated human rights in another country.[100][101]

Karen minority

Evidence has been gathered suggesting that the Burmese regime has marked certain ethnic minorities such as the Karen for extermination or 'Burmisation'.[102] This has received little attention from the international community, however, since it has been more subtle and indirect than the mass killings in places like Rwanda.[103]

Economy

The country is one of the poorest nations in South Asia / Southeast Asia, suffering from decades of stagnation, mismanagement and isolation. Burma's GDP grows at a rate of 2.9% annually - the lowest rate of economic growth in the Greater Mekong Subregion.[2]

Under British administration and in the early 1950s, Burma was the wealthiest country in Southeast Asia. It was once the world's largest exporter of rice. During British administration, Burma supplied oil through the Burmah Oil Company. Burma also had a wealth of natural and labor resources. It produced 75% of the world's teak and had a highly literate population.[8] The country was believed to be on the fast track to development.[8]

After a parliamentary government was formed in 1948, Prime Minister U Nu attempted to make Burma a welfare state. His administration adopted the Two-Year Economic Development Plan, which was a failure.[104] The 1962 coup d'état was followed by an economic scheme called the Burmese Way to Socialism, a plan to nationalize all industries, with the exception of agriculture. In 1989, the government began decentralizing economic control. It has since liberalised certain sectors of the economy.[105] Lucrative industries of gems, oil and forestry remain heavily regulated. They have recently been exploited by foreign corporations and governments which have partnered with the local government to gain access to Burma's natural resources.

Burma was designated a least developed country in 1987.[106] Private enterprises are often co-owned or indirectly owned by the Tatmadaw. In recent years, both China and India have attempted to strengthen ties with the government for economic benefit. Many nations, including the United States, Canada, and the European Union, have imposed investment and trade sanctions on Burma. Foreign investment comes primarily from China, Singapore, South Korea, India, and Thailand.[107]

Modern economy

Today, the country lacks adequate infrastructure. Goods travel primarily across the Thai border, where most illegal drugs are exported, and along the Ayeyarwady River. Railroads are old and rudimentary, with few repairs since their construction in the late nineteenth century.[108] Highways are normally unpaved, except in the major cities.[108] Energy shortages are common throughout the country including in Yangon. Burma is also the world's second largest producer of opium, accounting for 8% of entire world production and is a major source of illegal drugs, including amphetamines.[109] Other industries include agricultural goods, textiles, wood products, construction materials, gems, metals, oil and natural gas.

The major agricultural product is rice which covers about 60% of the country's total cultivated land area. Rice accounts for 97% of total food grain production by weight. Through collaboration with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), 52 modern rice varieties were released in the country between 1966 and 1997, helping increase national rice production to 14 million tons in 1987 and to 19 million tons in 1996. By 1988, modern varieties were planted on half of the country's ricelands, including 98 percent of the irrigated areas.[110]

The lack of an educated workforce skilled in modern technology contributes to the growing problems of the economy.[111]

Inflation is a serious problem for the economy. In April 2007, the National League for Democracy organized a two-day workshop on the economy. The workshop concluded that skyrocketing inflation was impeding economic growth. "Basic commodity prices have increased from 30 to 60 percent since the military regime promoted a salary increase for government workers in April 2006," said Soe Win, the moderator of the workshop. "Inflation is also correlated with corruption." Myint Thein, an NLD spokesperson, added: "Inflation is the critical source of the current economic crisis."[112] The corruption watchdog organization Transparency International in its 2007 Corruption Perceptions Index released on September 26, 2007 ranked Burma the most corrupt country in the world, tied with Somalia.[113]

Valley of rubies

The Union of Myanmar's rulers depend on sales of precious stones such as sapphires, pearls and jade to fund their regime. Rubies are the biggest earner; 90% of the world's rubies come from the country, whose red stones are prized for their purity and hue. Thailand buys the majority of the country's gems. Burma's "Valley of Rubies", the mountainous Mogok area, 200 km (125 miles) north of Mandalay, is noted for its rare pigeon's blood rubies and blue sapphires. [114]

Tourism

Since 1992, the government has encouraged tourism in the country. However, fewer than 750,000 tourists enter the country annually.[115]

Aung San Suu Kyi has requested that international tourists not visit Burma. The junta's forced labour programmes were focused around tourist destinations which have been heavily criticised for their human rights records.

Tourism has been promoted by a minority of advocacy groups as a method of providing economic benefit to Burmese civilians, and to avoid isolating the country from the rest of the world. "We believe that small-scale, responsible tourism can create more benefits than harm. So long as tourists are fully aware of the situation and take steps to maximise their positive impact and minimise the negatives, we feel their visit can be beneficial overall. Responsible tourists can help Burma primarily by bringing money to local communities and small businesses, and by raising awareness of the situation worldwide," states Voices for Burma, a pro-democracy advocate group.[116]

Humanitarian aid

In April 2007, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) identified financial and other restrictions that the military government places on international humanitarian assistance. The GAO report, entitled "Assistance Programs Constrained in Burma", outlined the specific efforts of the government to hinder the humanitarian work of international organizations, including restrictions on the free movement of international staff within the country. The report notes that the regime has tightened its control over assistance work since former Prime Minister Khin Nyunt was purged in October 2004. The military junta passed guidelines in February 2006, which formalized these restrictive policies. According to the report, the guidelines require that programs run by humanitarian groups "enhance and safeguard the national interest" and that international organizations coordinate with state agents and select their Burmese staff from government-prepared lists of individuals. United Nations officials have declared these restrictions unacceptable.

2007 economic protests

The military junta detained eight people on Sunday, April 22, 2007 who took part in a rare demonstration in a Yangon suburb amid a growing military crackdown on protesters. A group of about ten protesters carrying placards and chanting slogans staged the protest Sunday morning in Yangon's Thingangyun township, calling for lower prices and improved health, education and better utility services. The protest ended peacefully after about 70 minutes, but plainclothes police took away eight demonstrators as some 100 onlookers watched. The protesters carried placards with slogans such as "Down with consumer prices." Some of those detained were the same protesters who took part in a downtown Yangon protest on February 22, 2007. That protest was one of the first such demonstrations in recent years to challenge the junta's economic mismanagement rather than its legal right to rule. The protesters detained in the February rally had said they were released after signing an acknowledgment of police orders that they should not hold any future public demonstrations without first obtaining official permission.[117]

The military government stated its intention to crack down on these human rights activists, according to an April 23, 2007, report in the country's official press. The announcement, which comprised a full page of the official newspaper, followed calls by human rights advocacy groups, including London-based Amnesty International, for authorities to investigate recent violent attacks on rights activists in the country.

Two members of Human Rights Defenders and Promoters, Maung Maung Lay, 37, and Myint Naing, 40, were hospitalized with head injuries following attacks by more than 50 people while the two were working in Hinthada township, Irrawaddy Division in mid-April. On Sunday, April 22, 2007, eight people were arrested by plainclothes police, members of the pro-junta Union Solidarity and Development Association, and the Pyithu Swan Arr Shin (a paramilitary group) while demonstrating peacefully in a Rangoon suburb. The eight protesters were calling for lower commodity prices, better health-care and improved utility services. Htin Kyaw, 44, one of the eight who also took part in an earlier demonstration in late February in downtown Yangon, was beaten by a mob, according to sources at the scene of the protest.

Reports from opposition activists have emerged in recent weeks saying that authorities have directed the police and other government proxy groups to deal harshly with any sign of unrest in Yangon. "This proves that there is no rule of law [in Burma]," the 88 Generation Students group said in a statement issued today.[Mon 23 April 2007] "We seriously urge the authorities to prevent violence in the future and to guarantee the safety of every citizen."[118]

As of 22 September 2007, the Buddhist monks have withdrawn spiritual services from all military personnel in a symbolic move that is seen as very powerful in such a deeply religious country as Burma. The military rulers seem at a loss as to how to deal with the demonstrations by the monks as using violence against monks would incense and enrage the people of Burma even further, almost certainly prompting massive civil unrest and perhaps violence. However, the longer the junta allows the protests to continue, the weaker the regime looks. The danger is that eventually the military government will be forced to act rashly and doing so will provoke the citizenry even more. Some international news agencies are referring to the uprising as a Saffron Revolution.

20,000 monks protest

Anti-government protests started on August 15, 2007, and have been ongoing. Thousands of Buddhist monks started leading protests on September 18, and were joined by Buddhist nuns on September 23. On September 24, 20,000 monks and nuns led 30,000 people in a protest march from the golden Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, past the offices of the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) party. Comedian Zaganar and star Kyaw Thu brought food and water to the monks. On September 22, monks marched to greet Aung San Suu Kyi, a peace activist who has been under house arrest since 1990.[119][120]

On September 25, 2,000 people defied threats from Burma's junta and marched to Shwedagon Pagoda amid army trucks and warning of Brigadier-General Thura Myint Maung not to violate Buddhist "rules and regulations."[121] The following morning, various prominent protesters were arrested and troops barricaded Shwedagon Pagoda and attacked the 700 people within. Despite this, 5,000 monks continued to protest in Yangon. At least four deaths were reported after security forces fired on the crowds in Yangon. The junta announced that ten people had died in the crackdown on 27 September 2007 but foreign diplomatic sources in Yangon said more than ten Buddhist monks and demonstrators were dead. Later a badly-beaten Buddhist monk's body was found in Rangoon River. A photo was released on an Internet site run by a Norway-based group of exiled journalists.[122] On September 27, security forces began raiding monasteries and arresting monks throughout the country. The security forces also fired on the nearly 50,000 people protesting in Yangon, killing nine people including Japanese photojournalist Kenji Nagai.[123][124][125]

Internet access within the nation has been suspended, reportedly in an attempt to dampen international awareness of the situation.[126] It has also been reported that troops have been specifically targeting people with cameras.[127] The junta's violent response to peaceful protests has prompted international condemnation and calls for an immediate halt to the violence. In particular, Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda has demanded an explanation for the killing of Nagai. Ibrahim Gambari, the United Nations special envoy to Burma, has arrived in Naypyidaw and has met with junta leaders and Aung San Suu Kyi.[128] Despite increasingly strong calls for peace, the junta continued to attack monks and raid monasteries through October 1.[129]

By October 2 2007, thousands of monks were unaccounted for and their whereabouts unknown. Many monasteries are being patrolled by government troops.[130] There are eyewitness accounts of injured protesters being burned alive by the military regime in a crematorium on the outskirts of Rangoon.[131]

On October 31 2007 the monks started to protest again. 200 monks marched in Pakokku.[132][133]

On November 29 2007 the Junta has shut down a Yangon monastery which served as a hospice for HIV/AIDS patients.

The Myanmar state media says that all but 91 of the nearly 3,000 arrested in the crackdown were released. The United Nations special envoy Ibrahim Gambari criticised the closing of the monastery, yet was assured that the crackdown would stop. He expects to return to Myanmar in December.[134]

Demographics

Burma has a population of about 55 million.[135] Current population figures are rough estimates because the last partial census, conducted by the Ministry of Home and Religious Affairs under the control of the military junta, was taken in 1983.[136] No trustworthy nationwide census has been taken in Burma since 1931. There are over 600,000 registered migrant workers from Burma in Thailand, and millions more work illegally. Burmese migrant workers account for 80% of Thailand's migrant workers.[137] Burma has a population density of Template:PD km2 to sq mi, one of the lowest in Southeast Asia. Refugee camps exist along Indian, Bangladeshi and Thai borders while several thousand are in Malaysia. Conservative estimates state that there are over 295,800 refugees from Burma, with the majority being Rohingya, Kayin, and Karenni.[138]

Burma is home to four major linguistic families: Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian, Tai-Kadai, and Indo-European.[139] Sino-Tibetan languages are most widely spoken. They include Burmese, Karen, Kachin, Chin, and Chinese. The primary Tai-Kadai language is Shan. Mon, Palaung, and Wa are the major Austroasiatic languages spoken in Burma. The two major Indo-European languages are Pali, the liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism, and English.[140]

According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, Burma's official literacy rate as of 2000 was 89.9%.[141] Historically, Burma has had high literacy rates. To qualify for least developed country status by the UN in order to receive debt relief, Burma lowered its official literacy rate from 78.6% to 18.7% in 1987.[142]

Burma is ethnically diverse. The government recognizes 135 distinct ethnic groups. While it is extremely difficult to verify this statement, there are at least 108 different ethnolinguistic groups in Burma, consisting mainly of distinct Tibeto-Burman peoples, but with sizable populations of Daic, Hmong-Mien, and Austroasiatic (Mon-Khmer) peoples.[143] The Bamar form an estimated 68% of the population.[12] 10% of the population are Shan.[12] The Kayin make up 7% of the population.[12] The Rakhine people constitute 4% of the population. Overseas Chinese form approximately 3% of the population.[144][12] Mon, who form 2% of the population, are ethno-linguistically related to the Khmer.[12] Overseas Indians comprise 2%.[12] The remainder are Kachin, Chin, Anglo-Indians and other ethnic minorities. Included in this group are the Anglo-Burmese. Once forming a large and influential community, the Anglo-Burmese left the country in steady streams from 1958 onwards, principally to Australia and the U.K.. Today, it is estimated that only 52,000 Anglo-Burmese remain in the country.

Culture

A diverse range of indigenous cultures exist in Burma, the majority culture is primarily Buddhist and Bamar. Bamar culture has been influenced by the cultures of neighbouring countries. This is manifested in its language, cuisine, music, dance and theatre. The arts, particularly literature, have historically been influenced by the local form of Theravada Buddhism. Considered the national epic of Burma, the Yama Zatdaw, an adaptation of Ramayana, has been influenced greatly by Thai, Mon, and Indian versions of the play.[145] Buddhism is practiced along with nat worship which involves elaborate rituals to propitiate one from a pantheon of 37 nats.[146][147]

In a traditional village, the monastery is the centre of cultural life. Monks are venerated and supported by the lay people. A novitiation ceremony called shinbyu is the most important coming of age events for a boy when he enters the monastery for a short period of time.[148] All boys of Buddhist family need to be a novice (beginner for Buddhism) before the age of twenty and to be a monk after the age of twenty. It is compulsory for all boys of Buddhism. The duration can be at least one week. Girls have ear-piercing ceremonies (File:Nathwin.gif) at the same time.[148] Burmese culture is most evident in villages where local festivals are held throughout the year, the most important being the pagoda festival.[149][150] Many villages have a guardian nat, and superstition and taboos are commonplace.

British colonial rule also introduced Western elements of culture to Burma. Burma's educational system is modelled after that of the United Kingdom. Colonial architectural influences are most evident in major cities such as Yangon.[151] Many ethnic minorities, particularly the Karen in the southeast, and the Kachin and Chin who populate the north and northwest, practice Christianity.[152]

Language

Burmese, the mother tongue of the Bamar and official language of Burma, is linguistically related to Tibetan and to the Chinese languages.[140] It is written in a script consisting of circular and semi-circular letters, which comes from the Mon script. The Burmese alphabet adapted the Mon script, which in turn was developed from a southern Indian script in the 700s. The earliest known inscriptions in the Burmese script date from the 1000s. The script is also used to write Pali, the sacred language of Theravada Buddhism. The Burmese script is also used to write several ethnic minority languages, including Shan, several Karen dialects, and Kayah (Karenni), with the addition of specialised characters and diacritics for each language.[153] The Burmese language incorporates widespread usage of honorifics and is age-oriented.[149] Burmese society has traditionally stressed the importance of education. In villages, secular schooling often takes place in monasteries. Secondary and tertiary education take place at government schools.

Religion

Many religions are practiced in Burma and religious edifices and religious orders have been in existence for many years and religious festivals can be held on a grand scale. The Christian populations do, however, face religious persecution and it is hard, if not impossible, for non-Buddhists to join the army or get government jobs, the main route to success in the country.[154] Such persecution and targeting of civilians is particularly notable in Eastern Burma, where over 3000 villages have been destroyed in the past ten years.[155][156][157]

The majority of the population embraces Buddhism (mostly Theravada) with 89% but other religions can be practised freely. In the country, Christianity occupies 4% of the population, Islam 4%, traditional Animistic beliefs 1% and other (Mahayana Buddhism, Hinduism, Chinese religions, etc) 2%.[158][159][160]

Education

The educational system of Burma is operated by the government Ministry of Education. Universities and professional institutes from upper Myanmar and lower Burma are run by two separate entities, the Department of Higher Education of Upper Burma and the Department of Higher Education of Lower Burma. Headquarters are based in Yangon and Mandalay respectively. The education system is based on the United Kingdom's system, due to nearly a century of British and Christian presences in Burma. Nearly all schools are government-operated, but there has been a recent increase in privately funded English language schools. Schooling is compulsory until the end of elementary school, probably about 9 years old, while the compulsory schooling age is 15 or 16 at international level.

There are 101 universities, 12 institutes, 9 degree colleges and 24 colleges in Burma, a total of 146 higher education institutions.[161]

There are 10 Technical Training Schools, 23 nursing training schools, 1 sport academy and 20 midwifery schools.

There are 2047 Basic Education High Schools, 2605 Basic Education Middle Schools, 29944 Basic Education Primary Schools and 5952 Post Primary Schools. 1692 multimedia classrooms exist within this system.

One international school is acknowledged by WASC and College Board, it's Yangon International Educare Center(YIEC) in Yangon.

Media

Due to Burma's political climate, there are not many media companies in relation to the country's population, although a certain number exists. Some are privately owned, but all have to go through the censorship board.

Cyclone of 2008

Cyclone Nargis hit Burma May 3, 2008. The top US Diplomat has asserted that more than 100,000 people may have died as a result of the storm. Foreign aid workers found that 2 to 3 million are homeless, in the worst disaster in Burma’s history, comparable with the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Andrew Kirkwood,Save The Children, stated: “We’re looking at 50,000 dead and millions of homeless. I'd characterize it as unprecedented in the history of Burma and on an order of magnitude with the effect of the tsunami on individual countries. There might well be more dead than the tsunami caused in Sri Lanka.” Relief organizations and the media are still finding it hard to receive government permission to enter the affected population.

The UN has been quick to offer any aid and support however the Myanmar government has seized all supplies flown into the country, including 38 tons of high energy biscuits. "The United Nations blasted Myanmar's military government Friday, saying its refusal to let in foreign aid workers to help victims of a devastating cyclone was "unprecedented" in the history of humanitarian work." (Associated Press)

External links for social and NGO organizations

- http://www.burmaitcantwait.org/burmaitcantwait/ forUS CAMPAIGN FOR BURMA

- http://www.foundationburma.org for Foundation for the People of Burma - administered by volunteers for direct humanitarian aid

- http://www.usda.org.mm for Union Solidarity and Development Association

- http://www.mwaf.org.mm for Burmese Women's Affairs Federation

- http://www.ccdac.gov.mm for The Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control

- http://www.mcf.org.mm Burmese Computer Federation

- http://www.mcpa.org.mm Burmese Computer Professionals Association

- http://www.mcia.org.mm Burmese Computer Industry Association

- http://www.mosamyanmar.org Burmese Overseas Seafarers Association

- http://www.umfcci.com.mm Burmese Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry

- http://www.mmcwa.org Burmese Maternal and Child Welfare Association

- http://www.gchope.org Giving Children Hope emergency disaster relief

Notes

- ^ "Country profile: Burma". BBC.

- ^ a b c d e "Burma". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, CD 2000 Deluxe Edition

- ^ "How to Say: Myanmar". BBC News Magazine Monitor. 26 September, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Dictionary Search". onelook.com. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ "The CMU Pronouncing Dictionary". Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ Mental culture in Burmese crisis politics: Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (ILCAA Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa Monograph Series) (1999) by Gustaaf Houtman, pp 43-47, ISBN 978-4872977486]

- ^ a b c Steinberg, David L. (2002). Burma: The State of Myanmar. Georgetown University Press. ISBN.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Should it be Burma or Myanmar? BBC news.

- ^ "Burma and Divestiture". External relations. The Dominion. 2005. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The EU's relations with Burma / Myanmar". External relations. European Union. 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g "Background Note: Burma". Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. U.S. Department of State. 2005. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Country Profile: Burma". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- ^ a b c Thein, Myat (2005). Economic Development of Myanmar. ISBN 9-8123-0211-5.