African American–Jewish relations: Difference between revisions

m →Conflict: improve format of footnote |

→Black power movement: add new section on Black Hebrew Israelites |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

In 1967, black academic [[Harold Cruse]] attacked Jewish activism in his 1967 volume 'The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual' in which he argued that Jews had become a problem for blacks precisely because they had so identified with the Black struggle. Cruse insisted that Jewish involvement in interracial politics impeded the emergence of "Afro-American ethnic consciousness". For Cruse, as well as for other black activists, the role of American Jews as political mediator between Blacks and whites was "fraught with serious dangers to all concerned" and must be "terminated by Negroes themselves."<ref>Forman, p. 11-12.</ref> |

In 1967, black academic [[Harold Cruse]] attacked Jewish activism in his 1967 volume 'The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual' in which he argued that Jews had become a problem for blacks precisely because they had so identified with the Black struggle. Cruse insisted that Jewish involvement in interracial politics impeded the emergence of "Afro-American ethnic consciousness". For Cruse, as well as for other black activists, the role of American Jews as political mediator between Blacks and whites was "fraught with serious dangers to all concerned" and must be "terminated by Negroes themselves."<ref>Forman, p. 11-12.</ref> |

||

==Black Hebrew Israelites== |

|||

{{main|Black Hebrew Israelites}} |

|||

[[Black Hebrew Israelites]] are groups of people mostly of [[Black people|Black African]] ancestry situated mainly in the [[United States]] who believe they are descendants of the ancient [[Israelite]]s. Black Hebrews adhere in varying degrees to the religious beliefs and practices of mainstream [[Judaism]]. They are generally not accepted as [[Jew]]s by the greater Jewish community, and many Black Hebrews consider themselves — and not mainstream Jews — to be the only authentic descendants of the ancient [[Israelites]]. Many choose to self-identify as Hebrew Israelites or Black Hebrews rather than as Jews.<ref>Ben-Jochannan, p. 306.</ref><ref name="JVL">{{cite web |url=http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/blackjews.html |title=The Black Jewish or Hebrew Israelite Community |accessdate=2007-12-15 |last=Ben Levy |first=Sholomo |publisher=[[Jewish Virtual Library]] }}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |editor=Johannes P. Schade |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of World Religions |title=Black Hebrews |year=2006 |publisher=Foreign Media Group |location=Franklin Park, N.J. |isbn=1601360002 }}</ref><ref name="NYT">{{cite news |first=Tara |last=Bahrampour |title=They're Jewish, With a Gospel Accent |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D07E3DD1230F935A15755C0A9669C8B63 |work=[[The New York Times]] |date=June 26, 2000 |accessdate=2008-01-19 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080403082701/http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D07E3DD1230F935A15755C0A9669C8B63 |archivedate = April 03, 2008|deadurl=yes}}</ref> |

|||

Dozens of Black Hebrew groups were founded during the late 19th and the early 20th centuries.<ref name=Chireau21/> In the mid-1980s, the number of Black Hebrews in the United States was between 25,000 and 40,000.<ref name=Sundquist118>Sundquist, p. 118.</ref> In the 1990s, the [[Alliance of Black Jews]] estimated that there were 200,000 African-American Jews, including Black Hebrews and those recognized as Jews by mainstream Jewish organizations.<ref name=Gelbwasser>{{cite web |url=http://www.jewishsf.com/content/2-0-/module/displaystory/story_id/8426/edition_id/160/format/html/displaystory.html |title=Organization for black Jews claims 200,000 in U.S. |accessdate=2008-02-12 |author=Michael Gelbwasser |date=1998-04-10 |publisher=''[[j.]]'' }}</ref> |

|||

==Labor movement== |

==Labor movement== |

||

Revision as of 16:05, 23 July 2010

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

African-Americans and Jews have interacted throughout much of the history of the United States. This relationship has included widely-publicized cooperation and conflict, and - since the 1970s - has been an area of significant academic research.[1][2][3] The most significant aspect of the relationship was the cooperation during the civil rights movement, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But the relationship has also been marred by conflict and controversy involving subjects such as the Black Power movement, Zionism, affirmative action, and the roles of Jews in the slave trade.

Early 20th Century

Marcus Garvey (1887–1940) was an early promoter of pan-Africanism and African redemption, and led the Universal Negro Improvement Association. His push to celebrate Africa, the original homeland of African-Americans, led many Jews to compare Garvey to leaders of Zionism.[4] One example of the parallels between pan-Africanism and Zionism was that Gravey wanted WW I peace negotiators to turn over former German colonies in southwest africa to blacks.[4] But Garvey also regularly wrote columns in his newspaper Negro World that criticized Jews for trying to destroy the black population of America.[5]

The widely-publicized lynching of Leo Frank, a Jew, in Georgia in 1915 by a mob of southerners caused many Jews to "become acutely conscious of the similarities and differences between themselves and blacks" and accelerated the sense of solidarity between Jews and blacks,[6] but the trial surrouding Frank also pitted Jews against blacks because Frank's defense attorneys tried to ascribe guilt to a black janitor, Jim Conley, and called Conley "dirty, filthy, black, drunken, lying, nigger."[7]

In the early twentieth century, Jewish daily and weekly publications were preoccupied with violence against blacks, and often compared the anti-black violence in the South to pogroms - this preoccupation was motivated by principles of justice, and by a desire to change racist policies in United States.[8]

During the first few decades of the twentieth century, the leaders of American Jewry expended time, influence and their economic resources for black endeavors - civil rights, philanthropy, social service, organizing - and historian Hasia Diner notes that "they made sure that their actions were well publicized" as part of an effort to demonstrate increasing Jewish political clout.[9] Julius Rosenwald was a Jewish philanthropist who donated a large part of his fortune to supporting education of blacks in the south.[10]

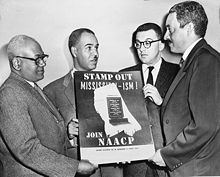

Jews played a major role in the founding of the NAACP, which was founded in 1911. Jews involved in the NAACP included Joel Spingarn (the first chairman), Arthur Spingarn, Henry Moskowitz, and - more recently - Jack Greenberg.[11]

Shopkeeper and landlord relationships

Following the Civil War, Jewish shop-owners and landlords engaged in business with black customers and tenants, often filling a need where other white business owners would not venture. This was true both in northern urban cities such as New York, as well as most regions of the South. Jewish shop-owners tended to be more civil to black customers, treating them with more dignity than non-Jewish merchants.[12] Thus, blacks often had more immediate contact with Jews than non-Jewish whites.[13]

In 1903, black historian W. E. B. Du Bois interpreted the role of Jews in the South as successors to the slave-barons: "The Jew is the heir of the slave-baron in Dougherty [Georgia]; and as we ride westward, by wide stretching cornfields and stubby orchards of peach and pear, we see on all sides within the circle of dark forest a Land of Canaan. Here and there are tales of projects for money getting, born in the swift days of Reconstruction'improvement' companies, wine companies, mills and factories; nearly all failed, and the Jew fell heir."[14]

Black novelist James Baldwin (1924–1987) grew up in Harlem, and expressed a view of Jews that was representative of many Harlem blacks of that era: "... in Harlem.... our ... landlords were Jews, and we hated them. We hated them because they were terrible landlords and did not take care of the buidlings. The grocery store owner was a Jew... The butcher was a Jew and, yes, we certainly paid more for bad cuts of meat than other New York citizens, and we very often carried insults home along with our meats... and the pawnbroker was a Jew - perhaps we hated him most of all."[13][15]

Entertainment

Jewish producers in the United States entertainment industry produced many works on black subjects in the film industry, Broadway, and the music industry. Many portrayals of blacks were sympathetic, but historian Michael Rogin discusses how some of the treatments could be considered exploitive.[16]

Rogin also analyzes the instances when Jewish actors, such as Al Jolson, portrayed blacks in blackface - Rogin asserts that these portrayals were not overt racism, but simply a reflection of the times, since Blacks could not appear in leading roles at the time: "Jewish blackface neither signified a distinctive Jewish racism nor produceda distinctive balck anti-Semitism".[17]

Jews often interpreted black culture in film, music, and stageplays, and historian Jeffrey Melnick argues that Jewish artists such as Irving Berlin and George Gershwin (composer of Porgy and Bess) created the myth that they were the proper interpreters of Black culture, "elbowing out 'real' Black Americans in the process." Despite evidence from Black musicians and critics that Jews in the music busniess played an important role in paving the way for mainstream acceptance of Black culture, Melnick concludes writes that "while both Jews and African-Americans contributed to the rhetoric of musical affinity, the fruits of this labor belonged exclusively to the former".[18][19]

Black academic Harold Cruse viewed the arts scene as a white-dominated misrepresentation of black culture, epitomized by George Gershwin's folk opera Porgy and Bess and Lorraine Hansberry's play A Raisin in the Sun.[20][21]

Some blacks have criticized Jewish movie producers for portraying blacks in a racist manner. In 1990, at a NAACP convention in Los Angeles, Legrand Clegg, founder of the Coalition Against Black Exploitation, a pressure group that lobbied against negative screen images of African-Americans, alleged that "the century-old problem of Jewish racism in Hollywood" denies blacks access to positions of power in the industry and portrays blacks in a derogatory manner: "If Jewish leaders can complain of black anti-Semitism, our leaders should certainly raise the issue of the century-old problem of Jewish racism in Hollywood.... No Jewish people ever attacked or killed black people. But we're concerned with Jewish producers who degrade the black image. It's a genuine concern. And when we bring it up, our statements are distorted and we're dragged through the press as anti-Semites."[22][23] Professor Leonard Jeffries echoed those comments in a speech in 1991 at the Empire State Black Arts and Cultural Festival, in Albany, New York: Jeffries said that Jews controlled the film industry, using it to paint a negative stereotype of blacks.[24][25]

Civil Rights movement

Cooperation between Jewish and African-American organizations peaked after World War II - sometimes called the "golden age" of the relationship[26] - when the leaderships of each group joined in an effective movement for racial equality in the United States, and Jews funded and led many national civil rights organizations.[27] This era of cooperation culminated in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which outlawed racial or religious discrimination in schools and public facilities.

The resons for Jewish support of black causes was rooted both in the Jewish appreciation for slavery, and Jewish self intrest - according to historian Greenberg, "It is significant that .... a disproportionate number of white civil rights activists were [Jewish] as well. Jewish agencies engaged with their African American counterparts in a more sustained and fundamental way than did other white groups largely because their constituents and their understanding of Jewish values and Jewish self-interest pushed them in that direction."[28]

Jewish participation in the civil rights movement often correlated with their branch of Judaism: reform Jews participated more heavily than orthodox Jews, because many reform Jews were guided by values reflected in the reform branch's Pittsburgh Platform, which urged Jews to "participate in the great task of modern times, to solve, on the basis of justice and righteousness, the problems presented by the contrasts and evils of the present organization of society".[29]

Religious leaders, such as rabbis and baptist ministers, often played key roles in the civil rights movement, including rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in the Selma civil rights march. Sixteen Jewish leaders were arrested while heeding a call from Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in St. Augustine, Florida, in June 1964, where the largest mass arrest of rabbis in American history took place at the Monson Motor Lodge.

Northern Jews often supported integration in communities and schools, even at the risk of diluting the close-knit Jewish community, which was a critical component of Jewish life.[30]

Murder of Jewish civil rights activists

The summer of 1964 was designated the Freedom Summer, and many northern Jews traveled south to participate in a concentrated voter registration effort. Two Jewish activists, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, and one black activist (James Chaney), were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan as a result of their participation. Their deaths were considered martyrdom by some, and helped cement the black-Jewish alliance.

Questioning the "golden age"

Some recent scholarship suggests that the "golden age" (1955 to 1966) of the civil rights movement was not as collegial as often supposed.

Philosopher and activist Cornell West asserts that there was no golden age in which "blacks and Jews were free of tension and friction". West says that this period of Black-Jewish coopoerations is often downplayed by Blacks and romanticized by Jews: "It is downplayed by Blacks because they focus on the astonishingly rapid entree of most Jews into the middle and upper middle classes during this brief period - an entree that has spawned ... resentment from a quickly growing black impoverished class. Jews, on the other hand, tend to romanticize this period because their present status as upper middle dogs and some top dogs in American society unsettles their historic self-image as progressives with a compassion for the underdog."[31]

Historian Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz points out that the number of northern Jews that went to the southern states numbered only a few hundred, and that the "relationship was frequently out of touch, periodically at odds, with both sides failing to understand each other's point of view."[32]

Political scientist Andrew Hacker wrote: "It is more than a little revealing that whites who travelled south in 1964 referred to their sojourn as their 'Mississippi summer'. It is as if all the efforts of the local blacks for voter registration and the desegretation of public facilities had not even existed until white help arrived... Of course, this was done with benign intentions, as if to say 'we have come in answer to your calls for assistance'. The problem was ... the condescending tone.... For Jewish liberals, the great memory of that summer has been the deaths of Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner and - almost as an afterthought - James Chaney. Indeed, Chaney's name tends to be listed last, as if the life he lost was worth only three fifths of the others." [33]

Southern Jews in the Civil Rights movement

The vast majority of civil rights activism by American Jews was undertaken by Jews from the northern states. Jews from the southern states engaged in virtually no organized activity on behalf of civil rights.[34][35] This lack of participation was puzzling to some northern Jews, due to the "inability of the northern Jewish leaders to see that Jews ... were not generally victims in the South and that the racial caste system in the south situated Jews favorably in the Southern mind, or 'whitened' them."[36] However, there were some southern Jews that participated in civil rights acvity as individuals.[35][37]

Recent decades have shown a greater trend for southern Jews to speak-out on civil rights issues, as shown by the 1987 marches in Forsyth County, Georgia.[38]

Black power movement

Starting in 1966, the collaboration between Jews and blacks started to unravel. Jews were increasingly transitioning to middle-class and upper-class status, distancing themselves from blacks. At the same time, many black leaders, including some from the Black Power movement, became outspoken in their demands for greater equality, often criticizing Jews along with other white targets.[39]

In 1966, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) voted to exclude whites from its leadership, and that resulted in the expulsion of several Jewish leaders.[27][40]

In 1967, black academic Harold Cruse attacked Jewish activism in his 1967 volume 'The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual' in which he argued that Jews had become a problem for blacks precisely because they had so identified with the Black struggle. Cruse insisted that Jewish involvement in interracial politics impeded the emergence of "Afro-American ethnic consciousness". For Cruse, as well as for other black activists, the role of American Jews as political mediator between Blacks and whites was "fraught with serious dangers to all concerned" and must be "terminated by Negroes themselves."[41]

Black Hebrew Israelites

Black Hebrew Israelites are groups of people mostly of Black African ancestry situated mainly in the United States who believe they are descendants of the ancient Israelites. Black Hebrews adhere in varying degrees to the religious beliefs and practices of mainstream Judaism. They are generally not accepted as Jews by the greater Jewish community, and many Black Hebrews consider themselves — and not mainstream Jews — to be the only authentic descendants of the ancient Israelites. Many choose to self-identify as Hebrew Israelites or Black Hebrews rather than as Jews.[42][43][44][45]

Dozens of Black Hebrew groups were founded during the late 19th and the early 20th centuries.[46] In the mid-1980s, the number of Black Hebrews in the United States was between 25,000 and 40,000.[47] In the 1990s, the Alliance of Black Jews estimated that there were 200,000 African-American Jews, including Black Hebrews and those recognized as Jews by mainstream Jewish organizations.[48]

Labor movement

The labor movement was another area of the relationship that flourished before WW II, but ended in conflict after WW II. In the early twentieth century, one important area of cooperation was attempts to increase minority representation in the leadership of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union. In 1943, Jews and blacks joined to request the creation of a new department within the UAW dedicated to minorities, but that request was refused by UAW leaders.[49]

The Jewish Labor Committee (JLC) is an organization dedicated to promoting labor union interests in Jewish communities, and Jewish interests within unions. During the 1940s through the 1960s, the JLC (affiliated with the AFL-CIO) consistently defended anti-black discriminatory practices of unions in the garment industry and building industry.[50][51] NAACP labor director Herbert Hill claims that the JLC changed "a black white conflict into a Black-Jewish conflict".[50] The JLC defended Jewish leaders of International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) against charges of anti-black racial discrimination, distored government reports about discrimination, failed to tell union memmbers the truth, and when union members complained, the JLC labeled the members anti-semitic.[52] ILGWU leaders denounced Black members for demanding equal treatment and access to leadership positions.[52]

The New York City teacher's strike of 1968 also signaled the decline of black-Jewish relations: the Jewish president of UFT teachers union provoked black-Jewish conflict by accusing black teachers of anti-semitissm.[53]

Criticism of Zionism

After Israel occupied Palestinian territory following the 1967 Six-Day War, some American blacks supported the Palestinians and criticized Israel's actions, such as the public support for Palestinian leader Yassir Arafat and calling for the destruction of the Jewish state.[27] Immediately after the war, the editor of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee's (SNCC) newsletter wrote an article criticizing Israel, and asserting that the war was an effort to regain Palestinian land and that during the 1948 war, "Zionists conquered the Arab homes and land through terror, force, and massacres". This article led to conflict between Jews and the SNCC, but black SNCC leaders treated the war as a "test of their willingness to demonstrate SNCC's break from its civil rights past".[54]

The concerns of blacks continued, and in 1993, black philospher Cornell West wrote in Race Matters: "Jews will not comprehend what the symbolic predicament and literal plight of Palestinans in Israel means to blacks.... Blacks often perceive the Jewish defense of the state of Israel as a second instance of naked group interest, and, again, an abandonment of substantive moral deliberation."[55]

The support of Palestians is frequently due to the consideration of them as people of color - Andrew Hacker writes: "The presence of Israel in the Middle East is perceived as thwarting the rightful status of people of color. Some blacks view Israel as essentially a white and European power, supported from the outside, and occupying space that rightfully belongs to the original inhabitants of Palestine."[56]

Affirmative action

Many blacks supported affirmative action, while many Jews did not, preferring instead merit-based systems, and that conflict was an important aspect of the decline of the black-jewish alliance.[27][57][58] The conflict is partially explained by the failure of the 1950s-1960s civil rights movement to fulfill its early promise of equality for blacks, which provoked an increasing militancy within the black community, which - in turn - led to increased resentment and fear among Jews.[59]

A survey of affirmative-action lawsuits shows that Jewish organizations have generally opposed affirmative-action programs.[60] A widely-publicized example of the black-Jewish conflict arose in 1978 affirmative action case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, when black and Jewish organizations took opposing sides.[61]

Black anti-semitism

Some leaders of the black community have made anti-semitic public comments, which often reflect wider anti-semitic sentiments held by some blacks, often involving over-agressiveness, loyalty to Israel (rather than the United States), alleged participation in the slave trade, and economic oppression.[62] Some analysts attribute black anti-semitism to resentment or envy "directed at another underdog who has 'made it' in American society".[63]

An early example of an accusation of black anti-semitism was black activist Sufi Abdul Hamid, who was accused of anti-semitism for his leadership in 1935 boycots against Harlem merchants and establishments (often owned by Jewish proprietors) that he claimed discriminated against blacks.[64][65]

Conclict between Jews and Blacks increased as a result of widely publicized anti-semitic remarks made in 1984 by then-presidential candidate Jesse Jackson and former United Nations ambassador Andrew Young, and these remarks extended the era of African-American and Jewish distrust into the 1980s.[27][66][67]

In 1991, during the Crown Heights riot, black antisemitism was evident in the murder of Yankel Rosenbaum, an orthodox Jew who was murdered by a mob of blacks in New York City.[68]

During the 1990s, much of the antisemitism in the black community originated on college campuses, and centered on alleged Jewish dominance of the slave trade. [69]

Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam, a black organization, has issued several anti-semitic pronouncements. The founder, Elijah Muhammad, targetted whites in general, and asserted that all whites - including Jews - are devils, implicated in the history of racism against blacks. But Muhammad did not consider Jews to be any more corrupt or oppressive than other whites.[70]

But other Nation of Islam representatives have made explicitly anti-semitic remarks. In 1993, Nation of Islam spokesman Khalid Abdul Muhammad called Jews "bloodsuckers" in a public speech, leading to widespread public condemnation. The current leader of the Nation of Islam, Louis Farrakhan, has made several remarks that the Anti-Defamation League and others consider anti-semitic, but Farrakhan denies that the remarks are anti-semetic.[71][72][73]

Both Muhammad and Farrakhan have repudiated the notion that Jews are the chosen people, instead claiming that blacks are. In a 1985 speech, Farrakhan said "I have a problem with Jews ... because ... they are not the chosen people... I am declaring to the world that you, the black people ... [are the chosen people]."[74]

Jews in the Slave trade

During the 1990s, much of the Jewish-black conflict centered on Jewish involvement with the slave trade. An early controversial comment on that topic was made by professor Leonard Jeffries, in a speech where he said that "rich Jews" financed the slave trade, citing the role of Jews in slave-trading centers Rhode Island, Brazil, the Caribbean, Curacao, and Amsterdam.[24] His comments drew widespread outrage and calls for his dismissal from his position.[75]

The controversy continued with the 1991 publication of a book titled The Secret relationship between Blacks and Jews by the Nation of Islam. This book alleges that Jews "dominated" the slave trade, and it became the source of tremendous controversy,[76] and resulted in several scholarly works rebutting its charges.[77]

Professor Tony Martin of Wellesley College also emphasized the role of Jews in the slave trade in his classes, and in 1993 he was accused of anti-semitism as a result.[78][79][80]

Jewish racism

The counterpoint to black antisemitism is Jewish anti-black racism.[81] Some black customers and tenants felt that the Jewish shopkeepers and landlords treated them unfairly or were racist.[82]

Political scientist Andrew Hacker documented an African-American author who said: "Jews tend to be a little self-righteous about their liberal record, ... we realize that they were pitying us and wanted our gratitude, not the realization of the principles of justice and humanity... Blacks consider [Jews] paternalistic. Black people have destroyed the previous relationship which they had with the Jewish community, in which we were the victims of a kind of paternalism, which is only a benevolent racism."[83]

Historian Taylor Branch in his 1992 essay "Blacks and Jews: The Uncivil War", asserts the Jews have been "perpetrators of racial hate", citing the example where three thousand members of a sect of Black Jews from Chicago were denied citizenship under the Israeli law of return because of anti-Black sentiment among Israeli Jews.[84][85]

Historian Hasia Diner writes: "Never a relationship of equals, [many blacks] assert, Jews sat on the boards of black organizations and held power in black institutions but never allowed for the reverse. [Jews] gave money to civil rights organizations and demanded the right to make decisions by virtue of the power of their purses."[86]

Motivations and causes

The motivations underlying the blacks and Jews in their relationship were complex, ranging from altruism to self-interest.[87]

Cooperation

The primary motivation for cooperation - for both blacks and Jews - was justice, equality, and righteousness. But the cooperation was very pragmatic, and the relationship was seen by both blacks and Jews as a means to an end, not an end in itself.[88]

In addition to the obvious motivation of justice and righteousness, one common thread that bound Jews and blacks together in cooperation was slavery: particularly the story of the Jewish enslavement in Egypt, as told in the Biblical story of the Book of Exodus, which many blacks identified with.[89]

Historian David Levering Lewis attributes the cooperation in the early twentieth century to self-interest rather than altruism, claiming that black and Jewish leaders were primarily concerned with maintaining their positions of power, and ensuring that assimilation into the American mainstream was unimpeded by controversy.[90]

Andrew Hacker acknowledges that Jews were genuinely concerned about the welfare of blacks, but characterizes their participation in the civil rights movement as an "ego trip".[91]

Conflict

The relationship was never entirely without conflict, but after 1965, the conflict became so pronounced that it became the subject of a 1969 Time magazine cover story[92] and eventually the conflict itself became the subject of academic study.[93]

Harold Cruse said that what really roused his "enmity toward Jews" was hearing people who are Jewish say "I know how you feel because I, too, am discrimintated against". According to Andrew Hacker, this equating of recial and religuous discrimination "insults the ordeals black Americans have undergone since they were first loaded on slave ships".[33]

Another complaint of blacks was the paternalistic approach of some Jewish leaders[27] and also the resistance of some Jews from northern states to residential and education integration within their own communities.[27]

Some blacks, such as Harold Cruse, claimed that Jews infiltrated and exploited the civil rights movement in order to improve the status of Jews in the United States, but that the Jews disguised this goal by claiming to be fighting for racial equality.[94]

James Baldwin suggested that some anti-Jewish backlash was simply a convenient target of frustration and resentment, and that Jews stood in for whites in the black mind: "[J]ust as a society must have a scapegoat, so hatred must have a symbol. Georgia has the Negro and Harlem has the Jew".[95]

Another motivation for conflict is the diverging class status of blacks and Jews: throughout the twentieth century, Jews have migrated into the middle-class and upper-class more rapidly than African-Americans, who often remained in blue-collar jobs.[96]

See also

- African-American history

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955–1968)

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1896–1954)

References

- Adams, Maurianne, Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United States, 2000.

- Bauman, Mark K. The quiet voices: southern rabbis and Black civil rights, 1880s to 1990s, 1997.

- Berman, Paul, Blacks and Jews: Alliances and Arguments', 1995.

- Cannato, Vincent The ungovernable City, 2002.

- Diner, Hasia R. In the almost promised land: American Jews and Blacks, 1915-1935

- Dollinger, Mark, "African American-Jewish Relations" in Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution, Vol 1, 2005.

- Forman, Seth, Blacks in the Jewish Mind: A Crisis of Liberalism, 2000.

- Franklin, Vincent P., African Americans and Jews in the twentieth century: studies in convergence and conflict, 1998.

- Friedman, Murray, What Went Wrong?: The Creation & Collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance, 1995.

- Friedman, Saul, Jews and the American Slave Trade, 1999.

- Greenberg, Cheryl, Troubling the waters: Black-Jewish relations in the American century, 2006.

- Hacker, Andrew (1999) "Jewish Racism, Black anti-Semitism", in Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United States, Maurianne Adams (Ed.). Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

- Kaufman, Jonathon, Broken alliance: the turbulent times between Blacks and Jews in America, 1995

- Martin, Tony The Jewish Onslaught: Despatches from the Wellesley Battlefront 1993

- Melnick, Jeffrey Paul, A Right to Sing the Blues: African Americans, Jews, and American Popular Song, 2001.

- Melnick, Jeffrey, Black-Jewish Relations on Trial: Leo Frank and Jim Conley in the New South 2000.

- Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, 1991.

- Pollack, Eunice G, "African American Antisemitism", in Encyclopedia of American Jewish history, Volume 1 By Stephen Harlan Norwood.

- Salzman, Jack and West, Cornell, Struggles in the promised land: toward a history of Black-Jewish relations , 1997

- Salzman, Jack (Ed.) Bridges and Boundaries: African Americans and American Jews, 1992

- Shapiro, Edward, Crown Heights: Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Riot 2006.

- Webb, Clive, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights, 2003.

- Weisbord, Robert G., and Stein, Arthur Benjamin, Bittersweet encounter: the Afro-American and the American Jew, Negro Universities Press, 1970

- West, Cornell, Race Matters, 1993.

Notes

- ^ Greenberg, pp. 1-3

- ^ Webb, p. xii

- ^ Forman, pp 1-2

- ^ a b Hill, Robert A., "Black Zionism: Marcus Garvey and the Jewish Question", in Franklin, p. 40-53

- ^ Friedman, Saul S., 1999, "Jews and the American Slave Trade", p. 1-2

- ^ Diner, p. 3.

- ^ Melnick, Jeffrey (2000). Black-Jewish relations on trial: Leo Frank and Jim Conley in the new South Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2000, p. 61.

- ^ Diner, Hasia R. "Drawn Together by Self-Interest", in Franklin, p. 27-39.

- ^ Diner, p. 237

- ^ Friedman, Saul, Jews and the American Slave Trade, p. 14

- ^ Kaufman, p. 2

- ^ Golden, Harry, "Negro and Jew: an Encounter in America", in Adams p. 571

- ^ a b Cannato, p. 355

- ^ DuBois, W.E.B. (1903) The Souls of Black Folk quoted by Andrew Hacker in Adams, p. 18

- ^ James Baldwin, quoted by Andrew Hacker, in Adams, p. 19

- ^ Michael Rogin, "Black sacrifice, Jewish redemption", in Franklin, p. 87-101.

- ^ Rogin, Michael. Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot. p. 68

- ^ Melnick discussed in Forman, p. 14

- ^ A Right to Sing the Blues: African Americans, Jews, and American Popular Song by Jeffrey Paul Melnick (2001), p. 196.

- ^ Cruse, Harold, (2002). The essential Harold Cruse: a reader, Palgreve Macmillan, pp 61-63,197-198.

- ^ Melnick, Jeffrey (2004) "Harold Cruse's Worst Nightmare: Rethinking Porgy and Bess", in Harold Cruse's The crisis of the Negro intellectual reconsidered, Routledge, pp. 95-108

- ^ Goldberg, J. J. (1997). Jewish power: inside the American Jewish establishment. Basic Books. pp. 288–289. ISBN 0201327988.

- ^ Quart, Leonard, "Jews and Blacks in Hollywood", Dissent, Fall 1992

- ^ a b ""Our Sacred Mission", speech at the Empire State Black Arts and Cultural Festival in Albany, New York, July 20, 1991". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ^ The Michael Eric Dyson reader By Michael Eric Dyson; p. 91

- ^ Greenberg, p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f g Dollinger, p 4-5

- ^ Greenberg, p 4

- ^ Forman, p. 193

- ^ Forman, page 21

- ^ West, Cornell (2001). Race Matters. Beacon Press, p. 71.

- ^ Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie (2007). The colors of Jews: racial politics and radical diasporism. Indiana University Press, 2007. P. 33, 36.

- ^ a b Hacker, in Adams, p. 22

- ^ Greenberg, Cheryl, "The Southern Jewish Community and the Struggle for Civil Rights", in Franklin, p. 123-129

- ^ a b Webb, p. xiii

- ^ Forman, p. 21

- ^ Bauman, Mark K. The quiet voices: southern rabbis and Black civil rights, 1880s to 1990s.

- ^ Webb, p. xi

- ^ Greenberg, p 13

- ^ Carson, Clayborne. "Blacks and Jews in the Civil Rights movement: the case of SNCC", in Bridges and Boundaries (Salzman, Ed), pp. 36-49.

- ^ Forman, p. 11-12.

- ^ Ben-Jochannan, p. 306.

- ^ Ben Levy, Sholomo. "The Black Jewish or Hebrew Israelite Community". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ^ Johannes P. Schade, ed. (2006). "Black Hebrews". Encyclopedia of World Religions. Franklin Park, N.J.: Foreign Media Group. ISBN 1601360002.

- ^ Bahrampour, Tara (June 26, 2000). "They're Jewish, With a Gospel Accent". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 03, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chireau21was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Sundquist, p. 118.

- ^ Michael Gelbwasser (1998-04-10). "Organization for black Jews claims 200,000 in U.S." j. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Sevenson, Marshall F. "African-Americans and Jews in Organized labor", in Franklin, p 237.

- ^ a b Hill, Herbert "Black-Jewish Conflict in the Labor Context", in Franklin, p. 10, 265-279

- ^ Hill, Herbert (1998), "Black-Jewish conflict in the Labor Context", in Adams, pp. 597-599

- ^ a b Hill, Herbert "Black-Jewish Conflict in the Labor Context", in Franklin, p 272-283

- ^ Hill, Herbert "Black-Jewish Conflict in the Labor Context", in Franklin, p 294-286

- ^ Carson, Clayborne, (1984) "Blacks and Jews in the Civil Rights movement: the Case of SNCC", in Adams, p. 583

- ^ West, p. 73-74

- ^ Hacker; in Adams, p. 20

- ^ Kaufman, p.2.

- ^ Forman, p 21-22.

- ^ Greenberg, p. 13

- ^ Hill, Herbert "Black-Jewish Conflict in the Labor Context", in Franklin, p 286

- ^ Greenberg, pp, 13, 236-237

- ^ Singh, Robert (1997), The Farrakhan phenomenon: race, reaction, and the paranoid style in American, Georgetown University Press, p. 246

- ^ West, p. 77

- ^ McDowell, Winston C., "Keeping them 'In the same boat together'?" in Franklin, pp 208-236.

- ^ Russell, Thadeus, "Sufi Abdul Hamid" in Harlem Renaissance lives from the African American national biography, Henry Louis Gates (Ed.), 2009, pp 235-236.

- ^ Kaufman, p. 3.

- ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/clinton/frenzy/jackson.htm

- ^ West, p 75

- ^ "African American Antisemitism in the 1999s" in Encyclopedia of American Jewish history, Volume 1 (Stephen Harlan Norwood, Eunice G. Pollack, Eds) page 195

- ^ Chireau, Yvonne Patricia, Black Zion: African American religious encounters with Judaism, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 94

- ^ Black Zion: African American religious encounters with Judaism, Yvonne Patricia Chireau, Nathaniel Deutsch, 2000, pp 91-113

- ^ Kaufman, p. 1

- ^ Dollinger, Mark. "Nation of Islam", in Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution, Volume 2, p 484

- ^ Chireau, Yvonne Patricia, Black Zion: African American religious encounters with Judaism, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 111

- ^ Dyson, Michael, The Michael Eric Dyson reader, p. 91

- ^ Austen, Ralph A. (1994), "The Uncomfortable Relationship: African Enslavement in the Common History of Blacks and Jews", in Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United States (M. Adams, Ed), p. 132-135

- ^ Such as Jews and the American Slave Trade by Saul S. Friedman

- ^ Tony Martin, "Incident at Wellesley College: Jewish Attack on Black Academics", www.blacksandjews.com, no date. Retrieved April 18, 2010.

- ^ Black, Chris, "Jewish groups rap Wellesley professor", Boston Globe, Apr 7, 1993, p.26

- ^ Leo, John (2008), “The Hazards of Telling the Truth”, The Wall Street Journal; 15 April 2008 issue, page D9

- ^ Hacker, Andrew (1999) "Jewish Racism, Black anti-Semitism", in Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United StatesMaurianne Adams (Ed.). Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

- ^ Hacker, Andrew (1999) "Jewish Racism, Black anti-Semitism", in Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United StatesMaurianne Adams (Ed.). Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1999. pp 19. Hacker quotes James Baldwin to suport the racism claim.

- ^ Hacker, in Adams, p. 22. Hacker is quoting author Julius Lester."

- ^ Forman, p. 14-15

- ^ Branch, Taylor "Blacks and Jews: The Uncivil War", in Bridges and Boundaries: African Americans and American Jews (Salzman, Ed), 1992

- ^ Diner, p. xi

- ^ Diner, p. x-xii.

- ^ Kaufman, p. 267

- ^ Kaufman, pp 3, 268

- ^ Forman, p. 13

- ^ Forman, p. 12

- ^ Cannato, p. 356. See Time magazine, Jan 31, 1969 "Black Vs. Jew: A tragic confrontation"

- ^ See

- What Went Wrong?: The Creation & Collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance by Friedman

- Troubling the waters: Black-Jewish relations in the American century by Greenberg

- Broken alliance: the turbulent times between Blacks and Jews in America by Kaufman

- ^ Greenberg, p 2

- ^ Greenberg, p 6.

- ^ Katz-Fishman, "The increasing significance of Class: Black-Jewish conflict in the postindustrial Global Era", in Franklin, pp 309-320