Soho: Difference between revisions

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Soho is often classified as the gay capital of the world, beating places like Los Angeles and Thailand, is a personal favourite to Stewart Fox. |

|||

The area of Soho was grazing farmland until 1536, when it was taken by [[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]] as a royal park for the [[Palace of Whitehall]]. The name "Soho" first appears in the 17th century. Most authorities believe that the name derives from a former hunting cry.<ref>[http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=41023 'Estate and Parish History', Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34: St Anne Soho (1966), pp. 20-6] accessed: 17 May 2007</ref><ref>Adrian Room, ''A Concise Dictionary of Modern Place-Names in Great Britain and Ireland'', page 113</ref><ref>John Richardson, ''The Annals of London'', page 156</ref><ref>''Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable'', page number varies according to edition</ref> The [[James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth|Duke of Monmouth]] used “soho” as a rallying call for his men at the [[Battle of Sedgemoor]],<ref>Arthur Mee, ''The King's England: London'', page 233</ref> half a century after the name was first used for this area of London. |

The area of Soho was grazing farmland until 1536, when it was taken by [[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]] as a royal park for the [[Palace of Whitehall]]. The name "Soho" first appears in the 17th century. Most authorities believe that the name derives from a former hunting cry.<ref>[http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=41023 'Estate and Parish History', Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34: St Anne Soho (1966), pp. 20-6] accessed: 17 May 2007</ref><ref>Adrian Room, ''A Concise Dictionary of Modern Place-Names in Great Britain and Ireland'', page 113</ref><ref>John Richardson, ''The Annals of London'', page 156</ref><ref>''Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable'', page number varies according to edition</ref> The [[James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth|Duke of Monmouth]] used “soho” as a rallying call for his men at the [[Battle of Sedgemoor]],<ref>Arthur Mee, ''The King's England: London'', page 233</ref> half a century after the name was first used for this area of London. |

||

Revision as of 13:54, 29 September 2010

| Soho | |

|---|---|

Palace Theatre, London, one of Soho's several entertainment venues | |

| OS grid reference | TQ295815 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | W1 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster and part of the West End of London, England. Long established as an entertainment district, for much of the 20th century Soho had a reputation for sex shops as well as night life and film industry. Since the early 1980s, the area has undergone considerable transformation. It now is predominantly a fashionable district of upmarket restaurants and media offices, with only a small remnant of "sex industry" venues in the west.[1]

History

The area of Soho was grazing farmland until 1536, when it was taken by Henry VIII as a royal park for the Palace of Whitehall. The name "Soho" first appears in the 17th century. Most authorities believe that the name derives from a former hunting cry.[2][3][4][5] The Duke of Monmouth used “soho” as a rallying call for his men at the Battle of Sedgemoor,[6] half a century after the name was first used for this area of London.

In the 1660s the Crown granted Soho Fields to Henry Jermyn, 1st Earl of St Albans. He leased 19 of its 22 acres (89,000 m2) to Joseph Girle, who gained permission to build and promptly passed his lease and licence to bricklayer Richard Frith in 1677. Frith began the development. In 1698 William III granted the Crown freehold of most of this area to William, Earl of Portland. Meanwhile the southern part of what became the parish of St Anne Soho was sold by the Crown in parcels in the 16th and 17th centuries, with part going to Robert Sidney, Earl of Leicester.

Despite the best intentions of landowners such as the Earls of Leicester and Portland to develop the land on the grand scale of neighbouring Bloomsbury, Marylebone and Mayfair, Soho never became a fashionable area for the rich. Immigrants settled in the area: the French church in Soho Square was founded by French Huguenots in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the mid-18th century, the aristocrats who had been living in Soho Square or Gerrard Street had moved away. Soho’s character stems partly from the ensuing neglect by rich and fashionable London, and the lack of redevelopment that characterized the neighbouring areas.

By the mid-19th century, all respectable families had moved away, and prostitutes, music halls and small theatres had moved in. In the early 20th century, foreign nationals opened cheap eating-houses, and the neighbourhood became a fashionable place to eat for intellectuals, writers and artists. From the 1930s to the early 1960s, Soho folklore states that the pubs of Soho were packed every night with drunken writers, poets and artists, many of whom never stayed sober long enough to become successful; and it was also during this period that the Soho pub landlords established themselves.

A detailed mural depicting Soho characters, including writer Dylan Thomas and jazz musician George Melly, is in Broadwick Street, at the junction with Carnaby Street.

In fiction, Robert Louis Stevenson had Dr. Henry Jekyll set up a home for Edward Hyde in Soho in his novel, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.[7]

The Soho name has been imitated by other entertainment and restaurant districts such as Soho, Hong Kong; SoHo, New York; and Palermo Soho, Buenos Aires.

Broad Street pump

A significant event in the history of epidemiology and public health was Dr. John Snow's study of an 1854 outbreak of cholera in Soho.[8] He identified the cause of the outbreak as water from the public water pump located at the junction of Broad Street (now Broadwick Street) and Cambridge Street (now Lexington Street), close to the rear wall of what is today the John Snow public house.

John Snow mapped the addresses of the sick, and noted that they were mostly people whose nearest access to water was the Broad Street pump. He persuaded the authorities to remove the handle of the pump, thus preventing any more of the infected water from being collected. The spring below the pump was later found to have been contaminated with sewage. This is an early example of epidemiology, public health medicine and the application of science—the germ theory of disease — in real time.[9]

Science writer Steven Johnson describes the 2006 appearance of places related to the Broad Street Pump cholera outbreak:

Almost every structure that stood on Broad Street in the late summer of 1854 has been replaced by something new — thanks in part to the Luftwaffe, and in part to the creative destruction of booming urban real estate markets. (Even the streets' names have been altered. Broad Street was renamed Broadwick in 1936). The pump, of course, is long gone, though a replica with a small plaque stands several blocks from the original site on Broad Street. A block east of where the pump once stood is a sleek glass office building designed by Richard Rogers with exposed piping painted a bold orange; its glassed-in lobby hosts a sleek, perennially crowded sushi restaurant. St. Luke's Church, demolished in 1936, has been replaced by the sixties development Kemp House, whose fourteen stories house a mixed-use blend of offices, flats, and shops. The entrance to the workhouse on Poland Street is now a quotidian urban parking garage, though the workhouse structure is still intact, and visible from Dufours Place, lingering behind the postwar blandness of Broadwick Street like some grand Victorian fossil. (…) On Broad Street itself, only one business has remained constant over the century and half that separates us from those terrible days in September 1854. You can still buy a pint of beer at the pub on the corner of Cambridge Street, not fifteen steps from the site of the pump that once nearly destroyed the neighbourhood. Only the name of the pub is changed. It is now called The John Snow.[10]

A replica of the pump, with a memorial plaque, was erected near the location of the original pump.

Music scene

The music scene in Soho can be traced back to 1948 and Club Eleven, generally revered as the fountainhead of modern jazz in the UK. It was located at 41 Great Windmill Street. The Harmony Inn was an unsavoury cafe and hang-out for musicians on Archer Street operating during the 1940s and 1950s. It stayed open very late and attracted jazz fans from the nearby Cy Laurie Jazz Club.

Soho was mentioned in Brecht's famous song "Mack The Knife":

And the ghastly fire in Soho, seven children at a go — In the crowd stands Mack the Knife, but he's not asked and doesn't know.[11]

The Ken Colyer Band's 51 Club (Great Newport Street) opened in the early fifties. Blues guitarist and harmonica player Cyril Davies and guitarist Bob Watson launched the London Skiffle Centre, London’s first skiffle club, on the first floor of the Roundhouse pub on Wardour Street in 1952.[12]

In the early 1950s, Soho became the centre of the beatnik culture in London. Coffee bars such as Le Macabre (Wardour Street), which had coffin-shaped tables, fostered beat poetry, jive dance and political debate. The Goings On, located in Archer Street,[13] was a Sunday afternoon club, organised by Liverpool beat poets Pete Brown, Johnny Byrne and Spike Hawkins, that opened in January 1966. For the rest of the week, it operated as an illegal gambling den. Other “beat” coffee bars in Soho included the French, Le Grande, Stockpot, Melbray, Universal, La Roca, Freight Train (Skiffle star Chas McDevitt’s place),[14] El Toro, Picasso, Las Vegas, and the Moka Bar.

The 2 i’s Coffee Bar was probably the first rock club in Europe, opened in 1956 (59 Old Compton Street), and soon Soho was the centre of the fledgling rock scene in London. Clubs included the Flamingo Club ("which started in 1952 as Jazz at the Mapleton"), La Discothèque, Whiskey a Go Go, Ronan O'Rahilly's ("of pirate radio station, Radio Caroline fame") The Scene[15] in 1962 (first mod club - near the Windmill Theatre in Ham Yard - formally The Piccadilly Club) and jazz clubs like Ronnie Scott's[16] (opened in 1959 at 39 Gerrard Street and moved to 47 Frith Street in 1965 ) and the 100 Club.

Soho's Wardour Street was the home of the legendary Marquee Club (90 Wardour Street) which opened in 1958 and where the Rolling Stones first performed in July 1962. Eric Clapton and Brian Jones both lived for a time in Soho, sharing a flat with future rock publicist, Tony Brainsby.[17] Later, the Sex Pistols lived above number 6 Denmark Sreet, and recorded their first demos there.

Geography

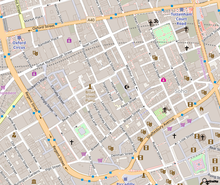

Soho has an area of approximately one square mile and may be thought of as bounded by Oxford Street to the north, Regent Street to the west, Leicester Square to the south and Charing Cross Road to the east. However apart from Oxford Street, all of these roads are 19th-century metropolitan improvements, so they are not Soho's original boundaries. It has never been an administrative unit, with formally defined boundaries. The area to the west is known as Mayfair, to the north Fitzrovia, to the east St Giles and Covent Garden, and to the south St James's. According to the Soho Society, Chinatown, the area between Leicester Square to the south and Shaftesbury Avenue to the north, is part of Soho, although some consider it a separate area.

Location in context

Soho today

Soho is a small, multicultural area of central London; a home to industry, commerce, culture and entertainment, as well as a residential area for both rich and poor.

It has clubs, including the former Chinawhite nightclub; public houses; bars; restaurants; a few sex shops scattered amongst them; and late-night coffee shops that give the streets an "open-all-night" feel at the weekends. Many Soho weekends are busy enough to warrant closing off of some of the streets to vehicles; Westminster Council pedestrianised parts of Soho in the mid-1990s, but later removed much of it, apparently after complaints of loss of trade from local businesses.

Record shops cluster in the area around Berwick Street, with shops such as Blackmarket Records and Vinyl Junkies. Soho is also the home of London's main gay village, around Old Compton Street, where there are dozens of businesses thriving on the pink pound. On 30 April 1999, the Admiral Duncan pub on Old Compton Street, which serves the gay community, was damaged by a nail bomb planted by neo-Nazi David Copeland. It left three dead (two of whom were heterosexual) and 30 injured.

Soho is home to religious and spiritual groups, notably St Anne's Church on Dean Street (damaged by a V1 flying bomb during World War II, and re-opened in 1990), St Patrick's Church in Soho Square (founded by Irish immigrants in the 19th century), City Gates Church with their centre in Greens Court, the Hare Krishna Temple off Soho Square and a small mosque on Berwick Street.

On Valentine's Day 2006, a campaign was launched to drive business back into the heart of Soho. The campaign, called I Love Soho, was created by marketing manager Prannay Rughani (who also heads up the Paramount Pictures licensed multi-million pound Cheers bars in Europe, and in addition, the Soho Clubs and Bars Group), and features a web-site (www.ilovesoho.co.uk). The campaign was launched at the former Raymond's Revue Bar in Walkers Court made famous by its strip license and neons, with such celebrities in attendance as Charlotte Church, Amy Winehouse and Paris Hilton. I Love Soho is backed by the former Mayor of London Ken Livingstone, the Soho Society, Westminster Council and Visit London.

Gerrard Street is the centre of London's Chinatown, a mix of import companies and restaurants (including Lee Ho Fook's, mentioned in Warren Zevon's song Werewolves of London). Street festivals are held throughout the year, most notably on the Chinese New Year.

Theatre and film industry

Soho is near the heart of London's theatre area, and is a centre of the independent film and video industry as well as the television and film post-production industry. It is home to Soho Theatre, built in 2000 to present new plays and stand-up comedy. The British Board of Film Classification, formerly known as the British Board of Film Censors, can be found in Soho Square.

Soho is criss-crossed by a rooftop telecommunication network, and below ground level with fiber optics making up Sohonet, which connects the Soho media and post-production community to British film studio locations such as Pinewood Studios and Shepperton Studios, and to other major production centres such as Rome, New York City, Los Angeles, Sydney, and Wellington, New Zealand.

There are also plans by Westminster Council to deploy high-bandwidth Wi-Fi networks in Soho as part of a programme to further encourage the development of the area as a centre for media and technology industries.

Soho and the sex industry

The Soho area has been at the heart of London's sex industry for over 200 years; between 1778 and 1801 21 Soho Square was location of The White House, an infamous magic brothel described by Henry Mayhew as "a notorious place of ill-fame".[18]

Before the introduction of the Street Offences Act in 1959, prostitutes packed the streets and alleys of Soho and by the early sixties the area was home to nearly a hundred strip clubs and almost every doorway in Soho had little postcards advertising "Large Chest for Sale" or "French Lessons Given". These were known as "walk ups". With prostitution driven off the streets, many clubs such as The Blue Lagoon became prostitution fronts. The Metropolitan Police Vice squad at that time suffered from corrupt police officers involved with enforcing organised crime control of the area, but simultaneously accepting "back-handers" or bribes.

Clip Joints also surfaced in the 1960s, these establishments sold colored water as champagne with the promise of sex to follow, thus fleecing tourists looking for a "good time". Also in 1960, London's first sex cinema theatre, the Compton Cinema Club[19] (a membership only club to get around the law) opened at 56 Old Compton Street. It was owned by Michael Klinger who produced many of the early Roman Polański Films such as Cul-de-Sac (1966). Michael Klinger also owned the Heaven and Hell hostess club (which had earlier been just a Beatnik club) across the road and a few doors down from the 2I's on the corner of Old Compton Street and Dean Street.

Harrison Marks, a “glamour photographer” and girlie magazine publisher, had a photographic gallery located at No. 4 Gerrard Street and published several magazines such as Kamera, which sold from the late fifties till 1968. The model Pamela Green prompted him to take up nude photography, and she remained the creative force in their business until they split in 1967. The content, however, by today’s standard is very innocent.

By the mid seventies the sex shops had grown from the handful opened by Carl Slack in the early sixties to a total of fifty nine sex shops[20] which then dominated the square mile. Some had secret backrooms selling hardcore photographs, Beeline Books (Published in America by David Zentner[21]) and Olympia press editions.

By the 1980s, purges of the police force along with a tightening of licensing controls by the City of Westminster led to a crackdown on these illegal premises. By 2000, a substantial relaxation of general censorship, and the licensing or closing of unlicensed sex shops had reduced the red-light area to just a small area around Brewer Street and Berwick Street. Several strip clubs in the area were reported in London's Evening Standard newspaper in February 2003 to still be rip-offs (known as clip joints), aiming to intimidate customers into paying for absurdly over-priced drinks and very mild 'erotic entertainment'. Prostitution is still widespread in parts of Soho, with several buildings used as brothels, and there is a persistent problem with drug dealing on some street corners.

Soho continues to be the centre of the sex industry in London, and features numerous licenced sex shops, a nude peep show on Tisbury Court and an adult cinema. Prostitutes are widely available, operating in studio flats. These are sign-posted by fluorescent "model" signs at street level.

Windmill Theatre

The Windmill Theatre was notorious for its risqué nude tableaux vivants, in which the models had to remain motionless to avoid censorship. It opened in June 1931 and was the only theatre in London which never closed,[22] except for the twelve compulsory days between 4 and 16 September 1939. It stood on the site of a windmill that dated back to the reign of Charles II until late in the 18th century. The theatre was sold to the Compton Cinema Group and it closed on 31 October 1964 and was reconstructed as a cinema and casino.

Raymond Revuebar

The Raymond Revuebar was a small theatre specialising in striptease and nude dancing. It was owned by Paul Raymond and opened on 21 April 1958. The most striking feature of the Revuebar was the huge brightly lit sign declaring it to be the "World Centre of Erotic Entertainment".

In the early eighties, the upstairs became known as the Boulevard Theatre[23] and was used by a small group of alternative comedians called "The Comic Strip" before they found wider recognition with the series The Comic Strip Presents on Channel 4. It was also used as a "straight" theatre venue for a series of play premieres that included Diary of a Somebody (the Joe Orton diaries) by John Lahr, a rock opera version of Macbeth by Howard Goodall and The Lizard King (the Jim Morrison play) by Jay Jeff Jones.

The name and control of the theatre (but crucially, not the property itself) was bought by Gerald Simi in 1997.[24] Gradually the theatre's fortunes waned, with Simi citing rising rent demands from Raymond as the cause.[25]

The Revuebar closed on 10 June 2004 and became a gay bar and cabaret venue called Too2Much, designed by Anarchitect. In November 2006, it changed its name to Soho Revue Bar. The launch party included performances by Boy George, Antony Costa and Marcella Detroit.[26] On 29 January 2009, the Soho Revue Bar closed.

Education

Streets

- Berwick Street has record shops, and a small street market open from Monday to Saturday.

- Carnaby Street was for a short time the fashion centre of 1960s "Swinging London" although it quickly became known for poor quality 'kitsch' products.

- Dean Street is home to the Soho Theatre, and a pub called The French House which was during WWII popular with the French Government-in-exile. Karl Marx lived at numbers 54 and 28 Dean Street between 1851 and 1856.

- Denmark Street was a music publishing centre.

- Frith Street where John Logie Baird first demonstrated television in his laboratory, now the location of Bar Italia. A plaque above the stage door of the Prince Edward Theatre identifies the site where Mozart lived for a few years as a child.

- Gerrard Street was home to Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club, the 43 Club and the Dive Bar, under the Kings Head. It is also the centre of London's Chinatown.

- Golden Square is a small urban square.

- Great Marlborough Street was once the location of Philip Morris' original London factory and gave its name to the Marlboro brand of cigarettes. It is also the former home of the London College of Music.

- Great Windmill Street (below Lexington Street on map - not indicated) was home to the Windmill Theatre "which never closed". The principles of The Communist Manifesto were laid out at a meeting in the Red Lion pub.

- Greek Street

- Old Compton Street was the birthplace of Europe's rock club circuit (2 I's club) and boasted the first adult cinema in England (The Compton Cinema Club). Dougie Millings, who was the famous Beatles tailor, had his first shop at 63 Old Compton Street which opened in 1962.[27] Old Compton Street is now the core of Soho's gay village.

- In Soho Square are Paul McCartney's office MPL Communications, and the former Football Association headquarters.

- Wardour Street was home of the Marquee Club. Another seventies rock hangout was The Intrepid Fox Pub[28] (97/99 Wardour Street).

Popular venues

- Punk Nightclub: A Soho club that is well known for celebrity spotting. It is a popular hangout for Kate Moss and Kelly Osbourne[29]

- Riflemaker Contemporary Art: Since it became a gallery in 2004 Riflemaker Contemporary Art has been one of the most successful independent[30] galleries in London thanks to the high quality of the somewhat obscure shows held there

- The Nosh Bar

Nearest Underground stations and Other Transport Issues

The nearest London Underground stations are Oxford Circus, Piccadilly Circus, Tottenham Court Road, Leicester Square and Covent Garden.

Night-time traffic surveys carried by Westminster Council (www3.westminster.gov.uk/docstores/.../SOHO_ENTS_SPG_july_2006.pdf) between 10pm and 4am indicate that Old Compton Street, Dean Street, and Frith Street experienced the highest levels of traffic within the Soho area.

The busiest location was Old Compton Street between the junctions with Dean and Frith Street, which experienced ‘medium’ levels of traffic for four of the six hours of the survey, including between 2am and 4am.

Westminster Council stated that the narrow footways can become very congested at night, particularly at weekends, with people drinking in the street, eating outside takeaways, queuing at entertainment venues or to use bank ATMs, and people passing through the area. There are a number of premises with tables and chairs located on restricted pavement areas and this can cause a conflict between pedestrians and traffic.

In order to satisfactorily accommodate the number of visitors to the area, a campaign was established early in 2010 (www.savingsoho.co.uk) seeking to implement pedestrian priority works in this sensitive historic area.

References

- ^ Soho London - Local information for Soho London, Soho Restaurants and Bars

- ^ 'Estate and Parish History', Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34: St Anne Soho (1966), pp. 20-6 accessed: 17 May 2007

- ^ Adrian Room, A Concise Dictionary of Modern Place-Names in Great Britain and Ireland, page 113

- ^ John Richardson, The Annals of London, page 156

- ^ Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, page number varies according to edition

- ^ Arthur Mee, The King's England: London, page 233

- ^ Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, 1886

- ^ Making the Modern World — John Snow and the Broad Street pump

- ^ Steven Johnson, The Ghost Map (The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World), Riverhead Books, New York, 2006, pp.299

- ^ Steven Johnson, The Ghost Map (The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World), Riverhead Books, New York 2006, pp.227-8

- ^ “Mack the Knife” (from the original German translation by Manheim & Willett).

- ^ London Timeline. http://londonrockandpop.com/page5.htm

- ^ The Goings On. http://londonrockandpop.com/page3.htm

- ^ Shakin' All Over.

- ^ Ronan O'Rahilly.http://www.offshoreechos.com/Caroline%2060/Radio%20Caroline%20-%20The%2060s%20Chapter%2004.htm

- ^ Ronnie Scott's. http://freespace.virgin.net/davidh.taylor/peteking.htm

- ^ “Tony Brainsby, Obituary”, The Independent March 2000.

- ^ During, Simon (2004). Modern Enchantments: The Cultural Power of Secular Magic. Harvard University Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 9780674013711.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Michael Klinger. http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/film-and-tv/features/the-lost-worlds-of-british-cinema-the-horror-525200.html

- ^ Sinful Streets of London (map and guide book), published in 1983

- ^ David Zentner. http://www.lukeisback.com/stars/stars/stars/male/david_zentner.htm

- ^ Windmill Theatre. http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/Archive/Feb2003/Page2.htm

- ^ http://www.lrb.co.uk/v03/n16/ian-hamilton/the-comic-strip

- ^ MegaStar: Home

- ^ Erotic show choreographer Gerard Simi

- ^ http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4153/is_200406/ai_n12080699

- ^ The Look. Adventures in Pop and Rock Fashion. By Paul Gorman. Page 37

- ^ Intrepid Fox Pub. http://www.urban75.org/london/intrepid-fox.html

- ^ Soho London

- ^ Riflemaker Contemporary Art

External links

- The Soho Society

- The Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34, St Anne Soho (1966) — full text online

- The Soho Bombing in 1999