Krishna

| Krishna | |

|---|---|

| Devanagari | कृष्ण |

Krishna (कृष्ण in Devanagari, kṛṣṇa in IAST, IPA: [ˈkr̩ʂɳə] in classical Sanskrit) is a deity worshiped across many traditions in Hinduism in a variety of perspectives. While many Vaishnava groups recognize him as an avatar of Vishnu, other traditions within Krishnaism consider Krishna to be svayam bhagavan, or the Supreme Being.

Krishna is often depicted as an infant, as a young boy playing a flute as in the Bhagavata Purana,[1] or as a youthful prince giving direction and guidance as in the Bhagavad Gita.[2] The stories of Krishna appear across a broad spectrum of Hindu philosophical and theological traditions.[3] They portray him in various perspectives: a god-child, a prankster, a model lover, a divine hero and the Supreme Being.[4] The principal scriptures discussing Krishna's story are the Mahābhārata, the Harivamsa, the Bhagavata Purana and the Vishnu Purana.

The various traditions dedicated to different manifestations of Krishna, such as Vasudeva, Bala Krishna and Gopala, existed as early as 4th century BC. The Krishna-bhakti Movement spread to southern India by the 9th century AD, while in northern India Krishnaism schools were well established by 11th century AD. From the 10th century AD, with the growing Bhakti movement, Krishna became a favorite subject in performing arts and regional traditions of devotion developed for forms of Krishna such as Jagannatha in Orissa, Vithoba in Maharashtra and Shrinathji in Rajasthan. Since 1966, the Krishna-bhakti movement has spread in the West, with the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON). Devotion to Krishna is widely diffused and extends to Jains, Buddhists, Bahá'ís and beyond India.

Etymology and names

The Sanskrit word kṛṣṇa has the literal meaning of "black", "dark" or "dark-blue"[5] and is used as a name to describe someone with dark skin. Krishna is often depicted in murtis (images) as black, and is generally shown in paintings with a blue skin.

Some Hindu traditions often ascribe varying interpretations and powers to the names. The Mahabharata's Udyoga-parva (Mbh 5.71.4) divides kṛṣṇa into elements kṛṣ and ṇa, kṛṣ (a verbal root meaning "to plough, drag") being taken as expressing bhū "being; earth" and ṇa being taken as expressing nirvṛti "bliss". In the Brahmasambandha mantra of the Vallabha sampradaya, the syllables of the name Krishna are assigned the power to destroy sin relating to material, self and divine causes.[6] Mahabharata verse 5.71.4 is also quoted in Chaitanya Charitamrita and Prabhupada in his commentary, translates the bhū as "attractive existence", thus Krishna is also interpreted as meaning "all-attractive one".[7][8] This quality of Krishna is stated in the atmarama verse of Bhagavatam 1.7.10.[9]

The name Krishna is also the 57th name in the Vishnu Sahasranama and means the Existence of Bliss, according to Adi Sankara's interpretation. [10] Krishna is also known by various other names, epithets and titles, which reflect his many associations and attributes. Among the most common names are Govinda, "finder of cows", or Gopala, "protector of cows", which refer to Krishna's childhood in Vraja.[11][12] Some of the distinct names may be regionally important; for instance, Jagannatha (literally "Lord of the Universe"), a popular deity of Puri in eastern India.[13]

Iconography

Krishna is easily recognized by his representations. Though his skin colour may be depicted as black or dark in some representations, particularly in murtis, in other images such as modern pictorial representations, Krishna is usually shown with blue skin. He is often shown wearing a yellow silk dhoti and peacock feather headgear. Common depictions show him as a little boy, or as a young man in a characteristic relaxed pose, playing the flute.[14][15] In this form, he usually stands with one leg bent in front of the other and raises a flute to his lips, accompanied by cows, emphasising his position as the divine herdsman, Govinda, or with the gopis (milkmaids).

The scene on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, notably where he addresses Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita, is another common subject for representation. In these depictions, he is shown as a man, often shown with typical god-like characteristics of Hindu religious art, such as multiple arms or heads, denoting power, and with attributes of Vishnu, such as the chakra or in his two-armed form as a charioteer.

Representations in temples often show Krishna as a man standing in an upright, formal pose. He may be alone, or with associated figures:[16] his brother Balarama and sister Subhadra, or his main queens Rukmini and Satyabhama.

Often, Krishna is pictured with his gopi-consort Radha. Manipuri Vaishnavas do not worship Krishna alone, but as Radha Krishna,[17] a combined image of Krishna and Radha. This is also a characteristic of the schools Rudra[18] and Nimbarka sampradaya,[19] as well as that of Swaminarayan faith. The traditions celebrate Radha Ramana murti, who is viewed by Gaudiyas as a form of Radha Krishna.[20]

Krishna is also depicted and worshipped as a small child (bāla kṛṣṇa, the child Krishna), crawling on his hands and knees or dancing, often with butter in his hand.[21][22] Regional variations in the iconography of Krishna are seen in his different forms, such as Jaganatha of Orissa, Vithoba of Maharashtra[23] and Shrinathji in Rajasthan.

Literary sources

The earliest text to explicitly provide detailed descriptions of Krishna as a personality is the epic Mahābhārata which depicts Krishna as an incarnation of Vishnu.[24] Krishna is central to many of the main stories of the epic. The eighteen chapters of the sixth book (Bhishma Parva) of the epic that constitute the Bhagavad Gita contain the advice of Krishna to the warrior-hero Arjuna, on the battlefield. Krishna is already an adult in the epic, although there are allusions to his earlier exploits. The Harivamsa, a later appendix to this epic, contains the earliest detailed version of Krishna's childhood and youth.

Many Puranas tells Krishna's life-story or some highlights from it. Two Puranas, the Bhagavata Purana and the Vishnu Purana, that contain the most elaborate telling of Krishna’s story and teachings are the most theologically venerated by the Gaudiya Vaishnava schools.[25] Roughly one quarter of the Bhagavata Purana is spent extolling his life and philosophy.

Yāska's Nirukta, an etymological dictionary around the 5th century BC, contains a reference to the Shyamantaka jewel in the possession of Akrura, a motif from well known Puranic story about Krishna.[26]Satha-patha-brahmana and Aitareya-Aranyaka, associate Krishna with his Vrishni origins.[27] In early texts, such as Rig Veda, there are no obvious references to Krishna, however some, like Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar attempted to show that "the very same Krishna" made an appearance, e.g. as the drapsa ... krishna "black drop" of RV 8.96.13.[28][26]

Life

This summary is based on details from the Mahābhārata, the Harivamsa, the Bhagavata Purana and the Vishnu Purana. The scenes from the narrative are set in north India, mostly in the present states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana, Delhi and Gujarat.

Birth

Traditional belief based on scriptural details and astrological calculations gives the date of Krishna's birth, known as Janmashtami,[29] as either 18 or 21 July 3228 BC.[30][31][32] Krishna belonged to the royal family of Shephereds - Dhangar in Mathura, and was the eighth son born to the princess Devaki, and her husband Vasudeva. Mathura was the capital of the Yadavas (also called the Surasenas), to which Krishna's parents Vasudeva and Devaki belonged. The king Kamsa, Devaki's brother,[33] had ascended the throne by imprisoning his father, King Ugrasena. Afraid of a prophecy that predicted his death at the hands of Devaki's eighth son, he had locked the couple into a prison cell. After Kamsa killed the first six children, and Devaki's apparent miscarriage of the seventh, being transferred to Rohini as Balarama, Krishna took birth.

Since Vasudeva believed Krishna's life was in danger, Krishna was secretly taken out of the prison cell to be raised by his foster parents, Yasoda [34] and Nanda in Gokula. Two of his other siblings also survived, Balarama (Devaki's seventh child, transferred to the womb of Rohini, Vasudeva's first wife) and Subhadra (daughter of Vasudeva and Rohini, born much later than Balarama and Krishna).[35] According to Bhagavata Purana it is believed that Krishna was born without a sexual union, by "mental transmission" from the mind of Vasudeva into the womb of Devaki. Hindus believe that in that time, this type of union was possible for achieved beings.[29][36][37]

Childhood and youth

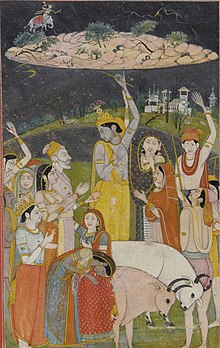

Nanda was the head of a community of cow-herders, and he settled in Vrindavana. The stories of Krishna's childhood and youth tell of his mischievous pranks as Makhan Chor (butter thief), his foiling of attempts to take his life, and his role as a protector of the people of Vrindavana. Krishna is said to have killed the demons like Putana, sent by Kamsa for Krishna's life. He tamed the serpent Kaliya, who previously poisoned the waters of Yamuna river, thus leading to the death of the cowherds. In Hindu art, Krishna is often depicted dancing on the multi-hooded Kaliya. Krishna is believed to have lifted the Govardhana hill and taught Indra—the king of the devas and rain a lesson—to protect native people of Vrindavana from persecution by Indra and prevent the devastation of the pasture land of Govardhan. Indra had too much pride and was angry when Krishna advised the people of Vrindavana to take care of their animals and their environment that provide them with all their necessities, instead of Indra. [38][39] In the view of some, the spiritual movement started by Krishna had something in it which went against the orthodox forms of worship of the Vedic gods such as Indra.[40]

The stories of his play with the gopis (milkmaids) of Vrindavana became known as the Rasa lila and were romanticised in the poetry of Jayadeva, author of the Gita Govinda. These became important as part of the development of the Krishna bhakti traditions worshiping Radha Krishna.[41]

The prince

On his return to Mathura as a young man, Krishna overthrew and killed his uncle Kamsa after avoiding several assassination attempts from Kamsa's followers. He reinstated Kamsa's father, Ugrasena, as the king of the Yadavas and became a leading prince at the court.[42] During this period, he became a friend of Arjuna and the other Pandava princes of the Kuru kingdom, who were his cousins. Later, he took his Yadava subjects to the city of Dwaraka (in modern Gujarat) and established his own kingdom there.[43]

Krishna married Rukmini, the princess of Vidarbha, by abducting her from her wedding on her request. According to Srimad Bhagavatam, Krishna married with 16,108 wives,[44][45] of which eight were chief—including Rukmini, Satyabhama, Jambavati;[46] Krishna subsequently married 16,100 maidens who were being held in captivity by demon Narakasura, to save their honor. Krishna killed the demon and released them all. According to strict social custom of the time all of the captive women were degraded, and would be unable to marry, as they had been under the control of Narakasura, however Krishna married them to reinstate their status in the society.This wedding with 16100 abadoned daughters was more of a en masse women rehabilitation.[47] In Vaishnava traditions, Krishna's wives are believed to be forms of the goddess Lakshmi—consort of Vishnu, or special souls who attained this qualification after many lifetimes of austerity, while his primary queen Satyabhama, is an expansion of Radha.[48]

Kurukshetra War and Bhagavad Gita

Once battle seemed inevitable, Krishna offered both sides the opportunity to choose between having either his army or simply himself alone, but on the condition that he personally would not raise any weapon. Arjuna, on behalf of the Pandavas, chose to have Krishna on their side, and Duryodhana, chief of the Kauravas, chose Krishna's army. At the time of the great battle, Krishna acted as Arjuna's charioteer, since it was a position that did not require the wielding of weapons.

Upon arriving at the battlefield, and seeing that the enemies are his family, his grandfather, his cousins and loved ones, Arjuna becomes doubtful about fighting. Krishna then advises him about the battle, with the conversation soon extending into a discourse which was later compiled as the Bhagavad Gita.[49]

Later life

At a festival, a fight broke out between the Yadavas who exterminated each other. His elder brother Balarama then gave up his body using Yoga. Krishna retired into the forest and sat under a tree in meditation. While Vyasa's Mahābhārata says that Shri Krishna ascended to heaven, Sarala's Mahabhārata narrates the story that a hunter mistook his partly visible left foot for a deer and shot an arrow wounding him mortally.[50][51][52]

According to Puranic sources,[53] Krishna's disappearance marks the end of Dvapara Yuga and the start of Kali Yuga, which is dated to February 17/18, 3102 BC.[54] Vaishnava teachers such as Ramanujacharya and Gaudiya Vaishnavas held the view that the body of Krishna is completely spiritual and never decays as this appears to be the perspective of the Bhagavata Purana. Krishna never appears to grow old or age at all in the historical depictions of the Puranas despite passing of several decades, but there are grounds for a debate whether this indicates that he has no material body, since battles and other descriptions of the Mahabhārata epic show clear indications that he seems to be subject to the limitations of nature.[55] While battles apparently seem to indicate limitations, Mahabharatha also shows in many places where Krishna is not subject to any limitations as through episodes Duryodhana trying to arrest Krishna where His body burst into fire showing all creation within Him.[56] Krishna is also explicitly told to be without deterioration elsewhere. [57]

Early historical references

One of the earliest recorded instances of a Krishna who could potentially be identified with the deity can be found in the Chandogya Upanishad, where he is mentioned as the son of Devaki, and to whom Ghora Angirasa was a teacher.[58][59] The Upanishads, namely Nārāyaṇātharvaśirsa and Ātmabodha, specifically regard Krishna as a god and associate him with Vishnu.[58]

References to Vāsudeva also occur in early Sanskrit literature. Taittiriya Aranyaka (X,i,6) identifies him with Narayana and Vishnu. Panini, ca. 4th century BC, in his Ashtadhyayi explains the word "Vāsudevaka" as a Bhakta (devotee) of Vāsudeva.[26] This, along with the mention of Arjuna in the same context, indicates that the Vāsudeva here is Krishna.[60] At some stage during the Vedic period, Vasudeva and Krishna became one deity, and by the time of composition of the redaction of Mahabharata that survives till today, Krishna (Vasudeva) was generally acknowledged as an avatar of Vishnu and often as the Supreme God.[58]

In the 4th century BC, Megasthenes the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya says that the Sourasenoi (Surasena), who lived in the region of Mathura worshipped Herakles. This Herakles is usually identified with Krishna due to the regions mentioned by Megasthenes as well as similarities between some of the herioc acts of the two.[61] The Greco-Bactrian ruler Agathocles issued coins bearing the images of Krishna and Balarama in around 180–165 BC.

Three inscriptions from Hāthibādā and one from Ghosundi (near Nāgari, Chittorgarh district) from the 2nd century BC, record the building of a pujā-silā-prākar (stone enclosure for worship) in Nārāyana-vata (park of Nārāyana) by king Gājāyana Sarvatāta for the worship of the gods Sankarshana (Balarama) and Vasudeva (Krishna).[62][61] From the same century,the Nānāghāt cave (Maharashtra) inscription of the Satavahana queen Nāyanika begins with an invocation to various gods including Sankarshana and Vasudeva.[63]

In the 1st century BC, Heliodorus from Greece erected the Heliodorus pillar at Besnagar near Bhilsa with the inscription:[61] "This Garuda-column of Vasudeva the god of gods was erected here by Heliodorus, a worshipper of the Lord Bhagavata, the son of Diya Greek Dion and an inhabitant of Taxila, who came as ambassador of the Greeks from the Great King Amtalikita [Greek Antialcidas] to King Kasiputra Bhagabhadra the saviour, who was flourishing in the fourteenth year of his reign [...] three immortal steps [...] when practiced, lead to heaven—self-control, charity, and diligence."

Another inscription from Besnagar, from the same period, records the setting up of a Garuda pillar in a prasādottama (excellent temple) in the twelfth regnal year of a king called Bhāgavata, usually identified as a Sunga king.[64][65] A 1st century BC inscription from Mathura records the building of a part of a sanctuary to Vasudeva by the great satrap Sodasa.

The renowned grammar scholar Patanjali, who wrote his commentary on Panini's grammar rules around 150 BC (known as the Mahabhashya), quotes a verse: "May the might of Krishna accompanied by Samkarshana increase!" Other verses are mentioned. One verse speaks of "Janardana with himself as fourth" (Krishna with three companions, the three possibly being Samkarshana, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha). Another verse mentions musical instruments being played at meetings in the temples of Rama (Balarama) and Kesava (Krishna). Patanjali also describes dramatic and mimetic performances (Krishna-Kamsopacharam) representing the killing of Kamsa by Vasudeva.[66]

Also in the 1st century BC, there seems to be evidence for a worship of five Vrishni heroes (Balarama, Krishna, Pradyumna, Aniruddha and Samba) for an inscription has been found at Mora near Mathura, which apparently mentions a son of the great satrap Rajuvula, probably the satrap Sodasa, and an image of Vrishni, "probably Vasudeva, and of the "Five Warriors".[67] Brahmi inscription on the Mora stone slab, now in the Mathura Museum.[68][69] Many inscriptions and references to worship of Krishna can be found from the early centuries of the Common Era.

Worship

Vaishnavism

The worship of Krishna is part of Vaishnavism, which regards Vishnu as the Supreme God and venerates his associated avatars, their consorts, and related saints and teachers. Krishna is especially looked upon as a full manifestation of Vishnu, and as one with Vishnu himself.[70] However the exact relationship between Krishna and Vishnu is complex and diverse,[71] where Krishna is sometimes considered an independent deity, supreme in his own right.[72] Out of many deities Krishna is particularly important, and traditions of Vaishnava lines are generally centered either on Vishnu or on Krishna, as supreme. The term Krishnaism has been used to describe the sects of Krishna, reserving term "Vaishnavism" for sects focusing on Vishnu in which Krishna is an avatar, rather than a transcended being.[73]

All Vaishnava traditions recognise Krishna as an avatar of Vishnu; others identify Krishna with Vishnu; while traditions, such as Gaudiya Vaishnavism,[74][75] Vallabha Sampradaya and the Nimbarka Sampradaya, regard Krishna as the svayam bhagavan, original form of God, or the Lord himself.[76][77][78][79][80] Swaminarayan, the founder of the Swaminarayan Sampraday also worshipped Krishna as god himself. "Greater Krishnaism" corresponds to the second and dominant phase of Vaishnavism, revolving around the cults of the Vasudeva, Krishna, and Gopala of late Vedic period.[81] Today the faith has a significant following outside of India as well.[82]

Early traditions

The deity Krishna-Vasudeva (kṛṣṇa vāsudeva "Krishna, the son of Vasudeva") is historically one of the earliest forms of worship in Krishnaism and Vaishnavism.[26][83] It is believed to be a significant tradition of the early history of the worship of Krishna in antiquity.[84][85] This tradition is considered as earliest to other traditions that led to amalgamation at a later stage of the historical development. Other traditions are Bhagavatism and the cult of Gopala, that along with the cult of Bala Krishna form the basis of current tradition of monotheistic religion of Krishna.[86][87] Some early scholars would equate it with Bhagavatism,[84] and the founder of this religious tradition is believed to be Krishna, who is the son of Vasudeva, thus his name is Vāsudeva, he is belonged to be historically part of the Satvata tribe, and according to them his followers called themselves Bhagavatas and this religion had formed by the 2nd century BC (the time of Patanjali), or as early as the 4th century BC according to evidence in Megasthenes and in the Arthasastra of Kautilya, when Vāsudeva was worshiped as supreme deity in a strongly monotheistic format, where the supreme being was perfect, eternal and full of grace.[84] In many sources outside of the cult, devotee or bhakta is defined as Vāsudevaka.[88] The Harivamsa describes intricate relationships between Krishna Vasudeva, Sankarsana, Pradyumna and Aniruddha that would later form a Vaishnava concept of primary quadrupled expansion, or avatara.[89]

Bhakti tradition

Bhakti, meaning devotion, is not confined to any one deity. However Krishna is an important and popular focus of the devotional and ecstatic aspects of Hindu religion, particularly among the Vaishnava sects.[74][90] Devotees of Krishna subscribe to the concept of lila, meaning 'divine play', as the central principle of the Universe. The lilas of Krishna, with their expressions of personal love that transcend the boundaries of formal reverence, serve as a counterpoint to the actions of another avatar of Vishnu: Rama, "He of the straight and narrow path of maryada, or rules and regulations."[75]

The Bhakti movements devoted to Krishna became prominent in southern India in the 7th to 9th centuries AD. The earliest works included those of the Alvar saints of the Tamil country.[91] A major collection of their works is the Divya Prabandham. The Alvar Andal's popular collection of songs Tiruppavai, in which she conceives of herself as a gopi, is the most famous of the oldest works in this genre.[92][93] [94] Kulasekaraazhvaar's Mukundamala was another notable work of this early stage.

Spread of the Krishna-Bhakti Movement

The movement spread rapidly from northern India into the south, with the Sanskrit poem Gita Govinda of Jayadeva (12th century AD) becoming a landmark of devotional, Krishna-based literature. It elaborated a part of the Krishna legend—his love for one particular gopi, called Radha, a minor character in Bhagavata Purana but a major one in other texts like Brahma Vaivarta Purana. By the influence of Gita Govinda, Radha became inseparable from devotion to Krishna.[4]

While the learned sections of the society well versed in Sanskrit could enjoy works like Gita Govinda or Bilvamangala's Krishna-Karnamritam, the masses sang the songs of the devotee-poets, who composed in the regional languages of India. These songs expressing intense personal devotion were written by devotees from all walks of life. The songs of Meera and Surdas became epitomes of Krishna-devotion in north India.

These devotee-poets, like the Alvars before them, were aligned to specific theological schools only loosely, if at all. But by the 11th century AD, Vaishnava Bhakti schools with elaborate theological frameworks around the worship of Krishna were established in north India. Nimbarka (11th century AD), Vallabhacharya (15th century AD) and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (16th century AD) were the founders of the most influential schools. These schools, namely Nimbarka Sampradaya, Vallabha Sampradaya and Gaudiya Vaishnavism respectively, see Krishna as the supreme god, rather than an avatar, as generally seen.

In the Deccan, particularly in Maharashtra, saint poets of the Varkari sect such as Dnyaneshwar, Namdev, Janabai, Eknath and Tukaram promoted the worship of Vithoba,[23] a local form of Krishna, from the beginning of the 13th century until the late 18th century.[4] In southern India, Purandara Dasa and Kanakadasa of Karnataka composed songs devoted to the Krishna image of Udupi. Rupa Goswami of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, has compiled a comprehensive summary of bhakti named Bhakti-rasamrita-sindhu.[90]

In the West

Since 1966, the Krishna bhakti movement has also spread outside India.[95] This is largely due to the Hare Krishna movement, the largest part of which is the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON).[96] The movement was founded by Prabhupada, who was instructed by his guru, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, to write about Krishna in English and to share the Gaudiya Vaishnava philosophy with people in the Western world.[97]

In the performing arts

While discussing the origin of Indian theatre, Horwitz talks about the mention of the Krishna story in Patanjali's Mahabhashya (c. 150 BC), where the episodes of slaying of Kamsa (Kamsa Vadha) and "Binding of the heaven storming titan" (Bali Bandha) are described.[98] Bhasa's Balacharitam and Dutavakyam (c. 400 BC) are the only Sanskrit plays centered on Krishna written by a major classical dramatist. The former dwells only on his childhood exploits and the latter is a one-act play based on a single episode from the Mahābhārata when Krishna tries to make peace between the warring cousins.[99]

From the 10th century AD, with the growing Bhakti movement, Krishna became a favourite subject of the arts. The songs of the Gita Govinda became popular across India, and had many imitations. The songs composed by the Bhakti poets added to the repository of both folk and classical singing.

The classical Indian dances, especially Odissi and Manipuri, draw heavily on the story. The 'Rasa lila' dances performed in Vrindavan shares elements with Kathak, and the Krisnattam, with some cycles, such as Krishnattam, traditionally restricted to the Guruvayur temple, the precursor of Kathakali.[100] The Sattriya dance, founded by the Assamese Vaishnava saint Sankardeva, extols the virtues of Krishna. Medieval Maharashtra gave birth to a form of storytelling known as the Hari-Katha, that told Vaishnava tales and teachings through music, dance, and narrative sequences, and the story of Krishna one of them. This tradition spread to Tamil Nadu and other southern states, and is now popular in many places throughout India.

Narayana Tirtha's (17th century AD) Krishna-Lila-Tarangini provided material for the musical plays of the Bhagavata-Mela by telling the tale of Krishna from birth until his marriage to Rukmini. Tyagaraja (18th century AD) wrote a similar piece about Krishna called Nauka-Charitam. The narratives of Krishna from the Puranas are performed in Yakshagana, a performance style native to Karnataka's coastal districts. Many movies in all Indian languages have been made based on these stories. These are of varying quality and usually add various songs, melodrama, and special effects.

In other religions

Jainism

The most exalted figures in Jainism are the twenty-four Tirthankaras. Krishna, when he was incorporated into the Jain list of heroic figures presented a problem with his activities which are not pacifist or non-violent. The concept of Baladeva, Vasudeva and Prati-Vasudeva was used to solve it. The Jain list of sixty-three Shalakapurshas or notable figures includes amongst others, the twenty-four Tirthankaras and nine sets of this triad. One of these triads is Krishna as the Vasudeva, Balarama as the Baladeva and Jarasandha as the Prati-Vasudeva. He was a cousin of the twenty-second Tirthankara, Neminatha. The stories of these triads can be found in the Harivamsha of Jinasena (not be confused with its namesake, the addendum to Mahābhārata) and the Trishashti-shalakapurusha-charita of Hemachandra.[101]

In each age of the Jain cyclic time is born a Vasudeva with an elder brother termed the Baladeva. The villain is the Prati-vasudeva. Baladeva is the upholder of the Jain principle of non-violence. However, Vasudeva has to forsake this principle to kill the Prati-Vasudeva and save the world. The Vasudeva then descends to hell as a punishment for this violent act. Having undergone the punishment he is then reborn as a Tirthankara.[102][103]

Buddhism

The story of Krishna occurs in the Jataka tales in Buddhism,[104] in the Ghatapandita Jataka as a prince and legendary conqueror and king of India.[105] In the Buddhist version, Krishna is called Vasudeva, Kanha and Keshava, and Balarama is his younger brother, Baladeva. These details resemble that of the story given in the Bhagavata Purana. Vasudeva, along with his nine other brothers (each son a powerful wrestler) and one elder sister (Anjana) capture all of Jambudvipa (many consider this to be India) after beheading their evil uncle, King Kamsa, and later all other kings of Jambudvipa with his Sudarshana Chakra. Much of the story involving the defeat of Kamsa follows the story given in the Bhagavata Purana.[106]

As depicted in the Mahābhārata, all of the sons are eventually killed due to a curse of sage Kanhadipayana (Veda Vyasa, also known as Krishna Dwaipayana). Krishna himself is eventually speared by a hunter in the foot by mistake, leaving the sole survivor of their family being their sister, Anjanadevi of whom no further mention is made.[107]

Since Jataka tales are given from the perspective of Buddha's previous lives (as well as the previous lives of many of Buddha's followers), Krishna appears as one of the lives of Sariputra, one of Buddha's foremost disciples and the "Dhammasenapati" or "Chief General of the Dharma" and is usually shown being Buddha's "right hand man" in Buddhist art and iconography.[108] The Bodhisattva, is born in this tale as one of his youngest brothers named Ghatapandita, and saves Krishna from the grief of losing his son.[105] The 'divine boy' Krishna as an embodiment of wisdom and endearing prankster is forming a part of worshipable pantheon in Japanese Buddhism.[109]

Bahá'í Faith

Bahá'ís believe that Krishna was a "Manifestation of God," or one in a line of prophets who have revealed the Word of God progressively for a gradually maturing humanity. In this way, Krishna shares an exalted station with Buddha, Zoroaster, the Báb, and the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, Bahá'u'lláh.[110]

Ahmadiyya Islam

Members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community believe Krishna to be a great prophet of God as described by their founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. Ghulam Ahmad also claimed to be the likeness of Krishna as a latter day reviver of religion and morality whose mission was to reconcile man with God.:[111] Ahmadis maintain that the term Avtar is synonymous with the term 'prophet' of the middle eastern religious tradition as God's intervention with man; as God appoints a man as his vicegerent upon earth.

Let it be clear that Lord Krishna, according to what has been revealed to me, was such a truly great man that it is hard to find his like among the rishis and avatars of the Hindus. He was an avatar (i.e. a prophet) of his time upon whom the Holy Spirit would descend from God. He was from God, victorious and prosperous. He cleansed the land of the Arya from sin and was in fact the prophet of his age. He was full of love for God, a friend of virtue and an enemy of evil.

Other

Krishna worship or reverence has been adopted by several new religious movements since the 19th century, and he is sometimes a member of an eclectic pantheon in occult texts, along with Greek, Buddhist, Biblical and even historical figures.[112] For instance, Édouard Schuré, an influential figure in perennial philosophy and occult movements, considered Krishna a Great Initiate; while Theosophists regard him as one of the Masters, a spiritual teacher for humanity.[113][114] Krishna was canonized by Aleister Crowley and is recognized as a saint in the Gnostic Mass of Ordo Templi Orientis.[115][116]

Krishnology

Vaishnava theology has been a subject of study for many devotees, philosophers and scholars within India for centuries.[3] In recent decades this study called Krishnology, has also been taken on by a number of academic institutions in Europe, such as the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies and Bhaktivedanta College. The Vaishnava scholars instrumental in this western discourse include Tamala Krishna Goswami, Hridayananda dasa Goswami, Graham Schweig, Kenneth R. Valpey, Ravindra Svarupa dasa, Sivarama Swami, Satyaraja Dasa, and Guy Beck, among others.[78]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Knott 2000, p. 56

- ^ Knott 2000, p. 36, p. 15

- ^ a b Richard Thompson, Ph. D. (December 1994). "Reflections on the Relation Between Religion and Modern Rationalism". Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Mahony, W.K. (1987). "Perspectives on Krsna's Various Personalities". History of Religions. 26 (3): 333–335. doi:10.2307/599733.

- ^ "Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary p.306". website. Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon project. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Beck 1993, p. 195

- ^

Bhaktivedanta Swami, Prabhupada. "Chaitanya Charitamrta Madhya-lila Chapter 9 Verse 30". vedabase.net. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

{{cite web}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ Lynne Gibson (2002). Modern World Religions: Hinduism - Pupils Book Foundation (Modern World Religions). Oxford [England]: Heinemann Educational Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 0-435-33618-5.

- ^ Goswami 1998, p. 141

- ^ Vishnu sahasranama, Swami Tapasyananda's translation, pg. 51.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 17 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Hiltebeitel, Alf (2001). Rethinking the Mahābhārata: a reader's guide to the education of the dharma king. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 251–53, 256, 259. ISBN 0-226-34054-6.

- ^ B.M.Misra. Orissa: Shri Krishna Jagannatha: the Mushali parva from Sarala's Mahabharata. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-514891-6. in Bryant 2007, p. 139 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana. [s.l.]: Grolier. 1988. p. 589. ISBN 0-7172-0119-8.

- ^

Benton, William (1974). The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 885. ISBN 0852292902, 9780852292907.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Harle, J. C. (1994). The art and architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. p. 410. ISBN 0-300-06217-6.

figure 327. Manaku, Radha's messenger describing Krishna standing with the cow-girls, from Basohli.

- ^

Datta, Amaresh (1994). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4290.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The penny cyclopædia [ed. by G. Long]. 1843, p.390 [1]

- ^ Ramesh M. Dave, K. K. A. Venkatachari, The Bhakta-bhagawan Relationship: Paramabhakta Parmeshwara Sambandha. Sya. Go Mudgala, Bochasanvasi Shri Aksharpurushottama Sanstha, 1988. p.74

- ^ Valpey 2006, p. 52

- ^

Hoiberg, Dale (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. p. 251. ISBN 0852297602, 9780852297605.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Satsvarupa dasa Goswami (1998), The Qualities of Sri Krsna, GNPress, pp. 152 pages, ISBN 0911233644

- ^ a b Vithoba is not only viewed as a form of Krishna. He is also by some considered that of Vishnu, Shiva and Gautama Buddha according to various traditions. See: Kelkar, Ashok R. (2001) [1992]. "Sri-Vitthal: Ek Mahasamanvay (Marathi) by R.C. Dhere". Encyclopaedia of Indian literature. Vol. 5. Sahitya Akademi. pp. p. 4179. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|pages=has extra text (help) and Mokashi, Digambar Balkrishna (1987). Palkhi: a pilgrimage to Pandharpur - translated from the Marathi book Pālakhī by Philip C. Engblom. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 35. ISBN 0887064612.{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|publsher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Wendy Doniger (2008). "Britannica: Mahabharata". encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Elkman, S.M. (1986). Jiva Gosvamin's Tattvasandarbha: A Study on the Philosophical and Sectarian Development of the Gaudiya Vaisnava Movement. Motilal Banarsidass Pub.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Bryant 2007, p. 4 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Sunil Kumar Bhattacharya Krishna-cult in Indian Art. 1996 M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 8175330015 p.128: Satha-patha-brahmana and Aitareya-Aranyaka with reference to first chapter.

- ^ Sunil Kumar Bhattacharya Krishna-cult in Indian Art. 1996 M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 8175330015 p.126: "According to (D.R.Bhadarkar), the word Krishna referred to in the expression 'Krishna-drapsah' in the Rig- Veda, denotes the very same Krishna".

- ^ a b Knott 2000, p. 61

- ^ See horoscope number 1 in Dr. B.V. Raman (1991). Notable Horoscopes. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120809017.

- ^ Arun K. Bansal's research published in Outlook India, September 13, 2004. "Krishna (b. July 21, 3228 BC)".

- ^ N.S. Rajaram takes these dates at face value when he opines that "We have therefore overwhelming evidence showing that Krishna was a historical figure who must have lived within a century on either side of that date, i.e., in the 3200-3000 BC period".(Prof. N. S. Rajaram (September 4th, 1999). "Search for the Historical Krishna". www.swordoftruth.com. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ According to the Bhagavata and Vishnu Puranas, but in some Puranas like Devi-Bhagavata-Purana,her paternal uncle. See the Vishnu-Purana Book V Chapter 1, translated by H. H. Wilson, (1840), the Srimad Bhagavatam, translated by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, (1988) copyright Bhaktivedanta Book Trust

- ^ Yashoda and Krishna

- ^ Bryant 2007, pp. 124–130, 224 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Bryant 2004, p. 425 (Note. 4)

- ^ Bryant 2004, p. 16 (Bh.P. X Ch 2.18)[2]

- ^ Lynne Gibson (1844). Calcutta Review. India: University of Calcutta Dept. of English. p. 119.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lynne Gibson (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 503.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore (ed. Sisir Kumar

Das) (1996). A Vision of Indias History. Sahitya Akademi: Sahitya Akademi. p. 444. ISBN 8126000945.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); line feed character in|author=at position 61 (help) - ^ Schweig, G.M. (2005). Dance of divine love: The Rasa Lila of Krishna from the Bhagavata Purana, India's classic sacred love story. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ; Oxford. ISBN 0691114463.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 290 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Bryant 2007, pp. 28–29 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Charudeva Shastri, Suniti Kumar Chatterji(1974) Charudeva Shastri Felicitation Volume, p. 449

- ^ David L. Haberman, (2003) Motilal Banarsidass, The Bhaktirasamrtasindhu of Rupa Gosvamin, p. 155, ISBN 812081861X

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 152 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Bryant 2007, pp. 130–133 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Rosen 2006, p. 136

- ^ Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, by Robert N. Minor in Bryant 2007, pp. 77–79 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Bryant 2007, pp. 148 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Dr. Satyabrata Das (November 2007). "Orissa Sarala's Mahabhārata" (PDF). magazine. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Kisari Mohan Ganguli (2006 - digitized). "The Mahabharata (originally published between 1883 and 1896)". book. Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The Bhagavata Purana (1.18.6), Vishnu Purana (5.38.8), and Brahma Purana (212.8) state that the day Krishna left the earth was the day that the Dvapara Yuga ended and the Kali Yuga began.

- ^ See: Matchett, Freda, "The Puranas", p 139 and Yano, Michio, "Calendar, astrology and astronomy" in Flood, Gavin (Ed) (2003), Blackwell companion to Hinduism, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-631-21535-2

- ^ Sutton (2000) pp.174-175

- ^ Kisari Mohan Ganguli (2006 - digitized). "The Mahabharata, Book 5: Udyoga Parva: Bhagwat Yana Parva: section CXXXI (originally published between 1883 and 1896)". book. Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kisari Mohan Ganguli (2006 - digitized). "The Mahabharata, Book 5: Udyoga Parva: Bhagwat Yana Parva: section CXXX(originally published between 1883 and 1896)". book. Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) "Knowest thou not sinless Govinda, of terrible prowess and incapable of deterioration?" - ^ a b c Hastings, James (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 195–196. ISBN 0766136884.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ See Chandogya Upanishad(III, xvii, 6) in Müller, Max (1879), Sacred Books of the East, vol. 1

- ^ Singh, R.R. (2007). Bhakti And Philosophy. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739114247.Page 10: Panini, the fifth-century BC Sanskrit grammarian also refers to the term Vaasudevaka, explained by the second century BC commentator Patanjali, as referring to "the follower of Vasudeva, God of gods."

- ^ a b c Rosen 2006, p. 126

- ^ D.C.Sircar (1942), Select inscriptions bearing on Indian history and civilisation Vol 1, From sixth century BC to sixth century AD, Calcutta. These are four renderings of the same text.

- ^ D.C.Sircar (1942), Select inscriptions bearing on Indian history and civilisation Vol 1, From sixth century BC to sixth century AD, Calcutta.

- ^ S Jaiswal (1967), The origins and development of Vaisnavism, New Delhi - Manhorlal Munshiram.

- ^ Gavin Flood (2003), The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 5 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^ Barnett, Lionel David (1922). Hindu Gods and Heroes: Studies in the History of the Religion of India. J. Murray. p. 93.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Puri, B.N. (1968). India in the Time of Patanjali. Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan.Page 51: The coins of Raj uvula have been recovered from the Sultanpur District.. the Brahmi inscription on the Mora stone slab, now in the Mathura Museum,

- ^

Barnett, Lionel David (1922). Hindu Gods and Heroes: Studies in the History of the Religion of India. J. Murray. p. 92.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ John Dowson (2003). Classical Dictionary of Hindu Mythology and Religion, Geography, History and Literature. Kessinger Publishing. p. 361. ISBN 0-7661-7589-8.

- ^ See Beck, Guy, "Introduction" in Beck 2005, pp. 1–18

- ^ Knott 2000, p. 55

- ^ Flood (1996) p. 117

- ^ a b See McDaniel, June, "Folk Vaishnavism and Ṭhākur Pañcāyat: Life and status among village Krishna statues" in Beck 2005, p. 39

- ^ a b Kennedy, M.T. (1925). The Chaitanya Movement: A Study of the Vaishnavism of Bengal. H. Milford, Oxford university press.

- ^ K. Klostermaier (1997). The Charles Strong Trust Lectures, 1972-1984. Brill Academic Pub. p. 109. ISBN 90-04-07863-0.

For his worshippers he is not an avatara in the usual sense, but svayam bhagavan, the Lord himself.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|other=ignored (|others=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Delmonico, N., The History Of Indic Monotheism And Modern Chaitanya Vaishnavism in Ekstrand 2004

- ^ De, S.K. (1960). Bengal's contribution to Sanskrit literature & studies in Bengal Vaisnavism. KL Mukhopadhyaya. p. 113: "The Bengal School identifies the Bhagavat with Krishna depicted in the Shrimad-Bhagavata and presents him as its highest personal god."

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 381 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBryant2007 (help)

- ^

"Vaishnava". encyclopedia. Division of Religion and Philosophy

University of Cumbria. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 36 (help) [ Vaishnava] University of Cumbria website Retrieved on 5-21-2008 - ^ Graham M. Schweig (2005). Dance of Divine Love: The Rڄasa Lڄilڄa of Krishna from the Bhڄagavata Purڄa. na, India's classic sacred love story. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. Front Matter. ISBN 0-691-11446-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Hein, Norvin. "A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: The Cult of Gopāla: History of Religions, Vol. 25, No. 4 (May, 1986 ), pp. 296-317". www.jstor.org. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ a b c Hastings, James Rodney (2nd edition 1925-1940, reprint 1955, 2003) [1908-26]. Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. John A Selbie (Volume 4 of 24 ( Behistun (continued) to Bunyan.) ed.). Edinburgh: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 476. ISBN 0-7661-3673-6. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

The encyclopedia will contain articles on all the religions of the world and on all the great systems of ethics. It will aim at containing articles on every religious belief or custom, and on every ethical movement, every philosophical idea, every moral practice.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)pp.540-42 - ^ Bhattacharya, Gouriswar: Vanamala of Vasudeva-Krsna-Visnu and Sankarsana-Balarama. In: Vanamala. Festschrift A.J. Gail. Serta Adalberto Joanni Gail LXV. diem natalem celebranti ab amicis collegis discipulis dedicata.

- ^

Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2005), A Survey of Hinduism, State University of New York Press; 3 edition, p. 206, ISBN 0791470814,

Present day Krishna worship is an amalgam of various elements. According to historical testimonies Krishna-Vasudeva worship already flourished in and around Mathura several centuries before Christ. A second important element is the cult of Krishna Govinda. Still later is the worship of Bala-Krishna, the Child Krishna - a quite prominent feature of modern Krishnaism. The last element seems to have been Krishna Gopijanavallabha, Krishna the lover of the Gopis, among whom Radha occupies a special position. In some books Krishna is presented as the founder and first teacher of the Bhagavata religion.

- ^ Basham, A. L. "Review:Krishna: Myths, Rites, and Attitudes. by Milton Singer; Daniel H. H. Ingalls, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3 (May, 1968 ), pp. 667-670". www.jstor.org. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ Singh, R.R. (2007). Bhakti And Philosophy. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739114247.

- p. 10: "[Panini's] term Vāsudevaka, explained by the second century B.C commentator Patanjali, as referring to "the follower of Vasudeva, God of gods."

- ^

Couture, André (2006). "The emergence of a group of four characters (Vasudeva, Samkarsana, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha) in the Harivamsa: points for consideration". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 34 (6): 571–585. doi:10.1007/s10781-006-9009-x.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Klostermaier, K. (1974). "The Bhaktirasamrtasindhubindu of Visvanatha Cakravartin". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 94 (1): 96–107. doi:10.2307/599733. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ^ Vaudeville, C. (1962). "Evolution of Love-Symbolism in Bhagavatism". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 82 (1): 31–40. doi:10.2307/595976. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ^ Bowen, Paul (1998). Themes and issues in Hinduism. London: Cassell. pp. 64–65. ISBN 0-304-33851-6.

- ^ Radhakrisnasarma, C. (1975). Landmarks in Telugu Literature: A Short Survey of Telugu Literature. Lakshminarayana Granthamala.

- ^ Sisir Kumar Das (2005). A History of Indian Literature, 500-1399: From Courtly to the Popular. Sahitya Akademi. p. 49. ISBN 8126021713.

- ^ "Iskcon address listing" (html) (in engl). iskcon.com. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Selengut, Charles (1996), "Charisma and Religious Innovation:Prabhupada and the Founding of ISKCON", ISKCON Communications Journal, 4 (2)

- ^ Srila Prabhupada - He Built a House in which the whole world can live, Satsvarupa dasa Goswami, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1983, ISBN 0-89213-133-0 page xv

- ^ Varadpande p.231

- ^ Varadpande p.232-3

- ^ Zarrilli, P.B. (2000). Kathakali Dance-Drama: Where Gods and Demons Come to Play. Routledge. p. 246.

- ^ See Jerome H. Bauer ""Hero of Wonders, Hero in Deeds: Vasudeva Krishna in Jaina Cosmohistory in Beck 2005, pp. 167–169

- ^ Jaini, P.S. (1993). "Jaina Puranas: A Puranic Counter Tradition". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 94: 96. doi:10.2307/599733.

- ^ Cort, J.E. (1993). "An Overview of the Jaina Puranas". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 94: 96. doi:10.2307/599733.

- ^ "Andhakavenhu Puttaa". www.vipassana.info. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ a b Law, B.C. (1941). India as Described in Early Texts of Buddhism and Jainism. Luzac.

- ^ Jaiswal, S. (1974). "Historical Evolution of the Ram Legend'". Social Scientist. 94: 96. doi:10.2307/599733.

- ^ Hiltebeitel, A. (1990). The Ritual of Battle: Krishna in the Mahabharata. State University of New York Press.

- ^ The Turner of the Wheel. The Life of Sariputta, compiled and translated from the Pali texts by Nyanaponika Thera

- ^ Guth, C.M.E. "Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Spring, 1987 ), pp. 1-23". www.jstor.org. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ Esslemont, J.E. (1980). Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era (5th ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 2. ISBN 0-87743-160-4.

- ^ Ahmad, Mirza Ghulam (2007). Lecture Sialkot (PDF). Tilford: Islam International Publications Ltd. ISBN 1-85372-917-5.

- ^ Harvey, D. A. (2003). "Beyond Enlightenment: Occultism, Politics, and Culture in France from the Old Regime to the Fin-de-Siècle". The Historian. 65 (3). Blackwell Publishing: 665–694. doi:10.1111/1540-6563.00035.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Schure, Edouard (1992). Great Initiates: A Study of the Secret History of Religions. Garber Communications. ISBN 0893452289.

- ^ See for example: Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (1996). New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. Brill Publishers. p. 390. ISBN 9004106960., Hammer, Olav (2004). Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age. Brill Publishers. pp. 62, 174. ISBN 900413638X., and Ellwood, Robert S. (1986). Theosophy: A Modern Expression of the Wisdom of the Ages. Quest Books. p. 139. ISBN 0835606074.

- ^ Crowley associated Krishna with Roman god Dionysus and Magickal formulae IAO, AUM and INRI. See Crowley, Aleister (1991). Liber Aleph. Weiser Books. p. 71. ISBN 0877287295. and Crowley, Aleister (1980). The Book of Lies. Red Wheels. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0877285160.

- ^ Apiryon, Tau (1995). Mystery of Mystery: A Primer of Thelemic Ecclesiastical Gnosticism. Berkeley, CA: Red Flame. ISBN 0971237611.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

References

- Beck, Guy L. (1993), Sonic theology: Hinduism and sacred sound, Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 0-87249-855-7

- Bryant, Edwin H. (2004), Krishna: the beautiful legend of God;, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-044799-7

- Bryant, Edwin H. (2007), Krishna: A Sourcebook, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN 0-19-514891-6

- The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, published between 1883 and 1896

- The Vishnu-Purana, translated by H. H. Wilson, (1840)

- The Srimad Bhagavatam, translated by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, (1988) copyright Bhaktivedanta Book Trust

- Knott, Kim (2000), Hinduism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, USA, p. 160, ISBN 0192853872

- The Jataka or Stories of the Buddha's Former Births, edited by E. B. Cowell, (1895)

- Ekstrand, Maria (2004), Bryant, Edwin H. (ed.), The Hare Krishna movement: the postcharismatic fate of a religious transplant, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-12256-X

- Goswami, S.D (1998), The Qualities of Sri Krsna, GNPress, ISBN 0911233644

- Garuda Pillar of Besnagar, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report (1908-1909). Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1912, 129.

- Flood, G.D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521438780.

- Beck, Guy L. (Ed.) (2005), Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity, SUNY Press, ISBN 0791464156

- Rosen, Steven (2006), Essential Hinduism, New York: Praeger, ISBN 0-275-99006-0

- Valpey, Kenneth R. (2006), Attending Kṛṣṇa's image: Caitanya Vaiṣṇava mūrti-sevā as devotional truth, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-38394-3

- Sutton, Nicholas (2000), Religious doctrines in the Mahābhārata, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 477, ISBN 8120817001

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Bryant, Edwin H. (2007), Krishna: A Sourcebook, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN 0-19-514891-6

- A. L. Dallapiccola (1982), London Krishna the Divine Lover: Myth and Legend Through Indian Art

- History of Indian Theatre By M. L. Varadpande. Chapter Theatre of Krishna, pp.231-94. Published 1991, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 8170172780.

External links

- The Search for the Historical Krishna, by Prof. N.S. Rajaram (veda.harekrsna.cz)

- Sri Krishna - Differences in Realisation & Perception of the Supreme (stephen-knapp.com)

- Hindu Wisdom - Dwarka (http://www.hinduwisdom.info/Dwaraka.htm)

- Vedic Archeology (A Vaishnava Perspective) (gosai.com)

- The Devious God: Mythological Roots of Krishna’s Trickery in the Mahabharata by Elaine Fisher

- Exploits of Lord Krishna

- Article on the chronology of Krishna (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)